#30 acre reparations

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Link

Tiny Town #11 Maria BaconFormer Slave30 Acres.......(Reparations)Freedmen's Village

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

For the first time since the end of apartheid in South Africa, the ruling African National Congress (ANC) party is poised to lose its governing majority. While corruption and poverty are often cited for the setback the ANC is expected to face in elections later this month, its electoral fate is also closely tied to its performance on land issues.

Despite the fact that the country has urbanized and its economy no longer revolves around land, delivering land to Black South Africans remains a yardstick against which ANC performance is measured. Land has deep symbolic meaning as an acute material loss before and during the apartheid era and as hope for a more inclusive and just future. As Nelson Mandela put it in 1995, “With freedom and democracy, came restoration of the right to land. And with it the opportunity to address the effects of centuries of dispossession and denial.”

When apartheid rule crumbled in 1994, a small white minority held most of the farmland in the country, while 13 million Blacks, most of whose ancestors had suffered forced removals from their land, were packed into rural settlements at the fringes of the economy that the apartheid regime cynically labeled “homelands.”

That marginalization fueled inequality and deep resentment. Blacks were far removed from the centers of political and economic power, and the lands they were removed to were overcrowded and of poor quality. The incoming ANC vowed to return people to the land that had belonged to them.

The ANC initially promised to reallocate 30 percent of the country’s agricultural land, amounting to about 60 million acres, to redress racially based land dispossession that occurred following the 1913 Natives Land Act. It aimed to fulfill its promise with a land restitution program and a separate land reform program. The land restitution program sought to restore land rights to people who were forcibly removed from their land under racially discriminatory apartheid-era laws and practices.

Victims of land dispossession had to file a restitution claim with the state by the end of 1998 to be eligible to have their land returned or to have access to an alternative remedy. The land reform program entailed the distribution of land to nonwhites as part of reconciliation and reparations that would go beyond specific restitution claims. The goal, essentially, was to transfer land held overwhelmingly by wealthy white landowners to Black farmers.

It is no coincidence that the party retains staunch support in places where it has successfully delivered on its promises. I recently spent time at the site of one of these successes in the country’s northeastern Mpumalanga region. One of the biggest projects of land restitution in the country’s history took place under the Greater Tenbosch claim in Mpumalanga’s Nkomazi municipality.

In the late 2000s, the government transferred over 150,000 acres of land to seven Black communities in Nkomazi, comprising about 20,000 beneficiaries. Much of that land was planted in sugar cane, which required attentive management, capital, and expertise.

The government purchased the land from TSB, now part of RCL Foods, and handed it over to the communities. Several of them, in turn, formed joint partnerships with TSB, leasing the land back out to the company while participating in management and training a new generation of community-based leaders.

It has become a model for partnerships between business and communities that has been replicated in other valuable areas of agricultural production in the country. “It’s so challenging,” one Black farm manager told me, “but it’s so exciting, to work in that place knowing that you are giving something back to the community that raised you.”

Today, Nkomazi remains a bastion of ANC support. The party’s vote share reached an apex of 95 percent in 2009 with the Greater Tenbosch claim settlement, and in the last national elections in 2019 it still towered over its opponents in the district with 83 percent of the vote. Everyone I talked to in the land restitution communities remains supportive of the ANC given its transformational role in the country and could not imagine turning over power to another party.

The ANC reclaimed the Giba community’s ancestral land from white farmers in Mpumalanga province in the early 2000s and turned what was then a productive farm growing bananas, lychees, and macadamia nuts over to the community. It returned to revitalize and invest in the farm in the early 2010s, and it now grows high-value crops while employing women and running a program to train young people in farming.

The Giba Communal Property Association secretary, reflecting on the success of the project, reported, “As land reform beneficiaries, we have been able to establish partnerships that have enabled us to make this land profitable.” As with Nkomazi, election returns dating back to the 2000s show that the local municipality where the Giba community is located strongly turns out for the ANC.

But the ANC has notched more land reform failures than wins, and these failures are hurting it. Broader progress in both the land restitution and land reform programs has hit a thicket of snags. While the government has transferred about 14 million hectares (34 million acres) to Black farmers since the end of apartheid—excluding private purchases, restoring rights through compensation, or land acquisition for non-farm use—this is only about half of the ANC’s initial promise of 60 million acres. The government has pushed back the deadline to finish land transfers several times, and its new goal is to complete the process by 2030. Even that seems impossible at the current pace.

The land restitution claim deadline of 1998 was far too little time for many of the dispossessed to organize and present solid legal claims for restitution. Applying restitution is messy and entails grappling with what are often poorly documented histories and addressing inevitable conflicts between claimants on the same land. The government tried to reopen the claims process in 2014 to the many people who had previously been left out. But the Constitutional Court blocked that move, arguing in part that the government had to clear the remaining nearly 7,000 unresolved claims first. These are especially complex claims, often involving whole communities, and most remain stuck today.

The failure to finish the land returns it had promised decades ago has made the ANC vulnerable to political competitors on both its left and its right. The radical left, gathered most effectively by the Economic Freedom Fighters party, has criticized the ANC as slow, overly bureaucratic, and too accommodating to markets and white business interests.

It is pushing for rapid land returns and wants to accomplish its goal by dropping compensation for expropriated landowners. Meanwhile, the Democratic Alliance, a centrist party that gathers its core support from South Africa’s white minority population, advocates for a land reform process that focuses on business development and food security. It has repeatedly charged the ANC with ineptitude and corruption on land issues.

The financial difficulties and implementation problems in both the land restitution and land reform programs are hard to miss. Purchasing farmland for restitution and land reform at market rates is extremely expensive, slowing the process down and putting a lid on land transfers. The government also initially viewed its job as done after it handed land over to beneficiaries. The lack of comprehensive and sustained support from the government led to a wave of discouraging farm failures.

For example, the country’s first successful post-apartheid land claim, by the Elandskloof community in the Western Cape, buckled without enough capital and state support and has only recently begun to regain some footing. The initially successful Zebediela citrus farm in Limpopo province succumbed to the same fate after years of mismanagement, litigation, and interference. Other projects have underdelivered and faced long delays, like the resettlement of the District Six area of Cape Town that the apartheid government bulldozed to the ground—expelling and relocating its residents to make way for a whites-only area—in the 1960s.

In addition to these larger projects, legions of smaller farmers who received government grants to purchase state-acquired farmland have failed due to poor planning and insufficient post-settlement support. And the government has repeatedly been accused of corruption and double-dealing, doling out land to allies and more well-off individuals rather than the most needy. These failures are particularly galling for the many hardworking South Africans who are struggling to make ends meet, and they fan the flames of opposition to the ANC.

While its handling of land issues is shaking the ANC’s monopoly grip on power, any successor government will face similar challenges and should heed the lessons of recent years: Until the country’s land issue is remedied, it will continue to shape South Africa’s politics and bedevil those who govern the country.

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

Excerpt from this story from Grist:

On Wednesday, Congress passed one of the most sweeping relief programs for minority farmers in the nation’s history, through a provision of President Biden’s pandemic stimulus bill. Although the landmark legislation, which would cancel $4 billion worth of debt, seemed to emerge out of nowhere, it actually is the result of more than 20 years of organizing by Black farmers.

The Emergency Relief for Farmers of Color Act will forgive 120 percent of the value of loans from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, or from private lenders and guaranteed by the USDA, to “Black, Indigenous, and Hispanic farmers and other agricultural producers of color,” according to a release from the bill’s sponsors, Senators Raphael Warnock of Georgia, Cory Booker of New Jersey, Ben Ray Luján of New Mexico, and Debbie Stabenow of Michigan.

Advocacy groups say the debt relief will begin to rectify decades of broken promises and discrimination from the USDA that caused Black farmers to lose roughly 90 percent of their land between 1910 and today.

Although the program will be administered as pandemic relief — and apply to all farmers of color — the intellectual forces behind the bill say its main objective is to address failures in two landmark civil rights settlements between the USDA and Black farmers.

In 2016, USDA Secretary Tom Vilsack said the controversial settlements, known as Pigford I and II, “helped close a painful chapter in our collective history.” But instead, the Pigford settlements, which were designed to address a century of discrimination at the USDA, drew the ire of both conservatives and racial-justice advocates. The new debt-forgiveness legislation is controversial, too, with Republicans accusing Democrats of trying to sneak a reparations policy into an emergency bill instead of going through the proper legislative process.

The bill allocates $4 billion for the program because the Congressional Budget Office estimates that’s how much it will cost to pay off USDA loans to minority farmers, plus 20 percent. According to The Acres of Ancestry Initiative/Black Agrarian Fund, there are currently “over 17,000 Black legacy farmers [who] are delinquent on their loans to USDA ranging from 5 to 30 years.”

#black farmers#farming#COVID relief bill#Emergency Relief for Farmers of Color Act#American Rescue Plan

562 notes

·

View notes

Link

This is an article worthy of the entire read! Below is just a segment focused upon the Panther’s goals, and their political prisoner status, unrecognized by America. - Phroyd

In October 1966, Newton crystallized the goals of the party into a 10-point program. It was a cross between a call for an end to police brutality not dissimilar to today’s Black Lives Matter, criminal justice reform that would sit comfortably with the American Civil Liberties Union, and a demand for full employment, decent housing and good education that might have come from the lips of Bernie Sanders.

On top of such relatively mainstream demands, it threw in a strong dash of black militancy quite in contrast to King’s approach or to the established progressive politics of today. “We want an end to the robbery by the capitalist of our Black Community,” read point number three, going on to demand reparations for slavery equivalent to 40 acres and two mules – a nod to the as yet unfulfilled promise made by Gen William Sherman to freed slaves at the end of the civil war.

Then there was the emphasis on militarism and armed struggle. Even the structure of the organization was a provocation, setting the party up as a state within a state.

As Mumia Abu-Jamal, a former Black Panther who has been incarcerated for 37 years for the murder of a Philadelphia police officer, puts it: “The Black Panther party performed in the role of a shadow state – with its Ministries, its uniformed personnel, and its soldiers in sharp opposition to the US government.”

One of the party’s earliest activities was “cop watch”, in which members monitored police activities on the streets of Oakland at a time when police assaults on black people were rampant. It’s hard to imagine this happening today, but where officers were seen to stop and search African American youths, Black Panthers would approach them and stand there as observers, pointedly brandishing handguns at their hips.

Newton had studied California’s gun laws and knew that carrying loaded weapons openly in public was legal in the late 1960s. State legislators responded in 1967 by banning “open carry”, and to mark the occasion more than 20 Panthers entered the state capitol during the debate, waving guns.

The threat of armed insurrection by black revolutionaries inspired a powerful retaliation from the US government. The then director of the FBI, J Edgar Hoover, vowed to crush the Black Panther party, which he called “the greatest threat to internal security of the country”.

The surveillance program Cointelpro placed its spotlight on the Panthers, and vast FBI resources were mobilized against them. Before long, the party was riddled with informants and agent provocateurs, spreading disinformation and sewing dissent within the ranks.

____________________________________________

“My engagement in the struggle was self-sacrifice because of my love of my people and humanity. Because of that I was targeted by the government and that indicates that my incarceration is of a political nature.”

Muntaqim’s conflict – his burning desire for freedom rubbing against his determination not to renounce his politics which he sees as noble – is shared by most of the 19 remaining black radicals behind bars.

Of the 19, all but three were convicted of murdering police or other uniformed officers. Many profess their innocence, and most argue they have been selectively subjected to the full wrath of the American state.

How does their treatment compare with that of other convicted murderers who killed officers in the course of committing common crimes such as robberies? Firm comparisons are impossible given the devolved nature of America’s criminal justice system. As the Sentencing Project points out, “the 50 states vary on sentencing. As there are relatively few political cases, it’s hard to form any concrete conclusions.”

International comparisons, however, are instructive. Compared with the penal treatment of armed revolutionaries who were carrying out violent acts in Europe in the 1970s, the US appears far less open to concepts of rehabilitation.

Read All

Phroyd

32 notes

·

View notes

Link

Were U.S. slaves in any way responsible for their own misery? Were there any silver linings to forced bondage? These questions surface from time to time in the American cultural conversation, rekindling a longstanding debate over whether the nation’s “peculiar institution” may have been something less than a horrific crime against humanity.

When rapper and clothing designer Kanye West commented on TMZ.com that slavery was a “choice,” and later attempted to clarify by tweeting that African Americans remained subservient for centuries because they were “mentally enslaved,” he set off a social-media firestorm of anger and incredulity. And after a charter-school teacher in San Antonio, Texas asked her 8th-grade American history students to provide a “balanced view” of slavery by listing both its pros and cons, a wide public outcry ensued. The homework assignment was drawn from a nationally distributed textbook.

Such controversies underscore a profound lack of understanding of slavery, the institution that, more than any other in the formation of the American republic, undergirded its very economic, social and political fabric. They overlook that slavery, which affected millions of blacks in America, was enforced by a system of sustained brutality, including acts—and constant threats—of torture, rape and murder. They ignore countless historic examples of resistance, rebellion and escape. And they disregard the long-tail legacy of slavery, where oppressive laws, overincarceration and violent acts of terrorism were all designed to keep people of color “in their place.”

The history is clear on this point: In no way did the enslaved, brought to this country in chains, choose this lot. But several damaging myths persist:

In 1619, the Dutch introduced the first captured Africans to America, planting the seeds of a slavery system that evolved into a nightmare of abuse and cruelty that would ultimately divide the nation.

Couldn’t They Have Just Resisted?

The fact is, they did. Starting with the slave-ship journeys across the Atlantic, and once in the New World, enslaved Africans found countless ways to resist. Slavery scholars have documented many of the mutinies and rebellions—if not the countless escapes and suicides, starting with African captives who jumped into the sea rather than face loss of liberty—that made the buying and selling of humans such a risky, if lucrative, enterprise. Beyond famed slave revolts such as that of Nat Turner were less well-known ones such as that of Denmark Vesey. The literate freedman corralled thousands of enslaved people in and around Charleston, South Carolina into plans for an ambitious insurrection that would kill all whites, burn the city and free those in bondage. After an informant tipped off authorities, the plot was squelched at the last minute; scores were convicted, and more than 30 organizers executed.

The idea of “chosen” bondage also ignores those thousands of slaves who opted for a terrifyingly risky escape north via the sprawling, sophisticated network called the Underground Railroad. Those unlucky enough to be caught and returned knew what awaited them: Most runaways became horrific cautionary tales for their fellow slaves, with dramatic public shows of torture, dismemberment, burning and murder. Even when they didn’t run, wrote historian Howard Zinn, “they engaged in sabotage, slowdowns and subtle forms of resistance which asserted, if only to themselves and their brothers and sisters, their dignity as human beings.” That dignity, resilience and courage should never be belittled or misinterpreted as an exercise of free will.

Weren’t Some Slaves Happy to Be Taken Care Of?

Such misconceptions about slavery don’t come out of the blue. American culture has long been deeply threaded with images of black inferiority and even nostalgia for the social control that slavery provided. On the eve of the Civil War, white supremacists such as Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens stressed that slavery would be the cornerstone of their new government, which would be based “upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.” It was an attitude that would be continually reinforced—in textbooks that have glossed over the nation’s systemic violence and racism and in countless damaging cultural expressions of blacks in entertainment, advertising and more.

In the period immediately before and just following the Civil War, benign images in paintings and illustrations presented the old plantation as a kind of orderly agrarian paradise where happy, childlike slaves were cared for by their beneficent masters. Pop-culture stereotypes such as the mammy, the coon, the Sambo and the Tom emerged and persisted well into the 20th century, permeating everything from advertising—think Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben—to movies to home décor items like pitchers, salt-and-pepper shakers and lawn ornaments. They presented blacks as cheerful, subservient “darkies” with bug eyes and big lips and, often, with a watermelon never too far off. Popular paternalistic depictions such as that of “Mammy” in Gone with the Windshowed slaves as faithfully devoted to their masters and helplessly dependent. The consistent message: Blacks were better off under white people’s oversight.

The Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras saw the emergence of an even more damaging stereotype: blacks as savage immoral brutes. As seen in the work of authors such as Thomas Dixon and films such as D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, these fearmongering images of free black men presented them as predatory rapists who, once unshackled, threatened the purity and virtue of white women and needed nothing more than to be contained. Cue the Klan and lynch mobs.

Once Slavery Ended, Why Couldn’t They Just Pull Themselves Up?

Although the Thirteenth amendment technically abolished slavery, it provided an exception that allowed for the continuation of the practice of forced labor as punishment for a crime. In the decades after the Civil War, black incarceration rates grew 10 times faster than that of the general population as a result of programs such as convict leasing, which sought to replace slave labor with equally cheap and disposable convict labor. Although convict leasing was abolished, it helped to lay the foundations for wave after wave of laws and public policy that encouraged the jailing of African-Americans at astronomical rates. As Michelle Alexander writes in her book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Name of Colorblindness, “The criminal-justice system was strategically employed to force African-Americans back into a system of extreme repression and control, a tactic that would continue to prove successful for generations to come.”

The legacy of slavery and racial inequality can still be seen in countless other ways in American society, from well-documented acts of unfounded police brutality to voting restrictions to ongoing inequalities in employment and education. It’s no wonder that the call for reparations for slavery, racial subordination and racial terrorism continues to inspire debate. Beyond the original promise made by General William Tecumseh Sherman just after the Civil War to provide newly freed blacks with “40 acres and a mule”—a promise quickly recanted—nothing has been done to address the massive injustice perpetrated in the name of the “peculiar institution.” In 2016, a study by a United Nations-affiliated group reporting to the U.N.’s high commissioner on human rights made nonbinding recommendations that the history and continuing fallout of slavery justifies a U.S. commitment to reparations.

“Despite substantial changes since the end of the enforcement of Jim Crow and the fight for civil rights,” the committee said in a statement, “ideology ensuring the domination of one group over another continues to negatively impact the civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights of African Americans today.”

Slavery was not a choice, but opting to ignore its legacy is. It is a choice that will continue to inflame passions as long as we attempt reconciliation without confronting and redressing the awful truth.

1 note

·

View note

Text

7/30/2022

10:20 PM

this week has been a breath of fresh air (even though 30,000 acres of the valley are on fire and the air is far from fresh). i thought about my plans to document my process and i realized i am absolutely not about to post full journal entries on here because some privacy is important. i think it would be helpful to include some important ideas/thoughts from my writing here to sum up what i’m working through when i look back on these.

“i just want to be neutrally good. i don’t want to try to measure up to a “good enough”. i just want to be good. i want what is meant for me in all areas of life. my anxiety tells me that i have to identify everything that falls under that category, which makes me constantly question what is right for present and future me.”

“it’s not that i don’t want to learn and grow anymore, but i find myself wondering how many more mistakes will i have have to make before i can be ready for the things i want.”

“i have to respect myself, flaws and all, in order to to be respected and accept respect from others. i have to release what i have no power over. i need to understand myself to be understood.”

“to be detached doesn’t necessarily translate to being cold and closed off. healthy detachment means preserving a sense of self-worth, approaching life as my best and most authentic self, and more accurately attracting better experiences.”

“my angry feelings are valid, but they are just tools. they are not me and i do not embody them. my anger shows me what i need to change, about myself and my surroundings. emotions are guides, meant to be listened to. to listen is to pause and think.”

“i am rewiring my agreements. i am recalibrating my approach to fear. i am disconnecting from an unforgiving inner voice. i am not taking it personally.”

this week i got my shit together by cleaning my depression room, doing my laundry, journaling whenever i felt overwhelmed, spending time outside and with my family, making art, and drinking a lot of water.

i read “the four agreements” by don miguel ruiz, something my mom prescribed me. i tried reading it a few times in high school but i don’t think i was ready for it and gave up easily. i’m glad i waited until now because so much of the book felt like it was designed to pull me out of my miserable mindset. lots of ideas on reparenting yourself, empathy, and how we as individual humans actively choose to live in a hell or a heaven. i don’t want to spend my life in hell AND know that i chose it. haha.

i watched brother bear with my grandparents this week. it was the first movie i ever saw in theaters and i swear it’s burned into my brain, which isn’t a bad thing because it’s one of those movies that makes you feel new after watching it.

i have a lot of media on my mind because i’m back at home without a lot of options for curing boredom. i’ve been listening to a lot of music which i do anyway. i think it would be fun to add a weekly playlist to these, so i’m gonna do it.

1. ALL THESE CHANGES - Nick Hakim (sometimes i forget this one is about climate change)

2. Les Fleurs - Minnie Riperton (wish i was a little flower)

3. The Girl Wants to Be with the Girls - Talking Heads (girls are getting into abstract analysis)

4. As - Stevie Wonder (this is a wedding song)

5. Gold Snafu - Sticky Fingers (me when i’m chill)

6. Sun in My Mouth - Björk (weirdo lullaby)

7. Change - Djo (dissociative anthem)

8. Habitual Love - Okay Kaya (cry and scream)

9. touch tank - quinnie (stop crying and screaming)

10. Room Temperature - Faye Webster (gentle country girl despair)

p.s. <3

1 note

·

View note

Text

There’s no freedom without reparations

Keeping the promise of “40 acres and a mule” might have transformed life for Black Americans. A movement to secure payments for descendants of enslaved people rages on.

By Fabiola Cineas Updated Jun 15, 2022, 6:34am EDT

Illustration by KaCeyKal! for Vox

Born into slavery, Henrietta Wood was legally freed in 1848 in Ohio when she was about 30. She only basked in that freedom for five years.

In 1853, a white sheriff empowered by the fugitive slave law abducted Wood and sold her back into bondage, taking her on a journey from Kentucky to Mississippi and finally to Texas, where she’d toil on a plantation through the Civil War. Though President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, Wood did not regain her freedom until 1866, months after Union soldiers traveled to Texas on June 19, 1865 — Juneteenth — to enforce emancipation.

READ THE REST https://www.vox.com/the-highlight/23133146/reparations-freedom-cash-payment

0 notes

Text

Interview Transcript

Laura: [00:00:00]

[00:00:00] [00:00:00] So the first question we have is what made you start Taking Ownership PDX?

[00:00:08] Randal: [00:00:08] Um, well, um, I had a lot of people asking me how they could be stronger allies or accomplices for the, for marginalized communities and particularly the Black community. Because I, um, I have built quite a platform through hip hop.

[00:00:24] I'm a hip hop artist, uh, playing a six piece funk hip hop band called Speaker Minds. And I've, um, I do solo music with a DJ and I've been doing that for my entire adult life. So, and my music often talks about social justice and injustices, citizen, community outreach, and uplifting, things like that. So, and I've done a lot of philanthropy work in my, in my day, a lot of culturally specific, um, jobs where I've been like a mentor for Black and Brown youth on probation.

[00:00:53] Uh, I worked as a student advocate, um, for low income [00:01:00] young adults work heavy, you know, just a little, a lot of those communities. So, um, people, you know, got to know me as that. And so they reached out and, um, I also go to PSU right now. So I'm finishing my bachelor's in Black Studies and Social Science. And, um, so I've learned a lot about, you know, a lot of the oppressive, exclusionary ways of, of Oregon and the, you know, the nation.

[00:01:26] Um, and so I thought it would be a good idea. You know, when people ask me how they can help, I said, look, you gotta share your resources. Especially if you come from privilege, um, and you have benefited from exclusionary practices, uh, you know, so share your, share your wealth and let's, um, and then the idea that to repair homes came from the fact that, you know, I grew up in Portland, I'm a native, I grew up in Northeast Portland, so I watched the neighborhoods change.

[00:01:53] Um, and now that I have an idea of why that's happened, I realized, you know, a way that we could really help is [00:02:00] by, um, getting some of these repairs done. For the homeowners that still have survived gentrification, um, and, uh, that will keep the city off their back. Um, and, um, because a lot of the ways displacement happens is, uh, white people move into these neighborhoods and then they start complaining about Black people's houses, not looking, uh, adequate enough for their standards.

[00:02:25] And then, uh, the city comes out and puts liens on their homes and stuff. So this is a good way to combat gentrification in that way.

[00:02:34] Laura: [00:02:34] Amazing. Um, uh, we noticed that Taking Ownership PDX has a lot of support from other organizations and you also have a lot of volunteers and donors. Um, was that surprising to you?

[00:02:49] Like how did that happen so quickly?

[00:02:52] Randal: [00:02:52] Uh, so surprising. Yeah, I had no idea it was going to take off like it did. Um, I, I, you know, I, I thought it was gonna. [00:03:00] Just be like maybe a couple of homes, you know? Well, when I started there, I was very naive. Cause I don't, I'm not from the housing world. I, you know, I was a renter at the time.

[00:03:08] Um, You know, I don't, I didn't know the capacity. I thought we would just get a bunch of volunteers together and find some materials and start swinging hammers at homes and trying to, um, try to make them look better. But, uh, there's a lot more to it than that. And a lot of people were like, "well, you know, I don't really want to like come out and help, especially with the pandemic. Um, but here's some money to put towards it," and it just took off, you know, uh, after the first house. We were able to do quite a bit of repairs and then another house came in and then just, you know, words got out and then the news started getting a hold of it. So I did a bunch of news interviews and then that was when it really took off.

[00:03:48] Um, but yeah, because I, you know, I, I was not expecting this kind of response at all. Uh, I think people liked that I started at guerrilla style because I wasn't like waiting to get through all the red [00:04:00] tape, you know, I've been on enough committees and been in enough groups that I know. That red tape can take years to get through.

[00:04:06] So I was like, you know, send me your money and I'll, I'll put it towards the house and, you know, I'll deal with Uncle Sam later. Um, but yeah, I, would've never imagined, um, how big this got and how fast and it's still going strong.

[00:04:22] La'don: [00:04:22] Well, um, I have a question about that. So if someone wanted to be a part of that and volunteer, how would they go about that?

[00:04:29] Randal: [00:04:29] So right now, we're not really encouraging volunteers unless you're licensed, bonded and insured. We got over 400 volunteers signed up and we don't have enough work for that, especially in the winter. Um, You know, we, we, if you want it to, you could go to our website and there's a volunteer section, uh, taking ownership, pdx.org.

[00:04:48] Uh, but we're not encouraging that unless you are skilled in a trade and licensed, bonded, and insured. Um, so we can actually like do, um, [00:05:00] quality and insured work on these homes.

[00:05:02] La'don: [00:05:02] Thanks.

[00:05:04] Laura: [00:05:04] Okay. So the next set of questions is more specific to your thoughts on gentrification. So, um, who has a stake in preventing gentrification? Who can do that?

[00:05:19] Randal: [00:05:19] Um, the state, the city, the nation, the, the feds, uh, anybody that can make policies, you know, um, to, to stop this thing. Make policies that provide reparations. And I mean, I strongly believe reparations are needed for, uh, particularly the black community, but other communities as well, you know, natives need better reparations too.

[00:05:40] Um, but you know, the way, if you have any idea of how horrible this country has been. To, to, uh, nonwhite people, uh, particularly black people and the natives. Um, you would understand that the, that there is some sort of equity in the form of [00:06:00] monetary, um, gifts or whatever, that needed to be given. I mean, think about Oregon.

[00:06:06] They were, when they found Oregon, they were just buying up. Like they're just giving 300 to 600 acres of land to, to white men, just, you know, and black people couldn't even live here. So, um, with that understanding, I mean, they think that they have to like give you the, it has to, it has to be through equitable practices.

[00:06:25] They have to like, um, put in policies for developers that they have to give the developers the same rules that residential people have. So developers can come into neighborhoods and buy up houses and tear them down and build up some, you know, some, uh, garbage 30 unit building without asking the community what they want.

[00:06:48] Um, well, let's say if you're, if you're a homeowner, a residential homeowner and you want to just build a garage or something, you gotta ask all your neighbors what they think, what color, you know? So it's [00:07:00] not fair that these developers just because they have multi-millions and they, you know, can house more people, um, can come in here with their own set of rules and it actually impacts the whole, the rest of the neighborhood because utilities go up, property taxes go up.

[00:07:16] Um, and you know, you bring a whole different demographic into these neighborhoods. Uh, that's another thing is, you know, um, where I live, I just bought a house in Albina. It's mostly white people around here. This is a historically black neighborhood. Um, they'd lost all that culture. I think there has to be some policy in place that, that keeps the culture, uh, in the neighborhoods to, um, give the neighborhood of the voice.

[00:07:42] Yeah. But they definitely have to, um, do something reparation-like, and maybe that's providing property or, you know, monetary gifts or something.

[00:07:55] Annie: [00:07:55] So I do have a question about that. Um, do you think that legislative change is going to [00:08:00] be the most effective here in dealing with gentrification, or is it going to be more on like an individual level that we're going to see the most change?

[00:08:07] Randal: [00:08:07] I mean, I think most change starts from the bottom and like it does, you know, I don't know anything, any kind of change like that um, on a legislative level, I feel like always has to start with some individuals getting together and, you know, making some noise and then they're like, "Oh, okay, fine. It just looks like they're not going to shut up about it."

[00:08:31] So now we're going to start, you know, when you even think about like marijuana passing, you know, uh, you know, any, anything we've really got to make some noise unless it's benefiting the corporations. If it started, if it benefits everyday people on an individual level, we have to make noise and then they'll consider passing some stuff.

[00:08:55] Laura: [00:08:55] Um, the next question is, do you think enough [00:09:00] people know or even care about the gentrification that has been happening?

[00:09:07]Randal: [00:09:07] , I don't think enough people really understand the capacity of what gentrification is. You know what it's done, how severe it's been. Um, I think people, yeah, I think people just think like, cause you, when you grew up in capitalism, you just think that's just the way it is. Like, they want to take your house, they'll take your house.

[00:09:29] You know, they want to do that. You just got to work harder. You just got to pull yourself up by your bootstrap to keep your house. They don't understand the policies and just like the nuanced ways in which they operate to, to, you know, take their homes. And, um, if you're one of the people benefiting from gentrification, You're usually one of the people that has the most resources and the most power to enact the change.

[00:09:56] That's why we always tell white people, y'all got to talk to each other. Y'all got to be [00:10:00] the ones out here, um, really, you know, making that change, um, because this is your, this is a system that was built by y'all, so y'all gotta dismantle it, you know, it can't just be us. So. I think it's hard for white people who benefit from it because they're content and they think, all right, I just bought this house, but you know, I'll put a Black Lives Matter sign in my yard and they think that's enough, you know?

[00:10:26] So they don't, you know, I, so just for instance, some serious, uh, accomplice ally work that just happened is I bought this house from a white lady. She sold it to me for what was, what was left on the mortgage, because she didn't want to make any money off it. And she wanted to put a black family back in the Albina neighborhood.

[00:10:49] So like, that's that radical philanthropy work that I think needs to happen that I don't think a lot of people are going to do. This woman's like on some other shit. [00:11:00] So, which I'm thankful for. Um, and, but yeah, I don't think that there's not going to be a lot of people that are going to do that. And she didn't put herself out cause she's wealthy and she's a, she's a successful business owner and owns multiple properties.

[00:11:14] I don't know if I can say enough people care to make the actual radical, um, decisions and actions that it will take to, to reverse gentrification. And gentrification is already done. Like there's no, there's no like black community in Portland anymore. It's gone, you know, I mean, I guess you could say it's in the numbers, but that's not really, you know, that's not really it, so it has to be reversed at this point.

[00:11:53] Laura: [00:11:53] How important do you think aging in places, you know, like being able to, um, [00:12:00] to stay in someone's home regardless of their age or their income? How much of an importance do you see in that?

[00:12:09] Randal: [00:12:09] I think, you know, it's like, uh, I think it's like one of the most important things as far as what humans need is, you know, shelter and, uh, as somebody who, um, is a brand new homeowner - I just bought this house two months ago - um, I was a renter all before that. With two, I became a father at night, 10 years old of two, and I've lived in maybe 12 places since they were born. We're renting apartments, living in garages, whatever I could find and, you know, um, and it's miserable and it's, uh, not knowing, you know, having to move.

[00:12:46] First of all, moving sucks. You know, we all know that. Um, but yeah, you know, bouncing my kids around from place to place and, um, you know, just to be able to stay and [00:13:00] to be able to pay into your property and then actually get towards paying off your property is huge. You know, like an actual mortgage is amazing.

[00:13:09] Uh, when you're renting, you're just giving your money away all the time. Um, But yeah. I mean, especially when you get older and, uh, it looked the cost of living going up, you know, it's harder to find other places to live. Um, so yeah, it's important. And then familiarity in communities is I think so important to, to, uh, people. And so, yeah, I think it's just in so many, so many aspects of it is important.

[00:13:38] Laura: [00:13:38] And I have one last question. Uh, do you have any advice on how to spread awareness on, uh, the ramifications of gentrification for people who don't have much of a platform or just, you know, every day trying to spread awareness?

[00:13:57] Randal: [00:13:57] Um, I also want to say the importance of [00:14:00] aging in place is also to be able to pass down your property to the next generation. So I think that's actually really huge. Ways to raise awareness. I mean, do your research, one, you know, uh, I think that's important.

[00:14:14] There's a great class - I'm actually in my capstone class right now. Um, it's racial equity in Oregon. I'm learning a lot about gentrification and just the origin of all that in that class. I, so I recommend y'all take it. I don't know, take that class if you want, but it's a good one. Well, yeah. Do your, do your, uh, research on, on, um, Portland or even, you know, other cities too, but I mean, Portland has its own unique or Oregon has its own unique story.

[00:14:40] And I mean, my way of raising awareness is social media. That's how this whole thing started. If I didn't have a platform on social media, there's no way I would've got the word out so fast, um, And provide resources. Um, yeah, I think that's, that's the way to go these days [00:15:00] is social media. Yeah. And action. Don't just talk about it. Do about it.

[00:15:11]Laura: [00:15:11] Well, thank you so much, Randall.

0 notes

Link

Reparations – Has the Time Finally Come?

During a lull one afternoon when I was a high school student selling Black Panther Party newspapers on the streets of downtown Washington, D.C., in 1971, I sat down on the curb and opened the tabloid to the 10-point program, “What We Want; What We Believe.” The graphic assertion of “Point Number 3” particularly grabbed me:

“We believe that this racist government has robbed us and now we are demanding the overdue debt of forty acres and two mules … promised 100 years ago as restitution for slave labor and mass murder of Black people. We will accept the payment in currency which will be distributed to our many communities. The Germans are now aiding the Jews in Israel for the genocide of the Jewish people. The Germans murdered six million Jews. The American racist has taken part in the slaughter of over fifty million Black people. Therefore, we feel this is a modest demand that we make.”

The absence of justice continually flustered me because, even at that young age, I knew that Black people had been kidnapped and brought to this country to labor for free as slaves; stripped of our language, religion, and culture; raped and tortured; and then subjected to a Jim Crow-era of lynchings, police brutality, inferior education, substandard housing, and mediocre health care. I did not know then about the massacres in Rosewood, Florida, or Tulsa, Oklahoma; the merciless experimentations on defenseless Black women devoid of anesthesia that led to modern gynecology; or about the enormous profits from slavery made by corporations, insurance companies, the banking and investment industries, and academic institutions. But on a psychic level, I could feel in my bones the enslavement era’s inhumane cruelty to Black children — its destruction of kindred ties and its economic exploitation and cultural deprivation. There was an incessant gnawing in my soul for amends and redress. I was passionate about injustice, felt the idea of reparations to be reasonable and fair, and vowed to talk about the concept whenever and wherever I could. My analysis, however, had not crystallized beyond a check. But just to mouth the word “reparations” was a starting point to its validity. Thus talk about it I did, despite my views being often rejected, ridiculed, or otherwise summarily dismissed. Standing on the street corner that afternoon nearly five decades ago, little did I realize that I would one day be in the company of leading academics, economists, historians, attorneys, psychiatrists, politicians, and more — domestically and internationally — promoting the right to, and the need for, reparations.

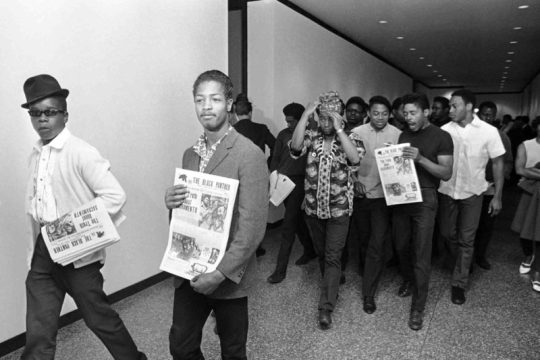

Several members of the Black Panther party carry copies of the Black Panther newspaper

Credit: Associated Press

The Fight for Reparations Has a Long History

But that day would be far into the future. Despite my advocacy and that of many others during my high school, college, and law school years and beyond, the issue of reparations for descendants of Africans enslaved in the United States was not fashionable, but fringe, and definitely not part of the mainstream popular discourse. Indeed, one would be branded as a militant or a revolutionary (both of which I was), or just plain crazy (which I was not), or in today’s dubious governmental surveillance parlance, a “Black Identity Extremist.” Indeed, it is almost surreal being amidst all the buzz surrounding reparations today, from universities to talk show pundits and, interestingly, to 2020 Democratic candidates vying for the presidency. Despite or perhaps because of today’s surge in attention to this longstanding issue, I feel it critical that the populace understands that the demand for reparations in the U.S. for unpaid labor during the enslavement era and post-slavery discrimination is not novel or new. The claim did not drop from the sky with Ta’Nehisi Coates’ brilliant treatise, “The Case for Reparations,” in The Atlantic, or from Randall Robinson’s impassioned book, “The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks,” both of which galvanized the issue in different decades and thrust it into national conversation.

Although there have been hills and valleys in national attention to the issue, there has been no substantial period of time when the call for redress was not passionately voiced. The first formal record of a petition for reparations in the United States was pursued and won by a formerly enslaved woman, Belinda Royall. Professor Ray Winbush’s book, “Belinda’s Petition,” describes a petition she presented to the Massachusetts General Assembly in 1783, requesting a pension from the proceeds of her enslaver’s estate — an estate partly the product of her own uncompensated labor. Belinda’s petition yielded a pension of 15 pounds and 12 shillings. Former U.S. Civil Rights Commissioner Mary Frances Berry illuminated the case of Callie House in her book, “My Face Is Black Is True.” Callie, along with Rev. Isaiah Dickerson, headed the first mass reparations movement in the United States, founded in 1898. The National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief Bounty and Pension Association had 600,000 dues-paying members who sought to obtain compensation for slavery from federal agencies. During the 1920s, Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association galvanized hundreds of thousands of Black people seeking repatriation with reparation, proclaiming, “Hand back to us our own civilisation. Hand back to us that which you have robbed and exploited of us … for the last 500 years.” During the 1950s and 1960s, New York’s Queen Mother Audley Moore was perhaps the best-known advocate for reparations. As president of the Universal Association of Ethiopian Women, she presented a petition against genocide and for self-determination, land, and reparations to the United Nations in both 1957 and 1959. She was active in every major reparations movement until her death in 1996.

Queen Mother Audley Moore

Credit: Associated Press

In his 1963 book, “Why We Can’t Wait,” Dr. Martin Luther King proposed a “Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged,” which emphasized redress for both the historical victimization and exploitation of Blacks as well as their present-day degradation. “The ancient common law has always provided a remedy for the appropriation of labor on one human being by another,” he wrote. “This law should be made to apply for the American Negroes.” After the Black Panther Party’s stance in 1966, the Republic of New Afrika proclaimed in its 1968 “Declaration of Independence:

“We claim no rights from the United States of America other than those rights belonging to people anywhere in the world, and these include the right to damages, reparations, due us from the grievous injuries sustained by ourselves and our ancestors by reason of United States’ lawlessness.”

In April 1969, the “Black Manifesto” was adopted at a National Black Economic Development Conference. The manifesto, presented by civil rights activist James Forman, included a demand that white churches and synagogues pay $500 million in reparations to Blacks in the U.S. The amount was based on a calculation of $15 for each of the estimated 20 to 30 million African Americans residing in the U.S. He touted it as only the beginning of the amount owed. The following month, Forman interrupted Sunday service at Riverside Church in New York to announce the reparations demand from the “Black Manifesto.” Notably, several religious institutions did respond with financial donations. In 1972, the National Black Political Assembly Convention meeting in Gary, Indiana, adopted “The Anti-Depression Program,” an act authorizing the payment of a sum of money in reparations for slavery as well as the creation of a negotiating commission to determine kind, dates, and other details of paying reparations. Consistently, the Nation of Islam’s publications — such as Muhammad Speaks and, later, The Final Call — have demanded that the United States exempt Black people “from all taxation as long as we are deprived of equal justice.”

The Modern-Day Reparations Movement

But it was the end of the 20th century that brought broad national attention to the call for reparations for people of African descent in the United States with the founding of the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (NCOBRA). I was proud to be a founding member of NCOBRA at the historic gathering on Sept. 26, 1987, which brought together diverse groups under one umbrella, from the Republic of New Afrika to the National Conference of Black Lawyers. For its first decade in existence, I served as chair of NCOBRA’s legislative commission. Since the creation of NCOBRA, the demand for reparations in the United States substantially leaped forward, generating what I’ve dubbed “The Modern-Day Reparations Movement.” Inspired by and organized on the heels of the passage of the 1988 Civil Liberties Act, which granted reparations to Japanese-Americans for their unjust incarceration during World War II, NCOBRA reinvigorated the demand for reparations for African Americans and broadened the concept through public education, accompanied by legislative and litigation-based initiatives. Also encouraged by the 1988 Civil Liberties Act, Rep. John Conyers introduced a bill in 1989 to “establish a commission to examine the institution of slavery and subsequent racial and economic discrimination against African Americans and the impact of these forces on Black people today.” This commission would be charged with making recommendations to the Congress on appropriate remedies. The bill’s number “H.R. 40” was in remembrance of the unfulfilled 19th-century campaign promise to give freed Blacks 40 acres and a mule. Conyers’ “Commission to Study Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act” provided the cover and vehicle to have a public policy discussion on the issue of reparations in Congress.

Rep. John Conyers

Credit: Associated Press

The 1988 Civil Liberties Act authorized the payment of $20,000 to each Japanese-American detention-camp survivor, a trust fund to be used to educate Americans about the suffering of the Japanese-Americans, a formal apology from the U.S. government, and a pardon for all those convicted of resisting detention camp incarceration. It is a sad commentary that the U.S. government has not taken formal responsibility for its role in the enslavement or post-slavery apartheid segregation of millions of Blacks. It has never attempted reparations to African Americans for the extortion of labor for many generations, deprivation of their freedom and human rights, and terrorism against them throughout the centuries. The U.S. Senate and House did pass symbolic resolutions apologizing for slavery and segregation. However, the 2009 bill passed by the Senate contained a disclaimer that those seeking reparations or cash compensation could not use the apology to support a legal claim against the U.S. Since the introduction of H.R. 40, several state legislatures and scores of city councils across the country have passed reparations-type legislation or resolutions endorsing H.R. 40. In 1990, the Louisiana House of Representatives passed a resolution in support of reparations. In 1991, legislation was introduced in the Massachusetts Senate providing for the payment of reparations for slavery, the slave trade, and individual discrimination against the people of African descent born or residing in the commonwealth of Massachusetts. In 1994, the Florida Legislature paid $150,000 to each of the 11 survivors of the 1923 Rosewood Race Massacre and created a scholarship fund for students of color. In 2001, the California State Assembly passed a resolution in support of reparations. After a four-year investigation, the Tulsa Race Riot Reconciliation Act was enacted in 2001. Oklahoma legislators settled on a scholarship fund and memorial to commemorate the June 1921 massacre that left as many as 300 Black people dead and 40 square blocks of exclusively Black businesses, homes, and schools obliterated. That same year, a bill was introduced in the New York State Assembly to create a “Commission to Quantify the Debt Owed to African Americans.” Bills are also pending within several other state legislatures, but the reparations movement isn’t just targeting state houses. City councils in the states of Arkansas, California, Georgia, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, and the District of Columbia have all passed resolutions in support of H.R. 40. Reparations advocates have also challenged corporations who benefited from the profits made from trafficking in human beings during the enslavement era. Countless companies and industries benefited and were enriched from the profits made as a result of chattel slavery. There are companies that sold life insurance policies on the lives of enslaved persons, such as Aetna, New York Life, and AIG. Financial gains were accrued by the predecessor banks of financial giants like J.P. Morgan Chase and Bank of America. Others with documented ties to slavery included railroads like Norfolk Southern, CSX, Union Pacific, and Canadian National. Newspaper publishers that assisted in the capture of runaway persons include Knight Rider, Tribune, E.W. Scripps, and Gannett. The financial backers of many of the country’s top universities were wealthy slave owners, and it has been disclosed that the reason Georgetown University stands today is because the Jesuits who ran the college used profits from the sale of Black people to continue its operation. Survivors of torture by Chicago police received an unprecedented compensatory package based on a reparations ordinance passed by the Chicago City Council in 2015. Numerous civil and human rights organizations, religious groups, professional organizations, civic groups, sororities, fraternities, and labor unions have also officially endorsed the call for reparations. In 2016, the Movement for Black Lives Policy Table released its platform, which prominently featured the issue of reparations. The role that governments, corporations, industries, religious institutions, educational institutions, private estates, and other entities played in supporting the institution of slavery and its vestiges are roles that can no longer be ignored, dismissed outright, or swept under the rug. The time is now ripe that their involvement be recognized, examined, discussed, and redressed.

The Demand Deserves Serious Consideration

I am part of the inaugural cohort of commissioners on the National African American Reparations Commission (NAARC), convened by the Institute of the Black World 21st Century in 2016. The commission’s preamble asserts:

“No amount of material resources or monetary compensation can ever be sufficient restitution for the spiritual, mental, cultural and physical damages inflicted on Africans by centuries of the MAAFA, the holocaust of enslavement and the institution of chattel slavery.”

Recognizing these as “crimes against humanity,” as acknowledged by the 2001 Durban Declaration and Program of Action of the World Conference Against Racism in South Africa, the preamble goes on to assert that “the devastating damages of enslavement and systems of apartheid and de facto segregation spanned generations to negatively affect the collective well-being of Africans in America to this very moment.” NAARC has advanced a comprehensive, yet preliminary, reparations program to guide reparatory justice demands by people of African descent in the United States. Finally, although my primary focus has been on obtaining reparations for African descendants in the United States, it is critical to recognize that our quest is part of the international movement for reparations as well. As such, I have worked closely with supporters of reparations throughout the world, recognizing that the success of the movement for reparations for diasporic Africans anywhere advances the movement for reparations by Africans and African descendants everywhere. I am thrilled that my quest to have reparations seen as a legitimate concept for African Americans, begun nearly 50 years ago, is becoming a reality. The issue has become more precise, less rhetorical, and has entered the mainstream. And while cash payments remain an important and necessary component of any claim for damages, it is crystal clear today that a reparations settlement can be fashioned in as many ways as necessary to equitably address the countless manifestations of injury sustained from chattel slavery and its continuing vestiges. Some forms of redress may include land, economic development, or scholarships. Other amends may embrace community development, repatriation resources, or truthful textbooks. Still, other areas of reparatory justice may encompass the erection of monuments and museums, pardons for impacted prisoners from the COINTELPRO-era, and repairing the harms from the War on Drugs. Fifty years after I first entered the reparations movement, I’m optimistic. It’s hard not to be when H.R. 40 has been updated to include not just a mere study of proposals but also their development. It’s also hard not to be optimistic when a Senate companion bill to H.R. 40 has been introduced and even more astonishing when some Democratic candidates for the 2020 presidential race are saying they will sign the legislation if elected president. Despite a resurfacing of white supremacy in the U.S., I can see the light at the end of the tunnel. I am buoyed by the reemergence of the spirits of Belinda, Callie House, and Queen Mother Moore as well as the resilience of “Reparations Ray” Jenkins, who kept the fire alive in Rep. Conyers to introduce H.R. 40 year after year. And I am inspired by the words of the great anti-slavery orator Frederick Douglass, who poignantly instructed that “power concedes nothing without a demand.” The demand has been made and the time to seriously consider reparations has finally come.

READ THE FULL REPARATIONS SERIES

Nkechi Taifa is founder and president of The Taifa Group, LLC. An accomplished human rights attorney, she is a justice system reform strategist, advocate, and scholar.

Published May 27, 2020 at 12:05AM via ACLU https://ift.tt/3grc5uE

0 notes

Photo

#Repost @blackhistoryiseverywhereperiod ・・・ Special Field Order No.15 On January 16, 1865, Union General William T. Sherman issued Special Field Order No. 15 which confiscated as Federal property a strip of coastal land extending about 30 miles inland from the Atlantic and stretching from Charleston, South Carolina 245 miles south to Jacksonville, Florida. The order gave most of the roughly 400,000 acres to newly emancipated slaves in forty-acre sections. Those lands became the basis for the slogan “forty acres and a mule” based on the belief that ex-slaves throughout the old Confederacy would be given the confiscated lands of former plantation owners. #40acresandamule #fieldorder15 #atlprotest #representationmatters #reparations #defundthepolice #learnblackhistory #learnamericanhistory #amnesty #amnestyproclamation #bhie #blackhistoryiseverywhere #ibeenblack (at Columbia, South Carolina) https://www.instagram.com/p/CBZQKaHgxmg/?igshid=18egwx0zj8rd6

#repost#40acresandamule#fieldorder15#atlprotest#representationmatters#reparations#defundthepolice#learnblackhistory#learnamericanhistory#amnesty#amnestyproclamation#bhie#blackhistoryiseverywhere#ibeenblack

0 notes

Text

House To Hold Hearing On Slavery Reparations Breitbart ^ | 6/12/19

A House Judiciary subcommittee will hold hearings on reparations next Wednesday, marking the first time in more than a decade that the House will discuss potentially compensating the descendants of slaves.

“The Case for Reparations” author Ta-Nehisi Coates and actor Danny Glover are reportedly set to testify before the House Judiciary Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, and the hearing’s stated purpose will be “to examine, through open and constructive discourse, the legacy of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, its continuing impact on the community and the path to restorative justice,” according to a Thursday Associated Press report.

The June 19 hearing also “coincides with Juneteenth, a cultural holiday commemorating the emancipation of enslaved blacks in America.”

Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee (D-TX), who sits on the subcommittee, again introduced H.R. 40 earlier this year to create a reparations commission. Jackson Lee said her bill would create a commission “to study the impact of slavery and continuing discrimination against African-Americans, resulting directly and indirectly from slavery to segregation to the desegregation process and the present day.” She added in January that the “commission would also make recommendations concerning any form of apology and compensation to begin the long delayed process of atonement for slavery.”

“The impact of slavery and its vestiges continues to effect African Americans and indeed all Americans in communities throughout our nation,” Jackson Lee said. “This legislation is intended to examine the institution of slavery in the colonies and the United States from 1619 to the present, and further recommend appropriate remedies. Since the initial introduction of this legislation, its proponents have made substantial progress in elevating the discussion of reparations and reparatory justice at the national level and joining the mainstream international debate on the issues.

(Excerpt) Read more at breitbart.com ...

TOPICS: Constitution/Conservatism; Crime/Corruption; Culture/Society KEYWORDS: househearing; racism; reparations; slavery

________________________________________________

OPINION: How are they going to know who are the ‘Decedents’ of slaves in this country. They have been many, from African Countries that have come to the United States after Slavery. So, who is going to make that call.

Just asking the ‘Million’ dollar question because its going to come-up for a ‘Reality’ check and someone is going to have to answer that question.

____________________________________________________________________

INDIVIDUALS COMMENTS\POSTS:

To: Altura Ct. The amount of money spent on The War on Poverty is more than the sum required to buy every share of every company on the NYSE.

Then enough money would be left over to buy every acre of farmland in the USA.

I hear that stat about 11 years ago.

2 posted on 6/13/2019, 10:36:06 AM by gaijin ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- To: All If we give them money will they shut up?

3 posted on 6/13/2019, 10:36:22 AM by JonPreston ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- To: Altura Ct. What about reparations for conservatives? Feelin’ repressed...

4 posted on 6/13/2019, 10:37:56 AM by bigbob ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- To: Altura Ct. House Dems: fiddling while Rome (America) burns...

5 posted on 6/13/2019, 10:38:39 AM by jeffc (The U.S. media are our enemy) ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- To: JonPreston If we give them money will they shut up? White people would get all the money back in no time.

6 posted on 6/13/2019, 10:38:56 AM by dfwgator (Endut! Hoch Hech!)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

To: JonPreston and the path to restorative justice IOW, whitey must pay.

If we give them money will they shut up?

No - they will demand more. You know how this works.

7 posted on 6/13/2019, 10:38:57 AM by grobdriver (BUILD KATE'S WALL!) ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- To: Altura Ct. I’ve traced my lineage back to the 1600s. Not a single one of my ancestors owned slaves. Not even the line that ran through the southern states.

I don’t owe anybody one damn dime.

8 posted on 6/13/2019, 10:39:21 AM by Not A Snowbird (I trust President Trump.) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ To: Altura Ct. Yup....every living slave needs compensation for slavery in the USA...

9 posted on 6/13/2019, 10:40:30 AM by Popman ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- To: Altura Ct. If I were the Republicans I would this whole hearing about the Democrat Slave Plantations and their creation of the KKK... Every Republican should fall in line with their own part in this play and paint a TRUE Picture of the Democrat Slave Masters.

10 posted on 6/13/2019, 10:41:44 AM by eyeamok ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- To: JonPreston They’ll shut up until the money is gone, which won’t take long.. Then they, and their descendants will want more, since it’s Whitey’s fault they didn’t know how to handle the money. Cultural disadvantage, you know.

11 posted on 6/13/2019, 10:41:51 AM by Pearls Before Swine ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- To: Popman The archives in Salt Lake will be running in over-drive.

12 posted on 6/13/2019, 10:41:57 AM by ptsal ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- To: Altura Ct. Slavery reparations... Not really something for government, more sounds like a game to play in the court. Now, if you’re talking reparations for treaties which were violated, actual government signed documents backed by the full faith of the government (until they were broken by the same...), there I think you’ve got something to hold hearings on.

Not going to hold my breath.

13 posted on 6/13/2019, 10:41:57 AM by kingu (Everything starts with slashing the size and scope of the federal government.) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- To: Altura Ct. First let’s get an accurate assessment of how many BLACK Americans are on Welfare.

You always hear “there’s more white people on welfare than black” which is true- but there are 8 times as many white people in the country.

if there was 8 times as many white people on welfare it would be a fair comparison, but it is closer to 1:1.

The correct question is what percentage of the black population collects welfare.

I have NEVER seen that statistic. EVER.

I know they are over-represented in government jobs, where AT LEAST 20% are filled by minorities. Some places as high as 50%.

So, nearly half are on welfare, the other half have government jobs?

14 posted on 6/13/2019, 10:42:53 AM by Mr. K (No consequence of repealing obamacare is worse than obamacare itself.) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ To: Altura Ct. Danny Glover....noted academic.

15 posted on 6/13/2019, 10:43:15 AM by ealgeone ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- To: JonPreston Nope — just like a blackmailer — they will keep coming back for more. No amount of money will ever be enough.

16 posted on 6/13/2019, 10:43:16 AM by Polyxene (Out of the depths I have cried to Thee, O Lord; Lord, hear my voice.) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- To: Altura Ct. How about we just name a street in the ghetto after each and every one of them?

17 posted on 6/13/2019, 10:43:16 AM by Beagle8U (It's not whether you win or lose, it's how you place the blame.) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- To: JonPreston No.

18 posted on 6/13/2019, 10:43:46 AM by ealgeone ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- To: JonPreston If we give them money will they shut up? Never ever. It is a gravy train and grievance industry that knows no end. Maybe if whites were all dead...

19 posted on 6/13/2019, 10:44:19 AM by Altura Ct. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ To: Not A Snowbird I’ve traced my lineage back to the 1600s. Not a single one of my ancestors owned slaves. They were too busy being oppressed by the French, Germans, Russians and damned near anybody else who stumbled through central Europe in those days.

Phooey on the congress of the USA. Go home, if you have one. Get a job if you can hold one. You are a blight on our civilization.

20 posted on 6/13/2019, 10:44:59 AM by Don Corleone (Nothing makes the delusional more furious than truth.) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

0 notes

Photo

"Mr. Darity has been mulling that question for years, and is writing a book on reparations with Kirsten Mullen, due out next year. He begins with the cost of an acre in 1865: about $10. Forty acres divided among a family of four comes to 10 acres per person, or about $100 for each of the four million former slaves. Taking account of compounding interest and inflation, Mr. Darity has put the present value at $2.6 trillion. Assuming roughly 30 million descendants of ex-slaves, he concluded it worked out to about $80,000 a person." What Reparations for Slavery Might Look Like in 2019. The idea of economic amends for past injustices and persistent disparities is getting renewed attention. Here are some formulas for achieving the aim. As the Civil War wound down in 1865, Gen. William T. Sherman made the promise that would come to be known as “40 acres and a mule” — redistributing a huge tract of Atlantic coastline to black Americans recently freed from bondage. President Abraham Lincoln and Congress gave their approval, and soon 40,000 freedmen in the South had started to plant and build. Within months of Lincoln’s assassination, though, President Johnson rescinded the order and returned the land to its former owners. Congress made another attempt at compensation, but Johnson vetoed it. Now, in the early phase of the 2020 presidential campaign, the question of compensating black Americans for suffering under slavery and other forms of racial injustice has resurfaced. The current effort focuses on a congressional bill that would commission a study on reparations, a version of legislation first introduced in 1989. Several Democratic presidential hopefuls have declared their support, including Senators Kamala Harris of California, Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Cory Booker of New Jersey and former Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julián Castro. (at Atlanta, Georgia) https://www.instagram.com/p/Bx5Nkl9lZ_M/?igshid=11s5vx71i7pzy

0 notes

Text

John Deere - Products, Machines and Equipment

One of one of the most preferred and incredible brand of farm tools these days includes John Deere tractors. It appears like despite where you look, they can be found cutting the turf of someone's house or tilling the land of a significant ranch. What makes them so appealing are their smooth appearance and also their long life period. Some proprietors of these tractors can flaunt that the tractor has actually remained in their ownership, and functioning properly, for 20-30 years. Think concerning this; using a tractor to cut a grass means you will certainly be using it as soon as weekly or 2 weeks from April to October (maybe also November). That is a whole lot of gas mileage for a tractor, which requires to be executed maintenance every currently and also after that. Depending on how huge your backyard is, there are different types and also dimension tractors provided by John Deere. If you have a bigger lawn and also you do a great deal of horticulture and landscaping on your own, you certainly will want a tractor that can reduce the grass and transport products from one area to one more. There are J.D. tractors on the marketplace today that can cut the grass and likewise have a front end loader affixed to it. This tractor is the 2000 Series as well as they are recognized as Compact Utility Tractors.

If you have 5 or more acres of land, which means you simply could possess a ranch, then the bigger brand of John Deere tractors are the means to go. The 5E Limited Series has a front end loader but it does not have lawn cutting or land tilling abilities. It is a perfect tractor for removing dust, soil, rocks, brush as well as various other products from your land or from inside a barn or garage ought to the requirement arise. It is difficult to find a great deal of made use of John Deere tractors available for sale in the United States due to the fact that so couple of individuals market their tractors at an age where they can still be made use of for a couple more years. John Deere tractors have such a lengthy life expectancy that numerous proprietors use the tractor till it can not be utilized anymore and afterwards they head out as well as purchase a brand new one from the business to replace the old tractor. User as well as repar service guidebooks for John Deere machines are available below: https://www.repairloader.com/manual.php/8542fe6 .

0 notes

Link