#Alyssa Logie

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Hiii can we have a headmate based on this moodboard? :3

https://i.postimg.cc/RC29VvYw/IMG-4750.jpg

Well, we’ll try our absolute best, kitten!! Enjoy! =^w^=

Name: Karoline, Rhythm, Widget, Diana

Age: 16-23

Gender: Transmasc, Tumblrcringeic, Quirkycringic

Pronouns: They/them, Cringe/cringe’s, XD/XD’s

Sexuality: Asexual, Omnisexual (fem pref)

Species: Human

Ethnicity: African American

Source: N/A

Roles: Hyperfixation holder, Stim holder

CisIDs: cisAFAB, cisHuman, cisBlack, cisDarkSkin, cisADHD, cisAutistic, cisDyslexic

TransIDS: transSparklyBlood, transBPD, transChronicPain

Paraphiles: Somnophilia, AutoGratiophilia

Other Labels: Trans Man, Polyamorous, Furry, Proship

Personality: Silly, Kind, Generous, Blunt, Outgoing, Loving

Picrews Used: 1

Faceclaims:

A-paw-logies if this wasn’t what you were going fur. TwT

Feel free to change whate-fur you’d like! :P

- Mod Alyssa

#🎱 ; wiley’s disciples#🐈 ; mod alyssa#build a headmate#headmate template#build an alter#alter packs#willogenic#endogenic#tulpamancy#traumagenic#proship please interact#proship friendly#all plurals welcome#radqueer safe#radq interact#paraphiles please interact#pro paraphile

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

logie sargesnt version of logan paul’s the fall of jake paul to get back at alex. george is alyssa violet

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kween Kong previews Drag Race Global All Stars entrance look

New Post has been published on https://qnews.com.au/kween-kong-previews-drag-race-global-all-stars-entrance-look/

Kween Kong previews Drag Race Global All Stars entrance look

RuPaul’s Drag Race Global All Stars starts tonight, and Aussie hopeful Kween Kong has given a preview of her entrance look early.

The new international spinoff of the show premieres this evening (August 16), streaming in Australia on Stan.

Twelve queens from around the globe will compete for the title “Queen of the Mothertucking World” in the new series.

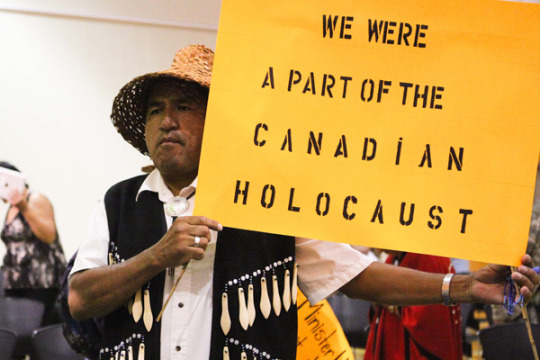

“Category is: ALWAYS WAS AND ALWAYS WILL BE,” Kween wrote.

“My first impression on the [Global All Stars] stage was my first opportunity to be the representation of ALL of Down Under.

“As the first POC girlie to rep our countries, I walked into this game knowing what needed to be done.

“At the time of filming, we were going through the referendum here in Australia. My icon @thecostumecreator knew we had a responsibility to wear the Aboriginal flag unapologetically but in a way that made a statement to the ridiculousness of “the Voice”.

“We incorporated elements of the New Zealand and Australian Flags and showcased custom jewels by @maineandmara with my family crest – the manu on it. THIS IS DOWN UNDER DRAG!”

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Kween Kong (@kweenkongofficial)

Kween added, “I hope the world is ready because you are going to see the version of Down Under drag that has never had a platform like this.

“It’s the world’s biggest stage and I’m going to be bringing you Oceanic Excellence weekly boo boo. Be ready!!”

Kween Kong up against Alyssa Edwards on Global All Stars

Kween Kong was runner-up on season two of RuPaul’s Drag Race Down Under.

Now she and US Drag Race icon Alyssa Edwards are going head-to-head on Global All Stars for the $200,000 grand prize and a spot in “the international pavilion at the Drag Race Hall of Fame”.

Global All Stars also brings back Drag Race Belgique’s star Athena Likis, Drag Race Philippines’ Eva Le Queen, Drag Race Mexico‘s Gala Varo, RuPaul’s Drag Race UK’s Kitty Scott Claus, and Drag Race Brazil’s Miranda Lebrão.

The lineup is rounded out by Drag Race Italia’s Nehellenia, Drag Race Canada’s Pythia, Drag Race France’s Soa de Muse, Swiss queen Tessa Testicle from Drag Race Germany and Drag Race Sweden’s Vanity Vain.

More on Kween and Drag Race:

Kween Kong gets Logie nomination for Drag Race Down Under

Ru-vealed: Here’s the queens set for Drag Race Down Under season 4

Rhys Nicholson on how Ru’s exit changed Drag Race Down Under

Rhys Nicholson on ‘grim’ Drag Race Down Under we almost saw

Kween Kong and Art Simone share Drag Race Down Under advice

For the latest LGBTIQA+ Sister Girl and Brother Boy news, entertainment, community stories in Australia, visit qnews.com.au. Check out our latest magazines or find us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

0 notes

Text

Rethinking Reconciliation and the Desire to Heal: Decolonizing Indigenous Healing, Conciliation, and Aesthetic Action in Canada

By: Alyssa Logie, M.A.

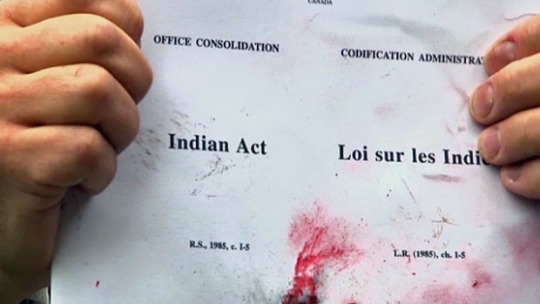

In December 2015, the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada released its final report including 94 “Calls to Action” urging all levels of Canadian government to contribute to the project of reconciliation. In 2015 Prime Minister Justin Trudeau instructed the Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs to officially implement these calls. As such, the Canadian government agreed to embark on the journey of reconciliation. According to the TRC, “reconciliation” is about “establishing and maintaining a mutually respectful relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples in this country” (A Knock on the Door 142). While this goal may seem advantageous and has had positive impacts as a response to the harms caused by Canada’s Indian Residential School System and the ongoing traumas of colonization, it is necessary to reflect upon the underlying sentiments that underpin the Canadian Government’s desire to participate in reconciliation. As this paper will highlight, many Indigenous and non-Indigenous people assert that the Government of Canada is pushing the discourse and project of reconciliation as an extension of the colonial project itself. In order to unpack how this may be, this paper pays particular attention to the Western implications of “healing” that underpin the TRC’s tenets of reconciliation. The push for “healing” as it is defined by the TRC and the Government of Canada ultimately places the responsibility of achieving reconciliation via a Western framework on the shoulders of those who already suffer at the hands of colonization and, as a result, silences Indigenous folk in order to further the Canadian government’s exploitation of Indigenous bodies and land.

This paper will first unpack how the TRC and the Government of Canada make particular use of the Western notion of healing as a necessity for reconciliation. Following this analysis of Western notions of healing within the TRC, I will unpack Indigenous notions of healing. This consideration of Indigenous notions of healing will further emphasize the colonial nature of the push for healing within the TRC’s hearings and final documents. After a consideration of Indigenous notions of healing, I will turn to Indigenous artists who are enacting “aesthetic action” in order to counter the Western notions of healing that permeate the reconciliation/colonization project in the hopes of rethinking what reconciliation really means in Canada.

The TRC’s Focus on “Healing” Indigenous Wounds and the Need for Conciliation

As stated by Métis scholar and artist David Garneau, “the sanctioned performance of Reconciliation [on behalf of the TRC and the Government of Canada] is foundationally distorted” (Garneau 23). Garneau reminds us that testimony produced for the TRC is “constrained by non-Indigenous narratives of healing and closure” (Garneau 23). In this way, the TRC hearings were part of a “theatre of national Reconciliation” (29). Although Garneau does acknowledge that survivors who shared their stories during the TRC hearings did so for a number of productive reasons (to bear witness, to speak the truth), he insists that we must also consider the peculiar “display mechanisms” these survivors and their testimonies became “caught up in” (30). Although the act of sharing testimony can and has had positive outcomes for survivors and their communities, and can and has contributed to the general understanding of Canada’s colonial past and present, we must remain critical of the underlying motivations for these testimonial acts to take place. Garneau looks at the TRC’s “Our Mandate” page to get a sense of what this motivation may be. The first line of the mandate reads: “There is an emerging and compelling desire to put the events of the past behind us so that we can work towards a stronger and healthier future” (TRC.ca). Whose desire is this? If it is the Government’s colonial desire, then the process of sharing testimonies at TRC hearings is nothing more than a “continuation of the settlement narrative” (Garneau 31). According to Garneau, “the present ‘colonial’ desire is to ‘put the events of the past behind us’ and reconcile Indigenous people with this narrative” (31). In this way, Reconciliation as it is conceived of and understood by the government is nothing more than a mutation of the colonial project. Following this logic, we can see how the TRC and ultimately the Government of Canada make use of Western understandings of healing instead of turning to Indigenous notions of healing. This is problematic, as it proposes a colonial answer to a supposedly de-colonial project.

Photo from: www.trc.ca

Garneau asserts that the notion of “reconciliation” as used by the TRC and the Government of Canada has its roots in Western, particularly Catholic, traditions. Garneau explains how the process of reconciliation assumes that communities and individuals can only be healed “by telling a secret to those in charge,” much like the Catholic practice of confession (33). This is problematic; as Catholic institutions are highly responsible for the traumas experienced at residential schools across Canada. To enforce a Catholic-inspired notion of reconciliation and salvation upon survivors of such traumas is entirely cruel and counter-productive. Additionally, the emphasis on the “spectacle of individual accounts (confessions) and healing narratives (forgiveness and penance)” is inherently colonial, as the ultimate goal is for survivors to heal, forget, and move on. According to Nehiyaw writer and community helper Suzanne Methot, the push on behalf of the TRC and the Canadian Government for Indigenous peoples to move on after sharing their stories of trauma is inherently motivated by the desire to mold Indigenous peoples into passive subjects, ultimately silencing the so-called “indigenous problem” of today (Methot). By rejecting Indigenous ways of knowing, “colonial systems and structures control the nature of the debate and contain it within settler-colonial parameters. This creates yet another opportunity for the colonizer to effect control upon Indigenous peoples” (Methot 205). Essentially, if Indigenous peoples “heal” according to Western notions of “healing”, they will stop complaining about the past and they—as well as their land—become easier to exploit in the interest of settler-colonial capitalist gain.

Suzanne Methot further explains how Western traditions of “talk therapy” have their limitations in serving Indigenous peoples. Methot describes these limitations:

The European focus on talking as a form of therapy has its roots in the writing of Rene Descartes and reflects his belief that “I think, therefore I am.” The resulting Cartesian dualism—wherein the mind is separated from the natural world—does not reflect Indigenous ideas on healing or wellness (Methot 233).

If reconciliation is predicated upon Western notions of healing that are incompatible with Indigenous knowledge systems, what other means can be used to genuinely take up the trauma of the IRS that do not fall into the historical pattern of colonialism? For Garneau, and other scholars such as David McDonald, the notion of “conciliation” can help to decolonize the process of truly healing and making reparations for Canada’s genocidal past, as conciliation is an “ongoing process, a seeking rather than the restoration of an imagined agreement” (Garneau 31)1. For Garneau, the reconciliation narrative should be “recast as a continued struggle for conciliation rather than the restoration of something lost (that never quite was)” (32). For conciliation to be possible, Indigenous sovereignties pre-contact must be acknowledged and upheld; Indigenous worldviews must be held up to the same degree as Western worldviews—this especially applies to Indigenous notions of healing that assume a continuous, never ending reflection on traumas of the past. Cree artist, poet and oral historian explains how the nêhiyawak (Cree) word used in reference to the residential school experience is ê-kiskakwêyehk, which means ‘we wear it’” (34). In this way, a wound is not something that goes away after a healing process—it is a scar that is never fully healed or forgotten, that influences the life of a people forever.

Indigenous Notions of Healing: A Pathway Towards Conciliation

After unpacking the Western-colonial desires that underpin the TRC’s and Government of Canada’s push for the healing of Indigenous peoples, it becomes necessary to turn to Indigenous notions of healing that can and must be used in the process of conciliation. In 1998, the Aboriginal Healing Foundation (AHF) was established in Ottawa, Ontario as an Indigenous managed, non-profit corporation with a mandate to “support the development of sustainable healing processes related to the legacy of Canada’s residential school system” (Archibald 1). During its operation, AHF received $515 million in funding from the Government of Canada that was used to create and support hundreds of Indigenous healing programs, and centers across the country (AHF.ca). As such, the AHF became the spearhead in organizing and ensuring funding for Indigenous healing initiatives across Canada. Before funding for the Foundation was cut by Stephen Harper’s conservative government in 2010 leading to its closure in 2014, the AHF provided hundreds of community-based Indigenous-centered healing initiatives for Indigenous folks in Canada, and published numerous reports and resources on this history and legacy of colonization in Canada (Archibald 2006). The AHF’s Final Report indicates that out of fourteen different forms of healing activities offered by initiatives funded by the AHF, Western therapies were the least effective in treating trauma and intergenerational trauma (2006, 37). Across the board, Indigenous-centered initiatives proved to be the more effective, with elder interactions, ceremony, one-to-one counselling and healing talking circles, and traditional medicine being the most popular and effective of all (37).

In the third volume of the AHF’s Final Report the term “promising healing practices” is used to define “models, approaches, techniques and initiatives that are based on Aboriginal experiences; that feel right to Survivors and their families; and that result in positive changes in people’s lives” (Archibald 2006, 7). These Indigenous-centered practices address what the AHF refers to as the “three pillars of healing” Indigenous trauma: reclaiming history, cultural interventions, and therapeutic healing (18). As opposed to a Western-oriented notion of healing, this definition includes the necessity of not only individual therapeutic interventions, but also a more holistic process involving the re-establishment of “a spiritual connection with the land using traditional teachings, values and practices” enforcing the “regaining of cultural identity, personal enlightenment and wellness that prepares residents for better reintegration back into their communities” (25). Essentially, the individual can only be healed alongside the reclamation of collective history, land and culture—all essential components to Indigenous healing that Western individual-based approaches ignore. According to a report prepared by Linda Archibald for the AHF, “the central lesson learned about promising healing practices is the immense value and efficacy of incorporating history and culture into holistic programs based on Indigenous values and worldviews” (52).

Image from: https://www.fnha.ca/what-we-do/traditional-healing

It is also crucial to remember that not all Indigenous notions of healing are uniform, and not all Indigenous peoples respond to the same healing practices in the same way. According to a report prepared by James B. Waldram for the AHF:

What clearly emerges from our research is the importance of flexibility and eclecticism in the development of treatment models. There is no singular Aboriginal client, as there is no singular Aboriginal individual. Some clients are very firmly entrenched in Aboriginal cultural experiences; others, however, have had extensive experience with the broader, non-Aboriginal influences of mainstream Canada. One legacy of the residential school and substitute care systems for Aboriginal people has been the lack of Aboriginal cultural experiences for many. These individuals are not culture-less, as many popular accounts of Aboriginal experience might suggest; rather, they simply have had little or no experience in an Aboriginal cultural milieu, especially during initial developmental stages (Waldram 2008, 4).

In this way, Waldram reminds us to refrain from utilizing Pan-Indigenous language when referring to processes of healing and conciliation. Additionally, according to Linda Archibald:

While adaptations and sharing of Indigenous practices take place across cultures, an increased resistance to viewing Aboriginal people as having a homogeneous set of traditions and practices is evident. At a global level, efforts are required to maintain and support the cultural diversity that currently exists. At the community level, there is some evidence that culturally-appropriate healing interventions are most effective when rooted in local practices, languages and traditions (Archibald 2006, 50).

With Waldram and Archibald’s assertions in mind, what specific Indigenous healing practices have been successfully used in the past, and can be used moving forward, in the process of conciliation?

The process of reconnecting with community, culture and land are three fundamental tenets of Indigenous healing. According to Suzanne Methot, connecting to the natural world a “transformative force, one that is key to healing and change” across all Indigenous peoples (Methot 239). Additionally, Methot cites “recreating the structures of belonging” as another key aspect to Indigenous healing. By “structures of belonging,” Methot is referring to the return of Indigenous peoples to their own communities and cultures. To support Methot’s assertion, in 1997 the Assembly of First Nations “identified the following common strengths among the projects it reviewed in a paper on successful Indigenous health programs in Canada, the United States and Australia: projects tend to be tradition-based and values-based; interventions focus on the entire family; links are made between spirituality and therapy; there is an intimate knowledge of the tribal community and a drawing together of traditions; projects respond to the needs of the community; and the community supported healing and recovery” (Archibald 2006, 39). The number of healing practices formed upon the values and worldviews of Indigenous peoples is extensive and beyond the scope of this short paper. According to Archibald, some of these promising traditional healing practices include: healing circles, sweat lodges, pipe ceremonies, dream interpretation, fasting, herbal medicine, returning to a traditional diet, cleansing and prayer, ceremonies including singing and drumming, counselling by a healer or Elder—all of which can be used in tandem with one another (Archibald 2006, 54).

While Western traditions on their own cannot serve to provide healing for Indigenous peoples, Linda Archibald’s 2006 report for the AHF describes how many healing programs have successfully incorporated, adapted, and blended traditional and Western approaches (Archibald 2006, 50). According to Archibald’s report:

Traditional ceremonies, medicines and healing practices are being incorporated into the therapeutic process while Indigenous values and worldviews are providing the program framework. Some core values, such as holism, balance and connection to family and the environment, are common to Aboriginal worldviews across cultures; others are clearly rooted in local customs and traditions. The variety of therapeutic combinations in use suggests a powerful commitment to the values of adaptability, flexibility and innovation in the service of healing. This is consistent with the holistic approach to healing common to Indigenous value systems (50).

While Western approaches may be incorporated into Indigenous healing initiatives, it is essential that Indigenous values and world views remain the foundational framework for such efforts.

The Future of Indigenous Healing in Canada

The AHF’s Final Report suggests that “10 years is the average period required for initiating, establishing and evaluating therapeutic healing from residential school trauma in a community or community of interest” and that it “takes time for individuals and communities to reach the ‘readiness to heal’ stage” (Archibald 2006, 39). Because of this, continued stable government funding is required for communities to “engage in a continuum of healing” including processes of reaching out to survivors, dismantling denial, creating safety, and engaging participants in therapeutic healing (39). While the AHF had incredibly positive outcomes for Indigenous communities and individuals, according its Final Report, “20% of the communities are just beginning their healing activities, 65.9% of the communities accomplished a few goals, but much work remains and 14.1% of the communities accomplished many goals, but some work remains” (31). Unfortunately, the de-funding and dissolution of the AHF has left hundreds of community-based healing initiatives without necessary funding, and new initiatives struggle to acquire financial support. The Government of Canada’s cut to such funding is detrimental to the ongoing healing work that Indigenous communities require, and is antithetical to the promises of the TRC’s Calls to Action. How can the Government of Canada support the mandate of the TRC while actively denying funding for community-based, Indigenous-led healing initiatives? Without the actual funding, these Calls to Action are nothing more than empty promises and lip service.

In 2012, Linda Archibald prepared a report entitled Dancing, Singing, Painting, and Speaking the Healing Story: Healing through Creative Arts for the AHF. In this report, Archibald asserts that along with traditional Indigenous healing practices, the creative arts can and have had profound healing effects for Indigenous peoples. Archibald’s study ultimately asked: “what happens when art, music, dance, storytelling, and other creative arts become a part of community-based Aboriginal healing programs?” (Archibald 2006, 1). According to the results of the study:

The role of the arts is explained through three interconnected models of healing: the first focuses on the innate healing power of creativity (creative arts-as-healing); the second speaks to the use of the arts in the therapeutic process (creative arts-in-therapy); and the third encompasses a holistic approach to healing that includes creative arts, culture, and spirituality within its very definition (holistic healing includes creative arts). The first two models can be found in the existing art therapy literature. The third model, which grew out of the research, was necessary to complete the picture with respect to Aboriginal people because so many of the responses to the survey and interview questions transcended the two existing models. In these cases, creative arts were considered inseparable from culture, spirituality, and holistic healing. Traditional healing encompasses culture, language, history, spirituality, traditional knowledge, art, drumming, singing, dance, and storytelling as well as knowledge specific to the healer’s area of expertise and the type of healing being undertaken. It is a comprehensive, holistic approach aimed at restoring balance. (2-3).

This study shows how creative arts are not only productive in Indigenous healing practices, but are actually inseparable from Indigenous cultures and spiritualities. As such, it is necessary to look at when and how the creative arts have been utilized by Indigenous peoples to facilitate healing through the return to traditional communities, cultures and lands.

Indigenous Aesthetic Action: Combatting Colonial Notions of “Healing”

As previously described, the creative arts are an inseparable component of Indigenous cultures, spiritualties, and, consequently, healing. I will now turn to examples of Indigenous artists and/or projects that have made use of the creative arts to not only practice healing, but also to question and combat the Western colonial notions of healing that underpin the notion of reconciliation put forth by the TRC and the Government of Canada.

Dylan Robinson and Keavy Martin utilize the term “aesthetic action” to describe creative endeavors that “unsettle us, provoke us, and make us reconsider our assumptions” (Robinson and Martin 3). Aesthetic action does not refer to aesthetics in the traditional sense of the word; it alternatively refers to the affective quality of the arts and how the arts can move us—most importantly to how they move us to action. In accordance with Garneau and McDonald’s assertions, Robinson and Martin assert that “the concept and practice of reconciliation must be continually interrogated and reimagined” (3). More specifically, Robinson and Martin believe that art—aesthetic action— “is the ideal mechanism through which this can occur” (3). In this way, we can view creative endeavours that function as healing practices and as critical interrogations of the colonial notion of reconciliation as works of aesthetic action. While there are numerous exceptional examples of Indigenous works of aesthetic action, due to the limited scope of this paper, I will focus on three such examples: Digital Natives, Walking with Our Sisters, and (official denial) trade value in progress.

Image from: https://twitter.com/livresCAbooks/status/822114905004253184

Digital Natives (2011)

Digital Natives (2011) is a collaborative project produced by Other Sights for Artists’ Projects, a non-profit collective of Vancouver-based individuals, and was curated by Lorna Brown and Clint Burnham (Image 1). During April 2011 (coinciding with the 125th Anniversary of the City of Vancouver) the project displayed ten-second text messages in English and Indigenous languages, interrupting the usual rotation of advertisements on the electronic billboard at the Burrard Street Bridge. Curators Brown and Burnham invited artists and writers from across North America to contribute messages (digitalnatives.othersights.ca). The messages “responded to the site’s charged history,” and the billboard itself “became an artistic and literary space for exchange between native and non-native communities exploring how language is used in advertising, its tactical role in colonization, and as a complex vehicle of communication” (digitalnatives.othersights.ca). More specifically, the project aimed to expose the “lack of public acknowledgement that Vancouver is built upon unceded Coast Salish territory” (Robinson and Zaiontz 43-44). Some of the messages included: “In 1913, all traces of the original village were burned to the ground…,” and “Your grandparents’ unacknowledged debts return to you as rage against the car in front.” Some of the messages were censored by the owner of the billboard, Astral Media, leading Brown and Burnham to add printed lawn signs upon a city-owned piece of land in front of the Burrand Street Bridge. One of the censored messages written by Edgar Heap of Birds pointed directly to the traumas of the residential schools, and the hypocrisy of Vancouver’s relationship with this history (specifically during the 2010 Olympic games in Vancouver), stating: “IMPERIAL CANADA AWARDED SEX ABUSE TO NATIVE YOUTH BY THE BLACK ROBES NOW PROUDLY BESTOWS BRONZE SILVER GOLD MEDALS WITH INDIAN IMAGE” (uppercase in original).

Photo from: https://covapp.vancouver.ca/PublicArtRegistry/ArtworkDetail.aspx?ArtworkId=467

Digital Natives is an example of aesthetic action in that it provides a healing opportunity for Indigenous folks who are able to reflect upon and share their own personal traumas, while also challenging Vancouver’s hypocritical position on reconciliation. On June 17h 2014, the City of Vancouver tabled a motion to become “the world’s first city of reconciliation” (Robinson and Zaiontz 47). What does becoming a “city of reconciliation” really mean, when the city actively resides on unceded Coast Salish land? And, as asked by Robinson and Zaiontz, “what tangible benefits will First Nations secure from the subsequent development of protocols with the City of Vancouver?” (47). Robinson and Zaiontz claim that “to develop a civic infrastructure of redress means to develop a corresponding model for urban planning that acknowledges Vancouver’s location on unceded Coast Salish territory” (48). It is not enough for a city to simply proclaim that they are a “city of reconciliation”—this must be coupled with concrete action and redress. As a work of aesthetic action, Digital Natives commandeered the city’s infrastructure, reclaimed Indigenous space, and served as a direct intervention of the empty rhetorical promises of “reconciliation” espoused by the City of Vancouver.

Image from: https://othersights.ca/digital-natives/

Walking with Our Sisters

Walking with Our Sisters is a commemorative art installation for the missing and murdered Indigenous women of Canada and the United States curated by Christi Belcourt (Image 2). Walking with Our Sisters is “comprised of 1,763+ pairs of moccasin vamps (tops) plus 108 pairs of children’s vamps created and donated by hundreds of caring and concerned individuals to draw attention to this injustice” (walkingwithoursisters.ca). According to the installation’s website:

The work exists as a floor installation made up of beaded vamps arranged in a winding path formation on fabric and includes cedar boughs. Viewers remove their shoes to walk on a path of cloth alongside the vamps” (walkingwithoursisters.ca). Each pair of vamps represents one missing or murdered Indigenous woman. The unfinished moccasins represent the unfinished lives of the women whose lives were cut short. The children’s vamps are dedicated to children who never returned home from residential schools. Together the installation represents all these women; paying respect to their lives and existence on this earth. They are not forgotten. They are sisters, mothers, aunties, daughters, cousins, grandmothers, wives and partners. They have been cared for, they have been loved, they are missing and they are not forgotten (walkingwithoursisters.ca).

Image from: https://twitter.com/christibelcourt/status/1004250177379688448

According to curator Chirsti Belcourt, “what we are doing here is not an exhibit… it’s a memorial. It’s commemoration and it’s a ceremony” (walkingwithoursisters.ca). As such, the creation of the installation itself was a healing process for all of those involved. Additionally, those who come to view the installation become implicated in a healing practice as well. As the installation travels to various locations, more and more Indigenous and non-Indigenous folks can bear witness to the trauma of not only Canada’s colonial past, but the current epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. The installation is never complete as people can add vamps to the installation at any time. Walking with Our Sisters is always actively growing and never complete, emulating the previously discussed nêhiyawak (Cree) notion of ê-kiskakwêyehk meaning “we wear it”—healing from trauma is a continual, active process that is ongoing, and, like Belcourt’s installation, never complete. Walking with Our Sisters resists the Western notion of healing as a destination to be reached, combatting the problematic rhetoric of reconciliation, and moving towards the necessary work of conciliation.

Photo from: https://www.easterndoor.com/2017/07/07/walking-with-our-sisters-steps-into-kahnawake/

(official denial) trade value in progress (2014)

(official denial) trade value in progress (2014) is another collaborative project curated by Leah Decter and Jaimie Isaac. The project “asks members of the public to contribute written and sewn responses to Harper’s G20 statement through a series of participatory events” (Decter and Isaac 97). Indigenous and non-Indigenous contributors were asked to write down anything they desired in response to Harper’s statement inside a set of books. Next, other contributors were asked to select a statement from one of the books that resonated with them, and stitch it onto a set of reconfigured Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) blankets. The G20 statement is “machine sewn in formal font” at the centre of the blankets, around which an “ever-increasing corpus of responses” are hand-stitched (100). The project allows Indigenous and non-Indigenous contributors to work together on a healing initiative that is never finished, and constantly being added to—much like how the Walking with Our Sisters installation encourages ongoing, active memory-work. In this way, (official denial) trade value in progress allows for a healing conciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous folk that does not place the sole responsibility of healing on the shoulders of the colonized. In this way, settlers “undertake the work of decolonizing themselves as a step in decolonizing the settler colonial regime that underpins the nation state of Canada” (Regan 2). Additionally, the project responds to official narratives of reconciliation in that it directly unpacks and criticizes Stephen Harper’s controversial “apology” that encouraged Indigenous people to “move on” from historical and ongoing trauma. To add another layer of aesthetic action, the fact that the contributor statements are sewn onto the iconic HBC blankets imbeds the project “into a larger context of colonial policies that intersect with economics, land, culture, and sovereignty (Decter and Isaac110). As a project of aesthetic action, (official denial) trade value in progress functions as a healing initiative implicating both Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations in the process, and as a critical resistance to the Canadian government’s hypocritical promise of “reconciliation.”

Photo from: https://www.communitynewscommons.org/our-city/politics/official-denial-trade-value-in-progress-a-response-to-stephen-harper/

By unpacking three creative projects, Digital Natives, Walking with Our Sisters, and (official denial) trade value in progress, the role of aesthetic action in allowing Indigenous healing initiatives to take place alongside the critical resistance to official narratives of reconciliation becomes emphasized. For conciliation to be achieved in Canada, the Government of Canada can no longer rely on empty promises of healing through Western-oriented approaches. Indigenous values and worldviews must be embraced in order to continually educate the public and to continually address Indigenous wounds inflicted by the colonial state. While art cannot hold all of the answers for achieving conciliation, as this paper has demonstrated, aesthetic action through the creative arts proves to be an invaluable tool for decolonizing healing for Indigenous peoples and combatting official projects of “reconciliation” that insidiously benefit the colonial project in Canada. In the words of David Garneau “art is not healing in itself, but it can be in relation” (Garneau 39).

Photo from: https://www.communitynewscommons.org/our-city/politics/official-denial-trade-value-in-progress-a-response-to-stephen-harper/

End Notes

1 See MacDonald, David Bruce. The Sleeping Giant Awakens: Genocide, Indian residential schools, and the challenge of conciliation. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2019.

Works Cited

Aboriginal Healing Foundation. A Healing Journey: Final Report Summary Points. 2006.

Archibald, Linda. Dancing, Singing, Painting, and Speaking the Healing Story: Healing through Creative Arts. Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2012.

Archibald, Linda. Decolonization and Healing: Indigenous Experiences in the United States, New Zealand, Australia and Greenland. Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2006.

Archibald, Linda. Final Report of the Aboriginal Healing Foundation Volume III:

Promising Healing Practices in Aboriginal Communities. Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2006.

Decter, Leah and Jaimie Isaac. “Reflections on Unsettling Narratives of Denial.” Arts of Engagement: Taking Aesthetic Action in and Beyond the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, edited by Dylan Robinson and Keavy Martin. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2016.

“Digital Natives.” digitalnatives.othersides.ca. Accessed September 2020.

Episkenew, Jo-Ann. Taking Back Our Spirits: Indigenous Literature, Public Policy, and Healing. University of Manitoba Press, 2009.

Fontaine, Phil and Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. A Knock on the Door: The Essential History of Residential Schools. University of Manitoba Press, 2016.

Garneau, David. “Imaginary Spaces of Conciliation and Reconciliation.” Arts of Engagement: Taking Aesthetic Action in and Beyond the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, edited by Dylan Robinson and Keavy Martin. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2016.

Martin, Keavy, et al. Arts of Engagement: Taking Aesthetic Action in and Beyond the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Dylan Robinson and Keavy Martin, Editors. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2016.

McCall, Sophie, and Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill. The Land We Are: Artists & Writers Unsettle the Politics of Reconciliation. ARP Books, 2015.

Methot, Suzanne. Legacy: Trauma, Story and Indigenous Healing. ECW Press, 2019.

Robinson, Dylan and Keavy Martin. “The Body is a Resonant Chamber.” Arts of Engagement: Taking Aesthetic Action in and Beyond the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, edited by Dylan Robinson and Keavy Martin. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2016.

Regan, Paulette. Unsettling the Settler Within. UBC Press, 2010.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Canada's Residential Schools: The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. McGill-Queen's University Press, 2015.

Waldram, James B. Aboriginal Healing in Canada: Studies in Therapeutic Meaning and Practice. Prepared for the National Network for Aboriginal Mental Health Research in partnership with the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2008.

“Walking with Our Sisters.” http://walkingwithoursisters.ca. Accessed September 2020.

Wesley-Esquimaux, Cynthia C., and Magdelena Smolewski. Historic Trauma and Aboriginal Healing. Prepared for the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2004.

#orange shirt day#reconciliation#trc#canada#Canadian Politics#indigenous issues#truth and reconciliation#residential schools#walking with out sisters#digital natives#Indian Residential School System#cultural genocide#The Digital Witnesses#Communications Studies#Indigenous Studies#Alyssa Logie

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

— IT IS WIP SUNDAY ♡

TAGGED BY the dear @adelaidedrubman, @morvaris, @aartyom, @risingsh0t, @nightbloodraelle, @phillipsgraves and @leviiackrman to post a wip or two ! ♡

TAGGING: @feystepped, @griffin-wood, @kingsroad, @jendoe, @chuckhansen, @queennymeria, @denerims, @marivenah, @shellibisshe, @jacobseed, @blissfulalchemist, @unholymilf, @corvosattano, @jackiesarch, @fragilestorm, @yennas, @wayhavenots, @malefiicarum, @roofgeese, @detectivelokis, @socially-awkward-skeleton, @jinfromyarikawa, @nuclearstorms, @girlbosselrond, @anoras, @shadowglens, @arklay, @swordcoasts, @nokstella, @danielsullivan and YOU!

as she has had a vice grip on the brain a cute piece for olga ♡ in the future will include minerva and santo and alyssas logan !

The odds of FEDRA’s successes against the Washington Liberation Front are bleak at best. If she is being frank, they’re losing.

They will reach the basement. They will find the specimens in the vault. They will find them. They will find her.

And they will not have her research.

The soldiers protecting her outside have likely been taken out. Her colleagues, the ones who didn’t leave on Allards transport with her mentor gisela, fleur, yori, and ondria and didn’t manage to find ways out on their own were likely detained or taken out as well. Leaving her alone.

She wanted it this way. She won’t let the wrong hands reach what she has worked years for to understand the Cordyceps. She won’t let them reach her.

“Mother, if this is to be my swansong, I want you to avenge me.” she whispers to herself as she removes her lab coat and research scrubs. Olga was currently on the residential level, and she had the room renovated to include a private elevator leading down directly into the research floor; she'll reach the basement level before they do.

Olga headed from the window overlooking the outer courtyard of what was once the University of Washington hospital; which FEDRA and the Center for Disease Control, or CDC, had turned into a research facility. Walking to her bed and putting on the dress she had laid there Olga made her way to the vanity on the opposite end of her bed.

She was taught to look her best when treating guests. Even still, she holds the words of her mother in regard.

It was her mothers dress, a vintage gown from 2002, the soft blue silk slip dress felt dreamlike on her. She would be wearing this for her memory. Olga, now sitting on the chair gazing at her reflection from the vanity, put on a pair of pearl earrings and a pearl necklace, humming to the tune of Tchaikovsky’s swan lake as she did.

The swan will choose her fate today.

ive also began working on the former seattle crew / former washington dc crew and here is what i have so far of minervas ♡ using the loveliest mari's template !

a cute lil piece for una with this template by the lovely ash ♡

and lastly ! a vicky piece using this template! featuring aj’s nessie ♡

#only if you want to! 🤍🕊#oc: olga litvinchuck#oc: minerva graves#oc: una nathaira uller#oc: viktor mason#leg.tagged#leg.ocs#leg.writing#she was convinced this was to be her last dance so she was going to make it ♡ poetic ♡ u know?#a bit theatrical but as was said! she had to make it poetic! and i adore her for that !#im thinking there will be two povs here one of olga and the other being someone else? maybe santo or minerva?#because im thinking santo did a stint as a wlf ? he was also a firefly as well before dipping (minerva also was wlf before she dipped too)#gianna and alaia left seattle MONTHS prior i think so they completely miss the shenanigans jaksnxkn#and there is a prologue to this planned both from the povs of minerva in the wlf AND from olga and the besties !#LISTENNN I AM IN MOURNING......! and so is miss minnie! ILL NEVER FORGET U DEAR ! (it does mean shes available @ aj and alyssa hehe)#(and besties/mutuals ! more besties for the t*lou besties!!!! <3)#not me WHEEZING yesterday @ 3 am when it hit me like a TRUCK that minnies type in her f*allout and t*lou verses is old men AJHASBHXJS#h*ancock in f*allout and p*erry in t*lou GOOD FOR HER nksajnx#and at a point either in swansong or in a companion piece'll be olgie meeting logie <3 EXCITEDD#spitfire or trigger happy spitfire jksanknw tiny menace is another alias that would fit minnie kjnsakjnk <3#Viktor trying and failing gloriously by his GENIUS thinking if he switched the first letters of his first and last name nobody would find#his socials kjaskxw you nerd u ! my heart I LOVEHIM DEARLY#teehee shrieking about unas song and her card being the tower and her mbti SHRIEKING ABOUT HERR <3#her and vanna always on my heart always on my mind ! I LOVE THEM DEARLY#and once more we must shriek about mari and ash and their TALENT and these templates <3 ! YOU BOTH ARE TREASURES !!!!!!#kilian may totally not at all get a love interest of his own hehehe <3 AJ I AM SO SO LOOKING FORWARD TO WHAT U HAVE IN MIND FOR HIM <3#I am thinking for post!p*erry minnie maybe santo? or someone else? as theyve been longtime friends! it would be cute!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zine Fair Launch Party The night before the Small Press Zine Fair we’re throwing a party at Studio 65

Friday November 16 $5 entry, bar, 7pm til late Level 3, 65 Murray Street (go up the elevators to the left of Lush on Murray Street)

Facebook event

8pm Read To Me 7 audiovisual stories will be performed LIVE by local and interstate artists. Paul Peart-Smith (Cygnet/UK) Leigh Rigozzi (Koonya) Alyssa Bermudez (Hobart/USA) Logie award winner Tony Thorne (Hobart) Vivienne Cutbush (Hobart), Lucy Adelaide (Hobart) and SPECIAL GUEST from Sydney Meg O’Shea, Ignatz award nominee 2018.

Each of these artists creates personal, thoughtful, occasionally heartbreaking, sometimes hilarious works for adults, skillfully manipulating the comics medium to create powerful, moving content. Their work addresses political themes, issues of identity, memory, and place, and range in form from comic journalism, to philosophy, fiction and biography.

9pm DJ Philistine makes her triumphant comeback!

This event is supported by Island magazine, San Kessto Publications, Read To Me, and 3/65, The Small Press Zine Fair will be on the following day from 1-5pm at the Battery Point Community Hall.

Zine Fair Launch Party Zine Fair Launch Party The night before the Small Press Zine Fair we’re throwing a party at Studio 65…

#Alyssa Bermudez#Animation#Hobart#Joshua Santospirito#Leigh Rigozzi#Lucy Adelaide#Meg O&039;Shea#Paul Peart-Smith#Read To Me#Small Press Zine Fair#Stories#Tony Thorne#Vivienne Cutbush#zines

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

yeehaw fantrolls

Kruiss: 1. Thief of Heart 2. Wears fake gucci 3. Doesn’t understand how the hemospectrum works even tho he’s at the top of it??

Lousic: 1. It’S NOT A PHASE, LUSUS 2. Page of Blood 3. what the fuck are his horns he can’t even function correctly dskjhks

Ringgo: 1. Slept with your lusus 2. Body-builds with fake weights to impress them yellow bloods 3. goes to frats and doesn’t drink

Pennli: 1. Everyone pronounces her name ‘penis’ and shE IS SO FUCKING DON E 2. The HeathersTM 3. i x 4 = iiii am very fuckiiiing sad

Aldiis: 1. bE MO R E CHIIIIILLLLL 2. rogue of light 3. eat shIT LOGI C *she says as she eats 15 glowsticks*

Rianna: 1. Brings medicine 2. kids please i’m only one brown blood not 2 jades 3. likes your mom more than she likes you

Reclus: 1. Wears baseball shirts tucked into sweatpants tucked into socks 2. doesn’t wear face paint it’ll clog up my pours eW 3. sips the coldest of warm teas

Alyssa: 1. Her tea is boiling and her horns are freshly waxed fuck with her 2. cut off her hair and regretted it so she tied it around a ring and reconnected it 3. doesn’t wear makeup she just has really long eyelashes i mean goddamn

0 notes

Text

Character Assassination, Reputation Destruction and Denial of Due Process: The Aim of Making Allegations via Media and Social Media

The latest allegations made via the media and social media against an entertainment industry male did not occur in isolation. They are entitled to be seen in a much wider context.

The Chronology

Relevantly the Australian federal government has 30-day invoice payment terms.

On 20 April 2016 Former bank teller, Greens Senator Sarah Hanson-Young was invoiced $20,460.76 for staff travel expenses. She took almost a year to pay it back – 355 days.

June 2016 2 Greens Senators failed to do due diligence in relation to their foreign citizenship prior to nominating for the federal election.

Friday 10 June 2016 “In a Friday core team meeting, [Ms Anonymous Victim] reported to the campaign manager and two other staff members that I was being sexually harassed by the man who ended up assaulting me.”

Saturday 2 July 2016 Ms Anonymous Victim claims “On the night of the federal election, driving away from the ACT Greens election party, I was sexually assaulted in the back of a car on Commonwealth Bridge, leaving Parliamentary Circle.”

Saturday 2 July 2016 15 minutes after the alleged assault “the ACT Greens election campaign manager was informed of the assault”

2017 Australian Federal Police are not notified until over a year later. “Police didn’t like my “odds”. There had been no documentation by the [Greens] party of the assault or the preceding harassment to verify my statement. Time had passed and there was no physical evidence.” “Time had passed and there was no physical evidence” That is a consequence of the voluntary decision Ms Anonymous Victim made to not report her alleged assault to the police, but rather to the Greens Party.

Late January 2017 The NSW Greens formulated a sexual harassment policy

Thursday 16 February 2017 The Greens NSW first received a formal complaint about the alleged incident involving journalist Lauren Ingram

Monday 20 February 2017 The member was formally and indefinitely suspended and all member rights were removed.

Apparently Ms Anonymous Victim, the ACT Greens volunteer, had not heard of this and it did not inspire her to go to the police

Sunday 18 June 2017 Journalist Lauren Ingram alleged via her Twitter account that she was sexually assaulted by a NSW Greens party member and former employee

On 11 July 2017 Greens Senator Sarah Hanson-Young was invoiced for a $1234.90 car hire expense. She failed to reimburse taxpayers and pay the invoice for a period of at least 129 days.

Saturday 5 August 2017 ABC published an article contending the NSW Greens knew about Lauren Ingram rape allegations months before taking action. “The man in question has now responded, saying he denies all the allegations. ‘He wrote in an email that he believes that in Australia, justice is served through our established justice system and that it cannot be served through the “social media lynch mob”’

Saturday 5 August 2017 Detective Superintendent Linda Howlett, from the New South Wales sex crimes squad: "The other thing we certainly don't want is for that social media comment to be out before a judge and jury, because it could place doubt on the actual circumstance the investigation or anything the victim might say."

"Until a person is actually convicted, they're innocent in the eyes of the law of that particular offence."

Thursday 5 October 2017 The New York Times published sexual assault claims from actors Ashley Judd and Rose McGowan against Harvey Weinstein Mr Weinstein subsequently denied at least some of the allegations against him.

Sunday 15 October 2017 Actress Alyssa Milano encouraged women to share their tales of sexual harassment and assault on social media using the #MeToo hashtag.

Wednesday 18 October 2017 Journalist Tracey Spicer said on Twitter “Currently, I am investigating two long-term offenders in our media industry. Please, contact me privately to tell your stories.”

Friday 27 October 2017 The High Court found 2 Greens Senators were disqualified from being chosen or sitting in the Senate because they were foreign citizens at the time they nominated for election. Their failure to do due diligence in relation to that foreign citizenship in June 2016 was fatal to their respective cases.

Monday 27 November 2017 Allegations against Channel 9 television personality Don Burke were published. Mr Burke subsequently denied at least some of the allegations against him.

Thursday 30 November 2017 The Daily Telegraph ran a front page story on allegations against Geoffrey Rush. Mr Rush denied the allegations against him.

Saturday 2 December 2017 Greens Senator Sarah Hanson-Young said on Twitter “First Don Burke then Geoffrey Rush. As more & more stories of men in the media and entertainment industry comes out it is up to the rest of us to listen and believe the women who dare to speak out. They are brave and deserve space to be heard”

Monday 4 December 2017 ABC: "the Tele could find itself on the wrong end of a very expensive defamation action."

Friday 8 December 2017 Geoffrey Rush files defamation claim against the Daily Telegraph over misconduct allegations

Friday 15 December 2017 A lawyer and qualified mediator in dispute resolution, Tessa Sullivan resigned from her position on the Melbourne City Council to which she was elected in November 2016. In doing so she made public allegations of sexual harassment, indecent assault and misconduct against Melbourne Lord Mayor Robert Doyle.

Sunday 17 December 2017 Melbourne Lord Mayor Robert Doyle stood aside for a month pending an independent inquiry into the allegations. He denied the allegations

Saturday 23 December 2017 The article about Ms Anonymous Victim appeared in the Saturday Paper

Wednesday 3 January 2018 Victorian Chief Magistrate Peter Lauritsen said every member of the community is entitled to the presumption of innocence

Sunday 7 January 2018 Allegations are made via the media and social media against an entertainment industry male. He denied the allegations.

Tuesday 9 January 2018 “Human Rights” activist Senator Sarah Hanson-Young gave her support and gratitude to the complainants, but not the rule of law and the presumption of innocence.

Thursday 1 February 2018 "Gold Logie winning actor Craig McLachlan filed defamation proceedings against Fairfax Media and the ABC after they reported on allegations he sexually harassed several former colleagues."

"One of McLachlan's accusers, former co-star Christie Whelan Browne, has also been named in the defamation suit."

Observations Allegations made via the media and social do not have the constraints of complying with due process. Evidence said to support the allegations is often not provided when the allegations are published. Reputation damage occurs to the accused as a result of public commentary, discussion and speculation on the published allegations. That is the aim of their publication. It occurs before any court case which might enable the accused to test, challenge and / or refute the subject allegations. Any statement the accused might make in respect of the allegations published in the media and social media might compromise the approach he or she would take at trial. Not every accused has the wherewithal to institute defamation proceedings against those who have published defamatory allegations and / or commentary. Those defamation proceedings risk repeating the defamatory allegations and / or commentary.

0 notes

Text

Architecture, Cityscapes and Capitalism: A discussion on Fredric Jameson & Blade Runner

By: Alyssa Logie (MA in Media Studies Candidate, Western University)

In his piece “The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism”, Jameson refers to how postmodern culture, and all analyses of it, are always attached to the nature of capitalism—more specifically, the present state of multinational capitalism (Jameson 558). Jameson urges us to see postmodernism not so much as a style, but as a cultural dominant of late capitalistic logic. He also asserts that the movement towards postmodernism and the subsequent modifications in aesthetic production are “most dramatically visible” in the realm of architecture (557). Jameson’s discussions of architecture intrigued me. He goes on to discuss architecture in more depth, stating:

“Of all the arts, architecture is the closest constitutively to the economic, with which, in the form of commissions and land values, it has a virtually unmediated relationship. It will therefore not be surprising to find the extraordinary flowering of the new postmodern architecture grounded in the patronage of multinational businesses, whose expansion and development is strictly contemporaneous with it” (560).

The “aesthetic new world” (567) of multinational capitalism is most visible in the art of architecture. If we are to view this particular use of aesthetics as related to the nature of capitalism, we must think about how the aestheticization of architecture is directly related to the goals, beliefs and motivations of multinational capitalistic logic. In other words, through architecture, we can most clearly see the hidden motivations and insidious nature of capitalism before us; the blatant expressions of “America military and economic domination” (560) stand before us in the towering and mystifying horizons of our cityscapes. Jameson’s discussions of how architecture reveals the militarized nature of capitalistic aesthetics reminds me greatly of Paul Virilio’s book, Pure War, in which Virilio discusses how everything and everyone in our world is mobilized towards the intentions of war. (A great read, check it out!!!). Virilio asserts that the city is “the result of war…of preparation for war”; the constitution of our cities is based in the perpetual preparation for war (Virilio 19). Virilio also echoes Jameson’s notions of capitalism’s militarization of architecture in his work, “Bunker Archaeology”—he believes that the architecture of war-time bunkers is actually present in our current cityscapes and architecture.

I began to think about Blade Runner and Blade Runner 2049’s depictions of capitalistic cityscapes. A common motif of both films are the prolonged shots of sprawling, dark and insidious cityscapes all of which are entirely submersed in advertising culture. The prolonged shots serve to call attention to the economically-dominated spaces of the cities that are, not so deep beneath their shiny, hyperreal surfaces, highly militarized. The cityscapes of both films allude to “how urban squalor can be a delight to the eyes when expressed in commodification” (562)—it is the commodified nature of these spaces that is familiar to us, where we may find comfort in the dark, all-encompassing landscapes of Blade Runner that threaten to “crush human life altogether” (563). This calls to mind Jameson’s discussions of a technological sublime: an experience bordering on terror, the fitful glimpse, in astonishment, stupor and awe…” (563). I think these films are calling us to think about the dual nature of our cityscapes—they are both euphoric, and terrifying. Our cities are not that different than those depicted in Blade Runner (consider how Blade Runner depicts Los Angeles in 2019…). Our cities are exhilarating and anxiety-inducing all at once; the “alienation of daily life in the city can now be experienced in a strange new form of hallucinatory exhilaration” (562). In a sense, the advertisement and commodified nature of our cities seems to conceal the militarized nature of them.

I’d also like to point out how the landscapes in Blade Runner and Blade Runner 2049 are highly antianthropomorphic—they are not spaces for humans. Think of the sprawling digital advertising boards, the large holographic women and the never-ending display of artificial lights…The highly technical, digitized and mediatized spaces render humans as alien. There is a “derealization of the surrounding world” in which the world has lost its depth, and is reduced to nothing but a “glossy skin…a stereoscopic illusion, a rush of filmic images without density”: postmodern (562).

The current architecture of our international capitalistic societies, as well as the sprawling landscapes of the Blade Runner films reminds us how “throughout class history, the underside of culture is blood, torture, death and terror” (560).

Blade Runner (1982) Los Angeles Cityscape in 2019: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nx02tM0os7k

#fredric jameson#blade runner#blade runner 2049#media studies#cultural theory#capitalism#architecture#alyssa logie

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Body is “Just Visiting”, But the Art Never Dies: David Bowie’s “Lazarus”

On January 10, 2016, the world was shocked and devastated to hear that David Bowie had passed away. Three days before his death, the concept music video for his song “Lazarus” from his final album Blackstar was released. The “Lazarus” music video is Bowie’s final construction of himself as an artist who values self-expression and the creation of art at all costs—even when he was faced with death. The video further perpetuates the image of Bowie as a musical innovator and unparalleled creative energy through the depiction of two images of Bowie: his sick and dying physical body, and his lively and creative energy. The juxtaposition of these two images constructs the idea that although Bowie’s physical self has died, his art and creative energy will live on forever. This is the final image of himself that Bowie had constructed and left behind for the world.

Bowie brilliantly juxtaposed two different images of himself in the “Lazarus” video as a way to construct the final understanding of himself as an artist before he died. He cleverly displayed how although his physical body was dying of cancer, his artistry and creative energy will never die. Viewers are first confronted with the image of Bowie sick and dying in bed. The camera slowly pans the entirety of his body; close-up shots emphasize his translucent and wrinkled skin. It is made clear that he is very ill and close to death. This image of Bowie represents his physical self, one that is rapidly decaying from cancer and facing death. The camera floats freely around Bowie as he lays convulsing in bed. The camera’s movements are highly disorienting and correspond to the lyrics, “I’m so high/ It makes my brain whirl”. These swirling motions mimic Bowie’s disoriented experience from the drugs he had consumed during his illness, highlighting how sick and fragile this version of Bowie was. A mysterious girl is underneath Bowie’s bed; she reaches for him from underneath, inches away from touching his body. She represents death that looms so closely to Bowie’s physical self. Bowie lifts himself from the mattress to resist the hands of death a little longer—he has something more to say to the world.

The second version of Bowie is standing upright; he is still able to dance and perform. This version represents the creative and artistic energies of Bowie that resided inside his physical self. Shots of this version of Bowie feverishly writing at a desk emphasize his need to express himself creatively before his physical body dies and he is no longer capable of doing so. He frantically writes and even scribbles right off the page, to show that he does not have enough time to express everything he needs to say before he dies. Bowie had a lot more creativity to share with the world, but he did not have enough time. The shots of him scrambling to get his ideas down on paper are juxtaposed with images of death (the woman) underneath Bowie’s bed, mimicking the ticking of a clock with her finger as if to say that his time is quickly running out. The editing becomes more and more rapid, and so does Bowie’s writing. The physical vessel from which his creativity was produced through is about to die. The sickly version of Bowie has a bandage around his head, with buttons covering his eyes. The image of buttons over his eyes calls to mind puppets or stuffed animals with button eyes, further contributing to the construction of this empty, physical body in which the creativity and artistry resided. This body was merely a vessel through which his creativity and art flowed. The bandages over Bowie’s eyes are also reminiscent of the 1962 science-fiction film La Jetée, “in which the protagonist is similarly bandaged as part of the technique used to send him on a journey through the fabric of time. A symbol of illness becomes a symbol of exploration” (Boyce 592). Death is but another transcendence or journey for Bowie’s artistry.

The lively version of Bowie is wearing a striped, black and white jumpsuit. This choice of costuming was a very meaningful and deliberate decision on Bowie’s part. This is the same costume Bowie wore in the film The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)—a film that features Bowie as a humanoid alien who comes to Earth from a far-away planet, and then attempts to travel back home (Image 1). Bowie’s character in the film repeatedly remarks that his is “just visiting” Earth. Like Bowie’s character in The Man Who Fell to Earth, the lively version of Bowie in the “Lazarus” video is “just visiting” and returns to wherever he came from before Earth. At the end of the video, Bowie steps into the wardrobe that appears throughout the entirety of the video. This large wardrobe calls to mind associations with other literary works, such as C.S Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, in which the wardrobe is a portal capable of transporting characters to a different land. Could this symbolize Bowie’s creative spirit transporting to a different place, perhaps back to where it came from before Earth? The wardrobe is also a common place to house various articles of clothing. Bowie was known for his ever-changing personas and imagery. Stepping inside the wardrobe alludes to this collection of personas being stored and remaining present in the world even after Bowie died. This version of Bowie steps into the wardrobe, constructing the idea that his creative and artistic energies are not dying alongside his physical body—they will transcend time and space, living on forever. Both the images of the costume and the wardrobe evoke a sense of transcendence and transportation. This is essential to the image of himself Bowie is constructing in the video. Like his ever-changing personas and imagery in his creative works, he is stating that his creative spirit is simply moving on, or travelling—it is not coming to an end. Death is another transcendence for Bowie’s creative works. The theme of transportation is also evident in the artwork for Bowie’s album Station to Station. Bowie used images directly from the film The Man Who Fell to Earth. Also, the album title Station to Station evokes a sense of moving from place to place. Oddly enough, Bowie has stated that the title Station to Station refers to the stations of the cross—these stations depict Jesus’ death and resurrection. Jesus resisted death; as does Bowie’s creative and artistic works. This is not the only religious connection in Bowie’s video.

The story of Lazarus rising from the dead is found in the Gospel narrative of John (Encyclopædia Britannica). Jesus had told his followers that Lazarus’ sickness would not end in death. This Gospel narrative is essential to the understanding of Bowie’s music video. Bowie portrays his creative artistry as able to resist and transcend death. Death will not stop the impact and perseverance of his creative works and art. Simply the fact that this essay is analyzing his music video post-mortem proves this point—Bowie’s works still, and will always have a lasting impact. Again, the concept of art transcending time is displayed in the video through the image of Bowie in the black and white jumpsuit. This is Bowie as Lazarus: the creative and artistic energies that will not die. They continue to live on post-death. Another religious reference in the video is alluded to through the lyrics. Standing in front of the wardrobe, Bowie sings, “By the time I got to New York/ I was living like a king/ Then I used up all my money”. Bowie then recedes backwards into the wardrobe, as if returning to where he came from. This can be interpreted as a reference to the parable of the prodigal son, who strays from his family to move to the city, loses all of his money, and then returns his father asking for forgiveness. Again, it is important to note the significance of Bowie’s costume here. The biblical allusions in the lyrics and video contribute to the idea that Bowie had come from somewhere else, created his art, and then was ready to return to wherever he came from. In this case, the man who fell to Earth is receding into the wardrobe. The creative energies are transcending time and space. They are being transported; they are not dying. As the image of Bowie in the black and white jumpsuit backs into the wardrobe, the bed-ridden Bowie lays down in bed, his arms open wide as if he is accepting the touch of death. His final message for the world has been constructed, and now his physical self is ready to succumb to the disease.

Bowie’s “Lazarus” video was his final gift and message for the world. As his last chance to construct himself as an artist through music video imagery, “Lazarus” allowed Bowie to remind his fans that although his physical self would not transcend time and escape the hands of death, his art and creative works will never die. His human body was mortal, while his creative works and the images he created as an artist are immortal. Of course Bowie knew exactly what he was doing when he created the “Lazarus” video: “Ain’t that just like me?”, Bowie sings. He is a man whose creative abilities transcend death. Bowie was a true artist to the very end—and beyond.

Works Cited

Bowie, David. “Lazarus.” Blackstar. Dir. Johan Renck. Columbia, 2016. Music Video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y-JqH1M4Ya8.

Boyce, Niall. “Strangers When We Meet: David Bowie, Mortality, and Metamorphosis.” The Lancet 387.10018 (2016): Web. 27 Sept. 2016.

"Lazarus." Britannica Academic, Encyclopædia Britannica, 19 Sep. 2016. http://academic.eb.com.proxy1.lib.uwo.ca/levels/collegiate/article/47447. Accessed 27 Sept. 2016.

#David Bowie#Lazarus#Blackstar#Music video#media studies#alyssa logie#digital witness#music video analysis

0 notes

Text

Open Your Eyes: Surrealist Cinema and Sigmund Freud

An essay by: Alyssa Logie, MIT & Cinema Studies - Western University.

Jean Goudal has noted that the cinema can be acknowledged as a “conscious hallucination” in the sense that the cinematic experience mimics the habitat of the dreamer (Goudal 89). Cinema as a conscious hallucination is most prevalent in films of the Surrealist movement through their application of Freudian concepts, such as issues of the unconscious and the importance of dreams. The application of Freudian concepts in Surrealist cinema is exemplified in the film Open Your Eyes (Alejandro Amenábar, 1997) through the film’s emphasis on the unconscious, basic drives, and the blending of dreams and reality. The utilization of these Freudian concepts calls attention to the “union of dream and reality”, allowing for the creation of a superior state of consciousness—absolute reality, or surreality (Magrini 10).

It is first beneficial to provide a brief description of the origins of the Surrealist movement in order more clearly understand its cinematic implications. The Surrealist Movement began in the early 1920s and involved various areas of culture such as art, literature, philosophy and film (Elder 262). In 1924, four key founding events of the movement occurred: André Breton’s publication of the Manifesto du surréalisme (Manifesto of Surrealism); the founding of the Surrealist Research Bureau; the release of the first issue of La révolution surréaliste; and the first issue of Surréalisme (263). These founding events outlined the movement’s principle aim of the “transposition of reality to a superior (artistic) level” (Kovács 25). In his manifesto, Breton described how Surrealism was against traditional and rational logics of thinking. Instead, Surrealism strove to represent the world through the language of dreams, motivations of the unconscious, and the “disinterested play of thought” (Magrini 1). In this way, Surrealism sought to bring together the “modes of the dream (unconscious) and reality (consciousness)” into a superior state of consciousness that was seen as an absolute reality or, “surreality” (1). With Surrealism’s emphasis on dreams and the interplay of reality and unreality, one cannot ignore obvious connections to the works of the father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud.

The Persistence of Memory, oil on canvas, by notable surrealist artist, Salvador Dalí, (1931).

The Surrealist Movement in cinema and the works of Sigmund Freud converge in multiple ways. Firstly, Surrealists “embrace Sigmund Freud’s notion that base drives and urges unconsciously form the personality” (Magrini 1). Surrealists attempt to make use of these primal base drives in film due to their creative potential. Freud discusses how base drives from the Id are kept under rational control by the Ego—Surrealists eliminate the rational influence of the Ego and draw explicitly from the primal drives of the Id (2). It is a main goal of Surrealism to force audiences into new modes of perception that diverge drastically from traditional, logical modes. These rational modes of logic are predominant in the classical model of filmmaking; that which relies on the traditional narrative structure. Surrealists seek to “subvert” this commercialized and oppressive cinematic model, providing audiences with a rather different and, perhaps, uncomfortable viewing experience (3). The motif of the eye is quite common in Surrealism, alluding to the importance of questioning traditional modes of sight and perception. This concept is best exemplified in Luis Buñuel’s notorious Surrealist film, Un Chien Andalou (1929). The opening sequence of the film shows a man slicing open a woman’s eye with a razor. This scene is a brutal wakeup call to the audience: Buñuel is calling spectators to destroy their traditional (logical) modes of sight and perception in order to embrace the illogicality of Surrealist film. (Knollmueller 211). Surrealism strives for an illogical mode of perception that can lead to a state of surreality that is more real than reality.

Un Chien Andalou: Luis Buñuel & Salvador Dalí's Surreal Film (1929).

The Surrealists drew from Freud’s “confirmation of existence of a deep reservoir of unknown and scarcely tapped into energies within the psyche” (Mundy 12). These energies or desires come from what Freud referred to as the unconscious (27). André Breton saw desire as “the authentic voice of the inner self” and as “integral to life itself” (11). Consequently, unconscious desires became a major focus of Surrealist filmmakers who sought to portray a superior mode of consciousness and surreality. In the late 1920s to the 1930s, desire—especially erotic desire—became central to Surrealist works. Surrealists sought to explore “darker aspects” of sexuality and the “deeper workings” of the mind. As such, they turned to Freud’s writings about unconscious sexual desires as a major source of inspiration. (12). Surrealism often includes objects or images that stand in place of “veiled or sublimated impulses and desires” (28). Surrealist objects are extremely personal, and are “symptomatic of an individual’s preoccupations”—their unconscious desires (Frank 16). These objects display the desires of characters through symbolism. Surrealist objects are seen as a point of contact with the unconscious, and offer a more “visual and familiar” representation of unconscious desires (18). However, these objects still maintain a “mysterious and ethereal quality” that distances them from physical reality (19). This integration of the unconscious and physical reality is a major concern of Surrealism, as Surrealists sought to show how the unconscious was a part of waking life, and wanted to encourage people to “embrace unconscious interventions” (18) Not only did Surrealists seek to reconcile the mind’s conscious and unconscious, they also sought to reconcile the realm of dreams and the realm of waking reality (18).

Reply to Red, Yves Tanguy (1943).

Intellectual developments about the importance of dreams had taken place immediately prior to the development of Surrealism. Newly understood aspects about dreams that fascinated Surrealist artists had a lot in common with aspects of film. Most specifically, dreams related to the “savagery” of film; film is immediate, raw, and directly addresses the eye (Elder 265). Artists realized that the “flow of images that bypasses the interpretive faculties” seen in films were much like the flow of images seen in dreams (265). Cinema as a whole is like a representation of a dream, for it “uncannily approximates the associative processes of the mind” and “avoids rational structures of traditional linguistic symbolization” (Magrini 6). Surrealists were against the traditional narrative modes of cinema, as the “form of the dream is not like that of a conventional story” (Elder 282). Breton described how the imperatives of logic and description in narrative forms lead to “false devices like precise descriptions and completely fictional entities” (282). On the contrary, the world of dreams allows for appearance to change “from moment to moment, where space is pliable and time has no meaning… the practice of providing an exact concrete setting for every action seems simply risible” (283). Surrealism denied the logic of the narrative form, and “was a movement that had emerged from the hypnogogic borderland between sleep and waking, where reverie dismantled rational control of the stream of thought” (287). Cinema proved to be the most beneficial medium by which to portray these Surrealist concepts, for the rapid images arrested the logical structures of the mind and could mimic the form of a dream (Magrini 6).

Sigmund Freud.