#Black American Literature

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Can’t nothing heal without pain.

#Beloved#Toni Morrison#literature#Lit#bookblr#bookblog#American literature#Black American literature#quote#quotes#black gothic#magical realism#english#southern gothic#gothic

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

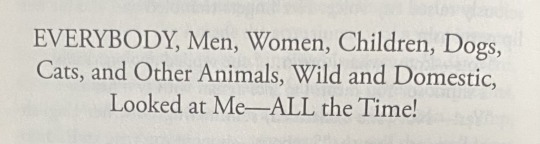

Chapter title and entirety of Chapter 15 from Vincent O. Carter’s The Bern Book

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

🌟 Celebrating Nikki Giovanni! 🌟

Celebrating the powerful words of Nikki Giovanni, one of the key figures of the Black Arts Movement. In this poem "Woman," Giovanni explores themes of identity, self-empowerment, independence, and unfulfilled relationships. The poem captures a woman seeking to define herself on her own terms and yearning for mutual understanding and support in her relationship. However, when the man in her life fails to reciprocate, she ultimately embraces her individuality and self-reliance. Her evocative language and poignant insights make this poem a must-read for poetry lovers and fans of her work.

#nikki giovanni#woman#poem#black arts movement#poetry reading#spoken word#black american literature#feminist poetry#social justice#identity#empowerment

0 notes

Text

#historical fantasy#black american literature#black american author#asian american author#asian american literature#latine author#latine literature

0 notes

Text

#black tumblr#black literature#black excellence#black history#black community#black history is american history#breakdancing#black pride#black people#blackexcellence365

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

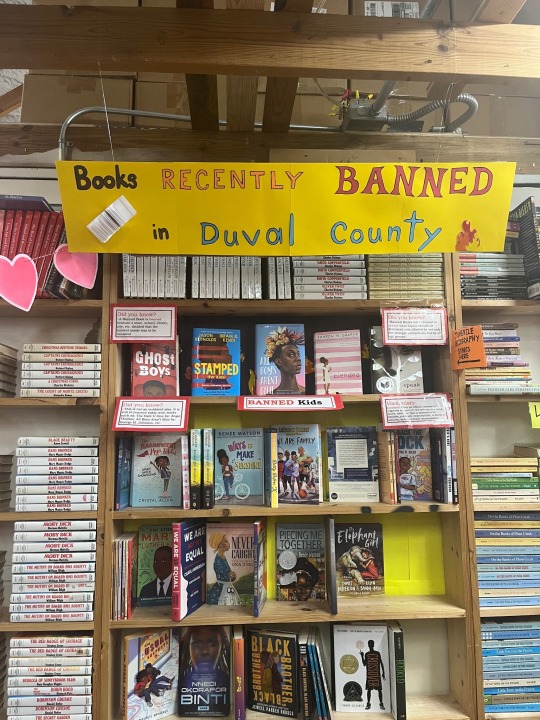

#Books#florida#woc#native american#poc#gop#libraries#librarians#black literature#Mlk#rosa parks#latinx#latinos#schools#abuela#mlk jr#ron desantis 2024

29K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ta-Nehisi Coates, from Between the World and Me

Text ID: The pursuit of knowing was freedom to me, the right to declare your own curiosities and follow them through all manner of books. I was made for the library, not the classroom. The classroom was a jail of other people's interests. The library was open, unending, free.

#ta-nehisi coates#ta nehisi coates#between the world and me#quote#autobiography#biography#memoir#nonfiction#nonfiction literature#black literature#american literature#lit#miscellanea

649 notes

·

View notes

Text

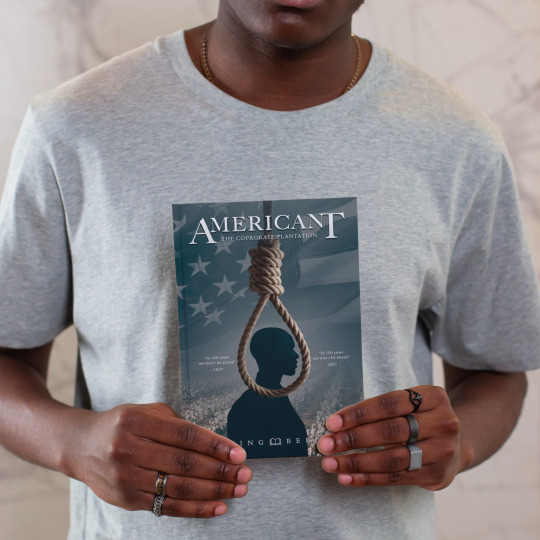

American't: The Corporate Plantation by King Bell

King Bell’s powerful book, “American’t,” delves deep into the challenges of six Black men in The Corporate Plantation. Through their eyes, you will gain a unique perspective on the struggles of being Black in a country that seems to be against you. This novel will make you question your American citizenship in a way that is both funny and moving.

Learn about what it’s like to be Black in America. Grab a copy at www.americant.theauthorkingbell.com.

#King Bell#American't#ReadersMagnet#selfpublishing#Black Experience#Black American Literature#African-American Literature

0 notes

Text

Call it. No. I ain't gonna call it

#no country for old men#ncfom#preachers daughter aesthetic#the right person will stay#manic pixie dream girl#sylvia plath#preachers daughter#literature#lana del rey aesthetic#this is what makes us girls#ultraviolence#autumn#black swan#coquette aesthetic#catholiscism#alana champion#coquette girl#cinnamon girl#americana coquette#coquette americana#coquette#susanna kaysen#the virgin suicides#girl interrupted syndrome#americana aesthetic#western gothic#ethel cain#female hysteria#american gothic#girlhood

405 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I remember an incident from my own childhood, when a very close friend of mine and I, we were walking down the street. We were discussing whether God existed. And she said he did not. And I said he did. But then she said she had proof. She said, ‘I had been praying for two years for blue eyes, and he never gave me any.’ So, I just remember turning around and looking at her. She was very, very Black. And she was very, very, very, very beautiful. How painful. Can you imagine that kind of pain? About that, about color? So, I wanted to say you know, this kind of racism hurts. This is not lynchings, and murders, and drownings. This is interior pain. So deep. For an 11 year-old girl to believe that if she only had some characteristic of the white world, she would be okay. [Black girls] surrendered completely to the master narrative. I mean the whole notion of what is ugliness, what is worthlessness. She got it from her family, she got it from school, she got it from the movies — she got it everywhere; it’s white male life. The master narrative is whatever ideological script that is being imposed by the people in authority on everybody else. The master fiction, history, it has a certain point of view. So, when these little girls see that the most prized gift that they can get at Christmastime is this little white doll, that’s the master narrative speaking: “This is beautiful. This is lovely, and you’re not it.”

Toni Morrison on what inspired her to write her first novel, The Bluest Eye.

#toni morrison#the bluest eye#1970#novel#writer#black writer#black literature#black girls#dark skinned black girls#misogynoir#anti blackness#black women#colorism#black children#african american#african american women#queen#quote#sbrown82

559 notes

·

View notes

Text

Florida has required public schools to teach African American history for 30 years. Yet, according to the Associated Press, many students receive lessons that are incomplete or inadequate.

In response to growing distrust in the state’s education system, community organizations, churches and cultural institutions are stepping in to fill the gaps.

In Delray Beach, Charlene Farrington leads Saturday morning classes at the Spady Cultural Heritage Museum to teach teenagers the history that schools often omit.“You need to know how it happened before so you can decide how you want it to happen again,” Farrington told her students.

Governor Ron DeSantis, a Republican, has spearheaded efforts to limit discussions of race, history and discrimination in classrooms. His administration has banned certain Advanced Placement African American Studies courses, citing alleged legal violations and historical inaccuracies.

Community-driven initiatives are gaining traction, with churches and advocacy groups taking the lead in educating students. Since launching its Black History toolkit last year, the nonprofit Faith in Florida has enlisted over 400 congregations to incorporate the resource into their programs.

Read more about this initiatives at ESSENCE.com.

#black history#blacklivesmatter#black lives matter#black people#racial injustice#black american history#black excellence#black pride#black liberation#black literature#black empowerment#black culture#africa

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me and you we got more yesterday than anybody. We need some kind of tomorrow.

#Beloved#Toni Morrison#literature#american literature#black american literature#magical realism#black gothic#gothic#southern gothic#bookblr#bookblog

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

❀ 𝐉𝐨𝐚𝐧 𝐃𝐢𝐝𝐢𝐨𝐧 ❀

#joan didion#american writer#writer#american author#journalism#1960s#60s#sixties#60s icons#photography#black and white photography#1970s#70s#seventies#new journalism#60s women#literature

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

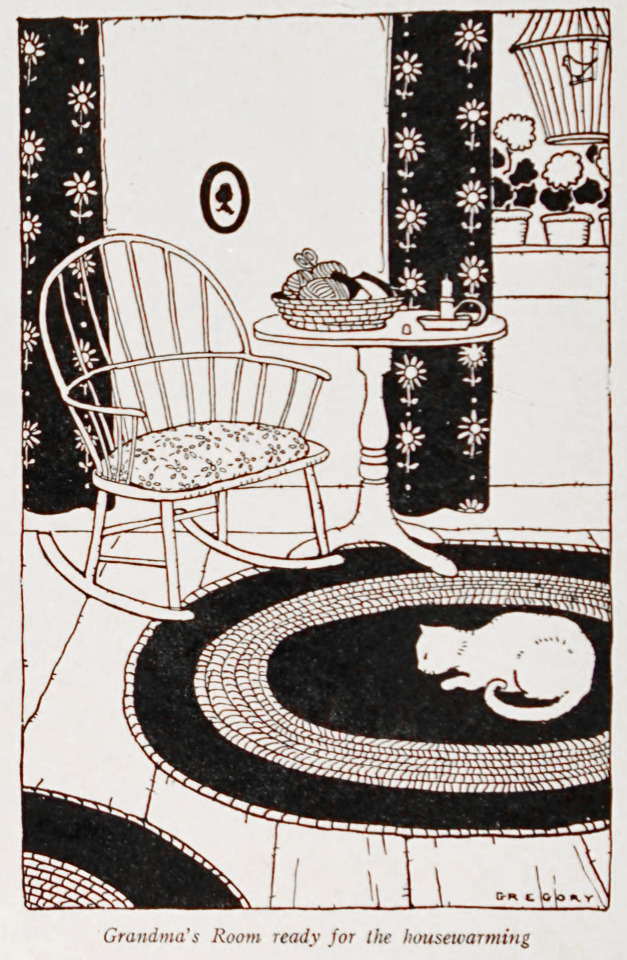

Dorothy Lake Gregory (1893-1975), ''Early Candlelight Stories'' by Stella C. Shetter, 1922 Source

#Dorothy Lake Gregory#american artists#Stella C. Shetter#vintage illustration#black & white illustration#vintage art#cats#children's books#children's literature

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

#black speculative fiction#black ya fantasy#black ya sci-fi#black author#black american author#black american literature

0 notes