#Caesar Baronius

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Saints&Reading:Tuesday, June 20, 2023

june 20_june 7

THE HOLY WOMEN MARTYRS KALERIA (VALERIA), KYRIAKE and MARIA (304)

St Kiriake

The holy women martyrs Kyriake, Kaleria (Valeria), and Mary lived in Palestinian Caesarea during the persecution under Diocletian (284-305). Having received instruction in the Christian Faith, they abandoned paganism, settled in a solitary place, and spent their lives in prayer, beseeching the Lord that the persecution against Christians would come to an end and that the Faith of Christ would shine throughout all the world.

St Maria

The governor tried to force them to worship idols, but they bravely confessed their faith in Christ. For this reason, they were tortured and received the crown of martyrdom.

Saint Kaleria

Saint Zēnaίda

There is very little information about Saint Zēnaίda, except that she was born in 284 Caesarea of Palestine and found worthy of the charism of working miracles. She ended the course of her life with a martyric death.

The Byzantine Synaxarion mentions that Saint Zēnaίda's veneration was widespread in Constantinople, where her Synaxis took place on June 6 at a church dedicated to her in the Basilisk district.

Several hagiographic sources mention the name of Saint Zēnaίda. Among them, a Neapolitan calendar of the IX century (June 7); a printed Greek Menaion (Venice, 1591; and the Synaxaristes of Saint Νikόdēmos of the Holy Mountain.

In the Roman Martyrology of Cardinal Caesar Baronius, Zēnaίda is mistakenly listed under June 5 with the martyrs Valeria, Kyriakḗ, and Maria.

ROMANS 7:14-8:2

14 We know the law is spiritual, but I am carnal, sold under sin. 15 For what I am doing, I do not understand. What I will do, that I do not practice; but what I hate, that I do. 16 If I do what I will not do, I agree with the law that it is good. 17 I no longer do it, but sin dwells in me. 18 For I know that in me (that is, in my flesh) nothing good dwells; for to will is present with me, but how to perform what is good I do not find. 19 For the good that I will to do, I do not do; but the evil I will not to do, that I practice. 20 Now, if I do what I will not do, it is no longer I who do it, but sin that dwells in me. 21 I find a law that evil is present with me, the one who wills to do good. 22 For I delight in the law of God according to the inward man. 23 But I see another law in my members, warring against the law of my mind, and bringing me into captivity to the law of sin in my members. 24 O wretched man that I am! Who will deliver me from this body of death? 25 I thank God through Jesus Christ our Lord! So then, with the mind, I serve the law of God, but with the flesh, the law of sin.

1 There is no condemnation to those in Christ Jesus, who do not walk according to the flesh, but according to the Spirit. 2 For the law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus has made me free from the law of sin and death.

MATTHEW 10:9-15

9 Provide neither gold nor silver nor copper in your money belts, 10 nor bag for your journey, nor two tunics, nor sandals, nor staffs; for a worker is worthy of his food. 11 Now whatever city or town you enter, inquire who in it is worthy, and stay there till you go out. 12 When you enter a household, greet it. 13 If the family is worthy, let your peace come upon it. But if it is not worthy, let your peace return to you. 14 And whoever will not receive you nor hear your words, shake off the dust from your feet when you depart from that house or city. 15 Assuredly, I say to you, it will be more tolerable for the land of Sodom and Gomorrah on the day of judgment than for that city!

#orthodoxy#orthodoxchristianity#easternorthodoxchurch#originofchristianity#spirituality#holyscriptures#gospel#bible

13 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Je suis très heureux d’avoir fait l’acquisition — à très bon prix — d’un livre désormais très rare et difficile à obtenir. Il s’agit de l’ouvrage historique et biographique de Marie-Claire Daveluy, intitulé : « Jeanne Mance (1606-1673), suivi d’un essai généalogique sur les Mance et les de Mance ». [1] Je possédais déjà — depuis plus de vingt ans — son ouvrage « La Société de Notre-Dame de Montréal » [2] qui inclut le texte complet des « Véritables motifs de messieurs et dames de la Société de Notre-Dame de Montréal pour la conversion des sauvages de la Nouvelle-France ». [3] Il s’agit de deux œuvres importantes en ce qui a trait à l’histoire de Montréal, et qui sont malheureusement trop souvent oubliées.

Pourquoi ma dernière acquisition est-elle si importante pour moi ? Tout d’abord parce que ce livre fut l’une de mes premières rencontres avec Mlle Jeanne Mance, la co-fondatrice de Montréal (Ville-Marie), qui fut discrètement choisie en 1639 par le roi de France et le cardinal de Richelieu pour accomplir une mission spirituelle en Nouvelle-France. En effet on y apprend qu’en 1639, les Langrois virent paraître sous leurs murs Louis XIII et le cardinal de Richelieu. Peu de temps après, le 30 mai 1640, elle partit pour Paris afin de rencontrer le père Charles Lalemant qui a vécu huit ans en Nouvelle-France et qui gère maintenant les affaires du Canada.

Elle fait alors la connaissance d’Angélique de Bullion, riche veuve d’un surintendant des finances, qui veut établir un hôpital au Canada dans un lieu à déterminer. Jeanne accepte de mener à bien ce projet. Mme de Bullion souhaite cependant rester dans l’ombre. C’est Charles Rapine, un de ses parents, qui sera son intermédiaire auprès de Jeanne. Le baron Gaston de Renty veillera pour sa part à la gestion des fonds pour l’hôpital.

Au printemps 1641, Jeanne se rend à La Rochelle où une flotte doit partir pour la Nouvelle-France. Elle fait la rencontre de Jérôme Le Royer de La Dauversière qui a créé, avec le soutien financier de Pierre Chevrier, baron de Fancamp, la Société Notre-Dame de Montréal, afin de fonder une colonie dans l’île de Montréal. Le chef de l’expédition a déjà été choisi : Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve. Nous voyons donc que les événements se sont déroulés très rapidement pour cette jeune provinciale. Y a-t-il une raison particulière qui fait de Jeanne Mance la figure de proue de l’évangélisation en Nouvelle-France ?

Nous apprenons encore dans le livre de Marie-Claire Daveluy que l’origine du patronyme Mance en France serait à rapprocher de quelque nom topographique. Il existe en Lorraine, dans le département de Meurthe-et-Moselle, canton de Briey, une commune appelée Mance (« Alis-mantia », c’est-à-dire la rivière aux eaux blanchâtres ou boueuses), et non loin de là, à Anoux, un hameau appelé Mancieulles; pour la commune, on trouve les formes anciennes Manis, Meinis (XIIIe s.). Pas loin de là, à Ars-en-Moselle, Mance dénomme encore une ferme et un moulin : de ce lieu, sous le nom de Notre-Dame de Mance, fait mention une chronique du XVe siècle. Mance désigne encore le ru de Mance, affluent de l’Orne et sous-affluent de la Moselle, qui arrose Mance et Mancieulles, et un autre ru de Mance, qui passe à Gravelotte et au moulin de Mance, rapporté à l’instant, et se jette dans la Moselle à Ars.

Dans une lettre datée du 6 décembre 1933, Jacques Laurent explique : « Le premier de ces ruisseaux, qui se jette dans l’Orne à Aubone, est appelé au XIIe siècle Amantia, et cette forme est très intéressante : elle permet de conjecturer avec une extrême vraisemblance, que les autres Mance sont des formes à apocope, et que Mance peut être rattaché au genre, étendu, des hydronymes et toponymes, représentés par le vocable principal Alismantia qui a désigné tant de cours d’eau, notamment dans l’Est de la France (Armance, Armançon, Amanse, Manson, etc.), et ça et là dans le Centre (Aumance) et le Midi (Amosson). Un ouvrage explique Alismantia par la combinaison d’un suffixe avec la racine rendant le sens d’une essence végétale particulièere, : l’alisier, alisa. » Le Pr Pierre Gastal nous dit que Alismantia est un « hydronyme ligure de sens inconnu que l’on retrouve dans Aumance, Armance, Amance, etc. » [4] Dans l’introduction à son édition des chartes de Montier-en-Der, l’abbé Lalore écrivait : « L’abbaye de Montiérender est désignée dans nos plus anciens documents “in vasta, in saltu Dervensi, super Vigera et Alsmantia, in pago Pertense”, c’est-à-dire dans la solitude, la forêt du Der, sur la Voire et l’Aumance, dans le comté de Perthois. » [5]

#gallery-0-4 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-4 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 100%; } #gallery-0-4 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-4 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Relique présumée (tibia) de Marie-Madeleine – Détail du reliquaire de Sainte-Baume dans le Var, où l’on voit Marie-Madeleine transportant un corps entouré de bandelettes vers le port de Marseille (Massalia).

La Légende Dorée et Joseph d’Arimathie

Vitrail représentant Joseph d’Arimathie tenant le Graal à l’église St John, Glastonbury

Il y a de cela trente ans, j’avais déjà noté que le vocable Alismantia duquel dérive le nom de Mance est tout-à-fait similaire au vocable Alimathie duquel dérive — selon certains auteurs — le nom de Joseph d’Arimathie, un notable juif, membre du Sanhédrin, qui procèda à la descente de croix et à l’inhumation de Jésus. La tradition provençale, appuyée par un écrit de Raban Maur, évêque de Mayence au IXe siècle, inclut ce personnage dans l’arrivée miraculeuse des amis du Seigneur sur la côte provençale, dans le sud de la France. Plusieurs disciples vinrent partager le sort de Marie Madeleine et Lazare : les deux “soeurs” Marie Jacobé, mère de Jacques le Mineur, Marie Salomé, mère des apôtres Jacques et Jean, Maximin, Sidoine l’aveugle, et Joseph d’Arimathie « qui avait emporté le calice avec lequel le Christ célébra sa dernière Cène et dans lequel il recueillit son sang sur la croix » : le Saint Graal. [6]

Chassés de Palestine et placés dans « un vaisseau de pierre » sans voile ni rame, ils furent poussés par les courants vers le delta du Rhône où ils s’échouèrent. Là, ils furent accueillis par Sarah la noire, qui devint la servante des Maries. Seules resteront sur place Marie Salomé, Marie Jacobé et Sarah. Elles y moururent, et l’endroit où elles furent ensevelies, traditionnellement situé aux Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, devint un important lieu de culte et de pèlerinage chrétien ainsi qu’une halte sur le chemin de Saint-Jacques-de-Compostelle, fils de Marie Salomé. Marie Madeleine se retira dans le massif de la Sainte-Baume, Lazare devint le premier évêque de Marseille, Maximin, celui d’Aix et Sidoine, celui du Tricastin, tandis que Marthe s’en fut à Tarascon, où, d’après la légende, elle terrassa la terrible Tarasque.

Cette pérégrination est aussi racontée par le dominicain et archevêque de Gênes, Jacques de Voragine (~1228-1298), dans sa Légende dorée, un ouvrage rédigé en latin entre 1261 et 1266.

La figure de Joseph d’Arimathie est introduite dans le cycle arthurien par Robert de Boron dans son roman en vers « Estoire dou Graal ou Joseph d’Arimathie », écrit entre 1190 et 1199. Joseph conserve le vase de la Cène, dans lequel il recueille un peu du sang de Jésus, avant de le déposer dans son sépulcre. Jeté en prison par les autorités juives, privé de nourriture, il doit la vie à la seule contemplation du Graal. Après douze ans d’emprisonnement, l’empereur Vespasien le fait libérer. Joseph, muni de la Sainte Lance et du Saint-Graal, quitte alors la Palestine et se rend en Occident jusqu’en Grande-Bretagne, à Glastonbury selon certains textes. Le cardinal Caesar Baronius (1538-1607), bibliothécaire et historien du Vatican, a enregistré ce voyage de Joseph d’Arimathie, Lazare, Marie-Madeleine, Marthe, Marcella et autres dans ses Annales ecclesiastici. [7] En voici une traduction approximative à partir du latin :

« Et Ananias, un disciple de la dispersion est allé à Damas, à peu près à ce moment, où il a rassemblé l’Église. De plus, nous pouvons aussi rattacher cela au temps de Lazare, Marie-Madeleine, Marthe, Marcella et le fidèle serviteur, sur lesquels s’était enflammé la haine des Juifs et qui furent chassés de Jérusalem avec le disciple Maximin. Ils embarquèrent sur un bateau sans rame, sur une mer tumultueuse. On dit que la divine providence les débarquèrent à Marseille. Joseph d’Arimathie, un homme noble en danger accompagné d’un officier subalterne, mirent les voiles de la Gaule jusqu’à la Grande-Bretagne, et là, ils ont proclamé l’Évangile du jour. Cependant, chacun est capable d’un certain nombre de méthodes pour compter le fruit de la prédication de l’assemblée. En fait, même si la porte de l’Évangile était encore fermée aux païens, cependant, ses confrères juifs annonçaient qu’il était libre, d’où Luc nous dit : « Ils partirent, et ils allèrent de village en village, annonçant la bonne nouvelle. »

Avant que le cardinal Caesar Baronius ne soit nommé bibliothécaire du Vatican en 1597, il avait accès à du matériel et à des sources dans ses archives qui étaient auparavant inédits ou inutilisés. Il les a utilisés dans le développement de son travail. En conséquence, la documentation des Annales Ecclesiastici est considérée par la plupart comme extrêmement utile et complète. [8] Lord Acton l’a appelé « la plus grande histoire de l’Église jamais écrite ». Mort en odeur de sainteté, les travaux du Vénérable Caesar Baronius peuvent donc être pris très au sérieux. Dans ce cas, le voyage de Marie-Madeleine et de ses compagnons vers le delta du Rhône et Marseille est certainement plus qu’une simple légende.

La France semble avoir conservé le souvenir de Joseph d’Arimathie dans ses hydronymes et toponymes, dans le Midi (Amosson), dans la Drôme (Le Manson), dans l’Est de la France (Armance, Armançon, Amanse, Manson, etc.), dans la Haute-Marne (Le Haut Manson), dans le Centre (Aumance), jusqu’en Grande-Bretagne où il s’installa à Glastonbury pour y fonder la première Église d’Angleterre. De ce vocable « Alismantia », j’émet donc l’hypothèse que le sang de Joseph d’Arimathie coulait dans les veines de Jeanne Mance, ce qui expliquerait en grande partie la mission spirituelle qui lui était impartie et qui fut auréolée de mystère. J’y reviendrai éventuellement dans un prochain ouvrage qui sera consacré au périple du Saint Graal, de l’Ancienne Europe et au-delà, jusqu’à Ville-Marie en Nouvelle-France.

youtube

À propos de Marie-Claire Daveluy

Marie-Claire Daveluy (1880-1968)

Louise Bienvenue écrit : « Qui se souvient aujourd’hui de Marie-Claire Daveluy et de sa « plume d’historienne » ? Les passants qui traversent le petit parc nommé en son honneur, au nord-est de Montréal, ignorent probablement tout de cette femme de lettres qui vécut de 1880 à 1968 et qui œuvra sur plusieurs fronts : bibliothécaire, enseignante, romancière et historienne. [9] Pourtant, Daveluy était une personnalité reconnue de son temps : deux fois récipiendaire du prestigieux prix David (1924, 1934), elle reçut également un prix de l’Académie française (1934), un doctorat honoris causa de l’Université de Montréal (1943) et fut décorée de la Médaille du centenaire de la Société historique de Montréal (1958). » [10]

Marie-Claire Daveluy (née le 15 août 1880 à Montréal, morte le 21 janvier 1968 à Montréal) est une bibliothécaire, historienne, et écrivaine québécoise. Elle est surtout reconnue pour ses romans pour la jeunesse où elle marie histoire canadienne et fiction d’aventure.

Elle est la fille de Georges Daveluy et de Maria Lesieur Desaulniers et la petite-fille de Louis Léon Lesieur Désaulniers. Elle fait des études au couvent d’Hochelaga à Montréal.

En 1917, elle est la première femme membre de la Société historique de Montréal. « À cette époque, devenir membre de cette société savante n’était pas le moindre des accomplissements. L’histoire comme discipline universitaire n’en étant qu’à ses balbutiements et c’est grâce à de tels regroupements d’érudits que circulaient les connaissances archivistiques et méthodologiques. » [11] Passionnée d’archives, elle publie au cours de sa vie plusieurs romans et écrits historiques dont une histoire de Jeanne Mance qui reçoit le prix David et de l’Académie française en 1934. S’ajoutent à ses écrits historiques des pièces de théâtre et de nombreux écrits publiés dans des périodiques comme La Bonne Parole, L’Action Française et La Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française.

De 1917 à 1920, elle étudie à l’université McGill où elle reçoit un diplôme en bibliothéconomie en 1920. À la Bibliothèque municipale de Montréal, elle est bibliothécaire adjointe de 1920 à 1943 et chef de catalogue de 1930 à 1941. En 1937, elle est co-fondatrice, avec Aegidius Fauteux, Émile Deguire, Paul-Aimé Martin, de l’École de bibliothécaires de l’Université de Montréal. Elle est directrice générale de cette école de 1942-1953. En 1943, elle participe à la fondation de l’Association canadienne des bibliothécaires de langue française.

Elle est la première écrivaine québécoise de littérature jeunesse. Son œuvre marque l’avènement tardif de la littérature jeunesse au Québec. En 1921, elle publie le premier roman québécois écrit spécifiquement à l’intention des enfants, « Les Aventures de Perrine et Charlot ». L’œuvre paraît au départ comme un feuilleton de commande dans « L’Oiseau Bleu », une revue créée pour les jeunes par la Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste. Ce premier récit, à l’écriture novatrice, raconte l’histoire de deux orphelins français embarqués clandestinement pour la Nouvelle-France.

Publié sous forme de livre en 1923, ce premier titre sera suivi de cinq autres mettant en scène ces mêmes personnages et qui paraîtront jusqu’en 1940.Pendant des décennies, on considère la saga de Perrine et Charlot comme un modèle à suivre, que ce soit pour la présentation des enfants comme des héros modèles, forts des valeurs canadiennes-françaises de vertu et de piété, ou pour la « moralité parfaite et [la] haute élévation » qu’on lui accorde.

Plusieurs autres titres pour la jeunesse dont des contes de fées seront publiés pendant la même période. L’objectif est autant d’édifier, de vulgariser des connaissances historiques que de divertir. On y défend l’idéal français à une époque où l’influence du cinéma et des magazines américains est grandissante. Ces ouvrages, qui conviennent aux instances gouvernementales autant qu’au clergé, seront largement diffusés. Sa sépulture est située dans le Cimetière Notre-Dame-des-Neiges, à Montréal.

La sépulture de Marie-Claire Daveluy (1880-1968), dans le cimetière Notre-Dame-des-Neiges (R861), Montréal.

Louise Bienvenue écrit sur le site internet HistoireEngagee.ca : « Bien que Marie-Claire Daveluy fut reconnue en son temps comme « un historien vraiment érudit », elle n’a pourtant laissé qu’une faible empreinte dans notre mémoire historiographique. Lorsque son nom est évoqué de nos jours, c’est le plus souvent pour témoigner de son rôle de pionnière dans le domaine de la littérature de jeunesse ou pour reconnaître ses contributions au monde de la bibliothéconomie. Une partie du silence qui entoure sa carrière d’historienne s’explique probablement par le fait que Daveluy n’a jamais bénéficié d’un ancrage institutionnel (chaire universitaire, dépôt d’archives important) lui servant de lieu légitime de production de l’histoire. Ses conditions d’écriture étaient donc bien différentes de plusieurs de ses contemporains des milieux historique et archivistique avec qui elle était en rapport : Lionel Groulx, Édouard-Zotique Massicotte, Pierre-Georges Roy, Olivier Maurault, Gérard Malchelosse, Albert Tessier, Aegidius Fauteau, Sœur Maria Mondoux et Marcel Trudel, par exemple. »

La professeure titulaire au Département d’histoire de l’Université de Sherbrooke termine son article ainsi : « Pendant cinq décennies, la femme de lettres devait rester fidèle à cet engagement en s’imposant comme une rigoureuse disciple de Clio. Cent ans plus tard, on peut lui reconnaître à bon droit un rôle de pionnière en tant que femme dans le domaine de la pratique historienne. »

__________________

RÉFÉRENCES ET NOTES :

Marie-Claire Daveluy : Jeanne Mance, 1606-1673, suivi d’un Essai généalogique sur les Mance et les De Mance, par M. Jacques Laurent, ancien élève de l’École des chartes et auxiliaire de l’Institut, 2e éd., Montréal, Fides, 1962 [1934].

Marie-Claire Daveluy : La Société de Notre-Dame de Montréal, 1639-1663 : son histoire — ses membres — son manifeste. Montréal, Fides, 1965. 553 p.

[1643] — Les véritables motifs de messieurs et dames de la Société de Notre-Dame de Montréal pour la conversion des sauvages de la Nouvelle-France. Publié en 1880.

Pr Pierre Gastal : « Étymologie des cours d’eau de la Drôme: Le Manson ». Lieux et Rivières de France.

Abbé Charles Lalore : « Cartulaire de l’abbaye de la Chapelle-aux-Planches. Chartes de Montiérender, de Saint-Etienne et de Toussaints de Châlons, d’Andecy, de Beaulieu et de Rethel », Paris-Troyes, 1878 (Collection des principaux cartulaires du diocèse de Troyes, IV), p. XX [cité Lalore] : « Domno sacro sancte basilice S. Petri, id est monasterio in Dervo constructe in pago Pertense super fluvium Vigera et Alismantia, quod donnus Bercharius edificavit » (Le cartulaire de Montier-en-Der, 666-1129).

Joseph Gazay : « Étude sur les légendes de sainte Marie-Madelaine et de Joseph d’Arimathie ». Annales du Midi, année 1939. 51-201, pp. 5-36 et 51-203, pp. 225-284.

Mgr Caesar Baronius : « Annales ecclesiastici a Christo nato ad annum 1198 ». Tome Premier. Barri-Ducis, Ludovicus Guérin. Paris-Bruxelles, 1864. Jesu Christi Annus 35, page 208 : « Hac ipsa dispersione Ananias discipulus profectus Damascum, collegit Ecclesiam. Insuper colligere possumus , hoc quoque tempore Lazarum , Mariam Magdalenam , Martham , et Marcellam pedissequam , in quos Jud��i majori odio exardescebant, non tantum Hierosolymis pulsos esse, sed una cum Maximino discipulo , navi absque remigio impositos , in certum periculum mari fuisse creditos ; quos divina providentia Massiliam tradunt appulisse , comitemque ferunt ejusdem discriminis Josephum ab Arimathæa nobilem decurionem, quem tradunt ex Gallia in Britanniam navigasse , illicque post prædicatum Evangelium diem clausisse extremum. Sed quis valeat singulorum hic recensere vias, et fructus numerare ex prædicatione collectos? Nam etsi nondum Gentibus reseratum erat ostium Evangelii , tamen contribulibus Judæis illud annuntiare liberum erat, unde et Lucas : “Igitur, inquit, qui dispersi erant, pertransibant evangelizantes verbum Dei.” »

Annales Ecclesiastici (titre complet Annales ecclesiastici a Christo nato ad annum 1198 ; “Annales ecclésiastiques de la nativité du Christ à 1198”), composé de douze volumes in-folio, est une histoire des 12 premiers siècles de l’Église chrétienne. Les Annales ont été publiées pour la première fois entre 1588 et 1607. Cet ouvrage a fonctionné comme une réponse officielle aux Centuries de Magdebourg luthériennes. Dans ce travail, les théologiens de Magdebourg ont étudié l’histoire de l’Église chrétienne afin de démontrer comment l’Église catholique représentait l’Antéchrist et s’était écartée des croyances et des pratiques de l’Église primitive. À leur tour, les Annales ont pleinement soutenu les revendications de la papauté de diriger la véritable église unique.

C’est en 1987 que la Ville de Montréal a nommé ce parc en hommage à Daveluy. Pendant une courte période de temps, du début des années 1980 jusqu’en 1997, la Bibliothèque nationale du Québec a eu un pavillon nommé en reconnaissance de Marie-Claire Daveluy (au 125, rue Sherbrooke Ouest, à Montréal, dans l’ancienne École des Beaux-Arts). Lorsqu’un déménagement sur la rue Holt fut envisagé, l’institution n’a plus souligné sa mémoire. Jean-Sébastien Sauvé, « Le pavillon Marie-Claire-Daveluy de la Bibliothèque nationale du Québec », conférence présentée lors de la journée d’étude « Marie-Claire Daveluy », Maison Bellarmin, 29 septembre 2017.

Louise Bienvenue : Marie-Claire Daveluy (1880-1968), historienne des femmes. Histoire sociale/Social History, Vol. 51, No 104, novembre 2018, pp. 329-352.

Louise Bienvenue : Il y a cent ans, une première femme entrait à la Société historique de Montréal : Marie-Claire Daveluy (1880-1968). HistoireEngagee.ca, 18 décembre 2017.

« Jeanne Mance (1606-1673), suivi d’un essai généalogique sur les Mance et les de Mance », par l’historienne Marie-Claire Daveluy Je suis très heureux d'avoir fait l'acquisition — à très bon prix — d'un livre désormais très rare et difficile à obtenir.

#Alismantia#Amantia#Angélique de Bullion#Annales ecclesiastici#évangélisation#baron de Fancamp#biographique#Caesar Baronius#calice#Canada#Charles Lalemant#Christ#de Mance#essai#Gaston de Renty#généalogique#historique#Jacques de Voragine#Jacques le Mineur#Jérôme Le Royer de La Dauversière#Jeanne Mance#Joseph d’Arimathie#Lazare#Légende dorée#livre#Mance#Marie Jacobé#Marie Madeleine#Marie Salomé#Marie-Claire Daveluy

0 notes

Text

“…while it is important to acknowledge that the-rest-of-the-world was making huge strides in scientific advancement during this time, and that Europe and white people are not the entire world, nor responsible for all of human advancement, there was no such thing as the Dark Ages in Europe either.

…Hilariously, the idea of the ‘Dark Ages’ actually originated in the medieval period itself. Petrarch – the poet laureate of fourteenth-century Rome – was actually the originator of the idea that there was a period of stagnation that Europe was moving out of. Petrarch had a political axe to grind. He considered that any point at which Rome – where he lived and worked and had considerable sway – did not completely dominate the world was a BAD TIME. This is not an unbiased assessment of world history.

The actual phrase ‘Dark Ages’ itself derives from the Latin saeculum obscurum, which Caesar Baronius – a cardinal and Church historian – came up with around 1602. He applied the term exclusively to the tenth and eleventh centuries. However, and very significantly in his use of the term, Baronius was not decrying a state of scientific malaise, or a particularly turbulent political period – he’s talking about a lack of sources surviving from that time. Indeed, Baronius sees the cut off point for the dark ages to be the Gregorian reforms of 1046, following which we see a massive increase in surviving documentation.

…during the Carolingian Renaissance of the ninth century, we see a flurry of Latin writers emerge, and a lot of text copying. This drops off again until what we term the Twelfth-Century Renaissance – home to this blog’s favourite philosopher/proto-Kanye – Abelard. (Shout out to my boy.) However, when people use the term ‘Dark Ages’ now, they usually use it to talk about the entire millennium of the Medieval period, and they aren’t talking about source survival. They aren’t thinking ‘dark’ as in ‘occluded’, they are thinking ‘dark’ as in pejorative.

We can thank the Enlightenment historiography for the expansion of the idea that the medieval period was a bad dark time. Kant and Voltaire in particular liked to see themselves as a part of an ‘Age of Reason’ as opposed to what they saw as the ‘Age of Faith’ of the medieval period. To their way of thinking, any time that the Church was in power was a time of regressive thinking. The Middle Ages, then, was a dark time because it was so dominated by religion.

The first push back against the term dark ages began with the Romantics. After the, um, unpleasantness of the Reign of Terror, and the major cultural and environmental upheavals of the Industrial Revolution it became fashionable to look at the medieval period as a time of spiritual focus, and environmental purity.

Obviously this is a super-biased way of looking at the period – just like it was biased for Enlightenment thinkers to take one look at the primacy of the Church and declare an entire millennium to be bad. I mean, really what the Romantics were doing was just casting shade on the Enlightenment historiography because they felt like it inevitably led to the guillotine. But what can you do?

By the twentieth century historians had moved on from the idea pretty much completely. If you take the time to actually, you know, study the medieval period, it becomes very apparent very quickly that there was a tremendous amount of intensive thought happening. This is the era of Thomas Aquinas – a bad ass philosopher who will think you under the fucking table.

Of Hildegard of Bingen – who basically founded scientific natural history in the German speaking lands. Hell, like we talked about last week Rogerius and Giles of Corbeil were throwing it down for major medical advancement. There was a lot going on. On the real, without the contributions of medieval thinkers you would not get Galileo, Newton, or the Scientific Revolution. The medieval period was not a period of stagnation, it was a time of progress.

But it’s not just that the idea of a ‘Dark Ages’ makes no sense when you look at what incredible advancement was happening at the time, it also makes no sense because it implies that stuff was going really well under the Romans. We estimate that somewhere between thirty to forty percent of the population of Italian Rome were slaves. The Romans had total bans on human dissection, meaning that there was no real way for medicine to progress any further than it had by the time of collapse – a problem that medieval people didn’t have.

I mean even if you just want to make it about religion – the Roman Empire was Christian at the time of its collapse and had its heads of state worshipped as LITERAL GODS during the pagan era. Somehow every edgy motherfucker with a fedora is totally cool with this and thinks it is super reasonable though. Because ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. The Romans were not a bunch of really awesome people living a life of idealised rationality any more than medieval people were all ignorant savages living in fear of God.

Is there a time that historians use the term ‘Dark Ages’? Yeah, we do use it to talk about source survival rates. It’s not a term we use as a value judgment, however. We just mean that we don’t have a lot of evidence to go off of. By the same token – if we somehow move on to another electronic format without converting the way things are stored now, we could be moving into a theoretical Digital Dark Age, where historians in the future won’t be able to study what we are writing now. (And that would be a tragedy, because legit, I would kill to be a historian working on Donald Trump’s tweets in the year 2717.)

We’re now moving away from using the term Dark Ages at all, however, because of the frequency with which it is misinterpreted. I mean, if every basic motherfucker out there who never bothered to read God’s Philosophers (hat tip to James Hamman – this book is amazing) will insist on willfully misinterpreting us, we just ain’t gonna give them the ammo.

What it comes down to is that the medieval period was as vibrant as any other period of history. If you’re going to player hate, go ahead, but please don’t act like you know anything about either medieval or ancient history when you do. There is no period of rational supermen followed by ignorant monsters. There are just people doing their best in the circumstances.

- Eleanor Janega, “There’s no such thing as the ‘Dark Ages’, but OK.”

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Padre Rossa urged Philip to become a priest. Despite his reluctance, he obeyed his confessor’s advice and was ordained in 1551. His first years as a priest were largely devoted to hearing confessions, assisting at hospitals, and ministering to the dying. He lived at the hospital of San Girolamo della Carità. Meanwhile, seeing that disciples continued to gather around him, requests for help started to arrive. The leadership of the new Florentine church of Rome, San Giovanni dei Fiorentini, asked if his priests would take over their parish. Luckily, Philip was able to assign five priests to the parish, including Caesar Baronius, the future historian and cardinal. Philip’s priests worked as missionaries of Rome, preaching sermons in different churches every evening. This was a very novel idea at the time.

In 1556, the group read the letters of Saint Francis Xavier at their meetings. These letters filled many of them with overflowing zeal; they desired to give up everything and go to India as missionaries, including Philip. However, he went first to consult a holy Cistercian, Fra Agostino Ghettini, who listened to his story and told him to come back in a week. One week later, having prayed about it, Fra Agostino told him, “Rome will be your India.” As such, St. Philip redoubled his efforts to evangelize Rome. His ability to attract many vocations was due to his openhearted confidence: "Cast yourself into the arms of God” he told interested aspirants, “And be very sure that if He wants anything of you, He will fit you for the work and give you strength."

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lupercalia pt 1.

ILLUSTRATION BY LABROUSTE DEL., MARY EVANS PICTURE LIBRARY/ALAMY

Chthonic, Apotropaic, Purification, and Fertility

Lupercalia was an annual lustral festival observed in the city of Rome on 15 of Februarius (February). It is described by Plutarch in his 75 CE Romulus:

The Lupercalia, by the time of its celebration, may seem to be a feast of purification, for it is solemnised on the dies nefasti, or non-court days, of the month February, which name signifies purification, and the very day of the feast was anciently called Februata; but its name is equivalent to the Greek Lycaea; and it seems thus to be of great antiquity, and brought in by the Arcadians who came with Evander. Yet this is but dubious, for it may come as well from the wolf that nursed Romulus; and we see the Luperci, the priests, begin their course from the place where they say Romulus was exposed. But the ceremonies performed in it render the origin of the thing more difficult to be guessed at; for there are goats killed, then, two young noblemen's sons being brought, some are to stain their foreheads with the bloody knife, others presently to wipe it off with wool dipped in milk; then the young boys must laugh after their foreheads are wiped; that done, having cut the goats' skins into thongs, they run about naked, only with something about their middle, lashing all they meet; and the young wives do not avoid their strokes, fancying they will help conception and childbirth. Another thing peculiar to this feast is for the Luperci to sacrifice a dog.

There are many important elements to be discussed here, but first we must address a common misconception:

Lupercalia is not the pagan Valentine’s Day.

Pope Gelasius I abolished Lupercalia in 494 CE. There is much uncritical repeating of the myth that Valentine’s Day was instituted in its place, however there is no historical evidence to support this. Pope Gelasius’ letter 100, To Andromachus (found here, regrettably only in Latin), in which observance of Lupercalia is forbidden, makes no mention of Valentine whatsoever. Further, we do not know when celebration of St. Valentine’s martyrdom began, and it is not until 1380 that it is connected to romantic love by Chaucer’s Parlement of Foules.

But what about the love lottery? The first mention of a match-making lottery administered by the Luperci comes from Alban Butler’s 1756 Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Other Principal Saints (vol 2, FEBRUARY XIV.ST. VALENTINE, PRIEST AND MARTYR.): "To abolish the heathens lewd superstitious custom of boys drawing the names of girls, in honour of their goddess Februata Juno, on the fifteenth of this month, several zealous pastors substituted the names of saints in billets, given on this day."

This assertion from Butler is transposed from Henri Misson’s M. Misson's Memoirs and Observations in his Travels over England With some Account of Scotland and Ireland.[x] There has been as of yet no evidence found to suggest such a thing took place in Rome.

Nor was Lupercalia replaced with Candlemas. This idea comes from conjecture of Cardinal Caesar Baronius in C16 CE, suggesting that Lupercalia was replaced by the Feast of the Purification of the Virgin (Candlemas). This festival was never celebrated in Rome, however, and the forty-day interval between Christmas and Candlemas means it would have been celebrated no later than February 2.[x]

Lupercalia’s association with Valentine’s Day appears to be the result of a modern desire either to be titillated (Flagellation! Blood! Fertility!) or to provide any explanation at all to questions that we are unable to answer.

I will share my reading regarding the ritualistic importance of each element, the possible origin of the festival, and possible associated deities in an upcoming post.

Khaire 🐺💀🖤

Further reading:

Green, William M. (1931, January). Lupercalia in the Fifth Century. Retrieved from http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Journals/CP/26/1/Lupercalia*.html

#lupercalia#paganblr#strega#witchblr#hellenistic witch#hellenic witch#hellenistic pagan#valentines day#pagan#hekatean witch

83 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The actual phrase ‘Dark Ages’ itself derives from the Latin saeculum obscurum, which Caesar Baronius – a cardinal and Church historian – came up with around 1602. He applied the term exclusively to the tenth and eleventh centuries. However, and very significantly in his use of the term, Baronius was not decrying a state of scientific malaise, or a particularly turbulent political period – he’s talking about a lack of sources surviving from that time. Indeed, Baronius sees the cut off point for the dark ages to be the Gregorian reforms of 1046, following which we see a massive increase in surviving documentation.

There’s no such thing as the ‘Dark Ages’, but OK

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Saints of the Day – St Anatolia & Victoria (Died 250) Martyrs – Sisters who gave their lives for Christ.

Patronages – against earthquakes, against lightning, against severe weather, 18 cities. Anatolia was first mentioned in the De Laude Sanctorum composed in 396 by Victrice (Victricius), bishop of Rouen (330-409) and they are both mentioned together in the Martyrologium Hieronymianum under 10 July. The two saints appear in the famous mosaics of Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, at Ravenna (see image below – 22 martyrs shown offering their crowns of martyrdom to the Christ. ), between Saints Paulina and Christina. A Passio Saints Anatoliae et Audacis et Saint Victoriae of the 6th or seventh century, which added the name of Audax, was mentioned by Aldhelm (died 709) and Bede (died 735), who list the saints in their martyrologies. Caesar Baronius lists Anatolia and Audax under 9 July and Victoria under 23 December.

Saint Victoria and her sister Saint Anatolia are remembered as beautiful Catholic noble women who lived during the reign of Emperor Decius 249-251. They were promised in marriage to noble pagan men who were far from pleased at having heard that they were practising Catholics. Saint Victoria was initially content with marrying the pagan, as she hoped that she would be able to convert him but her sister refused to marry and convinced St Victoria to do the same. They both sought to devote their lives solely to God.

The noble pagan suitors both managed to strike a deal with Roman authorities that allowed them to imprison each sister in their respective houses, in order to hopefully convince them to denounce their faith. Both sisters responded by selling all of their possessions, giving all of their money to the poor and devoting themselves to God. Both sisters, during their imprisonment, converted all of the guards, maids and servants in their respective houses.

Needless to say, the suitors were both furious at the sister’s failure to denounce their faith and acts of converting the guards, maids, etc. Saint Anatolia’s suitor, Titus Aurelius, was furious and hired St Audace, to execute her. He initially locked her in a room with a venomous snake which failed to harm her. Upon seeing this, St Audace converted and was later martyred. Saint Anatolia’s suitor was violently angry and became her murderer himself, by stabbing her to death.

Saint Victoria’s suitor, Eugenius, soon heard of this murder of Anatolia but continued to try and convince Victoria to aposthasise. He went through periods of great kindness towards her followed with periods of extreme ill-treatment. Eventually he renounced his suite and stabbed her to death himself, in a fit of rage. According to legend, he was instantly struck with leprosy and died 6 days later eaten by worms.

The relics of Saint Victoria are enshrined in the church of Santa Vittoria in Metanano, Italy and the relics of Saint Anatolia, as well as those of Saint Audace, are enshrined in the Basilica of Saint Scholastica in Subiaco.

(via Saints of the Day - St Anatolia & Victoria (Died 250) Martyrs - Sisters who gave their lives for Christ)

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"The Bible teaches us how to go to Heaven, not how the heavens go." -Cardinal Caesar Baronius [1872×1102 pixels] via /r/QuotesPorn https://www.reddit.com/r/QuotesPorn/comments/9iry1x/the_bible_teaches_us_how_to_go_to_heaven_not_how/?utm_source=ifttt

1 note

·

View note

Text

There’s no such thing as the Dark Ages, but OK

As a very serious adult, with a respectable career and life, and a healthy ability to let petty shit slide, I spent much too much time last week arguing with strangers on the internet who believe in the myth of the Dark Ages.

The arguments in question focused on a massively inaccurate meme, which some observers of the group pointed out was originally supposed to be about knowledge loss after the burning of the Library of Alexandria, but which some very cool EDGE LORD had changed to be about ‘The Christian Dark Ages’. Please feast your eyes on it in all it’s massive wrongness:

This is, pretty obviously, a bunch of honkey bullshit and also massively incorrect, as many important scholars have noted. As a result, I spent hours of my life – which I will never get back - pointing out repeatedly that the ‘graph’ in question has nothing to do with reality, and arguing with non-experts about the medieval period.

For the most part – these people were well-meaning. Many pointed out that this was a very Euro-centric world view, and that Asia, Africa, and the Arab world were all making huge advancements in scientific and medical theory at this time. That is absolutely true. White people have never been the entire world. The Chinese had a massively advanced scientific culture by this time, for example, and had been holding it down with hermetically sealed research laboratories since the third century BCE. The Arab world, meanwhile was compiling treatises on eye surgery. Scientific advancement was something that was happening in this period. Europe is not the centre of the world.

Having said that, while it is important to acknowledge that the-rest-of-the-world was making huge strides in scientific advancement during this time, and that Europe and white people are not the entire world, nor responsible for all of human advancement, there was no such thing as the Dark Ages in Europe either.

While everything about the idea of the Dark Ages is incorrect, lets start off with the way the term was meant to be used. The totally ignorant graph above, unsurprisingly, is completely fucking off. Hilariously, the idea of the ‘Dark Ages’ actually originated in the medieval period itself. Petrarch – the poet laureate of fourteenth-century Rome - was actually the originator of the idea that there was a period of stagnation that Europe was moving out of. Petrarch had a political axe to grind. He considered that any point at which Rome – where he lived and worked and had considerable sway – did not completely dominate the world was a BAD TIME. This is not an unbiased assessment of world history.

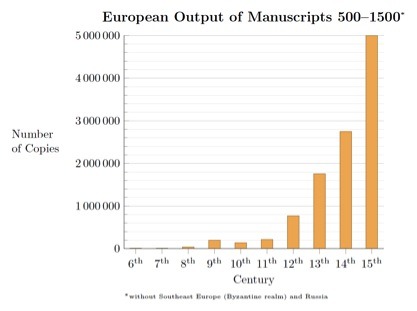

The actual phrase ‘Dark Ages’ itself derives from the Latin saeculum obscurum, which Caesar Baronius – a cardinal and Church historian - came up with around 1602. He applied the term exclusively to the tenth and eleventh centuries. However, and very significantly in his use of the term, Baronius was not decrying a state of scientific malaise, or a particularly turbulent political period – he’s talking about a lack of sources surviving from that time. Indeed, Baronius sees the cut off point for the dark ages to be the Gregorian reforms of 1046, following which we see a massive increase in surviving documentation. Witness an actual useful chart:

When we move into a period where there are more texts to be considered, Baronius argues, Europe moved out of the period of darkness and into a ‘new age’.*

Now this is some real talk. As you can tell from that graph, during the Carolingian Renaissance of the ninth century, we see a flurry of Latin writers emerge, and a lot of text copying. This drops off again until what we term the Twelfth-Century Renaissance – home to this blog’s favourite philosopher/proto-Kanye – Abelard. (Shout out to my boy.) However, when people use the term ‘Dark Ages’ now, they usually use it to talk about the entire millennium of the Medieval period, and they aren’t talking about source survival. They aren’t thinking ‘dark’ as in ‘occluded’, they are thinking ‘dark’ as in pejorative.

We can thank the Enlightenment historiography for the expansion of the idea that the medieval period was a bad dark time. Kant and Voltaire in particular liked to see themselves as a part of an ‘Age of Reason’ as opposed to what they saw as the ‘Age of Faith’ of the medieval period. To their way of thinking, any time that the Church was in power was a time of regressive thinking. The Middle Ages, then, was a dark time because it was so dominated by religion.

The first push back against the term dark ages began with the Romantics. After the, um, unpleasantness of the Reign of Terror, and the major cultural and environmental upheavals of the Industrial Revolution it became fashionable to look at the medieval period as a time of spiritual focus, and environmental purity. Obviously this is a super-biased way of looking at the period – just like it was biased for Enlightenment thinkers to take one look at the primacy of the Church and declare an entire millennium to be bad. I mean, really what the Romantics were doing was just casting shade on the Enlightenment historiography because they felt like it inevitably led to the guillotine. But what can you do?

By the twentieth century historians had moved on from the idea pretty much completely. If you take the time to actually, you know, study the medieval period, it becomes very apparent very quickly that there was a tremendous amount of intensive thought happening. This is the era of Thomas Aquinas – a bad ass philosopher who will think you under the fucking table. Of Hildegard of Bingen – who basically founded scientific natural history in the German speaking lands. Hell, like we talked about last week Rogerius and Giles of Corbeil were throwing it down for major medical advancement. There was a lot going on. On the real, without the contributions of medieval thinkers you would not get Galileo, Newton, or the Scientific Revolution. The medieval period was not a period of stagnation, it was a time of progress.

But it’s not just that the idea of a ‘Dark Ages’ makes no sense when you look at what incredible advancement was happening at the time, it also makes no sense because it implies that stuff was going really well under the Romans. We estimate that somewhere between thirty to forty percent of the population of Italian Rome were slaves. The Romans had total bans on human dissection, meaning that there was no real way for medicine to progress any further than it had by the time of collapse – a problem that medieval people didn’t have. I mean even if you just want to make it about religion - the Roman Empire was Christian at the time of its collapse and had its heads of state worshipped as LITERAL GODS during the pagan era. Somehow every edgy motherfucker with a fedora is totally cool with this and thinks it is super reasonable though. Because ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. The Romans were not a bunch of really awesome people living a life of idealised rationality any more than medieval people were all ignorant savages living in fear of God.

Is there a time that historians use the term ‘Dark Ages’? Yeah, we do use it to talk about source survival rates. It’s not a term we use as a value judgment, however. We just mean that we don’t have a lot of evidence to go off of. By the same token – if we somehow move on to another electronic format without converting the way things are stored now, we could be moving into a theoretical Digital Dark Age, where historians in the future won’t be able to study what we are writing now. (And that would be a tragedy, because legit, I would kill to be a historian working on Donald Trump’s tweets in the year 2717.)

We’re now moving away from using the term Dark Ages at all, however, because of the frequency with which it is misinterpreted. I mean, if every basic motherfucker out there who never bothered to read God’s Philosophers (hat tip to James Hamman – this book is amazing) will insist on willfully misinterpreting us, we just ain’t gonna give them the ammo.

What it comes down to is that the medieval period was as vibrant as any other period of history. If you’re going to player hate, go ahead, but please don’t act like you know anything about either medieval or ancient history when you do. There is no period of rational supermen followed by ignorant monsters. There are just people doing their best in the circumstances.

* Caesar Baronius, Annales Ecclesiastici Vol. X. (Rome, 1602), p. 647. "Novum incohatur saeculum quod, sua asperitate ac boni sterilitate ferreum, malique exudantis deformitate plumbeum, atque inopia scriptorum, appellari consuevit obscurum."

#dark ages#medieval#historiography#history#reason#arguing with people on the internet#history of science#history of philosophy

3K notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

"The Bible teaches us how to go to Heaven, not how the heavens go." -Cardinal Caesar Baronius [1872×1102 pixels]

0 notes

Text

Saints&Reading: Sun., May 24, 2020

Venerable Simeon the Stylite ( the younger)

Saint Simeon the Stylite was born in the year 521 in Antioch, Syria of pious parents John and Martha. From her youth Saint Martha (July 4) prepared herself for a life of virginity and longed for monasticism, but her parents insisted that she marry John. After ardent prayer in a church dedicated to Saint John the Forerunner, the future nun was directed in a vision to submit to the will of her parents and enter into marriage.

As a married woman, Saint Martha strove to please God and her husband in everything. She often prayed for a baby and promised to dedicate him to the service of God. Saint John the Forerunner revealed to Martha that she would have a son who would serve God. When the infant was born, he was named Simeon and baptized at two years of age.

When Simeon was six years old, an earthquake occurred in the city of Antioch, in which his father perished. Simeon was in church at the time of the earthquake. Leaving the church, he became lost and spent seven days sheltered by a pious woman. Saint John the Baptist again appeared to Saint Martha, and indicated where to find the lost boy. The saint’s mother found her lost son, and moved to the outskirts of Antioch after the earthquake. Already during his childhood the Lord Jesus Christ appeared several times to Saint Simeon, foretelling his future exploits and the reward for them.

The six-year-old child Simeon went into the wilderness, where he lived in complete isolation. During this time a light-bearing angel guarded and fed him. Finally, he arrived at a monastery, headed by the igumen Abba John, who lived in asceticism upon a pillar. He accepted the boy with love...keep reading OCA

St Vincent de Lérins

Personal life

Vincent of Lérins was born in Toulouse, Gaul[4] to a noble family, and is believed to be the brother of Lupus of Troyes.[3] In his early life he engaged in secular pursuits; it is unclear whether these were civil or military, though the term he uses, "secularis militia", may imply the latter. He entered Lérins Abbey on Île Saint-Honorat, where under the pseudonym Peregrinus he wrote the Commonitorium, c. 434, about three years after the Council of Ephesus.[5] Vincent defended calling Mary, mother of Jesus, Theotokos(God-bearer). This opposed the teachings of Patriarch Nestorius of Constantinople which were condemned by the Council of Ephesus.[4]Eucherius of Lyon called him a "conspicuously eloquent and knowledgeable" holy man.[6]

Gennadius of Massilia wrote that Vincent died during the reign of Roman Emperor Theodosius II in the East and Valentinian III in the West. Therefore, his death must have occurred in or before the year 450. His relics are preserved at Lérins.[7]. Caesar Baronius included his name in the Roman Martyrology but Louis-Sébastien Le Nain de Tillemont doubted whether there was sufficient reason. He is commemorated on 24 May.

Commonitory

Vincent wrote his Commonitory to provide himself with a general rule to distinguish Catholic truth from heresy, committing it to writing as a reference. It is known for Vincent's famous maxim: "Moreover, in the Catholic Church itself, all possible care must be taken, that we hold that faith which has been believed everywhere, always, by all."[8](p132)[9](p10) The currently accepted idea that Vincent was a semipelagian is attributed to a 17th-century Protestant theologian, Gerardus Vossius, and developed in the 17th century by Cardinal Henry Noris.[9](xxii) Evidence of Vincent's semipelagianism, according to Reginald Moxon, is Vincent's, "great vehemence against" the doctrines of Augustine of Hippo in Commonitory.[9](xxvii)

Semipelagianism

Semipelagianism was a doctrine of grace advocated by monks in and around Marseilles in Southern Gaul after 428. It aimed at a compromise between the two extremes of Pelagianism and Augustinism, and was condemned of heresy at the Second Council of Orange in 529 AD after more than a century of disputes.[10]

Augustine wrote of prevenient grace, and expanded to a discussion of predestination. A number of monastic communities took exception to the latter because it seemed to nullify the value of asceticism practiced under their rules. John Cassian felt that Augustine's stress on predestination ruled out any need for human cooperation or consent.

Vincent was suspected of Semipelagianism but whether he actually held that doctrine is not clear as it is not found in the Commonitorium. But it is probable that his sympathies were with those who held it. Considering that the monks of the Lérins Islands – like the general body of clergy of Southern Gaul – were Semipelagians, it is not surprising that Vincent was suspected of Semipelagianism. It is also possible that Vincent held to a position closer to the Eastern Orthodox position of today, which they claim to have been virtually universal until the time of Augustine, and which may have been interpreted as Semipelagian by Augustine's followers.

Vincent upheld tradition and seemed to have objected to much of Augustine's work as "new" theology. He shared Cassian's reservations about Augustine's views on the role of grace. In the Commonitorium he listed theologians and teachers who, in his view, had made significant contributions to the defense and spreading of the Gospel; he omitted Augustine from that list. Some commentators have viewed Cassian and Vincent as "Semiaugustinian" rather than Semipelagian.

It is a matter of academic debate whether Vincent is the author of the Objectiones Vincentianae, a collection of sixteen inferences allegedly deduced from Augustine's writings, which is lost and only known through Prosper of Aquitaine's rejoinder, Responsiones ad capitula objectionum Vincentianarum. It is dated close to the time of the Commonitorium and its animus is very similar to the Commonitorium sections 70 and 86, making it possible that both were written by the same author.[5]

Source Wikipedia

Saint Vincent died peacefully in 456 AD. His relics are preserved at Lérins.

Acts 16:16-34 NKJV

Paul and Silas Imprisoned

16 Now it happened, as we went to prayer, that a certain slave girl possessed with a spirit of divination met us, who brought her masters much profit by fortune-telling. 17 This girl followed Paul and us, and cried out, saying, “These men are the servants of the Most High God, who proclaim to us the way of salvation.” 18 And this she did for many days.

But Paul, greatly [a]annoyed, turned and said to the spirit, “I command you in the name of Jesus Christ to come out of her.” And he came out that very hour. 19 But when her masters saw that their hope of profit was gone, they seized Paul and Silas and dragged them into the marketplace to the authorities.

20 And they brought them to the magistrates, and said, “These men, being Jews, exceedingly trouble our city; 21 and they teach customs which are not lawful for us, being Romans, to receive or observe.” 22 Then the multitude rose up together against them; and the magistrates tore off their clothes and commanded them to be beaten with rods. 23 And when they had laid many stripes on them, they threw them into prison, commanding the jailer to keep them securely. 24 Having received such a charge, he put them into the inner prison and fastened their feet in the stocks.

The Philippian Jailer Saved

25 But at midnight Paul and Silas were praying and singing hymns to God, and the prisoners were listening to them. 26 Suddenly there was a great earthquake, so that the foundations of the prison were shaken; and immediately all the doors were opened and everyone’s chains were loosed. 27 And the keeper of the prison, awaking from sleep and seeing the prison doors open, supposing the prisoners had fled, drew his sword and was about to kill himself. 28 But Paul called with a loud voice, saying, “Do yourself no harm, for we are all here.”

29 Then he called for a light, ran in, and fell down trembling before Paul and Silas. 30 And he brought them out and said, “Sirs, what must I do to be saved?”

31 So they said, “Believe on the Lord Jesus Christ, and you will be saved, you and your household.” 32 Then they spoke the word of the Lord to him and to all who were in his house. 33 And he took them the same hour of the night and washed their stripes. And immediately he and all his family were baptized. 34 Now when he had brought them into his house, he set food before them; and he rejoiced, having believed in God with all his household.

Footnotes:

Acts 16:18 distressed

John 9:1-38 NKJV

A Man Born Blind Receives Sight

9 Now as Jesus passed by, He saw a man who was blind from birth. 2 And His disciples asked Him, saying, “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?”

3 Jesus answered, “Neither this man nor his parents sinned, but that the works of God should be revealed in him. 4 I[a] must work the works of Him who sent Me while it is day; the night is coming when no one can work. 5 As long as I am in the world, I am the light of the world.”

6 When He had said these things, He spat on the ground and made clay with the saliva; and He anointed the eyes of the blind man with the clay. 7 And He said to him, “Go, wash in the pool of Siloam” (which is translated, Sent). So he went and washed, and came back seeing.

8 Therefore the neighbors and those who previously had seen that he was [b]blind said, “Is not this he who sat and begged?”

9 Some said, “This is he.” Others said, [c]“He is like him.”

He said, “I am he.”

10 Therefore they said to him, “How were your eyes opened?”

11 He answered and said, “A Man called Jesus made clay and anointed my eyes and said to me, ‘Go to [d]the pool of Siloam and wash.’ So I went and washed, and I received sight.”

12 Then they said to him, “Where is He?”

He said, “I do not know.”

The Pharisees Excommunicate the Healed Man

13 They brought him who formerly was blind to the Pharisees. 14 Now it was a Sabbath when Jesus made the clay and opened his eyes. 15 Then the Pharisees also asked him again how he had received his sight. He said to them, “He put clay on my eyes, and I washed, and I see.”

16 Therefore some of the Pharisees said, “This Man is not from God, because He does not [e]keep the Sabbath.”

Others said, “How can a man who is a sinner do such signs?” And there was a division among them.

17 They said to the blind man again, “What do you say about Him because He opened your eyes?”

He said, “He is a prophet.”

18 But the Jews did not believe concerning him, that he had been blind and received his sight, until they called the parents of him who had received his sight. 19 And they asked them, saying, “Is this your son, who you say was born blind? How then does he now see?”

20 His parents answered them and said, “We know that this is our son, and that he was born blind; 21 but by what means he now sees we do not know, or who opened his eyes we do not know. He is of age; ask him. He will speak for himself.” 22 His parents said these thingsbecause they feared the Jews, for the Jews had agreed already that if anyone confessed that He was Christ, he would be put out of the synagogue. 23 Therefore his parents said, “He is of age; ask him.”

24 So they again called the man who was blind, and said to him, “Give God the glory! We know that this Man is a sinner.”

25 He answered and said, “Whether He is a sinner or not I do not know. One thing I know: that though I was blind, now I see.”

26 Then they said to him again, “What did He do to you? How did He open your eyes?”

27 He answered them, “I told you already, and you did not listen. Why do you want to hear itagain? Do you also want to become His disciples?”

28 Then they reviled him and said, “You are His disciple, but we are Moses’ disciples. 29 We know that God spoke to Moses; as for this fellow, we do not know where He is from.”

30 The man answered and said to them, “Why, this is a marvelous thing, that you do not know where He is from; yet He has opened my eyes! 31 Now we know that God does not hear sinners; but if anyone is a worshiper of God and does His will, He hears him. 32 Since the world began it has been unheard of that anyone opened the eyes of one who was born blind. 33 If this Man were not from God, He could do nothing.”

34 They answered and said to him, “You were completely born in sins, and are you teaching us?” And they [f]cast him out.

True Vision and True Blindness

35 Jesus heard that they had cast him out; and when He had found him, He said to him, “Do you believe in the Son of [g]God?”

36 He answered and said, “Who is He, Lord, that I may believe in Him?”

37 And Jesus said to him, “You have both seen Him and it is He who is talking with you.”

38 Then he said, “Lord, I believe!” And he worshiped Him.

Footnotes:

John 9:4 NU We

John 9:8 NU a beggar

John 9:9 NU “No, but he is like him.”

John 9:11 NU omits the pool of

John 9:16 observe

John 9:34 Excommunicated him

John 9:35 NU Man

New King James Version (NKJV) Scripture taken from the New King James Version®. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson. All rights reserved.

Source Biblegateway

0 notes

Photo

"The Bible teaches us how to go to Heaven, not how the heavens go." -Cardinal Caesar Baronius [1872×1102 pixels]

0 notes

Photo

"The Bible teaches us how to go to Heaven, not how the heavens go." -Cardinal Caesar Baronius [1872×1102 pixels]

0 notes

Text

Padre Rossa urged Philip to become a priest. Despite his reluctance, he obeyed his confessor’s advice and was ordained in 1551. His first years as a priest were largely devoted to hearing confessions, assisting at hospitals, and ministering to the dying. He lived at the hospital of San Girolamo della Carità. Meanwhile, seeing that disciples continued to gather around him, requests for help started to arrive. The leadership of the new Florentine church of Rome, San Giovanni dei Fiorentini, asked if his priests would take over their parish. Luckily, Philip was able to assign five priests to the parish, including Caesar Baronius, the future historian and cardinal. Philip’s priests worked as missionaries of Rome, preaching sermons in different churches every evening. This was a very novel idea at the time.

In 1556, the group read the letters of Saint Francis Xavier at their meetings. These letters filled many of them with overflowing zeal; they desired to give up everything and go to India as missionaries, including Philip. However, he went first to consult a holy Cistercian, Fra Agostino Ghettini, who listened to his story and told him to come back in a week. One week later, having prayed about it, Fra Agostino told him, “Rome will be your India.” As such, St. Philip redoubled his efforts to evangelize Rome. His ability to attract many vocations was due to his openhearted confidence: "Cast yourself into the arms of God” he told interested aspirants, “And be very sure that if He wants anything of you, He will fit you for the work and give you strength."

4 notes

·

View notes