#Charles Stewart Parnell

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#OTD in Irish History | 17 April:

In the Liturgical calendar, today is the Feast Day of Saint Donnán of Eigg, a Gaelic priest, likely from Ireland, who died on this date in 617. He attempted to introduce Christianity to the Picts of northwestern Scotland during the Early Middle Ages. Donnán is the patron saint of Eigg, an island in the Inner Hebrides where he was martyred. The Martyrology of Donegal, compiled by Michael O’Clery…

View On WordPress

#irelandinspires#irishhistory#OTD#17 April#Bernadette Devlin#Charles Stewart Parnell#Co. Wicklow#Fiachra Mangan Photography#Glenmalure#History#History of Ireland#Ireland#Irish History#Lord Mayor of Cork#Paul McGrath#The Black Pearl#Today in Irish History#Tomás MacCurtain

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy St Paddy’s Day

#shut up alex#personal#st patrick’s day#st patricks day#irish#ireland#celtic#irish american#leprechaun#st patrick#cu chulainn#hugh o’neill#brian boru#theobald wolfe tone#daniel o’connell#charles stewart parnell#patrick pearse#michael collins#bobby sands#sonic#pokémon#sonic the hedgehog#st patricks day 2024

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“No man has the right to fix the boundary to the march of a nation. No man has the right to say to his country - thus far shalt thou go and no further.” ~ Charles Stewart Parnell

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

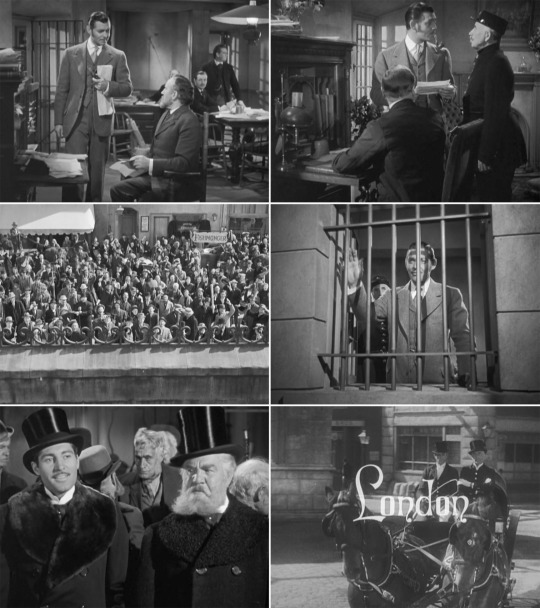

Parnell is a 1937 biographical film starring Clark Gable as Charles Stewart Parnell, the famous Irish politician. It was Gable’s least successful film and is generally considered his worst, and it is listed in The Fifty Worst Films of All Time.

Part II

#Parnell 1937#Parnell movie#biographical film#Clark Gable#Charles Stewart Parnell#old hollywood#old hollywood movies#old hollywood drama#old hollywood classic#golden age of hollywood#old movies#costume drama#historical drama#Myrna Loy

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Des manifestants qui réussissent

Petit retour sur les quatre premières semaines de manifestations des Gilets jaunes en 2018 et sur ce qu’ils ont obtenu :

– Abandon de la hausse de la taxe sur les carburants

– Abandon de la hausse de la taxe sur les retraités

– Hausse du salaire minimum

– Le gouvernement réfléchit à l’idée d’inscrire le vote d’initiative populaire dans la constitution

– 75% d’approbation de la population après leur 5ème semaine d’action.

Cela peut sembler peu pour beaucoup de Français, mais souvenez-vous, cette année, les quatre mois de grèves traditionnelles des cheminots n’ont rien obtenu du tout, mais ils ont perdu quatre mois de salaire. Et cela dure depuis des décennies. Malgré ce que la grande majorité des médias rapportent à propos de ce mouvement, il ne s’agit pas de mettre le feu aux monuments de Paris. Jusqu’à présent, nous pouvons apprendre beaucoup des méthodes efficaces des Gilets jaunes :

– Les Gilets jaunes n’ont pas de représentants, pas de chef à corrompre ou à mettre en prison. Le mouvement utilise une multitude de plateformes de médias sociaux pour coordonner les groupes locaux. Les penseurs alimentent ce réseau et, grâce à Internet, les idées et les opinions sont débattues en quelques heures. Les Gilets jaunes ont atteint l’efficacité sans autorité centralisée.

– Leur organisation est très flexible et réactive. Bien que le mouvement ait commencé contre une augmentation de la taxe sur les carburants, l’idée que la démocratie directe était la solution s’est imposée en moins d’une semaine. Un autre exemple est la rapidité avec laquelle ils ont demandé aux gens d’arrêter de réagir à la violence par la violence entre le 8 et le 15 décembre, dès qu’ils ont réalisé que c’était contre-productif et loin de leur objectif.

– Les Gilets jaunes ne se concentrent pas sur la capitale, même si c’est la partie visible dans les médias. Ils considèrent que ce serait donner trop d’importance au chef de l’État alors qu’ils promeuvent l’idée que le pouvoir vient du peuple.

– Ils concentrent leurs efforts sur les intérêts économiques de ceux qui commandent le gouvernement plutôt que sur les symboles du pouvoir. Jusqu’à présent, en ouvrant les péages autoroutiers, Vinci a admis avoir subi des dizaines de millions de pertes et ses actionnaires paniquent. La confédération nationale des grands détaillants s’alarme de la perte de 40 % des ventes avant Noël. Les élites politiques n’écoutent pas la rue, mais elles prennent en compte les alarmes des conglomérats qui financent leur mode de vie.

Tout cela n’est pas nouveau, la plupart de ces mesures ont été non seulement réfléchies mais aussi utilisées dans le passé, notamment par Charles Stewart Parnell (Boycott – Wikipedia: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boycott) et Gandhi (Marche du sel – Wikipedia: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marche_du_sel).

University of Kansas – Conducting a Direct Action Campaign | Section 17. Organizing a Boycott | Main Section | Community Tool Box: https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/advocacy/direct-action/organize-boycott/main

History of Successful Boycotts | Ethical Consumer: https://www.ethicalconsumer.org/ethicalcampaigns/boycotts/history-successful-boycotts

Gilets jaunes : le chiffre d’affaires de la grande distribution en forte baisse – Le Journal du Dimanche: https://www.lejdd.fr/Politique/gilets-jaunes-le-chiffre-daffaires-de-la-grande-distribution-en-forte-baisse-3808691

“Gilets jaunes”: Vinci autoroutes déplore “plusieurs dizaines de millions

– Zone bourse: https://www.zonebourse.com/VINCI-4725/actualite/Gilets-jaunes-Vinci-autoroutes-deplore-plusieurs-dizaines-de-millions-27760628/

France. La police doit cesser de recourir à une force excessive contre les manifestants et les lycéens – Amnesty: https://www.amnesty.fr/presse/france.-la-police-doit-cesser-de-recourir-a-une-force

Yellow vests referendum initiative can be ‘good instrument in Democracy’: French PM – The Nation: https://nation.com.pk/17-Dec-2018/yellow-vests-referendum-initiative-can-be-good-instrument-in-a-democracy-pm

V for Vendetta – MovieReview ChrisStuckmann: https://youtu.be/jIE7XhW0LPo

----------------------------------------------------

Successful Protesters: https://www.aurianneor.org/successful-protesters-lets-have-a-quick-look-back/

Exitosos manifestantes: https://www.aurianneor.org/exitosos-manifestantes/

Succesvolle Demonstranten: https://www.aurianneor.org/succesvolle-demonstranten/

Succesfulde demonstranter: https://www.aurianneor.org/succesfulde-demonstranter/

Protestanti di successo: https://www.aurianneor.org/protestanti-di-successo/

skuteczni-demonstranci: https://www.aurianneor.org/skuteczni-demonstranci/

erfolgreiche demonstranten: https://www.aurianneor.org/erfolgreiche-demonstranten/

Manifestantes bem sucedidos: https://www.aurianneor.org/manifestantes-bem-sucedidos/

Manifestants reeixits: https://www.aurianneor.org/manifestants-reeixits/

Sikeres tiltakozók: https://www.aurianneor.org/sikeres-tuntetok/

Simon Sinek – Start with why: https://www.aurianneor.org/simon-sinek-start-with-why-bonuses/

Le chiffon rouge moderne: https://www.aurianneor.org/le-chiffon-rouge-moderne-le-chiffon-rouge/

Le levier économique: https://www.aurianneor.org/le-levier-economique-charles-stewart-parnell/

Demainlefilm – Chap 3: L’Economie: https://www.aurianneor.org/demainlefilm-chap-3-leconomie-demainlefilm/

Voix: https://www.aurianneor.org/voix-alimentation-la-ruche-qui-dit-oui/

Colosses aux pieds d’argent: https://www.aurianneor.org/colosses-aux-pieds-dargent-si-ils-perdent-un/

Le RIC – Référendum d’initiative citoyenne: https://www.aurianneor.org/via-httpswwwyoutubecomwatchv-e2lnzwuy4ks/

Initiative Populaire: https://www.aurianneor.org/initiative-populaire-comment-lancer-une-initiative/

Oui au Référendum d’initiative populaire: https://www.aurianneor.org/oui-au-referendum-dinitiative-populaire-petition/

Exijimos el R.I.C.: https://www.aurianneor.org/exijimos-el-ric-peticion-a-la-un-para-el/

Marre de la grève? Demandez le référendum d’initiative citoyenne!: https://www.aurianneor.org/marre-de-la-greve-demandez-le-referendum/

Le référendum est une arme qui tue la violence: https://www.aurianneor.org/le-referendum-est-une-arme-qui-tue-la-violence-oui/

Police, Armée: https://www.aurianneor.org/police-armee-manif-des-policiers-je-suis-gilet/

Police et justice pour le peuple: https://www.aurianneor.org/police-et-justice-pour-le-peuple/

Vème République, toujours là…: https://www.aurianneor.org/veme-republique-toujours-la-to-read-this-in/

Découvrez les revendications des gilets jaunes: https://www.aurianneor.org/zero-sdf-retraites-salaire-maximum-decouvrez/

La situation des gilets jaunes aujourd’hui: https://www.aurianneor.org/la-situation-des-gilets-jaunes-aujourdhui-1-un/

“WE ARE NOT FOOLED”: https://www.aurianneor.org/nous-ne-sommes-pas-dupes-collectif-yellow/

Les rouges et les jaunes: https://www.aurianneor.org/les-rouges-et-les-jaunes-foulards-rouges-contre/

L’écoterrorisme: https://www.aurianneor.org/lecoterrorisme/

Les 1% les plus riches sont en guerre contre le reste du monde: https://www.aurianneor.org/les-1-les-plus-riches-sont-en-guerre-contre-le-reste/

Quand on a un marteau dans la main, tout ressemble à un clou: https://www.aurianneor.org/quand-on-a-un-marteau-dans-la-main-tout-ressemble/

“For to win one hundred victory”…: https://www.aurianneor.org/for-to-win-one-hundred-victories-in-one-hundred/

Guerre et Paix à l’ONU: https://www.aurianneor.org/guerre-et-paix-a-lonu-en-1961-lavion-du/

Le racisme de classe: https://www.aurianneor.org/le-racisme-de-classe/

#action#boycott#campagne#charles stewart parnell#confédération#constitution#démocratie#éconòmie#france#ghandi#gilets jaunes#manifestants#non-violence#organisation#paris#pouvoir#représentants#rue#sel#succès#violence#vote#🇫🇷

1 note

·

View note

Text

DUBLINBIKES DOCKING STATION 97

Today as an experiment I invited Google Bard to describe Dublinbikes Docking Station at Kinmainham Gaol and here is what I got

ACCORDING TO GOOGLE BARD I asked Google Bard to describe Dublinbikes Docking Station at Kinmainham Gaol and here is what I got: Dublinbikes Docking Station 97 is located at Kilmainham Gaol, a former prison in Kilmainham, Dublin, Ireland. The station is located at the corner of Inchicore Road and Kilmainham Lane, just a short walk from the entrance to the gaol. The station has 12 spaces for…

View On WordPress

#Anne Devlin#Charles Stewart Parnell#common criminals#Countess Markievicz#Docking Station#DublinBikes#Fotonique#Gaol#Google Bard#Infomatique#Jail#Kilmainham Gaol#leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising#National Monument#opened in 1796#political prisoners#Public Transport#Robert Emmet#Station 97#stonebreaker’s yard#struggle for independence#the Fenians#William Murphy

0 notes

Text

Sometimes you just gotta pretend that Marius von Raum would give a fuck about the political climate of Ireland in the 1880s and move on

#trying to write an essay on charles stewart parnell#every time i finish a paragraph i eat a sweet and pretend he's giving me a mysterious pill that keeps me alive#the mechanisms#marius von raum

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every time I need to purchase gifts for someone that one post about how it's only easy to buy gifts for people who have obsessions becomes more and more real

#buying gifts for my brother who is obsessed with [redacted] FC is soooo easy. as is for my mother who is obsessed with charles#stewart parnell and james joyce. however I have never known what to get anyone else in my life#jory.txt

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

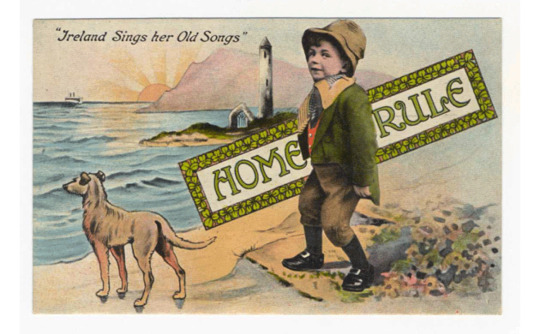

Life of Charles Stewart Parnell, from the Histories of Poor Boys and Famous People series of booklets (N79) for Duke brand cigarettes. 1888. Credit line: The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, Gift of Jefferson R. Burdick https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/423821

#aesthetic#art#abstract art#art museum#art history#The Metropolitan Museum of Art#museum#museum photography#museum aesthetic#dark academia

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bram Stoker and Irish independence

I keep seeing posts popping up in the Dracula Daily tag about Bram Stoker being Irish, implying that we can draw conclusions from that about his politics, his attitude towards Britain, or the British Empire as a whole. I thought it might be useful to provide a bit of context.

Standard disclaimer: I'm not a historian and this period of Irish history is very complicated. I'm going to do my best but this will be a simplification, because otherwise an already long post would become a novel.

Less-standard disclaimer: I'm only going to go into some of Bram Stoker's views here. Others, such as his egregious racism, obviously also have a bearing on his views on empire... but again, a novel.

A very brief history of Ireland in the 19th century

god i have no idea how to simplify this

OK let's go. At the start of the 19th century, Ireland was a primarily Catholic, Irish-speaking country ruled by a primarily Protestant, English-speaking minority. The bulk of the Irish population faced colonial discrimination in a host of different ways, from restrictions that promoted English trade over Irish trade to laws that restricted Catholics from holding public office. The result was a long series of rebellions and risings against British rule, most recently in 1798. Though there was slow progress towards Catholic emancipation, especially in the 1820s.

In the 1840s, a potato blight affected the Irish staple potato crop. The British response - providing very little in the way of famine relief and continuing to export other crops from Ireland to Britain - turned a natural disaster into a genocide. A million people died and roughly twice that number emigrated. Ireland has yet to recover to its pre-Famine population.

A long-term consequence of the Famine was the decline of the Irish language. Irish-speaking areas were among the worst affected, and by 1900, Ireland was majority English-speaking. Another contributing factor was establishment of National Schools from the 1830s onwards, in which students were prohibited from speaking Irish.

In the second half of the 19th century, different movements arose to address these problems. There were campaigns for land rights, to protect tenant farmers; there was a movement to revive Irish culture and the Irish language; and there were different campaigns for how Ireland should be governed.

Independence was advocated for by groups such as the IRB, who supported taking up arms for complete freedom from the British Empire. Among the landed middle classes who were able to vote, this was a fringe position in the second half of the 19th century.

Home Rule was the idea that Ireland should remain in a union with Britain, under the British Crown, but that an independent Irish government should have complete control over domestic matters. This was the mainstream nationalist position in the late 19th century, and was the position of most of the Liberal Party in the UK.

Unionism was support for the status quo, and opposition to any devolution of power to Ireland. This was the position of the Conservative (Tory) Party in the UK.

In elections in the 1850s, Irish voters (male landowners only) were relatively split between Liberals and Tories. But by the 1870s, even this unrepresentative group of people voted overwhelmingly for the new Home Rule Party and its successor the Irish Parliamentary Party. That remained the majority view of Irish nationalists until WW1.

The leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, Charles Stewart Parnell, persuaded Liberal PM William Gladstone of the importance of Home Rule. In 1886, Gladstone introduced a Home Rule bill to Parliament, but it was defeated in the House of Commons by 30 votes, causing Gladstone to lose power. In 1890, Parnell was revealed through a divorce case to be in a relationship with a married woman, causing a scandal that split his party. In 1893, after Parnell's death, Gladstone was returned to power and attempted a second Home Rule bill, which passed the Commons but was defeated in the Lords.

And that's the context in which Bram Stoker wrote Dracula.

Bram Stoker's views on Home Rule

The starting point is that we don't know a huge amount about Stoker's views on anything. The Irish Times describes him as "so private we know little of his life." Here's a bit of what we do know.

He was a Protestant from a comfortable middle-class background. Here's where he grew up:

He studied at Trinity College Dublin, which Catholics were barred from attending (by their own leadership) on the grounds that attendance constituted "a moral danger to the faith of Irish Catholics." There, he would have been surrounded by committed Unionists; Trinity was its own parliamentary constituency and voted for Conservative MPs long after the rest of Ireland was supporting Home Rule.

At the same time, he was making friends with nationalists such as John Dillon and described himself as a "philosophical Home Ruler". (Source, which is amazingly comprehensive on the events of Stoker's life).

He must have liked that phrase, because when he wrote his Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving, published in 1906, he was still using it:

We were all, whatever our political opinions individually, full of the Parnell Manifesto [published 1890 after the divorce scandal and attacking Gladstone] and its many bearings on public life. For myself, though I was a philosophical Home-Ruler, I was very much surprised and both angry at and sorry for Parnell's attitude, and I told Mr. Gladstone my opinion. He said with great earnestness and considerable feeling: "I am very angry, but I assure you I am even more sorry." I was pleased to think - and need I say proud also - that Mr. Gladstone seemed to like to talk politics with me...

Above all his admiration for Gladstone, and pride in having him as a friend, shines through in this section.

Different sources interpret what a "philosophical Home-Ruler" is differently. It may be "one who accepted Home Rule as more necessary than ideal" or supporting "Home Rule brought about by peaceful means"; either way, it seems his support for Home Rule was qualified, not full-blooded.

Overall Stoker held a mainstream view, neither adamantly pro-independence nor a defender of the status quo in Ireland. He also seems to have been quite happy to maintain friendships with people who disagreed with him, whether they were Tories or more radically pro-independence.

This is less exciting than takes that I've seen out in the wild, such as "Bram Stoker hated the British Empire and that's why Dracula attacks English people". But it seems to be what the evidence bears out.

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the Highest Perfection

Avondale, County Wicklow is now irrevocably associated with its late-19th century owner, Charles Stewart Parnell – and anyone who visits the place cannot escape seeing his image across the house and grounds. Less well-known, however, and certainly not as well remembered, is the man who was responsible both for building the house and developing the estate that Parnell was eventually to inherit:…

View On WordPress

#Architectural History#Avondale#County Wicklow#Georgian Architecture#Historic Interiors#Irish Country House#The Big House

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in 1886 – Home Rule Bill introduced in English Parliament by William Gladstone.

The Acts of Union 1800, united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland (previously in personal union) to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. At various intervals during this time, attempts were made to destabilise Anglo-Irish relations. Rebellions were launched in 1803, 1848, 1867, and 1916 to try to end British rule over Ireland. Daniel O’Connell in the…

View On WordPress

#Anglo-Irish Treaty#Arthur Griffith#British Commonwealth#Charles Stewart Parnell#Edward Carson#England#History#History of Ireland#Home Rule#Ireland#Irish History#Isaac Butt#Prime Minister William Gladstone#Terence MacSwiney#Ulster

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

added a new section, which I will quote here for the fun of it

Some Additional Stuff To Know

Joyce's books take place, generally, at the turn of the 20th century in Dublin, the capital city of Ireland. That was a culture more similar to ours than one might expect, but separated by the ravages of time. Here is where I'll list some general tidbits of context that may help bridge that gap.

WHO THE HELL WAS CHARLES PARNELL? (a skimming of a complex situation)

Ireland was a colony of the British Empire, who kept a financial and political grip. The history of that is, uh, long and strained. There were, of course, nationalist elements throughout Ireland seeking independence-- the late 1800s saw a number of radicals attempting assassination, rabblerousing, terrorism (I should really refresh my knowledge of this and give a better list sometime), but the State prioritized their neutralization and the People generally tried to keep distance from them. Instead, it was far more common for Irish citizens to live with general discontent and political apathy, as the status quo was entrenched and they saw no way out anytime soon.

Then came Charles Stewart Parnell. From the 1870s through the 1880s, Parnell came to be known as a noble and respected politician who supported Irish Independence and had the know-how to pursue it democratically. He condemned the violent acts and commanded parliament the 'right' way. And so he gave people hope.

HOWEVER. Around 1890, when other attempts to smear his name fell through, one campaign succeeded in ousting him: Word got out about a scandal. Parnell had been keeping a long affair with a married woman (Kitty O'Shea). There were letters. The press took the story and ran with it. Parnell assured his supporters he would be exonerated, but it was too late. The Catholic Church were disgusted; its priests instructed their congregations to view him as a symbol of immorality and danger. And, y'know what, it worked. Parnell lost his public and never got them back. His health rapidly deteriorated and he died shortly after, in 1891.

This is all important to know, as James Joyce was a child when this scandal broke out. His father and uncle were diehard Parnell supporters, even through the scandal, while his governess piously kept with the Church. He witnessed the violent fracturing of a united home, furthermore of a united people. The next few decades were marked by generational grief and a sense of betrayal-- the pious felt betrayed by Parnell's immorality, the fervent felt betrayed by the People's disloyalty. Joyce fell on the latter side, and thus so did his fictional Stephen Dedalus.

If you read any of Joyce's books, you will find references to Parnell, and the broader symbol of a public that wants a hero so they can tear him apart ("Ireland is the sow that eats her young"). In Dubliners, the story "Ivy Day in the Committee Room" shows the remnants of a parliamentary party haunted by Parnell's shadow. In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, you'll see the impact this had on a young Stephen. And Ulysses takes place over a decade after this all went down, so it's less direct, but the memory of Parnell still rests with the city. (During the "Wandering Rocks" episode, Buck Mulligan and Steve Haines see Parnell's brother!) And Finnegans Wake, finally, allows Parnell's ghost a chance to blend in with the rest of history as another HCE figure, builder of cities, father of peoples.

TUBERCULOSIS (was not to be scoffed at)

At the time of writing this website, we have a global, uh, sensitivity to viral contagion. Covid has us rethinking our place in the world. So it's with that in mind that I bring up TB, the scourge of, uh, a lot of human history, and certainly of the era in which Joyce's books are set.

look man, I'm not the best source for a well-informed overview of a serious disease. forgive me for the casualness here. the truth is, Joyce's books hardly mention TB explicitly, and this is in fact a subject I only became truly aware of like a year ago, so you'd be forgiven for glossing it over too, BUT THAT'S WHY THIS SECTION IS HERE, because TB is absolutely an implicit presence.

The people of Joyce's books know about TB and want to avoid it, but they would rather not go around talking about it because it's a bummer, and Joyce felt no need to spell any of this out because everyone was aware of TB back then, we are an outlier because we actually got a vaccine for it in the 20th century and it was a huge deal. TB is bad. You cough up blood, you deteriorate, you die. And it is very contagious.

People obviously did not have an internet back then, nor did they have airtight ways of spreading helpful information, they just had pillars of tradition that were optimized for specialized subjects and the robust if sometimes slow networks of gossip. General knowledge of TB was "it's bad, and it spreads somehow." There were theories as to how it spread, and therefore how to avoid it, but the common ones... well, their hearts were in the right place. The theory that struck closest, if still inaccurate, was "it spreads through dust and spit. do not make intimate contact with someone before marriage, and keep your house clean." Joyce himself had studied medicine and tried his best to keep up to date with this kind of thing, and that is the theory he sticks to in his books.

So. Dust, and intimacy (specifically with someone who already has TB). When characters in Joyce have dusty furniture, when characters are aware of the dust, keep in mind the deadly implications. When characters long for an intimacy that feels incredibly out of reach, I mean there are a lot of factors there, but remember this one in the back of your head. There is always more context than you know.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The Pogues - Greenland Whale Fisheries.

'Greenland Whaling Fisheries' is a traditional ballad about the whaling industry, written in the 1700s or before, with hundreds of variants that name different dates, ships, and captains. This version appears on 'Red Roses For Me', the debut album of the now defunct, London-Irish, punk-folk band, The Pogues.

It was perfect material for the band, who sang about the harsh realities and down-trodden lives faced by ordinary folk, often set within a historical context: navvies working on the railroad, immigrants crossing the Atlantic in droves, war-beaten soldiers, drunks, drug addicts, prostitutes and rabble-rousers.

The band were a big influence on my way of viewing the world in the 1980s, when I was studying for A-Level History and choosing Charles Stewart Parnell ('The Uncrowned King of Ireland') as my specialist subject (their song 'Kitty' is about the love affair with a married woman which brought about his political downfall).

The Pogues are partly the reason why I moved to Ireland in the 1990s and travelled to both north and south of the country. The other reason being that my grandmother's side of the family were Irish immigrants who travelled over to Bradford (in I don't know what year) to work in the woollen mills. They were originally from Roscommon and Galway, apparently, and some of them were a bunch of rogues!

Hehehehehe!

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Parnell is a 1937 biographical film starring Clark Gable as Charles Stewart Parnell, the famous Irish politician. It was Gable's least successful film and is generally considered his worst, and it is listed in The Fifty Worst Films of All Time.

Part I

#Parnell 1937#Parnell movie#biographical film#Clark Gable#Charles Stewart Parnell#old hollywood#vintage hollywood#old hollywood movies#old hollywood drama#golden age of hollywood#old movies#costume drama#historical drama#Myrna Loy#Edna May Oliver#Billie Burke#Alan Marshal

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

A boycott is an act of nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organization, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for moral, social, political, or environmental reasons. The purpose of a boycott is to inflict some economic loss on the target, or to indicate a moral outrage, usually to try to compel the target to alter an objectionable behavior. The word is named after Captain Charles Boycott, agent of an absentee landlord in Ireland, against whom the tactic was successfully employed after a suggestion by Irish nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell and his Irish Land League in 1880.

Sometimes, a boycott can be a form of consumer activism, sometimes called moral purchasing. When a similar practice is legislated by a national government, it is known as a sanction. Frequently, however, the threat of boycotting a business is an empty threat, with no significant effect on sales. The word boycott entered the English language during the Irish "Land War" and derives from Captain Charles Boycott, the land agent of an absentee landlord, Lord Erne, who lived in County Mayo, Ireland. Captain Boycott was the target of social ostracism organized by the Irish Land League in 1880. As harvests had been poor that year, Lord Erne offered his tenants a ten percent reduction in their rents. In September of that year, protesting tenants demanded a twenty-five percent reduction, which Lord Erne refused. Boycott then attempted to evict eleven tenants from the land. Charles Stewart Parnell, the Irish leader, proposed that when dealing with tenants who take farms where another tenant was evicted, rather than resorting to violence, everyone in the locality should shun them. While Parnell's speech did not refer to land agents or landlords, the tactic was first applied to Boycott when the alarm was raised about the evictions. Despite the short-term economic hardship to those undertaking this action, Boycott soon found himself isolated – his workers stopped work in the fields and stables, as well as in his house. Local businessmen stopped trading with him, and the local postman refused to deliver mail.

The concerted action taken against him meant that Boycott was unable to hire anyone to harvest his crops in his charge. After the harvest, the "boycott" was successfully continued and soon the new word was everywhere. The New-York Tribune reporter, James Redpath, first wrote of the boycott in the international press. The Irish author, George Moore, reported: 'Like a comet the verb 'boycott' appeared.' It was used by The Times in November 1880 as a term for organized isolation. According to an account in the book The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland by Michael Davitt, the term was promoted by Fr. John O'Malley of County Mayo to "signify ostracism applied to a landlord or agent like Boycott". The Times first reported on November 20, 1880: "The people of New Pallas have resolved to 'boycott' them and refused to supply them with food or drink." The Daily News wrote on December 13, 1880: "Already the stoutest-hearted are yielding on every side to the dread of being 'Boycotted'." By January of the following year, the word was being used figuratively: "Dame Nature arose.... She 'Boycotted' London from Kew to Mile End."

Girlcott Girlcott, a pun on "boycott", is a boycott intended to focus on the rights or actions of women. The term was coined in 1968 by American Lacey O'Neal during the 1968 Summer Olympics in the context of protests by male African American athletes. The term was later used by retired tennis player Billie Jean King in 1999 in reference to Wimbledon, while discussing equal pay for women players. The term "girlcott" was revived in 2005 by the Women and Girls Foundation in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania against Abercrombie & Fitch. Although the term itself was not coined until 1880, the practice dates back to at least the 1790s, when supporters of the British abolitionists led and supported the free produce movement.Other instances include:

the Iranian Tobacco Boycott in 1891 Civil rights movement boycotts to protest segregation (e.g., Montgomery & Tallahassee Bus Boycotts) the United Farm Workers union grape and lettuce boycotts the American boycott of British goods during the American Revolution, such as the Boston Tea Party the 1905 Chinese boycott of American products to protest the extension of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1902. the Indian boycott of British goods organized by Mahatma Gandhi the successful Jewish boycott organized against Henry Ford in the United States, in the 1920s the boycott of Japanese products in China after the May Fourth Movement the antisemitic boycott of Jewish-owned businesses in Nazi Germany during the 1930s the Jewish anti-Nazi boycott of German goods in Lithuania, the US, Britain, Poland and Mandatory Palestine during 1933 the Arab League boycott of Israel and companies trading with Israel. the worldwide Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) campaign led by Palestinian civil society against the State of Israel. The global fossil fuel divestment movement, described by Desmond Tutu as an "apartheid-style boycott to save the planet", and considered to be the biggest boycott-style campaign in history. Redundant boycotts along more than one century against Catalan products by Spanish nationalism. Over the years, political/economic claims and self-government milestones, sometimes misrepresented as a secessionist revolt, have often been met with a call for a commercial boycott against Catalonia. This is the case of the creation of the Unió regionalista, the creation of Solidaritat catalana, the ¡Cu-Cut! incident, the Tragic Week (which is advertised as separatist so that it does not spread to other Spanish towns), creation of the Commonwealth of Catalonia in 1914, the participation of Catalan volunteers in the First World War and claim of the Wilson doctrine for Catalonia, the creation and campaign of the Regionalist League of Catalonia, in 1918, autonomy through the Statute of Núria, the Events of 6 October, or, more recently, the Statute of Miravet. More recently there have been other boycotts related to the expansion of Catalan sovereignty. During the 1973 oil crisis, the Arab countries enacted a crude oil embargo against the West. Other examples include the US-led boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow, the Soviet-led boycott of the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, and the movement that advocated "disinvestment" in South Africa during the 1980s in opposition to that country's apartheid regime. The first Olympic boycott was in the 1956 Summer Olympics with several countries boycotting the games for different reasons. Iran also has an informal Olympic boycott against participating against Israel, whereby Iranian athletes typically bow out or claim injuries when pitted against Israelis (see Arash Miresmaeili).

Academic boycotts have been organized against countries—for example, the mid- and late 20th-century academic boycotts of South Africa in protest of apartheid practices and the academic boycotts of Israel in the early 2000s. Boycotts are now much easier to successfully initiate due to the Internet. Examples include the gay and lesbian boycott of advertisers of the Dr. Laura talk show, gun owners' similar boycott of advertisers of Rosie O'Donnell's talk show and (later) magazine, and gun owners' boycott of Smith & Wesson following that company's March 2000 settlement with the Clinton administration. They may be initiated very easily using either websites (the Dr. Laura boycott), newsgroups (the Rosie O'Donnell boycotts), or even mailing lists. Internet-initiated boycotts "snowball" very quickly compared to other forms of organization Viral Labeling is a new boycott method using the new digital technology proposed by the Multitude Project and applied for the first time against Walt Disney around Christmas time in 2009. Some boycotts center on particular businesses, such as recent[when?] protests regarding Costco, Walmart, Ford Motor Company, or the diverse products of Philip Morris. Another form of boycott identifies a number of different companies involved in a particular issue, such as the Sudan Divestment campaign, the "Boycott Bush" campaign. The Boycott Bush website was set up by Ethical Consumer after U.S. President George W. Bush failed to ratify the Kyoto Protocol – the website identified Bush's corporate funders and the brands and products they produce. Historically boycotts have also targeted individual businesses. During the early decades of the twentieth century hotels in Australia were regularly targeted over the cost of alcohol, accommodation and food, as well as mistreatment of employees. Pope Francis refers to boycotting as a successful means of influencing businesses, "forcing them to consider their environmental footprint and their patterns of production".

As a response to consumer boycotts of large-scale and multinational businesses, some companies have marketed brands that do not bear the company's name on the packaging or in advertising. Activists such as Ethical Consumer produce information that reveals which companies own which brands and products so consumers can practice boycotts or moral purchasing more effectively. Another organization, Buycott.com, provides an Internet-based smart-phone application that scans Universal Product Codes and displays corporate relationships to the user.

"Boycotts" may be formally organized by governments as well. In reality, government "boycotts" are just a type of embargo. Notably, the first formal, nationwide act of the Nazi government against German Jews was a national embargo of Jewish businesses on April 1, 1933. Boycotts are legal under common law. The right to engage in commerce, social intercourse, and friendship includes the implied right not to engage in commerce, social intercourse, and friendship. Since a boycott is voluntary and nonviolent, the law cannot stop it. Opponents of boycotts historically have the choice of suffering under it, yielding to its demands, or attempting to suppress it through extralegal means, such as force and coercion.

In the United States, the antiboycott provisions of the Export Administration Regulations (EAR) apply to all "U.S. persons", defined to include individuals and companies located in the United States and their foreign affiliates. The antiboycott provisions are intended to prevent United States citizens and companies being used as instrumentalities of a foreign government's foreign policy. The EAR forbids participation in or material support of boycotts initiated by foreign governments, for example, the Arab League boycott of Israel. These persons are subject to the law when their activities relate to the sale, purchase, or transfer of goods or services (including the sale of information) within the United States or between the United States and a foreign country. This covers exports and imports, financing, forwarding and shipping, and certain other transactions that may take place wholly offshore.[41]

However, the EAR only applies to foreign government initiated boycotts: a domestic boycott campaign arising within the United States that has the same object as the foreign-government-initiated boycott appears to be lawful, assuming that it is an independent effort not connected with the foreign government's boycott.

Other legal impediments to certain boycotts remain. One set are refusal to deal laws, which prohibit concerted efforts to eliminate competition by refusal to buy from or to sell to a party.[42] Similarly, boycotts may also run afoul of anti-discrimination laws; for example, New Jersey's Law Against Discrimination prohibits any place that offers goods, services and facilities to the general public, such as a restaurant, from denying or withholding any accommodation to (i.e., not to engage in commerce with) an individual because of that individual's race (etc.).[43]

Alternatives

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) A boycott is typically a one-time affair intended to correct an outstanding single wrong. When extended for a long period of time, or as part of an overall program of awareness-raising or reforms to laws or regimes, a boycott is part of moral purchasing, and some prefer those economic or political terms. Most organized consumer boycotts today are focused on long-term change of buying habits, and so fit into part of a larger political program, with many techniques that require a longer structural commitment, e.g. reform to commodity markets, or government commitment to moral purchasing, e.g. the longstanding boycott of South African businesses to protest apartheid already alluded to. These stretch the meaning of a "boycott."

Another form of consumer boycotting is substitution for an equivalent product; for example, Mecca Cola and Qibla Cola have been marketed as substitutes for Coca-Cola among Muslim populations.

A prime target of boycotts is consumerism itself, e.g. "International Buy Nothing Day" celebrated globally on the Friday after Thanksgiving Day in the United States.

Another version of the boycott is targeted divestment, or disinvestment. Targeted divestment involves campaigning for withdrawal of investment, for example the Sudan Divestment campaign involves putting pressure on companies, often through shareholder activism, to withdraw investment that helps the Sudanese government perpetuate genocide in Darfur. Only if a company refuses to change its behavior in response to shareholder engagement does the targeted divestment model call for divestment from that company. Such targeted divestment implicitly excludes companies involved in agriculture, the production and distribution of consumer goods, or the provision of goods and services intended to relieve human suffering or to promote health, religious and spiritual activities, or education.

When students are dissatisfied with a political or academic issue, a common tactic for students' unions is to start a boycott of classes (called a student strike among faculty and students since it is meant to resemble strike action by organized labor) to put pressure on the governing body of the institution, such as a university, vocational college or a school, since such institutions cannot afford to have a cohort miss an entire year.

Sports events Further information: List of Olympic Games boycotts The 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin were held after the Nazis rose to power three years prior. Despite advocacy from numerous officials and activists, no country boycotted the games, although the United States was close to it. In the 1970s and 1980s South Africa became the target of a sports boycott. After the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, the United States led a 66-nation boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics much to Soviet chagrin. The USSR then organized an Eastern Bloc boycott of the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, which allowed the Americans to win far more medals than expected.

In at least one case, a boycott has been documented due to on-field results of a game; the residents of New Orleans boycotted television broadcasts of Super Bowl LIII after a controversial officiating call led to the hometown New Orleans Saints losing the NFC Championship Game and being denied a trip to the Super Bowl. Viewership of the game dropped in the city by half compared to Super Bowl LII, contributing to a noticeable drop in the overall national ratings, but the boycott failed to achieve any meaningful remedy for the Saints or their fans.

Diplomatic boycott Nations have from time to time used "diplomatic boycotts" to isolate other governments. Following the May Coup of 1903, Great Britain led the major powers in a diplomatic boycott against Serbia, which was a refusal to recognize the post-coup government of Serbia altogether by withdrawing ambassadors and other diplomatic officials from the country; it ended three years later in 1906, when Great Britain renewed diplomatic relations through a decree signed by King Edward VII.

A diplomatic boycott is when diplomatic participation is withheld from an event such as the Olympics but athletic participation is not limited. In 2021, a number of Western nations, led by the United States, Britain and Canada, protested the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics through a diplomatic boycott, citing China's policies concerning the persecution of Uyghurs and human rights violations in the country.

Where the target of a boycott derives all or part of its revenues from other businesses, as a newspaper does, boycott organizers may address the target's commercial customers.

Collective behavior The sociology of collective behavior is concerned with causes and conditions pertaining to behavior carried out by a collective, as opposed to an individual (e.g., riots, panics, fads/crazes, boycotts). Boycotts have been characterized by some as different from traditional forms of collective behavior in that they appear to be highly rational and dependent on existing norms and structures. Lewis Killian criticizes that characterization, pointing to the Tallahassee bus boycott as one example of a boycott that aligns with traditional collective behavior theory.

Philip Balsiger points out that political consumption (e.g., boycotts) tends to follow dual-purpose action repertoires, or scripts, which are used publicly to pressure boycott targets and to educate and recruit consumers. Balsiger finds one example in Switzerland, documenting activities of the Clean Clothes Campaign, a public NGO-backed campaign, that highlighted and disseminated information about local companies' ethical practices.

Dixon, Martin, and Nau analyzed 31 collective behavior campaigns against corporations that took place during the 1990s and 2000s. Protests considered successful included boycotts and were found to include a third party, either in the capacity of state intervention or of media coverage. State intervention may make boycotts more efficacious when corporation leaders fear the imposition of regulations. Media intervention may be a crucial contributor to a successful boycott because of its potential to damage the reputation of a corporation. Target corporations that were the most visible were found to be the most vulnerable to either market (protest causing economic loss) or mediated (caused by third-party) disruption. Third-party actors (i.e., the state or media) were more influential when a corporation had a high reputation—when third-party activity was low, highly reputable corporations did not make the desired concessions to boycotters; when third-party activity was high, highly reputable corporations satisfied the demands of boycotters. The boycott, a prima facie market-disruptive tactic, often precipitates mediated disruption. The researchers' analysis led them to conclude that when boycott targets are highly visible and directly interact with and depend on local consumers who can easily find substitutes, they are more likely to make concessions. Koku, Akhigbe, and Springer also emphasize the importance of boycotts' threat of reputational damage, finding that boycotts alone pose more of a threat to a corporation's reputation than to its finances directly.

Philippe Delacote points out that a problem contributing to a generally low probability of success for any boycott is the fact that the consumers with the most power to cause market disruption are the least likely to participate; the opposite is true for consumers with the least power. Another collective behavior problem is the difficulty, or impossibility, of direct coordination amongst a dispersed group of boycotters. Yuksel and Mryteza emphasize the collective behavior problem of free riding in consumer boycotts, noting that some individuals may perceive participating to be too great an immediate personal utility sacrifice. They also note that boycotting consumers took the collectivity into account when deciding to participate, that is, consideration of joining a boycott as goal-oriented collective activity increased one's likelihood of participating. A corporation-targeted protest repertoire including boycotts and education of consumers presents the highest likelihood for success. Boycotts are generally legal in developed countries. Occasionally, some restrictions may apply; for instance, in the United States, it may be unlawful for a union to engage in "secondary boycotts" (to request that its members boycott companies that supply items to an organization already under a boycott, in the United States);however, the union is free to use its right to speak freely to inform its members of the fact that suppliers of a company are breaking a boycott; its members then may take whatever action they deem appropriate, in consideration of that fact.

United Kingdom When the boycott first emerged in Ireland, it presented a serious dilemma for Gladstone's government. The individual actions that constituted a boycott were recognized by legislators as essential to a free society. However, overall a boycott amounted to a harsh, extrajudicial punishment. The Prevention of Crime (Ireland) Act 1882 made it illegal to use "intimidation" to instigate or enforce a boycott, but not to participate in one.

The conservative jurist James Fitzjames Stephen justified laws against boycotting by claiming that the practice amounted to "usurpation of the functions of government" and ought therefore to be dealt with as "the modern representatives of the old conception of high treason

0 notes