#CVM/Alpaca

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I finished the singles on my work spin, so brought them home to make plying balls (not pictured is the 8th one, that accidently got left at work) and then ply. This was a CVM/alpaca blend roving that I bought from Cabled Fiber and Yarn in Port Angeles, WA while I was on an awesome road trip through the Pacific Northwest.

I took the chance to swap out my work spindle and travel spindle, so the work spin will be on my purple nebula spindle. The fiber is 100 grams of CVM/alpaca roving I bought from Natural Twist at PlyAway. Purple and green, I am predictable.

I've got another 100 grams in the stash of this colorway, and 100 grams of a grey green wool/alpaca from Natural twist that I spun up on my spindle a while ago (also, mostly on work calls), so time to start thinking of a pattern that would use all three yarns.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ahem. Fiber festival haul...

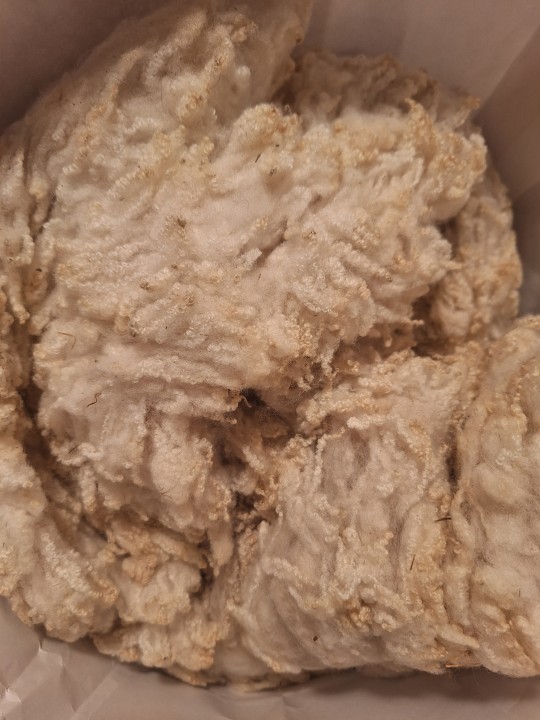

Firstly, this incredible shetland fleece @rival-the-rose traded me for some hampshire and that distaff I made (which just doesn't work for my messed up hands, hopefully it will work for them !). The crimp is so unbelievably fine, I can't wait to work with it ! 1 pound, 8 ounces (675 ish grams)

Secondly this incredible jacob lambswool. Admittedly I'm just obsessed with Jacob, especially lambswool. But this is so soft and fine and has almost no vm (having been coated ! Never spun a coated fleece before !) And has sooooo much lanolin. Smells beautiful tbh. Gonna make a great shawl or scarf I think ! 1 pound, 4 ounces (560 ish grams)

This is greener than it looks in the picture. Super pretty and soft--the seller said it was a merino cross. This will be for moss yarn projects :3 6.5 ounces (190 grams)

Tons of dyed mohair locks. Everyone was selling them and for very cheap ! Mostly greens (for the moss yarn as well) but a few other colors for blending with. 5.5 ounces (150 ish grams)

Random grab bag--the bigger brown lot is suri alpaca--I think the rest is cashmere or pygora, slightly felted. 2 ounces (50 grams)

Felted Buffalo down. Was incredibly cheap bc it was felted. I think I can get some good fiber out of it though--it's not too bad. And some random wool on the left that was also in the bag. The Buffalo is 2 ounces (50 grams).

This incredible cvm batt from a sheep named Cissie. This was her wool when she was younger, the shepherd and I were talking and she showed me her more recent fleece, which was oatmeal colored. Apparently she is the model sheep, and the shepherd loves her a lot. Honestly, will add to the spinning experience. So so soft ! 3 ounces (90 ish grams)

From the same shepherd, this southdown romney blend batt. So nice and sturdy. 3 ounces (90 ish grams).

That's all I can fit on this post, the rest will be on the reblog !

#to be clear i dont buy a lot of fiber outside of festivals#only stuff i need for specific projects. most of the time anyway#so i tend to save up for the fiber fest and buy most of my stuff there#wool#flock and fiber festival

70 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Round two of #tourdefleece2020 done. I didn’t get to my last batch of rolags so I missed my goal, but I got some spinning done. From bottom left: two mini skeins of Dorset, four of BFL (my new fave roving), four of Alpaca/CVM, four of CVM. #handspinning #dropspindle https://www.instagram.com/p/CFYJ-NFFArO/?igshid=186clgl95i3an

1 note

·

View note

Text

L is for Llama

L is for Llama

#DoodlewashJanuary2022 Prompt: Llama. Did you know that llamas have a metabolism that is similar to that of a human diabetic? The OSU College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM) has a herd of llamas and alpacas they they study hoping to provide insight into human diabetes treatment. Hahnemühle Nostalgie SketchbookKuretake Real Clean Color Brush PenKuretake Cambio Tambien Brush PenKuretake Mangaka…

View On WordPress

#DoodlewashJanuary2022#WorldWatercolorGroup#@Hahnemühle_USA#@kuretakejapan#Alphabet#Doodlewash prompts#kuretake#Life Imitates Doodles#Llama#Primer#Sandra Strait

0 notes

Text

Raising Sheep For Profit: How to Sell Raw Fleece

By Bonnie Sutten – When I first started raising sheep for profit, raw fleece sales were on the bottom of my priority list. I thought that if I was raising sheep for wool, it was the processed roving or other products that would be the way to go. I spent a lot of time and money, believing that raw wool would not be profitable.

When we purchased the CVM/Romeldale sheep over other sheep breeds, we were very excited about their ability to produce a unique and beautiful wool, and we were soon flooded with requests to buy raw fleece. Today, the sale of our raw fleece now stands at about 40% to 50% of my total wool sales. From the beginning of our work in raising sheep for profit, our farm set a goal to continue to raise this breed with the handspinner in mind. This starts with not putting any wool into spinner’s hands that does not first meet strict preparation guidelines.

Because of this, we never sell any fleeces on shearing day. There is never time that day to thoroughly skirt a fleece, and if you sell it to someone and they take it home and show someone else, that unskirted fleece is going to represent your farm to the public. Sure, they can reserve it, but it won’t leave our farm until it is skirted and has our stamp of approval. It just isn’t worth it, plus, you would have to lower the price considerably if you were going to sell an unskirted fleece by the pound.

Ready to Start Your Own Backyard Flock?

Get tips and tricks for starting your new flock from our chicken experts. Download your FREE guide today! YES! I want this Free Guide »

I am a handspinner, and have purchased my fair share of raw wool. As a wool customer, as well as a wool producer, I have learned there are definitely various degrees of wool available for purchase. It is disappointing to send money for a product, along with shipping charges, and open the box and find a fleece that is less than a quality product. In some purchased fleeces I have found burrs and sticks, large hay and straw pieces, numerous second cuts, and even manure tags (feces) from the animal. In one particularly bad incident, I opened a box of wool and it was all felted together!

In raising sheep for profit, we choose a breed of sheep renowned for its superior wool production so it has been important for us to treat the sales of this wool with utmost care. When someone buys raw fleece from our farm, they are only getting the best part of that fleece. For our prices, which range from $18.00-$25.00 per pound, we only put on the scale and into the box prime wool that has been hand skirted (wool that has been covered while on the animal, and skirted with a “fine tooth comb”).

At the same time, with all the time and effort that I have put into raising sheep for profit, the cost of my fleece reflects my 365-day investment. I want buyers to see the quality that particular animal has the ability to produce. I also understand that my customer is going to form an opinion – in many cases, of the entire breed – by my fleeces. It is not fair, but it is true. I do this myself if I buy a bad fleece from a particular breed, and I have to force my self to try again from a different breeder of that same breed.

Preparing a Fleece

Cover your investment. By this I mean, literally, cover your sheep with a sheep coat for the cleanest possible fleeces. There are some breeds out there that do not do well covered (like the Icelandic), but the majority do very well. Matilda coats, which we use on our sheep, are lightweight, breathable fabric that reflects the sun and UV rays to prevent sun damage, and keep the sheep cooler in the summer and warmer in the winter. By using these coats, there are no sun-bleached tips that can break off, and the wool does not rot from having snow and ice on the sheep. We have only needed to remove these when our Michigan summer has been in the 100s and extremely high humidity. Romeldales do very well in our climate, and they do very well with the coats on to protect their wool.

Remember: Even though I am focusing on CVM/Romeldale sheep, most other sheep breeds can be covered with sheep coats, as well as Angora goats and alpacas. If you do not cover your sheep, you must feed and house your animals in the most efficient way to keep fleeces from being destroyed by the elements and contamination.

The beginning of the cycle is the day your sheep are shorn; the work begins all over again.

A sheep, by nature, is designed to produce wool. You need to offer optimum nutrition when considering what to feed sheep, and plenty of fresh water year round. I had heated water in all my pens this year and the fleeces have never looked nicer. I know there are many people who say they do fine on snow, but when you feed animals dry hay, they need water to properly aid digestion and kidney function. They also require adequate shelter and living conditions.

A deworming and vaccination program is necessary, as well as keeping all diseases out of your flock such as sore mouth and foot rot. A sheep can’t produce quality fiber if its immune system is constantly taxed by disease, not to mention that it is immoral and unethical to sell any product from a contagious animal.

The Harvest

The optimum time for a ewe to be shorn is shortly before or after lambing: The event can cause a break in the wool which can compromise the integrity of the wool fibers. About a year later, (sometimes more or less, depending on the growth rate of your breed’s wool) you can finally reap the rewards of all your hard work.

Take a look at your fleeces, feel them, lay them out and really inspect them. Now pat yourself on the back for all your hard work and dedication to produce the best fleece your animal can grow.

You should have before you a lustrous, clean, healthy-looking fleece. The fiber locks should ping with strength when you tug on them from either end, not make a tearing sound or break in half. They should smell like a sheep, not like manure or urine. If they have been getting fresh air and have clean living quarters, you should smell the proof in the fleece. If your fleece is not up to these standards, that fleece needs to go in the junk box used for felting or quilt batts, mulch, or insulation, but should not be sold to handspinners.

When the fleece is shorn off of the animal you should remove any of the manure tags or soiled fleece. Store the fleece in a container that allows air to circulate through it. My preference is cardboard boxes with loose fitting tops. These can be labeled with a permanent marker and stacked in an area that is free from moisture and pests.

Skirting a Fleece

Just because our fleeces are covered, it doesn’t mean all the work is eliminated. When you skirt a fleece, get comfortable; you are going to be there for a while. Find an area with good lighting, either outside or inside. Personally, in the cold spring months, I skirt my fleeces inside. I lay a bed sheet out on the living room floor and put in a good movie. Many people would prefer to do this chore outside, especially if you have a special area just for this task. You can build a really nice skirting table with a mesh screen top so the small pieces of vegetation fall out easily onto the ground. Even though my sheep are covered, my fleeces take me a minimum of 45 minutes to an hour to completely skirt and prepare.

Since I skirt most of my fleeces a few days after shearing, they are free of mildew, stains and other problems associated with storing fleeces for a long period of time. I recommend that if you can’t get to your fleeces right away to process or spin, at least lay them out flat to let them air dry in a protected area to remove any moisture from them.

First, lay them cut side down and remove all the big pieces of vegetable matter (VM)-hay, grass, straw, sticks, etc. After you get that done, make sure you tear off all the belly wool and heavily contaminated neck wool and discard. Many times the shearer will throw that off to the side so it never gets mixed in, but in case he didn’t, double check. Also, remove any britch wool, if your fleece has it. It is best described as “hair” that is coarse, straight wool on the lower parts of the sheep and on the back leg. Britch wool is not desired by handspinners and should be put in the junk box, which as I mentioned, is for non-spinning projects.

Next, flip the wool over and remove any second cuts the shearer left. There should be a minimum of these if you have a good shearer. Second cuts are created when the blades are passed over the same area twice and have left stubble (short pieces) in the wool. These produce bothersome neps (lint-like blobs) in the yarn and finished products and are very irritating to handspinners.

Finally, to get to the prime wool, select out the areas that the coat has covered, and set them aside. This is “prime wool” and can now be sorted out to sell to handspinners. The remaining wool that was not covered by the coat will vary from sheep to sheep as to what its destination will be. Our non-covered wool is usually graded into two types, “roving quality” and “batt quality.”

The roving quality will have a low amount of VM that is not embedded in deeply into the fibers and has a minimum length of three inches. If it has any dirt on the tips it will still be suitable for roving; the heat and detergent will remove that. (Editor’s note: “roving” is wool whose fibers have been straightened and made parallel to each other by the process of carding, forming a sort of loose “rope” of wool up to about an inch in diameter.) If it is shorter than three inches I put it into a different group, to have wool batts made out of it for craft projects and quilting.

Packaging Your Wool

Your product must be appealing! I can’t stress this enough, especially if you’re raising sheep for profit from the sales of wool and fleece. Imagine yourself as the recipient of your wool and picture opening it for the first time. Do you want to say “Wow!” or do you want to hurry and close it back up, throw it in the closet, and hide it from your spouse so you’re not embarrassed you spent good money on your wool? Personally, I have had both reactions with wool that I have bought from someone else. Needless to say, I never buy again from the people who sold me the latter type.

First, find a nice, medium-weight box. I like to use ones that are just plain, cardboard boxes. I find it in poor taste to receive wool in a toaster box or crock pot box, but maybe that is just me. Also, these types of printed boxes are generally heavier, and I don’t feel it is fair to have to pay shipping for heavy packaging. I think it better to search a little and use a plain box with minimal print on it.

Now, you are ready to fill it. Take a container and weigh it empty so you can subtract the weight from the wool. As you start selecting wool from your pile, look it over well, in case you have missed VM, second cuts or second quality wool the first time around.

If the fleece is variegated, spotted or patterned, make sure you have indicated that in your description of the fleece. Now you are going to have to try and have a complimentary color scheme if they have ordered less than the full fleece. Try to keep the colors similar so that if it is used for a project they won’t get really dramatic color variations unless they have requested that.

After you have weighed out the proper amount, place it in the box. Make sure the box is big enough to accommodate the wool without damaging it, but don’t over-package it with too large a box, either. I like to line my boxes with tissue paper. It keeps the wool from poking out as you are trying to tape it up and it also looks neater and compliments the contents. If there is fiber from more than one animal, separate it with tissue paper and make sure you label which animal is which with a small piece of paper or a label on the tissue.

You can pack wool pretty tightly, pushing it gently down to get the air out of it. When the box is opened, it will fluff up again. I tape the invoice right on the top of the tissue so they can find it easily when they open the package. Include an address inside, just in case your package is damaged or the label is lost.

Finally, label the package clearly with a neatly addressed label. I make a point to ask customers how they want their package shipped, because some carriers work better to different parts of the country. Then you can get the approximate shipping cost from the internet or phone so you can let the buyer know.

Money Matters When Raising Sheep for Profit

I know too many small producers who are too trusting and ship the item and never see the money. Always collect the money before shipping the wool! Many fiber producers are honest people and they assume the rest of the world is as honest as they are. Unfortunately, this is not always true. Let your customer know the total including shipping costs and then wait for them to send payment before shipping their order.

Some small businesses have invested in a credit card machine and can process orders more quickly when they can take a credit card. We have not yet made this investment, but if our farm business continues to grow, we may consider it for the future.

Getting Still More Business

You may want to include extras in your package. A photo and information about the animal that produced the fiber they bought, a fiber sample card, roving sample, soap sample, brochure or other small item would be great. You have a captive audience with this customer, and you have the perfect opportunity to present your other products from your farm.

Repeat customers are so important in this business. Remember, you have produced the best, most cared-for fleece; now you need to present it in its best light.

A nice gesture is to include a stamped return postcard for their comments and questions. You can also use that opportunity to have them complete a survey about what their preferences are in buying a fleece. You can target your market and next year know more information about your customers. You might even want to send them a few extra business cards so they can share your name with friends.

Remember to rate your final package on the “Wow!” scale. If you don’t think it is a wholehearted “Wow!” then you have more work to do.

Although I am so partial to my CVM/Romeldale sheep, I do love to spin many other breeds of sheep. I firmly believe if you have selected a breed you truly love when you’re raising sheep for profit, you can achieve good if not excellent prices for your wool if you follow careful business practices.

There is no shortage of wool in this country, but there is a shortage of outstanding wool for handspinners. Cover your fleeces, keep your sheep in tip-top condition, prepare and package your fibers with the utmost attention to detail, and you will find your wool sales booming.

Originally published in sheep! July/August 2003 and regularly vetted for accuracy.

Raising Sheep For Profit: How to Sell Raw Fleece was originally posted by All About Chickens

0 notes

Photo

Longest Thread contest is about a year away (maybe 13 months) but mailing deadline for entries is end of October. Every year they have it (odd years) I say I’m going to do it, but never have. And it takes a LONG time to spin up the minimum 10 grams of wool (and now they allow alpaca as well) THAT thin. Here’s the beginning of my first practice. Wool is CVM from #longridgefarm, ultralight spindle from #bullsheepfibery. Gold thread is sewing thread, for comparison. #spinnersofinstagram #dropspindle #ultralightspindle #froghair

0 notes

Photo

My goal this weekend is to ply. I need to clean off some bobbins before PlyAway. While I have two weeks before the classes I’m taking, I’ll be away from my wheel for most of a week on a work trip.

Coincidentally, I’ve also finished up the singles on my work spindle (green balls, wool/alpaca) and my WFH spindle (yellow and red balls, California wool). I like to make my singles into plying balls when spindling, to making plying more portable.

My plan is to take my assortment of corriedale (the eight colors of the tutti fruti collection) to spin at work, and use the CVM/alpaca blend I bought in Washington on my WFH spindle. I hope for many online meetings to fidget spin through.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I’m impressed how much darker this blend got when spun. Fiber is a merino/silk/bamboo/seacell blend called Abyssal from Lost Gnome fiber that I bought a number of years ago. I’m in a mood because I spun all four ounces in a day, and started on 4 ounces of the same blend in the colorway called Neritic. In a common complaint, I could be working on any of the projects I have planned but I just wanted a mindless small project.

I bought more fiber than I need at PlyAway, so spinning is on my mind. I also spindled some corriedale during work calls because I bought some more alpaca/CVM sliver that I want to get to. Eyes bigger than my spinning time.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Raising Sheep For Profit: How to Sell Raw Fleece

By Bonnie Sutten – When I first started raising sheep for profit, raw fleece sales were on the bottom of my priority list. I thought that if I was raising sheep for wool, it was the processed roving or other products that would be the way to go. I spent a lot of time and money, believing that raw wool would not be profitable.

When we purchased the CVM/Romeldale sheep over other sheep breeds, we were very excited about their ability to produce a unique and beautiful wool, and we were soon flooded with requests to buy raw fleece. Today, the sale of our raw fleece now stands at about 40% to 50% of my total wool sales. From the beginning of our work in raising sheep for profit, our farm set a goal to continue to raise this breed with the handspinner in mind. This starts with not putting any wool into spinner’s hands that does not first meet strict preparation guidelines.

Because of this, we never sell any fleeces on shearing day. There is never time that day to thoroughly skirt a fleece, and if you sell it to someone and they take it home and show someone else, that unskirted fleece is going to represent your farm to the public. Sure, they can reserve it, but it won’t leave our farm until it is skirted and has our stamp of approval. It just isn’t worth it, plus, you would have to lower the price considerably if you were going to sell an unskirted fleece by the pound.

Our best sheep advice revealed...

Even old pros say they got dozens of tips for their flocks by reading this guide. YES! I want this Free Report »

I am a handspinner, and have purchased my fair share of raw wool. As a wool customer, as well as a wool producer, I have learned there are definitely various degrees of wool available for purchase. It is disappointing to send money for a product, along with shipping charges, and open the box and find a fleece that is less than a quality product. In some purchased fleeces I have found burrs and sticks, large hay and straw pieces, numerous second cuts, and even manure tags (feces) from the animal. In one particularly bad incident, I opened a box of wool and it was all felted together!

In raising sheep for profit, we choose a breed of sheep renowned for its superior wool production so it has been important for us to treat the sales of this wool with utmost care. When someone buys raw fleece from our farm, they are only getting the best part of that fleece. For our prices, which range from $18.00-$25.00 per pound, we only put on the scale and into the box prime wool that has been hand skirted (wool that has been covered while on the animal, and skirted with a “fine tooth comb”).

At the same time, with all the time and effort that I have put into raising sheep for profit, the cost of my fleece reflects my 365-day investment. I want buyers to see the quality that particular animal has the ability to produce. I also understand that my customer is going to form an opinion – in many cases, of the entire breed – by my fleeces. It is not fair, but it is true. I do this myself if I buy a bad fleece from a particular breed, and I have to force my self to try again from a different breeder of that same breed.

Preparing a Fleece

Cover your investment. By this I mean, literally, cover your sheep with a sheep coat for the cleanest possible fleeces. There are some breeds out there that do not do well covered (like the Icelandic), but the majority do very well. Matilda coats, which we use on our sheep, are lightweight, breathable fabric that reflects the sun and UV rays to prevent sun damage, and keep the sheep cooler in the summer and warmer in the winter. By using these coats, there are no sun-bleached tips that can break off, and the wool does not rot from having snow and ice on the sheep. We have only needed to remove these when our Michigan summer has been in the 100s and extremely high humidity. Romeldales do very well in our climate, and they do very well with the coats on to protect their wool.

Remember: Even though I am focusing on CVM/Romeldale sheep, most other sheep breeds can be covered with sheep coats, as well as Angora goats and alpacas. If you do not cover your sheep, you must feed and house your animals in the most efficient way to keep fleeces from being destroyed by the elements and contamination.

The beginning of the cycle is the day your sheep are shorn; the work begins all over again.

A sheep, by nature, is designed to produce wool. You need to offer optimum nutrition when considering what to feed sheep, and plenty of fresh water year round. I had heated water in all my pens this year and the fleeces have never looked nicer. I know there are many people who say they do fine on snow, but when you feed animals dry hay, they need water to properly aid digestion and kidney function. They also require adequate shelter and living conditions.

A deworming and vaccination program is necessary, as well as keeping all diseases out of your flock such as sore mouth and foot rot. A sheep can’t produce quality fiber if its immune system is constantly taxed by disease, not to mention that it is immoral and unethical to sell any product from a contagious animal.

The Harvest

The optimum time for a ewe to be shorn is shortly before or after lambing: The event can cause a break in the wool which can compromise the integrity of the wool fibers. About a year later, (sometimes more or less, depending on the growth rate of your breed’s wool) you can finally reap the rewards of all your hard work.

Take a look at your fleeces, feel them, lay them out and really inspect them. Now pat yourself on the back for all your hard work and dedication to produce the best fleece your animal can grow.

You should have before you a lustrous, clean, healthy-looking fleece. The fiber locks should ping with strength when you tug on them from either end, not make a tearing sound or break in half. They should smell like a sheep, not like manure or urine. If they have been getting fresh air and have clean living quarters, you should smell the proof in the fleece. If your fleece is not up to these standards, that fleece needs to go in the junk box used for felting or quilt batts, mulch, or insulation, but should not be sold to handspinners.

When the fleece is shorn off of the animal you should remove any of the manure tags or soiled fleece. Store the fleece in a container that allows air to circulate through it. My preference is cardboard boxes with loose fitting tops. These can be labeled with a permanent marker and stacked in an area that is free from moisture and pests.

Skirting a Fleece

Just because our fleeces are covered, it doesn’t mean all the work is eliminated. When you skirt a fleece, get comfortable; you are going to be there for a while. Find an area with good lighting, either outside or inside. Personally, in the cold spring months, I skirt my fleeces inside. I lay a bed sheet out on the living room floor and put in a good movie. Many people would prefer to do this chore outside, especially if you have a special area just for this task. You can build a really nice skirting table with a mesh screen top so the small pieces of vegetation fall out easily onto the ground. Even though my sheep are covered, my fleeces take me a minimum of 45 minutes to an hour to completely skirt and prepare.

Since I skirt most of my fleeces a few days after shearing, they are free of mildew, stains and other problems associated with storing fleeces for a long period of time. I recommend that if you can’t get to your fleeces right away to process or spin, at least lay them out flat to let them air dry in a protected area to remove any moisture from them.

First, lay them cut side down and remove all the big pieces of vegetable matter (VM)-hay, grass, straw, sticks, etc. After you get that done, make sure you tear off all the belly wool and heavily contaminated neck wool and discard. Many times the shearer will throw that off to the side so it never gets mixed in, but in case he didn’t, double check. Also, remove any britch wool, if your fleece has it. It is best described as “hair” that is coarse, straight wool on the lower parts of the sheep and on the back leg. Britch wool is not desired by handspinners and should be put in the junk box, which as I mentioned, is for non-spinning projects.

Next, flip the wool over and remove any second cuts the shearer left. There should be a minimum of these if you have a good shearer. Second cuts are created when the blades are passed over the same area twice and have left stubble (short pieces) in the wool. These produce bothersome neps (lint-like blobs) in the yarn and finished products and are very irritating to handspinners.

Finally, to get to the prime wool, select out the areas that the coat has covered, and set them aside. This is “prime wool” and can now be sorted out to sell to handspinners. The remaining wool that was not covered by the coat will vary from sheep to sheep as to what its destination will be. Our non-covered wool is usually graded into two types, “roving quality” and “batt quality.”

The roving quality will have a low amount of VM that is not embedded in deeply into the fibers and has a minimum length of three inches. If it has any dirt on the tips it will still be suitable for roving; the heat and detergent will remove that. (Editor’s note: “roving” is wool whose fibers have been straightened and made parallel to each other by the process of carding, forming a sort of loose “rope” of wool up to about an inch in diameter.) If it is shorter than three inches I put it into a different group, to have wool batts made out of it for craft projects and quilting.

Packaging Your Wool

Your product must be appealing! I can’t stress this enough, especially if you’re raising sheep for profit from the sales of wool and fleece. Imagine yourself as the recipient of your wool and picture opening it for the first time. Do you want to say “Wow!” or do you want to hurry and close it back up, throw it in the closet, and hide it from your spouse so you’re not embarrassed you spent good money on your wool? Personally, I have had both reactions with wool that I have bought from someone else. Needless to say, I never buy again from the people who sold me the latter type.

First, find a nice, medium-weight box. I like to use ones that are just plain, cardboard boxes. I find it in poor taste to receive wool in a toaster box or crock pot box, but maybe that is just me. Also, these types of printed boxes are generally heavier, and I don’t feel it is fair to have to pay shipping for heavy packaging. I think it better to search a little and use a plain box with minimal print on it.

Now, you are ready to fill it. Take a container and weigh it empty so you can subtract the weight from the wool. As you start selecting wool from your pile, look it over well, in case you have missed VM, second cuts or second quality wool the first time around.

If the fleece is variegated, spotted or patterned, make sure you have indicated that in your description of the fleece. Now you are going to have to try and have a complimentary color scheme if they have ordered less than the full fleece. Try to keep the colors similar so that if it is used for a project they won’t get really dramatic color variations unless they have requested that.

After you have weighed out the proper amount, place it in the box. Make sure the box is big enough to accommodate the wool without damaging it, but don’t over-package it with too large a box, either. I like to line my boxes with tissue paper. It keeps the wool from poking out as you are trying to tape it up and it also looks neater and compliments the contents. If there is fiber from more than one animal, separate it with tissue paper and make sure you label which animal is which with a small piece of paper or a label on the tissue.

You can pack wool pretty tightly, pushing it gently down to get the air out of it. When the box is opened, it will fluff up again. I tape the invoice right on the top of the tissue so they can find it easily when they open the package. Include an address inside, just in case your package is damaged or the label is lost.

Finally, label the package clearly with a neatly addressed label. I make a point to ask customers how they want their package shipped, because some carriers work better to different parts of the country. Then you can get the approximate shipping cost from the internet or phone so you can let the buyer know.

Money Matters When Raising Sheep for Profit

I know too many small producers who are too trusting and ship the item and never see the money. Always collect the money before shipping the wool! Many fiber producers are honest people and they assume the rest of the world is as honest as they are. Unfortunately, this is not always true. Let your customer know the total including shipping costs and then wait for them to send payment before shipping their order.

Some small businesses have invested in a credit card machine and can process orders more quickly when they can take a credit card. We have not yet made this investment, but if our farm business continues to grow, we may consider it for the future.

Getting Still More Business

You may want to include extras in your package. A photo and information about the animal that produced the fiber they bought, a fiber sample card, roving sample, soap sample, brochure or other small item would be great. You have a captive audience with this customer, and you have the perfect opportunity to present your other products from your farm.

Repeat customers are so important in this business. Remember, you have produced the best, most cared-for fleece; now you need to present it in its best light.

A nice gesture is to include a stamped return postcard for their comments and questions. You can also use that opportunity to have them complete a survey about what their preferences are in buying a fleece. You can target your market and next year know more information about your customers. You might even want to send them a few extra business cards so they can share your name with friends.

Remember to rate your final package on the “Wow!” scale. If you don’t think it is a wholehearted “Wow!” then you have more work to do.

Although I am so partial to my CVM/Romeldale sheep, I do love to spin many other breeds of sheep. I firmly believe if you have selected a breed you truly love when you’re raising sheep for profit, you can achieve good if not excellent prices for your wool if you follow careful business practices.

There is no shortage of wool in this country, but there is a shortage of outstanding wool for handspinners. Cover your fleeces, keep your sheep in tip-top condition, prepare and package your fibers with the utmost attention to detail, and you will find your wool sales booming.

Originally published in sheep! July/August 2003 and regularly vetted for accuracy.

Raising Sheep For Profit: How to Sell Raw Fleece was originally posted by All About Chickens

0 notes