#De bello Gothico

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Did the ancient Celts really paint themselves blue?

Part 2: Irish tattoos

Clockwise from top left: Deirdre and Naoise from the Ulster Cycle by amylouioc, detail from The Marriage of Strongbow and Aoife by Daniel Maclise, a modern Celtic revival tattoo, Michael Flatley in a promotional image for the Irish step dance show 'Lord of the Dance'

This is my second post exploring the historical evidence for our modern belief that the ancient and medieval Insular Celts painted or tattooed themselves with blue pigment. In the first post, I discussed the fact that body paint seems to have been used by residents of Great Britain between approximately 50 BCE to 100 CE. In this post, I will examine the evidence for tattooing.

Once again, I am looking at sources pertaining to any ethnic group who lived in the British Isles, this time from the Roman Era to the early Middle Ages. The relevant text sources range from approximately 200 CE to 900 CE. I am including all British Isles cultures, because a) determining exactly which Insular culture various writers mean by terms like ‘Briton’, ‘Scot’, and ‘Pict’ is sometimes impossible and b) I don’t want to risk excluding any relevant evidence.

Continental Written Sources:

The earliest written source to mention tattoos in the British Isles is Herodian of Antioch’s History of the Roman Empire written circa 208 CE. In it, Herodian says of the Britons, "They tattoo their bodies with colored designs and drawings of all kinds of animals; for this reason they do not wear clothes, which would conceal the decorations on their bodies" (translation from MacQuarrie 1997). Herodian is probably reporting second-hand information given to him by soldiers who fought under Septimius Severus in Britain (MacQuarrie 1997) and shouldn't be considered a true primary source.

Also in the early 3rd century, Gaius Julius Solinus says in Collectanea Rerum Memorabilium 22.12, "regionem [Brittaniae] partim tenent barbari, quibus per artifices plagarum figuras iam inde a pueris variae animalium effigies incorporantur, inscriptisque visceribus hominis incremento pigmenti notae crescunt: nec quicquam mage patientiae loco nationes ferae ducunt, quam ut per memores cicatrices plurimum fuci artus bibant."

Translation: "The area [of Britain] is partly occupied by barbarians on whose bodies, from their childhood upwards, various forms of living creatures are represented by means of cunningly wrought marks: and when the flesh of the person has been deeply branded, then the marks of the pigment get larger as the man grows, and the barbaric nations regard it as the highest pitch of endurance to allow their limbs to drink in as much of the dye as possible through the scars which record this" (from MacQuarrie 1997).

This passage, like Herodian's, is clearly a description of tattooing, not body staining or painting. That said, I have no idea of tattoos actually work like this. I would think this would result in the adult having a faded, indistinct tattoo, but if anyone knows otherwise, please tell me.

The poet Claudian, writing in the early 5th c., is the first to specifically mention the Picts having tattoos (MacQuarrie 1997). In De Bello Gothico he says, "Venit & extremis legio praetenta Britannis,/ Quæ Scoto dat frena truci, ferroque notatas/ Perlegit exanimes Picto moriente figuras."

Translation: "The legion comes to make a trial of the most remote parts of Britain where it subdues the wild Scot and gazes on the iron-wrought figures on the face of the dying Pict" (from MacQuarrie 1997).

Last, and possibly least, of our Mediterranean sources is Isidore of Seville. In the early 7th c. he writes, "the Pictish race, their name derived from their body, which the efficient needle, with minute punctures, rubs in the juices squeezed from native plants so that it may bring these scars to its own fashion [. . .] The Scotti have their name from their own language by reason of [their] painted body, because they are marked by iron needles with dark coloring in the form of a marking of varying shapes." (translation from MacQuarrie 1997)

Isidore is the earliest writer to explicitly link the name 'Pict' to their 'painted' (Latin: pictus) i.e. tattooed bodies. Isidore probably borrowed information for his description from earlier writers like Claudian (MacQuarrie 1997).

In the 8th century, we have a source that definitely isn't Romans recycling old hearsay. In 786, a pair of papal legates visited the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria (Story 1995). In their report to Pope Hadrian, the legates condemn pagans who have "superimposed most hideous cicatrices" (i.e gotten tattoos), likening the pagan practice to coloring oneself "with dirty spots". The location of the visit indicates that these are Anglo-Saxon tattoos rather than Celtic, but some scholars have suggested that the Anglo-Saxons might have adopted the practice from the Brittonic Celts (MacQuarrie 1997).

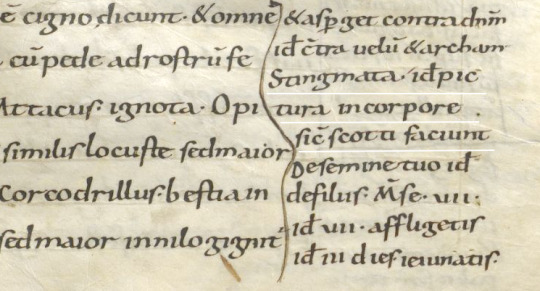

A gloss in the margin of the late 9th c. German manuscript Fulda Aa 2 defines Stingmata [sic] as "put pictures on the bodies as the Irish (Scotti) do." (translation from MacQuarrie 1997).

Fulda Aa 2 folio 43r The gloss is on the left underlined in white.

Irish Written Sources:

Irish texts that mention tattoos date to approximately 700-900 CE, although some of them have glosses that may be slightly later, and some of them cannot be precisely dated.

The first text source is a poem known in English as "The Caldron of Poesy," written in the early 8th c. (Breatnach 1981). The poem is purportedly the work of Amairgen, ollamh of the legendary Milesian kings. In the first stanza of the poem, he introduces himself saying, "I being white-kneed, blue-shanked, grey-bearded Amairgen." (translation from Breatnach 1981)

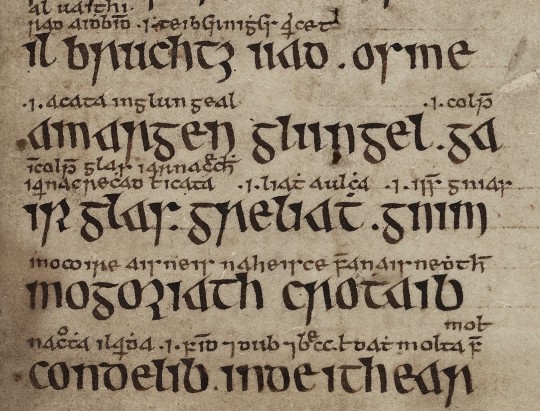

The text of the poem with interline glosses from Trinity College Dublin MS 1337/1

The word garrglas (blue-shanked) has a Middle Irish (c. 900-1200) gloss added by a later scribe, defining garrglas as: "a tattooed shank, or who has the blue tattooed shank" (Breatnach 1981).

Although Amairgen was a mythical figure, the position ollamh was not. An ollamh was the highest rank of poet in medieval Ireland, considered worthy of the same honor-price as a king (Carey 1997, Breatnach 1981). The fact that a man of such esteemed status introduces himself with the descriptor 'blue-shanked' suggests that tattoos were a respectable thing to have in early medieval Ireland.

The leg tattoos are also mentioned c. 900 CE in Cormac’s Glossary. It defines feirenn as "a thong which is about the calf of a man whence ‘a tattooed thong is tattooed about [the] calf’" (translation from MacQuarrie 1997)

The Irish legal text Uraicecht Becc, dated to the 9th or early 10th c., includes the word creccoire on a list of low-status occupations (Szacillo 2012, MacNeill 1924). A gloss defines it as: crechad glass ar na roscaib, a phrase which Szacillo interprets as meaning "making grey-blue sore (tattooing) on the eyes" (2012). This sounds rather strange, but another early Irish text clarifies it.

The Vita sancti Colmani abbatis de Land Elo written around the 8th-9th centuries (Szacillo 2012) contains the following episode:

On another time, St Colmán, looking upon his brother, who was the son of Beugne, saw that the lids of his eyes had been secretly painted with the hyacinth colour, as it was in the custom; and it was a great offence at St Colmán’s. He said to his brother: ‘May your eyes not see the light in your life (any more). And from that hour he was blind, seeing nothing until (his) death. (translation from Szacillo 2012).

The original Latin phrase describing what so offended St Colmán "palpebre oculorum illius latenter iacinto colore" does not contain the verb paint (pingo). It just says his eyelids were hyacinth (blue) colored. This passage together with the gloss from the Uraicecht Becc implies that there was a custom of tattooing people's eyelids blue in early medieval Ireland. A creccoire* was therefore a professional eyelid tattooer or a tattoo artist.

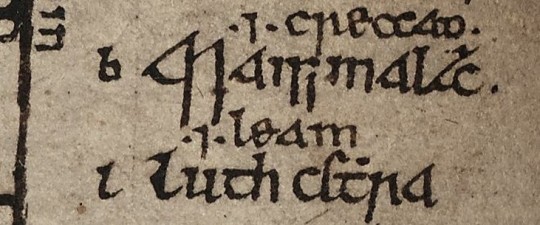

A possible third reference to tattooing the area around the eye is found in a list of Old Irish kennings. The kenning for the letter 'B' translates as 'Beauty of the eyebrow.' This kenning is glossed with the word crecad/creccad (McManus 1988). Crecad could be translated as cauterizing, branding, or tattooing (eDIL). McManus suggests "adornment (by tattooing) of the eyebrow" as a plausible interpretation of how crecad relates to the beauty of the eyebrow (1988). The precise date of this text is not known (McManus 1988), but Old Irish was used c. 600-900 CE, meaning this text is of a similar date to the other Irish references to tattoos.

Kenning of the letter 'b' with gloss from TCD MS 1337/1

There is a sharp contrast between the association of tattoos with a venerated figure in 'The Caldron of Poesy', and their association with low-status work and divine punishment in the Uraicecht Becc and the Vita. This indicates that there was a shift in the cultural attitude towards tattoos in Ireland during the 7th-9th centuries. The fact that a Christian saint considered getting tattoos a big enough offense to punish his own brother with blindness suggests that tattooing might have been a pagan practice which gradually got pushed out by the Catholic Church. This timeline is consistent with the 786 CE report of the papal legates condemning the pagan practice of tattooing in Great Britain (MacQuarrie 1997).

There are some mentions of tattooing in Lebor Gabála Érenn, but the information largely appears to be borrowed from Isidore of Seville (MacQuarrie 1997). The fact that the writers of LGE just regurgitated Isidore's meager descriptions of Pictish and Scottish (ie Irish) tattooing without adding any details, such as the designs used or which parts of the body were tattooed, makes me think that Insular tattooing practices had passed out of living memory by the time the book was written in the 11th century.

*There is some etymological controversy over this term. Some have suggested that the Old Irish word for eyelid-tattooer should actually be crechaire. more info Even if this hypothesis is correct, and the scribe who wrote the gloss on creccoire mistook it for crechaire, this doesn't contradict my argument. The scribe clearly believed that eyelid-tattooer belonged on a list of low-status occupations.

Discussion:

Like Julius Cesar in the last post, Herodian of Antioch c. 208 CE makes some dubious claims of Celtic barbarism, stating that the Britons were: "Strangers to clothing, the Britons wear ornaments of iron at their waists and throats; considering iron a symbol of wealth, they value this metal as other barbarians value gold" (translation from MacQuarrie 1997). If the Britons wore nothing but iron jewelry, then why did they have brass torcs and 5,000 objects that look like they're meant to attach to fabric, Herodian?

Brass torc from Lochar Moss, Scotland c. 50-200 CE. Romano-British trumpet brooch from Cumbria c. 75-175 CE. image from the Portable Antiquities Scheme.

Trumpet brooches are a Roman Era artifact invented in Britain, that were probably pinned to people's clothing. more info

Although Herodian and Solinus both make dubious claims, there are enough differences between them to indicate that they had 2 separate sources of information, and one was not just parroting the other. This combined with the fact that we have more-reliable sources from later centuries confirming the existence of tattoos in the British Isles makes it probable that there was at least a grain of truth to their claims of tattooing.

There is a common belief that the name Pict originated from the Latin pictus (painted), because the Picts had 'painted' or tattooed bodies. The Romans first used the name Pict to refer to inhabitants of Britain in 297 CE (Ware 2021), but the first mention of Pictish tattoos came in 402 CE (Carr 2005), and the first explicit statement that the name Pict was derived from the Picts' tattooed bodies came from Isidore of Seville c. 600 CE (MacQuarrie 1997). Unless someone can find an earlier source for this alleged etymology than Isidore, I am extremely skeptical of it.

Summary of the written evidence:

Some time between c. 79 CE (Pliny the Elder) and c. 208 CE (Herodian of Antioch) the practice of body art in Great Britain changed from staining or painting the skin to tattooing. Third century Celtic Briton tattoo designs depicted animals. Pictish tattoos are first mentioned in the 5th century.

The earliest mention of Irish tattoos comes from Isidore of Seville in the early 6th c., but since it seems to have been a pre-Christian practice, it likely started earlier. Irish tattoos of the 8-9th centuries were placed on the area around the eye and on the legs. They were a bluish color. The 8th c. Anglo-Saxons also had tattoos.

Tattooing in Ireland probably ended by the early 10th c., possibly because of Christian condemnation. Exactly when tattooing ended in Great Britain is unclear, but in the 12th c., William of Malmesbury describes it as a thing of the past (MacQuarrie 1997). None of these sources give much detail as to what the tattoos looked like.

The Archaeology of Insular Ink:

In spite of the fact that tattooing was a longer-lasting, more wide-spread practice in the British Isles than body painting, there is less archaeological evidence for it. This may be because the common tools used for tattooing, needles or blades for puncturing the skin, pigments to make the ink, and dishes to hold the ink, all had other common uses in the Middle Ages that could make an archaeologist overlook their use in tattooing. The same needle that was used to sew a tunic could also have been used to tattoo a leg (Carr 2005). A group of small, toothed bronze plates from a Romano-British site at Chalton, Hampshire might have been tattoo chisels (Carr 2005) or they might have been used to make stitching holes in leather (Cunliffe 1977).

Although the pigment used to make tattoos may be difficult to identify at archaeological sites, other lines of evidence might give us an idea of what it was. Although the written sources tell us that Irish tattoos were blue, the popular modern belief that woad was the source of the tattoo pigment is, in my opinion, extremely unlikely for a couple of reasons:

1) Blue pigment from woad doesn't seem to work as tattoo ink. The modern tattoo artists who have tried to use it have found that it burns out of the person's skin, leaving a scar with no trace of blue in it (Lambert 2004).

2) None of the historical sources actually mention tattooing with woad. Julius Cesar and Pliny the Elder mention something that might have been woad, but they were talking about body paint, not tattoos. (see previous post) Isidore of Seville claimed that the Picts were tattooing themselves with "juices squeezed from native plants", but even assuming that Isidore is a reliable source, you can't get blue from woad by just squeezing the juice out of it. In order to get blue out of woad, you have to first steep the leaves, then discard the leaves and add a base like ammonia to the vat (Carr 2005). The resulting dye vat is not something any knowledgeable person would describe as plant juice, so either Isidore had no idea what he was talking about, or he is talking about something other than blue pigment from woad.

In my opinion, the most likely pigment for early Irish and British tattoos is charcoal. Early tattoos found on mummies from Europe and Siberia all contain charcoal and no other colored pigment. These tattoos range in date from c. 3300 BCE (Ötzi the Iceman) to c. 300 CE (Oglakhty grave 4) (Samadelli et al 2015, Pankova 2013).

Despite the fact that charcoal is black, it tends to look blueish when used in tattoos (Pankova 2013). Even modern black ink tattoos that use carbon black pigment (which is effectively a purer form of charcoal) tend to look increasingly blue as they age.

A 17-year-old tattoo in carbon black ink photographed with a swatch of black Sharpie on white printer paper.

The fact that charcoal-based tattoo inks continue to be used today, more than 5,000 years after the first charcoal tattoo was given, shows that charcoal is an effective, relatively safe tattoo pigment, unlike woad. Additionally, charcoal can be easily produced with wood fires, meaning it would have been a readily available material for tattoo artists in the early medieval British Isles. We would need more direct evidence, like a tattooed body from the British Isles, to confirm its use though.

As of June 2024, there have been at least 279 bog bodies* found in the British Isles (Ó Floinn 1995, Turner 1995, Cowie, Picken, Wallace 2011, Giles 2020, BBC 2024), a handful of which have made it into modern museum collections. Unfortunately, tattoos have not been found on any of them. (We don't have a full scientific analysis for the 2023 Bellaghy find yet though.)

*This number includes some finds from fens. It does not include the Cladh Hallan composite mummies.

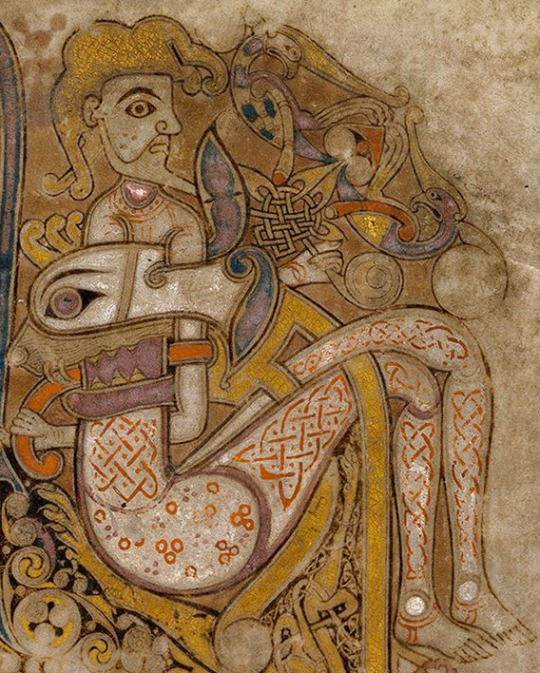

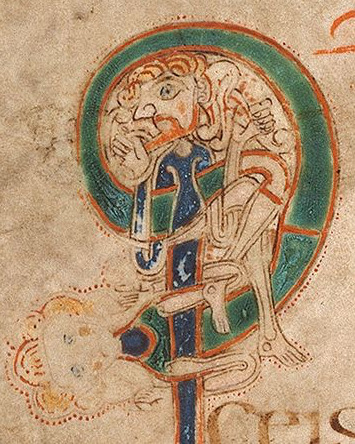

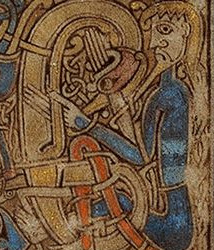

Tattoos in period art?

It has been suggested that the man fight a beast on Book of Kells f. 130r may be naked and covered in tattoos (MacQuarrie 1997). However, Dress in Ireland author Mairead Dunlevy interprets this illustration as a man wearing a jacket and trews (Dunlevy 1989). Looking at some of the other figures in the Book of Kells, I agree with Dunlevy. F. 97v shows the same long, fitted sleeves and round neckline. F. 292r has long, fitted leg coverings, presumably trews, and also long sleeves. The interlace and dot motifs on f. 130r's legs may be embroidery. Embroidered garments were a status symbol in early medieval Ireland (Dunlevy 1989).

Left to right: Book of Kells folios 130r, 97v, 292r

A couple of sculptures in County Fermanagh might sport depictions of Irish tattoos. The first, known as the Bishop stone, is in the Killadeas cemetery. It features a carved head with 2 marks on the left side of the face, a double line beside the mouth and a single line below the eye. These lines may represent tattoos.

The second sculpture is the Janus figure on Boa Island. (So named because it has 2 faces; it's not Roman.) It has marks under the right eye and extending from the corner of the left eye that may be tattoos.

I cannot find a definitive date for the Bishop stone head, but it bears a strong resemblance to the nearby White Island church figures. The White Island figures are stylistically dated to the 9th-10th centuries and may come from a church that was destroyed by Vikings in 837 CE (Halpin and Newman 2006, Lowry-Corry 1959). The Janus figure is believed to be Iron Age or early medieval (Halpin and Newman 2006).

Conclusions:

Despite the fact that tattooing as a custom in the British Isles lasted for more than 500 years and was practiced by at least 3 different cultures, written sources remain our only solid evidence for it. With only a dozen sources, some of which probably copied each other, to cover this time span, there are huge gaps in our knowledge. The 4th century Picts may not have had the same tattoo designs, placements or reasons for getting tattooed as the 8th c. Irish or Anglo-Saxons. These sources only give us fragments of information on who got tattooed, where the tattoos were placed, what they looked like, how the tattoos were done, and why people got tattooed. Further complicating our limited information is the fact that most of the text sources come from foreigners and/or people who were prejudiced against tattooing, which calls their accuracy into question.

'The Cauldron of Posey' is one source that provides some detail while not showing prejudice against tattoos. The author of the poem was probably Christian, but the poem appears to have been written at a time when Pagan practices were still tolerated in Ireland. I have a complete translation of the poem along with a longer discussion of religious elements here.

Leave me a tip?

Bibliography:

BBC (2024). Bellaghy bog body: Human remains are 2,000 years old https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-68092307

Breatnach, L. (1981). The Cauldron of Poesy. Ériu, 32(1981), 45-93. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30007454

Carey, J. (1997). The Three Things Required of a Poet. Ériu, 48(1997), 41-58. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30007956

Carr, Gillian. (2005). Woad, Tattooing and Identity in Later Iron Age and Early Roman Britain. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 24(3), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0092.2005.00236.x

Cowie, T., Pickin, J. and Wallace, T. (2011). Bog bodies from Scotland: old finds, new records. Journal of Wetland Archaeology 10(1): 1–45.

Cunliffe, B. (1977) The Romano-British Village at Chalton, Hants. Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club and Archaeological Society, 33(1977), 45-67.

Dunlevy, Mairead (1989). Dress in Ireland. B. T. Batsford LTD, London.

eDIL s.v. crechad https://dil.ie/12794

Giles, Melanie. (2020). Bog Bodies Face to face with the past. Manchester University Press, Manchester. https://library.oapen.org/viewer/web/viewer.html?file=/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/46717/9781526150196_fullhl.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Halpin, A., Newman, C. (2006). Ireland: An Oxford Archaeological Guide to Sites from Earliest Times to AD 1600. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://archive.org/details/irelandoxfordarc0000halp/page/n3/mode/2up

Hoecherl, M. (2016). Controlling Colours: Function and Meaning of Colour in the British Iron Age. Archaeopress Publishing LTD, Oxford. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Controlling_Colours/WRteEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Lambert, S. K. (2004). The Problem of the Woad. Dunsgathan.net. https://dunsgathan.net/essays/woad.htm

Lowry-Corry, D. (1959). A Newly Discovered Statue at the Church on White Island, County Fermanagh. Ulster Journal of Archaeology, 22(1959), 59-66. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20567530

MacQuarrie, Charles. (1997). Insular Celtic tattooing: History, myth and metaphor. Etudes Celtiques, 33, 159-189. https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.1997.2117

McManus, D. (1988). Irish Letter-Names and Their Kennings. Ériu, 39(1988), 127-168. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30024135

Ó Floinn, R. (1995). Recent research into Irish bog bodies. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 137–45). British Museum Press, London. ISBN: 9780714123059

Pankova, S. (2013). One More Culture with Ancient Tattoo Tradition in Southern Siberia: Tattoos on a Mummy from the Oglakhty Burial Ground, 3rd-4th century AD. Zurich Studies in Archaeology, 9(2013), 75-86.

Samadelli, M., Melisc, M., Miccolic, M., Vigld, E.E., Zinka, A.R. (2015). Complete mapping of the tattoos of the 5300-year-old Tyrolean Iceman. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 16(2015), 753–758.

Story, Joanna (1995). Charlemagne and Northumbria : the in

fluence of Francia on Northumbrian politics in the later eighth and early ninth centuries. [Doctoral Thesis]. Durham University. http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1460/

Szacillo, J. (2012). Irish hagiography and its dating: a study of the O'Donohue group of Irish saints' lives. [Doctoral Thesis]. Queen's University Belfast.

Turner, R.C. (1995). Resent Research into British Bog Bodies. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 221–34). British Museum Press, London. ISBN: 9780714123059

Ware, C. (2021). A Literary Commentary on Panegyrici Latini VI(7) An Oration Delivered Before the Emperor Constantine in Trier, ca. AD 310. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_Literary_Commentary_on_Panegyrici_Lati/oEwMEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

#early medieval#roman era#pict#tattoos#ancient celts#apologies to people who wanted a shorter post#archaeology#art#anecdotes and observations#statutes and laws#irish history#gaelic ireland#medieval ireland#anglo saxon#insular celts#romano british

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

21) Ubykhowie (Ubykh: Пэху / Туахы, Pəxu / Tuaxy; Adyghe: Убых, Ubyx; rosyjski: Убыхи; turecki: Ubıhlar / Vubıhlar) - jedno z dwunastu głównych plemion czerkieskich, reprezentowanych przez jedną z dwunastu gwiazd na zielono-złotej fladze czerkieskiej. Wraz z plemionami Natukhai i Shapsug, Ubychowie byli jednym z trzech przybrzeżnych plemion czerkieskich, które utworzyły Zgromadzenie Czerkieskie (Adyghe: Адыгэ Хасэ) w 1860 roku. Historycznie rzecz biorąc, mówili odrębnym językiem ubichskim, który nigdy nie istniał w formie pisanej i wymarł w 1992 r., kiedy zmarł Tevfik Esenç, ostatni mówca.

Ubychowie zamieszkiwali stolicę Czerkiesów, Sache (czerkieski: Шъачэ, dosł. nadmorski) — dzisiejsze Soczi, Kraj Krasnodarski, Rosja. Prowincja plemienia Ubychów znajdowała się pomiędzy plemieniem Szapsug w pobliżu Tuapse i Sadz (Dzhigets) na północy Gagry. Plemię Ubychów zostało wspomniane w IV księdze De Bello Gothico Prokopiusa (Wojna gotycka) pod nazwą βροῦχοι (Bruchi), co jest zniekształceniem rodzimego terminu tʷaχ. W księdze Evliyi Çelebi z 1667 roku Ubykhowie zostali wymienieni jako Ubúr bez żadnych innych informacji. Kirantukh Berzeg (Бэрзэг Кэрэнтыхъу), książę Ubykh. Ubykowie byli na wpół koczowniczymi jeźdźcami i mieli bardzo zróżnicowane słownictwo związane z końmi i sprzętem. Niektórzy Ubykowie również praktykowali faworyzację i skapulimancję. Jednak w czasach nowożytnych Ubykh zyskał większe znaczenie. W roku 1864, za panowania cara Aleksandra II, dobiegł końca rosyjski podbój północno-zachodniego Kaukazu. Pozostałe plemiona czerkieskie i Abchazi zostały zdziesiątkowane, a Abaza częściowo wypędzeni z Kaukazu. W obliczu groźby ujarzmienia przez armię rosyjską, Ubych, a także inne ludy muzułmańskie Kaukazu masowo opuściły swoją ojczyznę począwszy od 6 marca 1864 r. Do 21 maja cały naród ubichski opuścił Kaukaz. W końcu osiedlili się w wielu wioskach w zachodniej Turcji wokół gminy Manyas. Aby uniknąć dyskryminacji, starsi Ubykh zachęcali swój lud do asymilacji z kulturą turecką. Porzuciwszy swoją tradycyjną kulturę koczowniczą, stali się narodem rolników. Język ubichski został szybko wyparty przez dialekty tureckie i inne dialekty czerkieskie; ostatni rodzimy użytkownik języka Ubykh, Tevfik Esenç, zmarł w 1992 roku. Dziś diaspora ubichska jest rozproszona po Turcji i – w znacznie mniejszym stopniu – Jordanii. Naród Ubychów jako taki już nie istnieje, chociaż ci, którzy mają ubichskie korzenie, z dumą nazywają siebie Ubychami, a w Turcji nadal można znaleźć kilka wiosek, gdzie zdecydowana większość populacji to Ubykowie z pochodzenia. Społeczeństwo Ubykh było patrylinearne; wielu potomków Ubychów zna dziś pięć, sześć, a nawet siedem pokoleń swoich agnatycznych przodków. Niemniej jednak, podobnie jak w innych plemionach północno-zachodniego Kaukazu, kobiety były szczególnie czczone, a Ubykh zachował specjalny przedrostek zaimka drugiej osoby, używany wyłącznie w odniesieniu do kobiet (χa-).

0 notes

Photo

Nuovo post su https://is.gd/Fd2xHt

Brindisi nella guerra greco-gotica, una lunga guerra poco nota ma dalle conseguenze epocali (prima parte)

Giustiniano e la sua corte. Mosaico nella chiesa di San Vitale a Ravenna

di Gianfranco Perri

La storiografia classica colloca convenzionalmente il passaggio dal Tardoantico al Medioevo in coincidenza con la caduta dell’Impero Romano d’Occidente, a sua volta associata alla deposizione dell’ultimo imperatore, Romulo Augustulo, per mano del generale romano di origini unne Odoacre, nel 476 dC., estromesso dopo tredici anni dal goto Teodorico e da questi ucciso nel 493. Da qualche tempo però, gli storici hanno messo in discussione tale convenzione, osservando che più significativo che l’individuazione di una data precisa in cui collocare il trapasso, sia l’individuare la fine della persistenza dell’antico, cosa che si traduce inevitabilmente in accettare una transizione più o meno lenta e solo eventualmente più o meno legata a un qualche specifico accadimento, in sostituire quindi a una data un periodo e infine, in considerare un passaggio non unico ma diverso da luogo o regione a regione.

In questo ordine di idee, per Brindisi e per la sua regione salentina, probabilmente lo spartiacque tra il Tardo Antico e l’Alto Medio, potrebbe averlo costituito la ventennale guerra greco-gotica iniziata nel 535, una sessantina d’anni dopo la fine dell’Impero Romano d’Occidente. Infatti, anche se le fonti sul corso della guerra intorno a Brindisi non sono molto prodighe di notizie e sono comunque sufficienti a poter determinare la ‘non occorrenza’ di un evento dalla portata emblematica di un cataclisma epocale, è indubbio che l’avvento del dominio bizantino conseguente al risultato di quella lunga guerra – che vide finalmente sconfitti i Goti – costituì certamente un cambio profondo e una interruzione drastica per un sistema socioeconomico e politico che, se pur in graduale e oscillante evoluzione, con i Goti si era mantenuto in sostanziale continuità con il trascorso Basso Impero.

Le Variae di Caissiodoro Flavius Magnus Aurelius (~486-560) costitiscono la fonte più diretta circa il cinquantennale periodo del dominio gotico in Italia, con il re Teodorico, Amalasunta sua figlia reggente del fratello Atalarico, e il re Teodato cugino marito e omicida di lei. Mentre numerosi ed interessanti dettagli sono riportati nello “Stato politico economico di Brindisi dagli Inizi del IV Secolo all’anno 670” di Giacomo Carito in Brundisii Res, 1976 e “Sulle Condizioni Economiche della Puglia dal IV al VII Secolo dC” di Francesco M. De Robertis, 1951 in “Archivio Storico Pugliese”.

Fonte principale della guerra gotica è, invece, il De bello Gothico di Procopio di Cesarea (~495-565), storico greco, segretario e consigliere al seguito del comandante bizantino Flavio Belisario, in parte – fino al 540 – testimone diretto e privilegiato degli eventi che si susseguirono in Italia fin dallo sbarco in Sicilia degli eserciti bizantini inviati dall’imperatore Giustiniano – l’ultimo imperatore con origini romane – completato dagli scritti di Agazia di Mirina (~536-582), un altro storico bizantino considerato il continuatore di Procopio, che iniziò la sua narrazione della guerra dal punto – circa il 550 – in cui l’interruppe Procopio, descrivendone di fatto le fasi finali con le campagne di Narsete, il generale bizantino eunuco e grande stratega, che rilevò Belisario dal comando fino a culminare vittoriosamente la guerra.

********

La lunga guerra si sviluppò in due fasi ben separate tra di esse. La prima vide una relativamente rapida vittoria dei Bizantini di Belisario che, sbarcato nel luglio del 536 in Sicilia e conquistatala, varcò lo stretto e attraverso la Calabria si diresse a Napoli che, assediata e conquistata in soli venti giorni, fu sacchegiata indiscriminatamente. In seguito, lo sconfitto re goto Teodato venne sacrificato dai suoi ed al suo posto fu eletto Vitige, il quale dalla capitale del regno, Ravenna, si dispose a organizzare la reazione gotica, mentre Roma senza resistere si arrendeva a Belisario il 10 dicembre del 536. Quindi, Vitige tentò la riconquista di Roma assediandola con un numeroso esercito, ma vanamente e dopo un anno ripiegò nuovamente su Ravenna. Poi, trascorso qualche altro anno di alterne vicende belliche – che nel 537 videro lo sbarco a Otranto di un contingente fresco di mille soldati e di ottocento cavalieri comandati dal generale bizantino Giovanni – fu Belisario a porre l’assedio a Ravenna, che resistette a lungo finchè un vorace icendio, probabilmente doloso, distrusse tutte le scorte di grano. Vitige allora, nella primavera del 540, decise di capitolare e, al seguito di Belisario, fu portato come trofeo a Costantinopoli, dove poi rimase in esilio dorato.

La prima fase della guerra, conclusasi a favore dei Greci, aveva avuto come teatro delle operazioni essenzialmente Roma e le regioni del centro e del nord’Italia e i Goti, in seguito alla capitolazione di Vitige, nel settembre-ottobre del 541 elessero re Baduila, detto Totila che vuol dire ‘immortale’, dopo il breve regno di Ildibald, uno zio di Baduila che presto era rimasto ucciso e dopo Erarico, eletto re ma poi contrastato ed ucciso dopo soli cinque mesi di regno.

«Il ritorno di Belisario a Costantinpoli aveva lasciato l’Italia in mano ai comandanti militari [capeggiati da un debole Costanziano] inesperti di amministrazione, e agli esattori delle tasse, espertissimi ed inesorabili nello spremere denaro anche là dove l’indigenza e la miseria rendevano precaria la stessa vita quotidiana. Le popolazioni esasperate cominciavano già a rimpiangere il governo del Goti.»1

Totila – che da subito applicò una politica intelligente, seguendo l’esempio del suo antecessore Teodorico, facendo il contrario dei Bizantini e gravando i grandi proprietari e favorendo contadini e coloni – organizzata la riscossa, con anche il favore delle popolazioni, procedette a riconquistare gradualmente i territori controllati dai Bizantini e a rioccupare le regioni più meridionali del regno, che non avendo subito le devastazioni della guerra costituivano territori ottimi per i rifornimenti di vettovaglie.

«E poiché niun nemico veniagli contro, sempre mandando attorno piccoli drappelli di truppe, [Totila] operò fatti di gran rilievo. Sottomise l’Abbruzzo e la Lucania e s’impossessò delle Puglie e della Calabria, e i pubblici tributi egli riscosse, e i frutti degli averi si appropriò in luogo dei possessori dei terreni, e di ogni altra cosa dispose come signore d’Italia.»2

Era così iniziata la seconda fase della guerra, fase questa che coinvolse da vicino anche la Puglia, il Salento – cioè l’antica Calabria – e quindi Brindisi. Presa Napoli, nell’aprile del 543, Totila si diresse ad assediare Roma e al contempo inviò una parte dell’esercito verso Sud, su Otranto, sapendo che quella città con Brindisi e Taranto costituiva un triangolo chiaramente strategico per la logistica bizantina, che da quei tre porti dipendeva primordialmente per mantenere attivi ed agili gli indispensabili collegamenti militari e mercantili con la capitale e con il resto dell’impero.

A quel punto, Giustiniano, preoccupato per il precipitare degli eventi, nell’estate del 544 rispedì Belisario in Italia, e questi, in attesa dei rinforzi da destinare alla difesa di Roma, raggiunse Otranto evitandone giusto in tempo la resa e inducendo i Goti, resi timorosi dalla sua presenza, ad abbandonare l’assedio e a recarsi a Brindisi.

«Saputo di ciò, i Goti che stavano ad assediare quel castello, tolto subito l’assedio, recaronsi a Brindisi che dista da Otranto due giorni di cammino, ed è situata sulla riva del golfo e sprovvista di mura.»2

«Procopio afferma che la città era priva di mura, ma non specifica se le stesse erano state demolite o abbattute per sguarnirla della sua fortificazione o per conquistarla in fase di guerra. Nella circostanza appare probabile che le mura fossero ormai vecchie e cadenti, dato che l’esame della superstite muraglia romana, o meglio terrapieno, che è sul seno di Ponente del porto, nei pressi di corte Capozziello, di fronte a quello che doveva essere l’approdo del porto, dimostra che i Romani si limitarono ad accomodare le preesistenti mura messapiche non costruendone di nuove, almeno da quel lato. Inoltre, non risultano esserci stati assedi o scontri armati dal tempo di Antonio e Ottaviano fino alla guerra gotica. È probabile quindi, che nei cinque secoli intercorsi tra i due eventi, le mura siano state superate dallo sviluppo urbanistico, o che fossero in rovina durante la guerra per essere ormai vecchie.»3

Salpando da Otranto, Belisario si diresse con un ridotto esercito alla volta di Roma assediata dai Goti, mentre Giovanni, l’altro generale bizantino, preferendo spostarsi verso Roma per via terrestre, si attardò con i suoi soldati in Calabria e riuscì a sorprendere i Goti che custodivano Brindisi, attaccandoli di sorpresa grazie alla cattura e al tradimento di uno di loro e obbligandoli a fuggire dalla città.

«A Giovanni, che l’interrogava in che modo lasciandolo vivo potrebbe giovare ai Romani ed a lui, questi rispose che lo avrebbe fatto piombar sui Goti mentre men se l’aspettavano. Giovanni disse che quanto chiedeva non gli sarebbe negato, ma che prima ei doveva mostrargli i pascoli dei cavalli [dei Goti che custodivano Brindisi]; ed avendo anche in ciò acconsentito il barbaro, andò egli con lui, e dapprima trovati i cavalli de’ nemici che pascolavano, saltaron su di essi tutti quelli di loro che trovavansi a piedi, ed erano molti e valorosi, quindi di galoppo corsero contro il campo nemico. I barbari, trovandosi senz’armi, del tutto impreparati e stupefatti pel subitaneo attacco, senza dar niuna prova di coraggio, furono in gran parte uccisi e alcuni pochi scampati recaronsi presso Totila. Giovanni con esortazioni e blandizie cercò di rendere tutti i Calabri bene affetti all’imperatore, promettendo loro grandi beni per parte dell’imperatore stesso e dell’esercito romano. Sollecitamente poi partitosi da Brindisi occupò la città chiamata Canosa, che trovasi nel centro delle Puglie e dista da Brindisi cinque giorni di cammino per chi vada verso l’occaso e verso Roma.»2

Belisario non riuscì a liberare Roma dall’assedio di Totila e questi il 17 dicembre del 546 – corrotte le sentinelle della Porta Asinaria – penetrò in città mentre i Greci già stremati dall’assedio, imprendevano una disordinata fuga. Quindi, lasciato in Roma un limitato contingente di forze, Totila si diresse verso Sud per affrontare le forze del generale Giovanni. Questi, saputolo, pensò bene di non affrontarlo e, rinunciando di fatto a raggiungere Roma ancora assediata dai Goti, preferì tornare a rifugiarsi a Otranto. E così tutto il paese ‘al di qua del golfo’, ad eccezione di Otranto, tornò nuovamente sotto i Goti di Totila.

Note

1 O. Giordano, La Guerra Greco-Gotica nel Salento in Brundisii Res – 1974

2 Procopio Di Cesarea, La guerra Gotica. Testo greco emendato sui manscritti con traduzione italiana a cura di Domenico Comparetti – 1895

3 G. Carito, Lo stato politico economico di Brindisi dagli Inizi del IV Secolo all’anno 670 in “Brundisii Res” – 1976.

#Amalasunta#Atalarico#Brindisi#De bello Gothico#Flavio Belisario#Gianfranco Perri#re Teodato#re Teodorico#Romulo Augustulo#Pagine della nostra Storia#Spigolature Salentine

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Perun" by Andrey Klimenko.

In Slavic folklore, Perun is god of thunder, lightning, justice and war. As early as the 6th century, he was mentioned in "De Bello Gothico", a historical source written by the Eastern Roman historian Procopius. A short note describing beliefs of a certain South Slavic tribe states they "aknowledge that one god, creator of lightning, is the only lord of all: to him do they sacrifice an ox and all sacificial animals".

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ancient Ones, Pt. V: Perun

After we’ve got in touch with Veles (Read here), I want to present you his ‘complementary aspect’ named Perun. This deity got mentioned by countless historical sources, findings and documents. For instance, the 6th century historian Procopius wrote about Perun’s cult in the ‘De bello gothico’. Likewise, the ‘Chronica Slavorum’ said in the 12th century, he got worshipped throughout all Slavic tribes. Therefore, we know, he was the supreme god of the Slavic pantheon. But maybe, Perun had predecessors as the highest deity of the Slavs named Svarog or Rod. Unfortunately, it’s as far as I know undiscovered, why the heads of the pantheon changed over time until the 6th century.

The thunder god’s roots

Supposably, Svarog and Rod were temporally distant ancestors of Perun. Most likely, a closer forefather is the proto-indoeuropean 'Perkwunnos'. The lingual roots may derive from the words 'perkwu' (for 'oak') or later 'per' (for 'to strike'). Those roots were found throughout all Slavic, Baltic and Finno-Ugric tribes. Perun shows many parallels to the Nordic Thor, southern German Donar, the Greek Zeus and even the Indian Indra. These links throughout the cultures and ages are amazing, aren't they?

(Perun fights with a bear shaped Veles. Croatian carving from 8th century. Source: https://wendisches-heidentum.jimdo.com/wendische-g%C3%B6tter/perun/)

Being the supreme Slavic god, Perun was seen as the initiator of thunder and lightning, guardian of the firmament and protector of the world order. He was associated with various plants and trees, for instance oaks and lillies. Winds, rain, hail storms, fire and the mountains also were associated with Perun and thus regarded as sacred. Besides those environmental associations, man-made objects were seen as hallowed by Perun, too. A thunder god's nature, no matter of which culture, always contains aspects of struggle, fighting and war. The Slavs made no exception: their axes, hammers and arrows were dedicated to Perun, so he may lead them to victories in battle or hunting. Especially axes were considered as a symbol of a lightning coming down from the sky and thus had a close relationship to Perun. Therefore, they were contributed as burial objects or worn as jewelry. You can say, the most (and) important aspects of the environment including the everyday life was ensouled and in one way or the other related to the supreme god.

The Sanctuary: Peryn

Perun's main sanctuary was to be found on the West-Russian peninsula Peryn, nearby Veliki Novgorod. The heathen site was excavated in 1951 by Russian archaeologist Valentin Sedov. Since the number '9' is sacred to Perun, it was an influential aspect in the design of the shrine. The sanctuary may have consisted of a wooden idol of Perun, situated on a round platform with eight apsides and an altar each. This can be seen as a representation of Perun and his eight siblings. Sadly, we don't know much about them besides of being mentioned in various traditional Slavic folk songs. After becoming evangelized, the shrine got destroyed and replaced with a christian monastery – but kept it's name, what is really surprising: Usually, the remnants of the pagan past got extinguished as far as possible. This intention has failed, because evidences show, that Perun's cult was practised in some eastern European regions up until the 16th - 18th century, e.g. on the territory that is today Bulgaria.

(This image shows the schematic setup of the Peryn shrine. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:PerunShrineNovgorod.png)

You see, you have to know at least a little about Perun to understand Slavic life, culture and mythology. In my opinion, it's fascinating how persistent Slavic deities turn out, regarding their hidden worship despite evangelization and the following oppression. And we still can keep the pagan spirits and deities alive by reading the old myths, 'meeting' them out in the nature, keeping them in our minds, living by their virtues and knowing (or getting to know) our roots...

#perun#pagan#heathen#slavic#slavic history#mythology#veles#europe#european history#thunder god#slavic mythology#polytheism#slavic polytheism#slavic paganism#russia#baltic#lithuania#estonia#latvia#pomerania#shoresinflames#theancientones

6 notes

·

View notes