#Alex Samuels and Geoffrey Skelley

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Link

via Politics – FiveThirtyEight

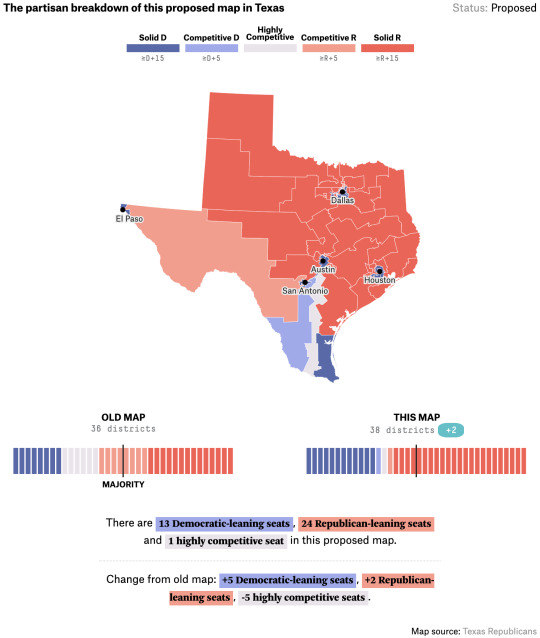

On Monday, Texas lawmakers gave a first glimpse at what the state’s new congressional districts may look like. The redrawn map was highly anticipated given that Texas gained two additional congressional seats — the most of any state — during the reapportionment process and because Republicans are fully in control of the state’s redistricting process. Yet the new map, if passed, would not substantially alter the topline partisan breakdown of Texas’s seats. It appears that Republican mapmakers prioritized defending the GOP’s current seat advantage over trying to significantly expand it.

Overall, this map creates 24 solid or likely Republican seats, 13 solid or likely Democratic seats and one swing seat in the Rio Grande Valley. (The state’s two new districts will be placed in the Austin and Houston metropolitan areas, as those two areas fueled much of the state’s population growth since 2010.) But this isn’t that much different than what Texas’s map currently looks like: At present, the delegation is made up of 23 Republicans and 13 Democrats.

This is still a very good map for Republicans, though, because mapmakers strengthened the GOP’s advantage in the state by making a number of potentially vulnerable seats held by Republicans much redder, with the newest Houston-area seat also drawn so that it’s favorable to Republican candidates. As the table below shows, the current map has 11 Republican incumbents in seats that were less than 20 points more Republican than the country as a whole, according to FiveThirtyEight’s partisan lean metric.1 But on the new map, all but one Republican-held seat would be R+20 or stronger for the GOP.

GOP incumbents are protected in Texas’s new proposed map

Change in partisan lean in Texas congressional districts held by Republicans, from the current map to the first draft plan proposed by the Texas Legislature

District Partisan lean GOP Incumbent Old New Old New Change Beth Van Duyne TX-24 TX-24 R+3.5 R+22.3 R+18.8 Dan Crenshaw TX-02 TX-38 R+9.1 R+26.6 R+17.6 John Carter TX-31 TX-31 R+11.2 R+27.3 R+16.1 Roger Williams TX-25 TX-25 R+16.4 R+31.8 R+15.4 Troy Nehls TX-22 TX-22 R+8.3 R+23.7 R+15.3 Michael McCaul TX-10 TX-10 R+9.2 R+24.5 R+15.2 Chip Roy TX-21 TX-21 R+10.2 R+24.5 R+14.2 Van Taylor TX-03 TX-03 R+10.5 R+23.6 R+13.0 Randy Weber TX-14 TX-14 R+24.6 R+35.3 R+10.6 Jake Ellzey TX-06 TX-06 R+11.2 R+21.0 R+9.8 Pete Sessions TX-17 TX-17 R+18.2 R+26.2 R+7.9 Tony Gonzales TX-23 TX-23 R+5.1 R+12.8 R+7.7 Michael Burgess TX-26 TX-26 R+23.3 R+26.4 R+3.0 Jodey Arrington TX-19 TX-19 R+52.1 R+53.3 R+1.3 Louie Gohmert TX-01 TX-01 R+50.3 R+49.9 D+0.4 Michael Cloud TX-27 TX-27 R+28.8 R+27.8 D+1 Lance Gooden TX-05 TX-05 R+29.8 R+27.0 D+2.8 Kay Granger TX-12 TX-12 R+30.2 R+24.3 D+5.9 Brian Babin TX-36 TX-36 R+50.7 R+34.9 D+15.8 Kevin Brady* TX-08 TX-02 R+49.7 R+29.9 D+19.8 Ronny Jackson TX-13 TX-13 R+65.9 R+45.1 D+20.8 August Pfluger TX-11 TX-11 R+64.3 R+41.0 D+23.3 Pat Fallon TX-04 TX-04 R+56.3 R+29.7 D+26.7

*Incumbent is retiring.

Incumbents were placed in the district that contains the largest population share of their old district. They may not necessarily seek reelection in that district.

Partisan lean is the average margin difference between how a state or district votes and how the country votes overall. This version of partisan lean, meant to be used for congressional and gubernatorial elections, is calculated as 50 percent the state or district’s lean relative to the nation in the most recent presidential election, 25 percent its relative lean in the second-most-recent presidential election and 25 percent a custom state-legislative lean.

Given that the GOP controls the redistricting process in Texas, it might seem strange that it wasn’t more aggressive in trying to flip a seat or two held by Democrats. But population growth and demographic shifts in Texas have arguably benefited Democrats so significantly that Republican mapmakers were mostly left playing defense — concerned that some GOP incumbents might soon become vulnerable.

At the top of that list is Rep. Beth Van Duyne, the only Texas Republican defending a seat that President Biden carried in 2020. The new map lines, however, would shift Van Duyne’s district between Dallas and Fort Worth nearly 20 points to the right, meaning that she likely has far more to worry about in a primary than in a general election now after winning by only 1.3 points last November.

Three other Republican incumbents in seats that were less than R+10 also saw their districts move at least 15 points to the right. Rep. Dan Crenshaw ranks among these members, although it’s not clear which seat he may run in: About one-third of his current district is in the new 38th District, but the same is true of the new 2nd District, too, which may also be open, considering Rep. Kevin Brady of the current 8th District is retiring. Either way, Crenshaw — a rising star in the GOP — would be far safer than he is now.

Rep. Tony Gonzales of the 23rd District is the only Republican incumbent who wouldn’t end up in a seat that’s at least R+20, but his perennial battleground district would be reforged into a relative GOP stronghold: His district would be R+13 under the new lines. Like Van Duyne, Gonzalez would breathe far easier under this new map, after he only won by 4 points in 2020.

In order to make many of these seats safer for Republicans, GOP lawmakers moved more Democratic voters into seats that the GOP had previously targeted but now seem to have abandoned. For example, the seat held by Democrat Lizzie Fletcher, who unseated a Republican incumbent in 2018, would go from D+1 to D+25. Meanwhile, the Dallas-area seat represented by Democrat Colin Allred, who similarly ousted a Republican incumbent in 2018, would go from D+2 to D+25. It’s a similar story for almost every other Texas Democrat under this plan. (In some instances, Republican mapmakers also made some super-red seats a slightly paler shade, “unpacking” some GOP voters to boost Republican-held seats. For instance, Rep. Van Taylor’s 3rd District outside of Dallas shifted east to take some red turf from Rep. Pat Fallon’s 4th District.)

One of the biggest takeaways from this map is that almost every seat — Democratic or Republican — would be uncompetitive at its baseline. All but two seats would lean at least 10 points more Democratic or Republican than the country as a whole.

And it’s heavily Hispanic South Texas that holds both of those exceptions. This is a potentially important development as that region might hold opportunities for the GOP since Biden performed worse there than past Democratic presidential candidates. Most notably, the 15th District, represented by Democrat Vicente Gonzalez, would become more Republican-leaning on the new map. He was already facing a difficult reelection bid, as he narrowly won his 2020 race by 3 percentage points after winning reelection by 21 points in 2018. But now under the new map, his district would go from D+2 to evenly split. Meanwhile, Rep. Henry Cuellar’s 28th District would actually become slightly bluer — it only moved from D+4 to D+7 — and could be in play in 2022. (Rep. Filemon Vela’s 34th District doesn’t fall neatly into this category because it went from D+5 to D+17, but it is the other border seat in Texas, and it seems to have gotten a little friendlier toward Democrats, although Vela won’t seek reelection.)

Another notable change under the new map is that it would result in a smaller share of districts with Hispanic majorities despite the addition of two new congressional districts. This could make the map vulnerable to a racial gerrymandering lawsuit considering Texas’s Hispanic population has driven the bulk of Texas’s population growth since 2010. According to census data, the current congressional map included 18 districts with white majorities and nine with Hispanic majorities. But the newly proposed map doesn’t give Hispanic voters any more clout: There are now 19 districts that have white majorities and still nine districts with Hispanic majorities, based on the voting age population.

This is only the first draft of Texas’s new congressional map, so it could still change before it’s passed by the GOP-controlled legislature. The Senate Redistricting Committee is expected to take up the congressional map on Thursday. But remember the GOP ultimately controls the redistricting process in Texas. That said, past congressional maps proposed by Texas lawmakers have been endlessly litigated — and it’s possible that could happen again this time around.

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

via Politics – FiveThirtyEight

Welcome to Pollapalooza, our weekly polling roundup.

In a break with Virginia’s recent electoral history, Republican Glenn Youngkin bested Democrat Terry McAuliffe in the state’s highly contentious governor’s race on Tuesday. Polls going into election night had the two neck-and-neck, but given McAuliffe had led the race until about a week before the election, it was still largely viewed as McAuliffe’s to lose — especially since Virginia Republicans had not won a statewide race since 2009 and Biden carried the state by 10 percentage points last year.

So who powered Youngkin’s win? Well, he overperformed across the state, but exit polling data shows he did especially well among certain voting blocs — like white voters (both men and women) and voters without a college degree — which gave his campaign a boost. But one of the biggest factors for Youngkin might have been his strong showing among suburban voters. According to exit poll data, Youngkin won 53 percent of these voters across the state, which is roughly the opposite of what happened in 2020, when exit polls suggest President Joe Biden carried voters in those areas with a similar share of the vote.1

In short, we identified three main throughlines that we think are useful at this stage when discussing Youngkin’s upset:

First and foremost, this is a story about suburban voters, who, on average, moved to the right. That is, as we suggested, a departure from what we observed nationally in the 2020 presidential election.

Education issues that dominated much of the lead-up to Tuesday’s race were significant for understanding how voters felt about the candidates, but it’s actually really hard to isolate the role education played in the race.

Rather, disappointment in — or opposition to — Biden’s presidency may have been the main driver of this outcome, as is often the case in off-year Virginia elections.

Let’s assess these one at a time: For starters, we (Geoffrey) wrote earlier this week that the big reason Youngkin was successful was his strength in the suburban areas of the state where former President Donald Trump previously struggled. That’s especially true in Loudoun County, one of the most populous suburban enclaves in the commonwealth.

!function(){"use strict";window.addEventListener("message",(function(e){if(void 0!==e.data["datawrapper-height"]){var t=document.querySelectorAll("iframe");for(var a in e.data["datawrapper-height"])for(var r=0;r

In Loudoun, McAuliffe underperformed relative to his party’s performance in 2020 while Youngkin overperformed: Although McAuliffe carried the county by 11 points, that marked a huge departure from Biden’s 25-point edge there last year. But Youngkin’s improved showing came across much of northern Virginia near Washington, D.C. (including Loudoun) as well as in predominantly suburban and exurban localities like Virginia Beach and Chesapeake in the southeastern corner of the state.

In unpacking why Youngkin made inroads in the suburbs, though, things get more challenging. From the beginning, Youngkin straddled being pro-Trump but not so Trumpy that he repelled suburban voters and white women (groups Trump famously struggled with). And because much of the previous suburban shift toward Democrats appears to have been driven by disdain for Trump, it’s now unclear that these gains will hold when Trump is off the ballot. It didn’t hurt that Youngkin, clad in a fleece vest most of the campaign, was able to posit himself as the spitting image of a genial suburban dad.

Interestingly, though, it doesn’t look like white college-educated voters, often disproportionately associated with the suburbs, necessarily drove Youngkin’s victory. The polarization of white voters by educational attainment has been a developing trend in recent years, and the Virginia result shows an even more substantial split, thanks mainly to Youngkin gaining among white voters without a college degree. Remember, plenty of white voters without a four-year degree live in suburban places, too.

The white voter education divide grew in Virginia

Vote share by race and education level, according to Virginia exit polls

Race Education Level Pct. of Electorate McAuliffe Youngkin Margin White College grads 37% 52% 47% D+5 Non-college grads 36 24 76 R+52 Nonwhite College grads 11 75 25 D+50 Non-college grads 15 79 20 D+59

Exit poll data received its final weighting on Nov. 3.

Source: ABC News

Meanwhile, McAuliffe still narrowly edged Youngkin among white voters with a college degree; in fact, his margin wasn’t much different from Biden’s in Virginia last November. By contrast, there wasn’t really much indication of an education gap among voters of color.

Second, while education-related issues — whether it was critical race theory or related to the pandemic — did seem to have had some effect on Tuesday’s results, it doesn’t seem like they alone influenced voters enough to push Youngkin over the edge. That doesn’t mean Youngkin didn’t make a concerted effort to appeal to parents, though. Throughout his campaign, he made subtle and not-so-subtle appeals to them by preying on fears around things like critical race theory being taught in the classroom. It wasn’t just the question of how race should be discussed in schools either. Youngkin also made appeals to parents fed up with more than a year of remote learning and other COVID-19-related school policies, like requiring masks in schools. But all of this falls under the category of “education,” which makes it incredibly hard to disentangle which issue had a bigger impact on voters. And as we’ll discuss below, it’s not clear that education was even the most important factor for voters.

While roughly 59 percent of men with children under the age of 18 living in their home, for instance, supported Youngkin over McAuliffe, a majority of women with children (53 percent) backed McAuliffe. Similarly, a majority of men without children (56 percent) backed Youngkin, while women without children (54 percent) backed McAuliffe. In other words, men voted similarly regardless of their parental status, as did women.

Parental status maybe wasn’t that important

Vote share by sex and whether the voter had any children under 18 years old living at home, according to Virginia exit polls

GROUP Pct. OF ELECTORATE McAuliffe Youngkin Margin Women Without children 37% 54% 45% D+9 With children 18 53 47 D+6 Men Without children 31 44 56 R+12 With children 14 41 59 R+18

Exit poll data received its final weighting on Nov. 3.

Source: ABC News

Of course, these numbers could be explained in part by the simple fact that men tend to vote Republican, while women, on average, tend to vote Democratic. But the gender gap among parents here is notable because it makes it more difficult to pinpoint what education issues were the most salient to voters. Also, it’s possible that “nonparents,” by the exit poll’s definition, included a lot of younger and older voters who might have canceled each other out.

But even if parental status wasn’t the most important thing in unpacking how voters voted on Tuesday, we shouldn’t discount the role education played in Tuesday’s race. Exit polling found that voters who believe parents should have “a lot” of say in what their child’s school teaches overwhelmingly supported Youngkin over McAuliffe (77 percent to 22 percent).

Other issues were also top of mind for voters, though. Polls ahead of Tuesday show that the economy topped voters’ list of concerns. According to exit polling data, Youngkin won those voters, who were one-third of the respondents, with 55 percent of the vote compared to McAuliffe’s 44 percent. Youngkin also edged McAuliffe among the 8 percent of voters who named abortion as the top issue in the commonwealth: 58 percent to 41 percent.

That said, it really does seem like disappointment with Biden’s presidency is what ultimately drove support for Youngkin. Not only does reporting already suggest that some people who supported Biden last year didn’t vote in Virginia’s election, but those who disapprove of Biden made up a majority of voters and voted overwhelmingly for Youngkin.

An unpopular Biden influenced how Virginians voted

Vote share by whether a voter approved or disapproved of President Biden’s job performance, according to Virginia exit polls

Strongly/somewhat ... Pct. of Electorate McAuliffe Youngkin Margin Disapprove 53% 10% 90% R+80 Approve 46 93 6 D+87

Exit poll data received its final weighting on Nov. 3.

Source: ABC News

For instance, 59 percent of voters who said they “somewhat” disapproved of the way Biden is handling his job as president and 96 percent who “strongly” disapproved backed Youngkin. Moreover, almost twice the share of people who had an unfavorable view of Trump backed Youngkin (17 percent) than the share who disapproved of Biden and backed McAuliffe (10 percent).

To be sure, as with any election, it’s really hard to disentangle whether macro trends (Biden’s approval) versus local factors (education and the economy) had the biggest impact on the shifts toward the GOP. But they are related, and if Democrats want to avoid a midterm shellacking next year, they might want to prioritize some of these more local issues that at least Virginians demonstrated could be important.

Other polling bites

Voters named “the economy and jobs” the No. 1 issue in Virginia’s elections this week, and nationally, the outlook on the economy isn’t too optimistic, with 65 percent of U.S. adults describing the economy as “poor,” according to an AP-NORC poll conducted Oct. 21-25. This is up 11 points from when AP-NORC last asked this question in September. But Americans are split on whether the economy will improve: 30 percent of adults said they expected the economy to improve next year while 47 percent said they thought it will get worse.

In Biden’s closing remarks on Tuesday at the United Nations Climate Change Conference, he pointed to Democrats’ spending bill as America’s contribution to the fight against climate change. Only one problem: Congress is still debating what will be in the bill. On climate specifically, a number of key provisions have already been cut, with some items, like a fee on methane emissions, still being ironed out. But per a Morning Consult poll taken last month, voters have started to doubt Biden’s ability to deliver on his campaign promise of sweeping climate legislation. Just 48 percent of registered voters said they approved of Biden’s handling of climate change, with 31 percent saying they somewhat approved and 17 percent saying they strongly approved.

Overall, though, Americans aren’t following Democrats’ spending bill or the bipartisan infrastructure bill too closely. An ABC News/Ipsos poll taken Oct. 29-30 found that a plurality of Americans, 44 percent, only knew “just some” of what might be in the bills. This is understandable given that what’s in the bill is still changing, but almost half of respondents, 45 percent, said they weren’t following negotiations carefully.

Americans increasingly don’t trust their own political institutions, and on the world stage, some countries also don’t think America is a great example of democracy. The Pew Research Center in February surveyed 16 countries, finding a median of 57 percent of respondents thought the U.S. used to be a good example of democracy but hasn’t been in recent years. However, one of the areas in which countries thought the U.S. excelled was technological advancements. A median of 72 percent of respondents across these 16 countries said the U.S. was the best or above average in technological achievements.

Many Americans, 56 percent, told the Public Religion Research Institute in its 2021 American Values Survey, conducted in September, that they thought believing in God was important to being truly American, but a separate poll from Pew conducted in March found that many Americans, 55 percent, think separation of church and state is important. Twenty-eight percent said they strongly supported the two institutions’ separation while 27 percent moderately supported their separation.

Biden approval

According to FiveThirtyEight’s presidential approval tracker,2 42.7 percent of Americans approve of the job Biden is doing as president, while 50.5 percent disapprove (a net approval rating of -7.8 points). At this time last week, 43.7 percent approved and 51 percent disapproved (a net approval rating of -7.3 points). One month ago, Biden had an approval rating of 44.8 percent and a disapproval rating of 47.8 percent (a net approval rating of -3.0 points).

Generic ballot

In our average of polls of the generic congressional ballot, Democrats currently lead Republicans by 2.3 percentage points (43.4 percent to 41.2 percent, respectively). A week ago, Democrats led Republicans by 2.5 points (43.9 percent to 41.4 percent). At this time last month, voters preferred Democrats over Republicans by 3.4 points (45.1 percent to 41.7 percent).

1 note

·

View note

Link

via Politics – FiveThirtyEight

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

sarah (Sarah Frostenson, politics editor): We’re back this week with the other 2022 primaries that are already on our radar — specifically, the big gubernatorial primaries and House primaries/macro trends to watch, as many House races are still in their nascent stage.

What follows is a preview of the candidates we know to be running (or at least seriously thinking about it) along with the intraparty fights Republicans and Democrats are having and what, if anything, this says about the general election.

OK, first up gubernatorial primaries. Which ones have already caught your eye?

nrakich (Nathaniel Rakich, elections analyst): One primary I’m watching is on the Democratic side in Florida. It looks like it will be a heavyweight contest between Rep. Charlie Crist, who was previously elected governor as a Republican, and state Agriculture Commissioner Nikki Fried, Florida’s only current Democratic statewide officeholder. And to add even more intrigue, state Sen. Annette Taddeo — who was Crist’s running mate the last time he ran for governor, in 2014 — has expressed interest in running, too.

Early polls give Crist a lead, which makes sense since he has lingering name recognition from his previous gubernatorial runs. But Fried could be more in line with the current zeitgeist of the party. Crist is an older white guy and, as a veteran of state politics, represents the party’s past. Fried, by contrast, is a younger woman who has already demonstrated a knack for online media (e.g., her multiple videos trolling Gov. Ron DeSantis).

Since Donald Trump was elected in 2016, it’s been good to be a woman in a Democratic primary, and I feel like it will also help Fried that she’s the one throwing red meat (blue meat?) to the Democratic base — if it remains a one-on-one race.

sarah: That’s a good point about Crist, Nathaniel. Alex had a piece earlier this year showing that Crist’s bid could face long odds, as he’s already lost two back-to-back races. Per her story, since 1998, only 33 candidates of 121 who’ve run for U.S. Senate, governor or president have managed to win after having lost their previous bid.

alex (Alex Samuels, politics reporter): Yeah, Sarah, in that piece we also cited a February Mason-Dixon poll of registered Florida voters, and just 27 percent said they viewed Crist favorably. Forty-one percent viewed him unfavorably.

Of course, things might have changed since then. But those numbers aren’t a great start …

sarah: How competitive, though, do we think the Florida governor’s race is going to be with DeSantis up for reelection?

geoffrey.skelley (Geoffrey Skelley, elections analyst): Florida has continued to move to the right in recent presidential elections, so it may not be the quintessential swing state it once was. While most of the swing states in the 2020 presidential election shifted to the left at least a little bit compared with 2016, Florida did the opposite. Trump actually won it by a larger margin than he did in 2016.

nrakich: Florida does have a knack for being close no matter which way the political winds are blowing, though. It was close in 2010, 2014 and 2018. So I think it will be competitive, but I wouldn’t bet against DeSantis.

alex: I wonder, though, if Democrats will use DeSantis’s very possible 2024 presidential run against him.

geoffrey.skelley: Democrats could certainly try to use DeSantis’s national ambitions in attack ads — “he doesn’t care about Florida; he cares about his political career” — but the effectiveness of such an attack might vary based on who the Democratic nominee is.

If it’s Crist, who has been governor, but then ran unsuccessfully for Senate in 2010 as an independent (after it became clear he would lose the GOP primary to Marco Rubio), and now wants to be governor again, such an attack might ring hollow because he’s seen as something of a political opportunist. Fried, on the other hand, is a fresh face and maybe could make that stick more. Nonetheless, I don’t think it’s the kind of thing that’s going to move the numbers much.

sarah: OK, Geoffrey, you’re up next.

geoffrey.skelley: Moving to another state that’s definitely no longer a swing state, I’m keeping a close eye on Ohio’s gubernatorial contest and its GOP primary. Republican Gov. Mike DeWine won in 2018 and now is looking for a second term, but he’s gotten quite a bit of intraparty backlash for his aggressive policies against COVID-19 — the Republican-controlled state legislature even voted to limit DeWine’s power to issue public health orders earlier this year. He also has attracted Trump’s wrath for not being a more vocal supporter. As such, former GOP Rep. Jim Renacci has decided to challenge DeWine in the GOP primary, and while it’s unusual for an incumbent governor to lose renomination, there’s at least some chance that could happen in Ohio.

It should be mentioned, however, that Renacci’s last campaign wasn’t especially impressive, as he lost the 2018 Senate race to Democratic Sen. Sherrod Brown by about 7 percentage points, having jumped over to that race after initially running in the gubernatorial contest that DeWine went on to win.

sarah: We were talking last week about how much the Ohio Senate primary, in particular, seemed to revolve around the question of who could be the Trumpiest candidate. Considering DeWine has received a fair amount of criticism from those in his own party, is he taking this primary bid seriously?

geoffrey.skelley: Well, Renacci is certainly trying to win over Trump supporters who are upset with DeWine. He tweeted last month that “Ohio First means America First!” and has gone after DeWine for his decision to close Ohio businesses and facilities to protect the public from the coronavirus.

alex: Brad Parscale, Trump’s onetime campaign manager, is also advising Renacci, according to NBC News.

sarah: But no Trump endorsement yet, right?

nrakich: Right, Sarah. That’s the big question for me in this race — will Trump endorse? Renacci was previously a close Trump ally and won his endorsement in 2018, but Trump reportedly soured on Renacci after his poor showing against Brown.

alex: NBC News also reported that a source told them the former president “has no plans to endorse him.”

geoffrey.skelley: Although Trump did openly encourage someone to run against DeWine.

sarah: I realize our primary challenge success-o-meter isn’t exactly apples-to-apples given this isn’t a presidential primary, but how would we weigh Renacci’s bid against DeWine currently?

geoffrey.skelley: Unfortunately, we haven’t seen a good independent poll of Ohio in a while. But back in the fall in 2020, DeWine polled quite well — for instance, an Ipsos/Spectrum News survey found last October that about two-thirds of Ohioans approved of his job performance, including 73 percent of Republicans. That was perhaps a little low for a Republican but still not the sort of terrible position that would indicate serious vulnerability in a primary. However, DeWine didn’t support Trump’s post-election attempts to overturn the election, so perhaps opposition has grown. Renacci’s internal polling — which should be treated with serious caution — did find him ahead of DeWine in the spring.

sarah: I’ll go next with the Pennsylvania gubernatorial primary.

Last week we talked about the Pennsylvania Senate primary, but there’s more than one marquee race in the state this year. Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf is term-limited, meaning the governor’s mansion is also up for grabs. Who’s actually running in this race is still very TBD, though.

For instance, no Democrat has officially declared they’re running at this point. But that may be because everyone is waiting to see what state Attorney General Josh Shapiro does. Earlier this year, he told Philadelphia Magazine that “I expect to be a candidate.” And if Shapiro does run, he’s likely a front-runner on the Democratic side given the profile he has built as the state’s attorney general. In 2017, he tackled the Catholic Church’s decades of sexual abuse in Pennsylvania dioceses. He also joined other attorneys general in fighting Trump’s travel ban and an injunction that stopped Trump’s rollback of birth control. Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney is reportedly considering a run, too, but he’d have to resign as mayor if he did run.

Among Republicans, though, far more names have been floated at this point, and even a few have entered the fray, including former U.S. Rep. Lou Barletta. Barletta ran unsuccessfully for the Senate in 2018, but he’s built a reputation as a bit of a conservative folk hero for trying to take on illegal immigration while he was mayor of Hazleton, Pennsylvania. The law was ultimately struck down, but Barletta tried to penalize businesses and landlords who hired or rented to immigrants who had illegally entered the country. So far this Trumpy profile hasn’t helped Barletta win statewide office in Pennsylvania, though, and it looks as if he might face stiff competition from other Trumpy Republicans in 2022.

For instance, state Sen. Doug Mastriano hasn’t said he’s running yet — although he claimed Trump had asked him to run and promised to help him campaign (an aide told the AP that wasn’t true) — but he’s already showing his Trump bona fides, having hosted a hearing devoted to unfounded claims of 2020 election fraud and marching to the U.S. Capitol before the Jan. 6 insurrection. He’s also pushing an Arizona-style “audit” of the 2020 election in Pennsylvania.

But Mastriano isn’t the only possible contender with connections to Trump. Rep. Mike Kelly is also reportedly considering a bid and has a relationship with Trump. Notably, too, Trump-appointed former U.S. Attorney Bill McSwain has already written to Trump seeking his endorsement even though he hasn’t yet said whether he’ll run. If McSwain does enter the race, though, it means potentially two prosecutors could go head-to-head in the general election.

A number of other Republicans are considering runs at this point, too, including U.S. Rep. Dan Meuser and state Sen. Dan Laughlin. Not to mention a number of candidates who have already thrown their hats in the ring with Barletta, including Montgomery County Commissioner Joe Gale and conservative activist Charlie Gerow.

The Republican gubernatorial primary in Pennsylvania is looking really harried at this point, and similar to many of the other primaries we’ve discussed, it seems as if it is going to be a competition around who can out-Trump the other.

geoffrey.skelley: Republicans are definitely hoping Pennsylvania will continue its pattern of flipping back and forth between the parties. It’s been more than 50 years since either party elected a successor to a sitting member from their party, and it’s never happened since the state got rid of its single-term limit in 1968.

alex: How likely is it that the Senate seat flips without the governor’s seat flipping, too?

nrakich: Good question, Alex. States don’t always vote the same way for Senate and governor, since one office is federal and the other is state-level, but the two offices have been tracking more closely in recent years. As Geoffrey wrote a few years ago, there was less split-ticket voting in 2018 than in any midterm since at least 1990.

geoffrey.skelley: And Pennsylvania voted very similarly for Senate and governor in 2018, when both races had incumbents, and I suspect they’ll vote similarly this time, too. After all, neither race will have an incumbent this time, so that will mean no candidate will get the ever-smaller incumbent bonus.

sarah: OK, Alex, you’re up!

alex: Well, Georgia is becoming a competitive battleground state, as evidenced by President Biden’s win there in November and Sens. Jon Ossoff’s and Raphael Warnock’s respective victories earlier this year. So the gubernatorial primary is going to be fun to watch.

On the Republican side, you have incumbent Gov. Brian Kemp fighting for a second term in what maybe should have been an easy feat for him. But after he didn’t embrace Trump’s unfounded claims about widespread election fraud in last year’s election, Kemp lost the support of some Republicans — particularly those on his right flank. So he has a couple of primary challengers now, including Vernon Jones, a former Democratic state lawmaker turned Republican and one of Trump’s most vocal allies in Georgia, and also Kandiss Taylor, a public school teacher and counselor.

What’s working in Kemp’s favor, other than his incumbency, is the fact that he did sign a far-ranging election measure in March that includes new restrictions on voting by mail and greater legislative control over how elections are run. That hasn’t placated Trump, though, who called the law “weak” and said Republicans in the state should have taken far more drastic steps to curtail the ability to vote; Republican voters, however, have rallied around the state’s new voting law, and according to a Morning Consult tracking poll, Kemp had a 62 percent approval rating among Georgia Republican voters when he signed the elections bill on March 25. By April 6, it was up to 74 percent.

Meanwhile, on the Democratic side, I think everyone is just waiting patiently to see whether Stacey Abrams runs again. A lot of folks see the former speaker of the Georgia House running again in 2022 as a likely next step. A January poll from The Atlanta-Journal Constitution found that about 51 percent of Georgians viewed her in a positive light, including 10 percent of Republicans (although 41 percent of Georgians viewed her unfavorably).

geoffrey.skelley: Unlike in most states, a worry for Kemp is that he has to win a majority of primary voters because Georgia is one of seven states with a majority requirement for primary elections. So a crowded race doesn’t help him by splitting opposition — it would just get him a runoff where he’d have to win a majority.

sarah: The call for primary challengers in both Georgia’s and Ohio’s gubernatorial races from Trump … and then radio silence on who he’d back is certainly a strategy, though. It doesn’t seem as if either race, at this point at least, is posing a credible threat to the GOP incumbent.

nrakich: Yeah, Kemp is vulnerable in theory, but I just don’t see any credible candidate standing up to challenge him. It could get interesting if Trump endorses someone like Jones, but ultimately I don’t think he has what it takes. It will be incredibly easy for Kemp to smear him as a former Democrat, and Jones has a pretty sordid past — while serving as DeKalb County CEO, he was accused of rape, and a grand jury recommended that he be criminally investigated for corruption.

sarah: As we were talking about in Pennsylvania, though, the fact that Georgia has two elections up here in 2022 will be interesting, as the incumbents aren’t from the same political party.

So considering split-ticket voting is on the decline, it’ll be interesting to see whether Warnock and Abrams, assuming she runs again, win. Or whether it’s Kemp and as we discussed last week, Herschel Walker. Walker, though, as we said, still hasn’t entered the race, and given that he is a longtime Texas resident, he could face serious issues mounting a successful bid against Warnock.

It’s early yet, but these two races seem to be a little mismatched in terms of competition, as Abrams would be a heavyweight were she to enter, and Walker just isn’t that.

geoffrey.skelley: That potential scenario — if Walker is the GOP Senate nominee — could be interesting because the little swing vote that exists could be critical in places like affluent northern Fulton County and suburban Cobb and Gwinnett counties, where at least a few Kemp 2018-Warnock 2020 voters live. Will those voters line up behind one party or stick with Warnock and then go for Kemp again?

nrakich: One effect that the primary could have, even if Kemp wins it, is to push him further to the right — which could turn off voters like that. That’s basically what happened to former Sen. Kelly Loeffler, Warnock’s 2020 opponent.

geoffrey.skelley: Exactly. The handful of voters who went for Warnock but in some cases stuck with former Sen. David Perdue — who lost to Ossoff in the other Senate race — are the voters I’m thinking about here.

sarah: OK, now this is a harder office to track at this point given the number of races, but what do we know about House primaries at this point? Or macro trends about the House that you’re already plugged into?

alex: There was an interesting PBS piece on how a gerrymandered Texas, specifically, could help Republicans with their goal of taking back the House in 2022. Here are some of the takeaways: Since the state gained two seats in the reapportionment process and the GOP-controlled legislature is in charge of making the new maps, these seats will likely be prime pickup opportunities for Republicans. What’s working against Republicans here is that Texas suburbs are becoming more blue, and they’ve already been accused of gerrymandering. But I think it’s fair to assume lawmakers will try to redraw these districts to benefit their party. And considering Republicans need only five seats to flip the House in 2022, Texas’s two new seats are a good opportunity for that.

geoffrey.skelley: Yeah, the big thing is redistricting. That’s going to influence where candidates run and who retires, and as Alex notes, who might win. If you’re the GOP drawing lines in big states like Texas or Florida, maybe you try to add Republican voters to a handful of Democratic-held seats.

That said, you still have a lot of candidates already declaring bids even though they don’t necessarily know exactly where the seat is going to be, simply because candidates need to start raising money and may have some inkling as to what the district in their area will look like.

sarah: And as Geoffrey and Alex are getting at, Republicans will disproportionately control the redistricting process. As Geoffrey and Nathaniel reported earlier this year, Republicans will redraw nearly 2.5 times as many districts as Democrats, 187 congressional districts versus 75. (To be sure, there are also 173 districts where neither party will enjoy exclusive control over redistricting — either because of independent commissions or split partisan control or because it’s an at-large district.)

nrakich: Thanks to redistricting, a big theme in House primaries next year is also going to be incumbent-versus-incumbent battles. Take a state like West Virginia, which is going from three congressional seats to two. Two of its current representatives are inevitably going to be drawn into the same district. Unless one retires, that will be a pretty spirited race.

And other incumbents could be thrown into races against each other in states where the opposite party controls redistricting — for example, Illinois Democrats may draw two of the state’s downstate Republicans together.

geoffrey.skelley: Aside from redistricting, I’d say the other main place where primary challenges are developing is with the 10 Republican House members who voted to impeach Trump in January. I dug into their races earlier this year, and all but one of them already has at least one primary challenger. The lone one without a challenger is New York Rep. John Katko, but Trump recently told local Republicans he’d be happy to boost a challenger if they can find one. Then again, it’s also possible that Katko’s district will change substantially in redistricting because Democrats are in a position to control the process there.

I wouldn’t be surprised to see at least a handful of them retire or, because of redistricting, find themselves without a similar district to run in. Along with Katko, Illinois Rep. Adam Kinzinger’s seat could be ripped up by state Democrats, who control things. And in Ohio, Republican Rep. Anthony Gonzalez’s impeachment vote probably won’t make him a priority for the state GOP to protect as they draw maps there.

sarah: It is a midterm election, though, and traditionally the party in the White House has fared poorly as a result. We’ve talked about why that might not be the case here in 2022, but one question I have is about the overall map. Do Democrats just have more vulnerabilities — that is, more Republican-leaning seats to defend — than Republicans?

geoffrey.skelley: Well, it’s interesting. Democrats actually are much less exposed headed into 2022 than in 2010, the last midterm for a first-term Democratic president. Using FiveThirtyEight’s partisan lean metric, 74 Democrats represented seats that were more Republican than the country as a whole heading into the 2010 election. By comparison, only 24 Democrats are in the same position right now. So almost 3 in 10 Democrats in 2010 versus 1 in 10 Democrats today.

However, those pre-2022 numbers won’t be the final story because redistricting will change the state of play quite a bit in some states. And because Republicans control redistricting in more places, I suspect those numbers are more likely to worsen than improve for Democrats.

And given the Democrats’ narrow 222-213 seat edge, small changes could be enough to give the GOP a majority, too.

sarah: Interesting. There’s simply less easy ground for Republicans to make up, at least at this point, especially given some of their gains in 2020. But as you’ve all pointed out, what happens in the redistricting process could make a big difference moving into 2022.

0 notes

Link

via Politics – FiveThirtyEight

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

sarah (Sarah Frostenson, politics editor): On Monday, the Supreme Court agreed to hear a case that directly challenges the constitutional right to abortion as established by Roe v. Wade in 1973.

The case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, involves a Mississippi law that seeks to ban most abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy, which is about two months earlier than Roe and subsequent rulings, such as Planned Parenthood v. Casey, allow. Notably, Casey, the 1992 decision that has largely superseded Roe, does give states the right to regulate abortion, but only after the point of fetal viability — or the point at which a fetus can survive outside the womb, roughly 23 or 24 weeks.

The Supreme Court has decided a number of issues relating to procedures and regulations surrounding abortion — as recently as the last term, in fact — but this case is notable in that it is the first case, in a long time, that will be faced with the question of when abortion itself is constitutionally protected.

The stakes, simply put, are high, and in the spotlight, once again, is the question of how aggressively the court’s new six-justice conservative majority will act to dismantle abortion rights.

Let’s start with the stakes of this latest challenge, then discuss where Americans stand on abortion, and finally, wrap with the politics of this, as the court’s decision will likely come next summer in the lead up to the 2022 midterm elections.

To start, the stakes.

meredithconroy (Meredith Conroy, political science professor at California State University, San Bernardino, and FiveThirtyEight contributor): As FiveThirtyEight’s Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux has written, states have passed hundreds of restrictions in the last decade that have made it harder to get an abortion, leaving a patchwork of abortion access that has disproportionately affected rural women, poor women and women of color.

Women’s access to abortion already depends a lot on where they live. But the stakes in this case are that if the court upholds the law, the most vulnerable women, who can’t travel long distances for an abortion or afford one, will be the ones most affected.

alex (Alex Samuels, politics reporter): The stakes are huge here. The Supreme Court is essentially debating if all state laws that ban pre-viability abortions are unconstitutional.

sarah: A lot of analyses are emphasizing the makeup of the court and the role it plays now that there is a six-justice conservative majority — and I certainly don’t mean to downplay the stakes, the constitutionality of abortion is on the table — but one thing to keep in mind is the fact that the court has a conservative majority means they’ll take up more cases that could move the law fundamentally to the right.

Amelia wrote about this last year during the nomination process for Justice Amy Coney Barrett, but Supreme Court legal experts stressed to us then that the types of cases the court will hear will dramatically change. In other words, even if it’s still an open question as to how the court will approach this case, the fact that they’re choosing to tackle it now shouldn’t be that much of a surprise. Conservative legal advocates want to test how far this court is willing to go.

meredithconroy: It’s interesting, too, that the court might leave abortion access up to the states at a time when states are electing more women. One might think that more elected women bodes well for those in support of abortion-rights, but political science research has found that electing more women puts this issue on the agenda more often, and for Republican women that means more anti-abortion bills, as the gender gap on abortion is a bit of a myth.

alex: And considering, Meredith, that a majority of state legislatures are Republican-controlled, that doesn’t that bode well for abortion access, right?

meredithconroy: Ya, exactly. Republican-controlled legislatures + more elected Republican women is a formula for more anti-abortion legislation.

alex: And as you were getting at, Meredith, on the lack of a gender gap on abortion, the Pew Research Center found recently a pretty modest gender divide: 56 percent of men and 62 percent of women say abortion should be legal in at least most cases.

The bigger gap was a partisan one: 80 percent of Democratic women and 79 percent of Democratic men say abortion should be legal in all or most cases; on the flip side, just 32 percent of Republican men and 39 percent of Republican women feel the same way.

meredithconroy: But there is a gap in how important men and women find the issue of abortion — women care a lot more about it than men.

sarah: A third of Republicans saying abortion should be legal in all or most cases seems sizable, though. I realize there’s a clear partisan gap here, but that pushes back against this being a super clear-cut issue, right, Alex?

alex: Oh for sure, Sarah. One thing that struck me about this piece from my former FiveThirtyEight colleague Perry Bacon Jr. is that abortion isn’t as black and white of an issue as politics might make it seem.

For example, Gallup found that Americans are united in opposing abortion during the second and third-trimesters of pregnancy, the latter of which is extremely rare. According to their polling on the topic — which was last conducted in May 2018 — only 13 percent of respondents said abortion should be legal in the last three months of pregnancy (this compares to 28 percent who said it should be legal in the second trimester and 60 percent who should be legal in the first trimester.)

The Mississippi law, though, falls into a weird, gray zone in that it seeks to impose restrictions at 15 weeks, which does fall in the second trimester, but still challenges what Roe established as fetal viability, or the point at which a fetus can survive outside the womb. Nonetheless, the polling suggests some Americans might be OK with states having the ability to impose restrictions starting at 15 weeks.

geoffrey.skelley (Geoffrey Skelley, elections analyst): Yeah, for a long time now, a sizable majority of Americans have said they favor some access to abortion. For instance, in 2020, Gallup found that 79 percent of Americans wanted abortion to be legal in at least some circumstances.

Now, only 29 percent said they wanted abortion to be legal in any situation, but another 50 percent favored it in some cases. And on the question of whether to overturn Roe v. Wade decision, the majority of Americans want to keep it. Recent polls have found around 60 percent either agree with Roe or oppose overturning it.

meredithconroy: Like Sarah mentioned, it’s interesting that this court decided to hear this case, now. You need only four justices to agree to hear a case and it seems likely that at least three of the justices will side with Mississippi (Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch), and probably Barrett, as well.

That means Justice Brett Kavanaugh could be the likely deciding vote, and that’s significant given how much his assumed position on Roe influenced support for his nomination. Consider the number of times Sen. Susan Collins went to bat for Kavanaugh when she defended her choice to vote for him because he would not be open to undoing Roe, as a “settled law.”

sarah: Right, Meredith, given how Roberts ruled on the abortion case last year — he joined the liberal justices — it’s probably a stretch to think he will side with the conservative justices this time (even though, Roberts made it clear in that case that he thinks the underlying decision was wrong). It’s just that, I think, as chief justice, Roberts cares more about consistency in the court’s rulings and its image.

Barrett, as you get at, though, has a pretty clear perspective on abortion and while she dodged answering how she’d rule on abortion in her confirmation hearings, she did admit that she doesn’t view Roe as a “super-precedent” — or a ruling so enshrined in American law that it can’t be overturned.

Let’s talk a little about the politics of this, though.

The justices will most likely hear this case next term, with a decision next summer, as it’s bound to be a contentious, high-profile case, and the court’s most controversial decisions often come at the end of the term in June.

What do we know about the Supreme Court as a motivating factor for voters? The court has long been thought of as something that drives Republican voters, but not necessarily Democratic voters. Is that changing?

alex: Well, at least on the question of the court and abortion it does seem as if it might motivate be starting to motivate Democrats more. Take what FiveThirtyEight contributor Dan Cox found in his 2018 piece on this topic. Amid Kavanaugh’s contentious confirmation hearing, a 2018 Pew poll found that 61 percent of Democrats said abortion was very important to their vote that year, whereas 10 years earlier, only 38 percent of Democratic voters felt the same.

That said, neither Democrats nor Republicans were that concerned about abortion heading into the 2020 election: Fewer than half of registered voters (40 percent) said abortion would be a very important factor in their political decisions last year, per Pew.

geoffrey.skelley: Yeah, the conventional wisdom has long been that Republicans are more animated by abortion and the Supreme Court than Democrats. For example, Justice Antonin Scalia’s death during the 2016 presidential campaign and then-candidate Donald Trump’s pledge to nominate a conservative justice helped to make the court a bigger issue in the campaign, which in turn, helped Trump lock down Republican-leaning evangelical Christian voters and win the extremely close 2016 presidential election. Of course, in an election that close, you could say anything mattered, but the court was certainly a factor.

sarah: That’s right, Geoffrey, and it’s something Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, then majority leader, banked on as a strategy to energize Republicans. He refused to consider then-President Barack Obama’s Supreme Court nominee, leaving a vacancy on the court for Trump to fill. (Only to then contradict his own logic in 2020).

It’s possible, then, that this case could be a huge animating factor for Democrats — or Republicans — headed into the 2022 midterms.

Let’s talk a little bit more about the 2018 midterms, though, since the court played such a big role with voters then. What do we know about the role of the court in that midterm election?

meredithconroy: As FiveThirtyEight editor-in-chief Nate Silver wrote in the lead up to the election, Kavanaugh’s nomination may have actually helped Republicans more than Democrats, especially in the Senate, where they gained in FiveThirtyEight’s forecast.

The confirmation hearings really hurt Kavanaugh’s perception overall, though. There was a pretty big split by party as the chart below shows, but support for Kavanaugh remained strong among Republicans.

geoffrey.skelley: As Meredith is getting at, I’m not sure how much the battle over Kavanaugh’s nomination mattered in the House in 2018, where Democrats won handily, but it is possible that it contributed to the defeat of Democratic senators in red states, like Heidi Heitkamp of North Dakota, Joe Donnelly of Indiana and Claire McCaskill of Missouri.

They each needed to win over at least some Republican-leaning voters to stand a chance at reelection, but all three voted against Kavanaugh. Notably, Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin voted for Kavanaugh, which might have saved his bacon in his close reelection race in deep-red West Virginia.

But turning our eyes to 2022, if the court’s decision is interpreted as overturning Roe, that could prove politically beneficial to Democrats in the 2022 midterms.

Liberal activists will be motivated by it, but it also might keep pushing college-educated voters into the Democratic camp, or at least keep them there after they moved toward the Democrats during Trump’s time in office.

Consider that Pew’s most recent polling numbers found that 59 percent of Americans think abortion should be legal in all or most cases. But among college graduates, that figure jumps to 68 percent. And as voters who are more educated tend to be more likely to vote even in lower-turnout midterm elections, this could help Democrats limit some of the midterm penalty the president’s party tends to suffer.

meredithconroy: That’s right, Geoffrey. A big story in the last two presidential election cycles has been the role education plays in vote choice, so if abortion is a big issue moving into 2022 because the court has seriously dismantled Roe, I imagine that divide will grow, or at least remain the same. Consider how the GOP has already started to shed white, college-educated, suburban women; seriously altering Roe could hurt their standing even more with this group.

sarah: That’s an interesting point, but, of course, it’s so hard to game out how this will (or won’t) affect an election still more than a year away. And how the justices will rule is still an unknown.

One trend, at this point, though is clear. Trust in the court is waning. A 2020 Gallup poll conducted before Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death found that only 40 percent of Americans said they had “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the Supreme Court.

Trust in the court is low, in part, because just like Congress and our other institutions, it is increasingly seen as partisan with Democrats having a less favorable view of it now.

geoffrey.skelley: Trying to claim that the judiciary is above partisan politics just ignores the appointment process and the often partisan views of judges themselves. There’s an interesting tension here, too, for Democrats in that some activists in the party are pressuring Justice Stephen Breyer to retire so that President Biden can appoint a younger liberal justice in his place, but Breyer seems intent to stay on at least a while longer. He’s said that politics doesn’t — or shouldn’t, at least — play a part in judges’ work.

meredithconroy: Ha, jinx, Geoffrey. The idea that justices are insulated from public opinion and apolitical or objective has always been a bit of a joke. They may sometimes rule in line with public opinion, as they did in 2020 (and political science research does find justices to consider public opinion, especially when issues are less salient), but they also sometimes rule according to their own idea of the law.

0 notes