#Adolf Reinach

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unter Друг (d.i. auch unter Freunden), Drugs, Druck, Drügh, Drücker

The Clockwork Orange tickt mal wieder nicht richtig, muss mal wieder aufgezogen werden, wie immer. Die Erde rückt, die Zeitung druckt, jeden Tag was anderes.Der freundliche Mitstreiter, d.i. Kollege Heinz Drügh schafft es 'ne so freundschaftliche Tagung zur Autonomie zu veranstalten, aber neben dem Bericht findet man einen Druck von El Lissitzy. Derweil sitzen wir über den Akten, unter den Freunden Reinachs.

You may negate autonomy, you may confirm autonomy, you shall negotiate autonomy. Negation, d.h. ist bei Reinach ein Akt, der Verneinung und Verhandlung umfasst. Der Akt ist Technik, der die Möglichkeiten des Neins und die Möglichkeiten des Jas reproduziert. Diese Negation umfasst Affirmation. Man kann das Wort englisch oder deutsch ausprechen, egal ist nicht, wie man es ausspricht, aber beides geht, man muss nur übersetzen. Negation nennt Cornelia Vismann eine Akte oder einen Händel.

Darum stellen mir Autos keine Fragen. Kreuzungen stellen mir Fragen. In Frankfurt ist gerade viel los, toll! Alle machen gerade tolle Sachen, muss am Wetter liegen.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Lo que Dios obra en su interior durante las horas de meditación no se percibe a simple vista. Pero se supone una gracia tan grande, que todas las demás horas de la vida están agradecidas e influidas por este tiempo de meditación”

Edith Stein

Fue una filósofa, mística religiosa, mártir y santa alemana de origen judío nacida en Breslavia imperio alemán hoy Polonia en octubre de 1891.

Nació en el seno de una familia judía, su padre era dueño de un aserradero y fue la séptima hija de un total de 11 hijos del matrimonio, y como tal vivió las raíces hebreas familiares y el nacionalismo prusiano.

Desde muy temprana edad mostró especial interés por la historia y la literatura alemanas y de las grandes figuras de la música como Bach, Mozart y Wagner.

A la edad de 15 años experimentó una etapa de ateísmo y crisis existencial, causada por el suicidio de dos de sus tíos y la falta de respuesta de la religión al tema del más allá. Abandona el colegio y se traslada a Hamburgo para asistir a su hermana Elsa quien iba a tener un hijo.

En 1913, la lectura de “las investigaciones lógicas“ de Husserl le abrió una nueva perspectiva en vista a su orientación objetivista, por lo que decide trasladarse a Gotinga a terminar los cursos universitarios y por ejercer Husserl allí su magisterio.

En Friburgo, en 1917, aprobó con la calificación de summa cum laude su tesis doctoral titulada “Sobre el problema de la empatía”, tema que le sugirió Max Scheler, con el que inició sus obras filosóficas.

Como estudiante de filosofía, fue la primera mujer que presentó una tesis en esta disciplina en Alemania.

Gracias a su amigo Georg Moskiewicz, Edith Stein fue aceptada en la sociedad de la filosofía de Gotinga, que reunía a los principales miembros de la fenomenología naciente como Edmund Husserl, Adolf Reinach y Max Scheler, y durante estos encuentros una correspondencia personal y profunda con el filósofo, ontólogo y teórico literario Roman Ingarden así como con el filósofo francés de origen ruso Alexandre Koyré.

Durante la primera guerra mundial Edith Stein decidió regresar a Breslau, tomó cursos de enfermería y trabajó en un hospital austriaco. Cuando el hospital fue cerrado, Edith regresó a reanudar sus estudios filosóficos con Husserl obteniendo un doctorado en la Universidad de Friburgo.

Una vez obtenido el doctorado, se enroló en la cruz roja en donde fue enviada a ocuparse de los enfermos de problemas infecciosos y trabajo en salas de operaciones, obtuvo una medalla por su dedicación y debido a lo precaria de su condición de salud fue enviada a su casa y no la llamaron mas.

Estas experiencias con los jovenes que morían a muy temprana edad de todas partes de Europa del Este, la marcaron profundamente, y poco a poco fue acercándose a la fé católica, la entereza con la que su amiga Ana Reinach, sobrellevó la muerte de su joven esposo, una vez que ambos fueron bautizados así como su acercamiento a los escritos de Santa Teresa de Jesús, y la entrada en una iglesia católica de Frankfurt en donde reparó la presencia del santísimo, hizo que se decidiera a ser bautizada en enero de 1922.

Durante esta época, dedica parte de su vida a la docencia con poco éxito para ofrecer cátedra en universidades, por lo que se dedica a dar clases particulares de fenomenología y ética en Breslau y en ocasiones pronuncia conferencias en congresos de pedagogía en Alemania, Austria y Suiza.

En octubre de 1933 ingresa al Carmelo de Colonia y rehusa marcharse a Iberoamérica para huir del nacional socialismo prefiriendo permanecer junto a los suyos, hasta que el 31 de diciembre de 1938, tras “la noche de los cristales” es trasladada al Carmelo holandés de Echt que para entonces era un país neutral, sin embargo esto no impide su deportación en 1940 junto con 244 judíos católicos mas tarde, y ser llevada a las cámaras de gas de Auschwitz-Birkenau en donde muere en compañía de su hermana Rosa.

Durante su estadía en Auschwitz cuida de los niños encerrados en ese campo, los acompaña con compasión hacia la muerte y les enseña el Evangelio a los detenidos.

Fueron conmovedores relatos de sus últimos días dando ánimo a las demás profesas, haciendo que el papa Juan Pablo II la canonizara como Santa Teresa Benedicta de la Cruz en octubre de 1988.

Su sólida visión de personalista cristiana forjada entre la fenomenología, el tomismo y la mística, es fruto de una pasión que supo encauzar con audacia en medio de una vida singular, fruto de un arduo camino intelectual y vital que el hombre de la primera mitad del siglo XX se exponía con el materialismo, el nihilismo, el hedonismo, la xenofobia y el nazismo de su época.

Fuente: Wikipedia y philosophica.info, personalismo.org, vaticannews.va

#frases de filosofos#citas de filosofos#filosofos#notasfilosoficas#citas de la vida#frases de reflexion#citas de reflexion

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

SANTA TERESA BENEDETTA DELLA CROCE

(EDITH STEIN)

1891 - 1942

Martire

Patrona d'Europa

Patrona delle Giornate Mondiali della Gioventù

Festa, 9 agosto

Edith, affamata di verità ma non credente

A Breslavia, allora città tedesca, Edith Stein nacque il 12 ottobre 1891 (quell'anno ricorreva la festa ebraica del "Kippur", cioè della Riconciliazione-Espiazione) da Sigfrido e da Augusta Courant, ultima di undici figli di cui quattro morti in tenera età. La famiglia, d'origine e di osservanza ebraica, per la precoce morte del capo famiglia fu presto tutta a carico della signora Augusta, che, da vera donna forte, seppe condurla per la via dell'onestà e dell'agiatezza.

Edith, cosciente del proprio ingegno precoce, della memoria eccezionale e della brama di sapere che prestava nell'ascolto e la lettura, diede da piccola qualche segno d'orgoglio, di vanità, di ostinazione: ordinarie nubi, tempestivamente dissipate. Nel sano ambiente familiare trascorse l'infanzia e l'adolescenza abbastanza serenamente, con un progressivo affinamento del carattere. Alle scuole elementari e medie si classificò sempre fra le migliori alunne; perciò, con il consenso della mamma, decise di andare avanti negli studi.

Superato in modo brillante l'esame di licenza liceale, si iscrisse all'Università. Frequentò corsi di storia, di filologia e di psicologia sperimentale; ma, attratta dalla speculazione filosofica, dopo due anni di intensa applicazione a Breslavia, volle andare a Gottinga, dove fioriva l'indirizzo filosofico di Edmund Husserl. Intendeva trascorrervi solo un semestre, tuttavia l'ambiente particolarmente propizio agli studi prediletti, la presenza di professori illustri, quali Adolf Reinach, Max Scheler, Max Lehmann, Leonard Nelson, Eduard Schröder, Giorgio Ellia Müller, e soprattutto, la benevola accoglienza dello stesso Husserl, la indussero a proseguire i corsi a Gottinga.

Allo scoppio della guerra 1914 - 1918 la Stein si offrì volontaria e si prodigò quale infermiera della Croce Rossa in un ospedale militare della Moravia.

Nel 1916 Husserl lasciò Gottinga per passare alla cattedra di filosofia a Friburgo in Brisgovia: Edith Stein lo seguì e si laureò con lui "summa cum laude" facendo una tesi sull'Einfühlung (empatia), ed egli la scelse per sua assistente. La giovane professoressa si applicò nel raccogliere e riordinare gli scritti del "maestro", tenne corsi di propedeutica allo studio della fenomenologia, diede avvio all'opera "Contributi per una base filosofica della filosofia e delle scienze dello spirito". Tutta tesa nell'impegno scientifico, rinunciò anche alle vacanze estive in famiglia, nel 1917 e nel 1918. Studentessa e insieme docente universitaria, Edith era di condotta ineccepibile. Semplice, serena, pronta al sacrificio per compiacere professori e studenti, era assetata di verità, di oggettività. Era affettuosa verso i suoi cari, specie verso la madre, sebbene non ne condividesse la fede religiosa. Era infatti divenuta agnostica circa il problema religioso, che riteneva insolubile.

Conversione a Dio e impegno di testimonianza nel mondo

Dio si fa incontro per mille vie a chi cerca la verità con cuore puro e sincero. La Stein, superando poco alla volta la sua preconcetta negazione di Dio, aprì gli occhi alla luce che promanava da chi viveva con coraggio la fede, come Max Scheler, o da chi accettava con una rassegnazione umanamente inspiegabile la perdita del marito in guerra, come accadde alla sua amica Anna Remach. Alludendo a questo, la Stein avrebbe scritto più tardi: "Fu quello il momento in cui la mia incredulità crollò, impallidì l'ebraismo e Cristo si levò raggiante davanti al mio sguardo: Cristo nel mistero della sua Croce!".

L'ultima incertezza svanì nell'estate 1921 alla lettura, del tutto occasionale e protratta di seguito per un'intera notte, dell'autobiografia di Santa Teresa d'Avila. Al mattino, si procurò subito un catechismo e un messalino. Di lì a non molto venne ammessa al Santa Battesimo, che le fu amministrato nella chiesa di Bergzabern il Capodanno 1922, con l'imposizione anche del nome di Edvige. La gioia di quel giorno fu coronata dal primo incontro con Gesù Eucarestia. Circa un anno dopo, il 2 febbraio 1923, a Spira ricevette il sacramento della Cresima.

Ormai per Edith Stein la filosofia, da fine supremo era diventata un mezzo per meglio conoscere e amare la Verità vivente, Cristo Redentore e la sua Chiesa. La sua conversione fu radicale, convinta: nulla potè farla retrocedere, né le vaste conoscenze del mondo universitario, né lo smarrimento dei suoi parenti, in particolare della sua amata mamma, che difendeva la tradizione ebraica della famiglia. Per essere tutta di Dio Edith avrebbe anzi voluto lasciare il mondo e ritirarsi fra le mura di un chiostro carmelitano teresiano. La trattenne l'umile sottomissione al confessore, il canonico J. Schwind, che le consigliò di lasciare Friburgo per un luogo più tranquillo e meglio adatto al suo orientamento spirituale.

Si trasferì così a Spira, dove insegnò lingua e letteratura tedesca presso l'Istituto Magistrale delle Domenicane. Vi trascorse otto anni, appartata, tutta dedita alla preghiera, alla scuola, allo studio di San Tommaso d'Aquino. Divenne apostola di verità. Seppe infatti rompere le maglie di una filosofia chiusa, nelle quali si era impigliato lo stesso Husserl, per approdare "all'ontologismo trascendentale", alla verità di tutto che viene dal Tutto Dio.

In occasione del 60° compleanno di Husserl (1929), gli dedicò uno studio: "La fenomenologia di Husserl e la filosofia di San Tommaso d'Aquino". Tenne frequenti conferenze su argomenti di pedagogia, filosofia e religione a Heidelberg, Friburgo, Monaco, Colonia, Zurigo, Vienna, Praga, Salisburgo, ecc.

Dopo la morte del suo primo direttore spirituale, mons. Schwind (17 settembre 1927), di cui scrisse un ricordo per la rivista del clero edita a Innsbruck, conobbe l'abbazia di Beuron. Qui nel 1928 trascorse la Settimana Santa e la Solennità Pasquale, favorita da grazie spirituali ineffabili. Il padre abate Raffaele Walzer divenne il suo nuovo direttore di spirito: egli pure la esortò a proseguire la sua opera feconda di apostolato del sapere nel mondo. Edith, per dedicarsi maggiormente all'attuazione di poderosi progetti filosofici, senza sottrarsi a continui inviti per conferenze di alto interesse, il 27 marzo 1931 lasciò Spira. Portò a termine la traduzione tedesca delle "Questioni discusse sulla verità" di S. Tommaso, edita in due volumi (1931-1932). Dopo alcuni tentativi per una libera docenza alle Università di Friburgo e Breslavia, ebbe la nomina a insegnante presso l'Istituto Superiore tedesco di pedagogia scientifica a Mlinster (primavera del 1932). Abitava in un collegio diretto dalle Suore di Nostra Signora ed edificava tutti per santità di vita e semplicità e delicatezza di modi. Sulla cattedra emergeva per profondità e chiarezza di insegnamento, per vigorosa difesa del pensiero cattolico.

Contribuì al ritorno a Dio di non poche persone specialmente giovani. Non mancava di stare accanto alla mamma, a Breslavia, e a sostenere e incoraggiare la sorella Rosa nel cammino verso la Chiesa. Studiò un piano di riforma dell'insegnamento universitario da sottoporre al competente Ministero.

Si occupò molto spesso del problema della donna: ne difese la dignità e il ruolo specifico nella società e nella Chiesa. Nel settembre 1932 prese parte a Juvisy, vicino a Parigi, ad un convegno di studiosi di fama internazionale sul tema "Fenomenologia e Tomismo" e tra gli altri conobbe anche J. Maritain. In ottobre andò ad Aquisgrana per un incontro su "L'atteggiamento spirituale della giovane generazione".

Ma ormai in Germania, con l'ascesa al potere di Adolf Hitler, non c'era più posto per chi era di stirpe ebraica. E così anche Edith Stein dovette lasciare l'insegnamento: il 25 febbraio 1933 tenne infatti l'ultima sua lezione universitaria. Presagendo quello che avrebbe significato per il suo popolo e la Chiesa, per la Germania e il mondo intero l'affermazione del nazional-socialismo, Edith si mostrò pronta ad accogliere la Croce di Cristo quale "unica speranza di salvezza".

Il sogno s'avvera: Carmelitana!

Libera finalmente di rispondere a quella vocazione claustrale che l'aveva attratta fin dal momento della conversione nel lontano 1921, si rivolse al Carmelo. Trascorsi a Breslavia due mesi accanto alla mamma diletta, che era addoloratissima per il passaggio della figlia al cattolicesimo, la vigilia della festa di Santa Teresa d'Avila del 1933, con eroica fortezza "varcò la soglia" del monastero di Colonia. I suoi quarantadue anni d età, la sua eccezionale cultura e la fama internazionale non le impedirono di divenire la religiosa più semplice, più mite, più pronta agli inconsueti mestieri di cucina e guardaroba. Fu una carmelitana povera e lieta. Immersa in Dio, visse di preghiera e di immolazione. Con la vestizione religiosa (che avvenne la domenica 15 aprile 1934), chiese di essere chiamata Teresa Benedetta della Croce. Fu una grande festa dello Spirito, appuntamento per gran numero di persone illustri. Lo stesso Husserl le inviò gli auguri.

II noviziato lo trascorse "nascosta con Cristo in Dio", attenta ai più minuti doveri. Era fedele alle amicizie, trepidante per la mamma veneranda, a cui inviava settimanalmente uno scritto filiale. Emise la professione temporanea (voti semplici) la domenica 21 aprile, giorno di Pasqua, del 1935. Quel giorno apparve trasfigurata dall'intima gioia, pronta a seguire dovunque l'Agnello senza macchia, quale sua "sposa". Fu di guida e sostegno alle consorelle più giovani.

edith-stein2

Suor Teresa Benedetta della Croce

Il 14 settembre 1936 perdette la mamma, di ottantasette anni: l'integrità di vita e la perfetta buona fede di lei le mitigarono il grande dolore. Il 14 dicembre successivo cadde e si fratturò un piede e una mano: portata in ospedale, potè intrattenersi più a lungo con la sorella Rosa, giunta da Breslavia a completare la sua preparazione al Battesimo per la vigilia di Natale del 1936.

Già da tempo il Padre Provinciale, conscio dei servizi inestimabili che Suor Teresa Benedetta poteva rendere alla scienza e alla religione, le aveva ordinato di rivedere e portare a termine la sua opera fondamentale: "Essere finito ed essere eterno''. Altri studi, altri scritti su argomenti diversi le vennero chiesti quasi senza interruzione; e lei vi si applicò in perfetta sottomissione, con notevole fatica per il tempo tanto limitato e frazionato, poiché non voleva mancare in nulla alla piena osservanza regolare, da degna figlia di Santa Teresa di Gesù.

Martire!

Il 21 aprile 1938 sigillò per l'eternità la sua consacrazione a Dio con la professione solenne (voti perpetui) seguita, dieci giorni dopo, dalla sacra velazione. Ma quell'anno il clima di feroce persecuzione hitleriana contro gli ebrei e contro la Chiesa costituiva un grave pericolo per Suor Teresa Benedetta, tanto più che, in occasione delle elezioni ella non nascose la più aperta condanna al mostruoso regime. La stessa esistenza del Carmelo di Colonia poteva essere compromessa dalla sua presenza. Perciò l'ultimo giorno dell'anno 1938 dovette separarsi dalle amate consorelle e riparare nascostamente in Olanda, presso le Carmelitane di Echt.

A Echt riprese serena la sua vita di silenzio adorante e di immolazione, quasi nulla fosse mutato. Imparò la lingua olandese e proseguì, per obbedienza, la sua attività scientifico-letteraria. In vista del centenario della nascita di San Giovanni della Croce (1942), intraprese nel 1941 uno studio sull'idea ispiratrice della vita e dell'opera del mistico Dottore, a cui diede per titolo "Scientia Crucis", che risultò una preparazione al suo martirio.

Iniziate le ostilità della guerra mondiale nell'autunno 1939, l'esercito nazista invase Belgio e Olanda nel 1940. L'odio contro gli ebrei giunse a tal punto che le Carmelitane di Colonia ritennero prudente distruggere lettere e scritti confidenziali della Stein, e le consorelle di Echt si adoperarono per trovarle un asilo in un Carmelo svizzero. Il nobile tentativo aggravò la situazione di suor Teresa Benedetta perché, costretta a presentarsi alla polizia nazista per i necessari documenti di emigrazione, venne notata per la sua origine e la sua impavida professione di fede cristiana. Cosicché, quando il 26 luglio 1942 nelle chiese cattoliche d'Olanda venne letta una famosa lettera collettiva dell'Episcopato contro la barbara persecuzione antiebraica in terra olandese, le sorelle Stein furono subito incluse nel numero delle vittime della ritorsione nazista. Alle cinque pomeridiane del 2 agosto, vennero improvvisamente prelevate, caricate su un carro d'assalto e brutalmente sospinte, con numerosi altri infelici, verso il loro ultimo destino.

Il dramma finale della Via Crucis, a cui Edith andò in contro consapevole e tranquilla, rispondeva a una sua lucida previsione. Già la Domenica di Passione del 1939 aveva chiesto alla sua M. Priora il permesso di offrirsi "vittima espiatrice" al Cuore di Gesù per la pace nel mondo, e su un immaginetta aveva scritto l'atto di offerta della propria vita per la conversione degli ebrei.

Le due sorelle Stein, condotte prima a Maastricht e poi ad Amersfoort, nella notte tra il 3 e il 4 di agosto arrivarono al campo di concentramento di Westerbok (Olanda). A persone di fiducia che poterono avvicinarle, Edith dichiarò: "Sono pronta a tutto". E alla Priora di Echt fece sapere: "Finora ho potuto pregare benissimo, e ho detto di tutto cuore: Ave Crux, spes unica!". Nel lager si prodigò a consolare e assistere mamme e piccoli in preda alla disperazione.

Nella notte tra il 6 e il 7 di agosto 1942, lei, Rosa e altri religiosi e molti cattolici vennero fatti partire verso il campo di sterminio di Auschwitz (Slesia). Edith il 9 agosto successivo, assieme alla sorella Rosa, entrò nella camera a gas e andò incontro a Cristo glorioso.

A guerra finita, la fama di questa eroica figlia della Chiesa, esponente esimia del popolo ebraico, si diffuse rapidamente per il mondo. Molti la presero presto come modello e la ritennero una martire data da Dio per indicare al mondo, e soprattutto al popolo ebraico, la via della Verità, che in Cristo purifica, illumina e svela "l'Essere eterno". Presso la Curia Arcivescovile di Colonia, dall'anno 1962 al 1972, furono preparati i processi canonici ordinari per la raccolta degli scritti e si raccolsero le testimonianze sulla sua fama di santità eroica. Il 1° maggio 1987 il Papa Giovanni Paolo II la beatificò a Colonia; il giorno 11 ottobre 1998 si celebrò la sua canonizzazione in Piazza San Pietro a Roma. Nel 1999 è stata dichiarata co-patrona d'Europa insieme a Santa Caterina di Siena e a Santa Brigida di Svezia.

di P. Rodolfo Girardello ocd

da Pregare, Anno 6, nn. 6-7, settembre-ottobre 1998.

https://www.carmeloveneto.it/joomla/s-teresa-benedetta-della-croce

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Your decrees are my inheritance forever; the joy of my heart they are.” Psalm 119:111 I like reading about saints. They were ordinary people who loved God extraordinarily. Because of their love for God, they were able to fear the Lord (which really means to be in awe of Him), love and serve Him. Today is the Feast Day of a Jewish woman who became a Discalced Carmelite nun. She was murdered in the gas chamber in Auschwitz-Birkenau along with her sister Rosa, who was also a Carmelite nun. St. Edith Stein, also known as St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, rejected her family’s Jewish piety and became an atheist at the age of 13. In 1917, a colleague, Professor Adolf Reinach, was killed in the war. When Edith met the the Professor’s wife Anna, she was deeply impressed with Anna’s strong Christian faith and convictions. She started reading the autobiography of St. Teresa of Avila and became drawn to the Catholic faith. After finishing the book, she declared, “This is the truth!” She was baptized on January 1, 1922. She was very intelligent and she continued studying and writing. She translated the writings of St. Thomas Aquinas into German. Soon she became a teacher and lecturer around Europe about the role of Catholic women. When it became difficult to teach because of Nazi restrictions, she entered the Carmelites as Sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross. She devoted her life to holiness and self-offering even as the Nazis forced her to wear the Star of David over her habit. St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross herself wrote, “I talked with the Savior and told Him that I knew that it was His cross that was now being placed on the Jewish people; that most of them did not understand this, but that those who did would have to take it up willingly in the name of all. I would do that. He should only show me how.” Yes, Lord, show us how. https://www.instagram.com/p/ChA9xpQBI4z/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

SetThings - Diviziunea analitic - continental în filosofie

https://www.setthings.com/ro/diviziunea-analitic-continental-in-filosofie/

Diviziunea analitic - continental în filosofie

Începutul diviziunii Bertrand Russell Filosofia continentală contemporană a început cu operele lui Franz Brentano, Edmund Husserl, Adolf Reinach și Martin Heidegger și dezvoltarea metodei filozofice a fenomenologiei. Această dezvoltare a fost aproximativ contemporană cu lucrările lui Gottlob Frege și Bertrand … Read More

0 notes

Photo

The Paschal mystery and vital experience in Edith Stein

On December 13, 1925, a few days before she celebrated the fourth anniversary of her baptism, Edith Stein wrote to her friend, the Polish philosopher Roman Ingarden. She talks about her university days in Gottingen and Freiburg in Breslau: «I was a bit like someone who is in danger of drowning […], before my soul stands the image of the dark and cold tomb. What else should there be except fright and infinite gratitude for the mighty arm that seized [you] and led [you] to a safe land? ».

How can this young Jewish intellectual, one of the first women to attend German university at the beginning of the 20th century, who was the brilliant student then the assistant of the great philosopher Edmond Husserl, say how to be «familiar with depressions»? And write the 6.10.1918: «The best way to accommodate this pitiful world would be to take leave».

During this terrible First World War, several events have deeply shaken:

– Death on the front of many students and death of the Magister Adolf Reinach

– In her work, the failure of the collaboration with Edmond Husserl

– In her emotional life, non-reciprocity in his love for Roman Ingarden

It took Edith to descend to the lowest point of the parable. It is there that the Lord came to meet her, to grasp her and give meaning to her life. On vacation in the summer of 1921 at her friends’ philosophers home, the Conrad-Martius, she reads the autobiography of Teresa of Avila, the great Spanish saint, reformer of Carmel; she will later write: «No one has penetrated as deep into the soul as those men [and women] who have embraced the world with a burning heart and were then freed from entanglement by the mighty hand of God and trained in their own interiority, in the greatest interiority».

The consequences are not long in coming. 6 months later, she receives baptism on 1.1.1922. To her friend and godmother, the philosopher Hedwig Conrad-Martius who questions her one day about what happened, she answers: «Secretum meum mihi» (= my secret is mine). These words express what Paul says about baptism: «You are dead, and your life is now hidden with Christ in God» (Col 3,3).

The secret of Edith is perhaps contained in the name of religion she received when she took the habit in the Carmel of Cologne, 15.4.1934: Sr Teresa Benedict of the Cross.

– Teresa – because of the influence of Teresa of Avila in her conversion,

– Benedicta – because a special link connects her to the Benedictines and St Benedict.

– «Of the Cross» is finally his «title of nobility» which «indicates that God wants to unite to him the soul under the sign of a particular mystery».

For Edith, Good Friday on Golgotha is the center of world history. In poverty, the loneliness of Christ, she finds her poverty and loneliness. As soon as she takes charge of this Cross («scientia crucis»), she realizes that it is an easy yoke and a light burden. The cross will be for her the stick that will lead easily to the heights.

In the suffering and death of Christ, our sins were destroyed by fire. When we accept this in our faith and receive the whole of Christ in a confident gift, which means that we choose and take the path of the imitation of Christ, he leads us through his suffering and his cross to the glory of his resurrection. It is the crossing of the expiatory fire towards the blessed union of love. After the dark night, begins to radiate the living flame of love.

http://www.carmelholylanddco.org/the-paschal-mystery-and-vital-experience-in-edith-stein/

0 notes

Photo

Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross - (Edith Stein) - Feast Day: August 9 - Ordinary Time

Teresa Benedict of the Cross Edith Stein (1891-1942) - nun, - Discalced Carmelite, martyr

"We bow down before the testimony of the life and death of Edith Stein, an outstanding daughter of Israel and at the same time a daughter of the Carmelite Order, Sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, a personality who united within her rich life a dramatic synthesis of our century. It was the synthesis of a history full of deep wounds that are still hurting ... and also the synthesis of the full truth about man. All this came together in a single heart that remained restless and unfulfilled until it finally found rest in God." These were the words of Pope John Paul II when he beatified Edith Stein in Cologne on 1 May 1987.

Who was this woman?

Edith Stein was born in Breslau on 12 October 1891, the youngest of 11, as her family were celebrating Yom Kippur, that most important Jewish festival, the Feast of Atonement. "More than anything else, this helped make the youngest child very precious to her mother." Being born on this day was like a foreshadowing to Edith, a future Carmelite nun.

Edith's father, who ran a timber business, died when she had only just turned two. Her mother, a very devout, hard-working, strong-willed and truly wonderful woman, now had to fend for herself and to look after the family and their large business. However, she did not succeed in keeping up a living faith in her children. Edith lost her faith in God. "I consciously decided, of my own volition, to give up praying," she said.

In 1911 she passed her exams with flying colors and enrolled at the University of Breslau to study German and history, though this was a mere "bread-and-butter" choice. Her real interest was in philosophy and in women's issues. She became a member of the Prussian Society for Women's Franchise. "When I was at school and during my first years at university," she wrote later, "I was a radical suffragette. Then I lost interest in the whole issue. Now I am looking for purely pragmatic solutions."

In 1913, Edith Stein transferred to Göttingen University, to study under the mentorship of Edmund Husserl. She became his pupil and teaching assistant, and he later tutored her for a doctorate. At the time, anyone who was interested in philosophy was fascinated by Husserl's new view of reality, whereby the world as we perceive it does not merely exist in a Kantian way, in our subjective perception. His pupils saw his philosophy as a return to objects: "back to things". Husserl's phenomenology unwittingly led many of his pupils to the Christian faith. In Göttingen Edith Stein also met the philosopher Max Scheler, who directed her attention to Roman Catholicism. Nevertheless, she did not neglect her "bread-and-butter" studies and passed her degree with distinction in January 1915, though she did not follow it up with teacher training.

"I no longer have a life of my own," she wrote at the beginning of the First World War, having done a nursing course and gone to serve in an Austrian field hospital. This was a hard time for her, during which she looked after the sick in the typhus ward, worked in an operating theatre, and saw young people die. When the hospital was dissolved, in 1916, she followed Husserl as his assistant to the German city of Freiburg, where she passed her doctorate summa cum laude (with the utmost distinction) in 1917, after writing a thesis on "The Problem of Empathy."

During this period she went to Frankfurt Cathedral and saw a woman with a shopping basket going in to kneel for a brief prayer. "This was something totally new to me. In the synagogues and Protestant churches I had visited people simply went to the services. Here, however, I saw someone coming straight from the busy marketplace into this empty church, as if she was going to have an intimate conversation. It was something I never forgot. "Towards the end of her dissertation she wrote: "There have been people who believed that a sudden change had occurred within them and that this was a result of God's grace." How could she come to such a conclusion? Edith Stein had been good friends with Husserl's Göttingen assistant, Adolf Reinach, and his wife.

When Reinach fell in Flanders in November 1917, Edith went to Göttingen to visit his widow. The Reinachs had converted to Protestantism. Edith felt uneasy about meeting the young widow at first, but was surprised when she actually met with a woman of faith. "This was my first encounter with the Cross and the divine power it imparts to those who bear it ... it was the moment when my unbelief collapsed and Christ began to shine his light on me - Christ in the mystery of the Cross." Later, she wrote: "Things were in God's plan which I had not planned at all. I am coming to the living faith and conviction that - from God's point of view - there is no chance and that the whole of my life, down to every detail, has been mapped out in God's divine providence and makes complete and perfect sense in God's all-seeing eyes."

In Autumn 1918 Edith Stein gave up her job as Husserl's teaching assistant. She wanted to work independently. It was not until 1930 that she saw Husserl again after her conversion, and she shared with him about her faith, as she would have liked him to become a Christian, too. Then she wrote down the amazing words: "Every time I feel my powerlessness and inability to influence people directly, I become more keenly aware of the necessity of my own holocaust."

Edith Stein wanted to obtain a professorship, a goal that was impossible for a woman at the time. Husserl wrote the following reference: "Should academic careers be opened up to ladies, then I can recommend her whole-heartedly and as my first choice for admission to a professorship." Later, she was refused a professorship on account of her Jewishness.

Back in Breslau, Edith Stein began to write articles about the philosophical foundation of psychology. However, she also read the New Testament, Kierkegaard and Ignatius of Loyola's Spiritual Exercises. She felt that one could not just read a book like that, but had to put it into practice.

In the summer of 1921. she spent several weeks in Bergzabern (in the Palatinate) on the country estate of Hedwig Conrad-Martius, another pupil of Husserl's. Hedwig had converted to Protestantism with her husband. One evening Edith picked up an autobiography of St. Teresa of Avila and read this book all night. "When I had finished the book, I said to myself: This is the truth." Later, looking back on her life, she wrote: "My longing for truth was a single prayer."

On 1 January 1922 Edith Stein was baptized. It was the Feast of the Circumcision of Jesus, when Jesus entered into the covenant of Abraham. Edith Stein stood by the baptismal font, wearing Hedwig Conrad-Martius' white wedding cloak. Hedwig washer godmother. "I had given up practising my Jewish religion when I was a 14-year-old girl and did not begin to feel Jewish again until I had returned to God." From this moment on she was continually aware that she belonged to Christ not only spiritually, but also through her blood. At the Feast of the Purification of Mary - another day with an Old Testament reference - she was confirmed by the Bishop of Speyer in his private chapel.

After her conversion she went straight to Breslau: "Mother," she said, "I am a Catholic." The two women cried. Hedwig Conrad Martius wrote: "Behold, two Israelites indeed, in whom is no deceit!" (cf. John 1:47).

Immediately after her conversion she wanted to join a Carmelite convent. However, her spiritual mentors, Vicar-General Schwind of Speyer, and Erich Przywara SJ, stopped her from doing so. Until Easter 1931 she held a position teaching German and history at the Dominican Sisters' school and teacher training college of St. Magdalen's Convent in Speyer. At the same time she was encouraged by Arch-Abbot Raphael Walzer of Beuron Abbey to accept extensive speaking engagements, mainly on women's issues. "During the time immediately before and quite some time after my conversion I ... thought that leading a religious life meant giving up all earthly things and having one's mind fixed on divine things only. Gradually, however, I learnt that other things are expected of us in this world... I even believe that the deeper someone is drawn to God, the more he has to `get beyond himself' in this sense, that is, go into the world and carry divine life into it."

She worked enormously hard, translating the letters and diaries of Cardinal Newman from his pre-Catholic period as well as Thomas Aquinas' Quaestiones Disputatae de Veritate. The latter was a very free translation, for the sake of dialogue with modern philosophy. Erich Przywara also encouraged her to write her own philosophical works. She learnt that it was possible to "pursue scholarship as a service to God... It was not until I had understood this that I seriously began to approach academic work again." To gain strength for her life and work, she frequently went to the Benedictine Monastery of Beuron, to celebrate the great festivals of the Church year.

In 1931 Edith Stein left the convent school in Speyer and devoted herself to working for a professorship again, this time in Breslau and Freiburg, though her endeavours were in vain. It was then that she wrote Potency and Act, a study of the central concepts developed by Thomas Aquinas. Later, at the Carmelite Convent in Cologne, she rewrote this study to produce her main philosophical and theological oeuvre, Finite and Eternal Being. By then, however, it was no longer possible to print the book.

In 1932 she accepted a lectureship position at the Roman Catholic division of the German Institute for Educational Studies at the University of Munster, where she developed her anthropology. She successfully combined scholarship and faith in her work and her teaching, seeking to be a "tool of the Lord" in everything she taught. "If anyone comes to me, I want to lead them to Him."

In 1933 darkness broke out over Germany. "I had heard of severe measures against Jews before. But now it dawned on me that God had laid his hand heavily on His people, and that the destiny of these people would also be mine." The Aryan Law of the Nazis made it impossible for Edith Stein to continue teaching. "If I can't go on here, then there are no longer any opportunities for me in Germany," she wrote; "I had become a stranger in the world."

The Arch-Abbot of Beuron, Walzer, now no longer stopped her from entering a Carmelite convent. While in Speyer, she had already taken a vow of poverty, chastity and obedience. In 1933 she met with the prioress of the Carmelite Convent in Cologne. "Human activities cannot help us, but only the suffering of Christ. It is my desire to share in it."

Edith Stein went to Breslau for the last time, to say good-bye to her mother and her family. Her last day at home was her birthday, 12 October, which was also the last day of the Feast of Tabernacles. Edith went to the synagogue with her mother. It was a hard day for the two women. "Why did you get to know it [Christianity]?" her mother asked, "I don't want to say anything against him. He may have been a very good person. But why did he make himself God?" Edith's mother cried. The following day Edith was on the train to Cologne. "I did not feel any passionate joy. What I had just experienced was too terrible. But I felt a profound peace - in the safe haven of God's will." From now on she wrote to her mother every week, though she never received any replies. Instead, her sister Rosa sent her news from Breslau.

Edith joined the Carmelite Convent of Cologne on 14 October, and her investiture took place on 15 April, 1934. The mass was celebrated by the Arch-Abbot of Beuron. Edith Stein was now known as Sister Teresia Benedicta a Cruce - Teresa, Blessed of the Cross. In 1938 she wrote: "I understood the cross as the destiny of God's people, which was beginning to be apparent at the time (1933). I felt that those who understood the Cross of Christ should take it upon themselves on everybody's behalf. Of course, I know better now what it means to be wedded to the Lord in the sign of the cross. However, one can never comprehend it, because it is a mystery." On 21 April 1935 she took her temporary vows. On 14 September 1936, the renewal of her vows coincided with her mother's death in Breslau. "My mother held on to her faith to the last moment. But as her faith and her firm trust in her God ... were the last thing that was still alive in the throes of her death, I am confident that she will have met a very merciful judge and that she is now my most faithful helper, so that I can reach the goal as well."

When she made her eternal profession on 21 April 1938, she had the words of St. John of the Cross printed on her devotional picture: "Henceforth my only vocation is to love." Her final work was to be devoted to this author.

Edith Stein's entry into the Carmelite Order was not escapism. "Those who join the Carmelite Order are not lost to their near and dear ones, but have been won for them, because it is our vocation to intercede to God for everyone." In particular, she interceded to God for her people: "I keep thinking of Queen Esther who was taken away from her people precisely because God wanted her to plead with the king on behalf of her nation. I am a very poor and powerless little Esther, but the King who has chosen me is infinitely great and merciful. This is great comfort." (31 October 1938)

On 9 November 1938 the anti-Semitism of the Nazis became apparent to the whole world.

Synagogues were burnt, and the Jewish people were subjected to terror. The prioress of the Carmelite Convent in Cologne did her utmost to take Sister Teresia Benedicta a Cruce abroad. On New Year's Eve 1938 she was smuggled across the border into the Netherlands, to the Carmelite Convent in Echt in the Province of Limburg. This is where she wrote her will on 9 June 1939: "Even now I accept the death that God has prepared for me in complete submission and with joy as being his most holy will for me. I ask the Lord to accept my life and my death ... so that the Lord will be accepted by His people and that His Kingdom may come in glory, for the salvation of Germany and the peace of the world."

While in the Cologne convent, Edith Stein had been given permission to start her academic studies again. Among other things, she wrote about "The Life of a Jewish Family" (that is, her own family): "I simply want to report what I experienced as part of Jewish humanity," she said, pointing out that "we who grew up in Judaism have a duty to bear witness ... to the young generation who are brought up in racial hatred from early childhood."

In Echt, Edith Stein hurriedly completed her study of "The Church's Teacher of Mysticism and the Father of the Carmelites, John of the Cross, on the Occasion of the 400th Anniversary of His Birth, 1542-1942." In 1941 she wrote to a friend, who was also a member of her order: "One can only gain a scientia crucis (knowledge of the cross) if one has thoroughly experienced the cross. I have been convinced of this from the first moment onwards and have said with all my heart: 'Ave, Crux, Spes unica' (I welcome you, Cross, our only hope)." Her study on St. John of the Cross is entitled: "Kreuzeswissenschaft" (The Science of the Cross).

Edith Stein was arrested by the Gestapo on 2 August 1942, while she was in the chapel with the other sisters. She was to report within five minutes, together with her sister Rosa, who had also converted and was serving at the Echt Convent. Her last words to be heard in Echt were addressed to Rosa: "Come, we are going for our people."

Together with many other Jewish Christians, the two women were taken to a transit camp in Amersfoort and then to Westerbork. This was an act of retaliation against the letter of protest written by the Dutch Roman Catholic Bishops against the pogroms and deportations of Jews. Edith commented, "I never knew that people could be like this, neither did I know that my brothers and sisters would have to suffer like this. ... I pray for them every hour. Will God hear my prayers? He will certainly hear them in their distress." Prof. Jan Nota, who was greatly attached to her, wrote later: "She is a witness to God's presence in a world where God is absent."

On 7 August, early in the morning, 987 Jews were deported to Auschwitz. It was probably on 9 August that Sister Teresia Benedicta a Cruce, her sister and many other of her people were gassed.

When Edith Stein was beatified in Cologne on 1 May 1987, the Church honoured "a daughter of Israel", as Pope John Paul II put it, who, as a Catholic during Nazi persecution, remained faithful to the crucified Lord Jesus Christ and, as a Jew, to her people in loving faithfulness."

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

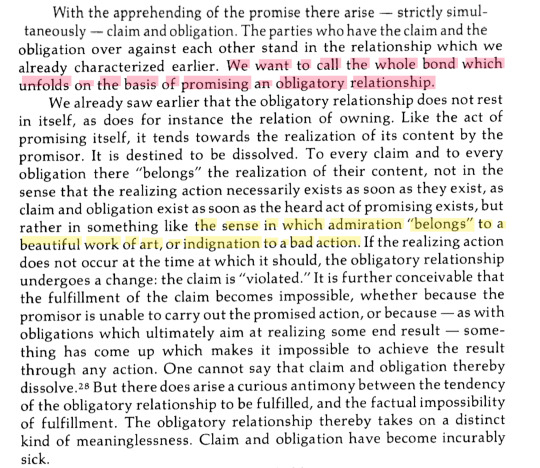

The disinterested promise given out of friendship of course obliges in exactly the same sense as the most self-regarding promise. This cannot be understood on Hume's terms.

There is only one thing which Hume could perhaps make understandable through his analysis: that self-interest originally made men keep and fulfill their promises and their obligations. What would be explained here would be the influence of self-interest on the tendency to do the thing promised; but this is by no means the phenomenologically quite distinct experience of feeling oneself bound by the promise. What is the leap whereby one wants to get from the one experience to the other?

But furthermore and above all, it is not a matter of the experience of feeling bound, which considered in itself can be founded or unfounded [e.g. feeling obliged to do something when no obligation actually exists], but rather of the obligation itself and of the claim... proceeding from the act of promising. Both of these are utterly unlike experiences. That this is so cannot be "explained" at all. One can only come to see it and to understand it by bringing to clarity the distinct act of promising and the essential relations grounded in it.

Adolf Reinach, The Apriori Foundations of the Civil Law tr. John F. Crosby

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Choreo-)Graphic acts

1.

Everytime something starts, the law starts too, because starting is a juridical and cultural technique.

In Warburg's sense an act may be a movement (also in the sense of animation and in the sense of something, in which/ by which movement goes through). An act may be a movement, that is giving and given a word, that is giving and given an image, that is given and giving orientiation and that is giving and given action.

Warburg starts to think of/about those acts by using the example of the mancipatio in 1896. In 1912 his thoughts on/ about the movement, that he is interested in, had made a turn, that makes his work interesting for me: He associated the movement with polarity and thought of polarity not only in terms of coping with binaries.

Polar are all those movements, in which a turn, a bend, a wind or a folding appears. Polar are movements, that appear through turning, bending, winding, sweeping or folding. The may be a psychological polarity, it may be a geographical (spacial), a historical (temporal) or a social (associating) polarity. And: the biggest polar object on earth is earth itself, bigger than the earth and a polar thing too is only the kosmos: He is turning and he turns Warburg on. 1912 he is looking at images that are calendars and that operationalize times and turns. Warburg has read Franz Boll and became a specialist for the history of astronomy and astrology - that was also the reason, why Walter Benjamin was so interested in Warburg.

2.

For Warburg times and turns were interesting, because they were a 'meteorological problem', a problem of something/ everything, of some same things, that are to measure and to calculate, but that are not easy to measure and not easy to calculate.

This problem is linked to questions that may be stabilized oder stabilizing, when and if you answer them. But the answers do not have to stabilize and be stabilized. They may get along with instability. The (choreo-)graphic acts, Warburg compared with each others were the mancipatio, the signing of the lateran treaties and a dance of people in New Mexico ("Schlangenritual"). They are the same but not equal.

Warburg is a Reinachreader. They are traces in his Zettelkasten. That he is a Reinachreader is important to know. But the most important think is to understand, how he reads him. And that is not a question of substance, of content. It is a matter of matter, a question of the materiality of reading and of the cultral techniques of reading. This is sure: Warburg does not read systematically. He read in parts and by parting and by jumping forward and backward while he is reading. The system is the total asylum, closed operations make Warburg nuts. He is a dancer, a rover, a stroller. I am sure that this is the way he reads, because everything he does he does this way.

Since i have listened to Kimberly Baltzer Jaray and since i saw her tattoos including Adolf Reinach on her legs (that is lex) i may know why Warburg is reading Reinach. Her lex and her legs let Kimberly move and let her walk the line. Now Reinach and Warburg are linked and inked. The lines that link and ink Warburg and Reinach embody that kind of transit, that Thomas Hobbes calls 'meterorological', they are letters, that let appear and let dissappear but only by moving lines and mvong the border beetween visibility and invisibility. Theses lines seem to be here and not here, but they only are in different distances. This is not a question of substantial identity, it is a question of relational affinities.

The germans used to use a verb for a movement, that directs meteorological: they used the verb lingen (ich linge, du lingst, er/sie/es lingen. This verb has an afterlife in the englisch Verb to link and in the german Word gelingen.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“La verdadera felicidad se encuentra en dedicar nuestra vida a un propósito más grande que nosotros mismos”

Edith Stein

Fue una filósofa, mística religiosa, mártir y santa alemana de origen judío nacida en Breslavia imperio alemán hoy Polonia en octubre de 1891.

Nació en el seno de una familia judía, su padre era dueño de un aserradero y fue la séptima hija de un total de 11 hijos del matrimonio, y como tal vivió las raíces hebreas familiares y el nacionalismo prusiano.

Desde muy temprana edad mostró especial interés por la historia y la literatura alemanas y de las grandes figuras de la música como Bach, Mozart y Wagner.

A la edad de 15 años experimentó una etapa de ateísmo y crisis existencial, causada por el suicidio de dos de sus tíos y a la falta de respuesta de la religión al tema del más allá. Abandona el colegio y se traslada a Hamburgo para asistir a su hermana Elsa quien iba a tener un hijo.

En 1913, la lectura de “las investigaciones lógicas“ de Husserl le abrió una nueva perspectiva en vista a su orientación objetivista, por lo que decide trasladarse a Gotinga a terminar los cursos universitarios y por ejercer Husserl allí su magisterio.

En Friburgo, en 1917, aprobó con la calificación de summa cum laude su tesis doctoral titulada “Sobre el problema de la empatía”, tema que le sugirió Max Scheler, con el que inició sus obras filosóficas.

Como estudiante de filosofía, fue la primera mujer que presentó una tesis en esta disciplina en Alemania.

Gracias a su amigo Georg Moskiewicz, Edith Stein fue aceptada en la sociedad de la filosofía de Gotinga, que reunía a los principales miembros de la fenomenología naciente como Edmund Husserl, Adolf Reinach y Max Scheler, y durante estos encuentros una correspondencia personal y profunda con el filósofo, ontólogo y teórico literario Roman Ingarden así como con el filósofo francés de origen ruso Alexandre Koyré.

Durante la primera guerra mundial Edith Stein decidió regresar a Breslau, tomó cursos de enfermería y trabajó en un hospital austriaco. Cuando el hospital fue cerrado, Edith regresó a reanudar sus estudios filosóficos con Husserl obteniendo un doctorado en la Universidad de Friburgo.

Una vez obtenido el doctorado, se enroló en la cruz roja en donde fue enviada a ocuparse de los enfermos de problemas infecciosos y trabajo en salas de operaciones, obtuvo una medalla por su dedicación y debido a lo precaria de su condición de salud fue enviada a su casa y no la llamaron mas.

Estas experiencias con los jovenes que morían a muy temprana edad de todas partes de Europa del Este, la marcaron profundamente, y poco a poco fue acercándose a la fé católica, la entereza con la que su amiga Ana Reinach, sobrellevó la muerte de su joven esposo, una vez que ambos fueron bautizados así como su acercamiento a los escritos de Santa Teresa de Jesús, y la entrada en una iglesia católica de Frankfurt en donde reparó la presencia del santísimo, hizo que se decidiera a ser bautizada en enero de 1922.

Durante esta época, dedica parte de su vida a la docencia con poco éxito para ofrecer cátedra en universidades, por lo que se dedica a dar clases particulares de fenomenología y ética en Breslau y en ocasiones pronuncia conferencias en congresos de pedagogía en Alemania, Austria y Suiza.

En octubre de 1933 ingresa al Carmelo de Colonia y rehusa marcharse a Iberoamérica para huir del nacional socialismo prefiriendo permanecer junto a los suyos, hasta que el 31 de diciembre de 1938, tras “la noche de los cristales” es trasladada al Carmelo holandés de Echt que para entonces era un país neutral, sin embargo esto no impide su deportación en 1940 junto con 244 judíos católicos mas tarde, y ser llevada a las cámaras de gas de Auschwitz-Birkenau en donde muere en compañía de su hermana Rosa.

Durante su estadía en Auschwitz cuida de los niños encerrados en ese campo, los acompaña con compasión hacia la muerte y les enseña el Evangelio a los detenidos.

Fueron conmovedores relatos de sus últimos días dando ánimo a las demás profesas, haciendo que el papa Juan Pablo II la canonizara como Santa Teresa Benedicta de la Cruz en octubre de 1988.

Su sólida visión de personalista cristiana forjada entre la fenomenología, el tomismo y la mística, es fruto de una pasión que supo encauzar con audacia en medio de una vida singular, fruto de un arduo camino intelectual y vital que el hombre de la primera mitad del siglo XX se exponía con el materialismo, el nihilismo, el hedonismo, la xenofobia y el nazismo de su época.

Fuente: Wikipedia y philosophica.info, personalismo.org, vaticannews.va

#alemania#filosofos#citas de reflexion#frases de reflexion#notasfilosoficas#citas de la vida#citas de escritores#notas de vida#segunda guerra mundial#teologos#teologia#santos#christianity

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Whoever wishes to come after me must deny himself, take up his cross and follow me.” Matthew 16:24 I like reading about saints. They were ordinary people who loved God extraordinarily. Because of their love for God, they were able to deny themselves, take up their crosses and follow Jesus. Today is the Feast Day of a Jewish woman who became a Discalced Carmelite nun. She was murdered in the gas chamber in Auschwitz-Birkenau along with her sister Rosa, who was also a Carmelite nun. St. Edith Stein, also known as St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, rejected her family’s Jewish piety and became an atheist at the age of 13. In 1917, a colleague, Professor Adolf Reinach, was killed in the war. When Edith visited Anna, his wife, she was deeply impressed with her Christian faith. She started reading the autobiography of St. Teresa of Avila and became drawn to the Catholic faith. After finishing the book, she declared, “This is the truth!” She was baptized on January 1, 1922. She was very intelligent and she continued studying and writing. She translated the writings of St. Thomas Aquinas into German. Soon she became a teacher and lecturer around Europe about the role of Catholic women. When it became difficult to teach because of Nazi restrictions, she entered the Carmelites as Sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross. She devoted her life to holiness and self-offering even as the Nazis forced her to wear the Star of David over her habit. St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross herself wrote, “I talked with the Savior and told Him that I knew that it was His cross that was now being placed on the Jewish people; that most of them did not understand this, but that those who did would have to take it up willingly in the name of all. I would do that. He should only show me how.” Yes, Lord, show us how. https://www.instagram.com/p/B068H5NnJub/?igshid=1u35ve0wz815w

0 notes

Text

Adolf Reinach, The Apriori Foundations of the Civil Law tr. John F. Crosby

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note