#Alfred Dreyfus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

On This Day In History

September 29th, 1902: Émile Zola was born. A French writer, he is best remembered for his participation in the literary naturalism movement, his work in liberalizing France, and his newspaper opinion J’accuse…! which helped to exonerate Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish-French army officer set up to take the fall by the army for a crime committed by a Catholic officer.

Zola was nominated for the first and second Nobel Prizes for Literature.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dreyfus Affair became a metaphor for antisemitism and, in one of the most unlikely and ironic sequence of events in Jewish history, Dreyfus (1859-1935), a wholly assimilated Jew, played a critical, if unintended, role in the rebirth of the State of Israel.

After French Intelligence had intercepted the “Bordereau,” a secret military document sent to the German military attaché (1894), Eduard Drumont, founder of the antisemitic daily La Libre Parole, published a report accusing Dreyfus, the only Jewish member of the French General Staff, of spying for Germany. Major Joseph Henry forged documents implicating Dreyfus and, after a secret trial, Dreyfus was convicted of treason (December 21, 1894) and sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil’s Island. He was paraded through the streets of Paris to mob jeers of “Death to the Jews” and was stripped of his sword in a humiliating public ceremony. Intelligence later seized a letter written by Major Ferdinand Esterhazy which clearly established that Esterhazy, not Dreyfus, was the German agent, but the French government quashed this evidence and Esterhazy was acquitted.

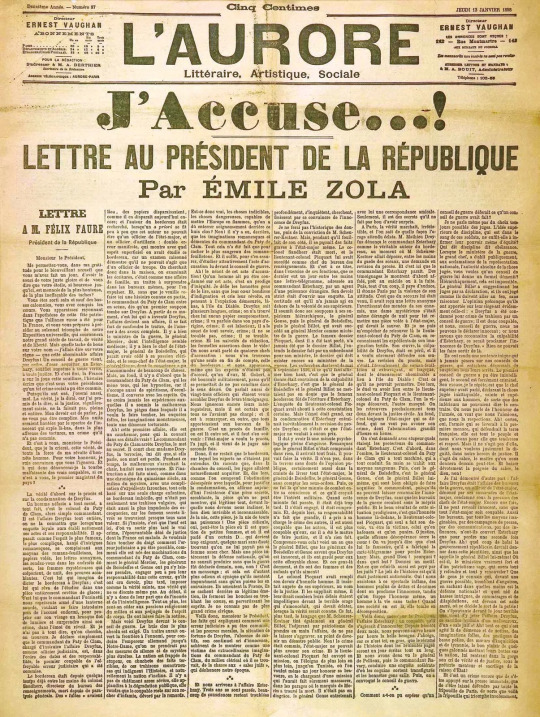

On January 13, 1898, Emile Zola (1840-1902), perhaps most famous 19th century French author, published the most legendary open letter in history, his famous J’Accuse!, in which he accused the government and the military with conspiracy and malicious libel against Dreyfus. (Zola escaped to England after being convicted of libel for writing J’Accuse!) Antisemitic riots broke out throughout France and the Dreyfus Affair became a major public issue. In 1898, the case was reopened and Henry’s forgeries were detected; nevertheless, Dreyfus was again found guilty (September 9, 1899) and was sentenced to five years in prison. This second miscarriage of justice evoked international condemnation and, finally, Dreyfus was pardoned by President Emile Lubet (1906).

The Dreyfus Affair made a powerful impact on the outlook of world Jewry. In particular, Herzl’s confidence in liberalism, badly shaken when he personally witnessed Dreyfus’s disgrace, led him to the Zionist Idea. Jews everywhere realized that if such hatred of Jews could occur in France, the so-called “homeland of liberty,” against a wholly assimilated Jew, then Jews couldn’t be safe anywhere and assimilation was no defense against antisemitism.

Drumont financed La Libre Parole from the proceeds of the publication of his magnum opus, La France Juive (“Jewish France,”1886), which provided his readers with a unified synthesis of antisemitic history. A Voltairean who later became a devout Catholic, he was uniquely able to draw on both Church tradition and the secular Enlightenment in expounding on the “Jewish plot” to dominate France; in promoting the blood libel and the Jewish poisoning of wells; in justifying the Spanish Inquisition as Christianity’s right to protect itself against Jewish treason; and in characterizing the French Emancipation of 1791 as a grievous error and arguing for the exclusion of Jews from society. La France Juive became one of the greatest commercial successes of the 19th century, selling over 100,000 copies in its first year, an almost unimaginable triumph at the time and evidencing his keen understanding of the tenor of the time. Drumont attracted many supporters, and he was one of the primary sources of antisemitic ideas that would later be embraced by Nazism.

Drumont paper token: Verso: Long live Drumont, down with the Jews.”

In this classically antisemitic May 22, 1897 correspondence, Drumont writes from Paris:

What would you like me to write in the album? One date: May 22, 1897… when this album will be studied in a few years, public opinion will undoubtedly change as the result of the work of my colleagues and myself. They will know then, too late I am afraid, that we acted out of affection for our country. We tried to protect our forefathers’ faith, in the land of our forefathers, the purity of the racial line of our forefathers against the Semites [i.e., the Jews] – the invaders and greedy money-chasing people who sought only to harm an innocent and too confident nation that accepted as brothers its merciless enemies.

Drumont’s downfall began when he made the Rothschilds and their banking family a frequent target of his antisemitic diatribes. He was sued by a vice president of the Chamber of Deputies, who had libelously alleged that the VP had taken a bribe from Édouard Alphonse de Rothschild to enact particular legislation favored by Rothschild; unable to provide any evidence to support his allegations, Drumont was incarcerated for three months, fined, and ordered to publish a retraction. Thereafter, his fortunes declined, and he died in obscurity and penury.

Ferdinand Esterhazy (1847-1923), a French traitor who served as a spy for Germany, was the perpetrator of the crime for which Dreyfus had been wrongly accused and convicted. Born in Paris, he was orphaned at an early age after some schooling at the Lycée Bonaparte. After unaccountably disappearing from public notice (1865), he was later found engaged in the Roman legion in the service of the Pope (1869) and, upon entering the French Foreign Legion as an ensign (1870), he began calling himself “Count Esterhazy.” There being a dearth of officers after the French catastrophe in the Sudan, Esterhazy’s military advancement was unusually rapid: lieutenant (1874); captain (1880); decorated officer (1882) – as a member of the Intelligence Department, he inserted in the official records a citation of his grand “exploits in war,” which were later discovered to be false – and major (1892). After the war with Germany, he was employed as a German translator at the Intelligence Office.

Back in Paris, an irresponsible Esterhazy squandered his small fortune and was desperate after having failed to retrieve his fortune in gambling houses and on the stock exchange. In 1892, when the Libre Parole published a series of articles regarding the “preponderance of the Jewish element” in the French army, Captain Crémieu-Foa, a Jewish officer in the French cavalry, challenged Drumont, to a duel and inflicted a slight wound upon him. Esterhazy, who had served as Crémieu-Foa’s second in the duel, pretended that this “chivalrous” role had earned him the enmity of his family and supporters and thus obtained – through, ironically, Zadoc Kahn, the chief rabbi of France – financial assistance from the Rothschilds. Nonetheless, he continued as an ardent supporter of the editors of La Libre Parole.

Notwithstanding a successful military career, he nevertheless considered himself wronged, and he spoke against the entire French army, and even against France herself, for which he predicted and hoped for new disasters. Such a man, lacking even the slightest spark of patriotism, was destined to become the prey of treason and, indeed, he became a paid German spy. Initially, pretending that he received information from Major Henry (who had been his comrade in the French military counter-intelligence section), Esterhazy furnished some interesting information about the artillery, but his information was such that he must have had other informants (who were not necessarily his accomplices.)

Nonetheless, Esterhazy’s information soon became of little importance to the Germans, and the difficulties he endured in getting information were very apparent from the very text of the Bordereau, which was used to incriminate Dreyfus. After Esterhazy was exposed by Colonel Picquart as the true author of the Bordereau, he was forced to undergo a trial behind closed doors by French Military Justice (January 10-11, 1898), where he was unexpectedly acquitted. He fled to the relative safety of Great Britain (September 1898), where he remained for the rest of his life.

Esterhazy’s July 2, 1898 correspondence.

In this July 2, 1898 correspondence, Esterhazy, in deep financial straits, writes:

My dear Emmanuel, In the middle of the painful ordeals I have been enduring for almost nine months and in which, I think, I have plumbed the depths of human cowardice, I have not forgotten your friendship from the first day and the debt I owe to you. You probably know about the separation with my wife, which caused me great pain and great troubles. My wife [ ] with her houses, and the court ruling returned her property and its management back to her, but I am waiting and, yes, I beg you, very confidentially, because I have hidden it from everyone, I am waiting for the end of the Zola trials on the 18th of this month in Versailles… I will reimburse you… You can count on it…

Esterhazy was a compulsive gambler, habitual liar, and a crook who women found entrancing. He liked to pick them up in first-class compartments in trains, and it was on a fateful passage from Le Havre to Paris that he met and won Marguerite Pays, the paramour who helped him forge documents in the Dreyfus Affair. Esterhazy’s wife – whom he described as a “spendthrift” and “ninny” – divorced him in 1899. She had stood bravely by him, but he repaid her with neglect, abuse, and flagrant unfaithfulness. Matters reached a crisis when Esterhazy sought to introduce his young daughter to Marguerite, a gratuitous insult which stung Madame to the point where she decided to air her grievances in court, which led to the odious airing in Paris of their notorious domestic relations, as the divorce action brought as much ignominy upon the Commandant as the Dreyfus Affair itself.

The tribunal in the divorce case assigned temporary custody of the children to their mother and ordered Esterhazy to pay 600 francs a month in alimony for the duration of the lawsuit. Esterhazy’s poverty was so dire that, in a letter to his divorced wife, he wrote that he had had nothing to eat for two days. One of the key charges in the Zola trial was that Zola had defamed Esterhazy by claiming that his court-martial (in which he was fully exonerated of any wrongdoing) was fixed and, as we see from our letter, Esterhazy hoped that the damages he would be awarded in that case would relieve his of his economic duress and permit repayment of the loan he was seeking. In fact, Zola was fined 3,000 francs but, with his appeal pending, he escaped France for England.

When, through the Bordereau, French military intelligence became aware in September 1894 of a spy within the army, Armand du Paty de Clam (1853-1916), a devout antisemitic Catholic loyalist and a major with the French General Staff, became deeply involved in the investigation to identify the traitor, due principally to his alleged “expertise” in handwriting analysis, although he was only – at best – an amateur. A brief three-week investigation identified approximately six suspects, but the pompous and patrician du Paty de Clam decided that the Jew Dreyfus was the criminal.

On October 15, 1894, du Paty de Clam effected an ambush of Dreyfus by summoning him to a meeting also attended by two civilian police detectives and a French military intelligence officer, during which he faked an injury to his writing hand, asked a bewildered Dreyfus to take dictation, and proceeded to dictate the precise words written in the Bordereau. After comparing Dreyfus’s writing through the lens of unadulterated antisemitic animus, he ignored warnings from professional handwriting experts – including a conclusion from Alfred Gobert, a leading expert and graphologist for the Bank of France, that “there were numerous and important disparities that had to be taken into account” – and announced that Dreyfus had written the Bordereau. He charged the Jewish officer with high treason and offered him the “honorable” way out: he gave him a revolver with a single bullet in the chamber. When Dreyfus proclaimed his innocence and refused to take his own life, he was transferred to Major Henry who, according to plan, had been waiting in an adjacent room.

The focus of the miscarriage of justice against Dreyfus has always been upon the fraudulently-obtained Dreyfus handwriting sample, but it may have been du Paty de Clam’s bogus telegram that was outcome determinative in Dreyfus’s conviction by the tribunal. In any event, du Paty de Clam was later promoted to lieutenant-colonel for his “excellent work” in the Dreyfus prosecution and conviction.

In this June 2, 1909 correspondence on his infantry letterhead – notwithstanding the fact that he had been earlier discharged from the military – du Paty de Clam writes regarding a letter he had submitted to Le Siecle, a French newspaper published from 1836-1932.

I would be grateful if you could have a search made to find out if the “Siecle” has published a letter from me in one of the issues after last May 27. Receive, sir, my sincere greetings…

Auguste Mercier (1833-1921), the French Minister of War, was one of the great villains of the Dreyfus Affair; in his famous J’Accuse, Zola accused him of “having made himself an accomplice in one of the greatest crimes in history, probably because of a weak mind.” Mercier was the first public Dreyfus accuser (November 28, 1894); he arrested Dreyfus and coordinated the anti-Dreyfusards throughout the entire Affair; he masterminded the creation of the sham secret dossier handed furtively to the judges in the first Dreyfus court-martial to influence their decision; and even after he was no longer Minister (as of January 24, 1895), he directed the witnesses for the prosecution at the Rennes trial. He gave virulent and perjured testimony against Dreyfus at every trial in the matter and, though he was only a witness, he sought to act as prosecutor by introducing evidence on his own; he (unsuccessfully) attempted to blackmail Dreyfus’s lawyer, Labori, by alleging that he has a letter from Esterhazy compromising Labori’s daughter; and he remained an implacable foe of Dreyfus, even after the Jewish officer was pardoned.

When the Dreyfus mater first came to Mercier’s attention, he initially felt that all the evidence had been concocted, and he knew that Dreyfus could not have masterminded such a deception. However, he was under significant pressure from the press and the army, which now stood to redeem the honor it lost in the miserable defeat by convicting the spy responsible for it. The day before he was to decide if the evidence against Dreyfus warranted a trial, Mercier re-examined the evidence and, once again, had his doubts; however, the next day, there appeared in one of the leading papers in Paris that Mercier was in the pay of the Jews and therefore would not order the trial. To exonerate himself from that accusation, he threw Dreyfus to the wolves and ordered the trial; declared that the evidence against Dreyfus was beyond doubt and that his guilt was certain; and publicly and vociferously alleged that Dreyfus had committed “treason.”

Dreyfus’s conviction based only upon the secret file set up another problem: Mercier was the one who had approved submission of the file, which meant that the army had approved it; were there to be a second trial where Dreyfus would be acquitted, the army would stand exposed for its perfidy and French pride would be devastated. Indeed, Dreyfus would be tried a second time, and there would be other trials against Dreyfus supporters until as late as 1906; however, in none of these trials was the “secret file” allowed to be seen by the defendants and their attorneys, as the French authorities claimed that the honor of France was at stake.

Testifying in 1904 before the Court of Cassation (French for “the Court of Abrogation,” the highest court of criminal and civil appeals in France with the power to quash decision of the lower courts), Mercier again perjured himself by denying the existence of a document written by a foreign sovereign implicating Dreyfus. However, in 1906, speaking of the secret dossier given to the court martial, public prosecutor Baudoin evoked a “monstrous violation of the inalienable rights of the defense” and emphasized Mercier’s responsibility in preventing the disclosure of the dossier. Nonetheless, Mercier remained the hero of the anti-Dreyfusards and he kept his seat in the Senate until January 1920.

Mercier’s 1906 correspondence.

In this November 2, 1906 correspondence on his Senate letterhead, Mercier writes:

I thank you for your kind words, which gladdened me. I will come to your house today between 2:00 a.m. and 3:00 a.m. In the event that I do not find you there, I will leave this there tomorrow at the same time, unless you advise otherwise. As far as the Henry subscription, I think it is appropriate to put Mrs. Henry in possession of what remains of the money as soon as possible. We could therefore, if you agree, convene the Commission “La Libre Parole” on Wednesday afternoon (both the Senate and the House in session) next week at the time that will suit you. Please accept, Sir, the expression of my most sympathetic feelings.

Henry, the forger of the Bordereau that launched the entire Dreyfus Affair, was found dead in his cell on the morning of August 31, 1898 and, although no razor was found, his death was declared a suicide. Our correspondence refers to Drumont’s La Libre Parole’s sponsor of a public subscription for Henry’s widow, in which the donors were invited to vent all their anger against Jews.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Noah Berlatsky at Everything Is Horrible:

In the Anglophone world, the intertwined issues of Jewish identity and antisemitism are connected in public memory obsessively, and almost solely, to the Holocaust. Occasionally, perhaps, people also mention the blood libels of the Middle Ages, or the pogroms of Eastern Europe.

The Dreyfus Affair, however, is almost entirely forgotten. It is not a moment revisited in movies or television shows. Politicians do not reference it; there are no public museums in its memory; it is not a part of school curriculum. Even Jewish people hardly discuss it. I doubt one in ten Americans, of any ethnicity or religion, could even tell you vaguely who Alfred Dreyfus was. The disappearance of Dreyfus memory is a real loss. That’s not because we need to remember antisemitism. We do, as I’ve mentioned, remember the Holocaust. The Dreyfus Affair, though, was a victory over antisemitism, and a victory particularly for the diaspora, in a way that World War II was not. The Holocaust has largely been interpreted as an object lesson in the untenability of the diaspora, and the necessity of a Zionist Jewish ethnonationalism. The outcome of Dreyfus’ story is considerably more ambivalent. As such, it is worth revisiting at a moment when Zionism is busily and horrifically delegitimizing itself.

The Affair

Since, the outlines of the Dreyfus Affair are probably little known to readers, it’s worth covering them briefly. My discussion here, and throughout the essay, is mostly based on Maurice Samuels new excellent biography/history, Alfred Dreyfus: The Man At the Center of the Affair, part of the Jewish Lives series. During the French Revolution, France put into practice its new ideals of liberty and equality by, among other things, making Jewish people full citizens of the republic. After legislation in 1791, Jews were suddenly—for the first time in any European country��able to live where they wished, attend the best schools, and work in every profession. The results were immediate and dramatic. Jews made rapid gains in political and economic life; some became quite wealthy and influential.

Among those wealthy Jews was the Dreyfus family. Alfred Dreyfus, born 1859, grew up, like most French Jews, with a passionate commitment to the French nation and to the principles of equality which had liberated them. Determined to serve his country, Dreyfus attended the French military academy. He excelled and became arguably the first Jewish officer ever on the General Staff. His future seemed bright. And then, it all fell apart. In 1894, the French army discovered that there was a traitor on the General Staff who had been passing top secret information to the Germans. Dreyfus was accused of treason. The evidence against him was weak to nonexistent; his handwriting was said to match that on the recovered documents, even though it obviously did not. Nonetheless, he was arrested, tried in a sham military trial, and sentenced to life imprisonment. He was sent to the horrific penal colony on Devil’s Island in French Guiana. He endured tortures almost certainly intended to kill him. His wife, contrary to law, was not allowed to accompany him. Dreyfus was singled out because he was Jewish. The generals, once they had begun down the path of antisemitism, decided they could not turn back without undermining respect for the military. They forged more evidence, and stonewalled investigations as long as possible.

The Affair polarized sentiment in France, both on Dreyfus and on the place of Jews in French society. Liberal intellectuals like Émile Zola who believed in the Republic and a forward-looking, cosmopolitan, free and equal France sided with Dreyfus and demanded a new trial. The Catholic Church, the military, antisemites, and proto-Vichyites insisted that Dreyfus was guilty and should be punished—or, really, insisted that as a Jew he should be punished whether he was guilty or not. The hatred of Jews erupted into antisemitic riots throughout the country; Jews were beaten, their homes burned, their businesses destroyed. Several Jewish people were killed in Algiers, where there were violence against Jews occurred almost daily in 1898. Dreyfus was brought back for a new trial in 1899; he was convicted again despite overwhelming evidence in his favor, and eventually exonerated completely in 1906. He was restored to the rank of Major, and served with distinction in World War I. He died in 1935. Jewish people in France still leave stones on his grave.

[...] It wasn’t just Dreyfus and Jewish people who fought for Dreyfus though. The Affair energized every corner of the left, calling them almost uniformly to their best selves. Zola, for example, believed in a number of antisemitic stereotypes at the beginning of the Affair; his first article on the case argued that Jewish people had an innate talent for making money. From that inauspicious beginning he quickly became one of the most passionate gentile opponents of antisemitism in history; his famous 1898 pamphlet J’accuse was a devastating denunciation of the military coverup intended to force a number of generals to sue for libel. They did, and Zola was forced to flee the country—but not before opening the case again and ensuring Dreyfus’ retrial.

The political left in France was also, initially, wary of standing with Dreyfus because of antisemitism. For many socialists, Jewish people symbolized the banking industry and the upper class. Dreyfus, a wealthy Jew serving in the military, seemed the wrong man to rally working class parties. But eventually Socialist leader Jean Jaurès, and others in his party, recognized that Dreyfus had become the man, and the issue, on which Catholic monarchist and capitalist forces had decided to fight for France’s soul. In 1898 Jaurès gave a speech in which he denounced antisemitism as a threat to France; shortly thereafter he published a book defending Dreyfus and presenting the Affair as a matter of socialist solidarity. Some on the left refused to join Jaurès, and the Socialists split. But as Samuels’ biography of Dreyfus notes, “Jaurès helped ensure that a large part of the political left in France would align itself with republican values and against antisemitism for decades to come.”

Noah Berlatsky wrote in his Everything Is Horrible Substack about how the Dreyfus Affair served as a victory against fascism and antisemitism, and how it gave the left a tool to fight back against oppression.

#Dreyfus Affair#World History#Judaism#Zionism#Antisemitism#France#Alfred Dreyfus#Émile Zola#Jean Jaurès#Noah Berlatsky#Europe

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy, spy for the German Empire, actual perpetrator of the act of treason of which Captain Alfred Dreyfus was wrongfully accused in 1894

French vintage postcard

#french#ferdinand walsin esterhazy#treason#carte postale#walsin#sepia#the german empire#esterhazy#photo#alfred dreyfus#postkarte#tarjeta#accused#perpetrator#ansichtskarte#alfred#wrongfully#postkaart#ephemera#postcard#vintage#actual#historic#captain#postal#german#1894#briefkaart#ferdinand#empire

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ben Shahn, "The Dreyfus Affair", 1930

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

« L’intervention d’un romancier, même fameux, dans une question de justice militaire m’a paru aussi déplacée que le serait, dans la question des origines du romantisme, l’intervention d’un colonel de gendarmerie. »

Ferdinand Brunetière (1848-1906),

Après le procès (1898)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

so i’ve just finished reading the ‘Oppenheimer trial’ section of the biography, which more or less takes up two-fifths of the book and (*… a scandalised, incredulous sigh), what you’re assailed with is a sort of endless series of increasingly rank, unlawful, calumnious, – i want to stress this also: above all fucking embarrassing – and indefatigably unscrupulous acts of towering corruption that by the time it’s all over the only thing I’m able to compare it to is the various repellent enormities you defeatedly read about in any half reputable history of the Soviet Union

it seems to me at least that Clio, the muse of history, loves her a bit of irony, eh?

#even Lindsay Shepherd would have to say old Robert was done badly#Oppenheimer#american prometheus#soviet union#history#lewis strauss mate you are one horrible little fuck#personal notes#alfred dreyfus#n.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tour de france: la nascita di un mito

Il Tour de France, meglio definito anche come “Grande Boucle“: la più grande manifestazione sportiva del panorama ciclistico internazionale, si svolge ogni anno lungo le strade di Francia. Nasce nel 1903 da un’idea di Henri Desgrange, nel corso degli anni è diventato l’evento di spicco del calendario professionistico UCI Word Tour. Continue reading Tour de france: la nascita di un mito

#Alfred Dreyfus#antidreyfusardi#Bernard Hinault#Chris Froome#ciclismo internazionale#Cima della Bonette#classifica generale#Col d&039;Aspin#Col de Joux Plane#Col de l&039;Iseran#Col de Peyresourde#Col de Portet d&039;Aspet#Col de Vars#Colle d&039;Aubisque#Colle dell&039;Agnello#Colle della Maddalena#Courchevel#Eddy Merckx#epiche battaglie#Eugène Christophe#Fausto Coppi#gare di ciclismo#Geo Lefèvre#Gino Bartali#Grande Boucle#grandi campioni#guerre mondiali#Henri Desgrange#Hyppolite Aucoutier#Jacques Anquetil

0 notes

Text

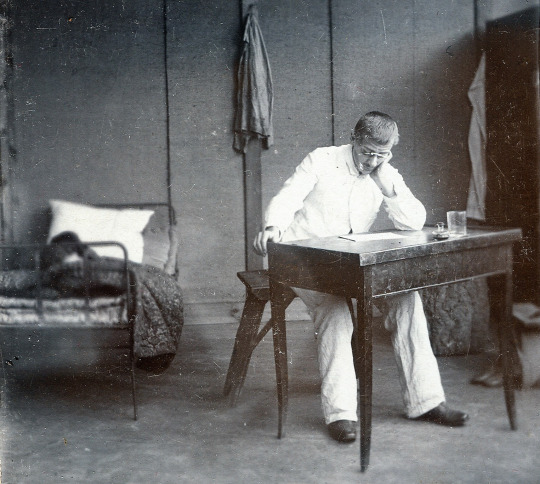

Alfred Dreyfus in his room on Devil's Island in 1898,stereoscopy sold by F. Hamel, Altona-Hamburg...; collection Fritz Lachmund

1 note

·

View note

Text

Baela snaps with a clever reply! BAELA VS. THE GEEZERS OF THE BLACK COUNCIL

[+] BAELA TARGARYEN [GIF Collection] ✨ [+] RHAENYS TARGARYEN [GIF Collection] ✨ [+] ..more on “House of the Dragon” 🔥

#House of the Dragon#Rhaenys Targaryen#Baela Targaryen#Eve Best#Bethany Antonia#Nicholas Jones#Jamie Kenna#James Dreyfus#Alfred Broome#Bartimos Celtigar#Gormon Massey#Game of Thrones#HOTD#GOT#Dragonstone#Quotes

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

by Brendan O'Neill

Now, not even Israel’s most fervent defenders would describe it as ‘spotless’. Like every state, it makes mistakes, it does wrong. But the showtrial of the Jewish State eerily echoes the showtrial of the Jew Dreyfus. Again we see the deployment of ‘lurid imagination’, where every single thing Israel does is pored over and judged nefarious. Again we see men – or in this case, nations – that are ‘lost in debts and crime’ projecting their own sense of guilt on to a Jewish scapegoat. And again we see not one nation this time, but many nations seeking to distract attention from their own inner turmoil through the creation of a spectacle of accusation – only now it’s not a Jew in the dock; it’s the entire Jewish nation.

We have heard quite enough of your lurid accusations against Israel. Now it’s time you heard ours against you. I accuse South Africa of joining the holy war against Israel in order to cynically curry favour with the woke elites of the West. In order to try to repair its global image as a just, radical nation despite its cataclysmic failing of its own population who still await the enrichment and equality they were promised following the fall of Apartheid 30 years ago. I accuse Iran of backing the legal crusade against Israel as a furtherance of its violent anti-Semitism. As yet another opportunity to defame and isolate the Jewish State in order that the Jews there might feel compelled to leave.

I accuse Turkey of backing the showtrial in order to disguise its own past genocidal crimes. In order to pool its genocidal guilt, and project it on to others, in particular the supposedly evil ‘Zionist entity’. I accuse Turkey of spying in these kangaroo proceedings an opportunity to rearrange power relations in the Middle East to its own tyrannical advantage. To strengthen the Turkey-Iran alliance on the back of what they hope will be the international court’s reprimand of the Jewish State. I accuse Turkey of sacrificing the safety of Jews in Israel at the altar of its own demented regional ambitions.

And I accuse the Western left of being the running dogs of all this global Israelophobia. Of forfeiting their right to be treated as serious moral actors by aligning with the demagogues, Islamists and outright racists who have dragged the world’s only Jewish nation to court on the most trumped-up charge imaginable. Of flagrantly abandoning their supposed commitment to anti-racism by whitewashing Hamas’s orgy of racist violence that gave rise to the current war. And of emboldening the fascists of Hamas by promoting the libel that says Israel is a genocidal state. After all, if Israel is guilty of the worst crime known to man, why should Hamas not attack it again, and again, and again, until the Nazi-like threat it poses to the Palestinian people has been eradicated? I accuse you of giving moral succour to fascists.israe

#genocide#international court of justice hypocrisy#captain alfred dreyfus#dreyfus affair#j'accuse#turkey#iran#south africa#israel

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alfred Dreyfus

A French artillery officer of Jewish ancestry from Alsace

Alfred Dreyfus was a French artillery officer of Jewish ancestry from Alsace whose trial and conviction in 1894 on charges of treason became one of the most polarizing political dramas in modern French history. The incident has gone down in history as the Dreyfus affair, the reverberations from which were felt throughout Europe. It ultimately ended with Dreyfus' complete exoneration.

Born: October 9, 1859, Mulhouse

Died: July 12, 1935, Paris

Children: Pierre Dreyfus, Jeanne Dreyfus

Spouse: Lucie Dreyfus (m. 1891–1935)

Place of burial: Montparnasse Cemetery, Paris

Parents: Raphael Dreyfus, Jeannette Dreyfus

Dreyfus affair

Dreyfus affair, political crisis, beginning in 1894 and continuing through 1906, in France during the Third Republic. The controversy centred on the question of the guilt or innocence of army captain Alfred Dreyfus, who had been convicted of treason for allegedly selling military secrets to the Germans in December 1894. At first the public supported the conviction; it was willing to believe in the guilt of Dreyfus, who was Jewish. Much of the early publicity surrounding the case came from anti-Semitic groups (especially the newspaper La Libre Parole, edited by Édouard Drumont), to whom Dreyfus symbolized the supposed disloyalty of French Jews.

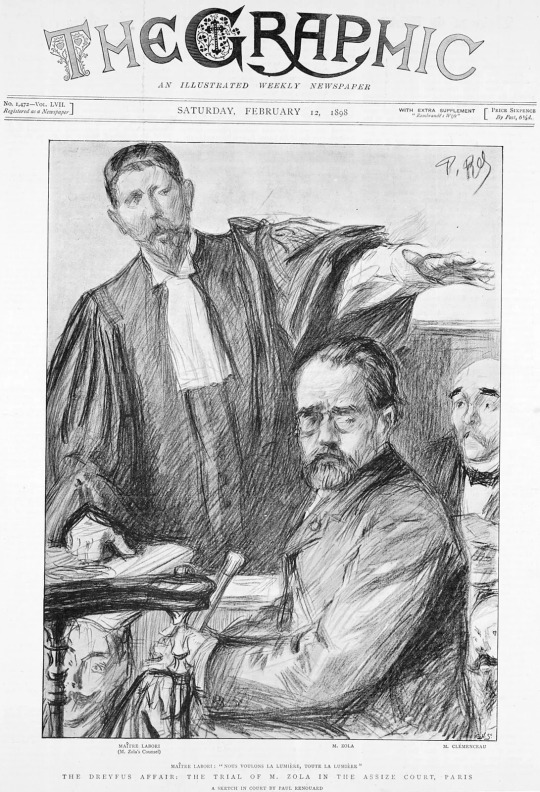

Zola, Émile: Newspaper depiction of Émile Zola in court during his trial for defamation of the French military, 1898.

The effort to reverse the sentence was at first limited to members of the Dreyfus family, but, as evidence pointing to the guilt of another French officer, Ferdinand Walsin-Esterhazy, came to light from 1896, the pro-Dreyfus side slowly gained adherents (among them journalists Joseph Reinach and Georges Clemenceau—the future World War I premier—and a senator, Auguste Scheurer-Kestner). The accusations against Esterhazy resulted in a court-martial that acquitted him of treason (January 1898). To protest against the verdict, the novelist Émile Zola wrote a letter titled “J’accuse,” published in Clemenceau’s newspaper L’Aurore. In it he attacked the army for covering up its mistaken conviction of Dreyfus, an action for which Zola was found guilty of libel.

The second court-martial of Alfred Dreyfus, illustration from Vanity Fair, Nov. 23, 1899.

By the time of the Zola letter, the Dreyfus case had attracted widespread public attention and had split France into two opposing camps. The anti-Dreyfusards (those against reopening the case) viewed the controversy as an attempt by the nation’s enemies to discredit the army and weaken France. The Dreyfusards (those seeking exoneration of Captain Dreyfus) saw the issue as the principle of the freedom of the individual subordinated to that of national security. They wanted to republicanize the army and put it under parliamentary control.

Front page of the newspaper L'Aurore, January 13, 1898, with the open letter “J'accuse” written by Émile Zola about the Dreyfus affair....(more) -From L'Aurore, January 13, 1898

From 1898 to 1899 the Dreyfusard cause gained in strength. In August 1898 an important document implicating Dreyfus was found to be a forgery. After Maj. Hubert-Joseph Henry of the intelligence section confessed to fabricating the document in order to strengthen the army’s position, revision was made almost certain. At the same time, the affair was becoming a question of vital concern to politicians. The republican parties in the Chamber of Deputies recognized that the increasingly vocal nationalist right posed a threat to the parliamentary regime. Led by the Radicals, a left-wing coalition was formed. In response to continuing disorders and demonstrations, a cabinet headed by the Radical René Waldeck-Rousseau was set up in June 1899 with the express purpose of defending the republic and with the hope of settling the judicial side of the Dreyfus case as soon as possible. When a new court-martial, held at Rennes, found Dreyfus guilty in September 1899, the president of the republic, in order to resolve the issue, pardoned him. In July 1906 a civilian court of appeals (the Cour d’Appel) set aside the judgment of the Rennes court and rehabilitated Dreyfus. The army, however, did not publicly declare his innocence until 1995.

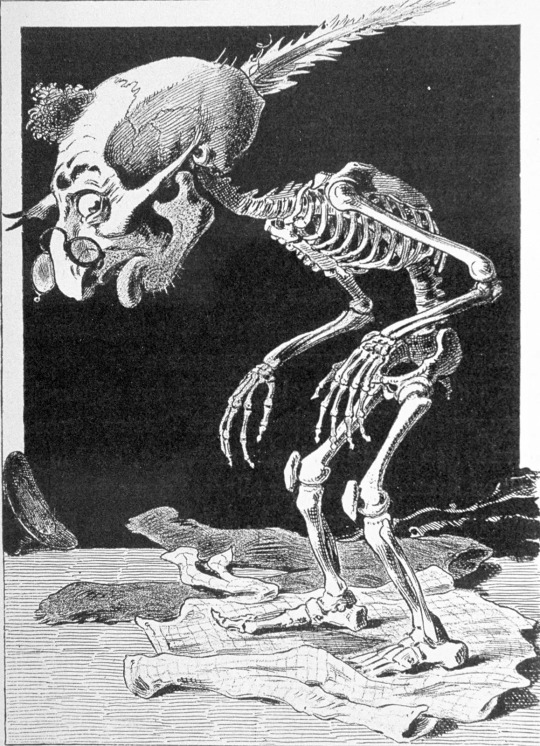

Anti-Semitic caricature: Caricature from the anti-Semitic Viennese magazine Kikeriki. Its caption reads: “In the Dreyfus Affair, the more that is exposed, the more Judah is embarrassed.”...(more) © United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

With the Dreyfusards in the ascendant, the affair marked the start of a new phase in the history of the Third Republic, a phase in which a series of Radical-led governments pursued an anticlerical policy that culminated in the formal separation of church and state (1905). By intensifying antagonisms between right and left and by forcing individuals to choose sides, the case made a lasting impact on the consciousness of the French nation.

Félix Faure | French Republic, Politics, Legacy | Britannica

In 1894, this made the French Army's counter-intelligence section, led by Lieutenant Colonel Jean Sandherr, aware that information regarding new artillery parts was being passed to Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen, the German military attache in Paris, by a highly placed spy most likely on the General Staff. Suspicion quickly fell upon Dreyfus, who was arrested for treason on 15 October 1894.

Alfred Dreyfus in his room on Devil's Island in 1898, stereoscopy sold by F. Hamel, Altona-Hamburg…; collection Fritz Lachmund

On 5 January 1895, Dreyfus was summarily convicted in a secret court martial, publicly stripped of his army rank, and sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil's Island in French Guiana. Following French military custom of the time, Dreyfus was formally degraded (cashiered) by having the rank insignia, buttons and braid cut from his uniform and his sword broken, all in the courtyard of the École Militaire before silent ranks of soldiers, while a large crowd of onlookers shouted abuse from behind railings. Dreyfus cried out: "I swear that I am innocent. I remain worthy of serving in the Army. Long live France! Long live the Army!...Continue

The affair ultimately ended with Dreyfus' complete exoneration.

Dreyfus died in Paris aged 75, on 12 July 1935, exactly 29 years after his exoneration.

Alfred Dreyfus - Wikipedia

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alfred Dreyfus on a German vintage postcard

#vintage#dreyfus#tarjeta#briefkaart#postcard#photography#postal#carte postale#alfred#german#sepia#ephemera#historic#alfred dreyfus#ansichtskarte#postkarte#postkaart#photo

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

And if you want to know the event that convinced Herzl that Jews need to return to Israel, it was THIS SHIT -- the Dreyfus Trial.

A bunch of French goyim in the military framed an innocent Jewish officer, Alfred Dreyfus, for crimes that the French officers themselves had committed -- and the French kangaroo court wrongly convicted Dreyfus for these goyishe men's crimes.

Herzl was a journalist covering the Dreyfus Trial, and after seeing the lengths that antisemites will go in order to destroy Jewish people's lives, he knew that it was essential for Jews in European diaspora to return to Israel.

The tragedy is that the British prevented the establishment of the State of Israel before 1948. The British established the British Mandate in 1923, after defeating the Ottoman Empire in World War I. If the State of Israel had been established in 1938 instead of 1948, MILLIONS of Jews in European diaspora would have escaped the Nazis and their war machine of death.

youtube

class is in session 👏 go off matthew

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recently the French news cycle has been dominated by us patting ourselves on the back from refusing a racist law project from some dickhead in parliament, and a frankly shameful debacle where a teacher took their students to the Louvre and took them without warning to see a painting featuring naked people, with the students being eleven to twelve years old in that context. I invite you to read about it yourself although you should keep in mind that a lot of sources show a very strong bias in their language describing the event.

What we see with that whole nonsense is that 130y after Alfred Dreyfus' trial, we still have the proceedings over controversial facts and statements be ruled over by some clique with obvious conflicts of interest passing judgement by telling us that no everything's fine we swear, it's the minorities that we need to worry about. A teacher shows artistic nudes to 12yo's with no warning but no no it's their fault you see, and the fault of their religion, this eternal enemy of the Republic (except when it's fairweather catholicism)/s. The students complain that this is part of a pattern of hostility from said teacher, but it's okay because the teachers tell you that it's not. And now the minister of education wants to punish the students. Classy.

It's honestly not hard to see a pattern of abuse towards these kids and we don't need to have this teacher personally involved in it either, because if even a single student in this class was Muslim, or Jewish, or literally any other religion than Christian, there are laws that should be unconstitutional in nature that already bars them from even harmless outward displays of their religion, because of a fundamentally moronic, stunted understanding of what secularism and the separation of church and state was about. It was supposed to stop discrimination, but instead it hits on the head any and everything that might stick out to a white Christian point of view with absolutely no self-reflection on how hypocritical it is. France has had a deeply religious culture for as long as it existed, our national myth STARTS with our people's conversion to Christianity, but because it is our culture and we're used to it we do not see it, we do not question it, and any attempt to point it out is an attack on the values of the Republic, you filthy non-assimilated foreigners. Ignore over half of our holidays being literal Christian holy days, all of our stores legally having to close on sundays and wearing cross pendants in school literally never being prosecuted, we're so fucking secular it's beautiful.

Mind you this is borderline irrelevant in this context though, because a teacher decided to shoulder the responsibility to show nudity to children, not all of whom were Muslims and they were obviously made uncomfortable by the experience. There's probably an age at which one can expect students to look at tits in a painting and be able to contextualize them with their art history lesson, I'm going to be honest though it's not gonna be twelve years old. Reframed without the racist "their obscurantist beliefs can't handle our beautiful art of chubby ladies in what I can only assume are poses an Italian man four hundred years ago thought were sexy", it's not an attempt against the sanctity of the republic not to show tits to children without warning them and their parents. But apparently some fucking dullard did a dumb, and rather than address it or any of its systemic issue the French education system is circling the wagon and shitting on its students twice as hard.

“At French schools, we do not challenge authority, we respect it! At French schools, we do not contest secularism, we respect it! ! At French school, we don't look away from a painting, we don't cover our ears in music class, we don't wear religious dress, in short, in French schools we do not negotiate the authority of the teacher nor the authority of our rules and our values!”.

--Gabriel Attal, French minister of education/Macron simp, showing how becoming minister at age 34 might be a bad idea and an indictment to the institution you claim to represent by ignoring the past some two hundred and forty years of French history.

"Shut up and do as we say, after all the French system as an impeccable record of mediocrity so clearly we're doing everything to merit your obedience !!"

I cannot stress this enough, kids this age are NOT COMFORTABLE WITH NUDITY AND SEXUAL THEMES, it is not a purely religious thing and not all kids who complained were Muslim. The school and media are brushing over that because it doesn't fit their racist framing job, because it would not be convenient for them to report the news accurately because it would expose how the education system in France is rotten from top to bottom, from underpaid teachers who stopped giving a shit all the way to a political appointee minister who couldn't pour water out of a boot if the instructions were written on the heel.

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you want to see how History is repeating itself read about the Alfred Dreyfus Affair of 1894 ...

14 notes

·

View notes