#Corsican pure blood

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

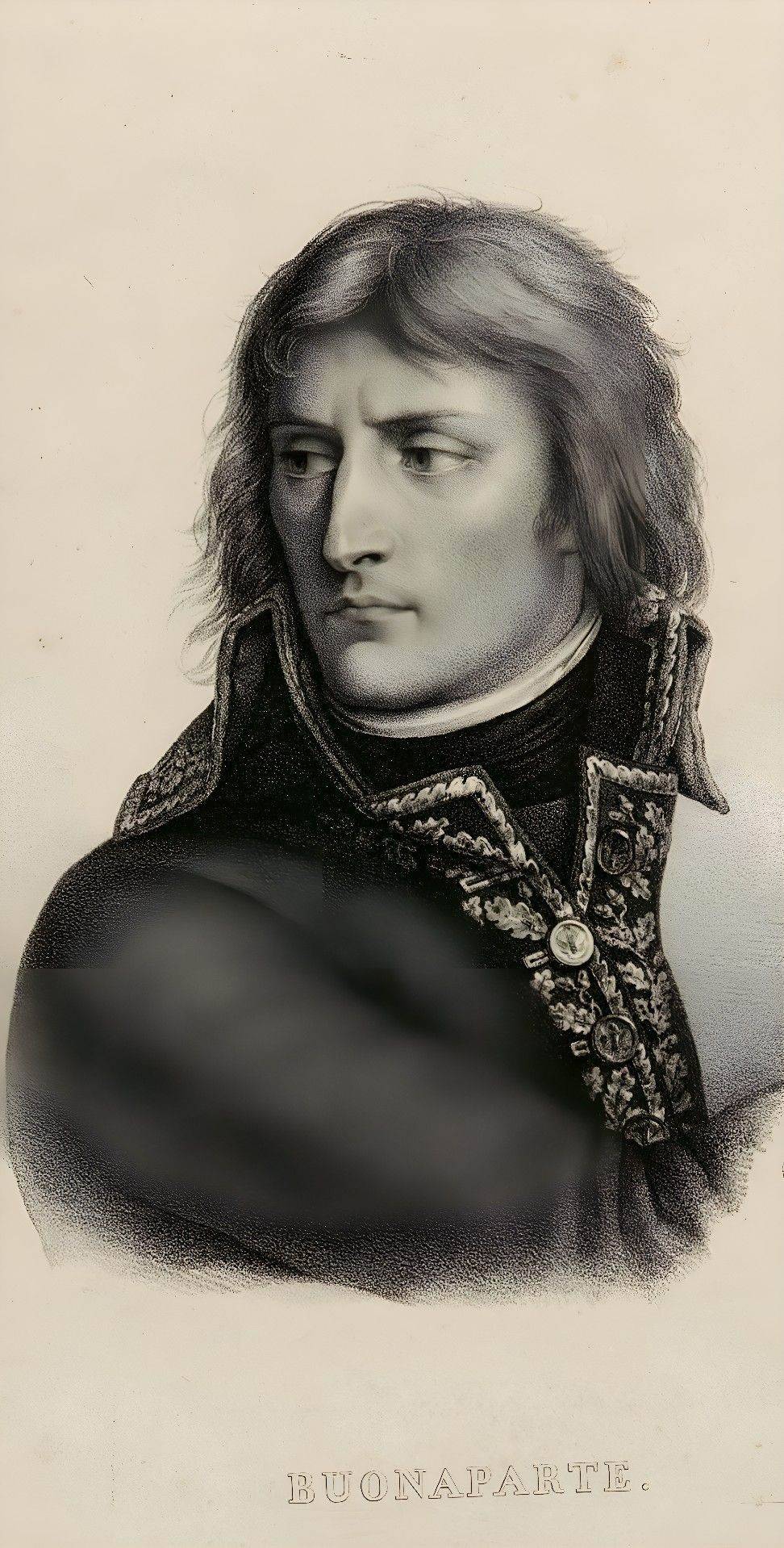

Napoleon Bonaparte... The rightful owner of all women's hearts!

#being napoleon#world history#the italian stallion#napoleon bonaparte#military#sexyboys#sexiest man in history#war lord#France#Empreor#Ultimate breed#Mars The Peacemaker#corsica#Corsican pure blood

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

&&. word has it ( izidora szarka ) was just spotted around the city. ( she ) is/are a ( 36 ) year old affiliated with ( corsican ). it’s been said that ( she ) resembles ( hayley atwell ). ( she ) has been said to be ( humorous & methodical ) but also quite ( cooked & uptight ). ( she ) is currently serving as ( bodyguard/interpol agent ). ( abby )

( izidora szarka ) would describe ( her ) as a ( winter ) person and would identify as a ( the facade/istj ). ( her ) birthday is ( may 20 ), making ( her ) star sign ( taurus ) and ( her ) animal sign the ( sea horse ). ( her ) biggest pet peeve is ( people without manners ), and ( her ) theme song is ( so it goes by marianas trench ). finally, ( her ) primary goal is to ( make it out of this conflict alive and with some sort of moral standing left ).

Bio

Born to a Hungarian-American academic and the Hungarian Science Attaché to Sweden. She grew up in Stockholm, used to switching between languages and public service. She wanted to be one of the “good guys” like her father, like the men who protected him.

Izi joined Sweden’s Interpol bureau right out of university. She was a very capable agent. Having grown up as a diplomatic’s child, she was well equipped to move from country to country, culture to culture.

When she was sent to France and ordered to infiltrate the Olivier family, all she felt for the family was disgust. They were criminals, plain and simple. But then she got the order that she was stuck there, she was perhaps, too good at her job.

As time went on she wanted, she began to actually become friends with some of the members of the ‘family’ much to her dismay. Then came the fateful day that she saved Damien Olivier. Izadora hardly knew what she was doing. It was pure reflex taking out that would be assassin and afterward, Izidora was somewhere between kicking herself and grateful to see Damien alive.

Her feelings towards Damien is somewhere between maternal and sororal and it hasn’t let up in the five years she’s been guarding him. The night that Izidora killed the Parrain was one of the darkest of her life. Not only had she killed a man in cold blood but she had given herself over to her feelings about Damien. She’d given her soul over to a criminal.

Her loyalty to Interpol is slipping, like she’s about to fall into an abbess and she’s only got one hand on the cliff’s ledge the other dripping with blood.

Fast Facts: -Cat mom -Speaks 7 languages -Has a Swedish accents -Calls her parents once a week -Is bi

Wanted Connections -Her contact in the NYPD -A lover in the mafia b/c that’s messy -friends b/c that’s also messy

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

IN DEFENSE OF THE DEATH OF ████████ , AND AN ARGUMENT AGAINST SUICIDE

This one’s for the manga readers! Post-volume 19 meta, spoilers aplenty! read at your own risk

Though the literal iteration of the death of Ash Lynx can be viewed as a purposeful shuffle from this mortal coil, a specific decision made with weight to return to the New york Public Library to live out his last moments dwelling on Eiji’s letter only to intentionally fade away, here stands a lonely argument; out of the entire cast, no one person deserves death in the same capacity more than Ash Lynx does, and his death is not a suicide. Let’s break it down.

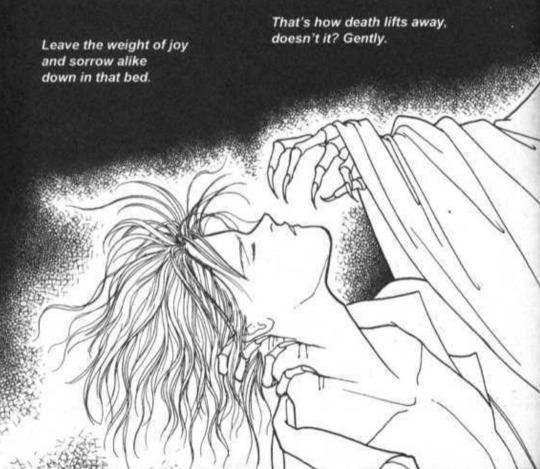

Out of all of the MANY problematic elements of Banana Fish, not even trying to hazard which offense is worse than the next, we can all simultaneously agree that one of the most heartbreaking twists of the series comes at the end of volume 19, when after receiving Eiji’s goodbye letter, which essentially amounts to an incredibly pure love declaration, Ash allows himself to be mentally distracted long enough for Sing’s brother Lao to deliver a killing stab to his intestines. Though Lao dies shortly after Ash’s retaliation, Ash continues to linger in a liminal place. The question hangs in the mind of the reader, if Ash approached a happy ending, why would he not seek hospitalization? Why would he allow himself to bleed out? The manga strikes back hard at the reader with a quite prolonged death sequence, in which Ash retreats to his favorite place to be alone, the New York Public Library, where, with a smile on his face, he falls into a peaceful sleep and dies at a reading table while clutching Eiji’s now bloody love letter. What is the nature of his mindset which dictates this course of action? Why, with Eiji hale and hearty, would Ash choose death instead of medical treatment and a possibly much happier ending to this tale of woe? At this point, I can only wonder if we, the readership, have read the same story. The ending of Banana Fish is hotly debated, and even though as a queer storyteller myself I fundamentally have trouble with gay death as a narrative element, I can’t help but question why people can’t empathize more with Ash’s decision. When judging the manga as a standing piece, I can’t think of a more satisfying, or simply more correct turn of events.

Directly out of the gate, Ash’s death is foreshadowed in the title of the series. A Perfect Day For Banana Fish is a short story by J.D. Salinger which follows the last day in the life of mentally ill World War 2 veteran Seymour Glass, who befriends a little girl while on vacation at the beach. He invites her to catch bananafish with him, and explains that the greedy fish enter holes to gorge themselves on bananas, but become too large to escape again and instead perish in the hole. Later, Seymour returns to his room where his wife is sleeping, and he kills himself. Salinger relates this as a metaphor for his own personal experience in the war, specifically to his time at the Battle of the Bulge and in Nazi concentration camps. He is quoted saying Seymour is an iteration of himself, and has gone so far as to say that he “found it impossible to fit into a society that ignored the truth that he now knew.” The point of the story has always been to examine the irreversible damage done to the human psyche by war. The Perfect Day referenced in the title is exactly that; the quest of a broken man lacking the power to overcome his trauma to find exactly the perfect day to die. So it also is with Ash, we understand from the very beginning that making this direct analogy to Salinger means the manga will be the slow disclosure of someone who is irrevocably damaged by their circumstance as they come to terms with the moment of their own death. From the very first panel you see him, Ash’s death is already fated, and truly the most heart-rending struggle of the series is watching him grapple with this identity, up to nearly the very last second. As a reader, we continuously keep hoping and praying that he might, against all odds, find salvation despite literally every piece of contrary evidence suggesting otherwise. We have violent affection for Ash as a hero, and we want him so badly to live on, to make it to the other side. He both finds salvation and doesn’t find it, because like everything else about this manga, Ash operates thematically on contradictory levels all the way through the story and on to the bitter end. Let’s break it down even further, by considering exactly just how fucked Ash really is.

Ash is born Aslan Jade Callenrese, and then quickly discarded. He briefly experiences a short period of normalcy with the love of his brother and distant father before Griffin is drafted. Almost immediately after, Ash is raped by the Bluebeard of Cape Cod and then blamed for it, and from then on, his life is a progression of non-stop horror. He is kidnapped by Marvin who repeatedly rapes him over a period of years. He is sold into sexual servitude at Club Cod. He somehow manages to avoid getting addicted to the opioids that all the child prostitutes were fed to keep them tame, and when Ash escapes, it is only because he is instead personally taken under Papa Dino’s wing, who specifically sexually abuses him while simultaneously not knowing or caring that Marvin continues to rape Ash, among presumably a handful of other people. Blanca is a small, bright focal point for Ash at age 13 when Ash lets himself briefly believe he has autonomy, and he is released to start his own gang. Ash’s fundamental humanity and inherent leadership magnetically draw people to him, and for the first time in his life, Ash briefly entertains the idea of having a private romantic relationship of his own. He is attracted to a girl he likes very much, but she is murdered almost immediately due to her association with him. He afterward throws himself into the business of his gang without ever fully extracting himself from Papa Dino’s hold. It is only with the discovery of the capsule containing Banana Fish that Ash for the first time in his short life discovers a bit of real leverage he can actually use against Dino. The subsequent drug war sees him beaten, sent to jail, raped many more times, and sent on a cross-country mission on the lam from the law, as well as from Dino’s goons, both Corsican and Chinese. Yut-Lung proves to be a worthy adversary in LA, and his teaming up with Arthur sees Ash murdering his best friend Shorter in cold blood who is forcibly high on banana fish in order to save Eiji from an especially savage disembowelment. Ash is later declared legally dead, sent to a private insane asylum to be experimented on, tortured with the mangled bits of Shorter’s brain, and then after escaping yet again, still forced into a corner when Dino tricks and threatens him into becoming officially adopted, once more in order to prevent Eiji’s death. Ash is drugged, literally blinded, beaten, and emotionally and physically torn down. He nearly dies from intentionally wasting away, and is hospitalized. When he eventually once again manages to escape, it is only to regroup long enough to prepare to engage with his men in actual guerrilla warfare. The mercenary Foxx kills nearly all of Ash’s remaining gang, and once AGAIN, Ash is raped. Ash is ultimately deprived of his revenge when he then has to witness Papa Dino’s death by the hand of someone other than himself. These are the major plot points, and don’t even touch on the myriad of lesser cruelties Ash has dealt with over the course of his short life, of which there are many, many more. (See: The death of most of his friends, that fucklord Arthur, everything about Cape Cod, the pain of using his sexual wiles as a weapon, the pain of knowing if he opens up to others that the lives of his friends will be in danger, the pain of being unable to give his loved ones proper burials, his one hundred issues with classism, his complete inability to trust others with important tasks, the list goes on.)

Around volume 10, I started, in a serious way, feeling like Ash deserved death. Not in the way that a dog is put out of it’s misery when it is sick, but more in the way that when the path is this hard, the reward at the end should be equivalent to the struggle. Being a CSA survivor all on its own demands a certain level of understanding, especially when approaching volatile, sensitive subjects like suicide. The act of taking one’s own life is so deeply personal and hotly debated that there is no true narrative argument legitimate enough to address it’s purpose. All of it is too subjective. However, in the case of Ash Lynx as the thematic hero, the case stands that he never, except for perhaps the small corridor between the ages of 0-7, lived a life anywhere remotely near average, so his many brushes with near-suicide are chillingly understandable. At one point, when forced to either shoot himself in the head or watch Eiji die, Ash even goes so far as to grab the gun and immediately try to blow his brains out. When the gun is proven empty, instead of breathing a secret sigh of relief, Ash only demands that Yut Lung give him a bullet.

Though this emphasizes Ash’s near fanatical devotion to protecting Eiji, whose innocence he both disdains and canonizes, it also represents his constant readiness to die. This flirtation with the reaper is emphasized over and over in the official art, where a sexual element is often present in his interactions with death. Ash wishes for death to embrace him, he literally desires it. This is mostly on a subtextual level, but other times his desire is stiflingly surface-level.

The extent of Ash’s damage is so severe and was inflicted on him so early that his ability to live a normal life was only ever subject to his situation. An argument can be made that his unusually high IQ kept him from the brink of emotional destruction for the majority of his life, but in spite of his incredible virility and strength of character, Ash’s prospects as he aged were always bleak at best. Ash the adult is almost unfathomable. He was literally never allowed to be a child during a key developmental period, and even the manga infers that Eiji’s presence as a romantic element is strongly tied to Ash’s desire to return to a time of innocence. Ash is permanently trapped in a never-neverland of sorts, sexually defiled to the point where his own sexual awakening has been completely obscured beyond his own recognition. His relationship with Eiji is painfully asexual, one, because literally everything about Banana Fish is painful, but also because it is unclear if Ash may have been naturally asexual in the first place or if he was made into an asexual as the result of his childhood trauma. Either way, he certainly doesn’t have a lot of choice about the way that he is, and that way is, fundamentally, morally, and spiritually exhausted. It is only his tenacious spark, his survivors grip to life, and his affection for others in his life whom he loves that are weaker than him, that keeps him stubbornly clung to his own mortal vessel until the very end.

Eiji’s presence as a guiding light is, in THE definitively heartbreaking turn, the permission Ash needs to allow himself to finally die. He has always known that he would die, probably even thought that he should have already died, many, many times over. He is permanently and irreversibly damaged by the course of his life, and though we scream and cry and pray in the hope that Ash can make it, that he can still pull through and come out on the other side living and thriving in love, he was ultimately just never meant to make it that far. Even when Eiji tries to convince Ash that he is not the leopard, that he can come back down from the mountain, we are distantly still aware that this is not true, despite how difficult it is to accept. This difference of character is most clearly seen in Ash’s foil with Yut-Lung; both boys are the savant products of rape-and-murder-riddled childhoods. However, where Yut-Lung lacked anyone to give him acceptance and affection as he grew, Ash ended his time knowing love. Where Yut-Lung survives to the end and goes on to an even higher position of strength, he still has an emotional arc to complete. Yut Lung must discover for himself the value of human life. Ash already knew this value from the beginning, because his moral compass, which sometimes admittedly became scrambled, more or less always pointed true by the end of things.

The argument can be made that as the embodiment of the concept of Salinger’s short story, Ash is fated to die. Eiji, who in many ways is the window through which we experience this world, refuses to bend to fate. He insists in innocence again and again that Ash can change his fate, and for a moment, when Ash finds the plane ticket to Japan in Eiji’s letter, we really, really want to believe him. So, of course, because this manga is singularly cruel, it is here that Ash is stabbed. Of ffffucking course, after everything, death comes for Ash in a fashion which is completely mundane against the grandiose, bombastic scale of the story. An old grudge settled by someone Ash didn’t even have the time to hate in the first place. Ash let himself believe in a real life with Eiji for a single moment, and that proved to be his downfall. When he let his guard down, he let death in. He realizes his destiny immediately, because he is not stupid. His death is not a suicide, it is an understanding.

According to Akimi Yoshida, fate always wins out, but what the manga adds to this sad experience is this; despite everything, unlike Salinger’s broken Seymour, Ash’s heart in the end is full of love. His perfect day to die is the day he reads Eiji’s letter, the letter that declares them permanently bonded. Falling in love allows Ash to let go of himself gently, instead of the infinitely more brutal end he would have met at a villain’s hand otherwise, if he hadn’t fought tooth and nail for his very last scrap of autonomy up until that moment. Eiji’s love as an act of compassion is most perfectly realized; because Ash’s Perfect Day is one of is own making. All the circumstances together form a perfect conclusion. He didn’t see the knife coming, and he didn’t need to. After Papa Dino’s death, after Eiji is gone, Ash can finally stop. He can accept that his trauma is greater than even him. In a life spent being forced back and forth according to the violent winds of his circumstance, he chooses to, (and that’s important, he chooses to,) retreat like a cat to a quiet place of safety to live out his last moments. In this way, Ash’s death is merely a setting down of something unbearably heavy. Because he is loved, because Eiji is safe and far away, Ash is at last released from the prison of his life.

Other Banana Fish Meta: CAPE COD AS PURGATORY AND ASH’S BREAK FROM INNOCENCE

374 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exile story

Sex, drugs, rock ’n’ roll. The Rolling Stones didn’t invent the formula. But they lived it like no other band in history. And when the rapacious taxmen of England came demanding more cash than Mick Jagger and Keith Richards — not to mention bandmates Charlie Watts, Bill Wyman and Mick Taylor — had or cared to pay in the spring of 1971, the Stones moved their party to the South of France.

When they couldn’t find a suitable French Riviera studio to record their 10th album, the Stones set up in the basement of Villa Nellcote, Richards’ rented 16-room mansion on the coast in Villefranche-sur-Mer. All marble and wrought iron, Richards said it looked like it was decorated for “bloody Marie Antoinette.”

He also liked to recount its history as a Gestapo headquarters, where Nazis did nasty things in the same basement the Stones used to jam all night. The hallways still had swastika-shaped air vents. “But it’s all right, we’re here now,” he assured recording engineer Andy Johns.

By making the record in Richards’ own house, band members figured they could get the famously ramshackle guitarist to show up for the sessions. They were wrong. And Richards wasn’t the only one living on the edge. For a six-month stretch, the Stones swapped partners, ingested every available drug, set fires and nearly drove each other mad while crafting rock’s most decadent record, 1972’s “Exile on Main Street.”

On May 16, Universal is reissuing “Exile” in several forms: an 18-track CD; a deluxe edition with 10 previously unreleased songs; and a super-deluxe package with vinyl, a 30-minute documentary DVD and a 50-page photo book.

The Post got an early copy of the music and the “Stones in Exile” documentary, which will premiere Friday on “Late Night with Jimmy Fallon.” From these, fresh interviews and Robert Greenfield’s “Exile on Main Street: A Season in Hell with the Rolling Stones,” we assembled the most debauched stories of sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll from the people who actually lived in “Exile.”

SEX

Gone was the Stones’ usual stream of adoring female fans. For six months, the groupie-gobbling rockers were housebound with significant others. Jagger even got married to Nicaraguan girlfriend Bianca, then pregnant with daughter Jade, during the stretch. Richards shacked up at Nellcote with Italian actress Anita Pallenberg, close pal of Marianne Faithfull and former flame of late Stones guitarist Brian Jones. Fresh from rehab, she arrived with their toddler son, Marlon, in tow.

While the recording went on, she managed to fool around with Jagger and have half-conscious, stoned sex with drug dealer Tommy Weber on a Louis XIV bed while Richards was passed out next to them.

“It was like a royal court where the nobles were sleeping with each other’s women,” says Greenfield, who spent two weeks living at Nellcote — and a third just hanging around — while on assignment for Rolling Stone that May. He wasn’t the only one to notice the band’s exploits.

“Everyone screwed everyone else’s wives and girlfriends,” Johns says. “That’s just the way it was, and you didn’t think too much about that.”

After Jagger married Bianca, Pallenberg did her best to break them up, even starting grade-school-style rumors that Bianca was born a man. Pallenberg got pregnant, too, but kept using heroin. She sought a secret abortion, not because of the drugs, but because she thought the child was Mick’s.

Richards, meanwhile, wasn’t interested in sex at the time, probably due to his heavy drug abuse. One studio regular recalls Pallenberg complaining, “All he wants is the wanking — he never f – – – s me!”

The Stones weren’t the only ones fooling around. Their sidemen were kept busy, too.

“I didn’t mind living between Nice and Monte Carlo, didn’t mind that a bit,” says Bobby Keys, the Texas-born, libertine sax man famous for honking on “Brown Sugar” and every Stones record from 1969 to 1974. “I didn’t mind all them pretty girls around the countryside. Yes sir, buddy! That’s when you’re sh – – – in’ in tall cotton!”

DRUGS

Fueling the excessive behavior at Nellcote was a huge stash of drugs, many smuggled in by Weber, a former Formula One racer turned Afghani hash runner. That May, Weber traveled from England to the Cote d’Azur via Ireland — “in case he was being followed,” Greenfield says — with a pound of coke strapped to the waists of his preteen sons, Charlie and Jake. At age 7, “my function in life was [to be] a joint roller,” says Jake, who grew up to star in the CBS drama “Medium.”

Everyone who visited the house seemed bent on self-destruction. John Lennon threw up at the foot of the stairs one day while touring the premises with Yoko Ono. Richards blamed it on too much sun and wine, but it was more likely the ex-Beatle’s methadone habit.

As Richards was picking up Marlon’s toys in the living room one night, Greenfield watched him grab a mystery pill off the floor. “Bam! He throws it down his throat,” Greenfield says. “Who knows what he put in his mouth, but that’s Keith. Could have been a vitamin, but I don’t think so. Not in that house.”

Jean de Breteuil, the so-called “dealer to the stars” who supplied Jim Morrison with a lethal dose, bought his way into a two-week residence with a toot of ultra-pure pink heroin from Thailand. Richards snorted it from a gold tube he wore around his neck and promptly passed out. Later, Richards paid $9,000 cash ($50,000 today) to a couple of cowboy boot-wearing dealers known as “the Corsicans” for more of the pink junk.

The smack arrived in a plastic bag the size of a two-pound sack of sugar, Greenfield writes, and was so potent it had to be cut with three parts glucose — hence its nickname, “cotton candy.” It lasted a month.

“With a hit of smack,” Richards says, “I could work through anything and not give a damn.”

One night, Richards passed out upstairs after “putting Marlon to bed” — his code for getting loaded. Johns found him with the needle still in his arm, blood spattered on the walls. The studio whiz poked the rock legend to see if he was still alive.

“Of course he picks up the guitar, which he was in bed with, goes, ‘Oh, yeah,’ and starts playing,” Johns says.

Another time, a chauffeur had to pull Pallenberg and Richards, naked and unconscious, from a bed they’d accidentally set on fire. But the rest of the help wasn’t so useful. The couple’s errand boys, local hoods they called “les cowboys,” were suspected of stealing at least nine vintage guitars and Keys’ engraved saxophones when drug debts went unpaid.

By December, French authorities caught wind of the scene and charged the Stones and their pals with heroin possession. As a bonus, Richards and Pallenberg were issued warrants for trafficking. But all of the Stones had high-tailed it to LA a month earlier.

Jagger, Taylor, Wyman and Watts eventually returned to France to face the charges, but a combination of fame, luck and bribes got them freed with mere slaps on the wrists.

Richards and Pallenberg were banned from France for two years, but they had no plans to return, anyway. They’d fled Nellcote in such haste that they abandoned Marlon’s toys, Pallenberg’s wardrobe, Richards’ record collection, a speedboat, a Jaguar E-type sports car and two pets, Boots the parrot and Okee the dog.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I saw Murder on the Orient express today and what struck me most was how the movie addressed the moral quandary presented at the end differently than the book. It’s always interesting to see how an adaptation plays out, and this was definitely a movie made with a 2017 audience in mind.

Just in case there’s someone who hasn’t read the book and is unaware of the ending, be warned: There be spoilers below the cut

I want to focus specifically on the difference between the book and movie ending here. Other people can and will talk about how Murder on the Orient Express fares as an adaptation and a movie. My hot take: The cinematography is nice - for example, there’s a shot through the perspective of a mirror that they use when a suspect is lying that makes their face warp that made for some nice symbolism - but it felt like a cheap knock-off of the Robert Downy, Jr Sherlock movies rather than something starring Poirot. Too much effort in being politically correct and actiony, not enough use of the little grey cells.

Anyway, at the end of the novel after presenting his summation of events Poirot famously lets the murderers go free and presents an alternate solution to the police. Unlike the movie, none of the passengers had attempted to harm him, and some (Princess Dragomiroff in particular) seemed resigned to their fate once they realized Poirot had taken the case.

“If you will excuse me, Monsieur,” she said, “but may I ask your name? Your face is somehow familiar to me.”

“My name, Madame, is Hercule Poirot--at your service.”

She was silent a minute, then: “Hercule Poirot,” she said. “Yes, I remember now. This is Destiny.”

The vast majority of the novel is spent asking the question “Who done it?” but throughout the course of the investigation a second, more difficult question emerges: Was justice served?

Christie paints an unambiguous picture with Ratchett. He’s as guilty as sin for the kidnapping and murder of little Daisy Armstrong, and the way the characters remember the Armstrong family would have been pure narm if it weren’t so damn sad. Daisy was a perfect child, Colonel Armstrong was a war hero, Susanne the French maid was driven to suicide for a crime she had no part of, etc., etc.

The narrative gives Ratchett absolutely zero redeeming qualities, to the point where Poirot has nothing to do with him based on looks alone, while the Armstrong family is presented as lambs led to slaughter. The fact that the courts failed to find him guilty was a gross miscarriage of justice - something the twelve men and women complicit in his murder were seeking to correct.

Colonel Arbuthnot puts it best:

“You prefer law and order to private vengeance?”

“Well, you can’t go about having blood feuds and stabbing each other like Corsicans or the Mafia,” said the Colonel. “Say what you like, trail by jury is a sound system.”

A point Poirot brings up again in his summation:

“Ratchett had escaped justice in America. There was no question as to his guilt. I visualized a self-appointed jury of twelve people who condemned him to death and were forced by exigencies of the case to be their own executioners.”

A few pages later, Poirot lets the passengers go without so much as a fuss. There is no angst, there is no drama. Justice has been served.

The movie, on the other hand, takes a much different approach. Instead of acting as jury and executioner, the twelve men and women who murdered Ratchett were broken souls in need of closure. I don’t think it’s an accident that during the summation they collectively are framed the same way as the disciples in da Vinci’s The Last Supper.

Early on, movie!Poirot makes a comment that there is right and wrong and nothing in between, and during the last voice over is forced to amend that statement. Before making his decision whether or not to go to the police with the correct solution he presents Linda Arden, the mother of the dead Mrs. Armstrong and in this version the mastermind of events, with a test. He offers her a gun that she thinks is loaded and says that if she wants to get away with what she’s done, she’ll have to kill him first.

Instead Arden attempts to shoot herself. Obviously it wasn’t loaded and she breaks down with the knowledge that she will have to live with what she’s done for the rest of her life. Then, and only then, does Poirot come to the conclusion that there are no murderers aboard the train and let them go free.

That’s the difference between 1934 and 2017. In one the morality is presented as black and white, with none of the parties feeling the slightest bit of guilt for correcting a mistake made years ago. In the other a man is murdered and there is no justice, only twelve men and women left trying to pick up the shattered pieces of their broken lives.

It’s that interpretation that makes adaptations so fascinating. Different creators will inevitably have different opinions on questions of morality, ethics, and justice (or what their audience will perceive as such. Don’t want to alienate the audience, eh?). I’m not going to say that Murder on the Orient Express (2017) is a great movie, because it’s not. The brilliance of the mystery itself is not conveyed well, but then again, I’m of the opinion that adapting Poirot’s specific brand of solving crime would be difficult no matter was at the helm. After all, it’s not that visually interesting to film someone sitting down and thinking.

But where the plot of Murder on the Orient Express is famous to the point of being trite and cliche, this question of morality still has room to grow and evolve and become more complex over time. Do I think the movie executed on this potential as well as it could have? No, not at all. But I do think that it’s at least worth talking about.

#Murder on the Orient Express#Agatha Christie#Murder on the Orient Express 2017#Analysis#creative-type reviews#movie analysis#Hercule Poirot

16 notes

·

View notes