#8mm Nambu cartridge

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Link

The article, written by Tom Laemlein for The Armory Life, discusses Japan's development and deployment of the Type 100 submachine gun during World War II. Initially, the Japanese military showed little interest in submachine guns in the 1930s, but began development late into the war. Influenced by European models like the Thompson submachine gun and the German MP 18, Japan's early experimentation led to the creation of the Type 100 by Nambu Arms, which was adopted by the military in 1942. Despite its practical design aimed at increased firepower in urban battles, the production was limited and delayed, resulting in only about 10,000 units by the end of the war and failing to significantly impact the Japanese military's capabilities. The Type 100 had notable variants including a folding stock model for paratroopers. However, with the lack of a powerful cartridge and production challenges, the Type 100 was ultimately considered inferior to other contemporary SMGs in terms of effectiveness and production ease. Despite this, it had a unique design and served a specialized role during its limited use in the war.

#Type 100 submachine gun#Imperial Japanese Army#World War II#Nambu Arms Manufacturing Company#Kijirō Nambu#8mm Nambu cartridge#magazine-fed#blowback operation#paratroopers#Japanese infantry#Axis forces#bayonet lug#folding stock#WWII firearms#Japan#battlefields#military history.

0 notes

Text

The Type 94 Nambu, the most ridiculed pistol in history.

The Type 94 was intended to supplement the Type 14 in Imperial Japanese military service. It was intended to be issued to pilots and vehicle drivers because of its smaller size. The Type 94 was also supposed to address some of the Type 14s short comings. Other then being a smaller frame pistol and less expensive to produce, the Type 94 was hammer fired making it more reliable in combat service. The Type 94 was will liked by those Imperial Japanese soldiers who carried them and was perfed over the Type 14, due to its smaller size and reliability.

The only real short coming of the Type 94 that I can see in combat, other then the exposed sear. Is the the Type 94 only held six rounds of 8mm Nambu. 8mm Nambu is not exactly the most powerful service cartridge on the planet, closer to .380 in comparison.

As for being able to fire the pistol by pressing the exposed sear, that is true. Unfortunately this has given the pistol a terrible reputation in the collecting community. It was never intended to be designed that way as a "last surprise," when surrendering to Allied Forces. Yes, it could be dangerous to the user if handled incorrectly, but that is where Imperial Japanese Military training would come into play.

Over all an interesting piece of World War 2 history.

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Japanese Nambu Part I ---- The Type A “Grandpa” and “Papa” Nambu

In 1893 Japan adopted its first domestically designed and produced sidearm, the Type 26 revolver. While it was a simple and reliable revolver, times and technology were changing, and soon semi automatics would become a popular option as a military sidearm. Sometime around the turn of the century an arms designer working for Tokyo Arsenal named Kijiro Nambu was ordered to design and develop a modern semi automatic pistol for Japan. The son of a Samurai, Kijiro Nambu was Japan’s most prolific firearms designer, a contemporary of gun designers such as Paul Mauser and John Browning. Unlike Mauser and Browning, however, some of Nambu’s designs were very problematic, overcomplicated, and just plain weird. While Nambu created many good designs, his bad designs give him a bad reputation among military and arms historians.

Perhaps Nambu’s most successful designs were his semi automatic pistols, which would become the standard sidearm of the Japanese military from the 1920′s up until the end of World War II.

Nambu completed his pistol design in 1902. What he created was a semi automatic pistol that outwardly looked similar to the German Luger, but internally was similar to the German Mauser C96 Broomhandle pistol. Utilizing a recoil operated locked breech mechanism, meaning the inertia generated from the recoil drove the breechblock backwards, while the locking mechanism slowed the momentum of the breechblock so it didn’t create excessive recoil or damage the mechanism. A spring would then drive the mechanism back into place. During the process, the empty cartridge casing would be ejected, and a new cartridge stripped from its 8 round magazine.

The Nambu pistol fired an 8x22mm cartridge, also designed by Nambu, which has similar ballistics and stopping power of the .380 ACP cartridge. The pistol featured a grip safety, meaning that the pistol would not fire unless the handle was gripped by the hand.

The magazine release was located on the left hand side of the pistol. The magazine did not freely drop from the pistol, but had to be extracted by hand. The pistol featured a rear tangent sight which can be adjusted from 100 to 500 meters. Call it wishful thinking, but I doubt many Japanese officers were making 500 meter shots with their Nambus.

The new pistol was called the Nambu Pistol Type A. Two variants were produced, the “Grandpa” Nambu which was the first production model, and the “Papa” Nambu which was an improved model. The Grandpa Nambu began production in 1906 by the Tokyo Arsenal and Tokyo Gas and Electric company. Only 2,400 were produced before production ceased and the modified Papa Nambu was introduced. One major complaint with the Grandpa Nambu was that the trigger guard was too small. Thus the trigger guard of the Papa Nambu was enlarged slightly. The Grandpa Nambu featured a wooden grip on the bottom of the magazine, while the Papa Nambu featured an aluminum grip. Finally the Grandpa Nambu featured a welded lanyard ring, while on the Papa Nambu the lanyard was a separate piece . 7,100 Papa Nambu pistols were produced until production of the Type A ceased entirely in 1923.

The Nambu Type A pistol was a fairly well designed pistol for the early 20th century. Perhaps it’s best trait is that it is a very well balanced and accurate pistol. However it did have some problems. First the 8mm Nambu cartridge was quite anemic compared to competitors such as the 9mm Luger, .45 ACP, 7.62x25mm Tokarev, and 7.63x25mm Mauser. However it must be noted that at the time there were many military pistols common in Europe which used small caliber, low pressure cartridges such as .32 ACP. Second, it had very weak firing pin springs which wore out quickly, causing malfunctions and failure to fire. Finally the Nambu had a reputation for being vulnerable to mud, moisture, dust, sand, and extreme temperatures. Considering the Japanese Imperial Army would operated in places such as the frigid Mongolian steppes, hot and humid jungles, or sandy pacific islands, this flaw could be quite problematic. However this reputation is unfair since this is an issue common to all semi automatic pistols, even today. Most of the reliability problems were not necessarily the blame of the pistol or Kijiro Nambu, but from inadequate cleaning and maintenance on the part of Japanese officers who carried them.

The Japanese Army chose not to adopt the pistol, not because of design flaws or poor performance, the pistol actually performed well in military testing trials. It’s biggest downside was it was very expensive. Until the end of World War II, Japanese officers were required to purchase their own sidearms. Most chose not to purchase the Type A because there were many foreign imports from Europe which were cheaper but just as good or better than the Nambu in terms of performance. In addition, pistols were not really important to the Japanese Army, with many officers prizing a their swords over their firearms. The only military contract for the pistol was a limited production run for the Japanese Navy and military contracts from Thailand. Among those produced for Thailand was a rare model that featured a detachable buttstock which doubled as a holster.

Regardless of it’s lack of popularity, the Type A Nambu saw some limited service with the Japanese Army during World War I.

401 notes

·

View notes

Text

British submachine gun trials, 1915 - 1939

It is often said of the British Army that before World War II, they completely disregarded submachine guns (or “machine carbines” as they were then known) purely on the basis that they were “gangster weapons”. This is only half-true - while the pre-WWII British Army was decidedly more conservative than most militaries of the time when it came to small arms, there were some steps taken to investigate submachine guns.

The first submachine gun to be tested by the British Army was the progenitor of the entire concept - the Italian Villar Perosa, demonstrated at Hythe on the 7th of October 1915. The weapon had been brought to England by an Italian representative, Mr. Bernachi, who submitted it to the Small Arms Committee. A further test took place at the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield on the 18th. The report from the SAC described the weapon as “very suitable for trench work”, but there was no interest from the General Headquarters in France.

The Villar Perosa submachine gun demonstrated for the SAC. This model was a one-of-a-kind piece chambered in .455 Webley.

During the closing stages of the war, in September 1918, a captured German Bergmann MP18 (serial no. 214) was tested by the SAC, who sent a report to the General Headquarters. The GHQ took a very dim view of the MP18, who seemed to be under the impression that the Germans were planning to use the weapon as a substitute for rifles. For the GHQ, the MP18′s failing was its pistol-calibre ammunition, which they felt was far too underpowered - their concern was that use of low-power bullets would encourage the Germans to issue body armor, which the MP18 would be incapable of penetrating. The GHQ’s response to the SAC essentially dismissed the MP18 as a novelty and insisted that British infantrymen continue to be issued full-power rifles and machine guns.

Despite now being considered a revolutionary weapon, the contemporary British view of the MP18 was that it was little more than a novelty.

After the war ended, various new submachine gun designs did begin to emerge, although not all were based on the MP18. Brigadier General John Taliaferro Thompson’s now-famous “Tommy gun” was one such weapon, which he had conceived during the war as a weapon to break the stalemate of trench warfare. Ultimately he failed to get it into production while the war was still raging, and it was only perfected by 1921. Thompson went to Britain that year to oversee the tests of his weapon by the Small Arms Committee. The tests were conducted at Enfield on the 30th of June and the SAC did not draw comparisons to the MP18, describing the Thompson as a weapon of “an entirely new type”. Regardless, the impressions were generally positive, and the gun functioned well, attracting considerable interest, although there was no serious consideration to issue such weapons to British troops at the time.

The M1921 Thompson. Designed strictly as a military and police weapon, it earned a negative reputation as a gangster’s best friend during the 1920s.

The M1923 Thompson was a failed attempt to market the Thompson in the role of a machine gun. It was tested by the British and French armies but rejected.

In 1928, the Thompson was tested again at Enfield. This model was a British-made version that was the result of a combined business venture between Birmingham Small Arms and Thompson’s Auto Ordnance Company. Their goal was to arouse European (although primarily British) military interest in the Thompson. The BSA-made Thompson had rifle-like ergonomics but was basically the same gun as the Thompson M1921, but offered in a variety of calibers, including the standard .45 ACP, 9mm Bayard, 7.63mm Mauser, and 9x19mm Parabellum. The model tested by the SAC at Enfield was fitted with a Cutts compensator, which would become standard on the M1928 Thompsons, although the SAC was of the opinion that the compensator made virtually no difference to the weapon’s performance. The BSA Thompson was not investigated any further.

The same year, the Revelli automatic rifle - a single-barreled version of the Villar Perosa developed in Italy shortly after the war - was tested, again at Enfield, by the designer himself. There was little interest from the SAC.

The British-made M1926 Thompson. By all accounts a perfectly good weapon that should have been a success, but was hindered by conservative attitudes.

The Revelli, often called the “OVP” after its place of manufacture, was designed in 1920 and was used by the Italians in North Africa during WWII.

The Vollmer was tested in 1932 and the Solothurn S1-100, designed by German engineers but manufactured in Switzerland and Austria to evade the conditions of the Versailles Treaty, was tested at the end of 1934. Both guns were compared to the MP18 but failed to impress. On the 29th of September 1936, the Finnish Suomi was tested. The gun was expensive, at £31, but was considered by the SAC to be the “best “gangster” weapon we have seen”. This was the first use of the term “gangster gun” by the British authorities in regards to submachine guns, no doubt in reference to the notoriety that the Thompson gun had picked up in the US during the prohibition era.

The Solothurn S1-100 was an immaculately-made but very expensive submachine gun. It was adopted by Austria as the MP34 in 1934.

The Finnish Suomi gun was one of the better submachine guns on the market before the war. It performed very well during the brief Winter War of 1939.

1937 saw two submachine guns tested by the SAC. The first was the American .45 Hyde, demonstrated on the 23rd of June. It was fitted with a double magazine consisting of two interconnected magazines fixed side-by-side. The SAC liked this novel feature but paid less attention to the gun itself. In December of that year, the SAC tested what they described as a Spanish Star machine carbine, chambered in .32 caliber. I am actually unsure what this weapon might have been, since there were few Spanish submachine guns at that time and those that did exist were all chambered in 9mm Largo, but I assume it was a rechambered Star Si35. Regardless, the SAC held a low opinion of it.

The Hyde, chambered in .45 ACP. Considered a rival to the Thompson, it lost out to that weapon in both British and American trials.

An experimental .22-calibre Hyde demonstrated at RSAF Enfield in the 1930s.

In 1938, several weapons were brought to the attention of the SAC. They were the Japanese Nambu submachine gun, the Danish Brøndby, and the Finnish Suomi.

The Nambu gun, known simply as the Type 1, was of interest because of its small build and light weight. It was considered a decent weapon for vehicle crews - what we would now call a personal defence weapon or PDW. The Nambu was rejected for two reasons: its 8mm chambering, since the Japanese 8mm cartridge was not readily available in Britain nor was it considered powerful enough for British use; and its long, 50-round curved magazine, which was ergonomically awkward and made the overall height of the weapon over 11 inches.

The Japanese Nambu submachine gun was one of the first submachine guns to feed through the pistol grip, although it was too bizarre for it’s own good.

The Brøndby submachine gun was sent as part of a series of gas-operated weapons designed by Fridtjof Brøndby, including a rifle and light machine gun. They were tested in March 1938. The submachine gun was chambered in 7.63mm Mauser and fed from a small 15-round magazine. This wouldn’t have been so much of a problem if the fire rate was not as high as it was: 818 rounds per minute. The SAC gave the Brøndby a positive write-up and arranged trials to compare it to other existing submachine guns, including the German S1-100 and MP28, the American Hyde, and the Finnish Suomi. However, interested lapsed and the trials ended up not taking place at all.

The Danish Brøndby was an early gas-operated submachine gun that failed to attract any buyers, despite showing promise.

In the August of 1938, the SAC received the first British-designed submachine gun, the 9x19mm Biwarip. It was an unusual little gun, largely unlike any the SAC had encountered before. It had no stock or sights and was extremely light and compact; the overall handling felt more like that of a machine pistol than a submachine gun. The SAC decided it was uncontrollable in automatic fire and took no further action with it.

At the end of the year the SAC tested an Estonian Suomi with a 50-round dual magazine, similar to the Hyde gun described earlier. The SAC liked the idea so much that they asked RSAF Enfield to consider copying the concept and applying it to Bren guns, which, as far as I know, was never actually done. The Suomi gun itself was once again shot down by the General Staff, who unequivocally reiterated that no such weapon would be adopted by the Army.

The Biwarip was the first British submachine gun. It wasn’t great, but it served as the basis for the Sten and later the Sterling.

In 1939 the SAC was replaced by the Board of Ordnance, which only investigated two submachine guns that year. They were the BSA-Kiraly and the Erma MP38. The Kiraly design was submitted to the SAC via Mark Dinely, who himself had designed an experimental .32 submachine gun. Dinely’s firm, Dinely & Dowding, imported blueprints of a new design from Hungarian engineer Pal de Kiraly. The Ordnance Board were interested and ordered a batch of prototypes. Production rights were given to Birmingham Small Arms, who produced a small quantity at the low cost of £5 per unit.

The prototypes were submitted to Ordnance Board in May. The guns had some novel features, like pivoted magazine housing that could fold under the barrel. Firing tests were positive and there were no major reliability or performance issues recorded. The Ordnance Board was not as impressed by the almost indescribably complex trigger mechanism, which used a flywheel, tape, and spring mechanism to moderate the rate of fire. Kiraly offered to simplify the mechanism to make it easier to manufacture, but the Ordnance Board never showed any further interest, which was perhaps a huge mistake - at such a low cost, thousands of these quality submachine guns could have been produced by BSA and issued to British troops before the war had started. Ultimately, though, it was not to be.

The BSA-Kiraly prototype. An excellent weapon that unfortunately didn’t get very far. The design evolved into the Hungarian Danuvia submachine gun.

The last submachine gun investigated by the Ordnance Board in 1938 was also in May. It was the Erma MP38, the new German submachine gun, recommended to the Ordnance Board by the Director of Artillery. He was alarmed by the extremely fast production of this weapon in Germany and asked the Ordnance Board to consider such a weapon, especially now that war was looming. Tests were conducted and the MP38 was found to be a quality weapon but no action was taken. Even if there was any major interest in the design, the mounting tension between Britain and Germany would have made adoption of the MP38 impossible. Interestingly, in 1940, the Royal Air Force ordered 10,000 British-made copies of the MP38, a request that was shelved in favor of the Lanchester.

War finally broke out on the 2nd of September 1939. When the British Expeditionary Force were sent to France later that year, they filed a request to the Ordnance Board asking for an immediate supply of submachine guns. Several guns were sent for trials in France, conducted by the BEF. Not all the weapons tested were actually submachine guns; some were rifles and light machine guns modified to fill a similar role.

The submachine guns tested were the American Thompson and Hyde guns, the German-designed Solothurn S1-100, and the Finnish Suomi. The American Johnson rifle, the Czech ZH-29, and the French RSC were converted into automatic rifles and also tested. Modified Lewis and Bren guns were also tested in the role of a hip-fired submachine gun.

The Solely gun, a modified Lewis that was briefly considered as a stand-in for a true submachine gun. It used Bren magazines.

Unsurprisingly, the Thompson was favored. The British Army hurriedly pressed Thompson guns into service, but it was too little, too late. By the time fighting broke out in May 1940, the majority of British soldiers found themselves without a submachine gun and the Germans had plenty. After the disastrous “Fall of France”, the British evacuated from Dunkirk and found themselves in a precarious position, faced with potential invasion. British small arms philosophy was made completely redundant by German tactics and the Army was forced to reconsider its approach to submachine guns completely.

117 notes

·

View notes

Photo

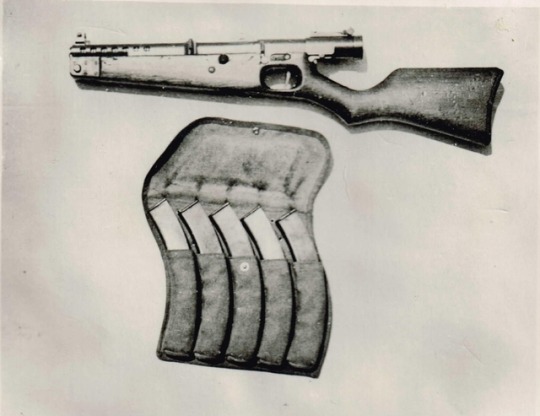

Japanese Type II Model B

Like many of the major powers at the beginning of the Second World War the Japanese had shown little interest in submachine guns. Purchasing a limited number of Bergmann MP28/IIs and MP34s for testing and limited issue during the late 1930s. Alongside these foreign designs some indigenous development also took place with Kijiro Nambu designing several interesting submachine guns.

There is relatively little information available about Nambu’s submachine guns with even designations muddled. Author William Easterly notes that the model featured above was described as the Type II Model B. Developed in 1934, the earlier Type I chambered the 8mm Nambu pistol cartridge and fed from a 50 round curved magazine. The pistol grip acted as a magazine housing, a feature predating both the Sa vz. 23 and the Uzi. Other than the weapon’s pistol grip it followed conventional designs from Bergmann and SIG using a tube receiver and a blowback action.

The Type II Model B, shown above, differs significantly from the earlier Nambu submachine gun. It has full wooden furniture with a cutout for a trigger guard, and a semi pistol grip stock. The magazine loads just ahead of the trigger guard and the Model B feeds from 30, rather than 50, round magazines. The design retains the tube receiver and used a telescoping recoil spring and a pneumatic buffer to slow the weapon’s rate of fire.

The Japanese Army were allegedly uninterested in the new weapon, however, it has been suggested that the Navy purchased a small number for testing. Samples were certainly produced, probably by Nambu’s company, Nambu-Ju Seizosho K.K. One of these samples was found at the Japanese headquarters in Singapore at the end of the war (see image #2).

A British technical report produced by the Chief Inspector of Small Arms in Bengal, India describes the standard of the captured Model B’s workmanship as being “above that normally found in Japanese small arms.” The report describes the Model B’s pneumatic rate of fire reducer as having “five holes of different sizes in the cap of the buffer housing.” The rate of fire could be varied by the rate at which the air was pushed out of the valve in the buffer. It is unknown on which gas setting the weapon was tested on but a rate of 820 rounds per minute was recorded.

The weapon had a safety on the left side of the receiver which locked the trigger.Overall it weighed 6.25lbs, was 26 inches in overall length and had a tangent sight, graduated out to an optimistic 600m. Some sources suggest that less than fifty Type II Model B’s were produced with several now residing in reference collections.

Sources:

C.I.S.A, India, Technical Report No. J-28 on 8mm Unknown Type Japanese Machine Carbine, via ForgottenWeapons, (source)

Many thanks to Peter Hokana for kindly allowing the use of his photograph

Nambu Machine Pistols, W. Easterly, (source)

If you enjoy the content please consider supporting Historical Firearms through Patreon!

#history#military history#firearms history#ww2#japanese submachine gun#nambu#prototype#firearms design#firearms development#gunblr#weapons#prototypes#firearms#guns#wwii#world war two#kijiro nambu

150 notes

·

View notes