#ArchitectureAndPolitics

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

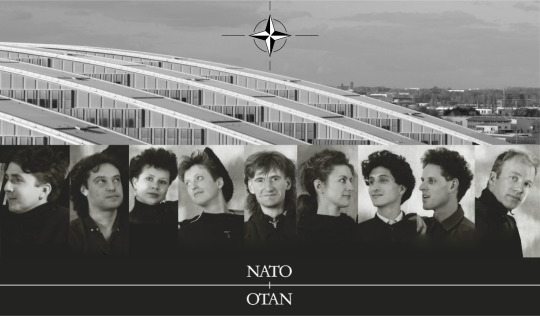

Architectural Narratives: From NATØ's Radical Visions to OMA's Provocative Practice and Beyond

The Architectural Association (AA) in London has been a pivotal institution in shaping contemporary architectural thought and practice. Its influence extends through a diverse array of architects and architectural movements, including the radical narrative-driven approach of NATØ under Nigel Coates, as well as the work of Rem Koolhaas and his Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) and the research-oriented AMO. This narrative draws on the pedagogical lineage of the AA, emphasizing the transformative role of the architect, akin to a draughtsman's contract, in shaping and challenging socio-political landscapes through design.

NATØ, or Narrative Architecture Today, emerged from the Architectural Association in the early 1980s. Under the guidance of Nigel Coates, the group developed an architectural approach that integrated elements of fashion, television, music, video, and nightlife. This was a deliberate departure from the more traditional and introspective work prevalent at the AA. Their narrative architecture aimed to break down professional barriers and engage directly with urban subcultures, reflecting the chaotic and vibrant milieu of 1980s London. They sought to create a participatory urbanism where the city's inhabitants played a central role in shaping their environment, moving away from top-down professional imposition.

The AA has been a crucible for avant-garde architectural education, fostering an environment that encourages experimentation and narrative-driven approaches. Nigel Coates, alongside other influential figures like Bernard Tschumi, cultivated a pedagogical ethos that challenged conventional architectural norms. This environment not only birthed NATØ but also influenced other significant architects, including Rem Koolhaas.

Rem Koolhaas, a prominent figure in contemporary architecture, studied at the AA during the 1970s. His experience at the AA was formative, shaping his architectural philosophy and approach. Koolhaas's Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) has become renowned for its innovative and often provocative designs that challenge traditional architectural boundaries. OMA’s work spans various scales and typologies, from urban planning to iconic buildings, always pushing the envelope of architectural discourse.

In addition to OMA, Koolhaas established AMO, a research-oriented counterpart to OMA. AMO engages in interdisciplinary research and consultancy, addressing broader cultural, social, and political issues. This dual approach—practical architecture through OMA and theoretical exploration through AMO—reflects a comprehensive engagement with architecture’s potential to influence and respond to contemporary challenges.

The notion of the architect as akin to a draughtsman's contract can be understood as a metaphor for the architect's role in mediating between ideas and their material realization. This concept is particularly resonant in the work of both NATØ and OMA/AMO. In Peter Greenaway’s film "The Draughtsman’s Contract," the draughtsman’s meticulous drawings are not just representations but instruments of power and transformation. Similarly, architects, through their designs, wield the power to shape and transform spaces, cultures, and political landscapes.

NATØ’s narrative-driven architecture and OMA/AMO’s provocative and research-oriented projects both exemplify how architecture can serve as a powerful medium for socio-political commentary and change. NATØ's work rejected the traditional boundaries of the profession, promoting an inclusive and participatory urbanism. Their narrative approach infused architecture with symbols and metaphors from everyday life, making it more accessible and engaging.

OMA’s projects, under Koolhaas's direction, often critique and reinterpret urban and architectural conventions. The CCTV Headquarters in Beijing, for example, challenges conventional skyscraper design, while projects like the Seattle Central Library reimagine the role of public space in the digital age. AMO’s research projects further extend this critique, exploring issues such as globalization, media, and politics, and their impact on architecture and urbanism.

The NATO headquarters in Brussels, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), represents a symbolic shift from military opposition to unity and integration. This design, with its interlaced office wings, embodies the narrative of peace and collaboration. The building’s sustainable and flexible design reflects contemporary values and underscores architecture’s role in promoting political and social ideals.

Reflecting on NATO and its architectural counterpart NATØ, an interesting parallel can be drawn. If NATO stands for Narrative Architecture Today, then OTAN, being the reverse acronym, could creatively stand for "Observations on Transformative Architectural Narratives." This maintains the architectural theme while providing a thoughtful and fitting reversal that emphasizes the reflective and analytical aspects of architectural narratives.

The Architectural Association in London has been instrumental in fostering a lineage of architects who challenge and expand the boundaries of architectural practice. Through the radical narrative architecture of NATØ and the innovative, research-driven work of Rem Koolhaas's OMA and AMO, the AA’s influence is evident. These architects embody the role of the draughtsman, not merely as designers but as agents of cultural and political transformation. Their work illustrates how architecture can transcend traditional boundaries, engaging with and shaping the socio-political landscapes of their time. This legacy continues to evolve, influencing contemporary architectural discourse and practice, and ensuring that architecture remains a dynamic and transformative field.

#ArchitecturalNarratives#NATØ#NigelCoates#RemKoolhaas#OMA#AMO#ArchitecturalAssociation#NarrativeArchitecture#UrbanDesign#Postmodernism#ContemporaryArchitecture#ArchitectureAndPolitics#DesignInnovation#ArchitectsAsStorytellers

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Ruins are dead architecture". Arata Izozaki.

Arata Isozaki: Re-Ruined Hiroshima

Imagine how should we as architects rebuild cities starting from ruins.Here are some examples from Arata Isozaki’s megastructures which reminds this situation, but first we must realize what Isozaki wrote forty years ago, curiously it is what happens in some regions of the world right now:

“Incubated cities are destined to self-destruct , ruins are the style of our future cities, future cities are themselves ruins, our contemporary cities, for this reason, are destined to live only a fleeting moment, give up their energy and return to inert material. All of our proposals and efforts will be buried and once again the incubation mechanism is reconstituted, that will be the future.” Arata Isozaki.

Seguir leyendo

#deadarchitecture#startingfromruins#postwararchitectue#architectureandpolitics#architecture&politics#arquigraph#arata isozaki#architectural drawings#collage city#city in ruins#megastructures#rebuild cities#utopies#metabolists#ideas drawn#starting from ruins#imaginary cities#fictional landscapes#ruins#visionary cities#fictionallandscapes

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

Drawing the Unbuilt: A Reflection on Architectural Vision and Contemporary Relevance

In the late 1980s, I was a student in London, working at Skidmore Owings and Merrill, engaged in the design of open public spaces for the water courts of Canary Wharf. At the time, London was in the midst of an architectural transformation, one that would symbolize its global financial ambitions. The project was marked by collaboration with Gabriel Smith and Merritt Bucholz, and beneath the polished exterior of corporate architecture lay a deep undercurrent of political manoeuvrings, ambition, and creative tension.

The drawing I produced, now seen here, was never merely a technical document. It was a narrative, an expression of a vision that was as fluid and dynamic as the space it sought to represent—a market structure with opening roofs and sides, designed to create a flexible, permeable boundary between the interior and the city beyond. It was a conceptual structure, one whose design was as much about politics as it was about function, navigating the expectations of the Reimann brothers of Olympia & York, who sought a new, modern city within a city.

While the building itself was never constructed, the drawing lived on. Combining plan, section, and elevation into one composition, it became more than just a proposal—it was an argument for the role of architectural imagination in the public realm. The project manager, Jeff McCarthy, saw something in it worth displaying in his office. The piece transcended its utilitarian purpose and took on a life of its own, a visual essay that encapsulated a moment in London's architectural history.

Fast-forward to today, and the context in which architecture operates has shifted dramatically. The fluidity and openness imagined in that drawing now resonate in new ways. Contemporary architecture often finds itself caught between the demands of efficiency, sustainability, and rapid urbanization, with the creative process constrained by regulations, market forces, and an obsession with digital precision. The human hand, once the primary tool for interpreting space, has been partially replaced by algorithms and 3D modelling, distancing us from the tactile intimacy that pen and ink once afforded.

Yet, the drawing itself remains timeless—a reminder of architecture's potential to reimagine public space as a living entity, adaptable and responsive. In a world increasingly defined by smart cities and hyper-automation, the ethos behind that market structure—its flexibility, its engagement with the public, its openness—feels more relevant than ever.

Architectural discourse today is at a crossroads. We wrestle with the challenges of climate change, housing crises, and digital dominance. But perhaps the answer lies not just in future technology, but in revisiting the past, in recalling moments like this one, where the hand and the heart guided design. The market structure, though never built, stands as a symbol of architecture’s deeper responsibility: to imagine spaces that serve not just our functional needs, but our human aspirations.

We live in a time when the physical boundaries of architecture are blurring—when buildings are not just structures but platforms for interaction, collaboration, and exchange. That market, in its ideal form, was a precursor to this dialogue, and its spirit lives on in the designs we craft today. In reawakening this drawing, we are reminded that architecture’s greatest strength lies in its capacity to evoke, inspire, and ultimately, to adapt.

The real legacy of that drawing is not in the ink or paper, but in the ideas it fostered, and the possibility it represents for today’s architects—to challenge, to provoke, and to create spaces that transcend the physical, offering instead an invitation to engage with the city in new and unexpected ways.

#ArchitecturalJourney#UnbuiltArchitecture#DesignReflection#CanaryWharf#UrbanSpaces#ArchitecturalVision#ContemporaryArchitecture#DrawingToBuild#SOMLondon#PublicSpaceDesign#ArchitectureAndPolitics#ArchitecturalNarrative#DesignLegacy#architecture#berlin#area#london#acme#chicago#puzzle#edwin lutyens#oma#massimoscolari

0 notes