#Cubism (1909–1919)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

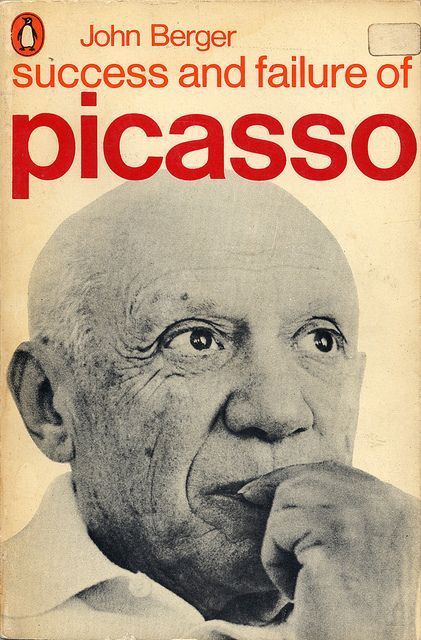

Pablo Picasso: The Revolutionary Artist Who Redefined Modern Art

“Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up.”— Pablo Picasso The 10 most famous works of Picasso Introduction Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) stands as one of the most influential artists in history, a pioneer who reshaped the boundaries of artistic expression. Known for his versatility, innovation, and prolific output, Picasso left an indelible mark on…

#20thCenturyArt#AbstractArt#AbstractMaster#ArtHistory#ArtIcon#ArtInspiration#ArtLovers#ArtRevolution#AvantGarde#BluePeriod#book-review#books#CreativeGenius#Cubism#Cubism (1909–1919)#DailyInspiration#DailyQuotes#DailyWisdom#EmpowermentQuotes#EncouragementQuotes#EveningThoughts#Expressionism#FamousArtist#fiction#Guernica#HappinessQuotes#InnovativeArt#InspirationalQuotes#InspiringWords#Late Period and Experimentation (1938–1973)

0 notes

Photo

1. Early Neo-Impressionism (Pre-1909) • Used pointillist techniques inspired by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. • Focused on light, color, and divisionism before transitioning to Cubism. 2. Cubism (1909-1919) • Developed a highly structured, geometric style, influenced by Paul Cézanne. • Played a key role in “Crystal Cubism”—a more refined, structured, and transparent approach to Cubist composition. • Multiple perspectives: Instead of using single-point perspective, he fragmented objects into geometric planes, showing them from different viewpoints. • Mathematical precision: His work often incorporated principles of geometry and proportion. • Worked closely with Albert Gleizes and co-wrote Du “Cubisme” (1912), an important theoretical text explaining Cubism. 3. Post-Cubist and Later Works (1920s-1950s) • Gradually moved toward a more classical and figurative style while retaining geometric clarity. • Explored themes of landscapes, still lifes, and portraits with refined structure. • Later works show influence from Surrealism and abstraction.

1 note

·

View note

Text

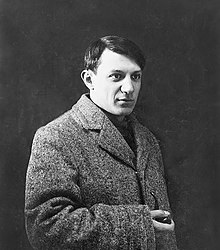

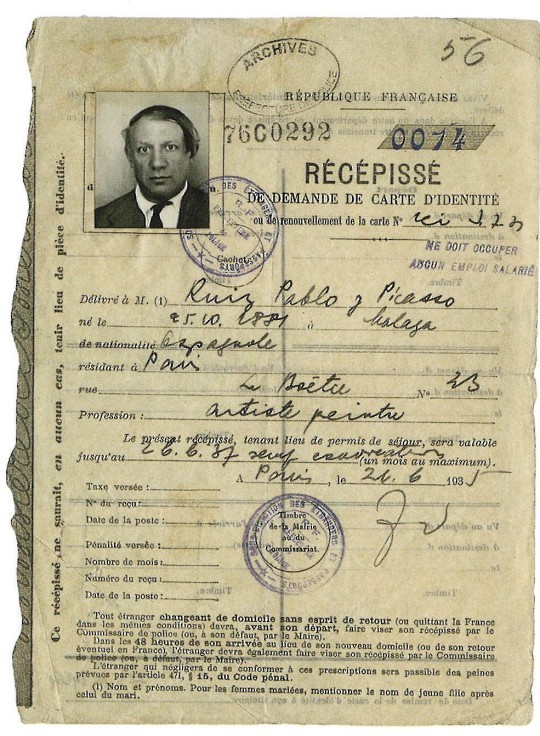

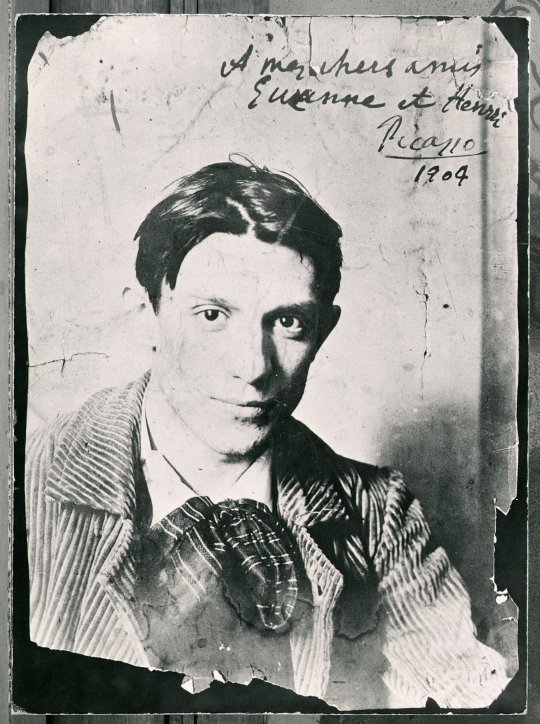

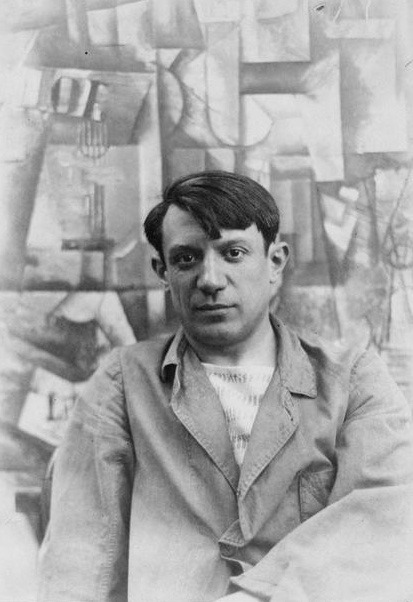

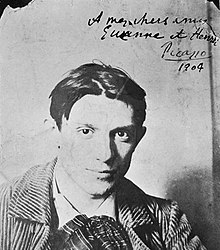

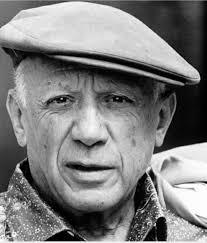

Arrivals & Departures . 25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973 . Pablo Ruiz Picasso

Pablo Ruiz Picasso was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist, and theatre designer who spent most of his adult life in France. One of the most influential artists of the 20th century, he is known for co-founding the Cubist movement, the invention of constructed sculpture, the co-invention of collage, and for the wide variety of styles that he helped develop and explore. Among his most famous works are the proto-Cubist Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907) and the anti-war painting Guernica (1937), a dramatic portrayal of the bombing of Guernica by German and Italian air forces during the Spanish Civil War.

Picasso demonstrated extraordinary artistic talent in his early years, painting in a naturalistic manner through his childhood and adolescence. During the first decade of the 20th century, his style changed as he experimented with different theories, techniques, and ideas. After 1906, the Fauvist work of the older artist Henri Matisse motivated Picasso to explore more radical styles, beginning a fruitful rivalry between the two artists, who subsequently were often paired by critics as the leaders of modern art.

Picasso's output, especially in his early career, is often periodized. While the names of many of his later periods are debated, the most commonly accepted periods in his work are the Blue Period (1901–1904), the Rose Period (1904–1906), the African-influenced Period (1907–1909), Analytic Cubism (1909–1912), and Synthetic Cubism (1912–1919), also referred to as the Crystal period. Much of Picasso's work of the late 1910s and early 1920s is in a neoclassical style, and his work in the mid-1920s often has characteristics of Surrealism. His later work often combines elements of his earlier styles.

Exceptionally prolific throughout the course of his long life, Picasso achieved universal renown and immense fortune for his revolutionary artistic accomplishments, and became one of the best-known figures in 20th-century art.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Artist Research - David Hockney

Cubism

Cubism is an early-20th-century avant-garde art movement that revolutionised European painting and sculpture, and inspired related artistic movements in music, literature, and architecture. In Cubist works of art, the subjects are analysed, broken up, and reassembled in an abstract form—instead of depicting objects from a single perspective, the artist depicts the subject from multiple perspectives to represent the subject in a greater context. This representation of different views of the subject pictured at the same time or successively is also called multiple perspective, simultaneity or multiplicity.

Originating in France during the 1910s and throughout the 1920s, Cubism has been considered the most influential art movement of the 20th century. The impact of Cubism was far-reaching and wide-ranging. In France and other countries, movements such as Futurism, Suprematism, Dada, Constructivism, Vorticism, De Stijl and Art Deco developed in response to Cubism. Offshoots of Cubism also developed, including Orphism, abstract art and later Purism.

The movement was pioneered mainly by Picasso and Georges Braque, as well as other notable artists. One primary influence that led to Cubism was the representation of three-dimensional form in the late works of Paul Cézanne.

Cubism is broken down into phases. The first phase of Cubism, known as Analytic Cubism, a phrase coined by Juan Gris, was both radical and influential as a short but highly significant art movement between 1910 and 1912 in France. A second phase, Synthetic Cubism, remained vital until around 1919, when the Surrealist movement gained popularity. English art historian Douglas Cooper proposed another scheme, describing three phases of Cubism in his book, The Cubist Epoch. According to Cooper there was "Early Cubism", (from 1906 to 1908) when the movement was initially developed in the studios of Picasso and Braque; the second phase being called "High Cubism", (from 1909 to 1914) during which time Juan Gris emerged as an important exponent (after 1911); and finally Cooper referred to "Late Cubism" (from 1914 to 1921) as the last phase of Cubism as a radical avant-garde movement.

Proto-Cubism

Proto-Cubism lasted between 1907 and 1911. This was the early beginnings of what would become the Cubist movement. Pablo Picasso's 1907 painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon has often been considered a proto-Cubist work

Another proto-cubist series of works was George Braque’s exhibition collection in Kahnweiler Gallery. A critic at the time, Louis Vauxcelles noted Brauqe’s nature of "reducing everything, places and a figures and houses, to geometric schemas, to cubes.”

This carried on. Critic Henri Matisse is known to have disparaged Braque’s pictures as “painting made of small cubes.” The critic Charles Morice also spoke of Braque's cubes. The motif had inspired Braque to produce three paintings marked by the simplification of form and deconstruction of perspective.

Georges Braque's 1908 Houses at L’Estaque (and related works) prompted Vauxcelles, in Gil Blas, 25 March 1909, to refer to it as bizarreries cubiques (cubic oddities). Gertrude Stein referred to landscapes made by Picasso in 1909, such as Reservoir at Horta de Ebro, as the first Cubist paintings.

The first organised group exhibition by Cubists took place at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris during the spring of 1911 in a room called 'Salle 41'; it included works by Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Fernand Léger, Robert Delaunay and Henri Le Fauconnier, yet no works by Picasso or Braque were exhibited.

By 1911 Picasso was recognised as the inventor of Cubism, while Braque's importance and precedence was argued later, with respect to his treatment of space, volume and mass in the L’Estaque landscapes.

Early Cubism

There was a distinct difference between Kahnweiler's Cubists and the Salon Cubists. Prior to 1914, Picasso, Braque, Gris and Léger (to a lesser extent) gained the support of a single committed art dealer in Paris, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, who guaranteed them an annual income for the exclusive right to buy their works

In contrast, the Salon Cubists built their reputation primarily by exhibiting regularly at the Salon d'Automne and the Salon des Indépendants, both major non-academic Salons in Paris. They were inevitably more aware of public response and the need to communicate.Already in 1910 a group began to form which included Metzinger, Gleizes, Delaunay and Léger. Together with other young artists, the group wanted to emphasise a research into form, in opposition to the Neo-Impressionist emphasis on colour.

The first public controversy generated by Cubism resulted from Salon showings at the Indépendants during the spring of 1911. This showing by Metzinger, Gleizes, Delaunay, le Fauconnier and Léger brought Cubism to the attention of the general public for the first time. Amongst the Cubist works presented, Robert Delaunay exhibited his Eiffel Tower, Tour Eiffel (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York).

The most extreme forms of Cubism were not those practiced by Picasso and Braque, who resisted total abstraction. Other Cubists, by contrast, especially František Kupka, and those considered ‘Orphists’ by Guillaume Apollinaire (Delaunay, Léger, Picabia and Duchamp), accepted abstraction by removing visible subject matter entirely. Kupka's two entries at the 1912 Salon d'Automne, Amorpha-Fugue à deux couleurs and Amorpha chromatique chaude, were highly abstract (or nonrepresentational) and metaphysical in orientation. Both Duchamp in 1912 and Picabia from 1912 to 1914 developed an expressive and allusive abstraction dedicated to complex emotional and sexual themes. Beginning in 1912 Delaunay painted a series of paintings entitled Simultaneous Windows, followed by a series entitled Formes Circulaires, in which he combined planar structures with bright prismatic hues; based on the optical characteristics of juxtaposed colors his departure from reality in the depiction of imagery was quasi-complete. In 1913–14 Léger produced a series entitled Contrasts of Forms, giving a similar stress to colour, line and form. His Cubism, despite its abstract qualities, was associated with themes of mechanisation and modern life.

Also labeled an Orphist by Apollinaire, Marcel Duchamp was responsible for another extreme development inspired by Cubism. The ready-made arose from a joint consideration that the work itself is considered an object (just as a painting), and that it uses the material detritus of the world (as collage and papier collé in the Cubist construction and Assemblage). The next logical step, for Duchamp, was to present an ordinary object as a self-sufficient work of art representing only itself. In 1913 he attached a bicycle wheel to a kitchen stool and in 1914 selected a bottle-drying rack as a sculpture in its own right.

Crystal cubism (1914 - 1918)

A significant modification of Cubism between 1914 and 1916 was signaled by a shift towards a strong emphasis on large overlapping geometric planes and flat surface activity. This grouping of styles of painting and sculpture, especially significant between 1917 and 1920, was practiced by several artists

The tightening of the compositions, the clarity and sense of order reflected in these works, led to its being referred to by the critic Maurice Raynal as 'crystal' Cubism.

Crystal Cubism, and its associative rappel à l'ordre, has been linked with an inclination—by those who served the armed forces and by those who remained in the civilian sector—to escape the realities of the Great War, both during and directly following the conflict. The purifying of Cubism from 1914 through the mid-1920s, with its cohesive unity and voluntary constraints, has been linked to a much broader ideological transformation towards conservatism in both French society and French culture.

Cubism in the later years

After World War I, with the support given by the art dealer and contractor Léonce Rosenberg, Cubism returned as a central issue for artists, and continued as such until the mid-1920s when its avant-garde status was rendered questionable by the emergence of geometric abstraction and Surrealism in Paris. Many Cubists, including Picasso, Braque, Gris, Léger, Gleizes, Metzinger and Emilio Pettoruti while developing other styles, returned periodically to Cubism, even well after 1925. Cubism reemerged during the 1920s and the 1930s in the work of the American Stuart Davis and the Englishman Ben Nicholson. In France, however, Cubism experienced a decline beginning in about 1925.

In 1918 Rosenberg presented a series of Cubist exhibitions at his Galerie de l’Effort Moderne in Paris. Attempts were made by Louis Vauxcelles to argue that Cubism was dead, but these exhibitions, along with a well-organized Cubist show at the 1920 Salon des Indépendants and a revival of the Salon de la Section d’Or in the same year, demonstrated it was still alive

In 1920, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler asserted that the Cubist depiction of space, mass, time, and volume supports (rather than contradicts) the flatness of the canvas.

Contemporary views of Cubism are complex, formed to some extent in response to the "Salle 41" Cubists, whose methods were too distinct from those of Picasso and Braque to be considered merely secondary to them. Alternative interpretations of Cubism have therefore developed.

What is cubism about?

The Cubism of Picasso and Braque had more than a technical or formal significance, and the distinct attitudes and intentions of the Salon Cubists produced different kinds of Cubism, rather than a derivative of their work.

The works exhibited by these Cubists at the 1911 and 1912 Salons extended beyond the conventional Cézanne-like subjects—the posed model, still-life and landscape—favoured by Picasso and Braque to include large-scale modern-life subjects. Aimed at a large public, these works stressed the use of multiple perspective and complex planar faceting for expressive effect while preserving the eloquence of subjects

Cubism explicitly relates the sense of time to multiple perspectives, giving symbolic expression to the notion of ‘duration.’ This was proposed by the philosopher Henri Bergson according to which life is subjectively experienced as a continuum, with the past flowing into the present and the present merging into the future.

One of the major theoretical innovations made by the Salon Cubists, independently of Picasso and Braque, was that of simultaneity. With simultaneity, the concept of separate spatial and temporal dimensions was comprehensively challenged. The subject matter was no longer considered from a specific point of view at a moment in time, but built following a selection of successive viewpoints, i.e., as if viewed simultaneously from numerous angles (and in multiple dimensions) with the eye free to roam from one to the other.

0 notes

Text

RESEARCH

PICASSOS TIMELINE - how oil pastels influenced Picasso

1899 – 1900: Early Picasso/1904 – 1906: Rose Period

Picasso began creating oil paintings at a young age with a Symbolist influence and natural palettes.

His art during the Rose Period incorporated warm colors and Catholic faith references.

1901 – 1904: Blue Period

Picasso's travels influenced his "blue period," which was based on Spain and featured melancholic themes.

1907 – 1909: African Art

Picasso, inspired by African art trends, moved towards a new artistic direction.

1909 – 1919: Cubism/1909 – 1912: Analytic Cubism

This period marked the breakdown of color and the dissection of forms in Picasso's art.

1919 – 1929: Surrealism

Picasso's trip to Italy in 1917 led to a neoclassical style and an interest in eroticism, violence, and primitivism.

1930 – 1939: Civil War

Picasso's famous painting "Guernica" in 1937 depicted the horrors of the Spanish Civil War.

Post-1939: Picasso's Exploration of Oil Pastels

In 1949, Picasso collaborated with Henri Sennelier to create professional-grade oil pastels.

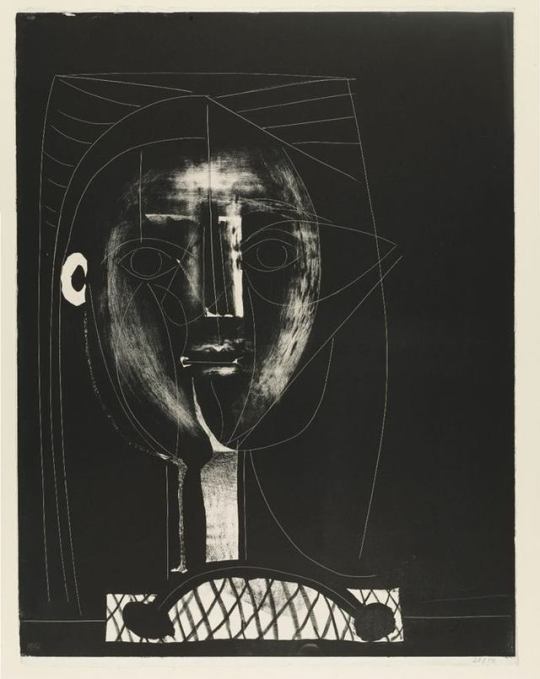

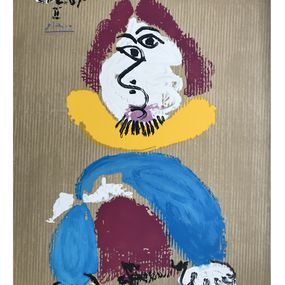

Notable Pastel Work: "Head of a Woman"

Picasso's "Head of a Woman" is a renowned pastel creation believed to be a study for his oil painting "Three Women."

Reference:

Grove Gallery. (n.d.). Pablo Picasso Periods: A Timeline. Retrieved from https://grovegallery.com/pablo-picasso-periods-a-timeline/

0 notes

Photo

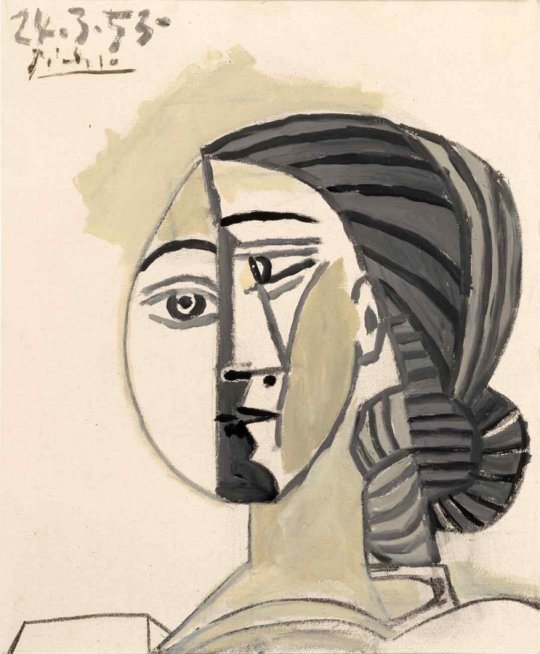

Pablo Picasso's 'Tête de femme,' Sells for $5.5 Million

Pablo Ruiz Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and theatre designer who spent most of his adult life in France. Regarded as one of the most influential artists of the 20th century, he is known for co-founding the Cubist movement, the invention of constructed sculpture, the co-invention of collage, and for the wide variety of styles that he helped develop and explore. Among his most famous works are the proto-Cubist Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907), and Guernica (1937), a dramatic portrayal of the bombing of Guernica by German and Italian air forces during the Spanish Civil War.

Picasso demonstrated extraordinary artistic talent in his early years, painting in a naturalistic manner through his childhood and adolescence. During the first decade of the 20th century, his style changed as he experimented with different theories, techniques, and ideas. After 1906, the Fauvist work of the slightly older artist Henri Matisse motivated Picasso to explore more radical styles, beginning a fruitful rivalry between the two artists, who subsequently were often paired by critics as the leaders of modern art.

Picasso's work is often categorized into periods. While the names of many of his later periods are debated, the most commonly accepted periods in his work are the Blue Period (1901–1904), the Rose Period (1904–1906), the African-influenced Period (1907–1909), Analytic Cubism (1909–1912), and Synthetic Cubism (1912–1919), also referred to as the Crystal period. Much of Picasso's work of the late 1910s and early 1920s is in a neoclassical style, and his work in the mid-1920s often has characteristics of Surrealism. His later work often combines elements of his earlier styles.

Exceptionally prolific throughout the course of his long life, Picasso achieved universal renown and immense fortune for his revolutionary artistic accomplishments, and became one of the best-known figures in 20th-century art.

#Pablo Picasso's 'Tête de femme' Sells for $5.5 Million#art#art work#art news#artist#Spanish Painter#sothebys#auction#painting

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

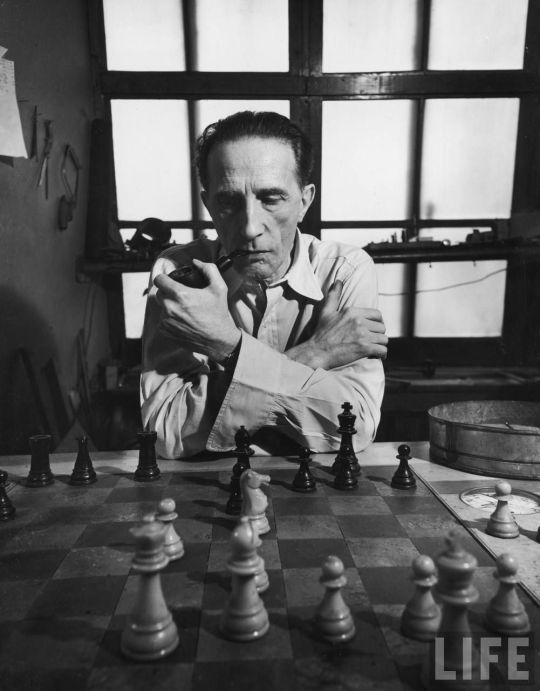

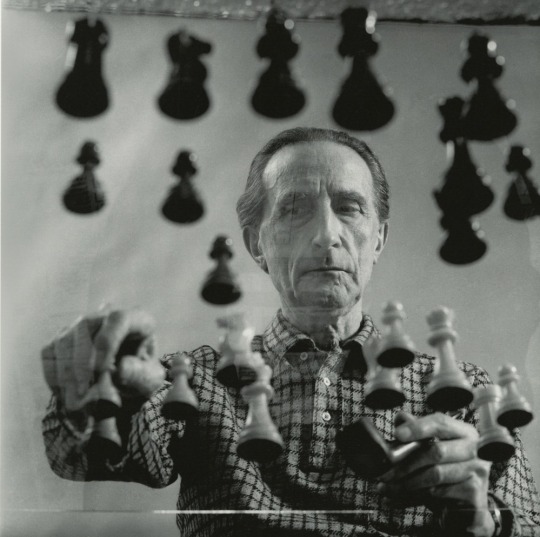

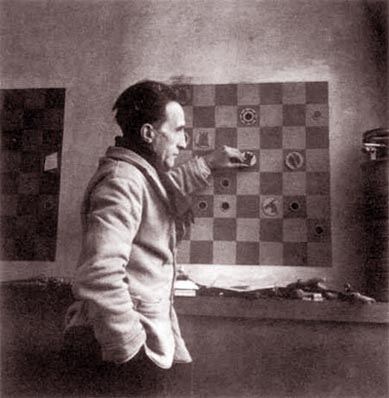

“…I HAVE COME TO THE PERSONAL CONCLUSION THAT WHILE ALL ARTISTS ARE NOT CHESS PLAYERS, ALL CHESS PLAYERS ARE ARTISTS.” MARCEL DUCHAMPBIOGRAPHY OF MARCEL DUCHAMP 1887-1968:Henri-Robert-Marcel Duchamp was born July 28, 1887, near Blainville, France.In 1904, he joined his artist brothers, Jacques Villon and Raymond Duchamp-Villon, in Paris, where he studied painting at the Academie Julian until 1905.Duchamps early works were Post-Impressionist in style. He exhibited for the first time in 1909 at the Salon des Independants and the Salon d’ Automne in Paris.His paintings of 1911 were directly related to Cubism but emphasized successive images of a single body in motion.In 1912, he painted the definitive version of Nude Descending a Staircase; this was shown at the Salon de la Section d’Or of that same year and subsequently created great controversy at the Armory Show in New York in 1913.Duchamps radical and iconoclastic ideas predated the founding of the Dada movement in Zurich in 1916.By 1913, he had abandoned traditional painting and drawing for various experimental forms, including mechanical drawings, studies, and notations that would be incorporated in a major work, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915-23; also known as The Large Glass).In 1914, Duchamp introduced his ready made common objects, sometimes altered, presented as works of art, which had a revolutionary impact upon many painters and sculptors.In 1915, Duchamp traveled to New York, where his circle included Katherine Dreier and Man Ray, with whom he founded the Societe Anonyme in 1920, as well as Louise and Walter Arensberg, Francis Picabia, and other avant-garde figures.After playing chess avidly for nine months in Buenos Aires, Duchamp returned to France in the summer of 1919 and associated with the Dada group in Paris.

In New York in 1920, he made his first motor-driven constructions and invented Rrose Slavy, his feminine alter ego.Duchamp moved back to Paris in 1923 and seemed to have abandoned art for chess but in fact continued his artistic experiments.From the mid-1930s, he collaborated with the Surrealists and participated in their exhibitions.Duchamp settled permanently in New York in 1942 and became a United States citizen in 1955.During the 1940s, he associated and exhibited with the Surrealist migrs in New York, and in 1946 began Etant donnes: 1. la chute d’eau 2. le gaz d’clairage, a major assemblage on which he worked secretly for the next 20 years.He died October 2, 1968, in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France.A PASSION FOR CHESS:Marcel Duchamp had a lifelong passion for chess.He once said “I am still a victim of chess. It has all the beauty of art – and much more. It cannot be commercialized. Chess is much purer than art in its social position.”March 1952, Duchamp had given up painting in favor of chess thirty years before.Marcel Duchamp played thousands of chess games, and he was known as a very strong Chess Master.Duchamp’s creativity had a significant impact in art. One wonders how chess influenced his way of thinking and his views about art and creativity.

Duchamp once said:“The chess pieces are the block alphabet which shapes thoughts; and these thoughts, although making a visual design on the chess-board, express their beauty abstractly, like a poem…. I have come to the personal conclusion that while all artists are not chess players, all chess players are artists.” Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), French artist, address, Aug. 30, 1952, New York State Chess Association.Duchamp was not only an avid chessplayer; he was also an active member of the chess community and made multiple contributions to chess, which will also made him a chess philanthropist.

THE MOVIE – PORTRAIT OF AN ARTIST: MARCEL DUCHAMP – A GAME OF CHESS (1963):This movie is an interview segment with the French artist. Filmed in black-and-white, this interview was held at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1963. Duchamp discusses his theories on the game of chess, his expatriate status in America, and his decision to stop working after 1923.Article is by Francis M. Naumann Fine Art, LLC

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exhibition Henri Matisse, le laboratoire intérieur

Throughout the artist’s life (1869-1954), drawing was a core discipline for Henri Matisse, for which he used a wide range of media (pencil, charcoal and stump, pen and ink, quill and brush ...) and supports (sheets from sketchpads, margins of letters, or fine art paper).

This continuous practice in the privacy of his studio was the laboratory for his work as a painter and for his sculpture – Matisse often compared himself to a juggler or an acrobat, daily maintaining the flexibility of his instrument of work. Matisse’s drawings surround, precede, accompany and extend other artistic forms in his oeuvre and also reveal themselves as independent constellations.

The exhibition illustrates the main moments in this artistic journey, arranged in fourteen thematic and chronological sequences: from the apprenticeship years at the very start of the 20th century, through to the studies for the chapel of the Rosary in Vence (1948-1949), the final masterpiece and culmination of an entire lifetime for Matisse. The suggested path identifies the pivotal points in Matisse’s approach to drawing – from the black of ink or pencil to the modulated white of paper, from the softness of smudged shadows to the light emanating from the final brush drawings, in relation to his experiments with colour in his painting or his work on volume in his sculptures. In the exhibition, each room offers a dialogue between drawings and paintings, etchings and sculptures, with works echoing each other and restoring something of the atmosphere of his various studios: Quai Saint Michel, in Paris from 1894, Issy-les-Moulineaux from 1909, Nice from 1918 until his death in 1954, with the exception of 1943-1948 which Matisse spent in Vence.

Learn. Unlearn

Henri Matisse is twenty-one years old when he goes to train in Paris. He attends evening classes at the École des Arts Décoratifs and at the École Nationale des beaux-arts, in particular in Gustave Moreau’s studio where he rubs shoulders with Albert Marquet and Georges Rouault. He was to stay there from 1892 to 1898, six years during which he works in the studio and assiduously visits the Louvre, where he copies the old masters, including Vermeer, Chardin and Raphaël. Copying gives him an occasional income until 1904, but is above all an essential exercise in the mastery of his craft. In addition to these figures from the past, he is hugely influenced by the great artists of his time, Paul Cézanne and Auguste Rodin, who help him formulate his own pictorial language. While Matisse had always assumed an artistic affinity with the old masters, in 1898 he casts off the weight of the past and escapes from it in all the genres he pursues: the self-portrait, landscapes from nature, or working from life with a model. In the early days, his work appears to be a long journey; he works from the major artists of the past and also with his contemporaries - he admires and challenges by copying, reworking and constantly questioning. And finally he unlearns from the masters.

The grammar of poses

In Matisse’s work, the period from 1904 to 1908 is generally associated with the advent of pure colour. During the summer of 1905, the artist worked in this direction, in the company of André Derain, at Collioure. It was in this mythical place that, under their impetus, fauvism was invented – a founding moment of modernity where colour ceases to bear any reference to local colour, where people and objects are indicated by signs, and where volumes and models are absorbed by the coloured surface. Thus, in La Japonaise: Woman beside the Water, colour and line, figure and decorative background become interchangeable, to the extent that they dissolve in a single movement. This apotheosis of colour is however intimately connected to drawing. These two skills feed the manifestly fauvist canvas The Joy of Life (1905-1906, Philadelphia, The Barnes Foundation), its genesis being evoked by a coloured landscape sketch and numerous drawings. The artist develops a repertoire of poses which he uses constantly throughout his oeuvre. In parallel to the paintings from this period, he also works on a group of three woodcuts, plus a set of small ink drawings. Here too, Matisse delves into his grammar of poses, exploring the ability of the black line to modulate the white surface and thereby give it a luminous, almost “coloured” quality.

A motionless dance

From 1906, Matisse concentrates more on the human figure and develops his creative process, alternating painting sessions with life drawing and sculptures. An overall logic unites these various media around the same conceptual approach to form. Pairs, or even series, can thus be organised around the major sculptures from this period. While Two Négresses reveals the artist’s attraction to African sculpture, they also reflect his interest in the theme of the back which he was to explore both in drawings and in paintings. It was again at the heart of the series of monumental sculptures, Back I, II and III, produced from 1909 to 1917 in step with the drawing-sculpture-painting chain focussing on this subject matter. Designed to be looked at from all angles, other sculptures from this period testify once again to Matisse’s interest in the plastic form of the back. This reflects – in Decorative Figure – a quest for monumentality and – with The Serpentine which was produced after The Dance I (New York, The Museum of Modern Art). In this continuity, a series of drawings is produced, centred on the theme of the issue of spatial expansion originating from the representation of a static figure - a motionless dance.

From portrait to face

Only late on does Matisse express his long-held interest in the “human face”. However, particularly between 1910 and 1917, he is encouraged by a group of fervent lovers of Byzantine art and disciples of philosopher Henri Bergson, who found the principles of a non-representative aesthetic in his art and sought to rethink the links between reality and perception. Matisse then embarks on a journey to develop and to get to the essential, reworking this specific theme in depth. In the portrait of Yvonne Landsberg, in 1914, in the drawing portraits of Eva Mudocci and Josette Gris in 1915, in that of Greta Prozor in 1916, or of George Besson in 1918, Matisse does not flinch from deconstructing and then recomposing his models’ faces, striping them right to the bone, producing unsettling works, often beyond the comprehension of their sponsors. He relies on the subtle use of different drawing methods, a practice he was subsequently to develop further and to theorise thirty years later, in his “Notes of a Painter on his Drawing”. Indeed, in the constellations of drawings and prints associated with the portraits from the period 1914-1916, a cinematography of snapshots already co-exists with a part of informed elaboration. It is thus in and by painting that Matisse finally accesses the spiritual truth of his models.

Trees and oranges

In the preface to the catalogue for the Matisse Picasso exhibition held at the Paul Guillaume gallery in Paris in 1918, Guillaume Apollinaire writes: “If one were to compare the work of Henri Matisse to something, one would have to choose an orange. Like an orange, Henri Matisse’s work is the fruit of dazzling light.” A recurring element which prevails, throughout his oeuvre, as a major subject in his compositions, orange is not a simple motif, which plastic possibilities Matisse explores: it is a real testing ground where the artist confronts the tensions in himself. Present in his early compositions, the fruit reappears during Matisse’s first visit to Morocco in 1912. The artist, in a difficult position due to the rise of cubism and futurism which call into question his role as leader of the avant-garde, will then seek to rethink his art in the light of the artistic tradition of this country. This experiment allows Matisse to set himself apart from the development of the avant-garde to better prepare himself to face it. During the winter of 1915, he travels to L’Estaque, in the footsteps of Paul Cézanne and Georges Braque. There, he abandons the motif of the orange, preferring instead that of the tree, its relationships between forms and forces allowing him to question the vocabulary of cubism. This subject was to occupy him again through force of circumstance : in this period of uncertainty marked by the First World War, active contemplation of nature offers Matisse the resources he needs to regain his equilibrium.

The life-drawing session

In late 1916, Matisse embarks on a new working method, a daily face-to-face, repeated for months and sometimes years, almost exclusively with one model, an Italian called Laurette. A professional model, paid by the hour, she poses for close to a year for around forty canvases, and particularly powerful charcoal drawings. Following the rupture marked by his move to Nice, where Matisse reconnects with the human figure, and during the whole of 1919, the young Antoinette Arnoud replaces Laurette. She inspires a remarkable series of drawings, sometimes worked in great detail, sometimes more elliptical, that Matisse decides to put together in an album published at his expense. Cinquante dessins par Henri-Matisse is objectively the first book composed by the artist, to the content and production of which he was completely committed. A demonstration of virtuosity, in an apparently classical mode, this album is however the contrary to a “return to order” – as Matisse’s period in Nice has often been described.

The odalisque form

Actress, musician and ballerina, Henriette Darricarrère becomes Matisse’s principal model from 1920 to 1927, her body alone incarnating the odalisque form. This word and this motif of odalisque, used by 18th and 19th century painters such as Boucher, Ingres and Delacroix, evoke the representation of nudes without sham mythologies, placed in an allusively oriental decor. In this tradition, Matisse inaugurates in 1921, with the Odalisque with Red Trousers (Paris, Musée national d’art moderne), a long series of works in which the odalisque is no longer a simple motif or an iconographic category, but a way of questioning the insertion of the figure in space. In his apartment, at 1, Place Charles Félix in Nice, Matisse even creates a bedroom like a theatre set, with a platform and decoration of fabrics and wall-hangings, to expose the nudity of the odalisque. Matisse examines the possible ways of achieving the tension of body and decor in various techniques – painting, sculpture, drawing and print – without establishing any hierarchy between them, but regarding them as joint methods of exploration. This series is part of the continuing personal quest of the Orient in relation to the decorative art, crystallised during this time of doubt and intense anguish, the Nice period, during which Matisse seeks to renew his approach by following the lessons of the old masters.

Metamorphoses. Nymph and satyr

Matisse develops the theme of the satyr charming a sleeping nymph, in parallel to that of dance, starting from his fauvist years with The Joy of Life (1905-1906). He reconnects with this motif in the illustration of “The afternoon of a satyr” for the Poems of Mallarmé published in 1932 by Albert Skira, which he creates in parallel to The Dance, a mural for the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia (United States). Between May and June 1935, he re-engages with this subject once again, producing a series of charcoal sketches, the chronology of which is difficult to ascertain, as Matisse changed and reworked them constantly. Starting from a fairly traditional iconography of the satyr, the artist then stylises this figure, neglecting his traditional attributes (horns and goat’s hooves), to focus on the expressive lines of the body. In these compositions, he was to discover the memory of the work he had started the previous year, on illustrations for James Joyce’s Ulysses, for which he turned to Homer’s Odyssey. These elements reappear in the canvas Nymph in the Forest (Greenery), started in 1935 and pursued tirelessly through to the early 1940’s. Its variations around a single motif and its constant metamorphoses testify to the Matisse’s creative process, who stated: “At each stage, I have a balance, a conclusion. In the next session, if I find that there is a weakness in the entire work, I re-enter myself to my painting via this weakness – I enter via the breach – and I redesign the whole thing.”

The artist and his model, Lydia

A young Russian recently arrived in Nice, Lydia Delectorskaya is initially employed by Matisse as a studio assistant in 1930, while he is working on The Dance for the Barnes Foundation. Although she sits for the artist once in 1934, she really only becomes his model in the following year. In The Dream, he shows her in what is to be his favourite pose, her head resting on her crossed arms surrendered to the gaze. This canvas is Lydia’s inauguration into Matisse’s painting, to which she was to be intimately bound for the rest of his life. In the same period, he develops a series of enormously sensual line life drawings of her, in which he returns to the theme of the “painter and his model” and develops the deconstruction approaches started at the beginning of the century. The presence of a mirror in the composition allows the reflection of the model and the hints of the artist’s presence to be mixed in a continuum of lines, which he explores until 1937. It is at this time that Lydia poses again for a major canvas, Large Blue Dress and Mimosas, in which Matisse paints with relish the dress and the ruffles in a set of drawings seeking harmony between pose and facial expression.

The Romanian blouse

Matisse’s close relationship with textiles, culminating in the Romanian blouse series in 1936-1940, seems to have been triggered by his birth into a family of weavers, and confirmed by his path through life : Le Cateau-Cambrésis, Saint-Quentin, Bohain – all towns centred on bobbin lace factories , wool and textile mills. When he arrives in Paris in 1891, he starts to collect fabrics, wall-hangings and rugs – which would feed and support his artistic creation. In parallel, he builds up a wardrobe for his models, one which grows throughout the 1930’s, containing numerous Romanian blouses, which become a favourite element in his graphic vocabulary. His long-held interest in this item of clothing seems to have grown from his contact with Theodor Pallady, a Romanian painter and former studio comrade of Gustave Moreau, but also from the presence of Lydia Delectorskaya, a young woman originally from Russia, who was to become his favourite model. During this period in which Matisse was seeking a simpler structural method, the graphical aspect of the Romanian blouse allows him to explore a work of purification, down to the expression of simple signs, capturing the character of his subject in the most succinct way. The culmination of Matisse’s interest in textiles, the “ Romanian blouses ” series, also occurs at the time when he embarks on a more general reflection on the decorative, starting from the study of specific motifs.

Cinematography. Themes and variations

In 1941 and 1942, Matisse concentrates on drawing. And he produces hundreds, a “flowering”, as he was to say, comprising series in which the initial drawing is a charcoal study of the developed motif. Other sheets of paper then evolve from this work, as if traced by a blind man, in a state of extreme concentration: “drawings in pen or pencil are like the perfumes emanating from this first master drawing.” He was to return to this approach, referring to “a cinematography of the feelings of an artist. A series of successive images resulting from the work on a given theme by the creator.” Matisse wanted to show this culmination, reconciling the two methods of drawing in a book, Themes and variations. The preface, written by Louis Aragon, is the fruit of an intense dialogue between the painter and the writer. Started in autumn 1941, continued in spring 1942, in the darkest days of the war, this dialogue was to go on in a regular correspondence and discussion, commented by Aragon in Henri Matisse roman, published in 1971. Interiors in Vence. Colours, black and white The season of Interiors in Vence, the final “flowering” of Matisse’s painting, starts in the spring of 1946 and ends two years later with Large Red Interior. This canvas sums up this dazzling series and makes reference to the Red Studio from 1911 (New York, The Museum of Modern Art). A double series in fact, in which strongly coloured canvases are accompanied by large brush-and-ink drawings, with the same motifs: interior (studio) / exterior (garden), nudes, ferns or pomegranates, and always palm trees. Palm trees fill the windows of villa Le Rêve in Vence, into which Matisse settles in June 1943, following the threat of the German occupation of his apartment and studio at the Hotel Régina and afteran air raid at Cimiez. Between painting and drawing, Matisse plays masterfully with black and colour, line and mark, the light of white and that of black. The entire series, exhibited in 1949 is received with great public acclaim, first in New York at his son Pierre Matisse’s gallery, then in Paris at the Musée National d’Art Moderne.

From face to mask

After Louis Aragon, Matisse subjects the faces of his grandchildren to the process of “Themes and variations”. Both adolescents, Claude Duthuit and Jackie Matisse meet their grandfather once again after the separation during the war, in 1945 and 1947 respectively. He drew studies of them in charcoal, extensively worked, followed by quick variations in line, arising from successive sensations and transcribed immediately, as well as simplified “faces”, still portraits yet already masks. They all need to be viewed in relation to these words by Matisse: “The face doesn’t lie: it is the mirror of the heart.”

Vence Chapel. Colour and light

The Vence Chapel of the Rosary project arose from Matisse’s meeting with Monique Bourgeois, a young nurse who cared for him following a major operation in 1941, before becoming his confidante and model. Having joined the order of the Dominicans of Vence in 1946, she tells Matisse in the following year of her plan to extend the chapel of their congregation. With the assistance of Brother Rayssiguier and Father Couturier, the artist produces an initial drawing which is approved by architects Auguste Perret and Louis Milon de Peillon. From 1948 to 1951, Matisse also designs the stained glass windows and the ceramic panels opposite them, as well as the liturgical ornaments. The Vence chapel project allows Matisse to design a space in its entirety and to produce a pictorial language which is a synthesis of his work. As the artist expressed it : “In the chapel, my main aim was to balance a surface of light and colour with a solid wall, with a black on white drawing. This chapel was for me the culmination of a whole lifetime’s work for which I was chosen by destiny at the end of my road, which I continue by my research, with the chapel giving me the opportunity to define it by uniting it.” As a whole, the various preparatory studies for the ceramic panels, stained glass windows and the door of the confessional testify to the long process resulting in Matisse’s final monumental project.

Henri Matisse and Lyon

In January 1941, Matisse’s health deteriorates and he is rushed to hospital, initially the Clinique Saint-Antoine in Nice, from where he is subsequently transferred to the Clinique du Parc in Lyon. There, in 1941, he undergoes an operation for duodenal cancer, carried out by Professor Santy assisted by Professors Wertheimer and Leriche. Matisse “miraculously” recovers from this procedure. He leaves hospital in April and convalesces at the Grand Nouvel Hôtel, rue Grolée in Lyon, before returning to Nice in May. During this period, he has many talks with art critic Pierre Courthion, about Lyon, a “city through and through” which is described as “consistent”. It is at this time that René Jullian, the director of the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyon, approaches Matisse in order to acquire one of his works. In 1943, the artist sends the museum a copy of his book Themes and Variations, accompanied by a series of six original drawings produced for the book. From this time until 1950, Matisse sends his illustrated works to the museum, including the album Jazz, each bearing an inscription to the Musée de Lyon. The culmination of this relationship was the purchase, after lengthy negotiations, by Jullian in 1947, of a painting by Matisse: the portrait of the Antiquarian Georges-Joseph Demotte. This collection of Matisse’s works at the museum was to grow further in 1993 by the addition of Young Woman in White, Red Background, from the Centre Pompidou to which it had been gifted by the artist’s son Pierre Matisse.

~ From 2 December 2016 to 6 March 2017.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

MWW Artist of the Day (9/29/19) Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (German, 1884–1976) The Miraculous Draught of Fishes (Petri Fischzug)(1918) Woodcut, 39.5 x 49.7 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff was one of the most important progenitors of German Expressionism. During his career as a painter and printmaker, Schmidt-Rottluff made more than six hundred printed images in woodcut, lithography, and etching. The woodcut technique dominated Schmidt-Rottluff's printed work from approximately 1909 to 1920. By 1911 he had moved to Berlin, where, increasingly exposed to Cubism and African and Oceanic art, his work grew more abstract, with angular lines and flattened shapes. In 1915 he was conscripted into the army and served for three years in Russia and Lithuania before returning to Berlin in 1918. These prints were made during the war years when, traumatized by the brutality he witnessed, Schmidt-Rottluff suffered such extreme anxiety that he was unable to paint and devoted himself to the more therapeutic practice of carving woodblocks and wooden sculpture. Between 1917 and 1919, he devoted himself primarily to religious subjects, including this "Miraculous Draught of Fishes," taken from a portfolio of woodcuts depicting scenes from the life of Christ. (from the MoMA catalog)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

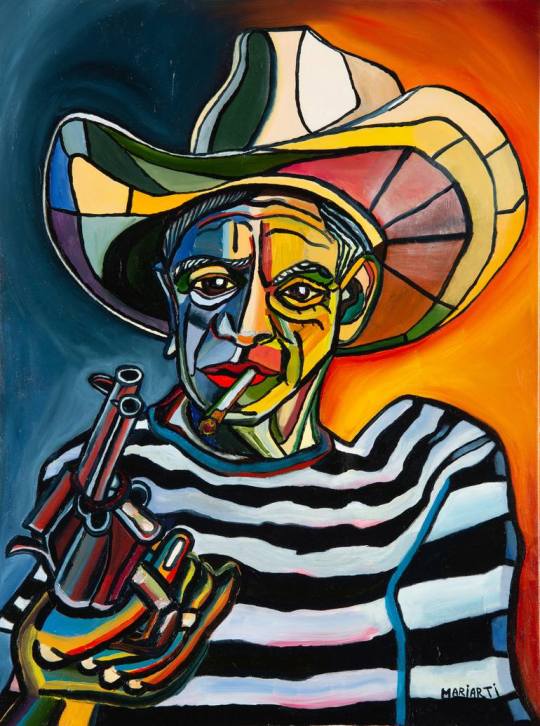

Pablo Ruiz Picasso Spanish Painter, Sculptor via /#bestofcanvas

Pablo Ruiz Picasso Spanish Painter, Sculptor

Pablo Ruiz Picasso 25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist, stage designer, poet and playwright who spent most of his adult life in France. Regarded as one of the most influential artists of the 20th century, he is known for co-founding the Cubist movement, the invention of constructed sculpture,the co-invention of collage, and for the wide variety of styles that he helped develop and explore. Among his most famous works are the proto-Cubist Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907), and Guernica(1937), a dramatic portrayal of the bombing of Guernica by the German and Italian airforces during the Spanish Civil War.

Picasso demonstrated extraordinary artistic talent in his early years, painting in a naturalistic manner through his childhood and adolescence. During the first decade of the 20th century, his style changed as he experimented with different theories, techniques, and ideas. After 1906, the Fauvist work of the slightly older artist Henri Matisse motivated Picasso to explore more radical styles, beginning a fruitful rivalry between the two artists, who subsequently were often paired by critics as the leaders of modern art.

Picasso's work is often categorized into periods. While the names of many of his later periods are debated, the most commonly accepted periods in his work are the Blue Period (1901–1904), the Rose Period (1904–1906), the African-influenced Period (1907–1909), Analytic Cubism (1909–1912), and Synthetic Cubism (1912–1919), also referred to as the Crystal period. Much of Picasso's work of the late 1910s and early 1920s is in a neoclassical style, and his work in the mid-1920s often has characteristics of Surrealism. His later work often combines elements of his earlier styles.

Exceptionally prolific throughout the course of his long life, Picasso achieved universal renown and immense fortune for his revolutionary artistic accomplishments and became one of the best-known figures in 20th-century art.

Source

Submitted August 14, 2019 at 04:23PM via #bestofcanvas https://www.reddit.com/r/u_HoustonCanvas/comments/cqg5ch/pablo_ruiz_picasso_spanish_painter_sculptor/?utm_source=ifttt

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

First Art Works: Guernica

The art piece I was assigned was Guernica by Pablo Picasso, which debuted in 1937.

1. This piece is one of Picasso's best-known works, and many still believe it was the most compelling and influential anti-war painting ever created.

2. Picasso painted Guernica as a commentary on the Bombing of Guernica on April 26, 1937. Guernica was a Basque Country town in the northern region of Spain, bombed by the Nazis and Italian Fascists.

3. The painting was shown at the Spanish display in the Parish International Exposition that year, along with other locations globally, bringing awareness to the Spanish Civil War.

4. Picasso's works are broken into periods. His most famous periods are the Blue Periods (1901-1904), the Rose Period (1904-1906), the African-Influenced Period (1907-1909), the Analytic Cubism Period period (1909-1912), and the Crystal period (1912-1919).

5. Pablo Picasso was usually referred to by his last name, because his full name is 25 words long.

At first glance, the first thought I had about this painting was anguish, and as I took more time to dissect the piece, I realized it was more than that. This work is not just anguish but the loss of hope due to miserable chaos. At first, this painting is just shapes, but the longer you stare, the more you see. What stuck out to me was the man at the bottom with a broken sword in his grasp, representing that same loss of hope I previously discussed. Overall, this is a beautiful painting that creates a picture of the ugliness of Mankind.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Kurt Schwitters ** available online , not my words **

Kurt Schwitters performs Ursonate in London, 1944.BornJune 20, 1887

Hanover, GermanyDiedJanuary 8, 1948 (aged 60)

Kendal, Cumbria, EnglandWebUbuWeb Sound, UbuWeb, Dada Companion, WikipediaCollectionsMoMA

Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948) was a painter, sculptor, designer and writer and worked in several genres and media, including Dada, Constructivism, Surrealism, poetry, sound, painting, sculpture, graphic design, typography, and what came to be known as installation art. Between 1923-32, Schwitters edited the magazine Merz.

Kurt Hermann Eduard Karl Julius Schwitters was born into a well-off family of shopkeepers in the provincial bourgeois city of Hannover. He began studying art at the School of Applied Arts in Hannover in 1908, and from 1909 to 1914 attended the Dresden Art Academy, where he studied traditional oil painting techniques and produced numerous landscapes, portraits, and still lifes. Although Schwitters would become known for his innovative experiments with new media like collage, assemblage, and installation art, he continued to paint traditional pictures throughout his life, often to earn money.

When war broke out, Schwitters returned to Hannover. Drafted, he was then declared unfit for active duty in 1917 when, according to his account, he pretended to be stupid and then bribed an army doctor. He was assigned to perform auxiliary military service, first as a clerical office worker, and then as a mechanical draftsman at an ironworks outside Hannover. He continued to work on his painting and began to write poetry, both of which, though influenced by cubism and expressionism, were also indebted to the German romantic tradition. In 1918, through the Kestner Society, an organization founded in Hannover in 1916 to promote the exhibition and discussion of modern art, Schwitters made contact with Herwarth Walden, whose Sturm Gallery and magazine in Berlin were devoted to promoting expressionism. Schwitters showed two abstract paintings at a group show at Sturm Gallery in June 1918.

Over the winter of 1918-1919, Schwitters began making abstract assemblages and collages from materials he found or accumulated in his daily life--ration cards, string, paper doilies, newspaper fragments, streetcar tickets, and other bits of discarded refuse. Schwitters named his new pictures "Merz" after a fragment of the phrase "Kommerz-und Privatbank" that appeared in one of his first assemblages, and adopted the term to describe all of his artistic activities. Although influenced to make collages by Hans Arp, Schwitters' works far surpass Arp's in the sheer variety of stuff incorporated, borrowing the language and strategies of commercial culture in order to reevaluate the relationship between art and everyday life.

In July 1919 Schwitters first exhibited the Merz pictures at Sturm Gallery and published a programmatic statement on Merz painting in Der Sturm magazine. His affiliation with Sturm and the active adoption of his own brand name kept Schwitters from being accepted into the inner circle of Berlin dadaists, though he became good friends with Raoul Hausmann and Hannah Höch. He tirelessly promoted Merz, popularizing his poem, An Anna Blume by pasting it up in the streets of Hannover as a poster, and then publishing it in Der Sturm and as a separate edition. Anna Blume became a renowned figure. Schwitters included her character in other short stories and poems, and capitalized on her popularity to advertise Merz as the recognizable brand name of Hannover Dada.

In 1923 Schwitters launched Merz magazine. The first issue was devoted to the De Stijl-Dada tour that Schwitters organized with Theo van Doesburg, and subsequent issues featured contributions from Höch, Arp, and Tristan Tzara. In addition to being a medium for the exchange of ideas between dadaists, Merz also functioned as a juncture between Dada and international constructivism, as in the 1924 collaboration between Schwitters and El Lissitzky on Merz 8-9, "Nasci"; Schwitters also used the magazine to further promote his poetry, which had developed after 1921 from parodies of expressionist sentimental lyrics like An Anna Blume to abstract sound poetry. In 1932 he published his most famous sound poem, the Ursonate, as a 29-page special issue of Merz. Remarkably, he also recorded his performance of the Ursonate, which gains much of its appeal from his inimitable delivery.

One of Schwitters' goals with Merz was the achievement of a Gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art that would encompass painting, poetry, sculpture, theater, and architecture. Around 1923, he began work on the construction of what would become his Merzbau, an installation in his home in Hannover (formerly the 19th-century home of his parents) that gradually took over his studio and encroached onto the other rooms of the house. Constructed of a series of grottoes that Schwitters filled with borrowed and stolen objects from friends and family and then covered over with further construction, the Merzbau became a lifelong project of accumulation and memorialization.

In 1937, after his works were confiscated from German museums and shown in Entartete Kunst, the "Degenerate Art" exhibition, Schwitters emigrated to Norway, where he began a new Merzbau project. He remained in Norway until 1940 when the German invasion forced him to flee to England. After a 17-month internment on the Isle of Man, he moved to the English countryside, where he continued to make collages and assemblages. In 1943 Allied bombs hit Schwitters' house in Hannover, destroying the Merzbau. Shortly before he died, he began work on a new Merz construction in a barn near his home in England supported by a grant from the Museum of Modern Art in New York. (Source)

About Monoskop

0 notes

Text

PABLO PICASSO

Pablo Picasso is probably one of the most important artists of modern times. His impact on art in the 20th century is outstanding. By the age of 50 Picasso had accomplished more, than any other well known artist of the time, developed distinct styles and was extremely creative. There had never been a more influential artist up to this time than the Spanish born artist. Picasso was born October 25th, 1881 and died on April 8th, 1973.

Picasso produced tens of thousands of paintings, drawings, sculptures and ceramics, including theatre sets and costume design. He was bound to be recognized as the most important artist of the 20th century. Pablo Picasso was significantly involved in many modern art movements, from painting in a neoclassical style late in his life, to contributing in the development, along with George Braque of cubism.

He is known for changing his style more than any other artist. Picasso also used multiple mediums, such as metal sculpture, ceramics, collage, and had different periods of expression.

Picasso during his younger years was in his “Blue Period” (1901-1904). The Blue Period was a time of struggle, poverty, loss and depression. His work is deep, sad and can appear gloomy.

The Blue Period was followed by the Rose Period, (1904-1906). His work took on a happier look when it came to colours reds, pinks and yellows. Picasso was in love, was starting to have success and recognition. His artwork appeared more cheerful.

Next Picasso discovered African sculpture, this is called his Primitivism Period (1907-1909). Picasso loved African sculpture so much he had collected approximately 100 pieces over the years. During his Primitivism Period he began to experiment with the planes of faces and the flatting of figures, taking inspiration from African masks. Picasso was recognized for his new ideas, leading into cubism.

Cubism (1909-1919), is the process of deconstructing perspective. Using mostly neutral colours, Picasso and Braque took apart the item and analyzed it’s shape. Changing the form of the subject they were painting. Cubism grew to be especially radical in the form called Synthetic Cubism. Here the technique of collage was added into the art piece, using newspapers and tobacco wrappers to express a texture or feel in combination with paint, thus introducing the new art form of collage. This addition of collage was opening up ideas of the question of reality, and was there illusion coming forth from the painting. This changed the direction of art forever.

As a young man Picasso studied art, as all students do, in a classical manner. He studied masters like Raphael, learning the proper approach to painting and drawing, and Picasso mastered his lessons. In Picasso’s later years he returned and re-examined classical art. Painting a variety of old masters, copying work like Rembrandt, Manet and Goya. Some of the artworks painted in his later years are credited with inspiring the beginning of the Neo Expressionism movement. Once again Picasso had influenced modern art, changing the art world forever.

When Pablo Picasso dies at 91, in1973, he had been one of the most famous and successful artists in history. He is seen as the most prolific artist in history. His genius, 78 years of producing 13,500 paintings, 100,000 prints and engravings and, 34,000 illustrations. Not to mention his sculptures, murals, and ceramics.

Picasso’s impact on modern art is profound. He will forever be remembered in history like Shakespeare is to writing and DaVinci is to the Renaissance. Picasso is influencing artists today and will continue to into the future. I have only touched on some of his life and contributions, I encourage you to read and learn more about Picasso. Picasso has always been a favourite of mine. When I was studying art at university, one of my master copies was a Picasso and hangs in my living room. I have always admired his constant changing expression. I approach my art with the idea of change and experimentation as growth. I love trying new things from drawing, collage to oil painting in a classical style. For me Picasso is a constant inspiration. I will close with a quote I like of Picasso’

“Others have seen what is and ask why? I have seen what could be and ask why not?

Sources: Picasso, Creator and Destroyer, by Arianna Huffington, Published 1988

Rubens to Picasso, Four Centuries of Master Drawings,

by Victor Chan, Published 1995

France, A History In Art, by Bradley Smith, Published 198

https://www.pablopicasso.org/

0 notes

Text

Pablo Picasso

Picasso was born into a middle-class background in Malaga, Spain in 1881. His father, Don Jose Ruiz y Blasco, was also a painter, specializing in natural depictions of birds, and was a professor of art at the School of Crafts as well as a curator at a local museum. Picasso received formal traditional training from his father from a young age, with a focus on figure drawing and oil painting. Following the death of his younger sister, Conchita, at seven year old the family moved to Barcelona in 1985 where Picasso was received early admission to the School of Fine Arts at only 13 years old. At 16, Picasso attend Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, the country’s leading art school in Madrid. In the early 1900’s Picasso visited Paris, the art epicenter of the time, where he eventually settled in 1904. Picasso’s work spanned over serval artistic movements, however, he is primarily known as a Cubist painter. Picasso lived through World War I, World War II and the Spanish Civil War, however, never enrolled to fight and remained a painter throughout these times. Picasso was politically a communist.

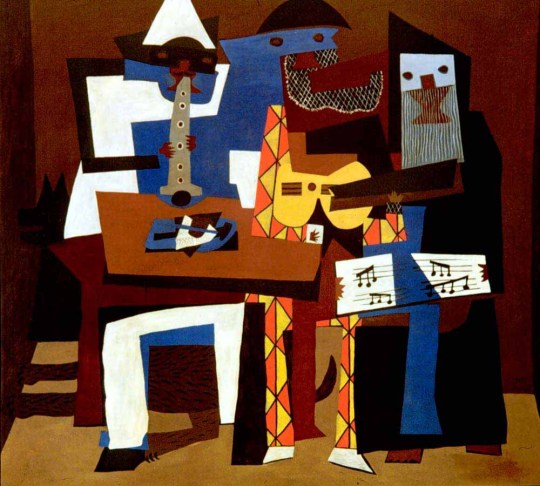

Picassos was primarily a painter and his vast body of work spans many years and is subsequently broken down into different periods of his life. The Blue Period (1901 – 1904) showed somber paintings rendered in only shades of blue and green. The paintings often depicted gaunt women with their children. Some of the key pieces from the this time included; The Frugal Repast (1904), the Blind Man’s Meal (1903) and Celestina (1903). The Rose Period (1904 – 1906) is exemplified by use of lighter tones, primarily oranges and pinks, featuring; circus performers, acrobats, and harlequins. A key piece from this is Portrait of Gerturde Stein (1906). African art and primitivism (1907 – 1909) was where Picasso really started to explore abstraction, most notably with the piece Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). From here Picasso really started to explore Cubism, the style in which he is most prolifically known, starting with Analytic Cubism (1909 – 1912). During this period Picasso analytically studied objects and simplified the studies into shapes. Synthetic Cubism (1912 – 1919) began the exploration of paper fragments and the first use of collage in fine art. Picasso’s work grew to be more minimalist and abstract throughout this period with a focus on breaking away from Renaissance tradition to focus on the use of perspective and illusion. Picasso’s paintings, like the Cubist’s of his time, use colour as a form of expression and explore the subtilties of colour to create from and space. Although Picasso’s Cubist works explores the abstract, he sought to base his paintings on real life subject matter rather than the imagination; however, painting mostly from memory. A key piece from this time is Three Musicians.

0 notes

Photo

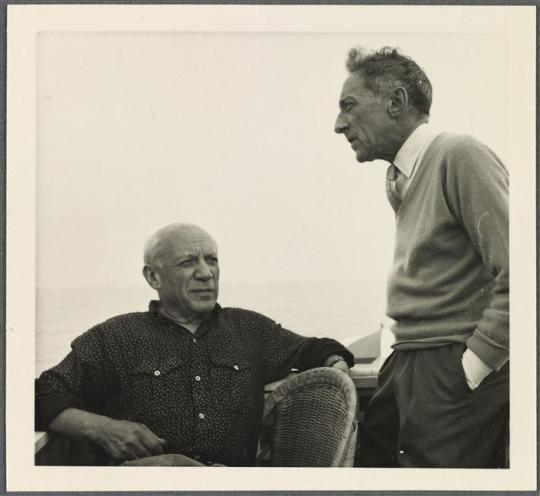

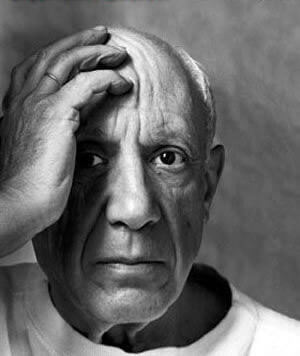

Arrivals & Departures 25 October 1881 – 08 April 1973 Pablo Ruiz Picasso

Pablo Ruiz Picasso was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and theatre designer who spent most of his adult life in France. Regarded as one of the most influential artists of the 20th century, he is known for co-founding the Cubist movement, the invention of constructed sculpture, the co-invention of collage, and for the wide variety of styles that he helped develop and explore. Among his most famous works are the proto-Cubist Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907), and Guernica (1937), a dramatic portrayal of the bombing of Guernica by German and Italian air forces during the Spanish Civil War.

Picasso demonstrated extraordinary artistic talent in his early years, painting in a naturalistic manner through his childhood and adolescence. During the first decade of the 20th century, his style changed as he experimented with different theories, techniques, and ideas. After 1906, the Fauvist work of the slightly older artist Henri Matisse motivated Picasso to explore more radical styles, beginning a fruitful rivalry between the two artists, who subsequently were often paired by critics as the leaders of modern art.

Picasso's work is often categorized into periods. While the names of many of his later periods are debated, the most commonly accepted periods in his work are the Blue Period (1901–1904), the Rose Period (1904–1906), the African-influenced Period (1907–1909), Analytic Cubism (1909–1912), and Synthetic Cubism (1912–1919), also referred to as the Crystal period. Much of Picasso's work of the late 1910s and early 1920s is in a neoclassical style, and his work in the mid-1920s often has characteristics of Surrealism. His later work often combines elements of his earlier styles.

Exceptionally prolific throughout the course of his long life, Picasso achieved universal renown and immense fortune for his revolutionary artistic accomplishments, and became one of the best-known figures in 20th-century art.

0 notes

Photo

Marcel Duchamp asleep on the toilet, 1915. Marcel Duchamp, (born July 28, 1887, Blainville, Fr.—died Oct. 2, 1968, Neuilly), French artist who broke down the boundaries between works of art and everyday objects. After the sensation caused by “Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2” (1912), he painted few other pictures. His irreverence for conventional aesthetic standards led him to devise his famous ready-mades and heralded an artistic revolution. Duchamp was friendly with the Dadaists, and in the 1930s he helped to organize Surrealist exhibitions. He became a U.S. citizen in 1955. Although Duchamp’s father was a notary the family had an artistic tradition stemming from his grandfather, a shipping agent who practiced engraving seriously. Four of the six Duchamp children became artists. Gaston, born in 1875, was later known as Jacques Villon, and Raymond, born in 1876, called himself Duchamp-Villon. Marcel, the youngest of the boys, and his sister Suzanne, born in 1889, both kept the name Duchamp as artists. When Marcel arrived in Paris in October 1904, his two elder brothers were already in a position to help him. He had done some painting at home, and his “Portrait of Marcel Lefrançois” shows him already in possession of a style and of a technique. During the next few years, while drawing cartoons for comic magazines, Duchamp passed rapidly through the main contemporary trends in painting—Postimpressionism, the influence of Paul Cézanne, Fauvism, and finally Cubism. He was merely experimenting, seeing no virtue in making a habit of any one style. He was outside artistic tradition not only in shunning repetition but also in not attempting a prolific output or frequent exhibition of his work. In the Fauvist style Marcel painted some of his best early work three or four years after the Fauvist movement itself had died away. The “Portrait of the Artist’s Father” is a notable example. Only in 1911 did he begin to paint in a manner that showed a trace of Cubism. He had then become a friend of the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, a strong supporter of Cubism and of everything avant-garde in the arts. Another of his close friends was Francis Picabia, himself a painter in the most orthodox style of Impressionism until 1909, when he felt the need of complete change. Duchamp shared with him the feeling that Cubism was too systematic, too static and “boring.” They both passed directly from “semirealism” to a “nonobjective” expression of movement. There they met “Futurism” and “Abstractionism,” which they had known before only by name. The “Nude.” To an exhibition in 1911 Duchamp sent a “Portrait” that was composed of a series of five almost monochromatic, superimposed silhouettes. In this juxtaposition of successive phases of the movement of a single body appears the idea for the “Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2.” The main difference between the two works is that in the earlier one the kangaroo-like silhouettes can be distinguished. In the “Nude,” on the other hand, there is no nude at all but only a descending machine, a nonobjective and virtually cinematic effect that was entirely new in painting. When the “Nude” was brought to the 28th Salon des Indépendants in February 1912, the committee, composed of friends of the Duchamp family, refused to hang the painting. These men were not reactionaries and were well accustomed to Cubism, yet they were unable to accept the novel vision. A year later at the Armory Show in New York City, the painting again was singled out from among hundreds that were equally shocking to the public. Whatever it was that made the work so scandalous in Paris, and in New York so tremendous a success, prompted Duchamp to stop painting at the age of 25. A widely held belief is that Duchamp introduced in his work a dimension of irony, almost a mockery of painting itself, that was more than anyone could bear and that undermined his own belief in painting. The title alone was a joke that was resented. Even the Cubists did their best to flatter the eye, but Duchamp’s only motive seemed to be provocation. There was no question that as a painter Duchamp was on a footing with the most gifted. What he lacked was faith in art itself, and he sought to replace aesthetic values in his new world with an aggressive intellectualism opposed to the so-called common-sense world. As early as 1913 he began studies for an utterly awkward piece: “The Large Glass, or The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even.” For it, he repudiated entirely what he called retinal art and adopted the geometrical methods of industrial design. It became like the blueprint of a machine, albeit a symbolic one, that embodied his ideas of man, woman, and love. Like the “Nude,” “The Large Glass” was to be unique among works of modern painting. Between 1913 and 1923, Duchamp worked almost exclusively on the preliminary studies and the actual painting of the picture itself. His farewell to painting was by no means a farewell to work. During this period a stroke of genius led him to a discovery of great importance in contemporary art, the so-called ready-made. In 1913 he produced the “Bicycle Wheel,” which was simply an ordinary bicycle wheel. In 1914, “Pharmacy” consisted of a commercial print of a winter landscape, to which he added two small figures reminiscent of pharmacists’ bottles. It was nearly 40 years before the ready-mades were seen as more than a derisive gesture against the excessive importance attached to works of art, before their positive values were understood. With the ready-mades, contemporary art became in itself a mixture of creation and criticism. When World War I broke out, Duchamp, who was exempt from military service, was living and working in almost complete isolation. He left France for the United States, where he had made friends through the Armory Show. When he landed in New York in June 1915, he was welcomed by reporters as a famous man. His warm reception in intellectual circles as well raised his spirits. The wealthy poet and collector Walter Arensberg arranged a studio for him in his own home, where the painter immediately set to work on “The Large Glass.” He became the centre of the Arensberg group, enjoying a reputation that led to many offers from art galleries eager to handle the works of the painter of the “Nude.” He refused them all, however, not wanting to start a full-time career as a painter. To support himself, he gave French lessons. He was then, and remained, an artist whose works would have been sought after but who was content to distribute them free among his friends or to sell them for intentionally small amounts. He helped Arensberg buy back as many of his works as could be found, including the “Nude.” They became a feature of the Arensberg Collection, which was left to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Besides “The Large Glass,” on which he worked for eight more years until abandoning it in 1923, Duchamp did only a few more ready-mades. One, a urinal entitled “Fountain,” he sent to the first exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists, in 1917. Although he was a founder-member of this society, he had signed the work “R. Mutt,” and therefore it was refused. His ready-mades had anticipated by a few years the Dada movement, which Picabia introduced to New York City in the magazine 291 (1917). As an echo of the movement, Duchamp helped Arensberg and H.P. Roché to publish The Blind Man, which had only two issues, and Rongwrong, which had only one. Later, with the painter Man Ray, he published a single issue of New York Dada in 1921. In 1918 he sold “The Large Glass,” which was still unfinished, to Walter Arensberg. With the money from this and another painting, his last, he spent nine months in Buenos Aires, where he heard of the armistice and of the deaths of his brother Raymond Duchamp-Villon and of Guillaume Apollinaire. In Paris in 1919 he stayed with Picabia and established contact with the first Dada group. This was the occasion of his most famous ready-made, a photograph of the “Mona Lisa” with a moustache and a goatee added. The act expressed the Dadaists’ scorn for the art of the past, which in their eyes was part of the infamy of a civilization that had produced the horrors of the war just ended. In February 1923 Duchamp stopped working on “The Large Glass,” considering it definitely and permanently unfinished. As the years passed, art activity of any kind interested him less and less, but the cinema came to fulfill his pleasure in movement. His works to this point had been only potential machines, and it was time for him to create machines that were real, that worked and moved. The first ones were devoted to optics and led to a short film, Anemic Cinema (1926). With these and other products, including “optical phonograph records,” he acted as a kind of amateur engineer. The modesty of his results, however, was a way by which he could ridicule the ambitions of industry. The rest of the time he was absorbed in chess playing, even taking part in international tournaments and publishing a treatise on the subject in 1932. Although Duchamp carefully avoided art circles, he remained in contact with the Surrealist group in Paris, composed of many of his former Dadaist friends. When in 1934 he published the Green Box, containing a series of documents related to “The Large Glass,” the Surrealist poet André Breton perceived the importance of the painting and wrote the first comprehensive study of Duchamp, which appeared in the Paris magazine Minotaure in 1935. From that time on there was a closer association between the Surrealists and Duchamp, who helped Breton to organize all the Surrealist exhibitions from 1938 to 1959. Just before World War II he assembled his Boîte-en-valise, a suitcase containing 68 small-scale reproductions of his works. When the Nazis occupied France, he smuggled his material across the border in the course of several trips. Eventually he carried it to New York City, where he joined a number of the Surrealists in exile, including Breton, Max Ernst, and Yves Tanguy. He was instrumental in organizing the Surrealist exhibition in New York City in October and November of 1942. Unlike his co-exiles, he felt at home in America, where he had many friends. During the war, the exhibition of “The Large Glass” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York City, helped to revive his reputation, and a special issue of the art magazine View was devoted to him in 1945. Two years later he was back in Paris assisting Breton with a Surrealist exhibition, but he returned to New York City promptly and spent most of the remainder of his life there. After his marriage to Teeny Sattler in 1954, he lived more than ever in semiretirement, content with chess and with producing, as the spirit moved him, some strange and unexpected object. This contemplative life was interrupted in about 1960, when the rising generation of American artists realized that Duchamp had found answers for many of their problems. Suddenly tributes came to him from all over the world. Retrospective shows of his works were organized in America and Europe. Even more astonishing were the replicas of his ready-mades produced in limited editions with his permission, but the greatest surprise was still to come. After his death in Neuilly his friends heard that he had worked secretly for his last 20 years on a major piece called “Étant donnés: 1. la chute d’eau, 2. le gaz d’éclairage” (Given: 1. the waterfall, 2. the illuminating gas”). It is now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and offers through two small holes in a heavy wooden door a glimpse of Duchamp’s enigma. As artist and anti-artist, Marcel Duchamp is considered one of the leading spirits of 20th-century painting. With the exception of the “Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2,” however, his works were ignored by the public for the greater part of his life. Until 1960 only such avant-garde groups as the Surrealists claimed that he was important, while to “official” art circles and sophisticated critics he appeared to be merely an eccentric and something of a failure. He was more than 70 years old when he emerged in the United States as the secret master whose entirely new attitude toward art and society, far from being negative or nihilistic, had led the way to Pop art, Op art, and many of the other movements embraced by younger artists everywhere. Not only did he change the visual arts but he also changed the mind of the artist. Like MONA's Page: www.facebook.com/pages/Museum-of-New-Art/51957798982

3 notes

·

View notes