#Birdiethings

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Hiii, I hope you're well :))) I want to complain about something if you don't mind. It saddens me that Andromeda by Sophocles and Euripides is lost because they expanded Andromeda's character. We would have been able to learn about her personality, as well as her relationship with her parents

But still one thing that is clear is that she did NOT want to be sacrificed, she had dreams/desires and wanted to live at all costs, even if people see that as selfish she has every right to want to live

But in several retellings they make her want to sacrifice herself for the good of her kingdom which is totally out of character, because supposedly they want to give her "a voice" but they only do it to make Perseus look bad since that is not even what Andromeda wanted

I remember reading an article where the author mentioned a Greek pottery dating back to the VI BC depicting Perseus confronting Cetus with stones that Andromeda Gave Him (I don't remember if I ever saw the pottery) and the author basically said that apparently the earliest versions of the story had Andromeda participating in the defeat of Cetus or helping Perseus in some way, which I think is a much better way to do in retellings if they really want her to have more involvement in her own myth

—🪷

Hey! Thanks for the question, I'm doing fine and I hope it's the same for you. Also, sorry for taking so long! I was trying to find some article/book that commented on this vase you mentioned because I found interesting! I also found other things, so this post will probably be long because I feel they’re of interest to the seemingly eternal debate surrounding the Andromeda agency (whether in relation to sacrifice or marriage).

I don't usually read retellings or watch adaptations, so I don't know what the adaptations of the Andromeda myth are like. So, I won't focus on that and will think more about the aspect of what we can learn about Andromeda from the myths. I think that even with Euripides and Sophocles gone, we have enough hints about Andromeda's psyche. So, this post will be more me arguing in favor of the following things:

1) Andromeda wasn't a character adept at self-sacrifice;

2) Perseus saved Andromeda, if not out of love, at least out of passion;

3) At some point, the feeling was reciprocal;

4) The marriage wasn't disadvantageous to Andromeda.

Details:

I usually include the secondary source details (author, page, title) at the time I cite them, but in this case I'll try another organization. As for primary sources, I obviously didn’t include all of the Greco-Roman primary sources for Andromeda. Also, Sophocles' play is notably absent because, unlike Euripides' play, the surviving fragments do not give us enough insight into the character's psyche.

Sometimes the post will tend to other characters, but that's because I feel they will be useful examples of my opinion (in this case, sacrificial characters besides Andromeda). Note that, since the focus is STILL Andromeda, I won't go into too much depth on them and will use them in a more simplistic way. So if someone thinks "well, but the context of this character is much more complex and..." yeah, but the character isn’t the focus. It's just an example.

And as always, a typical warning in case someone who doesn't follow me reads this post... it’s a hobby post. My posts are huge, yes, but they're all purely for entertainment. This is an opinion post. Lotus Anon wanted to talk to me about the subject, I'm just "talking" so to speak.

ANDROMEDA: WILLING OR UNWILLING SACRIFICIAL MAIDEN?

When I received this ask, I at one point wondered what the oldest literary source of Andromeda had to say about her since you mentioned the article theorizing about oldest version with a visual source. When I was trying to remember, I got the impression that there was an apparent Andromeda absence in ancient literary sources — absence not in the sense of necessarily not existing at the time, but of not being mentioned — even when Perseus, her husband, is mentioned. The oldest literary source of Perseus is The Iliad, since the Homeric text presents an episode in Book 14 known as the seduction of Zeus by Hera, who intended to distract him (sexually) and put him to sleep with the help of the god Hypnos in order to give the Achaeans an advantage in the Trojan War. At one point, Zeus compares Hera to the other women who attracted him, claiming that none of them attracted him more than Hera was attracting him at that moment. Among them, he cites Danae as saying “nor when I desired Danaë of the shapely ankles, daughter of Akrisios, who bore Perseus, conspicuous among all men” (14.319–320, trans. Caroline Alexander). Also, “Sthenelos, son of Perseus” is identified when describing Hera’s intervention in the birth of Heracles (19.97–144). The Iliad, however, doesn’t give the heroic Perseus who saves his mother and future wife, but rather gives his genealogy — maternal grandfather Acrisius, mother Danae, father Zeus, son Sthenelos. Consequently, Andromeda isn’t actually mentioned, although it could perhaps be argued that she is implied since Sthenelos in later sources is explicitly the son of Andromeda. A text usually attributed to Hesiod had already demonstrated the heroic aspect of the Perseus myth by describing him dealing with the Gorgon sisters in the Shield of Heracles (216–236, trans. H.G. Evelyn-White), although Andromeda was still notably absent since her sacrifice wasn’t the theme, but rather the killing of the Gorgons. In later sources it was specified that Perseus was meant to protect his mother, although the Shield of Heracles doesn’t make this explicit, so perhaps it could be argued that Perseus as protector of his family was already implied.

Then I noticed that, although Andromeda is apparently absent in these older texts, the idea of a virgin being sacrificed isn’t completely absent. In the Homeric texts, there really isn't much to be said. Polyxena is never acknowledged as existing, and consequently her sacrifice isn’t a theme — something that Pausanias, in Description of Greece 1.22.6, seems to think was intentional on the poet's part. Iphigenia is also never directly mentioned, and her existence in the Homeric tradition is a matter of debate, with some arguing that a speech by Agamemnon (1.101-120) indicates that Calchas had previously asked him to sacrifice Iphigenia, others arguing that Iphinassa is Iphigenia and therefore Iphigenia is alive (9.144-145), and finally, there is further debate as to Clytemnestra's motivation for murdering Agamemnon in The Odyssey — Cassandra is certainly a catalyst, judging by Book 11, but in the Homeric tradition is Iphigenia supposed to be a catalyst as well? For all intents and purposes, however, Iphigenia is still not explicitly mentioned in any of these narratives, regardless of the debates. But, according to Pausanias, the Hesiodic Catalogue of Women apparently already alluded to the sacrifice of Iphigenia although he apparently went with the version in which she isn’t literally killed (frag 71) and the lost poems of the Epic Cycle apparently also already acknowledged the maidens sacrifices — Proclus' summaries of The Cypria and The Sack of Ilium (considered frag 1 of each epic) indicate that in the first epic there was the sacrifice of Iphigenia and in the second there was the sacrifice of Polyxena. Thus, even if the myth of Andromeda isn’t explicit in the sources, the trope of the sacrificed virgin already was.

Ironically, it’s as if Andromeda's essence is here, but Andromeda herself isn’t. Perseus, her husband, and Sthenelos, her son, exist, but she isn’t mentioned. The virgins are being sacrificed, but we don’t hear of Andromeda's sacrifice. Looking for any signal of her in literary sources, I felt as if I were getting hints of Andromeda in Archaic Greece, but not the real thing. Or at least, that is what I thought when I checked the Evelyn-Hugo edition of the Catalogue of Women in the Theoi... I later found the detail that fragment 135 MW is also listed as being in the Hesiodic Catalogue of Women and contains a reference to Andromeda:

... Abas; and he be[got a son,] Akrisios.... [Pe]rseus, whom... [in a che]st into the sea... [b]rought up for Zeus... gold... dear Perseus... [and from him and] Andromeda [daughter of] Kepheus [were born Alkaios] and [S]thenelos and the force [of Elektryon]... by the cattle... for [the Te]leboai... [A]mphitryon

Translation by Silvio Curtis, retired from gantzmythsources. Note that the parts “[]” are reconstructions and “...” are lacunas.

So, a literary confirmation of the existence of Andromeda in Archaic Greece! Although her myth hasn’t been preserved in this part, the mention of her marriage to Perseus seems to be a nod to her sacrifice, rescue and consequent marriage. Considering that the edition of Theoi is from 1914, I imagine that this fragment doesn’t appear in it because it was added to the fragments of the Catalogue of Women in some later year of the academic research that tries to reconstruct it. I saw that West (1985) had already commented on this fragment, although he was particularly interested in the geographical and genealogical aspects and, therefore, it isn’t useful to me because I’m trying to get clues about the psychological aspect of Andromeda. I saw that many also argued in favor of the myth of Andromeda having foreign influences, but the uncertainties of the more complex parts of these theories don’t give me many clues about what this means for the character's psychology and says more about the narrative and visual elements of the myth. In short, all this only attests to Andromeda's existence, but gives us nothing about her thoughts.

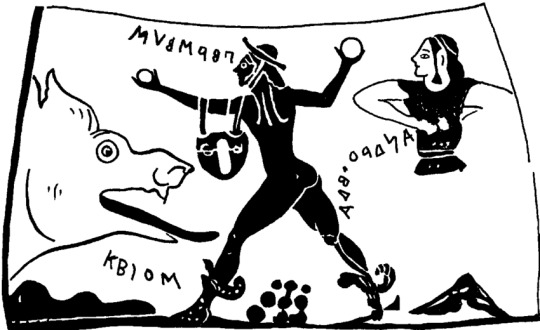

Ogden (2008, p. 67–68) has commented on the earliest visual source attesting to Andromeda. It’s the Corinthian black-figure amphora of ca. 575–50 BC, which places it as a 6th century BC source. It’s possible to identify it because the inscriptions of the characters have been preserved, indicating the names Cetus, Perseus, and Andromeda. However, Perseus' usual weapons — the head of Medusa or a sword — are notably absent, and he actually appears to be throwing stones at Cetus. I imagine this is the pottery you were talking about, nonnie! It really does exist!

Perseus rescuing Andromeda from the monster at Joppa. Late Corinthian amphora, second quarter of the sixth century BC. Berlin F1652. Drawing by author. See here.

This pottery had already been mentioned by Philips (1968, p. 1), who interpreted Andromeda's drawing as an indication of her excitement:

Perseus in his role as savior of Andromeda is known as early as the first half of the sixth century B.c. on a late Corinthian amphora now in Berlin (pl. I, fig. I). Here, with neither the Gorgon's head nor his harpe, he seems to throw stones at a long-tongued monster while Andromeda gesticulates in excitement. Each character is named.

If we follow this interpretation, it would make one of the earliest sources of Andromeda an indication of her happiness at being rescued, which could imply her uncooperativeness with the sacrifice. Looking at the figure, it’s interesting that although Andromeda is behind Perseus, she appears to be holding more rocks. This could indeed imply that Andromeda is actively helping to defeat Cetus, which again would indicate her opposition to being sacrificed and her willingness to receive help. The detail that one of the earliest sources of Andromeda depicts her as opposing her sacrifice is significant, as there is nothing to prevent other lost contemporary sources from having followed the same logic — in fact, it’s much more evident from the later surviving sources.

As for Andromeda's cooperativeness in her sacrifice, a emphasized element in her myth is the way in which Andromeda was intended to be sacrificed. Several texts, both Greek and Roman, described how she was chained, for example:

Euripides’ Andromeda — “Do you see? Not in dancing choruses nor among the girls of my age do I stand holding my voter’ funnel, but entangled in close bounds I am presented as a food for the sea monster Glaucetes, with a paean not for my wedding but for my binding. Bewail me, women, for I have suffered pitiful plight—O suffering, suffering man that I am!—and other lawless afflictions from my kin, though I am implored the man, as light a lament filled with tears for my death”, frag 122. Loeb edition.

Ovid’s Metamorphosis — “They bound her fettered arms fast to the rock”, Book 4. Translation by Brookes More.

Ovid’s Ars Amatoria — “What was less hoped for by Andromeda, in chains”, Book 3. Translation by A.S. Kline.

Lucian’s Dialogue of the Sea — “Andromeda, fettered to a jutting rock”. Translation by H.W. and F.G. Flower.

Pliny the Elder’s Natural History — “and Joppe, a city of the Phoenicians, which existed, it is said, before the deluge of the earth. It is situate on the slope of a hill, and in front of it lies a rock, upon which they point out the vestiges of the chains by which Andromeda was bound”, 5.69. Translation by Henry T. Riley.

Philostrathus, Imagines — “while Eros frees Andromeda from her bonds”, 1.29. Translation by Arthur Fairbanks.

Pseudo-Apollodorus’ Library — “But Ammon having predicted deliverance from the calamity if Cassiepea's daughter Andromeda were exposed as a prey to the monster, Cepheus was compelled by the Ethiopians to do it, and he bound his daughter to a rock”, 2.4.3. Translation by J.G. Frazer.

Antiphilus in Greek Anthology — “she who is chained to the rock is Andromeda”, 147. Translation by W.R. Paton.

Solinus’ Polyhistor — “This town displays a rock which to this day retains traces of the chains used to bind Andromeda”, 34. Translation by Arwen Apps.

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca — “One made for Cepheus's daughter, and with starry fingers twisting a ring as close as the other, enchained Andromeda, bound already, with a second bond aslant under her bands”, Book 1; “Again she awakened a new resentment, seeing the heap of Andromeda's broken chains beside the Erythraian sea, and that rock lying on the sand, Earthshaker's monstrous lump”, Book 31; “Perseus on the wing loosed the chains of Andromeda and offered the stone seamonster as a worthy bridal gift”, Book 47. Translation by W.H.D. Rouse.

And one has to wonder why Andromeda is chained in the sources in general when I can't think of this as a common sacrificial motif in Greco-Roman literature, but here I want to focus on the fact that she is still chained in the Euripidean version. Euripides certainly knows what to do when he wants to emphasize that a character who is a sacrificial victim has regained some agency, however small. If Aeschylus depicted Iphigenia crying and screaming and being bound in Agamemnon, Euripides depicted her walking freely to the altar. If visual representations of Polyxena depicted her being immobilized and carried away by the Achaeans, Euripides made it so that, by showing no resistance, such immobilization was unnecessary. This isn’t to say that Iphigenia or Polyxena wanted to die in Euripides’ version, but it does indicate something about the role resistance plays into their death. And even with Euripides having this tendency, his Andromeda remains chained rather than subverted as he did with Iphigenia and Polyxena. In the purpose of explaining what I want to explain, let’s do some comparison. These are examples that involve the need for someone to give up their life. Menoeceus and Alcestis weren’t literally sacrificed as were Iphigenia, Polyxena, Andromeda, and Maiden (Macaria), but I’m still including them.

In Alcestis, king Admetus (he was the king of Pherae) was given the opportunity to live beyond his destined life because of the favor of the god Apollo, but on the condition that someone else would have to willingly die in his place. Admetus couldn’t find anyone willing to do this for him, including his elderly parents, and so when Death came to collect his share of the bargain, his wife Alcestis volunteered to die in his place. Since the bargain required a voluntary sacrifice, Alcestis did so of her own will, even though Admetus didn’t wish her to die and lamented it greatly afterwards. Her act was praised as an act of love and is even cited as an example in Plato's Symposium (179b-208d). She was later rescued from Death by Heracles, who was a guest of Admetus.

In The Phoenician Women, the Thebans and Argives are in conflict because of the brothers Eteocles and Polynices, both of whom desire the crown and have also been cursed by their father Oedipus. At one point, the seer Tiresias informs the Theban king Creon that he must sacrifice his son Menoeceus to save Thebes from divine punishment imposed by the god Ares. Creon, however, actively resists the plan, even instructing Menoeceus to flee so that he may live. However, despite pretending to agree with his father, Menoeceus disobeys and willingly sacrifices himself, appeasing the divine wrath. This is considered a heroic act, as he willingly offered his life in exchange for the salvation of his people despite having the option of fleeing and being supported in doing so by Creon.

In Iphigenia in Aulis, Iphigenia initially shows resistance and fear at the idea of being sacrificed to the goddess Artemis, but eventually gives in and subverts her sacrifice from a tragedy to a form of immortality despite the active opposition of her mother Clytemnestra and the suggestion of her not-really-groom Achilles to save her. By showing no more resistance, Iphigenia, according to the Messenger who notifies Clytemnestra, also “dies” — she is, in fact, replaced by a deer — in the most dignified way possible considering the context. Her voluntary sacrifice seems to be equated with the sacrifice of a warrior to obtain kleos, making her in some ways an active heroine rather than a passive victim — although she is still a victim of the war. Iphigenia, despite having had a fear of death, eventually sees it as a source of pride.

In Hecuba, Polyxena, having no other choice, is conformed to be sacrificed and attempts to regain some agency by taking this as her way out of slavery despite the active opposition of her mother Hecuba. Because she doesn’t resist, regardless of how she feels, Polyxena isn’t forcibly dragged away or anything like that. Talthybius would later report to Hecuba that Polyxena supposedly died in the most dignified way possible, given the situation she was in. Polyxena is different from Iphigenia in that she isn’t seeking fame or any recognition of her sacrifice, but she is still emphasized as being dignified to the point that Talthybius makes a point of emphasizing that Polyxena managed to hide her body as she died in order to maintain modesty. Part of Polyxena's argument was precisely to be able to maintain as much dignity as possible, since this was and would be further stripped from her as a princess on the losing side and enslaved girl.

In The Heraclidae, Maiden has the chance to escape the sacrifice, but doesn’t do so, going so far as to refuse a lottery (which maybe would have given a maiden other than her and thus prevented her from being killed) and offers to be sacrificed, thinking that this will help her city win the conflict since the oracle informed them that they would only win if a maiden was sacrificed. She does so even though Iolaus shows resistance to the idea. Maiden sees this as a noble act because she considers it to demonstrate her courage and not her cowardice, again indicating how this is something she does because she wants to be heroic and save everyone.

In all cases, one or more figures demonstrate more resistance than the person who will die (Admetus/Alcestis, Creon/Menoeceus, Clytemnestra-Achilles/Iphigenia, Hecuba/Polyxena, Iolaus/Maiden), which isn’t the case with Andromeda, who in the fragments seems to be the one demonstrating the most active resistance. The characters refuse this resistance for their own reasons, but unlike Andromeda, she begs Perseus to help, actively wanting her sacrifice to be stopped (frag 128). Eventually the character allows herself to be sacrificed, even though the reasons and context are quite difficult and in all cases there is a hint of coercion in the fact that, if they don’t accept, they will either be forced or will condemn the others. With this kind of attitude, they claim it as a way of maintaining dignity, or as a noble act, or as a heroic attitude or something of the sort. Andromeda doesn’t do this, she sees it as a complete tragedy, as a miserable life, and she doesn’t seem to try to comfort herself with the idea that if she accepts being sacrificed, she will be heroic (frag 122). In any case, none of them have their movements limited, as they’re all “willing”. On the other hand, Andromeda is chained, as if, by allowing her freedom, she won’t stay there. The physical immobilization itself is a miserable attempt to immobilize her emotions, to make her conform. She is physically chained, yes, but metaphorically she is also supposed to feel chained by duty to her people… and yet Andromeda isn’t. There is no patriotism in the world that will make her be. Silva (2023, p. 122) is of the opinion that Andromeda’s lament, unlike Iphigenia’s lament, doesn’t demonstrate any longing for the past and no hope that her mother or father will do something for her. There is nothing that will make her invest emotionally to the point of giving up on living, even under coercion.

In fact, Andromeda seems to contrast some elements of the other characters! For example:

Polyxena, in Hecuba, says “By the gods, leave me free; so slay me, that death may find me free; for to be called a slave among the dead fills my royal heart with shame“ (550-552, trans. E.P Coleridge), thought apparently shared by The Trojan Women Andromache when she speaks “Her death was even as it was, and yet that death of hers was after all a happier fate than my life” (630-631, trans. E.P. Coleridge) concerning the death of Polyxena. But Andromeda, when begging Perseus says “take me with you, stranger, whether you want me as a servant, a wife, or a slave” (frag 129, Loeb edition), implying that she would even prefer to be enslaved rather than die, which is the opposite of Polyxena.

In Iphigenia in Aulis, Achilles says “But now that I have looked into your noble nature, I feel still more a fond desire to win you for my bride. Look to it; for I want to serve you and receive you in my halls; and, Thetis be my witness, how I grieve to think I shall not save your life by doing battle with the Danaids. Reflect, I say; a dreadful ill is death” (1410-1415, trans. E.P. Coleridge), reiterating the offer that Iphigenia could supposedly marry him after he saved her (she wouldn’t be obliged to marry in order for him to save her, to be clear. But since Iphigenia had initially wanted to marry, his offer was a way of guaranteeing her something), but between (unlikely) marriage and death, Iphigenia still declines Achilles' offer by saying "let me, if I can, save Hellas" (1420, trans. E.P. Coleridge). On the other hand, Andromeda accepts Perseus' offer that, as a reward for rescuing her, she marry him (frag. 129-129a).

Bocholier (2020, p. 15), when commenting on the plot of The Heraclidae, says “Who but a girl, besides, to embody this absolute fidelity to kin and blood ties, this family order older than the Greece of the cities?”, interpreting that Maiden's sacrifice has a symbolic aspect regarding familial loyalty — that is, Maiden offers herself out of loyalty to her family and her city, which theoretically should be above her own desires. On the other hand, Andromeda seems to deal with a lack of family structure more than a reaffirmation of those relationships. Cassiopeia, her mother, didn’t consider the consequences when she committed hubris (although she obviously didn't want that) and Cepheus, her father, may not have been happy with the sacrifice, but still went so far as to accept his daughter being chained. And when it is all over, Andromeda still leaves with Perseus despite Cepheus' disapproval (a reconstruction theory based on later sources that indicate that Euripides had this plot). There is no reaffirmation of filial loyalty here, although the familial relationship is still complex.

And still on the subject of chaining, while in The Phoenician Women Creon offered Menoeceus the chance to escape to another place and be helped by his father when Creon suggests “But come, my son, before the whole city learns this, fly with all haste away from this land, regardless of these prophets' reckless warnings; for he will tell all this to our rulers and generals [going to the seven gates and the captains]; now if we can forestall him, you are saved, but if you are too late, we are ruined and you will die” (970-976, trans. E.P. Coleridge), Cepheus never gave Andromeda such an opportunity. Menoeceus didn’t run away because he chose to, but Andromeda didn’t run away because she had no choice (frag 122).

In Alcestis, the request needs someone willing to die, without requiring a specific person and desiring live will. But in the myth of Andromeda, she is specifically requested and her willingness isn’t required.

In this sense, it is as if the characters were divided into the following categories:

Certainly voluntary sacrifice, since the willingness was necessary and there was no external agent that forced it: Alcestis;

Ambiguous sacrifice in voluntariness, since although the characters claim their agency by transforming the sacrifice into something that supposedly benefits them, there are still external agents that would possibly prevent them from rejecting it: Polyxena, Iphigenia, Menoeceus, Maiden.

Certainly involuntary sacrifice, since disposition doesn’t matter, there is no claim of agency and there are repeated attempts until the end of the play to escape: Andromeda.

While the other characters died clothed, this kind of dignity is sometimes not afforded to Andromeda: “I was looking at the picture of Andromeda brought down by Perseus naked from the rock” (Hellodorus’ Ethiopica trans. Thomas Underdowne), “Andromeda, fettered to a jutting rock, her hair hanging loose about her shoulders; ye Gods, what loveliness was there exposed to view!” (Dialogues of the Sea 14 trans. H.W. and F.G. Flower). Again, it makes it hard to believe that her sacrifice was considered voluntary or even ambiguous. She is, of course, not always mentioned naked and has often been visually depicted clothed, but the chains still seem a constant. Even when Andromeda is fully clothed, she has still been stripped of her agency. She still feels humiliated, still feels as if she isn’t being treated as a person. This is all still very disturbing for Andromeda, an overwhelming feeling that the end is coming and she can't do anything about it — an immense feeling of helplessness. A princess stripped of any power, quite ironic.

Comparing some lines:

“Who will escort me from here, before my hair is torn?”, Iphigenia asks in 1458. Hair-pulling is a form of violent humiliation known from Greek works, but it’s especially famous in the visual representations in which the Trojan princess Cassandra is depicted with her hair being pulled by Lesser Ajax. Other visual examples that I know of are a visual source that shows Achilles dragging prince Troilus by his hair and two visual sources that show Clytemnestra dragging Cassandra by her hair. With this line, Iphigenia shows that, as much as she saw pride in her voluntary sacrifice, she is quite aware that if she hadn’t accepted, she would have been violently coerced (something that, for example, happened in Aeschylus' version, as indicated in the play Agamemnon). Therefore, by accepting, Iphigenia also demonstrates an attempt to control the dignity with which she dies.

“Then he, half glad, half sorry in his pity for the maid, cut with the steel the channels of her breath, and streams of blood gushed forth; but she, even in death, took good heed to fall with grace, hiding from the gaze of men what must be hidden. When she had breathed her last through the fatal gash, no Argive set his hand to the same task, but some were strewing leaves over the corpse in handfuls, others bringing pine-logs and heaping up a pyre; and the one who brought nothing would hear from him who did such taunts as these, “Do you stand still, ignoble wretch, with no robe or ornament to bring for the maiden? will you give nothing to her that showed such peerless bravery and spirit?”, says Talthybius when reporting the sacrifice of Polyxena in 566-580. Polyxena isn’t shown being held down while she is killed, as happens in some visual representations in which she is immobilized by Achaeans, but rather offering her chest (heart) and throat (trachea) to be cut. By exposing herself without an external agent immobilizing her, Polyxena is given the chance, in her last moments, to be able to quickly move to cover herself, thus dying in a way that she considers dignified (i.e., not naked to the eyes of the enemy). Although her sacrifice is required by the context, her attitude of exposing herself is interpreted as a sign of bravery and, therefore, she receives ornaments, which theoretically should be a form of funerary honor. Such “honor” would hardly have been made available to Polyxena’s body if she weren’t seen as “brave”. If Polyxena had actively resisted, she would have forced herself into it and would have died in a much physically violent way, without any chance to try to gain as much comfort as possible from a miserable death.

While Menoeceus is never threatened with a possibly undignified situation (which makes me wonder if this has something to do with him being a male sacrifice required rather than a sacrificial maiden), Creon's lines “Ah me! what shall I do? Am I to mourn with tears myself or my city, which has a cloud around it [as if it went through Acheron]? My son has died for his country, bringing glory to his name, but grievous woe to me. His body I have just now taken from the dragon's rocky lair and sadly carried the self-slain victim here in my arms; and the house is filled with weeping; but now I have come for my sister Jocasta, age seeking age, that she may bathe my child's corpse and lay it out. For those who are not dead must reverence the god below by paying honor to the dead” in 1310-1321 are structured so that the declaration that Menoeceus' death was heroic precedes the demand for dignified funeral honors. Voluntary death dignified Menoeceus.

Maiden isn’t threatened because her sacrifice isn’t asked for directly, but by saying “Then fear no more the Argive enemy's spear. For I am ready, old man, of my own accord and unbidden, to appear for sacrifice and be killed. For what shall we say if this city is willing to run great risks on our behalf, and yet we, who lay toil and struggle on others, run away from death when it lies in our power to save them? It must not be so, for it deserves nothing but mockery if we sit and groan as suppliants of the gods and yet, though we are descended from that great man who is our father, show ourselves to be cowards. How can this be fitting in the eyes of men of nobility? Much finer, I suppose, if this city were to be capture(God forbid! and I were to fall into the hands of the enemy and then when I, daughter of a noble father, have suffered dishonor, go to my death all the same! But shall I then accept exile from this land and be a wanderer? Shall I not feel shame if someone thereafter asks, [Why do you come here with your suppliant branches when you yourselves lack courage? Leave this land: for we do not give help to the base]?” in 500-519 (trans. David Kovacs) she reveals that her motivation isn’t solely heroic. It isn’t only that she wishes to demonstrate courage and nobility by sacrificing herself for the good of all, but it is also because she recognizes that if the prophecy isn’t fulfilled and no maiden is sacrificed, her people will lose the war and that means dead men and enslaved women, including herself. By sacrificing herself, Maiden prevents herself from being enslaved and also prevents other women from being enslaved. She follows a logic that it’s better to have a glorious death than a miserable life, again her voluntariness linked to the dignity.

The case of Alcestis doesn’t apply in this specific comparison, as the sacrifice couldn’t be coerced.

In contrast, Andromeda feels so humiliated that she compares herself to food, and part of this feeling that her dignity has been taken away from her is motivated by the chain: “to set (me) out as food for the sea monster” (frag 115), “[...] but entangled in close bonds I am presented as food [...]” (frag 122). Devoured by the monster, Andromeda wouldn’t have a quick and clean death, and it would definitely not be a death that would make her feel dignified. She feels like food because she feels dehumanized. She has no hope of trying to find a more "humane" or "dignified" way to die because, once the death is being eaten alive by a monster, there aren't many options.

There are texts, both Greek and Roman, that emphasize Andromeda's feelings at the moment, making it clear how sad she was about being sacrificed and how happy she was to be saved:

Euripides’ Andromeda — “Why have I, Andromeda, been given a share of suffering above all others—I, who in misery here am facing death?”, frag 115; “Feel my pain with me, for the sufferer who shares his tears has some relief from his burden”, frag 119. Loeb edition.

Ovid’s Metamorphosis — “but the breeze moved in her hair, and from her streaming eyes the warm tears fel [...] as overcome with shame, she made no sound: were not she fettered she would surely hide her blushing head; but what she could perform that did she do—she filled her eyes with tears [...] Over the waves a monster fast approached, its head held high, abreast the wide expanse —The virgin shrieked”, Book 4. Translation by Brookes More.

Ovid’s Ars Amatoria — “What was less hoped for by Andromeda, in chains han that her tears could please anyone?”, Book 3. Translation by A.S. Kline.

Philostratus, Imagines — “for she seems to be incredulous, her joy is mingled with fear, and as she gazes at Perseus she begins to send a smile towards him”, 1.29. Translation by Arthur Fairbanks

Nonnus’ Dionysiaca — “Perseus saved Andromeda in her affliction”, Book 18; “old Cepheus is unhappy still, when he sees Andromeda's fear, and the Monster of Olympos coming, after what happened here on earth!”, Book 25. Translation by W.H.D. Rouse.

Andromeda’s unhappiness at being sacrificed may not necessarily indicate her lack of consent to it — after all, Iphigenia in Iphigenia in Aulis also openly expressed her unhappiness and in the end she consented —, but her determination to get help and her immense joy at actually being helped are indications of how unwilling she was. She could have refused it, just as the other characters I’ve given as examples did, but she didn’t. Andromeda wanted this help because she never wanted to be there and she never even tried to regain agency like, for example, Polyxena did — who also didn't want to be in the situation she was in and had no real agency but tried to get the impression of it. Andromeda accepted that she had no agency and showed no signs of wanting to subvert it. It’s as if, while Iphigenia made the sacrifice about her more than the war, Andromeda had no such pretensions. Andromeda not only knows it’s not about her — she also doesn’t want it to be. There is no sense of accomplishment for her, as there may have been for Menoeceus and Maiden. She is in deep despair. In this sense, Euripides' Andromeda more closely resembles the kind of description Aeschylus offered of Iphigenia's sacrifice, in which she wept and screamed and resisted so much that she was immobilized and silenced. That is, she more closely resembles an example where there isn’t a self-sacrifice, but an entirely forced sacrifice without any attempt to regain agency through the sacrifice itself, but the agency being played out in vain resistance (for however much Aeschylus Iphigenia and Euripides Andromeda resisted, it didn’t alter the minds of their people. Andromeda had an strange not affected by the context to be bothered by the situation, but Iphigenia received no such thing).

Therefore, with this, I wanted to argue in favor of the idea that Andromeda's sacrifice, in the sources in general, isn’t voluntary.

ANDROMEDA AND PERSEUS: A LOVE STORY?

Here, I’ll discuss my interpretation of the relationship based on the sources. First, it’s notable that there is an eroticism surrounding the myth of Andromeda. Although this is already evident in many sources, it becomes even more obvious when the god Eros is literally included. In the Greco-Roman literary sources, these are some examples of the emphasis on eroticism in the myth (note that I’m using eroticism as an term for both romance and sexuality):

Above all beware of reproaching girls for their faults, it’s useful to ignore so many things. Andromeda’s dark complexion was not criticised by Perseus, who was borne aloft by wings on his feet. [...]

Ars Amatoria, Book 2. Translation by A.S. Kline.

PHILODEMUS O feet, O legs, O thighs for which I justly died, O buttocks, O pubis, O flanks, O shoulders, O breasts, O slender neck, O arms, O eyes I am mad for, O accomplished movement, O admirable kisses, O exclamations that excite! If she is Italian and her name is Flora and she does not sing Sappho, yet Perseus was in love with Indian Andromeda.

Greek Anthology, 5.132. Translation by W.R. Paton.

TRITON: When he was at the Ethiopian shore here, and now flying low, he saw Andromeda lying fastened to a projecting rock—ye gods, what a beautiful sight she was!—with her hair let down, but largely uncovered from the breasts downwards. At first he pitied her fate and asked the reason for her punishment, but little by little he succumbed to love, and decided to help, since she had to be saved. So when the monster came—a fearsome sight it was too!—to gulp her down, the young man hovered above it with his scimitar unsheathed, and, striking with one hand, showed it the Gorgon with the other, and turned it into stone. At one and the same time was the monster killed, and most of it, all of it that faced Medusa, petrified. Then Perseus undid the maiden’s chains, and supported her with his hand as she tip-toed down from the slippery rock. Now he’s marrying her in Cepheus’ palace and will take her away to Argos, so that, instead of dying, she’s come by an uncommonly good marriage.

Dialogue of the Sea Gods, 14.3. Translation by Henry Watson and Fowler.

[...] Without a dower he takes Andromeda, the guerdon of his glorious victory, nor hesitates.—Now pacing in the van, both Love [Eros] and Hymen wave the flaring torch, abundant perfumes lavished in the flames. The houses are bedecked with wreathed flowers; and lyres and flageolets resound, and songs— felicit notes that happy hearts declare. The portals opened, sumptuous halls display their golden splendours, and the noble lords of Cepheus' court take places at the feast, magnificently served. After the feast, when every heart was warming to the joys of genial Bacchus , then, Lyncidian Perseus asked about the land and its ways about the customs and the character of its heroes. [...]

Metamorphoses, Book 4. Translation by Brookes More.

No, this is not the Red Sea nor are these inhabitants of India, but Ethiopians and a Greek man in Ethiopia. And of the exploit which I think the man undertook voluntarily for love, my boy, you must have heard – the exploit of Perseus who, they say, slew in Ethiopia a monster from the sea of Atlas, which was making its way against herds and the people of this land. Now the painter glorifies this tale and shows his pity for Andromeda in that she was given over to the monster. The contest is already finished and the monster lies stretched out on the strand, weltering in streams of blood – the reason the sea is red – while Eros [Love] frees Andromeda from her bonds. Eros is painted with wings as usual, but here, as it not usual, he is a young man, panting and still showing the effects of his toil; for before the deed Perseus put up a prayer to Eros that he should come and with him swoop down upon the creature, and Eros came, for he heard the Greek’s prayer. The maiden is charming in that she is fair of skin though in Ethiopia, and charming is the very beauty of her form; she would surpass a Lydian girl in daintiness, an Attic girl in stateliness, a Spartan in sturdiness. Her beauty is enhanced by the circumstances of the moment; for she seems to be incredulous, her joy is mingled with fear, and as she gazes at Perseus she begins to send a smile towards him. He, not far from the maiden, lies in the sweet fragrant grass, dripping sweat on the ground and keeping the Gorgon’s head hidden lest people see it and be turned to stone. Many cow-herds come offering him milk and wine to drink, charming Ethiopians with their strange colouring and their grim smiles; and they show that they are pleased, and most of them look alike, Perseus welcomes their gifts and, supporting himself on his left elbow, he lefts his chest, filled with breath through panting, and keeps his gaze upon the maiden, and lets the wind blow out his chlamys, which is purple and spattered with drops of blood and with the flecks which the creature breathed upon it in the struggle. Let he children of Pelops perish when it comes to a comparison with the shoulder of Perseus! for beautiful as he is and ruddy of face, his bloom has been enhanced by his toil and his veins are swollen, as is wont to happen when the breath comes quickly. Much gratitude does he win from the maiden.

Imagines, 1.29. Translation by Arthur Fairbanks.

ANTIPHILUS On a Painting of Andromeda The land is Ethiopian; he with the winged sandals is Perseus; she who is chained to the rock is Andromeda; the face is the Gorgon’s, whose glance turns men to stone; the sea-monster is the task set by Love [Eros], she who boasted of her child’s beauty is Cassiopea. Andromeda releases from the rock her feet inured to numbness and dead, and her suitor carries off the bride his prize.

Greek Anthology, 16.147. Translation by W.R. Paton.

When he saw the girl hanging from the rock, he stiffened—he whom even his enemy had not stunned. Scarcely did he hold his prize in his hand, and the conqueror of Medusa was conquered in the presence of Andromeda.

Liber Quintus. Translation by James Uden. [Detail: there is also the argument that this source is actually a way of de-emphasizing eroticism, for those interested see “A Song from the Universal Chorus: The Perseus and Andromeda Epyllion”]

Regarding visual representations, Odgen (2008, p. 81-82) comments:

Artists also exploited the erotic potential of the suspended Andromeda. Vase painters and wall painters often preferred to represent her clothing diaphanously (e.g. LIMC Andromeda I no. 23, a Sicilian calyx-crater of ca. 350–25 bc, and no. 32, a Roman wall- painting from Boscotrecase). And as with the writers, wardrobe mal- function could be deployed to enhance the effect. One notable example of this is found in the case of a fragment of a Lucanian bell-crater of the early fourth century bc, on which a voluptuous Andromeda holds her thin peplos-dress up in her teeth to preserve her modesty (LIMC Andromeda I no. 22). In ca. 340 bc the female nude entered the canon of Greek sculpture, and this seems to have had an impact on the ways in which Andromeda could be shown. A nude Hellenistic statue, preserved only in the form of a Roman copy reduced to little more than a torso, indicates what could be done. The delicate chain that rests across the top of the girl’s right thigh offers little to her modesty (LIMC Andromeda I no. 157, from Alexandria). No doubt this was the sort of thing Roman writers had in mind when they compared the suspended Andromeda to a statue. Full nudity was too much for the vase painters, and the only completely nude Andromeda to be found on a vase is a burlesque figure of ca. 340–30 bc on a Campanian hydria (LIMC Andromeda I no. 20). From the third century bc and onwards Etruscan and Roman relief-sculptors and wall-painters were less reticent about going all the way (e.g. LIMC Andromeda I nos. 53, 55, 75, 146a, 152). Roman artists favoured three tender vignettes with little or no correlate in the literary tradition, and all of these are to be found in profusion in Pompeian wall-paintings. In one Perseus is shown helping Andromeda down from her place of suspension, with a miniaturised dead ketos sometimes lying at their feet (e.g. LIMC Andromeda I nos. 67–71, 73–4, 78, 83–9, 209–11, 222). In the second, completely absent from the written record, we catch a now fully relaxed Perseus and Andromeda, their troubles behind them, sitting together and gazing at the reflection of the Gorgon-head in a rock-pool. Perseus is evidently recounting his earlier adventures to his new fiancée, perhaps still on the shore where the ketos was killed (LIMC Andromeda I nos.102–4, 109–10, 118, 120, Perseus nos. 66–73). In the third we find Perseus transporting Andromeda through the air, presumably back to Seriphos (LIMC Perseus nos. 229–30).

Furthermore, it must be considered that Eros/Love is represented, in some cases, in ceramics that address the rescue of Andromeda by Perseus, emphasizing the eroticism of the myth (for example, see here).

Gibert (1999-2000), in relation to Euripides' play Andromeda, comments on how it most likely had as its focus not the heroic conquest of Perseus, but the love between Perseus and Andromeda. There are even surviving lines in which the god Eros is invoked to help the pair of star-crossed lovers. One of the possibilities to be commented on is also the chances that Andromeda was the first play to represent a man falling in love. Note that it isn’t “a man in love”, but a “man falling in love” — that is, the moment in which the feeling arises. Furthermore, Andromeda was part of a trilogy that also contained the play Helen, which, unlike Andromeda, has survived. Although Helen has more than one theme, the emphasis on the romantic relationship between Helen and Menelaus is quite obvious, which perhaps allows for the theory that this specific trilogy proposed an approach to mythological romantic relationships. Not only that, but both Andromeda and Helen are a subject of debate in terms of genre, with scholars debating whether they are tragedy, comedy, or something else — much of this debate exists by the fact that Aristotle’s “Poetics” is often used as a reference for the rules of theatrical genres. Euripides, in this trilogy, apparently wasn’t trying to follow the known strict formulas.

The presence of such strong eroticism in the myth of Andromeda is actually something that intrigues me. It intrigues me how, in some ways, their relationship became stronger than Perseus’ heroic conquests. Yes, Perseus is still praised for facing Cetus, saving Andromeda, and then dealing with Phineus, but the focus is still on how he and Andromeda feel about each other. This, at least to my mind, still sounds more like a relationship myth than a conquest myth, although both elements are present and important. Even when we have sources that speak of Perseus' immortalization in the stars, Andromeda is usually emphasized as being immortalized in the stars as well (Nonnus' Dionysiaca, Pseudo-Hyginus' Astronomica, Aratus' Phaenomena).

Regarding Andromeda's reciprocity, Silva (2023, p. 130-131) comments that Andromeda, as a character in an Euripidean play that includes the elements of “escape” and “salvation,” resembles Euripidean characters Iphigenia (Iphigenia in Tauris) and Helen (Helen), and this would include her non-passivity in her escape. She supports this idea with what Erastatones says in Catasterismi 17, where he describes that Andromeda refused to stay her father and mother and went with Perseus of her own free will, and what is said in Pseudo-Hyginus' Astronomica, which gives a similar account that also emphasizes Andromeda's desire. For Silva, the play, therefore, addresses the idea of a girl abandoning her family and homeland in order to follow her lover to an unknown situation. She also recalls that Peterson (1904, p. 101) interpreted Andromeda's decision as a disregard for traditional duties, after all she disobeyed her parents' wishes and left her homeland to go with a stranger. It wasn't supposed to be an easy decision.

Pseudo-Apollodorus records:

[...] But Ammon having predicted deliverance from the calamity if Cassiepea's daughter Andromeda were exposed as a prey to the monster, Cepheus was compelled by the Ethiopians to do it, and he bound his daughter to a rock. When Perseus beheld her, he loved her and promised Cepheus that he would kill the monster, if he would give him the rescued damsel to wife. These terms having been sworn to, Perseus withstood and slew the monster and released Andromeda. However, Phineus, who was a brother of Cepheus, and to whom Andromeda had been first betrothed, plotted against him; but Perseus discovered the plot, and by showing the Gorgon turned him and his fellow conspirators at once into stone. [...]

Library, 2.4.3. Translation by J.G. Frazer.

Regarding this passage, Faria (2023, p. 11) interprets that “it can be inferred that Perseus takes Andromeda's salvation as proof of love and, in order to free her, he faces the monster to which she was exposed and deals with conspiracies and adversities from opponents, such as Phineus” (improvised translation, the original was in Portuguese).

Now that I have established why I think Perseus was motivated by love and that the feeling was mutual, I’ll argue why I think the marriage was beneficial to Andromeda. Again, the comparison territory! Hesione is probably the sacrificial maiden most similar to Andromeda and I wouldn’t be surprised if one was derived from the other. Laomedon, the Trojan king, didn’t pay homage to the gods Apollo and Poseidon by building the walls of Troy, forced by the king of the gods Zeus to do so as punishment for both of them being part of a plan to betray him. This led to the prophecy that a sea monster would be sent to destroy Troy and that the only way to prevent this would be to sacrifice Hesione, one of the princesses. Heracles, seeing her there and talking to her, learned of what had happened. He then told King Laomedon that he would save her and Troy by killing the monster, but that he wanted Laomedon's divine horses as a reward (which, depending on the source, are explained as gifts from Zeus as compensation for the kidnapping of the young and beautiful Ganymede). Laomedon made the promise, but, just as he didn’t fulfill his duty to the gods, he didn’t fulfill his duty to Heracles. As a result, Heracles, along with other Achaeans, sacked Troy with drastic results. Priam, one of the princes, ended up inheriting Laomedon's throne, and Hesione was taken as a prize of war, with Heracles giving her to Telamon for his usefulness in the sack (see, for example, Pseudo-Apollodorus' Library and the Byzantine scholia of The Iliad).

The similarities to Andromeda are obvious, in terms of context:

The event takes place in a foreign/non-Greek place (Aethiopia/Troy);

A hierarchical power figure of the community commits hubris against the gods (Cassiopeia/Laomedon);

Poseidon is involved in both cases (he is requested by the Nereids, who were offended/he is one of the offended gods);

It’s prophesied that a sea monster (in the case of Andromeda, his name is Cetus) will destroy the city (Aethiopia/Troy) as punishment for this hubris;

It’s also prophesied that the only way to avoid the destruction of the city (Aethiopia/Troy) is with the sacrifice of the daughter (Andromeda/Hesione) of the one who offended the gods (Cassiopeia/Laomedon). They’re both maidens and the sacrifice of both is justified as being the "best" for the community;

A Greek hero (Perseus/Heracles) appears, talks to the maiden (Andromeda/Hesione), finds out from her what is happening and negotiates a reward with her father (marriage/divine horses). Both heroes are sons of Zeusand have a mortal father figure (Dictys/Amphitryon);

The monster is defeated, the girl (Andromeda/Hesione) is taken.

There are, however, some crucial differences here, which I’ll comment on. Well, let us return to Euripides. Although the fragments of the play Andromeda aren’t in a 100% sure order, this is one of the possibilities suggested:

Perseus Maiden, if I should rescue you, will you show me gratitude? Andromeda Take me with you, stranger, whether you want me a servant, a wife or a slave. Perseus I have never abused the unfortunate in their unfortunate in adversity, for I may suffer adversity myself. Andromeda Do not bring me to tears by offering my hope; many things may happen that are unanticipated.

Fragments 129-130. Loeb edition.

If we consider that the order is this, then the dialogue would be structured in such a way as to build a scene in which, despite Perseus initially demanding a reward for saving Andromeda, when Andromeda responded with such desperation (indicated by the way she even claims that she would be his slave, as long as he saved her), Perseus apparently realized that this wasn’t the best thing to say and made sure to assure Andromeda that he wouldn’t use her current vulnerability as a way to exploit her (which is why, right after Andromeda suggested slavery as his reward, Perseus claimed that he avoids taking advantage of other people's misfortune). In this case, Perseus would apparently be recognizing Andromeda's lack of power at that moment, knowing that vulnerability would possibly make her enter into exploitative scenarios, and in response he would have tried to assure her that her safety was guaranteed.

If this is indeed the original order of the play, it would make Andromeda's situation quite different from Hesione's. Hesione had no such safety guaranteed to her by Heracles or Telamon; she was actually taken to be enslaved in Salamis. For example, in Pseudo-Apollodorus Library 2.6.4 she is said to have been given as a prize to Telamon (“he [Heracles] assigned Laomedon's daughter Hesione as a prize to Telamon”, trans. J.G. Frazer), in Sophocles’ Ajax she is directly referred to as an enslaved captive (“you, the captive slave's son”, trans. Richard Jebb), and in the Byzantine scholia the scholiast makes Hesione's extremely disadvantageous situation even more obvious by saying “When Heracles sacked Troy, he took as prisoner Hesione, the daughter of Laomedon (and sister of Priam), and gave her as a war-prize to Telamon because he had fought with him” (trans. R. Scott Smith). Hesione has no legitimate status and consequently doesn’t have the legal protection of a wife. She is an enslaved woman, not a free person. We don't have to think about what Andromeda's life would be like if Perseus was the kind of guy who saved a girl from being sacrificed just to get her as a prize, without really considering her safety or feelings, because Telamon already did that with Hesione. We already know that story. Sure, there are a lot of euphemisms for master-slave relationships in the writing of some ancient authors, Briseis and Achilles is probably the most obvious example of this with authors talking about how Briseis' beauty turned him on and oh how he would leave the battlefield from her bed and the like, but even Briseis has been acknowledged for her disadvantageous status in various texts. No one has the slightest doubt that she has no legal protection, no one has the slightest doubt that Achilles has more power over her than any healthy relationship should allow and the Byzantine scholia, just as it recognized that Hesione is a prisoner, recognized that Iliadic Achilles wasn’t really caring about Briseis. But Andromeda? She never had this type of source. There is no euphemism in the world that would make Andromeda, with the amount of sources she has, not have been identified as being in a disadvantageous situation by at least one author. I would understand if she was a obscure character, but she's not.

And to further emphasize how Hesione is a very obvious example of what happens when the hero isn’t genuinely trying to save the girl, consider this fragment from Euripides’ play that is interpreted as Andromeda’s: “I forbid the acquiring of illegitame sons. Though in no way inferior to legitimate ones, they are handicapped by convention and this is something you must beware of” (frag 141). Presumably this line is Andromeda making Perseus assure her that he won’t have any illegitimate children, that is, children other than with Andromeda, whom he is promising to make his wife. The justification is that this will be a problem for the child who, no matter how good they are, will be treated with contempt by social convention. And well, since Hesione is an enslaved concubine and not a wife, Teucer, her son, is illegitimate. And he does have a problem with that. In Book 10 of The Iliad, Agamemnon reminds him that Telamon raising him in his household despite Teucer being a bastard is something that should be rewarded by Teucer bringing glory to Salamis. In Sophocles' Ajax, Agamemnon dismisses Teucer by saying that, as the son of an enslaved Trojan woman, he is also a barbarian and a slave, and as such, Agamemnon has no reason to listen to him. In other sources (Sophocles' lost plays, Euripides' Helen, Ioannis Tzetzes' Ad Lycophronem, Pausanias' Description of Greece, etc), Ajax's death results in Teucer's banishment by Telamon. Teucer's safety in Salamis was assured by Ajax, the legitimate son, caring for him. From the moment Ajax died, Teucer, in his illegitimate condition, also lost his safety. Not only is Hesione the embodiment of what Perseus's assurance is meant to prevent, Teucer is the embodiment of what Andromeda's demand is meant to prevent.

And interestingly, none of the sources mention Perseus having mistresses or illegitimate children, so from what can be assumed from the surviving sources, he was indeed loyal and faithful to Andromeda.

THE SUBVERSION OF ANDROMEDA’S MYTH

Even in the comedy genre, which wasn’t meant to be taken seriously, these aspects of Andromeda remain. In Thesmophoriazusae, Aristophanes wrote a scene parodying Euripides’ Andromeda. Consequently, the characterization of the characters in this absurd situation (the context of this scene is insane, but I honestly don’t think it’s useful for this post) reflects Euripidean characterization and, consequently, Andromeda here is represented as someone who actively mourns and wants help. However, this becomes comical. Lourenço (1995, p. 285-291) argues that Aristophanes parodied this specific play because, similar to Euripides’ Helen (also parodied by him), it was one of the materials that provided the greatest melodramatic potential. The subversion of parody lies in transforming the tragic into the comic and the romantic into a very unromantic scenario. if the subversion of the play, forming the parody, is in making it funny and unromantic, then it reinforces the status of Euripides' original play as the story of a tragic couple in love. Ribeiro (2018, p. 126-139) comments on how well received the play was at the time, capable of arousing a lot of sympathy from the public with the sweet and tragic couple. This type of parody wouldn’t have had the impact it had if it weren’t for the positive reception and the original aspects of Euripides' play. Even today, when calling Andromeda a "controversial" play, the intention tends to be more in the realm of debate about what makes something a tragic play in terms of genre. It usually takes into account what Aristotle says in Poetics, which clearly doesn’t fit with what we know about the structure of Andromeda (just as, for example, it doesn’t seem to fit with Helen) and that’s why there is the debate. It's not about having had a troubled reception.

Gibert says (1999-2000, p. 85-86):

This brings us back to genre. Perseus' love is the only target of Aristophanes' parody that might also be called a structural element of Andromeda's, love story. All of his targets, however, would have contributed to the unusual atmosphere and tone of the Euripidean original: the daring use of Echo, the exotic predicament and exaggerated pathos of the exposed maiden, and the arrival of the gallant hero through the air. So would several other elements of the dramatic situation. When they meet, the two principals are young and unattached, and Andromeda is a parthenos, ripe for marriage. A victim of her father's cruelty, she attracts sympathy through her opening scenes, and her savior Perseus appears to have been no less sympathetic a character. He was at any rate acceptable to Andromeda, and this suggests that the audience too will have wanted the couple's marriage plans to succeed. They do succeed, as everyone surely expected all along. Against this background, Perseus' constant love deserves to be called an ethically serious development of the legend's romantic potential. We do not know whether he expounded other motives or was consistently high-minded, nor whether Andromeda felt anything other than gratitude. In treating joyful true love seriously, however, Euripides enlarged the boundaries of the tragic genre.

In the Greek Anthology, an anonymous epigram presents Andromeda rejecting Perseus and he, enraged, petrifying her:

What Perseus would say after slaying the Monster, when Andromeda refused him: The cruel fetters of the rock have turned thy heart to stone, and now let the eye of Medusa turn thy body, too, to stone.

9.479. Translation by W.R. Paton.

This kind of epigram seems to be intended to be humorous by breaking expectations. Audiences familiar with the typical romantic story would be shocked at how messy everything has become. But then again, this kind of thing is only possible because there has been a breaking of expectations, which was only possible because Perseus and Andromeda was already known as a story of love and gratitude. Andromeda's refusal is supposed to surprise, it isn’t supposed to someone see this and think "aha! The real story that had been hidden!"

Conon, in Narrations 40, offers a rationalized version of the myth that doesn’t include a attempt of sacrifice. And yet, curiously, Andromeda's dissatisfaction with the situation imposed upon her is still evident:

The 40th story tells the history of Andromeda quite differently from the myth of the Greeks. Two brothers were born, Kepheus and Phineas, and the kingdom of Kepheus is what is later renamed Phoenicia but at the time was called Ioppa, taking its name from Ioppe the seaside city. And the borders of his realm ran from our sea [the Mediterranean] up to the Arabs who live on the Red Sea. Kepheus has a very fair daughter Andromeda, and Phoinix woos her and so does Phineas the brother of Kepheus. Kepheus decides after much calculation on both sides to give her to Phoinix but, by having the suitor kidnap her, conceal that it was intentional. Andromeda was snatched from a desert islet where she was accustomed to go and sacrifice to Aphrodite. When Phoinix kidnapped her in a ship (which was called Ketos [sea monster], whether by chance or because it had a likeness to the animal), Andromeda began screaming, assuming she was being kidnapped without her father's knowledge, and called for help with groans. Perseus the son of Danae by some daimonic chance was sailing by, and at first sight of the girl, was overcome by pity and love. He destroyed the ship Sea Monster and killed those aboard, who were only surprised, not actually turned to stone. And for the Greeks this became the sea monster of the myth and the people turned to stone by the Gorgon's head. So he makes Andromeda his wife and she sails with Perseus to Greece and they live in Argos where he becomes king.

Translation by Brady Kiesling.

Conon wanted to rationalize the myth, but still keep it with certain known themes and elements (e.g. Perseus rescuing Andromeda and Cepheus still being an ambiguous figure). And it makes you wonder...couldn't Andromeda's unwillingness be one of those elements?

Therefore, I think that, even looking at the logic of the subversions, my already shared opinions remain.

SECONDARY SOURCES

WEST, M.L. The Hesiodic Catalogue of Women: Its Nature, Structure and Origins. Oxford, 1985.

PHILIPS, Kyle. American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 72, No. 1 (Jan., 1968), pp. 1-23.

BOCHOLIER, Julien. The Ambiguities of Voluntary Self-Sacrifice: the Case of Macaria in Euripides’ Heraclidae. 2020.

LOURENÇO, Frederico. HVMANITAS — Vol. XLV. Tema(s) e Desenvolvimento Temático nos Tesmoforiantes de Aristófanes. 1995.

RIBEIRO, Wilson. Codex – Revista de Estudos Clássicos, Rio de Janeiro, vol. 6, n. 2, jul.-dez. 2018, pp. 123-15

ODGEN, Daniel. Perseus. Routledge, 2008.

SILVA, Maria de Fátima. PROMETEUS - Ano 15 - Número 43 – setembro - dezembro 2023.

GIBERT, John. Illinois Classical Studies, Vol. 24/25, Euripides and Tragic Theatre in the Late Fifth Century (1999-2000), pp. 75-91.

FARIA, Rui Tavares. Calíope: Presença Clássica | 2023.1 . Ano XL . Número 45 (separata 4). “O herói-viajante em Eurípides: missão, errância, reconhecimento e fuga”

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dance in Theseus and Ariadne myth

I would like to comment on an underrated element in the myth of Theseus and Ariadne: dance. I imagine that people already associate dance with Ariadne, especially since in The Iliad, from Archaic Greece, we have the description of Daedalus building a dance floor for her:

[...] And on it the famed crook-legged god made a patterned place for dancing, like that which once in broad Knossos Daedalus created for Ariadne of the lovely hair. There the unwed youths and maidens worth many oxen as their bridal price were dancing, holding each other’s hands at the wrist; and the girls were wearing finest linen, and the youths wore fine-spun tunics, soft shining with oil. And the girls wore lovely crowns of flowers, and the youths were carrying golden daggers from their silver sword-belts. And now the youths with practiced feet would lightly run in rings, as when a crouching potter makes trial of the potter’s wheel fitted to his hand, to see if it speeds round; and then another time they would run across each other’s lines. And a great crowd stood around the stirring dance filled with delight; and among them two acrobats, leaders of the dance, went whirling through their midst [...]

The Iliad, 18.590-606. Translation by Caroline Alexander.

But an often overlooked part is that there is actually another significant dance in this myth! About this description of the shield of Achilles made by Hephaesthus because of Thetis’ request, the Homeric scholia (12th century CE) says:

He wrought a dancing floor on it, etc. (ἐν δὲ χορὸν ποίησε καὶ τὰ ἑξῆς) Hephaistos also carefully wrought on [the shield] a dance that has a similar arrangement of dancers as the one that was created by the inventor Daidalos for Ariadne in the city of Knossos on Crete. For the story is told that when Theseus traveled from Aphidnai to Athens, he arrived just as the tributes—the seven boys and seven girls—were being sent to Minos on Crete. The Athenians were performing this tribute as payment for the treacherous murder of Androgeos, Minos’ son, when he was taking part in the Panathenaia festival and kept winning. Anyways, they say that Theseus willingly enlisted with the those heading off, and when he got to Crete he caught the eye of Ariadne, Minos’ daughter. Because of this he was saved by the skill of Daidalos in the following way. Daidalos gave Ariadne a ball of thread and told her to give it to Theseus so that he could attach the end of the thread to the entranceway. That would allow him to unwind the ball as he entered the Labyrinth, and, once he overcame the beast, he would have a simple and easy way back out of the Labyrinth, which had a complex, interwoven set of passages out. When Theseus got out after overcoming the beast, he along with the other boys and girls weaved a choral dance for the gods in such a way that it reflected his intricate weaving in and out of the Labyrinth. It was Daidalos that came up with and created the practice of choral dance.

Scholia D, 18.590. Translation by Scott Smith et al.

Although this scholia is very late, it certainly drew from older sources. Hesychius (5th/6th century CE) knew about geranos dance and Theseus dancing in gratitude:

[...] The mention of the two "leaders" is amplified by Hesychius. A yeрavovλκós, he says (s. v.), is "the leader of the dance on Delos." The same lexicographer defines the geranos (s. v.) as "a dance," without further elaboration; and the Etymologicum Magnum (s. v.) glosses it merely as "a kind of dance."[...] [...] A somewhat corrupt gloss of Hesychius (s. v. *Aŋλkakòs ẞwμós) speaks of the "running around the altar on Delos in a circle, and being beaten," and says that Theseus began the rite, in gratitude for his escape from the Labyrinth. [...]

The Geranos Dance — A New Interpretation by Lilian Brady Lawler, pgs 113 and 115.

But there is more! Already in the Roman Era, Pollux (2nd century CE) said something similar:

Pollux (4.101) says that the geranos is danced κат�� πλños, one dancer beside another in line, with "leaders" holding the end posi- tions on either side — ἕκαστος ὑφ ̓ ἑκάστῳ κατὰ στοῖχον, τὰ ἄκρα ἑκατέρωθεν τῶν ἡγεμόνων ἐχόντων. He says also that the followers of Theseus were the first to perform the dance, that they danced around the Delian altar, and that they imitated in their dance their escape from the Labyrinth.

The Geranos Dance — A New Intepratation by Lilian Brady Lawler, pgs 112-113.

From a similar period of Pollux, Plutarch (1st/2nd century CE) provides us with information about Theseus and the saved Athenians dancing in celebration of their freedom and the fact that they were alive:

On his voyage from Crete, Theseus put in at Delos, and having sacrificed to the god and dedicated in his temple the image of Aphrodite which he had received from Ariadne, he danced with his youths a dance which they say is still performed by the Delians, being an imitation of the circling passages in the Labyrinth, and consisting of certain rhythmic involutions and evolutions. This kind of dance, as Dicaearchus tells us, is called by the Delians The Crane, and Theseus danced it round the altar called Keraton, which is constructed of horns ("kerata") taken entirely from the left side of the head. He says that he also instituted athletic contests in Delos, and that the custom was then begun by him of giving a palm to the victors

Life of Theseus, 21.1-2. Translation by Bernadotte Perrin.

Plutarch credits this to Dicaearchus (4th/3rd century BCE, if this is Dicaearchus of Messana), indicating the existence of this myth in the Hellenistic Era. And indeed, we have a surviving source that confirms this! Callimachus (3rd century BCE), an author from Hellenistic Era, had already presented it in the Delian Hymn:

[...] Then, too, is the holy image laden with garlands, the famous image of ancient Cypris whom of old Theseus with the youths established when he was sailing back from Crete. Having escaped the cruel bellowing and the wild son of Pasiphaë and the coiled habitation of the crooked labyrinth, about thine altar, O lady, they raised the music of the lute and danced the round dance, and Theseus led the choir. Hence the ever-living offerings of the Pilgrim Ship do the sons of Cecrops send to Phoebus, the gear of that vessel.

Hymn to Delios, 307-315. Translation by A.W. Mair.

We have also a visual representation on the famous François Vase, which is supposed to date from around the 6th century BCE. Although the context isn’t fully known (I’ll explore this later), a dance is depicted and the names next to the characters indicate the connection to the myth of the Minotaur. For example, one of the girls is named as “Ariadne”.

François vase: details of Theseus’s Cretan adventure. Photo courtesy Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici della Toscana. Retired from Guy Herdeen, pg 493.

François vase (Firenze, Museo Archeologico Nazionale): Top Friezes (sides A & B). Drawing reproduced from A; Furtwängler, Griechische Vasenmalerei, München, 1900/1993, plate 13. Retired from Sara Olsen.

One interpretation is that the vase was intended to be the dance performed on Delos by Theseus and the Athenians, mentioned by Plutarch:

One prominent element in the representation of Paris appears as yet unmatched in the metaphor: just how appropriate is the image of Paris as a dancer trying to fight to the metaphor of the cranes attacking the Pygmies? In fact, γέρανος ‘crane’ is the name of the famous dance performed on Delos by Theseus, Ariadne, and the Athenian youths and maidens on their return from Crete. In nature, cranes actually do perform a remarkable group dance all year round, [56] and their symbolic attributes in the Greek bestiary are especially appropriate to the context of the Theseus myth, as Marcel Detienne has shown: the γέρανος dance, which is consistently described as imitating the entry into or the passage from the labyrinth, is, like Ariadne’s thread, an invention of Daidalos. [57] But in form and function both the thread and the dance recall Greek descriptions of the two-headed, twisting line of flight made by cranes migrating from the ends of the earth and back. [58] In epic, the dancing-place on Akhilleus’ shield (cited above, 86–87) is explicitly likened [59] to the one Daidalos contrived for Ariadne in Crete, and the scholia identify the dance being performed by the ἠΐθεοι καὶ παρθένοι ‘adolescents and maidens’ on it as one performed on Crete {91|92} imitating the twists and turns of the labyrinth. [60] In fact, the scholia may be correct: this may actually be the dance called γέρανος that was later performed on Delos (see the discussion below). [...]

The Simile of the Cranes and Pygmies: A Study of Homeric Metaphor by Leonard Muellner.

There is, however, the problem of Ariadne's presence, as literary sources indicate that she was left on Naxos/Dia, that is, she wasn’t present on Delos:

Confirmation that the scholiast was reporting a well-known version of the myth comes from the François vase (ca. 570). One scene on this vase shows Theseus with a lyre leading the fourteen youths in a dance formation, as they alternate by sexes and hold hands. Ariadne stands facing the chorus and holding out a ball of string to Theseus. The old theory that this scene represents the dance on Delos mentioned by Plutarch has been conclusively refuted by Johansen. He cites the presence of Ariadne, who in all accounts of the myth was abandoned or killed before Theseus reached Delos, as well as parallel representations on other vases, to show that the painter of the François vase was depicting the liberation dance of Theseus and his companions on Crete the very same scene that the scholiast reports Homer was describing on Achilles' shield.

Homer and Ariadne by Kathryn J. Gutzwiller, pg 35.

On the other hand, there are those who think that it is a dance performed in Crete (hence the presence of Ariadne) and that it could represent the post-defeated moment of the Minotaur, as described in the Byzantine scholia — I won't present the arguments here because I imagine you can already imagine what they are, that is, ancient literary sources like scholia. However, Guy Hedreen interprets the possibility that François Vase shows the dance at the beginning of the arrival in Crete as an establishment of the relationship between Ariadne and Theseus, and not a post-triumphal dance as is the case in the literary sources: