#Boris Yakovlev

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#movies#polls#the ascent#the ascent 1977#the ascent movie#70s movies#larisa shepitko#boris plotnikov#vladimir gostyukhin#sergey yakovlev#lyudmila polyakova#viktoriya goldentul#have you seen this movie poll

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

VOSKHOZHDENIYE (Larisa Shepitko, 1977)

#voskhozhdeniye#the ascent#la ascension#larisa shepitko#boris plotnikov#vladimir gostyukhin#sergey yakovlev#lyudmila polyakova#viktoriya goldentul#anatoliy solonitsyn#mariya vinogradova#nikolai sektimenko#sergei kanishchev#film#cine

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ascent (Voskhozhdenie), Larisa Shepitko (1977)

#Larisa Shepitko#Yuri Klepikov#Boris Plotnikov#Vladimir Gostyukhin#Sergey Yakovlev#Lyudmila Polyakova#Viktoriya Goldentul#Anatoliy Solonitsyn#Mariya Vinogradova#Nikolai Sektimenko#Vladimir Chukhnov#Pavel Lebeshev#Alfred Schnittke#Valeriya Belova#1977#woman director

0 notes

Photo

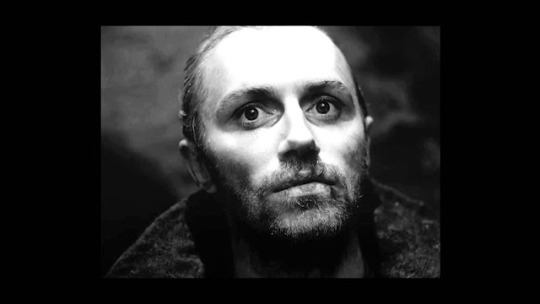

Boris Plotnikov in The Ascent (Larisa Shepitko, 1977)

Cast: Boris Plotnikov, Vladimir Gostyukhin, Sergey Yakovlev, Lyudmila Polyakova, Viktoriya Goldentul, Anatoliy Solonitsyn, Mariya Vinogradova, Nikolai Sektimenko. Screenplay: Yuri Klepikov, Larisa Shepitko, based on a novel by Vasiliy Bykov. Cinematography: Vladimir Chukhnov, Pavel Lebeshev. Production design: Yuriy Raksha. Film editing: Valeriya Belova. Music: Alfred Schnittke.

In some ways, The Ascent is the movie that the overpraised The Revenant (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2015) could and perhaps should have been: a rewarding but harrowing story, made without flashy technology, that asks as much of the viewer as it did of the actors and crew. Made under extreme winter weather conditions -- temperatures dropped to 40 degrees below zero -- in January 1974, it tells the story of two Russian partisans in World War II, Sotnikov (Boris Plotnikov) and Rybak (Vladimir Gostyukin), who go in search of food for their small group of fellow resistance fighters. When they're spotted by some German soldiers, Sotnikov kills one but is wounded in the leg. Through deep and blinding snow -- there's a memorable scene in which Rybak has to thaw a frozen Sotnikov with his own breath -- Rybak helps Sotnikov reach a cabin where a young woman, Demchikha (Lyudmila Polyakova), who lives alone there with her three children, helps them hide in the attic. But they're discovered by the Germans and taken to their headquarters in a Russian village, where the head of the collaborating Russian police, Portnov (Anatoliy Solonitsyn), interrogates them. Portnov tortures Sotnikov first, branding a star onto his chest, but Sotnikov stoically resists. When Rybak is brought in, he assumes that Sotnikov has already told everything, so he proceeds to give Portnov as much information as he has. To his dismay, he is sentenced to death along with Sotnikov, Demchikha, and two others. Sotnikov, gravely ill, confesses that he killed the German and maintains that he alone of the five deserves execution. Rybak, on the other hand, persuades Portnov that he could be of use as a collaborating policeman, and is spared execution. After the others are hanged, Rybak becomes the target of the contempt of the witnessing villagers, who mutter "Judas" at him. Torn by guilt, he tries to hang himself but fails, and at the end is left to his misery. This was the last film by Larisa Shepitko, who died in an automobile accident at the age of 41. She and her actors and crew underwent great hardships filming it, coming down with frostbite, but the film was almost suppressed by the Soviet authorities, who thought it was too much of a Christian parable. In fact, Shepitko had insisted on an actor who resembled traditional images of Christ, and Plotnikov's lean, ascetic appearance is heightened by the cinematography of Vladimir Chukhnov and Pavel Lebeshev, especially as Sotnikov stands with the noose around his neck at the film's climax. Fortunately, Shepitko and her husband, director Elem Klimov, were able to gain the support of former World War II partisans who testified to the veracity and emotional power of the film.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cast: Boris Plotnikov, Vladimir Gostyukhin, Sergey Yakovlev, Lyudmila Polyakova, Viktoriya Goldentul, Anatoliy Solonitsyn, Mariya Vinogradova, Nikolai Sektimenko. Screenplay: Yuri Klepikov, Larisa Shepitko, based on a novel by Vasiliy Bykov. Cinematography: Vladimir Chukhnov, Pavel Lebeshev. Production design: Yuriy Raksha. Film editing: Valeriya Belova. Music: Alfred Schnittke.

In some ways, The Ascent is the movie that the overpraised The Revenant (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2015) could and perhaps should have been: a rewarding but harrowing story, made without flashy technology, that asks as much of the viewer as it did of the actors and crew. Made under extreme winter weather conditions – temperatures dropped to 40 degrees below zero – in January 1974, it tells the story of two Russian partisans in World War II, Sotnikov (Boris Plotnikov) and Rybak (Vladimir Gostyukin), who go in search of food for their small group of fellow resistance fighters. When they’re spotted by some German soldiers, Sotnikov kills one but is wounded in the leg. Through deep and blinding snow – there’s a memorable scene in which Rybak has to thaw a frozen Sotnikov with his own breath – Rybak helps Sotnikov reach a cabin where a young woman, Demchikha (Lyudmila Polyakova), who lives alone there with her three children, helps them hide in the attic. But they’re discovered by the Germans and taken to their headquarters in a Russian village, where the head of the collaborating Russian police, Portnov (Anatoliy Solonitsyn), interrogates them. Portnov tortures Sotnikov first, branding a star onto his chest, but Sotnikov stoically resists. When Rybak is brought in, he assumes that Sotnikov has already told everything, so he proceeds to give Portnov as much information as he has. To his dismay, he is sentenced to death along with Sotnikov, Demchikha, and two others. Sotnikov, gravely ill, confesses that he killed the German and maintains that he alone of the five deserves execution. Rybak, on the other hand, persuades Portnov that he could be of use as a collaborating policeman, and is spared execution. After the others are hanged, Rybak becomes the target of the contempt of the witnessing villagers, who mutter “Judas” at him. Torn by guilt, he tries to hang himself but fails, and at the end is left to his misery. This was the last film by Larisa Shepitko, who died in an automobile accident at the age of 41. She and her actors and crew underwent great hardships filming it, coming down with frostbite, but the film was almost suppressed by the Soviet authorities, who thought it was too much of a Christian parable. In fact, Shepitko had insisted on an actor who resembled traditional images of Christ, and Plotnikov’s lean, ascetic appearance is heightened by the cinematography of Vladimir Chukhnov and Pavel Lebeshev, especially as Sotnikov stands with the noose around his neck at the film’s climax. Fortunately, Shepitko and her husband, director Elem Klimov, were able to gain the support of former World War II partisans who testified to the veracity and emotional power of the film.

The Ascent (1977) dir. Larisa Shepitko

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fact: Ukrainian politician Ivan Bakanov founded a liberal, centrist, pro-European political party in Ukraine and he named it "Servant of the People" after the political satire comedy TV show that was created by his close childhood friend President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, who is a politician, comedian and actor.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

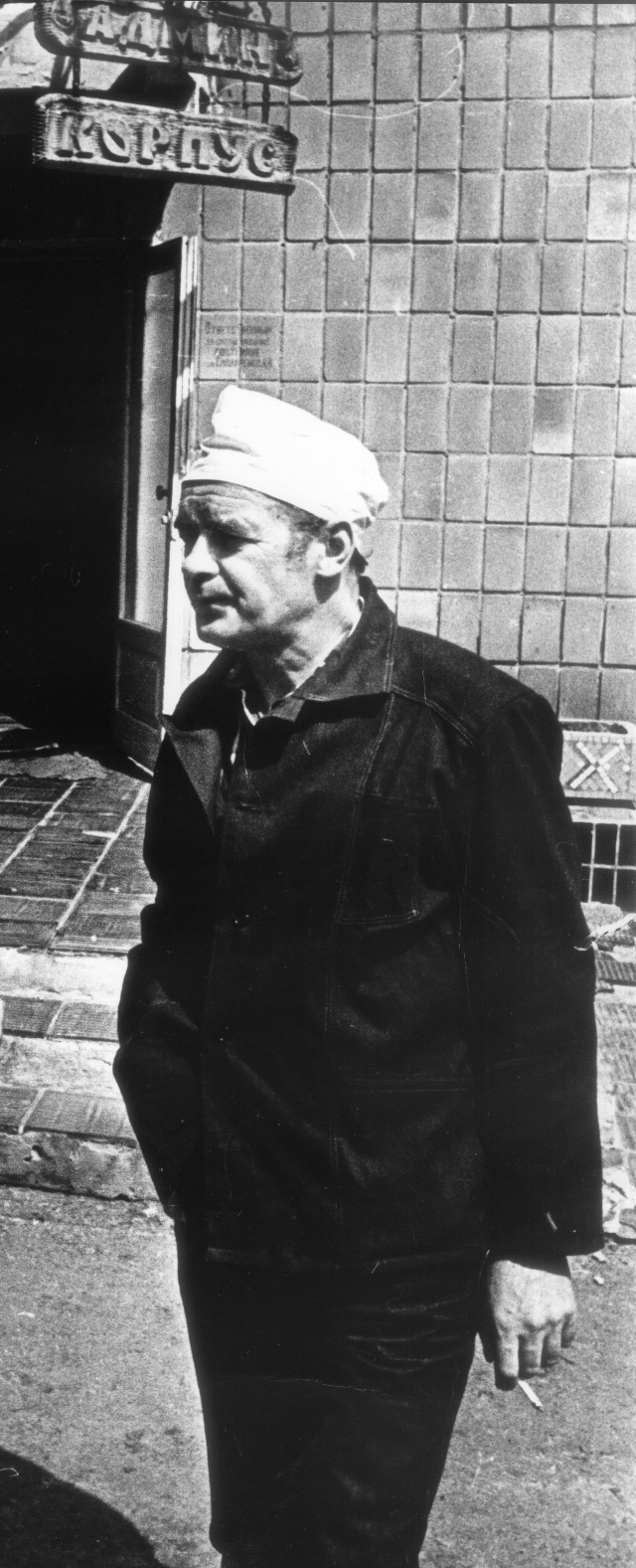

The Ascent (Larisa Shepitko, 1977)

#the ascent#Larisa Shepitko#shepitko#faces#Voskhozhdeniye#Voskhozhdenie#1977#black and white#russia#tears#sadness#winter#snow#cold#Boris Plotnikov#Vladimir Gostyukhin#Sergey Yakovlev

162 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vehicles being established, Transport adjusted - Boris Yakovlev, 1923

Russian, 1890-1972

Oil on wood, 100 x 140 cm.

72 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stalker (1979, Soviet Union)

Before one makes assumptions about this film’s title, the word “stalker” here refers to both the modern definition of the word and as a nickname (from Rudyard Kipling’s Stalky & Co.) for a character who smuggles people to a specific place. Andrei Tarkovsky’s ponderous, glacially-paced Stalker is among the greatest science-fiction movies – delving into questions of existentialism, rational choice, the danger of subconscious desire, faith, and the limits of human understanding. For Stalker, Tarkovsky has fully embraced minimalism – the film has 142 shots in its 163-minute runtime (the longest shots are uncut for over four minutes; the first spoken line appears after nine-and-a-half minutes) – making this movie inaccessible for those without grounding in or preparation for “slow cinema”. Tarkovsky’s final film produced solely in the Soviet Union is a deeply introspective work, bewildering in the best way, always astonishing.

In an unnamed country, the “Stalker” (Alexander Kaidanovsky) sneaks people into a place known as the Zone. The Zone, bereft of human residents, is heavily guarded along its outer perimeter, but the police and military dare not enter it. One day, the Stalker – shown to be living in poverty with children, and urged by his wife (Alisa Freindlich) not to leave – has agreed to guide the “Writer” (Antoly Solonitsyn) and the “Professor” (Nikolai Grinko) to the Zone.

The laws of physics and time do not apply in the Zone. And it is rumored that, somewhere in the Zone, there is a “Room” that grants the innermost wishes of anyone who steps foot inside. The reasons for a guide are many: the straightest path will result in certain death, any routes that once led to the Room become impassable because geography can change in a matter of minutes, and the Zone’s innumerable traps (mental and physical) can only be sensed and never seen. Depending on the viewer’s interpretation, the Zone and/or the Room may be sentient. The Stalker demands that the Writer and Professor obey his orders. During their journey, they talk about their motivations for finding the Room. The Writer has lost his artistic inspiration, the Professor reveals a nebulous desire for scientific analysis, and the Stalker – who says he does not wish to use the Room – does not reveal his intentions for guiding others through the Zone until the final minutes.

There are no villains or monsters, spectacular special effects, or anything that one might expect from a science-fiction film. This is Tarkovsky’s second science-fiction work after Solaris (1972) – a space story that analyzed the essence of love when it collides with questions of experienced reality (Solaris is a rejection of what Tarkovsky believed to be Western sci-fi’s coldness, as embodied in 2001: A Space Odyssey) – but Stalker is almost nothing like that earlier film. This film is only considered science-fiction because of the physical impossibilities of the Zone, not because of any space travel or futuristic technologies. In a development I had never considered for a science-fiction film, almost none of the questions that Stalker poses to the audience have anything to do with science or technology. While recognizing that the greatest science-fiction works examine the nature of humanity, all the science-fiction media I had consumed prior to seeing Stalker contained elements of how humanity intersects with science and technology. This relationship is almost, if not non-existent in Stalker, appearing only at the conclusion. Stalker is entirely interested in the hearts and minds of the three leads – what they are subjected to while traversing the Zone, however disturbing, does not influence the people they are and the final decisions they will make. The Room is only a projection of their humanity; it does not shape who they are. This is reinforced by the Stalker’s true introductory words upon entering the Zone:

Our moods, our thoughts, our emotions, our feelings can bring about change here. And we are in no condition to comprehend them... everything that happens here depends on us, not on the Zone.

Loosely adapted from Arkadi and Boris Strugatsky’s intricate novel Roadside Picnic (Arkadi and Boris were brothers and co-wrote the adapted screenplay), Tarkovsky simplified what he could for the big screen. This meant compositing multiple characters into the three primary characters for the film and trimming down several years of excursions into the Zone down to a single sojourn. Interference from the Soviet censors and the accidental destruction of the original negatives at the film processing laboratory necessitated the introduction of intertitles announcing a first and second part. Episodes of state interference frustrated Tarkovsky as well (the censors did not request as many changes in Stalker compared to previous Tarkovsky films, but they could not tolerate narrative ambiguity of any sort, even if they could not find any specific anti-communist themes), who was forced to shoot almost the entire film three separate times, and led to him looking towards the West for work. It is the third and last effort that is available to audiences today.

With all these compromises and production nightmares, Tarkovsky was given multiple opportunities to make the best possible film he could. Production difficulties also meant Alexander Knyazhinsky became principal cinematographer over Leonid Kalashnikov (1969′s The Red Tent), who himself replaced another cinematographer before that. One of Knyazhinsky’s decisions mirrors The Wizard of Oz (1939) – the opening scenes are shot in sepia and all scenes in the Zone are shot in color. In entering the Zone, Knyazhinsky and Tarkovsky allow for an extended tracking shot that allows a glimpse into the uncertainty of the three men journeying to the Room:

youtube

This tracking shot sets the pace and tone for the remainder of the film (notice how the clacks of the wheels become indistinguishable from Tarkovsky regular Eduard Artemyev’s film score – the Azerbaijani tar is feature heavily, and the above instance will not be the last time rhythmic sound effects become inseparable from the music). Shot in Estonia, Stalker utilizes a lush, but lifeless landscape littered with human reminders of what life was like before the Zone was created. Wind is everywhere, even if the sound mix does not pick up on it. The grasses sway, the tree leaves rustle, and a low-lying fog brushes across the flora. Also omnipresent is water – whether on the grasses due to recent rains, flooded buildings, walkways turned into creeks, or deafening waterfalls. The second half’s interior scenes were shot at deserted hydro power plants already filled with fetid liquid and marked by years of abandonment (conditions were so poor that sound designer Vladimir Sharun believes chemical poisoning from these locations hastened the deaths of three crew members, including Tarkovsky). Almost suggestive of a post-apocalyptic world with industrial and military scrap strewn across the Zone, the effect is a serene suspense. The suspense, beginning with the above tracking shot, is cumulative. With death or separation possible at any turn, a slow walk to check for traps and a trip through a waterlogged pipe inspire interminable dread.

Amid this dread, what begins as a partnership defined by obeying the Stalker’s orders transforms into a series of bursts of overwhelming philosophy, ad hominem, poetry recitations from the mouth and mind (the poems used are by Fyodor Tyutchev and Tarkovsky’s father, Arseny), and rare instances of humor. The Stalker speaks of the Zone as a holy, perhaps partially sentient place not to be mistreated. The way he describes his work is not only to serve as a guide, but to offer a sort of deliverance (for himself? Those who hire him? The Zone?). Among these three, their initial intentions are not as they first appear. Cynicism and dismissive attitudes towards the Zone and the Room belie personal weakness and tragic character flaws. A front of altruism is stripped away, revealing exhausting fear, material desperation, spiritual emptiness. Just as important as what the Stalker, Writer, and Professor say to each other is what they do not say to each other – in Stalker, silent shots of the character’s faces say just as much as the philosophical soliloquies. This is outstanding acting from Kaidanovsky, Solonitsyn, and Grinko.

The film’s primary themes revolve around the subconscious and one’s deepest desires. Those desires are usually never the ones we speak about when questioned by others. Instead, they are the ones that reveal our most sinister, selfish urges – stripped of social constructs, morals, restraint, and the judgment rendered by even those closest to us. Or perhaps excursions through the Zone (failed and otherwise) and entrances into the Room grant something far more minatory: latent revelations and wishes which may never be understood.

Perhaps it is that pure expression and dogged pursuit of individualism which scared the Soviet Union. Indeed, Soviet science-fiction literature has a history of critiquing authoritarianism, communist and capitalist systems, and cults of personality. The self-understanding achieved in Stalker is not common in fiction or real life – the realities are deeply unpleasant, but not approached cynically. The realization of these realities provokes different responses from the characters: anger and anguish. Stalker, through its framing and narrative escalations, is evocative of classic horror films – where a dense, foreboding atmosphere is the source of the horror. The horror in Stalker includes the desolate locations it features, but most importantly the purposes of the three men who seek the Room.

Released to heavy criticism in the Soviet Union, contemporary opinion has been kinder to Stalker. Western critics compare the Heart of Darkness-esque narrative to Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. But Stalker has much more to say than Coppola’s film, preferring to examine its subjects for who they are and what they bring to their newfound surroundings rather than the reverse. Rather than Joseph Conrad, Tarkovsky takes his literary cues not only from the Strugatsky brothers, but also those giants of Russian literature: Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Without spoiling too much, the Stalker’s enterprise seems informed by the title character in Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich (Ivan Ilyich is a dying man pondering the nature of his death and, increasingly, his life’s meaning) while his characterization resembles the title character in Dostoevsky’s The Idiot (whose epileptic bouts make people believe he is unintelligent, when he, despite being socially awkward, is anything but).

For first-time viewers, Stalker will baffle, enrage, and mystify. It should be viewed as cinematic poetry rather than a straight-laced narrative. This film conveys complicated ideas of desire and the changes resulting from desire that too few are receptive to. The few answers Stalker does provide are shrouded in its darkest corners, waiting to be discovered by those brave enough to present themselves and step forth. Do not expect anything flattering.

My rating: 10/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. Stalker is the one hundred and forty-sixth film I have rated a ten on imdb.

#Stalker#Andrei Tarkovsky#Alexander Kaidanovsky#Anatoli Solonitsyn#Nikolai Grinko#Alisa Freindlich#Sergei Yakovlev#Natasha Abramova#Arkadi Strugatsky#Boris Strugatsky#Alexander Knyazhinsky#Eduard Artemyev#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Voskhozhdeniye – Tırmanış

Voskhozhdeniye – Tırmanış

Savaş acıdır, kandır, vahşettir, insanın insana yapabileceği en büyük kötülüktür. Başkalarının yüksek çıkarları için diğer insanları öldürmenin adıdır. Savaş ile ilgili aklınıza gelebilecek her türden olumsuz nitelemeyi buraya ekleyebilirsiniz. Ama ya ülkeniz işgal edilmiş ise, size sadece işbirliği yaptığınız sürece bir hayat hakkı tanınıyor ise ne yaparsınız, geriye…

View On WordPress

#Anatoliy Solonitsyn#Aufstieg#Boris Plotnikov#Film eleştirileri#Larisa Shepitko#Lyudmila Polyakova#Mariya Vinogradova#Nikolai Sektimenko#Obelisk. Sotnikov#Süleyman Deveci#Sergey Yakovlev#The Ascent 1977#Vasiliy Bykov#Viktoriya Goldentul#Vladimir Gostyukhin#Voskhozhdeniye – Tırmanış#Yuri Klepikov

0 notes

Note

Valery's suicide! Did you remember little the details? He aged 10 years in 2 years and ughhh poor thing

https://archiveofourown.org/works/19349599/chapters/46352182

Theducks of the Moskva River had a stroke of luck that cold November morning. Theydiscovered a part of the stream that hadn’t been sealed the previous night bythe thick layer of frost, a round opening in the ice near the bank big enoughto accommodate a dozen of them. Every now and then they would plunge theirbeaks under the surface to grab silver slippery fish for breakfast. Soon, asthe pale autumn sun rose above the Moscow rooftops, the feathered refugees wereadditionally blessed with a shower of crumbs.

Similarto stray dogs chewing on leftovers the ducks didn’t question the origin oftheir unexpected meal. To them it was as if the grey-haired man in the ushankahat and the black overcoat, throwing crumbs from his sushki rings, had beenstanding there forever – not unlike the statues of Gorky Park; still, he wasdeprived of the otherworldly air of their bronze immortality. Something in hisposture, the resigned way he was slouching over the railing, betrayed he wasjust a man.

Theperson once known as the Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers rubbed hisgloved hands over the fence to get rid of the remaining crumbs. His worn blueeyes, fixed on the shore beneath him like nails on the floor, rose only at thesound of muffled footsteps on the snow. A scrawny balding figure with smallpiercing eyes approached him in his fur hat with a heavy wooden carrier inhand. Every now and then a soft mewling sound would come out of the holes onthe roof; as the silver-haired man peered at the box, a pair of green eyessparkled back at him through the wires.

“Volodya,”the former politician rose his hand, a twitch of friendly acknowledgmentblooming on lips that had forgotten how to smile.

“BorisEvdokimovich,” the figure greeted back leaving the carrier on the ground andopened his arms.

BorisEvdokimovich Shcherbina welcomed his old friend with a hug and several pats onthe back before pulling back to inspect him. “You look better than I ever was,”he said warmly.

The journalistfurrowed his brow, struck by Boris’ paleness. “How bad is it?”

“Gettingworse every day…” Boris replied with a dry cough as he pulled a handkerchiefout of his pocket.

VladimirGubarev’s eyes went dark. “I’m really sorry, I’m-”

“Sorryfor what?” Boris cut him off wiping his mouth. “It’s not your fault if I gotsick and you didn’t. Besides you were there only for a week. No one blames youfor that.”

“No,I’m sorry, it’s just that…” Gubarev muttered. “First Valery, now you. I’mrunning out of people to whine about Chernobyl with,” he shrugged in an almostcasual tone, “and my wife is so sick of hearing my war stories.”

Borischuckled discreetly knowing that if his laughter got too loud he would end uphaving yet another coughing fit. He sat heavily on the bench behind them and gesturedover the empty space beside him.

“Doyou think you were being followed?” he inquired.

“Idoubt it,” Gubarev reassured him sitting down. “On a cold morning like this?After so many months? It would surprise me if they remembered our names at all.Besides Valery’s dead. Nobody cares anymore.”

“You’reright…” Boris nodded, his empty eyes chasing a black-headed gull soaring overthe ice. “Nobody cares anymore…”

Heunfolded the used handkerchief in his palm and stared numbly at the ominouscrimson stains. The silence between them was so thick that for a moment Borisforgot he was the one who had called Vladimir Gubarev, the science editor ofPravda, to meet under the cold and unsuspecting Moscow sky. Away from bugs,away from curious onlookers, away from spies.

Thatmoment he thought he might as well be dead, forgotten, lying at the bottom ofthe frozen river, waiting for his body to be discovered days after his demise.

Just like Valery.

Heblinked away the painful thought and forced himself to smile. “What’s hername?” he bended over the wooden box as he slipped the tip of his fingerthrough the wires.

“Inga,”Gubarev smiled watching the tabby feline pawing at Boris’ leather glove. “Hismother’s name. He never had a daughter so…”

Borisrealized his face had instantly morphed into a dreadful mask as the journalistfroze before finishing his sentence. It wasn’t just the paleness and the blackcircles under his eyes, the constant reminders of his Chernobyl heart. It musthave been something crueler, something boiling in his chest, squirming underthe surface of his fragile calmness, threatening to explode.

“Inever-” he stuttered blinking at the cold autumn air. He sat back on his seat.“I never got the chance to ask him about his… about his fa- about his… f-family, oh God…”

Hecovered his eyes and dug his nails deep into his wrinkled forehead.

“Boris…”Gubarev choked giving his shoulder a feeble squeeze.

Beadsof tears formed tiny icicles on Boris’ cheeks and all of a sudden he was beingsucked into a hole of nothingness. The sickness hadn’t managed to break him.But this…

Thiswas worse.

“Therewas nothing you could do,” Gubarev insisted. “They wouldn’t let you. It’s notyour fault.”

“Ishould have… I should have taken my chances,” Boris shook his head, his voicetrembling from the cold and despair. “I should have visited him. Just once.What would they do? Kill me? I’m already dead. He was alreadydead. They made sure of that. Their negligence and stinginess and their prideand…”

Gubarevdrew back his hand and shoved his palms into the pockets of his long coat,looking for something. He turned to gaze at Boris but the former politician wasunable to return the look. Instead he took a deep shaky breath and rested hiselbows on his knees. A broken old man.

“Iwas asking everyone I knew about him,” Boris confessed, his voice raspy anddark with guilt. “Trying to catch any news I could, on his welfare, hiscondition. How he was getting along. I can’t imagine the bitterness he feltfinding out he was the only member of his team at Chernobyl who was not named ahero of socialist labor. Imagine how humiliated he felt, how betrayed.”

“Theygave him a watch instead of a medal, can you believe it?” Gubarev scoffed andthe cold air turned his breath into steam. “It would have been less painful hadthey stripped and beaten him. He was excluded by his own people from a seat onthe council of the Kurchatov Institute. Do you know what they said, Boris?” hespat hatefully. “Do you? ‘We will not be supervised by a boy.’”

Boristurned to glare at him as if he had those prestigious scientists right in frontof him. Within his reach. Within his murderous grasp.

Gubarevclosed his fist against his trembling lips as if to stop himself from cursing.“I wanted to punch them in the face, Boris, I swear to God. I wanted to tellthem ‘Legasov never left Chernobyl but I didn’t see any of you there.Where were you when he was putting his life at risk? Where the fuck wereyou?’”

Borisrested his forehead on his entwined fingers. His bent pleading posture could beeasily mistaken for a man in prayer had religion not been uprooted in hischildhood, when the bud was still young. “God” was nothing more than a mannerof speech to born and bred atheists like him. God didn’t exist. Not when peoplelike Valery were punished for the good they did. Not when the best of humanitywithered and died while parasites, bootlickers and backstabbers roamed theearth.

There was no“God”. How could he possibly exist.

“AllI wanted was hear his voice…” he murmured taking a deep laboured breath, hiseyes glued on the ground. “I would go to public phones, each time on adifferent street, and call him. Strangely enough the KGB never forced him tochange his number – that’s how arrogant they were, how confident that I wouldnever reach out to him.”

“Didyou talk?”

Borischuckled, his head hanging over his clenched knuckles. “No,” he said firmly.“Of course not. I knew his phone was tapped. I knew they’d make his life aliving hell if they heard my voice. It’s not like I cared about my own life.But he did. And I knew they’d tell him if somethinghappened to me.” He tipped his head just enough to watch the seagull take adive. “I-I wanted to spare him the pain, Volodya. They’d mail him my head in abox if they could. He had no reason to suffer any more than he already did.”

Whenthe journalist considered his friend’s tired face there were no traces oftears, no tiny shards of ice on his cheeks anymore. Just a steely blue starecutting through the cold November air like a dagger.

“Iwould call him just to be able to listen to him saying ‘Hello’, you know?”Boris continued, the words falling from his mouth like dead December leaves.“His voice, that’s all I needed…” He closed his eyes. “Just one word, one wordwas enough. Of course I would never answer but he knew it was me, I could tellfrom the hitching of his breath. We would share the silence, the long pausesbetween unspoken words. And that was enough. Sometimes I swear I could almosthear his silent sobs, his shaky breathing – but I knew he was alright, and heknew I was alive. It was enough, Volodya, God knows it was enough…”

Withshaky hands Gubarev drew a pack of cigarettes out of his pocket, put one in hismouth and offered Boris the rest. Boris refused with a weary wave. Thejournalist struck his lighter and curved his fingers around the flame takingsharp inhales.

“Sohe never talked?” he demanded squeezing his lips around the cigarette. “Henever said anything? To you?”

Boristurned to face him, his eyes lit with surprise.

Did Vladimir know?

Afterall, among those who had been at Chernobyl he was the only one who was allowedto talk to Valery after the trial.

He must know everything.

VladimirGubarev was a brave persistent soul. He had convinced Yakovlev, Gorbachev’s ownadviser, to let journalists witness the scene. He had called him every dayuntil Yakovlev authorized a group of journalists to go to Chernobyl, includingVladimir.

So, did heknow?

Better leave that questioned unanswered,Boris pondered.

“No…”he said eventually in a broken voice that was doing nothing to conceal histurmoil. “He never spoke. Not one word.”

A lie.

Gubarevtook a few puffs from his smoke before Boris could gather the courage to askhim the burning question that had been tormenting him all those months sinceValery died.

“Whendid you last speak to him?”

Gubarevtook a long pause biting his lip as he dug into the snow with the tip of hisboot. “The day before he died. I paid him one last visit but I didn’t know. Icouldn’t have guessed what he was about to do.”

“Whatwas the last thing he told you?”

Thejournalist regarded Boris with a pained expression. “’Takecare of Inga.’ He swallowed hard. “I said ‘Why? Are you afraidfor your life? Are they threatening you?’ His response was that he was sick,that he didn’t have long to live. I couldn’t possibly imagine that he wouldtake his own life only hours after I left him. Had I known I would have neverleft, Boris, I-”

Boristurned to face the river pursing his stiff lips. This time he was determined tonot let tears make him look like a helpless schoolboy.

“It’salright,” he whispered, “he was bound to do it. He chose the day to do it.Nothing you could have done about it.”

Gubarevnodded slowly letting out the smoke in big puffs that formed a thick mistaround his head. The sun was starting to make the frosty atmosphere bearable,encouraging a few scattered people in beanies and mittens to take a walk alongthe waterfront.

“There’sone thing I never asked you,” Boris broke the silence. “How you got Valery’stapes. I thought they would have confiscated them along with anything ofimportance found in his apartment.”

“Ohthey did,” Gubarev smirked, the first genuine smile since they started talkingabout Legasov. “The committee members took them as soon as they got to hisapartment. But I knew of their existence, Valery had told me. I had encouragedhim to keep a record of what had happened at Chernobyl. He wanted to write itall down but he was sick, he didn’t have the time… So he recorded everything.”

Gubarevsquished the butt on the bench and drew another smoke from the pack. His handhovered idly near his mouth with the unlit cigarette sitting still between hisfingers, as if, like Boris, it was anticipating the conclusion of the storywith bated breath.

“At Valery’s funeral I approachedLigachev, the secretary of the central committee, and told him to give me thetapes or I would go to the Politburo,” Gubarev bragged. “I said ‘The tapesare not meant for you, they’re not meant for Shcherbina. They’re meant forme’. And you know it worked, that same evening they brought the tapes tomy office! They even had an inscription that left no room for doubt – ‘VolodyaGubarev’.” He paused, knitting his brow at the memory. “After twodays I printed a huge piece in Pravda. Those fuckers did their best to erasehim from history books. Rip off his pages, throw them into the fire. But therewas nothing they could do about the tapes. The tapes are mine.”

Boristhrew him a side glance. His lips parted unsure of how to continue, unsure ofhow to utter the next sentence without making him sound like a complete selfishidiot, unsure of how to accept the bitter truth that hid in Vladimir’s words.

“Didhe…” he began as a shade of pink took over the sickly paleness of his cheeks.“Did he leave anything behind?… For me?”

Gubarevgave an amused chuckle and straightened the fur hat on his head as if trying tohide his laughter. He rested his elbows on his knees and turned to Boris whoseblushing did nothing to hide his embarrassment.

Thejournalist’s grin broadened. “Yeah. He did. There must have been a tape foryou, he hinted at it in one of his recordings. He didn’t want the KGB to knowof course. But he said he had hidden something for you in the kitchen,‘B’s gift’ he called it. And oh, you’re going to need this too.”

Heshoved his hand into his pocket and brought out a key. “From his apartment.”

Boris’eyes widened at the unexpected present. “His apartment? How could you have akey? I thought the police took it all.”

“Wellthey didn’t know I had one, did they?” Gubarev’s lip twisted in a triumphantgrin. “He gave it to me the night before his death. He wanted me to have thosetapes, Boris, and he wanted me to save Inga. I never got there on time ofcourse, I never called him until it was too late. When I found out, the policehad taken everything. Lucky for me, Inga had already been rescued by theneighbours.”

“Howso?”

“Shewas the one who notified everyone about his death. Valery had left her severalbowls of food but when she finished it all she climbed up the kitchen windowoverlooking the freight lift and howled her lungs out. Mr Sokolov next doorbroke the glass and took her in, and that’s how they found out Valery was dead.Then they called the police.”

Gubarevshrugged. “It’s not like the KGB would care about a broken window, or Legasov’smissing cat for that matter. Mr Sokolov knew who I was so he trusted me withInga when I arrived looking for the tapes.”

Hehanded Boris the key. “Valery wanted me to have the tapes but I can’t keep Ingaany longer, the wife…” he winced reluctantly. “She wants a dog,” he mutteredthrough his teeth.

Helifted the carrier and placed it in the space between them. “She’s yours. I’msure that’s what he wanted, she’s his kid, you see. Just… take care of her.Alright?”

Borisgazed numbly at the glistening piece of nickel in his palm before shifting hiseyes at the wooden carrier. She must have been freezing in that box all this time,he reckoned with a hint of regret.

He took a deep breath; he never thought he’d finda reason again to wake up in the morning. One last treasureto find and someone to take care of.

Areason to get on his feet and back into motion. Back to life, for as long as hehad.

Somethingdawned in him, something warming him from the inside, more radiant than athousand suns.

Heclenched the key against his chest giving Vladimir a ghost of a smile as hetook the wooden box, feeling its weight against his thigh.

Thewarmth was still there, pulsing in his heart like the last rays of sunshine ona glorious sunset. He knew what it was now and he embraced it like a long-lostfriend.

Itwas hope.

#chernobyl#chernobyl fanfiction#hbo#valery legasov#boris shcherbina#vladimir gubarev#legasov's tapes#inga#cat#RPF#real person fiction#moscow#moskva river#ducks#a single bullet#ao3#mine#elenatria#the tapes#new chapter!!!

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

All about Boris Yakovlev : height, biography, quotes

How tall is Boris Yakovlev

See at http://www.heightcelebs.com/2017/03/boris-yakovlev/

for Boris Yakovlev Height

Boris Yakovlev's height is 5ft 8in (1.73 m)Boris Aleksandrovich Yakovlev (Russian: Борис Александрович Яковлев; Ukrainian: Борис Олександрович Яковлев; 16 July 1945 – 23 June 2014) was a Soviet Ukrainian race walker. Born: 16 July, 1945Birthplace: Petrovsk, Saratov Oblast, Russia Died: 23 June, 2...

0 notes

Photo

1943 Yakovlev Yak-1b Boris Yeremin - Andrey Zhirnov - Zvezda

theoldarmor: The title says: "To the pilot of the Stalingrad front guards major Yeremin from farmer of the collective farm "Stakhanovets" comrade Golovatov"

http://albumwar2.com/world-war-2-yak-1b-fighter-of-boris-yeremin-soviet-air-ace/

34 notes

·

View notes

Link

There are two parallel universes operating in Ukraine: The one presented from 2014 to 2021, and the one rewritten like a Hollywood movie with CIA input/guidance. This grandly orchestrated McKinsey & Co restyled operetta would also apply to Saint Zelensky, his wife, and his friends who all became cabinet members upon his election. Fun Fact! In 2018- 2019 Zelensky’s ‘sprawling network’ of offshore accounts became the subject of the Pandora Paper Scaper scamerati. Later the Panama Paper Caper also named Zelensky. All accounts were co-owned by Zelensky with four members of his Sitcom crew and friends; Shefir, Borys, Yakovlev and … Continue reading →

0 notes

Text

CINE EXPRESS: “Voskhozhdeniye (La ascensión)”

CINE EXPRESS: “Voskhozhdeniye (La ascensión)”

Helena Garrote Carmena Año: 1977País: Unión Soviética (URSS)Dirección: Larisa ShepitkoActores: Boris Plotnikov, Vladimir Gustyukhin, Sergei Yakovlev, Lyudmila Polyakova, Viktoriya Goldentul. Anatoly Solonitsyn, Mariya Vinogradova, Nikolai Sektimenko.Género: Drama – Bélico – Película de culto. La directora elige La Segunda Guerra Mundial para poner el foco en el comportamiento humano y…

View On WordPress

0 notes