#Ama Ata Aidoo

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ama Ata Aidoo, from The Plums Taylor Swift, from Anti-Hero

Vincent van Gogh, Sien with a cigar, sitting on the floor beside the fireplace

409 notes

·

View notes

Text

#photography#film african cinema#slow cinema#ama ata aidoo#certain winds from the south ghana#new york african film festival#ghana

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

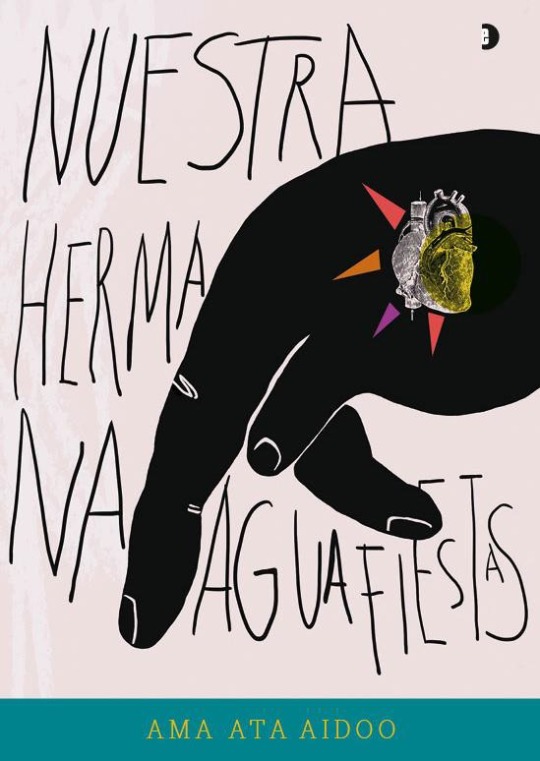

Nuestra hermana aguafiestas. Ama Ata Aidoo

Jueves 19 de octubre de 2023

Pasados los meses de verano y los calurosos días del veranillo de San Miguel, retomamos nuestro Club de Lectura “Con mucho gusto”, con sede en la biblioteca Reina Sofía, con algunos cambios que poco a poco se irán viendo.

Nuestra primera lectura en esta nueva edición es Nuestra Hermana Aguafiestas, de Christina Ama Ata Aidoo.

Nuestra Hermana Aguafiestas. O reflexiones desde una neurosis antioccidental, de Ama Ata Aidoo (Cambalache, 2018)

Pedro Sanz fue el encargado de acercar esta lectura a nuestro club. Dedicado a varias actividades sociales, entre las que destaca su colaboración con la educación de adultos en el barrio de Pilarica de Valladolid, eligió esta obra por su pertenencia a la Asociación Umoya, Comité de Solidaridad con el África Negra de Valladolid, surgida en 1990.

En su presentación señaló que Christina Ama Atta Aidoo (Ghana, 1942-2023), puso a la mujer el centro de su actividad profesional y literaria. Siempre quiso ser escritora; fue ministra de educación en su país y abandonó el cargo tras ocho meses por no ver clara la defensa de los derechos de las mujeres. Pertenece a la primera generación de mujeres escritoras africanas. Elemento común de su escritura es el hecho de que las mujeres que presenta son fuertes, toman las riendas de sus vidas y son responsables. Su obra expresa una conciencia política basada en la condición de las mujeres como metáfora de los oprimidos.

Nuestra Hermana Aguafiestas fue escrita en los años sesenta y publicada en 1977, y a pesar del tiempo transcurrido, su mensaje sigue siendo actual. La obra que comentamos es la única de la escritora traducida al español. En ella, el lector sigue los pasos de una joven ghanesa, Sissie, que viaja a Europa, concretamente a Alemania e Inglaterra. El choque cultural, educativo y principalmente personal marca el relato de hechos, acontecimientos, situaciones y sensaciones, relatados a veces de forma dispersa, a través de los cuales la protagonista expresa su inconformismo ante lo que ve y percibe.

En otro orden de cosas, llama la atención su estructura, ya que por la mezcla de estilos: narración, prosa poética, ensayo, libro de viaje, poesía, es difícil de catalogar genéricamente. Se trata de un texto híbrido en los que la voz de la protagonista organiza el conjunto. En las partes en verso o más poéticas se halla la verdadera posición de la protagonista, y en parte de la autora, aun cuando la obra no es autobiográfica.

Los participantes de ayer señalaron casi de forma unánime que el texto produce en primer lugar extrañeza por esa mezcla de géneros, y que se trata de una lectura exigente en la que cuesta entrar. Muchos coincidieron al señalar que la protagonista se muestra desde el comienzo enfadada, con una rabia y resentimiento que llaman la atención del lector. Es una mujer joven negra que sale de su país para conocer eso que llamamos primer mundo, y que le decepciona profundamente. Se produce en toda la obra una crítica a la situación en las que se hallan los africanos en Europa, con su deseo de establecerse lejos de sus países para procurar una vida mejor, y el rechazo de Sissie a la falta de compromiso con África y sus necesidades. Hay también, más o menos velado, un cuestionamiento a los postulados de la descolonización de los países africanos, en los que la autora no solo recalca el expolio de bienes materiales, sino también de los bienes humanos. Y, sobre todo, hay una visión feminista desde el afrocentrismo, que en palabras de la traductora: “Es un feminismo afrocéntrico e innegociable, que interpela por igual a las mujeres blancas y a los hombres negros”.

La charla de ayer concitó muchas dudas y muchas certezas. La negatividad de la protagonista no fue impedimento para señalar en qué situación estaba la mujer africana en los 60 y qué se esperaba de ella y de los hombres cuando tenían la oportunidad de estudiar en Europa; es de destacar el hecho de que Ama Ata Aidoo presenta a una mujer joven negra que muestra una actitud nada complaciente ante lo que Europa le ofrece; hay apuntes también acerca de la debilidad del primer mundo, en personajes como el de Marija en Alemania, que dieron pie a la reflexión acerca de la situación de soledad mostrado también en ciudadanos de los países europeos.

A destacar la admirable traducción llevada a cabo por Marta Sofía López, responsable también del prólogo que acompaña a la obra. Entre sus reflexiones es posible encontrar, condensado en pocas líneas, la poética que preside Nuestra Hermana Aguafiestas y a su autora:

En ningún momento la autora se deja deslumbrar por «los soles de las independencias», esa ola de optimismo sobre el futuro del continente africano que recorrió el mundo entero en la era de las descolonizaciones. Y mucho menos por el oropel del mundo occidental, especialmente de una Europa paternalista y falsamente benevolente que aparentaba (y sigue aparentando) apostar por el desarrollo, las políticas democráticas y el lavado de conciencia colectivo sobre la historia del esclavismo, el imperialismo, la colonización y la neocolonización.

En definitiva, buen comienzo de edición con un texto que nos hizo confrontar posturas, hablar del tema de la descolonización en África con los datos que sabiamente nos iba proporcionando Pedro, plantear asuntos de plena actualidad como es el feminismo o el racismo, y todo ello surgido a la luz de la lectura de un texto literario formalmente sorprendente y argumentalmente controvertido. ¿Qué mejor inicio?

#Literatura africana#Clubes universitarios de lectura#Con Mucho Gusto#Biblioteca Reina Sofía#Universidad de Valladolid#BURSofia#BUVa#Bibliotecas universitarias#Ama Ata Aidoo#África

0 notes

Text

A Revolutionary Classic Reborn – Ama Ata Aidoo’s Our Sister Killjoy Still Speaks Truth to Power - Book Review

Just finished Ama Ata Aidoo’s Our Sister Killjoy (Faber Editions 2025) via @NetGalley—this Ghanaian classic still speaks truth to power! A must-read for #BlackHistoryMonth on migration, feminism & identity. Read my thoughts here. 📖✨ #AfricanLiterature #NetGalley

Some books resonate across generations, their themes refusing to be silenced. Ama Ata Aidoo’s Our Sister Killjoy, first published in 1977 and now reissued by Faber Editions in 2025, is one such novel. A searing critique of European imperialism, alienation, and the disillusionment of African intellectuals abroad, this book remains as urgent and thought-provoking as ever. For those who revel in…

#African literature#Ama Ata Aidoo book review#black authors#black female authors#black narratives matter#book review#book reviews#decolonial narratives#Faber Editions 2025#feminist literature#Ghanaian author#immigrant experience#netgalley#Our Sister Killjoy review#popsugar

0 notes

Text

2023 in books: fiction edition

literary fiction published 2013-2023 (based on English translation)

The Employees by Olga Ravn (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Detransition Baby by Torrey Peters (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

When We Cease to Understand the World by Benjamín Labatut (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

There’s No Such Thing As an Easy Job by Kikuko Tsumura (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Human Acts by Han Kang (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Bunny by Mona Awad (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Frankissstein by Jeanette Winterson (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

All Your Children Scattered by Beata Umubyeyi Mairesse (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Mister N by Najwa Barakat (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Fever Dream by Samanta Schweblin (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Gideon the Ninth by Tamsyn Muir (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Brickmakers by Selva Almada (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

True Biz by Sara Nović (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Abyss by Pilar Quintana (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

The Meursault Investigation by Kamel Daoud (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Frankenstein in Baghdad by Ahmed Saadawi (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Spring Garden by Tomoka Shibasaki (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Rombo by Esther Kinsky (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Concerning My Daughter by Kim Hye-Jin (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

The House of Rust by Khadija Abdalla Bajaber (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Men without Women by Haruki Murakami (⭐⭐⭐)

The Sky Above the Roof by Natacha Appanah (⭐⭐⭐)

Sweet Bean Paste by Durian Sukegawa (⭐⭐⭐)

Luster by Raven Leilani (⭐⭐⭐)

Solo Dance by Li Kotomi (⭐⭐⭐)

Untold Night and Day by Bae Suah (⭐⭐⭐)

The Shadow King by Maaza Mengiste (⭐⭐⭐)

The Deep by Rivers Solomon (⭐⭐⭐)

Afterlives by Abdurazak Gurnah (⭐⭐⭐)

Wreck the Halls by Tessa Bailey

Indelicacy by Amina Cain (⭐⭐⭐)

Out of Love by Hazel Hayes (⭐⭐⭐)

Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi (⭐⭐⭐)

The Reactive by Masande Ntshanga (⭐⭐⭐)

The Houseguest: And Other Stories by Amparo Dávila (⭐⭐)

The Glutton by A.K. Blakemore (⭐⭐)

Homebodies by Tembe Denton-Hurst (⭐⭐)

Nervous System by Lina Meruane (⭐⭐)

Owlish by Dorothy Tse (⭐⭐)

The President and the Frog by Carolina de Robertis (⭐⭐)

The Magic of Discovery by Britt Andrews (⭐)

literary fiction published 1971-2012

House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

The Vampire Lestat by Anne Rice (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Corregidora by Gayl Jones (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Signs Preceding the End of the World by Yuri Herrera (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Changes: A Love Story by Ama Ata Aidoo (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Open City by Teju Cole (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

The Lover by Marguerite Duras (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Mild Vertigo by Mieko Kanai (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Abandon by Sangeeta Bandyopadhyay (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Toddler Hunting and Other Stories by Taeko Kōno (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Elena Knows by Claudia Piñeiro (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Ceremony by Leslie Marmon Silko (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Perestroika by Tony Kushner *a play (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Strange Weather in Tokyo by Hiromi Kawakami (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

By Night in Chile by Roberto Bolaño (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Drive Your Plow over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Three Strong Women by Marie NDiaye (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Kingdom Cons by Yuri Herrera (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Paradise Rot by Jenny Hval (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

A Mountain to the North, A Lake to the South, Paths to the West, a River to the East by Laszlo Krasznahorkai (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Interview with the Vampire by Anne Rice (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Queen Pokou by Véronique Tadjo (⭐⭐⭐)

The Private Lives of Trees by Alejandro Zambra (⭐⭐⭐)

The Hour of the Star by Clarice Lispector (⭐⭐⭐)

Sweet Days of Discipline by Fleur Jaeggy (⭐⭐⭐)

Mr. Potter by Jamaica Kincaid (⭐⭐⭐)

Bluebeard’s First Wife by Ha Seong-nan (⭐⭐⭐)

The Body Artist by Don DeLillo (⭐⭐⭐)

Glaciers by Alexis M. Smith (⭐⭐⭐)

Curtain by Agatha Christie (⭐⭐⭐)

The Iliac Crest by Cristina Rivera Garza (⭐⭐⭐)

My Name Is Red by Orhan Pamuk (⭐⭐⭐)

The Dovekeepers by Alice Hoffman (⭐⭐⭐)

Like Water for Chocolate by Laura Esquivel (⭐⭐⭐)

Rashomon and Seventeen Other Stories by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa (⭐⭐)

Coraline by Neil Gaiman (⭐⭐)

The End of the Moment We Had by Toshiki Okada (⭐⭐)

The Optimist’s Daughter by Eudora Welty (⭐)

literary fiction published start of time-1970

Catch-22 by Joseph Heller (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

🔁 The Stranger by Albert Camus (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

🔁 One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas by Machado de Assis (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Empty Wardrobes by Maria Judite de Carvalho (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Stoner by John Williams (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

The Chandelier by Clarice Lispector (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

An Apprenticeship, or the Book of Pleasures by Clarice Lispector (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

The Woman in the Dunes by Kōbō Abe (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Nightwood by Djuna Barnes (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Dracula by Bram Stoker (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Chess Story by Stefan Zweig (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Aura by Carlos Fuentes (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Fathers and Sons by Ivan Turgenev (⭐⭐⭐)

All Passion Spent by Vita Sackville-West (⭐⭐⭐)

The Hole by José Revueltas (⭐⭐⭐)

Baron Bagge by Alexander Lernet-Holenia (⭐⭐⭐)

Carmilla by J. Sheridan Le Fanu (⭐⭐)

Barabbas by Pär Lagerkvist (⭐)

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alredered Remembers Ghanaian dramatist and short story writer Christina Ama Ata Aidoo, on her birthday.

"For us Africans, literature must serve a purpose: to expose, embarrass, and fight corruption and authoritarianism. It is understandable why the African artist is utilitarian."

-Ama Ata Aidoo

1 note

·

View note

Text

For my own future reference, and for anyone else who wants it, a list of authors mentioned in the notes. (I cannot promise this is comprehensive, there are a lot of reblogs and I might have missed some.) I've included a link for each author, where possible I've tried to find one that leads you to their books, prioritising own websites/publishers, falling back on wikipedia otherwise.

If you find any mistakes in the links let me know and I'll edit. This post will be in two parts, because I literally broke tumblr with how many authors there were. I think it's about a hundred and fifty.

Faridah Àbíké-Íyímídé - speculative fiction

Marguerite Abouet - graphic novels

Elizabeth Acevedo - fiction, poetry

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie - fiction

Tomi Adeyemi - young adult fantasy

K Ancrum - speculative contemporary young adult

Lily Anderson - fiction

Ashley Antoinette - fiction

Ama Ata Aidoo - poetry, fiction, plays

Kemi Ashing Giwa - speculative fiction

Kalynn Bayron - young adult, fantasy

Malorie Blackman - childrens' books, young adult

Natasha Bowen - fantasy

Gwendolyn Brooks - poetry

Natasha Brown - fiction

NoViolet Bulawayo - fiction

Constance Burris - speculative fiction

CL Clark - fantasy, speculative fiction

Wahida Clark - urban fiction

Lucille Clifton - poetry, fiction

Alyssa Cole - romance, thrillers, graphic novels

Kamilah Cole - fiction

Claire Coleman - fiction, essays, poetry

Maryse Condé - fiction, non-fiction, plays

Emma Dabiri - non-fiction

Edwidge Danticat - fiction

Angela Davis - philosophy

Carolina Maria De Jesus - memoir

Hayley Dennings - fiction

Tracy Deonn - fiction

Nicky Drayden - speculative fiction

Tananarive Due - horror, comics

Camille Dungy - memoir, poetry

Esi Edugyan - fiction

Zetta Elliot - childrens' books, teen fiction, adult fiction

Bernardine Evaristo - fiction

Conceição Evaristo - fiction, non-fiction

Eve Ewing - poetry, fiction, non-fiction, comics

Radna Fabias - poetry

Namina Forna - young adult fantasy

Latoya Ruby Frazier - non-fiction

Stella Gaitano - fiction

Camryn Garrett - fiction, middle grade

Roxane Gay - fiction, non-fiction, comics

Nicole Glover - fantasy, speculative fiction

Nikki Giovanni - poetry, essays

Jewelle Gomez - fiction, plays

Annette Gordon-Reed - non-fiction (history)

Pumla Dineo Gqola - non-fiction

Deanna Grey - romance

Yaa Gyasi - fiction

Andrea Hairston - fiction

Lorraine Hansberry - plays

Saidiya Hartman - non-fiction, theory

Alexis Henderson - dark speculative fiction

Adriana Herrera - romance

Talia Hibbert - romance

bell hooks - fiction, non-fiction, poetry

Pauline Hopkins - fiction, non-fiction, plays

Nalo Hopkinson - speculative fiction

Jordan Ifueko - comics, fantasy, young adult

Samantha Irby - non-fiction

Justina Ireland - science fiction, fantasy, comics

Meka James - contemporary and erotic romance

Tiffany D Jackson - young adult

Beverly Jenkins - romance

Alaya Dawn Johnson - speculative fiction

Micaiah Johnson - science fiction

Mariame Kaba - non-fiction

Petals Kalulé - fiction, poetry [Petals is noted as using she/they, I'm not 100% sure of their gender identity and past a certain point it feels weird to investigate too much]

Mikki Kendall - fiction, non-fiction

Jamaica Kincaid - fiction, non-fiction

Zaire Krieger - poetry

Nella Larsen - fiction

Karmen Lee - romance

Kirsten R. Lee - young adult

Margot Lee Shetterly - non-fiction

Audre Lourde - poetry, non-fiction

hello fellow non-Black tumblr users. welcome to my saw trap. if you'd like to leave, please name one (1) Black woman author who is not Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison, bell hooks, Octavia Butler, or N.K. Jemisin. bonus points if she's published a book in the last five years.

#black women authors#list#long post#thank you to everyone who has their own website#made my life much easier#unless there was a clear genre label I've stuck very generically to fiction and non-fiction#mostly so I don't have to navigate the difference between fiction and literary fiction#this list is a comical mix of some truly less well known authors#huge genre-defining writers#and some of The Most Important People in Literature#but anyone I found in the tags got included regardless#a fun side effect of compiling this list was getting to read/write a lot of beautiful names and look at a lot of beautiful people#Some of these authors I think “surely everyone in the world knows who this is”#but the whole point of the post is No#I only used goodreads in an absolute emergency#because I hate amazon

25K notes

·

View notes

Text

Dilemma of a Ghost brings cultural tensions to life

Dilemma of a Ghost brings cultural tensions to life THE National Theatre in Accra hosted a captivating production of Ama Ata Aidoo’s thought-provoking play, Dilemma of a Ghost from Friday, June 6 to Sunday, June 8. Playwright and director, Fiifi Coleman and his Fiifi Coleman Production team creatively brought the story to life, exploring themes of cultural identity, tradition and…

0 notes

Text

i have read and read and and read and i have seen it in everything.

Nightwood, Djuna Barnes

Sam, Allegra Goodwin

Pizza Girl, Jean Kyoung Frazier

Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone, James Baldwin

Scaffolding, Lauren Elkin

Swimming in the Dark, Tomasz Jedrowski

Greta and Valdin, Rebecca K Reilly

Land of Milk and Honey, C Pam Zhang

Our Sister Killjoy, Ama Ata Aidoo

Model Home, Rivers Solomon

They're Going to Love You, Meg Howers

1 note

·

View note

Text

So there was a great deal of hand-holding, wet-kissing along ancient cobbled corridors. Pensive stares at the silvery eddies of the river.

—Ama Ata Aidoo, Our Sister Killjoy (1977, p.41)

About these American students studying abroad. We wonder how to feel about this??

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

some days

windy days

windy days

#photographies#cinema#tamale#eric gyamfi#Ama ata aidoo#certain winds from the south#ghana#scca tamale

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time by itself means nothing, no matter how fast it moves, unless we give it something to carry for us; something we value. Because it is such a precious vehicle, is time. - Ama Ataa Aidoo

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

90 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ama Ata Aidoo, who has died aged 81, was one of Africa’s most influential writers. Her plays, short stories, novels and essays explored the experiences of women in contemporary Africa, both rural and urban – women who are remarkable for their spirit, humour and resilience.

Aidoo’s play The Dilemma of a Ghost, first staged in 1964 at the Ghana Drama Studio when she was 22, was issued by Longman in 1965, making her the first published female African dramatist. This play contrasts a young African- American wife’s idealised concept of “Mother Africa” with the reality of her Ghanaian husband’s African mother’s traditions and expectations, often conflicting with the values embraced by a younger western-educated generation.

Like her second play, Anowa (1969), The Dilemma of a Ghost draws on both African and western performance traditions. In these plays and many of her short stories, Aidoo created an Africanised form of English for her characters, drawing on her native Akan idioms and sentence structures.

While her first play examines cultural conflicts in contemporary Ghana, during the optimism created by Kwame Nkrumah’s success in achieving independence, Anowa, written after the 1966 military coup that deposed Nkrumah amid accusations of corruption, reflects on Ghanaian history and the complicity of African chiefs with slavery. In the face of political dereliction, the play calls for a shift away from materialism and self-interest.

However, it is Aidoo’s fiction that has reached a worldwide audience. Her first volume of short stories, No Sweetness Here, was published in 1971. Many of the stories were written to be read on radio, with listeners as well as readers in mind, combining traditional oral storytelling, and communal participation, with European reader-oriented narrative techniques. They also showed how western technology can be put to the service of African culture rather than replacing or subduing it.

The use of oral traditions also allowed Aidoo to give a voice to women, in a context where female writers have been marginalised, while the concentration on dialogue, rather than exterior description, places the emphasis on women’s subjectivities, emotions and thoughts, rather than their appearance.

The title of Aidoo’s first novel, Our Sister Killjoy: Or Reflections from a Black-eyed Squint (1977), conveys the narrator’s wry self-deprecating humour, together with her awareness of differences in perception. Recounting the experience of a young Ghanaian woman who spends several months in Germany – “the heart of whiteness” – and with two male characters both called Adolf, the novel is in part a reversal of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

Indeed there is a literal heart of darkness in the novel when a group of Africans debate the ethics of Christiaan Barnard’s transplant of the heart of an African man. Aidoo uses a variety of narrative techniques in the novel, contrasting “knowledge gained then” and “knowledge gained since”, interspersing prose with fragments of verse, while questioning the usefulness of the English language to express African experience:

A common heritage. A Dubious bargain that left us Plundered of Our gold Our tongue Our life – while our Dead fingers clutch English …

Together with Aidoo’s second novel, Changes: A Love Story, which won the Commonwealth Writers’ prize in 1992, Our Sister Killjoy appears frequently in university courses on postcolonial and women’s writing. Aidoo’s 1985 collection of poetry, Someone Talking to Sometime, was awarded the Nelson Mandela prize for poetry. A second volume of poetry, An Angry Letter in January, appeared in 1992. She also published two more volumes of short stories, The Girl Who Can and Other Stories (1997) and Diplomatic Pounds and Other Stories (2012), as well as books for children.

Christine Ama Ata Aidoo was born, with a twin brother, Kwame Ata, at Abeadzi Kyiakor, near Saltpond in central Ghana (at that time known as the Gold Coast), the daughter of Maame Abasema and Nana Yaw Fama. Her father was chief of Abeadzi Kyiakor, and she belonged to Fante royalty. He founded the first school in Saltpond, and ensured that both his children received a good education there. Aidoo later spoke of the importance of the village storyteller, around whom the villagers would gather in the evenings.

From 1957, the year that Ghana became the first independent African nation, she attended Wesley girls’ senior high school in the city of Cape Coast. There she became aware of Ghana’s connection with the history of slave trading, embodied in the Cape Coast “castle” where captured slaves were held before being shipped to Europe and the Americas.

In 1961 she enrolled at the University of Ghana to study English, and also began writing seriously. The following year she was selected by a panel including Chinua Achebe, Langston Hughes, and Wole Soyinka to attend a writing workshop in Ibadan, Nigeria. She forced her way into the Nigerian Broadcasting office in order to meet Achebe, who was then head of external broadcasting, breathlessly announcing to him that she had “indeed arrived at the shrine”.

After graduation, Aidoo taught at universities in Africa and the US. She was appointed Ghanaian minister for education in 1982 after Jerry Rawlings gained power in a military coup, but in 1983 resigned and moved to Zimbabwe, where she worked for the Zimbabwe Ministry for Education. When she returned to Ghana in 1999, she and her daughter Kinna Likamanni established the Mbaasem Foundation, which sought “to support the development and sustainability of African women writers and their artistic output”.

Throughout her life, Aidoo saw her writing and other activities as part of her endeavour to help Africans recover from the consequences of colonialism.

In an interview in 1987 she declared: “I wish of course that Africa would be free and strong and organised and constructive, etc ... That is basic to my commitment as a writer … I keep seeing different dimensions of it, different interpretations coming through my writing.”

She is survived by her daughter.

🔔 Ama Ata Aidoo, writer and educator, born 23 March 1942; died 31 May 2023

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our Sister Killjoy; Ama Ata Aidoo

#quotes#extracts#ama ata aidoo#book quotations#postcolonialism#postcolonial literature#postcolonial theory#neocolonialism#literature#oppressor#colonialism

23 notes

·

View notes