#585BCE

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

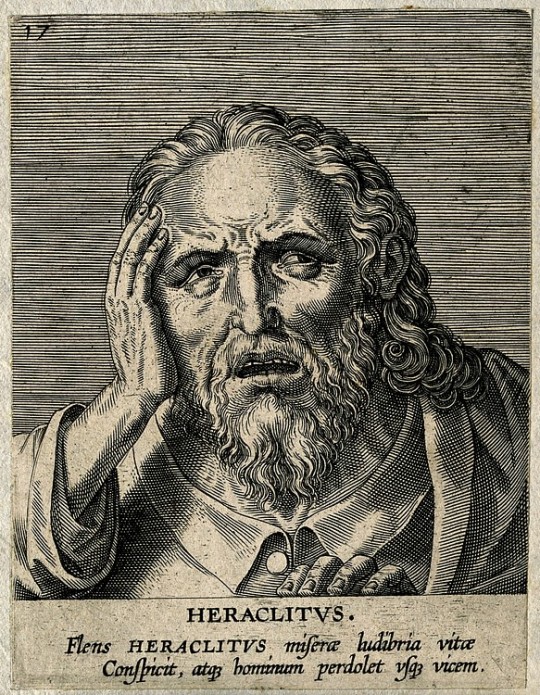

Heraclitus: Life Is Flux

Heraclitus of Ephesus (l. c. 500 BCE) famously claimed that “life is flux” and, although he seems to have thought this observation would be clear to all, people have continued to resist change from his time to the present day. Heraclitus was one of the early Pre-Socratic philosophers, so named because they pre-date Socrates, considered the Father of Western Philosophy. The early Pre-Socratics focused on identifying the First Cause of creation – that element or energy that set all of creation in motion and sustained it – and were known as “natural philosophers” because their interest was in natural causes for previously-held supernatural phenomena as explained by the will of the gods.

His Eastern contemporary, Siddhartha Gautama (the Buddha, l. c. 563 - c. 483 BCE), recognized the same essential aspect of life: that nothing was permanent and the observable world was in a constant state of change and understood that this was the cause of human suffering: people insisted on permanence in a world of impermanence. The Buddha encouraged people to accept the essential nature of life and detach themselves from the false idea that anything they held to could be permanent. Heraclitus had the same message but with a significant difference: one could attach one's self to anything, as long as one understood it was fleeting.

The difference between the two philosophers is that Heraclitus encouraged active engagement while Buddha suggested enlightened disinterest. Buddha taught a path of gradual detachment from the mutability of the world leading to the understanding and recognition that one could live one's life fully without craving for what one lacked, fearing what one might lose, or mourning what was past. Heraclitus encouraged people to embrace change as the fundamental essence of life and live in it, even celebrate it, with total awareness of what one had and would inevitably be lost.

Although their central focus differs, their goal is the same: to awaken those who cling to what they know through fear and ignorance and allow for their movement toward a higher, more vibrant understanding of life. Interestingly, though not surprisingly, this same focus would be developed in the 20th century CE by the iconic Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung (l. 1875-1961 CE) who emphasized the importance of the process of self-actualization – comparable to the state of awareness encouraged by Heraclitus and the Buddha – by which one could let go of childish fears and limitations to live a more mature and fulfilling life.

Heraclitus' Philosophy

Heraclitus seems to have written a number of important works but, of these, only fragments remain preserved by later writers. The early Pre-Socratic interest in identifying the First Cause began with Thales of Miletus (l. c. 585 BCE) and continued on through his student Anaximander (l. c. 610-546 BCE) and then Anaximenes (l. c. 546 BCE), all of whom inspired later philosophers such as Heraclitus.

Thales claimed the First Cause was water because water could assume various states – heated it became air (steam), frozen it became solid (ice), and so on. Anaximander rejected this and claimed the First Cause had to be a cosmic force (which he called the apeiron) far beyond any of the elements of earth, because its essence had to be a part of all of the elements of creation. Anaximenes suggested air as the fundamental element because, like Thales' water, it could assume different forms such as fire (when rarefied), water (through condensation), and maintained life.

All three of these claims recognized change as an essential aspect of the First Cause. Even so, Heraclitus rejected all three as insufficient because, it seems, they lacked an observable, transformative quality; water, the apeiron, and air could initiate transformation but not complete it. He claimed instead that the First Cause was fire – a transformative energy – because all of life, and the very nature of life, was change and transformation embodied and illustrated by the energy of fire. Fire transformed raw meat into cooked food, cool air into warm, wood into ash, darkness to light and so, he claimed, was clearly the First Cause.

Heraclitus is said to have born to an aristocratic family of Ephesus but, whether he actually was, is said to have maintained a superior attitude toward others throughout his life. His philosophy is said to have developed from this attitude as he believed that most people he encountered were beneath him and were, in fact, spiritually and intellectually asleep. It could well be, however, that Heraclitus was simply an astute observer of the human condition and recognized that most people were, in fact, asleep in their lives – as he says - surrendering their own judgments to popular opinion and betraying their dreams in the interests of others. Heraclitus seems to have phrased his philosophy in such a way as to wake people up and force them to confront their own spiritual laziness and emotional lethargy.

It is unclear, owing to his phrasing and the few fragments left of his writing, what his philosophy consisted of outside of the claim that life is constant change, but it seems he advocated for complete awareness of existence in the form of simply paying attention and remaining critical of other people's definitions or declarations of truth. He regularly criticized his fellow philosophers and earlier writers, doubted the opinions of professionals in any area, and believed he understood best how to navigate the path of his own life.

He is probably best known for his oft-misquoted assertion, "You can't step into the same river twice" which is usually directly translated as "In the same river we both step and do not step, we are and are not" (Baird, 20). What Heraclitus meant is that the world is in a constant state of change and, while one may step from the banks into the bed of a river one has walked in before, the waters flowing over one's feet will never be the same waters that flowed even a moment before. In the same way, moment to moment, life is in a constant state of change and, in his view, one can never even count on the certainty of being able to walk into the same room of one's house one moment as one might the next.

Continue reading...

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sometimes, you need a poison plant for your lapel.

As with a lot of poisonous flowers, most people don’t know how to recognize it out and about. Ladies and gentlemen, may I present helleborous niger, black hellebore, hellebore, Christmas rose, winter rose or nisewort. Known as one of the four classical poisons (hellebore, nightshade, hemlock, and aconite) this winter flowering shade perennial is a prime example of beauty disguising danger. Low growing, this plant produces dark green foliage with 5-petaled blossoms in shades of pale green, white, pink, red and maroon (other cultivated species include flowers of black, brown, spotted and combinations of white with red tips and the like). Blooming in winter or early spring, all parts of the plant are poisonous. With irritation of the skin from contact with the sap to symptoms of vomiting, dizziness, nervous system depression, and convulsions from ingestion, the history of this plant is varied.

In Greek mythology, the seer Melampus used hellebore to cure King Proetus’s daughters of madness. Pliny the Elder gave specific instructions on harvesting the black roots of this flower for medicine or malintent. It’s theorized that Alexander the Great died after being given a medicinal dose of hellebore, while the First Sacred War (595-585BCE) was believed to have been won after the Greek military alliance poisoned the water supply of Kirrha with hellebore.

A key ingredient in classic flying ointments, it’s associated with Mars and Saturn with correspondences to water. Used in spells of banishment, exorcisms, protection and invisibility, it was also used to change the nature or other plants. Grafted onto other plants, or used as a fertilizer for fruit trees to make them unpleasant or unhealthy.

Look for helleborous niger, or helleborous officiales if you’re buying seeds. White hellebore or false hellebore looks the same, but is not the classic witch’s flower.

Happy planting everyone

#hellebore#helleborous niger#witch#witchcraft#green witch#poison#poisonous#poison path#poison witch#witch tumblr#male witch#male witches#alexander the great#plinytheelder#pliny the elder#gay witch#poison flower#new york#botanical#herbalism#wicked plants#evil plant#ows#witches of ouroboros#original post#flying ointment#witch fashion#accessories#deadly accessory#lapelpin

443 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ninigi

Ninigi-no-Mikoto, or simply Ninigi, is the grandson of the supreme Shinto deity Amaterasu, the sun goddess. He is the son of Ama-no-Oshiho-mimi and, descending to earth as the first just ruler, he brought with him gifts from Amaterasu as symbols of his authority which remain part of the Japanese imperial regalia today. Ninigi became the great-grandfather of Japan's first emperor, the semi-legendary Emperor Jimmu, and so established a divine link between all subsequent emperors and the gods.

Ninigi Descends from the Heavens

In Japanese mythology, the sun goddess Amaterasu Omikami asked her son Ama-no-Oshiho-mimi to descend from the heavens to rule the world of the mortals. Twice refusing this honour after seeing the general chaos that prevailed in the world, Ama-no-Oshiho-mimi nominated his son Ninigi-no-Mikoto (full name: Ame-Nigishi-Kuninigishi-Amatsu-hiko-no-ninigi-no-mikoto) to go in his place. To this Amaterasu finally agreed, and she gave Ningi three gifts to help him on his way. These were the Yasakani, a fabulous jewel (or pearls or magatama beads), source of the ancient quarrel between Amaterasu and her brother Susanoo, the storm god; the Yata, the mirror which had been made by the gods and successfully used to tempt Amaterasu out of the cave which she hid in following some typical bad behaviour from Susanoo; and Kusanagi, the great sword Susanoo had plucked from a monster's tail. These would become the three emblems of Ninigi's power (sanshu no jingi), and they became the imperial regalia of his descendants, the emperors of Japan, starting with his great-grandson Emperor Jimmu (r. 660-585 BCE). Thus, all subsequent emperors were able to claim a direct descent from the gods and so legitimise their authority to rule Japan.

The celebrated 7th-century CE poet Kakinomoto Hitomaro composed this poem on Ninigi's descent to govern humanity:

At the beginning of heaven and earth

The eight hundred, the thousand myriads of gods

Assembled in high council

On the shining beach of the Heavenly River,

Consigned the Government of the Heavens

Unto the Goddess Hirume , the Heaven-

Illuminating One,

And the government for all time,

As long as heaven and earth endured,

Of the Rice-abounding Land of Reed Plains

Unto her divine offspring,

Who, parting the eightfold clouds of the sky,

Made his godly descent upon the earth.

Manyoshi (Keene, 104-105)

Amaterasu also gave Ninigi some specific instructions regarding the Yata mirror: "Consider this mirror as thou wast wont to consider my soul, and honour it as myself" (Hackin, 395). Eventually, the mirror would indeed become an object of worship or shintai and end up in the Ise Grand Shrine in the Mie Prefecture, dedicated to Amaterasu and still today Japan's most important Shinto shrine.

Ninigi, carrying his three precious goods, and accompanied by three gods (including Ame-no-uzume, the dawn goddess, and Sarutahiko-no-kami, the god of crossroads) and five chiefs, landed on earth at the top of Mt. Takachiho, in the south of Kyushu. From there, after first building himself a palace, he went to the temple of Kasasa in Satsuma province where the five chiefs set about laying down the principles of the Shinto religion, creating a priesthood and organising the building of temples. The chiefs would pacify the land and establish the clans which would dominate Japanese government for centuries to come such as the Fujiwara clan. In this capacity, the five became the ancestral deities of these clans, the ujigami.

Continue reading...

47 notes

·

View notes