#ABC San Francisco

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Thoughts on Full House?

#full house#sitcoms#80s#90s#tv shows#warner bros#lorimar#abc#tgif#san francisco#california#family#mary kate and ashley olsen#jeff franklin#miller boyett#nostalgia#childhood#retro

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

SF Yimby, in their story on the Transamerica Pyramid, featuring an earlier design by architects William L. Pereira & Associates:

The unbuilt ABC Tower in New York early study of elevator travel times, illustration by William L Pereira & Associates courtesy the USC Library

#image#abc tower#new york#new york city#unbuilt#architecture#san francisco#transamerica pyramid#william pereira#design#blueprint#architectural drawing#skyscraper

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Streets on San Francisco intro

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

#animated gif#animated gifs#gif#gifs#old advertisements#old ads#retro#vhs#animation#animated#ABC#logo#san francisco#7#80s

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dot Dash

#Dot Dash#architecture#design#studio#New York#San Francisco#portfolio#black#type#typeface#font#ABC Diatype#2023#Week 48#website#web design#inspire#inspiration#happywebdesign

0 notes

Text

ABC 7Live San Francisco 4.9.12

0 notes

Text

ABC 7Live San Francisco 4.9.12

0 notes

Text

The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake interrupts feed of the ongoing World Series in San Francisco

Coverage by ABC

5:04 PM PDT (0004Z) 1989/10/17

[x]

#broadcastnewsarchive#broadcast news#history#abc#american broadcasting corporation#world series#loma prieta earthquake#san francisco

0 notes

Text

Can Our United States PLEASE Arrest Kids and Their Parents Who Are Sneakily Destroying Gay Men to Gay Men Online Dating in which they “trick” innocent Gay Adults who are ONLY interested in Gay men into talking to bratty kids Online!??? Cops are destroying Romantic Adult Relationships Online on Online Adult Dating Apps by shoving Kids on the Online Adult Dating Apps as Bait at the Expense of Adult Online Dating Customers who are working hard Over-Time and paying taxes and Online Adult Dating App Memberships for Police Officers to get in the Way of Commerce meant for Adults-to-Adults Consensuality! Cut Our Taxes! Cops, Parents and their Kids ARE the True Pedophiles looking for Pedophilia! Even Adults who pretend to be Gay pose as children as Bait to just get money in having innocent people arrested after membership fees to Online Dating Adult Apps! Gay Men’s Gay Men-to-Gay Men Love Lives are now ruined in which Gay men are being forced to rape innocent women or live out in the Streets homeless without another Adult Gay man sharing Living Expenses such as Rent, Mortgages and Tax Credits! Now Adults are being forced to defecate on Front Lawns of people’s homes because of High Republican Rents for swimming pools Everywhere and High Profits and High Taxes from Democrats!

#abc news#abcnews#abc7eyewitness#fox nation#fox network#fox news#texas tribune#houston chronicle#sfchronicle#san francisco chronicle#marco rubio#ted cruz#rick scott#ron desantis#governor phil murphy#governor ron desantis#governor greg abbott#marjorie taylor greene

0 notes

Text

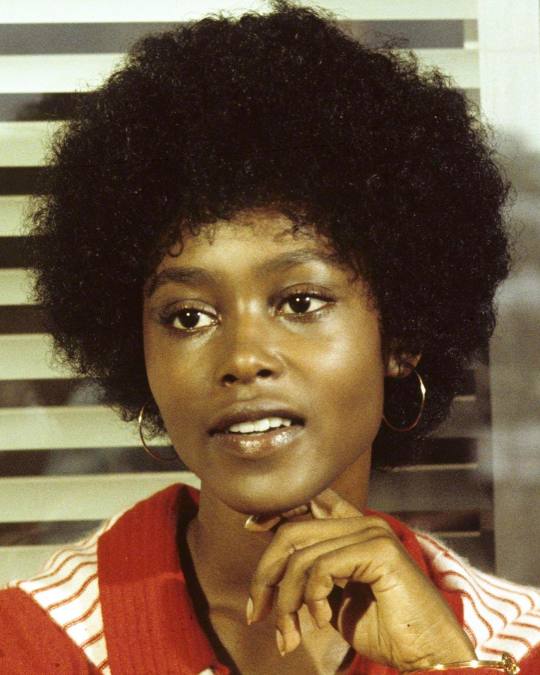

Brenda Sykes photographed on set of the ABC TV show "The Streets of San Francisco" - Airdate: January 6, 1973.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ahmed Fouad Alkhatib had a cold the first time that I reached him on the phone at his home in Pacifica, California, in June. It was the unwanted souvenir of a hectic travel schedule, as amid the war in Gaza, the 34-year-old Palestinian American—who spent much of his childhood there—has emerged as a compelling voice for peace.

Alkhatib’s vision, both pragmatic and humane, as well as his personal story, has made him an in-demand voice in the U.S. and Israeli media. While he is sought out by those looking for an antidote to despair, he is no Pollyannaish peacenik.

“I feel absolutely fucking horrendous,” he said between coughs, approximately 30 seconds into our first phone conversation.

Alkhatib’s rise to prominence began in the wake of the Hamas-led attacks of Oct. 7, 2023, when he began tweeting and writing with an awareness that he had the safety and security to say things that Palestinians living in Gaza or the West Bank could not.

“Ahmed is unique because he does speak out, and he takes a lot of shit for it,” said Gershon Baskin, an Israeli hostage negotiator and longtime ally of Alkhatib’s. “He’s a very clear, sound voice for peace, reason, and logic.”

In outlets including the Wall Street Journal, the Atlantic, Foreign Policy, and the Times of Israel, as well as appearances on CNN, ABC, and NPR, Alkhatib has outlined positions that would seem self-evident if the discourse weren’t otherwise so profoundly broken.

Hamas, he believes, is nothing but bad news for his people, and he has condemned the group with such ferocity that it has at times earned him a security detail. He has also spoken out about the unsparing nature of Israel’s military campaign while underscoring the need for empathy for both Israeli and Palestinian victims.

“This off-the-shelf messaging came down” in the wake of the Hamas-led attacks, Alkhatib told me. “There was no space, whatsoever, to call for the release of hostages. I was equally horrified by the dehumanization of all Gazans as terrorists.”

Alkhatib describes himself as proudly pro-Palestinian, once spearheading a project to establish a humanitarian airport in Gaza. At the same time, he is a trusted broker among progressive Jewish and Israeli circles. Most extraordinary of all, he retains this clarity even though 31 members of his family have been killed in Israeli airstrikes in Gaza since the war began.

“He recognizes something that a lot of policymakers don’t recognize,” said Jasmine El-Gamal, a former official at the U.S. Defense Department who now runs a consulting firm focused on empathy in foreign policy. “You won’t have that genuine sustainable peace if people on both sides don’t see the other as human. You’re just not going to have it.”

Alkhatib first came by himself to the United States in 2005, as part of a post-9/11 State Department program that brought young people from the Muslim world to study at U.S. high schools.

At 15, he was placed by the program in Pacifica, a small town on the Pacific Ocean located just south of San Francisco. His host mother, Delia McGrath, was a prominent peace activist in the area who preached the importance of nonviolence.

“That really got through to him and entered his DNA,” said Paul Totah, a Palestinian American from Pacifica who has known Alkhatib since he arrived in the area. “Despite the fact that 31 of his relatives were blown to bits by Israel,” Totah added, “he is firm in his belief that the bullet does not outweigh the word.”

McGrath, a former Catholic nun who later turned to Buddhism, participated in a Jewish-Palestinian dialogue group in the Bay Area. Alkhatib immediately wanted to join. It was in California that he had his first sustained encounters with Israelis and Jews, who until then he had only seen from afar at checkpoints in Gaza.

“We were told that’s anathema to our struggle—we don’t talk to them, we don’t normalize them, and we don’t embrace them,” he recalled.

There were moments of tension as the dialogue group struggled to bridge the largely historic trauma of the American Jewish participants and the ongoing ordeal experienced by the Palestinians.

But over time, hearing from descendants of Holocaust survivors as well as Israelis who had lived through the terror of the Second Intifada—a violent Palestinian uprising against Israeli rule that was marked by widespread protests and attacks that killed more than 1,000 Israelis—Alkhatib had an epiphany.

“This is where I learned early on that trauma and suffering don’t have to be an oppression Olympics,” he said. “Their suffering isn’t less valid just because they didn’t grow up in Gaza or didn’t live under checkpoints in the West Bank.”

Talk of intercommunal dialogue can feel flimsy considering the bloodshed of the past 14 months. But it’s equally difficult to see how a sustainable peace can be achieved without it.

“We need multilateralism as part of the top-down political solution,” Alkhatib said, adding that for peace and coexistence, “we need Palestinians and Israelis to bilaterally work together.”

Scott Fitzgerald is credited with saying that the test of a first-rate intelligence is a person’s ability to hold two opposed ideas in their head at the same time and still retain the ability to function. It is a test that many fail when it comes to the Middle East. Palpably frustrated with the zero-sum debate, Alkhatib brings to mind the American novelist’s maxim and talks frequently about the need to hold multiple truths at the same time.

Irritated by some of Palestine’s supporters in the United States who have advocated for boycotts of businesses with few ties to the conflict, he also has little time for participants in university campus protests who appeared to justify and glorify the Oct. 7 attacks as legitimate acts of resistance.

“We have fucking horrible allies,” Alkhatib said. “I want a vibrant, strong, pro-Palestine movement. I want a movement that’s based on empathy and humanity. That calls out the injustices of the occupation and the settlements, but that acknowledges that Israel is a fait accompli.”

Baskin, the Israeli hostage negotiator, said that Alkhatib has something rare: “He knows how to speak to Jewish audiences, which is a unique ability for a Palestinian.”

I saw Alkhatib do exactly this at a screening in July of Screams Before Silence, a documentary championed by former Facebook Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg about sexual violence carried out by the Hamas-led attackers.

Allegations of rape and sexual assault on Oct. 7 have become a lightning rod for some of Israel’s critics, particularly on the U.S. left, some of whom have sought to downplay and even deny claims that have been supported by the United Nations and the testimonies of survivors and first responders.

In light of efforts to minimize these accounts, Alkhatib felt it was important to accept an invitation to appear on a panel following a screening at Los Angeles’s Saban Theatre, which is owned by a local Jewish congregation.

“I can feel empathy for Israeli women; I can feel sadness and horror; I can talk to Israeli hostage families as I have,” he told the audience from the stage of the art deco theater, where he spoke alongside other Muslim American and Jewish peace advocates. “I am also critical of the war and the killing of my family members, children as young as 3 and 4 months old shredded to pieces.”

In opening remarks, the panel’s moderator said, inaccurately, that Alkhatib’s entire family had been killed in the war.

As a child, Alkhatib hoped to one day become a politician or diplomat; his parents were perplexed by his early interest in the news and his preference for sitting with the adults. Today, he is every bit the jovial uncle who loves to talk about politics at the dinner table, barrel-chested with a warm smile and shaved head.

That discursive side of Alkhatib was on show when we met for lunch at a Mediterranean restaurant on Los Angeles’s Sunset Boulevard the day after the screening. Over a mezze platter of Middle Eastern staples, he unspooled the life story that led him to eating hummus, tahini, and an errant dish of guacamole in sunny California—including his childhood in Gaza, where he became a master kite builder, and his journey to study in the United States, where he received political asylum as Hamas violently seized control of the territory in 2007.

He paused briefly during the conversation to flag down the server. “The salad, chopped-up little side salad,” Alkhatib asked, attempting to order a dish while deliberately avoiding its commonly used name.

“Israeli salad?” the waitress asked.

“That one,” he said.

Alkhatib counts many Israelis as friends and allies in his work and recognizes the country as here to stay. But he draws a line at their claim to a salad that is eaten across the Middle East.

“We literally ate this 24/7,” he said in a rare moment of obstinance.

Alkhatib was born in 1990 in the mountainous Asir region of Saudi Arabia, where his father, Fouad Alkhatib, worked as a doctor. The family vacationed in Gaza every summer and spent two years there in the late 1990s before moving back to the area permanently in 2000.

Alkhatib’s father used the money that he earned in Saudi Arabia to build a multistory family home in Gaza City’s al-Yarmouk neighborhood. Each unit of the family—including grandparents and uncles—had its own floor.

“It’s like Thanksgiving and Christmas every day,” Alkhatib said. His mother’s family, the Shehadas, lived in a similar multifamily home in Rafah’s Brazil neighborhood, which takes its name from the barracks of Brazilian U.N. peacekeepers who were once stationed in the area.

One of Alkhatib’s earliest memories is of sitting in the large yard of the Shehada family home. His grandmother, Maryam, had lined the garden with olive, fig, and guava trees, which fed the family year-round.

During the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Maryam’s family fled Hamama, an agricultural village to the north of the present-day Gaza border, ending up in a refugee camp in Rafah. After her husband died, Maryam grew vegetables and sold ducks and chickens to support herself and her six children. Out of habit, she continued to breed them well into her retirement. Lovely but tough with a rural “felahi” accent, she was a living connection to a bygone era in the family’s history.

Alkhatib was 10 when his family returned to Gaza permanently, four months before the Second Intifada began in September 2000. Some 3,000 Palestinians were killed by Israel’s response to the uprising.

Alkhatib vividly remembers Hamas members coming to his school, banging on the windows, and urging the children to come out and protest or go to the border fence to throw rocks at Israeli checkpoints.

“Sometimes there would be buses that would take students to the borders,” he said.

As the intifada raged, Israel responded with airstrikes across the territory. The sound of loitering Apache attack helicopters menaced Gaza City as they homed in on their targets. Fighter jets came with little warning.

On the afternoon of Dec. 4, 2001, Alkhatib was walking home from school in the Sheikh Radwan district of Gaza City when an Israeli airstrike hit a nearby Palestinian Authority building. He ran toward the flames and billowing clouds of dust to see if his friends, Mohammed, Rajab, and Ali—who had been dragging their heels behind him—were OK. Then a second strike hit. The blast wave jolted his young body, causing permanent hearing damage in his left ear.

Confused and covered in ash, Alkhatib ran home, leaping over a passed-out bystander along the way. It was only the next day that he learned that two of his friends, Mohammed and Rajab, had been killed.

Life in Gaza wasn’t easy, but Alkhatib’s memories of the period are also infused with happy childhood staples: summer days spent on the beach and playing video games with his cousins late into the night, which he credits with improving his English.

“I have some fucking amazing memories in Gaza,” he said.

An extended family that ran to well over 100 people served as the bedrock of his social world.

His aunt Zainab, the family matriarch, would regularly host the family for large gatherings at the Shehada home. The smell of her cooking wafted through the air when one reached the front door, Alkhatib remembered, as inside she prepared vast quantities of fragrant chicken and rice in large pressure cookers that shot off steam.

“You never entered her house and left hungry,” he said.

In the wake of Israel’s ground invasion of Gaza in late 2023, Zainab Shehada and her brother-in-law—Abdullah Shehada, a 69-year-old retired surgeon and the former director of Abu Yousef al-Najjar Hospital in Rafah—opened up the house to those seeking shelter as Israeli forces pushed down through the Gaza Strip, forcing hundreds of thousands of people from their homes. Rafah, its southernmost city, was thought to be safe.

Abdullah was well known in Gaza for his efforts to save lives during the Israeli response to the Second Intifada, once using his own thumb in a desperate bid to plug a bullet wound in the chest of a teenager.

Dozens of people were sheltering in the Shehada family home and its backyard when it was hit in an Israel airstrike on Dec. 14, 2023, completely destroying the three-story house.

Alkhatib’s brother Mohammed and cousin Yousef spent days digging bodies out from under the rubble. At least 31 bodies were recovered from the scene, including nine children—the youngest of whom, Alkhatib’s cousin Ella, was just 3 months old.

Five of Alkhatib’s aunts and uncles were among the dead, including Abdullah and Zainab.

“She came out headless,” he said.

The strike on the Shehada family home was examined by Amnesty International as part of an investigation published in early December in which the organization, for the first time, accused Israel of carrying out a genocide in Gaza. The investigation found “no evidence of a military objective” behind the strike.

Foreign Policy submitted an inquiry to the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) with coordinates, dates, and times of the three airstrikes that killed Alkhatib’s relatives, including the one on the house in Rafah. An IDF spokesperson said, “The IDF’s strikes on military targets are subject to relevant provisions of international law, including the taking of feasible precautions and after an assessment that the expected incidental damage to civilians and civilian property is not excessive in relation to the expected military advantage from the attack.”

Talking about the deaths of his relatives, Alkhatib started to slow down and lose his train of thought.

“What was I saying?” he said at one point during our lunch in Los Angeles, staring blankly into the distance for the first and only time. “I don’t like to do the fucking personal shit.”

He feels conflicted speaking about the strike publicly, not wanting to be seen as using his relatives’ deaths for clout. But there is also another reason. He cited a quote, often attributed to Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, that one death is a tragedy but a million is a statistic.

“When the fucking number is that high,” he said, referring to his loss of 31 family members, “it’s hard for people to comprehend and understand and connect with.”

Alkhatib estimates that on Oct. 7, 2023, he had maybe three followers on X (formerly Twitter).

“I lived a good, quiet life that I very much miss,” he said. He had just finished graduate school and was in the process of applying for a job at the U.S. State Department.

He had done a little bit of writing before, publishing with Israel’s left-wing newspaper Haaretz and the Washington Institute for Near East Policy think tank, but he had held back on becoming too public out of concern for the well-being of his family in Gaza.

In September, Alkhatib moved to Washington, D.C., from California to take up a new position as a senior resident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Center. He talks about policy with a passion that others might have talking about a love interest.

Policy is “what actually changes things on the ground,” he said during one of our first conversations.

Alkhatib sees a fleeting opportunity to galvanize global outrage to push for a Palestinian state. Last year, Ireland, Norway, Spain, and Slovenia recognized Palestinian statehood, joining more than 140 other countries that had already done so. But if the moment isn’t seized now, he fears it could be gone for good.

Efforts to broker a cease-fire deal between Israel and Hamas that would also secure the release of some 100 hostages held by the militant group have dragged out for months, despite intense diplomatic efforts.

The conflict, Alkhatib believes, is approaching an inflection point. If the war ends now, he still sees the potential to rebuild a better future Gaza. The territory’s most precious resource, he said, is its people and their resilience.

The alternative scenario of a drawn-out conflict and grinding insurgency risks expending that resource entirely.

“Then I’m irrelevant,” he said. “A population with no hope for life—no hope for a better future—is an immensely dangerous population.”

76 notes

·

View notes