#1941 my beloved you will always be famous

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

1941.

#good omens#goodomensedit#goodomensgifs#dailygoodomens#goodomenssource#usergif#usereena#usersugar#usermullet#userisaiah#saryasy#stuck at home with bronchitis so decided to fuck around and try some new stuff with photoshop#1941 my beloved you will always be famous#i live in the 1941 flashback and it lives in me#myedits#gif#flashing gif#tw flashing

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

May I ask a possibly stupid question? How is Sanderson Hawkins still so young? I was doing reaserch for my paper on The Sandman and the timeline was really distracting for me, since Sanderson is a relative of his. He should be a lot older than he is, shouldn't he? There was a period of time wherein he seemed to fall off the face of the Earth, so maybe time travel was involved?

Please, let me know if you have the answer to this!

Ok so, you're not wrong in that Sanderson "Sandy" Hawkins is much older than he looks.

(A portrait of Sandy the Golden Boy drawn by famous pop artist Jack Kirby) Sanderson Hawkins isn't actually related to the original Sandman, Wesley Dodds by blood. He was the nephew of Dodds' lifelong companion, famous crime novelist Dian Belmont. (Who is famous enough on her own that some people freak out when I tell them that little factoid). Despite Dodds and Belmont having a lifelong romantic partnership and cohabitating for most of their adult lives, the two never married.

"Sandy" discovered Dodds' identity when he stowed away in the older man's attic after being taken to visit by Dian, seeing Dodds being approached by the Justice Society to confer on a case. Thus discovering Dodds' identity, Sandy became his partner in crime fighting, Hawkins' sunny disposition inspiring the Sandman's costume change to be more of an inviting and trusted public figure.

Sandy served with distinction as an associate member of the Justice Society and a member of the Young All-Stars where he served as pseudo leader due to his higher experience as a kid superhero.

Sanderson was 13 when he and Dodds originally met in the latter days of 1941. Meaning he was born in December of 1928.

Which would make THIS man 96.

(Former official portrait of Hawkins in his persona as "Sand")

Maintain professional detachment, maintain professional detachment, MAINTAIN PROFESSIONAL-!

*ahem* Anyway.

Like you said, the trick is in the time very soon before the forced disbandment of the JSA that Sandy the Golden Boy seemed to vanish from the face of the Earth.

Caught in the blast of an experimental silicide gun and bombarded with radioactive particulates, Hawkins was mutated into a hulking sand monster with a violent temper. Kept in containment for decades while Dodds attempted to find a cure he was accidentally released very soon after the JSA was pulled back into the public eye around the foundation of the Justice League.

Rescued by the combined efforts of both teams he was returned to a humanoid form, but in reality his skin, his muscles, his very cells had been replaced by living sand that he now had the ability to manipulate at will.

Hawkins faded again from the public eye, trying to wrap his mind around both his new state of body AND the decades he had lost in a haze of rage and pain.

It wasn't until Dodds' death that Hawkins was called back to where he had always belonged. Originally going by the name Sand in his heroic persona until being contacted by Dodds via the prophetic dreams that animated Dodds' own heroic career, Hawkins finally donned the heroic persona that was his inheritance.

(Hawkins' current official portrait)

And the Sandman was reborn.

Since then Hawkins has been a publically active member of the Justice Society's line up and has worked tirelessly to maintain the legacy of his beloved "Uncle Wes". The most famous outgrowth of which being when he opened his Uncle's estate to historians Matt Wagner and Steven Seagle, even giving them access to Dodds' dream journals stretching back before his debut in 1939.

I respect the hell out of Sandy Hawkins. He lost decades of his young life to an accident, work up to a world not of his making in a body that was not his own, lost the two people he cared the most about within months of one another and then, when called, stood in the shape of his mentor and carried his steps into the future.

His existence is the reminder of a dream. That those who seek to do harm shall never haunt the innocent and the righteous in the darkness.

That all evildoers shall behold the same nightmare at the calling of the Sandman.

#dc#dcu#dc comics#dc universe#superhero#comics#tw unreality#unreality#unreality blog#ask game#ask blog#asks open#please interact#worldbuilding#sandman#sandy hawkins#wesley dodds#sandy the golden boy

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Borrowed from Bonnie Nadaskay Coody

"The Art of Dr. Seuss Collection, Published by Chaseart Companies

DR. SEUSS USE OF RACIST IMAGES

Theodor Seuss Geisel (aka Dr. Seuss) created thousands of cartoons, illustrations, paintings, sculptures, and stories over the course of his 70-year career. While the vast majority of the works he produced are positive and inspiring, Ted Geisel also drew a handful of early images, which are disturbing. These racially stereotypical drawings were hurtful then and are still hurtful today. However, Ted’s cartoons and books also reflect his evolution. Later works, such as The Sneetches or Horton Hears a Who!, emphasize inclusion and acceptance. Ted would later edit some of his inappropriate images, depicting his characters in a more respectful manner.

Born in 1904, Ted Geisel grew up in Springfield, Massachusetts. Well before any of his iconic books were written, he embraced the Dr. Seuss moniker, making his living in New York City (1927–1941) writing and cartooning for several popular magazines: Judge, Look, The Saturday Evening Post, New York Woman, Stage, and Vanity Fair. His famous “Flit” advertisements for Standard Oil were carried in newspapers around the country, making him a “print celebrity.” Yet, while everyone recognized the name Dr. Seuss, few actually could pick out the man, Ted Geisel.

Stunned by the Great Depression and the onset of War in Europe, in January 1941, Dr. Seuss joined ranks with the bunch of “cockeyed crusaders” at PM magazine, producing three or more cartoons a week assailing the “The Axis Powers,” and finding himself a staunch supporter of President Roosevelt, who felt America’s entry into the War was inevitable. “PM was against people who pushed other people around,” Ted said. “I liked that.”

Still, it was not enough for Ted. On January 7, 1943, Captain Theodor Seuss Geisel was inducted into the army, assigned to the Information and Education Division. Within a few weeks he joined Frank Capra’s unit at “Fort Fox.” As a creative, he wasn’t alone in making this sacrifice. Historian Paul Horgan, screenwriter Leonard Spigelgass, composer Meredith Willson, novelist Irving Wallace, and illustrator P.D. Eastman worked with him alongside the civilian animators, Chuck Jones and Friz Freleng of Warner Brothers. Ted mustered out on January 13, 1946 as a lieutenant colonel, receiving the Legion of Merit for “exceptionally meritorious service in planning and producing films, particularly those utilizing animated cartoons, for training, informing, and enhancing the morale of troops.”

When Ted first began to write for children in 1937, many representations of people of color in the media were unfortunately depicted through racial stereotypes. In his first book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, his work was no exception. For example, to represent a lone Asian character, Ted employed “traditional clothing” and chopsticks to depict his ethnicity. He originally referred to this character as a “Chinaman” and showed his skin color as yellow. It is important to note that in a later reprint he removed the color and changed the text to “a Chinese man.”

Geisel’s great nephew Ted Owens recalled his uncle’s decision to make that change: "It was the first time he had changed one of his books . . . . Art and humanity are always evolving."

Mulberry Street was written in 1937. By contrast, the much-beloved The Sneetches was written in 1961 just as the Civil Rights Movement was well underway. Ted wrote The Sneetches as a parable about equality. By drawing bird-beings, he transcended the boundaries and pitfalls of using humans as characters, and allowed all readers to relate to the characters as best they could. On March 2, 2016, President Obama agreed with Dr. Seuss telling a group of interns: “Pretty much all the stuff you need to know is in Dr. Seuss. It’s like the Star-Belly Sneetches, you know? We’re all the same, so why would we treat somebody differently just because they don’t have a star on their belly?”

“Justice is not always about canceling someone and their body of work. Sometimes it looks like providing room for restorative justice to take place,” writes Danielle Slaughter for Mamademics. “In my opinion, Dr. Seuss, using the remainder of his career to focus on writing books full of important lessons, is an example of restorative justice.”

Slaughter also notes that three of Dr. Seuss’s most well-known later works, Horton Hears a Who!, The Lorax, and The Sneetches, “teach about the importance of inclusion and acceptance of others and yourself.”

In his book, Becoming Dr. Seuss: Theodor Geisel and the Making of an American Imagination, biographer Brian Jay Jones says that Dr. Seuss drew some “racist stereotypes in his early work.” Jones told The San Diego Union-Tribune: “As I say in the book, it’s not a great look for him. But he evolves.” By the end of the 1950s, Geisel had written Horton Hears a Who!, which is dedicated to a Japanese friend and is seen by scholars now as an apology for the earlier cartoons. He’d written Yertle the Turtle, an anti-fascist send-up of Hitler, and he’d penned a magazine story that would become the anti-discrimination book The Sneetches. “I don’t think you write a book like The Sneetches if you haven’t evolved,” Jones said.

Dr. Seuss’s later works show an evolution of values and beliefs. Those who knew him believe that if he were alive today he would have jumped at the chance to be a part of the country’s evolving dialogue about diversity and inclusion.

Dr. Seuss images and text are trademarks of Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P. Used by permission.

Dr. Seuss Properties TM & © 2021 Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P. All Rights Reserved."

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Tis the season to spread cheer and I’m doing my part by recommending classic movies, paying them forward in hopes that these memorable distractions take people’s minds off negative goings on. I’m asking that you join me, recommend your favorites and #PayClassicsForward on your blogs, by noting your recommendations in the comments or sharing across social media.

Let’s give the gift of movies.

Here’s the challenge…pick movie recommendations to the “12 Days of Christmas” theme as I’ve done below. Keep in mind that movie choices should be those you think would appeal to non-classics fans. Let’s grow our community and #PayClassicsForward

Have fun!

On the first day of Christmas, etc. etc…

One hat

The “one” listing is always a difficult one due to the fact that classics lend themselves to plenty of choices. That said, I came up with a category that encompasses important decades and several genre of film – the fedora. By following the history of the fedora in film you’ll be made privy to the best gangsters, greatest funny men, and most memorable lovers of Hollywood’s golden age. So here it is, a signature fedora:

Note that in researching my favorite fedora portrait I learned that trilbys are often mistaken for fedoras. Since experts seem to be confused between the two types of classic men’s hats that leaves little hope for me. I can’t say for sure whether Bogart is wearing a trilby in the above image, but he may well be. Descriptions of this type of hat explain the rims are shorter than your average fedoras. Either way, it’s a cool, suave look and Bogie rocks it.

From GQ: What’s the difference between a fedora and a trilby?

Answer: Traditionally a fedora has a wide brim and in the UK a wide ribbon band and bow. A trilby has a narrow brim and narrow ribbon, although there are some American trilbies that still have the wide ribbon.

Two Fairbanks

Things were not simple between Douglas Fairbanks and Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. as it is for many families, but the son wore his father’s name proudly. I chose this father and son combination because if you watch their films you’ll get a healthy helping of everything from silent adventure to pre-code delicacies through some terrific television work. These are careers worth following.

Three Trios

There are quite a few choices for memorable trios in film including Cattle rustlers Robert Hightower (John Wayne), Pedro “Pete” Rocafuerte (Pedro Armendáriz), and William Kearney (Harry Carey, Jr.) in John Ford’s 3 Godfathers. That one is definitely difficult to pass up. That said, I think the following trios are likely to be looked at less by casual fans and they all deserve attention. These are my choices of trios in movies:

They are such a joy to behold. I remember them fondly from my days as a child watching them on TV. It seemed then that they appeared in a million movies, but that wasn’t the case. Still, these siblings are a joy in films like Buck Pirates with Abbott and Costello and their film debut in Albert S. Rogell’s Argentine Nights (1940). The Andrews Sisters made 17 films, more than any other singing group and all are a terrific way to be introduced to the movies. If that record does not impress you, then maybe this one will: LaVerne, Maxene, and Patty garnered 113 charted Billboard hits with 46 of those reaching the top 10. That’s more than Elvis Presley or The Beatles.

youtube

I have nothing against Disney. In fact, I enjoy their classic animated films immensely. Due to that I’m less than enthusiastic about their constant remakes, which – in my opinion – disrespects those wonderful, older film accomplishments. Today I pay tribute to one of them by way of a trio of glorious characters made in the memorable Disney vein we’ve all come to know and love, that combination of warmth and delightful comedy that permeate those wonderful films. These characters are Princess Aurora’s three good fairy godmothers Flora, Fauna and Merryweather in Disney’s 1959 classic Sleeping Beauty. They alone pay tribute to an enchanting legacy.

“Each of us the child may bless, with a single gift no more, no less.”

The final mention here goes to three Russian envoys who have arrived in Paris to sell a fortune in jewelry, imperial jewelry, the money of which is to go to the Russian government, which is in need of cash. The three, Iranoff, Buljanoff and Kopalski (played hilariously by Sig Ruman, Felix Bressart and Alexander Granach, respectively) who are supposed to be doing work for the Russian government, immediately get caught up in the excesses of capitalism and fail to sell the jewelry. Moscow then sends a special envoy to Paris to investigate what’s going on with the trio and the jewelry. The envoy is the rigid and humorless, Comrade Yakushova – Ninotchka (Greta Garbo). The charming Melvyn Douglas plays Ninotchka’s love interest in Ernst Lubitsch’s delightful comedy, but it’s the three envoys in the hands of Ruman, Bressart and Granach that make this movie among the greats in the annals of comedy. I just want to get to know them better and so should you.

Ninotchka with Iranoff, Buljanoff, and Kopalski

Four Skippy Performances

It’s no wonder this wire-haired terrier was the highest paid canine star of his day. Often referred to as “Asta,” thanks to his successful appearances in The Thin Man movies, his real name was Skippy – and we love him to tears. Although I’m choosing only four of his film performances, Skippy never made a bad movie and starred opposite some of Hollywood’s biggest names. If you keep an eye out for Skippy’s filmography on TCM, you will no doubt be introduced to an astounding talent as well as a terrific movie. It’s guaranteed. My Skippy suggestions are:

Skippy as Asta in The Thin Man movies opposite William Powell and Myrna Loy as Nick and Nora Charles. I can’t imagine you haven’t seen The Thin Man (1934), but may not have given any of the sequels a try. If that’s the case you will be delighted by Skippy in any one of his key performances:

in ANOTHER THIN MAN

in AFTER THE THIN MAN

Skippy is wonderful as Mr. Smith in The Awful Truth. Worth a custody dispute between Warriner and Warriner played by Cary Grant and Irene Dunne, this time Skippy is required to add straight drama to his repertoire as he is required to choose between his two humans right off the bat. There’s also plenty for him to do on the comedy front, however, so this one is a must-see.

forced to choose between the Warriners in court

front and center in the awful truth

Skippy as George in Howard Hawks’ Bringing Up Baby opposite Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant. Another terrific outing for our favorite pooch as he is central to action thanks to his burying abilities.

Holding his own in Hawks’ beloved screwball

This sequel to Norman Z. McLeod’s 1937 hit Topper lacks some of the charm of its predecessor, but the talents of Constance Bennett, Roland Young, Billie Burke, Alan Mowbry, and Skippy make it well worth your time. Here, Skippy matched Bennett’s ghostly wit by ghostly wit in a role that stretches his talents to matters beyond this world and he approaches it with signature enthusiasm.

so famous he made it into this spectacular publicity photo with Constance Bennett

Five Lords-a-leaping

No explanation needed.

Cagney

Nicholas Brothers

Kelly

Astaire

Six Vivien Leigh GWTW Tests

Gone With the Wind is celebrating its 80th anniversary on December 15 and, as the biggest, most famous movie ever made, it deserves at least a mention here.

On that day in 1939, Atlanta’s Loew’s Grand Theater was buzzing with Hollywood’s biggest names. It was such an occasion for Atlanta that the film’s opening was a 3-day event as Governor Eurith Dickinson Rivers declared a three-day holiday. Other politicians asked that Georgians dress in period clothing. A lot had happened in Hollywood leading up to that premiere though including the famous search for the film’s leading lady, the protagonist of Margaret Mitchell’s 1936 blockbuster novel, Scarlett O’Hara. Every female star it seems auditioned for the part. Among them were Bette Davis, Jean Arthur, Tallulah Bankhead, Joan Bennett, Claudette Colbert, Frances Dee, and Paulette Goddard who, as stories go, was close to being chosen. As we all know, however, Scarlett went to the lovely, British Vivien Leigh who possessed an outstanding talent. Leigh made the part her own and, along with the film, became tantamount to Hollywood royalty. To honor Vivien Leigh and her memorable Scarlett O’Hara here are six make-up and wardrobe test stills:

Seven Justices

Judge James K. Hardy in the Andy Hardy movie series

Judge Margaret Turner in The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer

Judge Taylor in To Kill a Mockingbird

Judge Weaver in Anatomy of a Murder

Judge Henry X. Harper in Miracle on 34th Street

Judge Dan Haywood in Judgment at Nuremberg

Judge Chamberlain Haller in My Cousin Vinny

Eight Serials

Follow the links to watch episodes of these dramatically exciting serials. It might take a few chapters for you to get hooked, but you’ll get hooked.

The Perils of Pauline (1914) starring Pearl White

The Vanishing Legion (1931) starring Harry Carey and Edwina Booth

The Green Hornet (1940) starring Gordon Jones

Zorro Rides Again (1937) starring John Carroll

The Master Mystery (1918) starring Harry Houdini

Flash Gordon (1936) starring Buster Crabbe

The Phantom Creeps (1939) starring Bela Lugosi

Holt of the Secret Service (1941) starring Jack Holt

Nine Ladies Dancing

Ann Miller

Ruby Keeler

Eleanor Powell

Lena Horne

Betty Grable

Vera-Ellen

Cyd Charisse

Ginger Rogers

Dorothy Dandridge

Ten Directors

Watch their movies… live, love, learn, and laugh.

Michael Curtiz

Akira Kurosawa

William Wyler

Fritz Lang

Ernst Lubitsch

John Ford

Alfred Hitchcock

Mervyn LeRoy

Ida Lupino

Lois Weber

Eleven Movies about Millionaires

Since I recommended movies about hobos in a previous year, I thought the time came for millionaires. There are many wonderful movies about the super rich, particularly during the Great Depression when audiences loved seeing the plight of these people play out for laughs. That theme made for some of film history’s best screwball comedies. The super rich, however, have lent themselves for entertaining movie fare ever since the movies began and in every genre. Check out this terrific list from Forbes spotlighting millionaires in movies.

As for me, I have quite a few favorites with millionaire themes that appeal to most others as well. These include such popular titles as The Philadelphia Story, the shenanigans of the Charleses in The Thin Man movies, My Man Godfrey, The Lady Eve, How to Marry a Millionaire, and movies featuring recognizable names like Charles Foster Kane and Bruce Wayne. For this purpose, however, I recommend lesser known, but worthy millionaire movie stories I’ve watched through the years – some in terrible condition, a few greats, and some for plain ole fun. Here are the 11 rich and classic…

Phil Rosen’s Extravagance (1930)

John G. Adolfi’s The Millionaire (1931)

Clarence G. Badger’s Miss Brewster’s Millions (1926)

Frank Tuttle’s Love Among the Millionaires (1930)

Mitchell Leisen’s Easy Living (1937)

Anthony Asquith’s The Millionairess (1960)

Robert Moore’s Murder by Death (1976)

William Asher’s Bikini Beach (1964)

Walter Lang’s I’ll Give a Million (1938)

George Marshall’s A Millionaire for Christy (1951)

Roy Del Ruth’s Kid Millions (1934)

EXTRAVAGANCE (1930_

THE MILLIONAIRE (1931)

LOVE AMONG THE MILLIONAIRES (1930)

MISS BREWSTER’S MILLIONS (1926)

MURDER BY DEATH (1976)

I’LL GIVE A MILLION (1938)

A MILLIONAIRE FOR CHRISTY (1951)

THE MILLIONAIRESS (1960)

KID MILLIONS (1934)

BIKINI BEACH (1964)

EASY LIVING (1937)

Twelve Feature Acting Debuts

Some of my favorite and/or most memorable film debuts…

Jamie Lee Curtis in Halloween – effective after all these years.

Orson Welles in Citizen Kane – although Welles’ performance is what I find hardest to like in Kane, I cannot deny its impact and status among characters in film.

Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday – appropriate introduction for royalty in film and in life. She charms you from the first moment.

Eva Marie Saint in On the Waterfront – exclamation point to begin a stellar movie career.

Barbra Streisand in Funny Girl – a tour de force and a phenomenon

Peter Lorre in M – brilliant, nightmarish, heartbreaking. Described by director Fritz Lang as “one of the best in film history.” I agree.

Julie Andrews in Mary Poppins – Her debut should have been as Eliza Doolittle in My Fair Lady, but we’ll take this and so did she. Not only did Andrews win the Best Actress Academy Award for her portrayal of the magical nanny, but she won the hearts of the world in the process.

Timothy Hutton in Ordinary People – ordinarily superb.

Angela Lansbury in Gaslight – small part, big impact. Undeniable screen presence.

Edward Norton in Primal Fear – convincing and chilling.

Greer Garson in Goodbye, Mr. Chips – She wanted a worthy role as her screen introduction. She got it. She killed it – as she did from that moment on.

Eddie Murphy in 48 Hours – I love this performance highlighting the scope of Murphy’s talent.

I gave this final topic a lot of thought as there are many worthy contenders. For instance, I’m sure many would choose James Dean’s turn in East of Eden, as big a legend-ensuring performance as there ever was, but it’s not a favorite of mine. Tatum O’Neill’s performance in Paper Moon is another one I considered as were Marlee Matlin’s in Children of a Lesser God and Lupita Nyong’o heartbreaking Patsey in 12 Years a Slave. Finally, I adore Robert Duvall’s debut appearance in To Kill a Mockingbird. And I could go on and on. We just have an embarrassment of riches.

♥

Phew! There you have this year’s movie recommendations. I hope you enjoyed the list and that – in the spirit of Christmas – you take this challenge and…

#PayClassicsForward

Visit previous year’s lists as shown:

2015

2016

2017

2018

The Challenge: #PayClassicsForward for Christmas ‘Tis the season to spread cheer and I’m doing my part by recommending classic movies, paying them forward in hopes that these memorable distractions take people’s minds off negative goings on.

#12 Days of Christmas#12 Days of Classics#Movie Recommendations#Pay Classics Forward#Pay Classics Forward for Christmas

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Noir Film Recommendations

Here is a classic noir films recommendation list I promised @madame-madeleine weeks ago. I put them in release order, because trying to organize them from personal best to least best was going to take too long. There are plenty of noir films out there besides these, this list just has my personal favorites!

The Maltese Falcon (1941)

Summary: A private detective takes on a case that involves him with three eccentric criminals, a gorgeous liar, and their quest for a priceless statuette.

Recommendation: This one's a classic for a reason, though I actually watched this film first for Peter Lorre and second for everything else. But it's a great film, with fascinating characters and an engaging plot.

This Gun For Hire (1942)

Summary: When assassin Philip Raven shoots a blackmailer and his beautiful female companion dead, he is paid off in marked bills by his treasonous employer who is working with foreign spies.

Recommendation: I love Alan Ladd, and his portrayal of a ruthless assassin is amazing here. Raven's dynamic with Ellen, a woman he encounters in the film, is also really fascinating, and I think both the story and the characters will keep you engaged!

Arsenic and Old Lace (1944)

Summary: A drama critic learns on his wedding day that his beloved maiden aunts are homicidal maniacs, and that insanity runs in his family.

Recommendation: Listen, I know this is a parody and that apparently Cary Grant hated his performance in this movie. It's still in my top five favorite movies of all time. Everyone is hysterical, the jokes are great, and this film cemented my love of Peter Lorre. I loved this movie so much I once requested it for Yuletide and got an amazing fic!

Double Indemnity (1944)

Summary: An insurance representative lets himself be talked into a murder/insurance fraud scheme that arouses the suspicion of an insurance investigator.

Recommendation: This film has one of my favorite femme fatales, and the dialogue is great. Inspired by a true story, this one's a great psychological maze, and I really enjoyed it.

Gaslight (1944)

Summary: After the murder of her famous aunt, a woman is sent to study in Italy to become a great opera singer as well. While there, she falls in love. The two return to London, and she begins to notice strange goings-on: missing pictures, strange footsteps in the night and gaslights that dim without being touched.

Recommendation: "Fun" fact, this film and the play it was based on inspired the term gaslighting, which means to "manipulate by psychological means into questioning their own sanity." You can probably guess what happens in this movie, but oh man, that final scene between husband and wife? One of my all-time favorite scenes in any movie.

Laura (1944)

Summary: A police detective falls in love with the woman whose murder he is investigating.

Recommendation: I love this one. It's such a twisty, psychological thriller, and I love Laura's presence throughout this, and the way the detective falls in love with her the more he learns about her-- or at least falls in love with his concept of her.

Gilda (1946)

Summary: A small-time gambler hired to work in a Buenos Aires casino learns that his ex-lover is married to his employer.

Recommendation: GILDA! I love her so much, and everyone's dynamics here are fascinating. Lots of homoerotic subtext, too. Some day I will write a less bleak queer fix-it version of this for myself, but in the meanwhile, I can always watch "Put the Blame on Mame" on Youtube.

Sunset Boulevard (1950)

Summary: A screenwriter is hired to rework a faded silent film star's script, only to find himself developing a dangerous relationship.

Recommendation: Another classic for a reason. Norma's faded glory and desperation is fascinating to watch, as is Joe being drawn to her despite himself. Also inspired an okay musical with like three or four great songs.

Strangers on a Train (1951)

Summary: A psychotic socialite attempts to force an amateur tennis star to comply with his theory that two complete strangers can get away with reciprocal murders.

Recommendation: Hitchcock was a master of atmosphere, and this one's a prime example. The rising tension as the two go from a relatively normal interaction into something far darker and deadlier.

Dial M for Murder (1954)

Summary: A tennis player frames his unfaithful wife for first-degree murder after she inadvertently hinders his plan to kill her.

Recommendation: Okay, I don't know why tennis players keep getting involved in noir, but it's a good movie! I read that Hitchcock filmed this one almost entirely inside rather than allowing a lot of outdoor scenes, to give a sense of claustrophobia and it works.

Rear Window (1954)

Summary: A wheelchair-bound photographer spies on his neighbors from his apartment window and becomes convinced one of them has committed murder.

Recommendation: I love this one in spite of itself. I don't particularly like the main couple's dynamic in this, but I do love the glances into the lives of the people Jimmy Stewart's character is spying on, and the tension amps up wonderfully as the film progresses.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our ’Enry

WORDS BY LUKE G WILLIAMS

In an interview in 1977, the great Sir Henry Cooper remarked: “You only get out of life what you put into it. I earned my living as a boxer, but you can still conduct yourself in a gentlemanly way.”

These words serve as an apt introduction to a man whose fists may have wrought violence and destruction across 55 professional boxing contests, but whose geniality and warmth of personality endeared him to the nation.

Lambeth-born and Bellingham raised, Henry was that rare commodity – a boxer who was not only admired, but also genuinely loved. Across the 300 or more years that the sport of boxing has held a significant position within the collective British imagination, arguably no pugilist has been as widely and intensely loved as “our ’Enry”.

When he died on May 1, 2011 the country was deprived of one of its great post-war heroes – a man for whom the respected television commentator John Rawling coined the perfect epitaph: “He was a good boxer, but an outstanding man.”

The only boxer to ever be knighted – in recognition of his charitable work as much as his sporting prowess – Henry’s popularity traversed boundaries of class, age and gender.

To paraphrase Rudyard Kipling’s If, he was as comfortable displaying the “common touch”, pouring pints for punters at the Fellowship Inn in Bellingham, as he was “walking with kings” while dining at Buckingham Palace.

Henry was a staunch royalist – who had a portrait of the Queen Mother on his wall – and was at the same time suspicious of jingoism and avowedly opposed to racism in any form, as evidenced by his advocacy of the Anti- Nazi League, a group formed in 1977 to counter the rise of the far right.

Born in 1934, Henry and his identical twin brother George, as well as his older brother Bernard, were initially raised by parents Henry and Lily in Camberwell, but in 1939 they moved to a council house in Bellingham on Farmstead Road.

After brief spells in Sussex and Gloucestershire when they were evacuated – during which time their Bellingham home was hit by a German parachute mine – the Cooper brothers returned to south London in 1941.

Henry stayed on Farmstead Road with his parents until 1960, when he married his beloved Italian wife Albina. “It was a tight community,” he later said of his formative Bellingham years. “We all pulled together.”

Henry and George attended Athelney Road school and outside of school hours supported the family finances any way they could. Paper rounds, wood chopping and selling balls retrieved from the local golf course were among the innovative enterprises that put extra pennies in the collective kitty.

Henry and George’s entry into boxing came aged nine, courtesy of a neighbour who spotted their physical prowess and directed them to Bellingham Boxing Club.

Henry, naturally left-handed, nevertheless fought in the orthodox fashion and assembled an impressive amateur record for Eltham Boxing Club, winning 73 of 84 contests and competing at the 1952 Olympics.

Henry and George turned professional in 1954 under the management of the wily Jim Wicks. Although George would not ultimately match his brother’s fistic achievements, the two men were always extremely close.

“The only time we parted was when I got married,” Henry later recalled. “Even then, George came to live [with me] at Wembley until he was married.

“We went to school together, we went boxing together, we were together in the army. We look alike, we think alike, in temperament we’re similar and often we catch ourselves repeating each other’s remarks.”

Henry’s boxing career advanced quickly, and although he lost challenges for the Commonwealth, British and European titles in 1957, a famous victory against highly rated American Zora Folley the following year was the precursor to a points victory against British and Commonwealth champion Brian London at Earl’s Court in 1959.

Henry went on to successfully defend his British and Commonwealth titles on numerous occasions, earning a contest against one of the rising stars of world boxing in 1963 – a loudmouthed and undefeated 21-year-old American named Cassius Clay.

Rather than prepare for the fight in his usual environs of the Thomas A Becket pub on the Old Kent Road, Henry moved his training base to the Fellowship Inn in Bellingham, where the ballroom was converted into a makeshift gymnasium.

The influential American magazine Sports Illustrated reported: “For weeks he [Henry] lived at the Fellowship, taking his meals there, training in the back room when a wedding reception or tea party did not interfere.”

On an unforgettable night at Wembley Stadium, Henry’s preparations at the Fellowship almost paid off. His famed left hook smashed Clay to the canvas in the final seconds of round four – a moment that remains one of the most iconic in British boxing history.

For a few seconds a famous Cooper victory looked assured, but Clay recovered his footing – barely – and then in the interval before the following round his senses also returned, via a helping hand from some illegal smelling salts administered by his corner.

Henry was stopped while still on his feet in round five after suffering a terrible cut, with Clay labelling him “the toughest fighter I’ve ever met”. As for Henry, the magnanimous way he reacted to unfortunate defeat was typical of his generosity of spirit.

For the next few years he reigned supreme in Britain while Clay – who later renamed himself Muhammad Ali – went on to become champion of the world.

Ali granted Henry a rematch for the world title in 1966, in front of 46,000 fans at Arsenal’s Highbury stadium. Once again, Henry’s tendency to cut around the eyes proved his undoing as the referee stopped the fight in Ali’s favour in round six.

Henry subsequently added the European crown to his British and Commonwealth belts, before controversially losing all three titles in his final fight against Joe Bugner, a decision rendered by referee Harry Gibbs that was greeted with disbelief and catcalls by the fans.

In retirement, Henry, the first man to be twice named BBC Sports Personality of the Year, was much in demand as an after-dinner speaker, expert summariser and television personality – roles he fulfilled with distinction and integrity.

However, it was his more low profile – and unpaid – engagements at local boys’ clubs, sports clubs and boxing gyms that gave him the most pleasure.

When he died in 2011, a few days shy of his 77th birthday, old rival turned great friend Muhammad Ali was among those to pay tribute to a man whose prominence in British sporting folklore is assured.

“I am at a loss for words over the death of my friend, Henry Cooper,” Ali said. “Henry always had a smile for me; a warm and embracing smile. It was always a pleasure being in Henry’s company. I will miss my old friend. He was a great fighter and a gentleman.”

Above: Henry Cooper at the Fellowship Inn.

#lewisham#lewisham news#lewisham newspaper#london news#london newspaper#southeast london#catford#bellingham#deptford#blackheath#new cross#sydenham#telegraph hill#hither green#brockley#crofton park#forest hill#ladywell

0 notes

Text

An Introduction to Orson Welles - The (Belated) 2018 Director’s Marathon

Authors Note: The following novella-length essay on the history of Orson Welles was written to be the December 2018 Directors Marathon as is a tradition for this blog. It was submitted to Geeks Under Grace wherein it was rejected for its excessive length. After several months of consideration as to how to rework the piece into something publishable within the website’s requirements, it is being published now as was initially intended at the AntiSocialCritic Blog.

"I started at the top and I've been working my way down ever since."

- Orson Welles F for Fake

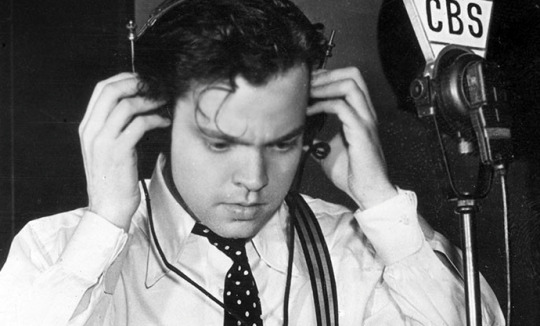

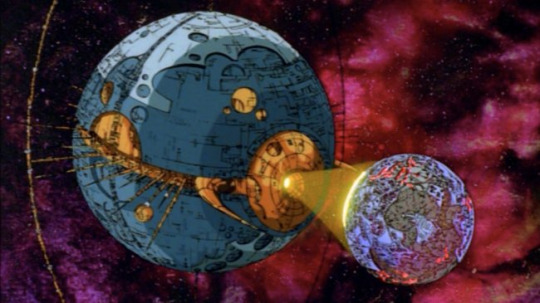

In the early morning of October 10, 1985, Orson Welles suffered a heart attack and died at his desk. He departed the world he had left such a massive impact upon as quietly and mundanely as a great man could. Just hours before the once superstar artist made his final public appearance on The Merv Griffon Show where he talked about his life. Prior to that in the weeks before he had starred in his final cinematic role while providing the voice of Unicron for Transformers: The Movie. His funeral was a quiet affair at a local hotel, surrounded by his surviving close friends and estranged family members from multiple marriages. You might view this humble affair and fail to understand that the man being eulogized was, in fact, one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. Across his massive career, Orson Welles became a pioneer of theater, radio, and film that pushed forward and challenged those art forms radically. He was intelligent, charismatic, well-read and alluring with an ability to command an audience through his words and presence. He was a showman, an actor as well as a magician but also a creative mind with a unique understanding and love for art.

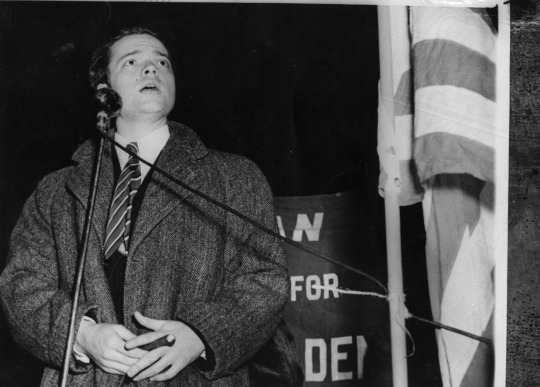

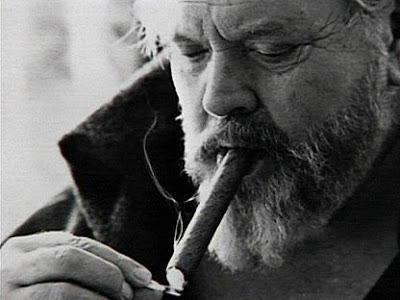

Yet for all of his creativity across a half-century of output he's almost entirely remembered solely for two major events early in his career. In 1938, he performed a radio rendition of H.G. Welles' War of the Worlds that supposedly ginned up a massive panic on the East Coast of the United States. Then in 1941, he directed Citizen Kane for RKO Radio Productions which would eventually go on to become the most acclaimed film in the history of cinema. As a result, his public image rapidly declined. He became recognized as a washed up, unreliable filmmaker with obesity problems and a bombastic personality. This version of Welles would become the stereotype so brutally mocked by comedians on television shows like The Simpsons, The Critic and Pinky and the Brain. Despite being pigeon-holed and written off within a decade of the peak of his career he continued to work as a filmmaker and an actor across North America and Europe for decades until his death. As excellent as his inaugural effort was his career has dozens of excellent films and performances that are well worth revisiting. Thankfully there has never been a better time to go back and review the works of Orson Welles than right now.

On November 2nd, 2018, Netflix published what will likely be the last of his posthumous works with The Other Side of the Wind. I reviewed the film for Geeks Under Grace at the time it released and have spent the last month reflecting on the experience of seeing such a culturally significant film. It's not every day that a lost piece of art is drudged up and rebuilt from the ground up. Beyond that, the film carries with it so many beautiful reflections, moments of brilliant and visual poetry. Knowing that it's the inheritor of such a vital legacy adds a great deal of weight to the film.

When I started writing publicly one of the first major article series I worked on was a project I called the Director Marathons. From 2014-2017 I did a yearly dive every December into the full filmography of a famous acclaimed director. Over the first four marathons, I dug through the collective works of Quentin Tarantino, Christopher Nolan, Guillermo Del Toro, and The Coen Brothers. I also did an additional six-month breakdown on the entire filmography of Steven Spielberg. Now that Geeks Under Grace is my home for writing I want to continue that tradition here. I considered several major filmmakers including Sam Raimi, John Carpenter, George Romero, and Martin Scorsese but with the release of The Other Side of the Wind, it became clear to me that no director more deserve the attention afforded by a total viewing of their body of work than Orson Welles.

What follows are a series of brief historical retrospectives and film analysis's meant to offer a brief look into the seventy-year life of the man of the hour. For every analysis I offer there is a greater and deeper discussion that every subject of his life I bring up can be made. In the name of brevity, I want this series to be largely introductory (12.5 thousand words of introduction...). The secret of great art is that there are always depths to be plumed within it, nuances to observe and details to be discussed. With Welles part of the appeal beyond his incredible eye for detail is his desire to push the boundaries of the art forms he tackled. Every project and chapter of his life could fill a thick book with all the details that go into them. Film improved as an art form because of his embrace of expressionism and innovative use of technology. Filmmakers as vital as Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese regularly host his works among the most influential and beloved of the movies that inspired theirs. There is so much immense history and artistry that can be delved into across the full career of Orson Welles.

That being said, as we learn in his inaugural film Citizen Kane, this can be something of a fruitless endeavor. You can never fully know the full life of a man based on what he leaves behind. Much like Charles Foster Kane's home Xanadu, his works stand as an eternal memorial to Welles' incredible creativity. Lost in the ruins of his career is the man that can only be remembered. These works aren't him. They're all we have left of him. There will never be a Rosebud moment where we understand the inner life of Orson Welles. Even so, the life of Welles is a grand one of ups and downs. In spite of the challenges, we shall do our best to look through the art to see the man.

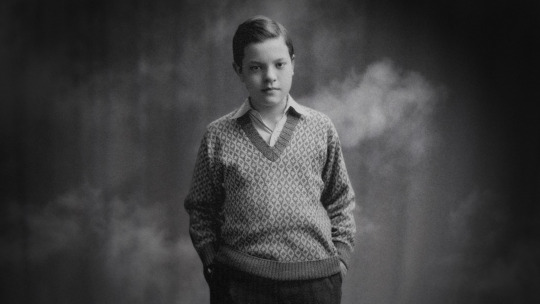

1. The Young Orson Welles

Orson Welles's early life was faced with much splendor and difficulty. Born to Richard and Beatrice Welles in Kenosha, Wisconsin on May 6, 1915, his family was at one point very affluent and wealthy as his father invented a bicycle lamp that allowed the family to move to Chicago. He eventually stopped working and subsumed to alcoholism. Richard and Beatrice would separate in 1919. Orson's mother found work at the Art Institute of Chicago as a pianist performing for lectures. On May 10, 1924, Beatrice would die of Hepatitis, leaving the nine-year-old Welles without a proper family.

Welles lived with his alcoholic father for three years, traveling the world and attending multiple schools. He would eventually settle himself at the Todd Seminary School for Boys in Woodstock, IL where he would set his roots. Later in this life, Welles revealed that Woodstock was the closest thing he had to a home. "Where is home?" Welles replied, "I suppose it's Woodstock, Illinois if it's anywhere. I went to school there for four years. If I try to think of a home, it's that."

The Todd School for Boys ended up being the catalyst for much of Welles intellectual development. His teachers fostered his fascination with acting and the arts and gave the incredibly intelligent young man free rein to expand himself. At age 15, Orson's father passed away from heart and kidney failure. Following High School, the young man found himself awash with opportunities including a scholarship to Harvard University which he declined. After a brief multi-week flirtation with the Art Institute of Chicago, the adventurous young Welles sought a life of travel.

2. Man of the Stage

Welles gallivanted across Europe using the remains of his inheritance. During a stay in Dublin, Ireland the young man approached the manager of the Gate Theater claiming he was a famous Broadway actor that ought to have a position on the stage. The manager didn't believe him yet gave him the job anyway based on his charisma and bravery. His stage debut was on October 13, 1931, in the role of Duke Karl Alexander of Wurttemberg in the play Jew Suss. He would act in several more Dublin productions including an adaptation of W. Somerset Maugham's The Circle at the Abbey Theater. He would try and seek further work in London but failed to acquire a work permit and thus returned to the United States.

Upon his return, Welles made his American debut as a man of the stage at the Woodstock Operahouse in Woodstock, IL. Welles immediately sought out his Irish compatriots from the Gate Theater to stage a drama festival in Woodstock consisting of Trilby, Hamlet, The Drunkard, and Tsar Paul. During this time he also got his first radio gig working on The American School of the Air and shot his first short film.

After marrying Chicago socialite Virginia Nicholas in 1934, Welles moved to New York City where he performed the role of Tybalt in an adaptation of Romeo and Juliet. On March 22, 1935, Orson made his radio premiere on the CBS Radio series The March of Time doing a scene from the 1935 Archibald MacLeish play Panic. Radio would become his primary income as the money he immediately started making with CBS was significant. Welles had moved to New York at the height of the Great Depression and ended up being in exactly the right place to benefit. The Federal Theater Project had been crafted by the Works Progress Administration as a method of helping to bring economic relief to struggling artists. Welles jumped on the opportunity and began funneling money from his incredibly lucrative $1,500/week Radio work into the theater project. President Roosevelt would quip that Orson Welles was the only person in history to illegally siphon money into a government project. The arrangement suited most everyone however and was looked the other way on. Famously Welles became so busy during this time in his life that he hired an ambulance to transport him back and forth across New York City at full speed between his radio performances and his theater directing jobs.

His first work became the incredibly famous and then wildly transgressive production of Voodoo Macbeth. The all-black production recast the traditionally Scottish play and set in against the backdrop of Haiti's court of King Henri Christophe. The production became a nationally recognized and hailed play that toured the country and skyrocketed Welles' name into the spotlight at the ripe age of twenty. The next several years of Welles life became dedicated to this grind of different theatrical productions and radio gigs, culminating his 1937 departure from the Federal Theater Project to create his own theatrical troupe. What would become known as the Mercury Theater opened on November 11, 1937, with an acclaimed restaging of Shakespeare's Julius Caesar set against the background of fascist Europe with himself in the role of Brutus. Here Welles would create many of the lasting relationships and raise multiple actors would follow him through his journey in Hollywood including Joseph Cotton, Everett Sloane and Vincent Price.

3. Voice on the Radio

Though famously a devotee of the Baird, Welles' recognition was earned by his incredible command of the airwaves. Welles' famous baritone voice became a regular mainstay across America as he became the regular voice for many of the country's most popular radio dramas of the time.

At the age of 21, Welles produced an acclaimed and often criticized version of Hamlet he did for the Colombia Workshop that shaved the four-hour play into a two-part 59-minute audio drama that cut the story of the Shakespearean tragedy to the bone. His presentation was noticeably more emotive than most presentations of Shakespeare at the time which set him apart. The bread and butter of his work throughout the 1930s was his work on pulps and radio dramas. Throughout 1937 over the course of a year, Welles provided the voice for the pulp icon The Shadow. At that point, the vigilante pulp hero in question was one of the largest entertainment properties of the time with novellas and regular radio dramas dedicated to him every week. Having Welles take up the mantle for a time put the fledgling star in the seat of a pop icon.

The moment that shot Welles into the spotlight came on October 30th, 1938 when Orson performed what would become the greatest media scandal of his career with the infamous War of the Worlds broadcast. The adaptation he conceived was fascinating. He took the broad events of H.G. Welles famous science fiction novel and interpreted them in the form of a series News broadcasts as though the events of the book were happening in rural New Jersey and New York City. The following events aren't clear. Welles himself inflated the reaction to the broadcast as though hundreds of screaming civilians scurried across New York City and attempted to flee head first into the Hudson River. More than likely the reaction caused nothing more than a minor stir compared to the massive nationwide reaction that the broadcast was implied to have caused. The broadcast itself did advertise itself on the pretense that it was a radio drama so any disturbed civilians would've tuned in later into the broadcast without the knowledge that it was a radio play. The incident was taken seriously by the United States government and Welles was forced to own up to the brief chaos. Next to his first film, this incident would become the most widely remembered moment of his career and one he took a perverse pride in. Beyond the angry government officials, it caught many an important eye of the day. Among the people who took interest in Welles were the producers at RKO Radio Productions in Hollywood.

4. Sought by Hollywood

Welles initially had no interest in film or Hollywood. Hollywood wanted Welles because he was an exploding star with exactly the sort of talents and celebrity that could transition into a film career. RKO Radio Pictures approached him with enormous monetary offers but the disinterested Welles was already wealthy. Money was no object to him. If he was going to be dragged into the film industry he was going to do it on his own terms. Thus he sent RKO an over the top ridiculous offer demanding full creative control over whatever he produced with them. To his surprise and the surprise of the enter Hollywood establishment, RKO accepted. He was offered a multi-picture deal with full creative control, upto and including hundreds of thousands of dollars to spend on each film and the right to reserve showing the picture to the studio executives until it was completed.

This has to understood in context. The late 1930s was the height of the studio system in Hollywood. Filmmakers worked at the behest of cutthroat corporate masters who had the right and gumption to control every facet of a film. They frequently re-shot segments from acclaimed films before they're released on a whim based on what they thought worked/didn't work/was marketable by their standards. Even industry greats like John Ford and Frank Capra didn't get to control this much of their films. Given that creatives had so many restrictions the results were stunning. This was the moment in cinematic history when films like Casablanca, The Wizard of Oz and Gone With the Wind were emerging and defining the Golden Age of Hollywood as a time when storytelling and craft were at their creative peaks. For Welles to gallivant into Hollywood and take over the town single-handedly was unheard of. To paraphrase Welles, he had been given the greatest train set a kid ever received and he was looking to use it.

Without knowledge of what he was even doing Welles immediately turned to the greats of the industry of the time to start building his team. His two most important collaborators would be screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz and cinematography Gregg Toland. Mankiewicz was a veteran screenwriter who had had his hand in writing and producing dozens of films since 1926. Toland was fresh off of working on multiple critically acclaimed films like The Long Voyage Home and The Grapes of Wrath, both of which he shot with John Ford.

Welles had the best talent Hollywood had to offer at his fingertips and near infinite power to do as he pleased and began working on different pitches for ideas for his first film. The first idea he conceived was ultimately too ambitious to achieve. He considered shooting an adaptation of Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness done in the first person perspective. The project ultimately fell apart as Welles eventually couldn't make his vision work on RKO's budget. Decades later there was a proper if highly altered adaptation of the book with Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now.

Heart of Darkness would be the first of three pitches Welles initially made to RKO to fill his two film contract. His second idea was a political thriller/comedy called The Smiler With a Knife based on a novel by Cecil Day-Lewis. This project stalled by December of 1939. Welles was uncertain of a plan and didn't want to drag starting production on something indefinitely. He was already behind schedule. Welles and Mankiewicz began brainstorming and eventually, the two started on an idea for a film titled American. Welles approached Mankiewicz during the writing to find that the script he'd written out was hundreds of pages of messy but serviceable ideas. Taking his excellent ability to cut down stories to the bone that he had used on Hamlet, Orson crafted what would come to be known as his first masterpiece Citizen Kane.

5. Citizen Kane (1941)

I recently did a full-length breakdown of Citizen Kane for Geeks Under Grace and don't wish to relitigate much of what I produced for that article here. What I do think is necessary is understanding how the world reacted to and would ultimately go onto understand the film.

The reaction to the film was both immediate and faltering. The film was met initially by mixed reviews that sited the film's awkward structure as a fault. It wouldn't be years before the film would be released after it's initial run that the film would be subsequently analyzed and relitigated as one of the greatest films of all time.

Well before it's release, the film's satirical target William Randolph Hearst heard the wind that the film was a rather overt critique of his person and attempted to buy the film outright from RKO Radio Pictures to prevent it from seeing the light of day. When that didn't work, he turned to his newspaper network which proceeded to lambast the film in the public eye. The film's release was delayed and by the time it released to the public the reaction was nothing more than a whimper. Citizen Kane bombed in the box office.

The half-century of after it's release brought much rabid discussion and reevaluation of the film into mainstream discussion. In a famed piece of now hotly disregarded film criticism, New Yorker Film Critic Paeline Kael wrote Raising Kane. The essay lambasted Orson Welles, the film in question and called into question the very authorship of the film, claiming that screenwriter Herman Manchowitz deserved more credit for his role in writing the film.

Mind you Pauline Kael's criticism wasn't totally irrational. Kael is one of the most influential critics in history and tends only to be remembered nowadays by her gaffs like her public disdain for Clint Eastwood films like Dirty Harry. Her coming out against Orson Welles is remembered as an enormous artistic mistake on her part but people take the book-length essay she wrote very seriously. As a point, it's worth noting that Welles fundamentally agreed with her on many points. He felt that the director was an overrated position in filmmaking and that film was a collaborative process between the writers, actors and crew that the direct guided and oversaw. Even so, it's not surprising one of the antagonist characters in The Other Side of the Wind was a female film critic.

The most cynical read on Citizen Kane is that it's the film that introduced the concept of ceilings to the cinema. Prior to Citizen Kane, most film productions didn’t film ceilings because they needed open air sets to fit audio equipment. Many proclaimed fans of the film tend to adore it's superficiality more than it's actual storytelling chops as a film. As it stands the most remembered aspect of the film is the Rosebud twist at the end that Welles himself considered as gimmicky. Welles himself had a very conflicted relationship with the film. Welles disliked some of the films minor mistakes and ultimately came to consider the film a curse on his career that he could never live up to. How can anyone build a career off of an instant masterpiece? Even the man who made Citizen Kane couldn't manage to answer that question.

Yet in 1982, Steven Spielberg paid $55,000 for one of the surviving Sled props. Every filmmaker from Martin Scorsese, to Richard Linklater, to Tim Burton, to George Lucas and the aforementioned Steven Spielberg has sited Citizen Kane not only as one of their favorite films but as their inspiration for much of their work. In addition to most every respected film critic from Roger Ebert to Jonathon Rosenbaum has offered their endorsement of the film's strengths. Its legacy is undeniable. Is it overrated? Perhaps. While it's placement in the canon of Orson Welles is certainly hotly debated, there is no denying that Welles began his filmmaking career with a masterpiece for the history books.

6. The Magnificent Ambersons (1942)

There is a scene in Richard Linklater's Me and Orson Welles where the titular character and his apprenticing young actor Zac Effron that the Welles family was once close to Booth Tarkington. Though not widely remembered today, Tarkington would've been a huge deal to people at the time much how writers like Cormac McCarthy and David Foster Wallace are lionized today. His masterpiece The Magnificent Ambersons would go on to be the subject of Welles’ second major film for RKO.

As Welles continued his work after the debacle of Citizen Kane's release he quickly moved on to fulfill the second film in his RKO contract. His team continued to dig through numerous options and ideas. The most notable idea he didn't end up going with was a pitch for an adaptation of the Bible called The Life of Christ which would've been a strictly adhered adaptation that ultimately fell through twice. Instead, Welles turned to the contemporary masterpiece that was close to his heart. Welles' initial cut of The Magnificent Ambersons is said to have been a masterpiece that rivaled Citizen Kane in quality. He translated the sad story of an old American family's decline into poverty and irrelevance to the cinema and delivered the second masterpiece RKO paid him to. Unfortunately for Welles, it wasn't the masterpiece RKO wanted. The studio shuttered at the bleak film Welles had produced and quickly began underhanded plans to change the film.

Welles was shipped off to Brazil as part of a US Government deal with their government. He was to shoot his third feature for RKO called It's All True which would've involved documentary footage from various festivals and events. While he was out of the country, RKO pulled all of the actors and crew back to the studio lot, cut out the third act of the film and reshot it with a happy ending that completely changed the story of The Magnificent Ambersons. Several cast and crew attempted to warn Welles but he didn't find out until it was too late. By the time he was back in Hollywood, he would lose his rights to change the film. Late in his life, Welles would find himself watching the theatrical cut of The Magnificent Ambersons late one night on television. His then mistress Oja Kodar recalled the experience of nearly walking into the room and catching a reflection of the late 60s Welles sobbing as the movie that clearly meant the most to him was presented on late night television. While the cut we have today is largely excellent, it's far from the vision that Welles had intended for it.

7. Fired from RKO

Welles had already been fired from RKO Radio Productions by the time he returned from Brazil. The studio that had once promised him free reign to produce masterpieces for them didn't like the controversy associated with his films and couldn't figure out how to market what he did film. For them, it was smarter to go into damage control mode and boot out the wunderkind to the streets. The cut of Magnificent Ambersons with the happy ending they did produce didn't do well in theaters and the preferred cut of the film was eventually destroyed. Thus began the air of bad luck that would surround Orson Welles' prolific career. Despite churning out two masterpieces, Hollywood now hated him. As time would go on he would become more and more of a pariah in filmmaking circles.

His last film for RKO which he was producing and directed several scenes for Journey into Fear ultimately saw him being stricken from the credits. His co-director Norman Foster would receive directing credit but later Welles scholars have often retroactively credited Welles as a director too. Welles immediately began damage control for his reputation by prostrating himself over the next several film projects he produced. He started taking acting jobs for films starting with an adaptation of Jane Eyre to try and repair his public image. Interestingly enough the latter film would end up being one of his only romantic performances as that film had been produced to capitalize off of the recent success of historical romances like Gone With The Wind.

8. The Stranger (1946)

Welles needed to jump back into Hollywood and prove that he was capable of producing something normal that he could sell. With that in mind, he conceived of The Stranger. The film would go on to be his least artistic and therefore most financially successful film. It had been four years since he'd been in the directing chair and he was desperate. He was approached by producer Sam Spiegel after director John Huston couldn't take the job. The result is easily the most Hollywoodish film of his filmography and the one that really represents the director at his most obedient. Despite the darker story, that being about a Nazi holocaust perpetuated being hunted by an investigator portrayed by Edward G. Robinson, the movie was a great deal less artistic and revolutionary by the standards of the time. It was merely a conventional noir thriller. To paraphrase Welles, he did the film with much stricter regulations as a means of proving to Hollywood that he wasn't a toxic director and that he could make money. While the film wouldn't succeed in fixing his reputation it at least made him slightly less toxic. Unfortunately, the film wouldn't lead to any additional career help for Orson. He originally signed with International Pictures to do a four-picture deal after the film as complete. The company backed out of the deal the just weeks after the premiere when it looked initially like the film wouldn't make it's money back.

9. The Lady from Shanghai (1947)

The life of Orson Welles has often been described as an illusion, an incestuous juggle between fact and fiction that the ever impressive Welles maintained as a kind false mysticism to increase his legend. While it did give his persona a larger than life appearance it's made tracking the history of Welles into a nightmare. This can be clearly seen in the case of Welles' third masterpiece The Lady from Shanghai. He's told the story of how he pitched the film to Hollywood producer Harry Cohn of Colombia Pictures. After his recent failures Welles turned back to his previous loves of radio and theater and began producing new shows and dramas. His biggest stage production at that point was a play version of Around the World in 80 Days which closed almost immediately within weeks after opening.

Supposedly, as the production was preparing for it's Boston premiere, Welles found himself strapped for cash and in desperate need for $50,000 to move the costumes from the train station to the theater. Desperately he pitched a fake book to the president of Colombia Pictures using the name of a paperback book a young woman was reading next to him, got the money, performed the show and then went back to Hollywood to write and direct the film. It's a great story but it likely isn't true. Whatever truth is in it is questionable as he's told different versions of the same story to different interviewers, each with a different amount of money and circumstance. It's likely that Welles just got called out of the blue by Harry Cohn to direct a thriller and he took the gig. Naturally of course half of the appeal of Orson Welles is the blur of fiction and reality the surrounds the myth of his life. It's fun to speculate but having a historically accurate read of Welles' history is a frustrating knot to untie for scholars.

That film he produced The Lady From Shanghai would become one of his most respected films and widely regarded as one of the weirdest movies. That's not hyperbole either as David Kehr of the Chicago Reader was quoted as saying it was one of the "weirdest great movies ever made". While more conventional by the standards of his previous two masterpieces, The Lady from Shanghai is far from your run of the mill Noir thriller. Welles had initially shot the film in the style of a documentary. That's a strange choice but it grounds the otherwise outlandish story of a sailor being asked to help fake the death of a wealthy man in a kind of distant visual style. Harry Cohn hated the result. Like his previous two films, large segments of the film were reshot to add traditional close-ups and conventional shooting. These shots clashed with the film's already strange visual style and made the film more surrealistic than it already was. The film's most notable contribution to cinema, of course, was the finale in the mirror maze. Without spoiling the story context, the final shootout is mesmerizing and visually bizarre and left an imprint on generations of filmmakers. The trope has returned in numerous forms from action films like Enter the Dragon and John Wick 2 to comics like The Dark Knight Returns. Yet again though, the film flopped in the box office.

As a quick aside, the film also stars his then second wife Rita Haworth with whom he divorced shortly after the film completed production.

10. Macbeth (1948)

It's strange that Welles' first attempt at a Shakespearian film would come about in such a modest fashion yet his selection wasn't surprising. Being that Voodoo Macbeth was the stage play that put his name on the map, a traditional Scottish production on film made sense to be his Shakespeare film.

Republic Pictures at the time was a subpar studio by the standards of the Big Three. It mostly produced B-Pictures and serials. For Herbert Yates, as the president of the studio, Welles' pitch for a Shakespeare adaption gave him high hopes that he might be able to make his fledgling Hollywood operation into a prestige studio with the right success and went all in on the idea. Welles produced the film on cheap sets and finished the film in just 19 days of production with two additional days of pick up shots. Yet despite being rushed and inexpensive, the film managed to produce something qualifying as a definitive vision of one of Shakespeare's most famous tragedies. That speaks highly of the production given that the play has been adapted dozens of times in cinematic history including versions by Roman Polanski, Akira Kurosawa and most recently Justin Kurzel. Yet Welles' film was benefitted by Welles' unique expressionist take on filmmaking. The cheap stagey sets were masked in beautiful black and white film stock, lit with precision to highlight it's character's emotional state and performed to perfection with Welles in the central role.

Welles had bet that the film would go a long way to repairing his reputation and unfortunately this wouldn't help it. The film was savaged by American critics who despised the over-the-top Scottish accents in the initial release. Welles rerecorded the dialog with American accents for a 1950 rerelease but that version didn't do well either. Both versions were flops and outside of Europe where the critics appreciated it more, there wasn't much support for it. It didn't help that the film was released in close proximity to Laurence Olivier's acclaimed Hamlet which became one of the most celebrated Shakespeare adaptations of all time. It would take years for critics to start appreciating its strengths.

11. The Third Man (1949)

Of all of the films in the Welles filmography, maybe none is more vital to understanding the Celebrity of Orson Welles than The Third Man. Like Jane Eyre, this wasn't a film that he produced or directed in so much as he is remembered for his excellent performance. At that, he's barely in the film at all. The leading man is his frequent collaborator Joseph Cotton. The film was directed by legendary director Carol Reed, famous for films like Odd Man Out, Night Train to Munich, The Fallen Idol, and Oliver! While somewhat obscure now, the director became famous for being one of the most skilled directors in British history. In addition, the film was produced by legendary golden age producer David O'Selznick (Gone With the Wind, King Kong). Welles was asked to play the role of Harry Lime in the film and was offered one of two options for payment for a small role. He had the option of reviewing a portion of the film's profits down the line or a lump sum of money immediately. In a moment of deprivation, he jumped on the money immediately in a financial decision he would come to regret. The Third Man would go on to become the most financially successful film he was ever associated with. Had he chosen profit sharing he would've become immensely wealthy as the film in question has remained one of the most popular noir thrillers of all time.

Welles would later go on to express his opinion that his performance was the greatest "Star" role an actor could've ever asked for. Harry Lime is mentioned dozens of times in the film prior to his first appearance so when Orson Welles finally makes his surprise splash of an appearance the film there is a great deal of weight to his screen presence. His few scenes in the film and his improvised line are usually sighted as the high points of an otherwise widely regarded film. In some ways, this is sadly prophetic of much of the way culture remembers Orson Welles. People think of him as a flash in the pan and we see this in the way culture idealizes individual moments from his films as opposed to his films overall. Most people don't remember the side characters in Citizen Kane but they remember Rosebud. The same is true of The Third Man. People remember Welles' few scenes but they frequently forget Joseph Cotton and Carol Reed's accomplishments with the film outside of Welles. The mere size of his personality creates expectations. First-time viewers familiar with Welles might be surprised to notice he doesn't appear until well after the first hour of the film. Welles is just one turning gear in a much larger story about post-war corruption and profiteering set against the hurt and ruin of Vienna, Austria. His chemistry with Joseph Cotton adds an air of history two the two characters whose lives were once tied together being torn apart by circumstance. His deep baritone voice exudes an air of malevolence as he stares contemptuously on the small people below him. It's a small but vital performance built up to by one of the greatest thriller stories of all time.

12. Othello (1951)

No film would come to break Orson Welles' reputation more than Othello. Despite earning the Grand Prix du Festival International du Film at the 1952 Cannes Film Festival, Othello would become a curse on his reputation that he would never overcome. Welles had conceived of doing an adaptation of Shakespeare's Othello prior to Macbeth but ultimately chose to go with that play when the concept seemed unfeasible. Welles was approached by an Italian film production company to star and direct a film version of the famed play based on his recent theatrical work which the production company thought would translate over well into the stage play. Welles quickly got to work assembling a team of European filmmakers and actors that he took to Italy. The production was immediately stymied by the surprise Bankruptcy of the production company meaning that the subsequent three years of production necessary to get the film finished had to be self-financed. Though not Orson's fault as the factors were out of his control, this would prove to be the final nail in the coffin of his public reputation. The fact that the film took three years to finish and went over budget put a stigma on his name that he never escaped.

The result was a convoluted production shot across multiple countries including Spain, Italy, Morocco and Turkey that created a mismatched pan-Mediterranean look to the film. The final cut was an atmospheric masterpiece. Welles scholar Jonathon Rosenbaum described the tone as almost that of a horror film more than anything else. There's is an immense dread hanging over the film as we see the unfolding story of interracial love and racial bigotry play out against the backdrop of war and political strife. While a clean cut is available today thanks to the Criterion Collection, early distribution of the film didn't go well. The film received several cuts in different countries and many of the versions distributed had massive audio problems including audio drops and syncing issues. The film was also distributed with multiple soundtracks. Once again the hard work that went into an Orson Welles film was lost to circumstance and failed to materialize until much later.

13. King Lear (1953)

In the second of Welles' exoduses to Europe, the director fled the United States for England following the McCarthy hearings and as a result put him on bad terms with the IRS. Orson Welles wasn't a communist but he was a Roosevelt Progressive democrat and disliked the air of paranoia in the United States during the Cold War. Welles was asked to perform the titular role in a CBS Omnibus production of King Lear for television in 1953 which he accepted the role of. The television film was a severely truncated 73-minute version of the play with most of the subplots and extraneous stories outside of the main plot cut out to focus on the main character's descent into madness. Though cheaply produced for television, his performance as Lear is the standout of the film. While he was in the United States to film the production, he was escorted every by the IRS who confiscated his earnings from the production to pay off outstanding taxes being sent back to England.

14. Mr. Arkadin (1955)

After the immense success of The Third Man, the movie that had taken Hollywood by storm became a hot ticket item and it's producers wanted to franchise it. Thus in 1951 was born The Lives of Harry Lime. The radio drama starred Welles in his most popular and deplorable character over the course of 52 episodes that represented a prequel to the film. Welles himself was involved in the process of developing the series given that the character was so directly tied to him. This included an episode called The Man of Mystery. This episode would go on to become the primary influence of Welles' newest thriller.

Though lower in budget, Mr. Arkadin was ambitious in its scope. The thriller sought to be a massive thriller set across multiple countries where the stakes of the questions it raised could change the fate of nations. In terms of story, this thriller was one of his most grand and globe-trotting adventures. Mr. Arkadin is a veritable tour de force of settings and European cultures.

Whereas Othello was shot over multiple countries meant to portray the same place, Mr. Arkadin was set across multiple countries in Europe and portrayed the variant beauty of many of it's finest interior sets. Cramped as much of the film looks from a visual standpoint the film did tour Europe across the scope of its production from London, Munich, to multiple places in France and to Switzerland. The story's central mystery involving the investigation of a man with no memory of his past can be difficult to follow but builts to an excellent final race wherein the lead character and the titular Mr. Arkadin must race to Spain to find the same person before the other.