#Bruckner Rossini

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Eine kleine Himmelskunde modulierter musikalischer Gesten. Der "unbekannte Bruckner" in der Digitalen Konzerthalle der Berliner Philharmoniker, beseelt von Christian Thielemann. (Wiederholung des Konzertes heute um 12 Uhr).

Wenn er denn mehr lächeln würde, vielleicht auch mal — wie es die Mallwitz nicht nur tut, nein, sie reicht’s auch weiter — … also vielleicht auch mal lachen, wenn er dirigiert, im Orchester formte er noch mehr aus, was Thielemann diesen frühen Sinfonien Bruckners im Gespräch attestiert: diesen brucknerungewöhnlichen Schwung, ja Witz der beiden frühen Sinfonien, die er und da auch…

View On WordPress

#Alban Herbst Christian Thielemann#Alban Herbst Joana Mallwitz#Alban Nikolai Herbst Anton Bruckner#Alban Nikolai Herbst Musik Kritik#Anton Bruckner Christian Thielemann#Britten Serenade Horn Tenor#Bruckner Carl Maria von Weber#Bruckner Dschungel.Anderswelt#Bruckner Rossini#Christian Thielemann Dschungel.Anderswelt#deutscher Ernst Christian Thielemann#digital concert hall berlin#Digitale Konzerthalle Berlin#Gustav Mahler Anton Bruckner#Gustav Mahler Katastrophe#Himmelskunde musikalisch Geste#lieben Gott gewidmet#Nietzsche Christentum#Nietzsche Melodie

0 notes

Text

my classical playlist consists of:

Schubert

J. S. Bach

Handel

Holst

Tchaikovsky

Johann Strauss II

Verdi

Rimsky-Korsakov

Richard Strauss

Mozart

Mussorgsky

Saint-Saëns

Dvořák

Bizet

Léo Delibes

Shostakovich

Grieg

Wagner

Vivaldi

Chopin

Liszt

Carl Orff

Debussy

Pergolesi

Pascual Narro

Zoltán Kodály

Jeremiah Clarke

Henry Purcell

Ravel

Bedřich Smetana

Hector Berlioz

Boccherini

Gabriel Fauré

Paganini

Rachmaninoff

Anton Bruckner

Mikhael Ippolitov-Ivanov

Edward Elgar

Samuel Hazo

Aram Khachaturian

Jacques Offenbach

Alexander Borodin

Rossini

Mendelssohn

Vittorio Monti

Mikis Theodorakis

Julius Fučík

John Rutter

Hermann Necke

Amilcare Ponchielli

Giuseppe Tartini

Erik Satie

or, in pie chart form

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

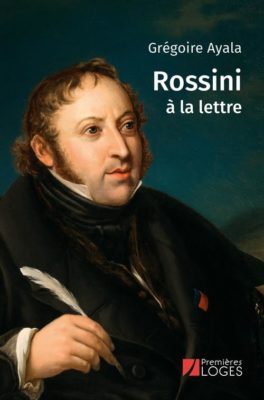

Une monographie de Rossini vient enfin combler un manque en langue française

Grégoire Ayala : Rossini à la lettre. Paris, Premières Loges. ISBN : 978-2-84385-438-5. 2023. 443 pages. 25 euros. Écrit par Jean Lacroix Dans la riche série de biographies musicales consacrées par les éditions Fayard aux grands compositeurs, on a pu constater une absence de marque, celle de Rossini (il y en a d’autres : Bruckner, par exemple, dont on va célébrer le bicentenaire de la naissance,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Lunedì 24 luglio 2023 alle ore 21.30, la Basilica di Santa Croce, ha ospitato il bellissimo concerto dei Solisti del Festival internazionale 'Italian Brass Week', Rex Richardson, Omar Tomasoni, Andrea Dell'Ira alle trombe, Oliver Darbellay, jorg Bruckner ai corni, Lito Fontana, Zoltan Kiss ai tromboni, David Childs – euphonium

Ryunosuke (Pepe) Abe – euphonium, trombone

Sérgio Carolino, Mario Barsotti, Gianluca Grosso – al tube, Filippo Lattanzi al marimba, Andrea Severi all' organo.

Musiche di J. S. Bach, G. F. Handel, G. Caccini, A. Marcello, T. Albinoni

I solisti del Festival condivideranno con il pubblico presente le più prestigiose pagine del repertorio cameristico fiorentino ed italiano, legandosi ai capolavori artistici, pittorici e scultorei, che la Basilica custodisce.

Saranno eseguiti brani della fiorentina Camerata de' Bardi, celebranti la Cappella dei Bardi di Vernio, omaggio al Conte Giovanni fondatore del circolo musicale ed intellettuale che ha dato vita al melodramma; dei compositori francescani, primo fra tutti Padre Giovan Battista Martini, maestro di Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, gli ottocenteschi Luigi Cherubini e Gioachino Rossini; così come brani sacri che si legano alle Storie di San Giovanni Battista, di San Giovanni Evangelista, di San Francesco e della Vergine Maria, celebranti i cicli pittorici realizzati da Giotto e da Gaddi per le Cappelle Peruzzi, Bardi e Baroncelli.

Riccardo Rescio per I&f Arte Cultura Attualità

Firenze 24 luglio 2023

Italian Brass Week Città di Firenze Cultura Fondazione CR Firenze Italia&friends Publiacqua SpA Basilica di Santa Croce di Firenze

Ministero della Cultura Ministero del Turismo ENIT - Agenzia Nazionale del Turismo Ivana Jelinic

0 notes

Text

WASHINGTON, DC (Catholic Online) - “I started this list as the 100 Best Pieces of Sacred Music, but I decided instead to recommend specific recordings. Why? No matter how fine the music, say Bach's Mass in B minor, a poor performance will leave the listener wondering where the "greatness" went. So the recommendations below represent a merging of both: All of the compositions are among the very best sacred music ever written, but the recorded performances succeed in communicating their extraordinary beauty.

“I also dithered over whether or not to make a list of "liturgical" music, or "mass settings," or "requiems." Each of these would make interesting lists, but I chose the broader "sacred music" with the hope that this list might be of interest to a wider spectrum of people. Composers are not limited to any denomination -- some are known to have been non-believers -- although the music belongs to the Christian tradition.

“I've also decided to limit my choices to recordings that are presently available on CDs, DVDs, Blu-rays, or digital downloads. I don't expect those who are curious about a particular title to start hunting down LPs, especially since these vinyl recordings are suddenly in great demand and prices are rising.

“This list is alphabetized, rather than listed in chronological order. This was necessary, since recordings will often include several pieces composed years apart, perhaps much more. Thus, to reiterate, there has been no attempt to arrange them in order of preference -- all 100 are among "the best" recordings of sacred music currently available. The recording label is indicated in parentheses.

What I would call 'Indispensable Sacred Music Recordings' are marked with an ***.

1.Allegri, Miserere, cond., Peter Phillips (Gimell).*** 2.Bach Mass in B Minor, cond., Nikolaus Harnoncourt (1968 recording;Teldec).*** 3.Bach, St. Matthew Passion, cond., Philippe Herreweghe (Harmonia Mundi).*** 4.Bach, Cantatas, cond., Geraint Jones and Wolfgang Gonnenwein (EMI Classics). 5.Barber, Agnus Dei, The Esoterics (Naxos). 6.Beethoven, Missa Solemnis, cond., Otto Klemperer (EMI/Angel). 7.Bernstein, Mass, cond., Leonard Bernstein (Columbia). 8.Berlioz, Requiem, cond. Colin Davis (Phillips). 9.Brahms, Requiem, cond., Otto Klemperer (EMI/Angel).*** 10.Briggs, Mass for Notre Dame, cond., Stephen Layton (Hyperion). 11.Britten, War Requiem, cond., Benjamin Britten (Decca). 12.Brubeck, To Hope! A Celebration, cond. Russell Gloyd (Telarc). 13.Bruckner, Motets, Choir of St. Mary's Cathedral (Delphian).*** 14.Byrd, Three Masses, cond., Peter Phillips (Gimell). 15.Burgon, Nunc Dimittis, cond., Richard Hickox (EMI Classics). 16.Celtic Christmas from Brittany, Ensemble Choral Du Bout Du Monde (Green Linnet) 17.Chant, Benedictine Monks of Santo Domingo de Silos (Milan/Jade). 18.Charpentier, Te Deum in D, cond., Philip Ledger (EMI Classics). 19.Christmas, The Holly and the Ivy, cond., John Rutter (Decca). 20.Christmas, Christmas with Robert Shaw, cond., Robert Shaw (Vox). 21.Christmas, Cantate Domino, cond., Torsten Nilsson (Proprius).*** 22.Christmas, Follow That Star, The Gents (Channel Classics). 23.Christmas, The Glorious Sound of Christmas, cond., Eugene Ormandy (Sony). 24.Christmas: Moravian Christmas, Czech Philharmonic Choir (ArcoDiva) 25.Desprez, Ave Maris Stella Mass, cond., Andrew Parrott (EMI Reflexe). 26.Dufay, Missa L'homme arme, cond., Paul Hillier (EMI Reflexe). 27.Duruflle, Requiem & Motets, cond. Matthew Best (Hyperion) 28.Dvorak, Requiem, cond. Istvan Kertesz (Decca). 29.Elgar, The Dream of Gerontius, cond. John Barbirolli (EMI Classics).*** 30.Elgar, The Apostles, cond. Adrian Boult (EMI Classics). 31.Elgar, The Kingdom, cond., Mark Elder (Halle). 32.Eton Choirbook, The Flower of All Virginity, cond., Harry Christophers (Coro). 33.Faure, Requiem, cond., Robert Shaw (Telarc). 34.Finnish Sacred Songs, Soile Isokoski (Ondine). 35.Finzi, In Terra Pax, cond. Vernon Handley (Lyrita). 36.Gabrieli, The Glory of Gabrieli, E. Power Biggs, organ (Sony). 37.Gesualdo, Sacred Music for Easter, cond., Bo Holten (BBC). 38.Gonoud, St. Cecilia Mass, cond. George Pretre (EMI Classics). 39.Gorecki, Beatus Vir & Totus Tuus, cond. John Nelson (Polygram). 40.Gospel Quartet, Hovie Lister and the Statesman (Chordant) 41.Guerrero, Missa Sancta et immaculata, cond., James O'Donnell (Hyperion) 42.Handel, Messiah, cond., by Nicholas McGegan (Harmonia Mundi)*** 43.Haydn, Creation, cond., Neville Marriner (Phillips). 44.Haydn, Mass in Time of War, cond., Neville Marriner (EMI Classics). 45.Hildegard of Bingen, Feather on the Breath of God, Gothic Voices (Hyperion). 46.Howells, Hymnus Paradisi, cond., David Willocks (EMI Classics).*** 47.Hymns, Amazing Grace: American Hymns and Spirituals, cond. Robert Shaw (Telarc).*** 48.Lauridsen, Lux Aeterna & O Magnum Mysterium, cond. Stephen Layton (Hyperion).*** 49.Lassus, Penitential Psalms, cond. Josef Veselka (Supraphon). 50.Leighton, Sacred Choral Music, cond., Christopher Robinson (Naxos). 51.Liszt, Christus, cond., Helmut Rilling (Hannsler). 52.Liszt, The Legend of St. Elisabeth, cond., Arpad Joo (Hungaroton). 53.Lobo, Requiem for Six Voices, cond., Peter Phillips (Gimell). 54.Martin, Requiem, cond. James O'Donnell (Hyperion). 55.Machaut, La Messe de Nostre Dame, cond., Jeremy Summerly (Naxos). 56.Mahler, 8th Symphony, cond., George Solti (Decca). 57.Mendelssohn, Elijah, cond. Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos (EMI 58.Monteverdi, 1610 Vespers, cond., Paul McCreesh (Archiv). 59.Morales, Magnificat, cond., Stephen Rice (Hyperion). 60.Mozart, Requiem, cond. Christopher Hogwood (L'Oiseau-Lyre). 61.Mozart, Mass in C Minor, cond. John Eliot Gardiner (Phillips). 62.Nystedt, Sacred Choral Music, cond., Kari Hankin (ASV). 63.Organum, Music of the Gothic Era, cond., David Munrow (Polygram). 64.Palestrina, Canticum Canticorum, Les Voix Baroques (ATMA). 65.Palestrina, Missa Papae Marcelli, cond. Peter Phillips (Gimell). 66.Part, Passio (St. John Passion), cond., Paul Hillier (ECM New Series). 67.Parsons, Ave Maria and other Sacred Music, cond., Andrew Carwood (Hyperion). 68.Pizzetti, Requiem, cond., James O'Donnell (Hyperion). 69.Poulenc, Gloria & Stabat Mater, cond., George Pretre (EMI Classics). 70.Poulenc. Mass in G Major; Motets, cond., Robert Shaw (Telarc). 71.Puccini, Messa di Gloria, cond., Antonio Pappano (EMI Classics). 72.Purcell, Complete Anthems and Services, fond., Robert King (Hyperion). 73.Rachmaninov, Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, cond., Charles Bruffy (Nimbus). 74.Rachmaninov, Vespers, cond., Robert Shaw (Telarc). 75.Respighi, Lauda Per La Nativita Del Signore, cond., Anders Eby Proprius). 76.Rheinberger, Sacred Choral Music, cond., Charles Bruffy (Chandos). 77.Rossini, Stabat Mater, cond., Antonio Pappano (EMI). 78.Rubbra, The Sacred Muse, Gloriae Dei Cantores (Gloriae Dei Cantores). 79.Rutter, Be Thou My Vision: Sacred Music, cond., John Rutter (Collegium).*** 80.Russian Divine Liturgy, Novospassky Monastery Choir (Naxos). 81.Rutti, Requiem, cond., David Hill (Naxos). 82.Saint Saens, Oratorio de Noel, cond., Anders Eby (Proprius). 83.Schubert, 3 Masses, cond., Wolfgang Sawallisch (EMI Classics). 84.Schutz, Musicalische Exequien, cond., Lionel Meunier (Ricercar). 85.Spirituals, Marian Anderson (RCA).*** 86.Spirituals, Jesse Norman (Phillips) 87.Telemann, Der Tag des Gerichts, cond., Nikolaus Harnoncourt (Teldec). 88.Thompson, Mass of the Holy Spirit, cond., James Burton (Hyperion). 89.Shapenote Carols, Tudor Choir (Loft Recordings) 90.Stravinsky, Symphony of Psalms, cond., Robert Shaw (Telarc). 91.Tallis, Spem in alium & Lamentations of Jeremiah, cond., David Hill (Hyperion).*** 92.Tschiakovsky, Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, cond, Valery Polansky (Moscow Studio). 93.Taneyev, At the Reading of a Psalm, cond., Mikhail Pletnev (Pentatone). 94.Vaughn Williams, Five Mystical Songs, cond., David Willcocks (EMI Classics).*** 95.Vaughn Williams, Mass in G, cond. David Willcocks (EMI Classics). 96.Vaughn Williams, Pilgrims Progress, cond., Adrian Boult (EMI Classics).*** 97.Verdi, Requiem, cond., Carlo Maria Guilini (EMI Classics).*** 98.Victoria, O Magnum Mysterium & Mass, cond., David Hill (Hyperion).*** 99.Victoria, Tenebrae Responsories, cond., David Hill (Hyperion). 100.Vivaldi, Sacred Music, cond., Robert King (Hyperion). “ -----

Deal W. Hudson is president of the Pennsylvania Catholics Network and former publisher/editor of Crisis Magazine. Dr. Hudson also a partner in the film/TV production company, Good Country Pictures.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

So back in the late 90s my dad--a vry srs lawyer just like me, as you’ll see--developed a special interest in what’s commonly called “Classical Music” (a genre which record stores didn’t confine to the true Classical period, and I trust you know what I mean and won’t get pedantic at me please). He proceeded to spend about two years buying CD after CD and reading book after book (keeping one book out of the library for months of renewals at a time) about famous composers, and then bringing the CDs to work and playing them in his office.

Dad had a couple of pals in the office who he infodumped on in emails about what he’d be playing and what he thought about each composer and their music. These emails developed running gags, mainly how much Dad hated Stravinsky and loved Dvorak, booze jokes about The Five, Tchaikovsky being The Five’s enemy, and practically everyone being a “poseur.”

Recently Dad found printouts of some of these emails, as well as a document titled “Top 50 Composers of All Time.” And this, I am about to share with you below the cut, because it is silly and fun.*

*Disclaimer: These are my Dad’s opinions not mine (he was actually worried I’d be offended by his rating of Vivaldi!), and I’m sharing them because they’re funny, not because I want to start a serious discussion about which composers are best. So, thank you in advance for taking this in the spirit it is offered, and not yelling at me unless you’re yelling in an equally irreverent manner.

TOP 50 COMPOSERS OF ALL TIME (by KidK’s Dad)

1. DVORAK--He never wrote anything less than brilliant. There can be no debate, he is the Greatest of All Time!!

2. Beethoven--Overall, the best symphony writer ever. The true Hammer of the Gods.

3. Mussorgsky--Pictures at an Exhibition is the single best piece of music ever written. Could outdrink any of The Five.

4. Borodin--In the Steppes of Central Asia is the second best piece of music ever written. A chemist by trade, he designed sobriety tests for The Five, which they all repeatedly failed.

5. Prokofiev. Alexander Nevsky is the best music that’s ever been in a movie. His First Symphony is, well, “Classical.”

6. Mozart--Wrote the most consistently pleasant music of all time, all of it exactly the same. Gets points for writing choral music you can actually listen to.

7. Brahms--Four great symphonies, dozens of stirring Hungarian Dances, one nasty temperament. Coolest beard of any composer.

8. Sibelius--Drunken maverick of the North Country. Laughs out loud at the mere mention of Stravinsky.

9. Saint-Saens--Danse Macabre is the best piece of devil music ever. Would be higher, but he tried to defend Stravinsky.

10. Smetana--If there was no DVORAK, he would be in the top three. The Moldau is great!

11. Bach--Ranks this high because of the sheer number of pieces he wrote, even though they were all variations of the same eight notes. Loses points for having a bunch of relatives who also thought they were composers. Result: The Bachs were the Jackson 5 of the 1600s, with C.P.E. in the role of Tito.

12. Ravel--Bolero is what every piece of music should be, repetitive but compelling. Also helped Mussorgsky out on Pictures. Liking Stravinsky was his only flaw.

13. Rimsky-Korsakov--Wrote the wonderful Scheherazade and helped Mussorgsky with Bald Mountain. Designated driver for The Five.

14. Grieg--Next to Brahms, wrote more music for cartoons than just about anyone. The Hall of the Mountain King would be great even if it wasn’t mentioned in Eric Burdon’s Spill the Wine.

15. Liszt--Superb tone poems, great Hungarian Rhapsodies, had Roger Daltrey play him in the movies.

16. Debussy--In the Top 20 even though michael Jackson told Barbara Walters he is one guy he would like to meet. La Mer is excellent!

17. Mahler--Ranks this high for two reasons: (1) the first three minutes of The Titan and (2) the fact that he wore eyeglasses that are now considered cool. Had too much singing in his symphonies to challenge the leaders.

18. Mendelssohn--A Midsummer Night’s Dream is dreamy and his Italian Symphony is spicy without leaving a bad taste in your mouth.

19. Berlioz--The idea for Symphonie Fantastique was better than the actual music, but it’s still good enough to place Hector in the Top 20.

20. Tchaikovsky--Enemy of The Five. But wrote better holiday music than Handel.

21. Haydn--More fun than Bach, but essentially copied what Bach did. His titles for his over 100 symphonies are examples of poseury at its worst.

22. Handel--Calling his pieces Water Music and Fireworks Music even made Haydn laugh. The Messiah though is very good for choral music.

23. Telemann--Another Bach disciple, but wrote great trumpet and flute music. Less of a poseur than Bach, Haydn and Handel. Would rank higher if he had written more.

24. Janacek--Worthy follower of DVORAK. Would be welcome at picnics held by The Five.

25. Rossini--Wrote terrific overture music like William Tell and the Barber of Seville. Not as big of a poseur as Verdi.

26. Copland--A favorite of Emerson Lake & Palmer, so he gets a Top 30 spot. Fanfare and Rodeo are toe-tappers and the rest of his stuff won’t sicken you.

27. Verdi--Overall, the best opera composer, but who can truthfully stand all that aimless singing?

28. Vaugh Williams--Somewhat boring, but always pleasurable. Songs like Greensleeves are the best the Island Nation of England can offer.

29. Offenbach--The Can Can was the Macarena of its day. Fun music!

30. Balakirev--President of The Five. Would be in the Top 20 but, late in life, he actually said hello to Tchaikovsky. Islamey, though, is stunning.

31. Wagner--Must have had a tremendous press agent. Most of The Ring cycle is cumbersome and impenetrable.

32. Chopin--A poseur with a piano. Did write the great Funeral March, but couldn’t orchestrate his music to save his life, or the ears of his listeners.

33. Schumann--A poseur. Ranks this high only because he ran a music newspaper that criticized other people for being poseurs.

34. Schubert--Left his Symphony unfinished, but was nevertheless a complete poseur. Actually named one of his pieces “The Trout.”

35. Richard Strauss--Without him, Elvis would have had no introductory music. Next to Wagner and Stravinsky, the most overrated composer of all time.

36. Rachmaninoff--On first listen, he’s in the Top 10. On second hearing, he starts falling like a lead zeppelin. Would be even lower, but I stopped listening.

37. Bruckner--Has almost nothing going for him, let someone else name his Symphony “The Romantic,” but is still able to laugh at Stravinsky. It’s sure a strange world.

38. Shostakovich--Ponderous posturings for little purpose. Makes no impact whatsoever on the listener. A disappointment.

39. Respighi--Did wonderful things with old music of unknown composers. Would be ranked higher if he had redone Bach.

40. Holst--Only on the list at all to appease certain readers. Called his epic work “The Planets,” yet left out Earth and stuck with Uranus. More famous for “striking a pose” than Madonna.

41. Vivaldi--Poseur in a big ugly powdered wig. Wrote The Four Seasons, then basically issued the same music over and over again, giving it different names.

42. Cui--Have never heard anything this guy did. But, he was one of The Five and that gets him into this Top 50.

43. Elgar--Even more boring than Vaughn Williams. Did write Pomp and Circumstance, but he’ll never graduate to the Top 40.

44. Hindemith--You can listen to this stuff, but like Schumann and Schubert, you instantly forget you did.

45. Bizet--Wrote Carmen, which unfortunately for him is opera. Got beat by a guy who no one has ever heard.

46. Bartok--Actually tried to be as bad as Stravinsky but, like everything else he did in life, he failed miserably.

47. Satie--Was ranked higher until it was learned that he was part of a group of poseurs called Les Six, who worshipped Tchaikovsky, sworn enemy of The Five. Did write music for Blood, Sweat and Tears.

48. Johann Strauss--The Waltz King: Wrote exclusively merry-go-round music. A joke.

49. Gershwin--The Johann Strauss of his era. Whatever this music is, it isn’t Classical.

50. Stravinsky--Listen to a jackhammer pounding away on your teeth , while the J.V. football team plays tubas, and it will still sound better than this guy. No one was worse, EVER.

#kidk says stuff#long post#classical music#for the record i'd rank vivaldi much higher and would also rank schumann higher because i enjoy his scenes from childhood for piano#also for the record dad just likes writing things like this#and none of this should really be taken seriously#i'm posting this to entertain some people pls don't make me regret it

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Saturday 12th October 7:30pm

Holy Cross Priory Church, New Walk, Leicester, LE1 6HW

Earlier this year we were approached by Holy Cross church who wondered if we could help them to put together a concert to celebrate their 200th anniversary. They particularly wanted us to perform Rossini's grand and beautiful setting of the Stabat Mater. We were eager to accept and will be joined by Dr Paul Jenkins and Knighton Chamber Orchestra along with four of the East Midlands finest soloists.

As well as celebrating the 200th anniversary of Holy Cross as a church, we will be marking their important place in the history of music making in Leicester. In the early 19th century Holy Cross provided a Catholic place of worship for refugees from Europe, including Bonapartist and musician Charles Guynemer, who reintroduced the Catholic choral tradition and with William Gardiner of the Unitarian Chapel started programmes of exciting and modern music from all over Europe. In fact the UK premiere of Rossini's Stabat Mater took place in Leicester at Holy Cross.

We have also put together a short first half of contrasting pieces to complement the Rossini work. Including pieces by Bruckner, Monteverdi, Mozart, Gardiner & Guynemer. Please join us for what should be a fantastic evening of music making!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saverne. Le Philharmonique de Strasbourg en concert

Au programme autour du thème « Vent de liberté sur les trombones » : Mozart, ouverture de La Flûte enchantée ; Beethoven 3 Equales pour 4 trombones ; Bruckner, Antiphon ; Rossini, ouverture de Guillaume Tell ; Verhelst, trombone quartet n° 1 ; Gershwin, A portrait. « Épique, noble, grandiose, capable de poésie recueillie comme d’accents orgiaques, sachant murmurer autant …

L’article Saverne. Le Philharmonique de Strasbourg en concert est apparu en premier sur HubNews.

Source : Strasbourg – HubNews https://ift.tt/3CVKYSd

0 notes

Text

May 09 in Music History

1707 Death of organist and composer Dietrich Buxtehude in Lubeck.

1740 Birth of Italian composer Giovanni Paisello in Taranto.

1745 Death of Italian composer Tomaso Antonio Vitali in Modena.

1755 FP of T. Arne's "Britannia" London.

1757 FP of Egk's "Der Revisor" Schwetzinger.

1770 Death of English composer, conductor Charles Avison.

1791 Death of American composer Francis Hopkinson.

1799 Death of French composer Claude Balbastre.

1807 FP of Isouard's "Rendez-vous de classe moyen" Paris.

1812 FP of Rossini's operaLa Scala di Seta 'Silken Ladder' in Venice.

1814 Birth of German pianist, composer Adolph Von Henselt. 1829 Birth of composer Ciro Pinsuti.

1833 Birth of composer Boleslaw Dembinski.

1846 Birth of Russian composer Nikolai Soloviev in Schwabach.

1855 Birth of German composer Julius Röntgen in Leipzig.

1857 FP of Carafa's "Sangarido" Paris.

1865 Birth of Belgian composer August de Boeck in Merchtem.

1868 FP of Anton Bruckner's First Symphony. Composer conducting in Linz. 1878 Birth of Italian impresario Fortune Gallo in Torremaggiore.

1892 Birth of composer Eric Westberg.

1896 Birth of Czech composer Jan Fiser in Hronek.

1905 Death of Austrian pianist and composer Ernst Pauer.

1914 Birth of Italian conductor Carlo Maria Giulini in Barletta, Italy.

1924 FP of Richard Strauss's ballet Schlagobers 'Whipped Cream' in Vienna.

1929 Birth of English tenor Nigel Douglas.

1930 Birth of German composer Wolfgang Bottenberg in Frankfurt.

1936 Birth of Canadian composer Bruce Mather in Toronto.

1950 Birth of French pianist Michel Beroff in Epinal, Vosges.

1950 FP of Dello Joio's "The Triumph of St. Joan" Bronxville, NY.

1951 FP, staged, of Pizzetti's "Ifigenia" Florence.

1952 Birth of Scottish mezzo-soprano Linda Finnie. 1955 Birth of Swedish soprano Anne Sofie von Otter.

1957 FP of Chávez' "The Visitors" 1st produced in English, NY.

1961 Birth of English soprano Alison Hagley. 1961 FP of the first serious music work to be composed for the synthesizer of Robert Moog. Composer Milton Babbitt performing.

1965 Pianist Vladimir Horowitz returns to the concert stage in New York City after a twelve-year performing break, at Carnegie Hall in New York City. The audience applauded with a standing ovation that lasted for 30 minutes.

1970 FP of Bucchi's "Il coccodrillo" Florence.

1981 FP of Christopher Rouse's The Infernal Machine for orchestra aka second mmt of his Phantasmata. University of Michigan Symphony Orchestra, Gustav Meier conducting at the Evian Festival, France.

1986 FP of Ellen Taaffe Zwillich's Concerto Grosso based on Handel's Sonata in D. Handel Festival Orchestra of Washington, Stephen Simon conducting;

1990 FP of John Harbison's Words from Patterson. Texts by William Carlos Williams, with baritone William Sharp and the members of the New Jersey Chamber Music Society at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C.

1998 FP of John Tavener's Wake Up and Die at the Beauvais Cello Festival in Beavais, France.

1999 FP of Ellen Taaffe Zwillich's Upbeat!. National Symphony, Anthony Aibel conducting.

2004 FP of Michael Gordon´s Alarm Will Sound Merkin Concert Hall, NYC.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Popular 19th Century Books

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll | Faust by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe | Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson | Carmen by Georges Bizet | Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain | Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain | Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens | Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens | La Traviata by Giuseppe Verdi | Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe | David Copperfield by Charles Dickens | Symphony №9 in D Minor by Ludwig van Beethoven | Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens | Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë | Symphony №5 in C Minor by Ludwig van Beethoven | Symphony №3 in E-flat Major by Ludwig van Beethoven | Les Misérables by Victor Hugo | Aida by Giuseppe Verdi | Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë | Night Before Christmas by Clement Clarke Moore | La Bohème by Giacomo Puccini | Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen | Ivanhoe by Sir Walter Scott | Three Musketeers by Alexandre Dumas | Rigoletto by Giuseppe Verdi | Il Trovatore by Giuseppe Verdi | Barber of Seville by Gioacchino Rossini | Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens | Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi | Little Women by Louisa May Alcott | Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne | Symphony №9 in E Minor by Antonín Dvořák | Black Beauty by Anna Sewell | Symphony №6 in B Minor by Peter Tchaikovsky | Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert | Faust by Charles Gounod | Great Expectations by Charles Dickens | Symphony №7 in A Major by Ludwig van Beethoven | Symphony №6 in F Major by Ludwig van Beethoven | Tosca by Giacomo Puccini | Moby Dick by Herman Melville | Symphony in B Minor (“Unfinished”) by Franz Schubert | Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy | Symphonie Fantastique by Hector Berlioz | Symphony №1 in C Minor by Johannes Brahms | Lucia di Lammermoor by Gaetano Donizetti | Last of the Mohicans by James Fenimore Cooper | Scheherazade by Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov | Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman | Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas | Hunchback of Notre Dame by Victor Hugo | Flowers of Evil by Charles Baudelaire | Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky | Symphony №5 in E Minor by Peter Tchaikovsky | Fairy Tales by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm | Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne | Tristan and Isolde by Richard Wagner | Piano Concerto №1 in B-flat Minor by Peter Tchaikovsky | Piano Concerto №5 in E-flat Major by Ludwig van Beethoven | Norma by Vincenzo Bellini | Cavalleria Rusticana by Pietro Mascagni | Lohengrin by Richard Wagner | Martín Fierro by José Hernández | Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray | Kidnapped by Robert Louis Stevenson | Tannhäuser by Richard Wagner | Tales from Shakespeare by Charles Lamb | Heidi by Johanna Spyri | Frankenstein by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley | Nicholas Nickleby by Charles Dickens | Symphony in C Major by Franz Schubert | Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx | Capital by Karl Marx | War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy | Parsifal by Richard Wagner | Essays by Ralph Waldo Emerson | Symphony №4 in F Minor by Peter Tchaikovsky | Emma by Jane Austen | Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson | Ballo in Maschera by Giuseppe Verdi | Otello by Giuseppe Verdi | Symphony №1 in D Major by Gustav Mahler | Symphony №4 in E Minor by Johannes Brahms | Freischütz by Carl Maria von Weber | Symphony №2 in D Major by Johannes Brahms | Red and the Black by Stendhal | Walden by Henry David Thoreau | Requiem by Giuseppe Verdi | Silas Marner by George Eliot | Père Goriot by Honoré de Balzac | German Requiem by Johannes Brahms | Red Badge of Courage by Stephen Crane | Piano Concerto №1 in E Minor by Frédéric Chopin | Adventures of Sherlock Holmes by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle | Swan Lake by Peter Tchaikovsky | Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling | Valkyrie by Richard Wagner | Swiss Family Robinson by Johann Wyss | Flying Dutchman by Richard Wagner | Martin Chuzzlewit by Charles Dickens | Cyrano de Bergerac by Edmond Rostand | Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde | Lady of the Lake by Sir Walter Scott | Symphony №3 in F Major by Johannes Brahms | Violin Concerto in D Major by Peter Tchaikovsky | Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen | Quo Vadis by Henryk Sienkiewicz | Child’s Garden of Verses by Robert Louis Stevenson | Violin Concerto in E Minor by Felix Mendelssohn | Prince and the Pauper by Mark Twain | Twilight of the Gods by Richard Wagner | Last Days of Pompeii by Edward Bulwer-Lytton | Bleak House by Charles Dickens | Through the Looking Glass by Lewis Carroll | Midsummer Night’s Dream by Felix Mendelssohn | Dracula by Bram Stoker | Quintet in A Major by Franz Schubert | Old Curiosity Shop by Charles Dickens | Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky | Mill on the Floss by George Eliot | Pagliacci by Ruggiero Leoncavallo | Dombey and Son by Charles Dickens | Fledermaus by Johann Strauss | Tess of the D’Urbervilles by Thomas Hardy | Ring of the Niebelung by Richard Wagner | Little Dorrit by Charles Dickens | Winter Journey by Franz Schubert | Around the World in Eighty Days by Jules Verne | Symphony in D Minor by César Franck | Ben-Hur by Lew Wallace | Eugénie Grandet by Honoré de Balzac | Our Mutual Friend by Charles Dickens | Rheingold by Richard Wagner | Symphony №4 in E-flat Major by Anton Bruckner | Van Gogh by Vincent Van Gogh | Thus Spake Zarathustra by Friedrich Nietzsche | Lord Jim by Joseph Conrad | Siegfried by Richard Wagner | Barnaby Rudge by Charles Dickens | Adam Bede by George Eliot | Fidelio by Ludwig van Beethoven | Lorna Doone by R.D. Blackmore | Fathers and Sons by Ivan Turgenev | Piano Concerto No 1 in D Minor by Johannes Brahms | Mikado by Arthur Sullivan and W. S. Gilbert | Elijah by Felix Mendelssohn | Middlemarch by George Eliot | History of Henry Esmond by William Makepeace Thackeray | Democracy in America by Alexis de Tocqueville | Song of Hiawatha by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow | Alhambra by Washington Irving | Mansfield Park by Jane Austen | Idiot by Fyodor Dostoevsky | Hansel and Gretel by Engelbert Humperdinck | Missa Solemnis by Ludwig van Beethoven | Sketch Book by Washington Irving | Falstaff by Giuseppe Verdi | Origin of Species by Charles Darwin | Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen | Time Machine by H. G. Wells | Voyage to the Center of the Earth by Jules Verne | Nana by Émile Zola | Hard Times by Charles Dickens | French Revolution by Thomas Carlyle | Mayor of Casterbridge by Thomas Hardy | Oregon Trail by Francis Parkman | Charterhouse of Parma by Stendhal | Return of the Native by Thomas Hardy | Grammatical Institute of the English Language by Noah Webster | Eugene Onegin by Aleksandr Pushkin | Symphony №3 in C Minor by Camille Saint-Saëns | Rip Van Winkle by Washington Irving | Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court by Mark Twain | Hans Brinker by Mary Mapes Dodge | Persuasion by Jane Austen | Idylls of the King by Alfred Lord Tennyson | Far from the Madding Crowd by Thomas Hardy | War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells | Manon Lescaut by Giacomo Puccini | Moonstone by Wilkie Collins | Germinal by Émile Zola | Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde | Peer Gynt by Henrik Ibsen | Requiem by Gabriel Fauré | On Liberty by John Stuart Mill | Sonnets from the Portuguese by Elizabeth Barrett Browning | Twice-Told Tales by Nathaniel Hawthorne | Black Arrow by Robert Louis Stevenson | Villette by Charlotte Brontë | House of the Seven Gables by Nathaniel Hawthorne | Captains Courageous by Rudyard Kipling | Mysterious Island by Jules Verne | Life on the Mississippi by Mark Twain | Mystery of Edwin Drood by Charles Dickens | Invisible Man by H. G. Wells | Dead Souls by Nikolai Gogol | Turn of the Screw by Henry James | Ugly Duckling by Hans Christian Andersen | Portrait of a Lady by Henry James | Shropshire Lad by A. E. Housman | Jude the Obscure by Thomas Hardy | Innocents Abroad by Mark Twain | Legend of Sleepy Hollow by Washington Irving | Barchester Towers by Anthony Trollope | Warden by Anthony Trollope | Typee by Herman Melville | Old Mother Hubbard by Sarah Catherine Martin | Sister Carrie by Theodore Dreiser | Golden Bough by Sir James George Frazer | Emperor’s New Clothes by Hans Christian Andersen | Roughing It by Mark Twain | Voyage of the Beagle by Charles Darwin | Possessed by Fyodor Dostoevsky | On War by Carl Von Clausewitz | Interpretation of Dreams by Sigmund Freud | Three Little Pigs by Unknown | Washington Square by Henry James | Pudd’nhead Wilson by Mark Twain | Thumbelina by Hans Christian Andersen | Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy by Jacob Burckhardt | Apologia Pro Vita Sua by John Henry Newman | Age of Fable by Thomas Bulfinch | Billy Budd by Herman Melville | Nightingale by Hans Christian Andersen | Birds of America by John James Audubon | Merry Adventures of Robin Hood by Howard Pyle | Familiar Quotations by John Bartlett | American by Henry James | Looking Backward: 2000–1887 by Edward Bellamy | Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass An American Slave by Frederick Douglass | Owl and the Pussycat by Edward Lear | Steadfast Tin Soldier by Hans Christian Andersen | Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant by Ulysses S. Grant | Rise of Silas Lapham by William Dean Howells | Mythology by Thomas Bulfinch | Awakening by Kate Chopin | Hansel and Gretel by Unknown | Anatomy Descriptive and Surgical by Henry Gray | Casey at the Bat by Ernest Lawrence Thayer | Principles of Psychology by William James | Autobiography by Mark Twain | Paul Revere’s Ride by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow | Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition by Meriwether Lewis |

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

No one likes to arrive too early at a party. There’s no one to talk to and nowhere to hide. You can’t leave without being conspicuously rude. In due course you find yourself talking about car insurance (or worse still, Brexit) with other new arrivals. Of course, there’s the decor to look at (paintings you don’t much like) and there’s the buffet, tempting but as yet untouchable.

As hosts, though, we’re always grateful to those who arrive early and get things going.

New social networks have a hard time too. What’s the point of joining if no one’s there?

In gigglemusic, our new social network for classical musicians, we try to solve that problem by offering new users content that doesn’t depend on the community being large. We’ve uploaded the schedules of major classical music venues around the world (for the moment mainly opera houses).

We’ve also entered the ‘diaries’ of the world’s greatest composers – well, the greatest composers writing within the Western tradition or having some significant influence on it. By their diaries I mean their dates and places of birth and death (though many are still alive and kicking) and the dates and places of the first performances of their major works. Almost all of this comes from Wikipedia.

It may be a bit like trainspotting, but I, for one, find it mildly interesting to know where this or that masterpiece was first performed, and when.

To review a composer’s diary, start with People, open a profile, tap Diary and then scroll up to go back in time. Tap on an individual work to find out more. There’s usually a Wikipedia article to link to.

But who are the world’s greatest composers?

There’s no ideology behind the selection I’ve made, and no conscious exclusions (I’ve even included Carl Orff). They’re just the first 292 composers who came to mind, and for whom there was also a Wikipedia entry. I’m sure the assiduous researcher will detect unconscious bias, but if you do, please tell me who I’ve missed. There’s room for nearly everyone in gigglemusic.

Adam (Adolphe) Adams (John) Adès (Thomas) Albeniz (Isaac) Albinoni (Tomaso) Alwyn (William) Arne (Thomas) Arnold (Malcolm) Auric (Georges) Bach (Carl Philipp Emanuel) Bach (Johann Sebastian) Balakirev (Mily) Barber (Samuel) Bartok (Bela) Bax (Arnold) Beach (Amy) Beamish (Sally) Beethoven (Ludwig van) Bellini (Vincenzo) Bennett (Richard Rodney) Berg (Alban) Berio (Luciano) Berkeley (Lennox) Berkeley (Michael) Berlioz (Hector) Berners (Gerald (Lord)) Bernstein (Leonard) Berwald (Franz) Birtwistle (Harrison) Bizet (Georges) Bliss (Arthur) Blitzstein (Marc) Bloch (Ernst) Blow (John) Bologne (Joseph) Borodin (Alexander) Boulanger (Lili) Boulanger (Nadia) Boulez (Pierre) Bowen (York) Bozza (Eugene) Brahms (Johannes) Brian (Havergal) Bridgetower (George) Britten (Benjamin) Bruch (Max) Bruckner (Anton) Bush (Alan) Busoni (Ferrucio) Butterworth (George) Buxtehude (Dietrich) Cage (John) Canteloube (Joseph) Carter (Elliot) Chabrier (Emmanuel) Chagrin (Francis) Chaminade (Cécile) Charpentier (Gustave) Chausson (Ernest) Cherubini (Luigi) Chopin (Frédéric) Cilea (Francesco) Cimarosa (Domenico) Clarke (Rebecca) Clementi (Muzio) Coleridge-Taylor (Samuel) Copland (Aaron) Corelli (Arcangelo) Cornelius (Peter) Couperin (Francois) Cui (César) Czerny (Carl) Dallapiccola (Luigi) Debussy (Claude) Delibes (Léo) Delius (Frederick) Dittersdorf (Carl Ditters von) Dohnányi (Ernst von) Donizetti (Gaetano) Dorati (Antal) Dukas (Paul) Duruflé (Maurice) Dutilleux (Henri) Dvorak (Antonin) Einem (Gottfried von) Eisler (Hans) Elgar (Edward) Ellington (Duke) Enescu (George) Erkel (Ferenc) Falla (Manuel de) Fauré (Gabriel) Feldman (Morton) Ferguson (Howard) Ferneyhough (Brian) Field (John) Finzi (Gerald) Francaix (Jean) Franck (César) Gabrieli (Giovanni) Gershwin (George) Ginastera (Alberto) Giordano (Umberto) Glass (Philip) Glazunov (Alexander) Glière (Reinhold) Glinka (Mikhail) Gluck (Christoph Willibald) Górecki (Henryk) Gounod (Charles) Grainger (Percy) Granados (Enrique) Grieg (Edvard) Grovlez (Gabriel) Gubaidulina (Sofia) Gurney (Ivor) Haas (Pavel) Handel (George Frideric) Harty (Hamilton) Haydn (Joseph) Head (Michael) Hindemith (Paul) Hoddinott (Alun) Holliger (Heinz) Holst (Gustav) Honegger (Arthur) Howells (Herbert) Hummel (Johann Nepomuk) Humperdinck (Engelbert) Ibert (Jacques) Indy (Vincent d’) Ireland (John) Ives (Charles) Jacob (Gordon) Janacek (Leos) Jolivet (André ) Joplin (Scott) Kalivoda (Jan) Kálmán (Emmerich) Khachaturian (Aram) Knussen (Oliver) Kodaly (Zoltan) Koechlin (Charles) Korngold (Erich) Krenek (Ernst) Krommer (Franz) Kurtág (György) Lalo (Édouard) Lang (David) Lauridsen (Morten) Leclair (Jean-Marie) Lehár (Franz) Leifs (Jón) Leigh (Walter) Leoncavallo (Ruggero) Ligeti (Gyorgy) Liszt (Franz) Loeillet (Jean Baptiste) Lyadov (Anatoly) Mahler (Alma) Mahler (Gustav) Marcello (Alessandro) Martin (Frank) Martinu (Bohuslav) Mascagni (Pietro) Massenet (Jules) Maxwell Davies (Peter) Medtner (Nikolai) Mendelssohn (Felix) Menotti (Gian Carlo) Messiaen (Olivier) Meyerbeer (Giacomo) Milhaud (Darius) Moeran (Ernest) Monteverdi (Claudio) Morricone (Ennio) Moyzes (Alexander) Mozart (Wolfgang Amadeus) Mussorgsky (Modest) Nancarrow (Conlon) Nielsen (Carl) Nono (Luigi) Nyman (Michael) Offenbach (Jacques) Orff (Carl) Pachelbel (Johann) Paderewski (Ignacy Jan) Paganini (Niccolò) Paisiello (Giovanni) Palestrina (Giovanni Pierluigi da) Panufnik (Andrzej) Parry (Hubert) Pärt (Arvo) Pasculli (Antonio) Penderecki (Krzysztof) Pepusch (Johann Christoph) Pergolesi (Giovanni) Piazzola (Astor) Poulenc (Francis) Previn (André) Price (Florence) Prokofiev (Sergei) Puccini (Giacomo) Purcell (Henry) Quantz (Johann Joachim) Quilter (Roger) Rachmaninoff (Sergei) Raff (Joachim) Rameau (Jean-Philippe) Ravel (Maurice) Reger (Max) Reich (Steve) Reinecke (Carl) Reizenstein (Franz) Respighi (Ottorino) Richardson (Alan) Riley (Terry) Rimsky-Korsakov (Nikolai) Rodrigo (Joaquín) Rossini (Giacomo) Rota (Nino) Rubbra (Edmund) Saint-Saëns (Camille) Salieri (Antonio) Sammartini (Giovanni Battista) Satie (Erik) Scarlatti (Domenico) Schnittke (Alfred) Schoeck (Othmar) Schoenberg (Arnold) Schubert (Franz) Schumann (Clara) Schumann (Robert) Scriabin (Alexander) Sessions (Roger) Shostakovich (Dmitri) Sibelius (Jean) Sinding (Christian) Skalkottas (Nikos) Smetana (Bedrich) Smyth (Ethel) Sondheim (Stephen) Sorabji (Kaikhosru Shapurji) Spohr (Louis) Stanford (Charles Villiers) Stenhammar (Wilhelm) Still (William Grant) Stockhausen (Karlheinz) Strauss (Johann) I Strauss (Johann) II Strauss (Richard) Stravinsky (Igor) Suk (Josef) Sullivan (Arthur) Sweelinck (Jan Pieterszoon) Szymanowski (Karol) Tailleferre (Germaine) Takemitsu (Toru) Tallis (Thomas) Tavener (John) Tchaikovsky (Pyotr) Tcherepnin (Alexander) Tcherepnin (Nikolai) Telemann (Georg Philipp) Thompson (Virgil) Tippett (Michael) Tubin (Edward) Turnage (Mark-Anthony) Varese (Edgard) Vaughan Williams (Ralph) Verdi (Giuseppe) Vierne (Louis) Villa-Lobos (Heitor) Vivaldi (Antonio) Wagner (Richard) Walker (George) Walton (William) Warlock (Peter) Weber (Carl Maria von) Webern (Anton) Weelkes (Thomas) Weill (Kurt) Weir (Judith) Widor (Charles-Marie) Williams (John) Williamson (Malcolm) Wolf (Hugo) Xenakis (Iannis) Ysaÿe (Eugène) Yun (Isang) Zelenka (Jan Dismas) Zemlinsky (Alexander von)

The Great Composers No one likes to arrive too early at a party. There's no one to talk to and nowhere to hide.

0 notes

Text

“L’arte fa paura a chi ha smarrito l’etica della responsabilità comune, perché è svelamento della verità e della coscienza dell’uomo”. Francesco Consiglio dialoga con il pianista Alessandro Marangoni

“Se togliamo ai nostri figli la possibilità di avvicinarsi all’arte, alla poesia, alla bellezza, in una sola parola alla cultura, siamo destinati a un futuro di gente superficiale e pericolosa. Per questo occorre difendere un settore che non esiste per dare dei profitti, ma per parlare direttamente alla gente”. Queste parole di Riccardo Muti racchiudono il principio fondamentale che guida il mio lavoro di scrittore avventurosamente votato, per autoinvestitura, al ruolo di divulgatore musicale. E che Dio mi abbia in gloria! Bisogna scrivere di musica non solo per invogliare ad ascoltarla o suonarla, ma soprattutto per educare le persone a vivere musicalmente, con creatività e gentilezza, aprendosi agli altri come se la vita di ognuno fosse una partitura di singole note capaci di restituire bellezza quando vengono suonate insieme. La grande musica, sia essa di Bach, di Liszt o Rossini, apre la mente all’immaginazione, e chi sa immaginare coltiva bei sogni e riesce più facilmente a raggiungerli.

Alessandro Marangoni, pianista, si è diplomato col massimo dei voti, lode e menzione presso il Conservatorio ‘Antonio Vivaldi’ di Alessandria. Ha debuttato nel dicembre 2007 con un recital al Teatro alla Scala di Milano, in un omaggio a Victor de Sabata nel 40° anniversario della morte, insieme al pianista e direttore d’orchestra Daniel Barenboim. Ha suonato in Spagna con l’Orchestra Filarmonica di Malaga e a Bratislava con l’Orchestra Filarmonica Slovacca, sotto la direzione di Aldo Ceccato; ha inoltre diretto l’Orchestra ‘I Pomeriggi Musicali’ di Milano. Nella sua produzione discografia, spiccano i 13 CD dell’integrale completa dei Péchés de vieillesse di Gioacchino Rossini, l’integrale del Gradus ad parnassum di Clementi, l’Evangélion (The Story of Jesus) di Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, e la Via Crucis di Liszt (con il coro polifonico ‘Ars Cantica Choir’).

Diversi musicisti mi hanno confessato di essersi trovati, da bambini, su una strada che non avevano liberamente scelto di percorrere, senonché a un certo punto, crescendo, era scoccata la scintilla verso il proprio strumento. Questo succede perché si inizia a suonare molto presto, spinti dai genitori, e dunque gli studi musicali hanno due sbocchi: possono favorire una grande storia d’amore per la musica oppure trasformarsi in una coercizione che genera un senso di rifiuto e opposizione verso chi la pretende. Tra lei e il pianoforte è stato un colpo di fulmine o un processo più lungo, discontinuo, maturato per tappe successive?

Ho iniziato a suonare a cinque anni ed è stata una mia richiesta, anche piuttosto insistente: i miei genitori spesso mi portavano ai concerti e fui subito attratto dalla musica. Quando mi noleggiarono il primo pianoforte verticale in realtà mi aspettavo un organo a canne e piangevo perché non c’erano le canne, forse perché spesso andavo a sentire l’organo che suonava in chiesa. Ma poi fu subito amore per il pianoforte: studiavo con molto piacere e naturalezza, non mi è stato imposto nulla.

Trova normale (oh sì: è normale ma non certamente etico) che un politico sia a capo di una fondazione lirico-sinfonica e decida di sostituire un manager per puro opportunismo? Si sostiene che l’arte costa troppo e ha un pubblico sempre più ristretto, ma le perdite di bilancio sono uno strumento di ricatto: la Politica eroga finanziamenti, peraltro sempre più risicati, e in cambio pretende di diventare padrona della scena. La presidenza della fondazione lirica è attribuita di diritto al Sindaco del Comune in cui ha sede la fondazione stessa. E tra i membri del consiglio di amministrazione, uno è nominato dalla Regione e uno dal governo. Tutta gente per la quale sedersi in platea è solo passerella. Non crede che sarebbe più giusto restringere il ruolo dei burocrati e restituire la musica ai musicisti?

La storia è piena di questi colpi bassi alla grande musica, perché manca un’etica della responsabilità. I politici a volte sostengono cose assurde, frutto di demagogia o, spesso, di ignoranza. Dire che l’arte costa troppo è da un lato ridicolo, perché penso sia una delle spese minori che abbia uno Stato, dall’altro è criminale e diabolico, perché frutto di falsità e di una deliberata volontà di cancellare ciò che è bello e che è buono (e la Musica Forte piace alla gente, lo dimostrano i numeri!). L’arte può fare paura a chi ha smarrito l’etica della responsabilità comune perché è svelamento della verità e della coscienza dell’uomo che fa tremare chi fa il tifo invece per il disumano (o per chi vuole fare i propri interessi a scapito della collettività, della polis). L’Italia ha inventato le note musicali, il primo conservatorio del mondo è sorto a Napoli, abbiamo dato i natali ai più grandi musicisti di ogni tempo: basterebbe questo per ricordare a chi governa che l’investimento più importante del Paese è la Cultura, di cui la musica è uno degli elementi più significativi: porta lustro al Paese e anche ricchezza, turismo, civiltà, investimenti. Ogni volta che suono all’estero sono sempre accolto e coccolato con affetto e stima anche perché italiano! La musica dovrebbe essere presente fin dagli asili nido come elemento fondante l’educazione e la crescita dell’individuo, per creare una società migliore. Non è poi tutta negativa la situazione musicale italiana: conosco luoghi come ad esempio il Collegio Borromeo di Pavia dove la maggior parte del pubblico è composto da giovani, pieni di curiosità e di entusiasmo, e ai concerti si sentono urla da stadio!

Wilhelm Furtwängler, uno dei maggiori direttori d’orchestra del XX secolo, non aveva una grande opinione del pubblico che affollava le sale di concerto, e arrivò a dichiarare che si trattava di masse amorfe che reagivano inconsideratamente e quasi automaticamente a qualsiasi suggestione. Un atteggiamento di apparente disprezzo che Furtwängler giustificava così: “Occorre tempo per conoscere veramente un’opera. È difficile stabilire quanto tempo richieda un tale processo di comprensione e di chiarificazione, sia per un’opera musicale che per un artista. Esso può svolgersi per decenni e anche per un’intera vita. Basti citare Bach, le ultime opere di Beethoven, artisti come Bruckner”. Si tratta di una tesi affascinante ma al tempo stesso pericolosa, perché anestetizza lo spettatore sottraendogli il diritto alla critica.

Parlo per esperienza personale: il pubblico, qualsiasi pubblico, di ogni età ed estrazione sociale, capisce il valore e la bellezza della musica dopo poche note, perché la musica, se fatta bene, arriva dritta al cuore dell’uomo, prima ancora che all’intelligenza. Gli artisti non devono andare incontro al pubblico, lo devono guidare e devono essere un po’ ‘profeti’. Il pubblico vuole essere condotto, vuole conoscere cosa sta dietro una partitura, vuole lasciarsi emozionare, sta con gli occhi spalancati a vedere chi suona o dirige sul palcoscenico. Chiaramente c’è anche chi ascolta criticamente, volendo capire magari come è fatta una Fuga del Clavicembalo ben temperato di Bach, ma si tratta di una minoranza, soprattutto in Italia. Sono d’accordo sul fatto che ci vogliano decenni, magari non basta una vita per comprendere una Sonata di Beethoven o di Schubert, perché sono opere scritte da geni, personalità straordinarie con abilità intellettive non comuni, ma per apprezzare ed essere mossi ed emozionati da questa musica basta solo qualche ascolto attento. Invece credo che l’interprete abbia un compito molto più difficile rispetto al pubblico che recepisce la musica: bisogna essere molto preparati, studiare molto, conoscere di tutto, non solo la musica, andare a fondo per cercare di interpretare al meglio il volere del compositore. I musicisti hanno una grandissima responsabilità!

La sua incisione più importante, di certo la più imponente, è l’integrale discografica dei Peccati di vecchiaia, i Péchés de vieillesse di Gioacchino Rossini. Ben 14 CD, sette anni di ricerche che hanno prodotto un lavoro di grande valore non solo musicale ma anche storico, data la presenza di alcuni inediti. Tutto questo per ricordare al pubblico che Rossini non è soltanto un grande operista. Esiste un vasto repertorio di composizioni pianistiche destinate agli amici che andavano a trovarlo nella sua casa di Parigi. Brani dai titoli curiosi, come il Preludio igienico del mattino o il Piccolo valzer dell’olio di ricino. L’ironia rossiniana è la sola medicina in grado di cancellare quell’immagine di seriosità noiosa che spesso accompagna la musica cosiddetta seria.

Ascoltando (e suonando) Rossini è davvero impossibile annoiarsi! Innanzi tutto perché è del tutto imprevedibile, cambia in continuazione, non si stanca mai di trovare nuove idee, soluzioni innovative, non smette di stupire. Egli diceva: “La mia musica fa furore”, ed è proprio così anche oggi quando ascoltiamo queste gemme preziose che sono i Peccati di vecchiaia. Senza nessuna volontà di guadagno e senza ingaggi e commissioni, Rossini scriveva per la gioia di farlo, perché non poteva farne a meno, libero da ogni condizionamento. E qui nascono le sue cose migliori, dove si svela l’uomo Rossini, più ancora che nell’opera lirica. È musica piena di intelligenza, quindi di ironia, molto spesso anche di autoironia (pensiamo al pezzo che scrisse per il suo funerale!). Citerei un brano per tutti: il Petit caprice style Offenbach, in cui chiede al pianista di suonare il tema facendo le corna, poiché pensava che Offenbach portasse sfortuna: un esempio emblematico di come, nella sua immensa sapienza fuori dall’ordinario, Rossini ha saputo farci sorridere e insieme commuovere, mettendo a nudo quei tratti dell’umanità comuni a tutti e che non hanno tempo.

A un giovane esponente della musica trap, che va fortissima tra i millenials, non capiterà mai di sentirsi negare il diritto all’esistenza artistica perché un tempo ci furono un Modugno e un De Andrè migliori di lui. Stessa benevolenza non viene riservata ai giovani compositori della classica contemporanea. Nei foyer dei teatri e nelle platee s’udirà uno spettatore dire in un orecchio al vicino: “Eh, sì, ma allora Mozart? E Bach? E Beethoven? Quelli sì che erano musicisti”. È d’accordo con me nel ritenere che i compositori di oggi siano schiacciati dai paragoni con gli immortali della musica?

Credo innanzi tutto che oggi abbiamo grandi compositori viventi, che sicuramente passeranno alla storia, anche in Italia, dove esiste una grande scuola di composizione. Ma sarebbe come per uno scrittore contemporaneo di romanzi paragonarsi a Manzoni, o per un poeta a Dante. All’epoca di Mozart c’erano moltissimi compositori eccezionali come lui, che ebbero anche molta più fortuna di Wolfgang ma che oggi pochi ricordano; Bach per più di un secolo fu quasi del tutto sconosciuto se non ci fosse stato Mendelssohn a riscoprirlo. Credo che in ogni piega della storia ci siano state e ci sono persone dotate di una speciale intelligenza e di un carisma artistico non comune, ma anche tanti bravissimi musicisti che si esprimono attraverso la loro arte, nel lavoro quotidiano e artigianale. Un altro elemento importante e fondamentale credo sia l’umiltà, che significa anche darsi da fare: humilitas alta petit diceva San Carlo Borromeo.

Infine, la più scontata e inevitabile delle domande: progetti per il futuro?

Continuare a stupirmi e a gioire nel far musica, cercando di donare al mio pubblico questa meravigliosa arte al meglio delle mie capacità e col mio talento.

Francesco Consiglio

*In copertina: Alessandro Marangoni in un ritratto fotografico di Daniele Cruciani

L'articolo “L’arte fa paura a chi ha smarrito l’etica della responsabilità comune, perché è svelamento della verità e della coscienza dell’uomo”. Francesco Consiglio dialoga con il pianista Alessandro Marangoni proviene da Pangea.

from pangea.news https://ift.tt/2QKsOid

0 notes

Text

El lado desconocido de la música occidental

Romanticismo y posromanticismo

Todas las artes se basan en dos principios: la realidad y la idealidad

-Franz Liszt

Sin duda alguna, una de las épocas más trascendentes y significativas de la música fue aquella en la que se desarrollaron los periodos romántico y posromántico. Los sonidos de la música de los compositores representantes de estos periodos suelen ser tan brillantes y coloridos que no se puede ser indiferente ante ellos. La música, en sí, logra por primera ocasión tener significados profundos e intencionales en base a los sentimientos e ideologías de los propios autores, los cuales sentían la necesidad de comunicarlos por medio de este arte. Los románticos de la primera generación (abordados en la columna anterior) fueron los encargados de abrir el camino para que los del periodo tardío y posromántico se desarrollaran como lo hicieron, ya que incursionaron en nuevos aspectos, pero nunca dejaron de seguir la línea trazada desde el inicio. Uno de los aspectos más representativos de este periodo fue el de tocar música de compositores fallecidos por intérpretes virtuosos en series de conciertos. Actualmente, esta sentencia puede parecer ridícula, pero hay que recordar que, para ese punto de la historia, únicamente se tocaba música de autores vivos.

Uno de los intérpretes más asombrosos y de los compositores más innovadores del S.XIX fue claramente Franz Liszt (1811-1886). Liszt fue uno de los primeros en explotar la técnica pianística; fue el primer pianista en presentarse en una sala de concierto tocando un repertorio desde Bach hasta sus contemporáneos e igualmente, fue quien le dio a este tipo de concierto el nombre de recital. Durante la primera mitad de su vida, Liszt de dedicó a dar recitales, sin embargo, decidió concentrarse puramente en la composición a partir de 1848. En sus obras, Liszt exploró nuevas técnicas y texturas del piano, a decir verdad, gran parte de su música en para este instrumento. No obstante, Franz en Années de pèlerinage se propuso tomar varias obras de arte, admirarlas, interpretarlas, trabajarlas y así, hacer música con ellas. Se sabe que hizo esto con pinturas y sonetos de Petrarca y Dante. Por último, no puedo dejar de mencionar que Liszt fue el creador del poema sinfónico y que en sus piezas suele haber un constante uso de melodías húngaras.

Si Liszt ayudó considerablemente a la música en cuestiones interpretativas y estructurales, Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) fue aquel que contribuyó en la línea orquestal. Berlioz era un hombre muy tenaz, prueba viviente de ello fue cuando él mismo se autoproclamó su propio empresario y consiguió que su música se interpretase en conciertos organizados por él. Hector era un ávido lector, por tal motivo, muchas de sus composiciones están inspiradas en obras de Virgilio, Shakespeare y Walter Scott, por mencionar algunos. Berlioz, a parte de componer, se dedicaba a hacer crítica musical y a escribir sobre música. A propósito, al escribir su tratado de orquestación, marcó el inicio de una nueva época en la que el timbre instrumental pasaba a hacer igual de importante que la armonía y melodía.

Probablemente, uno de los compositores más reconocidos del posromanticismo sea Richard Wagner (1813-1883). Wagner es uno de los músicos más influyentes de todos los tiempos, con él, la ópera alemana se transformó y revolucionó al grado de que se le cambiase el nombre por drama musical. En 1830 es cuando Richard comienza a componer óperas, entre sus producciones más importantes están Tristan y Solda, el anillo del Nibelungo, el Holandés Errante y los maestros cantores de Nüremberg. Además de componer música, Wagner escribía ensayos sobre temas literarios, teatrales y políticos, uno de sus ensayos más importantes es el titulado La obra de arte del futuro. De igual manera, Richard tiene varios escritos antisemitas gracias a su ideología nacionalista arraigada, de hecho, varios investigadores han llegado a la conclusión que varias de sus óperas tienen un trasfondo antisemita. Regresando al tema musical, Wagner es reconocido por haber inventando el Leitmotiv (motivo conductor). Según Richard, los dramas musicales están organizados en torno a una idea o motivo concreto que los hace funcionar y que es el material básico.

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) fue en definitiva el compositor más conservador del posromanticismo porque a él, en concreto, no le interesó innovar, sino que se concentró en retomar las obras maestras clásicas e inyectarles las nuevas tendencias de su época para así crear una música refinada y estética. Brahms es conocido por poseer una sensibilidad romántica impecable. Un dato interesante de la carrera de Brahms es que, durante sus primeros años de carrera, se reusó mucho a componer sinfonías porque se sentía abrumado, al pensar que jamás iba a alcanzar lo que Beethoven había logrado en su 9na. A pesar de u pensamiento, en 1876 termina su primera sinfonía que termina siendo un éxito. Entre las obras más importante de Johannes está su Requiem alemán. A diferente a los réquiems de otros compositores, el de Brahms no utiliza textos litúrgicos propios de la misa de difunto, sino que la letra está basada en pasajes tomados del antiguo testamento, de los textos apócrifos y del nuevo testamento.

No se puede hablar del posromaticismo sin mencionar a Anton Bruckner (1824-1896). Bruckner es indiscutible uno de los mejores sinfonistas que la música haya tenido. La orquestación usada por Anton en sus obras es sumamente portentosa y deslumbrante, sabía combinar con maestría los timbres de los instrumentos para que éstos sonaran en conjunto y, del mismo modo, destacaran en individual. Se puede decir que, con Bruckner, todos los instrumentos entran en el lugar y momento idóneo. Anton era organista, lo cuál es una razón muy buena para sospechar del porqué sabía usar tan bien las voces. Bruckner fue un compositor muy devoto, razón por la cuál sus obras religiosas son de una grandeza impresionante. En ellas logra combinar elementos modernos con elementos antiguos de la polifonía renacentista. La mayoría de sus obras religiosas están hechas para poder fusionarse con la liturgia.

Finalmente, después de haber escrito lo anterior, puedo asegurar que escuchar música romántica significa dejarse llevar por los sentidos. Para los compositores de este periodo, no hubo mayor ideal que no fuera el de buscar que la música llegará a lo más profundo de la intimidad del alma para que los oyentes pudieran experimentar las sensaciones que ellos se proponían expresar. Por mi parte, es imposible mencionar en un conjunto de columnas a todos los compositores que permitieron que el periodo llegara a hacer lo que conocemos, pero sí trate de incluir a los más representativos. Entre los que deje de lado, puedo mencionar a Chopin, Donizetti, Rossini, Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini y César Frank. Por último, es importante recalcar que la característica fundamental del romanticismo tardío y posromántico fue que la música, por primera vez, no siguió solamente una forma compositiva y estructural, ni mucho menos un estilo, sino que en cada región se fueron surgiendo prácticas y escuelas diferentes.

---Pau Mendoza---

Lista de escucha

*Franz Liszt

https://open.spotify.com/album/2gdcNy4sHAuh4MQHGCqJAZ?si=5rsq3iGBQc6PtFnVWwBoSg

https://open.spotify.com/album/1ZzaUt3KWiUzvIcOn4NYGW?si=Q7mjlYi2TjGbdlxpQXB68Q

https://open.spotify.com/album/20VpNIIIwb0gMtF8Xr2bjf?si=AlBp0LEiS8O6VaIB7tmplw

https://open.spotify.com/album/1XUdVl1s9jMdW4pEVWLf34?si=kMcawaRgTb25125phI2wzg

https://open.spotify.com/album/4coJv1Sjv309k5otI5xNvq?si=XrD6jKmlQSmGiFkP6ETmWg

Hector Berlioz

https://open.spotify.com/album/1fv3bpx1zPfXM2apaduE2U?si=GioxTaD6Qm6tesB9J-VJHA

https://open.spotify.com/album/1XXt8Vc3fKiQpwz4Tpui1o?si=biq2hhOqRUej_DO877RdKg

https://open.spotify.com/album/4Fspe7SSH1V7Ls9Y6BCRXI?si=ltEhnVqtTICCuYvlh2UMuw

Wagner

- https://open.spotify.com/album/1EZQ4VfnQRvZq07sI2UlLD?si=-Ym3geVrTKaOqSTUzhxFpA

- https://open.spotify.com/album/0MGf7KlOt8wNA9c7n0TNbx?si=HnKllh3-Tmq7YtRAu_npvw

https://open.spotify.com/album/4IwO6GAWg4hCyAhKMaADJd?si=LoolE6RqRWKYHjmiNazl_g

https://open.spotify.com/album/2BwDETrPtINRoAI1aLS26m?si=JdJmTGCGQSOd2aQoiJHZ3g

Brahms

https://open.spotify.com/user/bazdra/playlist/22h3aeH5pKgYv0qLCd3bhq?si=K_cdmUVAQkORDO1udA46-g

https://open.spotify.com/album/5D0QnwFy75f9GX5Il95qT1?si=KTydnYRPQC2PAgpbS_AZxw

https://open.spotify.com/album/60EuOHjCxSzytQi88N5j9k?si=byd_4ekxRECN27lRlY7Bxw

https://open.spotify.com/album/0b0rUR3Hjhb2IJSBPRFBlH?si=xMquh0VTTxqb_VDuc-FY4w

https://open.spotify.com/album/12f34eRSWeo6AQ9ceBqbpH?si=8AL7AefORjOcwrnh6Vxpzw

Bruckner

https://open.spotify.com/album/2Q2FzUnB2EbiwVkqahA8pB?si=_99Dm7exQdmNdyrQVEdWCg

https://open.spotify.com/album/7nU70nUBYziBt9F9tawvCi?si=30nBwY48RXeP61tcOaw0Ug

https://open.spotify.com/album/3gGKmo7LTNC3XgFG1VtesU?si=VVbMfi0fS7OmnQBK_zA6Hw

https://open.spotify.com/album/5spZzioClVMRZ0MI6RS7xl?si=EG6eLFxGQX2efmqch3Hcaw

https://open.spotify.com/album/3RY00OixSTBw74GjalsXBg?si=CoYyW2-QQwCnj_20FYyuPA

0 notes

Text

Cor Vivaldi, Lisa Campos i Núria Prats Conservatori del Liceu 20 d egener de 2018. Fotografia IFL

Lisa Campos-Cor Vivaldi 20 de gener de 2018 Conservatori del Liceu Fotografia IFL

Núria Prats-Cor Vivaldi 20 de gener de 2018 Conservatori del Liceu. Fotografia IFL

Cor Vivaldi Conservatori del Liceu 20 d egener de 2018. Fotografia IFL

No vaig poder assistir al concert de tardor del Cor Vivaldi i finalment no hi va poder haver la tradicional crònica que de fa anys no deixa de ser un clàssic a IFL, però sortosament en aquesta ocasió i amb dies obres absolutament desconegudes per a mi, el discret Stabat Mater del compositor bohemi Jan Křtitel Vaňhal i les bellíssimes Vesperae pro festo Sancti Innocenti de Johann MIchael Hyadn, el germà petit del gran Franz Joseph.

Dues obres quasi coetànies però estèticament allunyades una de l’altra. La de Vaňhal encara ancorada en un barroc tardà mentre que la de Haydn jr, ja amb la mirada posada en el període clàssic, prenent una consistent volada que de no ser per la fama merescudíssima del seu germà gran, de ben segur avui seria més considerada i coneguda.

En les dues obres el Cor Vivaldi va està acompanyat per la Vivaldi Camerata, una formació instrumental formada per a un quartet de corda (2 violins, viola i violoncel) i dues trompes, amb l’acompanyament a l’orgue d’Arnau Farré, habitual i imprescindible en la immensa majoria dels concerts vivaldians. I també en les dues obres són importants les intervencions solistes, sobretot en el Stabat Mater i per aquesta obra el mestre Òscar Boada va triar a dues de les principals veus del cor: la soprano Lisa Campos i la mezzo Núria Prats per fer front a les 7 àries i al duet amb cor, de les 12 parts que formen aquesta obra. Va fer bé perquè elles dues van saber defensar amb molta seguretat el compromís, tot i l’exigència en el cant ornamentat i la coloratura, que requereix l’obra i que no és gaire habitual en el repertori i l’estil que sovinteja el Cor Vivaldi. En aquest sentit la tasca de Pilar Paredes, professora de cant del cor, va ser especialment meritòria, perquè si bé en alguns passatges va faltar aquella destresa habitual en les cantants adultes, la solvència i la correcció estilística hi eren, sobretot en Lisa Campos, ja coneguda solista de la casa i a qui l’obra de Vaňhal reserva la major exigència, més que no pas la part per a mezzo o contralt, ben projectada per Prats però sense l’ocasió de brillar tant com la seva companya.

L’obra no és gran cosa, certament, però com va dir el mestre Boada abans de començar, en les delicioses xerrades didàctiques que tant s’agraeixen per crear un clima d’atenció preconcert, s’escolta amb interès perquè és agradable melòdicament i formalment impecable.

La interpretació va ser una mica irregular, sobretot perquè la formació instrumental no va estar a l’alçada de la coral. Semblava talment que estàvem en dos móns diferents d’exigència i de resultats. Si bé és cert que el Vivaldi sempre està a un nivell alt, en aquesta obra vaig notar una manca de’equilibri entre les potents sopranos (poderosos i segurs aguts) i les mezzos i contralts, més apagades, tot i que sempre correctes.

L’obra em va semblar poc adequada per incloure-la en un concert del cor, ja que en realitat aquest només té 5 intervencions de les 12 i la resta recau, com ja he dit en les solistes, i malgrat la solvència en les resultats d’aquestes, crec que l’evident esforç no va lluir com calia, per les característiques de l’obra i per la distància que separava la interpretació coral de la instrumental

La segona part va suposar un canvi radical. En primer lloc perquè l’obra de Haydn jr em va semblar molt millor que la de Vaňhal, però també perquè tot el protagonisme, malgrat les parts solistes aquí interpretades a la manera vivaldiana, és a dir amb la intervenció estimulant de moltes de les integrants (en aquesta ocasió no hi havia representants masculins), són pel cor. L’obra semblava molt més preparada i cohesionada que l’Stabat Mater de la primera part, i fins i tot la formació orquestral va sonar més conjuntada, afinada i cohesionada amb el cor.

Tota una descoberta aquestes vespres que gràcies al mestre Boada i la sempre estimulant programació que proposa la temporada de les quatres estacions vivaldianes (concerts de tardor. hivern, primavera i estiu), sempre farcides d’obres estimulants i de resultats, com aquest cas brillants.

La propera ocasió serà el 21 d’abril amb obres de Brahms Schumann, Anton Bruckner i Felix Mendelssohn, sota la direcció del mestre Salvador Mas, i el d’0estiu serà el 30 de juny amb la interpretació de la fabulosa Petite Messe Solennelle de Rossini. Ambdós concerts, com tots els que d’aquesta temporada, en la millor sala acústica de la ciutat, la del Conservatori del Liceu. No hi falteu perquè el nivell i l’interès que ofereixen res tenen a veure amb el adotzenament de l’activitat musical de la ciutat.

Us deixo escoltar el Memento de les Vesperae pro festo Sancti Innocenti, tal i com va ser interpretat pel Cor Vivaldi en el concert d’ahir

[audio https://ximo.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/memento-jm-haydn.mp3]

L’àudio és gentilesa del Cor Vivaldi que pagant una quantitat simbòlica te l’envien a casa porques hores després d’haver acabat el concert, en una iniciativa magnífica.

CONCERT D’HIVERN DEL COR VIVALDI 2017/2018: Jan Křtitel Vaňhal i Johann Michael Haydn No vaig poder assistir al concert de tardor del Cor Vivaldi i finalment no hi va poder haver la tradicional crònica que de fa anys no deixa de ser un clàssic a IFL, però sortosament en aquesta ocasió i amb dies obres absolutament desconegudes per a mi, el discret…

#Òscar Boada#Conservatori del Liceu#Cor Vivaldi#Jan Křtitel Vańhal#Johann Michael Haydn#Lisa Campos#Núria Prats

0 notes

Text

Things to do in Montréal from June 2 to 8

It’s still officially spring, but Montréal summer festival season kicks off this week with outdoor music, dancing and F1 parties. Also see the city’s history rendered in light, the sights of Expo 67, circus and theatre, award-winning classical musicians and more.

youtube

375th birthday celebrations

Watch Montréal history come to life on the Saint Lawrence River in spectacular, free multimedia show Montréal Avudo every night in the Old Port. From there you’ll also see the city’s high-tech 375th anniversary light show on the Jacques-Cartier Bridge. The Orchestre symphonique de Montréal under conductor Kent Nagano plays a Symphony for Montréal, with visuals by Moment Factory, June 2 at Maison Symphonique. Old Montréal landmark Notre-Dame Basilica, one of the city’s most stunning churches, lights up with beautiful high-tech spectacle Aura, while the surrounding streets illuminate with the historic tableaux projections of Cité Memoire. And La Grand Tournée weekend events, presented by Cirque Éloize, run throughout the summer and in every neighbourhood, from group picnics in the park and green alleyway tours to circus shows and cinema under the stars.

Outdoor fun

The first First Fridays of the season turns Olympic Park into a giant food truck rally with music and family-friendly things to do on June 2. Ubisoft video game giant hosts L’été Mile End on June 3, with live music, games and a kids zone. Urban green space, outdoor eatery and bar in the heart of downtown Les Jardins Gamelin hosts music performances, dance classes, family activities and more. While downtown, grab a bite from one of Montréal’s great food trucks or pop by the Marché des Éclusiers market in the Old Port for a meal, a drink, local produce and other creations. Drop by Village au Pied du Courrant next to the Jacques Cartier Bridge for music, food and socializing. Join the crowds of cyclists in the streets during the Go Bike Montréal Festival‘s massive public bike rides Tour de l’Île on June 4 and Tour la Nuit on the night of June 2. The F1 Grand Prix festivities begin June 8 at the free Crescent Street Grand Prix Festival and Peel Formula downtown, featuring DJs, fashion shows, driver appearances and more. Take a walk up traffic-free Saint-Laurent Boulevard during Mural Fest, June 8-18, when you can watch artists paint new works on buildings’ walls. Discover the great tunes of French-language music festival Les Francofolies, opening June 8 with Les Trois Accords, Dumas, Pierre Kwenders and Lydia Képinski in a free outdoor concert in Place des Festivals. Find more outdoor activities in our guide to free things to do this Spring in Montréal.

Expo 67 returns

Montréal celebrates the 50th anniversary of Expo 67 with entertaining and history-rich exhibitions: see colourful outfits and products created by Québec designers at the McCord Museum’s Fashioning Expo 67; photographs tell the tale in The Sixties in Montréal: Archives de Montréal at City Hall; marvel at the technological innovations of EXPO 67: A World of Dreams at the Stewart Museum and Écho 67 at the nearby Buckminster Fuller designed Biosphère; baby boomer youth culture is a blast in Explosion 67 – Youth and Their World at the Centre d’histoire de Montréal; it’s all about ’60s artistic expression in the Montréal Museum of Fine Arts’s Révolution: “You say you want a revolution” and the Musée d’art contemporain’s In Search of Expo 67; Arcmtl presents Expo 67: Avant Garde! – forward-looking, boundary-breaking art of the ’60s at the Cinémathèque Québecoise; and Centre de design de l’UQAM honours architect Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67 in The Shape of Things to Come. Photography exhibition Aime comme Montréal celebrates the city’s diversity in an installation at Place des arts.

youtube

On stage

Prepare to be dazzled and delighted at Cirque du Soleil’s VOLTA, the most exciting circus around – see acrobats, dancers, parkour experts, motor bike athletes and many more incredible performers under the big top in the Old Port of Montréal. Expect extraordinary, boundary-pushing performances in dance, theatre and art at the international FTA – Festival TransAmériques, including major Polish director and set designer Krystian Lupa’s Wycinka Holzfällen – Woodcutters, Marie Brassard’s La fureur de ce que je pense, Barcelona company El Conde de Torrefiel’s Possibilities that Disappear Before a Landscape, incredible contemporary dance, parties and more. Les Grands Ballets presents the contemporary dance of Jiří Kylián’s Falling Angels and Evening Songs in a triple bill with Stephan Thoss’s Searching for Home, at Place des Arts to June 3. For more theatre, eclectic performances and parties than you can shake a silly stick at, go to the St-Ambroise Montréal Fringe Festival, including a Fringe Prom on June 2, and and a Mini Fringe afternoon for kids and evening opening concert on June 8 at Fringe Park.

youtube

Art and film

Colour and music converge in CHAGALL: COLOUR AND MUSIC at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Hajra Waheed’s The Video Installation Project 1–10 and collections-based Pictures for an Exhibition intrigue at the Musée d’art contemporain and Mexican artist Gilberto Esparza’s Plantas autofotosintéticas has us rethinking how biology, technology and art intersect, at Galerie de l’UQAM. British artist Ed Atkins poses questions on human bodies, digital creation and reality in video exhibition Modern Piano Music at DHC-ART. Pointe-à-Callière archaeology and history museum presents the fascinating Amazonia: The Shaman and the Mind of the Forest. And Parisian Laundry gallery presents intuitive experimental new work by collective BGL. On screen: A full orchestra and choir accompanies Milos Forman’s Oscar-winning film Amadeus at Place des Arts, June 2-3. The Montreal Israeli Film Festival opens with Past Life on June 4 and runs to June 15. Travel through virtual worlds in Felix & Paul Studios Virtual Reality Garden at the Phi Centre. Explore space in new double feature KYMA – Power of Waves and Edge of Darkness at the Rio Tinto Alcan Planetarium. Immerse yourself in live music and audiovisual wonders at the SAT’s Satosphere surround-sound dome, featuring Audio Chandelier: Latitude by Dafna Naphtali, Modulations by Chikashi Miyama and Le Loup, Lifting and Myogram by Atau Tanaka and Lillevan.

Une publication partagée par Festival Musique de chambreMTL (@festivalmusiquedechambremtl) le 20 Juin 2016 à 7h05 PDT

Classical music

The Montréal Chamber Music Festival is not only a must for classical music lovers but for jazz fans too – among the concerts, hear The Dover Quartet perform the complete Beethoven String Quartet cycle and play with the Rolston String Quartet, and check out the June 3 TD Jazz Series show with saxophonist Rémi Bolduc. Pianist Alexandre Tharaud and Les Violons du Roy perform the world premiere of an Oscar Strasnoy commission, June 2 at Bourgie Hall. On June 4, hear the sublime sounds of the Orchestre Symphonique de Longueuil’s Concert du Printemps at Place des Arts, the Association des orchestres de jeunes de la Montérégie‘s year-end concert featuring Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 at the Maison Symphonique, and gala concert concert of the 2017 Prix d’Europe winners and invited guest pianist Xiaoyu Liu at Bourgie Hall. On June 6, the McGill Chamber Orchestra and choirs perform Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana and an oratorio by composer Larysa Kusmenko at Maison symphonique. And the Chœur classique de Montréal performs works of Bruckner to Rossini on June 6 at Maison symphonique.

youtube

More live music