#Anne Houghton

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

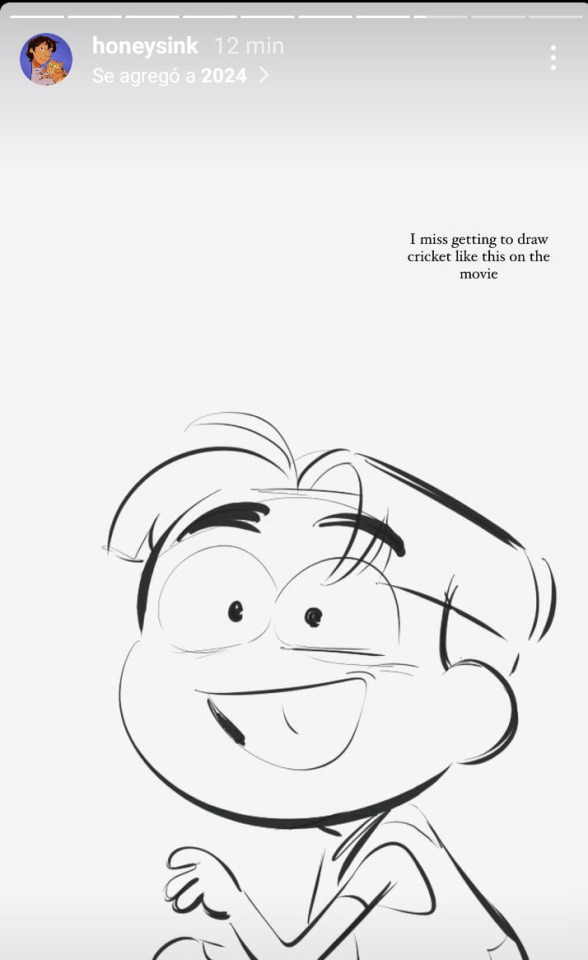

Cute Cricket doodle by Jen Begeman via IG Stories.

"I miss getting to draw Cricket like this on the movie" oh right, let's hope to hear about it next week on the Disney Branded Television panel at TCA Winter Press Tour. 👀

#Big City Greens#BCG#Big City Greens The Movie#Big City Greens: The Movie#Chris Houghton#Shane Houghton#Anne O'Brian#Ariel Vracin-Harrell#Jen Begeman#Disney Television Animation Films#Disney TVA Films#Disney Channel Original Movies#DCOMs#Disney+ Original Animated Movies#Disney Plus Original Animated Movies

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

The thing with October is, I think, it somehow gets in your very blood. Unapologetically. Almost ruthlessly.

— Anne Sexton, "The Awful Rowing Toward God" (Houghton Mifflin, 1975) (via Thoughts)

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Princess Anne as Chancellor of the University of London, visiting the London School of Economics, Houghton Street, London, on 08 May 1986.

#she's so beautiful#pretty princess#HER SMILE#SO SOFT#🥰🥰🥰#princess anne#princess royal#throwback#brf#british royal family

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books Read 2024

David Bowie (Little People, Big Dreams) / Ma Isabel Sánchez Vegara ; Ana Albero (ill.) (Francis Lincoln Children’s Books, 2019)

Angels and Insects / A. S. Byatt (Chatto & Windus, 1992)

How to Stay Alive in the Woods / Bradford Angier (Collier Books, 1962)

Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes / Edith Hamilton (Grand Central Publishing, 2011)

True Stories / Sophie Calle (Actes Sud, 2018)

The Lottery and Other Stories / Shirley Jackson (The Modern Library, 2000)

The Healthy Deviant: A Rule Breaker’s Guide to Being Healthy in an Unhealthy World / Pilar Gerasimo (North Atlantic Books, 2020)

The Ascent of Man / J. Bronowski (Little, Brown and Company, 1973)*

David Bowie: His Life on Earth, 1947-2016 / Allison Adato (ed.) (Time Inc. Books, 2016)

“The Paranoid Style in American Politics” / Richard Hofstadter, in: Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, The Paranoid Style in American Politics, Uncollected Essays 1956-1965 (The Library of America, 2020)

Underworld / Don DeLillo (Scribner, 1998)

The Primal Wound: Understanding the Adopted Child / Nancy Newton Verrier (Gateway Press, Inc., 1993)

Moon Shot: The Inside Story of America’s Race to the Moon / Alan Shepard & Deke Slayton (Turner Publishing, Inc., 1994)

Nevada / Imogen Binnie (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022)

Collected Short Stories and the novel The Ballad of the Sad Café / Carson McCullers (The Riverside Press ; Houghton Mifflin Company, 1955)

The Discovery of the Titanic / Robert D. Ballard w/Rick Archbold ; Ken Marschall (ill.) (Warner/Maidon Press, 1987)

The J. Paul Getty Museum Handbook of the Photographs Collection / Weston Naef (The J. Paul Getty Museum, 1995)

Changing the Earth: Aerial Photographs / Emmet Gowin ; Jock Reynolds (Yale University Art Gallery in association with the Corcoran Gallery of Art and Yale University Press, 2002)

“There’s an Awful Lot of Weirdos in Our Neighborhood” & Other Wickedly Funny Verse / Colin McNaughton (Simon & Schuster, 1987)*

The Anatomical Tattoo / Emily Evans (Anatomy Boutique Books, 2017)

Artists Books / Dianne Perry Vanderlip (cur.) (Moore College of Art ; University Art Museum, Berkeley, 1973)

Risomania: The New Spirit of Printing / John Z. Komurki (Niggli, imprint of Braun Publishing AG, 2017)

American Music / Annie Leibovitz (Random House, 2004)

Atonement: A Novel / Ian McEwan (Anchor Books, A Division of Random House, Inc., 2003)

The Land Where the Blues Began / Alan Lomax (Pantheon Books, 1993)

Snoopy to the Moon! (Peanuts Space Adventures) / Jason Cooper ; Tom Brannon (ill.) (Peanuts Worldwide LLC ; Happy Meal Readers ; Reading Is Fundamental, 2019)

Just for Fun / Patricia Scarry ; Richard Scarry (ill.) (A Golden Book; Western Publishing Company, Inc., 1960)

The Emotionally Absent Mother: How to Recognize and Heal the Invisible Effects of Childhood Emotional Neglect / Jasmin Lee Cori (The Experiment, 2017)

A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing / Eimear McBride (Coffee House Press, 2014)

Bluets / Maggie Nelson (Wave Books, 2014)

The Secret History / Donna Tartt (Ballantine Books, 2002)

Touch Me I’m Sick / Charles Peterson (powerHouse Books, 2003)

Rose-Petal’s Big Decision (Rose-Petal Place) / Nancy Buss ; Pat Paris & Sharon Ross-Moore (ill.) (Parker Brothers, 1984)*

9½ Weeks: A Memoir of a Love Affair / Elizabeth McNeill (Berkley Books, 1979)

Keep Coming Back / Julia Clinker (Nexus Press, 2001)

Parable of the Sower (Earthseed #1) / Octavia Butler (Seven Stories Press, 2016)

Parable of the Talents (Earthseed #2) / Octavia Butler (Seven Stories Press, 2016)

Great Expectations / Charles Dickens (Cherish, [1994])

I’ve Got a Time Bomb: A Novel / Sibyl Lamb (Topside Press, [2014])

My Brilliant Friend: Book One: Childhood, Adolescence (The Neapolitan Novels #1) / Elena Ferrante ; Ann Goldstein (tr.) (Europa Editions, 2012)

Artists’ Books: A Cataloguers’ Manual / Maria White, Patrick Perratt, Liz Lawes on behalf of ARLIS/UK & Ireland Cataloguing and Classification Committee (ARLIS/UK & Ireland ; Art Libraries Society, 2006)

The Book as Art: Artists’ Books from the National Museum of Women in the Arts / Krystyna Wasserman (Princeton Architectural Press, 2007)

Alas, Babylon / Pat Frank (Perennial Classics, 1999)

To the Lighthouse / Virginia Woolf (The Hogarth Press, 1967)

The Photograph as Contemporary Art (World of Art), 3rd ed. / Charlotte Cotton (Thames & Hudson, 2014)

Swamp Water / Vereen Bell (Little, Brown and Company, 1941)

Ongoingness: The End of a Diary / Sarah Manguso (Graywolf Press, 2015)

Selected Poems / T. S. Eliot (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1964)

The New Way Things Work / David Macaulay ; Neil Ardley (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998)

The Little Friend / Donna Tartt (Vintage Books, A Division of Random House, Inc., 2003)

At the Same Time: Essays and Speeches / Susan Sontag ; Paolo Dilonardo, Anne Jump (eds.) (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2007)

It’s All Absolutely Fine: Life Is Complicated So I’ve Drawn It Instead / Ruby Elliott (Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2017)

Things Fall Apart / Chinua Achebe (Penguin Books, 2017)

Beyond Katrina: A Meditation on the Mississippi Gulf Coast / Natasha Trethewey (University of Georgia Press, 2010)

A Humument: A Treated Victorian Novel (Final ed.) / Tom Phillips (Thames & Hudson, 2016)

Tree of Codes (2nd ed.) / Jonathan Safran Foer (Visual Editions, 2011)

Gutshot: Stories / Amelia Gray (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015)

Equus / Peter Shaffer (Scribner, 2005)

National Geographic, vol. 136, no. 6 (December 1969) “Space Record”

Sun Moon Earth: The History of Solar Eclipses from Omens of Doom to Einstein and Exoplanets / Tyler Nordren (Basic Books, 2016)

Pittsburgh’s South Side (Images of America) / Stuart P. Boehmig (Arcadia Publishing, 2006)

Books read in 2024; asterisks * denote rereads. Favorites this year were Ian McEwan & Donna Tartt, LOVE a good coming-of-age story with a perceptive & melodramatic protagonist set in that liminal period between childhood and adulthood!! Pretty sure the main reason I grabbed the Donna Tartt books while thrifting was just from seeing the occasional tumblr user obsess about them, and oh man I was not disappointed! It is rare that I speed through a 600-page novel but, ugh, the way she puts words together is so riveting. Dickensian levels of detail! Speaking of which, I did actually read a Dickens book this year, Great Expectations, which ended up on my list a few years ago after a stranger on the bus tried to initiate conversation with me by asking what I was reading. He said that Great Expectations was his favorite book, and I was like, “oh cool, I read that in high school, I liked it,” and he was like, super excited that I had also read his fave classic. Well, later on after I got off the bus, I realized I had gotten that title confused with The Great Gatsby (which I did read in high school along with millions of other Americans probably) and I felt bad for accidentally deceiving Random Guy on the Bus, so the next time I saw a copy of Great Expectations at the thrift store, I picked it up. Not bad!!

What else? I’m very late to the Elena Ferrante party, but I enjoyed My Brilliant Friend in text form wayyy better than my attempt to listen to the audiobook five years ago (I just could not follow the audio version and couldn’t get into the story). Charles Peterson’s Touch Me I’m Sick was a fave photo book of the year; it had been on my list since 2015, whoops (I had to interlibrary loan it). This year I read a pretty even mix of books from my to-read list (earliest titles added 2015), books from my to-read pile (items I have thrifted within the past few years), and random interruptions to those lists. Oh, I also read a TON of essays and articles about artists’ books (not listed above) for the class I took at Rare Book School in the summer. I read a couple painfully healing books about motherhood and adoption (The Primal Wound / Nancy Newton Verrier & The Emotionally Absent Mother / Jasmin Lee Cori) that I wish I could’ve encountered earlier in my life but also who knows, maybe this year was cosmically the perfect time for my brain to be receptive. I picked up Alas, Babylon because it was a title I remembered seeing my dad reading at the kitchen table one time when I was a kid. (It’s a 1959 novel about surviving in post-nuclear apocalypse small-town Florida; there is some light misogyny and racism of its era, but also the librarian plays an important role, which I thought was sweet. A couple paragraphs are devoted to the librarian’s perennial struggles [pre-apocalypse] to secure funding, to keep the populace’s attention in spite of modern distractions like tv and air conditioning!) Finally, I also really enjoyed Moon Shot (which I took with me to the eclipse on April 8); here's what I wrote about it in my reading spreadsheet: “The writing style wasn’t particularly phenomenal, yet I was still moved to tears several times while reading … about witnessing the beauty of space, the thrill of exploration, the astronauts’ successes and tragedies, and at the end, the simplicity and sentimentality and symbolism of the Apollo-Soyuz friendships. I can’t help but wonder what the fuck it is about billionaires … that they seemingly don’t become overwhelmed with the desire to save and protect our fragile planet after seeing it from space, a feeling many astronauts seem to have experienced.”

In general, I do most of my reading on the bus during my commutes to and from work, so I get in about 30-60 minutes per day of reading. But also this year I had several incidents of extensive sustained silent reading due to long waiting periods during travel – I read at least the first 100 pages of The Secret History while I was stuck overnight at Newark Airport in July; in August, I read almost all of Parable of the Talents on an Amtrak from Atlanta to Greensboro, then a chunk of Great Expectations on the way back. It was so nice to have that kind of IMMERSIVE, hours-long reading experience again! And especially with such richly detailed & descriptive stories! In 2025 I hope to be able to devote more time to slow, analog reading.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anne Sexton, The Complete Poems, with a foreword by Maxine Kumin, Houghton Mifflin Company Boston. 1999.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

A FOUNTAIN SEALED by Anne Douglas Sedgwick. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, [1907])

source

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#vintage books#edwardian books#book design

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Housewife

Some women marry houses. It's another kind of skin; it has a heart, a mouth, a liver and bowel movements. The walls are permanent and pink. See how she sits on her knees all day, faithfully washing herself down. Men enter by force, drawn back like Jonah into their fleshy mothers. A woman is her mother. That's the main thing.

Anne Sexton, All My Pretty Ones (1962), Selected Poems of Anne Sexton (Houghton Mifflin, 2000)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Truth the Dead Know

For my Mother, born March 1902, died March 1959 and my Father, born February 1900, died June 1959

Gone, I say and walk from church, refusing the stiff procession to the grave, letting the dead ride alone in the hearse. It is June. I am tired of being brave.

We drive to the Cape. I cultivate myself where the sun gutters from the sky, where the sea swings in like an iron gate and we touch. In another country people die.

My darling, the wind falls in like stones from the whitehearted water and when we touch we enter touch entirely. No one's alone. Men kill for this, or for as much.

And what of the dead? They lie without shoes in their stone boats. They are more like stone than the sea would be if it stopped. They refuse to be blessed, throat, eye and knucklebone.

From The Complete Poems by Anne Sexton, published by Houghton Mifflin Company. Copyright © 1981 by Linda Gray Sexton. Used with permission.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Neo-Griot

Kalamu ya Salaam's information blog

HISTORY: Indians, Slaves, and Mass Murder: The Hidden History

Indians, Slaves, and

Mass Murder:

The Hidden History

by Peter Nabokov

The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America by Andrés Reséndez Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 431 pp., $30.00

An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846–1873 by Benjamin Madley Yale University Press, 692 pp., $38.00

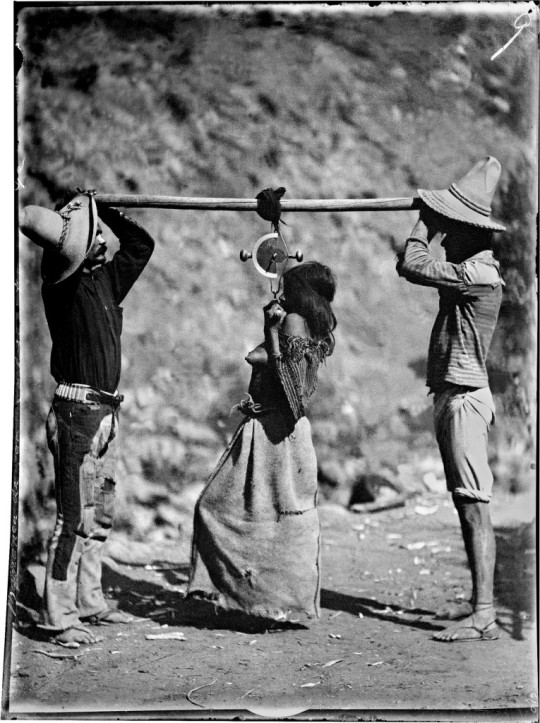

Carl Lumholtz: Tarahumara Woman Being Weighed, Barranca de San Carlos (Sinforosa), Chihuahua, 1892; from Among Unknown Tribes: Rediscovering the Photographs of Explorer Carl Lumholtz. The book includes essays by Bill Broyles, Ann Christine Eek, and others, and is published by the University of Texas Press.

1.

The European market in African slaves, which opened with a cargo of Mauritian blacks unloaded in Portugal in 1441, and the explorer Christopher Columbus, born in Genoa ten years later, were closely linked. The ensuing Age of Discovery, with its expansions of empires and exploitations of New World natural resources, was accompanied by the seizure and forced labor of human beings, starting with Native Americans.

Appraising that commercial opportunity came naturally to an entrepreneur like Columbus, as did his sponsors’ pressure on him to find precious metals and his religion’s contradictory concerns both to protect and convert heathens. On the day after Columbus landed in 1492 on an island in the present-day Bahamas and saw its Taíno islanders, he wrote that “with fifty men they could all be subjected and made to do all that one wished.” Soon the African trade was changing life in Spain; within another hundred years most urban families owned one or more black servants, over 7 percent of Seville was black, and a new social grouping of mixed-race mulattos joined the lower rungs of a color-coded social ladder.

Columbus liked the “affectionate and without malice” Arawakan-speaking Taíno natives. He found the men tall, handsome, and good farmers, the women comely, near naked, and apparently available. In exchange for glass beads, brass hawk bells, and silly red caps, the seamen received cotton thread, parrots, and food from native gardens. Fresh fish and fruits were abundant. Glints in the ornaments worn by natives promised gold, and they presumably knew where to find more. Aside from one flare-up, there were no serious hostilities. Columbus returned to Barcelona with six Taíno natives who were paraded as curiosities, not chattel, before King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella.

The following year, Columbus led seventeen ships that dropped 1,500 prospective settlers on Caribbean beaches. As they stayed on, relations with local Indians degenerated. What was soon imposed was “the other slavery” that the University of California, Davis, historian Andrés Reséndez discusses in his synthesis of the last half-century of scholarship on American Indian enslavement. First came the demand for miners to dig for gold. The easy-going Taínos were transformed into gold-panners working under Spanish overseers.

The Spaniards also exploited the forms of human bondage that already existed on the islands. The Caribs of the Lesser Antilles, a more aggressive tribe, regularly raided the Taínos, allegedly eating the men but keeping the women and children as retainers. A similar discrimination based on age and gender would prevail throughout the next four centuries of Indian-on-Indian servitude. As Bonnie Martin and James Brooks put it in their anthology, Linking the Histories of Slavery: North America and Its Borderlands:

North America was a vast, pulsing map of trading, raiding, and resettling. Whether the systems were pre- or postcontact indigenous, European colonial, or US national, they grew into complex cultural matrices in which the economic wealth and social power created using slavery proved indivisible. Indigenous and Euro-American slave systems evolved and innovated in response to each other.*

Taínos who resisted the Spanish were set upon by dogs, disemboweled by swords, burned at stakes, trampled by horses—atrocities “to which no chronicle could ever do justice,” wrote Friar Bartolomé de las Casas, a crusader for Indian rights, in 1542. Against the Caribs the Spaniards had a tougher time, fighting pitched battles but capturing hundreds of slaves as well. Columbus sailed home from his second voyage with over a thousand captives bound for slave auctions in Cádiz (many died en route, their bodies tossed overboard). He envisioned a future market for New World gold, spices, cotton, and “as many slaves as Their Majesties order to make, from among those who are idolators,” whose sales might underwrite subsequent expeditions.

Thus did the discoverer of the New World become its first transatlantic human trafficker—a sideline pursued by most New World conquistadors until, in the mid-seventeenth century, Spain officially opposed slavery. And Columbus’s vision of a “reverse middle passage” crumbled when Spanish customers preferred African domestics. Indians were more expensive to acquire, insufficiently docile, harder to train, unreliable over the years, and susceptible to homesickness, seasickness, and European diseases. Other obstacles included misgivings by the church and royal authorities, which may explain Columbus’s emphasis on “idolators” like the Caribs, whose status as “enemies” and cannibals made them more legally eligible for enslavement.

Indians suffered from overwork in the gold beds, as well as foreign pathogens against which they had no antibodies, and from famine as a result of overhunting and underfarming. Within two generations the native Caribbean population faced a “cataclysmic decline.” On the island of Hispaniola alone, of its estimated 300,000 indigenous population, only 11,000 Taínos remained alive by 1517. Within ten more years, six hundred or so villages were empty.

But even as the Caribbean was ethnically cleansed of its original inhabitants, a case of bad conscience struck Iberia. It had its origins in the ambivalence of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella over how to treat Indians. In the spring of 1495, only four days after the royals advised their bishop in charge of foreign affairs that slaves “would be more easily sold in Andalusia than in other parts,” they ordered a halt to all human enslavement until the church informed them “whether we can sell them or not.” Outrage was more overt in the polemics of Las Casas, who had emigrated to the islands in 1502. He had owned slaves and then renounced the practice in 1515. After taking his vows as a Dominican priest, he helped to push the antislavery New Laws of the Indies through the Spanish legal system in 1542.

Slaving interests used a succession of verbal strategies for justifying and retaining unfree Indian labor. As early as 1503 tribes designated as “cannibals” became fair game, as were Indian prisoners seized in “just wars.” Hereafter labeled esclavos de guerra (war slaves), their cheeks bore a branded “G.” Automatic servitude also awaited any hapless Indians, known as esclavos de rescate (ransomed slaves), whom Spanish slavers had freed from other Indians who had already enslaved them; the letter “R” was seared into their faces.

In 1502 Hispanola’s new governor, Nicolás de Ovando, made use of an old feudal practice for ensuring control over workers’ bodies. To retain native miners but check rampant cruelty, Ovando bestowed on prominent colonizers land grants (encomiendas) that included rights to tribute and labor from Indians already residing there. Although still vassals, they remained nominally free from “ownership.” They could reside in their own villages, were theoretically protected from sexual predation and secondary selling, and were supposed to receive religious instruction and token compensation of a gold peso a year—benefits that were often ignored. Over the next two centuries the encomienda system and other local forms of unfree labor were used to create a virtually enslaved Indian workforce throughout Mexico, Florida, the American Southwest, down the South American coast, and over to the Philippines.

The story of Native American enslavement told by Reséndez becomes confused by the convoluted interplay of indigenous and imported systems of human servitude. Despite his claim of uncovering “the other slavery,” when speaking of the forms of bondage imposed on Indians he fails to acknowledge that there was no monolithic institution akin to the “peculiar” transatlantic one that would become identified with the American South, which imported Africans auctioned as commodities. Even the distinction some scholars draw between such “slave societies” and “societies with slaves” (depending on whether slave labor was essential or not to the general economy) only partially applies to the highly complex, deeply local situations of enslaved American Indians. For these blended a dizzying variety of customary practices with colonial systems for maintaining a compulsory native workforce. If Reséndez is claiming to encompass the full tragedy of Indian slavery “across North America,” he does not distinguish among the different colonial systems of Indian servitude—enabled by Indian allies of the colonizers—that existed under English, French, and Dutch regimes.

During the seventeenth century, as some Spaniards continued to raise the question of the morality of slavery, silver mines opened in northern Mexico, and the demand for Indian manpower increased. This boom would require more workers than the Caribbean gold fields and last far longer. Now the physical effort turned from surface panning or shallow trenching to sinking shafts hundreds of feet into the ground. More profitable than gold, silver was also more grueling to extract. Miners dug, loaded, and hauled rocks in near darkness for days at a time. Around present-day Zacatecas, entire mountains were made of the gray-black ore.

To meet the growing labor demand, Spanish and Indian slaving expanded out of the American Southwest, sending Pueblo and Comanche slaves to the mines, and seizing slaves from the defiant Chichimec of northern Mexico during particularly violent campaigns between the 1540s and the 1580s. From the beginning of the sixteenth century to the first decade of the nineteenth, twelve times as much silver was extracted from over four hundred mines scattered throughout Mexico as was gold during the entire California Gold Rush.

At Parral, a silver-mining center in southern Chihuahua and in 1640 the largest town north of the Tropic of Cancer, over seven thousand workers descended into the shafts every day—most of them enslaved natives from as far off as New Mexico, which soon became “little more than a supply center for Parral.” After the state-directed system for forcibly drafting Indian labor for the Latin American silver mines, known as the mita, was instituted in 1573, it remained in operation for 250 years and drew an average of ten thousand Indians a year from over two hundred indigenous communities.

As Reséndez shifts his narrative to the Mexican mainland, however, one is prompted to ask another question of an author who claims to have “uncovered” the panoramic range of Indian slavery. Shouldn’t we know more of the history of those Indian-on-Indian slavery systems that Columbus witnessed and that became essential for delivering workers to Mexican mines, New Mexican households, or their own native villages? Throughout the pre-Columbian Americas, underage and female captives from intertribal warfare were routinely turned into domestic workers who performed menial tasks. Through recapture or ransom payment some were repatriated, while many remained indentured their entire lives. But a number were absorbed into their host settlement through forms of fictive kinship, such as ceremonial adoption or most commonly through intermarriage.

Among the eleventh-century mound-building Indian cultures of the Mississippi Bottoms, such war prisoners made up a serf-like underclass. This civilization collapsed in the thirteenth century and the succeeding tribes we know as Choctaw, Cherokee, Creek, and others perpetuated the practice of serfdom; Cherokee war parties added to each town’s stock of atsi nahsa’i, or “one who is owned.” The custom continued across indigenous America, with child-bearing women and prepubescent males generally preferred. Their husbands and fathers were more commonly killed. Reséndez hardly mentions the subsequent participation of those same tribes in the white man’s race-based “peculiar institution.” They bought and sold African-American slaves to work their Indian-owned plantations. Once the Civil War broke out there was a painfully divisive splitting of southern Indian nations into Confederate and Union allies.

As with Carib predation upon the Taíno, it was not uncommon for stronger tribes to focus on perennial victims. In the Southeast, the Chickasaw regularly took slaves from the Choctaw; in the Great Basin, the Utes stole women and children from the Paiute (and then traded them to Mormon households that were happy to pay for them); in California, the northeastern Modoc regularly preyed upon nearby Atsugewi, while the Colorado River–dwelling Mojave routinely raided the local Chemehuevi. These relationships between prey and predator might extend over generations. Only among the hierarchical social orders of the northwest coast, apparently, were slaves traditionally treated more like commodities, to be purchased, traded, or given as gifts.

Indirectly, the Spanish helped to instigate the next upsurge in human trafficking across the American West. Their horses—bred in northern New Mexico, then rustled or traded northward after the late seventeenth century—made possible an equestrian revolution across the plains. In short order the relationships between a few dozen Indian tribes shifted dramatically, as the pedestrian hunter-and-gatherer peoples were transformed by horses into fast-moving nomads who became dependent on buffalo and preyed on their neighbors. In white American popular culture the new-born horse cultures would be presented as the war bonnet–wearing, teepee-dwelling, war-whooping stereotypes of Wild West shows and movie screens. Among them were the Comanches of the southern plains and the Utes of the Great Basin borderlands.

By the mid-eighteenth century, the Comanche military machine had put a damper on Spanish expansionism. Their cavalry regiments of five hundred or more disciplined horsemen undertook eight-hundred-mile journeys northward as far as the Arkansas River and southward to within a few hundred miles of Mexico City. The slaves they plucked from Apaches, Pueblos, and Navajos became their prime currency in business deals with Mexicans, New Mexicans, and Americans. At impromptu auctions and established crossroads, Native American, Mexican, and Anglo slaves were being sold, some undergoing a succession of new masters. Until the US government conquered them, the Comanches held sway over a quarter-million square miles of the American and Mexican borderlands.

Reséndez argues for continuities in this inhuman traffic right down to the present day. But his abrupt transition to the present after the defeat of the Comanches only reinforces our sense that his effort has been overly ambitious and weakly conceived, as if achieving the promised synthesis for so complex and persistent a topic has simply (and understandably) overwhelmed him. His treatment of the multinational practices of Colonial-period slavery is spotty, and the ubiquitous traditions of native-on-native enslavement seem soft-pedaled.

Reséndez loosely estimates that between some 2.5 to five million Indians were trapped in this “other slavery,” in which overwork and physical abuse doubtlessly contributed to the drop of 90 percent in the North American Indian population between Columbus’s day and 1900. But somehow little of all that torment comes across vividly in The Other Slavery. We are told that Navajos called the 1860s, when their entire tribe was hounded for incarceration in southern New Mexico, “the Fearing Time.” Aside from that hint of the collective emotional impact from the victims’ side, we get few testimonies that reflect the anxiety and terror behind Reséndez’s many summaries of human suffering, tribal dislocations, furtive lives on the run, and birthrights lost forever.

A more convincing sense of the racial discrimination and hatred that bolstered and perpetuated the slavery systems discussed in Reséndez’s book comes from even a melodramatic film like John Ford’s The Searchers (1956), while the terrors of surviving in the late-eighteenth-century West amid roving bands of merciless slave raiders are better evoked in Cormac McCarthy’s Grand Guignol masterpiece Blood Meridian(1985). Reading Reséndez’s account one hopes in vain for something similar to Rebecca West’s quiet comment in Black Lamb and Grey Falcon (1941), her chronicle of Yugoslavian multiethnic animosities: “It is sometimes very hard to tell the difference between history and the smell of a skunk.”

2.

Indian slavery becomes a contributing factor in An American Genocide, the UCLAhistorian Benjamin Madley’s extensive argument that genocide is the only appropriate term for what happened to native peoples in north-central California between 1846 and 1873. For American Indians, slavery in the New World took many forms that persevered over four centuries while changing according to local conditions, global pressures, and maneuvers to evade abolitionist crusades. Genocide—the elimination of entire groups—might seem easier to evaluate. Yet which historical episodes of mass Indian murder qualify as genocide has become a matter of debate.

Madley shies away from the hyperbolic accusations of genocide or holocaust often made in simplistic discussions of American Indian history. The definition that he invokes with prosecutorial ferocity is the one produced by the United Nations Genocide Convention of 1948, which defines genocide as, first, demonstrating an intent to destroy, “in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group,” and, second, committing any of the following acts: killing members of a group; causing them serious bodily or mental harm; inflicting conditions that are intended to cause their destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures to prevent births within the group; and transferring children of the group to another group. Whereas the large unspecified “group” referred to in this post–World War II statement was, of course, defined by the Nazis, Madley’s is smaller and, even then, it is composed of many hundreds of indigenous units, each an autonomous, small-scale cultural world that was decimated or destroyed.

Madley has documented his charge of genocide by years of scrolling through local newspapers, histories, personal diaries, memoirs, and official letters and reports. These revealed what many indigenous groups endured at the hands of US military campaigns, state militia expeditions, impromptu small-town posses, and gold miners, as well as ordinary citizens who hunted natives on weekends. Most western historians and demographers could agree that genocidal behavior toward a North American Indian population occurred during the nineteenth century. But Madley has concentrated on the killing in California during the bloody years between 1846 and 1873.

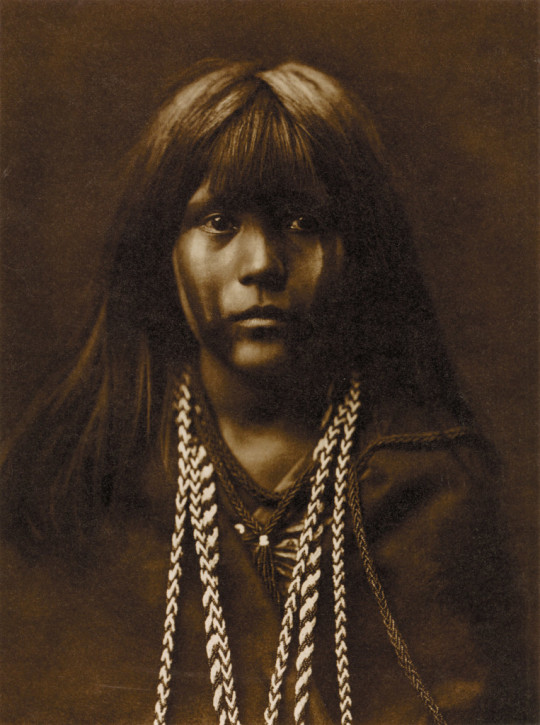

Edward S. Curtis: Mosa—Mohave, 1903/1907; from Edward S. Curtis: One Hundred Masterworks. The book is by Christopher Cardozo, with contributions by A. D. Coleman, Louise Erdrich, and others. It is published by Delmonico/Prestel and the Foundation for the Exhibition of Photography.

The factors that led to this American tragedy are worth recalling. Many Indian communities had already been defeated in their resistance to servitude during the Spanish Mission and Mexican Rancho years. The United States victory over Mexico in early 1848 opened the way to the last great American land rush. Until California became the nation’s thirty-first state in 1850, there were two years of lawlessness. The Anglo-American settlers whose wagons began rolling into the region carried anti-Indian attitudes imported from colonial times. The discovery of gold in early 1848 multiplied that immigration and aggressive settler colonialism. There was pervasive racism toward the state’s diverse and generally peaceful native population. They were denigrated as animal-like “Diggers”—a pejorative term based on their food-gathering customs. Political, military, journalistic, and civic leaders favored creating a de facto open season on its native peoples.

When the state’s first legislature convened, it passed a number of orders that, according to Madley, “largely shut Indians out of participation in and protection by the state legal system” and granted “impunity to those who attacked them.” The legislature funded, with $1.51 million, state vigilantism coupled with exhortations from top officials, including two state governors, to war against Native Americans. Near the beginning of this campaign, California’s first governor, Peter Burnett, pledged that “a war of extermination will continue to be waged…until the Indian race becomes extinct.”

At the time of first contact with whites, the native California population amounted to some 350,000, perhaps the densest concentration of Indians in the country. But they were divided into at least sixty major tribes that, in turn, were made up of scores of small, independent, autonomous villages that spoke upward of a hundred separate languages. After the epidemics, mission programs, land losses, and peonage of the Spanish period, about 150,000 Indians remained on the eve of the US takeover. By 1870 the number of California Indians had been cut to under 30,000, a population loss that would continue until it bottomed out at under 17,000 by the turn of the century.

When gold was struck near present-day Sacramento in January 1848, Indians were occupying some of the most desirable natural environments in North America. The size of these Indian groups ranged widely. The proximity of so many autonomous villages made bi- or even trilingualism not uncommon. But especially in the north-central region—with its abundant acorn groves, salmon-rich rivers, valleys plentiful in fruits, roots, and seeds, foothills teeming with game, plentiful marine life, wildfowl and associated plants along the sea coast and wetlands—their small, self-governing and self-sufficient villagers could thrive in their homelands. However, the combination of Spanish and American invasions would cost the Indians and their fragile ecologies dearly. Meadows bearing life-giving nutritious seeds and roots were put to the torch for conversion into agricultural fields and cattle pastures, streams were poisoned by the sludge from mining, and forests were cut for lumber.

To characterize these fairly self-contained worlds, the dean of California Indian studies, anthropologist Alfred L. Kroeber, coined the term “tribelet.” But when it came to describing the sufferings of these California tribelets during the Gold Rush, Kroeber wrote dismissively of their “little history of pitiful events,” which, as an ethnographer drawn to “millennial sweeps and grand contours,” he felt unable to comment upon.

That did not stop one of his colleagues, the anthropologist Robert Heizer, from doing so. Heizer’s revelatory They Were Only Diggers (1974), along with his other anthologies, compiled newspaper clippings and reports on the myriad killings and other brutalities experienced by the region’s Indians. Together with a state demographer, Sherburne Cooke, he began documenting the unpublicized story of the California Indian catastrophe. Now Benjamin Madley, building upon the ethnohistorical work of Heizer and Cooke, has delved more systematically into the outrages of the period.

His chronicle opens with accounts by Thomas Martin and Thomas Breckenridge, members of John C. Frémont’s early expedition, which invaded what was still Mexican-held territory. In April 1846, along the Sacramento River near the present-day city of Redding, Frémont’s troops encountered a large group of local Wintu Indians. With the command “to ask no quarter and to give none,” his troops encircled the Indians and began firing at everyone in sight. Breckenridge wrote: “Some escaped but as near as I could learn from those that were engaged in the butchery, I can’t call it anything else, there was from 120 to 150 Indians killed that day.” Martin estimated that “in less than 3 hours we had killed over 175 of them.” A third eyewitness account found by Madley raised that estimate to between six hundred and seven hundred dead on land, not counting those, possibly an additional three hundred, slaughtered in the river. “The Sacramento River Massacre,” he writes, may have been one of the least-reported mass killings in US history, and “was the prelude to hundreds of similar massacres.”

So begins Madley’s calm, somber indictment. One after another he describes the cultures and the histories of tribes that were victimized, and he profiles the victimizers. Many of the atrocities were committed not only by US soldiers and their auxiliaries but also by motley companies of militiamen that murdered young and old, male and female indiscriminately—and often with an undisguised glee that comes through in Madley’s abundant selection of quotes.

Rape was rampant, and natives were intentionally starved, tortured, and whipped. Under the new California Legislature’s Government and Protection of the Indians Act of 1850, any nonworking, publicly drunk, or orphaned and underage Indians could become commodities in an unfree labor system that was tantamount to slave auctions. The act’s impact on the young meant that ten years after its passage, thousands of California Indian children were serving as unpaid “apprentices” in white households.

For over a quarter-century, Madley shows how the region became a quilt of many killing fields. Of the estimated 80 percent decline in the California Indian population during these years, around 40 percent has been attributed to outright “extermination killings” alone. Yet each of these tribes and tribelets functioned as an independent cultural world. Each was knit together by strands of kinship and deep attachments to place, as well as oral traditions about both that were passed on from generation to generation. Strewn across California were not only human bodies, but entire worldviews.

At the start of the Gold Rush, the Yuki Indians who lived at the heart of the region had well over three thousand members; they were reduced to less than two hundred by its end. The same decline occurred among the Tolowa Indians to the northwest, while the Yahi people were practically wiped out altogether.

In the hateful rhetoric of many nineteenth-century military, religious, and bureaucratic hard-liners quoted by Madley, the word “extermination” was often used. Yet this outcome was considered no great tragedy for an entire people who were uniformly and irredeemably defined as savage and subhuman.

Madley’s nearly two hundred pages of appendices are the most complete incident-by-incident tally ever compiled of Indian lives lost during this terrible period. Asking for names would have been impossible; instead we get numbers of deceased and places where they perished—one or two with brains smashed on rocks on a particular day over here, thirty to a hundred shot to death and left floating in a river over there. This scrupulously detailed epilogue is the equivalent of a memorial wall that we are visiting for the first time.

#Indians#Slaves#Mass Murder:#The Hidden History#black lives matter#Black Indians#Neo-Griot#Kalamu ya Salaam#Black Global History

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy birthday darling I have no presents and fantasy cake but I hope I make you happy with everything I made like this edit right here with all of your pictures in it Shirley Jane Temple Black 1928-2014 April 23rd 1928-February 10th 2014 and special rest in peace to those who passed away Bishop Rance Allen, Conway Twitty, Loretta Lynn, Lisa Loring, Bob Saget, Betty White, Heather O'Rourke, Judith Barsi, baby Leroy, baby Peggy Montgomery, Peggy cartwright, Darla Jean Hood, Jean Darling, Peaches Jackson, Mary Ann Jackson, Dorothy DeBorba, Mary Kornman and Mildred Kornman, Kenny Rogers, Patsy Cline, Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky, Eazy-E, rest in peace Ana Ofelia Murguía December 31st 2023, Jim James Edward Jordan, Lucille Ricksen, Judy Garland, Margaret Hamilton and Terry and Pal, Eva Gabor, Geraldine Sue Page, Pat Buttram, Joe Flynn, Michael Gambon, Alan Rickman, Gene Wilder, Jack Albertson, Richard Belzer, Richard Harris, Bernard Fox, Raymond Burr, Perrette Pradier, Jeanette Nolan, Larry Clemmons, Bing Crosby, John Candy, John Heard, John Fiedler, Beate Hasenau, Billie Burke, Roberts Blossom, Billie Bird, Bill Erwin, Ralph Foody, Jack Haley, Ray Bolger, Bert Lahr, Frank Morgan, Jim Nabors and Frank Sutton, John Wayne, Clara Blandick,Charley Grapewin, Buddy Ebsen, Angelo Rossitto, Clarence Chesterfield Howerton, Bridgette Andersen, Dominique Dunne, Dana Plato, Robbie Coltrane, Lance Reddick, Betty Ann Bruno, Betty Tanner, Elizabeth Taylor, Helen McCrory, Ray Liotta and Tom Sizemore and Burt Reynolds, Zari Elmassian, Frank Cucksey, Vyacheslav Baranov, Vladimir Ferapontov, Carol Tevis, George Shephard Houghton, Irving S. Brecher, Richard Griffiths, Andy Griffith and Don Knotts, Joe Conley, Alan Arkin, Jerry Heller, Fred Willard, Mary Ellen Trainor, Morgan Woodward, Anna Lee and John Ingle, David Lewis, Ken Curtis, Ed Asner, James Caan, James Arness, Amanda Blake, Avicii, Jane Withers and Virginia Weidler, Milburn Stone, Natasha Richardson, Joanna Barnes, Cameron Boyce and Tyree Boyce, Cammack"Cammie"King, Denny Miller, Jane Adams, June Marlowe rest in heavenly peace to all of them actors and actresses this is Shirley Temple birthday edit of the year

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

6+cut undersleeves

We all seen Streatham and Houghton portraits. They have very specific undersleeves with 6 VISIBLE cuts and it’s not very prominent style in Tudor paintings, so I have wondered if based upon it, we could narrow the dating But the style is nowhere to be found. As if it didn’t exist at all. I have even started to consider that it is madeup. It isn’t.So let’s look at some more depictions of it.

Houghton:

Streatham:

Detail from Allegory of Tudor succesion, done in reign of Elizabeth I. It’s Mary. This is would be based upon Elizabeth’s idea how her sister looked like:

Imo it is done by possibly same painter as the one who made Streatham portrait(above). The similairities in the pearls, golden details, the hands...say that if not same painter, then very likely same workshop.

But how is Mary’s outfit different from Streatham’s?

Mainly, the use of cloth of gold instead of cloth of silver(or grey damask) and additional golden trims(embroidered in style popular among royalty only in 1540s and 1550s).. These wide trims were common in 2nd half of Edward’s reign and in Mary’s reign(though i am not sure if it isn’t bit overaxagerated here).

The undersleeves here appear to have narrower gaps between them than in Streatham portrait and there is more of them, and Mary has cuffs in style of ruff.

Imo it’s later than Streatham portrait, because usually the styles had tendencies to start simple and evolve to more elaborate. I have previously voiced my theory that Mary possibly reversed in fashion(at least temporarily) upon becoming Queen and tried to erase Edward’s reign even in fashion. Creating heck of confusion. Innitially as Queen she appears to be wearing 1546-1548 style(in 1553! or 1554), but later she returns more to true 1550s style(sort of combination). Here i think it is the later(because of the cuffs in style of ruffs, which she didn’t wear iniatially as Queen.)

There are more versions of this allegory and I keep finding them labelled differently each time, so I am confused about them

However when Mary’s image is flipped then the similarities are more obvious:

And here the cuffs don’t have usch narrow gap and it looks as if it could be exact same style of undersleeves.

It’s possible. Mary’s depictions after becoming Queen are where these undersleeves appear most:

Does it prove it is Mary? No! But it suggest it might be. She became the strongest candidate for the moment. But it is not conclusive that it is her.

Nor is it conclusive proof that such fashion was too late to be Parr. Because Mary as Queen worn undersleeves and forepart from cloth of gold of silver, which are in portrait of Parr by Master John. Mary reused these sumptous items for her own splendor.

And yes, both women have same girdle from royal collection, and have their gowns lined with pearls. Still its not solid proof it is a same woman.

Problem is that this style appeared way earlier than Mary’s reign.

Could be evolution of 3, 6, 9+cuts , starting in 1540:

(But shape of stays in Streatham portrait says it is after 1543, so fans of Catherine Howard have no luck this time.)

Could be continuation on style with mutiple cuts in 1530s-Details of Anne Boleyn as lady of Garter on left, Mary de Guise in c.1540 on right:

Presumably the 6+ cut style is after this, the spacing and placement of cuts is different. We cannot rule out coexisting styles, but i think them unlikely because of lack of depictions from the time.

And the cherry on top-this painting by Holbei is from 1526:

Hence my conclusion is that 6+ cut style by itself can be anywhere from 1520-1560. It does not help to narrow the dating Streatham portrait.

I hope you have enjoyed this.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Big City Greens: The Movie & Primos To Premiere On The Same Night On Summer

It seems that Disney is planning to premiere both Big City Greens: The Movie & Primos on the same summer night according to EIRD.

Makes sense, Primos is one of the many upcoming Disney Channel shows created by Big City Greens alumnis.

BTW Disney hasn't given any updates on Big City Greens: The Movie since it's announcement on January 2022 and hasn't announced a new Disney TVA series since June 2023 since "STUGO", Maybe we will get news on both on the TCA Winter Press Tour 2024, darn it i wish Disney attended Wondercon.

#Big City Greens#Big City Greens The Movie#Big City Greens: The Movie#Primos#Disney Primos#Chris Houghton#Shane Houghton#Anne O'Brian#Ariel Vracin-Harrell#Natasha Kline#Disney Channel#Disney Channel Original Movies#DCOMs#Disney+ Animated Hybrid Movies#Disney Plus Original Animated Hybrid Movies

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Love and a cough cannot be concealed. Even a small cough. Even a small love.

— Anne Sexton, from "Admonitions to a Special Person" in The Complete Poems" (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1981) (via @reginarosenfeld)

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books I've read in 2023

'Crying in H Mart' by Michelle Zauner

'The Tea Dragon Society' by K. O'Neill

'A Certain Hunger' by Chelsea G. Summers

'How to Break Up with Your Phone' by Catherine Price

'The Metamorphosis' by Franz Kafka

'Animals Eat Each Other' by Elle Nash

'Coming Out Autistic' edited by Steven Fraser

'The Very Secret Society of Irregular Witches' by Sangu Mandanna

'We Swim to the Shark' by Georgie Codd

'Passing' by Nella Larsen

'The Service' by Frankie Miren

'What I Want to Talk About: How Autistic Special Interests Shape a Life' by Pete Wharmby

'The Inland Sea' by Madeleine Watts

'Mating in Captivity: Reconciling the Erotic and the Domestic' by Esther Perel

'Let Them Eat Chaos' by Kae Tempest

'Introducing Existentialism' by Richard Appiganesi

'The Silence Project' by Carole Hailey

'Cursed Bunny' by Bora Chung

'Sunshine' by Melissa Lee-Houghton

'The Delicacy' by James Albon

'Are Prisons Obselete?' by Angela Y. Davis

'The Beginning of the World in the Middle of the Night' by Jen Campbell

'Square Eyes' by Luke Jones and Anna Mills

'Chess Queens: The True Story of a Chess Champion and the Greatest Female Players of All Time' by Jennifer Shahade

'Making Cocoa for Kingsley Amis' by Wendy Cope

'The Housekeeper and the Professor' by Yōko Ogawa

'The Artificial Silk Girl' by Irmgard Keun

'Because Internet: Understanding the New Rules of Language' by Gretchen McCulloch

'Esc & Ctrl' by Steve Hollyman

'The Doors of Perception' by Aldous Huxley

'Sedating Elaine' by Dawn Winter

'Different, Not Less: A Neurodivergent's Guide to Embracing Your True Self and Finding Your Happily Ever After' by Chloé Hayden

'The Appendix' by Liam Konemann

'Food Isn't Medicine: Challenge Nutrib*llocks & Escape the Diet Trap' by Dr Joshua Wolrich

'Didn't Nobody Give a Shit What Happened to Carlotta' by James Hannaham

'Lies We Sing to the Sea' by Sarah Underwood

'Julia and the Shark' by Kiran Millwood Hargrave with Tom de Freston

'Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?' by Lorrie Moore

'Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century' edited by Alice Wong

'This Is How You Lose the Time War' by Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone

'Small Bodies of Water' by Nina Mingya Powles

'The Cassandra Complex' by Holly Smale

'French Exit' by Patrick deWitt

'Sundial' by Catriona Ward

'Don't Hold My Head Down: In Search of Some Brilliant Fucking' by Lucy-Anne Holmes

'Girl, Woman, Other' by Bernardine Evaristo

'The Love Factor' (So Little Time #8) by Rosalind Noonan

'Paris: The Memoir' by Paris Hilton

'All Systems Red' (The Murderbot Diaries #1) by Martha Wells

'Intimations' by Zadie Smith

'Cultish: The Language of Fanaticism' by Amanda Montell

'Motherthing' by Ainslie Hogarth

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

College Football By State - Michigan.

FBS: Central Michigan Chippewas - Mount Pleasant, Michigan - They first played in 1896. They are in the Mid-American Conference (MAC).

Eastern Michigan Eagles - YpSilanti, Michigan - They first played in 1891. They are in the MAC.

Michigan Wolverines - Ann Arbor, Michigan - They first played in 1879. They are in the Big Ten.

Michigan State Spartans - East Lansing, Michigan - They first played in 1885. They are in the Big Ten.

Western Michigan Broncos - Kalamazoo, Michigan - They first played in 1905. They are n the MAC.

D2: Davenport University Panthers - Grand Rapids, Michigan - They are in the Great Lakes Intercollegiate Athletic Conference (GLIAC).

Ferris State University Bulldogs - Big Rapids, Michigan - They are in the GLIAC.

Grand Valley State University Lakers - Allendale, Michigan - They are in the GLIAC.

Hillsdale College Chargers - Hillsdale, Michigan - They are in the Great Midwest Athletic Conference (G-MAC).

Michigan Tech Huskies - Houghton, Michigan - They are in the GLIAC.

Northern Michigan University Wildcats - Marquette, Michigan - They are in the GLIAC.

Northwood University Timberwolves - Midland, Michigan - They are in the G-MAC.

Saginaw Valley State University Cardinals - University Center, Michigan - They are in the GLIAC.

Wayne State University Warriors - Detroit, Michigan - They are in the GLIAC.

D3: Adrian Bulldogs - Adrian, Michigan - They first played in 1892. They are in the Michigan Intercollegiate Athletic Association (MIAA).

Albion Britons - Albion, Michigan - They first played in 1984. They are in the MIAA.

Alma Scots - Alma, Michigan - They first played in 1894. They are in the MIAA.

Hope Flying Dutchmen - Holland, Michigan - They first played in 1902. They are in the MIAA.

Kalamazoo Hornets - Kalamazoo, Michigan - They first played in 1892. They are in the MIAA.

Olivet Comets - Olivet, Michigan - They first played in 1884. They are in the MIAA.

And for the first time in the series, NAIA: Concordia University (MI.) Cardinals - Ann Arbor, Michigan

Lawrence Technological University Blue Devils - Southfield, Michigan.

Madonna University Crusaders - Livonia, Michigan.

Siena Heights University Saints - Adrian, Michigan.

All four of them are in the Mid-States Football Association (MSFA).

Awards: Favorite Mascot - The Flying Dutchmen of Hope University. The Olivet Comets get an honorale mention. (I'm not picking Comets as my favorite mascot in back to back states.) The "Pack Hunters" Award - The Timberwolves of Northwood University. "King Of The Who?" Award - The Albion Britons. "Get Into The Groove" Award - The Madonna University Crusaders. The "Mustelids Are Assholes, But Cool" Award - The Michigan Wolverines.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review 5-9: John Green

This is a book review for the following books by John Green:

- The Fault in Our Stars (3.5/5)

- An Abundance of Katherines (3/5)

- Paper Towns (4/5)

- The Anthropocene Reviewed (10000000000000000000/5)

This is going to be an old review, because the last time I read any of these books was when I was in high school as a Freshman. I am now a 21 year old college senior, and was around for the 2016 Tumblr craze over TFiOS, and the status of it as a meme now.

I have only read Looking For Alaska once. I have read Paper Towns multiple times, and An Abundance of Katherines a few times. I have practically memorized TFiOS... Why? Because it was THE book of angst for 13 year old me.

I like John Green a lot. I like what he and Hank Green do for students, young people, and the community online. They are good people with informative videos and with interesting ideas. So here I am, reviewing John Green’s books from way back when. Please note* I haven’t read any of these books within the last 4 years besides the Anthropocene Reviewed. So this is more a review of the nostalgia and the pieces I can remember.

The Fault in Our Stars. There are faults with this book, but there are great parts too. This was the first book I read that had swearing and a realistic (or as realistic as you can get when it’s a straight white man narrating a teenage girls life) portrayal of teenagerhood. Is it pretentious as all heck? Yes. Are there moments where you want to strangle the main character? Yep. Are there moments when you want to strangle her boyfriend? Yes. Most definitely. BUT. This book was extremely important to me when I was younger, it was the first “adult” book I read. It tackled more than just fantasy novels or things like Amber Brown. It was a book that was about someone who was dying, but who was finding their life through it. It helped I was discovering this around the time of the Sherlock, Doctor Who, TFiOS, Tumblr obsession craze. It fueled my love for the story, and the movie was coming out. Unfortunately, I am a contrarian. My roommate loves to tell me so. So it got too popular and my love for TFiOS was squashed. I put it on a shelf and began to love Paper Towns more, but then the movie for that book came out. The Fault in Our Stars is a sucky book for someone who is going through terminal illness. It glorifies, romanticizes, and is pretentious about it all. The kiss in the Anne Frank house is so infuriating that that’s what I remember. I fail to see why Augustus is so loved by Hazel, because he is just a guy. Hit him with your car. (Chrissy, 2023). Okay, maybe don’t hit the guy with leg cancer with a car, but come on. He goes through such a down hill spiral, and it’s understandable why, but it’s really annoying to read. Even though he is in pain and is dying, so is Hazel. He doesn’t have to be a jerk to her. Isaac is a much cooler person. If I were Hazel, I’d have gone for Isaac.

The imagery and quotes that this book has? Worth reading it for. There are lovely phrases about this. I fear that John Green could be my version of Peter Van Houghton. I’m really glad that he didn’t end TFiOS with an incomplete sentence that would have been really annoying and on the nose. But I did find it surprising he chose not to. So good on him for not being cliche.

Perhaps one of the least well known John Green book out there, this one is one of the top books he’s written to me. I liked the way that the book is, with footnotes and science-y nerdy terms that I didn’t really understand when I was 13. I liked that the book really makes you feel like you’re on a summer road trip, it’s hot, it’s long, you’re bored, but there’s enough intrigue and potential for romance you get your hopes up. I like the idea of being obsessed with being a genius, I can relate to that feeling a lot. I think that writing wise, this was one of his worst ones. I really like this book though. I haven’t read a book like this and still haven’t since. I would read it again, but wouldn’t recommend it to people who are obsessed with Green’s other work and are used to that quality and precedent.

Paper Towns is a great book. It’s funny, it’s got a great ending chase scene, it was relevant to my life when I read it. I grew up idolizing people, thinking that they were special and more than just people. This book is about that concept and someone making someone into more than they are. I love the movie of this book and think that it’s a fair adaptation (Cara Delavigne is hella fine). I think that this movie and the book could have been as successful as TFiOS if people were interested in it and it had gained as much controversy. I love the idea of a manic pixie dream girl being tracked down by a nerd and his friends and then telling them it was not fair they see her as a manic pixie dream girl. Sometimes, girls are just girls. People are people. They aren’t your answers, they aren’t your solutions, they aren’t your soul mates. I think this message would be really relevant to any high schooler, simp, or fanboy out there. I think that this book is great. :)

This is how you do a collection of essays. This project John Green has done via podcast is so good. I cannot recommend it enough. I never thought I’d be crying in my car to someone talking about Jerzy Dudek, contemplating Tetris, or appreciating Piggly Wiggly’s origin story. I never thought someone wondering about the world could be so powerful. I think this is such an important podcast, because it’s not only teaching us cool information about niche things, it’s teaching us about humanity. It’s teaching us about our lives, our earth, our society, and our history. I find great value in this project and am so happy that I gave it a chance. It’s so comforting hearing hope and reassurance when looking at Gingko Trees or the start of the Penguins of Madagascar. No matter what essay, Green makes me feel safe and full of wonder. He makes me feel secure to find joy and power in the things around me, how the world used to be, how it is and how it could be. If you’re going to try out something of John Green’s, please try this.

How I rate books:

0 - Could not finish

Could not finish due to various reasons. Be it it’s too boring, or that it was highly offensive or poorly written.

1 - No.

Absolutely detested, will not read again, could not believe some people read this and enjoy it. What were they thinking?

2 - Eh.

Not my cup of tea, but I can see why someone would like this. Wouldn’t read again but not a complete waste of time.

3 - Huh.

Welp. This book is very mid tier. I’m okay that I read it, might read it again if I am bored or forget it. This is an okay read and I’m okay I read it.

4 - Hm.

Hm. I don’t know if I really like this book but it made me feel something. I liked it and would read it again, I don’t know when I’d read it again but I’d confidently tell someone about this book and recommend this book.

5 - WOW! I love this book. I am this book. Read this book. 1000000000000000000000000000000/5 - Self explanatory

If I give a book this rating, assume it is now my personality and I am going to force you to read it in front of me.

**All art is not made by me, it is a google search and not my art. If it is my art, I will say so. Assume all art is not mine. Ty**

#tfios#paper towns#abundance of katherines#looking for alaska#john green#book review#unpopularghostnoodlegivesthisarating

4 notes

·

View notes