#Chen Chi-hwa

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Shaolin Wooden Men (1976)

Chi-Hwa Chen

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Film Journal

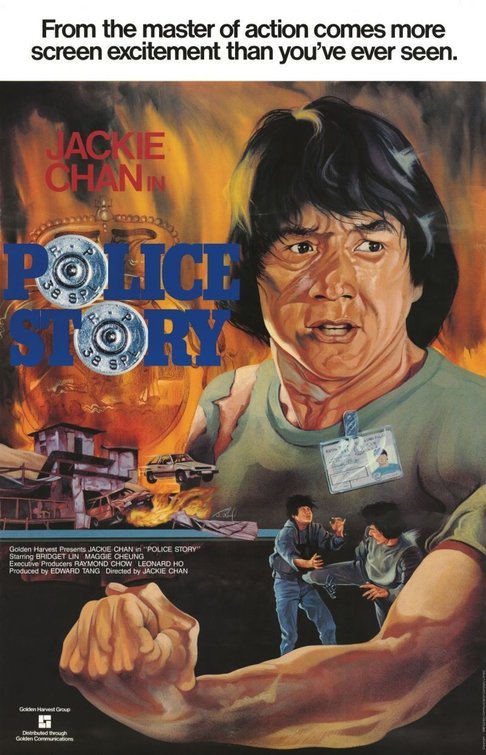

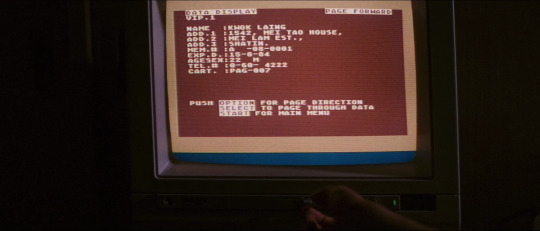

"Police Story" by Jackie Chan and Chi-Hwa Chen

0 notes

Photo

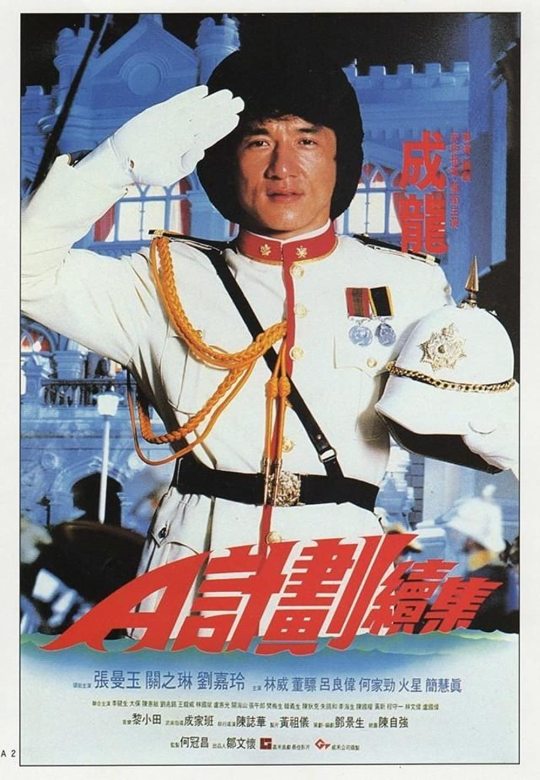

Project A2

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

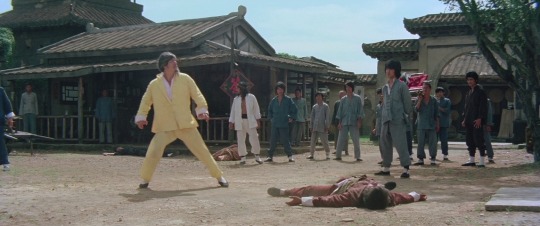

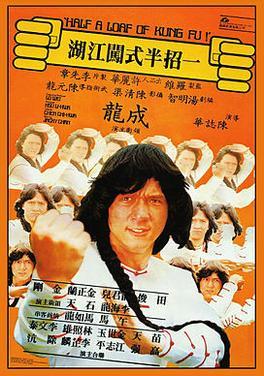

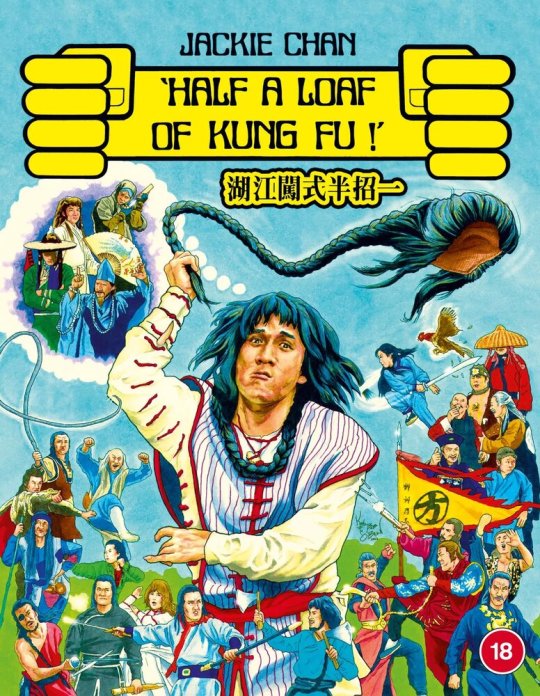

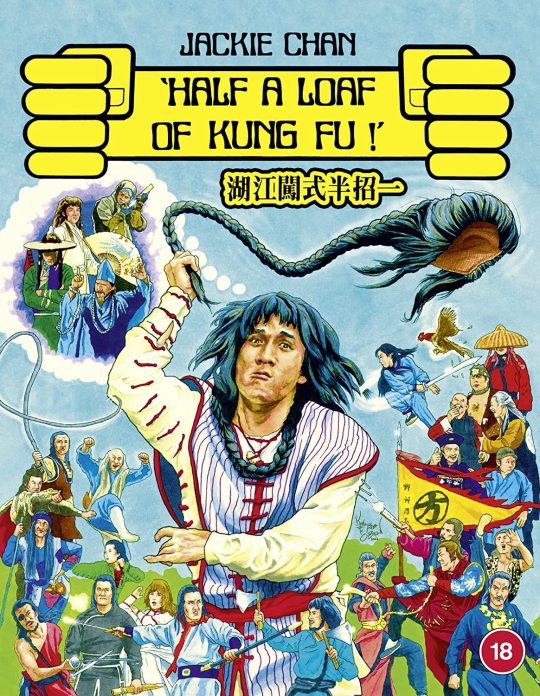

400 Words on HALF A LOAF OF KUNG FU [1978] ★½

1978 was the year Jackie Chan went from being a minor studio player to an international superstar. In March he starred in Yuen Woo-ping’s Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow, the first of his films that stopped trying to make him a Bruce Lee clone and instead embraced his acrobatic and irreverent style of comedic kung fu. In October, Yuen and Chan reunited for Drunken Master, the film that arguably perfected the Jackie Chan formula. But nestled between those two films’s releases is Chen Chi-hwa’s Half a Loaf of Kung Fu. If Chan’s most successful comedies saw him blending martial arts with slapstick silent film stunts à la Buster Keaton, then Half a Loaf channels instead the madcap zaniness and kineticism of Looney Tunes. Consider the opening credits montage. In many wuxia of the era, the credits would play over shots of the lead actor performing kung fu routines in an empty studio. Here, Chan instead acts out a series of 10-15 second comedic vignettes with a group of extras. (The most absurd sees Chan pinned to a wall by enemy knives while posing like a crucified Jesus as a musical stinger from Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar blares!!) The rest of the film is just as inexplicable in its selection of gags and set pieces. Most of it sees Chen grasping at straws for what to throw at the audience next, and indeed for most of the run-time it seems like Chan’s wondering through two or three different movies at once. He runs into several secret kung fu experts, multiple femme fatales, joins or leaves several different clans—the Wu Tang Clan is mentioned in one scene but never shows up, proving that while they may be for the children they’re not for terrible movies—and gets into lots of fights with combatants of perpetually shifting allegiances. Eventually the disparate plot threads collide in the last twenty minutes for a brawl that felt less like a climactic showdown than a recreation of the news teams fight in Adam McKay’s Anchorman (2004). The film’s only bright spot is this fight which, while ridiculous, still manages some inspired choreography, particularly a sequence where Chan frantically studies new moves from a kung fu manual while sparring with the lead villain. It seems Half a Loaf of Kung Fu is half a loaf short from being a good movie.

1 note

·

View note

Text

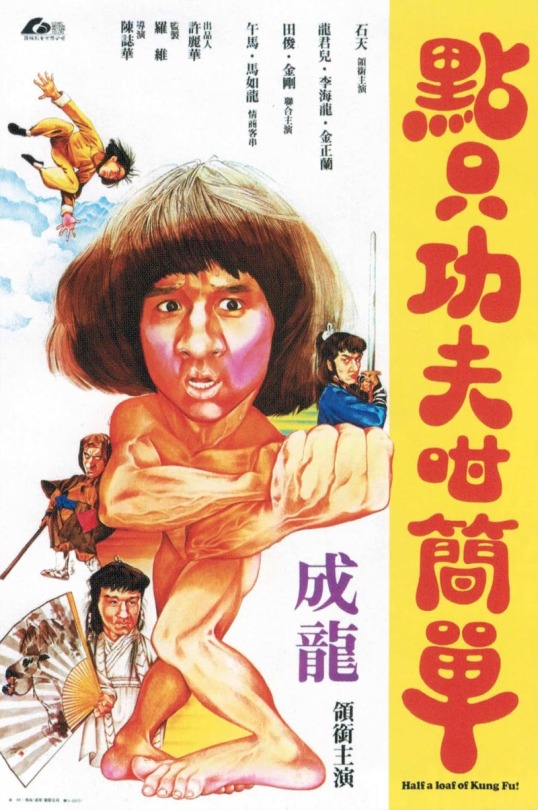

Movie Review | Half a Loaf of Kung Fu (Chen, 1978)

Jackie Chan is known for many things, but good haircuts is not one of them. True, the mop he sported during his '80s and '90s heyday is something of a signature, and one must respect his ability to make it work even if one wouldn't dare it pull it off oneself. And he actually did look pretty sharp in Miracles and Rush Hour when he departed from his usual style, although the former offers a diegetic explanation in that a high rolling '30s gangster would be able to afford a decent barber. Half a Loaf of Kung Fu (a real mouthful of a title; say it ten times fast) features easily his worst haircut, and maybe one of the worst I've seen in a movie, a helmet-like dome with a braid coming out of the back so long he has to wrap it around his neck several times over. I think the worst part about it is the indecisiveness. If you're gonna do a helmet, do a helmet. If you're gonna do a braid, stick to the braid. Pick a lane, Jackie.

This has an awful lot of plot as far as these things go, although I had trouble staying interested. Jackie starts off looking for work, first as a guard, then (as his kung fu isn't up to snuff) as an errand boy. Then after witnessing the death of a kung fu master specializing in the whip, he decides to impersonate him, a ruse that doesn't last for very long. There are bad guys, good guys, some kind of treasure, and I dunno, I wasn't paying too much attention to the specifics. At least one of villains is an old guy with a mustache like you often see in these things. Lieh Lo turned that kind of character into an art form in Lau Kar-Leung's Executioners from Shaolin, and Ng See-Yuen's Invincible Armour offers two for the price of one (as well as one of the funniest villain deaths I've ever seen). It never fails to amuse me that ostensible senior citizens are such deadly martial artists. Another old guy is the beggar who sees through Jackie's disguise, decides to help him and then gives up and hands him a kung fu manual and advises him to self-study. As someone who's tried to weasel out of training people at work by coming up with extremely detailed procedure documents, I found this character pretty relatable. There's also another beggar characterized by extreme flatulence. I found these scenes brutally unfunny, but the character redeemed himself when he started using his walking stick like a pool cue in the climactic action scene.

This is also notable for a couple of strong female characters. One of them is part of the bad guys and specializes in poisons, glimpsed by Jackie to be messing around with snakes early on. There's also the sister of the deceased whip master, who repeatedly slaps Jackie until he stops lying about his identity. And there's the beautiful daughter of one of the good guys (there are a lot of characters in this, and I'm too lazy to sketch out all the relationships) with whom Jackie becomes immediately enamoured and who decides to play a prank on him after seeing him do a not very nice thing in a tavern. Given that they end up wearing matching outfits in the climax, I assume they overcame their differences.

Jackie himself exhibits some of the same goofy charm and physicality that would define him later (an early scene has him eating grass and acting like Popeye), but these aspects of his presence are not quite as cohesive as he would later make them. The same goes for the movie as a whole, which doesn't quite nail the action-comedy balance of his better efforts. The humour here punctuates the seriousness of the story, but doesn't subvert or satirize it, meaning that stretches where one of the (far too) many characters spout exposition will challenge your ability to stay interested. When the movie does lock on Jackie's wavelength however, it is quite enjoyable. The fight choreography is credited to Chan, and while much of it is perfunctory (but still well executed; the standard of competence in Hong Kong action movies is still very high), but you can see him imbue an increasingly prankish quality to the fight scenes as the movie progresses. This dynamic peaks with the climax, which features the aforementioned pool cue moves, Jackie and the beggar working in tandem like circus acrobats, Jackie acting like a matador, attempted castrations (another suggestion the filmmakers had seen Invincible Armour), Jackie parodying Bruce Lee's nunchaku technique, and a villain's wig being torn off. And if the villain's death seems something like a fluke, it's a pretty fitting end for the movie's overall tone.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

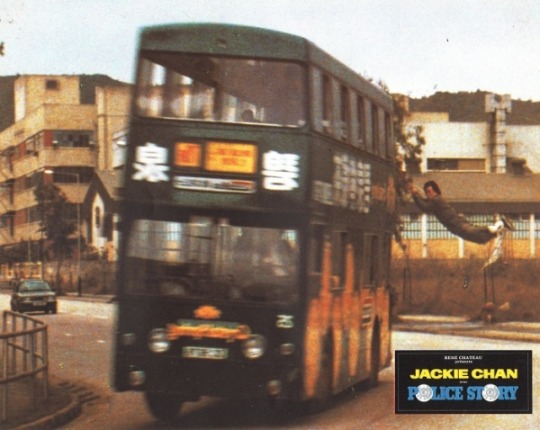

Ging chaat goo si (1985)

#1980s#actor jackie chan#dir jackie chan#dir chi hwa chen#dp yiu tsou cheung#cat action#cat comedy#cat crime#cat thriller#hong kong#green#sweat#brown eyes#shadow#dirt#ging chaat goo si#ging chaat goo si 1985#police story#police story 1985

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

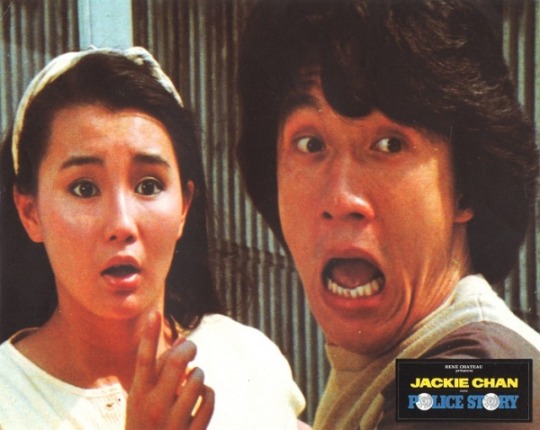

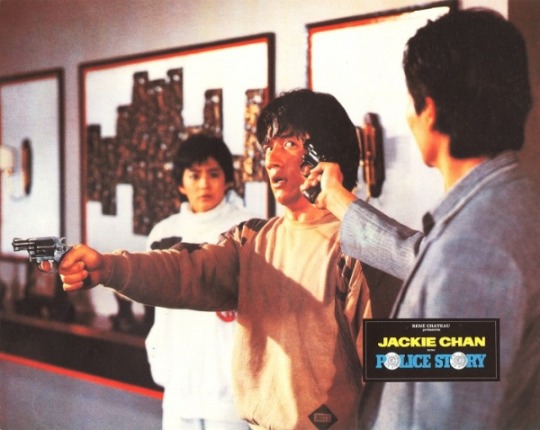

Police Story (1985)

#police story#jackie chan#brigitte lin#chi-hwa chen#martial arts#martialartsedit#80s action movies#ging chaat goo si#chan ka kui

299 notes

·

View notes

Text

Half a Loaf of Kung Fu (1978) dir. Charlie Chen Chi-Hwa

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Police Story | Jackie Chan / Chi-Hwa Chen | 1985

Jackie Chan, Maggie Cheung

74 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Police Story 1985

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

警察故事 (Police Story), 1985.

Dir. Jackie Chan & Chi-Hwa Chen | Writ. Jackie Chan & Edward Tang | DOP Cheung Yiu Cho

#police story#jackie chan#警察故事#10 frames#hong kong cinema#action comedy#1980s#maggie cheung#brigitte lin

125 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Half a Loaf of Kung Fu (Chen Chi-hwa, 1978)

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

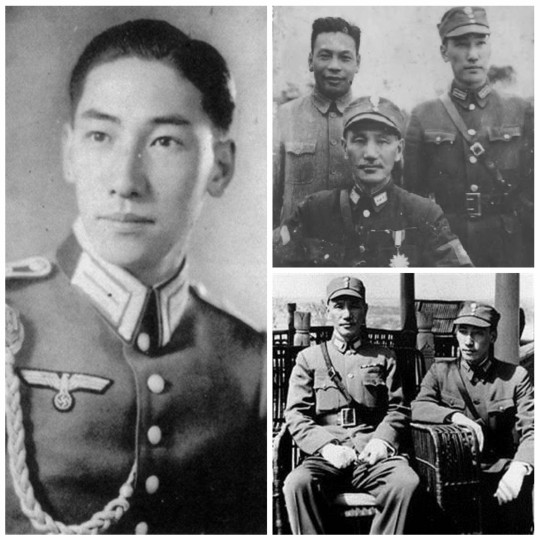

• Chiang Wei-kuo

Chiang Wei-kuo (traditional Chinese: 蔣緯國; simplified Chinese: 蒋纬国) was an adopted son of Republic of China President Chiang Kai-shek. Chiang served in the Wehrmacht before fighting in the Second Sino-Japanese War and Chinese Civil War.

Born in Tokyo on October 6th, 1916 when Chiang Kai-shek and the KMT were exiled to Japan by the Beiyang Government, Chiang Wei-kuo was the biological son of Tai Chi-tao and a Japanese woman, Shigematsu Kaneko (重松金子). Chiang Wei-kuo previously discredited any such claims and insisted he was a biological son of Chiang Kai-shek until his later years, when he admitted that he was adopted. As one of two sons of Chiang Kai-shek, Chiang Wei-kuo's name has a particular meaning as intended by his father. "Wei" literally means "parallel (of latitude)" while "kuo" means "nation"; in his brother's name, "Ching" literally means "longitude". The names are inspired by the references in Chinese classics such as the Guoyu, in which "to draw the longitudes and latitudes of the world" is used as a metaphor for a person with great abilities, especially in managing a country. Chiang moved to the Chiang ancestral home in Xikou Town of Fenghua in 1910. Wei-kuo later studied Economics at Soochow University.

With his sibling Chiang Ching-kuo being held as a virtual political hostage in the Soviet Union by Joseph Stalin having previously been a student studying in Moscow, Chiang sent Wei-kuo to Nazi Germany for a military education at the Kriegsschule in Munich. Here, he would learn the most up to date German military tactical doctrines, organization, and use of weaponry on the modern battlefield such as the German-inspired theory of the Maschinengewehr (Medium machine gun, at this time, the MG-34) led squad, incorporation of Air and Armored branches into infantry attack, etc. After completing this training, Wei-kuo completed specialized Alpine warfare training, thus earning him the coveted Gebirgsjäger Edelweiss sleeve insignia. Wei-kuo was promoted to Fahnenjunker, or Officer Candidate, and received a Schützenschnur lanyard. Wei-kuo commanded a Panzer unit during the 1938 Austrian Anschluss as a Fähnrich, or sergeant officer-candidate, leading a tank into that country; subsequently, he was promoted to Lieutenant of a Panzer unit awaiting to be sent into Poland. Before he was given the mobilization order, he was recalled to China.

Upon being recalled from Germany, Chiang Wei-kuo visited the United States as a distinguished guest of the US Army. He gave lectures detailing on German army organizations and tactics. Whilst in the northwest, Chiang Wei-kuo became acquainted with the local generals and organized an armour mechanized battalion to formally take part in the National Revolutionary Army. In addition, he spent some time in India studying tanks. There, Wei-kuo became a Major at 28, a Lieutenant Colonel at 29, a Colonel at 32 whilst in charge of a tank battalion, and later in Taiwan, a Major General. Chiang Wei-kuo was stationed at a garrison in Xi'an in 1941. Throughout the Second Sino-Japanese War he lead tank battalions. In 1944, he married Shih Chin-i (石靜宜), the daughter of Shih Feng-hsiang (石鳳翔), a textile tycoon from North West China. Shih died in 1953 during childbirth. Wei-kuo later established the Chingshin Elementary School (靜心小學) in Taipei to commemorate his late wife. After the war was over, communist and nationalist conflicts occurred which lead into the Chinese Civil War. During the Chinese Civil War, Chiang Wei-kuo employed tactics he had learned whilst studying in the German Wehrmacht. He was in charge of a M4 Sherman tank battalion during the Huaihai Campaign against Mao Zedong's troops, scoring some early victories. While it was not enough to win the campaign, he was able to pull back without significant problems. Like many troops and refugees of the Kuomintang, he retreated from Shanghai to Taiwan and moved his tank regiment to Taiwan, becoming a divisional strength regiment commander of the armoured corps stationed outside of Taipei.

Chiang Wei-kuo continued to hold senior positions in the Republic of China Armed Forces following the ROC retreat to Taiwan. In 1964, following the Hukou Incident and his subordinate Chao Chih-hwa's attempted coup d'état, Chiang Wei-kuo was punished and never held any real authority in the military again. In 1957, Chiang remarried, to Chiu Ru-hsüeh (丘如雪), also known as Chiu Ai-lun (邱愛倫), a daughter of Chinese and German parents. Chiu gave birth to Chiang's only son, Chiang Hsiao-kang, (蔣孝剛) in 1962. From 1964 onwards, Chiang Wei-kuo made preparations in establishing a school dedicated to teaching warfare strategy; such a school was established in 1969. He was also the Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of China from 1968 to 1969. In 1975, Chiang Wei-kuo was further promoted to the position of general, and served as president of the Armed Forces University. In 1980, Chiang served as joint logistics commander in chief; then in 1986, he retired from the army and became National Security Council Secretary-General. In 1993, Chiang Wei-kuo was employed as the advisor of the president of the Republic of China. After Chiang Ching-kuo's death, Chiang was a political rival of native Taiwanese Lee Teng-hui, and he strongly opposed Lee's Taiwan localization movement. Chiang ran as vice-president with Taiwan Governor Lin Yang-kang in the 1990 ROC indirect presidential election. Lee ran as the KMT presidential candidate and defeated the Lin-Chiang ticket. In 1991, Chiang's housemaid, Li Hung-mei (李洪美, or 李嫂) was found dead in Chiang's estate in the Taipei City. The following police investigation discovered a stockpile of sixty guns on Chiang's estate. Chiang himself admitted the possibility of a link between the guns and his maid's death, which was later ruled a suicide by the police. The incident permanently tarnished Chiang Wei-kuo's name, at a time when the Chiang family was increasingly unpopular on Taiwan and even within the Nationalist Party.

In the early 1990s, Chiang Wei-kuo established an unofficial Spirit Relocation Committee (奉安移靈小組) to petition the Communist government to allow his adopted father Chiang Kai-shek and brother Chiang Ching-kuo to be interred in mainland China.His request was largely ignored by both the Nationalist and Communist governments, and he was persuaded to abandon the petition by his father's widow in November 1996. In 1994, a hospital was supposed to be named after him (蔣緯國醫療中心) in Sanchih, Taipei County (now New Taipei City), after an unnamed politician donated to Ruentex Financial Group (潤泰企業集團), whose founder was from Sanchih. Politicians questioned the motivation. In 1996, the Chiang home on military land was finally demolished by the order of the Taipei municipal government under Chen Shui-bian. Chiang Wei-kuo died at the age of 80, on September 22nd, 1997, from kidney failure. He had been experiencing falling blood pressure complicated by diabetes after a 10-month stay at Veteran's General Hospital, Taipei. He had wished to be buried in Suzhou on the mainland but was instead buried at Wuchih Mountain Military Cemetery.

#world war 2#world war ii#second world war#history#chinese history#second sino japanese war#military history#german history#biography#chiang kai shek#taiwan

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

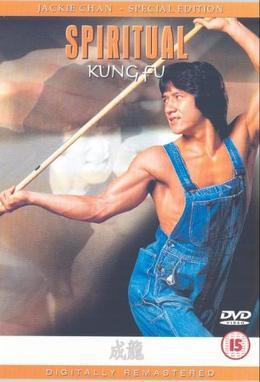

400 Words on SPIRITUAL KUNG FU [1978] ★★½

Producer Lo Wei wasn’t quite sure what to do with Jackie Chan after he returned from being loaned to Seasonal Film Corporation in 1978 for a two picture deal with director Yuen Woo-ping. Wei had helped launch Chan’s career in 1976 by casting him as the lead in a number of unsuccessful Bruceploitation films. But after the smash success of Chan’s two kung fu comedies with Yuen, suddenly he was one of the hottest performers in Hong Kong. Yet Wei still couldn’t quite get the hang of how to use him. He tried reverting back to the Bruceploitation format with the dour, overly serious Dragon Fist (1979), and he tried replicating Wong-ping’s comedic magic with other directors like Chen Chi-hwa for the wacky yet terminally scattershot Half a Loaf of Kung Fu (1978). Wei’s own Spiritual Kung Fu was another attempt to reverse engineer the Chan formula, this time throwing him into a supernatural comedy. But unlike Chan’s fellow Peking Opera School graduate Sammo Hung who pioneered a new horror comedy subgenre with his own martial arts hybrid Mr. Vampire (1985), Wei’s film didn’t make significant waves. Spiritual Kung Fu isn’t a bad film by any means, and it has a surprisingly original plot when compared to Chan’s other films of the era: after a thief steals a tome containing a forbidden style of kung fu from the Shaolin Temple’s library, upstart student Yi-Lang (Chan) is contacted by five ghosts who teach him the long-lost techniques that can counter them. The issue is the slapdash execution. Most of Spiritual Kung Fu is played as a straight mystery thriller. There are secret identities, mysterious assassinations, and shocking twists galore as the monks feverishly try to figure out who stole the secret techniques and why. Yet the scenes with Chan and the ghosts are played like crude, childish farce. The ghosts—who with their white, full body leotards, skirts, and yarn-like red hair look like malevolent Raggedy Andy’s—act like young, petulant schoolchildren as they go about invisibly causing mischief and mayhem. Still, the fight scenes are superb, particularly a prolonged sequence near the end where Yi-Lang passes the Shaolin Temple’s final examination by defeating over a dozen opponents simultaneously while armed only with twin tonfa. The shots of Chan fending off four, five, or six enemies at once are dizzying masterstrokes of fight choreography.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Preview- Half a Loaf of Kung Fu (Bluray)

Preview- Half a Loaf of Kung Fu (Bluray)

While the mighty Shaw Brothers were dominating the Hong Kong martial arts scene with hard-hitting features like THE CHINESE BOXER and dazzling us with an aesthetic brilliance found in productions such as LEGENDARY WEAPONS OF CHINA or THE SHAOLIN DISCIPLES, writer and star JACKIE CHAN and director Chen Chi-Hwa were cutting across much of the pomposity associated with many of these types of films…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note