#D. terrelli

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

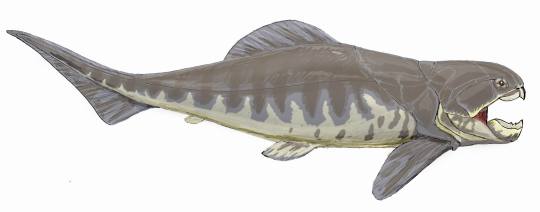

Deep in the ancient oceans, lurks the mighty Dunkleosteus. A bit of Blockbench paleo art from a little while back i never posted.

Based on the recent, more rotund, reconstruction of D. terrelli, still quite the fearsome beast!

Been some time since i did any paleoart so it was great to finally get back to it again!

Let me know what you think!

#my art#artists on tumblr#3dartist#blockbench#paleo art#paleoart#paleoblr#paleontology#prehistoric animals#dunkleosteus#D. terrelli#dunkleosteus terrelli#devonian#fish#mineblr#minecraft#placoderm#palaeontology

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Daily fish fact #660

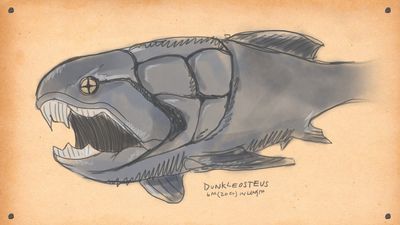

Dunkleosteus!

There's ten described species of Dunkleosteus, though the genus is generally thought to be a "wastebasket taxon", which is a taxon that exists only to insert species into that we do not know where else to put them. The most well-known dunkleosteus is Dunkleosteus terrelli, and it is also the largest species! Studies done just this year that measured the skull and the length of the space between the eye and the rest of the head estimated that the average D. terrelli was about 3 and a half meters long (11 feet)! However, it is left to see if our knowledge of the animals improve and this information changes.

111 notes

·

View notes

Note

Jhonen Vasquez is a dick

Dunkleosteus is an extinct genus of large arthrodire ("jointed-neck") fish that existed during the Late Devonian period, about 382–358 million years ago. It was a pelagic fish inhabiting open waters, and one of the first apex predators of any ecosystem.[1]

Dunkleosteus consists of ten species, some of which are among the largest placoderms ("plate-skinned") to have ever lived: D. terrelli, D. belgicus, D. denisoni, D. marsaisi, D. magnificus, D. missouriensis, D. newberryi, D. amblyodoratus, D. raveri, and D. tuderensis. The largest and best known species is D. terrelli. Since body shape is not known, various methods of estimation put the living total length of the largest known specimen between 4.1 to 10 m (13 to 33 ft) long and weigh around 1–4 t (1.1–4.4 short tons).[2] However, lengths of 5 metres (16 ft) or more are poorly supported and the most extensive analyses support smaller size estimates.[2][3]

Dunkleosteus could quickly open and close its jaw, creating suction like modern-day suction feeders, and had a bite force that is considered the highest of any living or fossil fish, and among the highest of any animal. Fossils of Dunkleosteus have been found in North America, Poland, Belgium, and Morocco.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dunkleosteus

(temporal range: 382-358 mio. years ago)

[text from the Wikipedia article, see also link above]

Dunkleosteus is an extinctgenus of large arthrodire fish that existed during the Late Devonian period, about 382–358 million years ago. It consists of ten species, some of which are among the largest placoderms to have ever lived: D. terrelli, D. belgicus, D. denisoni, D. marsaisi, D. magnificus, D. missouriensis, D. newberryi, D. amblyodoratus, D. raveri, and D. tuderensis, and the largest and most well known species is D. terrelli. Since body shape is not known, various methods of estimation put the living total length of the largest known specimen between 4.1 to 10 m (13 to 33 ft) long and weigh around 1–4 t (1.1–4.4 short tons).[1]Dunkleosteus could quickly open and close its jaw, like modern-day suction feeders, and had a bite force of 4,414–6,170 N (450–629 kgf; 992–1,387 lbf) at the tip and 5,363–7,495 N (547–764 kgf; 1,206–1,685 lbf) at the blade edge.[2][3] Numerous fossils of the various species have been found in North America, Poland, Belgium, and Morocco. Dunkleosteus was a pelagic fish inhabiting open waters, and an apex predator of its ecosystem.

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

Trick or treat! 💀

Happy Halloween! You get:

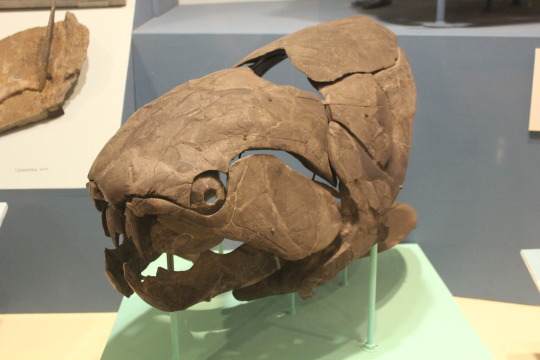

This picture I took of Dunkleosteus terrelli at the DC Museum of Natural History!

And:

Round Meal

Congratulations! :D

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

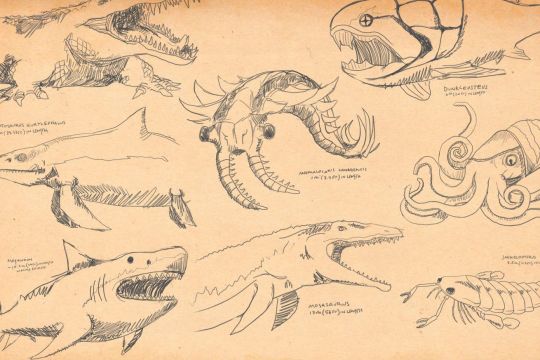

do you like ancient sea creatures? or have a favorite? mine is probably anomalocaris.

I've honestly never had any particular thought about ancient sea creatures, though when I was little I had an encyclopedia of prehistoric life and every time I read it I would always flip to the page about Dunkleosteus because I found them so scary! So I decided to reread about Dunkleosteus. The encyclopedia is from 2008 so it's got those classic awful renditions of the creatures such as these ones:

and there's probably a shit ton of incorrect information such as in this diagram,

which depicts the full body of the Dunkleosteus and says it was *at least* 5m long, despite the fact that no one reaally knows what its body looks like seeing as the fossils that have been found have, I think, only been found of the jaw of the fish and, since the body of the fish is mostly unknown, so is its length. There have been estimations of the length of Dunkleosteus, more specifically D. Terrelli since its the biggest one, ranging from 10m to about 3m, but the most recent estimations have put its length at almost 4ish metres. I feel like my 2008 encyclopedia was a little bit too confident about this particular fish.

Anyway, Dunkleosteus is definitely my favourite ancient sea creature. I've almost certainly got some information about it incorrect (there's only so much an old textbook and a Wikipedia page can do for you) so if anyone knows more about these guys please correct anything I got wrong. And thanks for the ask :)

[Image ID in alt text]

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"its a cool tattoo but why does the shark look like that"

"idk. by the way its not actually a shark its called Dunkleosteus it's an extinct genus of large arthrodire ("jointed-neck") fish that existed during the Late Devonian period, about 382–358 million years ago. It was a pelagic fish inhabiting open waters, and one of the first apex predators of any ecosystem.[1]

Dunkleosteus consists of ten species, some of which are among the largest placoderms ("plate-skinned") to have ever lived: D. terrelli, D. belgicus, D. denisoni, D. marsaisi, D. magnificus, D. missouriensis, D. newberryi, D. amblyodoratus, D. raveri, and D. tuderensis. The largest and best known species is D. terrelli. Since body shape is not known, various methods of estimation put the living total length of the largest known specimen between 4.1 to 10 m (13 to 33 ft) long and weigh around 1–4 t (1.1–4.4 short tons).[2] However, lengths of 5 metres (16 ft) or more are poorly supported and the most extensive analyses support smaller size estimates.[2][3]

Dunkleosteus could quickly open and close its jaw, creating suction like modern-day suction feeders, and had a bite force that is considered the highest of any living or fossil fish, and among the highest of any animal. Fossils of Dunkleosteus have been found in North America, Poland, Belgium, and Morocco.

Discovery

Dunkleosteus fossils were first discovered in 1867 by Jay Terrell, a hotel owner and amateur paleontologist wh-"

wait okay so rockstar au is a no-stand au but what if one of squalos tattoos was clash

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

D. terrelli

312 notes

·

View notes

Text

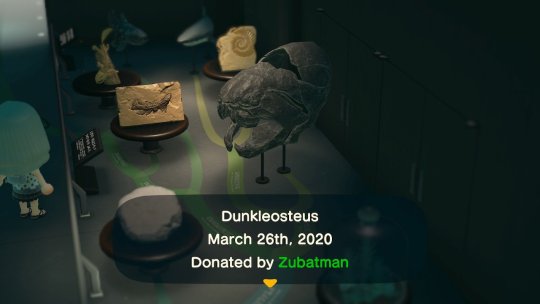

Animal Crossing Fish - Explained #100

Brought to you by a marine biologist who has written 100 of these holy crap.

CLICK HERE FOR THE AC FISH EXPLAINED MASTERPOST!!!

Here we are at 100 and I’m celebrating by covering my favorite fossil, as well as the last fossil fish (we have two more aquatic fossils left) - Dunkleosteus. The Dunk is a favorite among fish enthusiasts, at least from my experience. It represents the very best of the Placoderms, an ancient lineage of fish that introduced and exemplified many of the evolutionary milestones vertebrates like us still take for granted. Nevertheless, they didn’t exist on Earth for long, but they were hella cool.

As big as the fossil appears, it is just one fossil piece in ACNH, so if you haven’t found it yet, guess you’ll have to just keep digging everyday until you do. (Also, “Zubatman” is my husband’s username in the game, in case you were confused lol)

Like I said above, Dunkleosteus belonged to a class of fish called the Placoderms (Placodermi), an ancient lineage of fish that has no relatives alive today. They appeared and then went extinct all WAY before the dinosaurs ever set foot on Earth, their hayday being during the Devonian Period, ending some 359 million years ago. The class name means “plated skin” and that’s really the first feature you would notice about these fish. About half of their bodies were covered in bony plate armor, and most species were bottom dwellers that could have really used the help. Predators, such as sharks, were already prowling the seas at this time. However, Placoderms weren’t just here to be prey; they also evolved into some of the most massive predators of the Devonian.

Of the ten species of Dunkleosteus we know of (since that’s the genus name), the largest was the type species for the genus, Dunkleosteus terrelli, which grew to be about 20 feet (about 6.1m) in length, we think. I’m pretty sure this is the species the fossil is meant to represent, since D. terrelli was widespread and is the most well-known of the Placoderms in general.

^Here’s what the fossil looks like irl. (Ghedoghedo, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons)

^And here’s a common reconstruction of what it may have looked like in life. This is a toy of a D. terrelli! where were these toys when I was a kid???

I say this is a “common” reconstruction of Dunkleosteus terrelli because we actually don’t know what the second half of the fish looked like. We can do our best to reimagine it based on the rare, well-preserved fossils of its relatives, but the truth is, we don’t know for sure. Like sharks, Placoderms had skeletons made of cartilage (the flexible material that makes your ears and nose). Cartilage doesn’t preserve as well as bone, and so, all we have of this animal are its plates that did preserve better to become fossils.

Like I said above, Placoderms exemplified and even introduced some evolutionary milestones. For one, Placoderms were among the first classes of Vertebrates to have jaws and really use them well. Before sharks and placoderms, Vertebrates were jawless. Jaws were an extremely important adaptation for Vertebrates, and you can tell because we all have them now (except for the Agnathans, the hagfish and lampreys). Jaws allowed Vertebrates to manipulate food better, break it down, and especially help predators catch their food. In that vein, Dunkleosteus terrelli, being the largest predator of its time, was probably the first super-predator in the world’s oceans, eating other predators as part of its natural diet. With teeth like scissor blades that are believed to have self-sharpened themselves every time the animal opened and closed its mouth, The Dunk was truly a sea monster.

Not only that, but Placoderms are also recognized as the first vertebrates to have live birth, in which the male and female copulate internally and then the female keeps the eggs inside her to incubate and then birth babies live and ready to go. The discovery of a Placoderm fish fossil showing a female that died in the process of live birth pushed live birth in vertebrates back some 200 million years.

Unfortunately, like all good things, the Placoderms didn’t last. They went extinct at the end of the Devonian, with only a single group lasting into the first part of the Carboniferous period before becoming extinct as well. Today, there are no surviving Placoderms. It’s believed their heavy armor is what ultimately did them in, becoming outcompeted by the armor-less, but much more agile sharks and bony fish.

And there you have it. Fascinating stuff, no?

#placoderms#dunkleosteus#fossil#fish#acnh#animal crossing#animal crossing new horizons#science in video games#animal crossing fish explained

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

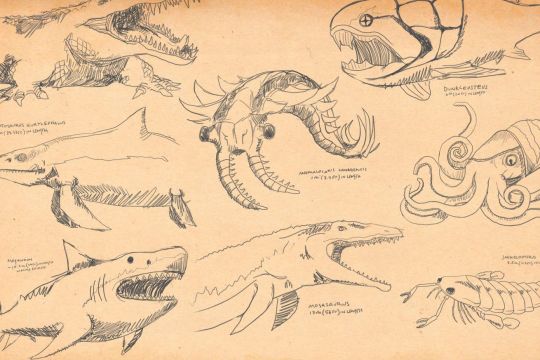

Here are 9 of the most badass animals ever to swim

Art by Tyson Whiting

Say hello to some horrifying sea monsters

This article was originally published on SB Nation a while ago, but was always intended for a Secret Base-y audience. So if you haven’t seen it yet, here you go!

The Earth has some very cool aquatic predators swimming about. Thanks to their intelligence and pack-hunting techniques, orcas are, perhaps, the most dangerous hunters ever to swim the ocean. Saltwater crocodiles are bulletproof murder tanks. And the great white shark, of course, needs no introduction. But now that we’re talking about terrifying underwater murder-beasts, why just settle for just the ones we have around now?

Underwater murder-beasts have a long and distinguished (pre-)history, and I thought it would be fun to introduce y’all to some new pals. TO THE IMAGINARY TIME MACHINE!

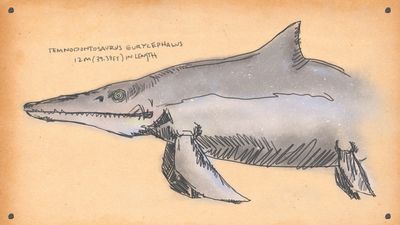

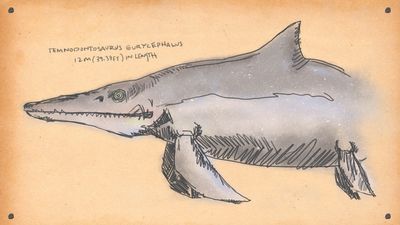

Temnodontosaurus eurycephalus

Grumpy croco-dolphin

Ichthyosaurs evolved 250 million years ago. In the aftermath of the Permian extinction, which killed off a frankly horrifying number of creatures, a group of terrestrial reptiles took to the depleted seas. Fast-forward a little bit and you have primitive ichthyosaurs, creatures so well adapted to oceanic life that they ended up looking like a cross between a crocodile and an extremely ill-tempered, extremely large dolphin.

Fast-forward even further, to the early Jurassic (175 million years ago), and you have Temnodontosaurus eurycephalus. It’s not the largest ichthyosaur ever to grace the seas, but it’s up there, and it’s a far more developed predator than its giant forebears. Somewhere around 30 feet long, T. emnodontosaurus was a powerful swimmer with strong jaws, well-equipped to chow down on other Jurassic swimmers. One closely-related species possessed the largest eyes of any known animal, perfect for hunting in deeper oceanic waters; another has been found with the remains of a different ichthyosaur in is stomach.

This monster considered 13-foot oceanic reptiles a delicious snack. It was also fast. Spare a thought for the poor ocean-going creatures minding their own business before one of these huge assholes rams into them from below at speed, opens those long, toothy jaws and turns them into lunch.

Deinosuchus hatcheri

Dinosaur hunter

Take a saltwater crocodile. Actually, it’s probably best not to. They are, after all, 20-foot, 2,000-pound apex predators more than happy to eat anything they come across, including you. Salties are strong, fast and surprisingly smart. They are at home in the open ocean as well as along the coast. Like all crocodiles, they’re ambush predators who use water as cover to attack their prey. Unlike most crocodiles they’re capable of jumping clear out of the water to get to it. They have the strongest bite of any living animal.

Right. Now that you have a saltwater crocodile in your head, make one, oh, twice as big. Yeah, like that. Decently boat-sized. Terrifying teeth in terrifying, dino-crushing jaws. Armored skin thick enough to turn aside more or less anything.

Your terrifying vision is Deinosuchus hatcheri, a crocodile adapted to more or less the exact same situation as a modern saltwater but in a world inhabited by giant dinosaurs. During the late Cretaceous (80 million years ago), North America was split by a shallow sea, the Western Interior Seaway. D. hatcheri was present on both the western side of the seaway (a slightly smaller species dominated the east), happily chowing through dinosaurs who were foolish enough to get too close.

Anomalocaris canadensis

Nightmare Shrimp

So far we’ve had a dolphin analogue in Temnodontosaurus and an actual crocodile. Cool, but nowhere near the sort of weirdness the past can provide. So let’s go to the deep, deep past, revealed wonderfully by the Burgess Shale. Here we shall find the NIGHTMARE SHRIMP.

One of the problems with studying the very earliest phase of animal life — we’re talking half a billion years at this point — is that it’s squishy, and squishy is not of much benefit when it comes to preserving fossils. Thanks to a fluke of geology, the conditions that produced the Burgess Shale were also capable of preserving soft tissue, giving palaeontologists a rare chance to look into what the seas looked like during the first days of the animal kingdom.

They looked extremely weird. The fauna found in the Burgess Shale was almost obnoxiously uncategorisable. One famous example is the worm Hallucigenia, which so confused everyone involved that it was reconstructed upside-down for the better part of a decade. Another is Opabinia, which looks sort of like a five-eyed miniature vacuum cleaner. I promise I am not making this up.

Anyway, all these critters were apparently food for the ocean’s first proper predator.

With good eyes set on flexible stalks and a surprising turn of speed, Anomalocaris canadensis cruised the Pre-Cambrian seas in death-shrimp mode. It was a full meter long, dwarfing most of its companions in the Burgess Shale. It was also delightfully strange-looking. It is so odd, in fact, that when it was discovered its various body parts were assigned to several different animals.

A. canadensis would be higher on this list if we could be sure of what it actually ate. Long-held to be a trilobite-hunter, recent studies have shown it would probably have had to restrict itself to soft-bodied prey due to relatively flimsy mouthparts, and therefore could only have actually eaten a trilobite just after a moult. But it’s much more fun to imagine this guy roaming the seafloor chomping down on everything, so that’s what we’ll do.

Disclaimer: an old friend of mine is a paleontologist who specializes in the Burgess Shale fossils. I did not contact him for this story, because I am consumed by envy whenever I so much as think about him.

Cameroceras

Spiky death-squid

Back in the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic, cephalopods were armored critters, much like our modern nautilus. The most famous of them, and one of the most widely known extinct animals ever, is the spiral-shelled ammonite. Since they had hard shells, they’re extremely common in marine strata. They also got surprisingly large. The biggest-known ammonite was two meters across. Imagine that thing trying to swim.

Ammonites weren’t the only armored cephalopod prowling the ancient seas, however. The orthocones were straight-shelled versions, and some of those got really, really big. Like Cameroceras. Current estimates put Cameroceras’s shell at upwards of six meters long. That’s three average-sized men stacked on each others’ shoulders.

Somehow this monster was still able to get about in the Ordovician seas. It’s quite hard to imagine it chasing anything around, so it presumably surprised trilobites etc. at nighttime or dug it out of the mud, but since paleoecology is at least in part about imagination, right now I’m enjoying Cameroceras retracting its head deep into its shell and pretending to be a cave before trying to eat whatever entered. It wouldn’t be quite big enough to swallow the Millennium Falcon, buuuuuuuuut ...

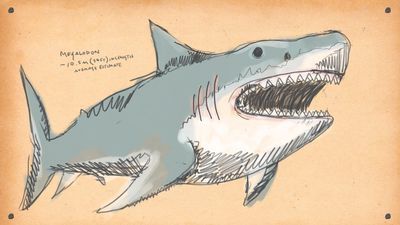

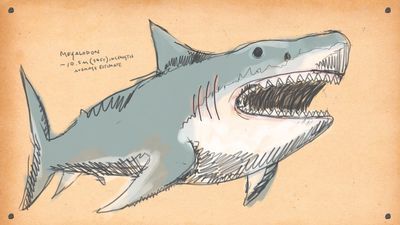

Carcharocles megalodon

The shark that eats planets

Megalodon needs no introduction. The great white shark has a profound hold on popular culture, but its long-gone big sister isn’t far behind. Megalodon made even the most vicious shark in today’s seas look like a toy. Since sharks are mostly soft tissue, they don’t fossilize as well as we’d like, but their teeth do, and Megalodon’s tell a terrifying story.

Megalodon died out only relatively recently. It wasn’t quite contemporaneous with human beings, but its extinction was recent enough that there are plenty of folks willing to tell tall tales of how it might still be swimming somewhere in the depths of the ocean. If it was, probably best not to get anywhere near it — a Megalodon may have had a bite force of up to 10 times the strength of a great white. That’d be a bad day.

What were those huge jaws for? Whales. Apparently, these things liked to swim up from underneath its prey and bite through their chest to reach their internal organs. The ability to kill a whole-ass whale with one bite is honestly horrifying, even if whales in Megalodon’s day were a little smaller than the current batch of great rorquals.

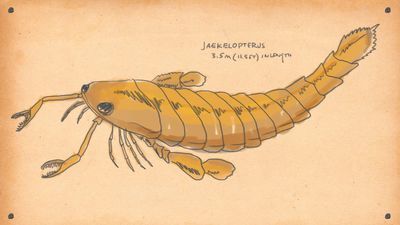

Jaekelopterus rhenaniae

Sea Scorpion

Did you know ‘sea scorpions’ were a thing? Sea scorpions were a thing. Since eurypterids (to give them their proper name) went extinct hundreds of millions of years ago, we don’t have very good comparisons for what these things were like. So let’s get creative. Let’s take a lobster. Despite their ferocious armament, lobsters are relatively placid creatures. They’re not averse to grabbing a fish here or a mollusk there, but they’re not built for hunting. Let’s make the required tweaks.

We need to add eyes. Let’s make them big and sensitive and set for stereoscopic vision, which allows those pincers to be used more effectively to grab prey. Let’s make them better swimmers, too — we’ll add some paddles for agility and short bursts of speed. Let’s make their claws spikier, just for sheer scare value.

Oh and let’s make them 10 feet long and perfectly happy to eat you alive. Now you have a Jaekelopterus. Aren’t you glad they’re dead?

Dunkleosteus terrelli

A, uh, fish-tank

When evolution first came up with bone, it got a little bit carried away. Well, a lot carried away. The era of armored fishes is one of the most fabulously strange in the entire history of the planet. (A personal favorite of mine is Lunapsis, which looks like a fish had a baby with Batman’s utility belt.) With bone-plated heads and upper bodies, these fish probably didn’t swim very well, but who cares? They looked cool as hell, and with that body armor they were well protected against predators.

Which, as it turns out, is the sort of inspiration nature needs to come up with some better predators*. Enter Dunkleosteus, a monster armored fish with a set of jaws which could rip straight through the armor of any other fish slowly swimming through the Devonian ocean. Known to be 20 feet long, it didn’t really have teeth so much as a huge bony beak, which honestly makes the whole contraption even more frightening, like some sort of mobile oceanic guillotine.

*I’m being overly teleological here. Forgive me. Nature, of course, does not ‘come up with’ anything.

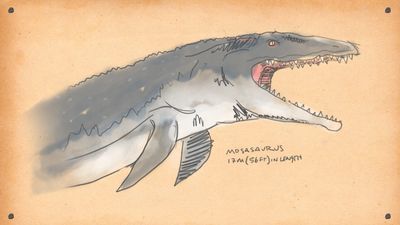

Mosasaurus hoffmanni

For whatever reason, the fauna of Cretaceous period got big. Really, really big. On land, we had Tyrannosaurus Rex. In the skies, azhdarchids the size of small aircraft coasted from thermal to thermal. And in the shallow seas, we had another monster: Mosasaurus.

Mosasaurus was essentially an enormous — estimates have it as almost 60 feet long — ocean-going lizard. Its legs were replaced with bladed paddles for maneuverability and it had a powerful tail for direct propulsion. Mosasaurus ate everything it could get in its mouth, which was a) double-hinged for extra capacity and b) already pretty capacious to begin with.

It would have hung around near the surface of the ocean, where there was an abundance of prey. Mosasaurus could have waited for other marine reptiles (such as Archelon, the largest turtle known) to come up to breathe, grab low-flying pterosaurs on fishing expeditions, or simply have picked off the many large fish that swam the Cretaceous seas.

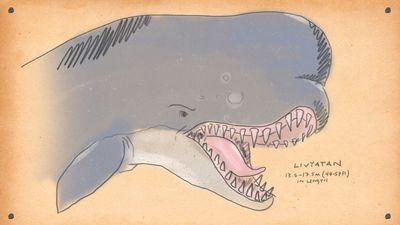

Livyatan Melvilli

Moby-Dick’s even-scarier dad

In 1820, the Essex was lost in the southern Pacific Ocean. The ship had been sent out to hunt for sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus, since you asked), but soon had the tables turned when it was attacked and sunk by a ferocious bull. Of the 20 crew, only eight survived, and the incident went on to inspire a famous book about whales which you may have heard of.

What you probably haven’t heard of is Livyatan. Modern sperm whales are enormous creatures, but very rare boat attacks aside, they’re only really dangerous to their favorite prey, deep-swimming squid. But not so long ago, geographically speaking, there were also a group of ‘macroraptorial’ sperm whales. These didn’t eat squid. Instead, they competed with Megalodon to hunt other great whales.

Livyatan’s teeth are some of the most awe-inspiring fossils in the world. The biggest ones are 12 inches long and look like artillery shells. Estimates have Livyatan as sitting a touch smaller than its modern friends, but those teeth indicate that it would have been significantly more vicious, fully capable of cutting a sperm whale into very bloody chunks.

It’s not clear whether or not Livyatan hunted alone or in packs, like a modern killer whale, but it had the power and size to be able to plausibly compete with Megalodon even solo. The crew of the Essex found out that a bull sperm whale could be a formidable opponent; one suspects Livyatan would have left even fewer survivors.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Work in progress underpainting for Dunkleosteus terrelli. Way back during the Devonian period, around 382 to 358 million years ago the world was very different, while life on land was still fairly simple, life in the oceans was booming. Before the first tetrapods (creatures with four limbs like all land vertebrates including humans) appeared in the fossil record and around the time when the first creatures with biting jaws showed up nature spawned a fish with a bite unlike any other before or since.

Dunkleosteus was a member of a group of fish called placoderms, these fish were one of many groups of armored fish that lived during the Devonian; this armor often took the form of bony plates, almost like an exoskeleton, most often concentrated around the head.

D. terrelli was a super-predator that not only had it's own armor for defense but also managed to adapt it's bony plates into an offensive weapon capable of slicing through anything the Devonian seas could offer. Rather than true teeth, the plates in it's mouth formed into sharpened cleaver like formations, they even self-sharpened whenever it closed it's mouth on whatever had the misfortune to be within reach.

The type species, Dunkleosteus terreli was the largest of it's genus, it was originally described in 1873 under the name Dinicthys herzeri by John Newberry. It had an estimated length of 19.7 feet and a weight of around 1.1 tons, with some estimates going even larger. It had an amazing bite force of 11,000 pounds, about 88,000 pounds per square inch per fang tip, giving it the strongest bite of any fish to have ever lived.

#workinprogress#wip#dunkleosteus#fish#placoderm#devonian#paleo#paleontology#paleoart#sciart#science#educational#naturalhistory#extinction#exinctanimals#digitalart#digitalillustration#illustration#art#painting#drawing#maine#maineart#newengland#artistsontumblr

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dunkleosteus "intermedius" (synonym of D. terrelli). Based on famous skeletal drawing from B. Dean

By Creator:Dmitry Bogdanov ([email protected]) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

0 notes

Text

Here are 9 of the most badass animals ever to swim

Art by Tyson Whiting

Say hello to some horrifying sea monsters

The Earth has some very cool aquatic predators swimming about. Thanks to their intelligence and pack-hunting techniques, orcas are, perhaps, the most dangerous hunters ever to swim the ocean. Saltwater crocodiles are bulletproof murder tanks. And the great white shark, of course, needs no introduction. But now that we’re talking about terrifying underwater murder-beasts, why just settle for just the ones we have around now?

Underwater murder-beasts have a long and distinguished (pre-)history, and I thought it would be fun to introduce y’all to some new pals. TO THE IMAGINARY TIME MACHINE!

Temnodontosaurus eurycephalus

Grumpy croco-dolphin

Ichthyosaurs evolved 250 million years ago. In the aftermath of the Permian extinction, which killed off a frankly horrifying number of creatures, a group of terrestrial reptiles took to the depleted seas. Fast-forward a little bit and you have primitive ichthyosaurs, creatures so well adapted to oceanic life that they ended up looking like a cross between a crocodile and an extremely ill-tempered, extremely large dolphin.

Fast-forward even further, to the early Jurassic (175 million years ago), and you have Temnodontosaurus eurycephalus. It’s not the largest ichthyosaur ever to grace the seas, but it’s up there, and it’s a far more developed predator than its giant forebears. Somewhere around 30 feet long, T. emnodontosaurus was a powerful swimmer with strong jaws, well-equipped to chow down on other Jurassic swimmers. One closely-related species possessed the largest eyes of any known animal, perfect for hunting in deeper oceanic waters; another has been found with the remains of a different ichthyosaur in is stomach.

This monster considered 13-foot oceanic reptiles a delicious snack. It was also fast. Spare a thought for the poor ocean-going creatures minding their own business before one of these huge assholes rams into them from below at speed, opens those long, toothy jaws and turns them into lunch.

Deinosuchus hatcheri

Dinosaur hunter

Take a saltwater crocodile. Actually, it’s probably best not to. They are, after all, 20-foot, 2,000-pound apex predators more than happy to eat anything they come across, including you. Salties are strong, fast and surprisingly smart. They are at home in the open ocean as well as along the coast. Like all crocodiles, they’re ambush predators who use water as cover to attack their prey. Unlike most crocodiles they’re capable of jumping clear out of the water to get to it. They have the strongest bite of any living animal.

Right. Now that you have a saltwater crocodile in your head, make one, oh, twice as big. Yeah, like that. Decently boat-sized. Terrifying teeth in terrifying, dino-crushing jaws. Armored skin thick enough to turn aside more or less anything.

Your terrifying vision is Deinosuchus hatcheri, a crocodile adapted to more or less the exact same situation as a modern saltwater but in a world inhabited by giant dinosaurs. During the late Cretaceous (80 million years ago), North America was split by a shallow sea, the Western Interior Seaway. D. hatcheri was present on both the western side of the seaway (a slightly smaller species dominated the east), happily chowing through dinosaurs who were foolish enough to get too close.

Anomalocaris canadensis

Nightmare Shrimp

So far we’ve had a dolphin analogue in Temnodontosaurus and an actual crocodile. Cool, but nowhere near the sort of weirdness the past can provide. So let’s go to the deep, deep past, revealed wonderfully by the Burgess Shale. Here we shall find the NIGHTMARE SHRIMP.

One of the problems with studying the very earliest phase of animal life — we’re talking half a billion years at this point — is that it’s squishy, and squishy is not of much benefit when it comes to preserving fossils. Thanks to a fluke of geology, the conditions that produced the Burgess Shale were also capable of preserving soft tissue, giving palaeontologists a rare chance to look into what the seas looked like during the first days of the animal kingdom.

They looked extremely weird. The fauna found in the Burgess Shale was almost obnoxiously uncategorisable. One famous example is the worm Hallucigenia, which so confused everyone involved that it was reconstructed upside-down for the better part of a decade. Another is Opabinia, which looks sort of like a five-eyed miniature vacuum cleaner. I promise I am not making this up.

Anyway, all these critters were apparently food for the ocean’s first proper predator.

With good eyes set on flexible stalks and a surprising turn of speed, Anomalocaris canadensis cruised the Pre-Cambrian seas in death-shrimp mode. It was a full meter long, dwarfing most of its companions in the Burgess Shale. It was also delightfully strange-looking. It is so odd, in fact, that when it was discovered its various body parts were assigned to several different animals.

A. canadensis would be higher on this list if we could be sure of what it actually ate. Long-held to be a trilobite-hunter, recent studies have shown it would probably have had to restrict itself to soft-bodied prey due to relatively flimsy mouthparts, and therefore could only have actually eaten a trilobite just after a moult. But it’s much more fun to imagine this guy roaming the seafloor chomping down on everything, so that’s what we’ll do.

Disclaimer: an old friend of mine is a paleontologist who specializes in the Burgess Shale fossils. I did not contact him for this story, because I am consumed by envy whenever I so much as think about him.

Cameroceras

Spiky death-squid

Back in the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic, cephalopods were armored critters, much like our modern nautilus. The most famous of them, and one of the most widely known extinct animals ever, is the spiral-shelled ammonite. Since they had hard shells, they’re extremely common in marine strata. They also got surprisingly large. The biggest-known ammonite was two meters across. Imagine that thing trying to swim.

Ammonites weren’t the only armored cephalopod prowling the ancient seas, however. The orthocones were straight-shelled versions, and some of those got really, really big. Like Cameroceras. Current estimates put Cameroceras’s shell at upwards of six meters long. That’s three average-sized men stacked on each others’ shoulders.

Somehow this monster was still able to get about in the Ordovician seas. It’s quite hard to imagine it chasing anything around, so it presumably surprised trilobites etc. at nighttime or dug it out of the mud, but since paleoecology is at least in part about imagination, right now I’m enjoying Cameroceras retracting its head deep into its shell and pretending to be a cave before trying to eat whatever entered. It wouldn’t be quite big enough to swallow the Millennium Falcon, buuuuuuuuut ...

Carcharocles megalodon

The shark that eats planets

Megalodon needs no introduction. The great white shark has a profound hold on popular culture, but its long-gone big sister isn’t far behind. Megalodon made even the most vicious shark in today’s seas look like a toy. Since sharks are mostly soft tissue, they don’t fossilize as well as we’d like, but their teeth do, and Megalodon’s tell a terrifying story.

Megalodon died out only relatively recently. It wasn’t quite contemporaneous with human beings, but its extinction was recent enough that there are plenty of folks willing to tell tall tales of how it might still be swimming somewhere in the depths of the ocean. If it was, probably best not to get anywhere near it — a Megalodon may have had a bite force of up to 10 times the strength of a great white. That’d be a bad day.

What were those huge jaws for? Whales. Apparently, these things liked to swim up from underneath its prey and bite through their chest to reach their internal organs. The ability to kill a whole-ass whale with one bite is honestly horrifying, even if whales in Megalodon’s day were a little smaller than the current batch of great rorquals.

Jaekelopterus rhenaniae

Sea Scorpion

Did you know ‘sea scorpions’ were a thing? Sea scorpions were a thing. Since eurypterids (to give them their proper name) went extinct hundreds of millions of years ago, we don’t have very good comparisons for what these things were like. So let’s get creative. Let’s take a lobster. Despite their ferocious armament, lobsters are relatively placid creatures. They’re not averse to grabbing a fish here or a mollusk there, but they’re not built for hunting. Let’s make the required tweaks.

We need to add eyes. Let’s make them big and sensitive and set for stereoscopic vision, which allows those pincers to be used more effectively to grab prey. Let’s make them better swimmers, too — we’ll add some paddles for agility and short bursts of speed. Let’s make their claws spikier, just for sheer scare value.

Oh and let’s make them 10 feet long and perfectly happy to eat you alive. Now you have a Jaekelopterus. Aren’t you glad they’re dead?

Dunkleosteus terrelli

A, uh, fish-tank

When evolution first came up with bone, it got a little bit carried away. Well, a lot carried away. The era of armored fishes is one of the most fabulously strange in the entire history of the planet. (A personal favorite of mine is Lunapsis, which looks like a fish had a baby with Batman’s utility belt.) With bone-plated heads and upper bodies, these fish probably didn’t swim very well, but who cares? They looked cool as hell, and with that body armor they were well protected against predators.

Which, as it turns out, is the sort of inspiration nature needs to come up with some better predators*. Enter Dunkleosteus, a monster armored fish with a set of jaws which could rip straight through the armor of any other fish slowly swimming through the Devonian ocean. Known to be 20 feet long, it didn’t really have teeth so much as a huge bony beak, which honestly makes the whole contraption even more frightening, like some sort of mobile oceanic guillotine.

*I’m being overly teleological here. Forgive me. Nature, of course, does not ‘come up with’ anything.

Mosasaurus hoffmanni

For whatever reason, the fauna of Cretaceous period got big. Really, really big. On land, we had Tyrannosaurus Rex. In the skies, azhdarchids the size of small aircraft coasted from thermal to thermal. And in the shallow seas, we had another monster: Mosasaurus.

Mosasaurus was essentially an enormous — estimates have it as almost 60 feet long — ocean-going lizard. Its legs were replaced with bladed paddles for maneuverability and it had a powerful tail for direct propulsion. Mosasaurus ate everything it could get in its mouth, which was a) double-hinged for extra capacity and b) already pretty capacious to begin with.

It would have hung around near the surface of the ocean, where there was an abundance of prey. Mosasaurus could have waited for other marine reptiles (such as Archelon, the largest turtle known) to come up to breathe, grab low-flying pterosaurs on fishing expeditions, or simply have picked off the many large fish that swam the Cretaceous seas.

Livyatan Melvilli

Moby-Dick’s even-scarier dad

In 1820, the Essex was lost in the southern Pacific Ocean. The ship had been sent out to hunt for sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus, since you asked), but soon had the tables turned when it was attacked and sunk by a ferocious bull. Of the 20 crew, only eight survived, and the incident went on to inspire a famous book about whales which you may have heard of.

What you probably haven’t heard of is Livyatan. Modern sperm whales are enormous creatures, but very rare boat attacks aside, they’re only really dangerous to their favorite prey, deep-swimming squid. But not so long ago, geographically speaking, there were also a group of ‘macroraptorial’ sperm whales. These didn’t eat squid. Instead, they competed with Megalodon to hunt other great whales.

Livyatan’s teeth are some of the most awe-inspiring fossils in the world. The biggest ones are 12 inches long and look like artillery shells. Estimates have Livyatan as sitting a touch smaller than its modern friends, but those teeth indicate that it would have been significantly more vicious, fully capable of cutting a sperm whale into very bloody chunks.

It’s not clear whether or not Livyatan hunted alone or in packs, like a modern killer whale, but it had the power and size to be able to plausibly compete with Megalodon even solo. The crew of the Essex found out that a bull sperm whale could be a formidable opponent; one suspects Livyatan would have left even fewer survivors.

2 notes

·

View notes