#Ballet Company of Teatro all Scala

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

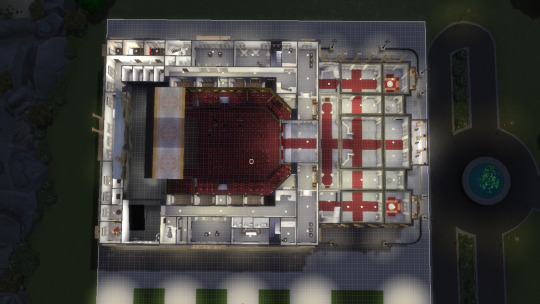

Colon Theatre

The Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires is one of the most important opera houses in the world. Its rich and prestigious history, as well as its exceptional acoustic and architectural conditions, place it on par with theaters such as La Scala in Milan, the Paris Opera, the Vienna State Opera, Covent Garden in London, and the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

In its first location, the Teatro Colón operated from 1857 to 1888 when it was closed for the construction of a new venue. The new theater was inaugurated on May 25, 1908, with a performance of Aida. Initially, the Colón hired foreign companies for its seasons, but starting in 1925, it had its own resident companies - Orchestra, Ballet, and Choir - as well as production workshops. This allowed the theater, by the 1930s, to organize its own seasons funded by the city's budget. Since then, the Teatro Colón has been defined as a seasonal theater or "stagione," capable of fully producing an entire production thanks to the professionalism of its specialized technical staff.

Throughout its history, no significant artist of the 20th century has failed to set foot on its stage. It is enough to mention singers such as Enrico Caruso, Claudia Muzio, Maria Callas, Régine Crespin, Birgit Nilsson, Plácido Domingo, Luciano Pavarotti, and dancers like Vaslav Nijinsky, Margot Fonteyn, Maia Plisetskaya, Rudolf Nureyev, and Mikhail Baryshnikov. Esteemed conductors such as Arturo Toscanini, Herbert von Karajan, Héctor Panizza, and Ferdinand Leitner, among many others, have also graced the theater. It is also common for composers, following the tradition initiated by Richard Strauss, Camille Saint-Saëns, Pietro Mascagni, and Ottorino Respighi, to come to the Teatro Colón to conduct or supervise the premieres of their own works.

Several top-notch maestros have worked consistently here, achieving high artistic goals. They include Erich Kleiber, Fritz Busch, stage directors like Margarita Wallmann or Ernst Poettgen, dance masters like Bronislava Nijinska or Tamara Grigorieva, and choral directors like Romano Gandolfi or Tullio Boni. Not to mention the numerous instrumental soloists, symphony orchestras, and chamber ensembles that have offered unforgettable performances on this stage throughout over a hundred years of sustained activity.

Finally, since 2010, the Teatro Colón has been showcased in a restored building, resplendent in all its original splendor, providing a distinguished setting for its presentations. For all these reasons, the Teatro Colón is a source of pride for Argentine culture and a center of reference for opera, dance, and classical music worldwide.

__________________________________________________________

You will need a 64x64 lot and the usual CC from TheJim, Felixandre, Harrie, Sverinka, SYB, Aggressivekittty, and other marvelous creators!

DOWNLOAD TRAY: https://www.patreon.com/user?u=75230453

(free to play 7/17)

#sims 4 architecture#sims 4 build#sims4palace#sims 4 screenshots#sims4#sims4play#sims 4 historical#sims4building#sims 4 royalty#sims4frencharchitecture

73 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The ballets of Marius Petipa: Swan Lake.

These gifs are of Svetlana Zakharova of the Bolshoi as Odile (black swan) and Ekaterina Kondaurova of the Mariinsky as Odette (white swan).

The story of a beautiful Princess, Odette, who was cursed by an evil magician to be trapped as a Swan by day and turning human at night, Swan Lake is a tale of magic, love, betrayal, and sacrifice.

Swan Lake is one of the most well known classical ballets, with almost everyone being able to recognize the stunning oboe theme carried through the ballet and the iconic white swans act where the corps de ballet dances stunning choreography in all white tutus and feather headpieces, and the dual role of Odette/Odile which is a true calling card of an accomplished ballerina. However, when Swan Lake was first produced at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow in 1877, it was a complete failure from the music (composed by Tchaikovsky) and the choreography (original Julius Reizinger). This ballet did not become a success until Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov revived it for the Imperial Ballet at the Mariinsky Theatre in 1894.

Almost every classical ballet company has their own production of Swan Lake, however many things remain the same throughout. The choreography of the white act corps de ballet, the white pas de deux, the dance of the little swans, Odette’s variation, and the black swan pas de deux, are generally uniformed. However, the most common version of Odile’s variation in act 3 is not the original. The original variation and music is performed at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, with a few other companies including the Stanislavsky Theatre and Teatro Alla Scala using the original music.

Another difference between productions is the ending. Most western productions end with Odette and Prince Siegfried jumping to their deaths into the Swan Lake to free Odette from the curse of Von Rothbart. However, in Russian companies the ending is much different. At the Mariinsky Theatre, the ballet ends with Prince Siegfried killing Von Rothbart and setting Odette free from her curse. At the Bolshoi Theatre, the entire story occurs in the Prince’s dream and the ballet ends with Rothbart creating a storm in which Odette perishes and Siegfried suddenly wakes up alone on the shores of the Lake.

#swan lake#marius petipa#svetlana zakharova#ekaterina kondaurova#bolshoi ballet#mariinsky ballet#favorite ballerina#svetlana gif#kondaurova gif#bolshoi gif#mariinsky gif#ballet#ballerina#prima ballerina#dance#dancer#gif#ballets of marius petipa#ballet gif

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Where performance lives online. Video on-demand and live streaming platform for opera, classical music and ballet on your chosen smart device.

CueTV app is built for connoisseurs and professionals of operas, ballet, and classical music performances. The fastest-growing playlist with personalized recommendations & collections of national premieres, world premieres, concerts, recitals, and more. Get a 14 days free trial to the Cue TV subscription and view some of the world’s finest performances. Stream and download full concerts, recitals, and classical music performances. Watch across all screens in HD: Computer, tablet, smartphone, and smart TVs. Available in 5 languages – English, German, Spanish, French and Portuguese. Cue TV features performances from distinguished international companies, festivals, and venues including Royal Opera House Covent Garden, Teatro alla Scala, Vienna State Opera, Teatro Real de Madrid, Paris Opera, Salzburg Festival, Arena di Verona, English National Opera, Teatro di San Carlo, Theater an der Wien, Mariinsky Theatre, Deutsche Oper Berlin, Verbier Festival and more. Watch opera’s most celebrated artists such as Anna Netrebko, Jonas Kaufmann, Joyce DiDonato, Sir Simon Rattle, Christian Thielemann, Juan Diego Flórez, Elina Garanca, Plácido Domingo, Asmik Grigorian, Teodor Currentzis, Luciano Pavarotti, Valery Gergiev, Benjamin Bernheim and many more.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Don Quixote (2016)

#Ballet Company of Teatro all Scala#Don Quixote#ballet#Patrizia Carmine#2016#Makhar Vaziev#Rudolf Nureyev

0 notes

Text

Sylvia with Martina Arduino, Claudio Coviello and Nicola Del Freo, photo by Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019

Sylvia opened the 2019-2020 ballet season at La Scala. It is a co-production with the Wiener Staatsballett where it opened in November 2018. There have been no changes to Luisa Spinatelli’s sets and costumes or Manuel Legris’ choreography, which suggests that everyone was pleased with how it turned out in Vienna. However, while the overall evening is extremely pleasing, it is La Scala’s dancers who really make it shine, as certain elements of the staging are odd.

Legris gives the dancers lots (and lots) of steps, but it’s maybe impossible to tell this story clearly to a modern audience, most without a classical education: who’s that woman with the bow, why is the man with silver hair sleeping? Legris cleverly tries to help by using the overture as a prologue portraying the huntress Diana (hence the bow) and her passion for Endymion (he of the silver hair). This is how many words the programme ‘synopsis’ needs to sum up the action of the short five-minute prologue:

Diana, the Goddess of the Hunt, sees a double image of herself in Sylvia, who is bound to the goddess through her love of hunting and by a vow of chastity. However, the goddess is in turmoil. Suddenly it is no longer Sylvia that she sees before her, but Endymion, her obsessive lover, whom she has caused to sleep forever so that she can gaze on his youth and beauty without ever breaking her vow. Diana tries to regain control of herself, but Endymion stands before her, full of passion… The goddess surrenders! But soon the sound of horns mercilessly drags her back into reality. Thanks be to the gods, it is Sylvia that now stands before her! Diana seizes her bow. Let the hunt begin.

Got it? I don’t believe that this prologue helps to explain the subsequent action, and possibly confuses things even more with Endymion only appearing again in the final seconds of the ballet, still sleeping, and Diana disappearing for a couple of hours until mid-third act when Sylvia angers her by entering the Temple of Diana. It’s all the fault of Torquato Tasso who wrote his play Aminta in 1573 about the nymph Sylvia, who prefers a good hunt to a smooch with Aminta, until… oh well, never mind. Things were complicated further when librettists Jules Barbier (who wrote the libretto for Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffmann) and Baron de Reinach (who principally was a banker!) added in Orion, the hunter; Eros, the god of love; and the multi-tasking Diana who in this ballet is linked with not only hunting but the moon and chastity. So it’s a hotch-potch of Roman and Greek mythology, though presumably the intention was to mirror Diana’s love for Endymion and Sylvia’s for Aminta. It’s a help to read the (long) synopsis before curtain up.

There is also something that smacks of low budget (or badly-made) scenery, with Spinatelli’s meticulously designed backdrops and wings looking slapdash and shabby, though many of the costumes are gorgeous. Jacques Giovanangeli’s lighting was often unflattering to the sets, highlighting the creases in the cloths, and a lazy follow-spot operator occasionally left the dancers in darkness. It’s unfortunate because Spinatelli’s designs of gauzy, mysterious transparency is ideal for a work of myth and illusion.

There are many highlights, which more than compensate for the baffling plot and the flimsiness of the scenery. Léo Delibes’ wide-ranging music is glorious, from the epic and slightly pompous opening, to the cheery bucolic tunes, to the famous pizzicato variation for Sylvia. The orchestra was brilliantly led by American conductor Kevin Rhodes who was more theatrical and effervescent during the applause than even the lead dancers.

Sylvia with Martina Arduino and Claudio Coviello, photo by Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019

Although Legris has used much of Louis Mérante’s 1876 choreography from the ballet’s Paris premiere, he fills in the gaps with a multitude of steps, and it would be interesting to know the jeté count – there are certainly a lot, and for the whole company too, so it’s a tiring evening for the dancers. But how they dance! The corps de ballet is excellent whether as the fearless huntress companions of Sylvia, the frolicking naiads and fauns, or the peasants enjoying their bacchic feast.

La Scala fields two main casts and they are both strong throughout. Martina Arduino was the opening night Sylvia, followed by Nicoletta Manni. Both are magnificently sure and resilient to the role’s arduous demands – after they enter onstage, the pace never lets up. Manni has an impressive jump, which she can show off continuously in this choreography. She has almost insolent aplomb in many of the trickiest passages, and her long, lithe limbs reveal some exquisite lines. Arduino is softer, especially with her port de bras, and shows more heart, though she too pulls out the big guns for the technical challenges and manages complicated menage sequences with nonchalance. Two very different, but winning, portrayals.

With the fear of running out of adjectives, let’s run down the cast lists. Claudio Coviello as Aminta is a technical marvel and communicative; Marco Agostino in the same role strangely registered less as a character, even though he has a strong jawline and an attractive face, but there were some magical moments, such as when he slows down his pirouettes to a standstill, and an athletic sequence with Manni where they were the mirror image of each other. There were two magnificent Orions: Christian Fagetti then Gabriele Corrado, powerful and assertive both in their dancing and acting and with an abundance of stage presence. There is obviously something odd going on offstage because, gobsmackingly, Corrado, who is one of the company’s most valuable members, doesn’t even have a full-time contract, let alone the role of soloist, yet he consistently performs with excellence in leading roles. I imagine this incongruousness will be corrected soon.

Sylvia Christian Fagetti photo by Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019 09

Sylvia Maria Celeste Losa photo by Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019 01

Sylvia Martina Arduino photo by Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019 14

Sylvia Claudio Coviello photo by Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019 07

Then we come to Eros. Nicola Del Freo and Mattia Semperboni (who was also superb as the peasant in the opening cast) were formidable. They are very different dancers – Del Freo with legs as strong as steel and secure in every movement; Semperboni, more elastic and with stunning virtuosity – but both brought the house down… thrilling. Endymion, as an added role, has little time to dance as he has only the music of Delibes’s overture and this he divides with Diana, but Corrado and Gioacchino Starace made the most of their limited time. And playing Diana was Maria Celeste Losa has become one of the theatre’s go-to performers when you want a job well done, as indeed is the unfailingly fine Alessandra Vassallo in the alternative cast.

As the gymnastic Faun, there was Federico Fresi who always gives his all and is exciting to watch, and Valerio Lanadei (also a personable Shepherd on the first night) who was spot-on in his approach to the character and his dance. Other names which should be mentioned are Vittoria Valerio, Gaia Andreanò, Antonella Albano, Alessia Auriemma, Eugenio Lepera, Camilla Cerulli, Benedetta Montefiore and Domenico Di Cristo, all perfectly cast in smaller, though challenging, roles.

Sylvia, like Legris’ Le Corsaire at La Scala in 2018, is perfect for a company with numerous talents yet few performances, giving many opportunities for everyone to dance, but the opening scene needs rethinking with some stronger mime to explain what is happening, and Spinatelli’s sets deserve a makeover.

Sylvia Nicola Del Freo photo by Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019 18

Sylvia Martina Arduino, Claudio Coviello photo by Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019 22

Sylvia Antonella Albano, Mattia Semperboni, Valerio Lunadei photo by Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019 17

Sylvia photo by Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019 10

Sylvia Nicola Del Freo photo by Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019 08

Sylvia Maria Celeste Losa, Gabriele Corrado photo by Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019 02

Sylvia Vittoria Valerio photo by Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019 04

Sylvia Federico Fresi photo by Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019 03

Manuela Legris’ Sylvia shows La Scala’s dancers on top form Sylvia opened the 2019-2020 ballet season at La Scala. It is a co-production with the Wiener Staatsballett where it opened in November 2018.

#Alessandra Vassallo#Antonella Albano#Christian Fagetti#Claudio Coviello#Gabriele Corrado#Gioacchino Starace#La Scala#Luisa Spinatelli#Manuel Legris#Marco Agostino#Maria Celeste Losa#Martina Arduino#Mattia Semperboni#Nicola Del Freo#Nicoletta Manni#Vittoria Valerio

1 note

·

View note

Text

GIUSEPPE VERDI’S MACBETH AT LA SCALA, DECEMBER 15, 2021

After a trip to Rome for Giacomo Puccini’s Tosca (end of 2019), and after being forced to stay home for a televised mix-and-match surrogate (end of 2020; it should have been Lucia di Lammermoor), the season opening of La Scala chose to go north—well beyond Hadrian’s Wall: heading for the grim, gloomy, and ever-fascinating Dunsinane. While the storyline of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth—with its signature array of raw, earthy components: violence, ruthless (and absolutely blind) ambition, scary sorceries, doom…—is extremely famous, it’s worth noting that Giuseppe Verdi wanted his operatic adaptation (written for the Teatro della Pergola [Florence] in 1847, and largely revised for the Théâtre-Lyrique [Paris] in 1865) to be a faithful, precise counterpart of its literary source. As for the outcome, both audiences and scholars have voiced a pretty wide spectrum of opinions over the years. This specific production of Macbeth (directed by Davide Livermore; with Giò Forma, Gianluca Falaschi, Antonio Castro as set/costume/light designers respectively) seemed to abide by two basic principles. First, fill the stage with a great deal of items: colors, machinery, videos, shiny interiors, panoramic exteriors, walking extras… Second, keep the narration as customary as possible. The setting did migrate from medieval Scotland to a mildly sci-fi version of some contemporary big city (my best guess would be Midtown Manhattan). Rather than a warrior/general who murders his King in order to ascend to the throne, Macbeth is the number two/number three guy in a company who murders the number one guy in order to take his job. But everything stuck to the most traditional game plan; as long as you’re aware that Macbeth’s castle is in fact a luxurious two-story penthouse at the top of a massive skyscraper, you’re all set.

Zooming in on the how, I’d say this Macbeth was truly a tale of two characters. Luca Salsi’s take on the title role was somewhat rigid and unvarying. Overexcitement and anger (anger with a touch of terror, anger with a touch of hope, etc.) were there all along. He never appeared to evolve, and he never appeared to actually stand any chance of succeeding (I mean: of becoming king and remaining one for a while). On the other hand, Anna Netrebko as Lady Macbeth was quite the driving force. Even if her voice wasn’t consistently amazing (as an example, her Cavatina «Vieni! T’affretta! Accendere» was a bit of a bumpy ride), her artistry was. The highlights of her performance were nothing short of memorable; I’d cite the toast during the banquet of Act II (a sort of dark forerunner of the one you find in La traviata) and—no surprises here—the sleepwalking scene, where she managed to flirt with silence, complete stasis, and ultimate dismay in an effortless, almost child-like fashion. Besides, if I pan back to the outset I’m positive it only took a few seconds—several bars at the beginning of the Prelude—for Riccardo Chailly and the orchestra to suggest what their own rendition of Macbeth was going to look/sound like. Briskness, clarity, loudness were dominating. And urgency. It was like, OK. The narrator of this story is in a hurry, he/she leaps from one phrase into another because it all happened a moment ago, it’s a true-crime story and everyone must know—the sooner, the better. (I was captivated by a number of unexpected musical apparitions that put little holes into an otherwise steely structure, such as a couple of extended, mesmerizing solos from the witches’ ballet of Act III [it might have been a bass clarinet, and an English horn maybe?] and the spectacular line of trumpets which announced the final battle in Act IV).

0 notes

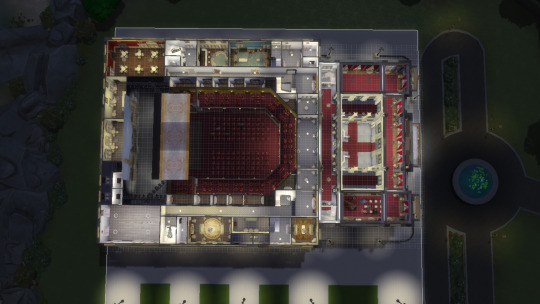

Photo

Kuznetsova, Maria (1880–1966) Russian soprano whose vast repertoire, expressive voice, and powerful acting place her in the highest rank of singers in the early 20th century. Name variations: Mariya Nikolayevna Kuznetsov; Marija Nikolaevna Kuznecova. Born Maria Nikolaievna Kuznetsova in Odessa, Russia, in 1880; died in Paris, April 26, 1966; daughter of Nikolai Kuznetsov; married to a son of Jules Massenet.Maria Kuznetsova was born into the brilliant cultural universe of late tsarist Russia, a world of profound contrasts between glittering balls, ballets, and operas, and the oppressive poverty and illiteracy of the peasantry. From Maria's earliest years, the newest ideas in music, literature and the theater were discussed in her home. Her father Nikolai Kuznetsov was a highly regarded painter whose portrait of the composer Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky has become universally recognizable. Initially, Maria showed great talent as a dancer, and she first appeared on stage in ballet at St. Petersburg's Court Opera. Soon, however, she decided to become a singer, studying for a number of years with Joakim Tartakov. Her 1905 operatic debut at the Mariinsky Theater as Marguerite in Gounod's Faust was an unqualified triumph. Acclaimed as a star, Kuznetsova took part in several operatic premieres, including that of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh on February 20, 1907. Her starring roles over the next few years included Tatiana in Eugene Onegin, Traviata, Madame Butterfly, and Juliette in the Gounod opera Roméo et Juliette. Starting in 1906, she began to sing outside Russia, performing in both Berlin and Paris.Paris quickly became Kuznetsova's second artistic home. Much beloved at both the Grand Opéra and the Opéra-Comique, she appeared in various French roles, including Chabrier's Gwendoline (1910) and Massenet's Roma (1912), as well as in the standard roles of Aïda and Norma. In 1909, Kuznetsova's international reputation was further enhanced when she made her debut at Covent Garden. That same year, she crossed the Atlantic to perform at New York City's Manhattan Opera House as well as in Chicago. In 1914, Kuznetsova returned temporarily to dancing, appearing with great success both in Paris and in London, where she created the role of Potiphar's wife in the Richard Strauss ballet Josephs-Legende. She also sang the role of Yaroslavna in the first British performance of Aleksander Borodin's Prince Igor. Given at the Drury Lane Theater and conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham, this was the legendary "Russian season" that introduced a wealth of new Russian opera and ballet to the English-speaking public.As a Russian patriot, Kuznetsova felt dutybound to return home at the start of World War I, performing on stage as well as in benefit concerts for the war effort. In 1916, she braved the Uboat-infested Atlantic to perform once more in the United States. On her return to Russia in 1917, she saw her country first overthrow tsarist tyranny and then quickly descend into anarchy, with the year ending in a seizure of power by the Bolsheviks. Determined to escape the Communist regime and Vladimir Lenin's proletarian dictatorship, Kuznetsova succeeded in fleeing by ship to Sweden, having disguised herself as a cabin boy and then hiding in a trunk. Virtually penniless, she supported herself in her Swedish refuge for the next several years by giving song recitals with the tenor Georges Pozemofsky, also performing as a dancer during the same program.By 1919, Kuznetsova's career was once more on track when she was invited to sing major roles at the Copenhagen and Stockholm opera houses. In 1920, she appeared again on the stage of Covent Garden, and the same year she settled in Paris, which had been transformed into a center of emigres from revolutionary Russia. Married to a son of the French composer Jules Massenet, Kuznetsova was a major personality in the social and artistic life of interwar Paris. Versatile as ever during these years, she not only sang operatic roles, but also appeared in operettas and even experimented with a new career as a motion-picture actress. In 1927, she took on another role, as impresario of a new opera company comprised largely of Russian emigres, the Opéra Russe, which survived until 1933 when it succumbed to the economic depression.During the Opéra Russe's relatively brief but brilliant existence, Kuznetsova was not only its director but its unchallenged prima donna. Specializing in the Russian operatic repertoire, it had Paris as its base but made guest appearances at major opera houses throughout Europe, including Barcelona, London, Madrid, as well as at Milan's La Scala. In 1929, Kuznetsova and her company toured South America, presenting several previously unheard works in Buenos Aires, including Mussorgsky's The Fair at Sorotchinsk and Rimsky-Korsakov's Snegourotchka (The Snow Maiden). As late as the mid-1930s, Kuznetsova was still singing professionally. In 1934, she replaced the celebrated Conchita Supervia for a performance of Franz Lehár's operetta Frasquita, and in 1936 she undertook a strenuous and successful tour of Japan. After her retirement from the stage, she accepted an assignment as artistic advisor of the Russian operatic repertoire at Barcelona's Teatro Lirico. She lived the final decades of her life in Paris, dying there on April 26, 1966.Boasting a repertoire ranging from the entire body of Russian opera to Salome, Aïda, Norma, Mimi and Gounod's Juliette, Kuznetsova not only possessed what critic Alan Blyth has described as a "gleaming voice and shimmering vibrato," but also was a famously beautiful woman whose stage charisma was legendary. Added to this were her talents as a dancer, which led some of her contemporaries to compare her artistry to that of Isadora Duncan . Many have described her superb acting talent as being equal to that of the legendary basso Fyodor Chaliapin. Highly expressive both as a singer and an actress, Kuznetsova left as a tangible legacy only 36 recordings, both acoustic and electrical, made between 1905 and 1928 for the Pathé and Odeon labels. Fortunately, all of these performances are of the highest artistic quality and have been transferred to the compact disc format in Pearl Records' compilation Singers of Imperial Russia. Critic Albert Innaurato has called Kuznetsova "one of the great singers on disc [whose] records have a fragile, tender allure, the glamorous magic in her sound closely fit to a musical sensitivity that is hard to match."

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hello! I come to you with a few questions. 1.) Do you by chance know if male dancers wear dance belts only during performances or if they wear them even during practise? 2.) What's a prestigious ballet company in NY? 3.) What's a prestigious ballet school? (in NY or not). 4.) Are male dancers trained only by male teachers, trained with the girls for pas de deux, or both? Sorry for the barrage of Qs D:

Hi there!

No need to be sorry, I’m here to answer questions after all so here we go:

No, male dancers wear them at all times starting from an early age, also (and especially) during practice.

Depends on your definition of prestigious, but the New York City Ballet and the American Ballet Theater are considered some of the best ballet companies in the world.

If you are interested only in USA schools: The School of American Ballet (NYCB), the ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School, San Francisco Ballet School, Boston Ballet School, Pacific Northwest Ballet School, or Houston Ballet Academy. If you are interested in the top ballet schools in the world, then I’d say Vaganova and Bolshoi Ballet Academies, the Royal Ballet School in London, Paris Opera Ballet School, the school of National Ballet of Canada, The Australian Ballet School and Teatro alla Scala in Milan.

I have already answered this, search the ballet boys tag. Male classes are usually taught by male teachers, but you will find the occasional female teacher. As far as I know, there is no preferred or more common gender for pas de deux teachers, so go with whatever you like. If you are writing about one of the schools and companies mentioned before, you could also look up who teaches what and use that information for your story.

Hope this helps, come back with more whenever you want!

Script Ballerina

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mission accomplished: 100% employment target rate!

In the trying times we are living Coronavirus has flooded the news outlets around the world, with little or no room for other coverage. So I have chosen to report on a very positive story happening in the heart of the Principality of Monaco.

The Princess Grace Dance Academy, founded in 1975 and currently lead by Luca Masala, who was appointed in 2009 by Princess of Hanover, is a top-level multidisciplinary dance school in the Principality and a hub for talent. The Academy has a 100% graduates employment target rate! (Photo insert: Luca Masala @David Herrero)

Under the Presidency of Princess of Hanover, the Ballets de Monte-Carlo, the Monaco Dance Forum and the Princess Grace Academy are governed as a single structure. Overseen by Jean-Christophe Maillot, this entity now boasts the excellence of an international company, the benefits of a multi-disciplinary festival, and the potential of a premium school to transform Monaco into a hub in which all activities related to choreographic art meet.

Since its inception, the Academy has trained several generations of dancers, many of who have become soloists or principal dancers with leading international dance companies. Luca’s final objective is for his students to join reputable dance companies all over the world, and every year he reaches his target 100%!

I asked Luca Masala to put it in his own words: “The mission of the Princess Grace Academy is to educate and train young students to become dancers. When students reach the end of their training, there is only one goal left; find a job to be able to put into practice everything they learned during these years of education. For 11 years, the Princess Grace Academy has achieved 100% results.” He enthusiastically added: “With employment contracts at stake, and I’m happy to announce that the 11th year is a success, our recent 11 graduates have all found jobs!”

(Photo: Luca Masala surrounded by the 11 graduates 2019/2020, during his 10th year anniversary at the Academy @Princess Grace Academy)

Meet the 2019/2020 graduates of the Princess Grace Academy

Mackenzie BROWN (USA), Prix de Lausanne 2019 – Stuttgarter Ballet, Germany

Mackenzie Brown @David Herrero photographer

Mackenzie Brown, USA – PGA graduate 2019:2020 @Princess Grace Academy

Anna Cecilia MEYER (USA/Sweden) – Royal Swedish Ballet, Stockholm, Sweden

Anna Cecilia Meyer @David Herrero photographer

Anna Cecilia Meyer, USA:Sweden – PGA graduate 2019:2020 @Princess Grace Academy

Greta CALZUOLA (Italian) – Ballett Zurich, Switzerland

Greta Calzuola @David Herrero photographer

Greta Calzuola, Italy- PGA graduate 2019:2020 @Princess Grace Academy

Giovanni D’AGATI (Italy) – Ballet Royal de Flanders, Belgium

Giovanni D’Agati @David Herrero photographer

Giovanni D’Agati, Italy – PGA graduate 2019:2020 @Princess Grace Academy

Luca FERRO (Italian) – San Francisco Ballet, USA

Luca Ferro @David Herro photographer

Luca Ferro, Italy – PGA graduate 2019:2020 @Princess Grace Academy

Yuika FUJIMOTO (Japan) – Tulsa Ballet, Oklahoma, USA

Yuika Fujimoto @David Herrero photographer

Yuika Fujimoto, Japan @PGA graduate 2019:2020 @Princess Grace Academy

Juliette KLEIN (Monaco) – Ballets de Monte-Carlo, Monaco

Juliette Klein @David Herrero photographer

Juliette Klein, Monaco – PGA graduate 2019:2020 @Princess Grace Academy

Giulia Gemma MANFROTTO (Italy) – Ballett Dortmund, Germany

Giulia Gemma Manfrotto @David Herrero photographer

Giulia Gemma Manfrotto, Italy – PGA graduate 2019:2020 @Princess Grace Academy

Marco Pio MASCIARI (Italy), Prix de Lausanne 2020 – Royal Ballet, London, UK

Marco Pio Masciari @David Herrero photographer

Marco Pio Masciari, Italy, Prix de Lausanne 2020, PGA graduate 2019:2020 @Princess Grace Academy

Bruno SERRACLARA (Spain) – Northern Ballet, Leeds, UK

Bruno Serraclara @David Herrero photographer

Bruno Serraclara, Spain PGA graduate 2019:2020 @Princess Grace Academy

Kotomi YAMADA (Japan) – American Ballet Theather New York, USA

Kotomi Yamada @David Herrero photographer

Kotomi Yamada, Japan, PGA graduate 2019:2020 @Princess Grace Academy

A prestigious dance institution

Each year around 40 to 50 dancers from all over the world join Princess Grace Academy under the direction of Luca Masala. During 4 years, students 14 to 18 years old take courses in classical, contemporary and character dance, composition, Pilates, music, and dance history. In parallel, the dancers follow standard school instruction, and foreign students take language courses. The teaching staff at the Academy is comprised of professors and artists with international careers that helped reach excellence in teaching.

The Academy has gained prestige and international recognition for its multi-disciplinary training excellence by accomplished teachers and caring staff attentive to the wellbeing of the students in a loving atmosphere. The young dancers blossom to become not only expert dancers but, at the same time, versatile individuals. In this school of life, students learn the importance of responsibility and are encouraged to build their own careers

The Academy’s goal is for students to learn to live together, away from their country of origin and their families, thanks to the help of professional teachers and staff who are really caring human beings. This is a school where students flourish not only into accomplished dancers but also into cultured, well-rounded individuals.

Luca scouts young dancers all over the world by attending reputable contests and selecting the most gifted youngsters. Not an easy task as most academies compete for the same talented dancers. The students of the Academy work very hard in a friendly ambiance and learn the trade that will enable them one day to make their dream come true.

It costs approximately Euro 15,000 for the tuition of each student, who are all granted a scholarship on their merits, only paying for food and lodge. The Princess Grace Academy counts with a partial subvention from the Monaco Government but relies heavily on donations to offset their total yearly costs. In making a contribution, you will help talented students make their dreams come true and become professional dancers!

Students recognized with the illustrious Prix de Lausanne

Both Mackenzie Brown and Marco Pio Masciari, both recent graduates of the Academy Princess Grace, won the Prix de Lausanne in 2019 and 2020, respectively, following the Academy’s trend since 2014.

2014 – David Yudes, Spain, 4th Prize, and Public Prize

2014 – Mikio Kato, Japan, 6th Prize

2015 – Rina Kanehara, Japan, 5th Prize

2017 – Marina Duarte 2nd Prize and Audience Favorite Prize

2018 – Shale Wagman Gold Medal and Nureyev Prize

2019 – Mackenzie Brown Gold Medal, Contemporary Dance Prize, and Audience Favorite award

2020 – Marco Masciari Gold Medal and Contemporary Dance award

The Prix of Lausanne is a contest for non-professional talented ballet dancers between the ages of 15 and 18, aiming to measure their future potential. In this year’s 48th edition that run from February 2-9, 2020, 77 out of the 84 initially selected candidates participated in the competition, and 21 reached the Finals in front of a full house at the Auditorium Stravinski in Montreux. At the end of the Finals, the jury, presided this year by Frederic Olivieri, Director of the Ballet Teatro Alla Scala in Milan and Prizewinner of the Prix de Lausanne 1977, selected 8 Prize Winners.

Thanks to their scholarships, these 8 promising dancers will have the opportunity to enter one of the prestigious partner schools and companies of the Prix de Lausanne.

Finalists who did not won a scholarship receive the sum of CHF 1.000 (approximately 800 Euros). This contest is known for launching the career of most excellent ballet dancers, opening the doors to the best companies.

Today’s Quote

“The Academy is not only a dance school, but it is also a school of life that will help the students integrate into a complex universe. Because to dance is not a job, it is a real way of life!” Luca Masala.

Princess Grace Academy graduates are Monaco’s cultural ambassadors around the world Mission accomplished: 100% employment target rate! In the trying times we are living Coronavirus has flooded the news outlets around the world, with little or no room for other coverage.

#Anna Cecilia Meyer#Ballets of Monte-Carlo#Bruno Serraclara#Giovanni D&039;Agati#Giulia Gemma Manfrotto#Greta Calzuola#H.R.H. Princess Caroline of Hannover#Juliette Klein#Kotomi Yamada#Luca Ferro#Luca Masala#Mackenzie Brown#Marco Pio Masciari#Princess Grace Academy#Yuika Fujimoto

0 notes

Photo

Ballets of Marius Petipa: The Sleeping Beauty

Myriam Ould-Braham (Paris Opera Ballet), Alina Cojocaru (Royal Ballet), and Viktoria Tereshkina (Mariinsky Ballet) in Aurora’s act 1, 2, and 3 variations.

Sleeping Beauty is the most classic of all classical Petipa and Tchaikovsky ballets. The story of a beautiful Princess cursed to sleep for 100 years until she is awoken with a kiss from her true love. The ultimate fairy tale with beautiful tutus, tiaras, and lavish sets in all productions.

The Sleeping Beauty premiered at the Imperial Mariinsky Theatre on January 15, 1890 with Carlotta Brianza dancing Aurora, Paul Gerdt as Prince Desire, and Marie Petipa as the Lilac Fairy. It was considered an immediate success, with much of the acclaim focused on the famous Rose Adagio when Aurora dances with 4 suitors and includes 2 infamous balances where Aurora is en pointe with a beautiful attitude; I highly recommend watching it here. Another sign of how successful it was is after the Garland Waltz (or the Once Upon a Dream music), Petipa was called out to take a bow after that piece. However, there were some people who were not impressed and some were scared that the classical “ballet feerie” would bring out the end of ballet, which up until that moment had intense dramatic plots and true character development. Tsar Alexander III was at the general rehearsal right before the premiere; when Tchaikovsky was called to the Imperial Box, the Tsar told him the ballet was “very nice” which Tchaikovsky took as a slight insult!

The ballet was kept as a Saint Petersburg gem until the first production outside the city took place in Moscow at the Bolshoi Theatre, staged by Alexander Gorsky in 1899. He based his choreography on notes he took while watching Petipa’s version, however his notes were stolen and have never been found. Petipa’s version original version was last performed in 1919 and was replaced with the first Soviet production by Feodor Lopukhov performed in 1922 and the version the Mariinsky still performs today by Konstantin Sergeyev premiered in 1952.

In the west, the story of the Sleeping Beauty was told in ballets prior to Petipa/Tchaikovsky, however Petipa’s version debuted in 1896 at the Teatro Alla Scala. The ballet was the first performance to mark the reopening of the Royal Opera House after World War Two; it was a production by Ninette De Valois and Nikolai Sergeyev with Margot Fonteyn as Auorora, Robert Helpmann, and Dame Beryl Grey as the Lilac Fairy. Throughout the 20h century, the Royal had productions by 5 different productions, however in 2006 the company revived De Valois’ production with Alina Cojocaru (in 2nd gif) as Aurora.

Other productions include Yuri Grigorovich’s at the Bolshoi Theatre, Peter Martins’ at the New York City Ballet, Rudolf Nureyev’s at the Paris Opera Ballet, and Alexei Ratmansky’s at American Ballet Theatre.

#ballets of marius petipa#sleeping beauty#myriam ould-braham#alina cojocaru#viktoria tereshkina#paris opera ballet#royal ballet#mariinsky ballet#pob gif#royal ballet gif#vika gif#favorite ballerina#prima ballerina#ballet#ballerina#dance#dancer#gif#my gif#history#ballet gif

11 notes

·

View notes

Link

CueTV app is built for connoisseurs and professionals of operas, ballet, and classical music performances. The fastest-growing playlist with personalized recommendations & collections of national premieres, world premieres, concerts, recitals, and more. Get a 14 days free trial to the Cue TV subscription and view some of the world’s finest performances. Stream and download full concerts, recitals, and classical music performances. Watch across all screens in HD: Computer, tablet, smartphone, and smart TVs. Available in 5 languages – English, German, Spanish, French and Portuguese. Cue TV features performances from distinguished international companies, festivals, and venues including Royal Opera House Covent Garden, Teatro alla Scala, Vienna State Opera, Teatro Real de Madrid, Paris Opera, Salzburg Festival, Arena di Verona, English National Opera, Teatro di San Carlo, Theater an der Wien, Mariinsky Theatre, Deutsche Oper Berlin, Verbier Festival and more. Watch opera’s most celebrated artists such as Anna Netrebko, Jonas Kaufmann, Joyce DiDonato, Sir Simon Rattle, Christian Thielemann, Juan Diego Flórez, Elina Garanca, Plácido Domingo, Asmik Grigorian, Teodor Currentzis, Luciano Pavarotti, Valery Gergiev, Benjamin Bernheim and many more.

0 notes

Text

Menswear designer Adrien Sauvage swaps London for Los Angeles — and finds inspiration along the way - Los Angeles Times

Los Angeles Times

Menswear designer Adrien Sauvage swaps London for Los Angeles — and finds inspiration along the way Los Angeles Times “There are no other sports where men have taken fashion like these guys have,” he said. “Now all the brands fly them to ... ALSO. Dolce & Gabbana & 'Giselle': South Coast Plaza soiree celebrates Teatro alla Scala Ballet Company · Menswear forecast for ...

0 notes

Text

Giselle with Svetlana Zakharova e David Hallberg @ Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019

Giselle is one of La Scala Ballet’s international calling cards. Together with Nureyev’s Don Quixote, this production has been seen all over the world, and rightly so. The company dances it beautifully, and its staging by Yvette Chauviré (based, of course, on the Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot choreography) would be difficult to better. It is clearly told, the story points being so carefully prepared that focus is always on the right spot at the right time.

The sets and costumes are traditional – using Aleksander Benois’s designs created for the Paris Opera Ballet, with Olga Spessivtseva as Giselle, in 1924 – and tone perfect, with a rich palette of harvest time hues at the opening, and the darkest, most threatening of forests in the second act. His old-fashioned gauzes and painted backcloths work their magic and produce a gasp from the audience on every opening of the curtain. The laying out of the set is superlative with a hidden ramp for the court, including Albrecht, to descend from its lofty castle to join the villagers; the entrance to the cottage that Albrect uses to hide his cloak and sword to ‘disguise’ himself as a peasant is towards the centre of the stage so the entire audience can see the essential moments of concealing and discovering his princely regalia; and a distant church is seen during the second act which is illuminated by the warm light of dawn as its bells chime 4 o’clock.

The costumes are sumptuous, so the villagers’ past harvests were clearly astonishingly abundant. Giselle’s first act costume has a generous, plump skirt, as is seen in Benois’s designs. Bathilde, though, is something of a confusion as her costume is so heavy and ornate that she appears to be the Duke’s wife, therefore Albrecht’s mother, not his betrothed. In addition, having her and the Duke entering hand in hand adds to this feeling whereas I remember, in earlier editions, that the Duke entered first and then presented Bathilde as she came on separately, which makes far more sense.

Giselle with Svetlana Zakharova e David Hallberg @ Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019

The opening cast saw Svetlana Zakharova and David Hallberg in the main roles, bringing them back together after five years. They danced Swan Lake at La Scala in 2014, shortly before Hallberg suffered his devastating injuring (forcing him to cancel his performances at the theatre in Alexei Ratmansky’s The Sleeping Beauty with Zakharova, the following year). How wonderful to report that Hallberg is back in sublime form. He is innately elegant, and his lines are drawn to fit perfectly with those of Zakharova. Though always clear in his mime, he is a subtle actor, and the gentleness as he touches Giselle’s arms from behind as he joins her for their second act pas de deux is typical of his care to give each gesture a meaning. His plié is deep and soft, and the use of his legs and feet are the utmost in expressivity. Zakharova danced beautifully, as the Milanese audience has come to expect, and even though this isn’t her ideal role, she gave a pleasing performance. Her outstanding finesse is in every movement, though she will insist on taking her leg up unnecessarily high on occasions causing her tutu to start slipping down her leg – not a good look. She overdid her makeup a little (though at the back of the house this probably wasn’t seen) which gave her expression a harder edge than is ideal for the young peasant girl.

Giselle with Martina Arduino and Nicola del Freo @ Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019

The peasant pas de deux with Martina Arduino and Nicola Del Freo was magnificent. Arduino would be better suited to playing Giselle or Myrtha, though she danced the steps ably even if she isn’t a natural for the role. Del Freo, however, was thrillingly perfect. His leg and footwork was extraordinary with steely precision and virile cockiness in each step. Maria Celeste Losa played Myrtha at almost every performance. Whether this is because no one else in the company can approach her level is doubtful, but she excelled in the jumps, gave humanity to her austerity, and her pas de bourrée crisscrossing of the stage was mesmerising. Her two main Wilis were Alessandra Vassallo and Emanuela Montanari, two of the company’s most personable dancers yet they gave suitably glacial interpretations with technically assured solos.

Mick Zeni was Hilarion, exuding suspicion, jealousy and finally hatred, and was pitiful in the second act. Equally suited to the role was Marco Agostino who also possesses some fine acting talent as well as great aplomb in his dancing. Christian Fagetti too never fails to deliver, and La Scala now boasts an impressive roster of male talent, which wasn’t so evident a decade or so ago.

Giselle with David Hallberg Mick Zeni @ Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019

Giselle with Maria Celeste Losa @ Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019

Giselle’s mother was played by Beatrice Carbone who is just a couple of years older than Zakharova, but she convincingly inhabited the part from the inside instead of wearing it like a costume. In an alternative cast, however, Daniela Siegrist looked more like a Julie Walters’ character as she bustled about, wringing her hands. Judging these parts can be trickier than tackling the main roles.

Federico Fresi and Antonella Albano were also splendid in the peasants’ pas de deux. Fresi comes with built-in springs in his legs, but it’s a pity that his perpetually anxious look makes him look as though he’s going into battle.

The other Giselle and Albrecht couples during the run were Nicoletta Manni and Timofej Andrijashenko, and Vittoria Valerio and Claudio Coviello. All four gave satisfying readings. The fact that Valerio dances the role well is a given, and La Scala has entrusted it to her many times even though she’s still a soloist with the company. She was paired with Coviello who performed, quite thrillingly, 34 entrechats six in front of Myrtha, and although he was beaten by Andrijashenko on number (36, as Roberto Bolle used to do), they were beautifully executed and on the spot. Hallberg opted for the diagonal series of brises.

Andrijashenko is an extremely good Albrecht and is very much of the upper classes – taking off his cloak and sword probably only fools Giselle. He was sunny and cunning in the first act, though facially he became somewhat invisible in the second act. His Giselle was Manni who was pitch-perfect from the moment she left the cottage – wide-eyed innocence never becoming cutesy, and she made each step appear simple and natural. As a Wili, she was cool but feeling, imploring with her eyes, and loving with the tilt of her head.

It was evident why this ballet remains the pièce de résistance of La Scala’s repertoire.

Giselle with Svetlana Zakharova @ Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019

Giselle with David Hallberg @ Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2019

Review: Giselle at La Scala with Zakharova/Hallberg, Manni/Andrijashenko, Valerio/Coviello Giselle is one of La Scala Ballet’s international calling cards. Together with Nureyev’s Don Quixote, this production has been seen all over the world, and rightly so.

#Alessandra Vassallo#Alexei Ratmansky#Antonella Albano#Christian Fagetti#Claudio Coviello#David Hallberg#Giselle#La Scala#Marco Agostino#Maria Celeste Losa#Martina Arduino#Mick Zeni#Nicola Del Freo#Nicoletta Manni#Roberto Bolle#Svetlana Zakharova#Timofej Andrijashenko#Vittoria Valerio#Yvette Chauviré

1 note

·

View note

Text

Eleonora Abbagnato,Teatro Massimo di Palermo @ Marco Glaviano

There are many, many Italian dancers scattered around companies throughout the world. Some are in the corps de ballet, others are principal dancers, but all continue the tradition that made Italian dancers some of the most famous of all. Even leaving the men aside, we have Pierina Legnani (noted as ‘maybe’ being the first to perform 32 fouetté turns) who was a prima ballerina assoluta at the Mariinsky; Giuseppina Bozzacchi who created the role of Coppélia for the Paris Opera Ballet when she was 16; Fanny Cerrito and Carlotta Grisi (together with Marie Taglioni – herself half Italian – and Lucile Grahn) who created the roles in Perrot’s Pas de Quatre in London; Virginia Zucchi (for whom Petipa created La Esmeralda pas de six), Carlotta Zambelli (the star of the Paris Opera Ballet for three decades), and more recent exports: Fracci, Ferri, Galeazzi, Durante, Savignano, Abbagnato and others who have become principal ballerinas with major international companies.

Eleonora Abbagnato in Puccini by Julien Leste © Rolando Paolo Guerzoni 01

Eleonora Abbagnato in Puccini by Julien Leste © Rolando Paolo Guerzoni

It is Paris Opera Ballet’s Eleonora Abbagnato (also director of the Rome Opera Ballet company) who heads the bill of Daniele Cipriani’s latest starry gala, this time for the 62nd edition of the Festival of Two Worlds in Spoleto, a town which has seen many of the world’s most famous dancers pass through over the last half-century.

The programme, curated by Cipriani, ranges from the great classical repertoire to pieces by important contemporary choreographers, as well as original creations by young Italian dance makers.

Joining Abbagnato in the line-up are Davide Dato, from Biella, who since 2016 has been First Soloist with the Vienna State Ballet (who will dance in George Balanchine’s Tarantella, which the company has in its repertoire); Gabriele Frola, from Aosta, who became principal dancer of the National Ballet of Canada and, at the same time, of the English National Ballet in 2018; and Rachele Buriassi, a soloist at Boston Ballet.

Davide Dato 2017 © Cositore

Rachele Buriassi in Don Quixote © Stuttgarter Ballett

Davide Riccardo

Gabriele Frola © Aleksandar Antonijevic

There is also 18-year-old Davide Riccardo, from Messina, who graduated from the School of American Ballet and, since August 2018, has become the first Italian at the New York City Ballet (and will present Jerome Robbins’s Andantino as a tribute to the NYCB choreographer who also had strong links with Spoleto); as well as six Italian dancers from the Stuttgart Ballet: Fabio Adorisio, Daniele Silingardi, Alessandro Giaquinto, Matteo Miccini, Vittoria Girelli and Elisa Ghisalberti.

Coincidentally, the gala – on Sunday 30 June – coincides exactly with the tenth anniversary of the death of Pina Bausch, and Damiano Ottavio Bigi, who dances with the Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch in Germany, will present his own creation dedicated to the great choreographer and interpreter.

Contemporary choreographers are represented by Claudio Cangialosi, from the Vlaanderen Opera Ballet, who will dance a piece by Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, and Sasha Riva and Simone Repele, formerly at John Neumeier´s Hamburg Ballet and now at the Ballet du Grand Théâtre de Genève, will perform a work by Marco Goecke.

Sasha Riva and Simone Repele

Claudio Cangialosi

Sasha Riva and Simone Repele

Damiano Ottavio Bigi

Rachele Buriassi in Jiří Kylián’s Wings of Wax © Rosalie O’Connor

There are also national premieres by young Italian authors whose talent has been acknowledged abroad: Alessandro Giaquinto and Fabio Adorisio, of the Stuttgart Ballet, present two creations, especially for the Spoleto Festival, danced by the six Italian dancers from the same company. Tommaso Beneventi from the Royal Swedish Ballet will dance with Buriassi (together with Giacomo Castellana of the Rome Opera Ballet) in a world premiere by Francesco Ventriglia on the music of Saint-Saëns’ Danse Macabre.

Among the (non-Italian) guest artists who complete the lineup are Nikisha Fogo and Liudmila Konovalova from the Vienna State Opera who will dance the Le Corsaire pas de deux along with the young dancer from La Scala, Mattia Semperboni, who set the stage alight in Milan recently as the slave. There’s also Friedmann Vogel from Stuttgart, Megan LeCrone from the New York City Ballet, Katja Khaniukova from English National Ballet and Nancy Osbaldeston from the Royal Ballet of Flanders.

Not only is there a fancy lineup – and quite unique – but the gala will be performed in the Piazza del Duomo with the stage backdrop being Spoleto’s stunning cathedral.

Nancy Osbaldeston 1

Nancy Osbaldeston 2

Liudmila Konovalova © Fotografia Massimo Danza 01

Liudmila Konovalova © Fotografia Massimo Danza

Eleonora Abbagnato con le Stelle italiane nel mondo – Sunday 30 June at 21.30.

Some tickets are still available: Festival Di Spoleto – Abbagnato.

Eleonora Abbagnato at Teatro Massimo in Palermo @ Marco Glaviano

Dance in Italy – Spoleto Festival’s Dance Gala with Abbagnato, Vogel, Frola, Dato and many more on 30 June There are many, many Italian dancers scattered around companies throughout the world. Some are in the corps de ballet, others are principal dancers, but all continue the tradition that made Italian dancers some of the most famous of all.

#Carlotta Grisi#Daniele Cipriani#Davide Dato#Eleonora Abbagnato#Francesco Ventriglia#Giuseppina Bozzacchi#Jerome Robbins#Marie Taglioni#Mattia Semperboni#Pina Bausch#Spoleto

1 note

·

View note

Text

Don Quixote with Nicoletta Manni and Timofej Andrijashenko © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018

Rudolf Nureyev’s Don Quixote is a romp. From start to finish it zips along at a frenetic pace, with frenetic steps. That is, except the prologue — Don Quixote’s house — and a prolonged mime scene in the Act Three tavern scene. Unfortunately, for the revival at La Scala, these scenes seem to have been left as an afterthought in the rehearsal process for the dancing is very fine indeed, but the acting is often way off the mark: mistiming of gags, hammy characterisation (old man Don Q staggers around the stage with his legs apart as though he’s wet his nappy), and the unbelievability of the situations. If the characters in their costumes are already overblown, they can be played as real people, not for laughs – they are already absurd and funny from the moment they walk on stage. Overacting kills comedy. Gianluca Schiavoni as Sancho Panza was one of the few saved by restraint.

The dancing by La Scala’s current clutch of 20-somethings however was first rate. Nicoletta Manni radiated mischief and charm and was a Kitri who looks down on her fellow villagers with amusement and pity. It’s as if she knows that soon she will escape from humdrum village life, though marrying a barber is an improbable route out of the village… Act Four: she divorces Basilio and marries Don Quixote?

Manni’s confidence in her technique is supreme – triple pirouettes, her 32 fouettés almost on the spot with double turns throughout, balances found on every arabesque relevé — but she is also blooming as an artist, and became the focal point of every scene she was in.

Don Quixote with Timofej Andrijashenko © Brescia e Amisano Teatro alla Scala

Her Basilio was Timofej Andrijashenko, a fine dancer with danseur noble lines and comportment. He’s not a natural Basilio having none of the wicked glint in his eye that Baryshnikov had (curiously, both men are from Riga) though he does come across as sweet and loveable, so it is understandable that Kitri is smitten. This run marks his debut in the role and he wasn’t completely at ease with Nureyev’s challenging and sometimes awkward choreography, and occasionally tempi slowed down too much to accommodate him, yet the almost impossible combination of four double turns in the air landing each time in arabesque, alternating from left to right, he carried off marvellously. When Leonid Sarafanov danced the role at La Scala in 2011, for example, he chose to do three of these combinations in a diagonal across the stage on the same leg, a simpler version which was in Nureyev’s earlier versions of the ballet (Nureyev dances this variation in the Australian Ballet video filmed in 1972). Andrijashenko needs time to get the steps and the character into his head and body. Later in the year the company will be taking the ballet to Australia and China and he’ll certainly have the success there that he deserves.

04 Don Quixote with Martina Arduino, Marco Agostino © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018

13 Don Quixote with Antonino Sutera © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018

16 Don Quixote with Virna Toppi © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018

Martina Arduino’s fiery and flirty Street Dancer was an enticing appetiser before her debut as Kitri in the last performance of the present run, and Espada was Marco Agostino, (who will be Arduino’s Basilio), who had bravado fun with his cape. The way Nureyev moves the eight toreadors and Espada from the back of the stage to the orchestra pit, with just one shoulder tilted toward the audience, is an example of his masterfulness at handling groups with simple yet effective patterns. Similarly seen with the final act fandango, the gypsy dances and, of course, the end of the first and third acts with the entire company continuing to dance as the curtains close.

Virna Toppi was a cool and confident Queen of the Dryads, and Antonella Albano made a cute Cupid. Antonino Sutera as the Gypsy gave his super-energetic all, as always. Two of the most glittering performances though, came from Kitri’s friends, beautifully danced by Alessandra Vassallo and Caterina Bianchi who were poised, playful and thoroughly charming.

Don Quixote with Nicoletta Manni and Timofej Andrijashenko © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018

Don Quixote shows off first-rate dancing by La Scala’s clutch of 20-somethings Rudolf Nureyev’s Don Quixote is a romp. From start to finish it zips along at a frenetic pace, with frenetic steps.

#Alessandra Vassallo#Antonella Albano#La Scala#Leonid Sarafanov#Marco Agostino#Martina Arduino#Nicoletta Manni#Rudolf Nureyev#Timofej Andrijashenko#Virna Toppi

1 note

·

View note

Text

Don Quixote with Timofej Andrijashenko © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018

In 1959, Rudolf Nureyev, with Ninel Kourgapkina as Kitri, danced Basilio for the first time at the Kirov Ballet in Leningrad. He was 20.

02 Don Quixote with Nicoletta Manni, Timofej Andrijashenko © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018

03 Don Quixote with Nicoletta Manni, Timofej Andrijashenko © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018 (2)

04 Don Quixote with Martina Arduino, Marco Agostino © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018

05 Don Quixote © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018

After he defected to the West in 1961, the role became his calling card around the world, the character suiting his comic talents and mischievous nature.

He restaged the ballet, based on Marius Petipa and Alexandre Gorski, for the Vienna Opera Ballet in 1966. John Lanchbery reorchestrated much of Minkus’ score. He revived it in 1970 for the Australian Ballet with Lucette Aldous, and this is the version that he filmed in a studio with the company in 1972.

In 1971 Rosella Hightower invited him to stage it for the Marseille Opera Ballet, and here Maina Gielgud was Kitri.

Don Quixote with Nicoletta Manni, Timofej Andrijashenko © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018

In one of his books on Nureyev, Alexander Bland wrote,

This version shows the way in which Nureyev managed the great movements on stage even more clearly: the Spanish numbers swirl around the enormous village square and form an ingenious diversity of configuration intended to demonstrate the steps characteristic of Spain.

Although the purely classical sequence of the “vision” of Dulcinea and the Dryads was performed in its entirety – exactly as it was handed down by Kirov tradition – Nureyev preceded it with a scene involving a gypsy camp as a pretext for developing an amorous meeting between Kitri and Basil: moonlit pas de deux under the sails of a giant windmill.

Rudolf Nureyev also shortened the ballet to three acts with prologue: the gypsies, the windmills, the puppet theatre all becoming one scene, followed by the appearance of the Dryads. Nureyev considerably expanded the comedy aspect. In his version, he introduced the spirit of “Commedia dell’Arte”, where Don Quixote would be Pantaloon, Kitri would be Columbine, and Basil, Harlequin, a brilliant, fast moving, leaping master of ceremonies, who runs from one end of the ballet to the other.

07 Don Quixote with Timofej Andrijashenko © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018 01

08 Don Quixote with Nicoletta Manni © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018

09 Don Quixote with Nicoletta Manni © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018 01

September 1980 saw his Don Quixote arrive in Milan with Carla Fracci making her debut as Kitri, at 44, and dancing six performances in seven days (plus a public dress rehearsal the day before the opening).

10 Don Quixote with Nicoletta Manni, Timofej Andrijashenko © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018 (4)

11 Don Quixote with Nicoletta Manni, Timofej Andrijashenko © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018 (5)

12 Don Quixote with Timofej Andrijashenko © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018 (2)

13 Don Quixote with Antonino Sutera © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018

Laurent Hilaire said of Nureyev’s choreography:

He made a revolution on the way to consider a male dancer. All of the big classical ballet was meant to value the woman, and also his work reflected the dance he saw in Denmark, France, England and Russia. He learned from all over the world and he created his own style. You know when it’s a step from Nureyev as soon as you see it. You cannot really compare it, but his choreography is as rich as the language of Shakespeare or Molière.

Don Quixote with Nicoletta Manni, Antonella Albano, Virna Toppi © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018

Boston Ballet mounted Nureyev’s production in 1983, and Anna Kisselgoff wrote in the New York Times:

When Rudolf Nureyev did four alternating double turns in the air to the left and the right, landing each time in arabesque, last night at the Uris Theater, it came as no surprise.

Very few dancers, almost none in fact, can do such a difficult sequence in both directions and it is rare to see them try. Mr. Nureyev, however, continues to scale the Everests of his own creation and when he triumphed in this final variation from ”Don Quixote” with the Boston Ballet, he did it with the casualness of a great actor playing with a throwaway line.

For Nureyev watchers, it was obvious from his first danced step that this was going to be a consistent performance, calculated in its tensions, totally pulled together in a re-emergent sleekness of line.

15 Don Quixote with Nicoletta Manni © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018 (2) 01

16 Don Quixote with Virna Toppi © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018

17 Don Quixote with Giuseppe Conte © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018

Reviewing the Australian Ballet in 1971, Clive Barnes said,

“Don Quixote” is an old ballet that is both gorgeous and ghastly. The music has little more than a cheerful tinkle to it, and the dramatic conventions are far less than adroit, but the choreography (or at least its choreographic traditions—for only a rash man would say nowadays what the authentic choreography is) can be absolutely marvelous.

It exists — in two varying versions more usually attributed to Gorsky than Petipa — in both Leningrad and Moscow. Nureyev’s version owes not too much to either. It tries, most intelligently, to make more sense of the story, and give it a little more progression and humanity. Thus the lovers are not united until the final act, and it is not the hero, Don Basilio, who picks a quarrel with Don Quixote, but Basilio’s rich and stupid rival to Kitri’s hand, the foppish Don Gamache. These are all very pertinent innovations, although in an admittedly, even attractively, ramshackle ballet such as this, such dramatic inconsequentialities matter less than in most.

18 Don Quixote with Nicoletta Manni, Timofej Andrijashenko © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018 (6)

19 Don Quixote with Nicoletta Manni, Timofej Andrijashenko © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018 (7)

20 Don Quixote with Nicoletta Manni, Timofej Andrijashenko © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018 (8)

21 Don Quixote with Maria Celeste Losa © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018

22 Don Quixote with Timofej Andrijashenko © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018 (3)

23 Don Quixote with Nicoletta Manni © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018 (2)

24 Don Quixote with Timofej Andrijashenko © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018 (2) 01

When Nureyev died in 1993, Mikhail Baryshnikov said,

Rudolf emerged to everyone’s surprise in the early ’60s like discovering a wild flower which never existed before. This flower emerged in the middle of nowhere practically, it emerged somewhere in the desert and mountains, a flower of infinite beauty. You could admire it, you could be amazed by it, you could touch it, but you could never cut this flower. Because this flower had very strong roots, very strong stem which has supported that beauty.

Rudolf was an unusual man in all respects, instinctive, intelligent, constant curiosity, extraordinary discipline, that was his goal in life and of course love of performing. He loved strong women, loyal men, he loved his life. I learned a lot from him, although we are very different performers.

I will miss him for the rest of my life. That’s for sure.

Don Quixote with Nicoletta Manni, Timofej Andrijashenko © Brescia e Amisano, Teatro alla Scala 2018

Photo Album: Don Quixote at La Scala with with Nicoletta Manni Timofej Andrijashenko In 1959, Rudolf Nureyev, with Ninel Kourgapkina as Kitri, danced Basilio for the first time at the Kirov Ballet in Leningrad.

#Antonella Albano#Carla Fracci#Don Quixote#La Scala#Maina Gielgud#Mikhail Baryshnikov#Nicoletta Manni#Rudolf Nureyev#Timofej Andrijashenko#Virna Toppi

1 note

·

View note