#Dallas Seitz

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Oliver Stone's Dallas

Director Oliver Stone put Dallas on the map as a desirable Hollywood film shoot location in the late 1980s and 1990s with Talk Radio, Platoon, Born on the Fourth of July, JFK, and Any Given Sunday. He’s also the subject of my book The Oliver Stone Experience and has been a friend for 15 years.

Texas Theatre honchos Jason Reimer and Barak Epstein invited Stone to attend a mini-retrospective earlier this month titled “4 Days in Dallas with Oliver Stone,” which screened his Dallas movies Talk Radio, Born on the Fourth of July, and JFK. Natural Born Killers was also part of the lineup; it wasn’t shot in Dallas, but celebrated its 30th anniversary this year. While he was in town, Stone fit in visits to Dealey Plaza, the Sixth Floor Museum, and the municipal archives beneath City Hall where records related to the Kennedy assassination are kept.

The centerpiece of the weekend was the Oct. 4 screening of 1991’s JFK at the same theater where accused assassin Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested, and where Stone re-created the arrest with Gary Oldman portraying Oswald. I sat with Stone in the back of the theater, a row behind one of the two seats Oswald occupied on November 22, 1963. When police onscreen spotted Oswald circa 1963 and demanded his surrender, they seemed to be addressing the assembled audience in 2024: a through-the-looking-glass moment.

After the screening, Stone spoke to me onstage about researching and making the movie as well as his personal experience of the assassination and its aftermath. He was 17, and spent the day “watching the coverage, like everybody else.” He didn’t begin seriously questioning the official version of historical events until after the 1974 kidnapping of Patty Hearst, when he read that some individuals involved in the crime had connections to the federal government. “Through the 1970s, I began to educate myself,” he said. Stone became fascinated by alternatives to the “lone gunman” and “magic bullet” theories in the late 1980s, when he was sent a nonfiction book as possible adaptation material: On the Trail of the Assassins by Jim Garrison, who, as the district attorney of New Orleans in 1960s, brought the only criminal trial related to the president’s murder.

Image Oliver Stone in front of the Texas Theatre marquee. Peter Salsbury “I really thought ‘this is a great thriller,’” Stone said of Garrison’s book. “I hadn’t done the research. I just believed what I was seeing [as I read] was…a potentially great movie.” While writing the script with Zachary Sklar, Stone melded Garrison’s book with Jim Marrs’ Crossfire: The Plot That Killed Kennedy, and added information he’d gleaned while visiting the film’s primary locations of Dallas, New Orleans, and Washington, D.C. He read the Warren Commission Report and books that questioned it. He talked to historians and former and current officials.

Stone had previously explained in my book, as well as in many interviews, that he made Garrison the main character of JFK because he presented the criminal case against alleged conspirators to kill Kennedy. Stone believed him to be a perfect vehicle to present additional information and other theories about what happened. He admitted that Garrison lost because he “had a weak case” against New Orleans businessman Clay Shaw (Tommy Lee Jones), but added that Shaw “was lying” to investigators and the jury about his connections to the New Orleans criminals and hustlers, anti-Castro Cubans, and members of right-wing paramilitary groups, all of whom loathed Kennedy.

Stone told Dallas Morning News writer Sarah Hepola that reading Garrison’s book while filming Born on the Fourth of July in Dallas may have sparked his decision to make JFK. “I never really made that connection [before], but I’m sure someone took me to see Dealey Plaza for the first time,” he said. “When you see it, you realize what a jewel box it is. How small. You don’t realize that from pictures. It’s a perfect ambush site.”

Various Hollywood and independent directors chose to shoot in Dallas before Stone came to town, resulting in films such as Logan’s Run, Robocop, the 1962 adaptation of the musical Stage Fair, and the horror film Phantom of the Paradise (which will receive a 50th anniversary screening this month at its primary filming location, the Majestic Theater). But it wasn’t until Stone chose Dallas as the location of his claustrophobic 1988 drama Talk Radio—based on star Eric Bogosian’s play, and filmed around the city and on soundstages at Las Colinas—that Dallas hosted a production that felt like possible Academy Awards material, helmed by a director who’d already won multiple Oscars (for Platoon, his 1986 film based on his experience as an infantryman in Vietnam, and his follow-up Wall Street, which got Michael Douglas a statuette as Best Actor).

Released at Christmas despite Stone’s objections (“it was so depressing!”) Talk Radio was a box office disappointment that got no awards traction. But his next project, 1989’s Born on the Fourth of July, about paraplegic war activist Ron Kovic, was a hit that was nominated for eight Oscars and won two (for directing and editing). Born was the movie Stone had wanted to make first in Dallas, mainly because nonunion crews would stretch its budget, but he had to wait eight months until his star Tom Cruise finished making Rain Main. He ended up doing Talk Radio as a time killer and—he said during a post-screening discussion—a way to try different directorial techniques and learn about the city.

For Born, the Elmwood neighborhood of Oak Cliff doubled for Kovic’s hometown of Massapequa, Long Island. Dallas was also briefly home to Syracuse University (faked at Southern Methodist University) and the Miami Convention Center (actually Dallas’ convention center with different signage and some trucked-in palm trees). JFK was the second Stone production to let Dallas be Dallas, and it brought a new level of real-world specificity to its action and dialogue, immersing itself deeply in Dallas’ identity. Where Talk Radio was electrifying for local viewers because of the abundance of recognizable locations and references (a gargoyle-ish rock-and-roller played by Michael Wincott gives a shout-out to “the girls at Valley View Mall!”) Stone’s immense, densely packed JFK—a combination courtroom thriller, detective story, and muckraking work of agitprop–went much further, making the layout of downtown and other parts of Dallas integral to the tale. It weaved in references to actual Texas politicians, institutions, and corporations—including “General Dynamics of Fort Worth, Texas,” cited by Donald Sutherland’s Mr. X as one cog of the military-industrial complex that stopped the United States from pulling out of Vietnam before combat troops could be introduced.

Three of the four screenings were sellouts, which seemed to surprise Stone, and the audiences lined up for good seats well in advance. At the JFK screening, Sutherland’s mammoth exposition dump and star Kevin Costner’s tearful final summation earned rounds of applause.

Stone attended a book signing before JFK, during which he inscribed copies of his memoir Chasing the Light, the JFK screenplay, and The Oliver Stone Experience as well as artifacts related to his filmography and its subjects. He signed a poster for his first directorial effort, the early-’70s horror film Seizure, and November 23, 1963 editions of Dallas Morning News and Dallas Times Herald.

The last time Stone spent serious time in Dallas was 1999, when Jerry Jones let him use the old Texas Stadium to shoot parts of his football epic Any Given Sunday. To my surprise, he said yes to a last-minute offer by city of Dallas archivist John Slate to peruse Dallas Police Department documents and photos from the days following the assassination, including crime scene photos of the book depository and the spot where Oswald shot officer J.D. Tippit in Oak Cliff, arrest sheets, fingerprints, and mugshots of Oswald and his killer Jack Ruby.

The only time when Stone could fit in a visit was a Saturday morning when the archives were officially closed, so Slate met us on a street corner near City Hall. He drove us into the parking garage and escorted us into the guts of the building, a sequence of events that would’ve fit right into the shadow world of JFK. Slate and assistant city archivist Kristi Nedderman had laid out some of the archives’ holdings on a long table. The two alternated showing Stone certain items with their own commentary and letting him sit quietly and flip through materials, which are kept in protective sleeves, at his own pace. (Copies can be viewed online here.)

Slate said the archives began in the late 1980s as a part of the city secretary’s office. The “original stash” of the JFK records was rediscovered in the police department “around 1989. We already had the bulk of the records, and although I don’t know all the details, right after [Stone] finished filming there or during the time he was filming there in 1990 and early 1991, the City Council got rather excited about whether they had done due diligence to take care of whatever was in city departments related to JFK,” Slate said. “A City Council resolution was passed in early ‘92 that all departments were directed to send JFK-related materials to the municipal archives.”

The JFK collection now contains more than 11,400 items that took two years to catalog, annotate and preserve, under the direction of Slate’s predecessor, Cindy Smolovick.

Slate told me he’d heard about the Texas Theatre screening series only a few days before it was scheduled to begin. He did not expect a yes from Stone on such short notice, but felt obligated to make the offer because “it’s fair to say that Oliver Stone was a direct influence on the development of the archives [in the 1990s] and the premiere collection in our archives, which is the JFK materials.”

-Matt Zoller Seitz, "Oliver Stone's Dallas," D magazine, Oct 10 2024

1 note

·

View note

Text

2024 olympics Switzerland roster

Athletics

Charles Devantay (Zurich)

William Reais (Chur)

Timothé Mumenthaler (Geneva)

Felix Svensson (Versoix)

Lionel Spitz (Adliswil)

Jonas Raess (Zurich)

Jason Joseph (Basel)

Julien Bonvin (Sierre)

Tadesse Abraham (Geneva)

Matthias Kyburz (Rheinfelden)

Ricky Petrucciani (Locarno)

Simon Ehammer (Stein)

Emma Van Camp (Bern)

Annina Fahr (Schaffhausen)

Catia Gubelmann (Zurich)

Lena Wernli (Zurich)

Julia Niederberger (Buochs)

Giulia Senn (Bern)

Géraldine Frey (Zurich)

Salomé Kora-Joseph (St. Gallen)

Mujinga Kambundji (Bern)

Ditaji Kambundji (Bern)

Léonie Pointet (Jongny)

Audrey Werro (Fribourg)

Rachel Pellaud (Biel/Bienne)

Valentina Rosamilia (Aargau)

Yasmin Giger (Romanshorn)

Fabienne Schlumpf (Wetzikon)

Helen Eticha (Geneva)

Sarah Atcho-Jaquier (Lausanne)

Angelica Moser (Andelfingen)

Pascale Stöcklin (Basel)

Annik Kälin (Zurich)

Badminton

Tobias Künzi (Würenlingen)

Jenjira Stadelmann (Bern)

Canoeing

Martin Dougoud (Geneva)

Alena Marx (Bern)

Climbing

Alexander Lehmann (Bern)

Cycling

Stefan Bissegger (Weinfelden)

Marc Hirschi (Ittigen)

Stefan Küng (Wil)

Alex Vogel (Frauenfeld)

Mathias Flückiger (Bern)

Nino Schurter (Tursnaus)

Cédric Butti (Thurgau)

Simon Marquart (Zurich)

Elise Chabbey (Geneva)

Noemi Rüegg (Schöfflisdorf)

Linda Zanetti (Lugano)

Elena Hartmann (Grisons)

Aline Seitz (Basel)

Michelle Andres (Baden)

Alessandra Keller (Ennetbürgen)

Sina Frei (Männedorf)

Nikita Ducarroz (Sonoma County, California)

Nadine Aeberhard (Bern)

Zoe Claessens (Echichens)

Equestrian

Robin Godel (Fribourg)

Felix Vogg (Waiblingen, Germany)

Steve Guerdat (Elgg)

Martin Fuchs (Zurich)

Edouard Schmitz (Wangen An Der Aare)

Pius Schwizer (Oensingen)

Andrina Suter (Schaffhausen)

Mélody Johner (Cheseaux-Sur-Lausanne)

Fencing

Alex Bayard (Sion)

Pauline Brunner (La Chaux-De-Fonds)

Golf

Joel Girrbach (Kreuzlingen)

Albane Valenzuela (Dallas, Texas)

Morgane Métraux (Lausanne)

Gymnastics

Luca Giubellini (Rebstein)

Matteo Giubellini (Rebstein)

Florian Langenegger (Bühler)

Noe Seifert (Sevelen)

Taha Serhani (Hutwill)

Lena Bickel (Ticino)

Judo

Nils Stump (Uster)

Daniel Eich (Fribourg)

Binta Ndiaye (Bern)

Pentathlon

Alexandre Dällenbach (Saint-Denis, France)

Anna Jurt (Bern)

Rowing

Scott Bärlocher (Würenlos)

Dominic-Remo Condrau (Zurich)

Maurin Lange (Bern)

Jan Plock (Zurich)

Patrick Brunner (Zurich)

Kai Schaetzle (Lucerne)

Joel Schurch (Schenkon)

Raphaël Ahumada (Lausanne)

Jan Schäuble (Bern)

Andrin Gulich (Zurich)

Roman Röösli (Neuenkirch)

Tim Roth (Zurich)

Célia Dupré (Plan-Les-Ouates)

Lisa Lötscher (Meggen)

Fabienne Schweizer (Lucerne)

Pascale Walker (Zurich)

Aurelia-Maxima Janzen (Bern)

Sailing

Elia Colombo (Bern)

Arno De Planta (Pully)

Yves Mermod (Zurich)

Sébastien Schneiter (Bern)

Elena Lengwiler (Hinwil)

Maud Jayet (Lausanne)

Maja Siegenthaler (Spiez)

Shooting

Jason Solari (Malveglia)

Christoph Dürr (Zurich)

Nina Christen (Stans)

Audrey Gogniat (Le Noirmont)

Chiara Leone (Frick)

Swimming

Tiago Behar (Lutry)

Antonio Djakovic (Frauenfeld)

Thierry Bollin (Bern)

Roman Mityukov (Geneva)

Noè Ponti (Locarno)

Jérémy Desplanches (Geneva)

Nils Leiss (Geneva)

Lisa Mamié (Zurich)

Tennis

Stan Wawrinka (Stans)

Viktorija Golubić (Zurich)

Triathlon

Adrien Briffod (Vevey)

Max Studer (Kestenholz)

Sylvain Fridelance (Vaud)

Julie Derron (Zurich)

Cathia Schär (Lavaux-Oron)

Volleyball

Tanja Hüberli (Thalwil)

Nina Brunner (Steinhausen)

Esmée Böbner (Hasle)

Zoé Vergé-Dépré (Berne, Germany)

#Sports#National Teams#Switzerland#Celebrities#Races#Boats#Animals#Germany#Fights#Golf#Texas#France#Tennis

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

[ad_1] A transformative residential undertaking is on the horizon in one in all Dallas’s fast-growing suburbs. Ross Perot Jr.’s Hillwood Communities has acquired 1,380 acres of ranchland close to downtown Celina, with plans to construct a 4,000-home group known as Ramble, the Dallas Morning Information reported. The event, situated on Preston Street, is predicted to open in 2025. It’s Hillwood’s fourth group in Celina, becoming a member of Bluewood, Lilyana and Glen Crossing. Building is ready to start later this yr. “Celina is scorching,” Hillwood president Fred Balda advised the outlet. “To have the ability to management 4,000 heaps on this market provides us a pleasant runway to do the issues we love to do with these huge grasp deliberate communities. We now have been engaged on this now for in all probability a yr or so.” The primary section of Ramble, comprising 700 heaps, has already been bought to 5 builders: American Legend Houses, Coventry Houses, Drees Customized Houses, Highland Houses and Perry Houses. The group will function a wide range of housing types, together with townhomes and single-family dwellings on half-acre heaps. Costs for single-family houses will begin within the $400,000 to $500,000 vary, Balda stated. The developer will reserve 18 acres for flats and 64 acres for business and retail area. Residents can have entry to a 4-mile greenbelt of parks, open areas and lakes, the outlet stated. Hillwood’s newest acquisition sheds mild on the approaching progress in Celina, the place the annual supply of two,500 houses is predicted to double over the following few years. Different large-scale tasks in Celina’s pipeline embrace Centurion American Improvement Group’s 3,200-acre master-planned group known as Legacy Hills, and Seitz Group’s 77-acre mixed-use improvement, which is slated for 750 residential items, a 110,000-square-foot luxurious health heart and a slew of family retailers and eating places. —Quinn Donoghue [ad_2] Supply hyperlink

0 notes

Photo

Accidental Sculpture #1, 2016

Dallas Seitz

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the archives: the first profile of Wes Anderson and Owen Wilson (1994)

Matt Zoller Seitz

The image at the top of this page is a scanned article from Dallas Observer, where I worked as a film critic in the early '90s. As some of you may know, I later wrote a book about Wes Anderson and his movies: The Wes Anderson Collection, which comes out October 8.

I wrote this article for a roundup of short films programmed in the 1994 USA Film Festival, then Dallas' only major festival. I wrote a bit about many of the shorts that played that year, but for a variety of reasons (including Anderson's unusual stylistic assurance, and the fact that the movie made Woody Allen-esque use of actual Dallas locations) "Bottle Rocket" jumped out at me. I had a feeling we hadn't heard the last of these guys.

"Bottle Rocket" was later expanded into a feature. It was Anderson's first credit as a director, the first screenwriting credit for him and his friend and collaborator Wilson (who would be nominated for a Best Original Screenplay Oscar for 2001's "The Royal Tenenbaums"), and the first professional acting credit for a lot of the film's cast members, including Owen's brothers Luke and Andrew and Anderson bit player Kumar Pallana, then the proprietor of the popular Dallas hangout spot Cosmic Cup (now Cosmic Cafe).

The USA Film Festival dug this clip out of their archives today and emailed it to me. What a blast from the past: I had tried and tried to get a physical copy of the piece for the book while putting it together, but it was only available as microfiche at the public library (poor visual quality), and I was informed that the newspaper didn't have ready access to back issues, so in the text of The Wes Anderson Collection it is described rather than seen. Anderson says it the first profile of either him or Owen Wilson, as well as the first bit of positive criticism he received as a professional filmmaker from a professional news outlet. Of course in this case the word "professional" is relative. Anderson was only a few years out of the University of Texas, where he and Wilson met and became friends in the late '80s, and the film, while handsomely made, was a couple of budgetary steps up from a student production. And I'd only been a paid journalist for three years.

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Aidan - Clifford Chapin / Isole - Justin Briner / Lowell - Dallas Reid / Drayce - Daman Mills / Runo - Josh Grelle / Seven - Keith Silverstein / Koloss - Patrick Seitz / Jian - Greg Chun

Clifford Chapin & Justin Briner as 'Aidan' & 'Isole' - I detect some Bakugou x Midoriya shipping here with those two picks. XD BUT! I actually think those are two great picks! Chapin is who comes to mind for Kai already, and I haven't considered where I'd rank Briner, but I can definitely see him working as Isole, given his cinnamon bun-y approach to Midoriya.

Dallas Reid as 'Lowell' - Y'know, now more than ever, I'm wondering who Reid would be a better fit for, because on one hand, I already have him as my headcanon voice of Aidan. But on the other, he COULD also be a really good fit for Lowell, playing up that aggression and general impatience and, well, dumbness. Soooo, food for thought, huh.

Daman Mills as 'Drayce' - Honestly, that's a really good pick! I'm still not 100% on who I even consider for Drayce. Part of me wants to say Jonah Scott, but I'm not sure, and Mills IS a good choice indeed!

Josh Grelle as 'Runo' - Just gonna go ahead and tag @twistedtummies2 for no reason whatsoever there. :P Honestly, I'm still not sure who I hear when I think of Runo. He's ALSO another character I feel like Dallas Reid would be perfect for, but after a certain someone shared "Devil Is A Part-Timer" with me in its entirety, I CAN see that being a good fit. Sadao is a freakin' boob as much as he is a goober, and when he plays cocky, he gets shot down REALLY fast and gets all pouty and pathetic. All perfect qualifiers for this stupid synth. XD

Keith Silverstein as 'Seven' - That's a great pick honestly! I have Silverstein in mind for someone else, but believe it or not, he was one of the first voices that originally came to mind when I thought of Seven.

Patrick Seitz as 'Koloss' - I'm not sure how I feel about Seitz as Koloss because he plays domineering and big really well...I mean, the guy IS a freakin' giant in real life. But I've never heard him play a gruff, low-brow character like Koloss before. He was Sloth from Brotherhood, but that was more hulking, dopey monster more than a street-level thug the way Koloss kind of is.

Greg Chun as 'Jian' - Incidentally, I've never watched Squid Games because if I need a reminder that capitalism is bad, I only have to look out the window. (:' Honestly, I think Chun might sound a little too young, which is ironic, I'll admit, seeing as how he's nine years older than my headcanon voice for Jian, but Chun's almost like Yuri Lowenthal, in that they're both guys in their fifties who still sound young. And a big part of Jian's voice, for me, is having a very goofy uncle vibe that can turn on a dime when he needs to get serious.

Still, these are some pretty interesting picks! Thanks for taking the time to share 'em! :)

4 notes

·

View notes

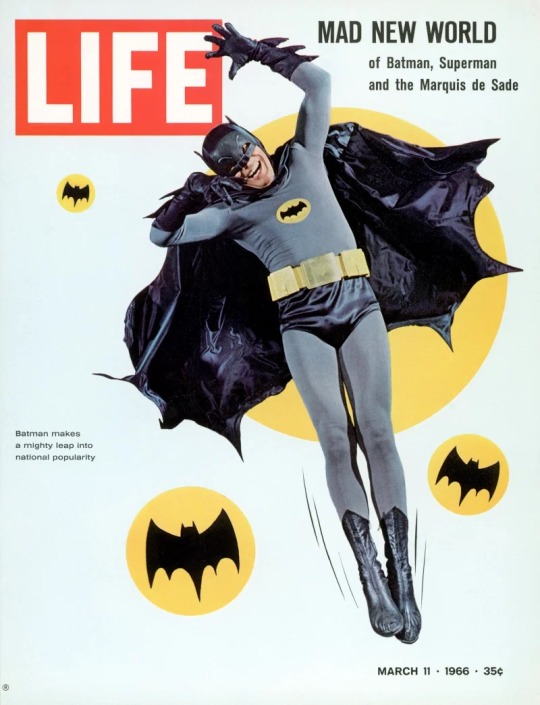

Link

Negli anni Sessanta, quando lo spettatore vedeva comparire a tutto schermo le onomatopee “Thwack!”, “Pow!”, “Crash!” sul proprio televisore, sapeva con certezza di stare guardando la serie tv di Batman. Lo show con protagonista Adam West, famoso per il suo stile camp e sopra le righe – una conseguenza dello spirito bizzarro delle storie a fumetti dell’epoca – è rimasto nella memoria collettiva come uno degli esempi più estremi di adattamento fumettistico.

Un Batman fuori di testa

Nel 1965, l’emittente televisiva ABC – che si spartiva il titolo di canale più visto insieme alle rivali CBS e NBC – stava perdendo posizioni rispetto alle concorrenti ed era alla ricerca di un programma di largo successo. Ricerche di mercato condotte da ABC avevano eletto tra i personaggi preferiti del pubblico Superman, Dick Tracy, Annie e Batman. Quando i diritti di Superman e Dick Tracy si rivelarono fuori dalla portata del canale, un dirigente, appassionato lettore di Batman fin da ragazzino, propose di adattare Batman, e così ABC approcciò la divisione televisiva dello studio 20th Century Fox e il produttore William Dozier. Dozier non aveva familiarità con il mondo del supereroe. Decise di documentarsi e lesse i fumetti, trovandoli «fuori di testa e molto infantili».

Dozier non aveva approfondito granché le sue letture, altrimenti avrebbe scoperto che in origine Batman era un vigilante pulp dai modi duri. Ma negli anni Cinquanta e Sessanta, le storie di Batman (e Superman) avevano preso una deriva particolarmente fantasiosa: Bruce Wayne combatteva spesso in scenari onirici – tra oggetti di scena giganti e mondi alieni – o contro cattivi assurdi (Bat-Mito, Calendar Man). Con l’aiuto dello sceneggiatore Lorenzo Semple Jr., futuro scrittore di film come Papillon, I tre giorni del Condor e Flash Gordon, pensò allora di assecondare quello stile, anzi, di esagerarlo. Gli adulti lo avrebbero trovato comico, i bambini immaginifico.

La produzione scelse gli attori in base alla loro capacità di affrontare con serietà anche il testo più scemo. Adam West era un attore televisivo sempre molto sobrio e determinato, ideale per quell’umorismo deadpan, dove la comicità sta nel contrasto che si crea quando una battuta è recitata con serietà estrema, a cui puntavano i produttori. In particolare, West li convinse con una pubblicità della Nesquik dove recitava nei panni di un simil James Bond. L’altra metà del Dinamico Duo, la spalla giovane ed esuberante Robin, prese vita grazie all’esordiente Burton Gervis, universitario ventunenne che praticava judo. Gervis cambiò il suo nome in Burt Ward per renderne più facile la pronuncia.

ll trucco era che gli attori avessero una recitazione quanto mai credibile. La situazione, le storie, i gadget, era tutto sopra le righe, non poteva esserlo anche la recitazione. Proprio la performance impassibile di West, integerrimo anche quando doveva ballare il “Batusi” e amorevolmente coscienzioso (anche nelle situazioni d’emergenza, pagava il parcheggio della Batmobile), rappresentò uno dei punti di forza dello show. «Non c’erano ombre o riferimenti al perché Batman facesse quel che faceva, nessun flashback su suoi genitori uccisi da un colpo di pistola in un vicolo sudicio» scrive Grant Morrison nel libro Supergods. «Il Batman di Adam West era Batman perché per lui aveva senso esserlo.»

Dozier chiese ad attori e attrici di sua conoscenza di interpretare le parti di contorno. Così, i ruoli dei cattivi andarono ad attori e comici di fama come Cesar Romero (che rifiutò di radersi i baffi, suo marchio di fabbrica, per vestire i panni del Joker, e i truccatori dovettero abbondare con il cerone), Burgess Meredith, Frank Gorshin, Vincent Price, Roddy McDowall, Milton Berlen, Joan Collins e Liberace.

Un’icona popolare

La serie colpiva per l’impianto visivo da pop art, con costumi e scenografia eccentriche e coloratissime – in un panorama televisivo ancora poco avvezzo al colore – e le onomatopee di colpi e pugni a tutto schermo durante i combattimenti. I cattivi erano presi dal fumetto, e quando non lo erano, gli sceneggiatori si lasciavano andare a creazioni bizzarre come Egghead o King Tut. Un elemento fu invece ripensato da zero: la Batmobile, che nel programma è una versione modificata della Lincoln Futura, una concept car (cioè un prototipo mai entrato in produzione) del 1955.

Quando, nell’autunno del 1965, andò in onda l’episodio pilota, le recensioni furono pessime, ma ormai ABC aveva già acquistato la serie e la mandò in onda ogni mercoledì e giovedì, spezzando una puntata in due episodi di mezz’ora con un cliffhanger nel mezzo. Inaspettatamente, forse complice il clima politico e culturale tutt’altro che rassicurante, Batman diventò l’esperienza escapista preferita dei telespettatori statunitensi. L’Uomo Pipistrello si tramutò in un’icona della cultura pop, finendo sulle copertine dei giornali e furoreggiando come beniamino del pubblico. Era la terza grande B degli anni Sessanta, dopo James Bond e i Beatles.

Fu messo in cantiere di tutta fretta perfino un film per il cinema, in cui Batman e Robin combattevano contro Joker, Pinguino, Catwoman e l’Enigmista. Della pellicola rimane famosa la scena in cui Batman non riesce a sbarazzarsi di una bomba che sta per esplodere, nonché il repellente per squali, l’arma più improbabile che l’eroe avrebbe mai potuto avere nel suo arsenale.

L’eco del successo arrivò presto anche nel nostro paese. Sul Corriere della Seradel 31 marzo 1966 Giuseppe Josca già registrò la portata fenomenale della serie, che gli spettatori italiani avrebbero visto a partire dall’autunno di quell’anno. «Batman è diventato di colpo uno dei personaggi più popolari d’America» scriveva Josca. «Quanto durerà? Qualcuno dice che siamo appena al principio.»

Il declino e la riscoperta della serie tv di Batman

Se da una parte la struttura molto rigida e prevedibile degli episodi rese iconico il programma – c’erano situazioni e scene ricorrenti, come quella in cui Batman e Robin si arrampicavano su un edificio e interagivano con una guest star che sbucava da una della finestre del palazzo – dall’altra consumò in fretta l’entusiasmo del pubblico e la ripetitività degli intrecci uccise la loro comicità intrinseca. Inoltre, in una sorta di rilancio obbligatorio, le trame si facevano sempre più visivamente folli, con grandi scenografie e marchingegni nuovi, e richiedevano budget alti.

Nel tentativo di tagliare i costi, la produzione prese una serie di scorciatoie: in una puntata, Batman affronta un gruppo di antagonisti invisibili e, per equilibrare la lotta, combatte al buio. La scena è uno schermo nero con solo i rumori dei pugni e le onomatopee in sovraimpressione.

Nella terza stagione, per tentare di risollevare gli ascolti, introdussero un terzo personaggio protagonista, Batgirl, interpretato da Yvonne Craig, ma nulla di tutto ciò riuscì a recuperare il pubblico perso. Batman chiuse alla fine della terza stagione.

West e Ward interpretarono i personaggi in alcuni film e cartoni per la televisione, tra cui un lungometraggio metanarrativo, Supereroi per caso: Le disavventure di Batman e Robin, in cui si ripercorre la storia produttiva del telefilm. Adam West morì nel 2017, a 88 anni. Due anni dopo, Ward indossò di nuovo i panni di Robin nel crossover televisivo Crisi sulle Terre infinite.

Nel frattempo però Batman era diventato un prodotto diverso. Gli spettatori che recuperarono la serie dopo la chiusura non ridevano più con il programma ma del programma, perché il mutamento dei tempi lo aveva fatto diventare ridicolo, pacchiano e dozzinale. Solo negli ultimi anni il pubblico è tornato ad apprezzare l’umorismo volontariamente camp della produzione. La serie diventò il mezzo di paragone per qualsiasi adattamento di materiale fumettistico, in positivo («volevamo proprio quel gusto») o in negativo («non lo faremo così esagerato»), ma nessuno ha mai più osato così tanto con il personaggio.

Nel libro TV (The Book), i critici Alan Sepinwall e Matt Zoller Seitz inserirono la serie nella lista delle migliori mai realizzate. Pur colpevole di «aver fornito ai giornalisti una serie di stereotipi su cui appoggiarsi ogni volta che trattavano la forma espressiva del fumetto», Batman era «una casa degli specchi che rivoltava le ansie del mondo reale e dava loro una voce buffa».

Nonostante la richiesta dei fan, Batman uscì sul mercato home video per la prima volta soltanto nel 2014, a causa di una serie di grovigli legali che aveva bloccato ogni iniziativa fino ad allora, tra cui la mancata intesa tra DC Comics, che deteneva i diritti dei personaggi, e 20th Century Fox Television, la casa di produzione della serie tv. E persino il fatto che molte delle comparsate degli attori che interpretano i cattivi non erano state contrattualizzati e, per poter distribuire i DVD, la produzione avrebbe dovuto contattare ogni attore per regolarizzare le loro apparizioni o tagliare le scene del tutto.

Nel 2013, DC Comics varò una serie a fumetti ambientata nel mondo della serie tv, Batman ’66, scritta da Jeff Parker e disegnata da vari autori, tra cui Mike Allred. La testata presentò anche un adattamento di una sceneggiatura scritta da Harlan Ellison per il programma ma mai prodotta, in cui esordiva il personaggio di Due Facce. La serie ebbe un buon seguito, tanto da generare alcuni spin-off.

C’è poi un piccolo aspetto tragico che intreccia la storia della serie tv di Batman con quella del fumetto. Per moltissimo tempo, l’unico autore associato alla creazione di Batman fuBob Kane, fumettista che ricorreva però all’uso di sceneggiatori e disegnatori non accreditati (i cosiddetti ghost writer e ghost artist). Uno di questi, Bill Finger, fu fondamentale nella creazione del personaggio e poi nella scritture di molte delle prime storie di Batman. Tuttavia, da vivo Finger non ricevette mai riconoscimenti pubblici per il suo contributo e morì, indigente, negli anni Settanta.

Finger fu riabilitato ufficialmente come co-creatore solo nel 2015. La storia della sua rocambolesca restaurazione è raccontata nel documentario del 2017 Batman & Bill, in cui si cita un episodio riguardante la serie tv. Bisognoso di lavoro, Finger riuscì a farsi ingaggiare per scrivere due puntate della serie insieme all’amico sceneggiatore Charles Sinclair. Sinclair ricorda che Finger gli chiese di poter comparire per primo nei titoli di testa degli episodi, perché per lui significava molto. Quei due episodi, in cui il supereroe si scontra con il Re degli Orologi, sono l’unica produzione di Batman accreditata a Finger.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vinland Saga dub cast headcanons

If Vinland Saga were to ever get a dub (which I highly doubt it will),I think this would be the cast. If I couldn’t figure out a decent voice actor, the character won’t be listed.

Xander Mobus-Thorfinn (alternate pick: Dallas Reid) Patrick Seitz-Thorkell (alternate pick: Jamieson Price) Keith Silverstein-Asgeir David Lodge-Askeladd

and now for Canute.

Zach Aguilar-Canute (alternate picks: Micah Solusod, Casey Mongillo, Justin Briner, Sean Chiplock, Aaron Dismuke, Khoi Dao)

As for why I picked said voice actors...I dunno, I picked based off of prior roles, especially in the case of my pick for Thorkell and Askeladd. To me, Patrick Seitz or Jamieson Price would be a perfect fit for a guy of Thorkell’s size, while I feel David Lodge could be a perfect Askeladd due to the character’s nature.

#vinland saga#thorfinn#thorfinn karlsefni#thorkell#canute#prince canute#King Canute#askeladd#Lucius Artorius Castus#asgeir

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 Minutes on Talk Radio

Barry Champlain, the main character of 1988’s “Talk Radio,” is a Dallas-based, left-wing “shock jock” whose rants are little arias of outrage. Sometimes a caller who’s obviously suffering will bring out his humanity for a moment, but his default mode is scorched-earth combativeness. It would be misleading to call him a “provocateur” because the word is elegant and Barry is not, and because Barry doesn’t provoke; he attacks, and continues attacking even after his adversary has folded. Sometimes when a caller tries to take a piece out of him, Barry will not just verbally beat them down but cut off their audio feed without telling the audience he’s done so and then rip into them for another few seconds, which makes it seem as if the person that used to be on the other end of the phone line was stunned into silence by his words. He’s a virtuoso of rage, and that’s more than enough to make him a local star and get a national radio syndicate interested in picking up the show.

But Barry can’t turn the rage off. He directs it at his coworkers, his supervisors, his romantic partners (currently his producer Laura, played by Leslie Hope) and himself. I know a lot of people who gave this movie a try but had to turn it off because Barry was too much to take. I get it. Even when you agree with him, he’s miserable and angry. Exciting, too, but not in a healthy way.

Star Eric Bogosian created Barry Champlain for the stage in a same-named play that debuted on Broadway in the late 1980s, where it was seen by film producer Ed Pressman. Pressman called one of his regular collaborators, director Oliver Stone, who’d had a three-film winning streak with “Salvador,” “Platoon” and “Wall Street” but had recently been told that his next movie, the antiwar drama “Born on the Fourth of July,” would be delayed eight months while his star Tom Cruise finished making “Rain Man” with Dustin Hoffman. Stone filled his schedule gap with “Talk Radio” and combined Bogosan’s play with elements from the nonfiction book “Talked to Death,” about the murder of Alan Berg, a Denver-based, Jewish talk radio host with progressive politics, by a member of a neo-Nazi terrorist group.

Everything about the movie feels unstable and potentially explosive, so much so that when Barry launches into his most paranoid and unhinged monologue yet, cursing the world itself and attacking his listeners for listening to him, and the main set seems to rotate slowly around Barry, it’s as if somebody is winding up a timer attached to a bomb. Although Stone didn’t create the character, Barry is a consummate Oliver Stone hero, a creature of nearly mythological force, shouting prophecies and curses at a burning world. When a right-wing listener sends him a dead rat wrapped in a Nazi flag, Barry’s reaction is a mix of fear, disgust, and wonderment, as if he’s realized that if he’s pissing off these kinds of people this much, he must be great at his job.

This aspect of Barry’s story is why I became obsessed with “Talk Radio” 36 years ago after seeing it in a Dallas theater. He was an antihero in the tradition of so many ‘70s film protagonists: somebody you weren’t supposed to like, but to find interesting, even when he was at his most loathsome.

The parts of the movie that I didn’t like and that frankly didn’t think was necessary or interesting were the flashbacks to Barry’s rise to success and the corresponding disintegration of his relationship with his wife Ellen (Ellen Greene), which are tied into a subplot about Barry swallowing his pride over destroying the relationship and asking Ellen to come to Dallas and counsel him the weekend before the show is supposed to go national. Ellen’s ease with diving into the old dynamic (even after Laura answers the phone when Ellen calls, and Barry lies and claims she’s his secretary) didn’t seem plausible to me back in 1988. When Ellen called into the show in the present-day part of the story, throwing a life preserver to a man drowning in a sea of his own bile, I think I might’ve rolled my eyes, because it seemed like more grownup version of a male fantasy of a woman getting turned on by a man’s hatefulness. Barry used and abused her at every stage. I never saw anything I recognized as real love flowing from Barry to Ellen, only from Ellen to Barry.

Did you already figure out that I was 19 when I saw “Talk Radio” for the first time and had yet to begin my first long relationship with a woman? Well, that’s why I didn’t get it. Angry young men are drawn to films like this, perhaps more so than other types of viewers, because they center the antihero and put you inside his head at least part of the time, and while they aren’t forcing you to identify with them, they make it pretty easy. But this movie is more subtle, I think, which probably seems like a strange assertion considering how unrelentingly intense it is.

Stone gets criticized for being less interested in female characters than male ones, and having a misogynistic streak. Setting aside the particulars of why I think this is complicated (i.e. not entirely fair or unfair) I don’t think it applies to “Talk Radio” at all. It’s observing a dynamic that’s real. There are a lot of guys like Barry who take their partners for granted or just plain use them (women can do this, too) and there are absolutely a lot of female partners of dynamic/abrasive men who spend their lives lugging a fire extinguisher under one arm in case their man flips out and starts trying to burn things down. (Sometimes you see a relationship like this where the typical gender roles are flipped. Jessica Lange and Tommy Lee Jones in “Blue Sky,” for instance. Or my mother and stepfather.)

The Barry-Ellen relationship rings progressively more true to me the older I get and the more experience I have as a significant other—and, frankly, as a human being who has spent a lot of time observing other relationships and has gotten to the point where I can spot codependency from the other side of a room before a couple has even been introduced to me. Barry and Ellen are codependent in a complicated, real way. That’s why they don’t struggle before slipping into old patterns.

At one point, Ellen calls into Barry’s show and lies down on a black table in an unused studio as if she’s waiting for a lover to walk in and get busy. It’s theatrical–not a complaint, just an observation–and I wonder if that’s why I thought it was reductive or silly on first viewing. It’s closer to a kind of expressionism or symbolic choreography, like the kind you see in the staging of plays or dance numbers, where people pose in a way that embodies an idea or metaphor.

This is a brilliant movie, one that not only gets better and richer the more often I revisit it, but that’s filled with truths about the human condition, not just the media or America or sociology or history. You can see yourself represented in it, whether it’s as Barry, Ellen, another character at the radio station, or one of Barry’s listeners, who love him even when they hate him, and the reverse, and spend way too much time wondering if he’ll save or destroy himself, or if that’s out of their hands, and Barry’s.

-Matt Zoller Seitz, "30 Minutes On: Talk Radio," RogerEbert.com, October 11, 2024

1 note

·

View note

Link

From a child striving to perfect her accent to a professor and entrepreneur who has made a career from the language and land she loves, Dallas native Elizabeth New Seitz is living la belle vie in the countryside near Paris

1 note

·

View note

Text

[ad_1] A transformative residential undertaking is on the horizon in one in all Dallas’s fast-growing suburbs. Ross Perot Jr.’s Hillwood Communities has acquired 1,380 acres of ranchland close to downtown Celina, with plans to construct a 4,000-home group known as Ramble, the Dallas Morning Information reported. The event, situated on Preston Street, is predicted to open in 2025. It’s Hillwood’s fourth group in Celina, becoming a member of Bluewood, Lilyana and Glen Crossing. Building is ready to start later this yr. “Celina is scorching,” Hillwood president Fred Balda advised the outlet. “To have the ability to management 4,000 heaps on this market provides us a pleasant runway to do the issues we love to do with these huge grasp deliberate communities. We now have been engaged on this now for in all probability a yr or so.” The primary section of Ramble, comprising 700 heaps, has already been bought to 5 builders: American Legend Houses, Coventry Houses, Drees Customized Houses, Highland Houses and Perry Houses. The group will function a wide range of housing types, together with townhomes and single-family dwellings on half-acre heaps. Costs for single-family houses will begin within the $400,000 to $500,000 vary, Balda stated. The developer will reserve 18 acres for flats and 64 acres for business and retail area. Residents can have entry to a 4-mile greenbelt of parks, open areas and lakes, the outlet stated. Hillwood’s newest acquisition sheds mild on the approaching progress in Celina, the place the annual supply of two,500 houses is predicted to double over the following few years. Different large-scale tasks in Celina’s pipeline embrace Centurion American Improvement Group’s 3,200-acre master-planned group known as Legacy Hills, and Seitz Group’s 77-acre mixed-use improvement, which is slated for 750 residential items, a 110,000-square-foot luxurious health heart and a slew of family retailers and eating places. —Quinn Donoghue [ad_2] Supply hyperlink

0 notes

Text

Slouching Toward Hollywood - Dallas Observer; September 7, 1995.

By Matt Zoller Seitz Can four young Dallas filmmakers sell their dream-and still keep their souls? Matt Zoller Seitz follows the trail of Bottle Rocket. Jimmy Caaaaaaan! Luke Wilson was thrilled. It was November 1994, and the star of The Godfather, Thief, and Misery, icon to two generations of aspiring young actors and a walking template of life's rougher passages, was jogging beside him on train tracks near a downtown Dallas factory. A film crew was gathered nearby. They were shooting a scene for the new movie Bottle Rocket. In it, Luke Wilson played a younger thief taken under the wing of an older heist expert--Mr. Henry--played by Caan. The guy was a living legend. He'd been making films for three decades. He'd been directed by Howard Hawks and Francis Coppola. He'd acted opposite everybody from John Wayne to Al Pacino to Kathy Bates. Hollywood had come calling in Dallas. Courtesy of Columbia Pictures, an arm of Sony, Luke and a small group of fellow Dallasites would get to make a feature-length, $6 million version of their short film "Bottle Rocket." Minimogul James L. Brooks--who gave the world "The Mary Tyler Moore Show," " Taxi," and the Oscar-winning Terms of Endearment--was mentoring the project, protecting the young Texans from studio interference. The feature would employ some of the same people who'd worked on the short-- including Owen Wilson, Luke's brother, who cowrote and costarred in it; his friend Wes Anderson, the director; his other brother Andrew, who was both coproducing and acting in the picture; and actor Robert Musgrave, a dear friend.

Like his friends and brothers, Luke was under considerable pressure. As the movie's hero, he had to be strong, sensitive, righteous, and quiet, but not boring. That's tough when you're surrounded by supporting players in more colorful roles. He also had to act opposite James Caan in the actor's first screen appearance since going through a stint in drug and alcohol rehab. Most intimidating of all, Luke Wilson had acted on film only once before--in the low-budget short. Fortunately, Luke and Caan were working well together. Then the great James Caan blew a line. "Ahhh," he winced. "Cut it." "Cut what, Mr. Henry?" Luke shot back, still jogging, not missing a beat. Caan did a double-take. "I said cut, kid. I blew it! Let's take it over." "Do what over, Mr. Henry?" Luke stammered. When the crew members realized what Luke was thinking, they had to laugh. On a low-budget short, if you screw up, you keep going--because film is expensive and you don't have much of it. He was instinctively ad-libbing, trying to save the take. When Caan figured it out, he grinned. He walked over to Luke. Their noses were inches apart. "Fuckin' moron!" Caan chuckled, shaking his head. "Fuckin' MORON!" he repeated, grinning even wider. Then he head-butted Luke. As Luke stumbled back in surprise, the crew cracked up--because in Jimmy Caan's world, a head-butt is a sign of deep affection. "I love this kid!" Caan bellowed to Owen. "I mean it! I love your brother. He's the greatest! You could throw a plate of shit in his face and he'd ad lib!" Everybody laughed. Then it was back to work. In the time it took for everybody to have their laugh, the studio's invisible money meter had ticked off enough loot to pay for the humble short film Bottle Rocket was based on. Director Wes Anderson often thought about this predicament--about having so much money and so many people at his disposal, and being so young and inexperienced. Looking back on the shoot last week, from the vantage point of six long months spent in a Los Angeles editing suite---obsessively cutting and re- cutting Bottle Rocket to please James L. Brooks, Columbia Pictures, and his own perfectionist notions--the rookie director still finds the experience a bit surreal. "We had a couple of moments where we'd get together and look around and think about how weird it all seemed," he says. "We'd look at all the huge trucks and all the lights and equipment, the incredible number of tables and chairs set up for the cast and crew to eat, and all these experienced people all around us, working on our movie, and we'd go, 'Jesus Christ! Can you even believe this?' It almost felt like a con." "It was a scary feeling," says Owen Wilson. "I'd think, 'Man, are we really gonna do this? Does something like this really come from when me and Wes used to sit around during college making up funny stuff? Is this what it was all leading up to?'" Access to more film stock wasn't the only difference the Dallas wunderkinds encountered during the three years it took to bring Bottle Rocket to fruition. On every level, the experience illustrated the difference between independent and Hollywood filmmaking. Independent filmmaking is a gut-wrenching crap shoot. Every now and then, a film hits; most of the time, it doesn't. According to respected New York- based independent producer John Pierson, whose finds include Spike Lee, Steven Soderbergh, and Jim Jarmusch, hundreds of features were produced independently last year in the United States alone. A handful became bona fide mainstream successes. Perhaps two dozen more went on to brief theatrical runs in major cities. A few dozen others played at film festivals and then went directly to video without passing "Go." The rest disappeared into the ether. But even if an indie movie fails to break through to the mainstream, its makers can still carry their heads high, for one simple reason: they kept their freedom. If you are an independent filmmaker, and you decide to play offbeat games with characters, dialogue, or narrative, or indulge in a style of drama or

humor most viewers might not get, nobody at the home office can tell you "No"--because the home office is you. Hollywood studio filmmaking rarely affords such freedom. Because millions of corporate dollars are at stake, bean counters are forever peeking over your shoulder, second-guessing everything you do, urging you to avoid being strange or provocative and aim for as broad an audience as possible. Not even powerful filmmakers have absolute freedom; even Oliver Stone has to kiss somebody's ass. Every filmmaker dreams of a situation that combines the best of both worlds- -a situation that will allow him or her to use studio money to make a quirky, personal film. Some directors toil for decades and never once make a movie under such ideal conditions. But every now and then, the impossible occurs. The stars line up just right. And a bunch of ambitious young greenhorns stumbles into Eden. That's what happened with Bottle Rocket. The project started in 1991 as a black-and-white 16mm short film about a bunch of bored rich kids who become thieves. Owen Wilson and Wes Anderson conceived it when they were living together in Austin. They had met the previous year in a University of Texas playwriting class full of talkative people. They didn't speak the entire semester. They found the class dull, and most of their classmates duller. Wes sat in one remote corner of the room, rarely participating. Owen sat opposite him, usually reading The New York Times. At the beginning of the next semester, Wes saw Owen standing in a hallway. For reasons he can't explain, Wes walked over to his fellow mute and asked him what creative writing courses he ought to take. "I talked to him like we'd been best friends," he says. "It was kind of weird, but it felt right." They hit it off, meeting frequently to discuss their favorite authors and filmmakers, their love of Steve McQueen and Robert Altman and Sam Peckinpah and Martin Scorsese, of wide-screen Westerns from the 1960s and anti- establishment melodramas from the '70s. They sat up late at night spinning movie ideas, cracking each other up with off-center observations and strange stories. And they dreamed about what they'd like to do with their lives. They had many things in common. Both were intense, somewhat solitary undergraduates with hifalutin' majors (Wilson's was creative writing, while Anderson's was philosophy). Both were middle children raised in well-heeled, artistically inclined families who sent their kids to private schools. They eventually moved together into a small Austin duplex owned by a grandiloquent German landlord who had come to America via Colombia. What followed was a strange period that kick-started their screenwriting. The students had been feuding with their landlord for months over some old window cranks that had got stuck, leaving some windows perpetually half-open, ensuring the place was freezing in winter, sweltering during the summer, and a tempting target to burglars. Wes and Owen refused to pay rent until the landlord fixed them. He refused to fix the cranks until they paid their rent. Finally, the students took drastic action: they busted into their own apartment, then called the cops to report a break-in, taking care to explain that this horrible event wouldn't have happened if their landlord had fixed the damned window cranks. The landlord arrived, peered about the crime scene suspiciously, and announced, "This looks like an inside job." The cops shrugged, told the squabblers to work out their own dispute, and split. More months passed without resolution. The landlord arrived one morning to seize the students' belongings until they paid their rent. Wes got into a loud, violent, frenzied struggle with him over a vintage 8mm camera. The altercation resulted in another visit from the cops, who again cautioned the warring factions to quit acting like idiots, and work out their differences. But Owen and Wes were angry and scared; they fled to a friend's apartment that night without giving notice. The landlord hired a private detective, who

promptly tracked them down. Chastened, Wes and Owen apologized, explaining they didn't mean to skip out on their rent--they'd simply freaked out. To get back on the landlord's good side, Wes made a video documentary of the old German telling stories about his life. It was capped by a painfully emotional monologue. In it, the landlord told how he'd seized a pet python from a delinquent tenant who'd skipped town. The landlord kept the python in his apartment for a while, trying to decide what to do with it. To his astonishment, he grew to love it. He decided to keep it. But he soon discovered the giant snake had a digestive illness. It would not eat. The landlord tried everything to get the snake to eat, including force-feeding it. Nothing worked. The python grew weaker and sicker. It stopped moving. And one day, it simply died in his arms. As the landlord finished the story, he was crying. The death of that snake broke his heart. For the privilege of telling his story on video, the landlord paid Wes $600. "That taught me that you always gotta keep your eye peeled," Wes said. "You never know where the next strange, colorful character is coming from." A few months later, the roommates wrote a comedy script titled "Bottle Rocket." It was, Wes says, a kind of spiritual autobiography of that crazy time in their lives, capturing what it felt like to be young, naive, and stubborn, and determined to live in the moment. The plot is simple: a bored young rich kid named Anthony falls in with another bored young rich kid, a live-wire petty crook named Dignan. They break into houses together--including Anthony's mother's house. Deciding that the real money is in armed robbery, they acquire a charming but panicky wheel man named Hanson; together, the trio becomes a dedicated but hapless gang of thieves. A botched bookstore heist sends them on the run, but they soon return to the city. They are taken in by a dapper and mysterious older thief named Mr. Henry. Mr. Henry introduces the boys to his colorful crew, wows them with glitzy, Rat Pack-style parties and anecdotes about his exploits, and promises them a life of wealth and danger. He is a raconteur and philosopher who makes pronouncements like, "The world needs dreamers--to ease the pain of consciousness." He invites his young charges to take part in the elaborately planned robbery of a cold storage factory. The boys are in way over their heads but don't yet know it. As TV Guide would say, complications ensue. But the screenplay's strengths did not lie in its razor-thin plot. What made it special was its droll sense of humor and peculiar mood--warm, wistful, childlike, enchanted. Anthony, Dignan, and Hanson inhabit a universe Wes Anderson says is located "about five degrees removed from reality." There are few adults around, and fewer adult consequences; the story's world is as huge and sketchy and eerily quiet as the world of Charles Schulz's "Peanuts," a comic strip Wes and Owen loved reading when they were kids. The petty crooks' criminal activities rarely draw police attention and never draw blood; in fact, their misadventures have no palpable effect on anyone except themselves. They rob houses and bookstores for the same reason Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid robbed trains--to express their loyalty and affection for each other. Anthony, Dignan, and Hanson coast through life on sweet sensation, hoping to find in action the identities they lack in repose. Owen Wilson knew some people who could help. His family had been friendly with L.M. "Kit" Carson, a maverick independent writer-director who wrote and starred in the late-'60s cult favorite David Holzman's Diary, and scripted the 1983 remake of Breathless and the 1984 Wim Wenders-Sam Shepard art house favorite Paris, Texas. Carson and his wife, producer Cynthia Hargrave, lived in Dallas. "I'd first met Owen and his brothers at the Wilson house," Carson recalls. " They were movie maniacs. Their father had asked me over for dinner for the express purpose of talking them out of a career in movies. I figured out

pretty quick that there was no way anybody could talk them out of it." So instead, Carson invited the Wilsons to accompany him and Hargrave to the 1992 Sundance Film Festival. The trip energized the young would-be moviemakers. Over the next few months, they planned out the shooting of " Bottle Rocket." Luke Wilson would play the soulful, reticent Anthony. Owen, with his wild head of maize-colored hair and his charmingly crooked smile, would play the mischievous Dignan. Owen and Luke's older brother, Andrew, who had experience producing corporate videos, would produce the movie. Wes Anderson had worked under Andrew Wilson on his producing job; during that time, he'd met film industry professionals willing to donate their time and talent to an interesting shoestring project. The group courted investors, then kicked in their own money. They borrowed most of the necessary equipment. For film, they used 16mm black-and-white stock Andrew had been accumulating in a refrigerator over the past couple of years. Every piece fit. So in May 1992, the filmmakers shot the first eight minutes of "Bottle Rocket" at various Dallas locations, including the Greenway Parks homes and the storefronts of Deep Ellum. A few weeks later, they showed the results to Carson and Hargrave. "It was basically a first act," Carson says. "As a feature script, structurally, it had some problems." But Carson loved its uncensored, immediate quality. It was an innocent film made by innocent sensibilities. "Reading it for the first time was like reading The Catcher in the Rye as written by Holden Caulfield," he says. Carson and Hargrave told the filmmakers to shoot a few more scenes, edit it down to a compact short, and accompany them on their yearly trip to Sundance, which was coming up in January, 1993. They hoped they would meet someone willing to bankroll a feature version. Sometime in the late summer or early fall of 1992, Wes and Owen had to shoot the next few scenes from "Bottle Rocket"--the scenes introducing Hanson, the crew's lovably flaky wheel man. The knew just the guy. He was a 28-year-old blues guitarist, a transplanted West Virginian with brown hair, hound dog eyes, and a drawl thicker than molasses. His name was Robert Musgrave. His friends called him Bob. Bob had known the Wilsons for about a year. He met Owen at the Stoneleigh P. , shot pool with him, and lost $40. He cajoled Owen into jump-starting the battery on his car, then invited him to Blue Cat Blues to watch him sit in with the band that night. They liked each other immediately. Later, Owen introduced Bob to the others, who liked him right off. They auditioned him for the part of Hanson, then cast him. The character had originally been conceived as a much larger, tougher, harder-edged character, but the filmmakers eventually ended up tailoring the role to suit the actor playing him. They even changed the character's name to Bob. Bob's friendship with Wes and the Wilsons meant a lot to him. He was at a crossroads in his life. He was always a creative guy, but he hadn't had much luck building a career doing creative things. He'd tried stand-up comedy and sketch writing, but neither panned out. He'd built a promising career as a Dallas blues guitarist in the 1980s, even touring. But he was rootless and confused, unsure who he was or where his life was headed. Then he found himself doing cocaine. Lots of it. "Most of my money was going straight up my nose," he says. "I ended up screwing myself. That was a four- or five-month period in my life, but it took me a year to dig myself out from under the wreckage." With emotional support from friends and family, Bob went through rehab, got clean, and settled down into a considerably less chaotic life. When Wes Anderson and the Wilsons arrived, befriended him, and got him involved with " Bottle Rocket," Bob finally figured out exactly who he was. He was an actor. "I didn't know if the things I was trying to do in the short were gonna come off for sure," he says. "But I had good people behind me. I always felt like Wes was

picking up on the things I was trying to do. I always trusted him to hone it at the right places." The result was an indelible character; if Dignan was the brains of the crew and Anthony was the soul, Bob was the heart. And the actor playing him inhabited Bob's loyal, drolly funny, hapless psyche with such unfussy confidence that everything he said and did was hilarious. And his baleful eyes were so expressive that what he didn't say and do was even funnier. No matter what path he eventually takes as an actor, Bob wants to work with Wes and Owen every chance he gets. By January of 1993, the short film "Bottle Rocket" was ready for Sundance. It ran a compact 13 minutes. Every lyrical image and comic exchange was timed to exquisite perfection. Best of all, it was scored with Wes and Owen's ideal music--the music the late jazz composer Vince Guaraldi had provided for the beloved 1965 animated TV special "A Charlie Brown Christmas." The familiar score fit into the narrative like a missing puzzle piece, coaxing a striking mix of moods from Anderson's images. Wes decided that whether "Bottle Rocket" got made as a poverty-row indie feature or a big-budget Hollywood project, the Charlie Brown music had to be a part of it. "Bottle Rocket" got a good response at Sundance, but no solid offers from money men. So Carson and Hargrave embarked on the next leg of their plan--sending the feature-length script and a dub of the film to a couple of established producer pals in Los Angeles, Barbara Boyle, and Michael Taylor. Boyle and Taylor loved "Bottle Rocket" and passed it on to their friend, legendary producer Polly Platt, ex-wife of failed '70s genius Peter Bogdanovich. Platt, who had been in semiretirement for years, produced Bogdanovich's early, acclaimed films, including The Last Picture Show and Paper Moon. She had a keen eye for identifying and befriending young talent; in certain circles, it was rumored that what critics and audiences enjoyed in Bogdanovich's first few films--their simplicity and emotional directness-- could actually be credited to Platt. Platt loved "Bottle Rocket." Reading it conjured a nostalgic excitement she hadn't felt in a long time. Everything about it felt right: the storyline, the tone, the humor, the unknown filmmakers and actors attached to it--and especially the script's Texas roots. She even told Premiere magazine she thought "Bottle Rocket" was another Last Picture Show. In March 1993, Platt visited the set of James L. Brooks' latest movie as a writer-director and showed him "Bottle Rocket" over lunch. "Jim sat there and watched," Platt said, "and when it was over, he was quiet for a minute. Then he looked up at me and said, 'We have to make a deal with these guys.'" On May 1st, 1993--Wes Anderson's 24th birthday--Brooks and Platt came to Dallas. They made a deal: Platt would produce Bottle Rocket, overseeing the day-to- day minutiae of the shoot. Brooks would executive-produce the movie, helping them hone their screenplay, assemble a cast and crew, and run interference between them and Columbia Pictures. Brooks hoped the studio would kick in a $4-$6 million budget. The money was pocket change in Hollywood terms. But by the standards of guys trained to keep rolling when somebody flubbed a line, it sounded like a king's ransom. Then came the amazing part: Brooks and Platt wanted most of the major players involved in the short to work on the feature. Wes would direct, and cowrite with his old buddy Owen Wilson, who would play Dignan. Luke Wilson would play Anthony. Bob would play Bob, of course. Andrew Wilson would get an associate producer's credit, and would also play Bob's pumped-up, buzz-cut older brother, a post-adolescent bully who makes the meek wheel man's life a living hell. They would cast a big-name actor as Mr. Henry--an old pro with grace and charisma and high style. They'd hire a bunch of first-rate professionals to design, shoot, edit, and score the picture. Wes would be given a budget of several hundred thousand dollars just to buy the rights to his favorite pop

songs for the soundtrack. And yes, the boys could film Bottle Rocket in their hometown; Brooks wouldn't want it any other way. It was a miracle. James L. Brooks wanted to make their dreams come true. But first, Brooks told them, they had to make a few changes in the script. What was needed, he explained, was more warmth, more human interest, and more explication. The characters in a low-budget independent film could be oddball ciphers, but the characters in a Hollywood feature had to be oddball people--otherwise the average moviegoer wouldn't get their jokes, and wouldn't care what happened to them. Following a staged reading, Brooks suggested very specific changes. The first entailed reworking a key subplot--a sweet affair between Anthony and a beautiful Cuban housekeeper that blossoms after a botched heist, when the crew is holed up at a tiny motel in the country. Brooks wanted the romance beefed up, presumably so audiences that didn't get the humor would at least have a love story to latch onto. The next order of business was for Wes and Owen to create clearly defined backgrounds for Dignan, Bob, and Anthony--anecdotes clearly explaining what they want from life and why they are friends. Anthony, for example, now had a kid sister on whom he doted. It was hoped this would elicit audience sympathy. On one hand, the filmmakers figured Brooks knew what he was talking about. His tube track record, which stretched from "Mary Tyler Moore" and "The Bob Newhart Show" up through "The Simpsons," proved he understood how to make smart entertainment for a wide audience. His work as a writer-director--Terms of Endearment and Broadcast News--garnered enough Oscar nominations to anchor a zeppelin, and made money, too. But the filmmakers harbored some doubts. To them, what made Bottle Rocket special was its air of innocent mystery. Brooks was asking them to trade some of that mystery for warmth and accessibility. He was asking them to transform an art-house film into a crowd-pleaser with art-house qualities. During the last half of 1993, through the spring of 1994, Wes and Owen rewrote and rewrote and rewrote their screenplay. Digressions were whittled down or excised. The love story was expanded, and the nationality of the motel housekeeper, Inez, was changed to Mexican because Lumi Cavazos, the delicately beautiful star of Like Water for Chocolate, had been cast for the part. Bottle Rocket had been tentatively set to film in Dallas in spring 1994. But Brooks had run into trouble with his latest movie as writer-director, I'll Do Anything. Produced for somewhere around $40 million, the picture was a musical about the personal frustrations and career conundrums of a group of film industry professionals. For reasons understood only by Brooks himself, it had been cast with people who could not sing or dance, including Nick Nolte, Julie Kavner, Natasha Richardson, and Albert Brooks. Following disastrous previews, the director was faced with an ugly predicament: he had to cut out all the expensive musical numbers he had spent so many months filming, and turn the movie into a straightforward comedy. Meanwhile, Polly Platt and assorted studio executives busied themselves with preproduction work on Bottle Rocket--assembling a cast and crew. Brooks pitched in as often as he could--quite often, considering the career nightmare that had unexpectedly entangled him. The process was slow, but everything was falling into place. Only one obvious piece was missing: Mr. Henry. It was a small part, but crucial. They had to find just the right guy. The great James Caan expressed interest. He set up a meeting to talk about the movie and the part with Brooks, Wes, and Owen. "He was dressed like a big kid," Owen remembers: an oversized surf T-shirt, faded jeans, and cowboy boots. "When he came in the office, everybody was trying to put him at ease and make him feel comfortable. It turned out the thing he felt most comfortable talking about was karate and kicking people's asses." Caan had been studying martial arts for some time with a

smallish middle- aged Asian man named Tak, who accompanies Caan all over the country to film shoots. Tak is a martial-arts expert who acted as technical advisor on a number of chopsocky movies; he carried around a wallet full of pictures of himself posed beside various second-rung action celebrities, including Christopher Lambert. He was Caan's physical trainer, spiritual advisor, and close personal friend. "Jimmy calls Tak his master," Wes explains. Caan decided to strut his stuff. "Some of the moves Tak taught Jimmy were pretty amazing," Owen says. "The rest seemed kind of strange. I wasn't sure why he was so proud of them." First Caan demonstrated one of the amazing ones--something he called a " submission hold." He grasped one of Owen's arms, then jerked it in an odd direction. To everyone's shock, Owen's arm popped right out of its socket. " Everybody freaked out," Owen says. "Then my shoulder popped right back in, and I told everybody, 'I'm okay! It's all right! I'm okay, see?'" Then Caan demonstrated a technique he claimed would immobilize any opponent with just one touch. He stood before Owen and poked him in the chest with one knobby index finger. "It kind of hurt, I guess," Owen says. "But I wanted Jimmy to feel good, so I pretended it really, really hurt." "Ow! That hurt!" Owen cried. Then, perhaps hoping to deflect Caan's attention, he said, "Show Jim!" James L. Brooks stood up from the couch he'd been sitting on. As Caan walked over to him, he kept repeating, in the melodramatically panicked tones of a victim in a teen slasher film, "No. No. No. No. No." Caan poked Brooks in the chest. Brooks hurled himself backward onto the couch, crying out in exaggerated agony. "Holy shit!" Brooks yelled, touching his chest in mock astonishment. "Holy shit! You gotta teach me that, Jimmy!" Caan smiled. He was very happy. Enter Mr. Henry. In the spring of 1994, I'll Do Anything flopped. Suddenly, Bottle Rocket wasn't a side project to Brooks anymore. It was his chance to rebound from disaster--to prove to Hollywood he still had the magic touch. Wes and Owen showed him their various drafts. To their relief, Brooks seemed to like what he saw. Sometimes, though, Wes wondered if the rewritten scripts explained too much. But he didn't obsess over it. The shoot was drawing near. Come November of 1994, Bottle Rocket would finally take off. But first there was the matter of the Mentor Wars. L.M. "Kit" Carson and Cynthia Hargrave were embroiled in a minor power struggle with Brooks and Platt. Carson and Hargrave, whose sensibilities were grittier, were urging Owen and Wes to fight any attempts to turn Bottle Rocket into a more obviously commercial project. "What drew me to the story was the combination of innocence and irony," Carson says. "If I'd been involved, the irony would have been a lot stronger." He had many other suggestions as well, involving everything from characterization to pacing. "Cynthia and I were like parents," he says. But things had obviously changed. Carson realized that as the rewrite process dragged on, Wes and Owen were increasingly inclined to side with Platt and Brooks when disagreements arose. Finally, just a couple of weeks before Bottle Rocket began shooting in Dallas, Carson got a phone call from Wes. He asked Carson not to come to the set. Carson was taken aback. He explained, somewhat peevishly, that he'd visited the sets of a lot of very influential filmmakers. But if Wes Anderson wanted him to stay away, he'd do so. "He had two more parent figures now than when this whole thing started--Jim and Polly," Carson says. "He felt like it was time to cut the other ones loose." Platt and Brooks supported Wes' decision completely. Carson and Hargrave collected the money Columbia had agreed to pay them up front in exchange for their involvement with the movie. Since that day, they've had no formal input in Bottle Rocket. If Carson is bitter, he won't admit it publicly. The Bottle Rocket group is similarly circumspect. "One thing was pretty clear to everybody after that episode,"

says Bob Musgrave. "Wes might be a real quiet guy, but he's also tough. A lot of people underestimate him at first. But when he makes up his mind what he wants to do, it doesn't matter whether you're Jim Brooks or Kit Carson. The guy is gonna stand his ground." Cut to a chilly weekend in November 1994. The Bottle Rocket crew was shooting scenes with James Caan at the Brookhaven Country Club in Farmers Branch. In the parking lot was a row of trailers where the filmmakers and actors retreated to grab a little privacy. The largest--a behemoth that looked like a metal silverfish--belonged to Caan. He was standing in front of it, talking to Polly Platt, a small, slender, sixtyish woman with close-cropped grey hair. Platt left. Caan stood alone in front of his trailer. He squinted up into the sky as if looking for UFOs. Suddenly he whirled around. He slapped the trailer with the flats of his hands. WHUM! WHUM! WHUM! WHUM! WHUM! WHUM! Then he dropped to the pavement and did 10 push-ups in rapid succession. He sprang to his feet, swung his arms down into a pincer shape, and flexed his torso muscles. "HNNnnggh!" he grunted, with the mortal agony of someone passing a kidney stone. Caan dropped his arms. He rolled his head on his neck, popping cartilage. Then he shut his eyes and took a series of deep, slow breaths. For a moment, his distinctive face, deeply lined from age and drink, looked serene. Then he climbed up into his trailer and shut the door. "I can see how people might think Jimmy is a little strange," Owen Wilson said later that day. "But he's a great guy when you get to know him." Caan was in town for two short weeks. During that time, he would be treated like the legend he was. People were present to ensure that his personal space was disturbed only when absolutely necessary. When Caan wasn't on the set with the other actors, he was ensconced in his trailer, working through his lines, practicing martial-arts routines with Tak, or just taking it easy. The rehab seemed to have stuck. Sometimes at night Caan went out with Polly Platt and the Bottle Rocket boys and spun long, colorful, sometimes raunchy yarns about his film career, talking about work with Pacino, Duvall, and Brando on The Godfather. On the set, Caan usually looked chipper and relaxed-- when he wasn't doing surreal calisthenics, anyway. But he was under just as much pressure as Wes Anderson, the Wilsons, and Bob Musgrave--pressure of a different kind. This shoot was very important to him, Platt explained, because it represented his first paid gig since finishing drug and alcohol rehab. "Everybody's watching to see what happens," Platt said. "Jimmy says he's changed, and everybody out here believes he's changed. But there are a lot of people out there who think he hasn't changed. What Jimmy has done is accept a very small part in a small movie to prove he's a professional who can get through a shoot without getting into trouble." Owen talked about a night when he ate with Caan in his trailer. "Jimmy looked around it and said to me, 'See this, kid? This represents 30 years of work.' And he meant it. He was proud to have been in movies that long." But the hard living had taken its toll. Caan looked older than his 55 years. Now that he was finally sober, he had plenty of quiet time to reflect on the bad old days. The situation sometimes made him melancholy. "He said that when he looks back at the movies he's done, some of them are difficult to watch because of his condition in them," Owen said. "Sometimes he got kind of sad talking about that." There were only a few days left in the shoot. The cast and crew had been all over Dallas, filming scenes on location at Taylors Bookstore at NorthPark, Goff's Hamburgers, and the Hinckley Cold Storage building in Deep Ellum. And now, in a West End warehouse serving as Mr. Henry's headquarters, about 40 flashily dressed extras were milling around in specifically marked areas of a party set and talking without making any noise; their murmuring voices would be dubbed in during postproduction. Luke