#David Evans | Paleontologist | Royal Ontario Museum

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

This Carving from Dinosaur Bone, priced at almost $50,000, was part of a recent seizure of thousands of pounds of fossils that had been illegally excavated from Federal and State Lands in Utah. Photograph By Bureau of Land Management

U.S. Charges Poaching Ring Allegedly Involved in Massive Utah Dinosaur Bone Heist

After Being Excavated and Fashioned into Dinosaur Dig Kits, Carved Figurines, Jewelry, and More for Sale, "Tens of Thousands of Pounds of Dinosaur Bones have Lost Virtually all Scientific Value.”

— By Dina Fine Maron | October 19, 2023

Federal prosecutors today announced charges against four people allegedly involved in a massive dinosaur bone smuggling scheme. Thousands of pounds of dinosaurs and other fossils were secretly excavated from government lands in Utah, according to court documents. Some were sold at gem shows, and others were shipped to China after being mislabeled as construction materials or gems. The poaching and subterfuge, court documents allege, lasted at least from March 2018 to earlier this year.

“By removing and processing these dinosaur bones to make consumer products for profit, tens of thousands of pounds of dinosaur bones have lost virtually all scientific value, leaving future generations unable to experience the science and wonder of these bones,” United States Attorney Trina Higgins said in a press statement.

"It’s certainly a significant volume of dinosaur bones," says David Evans, a paleontologist at the Royal Ontario Museum who’s not involved in the case. He adds that it’s unusual for so much material to be removed from government lands, and that many people likely aren’t aware of the scale of the black market on U.S. dinosaur specimens.

Officials tested more than 1,000 dinosaur bones seized from the residence of Vint and Donna Wade in Utah to determine if they were illegally dug up from Federal Lands. Photograph By Bureau of Land Management

Some of the dinosaur bones were fashioned into commercial products, including dinosaur dig kits, carved figurines, knives, jewelry, and polished bowling ball-like spheres, according to court documents.

Federal agents seized one shipment of dinosaur bones bound for China in December 2022 in Long Beach, California. The 17,000 pounds of fossil material had been mislabeled as industrial stone.

Dinosaur bones shipped to China were allegedly mislabeled as industrial stone or other substances. Photograph By Bureau of Land Management

The items were also sometimes polished and fashioned into dinosaur bone jewelry. Photograph By Bureau of Land Management

Before now, one of the biggest known dinosaur fossil busts occurred in 2006, when 8,000 pounds of fossils—including thousands of dinosaur eggs, petrified pine cones, and prehistoric crabs—were seized by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents at a gem and mineral show in Tucson, Arizona. Those items had been illegally taken from Argentina.

In Utah, dinosaur bones found on private lands may be legally excavated and sold, but it is a crime to dig up and sell fossils discovered on federal or state lands. Charges against the four Utah defendants, who are scheduled to have their initial court appearance later today in Salt Lake City, include conspiracy against the U.S., false labeling, theft of U.S. property, money laundering, and attempted smuggling of goods, among others.

A Dino 🦕 Trafficking Scheme

Beneath Utah’s surface, there’s a rich cache of dinosaur fossils, revealing details about prehistoric animals such as carnivorous allosauruses and spine-backed stegosauruses. Almost three-quarters of the state consists of public lands managed by federal or state agencies, and recent fossil finds there include a huge collection of Utahraptors and an entirely new species, a big-nosed distant relative of Triceratops.

Court documents describing the years-long Utah poaching operation allege that Vint and Donna Wade purchased illegally obtained bones and other fossils to sell at U.S. gem and mineral shows and also to ship to China, and that Jordan Willing and his father Steve Willing trafficked dinosaur bones to China using their company JMW Sales. The documents also allege that two unnamed and unindicted coconspirators illegally excavated fossils from federal lands and sold them off to the Wades.

In total, the Wades sold over $1 million in paleontological material to the Willings, according to the court documents, which were filed in the U.S. District Court in the District of Utah.

The fossil heist also led to $3 million in damages, the federal government claims, including large restoration and repair expenses and the costs of losses to science.

During the years of the alleged smuggling activity, the fossil shipments did sometimes run into problems. One shipment of dinosaur bones that was sent from Scottsdale, Arizona, to China in March 2019 was falsely labeled as items including jasper and wood, but the cargo was ultimately held up in China “due to high radiation levels,” court documents state. The fossilized materials had apparently picked up natural radioactive material over time. (Investigators can sometimes discover the origin of fossils based on radioactive signatures in the specimens that provide clues about where they were buried.)

A scientist tests a dinosaur bone for radiation to help determine its origin. Over time, fossils may pick up naturally occurring radiation from their environment which can help investigators determine where they'd been buried. Photograph By Bureau of Land Management

Each radiation-tested bone was labeled with a unique identifier, and a circle was added to mark where it had been sampled. This fossil had been priced at $4,500. Photograph By Bureau of Land Management

Paleontologists typically remove dinosaur bones using a methodological process designed to limit damage and preserve evidence found in the fossils and their surroundings—information about when dinosaurs lived, what species they were, and sometimes even how they behaved.

Amateur diggers hunting for recognizable body parts to sell, however, generally do not take such care. Federal prosecutors claim that the loss to science from this poaching ring is largely incalculable.

#Science#Wildlife Watch#Poaching#Dinosaur Bone Heist#Utah | US 🇺🇸#Dinosaur Dig Kits | Carved Figurines | Jewelry#Dina Fine Maron | National Geographic#Consumer Products | Profit#China 🇨🇳#United States Attorney | Trina Higgins#David Evans | Paleontologist | Royal Ontario Museum#China 🇨🇳 | Long Beach 🏖️ | California | US 🇺🇸#Fossils | Dinosaur Eggs 🥚 | Petrified Pine 🌲 Cones | Prehistoric Crabs#Tucson | Arizona.#Argentina 🇦🇷#Carnivorous Allosauruses | Spine-Backed Stegosauruses#Triceratops#Vint | Donna Wade#Wades | Willings#Scottsdale | Arizona

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Malignant bone cancer has been diagnosed in a dinosaur for the first time ever

https://sciencespies.com/nature/malignant-bone-cancer-has-been-diagnosed-in-a-dinosaur-for-the-first-time-ever/

Malignant bone cancer has been diagnosed in a dinosaur for the first time ever

A palaeontologist, a medical pathologist, and an orthopaedic surgeon walk into a museum. No, it’s not the start of a joke, but the research team that has now diagnosed the first confirmed case of aggressive bone cancer in a dinosaur.

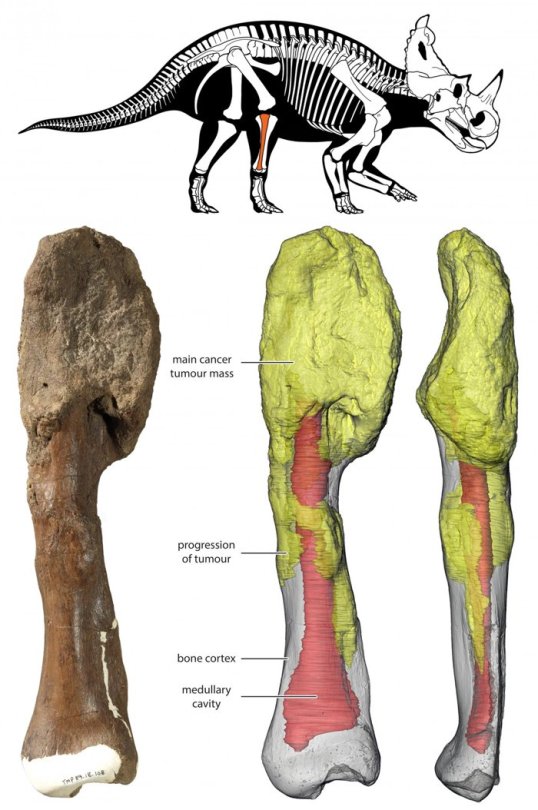

The specimen in question is a fossilised shin bone from Centrosaurus apertus, a plant-eating horned dinosaur that lived and died roughly 76 million years ago.

What looked – at least on first impression – like a poorly healed fracture turned out to be a tumour engrossing the upper half of the animal’s shin bone, or fibula. The centrosaurus was diagnosed with an osteosarcoma; it’s the most common type of bone cancer in humans, but marks the first confirmed case of any malignant cancer we’ve found in a dinosaur.

“Here, we show the unmistakable signature of advanced bone cancer in [a] 76-million-year-old horned dinosaur – the first of its kind,” said pathologist Mark Crowther. “It’s very exciting.”

The shin bone, with the main tumour mass in yellow. (Danielle Dufault/Royal Ontario Museum/McMaster University)

In humans, osteosarcomas often affect growth-spurting teenagers and young adults. If an osteosarcoma metastasises – grows beyond the bone – it most often spreads to the lungs, but can also form tumours in other bones, and even the brain.

However curious we are about the evolution of diseases such as cancer, soft tissues like tendons, ligaments, bone marrow and tumours, are rarely preserved in fossils. Given a few years – let alone a million – these tissues would decay. So even if dinosaurs were regularly struck down by cancer, any diagnostic samples are going to be hard to find.

Scientists have come across similar cancer-like symptoms on dinosaur fossils before. Unusual lesions in the tail vertebrae of a young hadrosaur resembled a condition called Langerhans cell histiocytosis, a complex cancer which leaves room for debate over its manifestation. In the case of this most recent discovery, the malignancy is far more clear.

The cancer-stricken fossilised shin bone of C. apertus was unearthed in Dinosaur Park Formation in Alberta, Canada back in 1989, and had been stored at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, outside of Calgary, until its recent reanalysis.

Cross sections of the C. apertus bone were taken first with a CT scanner, the same machine used to identify bone fractures and tumours in people. The X-ray image ‘slices’ were reconstructed to see how the tumour grew through the fossilised bone.

In fact, it had spread through the bone quite extensively, which the team of medical specialists took as a sign that this centrosaur lived with its cancer for quite some time.

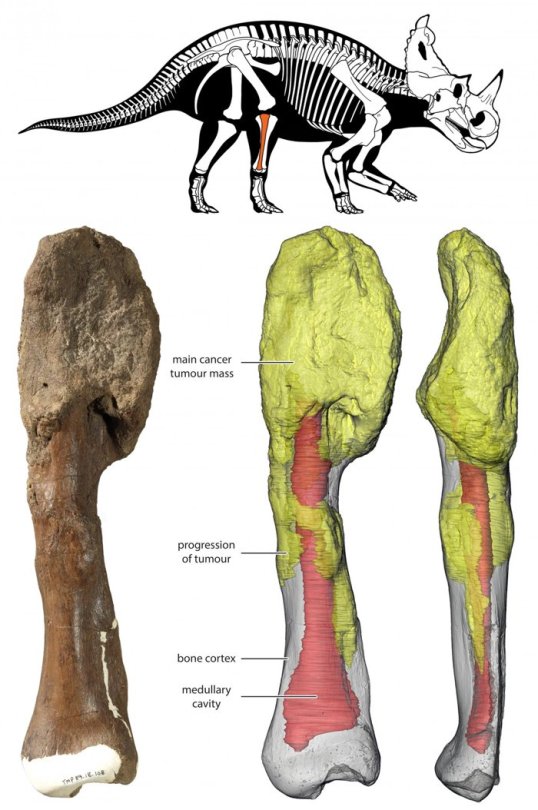

Artist’s impression of Centrosaurus apertus. (Royal Ontario Museum/McMaster University)

“This discovery reminds us of the common biological links throughout the animal kingdom and reinforces the theory that osteosarcoma tends to affect bones when and where they are growing most rapidly,” said Seper Ekhtiari, an orthopaedic surgeon-in-training at McMaster University in Toronto, who examined the fossil.

As the cancer was so advanced, the researchers think it might have spread to other parts of the dinosaur’s body, but we don’t have any of those tissue samples – such as the spongy lungs – from this ancient animal to make sure.

“The shin bone shows aggressive cancer at an advanced stage,” said paleontologist David Evans. “The cancer would have had crippling effects on the individual and made it very vulnerable to the formidable tyrannosaur predators of the time.”

After imaging the cancerous shin bone, thin sections were carefully sliced off the fossil and compared to a normal C. apertus fibula, along with one case of human osteosarcoma, from a 19-year-old man who had it in his lower leg.

In their paper, the authors note that ”a similarly advanced osteosarcoma in a human patient, left untreated, would certainly be fatal.”

But they suspect the dinosaur died with its herd mates, possibly in a sudden flood event, because the fossil was found in a massive bed of Centrosaurus bones.

“The fact that this plant-eating dinosaur lived in a large, protective herd may have allowed it to survive longer than it normally would have with such a devastating disease,” Evans said.

And when we often marvel at the age of dinosaurs and their size, big and small, this latest medical discovery brings the plight of the dinosaurs a little closer to home.

“Evidence suggests that malignancies, including bone cancers, are rooted quite deeply in the evolutionary history of organisms,” the authors concluded. Yes, even dinosaurs.

The study is published in medical journal The Lancet Oncology.

#Nature

2K notes

·

View notes

Quote

There’s an old joke in paleontology that you’re not a real paleontologist until you’ve broken something important.

Dr. David Evans, Head of Dinosaur Research at the Royal Ontario Museum

#paleo#paleontology#geology#paleontology problems#dino#dinosaur#dinosaurs#dr david evans#royal ontario museum#dino hunt#dino hunt quote#geo#bones#bone#this is so true and such a relief to hear

237 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Research Shows Dinosaurs Suffered From Malignant Cancer, Too

August 4, 2020

Heard on All Things Considered

Scientists in Canada have diagnosed malignant cancer for the first time in a dinosaur, a Centrosaurus apertus from 76 to 77 million years ago.

Scientists from Canada's Royal Ontario Museum and McMaster University say they have identified malignant bone cancer in a dinosaur for the first time.

The new research was published earlier this week in the journal The Lancet Oncology.

The diagnosis? Osteosarcoma — an aggressive bone cancer — in the fibula, or lower leg bone, of a Centrosaurus apertus, a plant-eating, single-horned dinosaur that lived 76 to 77 million years ago.

The discovery opens up new understanding about other diseases that may have developed in dinosaurs, among other aspects of dinosaur life.

"What this study shows, because we found bone cancer at quite an advanced stage, is that dinosaurs were not only afflicted by bone cancer but probably all sorts of other cancers that we see in vertebrates today," says David Evans, a paleontologist at the Royal Ontario Museum and one of the study's lead researchers.

Though the diagnosis is new, the bone was discovered in 1989. That's when a crew from the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Drumheller, Canada, discovered the fibula in a massive bone bed in Alberta, Canada.

The fibula was badly malformed, but scientists initially assessed it as a healing broken bone, and that the odd shape was a fracture callous.

The bone sat in the museum's collection until 2017, when a team led by Evans and Mark Crowther, a professor of pathology at McMaster University, began to search through the hundreds of injured or partially healed bones on a mission.

"We basically went on a hunt for dinosaur cancer," Evans says.

Evans, Crowther and Snezana Popovic, an osteopathologist at McMasters, combed through hundreds of bones before they found the unusually malformed fibula to investigate for signs of cancer.

They brought in specialists in an array of fields, including pathology, radiology, orthopedic surgery and paleopathology, to examine and diagnose the suspected tumor.

"The approach we took in this case was very similar to how we approach a patient that comes in with a new tumor, and we don't know what kind of tumor it is," says Seper Ekhtiari, an orthopedic surgery resident at McMaster University who worked on the team.

They were able to visualize the progression of cancer through the bone by performing high-resolution CT scans of the fibula and examining thin sections of the bone at the cellular level under a microscope.

The team confirmed the diagnosis of osteosarcoma by comparing the bone to the fibula of a healthy centrosaurus and that of a human with osteosarcoma.

Two views of the Centrosaurus apertus shin bone (fibula) with malignant bone cancer (osteosarcoma). The extensive invasion of the cancer throughout the bone (yellow) suggests that it persisted for a considerable period of the dinosaur's life and may have spread to other parts of the body prior to death.

While this is the first identified instance of osteosarcoma in a dinosaur, Ekhtiari says it makes sense that a cancer associated with rapid bone growth would have plagued the dinosaurs.

"One of the ways they got to such massive sizes is that they grew extremely rapidly from the time when they were born," Ekhtiari says. "So finding this in a dinosaur is not surprising." In fact, he says, bone cancer "is probably more common than we think, or more common than we have found so far."

Crowther, the pathologist, adds that their finding suggests that dinosaurs likely suffered from other diseases that affect the bones — like tuberculosis and osteomyelitis.

Even though it points to a potential cause of death for dinosaurs, the cancer discovery also has given insight into how they lived and survived.

Take the diseased centrosaurus. While it would have been severely hobbled by the advanced stage of cancer found in its fibula, it didn't die from the disease, nor was it picked off by a predator like a Tyrannosaurus rex. Its bones were found in a massive bone bed, which scientists believe is the partial remains of a large herd drowned by a flood.

"The cancer was able to progress to the stage that it did because of the safety in numbers of the herd that it lived in," says Evans, the paleontologist.

While the discovery opens up many new doors in paleontology and pathology, one of the biggest impacts of the study might be a shift in the way we perceive dinosaurs.

"We often think of dinosaurs as sort of mythical, powerful creatures, and I think this discovery really underscores that they can be afflicted by diseases that we see around us today, even horrible fatal cancers," Evans says. "I think in an odd way it brings them even more back to life."

In an earlier version of this story, David Evans is quoted as saying the study shows that dinosaurs were probably afflicted by "all sorts of other cancers that we see in invertebrates today." In fact, he said "in vertebrates today."

0 notes

Photo

Just a reminder that Triceratops was HUGE! 🐘 On the left is a femur of an adult Triceratops and on the right is a femur from an adult 6,000 kg male African elephant! Palaeontologist Shino Sugimoto for scale. 🤯 . Weight estimates of Triceratops suggest it was almost twice as heavy as an average African elephant. 🐘🐘 . Posted @withregram • @ycm_geology . Photo by my fellow palaeontologist, David Evans (@ David Evans on Twitter), taken at the Royal Ontario Museum. . Reposted by - @dean_r_lomax #fossil #fossilhunter #fossils #paleontology #palaeontology #paleontologist #nature #Jurassic #dinosaur #jurassicpark #prehistoric #ancient #ammonite #evolution #extinct #animals #geology #collecting #dinosaursofinstagram #fossilhunting #triceratops #dinosaurs #ycmgeology #chemcafe #dsr #decoding_scientific_research https://www.instagram.com/p/CE2IY_kHK_j/?igshid=yy9vuh74lfah

#fossil#fossilhunter#fossils#paleontology#palaeontology#paleontologist#nature#jurassic#dinosaur#jurassicpark#prehistoric#ancient#ammonite#evolution#extinct#animals#geology#collecting#dinosaursofinstagram#fossilhunting#triceratops#dinosaurs#ycmgeology#chemcafe#dsr#decoding_scientific_research

0 notes

Link

Scientists from the Royal Ontario Museum have recently discovered the fossil of a 75-million-year-old species of armoured dinosaur, or ankylosaur, which was unusually well-preserved — and oddly familiar to movie buffs.

Meet Zuul crurivastator — destroyer of shins — whose discovery is being discussed in the Royal Society Open Science journal.

The name was inspired by the Ghostbusters villain Zuul, says Victoria Arbour, paleontologist and postdoctoral fellow at the ROM and University of Toronto.

"Me and my co-author David Evans were batting around ideas for what to name it, and I just half-jokingly said, 'It looks like Zuul from Ghostbusters,'" she said. "Once we put that out there we couldn't not name it that."

Continue Reading.

#ROM#royal ontario museum#paleontology#ghost busters#zuul#palaeontology#Zoology#biology#science#fossil#fossils#stem#Zuul crurivastator

349 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“[While] rationalism [has] forced the dragon’s retreat into fable, the mythos and its attendant images nonetheless [remain.] Why else are the paleontologists so often guilty of emphasizing the supposed menace of their dinosaur discoveries at the expense of scientific objectivity? Why did they from the start turn their fossil-lizard discoveries into monsters? For behind the apparently clinical pseudo-Greek and Latin names for the animals lie bastard coinings, more dramatic than descriptive: hence, Titanosaurus (“titanic reptile”), Teratosaurus (“monster lizard”), and Gorgosaurus (“horrible lizard,” a la the Gorgon, Medusa), for example. Indeed, founding father of paleontology Sir Richard Owen began the trend: his Greek term dinosauria itself, meaning “terrible [or terror] lizards,” seems rather subjective.”

– Michael Delahoyde, “Medieval Dragons and Dinosaur Films,” Popular Culture Review 9.1 (February 1998): 17-30.

Paleontologists and paleo-artists occasionally deride pop-culture’s tendency to portray dinosaurs as monsters as oppose to actual animals. However as English Professor Michael Delahoyde of Washington State University has astutely pointed out, if this is a problem it’s one that begins with the paleontologists themselves. Case in point, this week the paleontological world has been abuzz about ankylosaurs. Canadian ankylosaurs to be precise. First a beautifully preserved fossil skeleton of a nodosaur has been unveiled by the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Canada. The skeleton is so well preserved it looks like a statue.

The other story concerns a new species of ankylosaur which was actually discovered back in 2014 in a Montana quarry but whose bones were subsequently acquired by the Royal Ontario Museum. It’s this second find which has been the bigger news-maker, propelled beyond the pages of National Geographic and into mainstream news headlines undoubtedly in part because of paleontologist Victoria Arbour and her colleague David Evans’ decision to name this new species Zuul crurivastator, or “Zuul, destroyer of shins,” after the hell-hound seen in 1984’s GHOSTBUSTERS (Dir. Ivan Reitman). This isn’t the first dinosaur to be named after a movie monster. In 1997 paleontologist Kenneth Carpenter named a Trassic theropod Gojirasaurus after the Japanese movie monster Godzilla, and in 2006 paleontologist Bob Bakker and Robert Sullivan dubbed a new species Pachycephalosauridae Dracorex hogwartsia, or “Dragon King of Hogwarts,” in honor of the Harry Potter series.

Point being, if paleontologists want us to stop thinking of dinosaurs as monsters perhaps they should stop naming them as if they are. Only, of course, I don’t want them to. Though admittedly perhaps it was a bit silly for a team of French paleontologists to name a recently analyzed new species of Brachiosaurus after a wyvern – I mean I don’t think you can get any further away from draconian anatomy then a gigantic sauropod.

Art of Zuul crurivastator by Danielle Dufault, © Royal Ontario Museum

#dinosaur#dinosaurs#zuul crurivastator#zuul#ghostbusters#awesomebro#palentology#paleoart#ankylosaurus#canada

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

“Scientists from the Royal Ontario Museum have named a newly discovered dinosaur species after the Ghostbusters villain Zuul. CBC News reports a crew of private excavators accidentally bumped into the well-preserved ankylosaur skeleton while unearthing a nearby tyrannosaurus in the Judith River Formation in Montana. The plant-eating species, officially named Zuul crurivastator, is said to be 75 million years old. Due to the dinosaurs's strikingly similar appearance to Zuul, with its rounded, short snout and horns located behind its eyes, the Royal Ontario Museum's paleontologist and postdoctoral fellow Victoria Arbour and her colleague decided to name it after the villain from Ghostbusters, who originaly inhabits Sigourney Weaver's character Dana before transforming into one of Gozer's hellhounds in the original film. ‘Me and my co-author David Evans were batting around ideas for what to name it, and I just half-jokingly said, 'It looks like Zuul from Ghostbusters,' Arbour said. ‘Once we put that out there we couldn't not name it that.’ Since they were able to retrieve the dinosaur's full skeleton, including the skull, tail, body and preserved soft tissue, the scientists intend to further research and discover more about the new species”, from Ign, link above!

#royal ontario museum#sigourney weaver#cbc news#skeleton#victoria arbour#gozer#ign#montana#judith river formation#david evans#paleontologist#ankylosaur#dinosaur#zuul#ghostbusters#zuul crurivastator#new species

0 notes

Text

Dinosaurs Suffered From Cancer, Too

https://sciencespies.com/nature/dinosaurs-suffered-from-cancer-too/

Dinosaurs Suffered From Cancer, Too

In most cases, paleontologists are at least 66 million years too late to give dinosaurs medical exams. The living animals perished long, long ago. But every now and then, fossil hunters uncover a bone with signs of injury or disease–what experts call pathologies. And in the case of a particular bone found in the roughly 75 million-year-old rock of Alberta, a medical examination has revealed that dinosaurs suffered from a cancer that afflicts humans today.

A multidisciplinary team led by a paleontologist and a pathologist studied the bone inside and out, examining everything from the outside shape to the inner microscopic structure. In the end, the experts arrived at a diagnosis of osteosarcoma–a malignant bone cancer that afflicts about 3.4 out of every million people worldwide. The team’s new study, published today in The Lancet, provides the most detailed evidence yet for cancer in a dinosaur.

Discovering osteosarcoma in a dinosaur has implications for the evolutionary origins and history of cancer. “If humans and dinosaurs get the same kinds of bone cancers,” says George Washington University paleontologist Catherine Forster, “then bone cancers developed deep in evolutionary history, before the mammal and reptile lineages split 300 million years ago.”

The pivotal bone wasn’t an isolated find, but part of an enormous bonebed containing the remains of dozens upon dozens of the horned dinosaur Centrosaurus. A huge herd of these horned dinosaurs perished together, probably in a flash flood that ripped along an ancient coast. The Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology excavated the site in 1989, and among their finds was a fibula, or lower leg bone, that looked strange. The bone showed some kind of injury, perhaps a healed fracture, and was filed away in the museum’s collections.

The horned dinosaur, Centrosaurus apertus, shin bone with malignant bone cancer

(Courtesy of Royal Ontario Museum.

© Royal Ontario Museum/McMaster University )

Years later, Royal Ontario Museum paleontologist David Evans happened to meet McMaster University pathology specialist Mark Crowther at a social event. The two got to talking about bone cancer in dinosaurs, and, Evans recalls, “I said that our best shot to find dino cancer was to go to the Royal Tyrrell Museum collections and search through their large holdings of pathological dinosaur bones.”

Evans and Crowthers’ search paid off. The researchers pored over the Royal Tyrrell collections with other experts in both dinosaurs and disease. The team surveyed hundreds of fossils and rediscovered the Centrosaurus bone. The injury to the bone didn’t look like a break. It looked like a good candidate for Cretaceous cancer. Experts in musculoskeletol oncology and human pathology examined the bone in detail, from its outer physical appearance to its inner structure using a high-resolution X-ray CT scan, and confirmed a diagnosis of osteosarcoma.

Other paleontologists have found cancer in dinosaur bones before, but, Evans notes, this is the first time a malignant cancer has been confirmed through multiple lines of evidence.

The images in the new study appear to represent a tumor, says Montana State University paleopathologist Ewan Wolff, but he adds “I would like to see comparison to animals more closely related to dinosaurs.”

Living dinosaurs–birds–will be key to further testing the conclusion and identifying other cases. Osteosarcoma has been found in birds from robins to pelicans, Wolff points out, and these avian comparison points may help refine our understanding of how osteosarcoma has affected dinosaurs through time.

“When paleontologists see little blips and bumps on dinosaur bones, we often just assume that it must have been from a traumatic injury,” says Andrew Farke of the Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology. By contrast, Farke says, the new research provides a high level of evidence for the cancer diagnosis and offers a reminder to paleontologists to check their assumptions about paleopathologies.

A Centrosaurus reconstruction

(Fred Wierum via Wikimedia Commons under CC BY-SA 4.0)

The diagnosis was definitely bad news for the Centrosaurus. “Malignant cancers are aggressive and can spread to other parts of the body, and as such they are often fatal,” Evans says. In this case, the bone cancer appears so advanced that it had likely spread to other points in the body.

Not that this dinosaur perished because of its illness. The Centrosaurus died in a coastal flood as part of a massive herd. The fact that the dinosaur survived for so long might tell us something about the benefits of dinosaur social life.

Large tyrannosaurs such as Daspletosaurus fed on Centrosaurus. Much like many modern predators–from hyenas to sharks–dinosaurian carnivores probably picked off sick or injured animals that were easier to catch. “However,” Evans says, “living within a large herd provided safety in numbers and likely allowed it to avoid predation as the cancer progressed, allowing it to survive longer with this debilitating cancer than it would have on its own.”

When afflicted by illness, Farke notes, animals are often much tougher than we think they are. Still, herding may have offered benefits to the injured. “If you are a sick horned dinosaur, being able to blend in with others of your kind will probably buy you some time versus being out solo,” he says.

While this discovery is, as yet, a single occurrence, the find helps to paint a richer picture of dinosaur lives. “Dinosaurs can seem like mythical creatures, but they were living, breathing animals that suffered through horrible injuries and diseases,” Evans says, “and this discovery certainly makes them more real and helps bring them to life in that respect.”

#Nature

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Feathered Carnivorous Dinosaur Found in New Mexico

https://sciencespies.com/nature/new-feathered-carnivorous-dinosaur-found-in-new-mexico/

New Feathered Carnivorous Dinosaur Found in New Mexico

A new carnivorous feathered dinosaur, coyote-sized with razor-sharp teeth and claws, has been discovered in New Mexico’s San Juan Basin. The small but formidable predator called Dineobellator would have stalked these open floodplains 70 million years ago.

Steven Jasinski, a paleontologist at the State Museum of Pennsylvania and lead author of the study in Scientific Reports, says Dineobellator is a new species from the Late Cretaceous (70-68 million years ago) that belongs to dromaeosaurid, a group of clawed predators closely related to birds. These rare fossils have features that suggest raptors were still trying out new ways to compete even during the dinosaurs’ last stand—the era just before the extinction event that wiped them out 66 million years ago. “This group was still evolving, testing out new evolutionary pathways, right at the very end before we lost them,” Jasinski notes.

The bones from this new specimen bear the scars of a combative lifestyle and suggest some unusual adaptations of tail and claw that might have helped Dineobellator notohesperus hunt and kill. The name Dineobellator pays homage to the dino’s tenacity and that of the local Native American people. Diné means ‘the Navajo people,’ while bellator is the Latin word for warrior.

“Due to their small size and delicate bones, skeletons of raptors like Dineobellator are extremely rare in North America, particularly in the last 5 million years of the Age of Dinosaurs,” says David Evans, a paleontologist at the Royal Ontario Museum and the University of Toronto, who wasn’t involved in the study. “Even though it is fragmentary, the skeleton of Dineobellator is one of the best specimens known from North America for its time, which makes it scientifically important and exciting.”

Dineobellator notohesperus outline and skeletal reconstruction.

(Steven Jasinski)

Over four field seasons between 2008 and 2016, Jasinski and colleagues unearthed 20 fossils from a single creature’s skeleton, including parts of the skull, teeth, fore and hind legs, ribs and vertebrae. Dineobellator’s forearms feature quill knobs, bumps found on the bones of dinosaurs or birds that reveal where feathers once attached. Like its relative Velociraptor, this newfound animal was about the size of a coyote or large barnyard turkey, Jasinski says, but probably punched above its weight as a predator.

The fossils indicate the dinosaur suffered a rib injury, but bone regrowth shows that it survived and healed. But this Dineobellator wasn’t so fortunate with an injury to its hand claw. “The hand claw injury doesn’t show any bone regrowth, so it looks like it happened either right at death or just before,” Jasinski says.

Dineobellator’s unusual features include its forelimbs, which appear to be an uncommon shape that would have maximized muscle power to make them very strong, a trait Jasinski suggests was accentuated by claws on both hands and feet. “Their grip would have been far stronger than what we see in the other members of this group,” he says.

Fossils from the animal’s tail also suggest an intriguing anatomy. Most similar dinosaurs have stiff tails reinforced with bones or tendons that would have helped with balance and aided running. “What these animals have … is a lot of mobility at the base of the tail where it attaches to the hips,” Jasinski says. “If you think about how a cheetah attacks, their tail is whipping all over the place because they have to change directions very quickly so it increases agility. That’s what this animal would have been able to do, that others in its group would not. It makes this animal agile and a very good pursuit predator.”

Reconstruction of Dineobellator notohesperus standing over a nest by Mary P. Williams

(Steven Jasinski)

Paleontologist Alan Turner, of the American Museum of Natural History and Stony Brook University, cautions that without a full skeleton, the remains are too fragmentary and scattered to make serious inferences about Dineobellator’s tail or claws. “A couple of vertebrae do give you a glimpse of what the tail looked like, but if you don’t have an entire tail, or the part of the backbone that the tail attaches to, I’d be reticent to make a definitive statement about tail mobility.” But, he says, this study fills in gaps for a period that’s lacking in samples and offers a glimpse into the dromeosaurs of the time.

David Evans echoed that point. “More complete fossils and comparative functional analyses are needed to demonstrate whether Dineobellator was a particularly strong or adept predator. Dineobellator shows us more skeletons are out there, waiting to be found,” he says.

Evans agrees with the study authors that the fossils in hand demonstrate that close relatives of Velociraptor were diversifying during the last days of the Age of the Dinosaurs. “Importantly, it shows that the raptors in the southern part of western North America were distinct from those in the north, and suggests these differences may have been driven by different local ecosystem conditions.”

Photo from the original discovery of Dineobellator notohesperus pointing out the hand claw among other bone fragments

(Steven Jasinski)

Other excavations have given scientists a reasonably good idea of the menagerie of animals that shared Dineobellator’s ecosystem, an open floodplain habitat in modern-day New Mexico that was growing increasingly distant from the receding shoreline of the Western Interior Seaway.

Ojoceratops, a horned beast very much like Triceratops, was fairly common as was long-necked sauropod Alamosaurus. “We have evidence of a small tyrannosaurid, something like T. rex but considerably smaller,” Jasinski says. “There are duck-billed dinosaurs, hadrosaurids, that are relatively common, there are lots of turtles, crocodilians have been common all over the place, and evidence of early birds there as well that would have been living with this thing.”

As for how Dineobellator and its kin fit in, Turner says that’s a matter of speculation. “Just size-wise, your average North American or Asian dromeosaur might be along the lines of foxes or coyotes,” he notes, adding that like those mammals, Dineobellator might have existed in substantial numbers as a kind of ubiquitous predator. “That sort of general predatory niche is probably where a lot of these dromeosaurs were falling out.”

While the individual Dineobellator in the study appears to have met a violent end it seems likely that it and its relatives also enjoyed their share of success. “They have sharp teeth and nasty claws on their feet,” Turner notes. “They aren’t these big intimidating things, but I still wouldn’t want to have a run-in with one.”

#Nature

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Malignant bone cancer has been diagnosed in a dinosaur for the first time ever

https://sciencespies.com/nature/malignant-bone-cancer-has-been-diagnosed-in-a-dinosaur-for-the-first-time-ever/

Malignant bone cancer has been diagnosed in a dinosaur for the first time ever

A palaeontologist, a medical pathologist, and an orthopaedic surgeon walk into a museum. No, it’s not the start of a joke, but the research team that has now diagnosed the first confirmed case of aggressive bone cancer in a dinosaur.

The specimen in question is a fossilised shin bone from Centrosaurus apertus, a plant-eating horned dinosaur that lived and died roughly 76 million years ago.

What looked – at least on first impression – like a poorly healed fracture turned out to be a tumour engrossing the upper half of the animal’s shin bone, or fibula. The centrosaurus was diagnosed with an osteosarcoma; it’s the most common type of bone cancer in humans, but marks the first confirmed case of any malignant cancer we’ve found in a dinosaur.

“Here, we show the unmistakable signature of advanced bone cancer in [a] 76-million-year-old horned dinosaur – the first of its kind,” said pathologist Mark Crowther. “It’s very exciting.”

The shin bone, with the main tumour mass in yellow. (Danielle Dufault/Royal Ontario Museum/McMaster University)

In humans, osteosarcomas often affect growth-spurting teenagers and young adults. If an osteosarcoma metastasises – grows beyond the bone – it most often spreads to the lungs, but can also form tumours in other bones, and even the brain.

However curious we are about the evolution of diseases such as cancer, soft tissues like tendons, ligaments, bone marrow and tumours, are rarely preserved in fossils. Given a few years – let alone a million – these tissues would decay. So even if dinosaurs were regularly struck down by cancer, any diagnostic samples are going to be hard to find.

Scientists have come across similar cancer-like symptoms on dinosaur fossils before. Unusual lesions in the tail vertebrae of a young hadrosaur resembled a condition called Langerhans cell histiocytosis, a complex cancer which leaves room for debate over its manifestation. In the case of this most recent discovery, the malignancy is far more clear.

The cancer-stricken fossilised shin bone of C. apertus was unearthed in Dinosaur Park Formation in Alberta, Canada back in 1989, and had been stored at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, outside of Calgary, until its recent reanalysis.

Cross sections of the C. apertus bone were taken first with a CT scanner, the same machine used to identify bone fractures and tumours in people. The X-ray image ‘slices’ were reconstructed to see how the tumour grew through the fossilised bone.

In fact, it had spread through the bone quite extensively, which the team of medical specialists took as a sign that this centrosaur lived with its cancer for quite some time.

Artist’s impression of Centrosaurus apertus. (Royal Ontario Museum/McMaster University)

“This discovery reminds us of the common biological links throughout the animal kingdom and reinforces the theory that osteosarcoma tends to affect bones when and where they are growing most rapidly,” said Seper Ekhtiari, an orthopaedic surgeon-in-training at McMaster University in Toronto, who examined the fossil.

As the cancer was so advanced, the researchers think it might have spread to other parts of the dinosaur’s body, but we don’t have any of those tissue samples – such as the spongy lungs – from this ancient animal to make sure.

“The shin bone shows aggressive cancer at an advanced stage,” said paleontologist David Evans. “The cancer would have had crippling effects on the individual and made it very vulnerable to the formidable tyrannosaur predators of the time.”

After imaging the cancerous shin bone, thin sections were carefully sliced off the fossil and compared to a normal C. apertus fibula, along with one case of human osteosarcoma, from a 19-year-old man who had it in his lower leg.

In their paper, the authors note that ”a similarly advanced osteosarcoma in a human patient, left untreated, would certainly be fatal.”

But they suspect the dinosaur died with its herd mates, possibly in a sudden flood event, because the fossil was found in a massive bed of Centrosaurus bones.

“The fact that this plant-eating dinosaur lived in a large, protective herd may have allowed it to survive longer than it normally would have with such a devastating disease,” Evans said.

And when we often marvel at the age of dinosaurs and their size, big and small, this latest medical discovery brings the plight of the dinosaurs a little closer to home.

“Evidence suggests that malignancies, including bone cancers, are rooted quite deeply in the evolutionary history of organisms,” the authors concluded. Yes, even dinosaurs.

The study is published in medical journal The Lancet Oncology.

#Nature

0 notes

Text

Paleontologists Debate Whether New Research Found Signs of DNA in Dinosaur Fossil

https://sciencespies.com/news/paleontologists-debate-whether-new-research-found-signs-of-dna-in-dinosaur-fossil/

Paleontologists Debate Whether New Research Found Signs of DNA in Dinosaur Fossil

About 75 million years ago, a nest of plant-eating dinosaurs called Hypacrosaurus stebingeri died in what’s now Montana. Their fossils were found in the 1980s, and now an international team of scientists has presented evidence that the old bones contain traces of genetic material.

The paper published in National Science Review takes a close look at skull shards that would have been made of soft cartilage, instead of bone, in the young dinosaurs. The discovery is small in size, but hugely controversial among paleontologists: what appears to be microscopic cells, the building blocks of complex life, with dark clumps in the middle. A zoomed-in look at one possible cell’s dark spot reveals what the researchers suspect is genetic material.

Study author Alida Bailleul, a paleontologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, first found the microscopic orbs in 2010 while a student at the Museum of the Rockies, and quickly recognized their resemblance to cells. “I freaked out a little bit—moving away from the microscope, thinking, moving back to the microscope,” she tells Michael Greshko at National Geographic. “I was like, Oh my god, that can’t be, there’s nothing else they can be!”

Photographs of the suspected cells in the nestling’s skull fragment. On the left, it appears that two cells are dividing, and the dark region resembles a cell nucleus, where DNA is stored. In the middle, what appears like strands of DNA. On the right, dye fluoresces red indicating chemicals like DNA.

(©Science China Press, Photo by Alida Bailleul and Wenxia Zheng)

After getting a second opinion from Mary Schweitzer, a paleontologist at North Carolina State University and first author on the paper, the team moved forward analyzing their find. It was surprising because tiny structures like cells and DNA—the molecular twisted-ladder that carries a cell’s blueprint—are notoriously fragile. High heat or acidity can destroy them, and so they require a lot of upkeep while an animal is alive, and when it dies, the delicate bits are at the whims of the environment.

If the researchers have found fossilized cells and DNA, they would be several tens of times older than both any found before, and the theoretical preservation limits of the materials, paleontologist Evan Saitta, who works at the Integrative Research Center at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, explains to George Dvorsky at Gizmodo.

Cartilage lacks pores, so Bailleul and her colleages suggest that it may have defended the microscopic structures from the outside environment, the researchers say.

“Fossilized, calcified cartilage may be an ideal place to search for exceptionally preserved biomolecules in other fossils, as this tissue may be less prone to contamination and internal decay than bone,” Royal Ontario Museum paleontologist David Evans, who wasn’t involved in the new study, tells National Geographic. “In calcified cartilage, the cells become trapped and isolated in their matrix and are more likely to be preserved in a sealed micro-environment.”

To check their find, the researchers applied a dye to the fossils that sticks to DNA and fluoresces red. Then, they dyed living emu cells and compared the two. Although it was much fainter than the dye in the emu’s cells, the fossil’s dye stuck to something.

“I’m not even willing to call it DNA because I’m cautious, and I don’t want to overstate the results,” Schweitzer tells National Geographic. “There is something in these cells that is chemically consistent with and responds like DNA.”

The researchers would have to extract the DNA-like stuff from the fossil and try to read its chemical code in order to definitively confirm whether or not it’s DNA, but based on their results, the pieces are too short to read. It also may have become extra stable by binding to itself and other molecules nearby, a reaction called cross-linking, they tell National Geographic.

Skeptics like University of Bristol paleontologist Michael Benton aren’t convinced that what the researchers found originated in the skull fragment at all. Writing on the Conversation, Benton suggests that the potential DNA could have come from modern contamination. That’s what happened with many claims of ancient DNA in the 1990s, though those studies used a different testing technique than Schweitzer’s team.

He also points out that Schweitzer has co-authored several studies on soft tissue fossils that have been controversial in their field. Saitta’s doubt also comes from the fact that dyes like those used by the researchers sometimes give false positives, indicating their target is present when it’s actually not, he tells Gizmodo.

Schweitzer disagrees, and tells Gizmodo that skeptics “can say what they want,” adding that “As far as I know, [the dyes] DAPI and PI do not bind to any other molecule except DNA.” Unless the skeptics can come up with a better explanation for the data, she’s confident in her team’s conclusions.

“This research is still very much in its infancy,” Evans tells National Geographic. “But the possibilities are absolutely thrilling if we suspend our disbelief, dig into the data, and continue to test and refine our ideas about molecular preservation in fossils.”

#News

0 notes

Text

How to Weigh a Dinosaur

https://sciencespies.com/news/how-to-weigh-a-dinosaur/

How to Weigh a Dinosaur

Weighing a dinosaur is no easy task. These extinct creatures were massive, and for the most part, all that remains are their bones, as their organs and skin have long since decomposed. However, new research has found more than one way to measure the mass of these giant creatures that roamed the planet millions of years ago.

In a paper entitled “The Accuracy and Precision of Body Mass Estimation in Non-avian Dinosaurs,” published this month in the scientific journal Biological Reviews, a team of scientists from the University of New England’s Palaeoscience Research Centre evaluated the two existing ways scientists approach calculating how much a Tyrannosaurus rex might have weighed. (Interestingly, neither method involves pulling out an actual scale.)

Led by paleontologist Nicolás Campione of the University of New England, the researchers “examined an extensive database of dinosaur body mass estimates” from as far back as 1905, with weight estimates for individual specimens ranging anywhere from three tons to a whopping 18 tons. (For reference, the average sedan weighs a measly 1.5 tons.)

“Body size, in particular body mass, determines almost all aspects of an animal’s life, including their diet, reproduction and locomotion,” says Campione in a Royal Ontario Museum press release. “If we know that we have a good estimate of a dinosaur’s body mass, then we have a firm foundation from which to study and understand their life retrospectively.”

In an essay published by The Conversation, Campione explains that for years, paleontologists followed two rival approaches for tallying a dinosaur’s poundage. These methods were long thought to be at odds with each other, but Campione’s team found that both techniques are actually quite accurate.

Using limb circumference to find out an animal’s mass is already widely used across a variety of modern land animals, like primates, marsupials, and turtles, writes Campione. The same scaling method can be applied to dinosaurs. Researchers essentially measure the bones in living animals, such as the femur in an elephant’s leg, and compare that figure to dinosaur’s femur.

The second method involves calculating the volume of 3-D reconstructions of dinosaurs, which serve as approximations of what the creature would’ve looked like when it was still alive.

Occassionally, these methods have come to very different conclusions. For The Conversation, Campione presents a recent example of a discrepancy:

A [3-D] reconstruction of the gigantic titanosaur Dreadnoughtus, which lived roughly 80 million years ago in what is now Argentina, suggested a body mass between 27 and 38 tonnes. Yet its colossal legs suggest it could have supported even more weight: between 44 and 74 tonnes.

But after applying both methods repeatedly to an ample number of specimens in the database, it became clear that the case of the titanosaur was an outlier. “In fact, the two approaches are more complementary than antagonistic,” Campione says in a statement.

David Evans, a paleontologist at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto and senior author of the paper, says their conclusion illustrates the importance of using both methods in tandem—and highlights the importance of uncertainty, because “dinosaurs, like humans, did not come in one neat package,” according to the university statement.

“There will always be uncertainty around our understanding of long-extinct animals, and their weight is always going to be a source of it,” he says in a statement. “Our new study suggests we are getting better at weighing dinosaurs, and it paves the way for more realistic dinosaur body-mass estimation in the future.”

#News

0 notes