#1870's

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Dress by Mme. Martin Decalf, 1878-80

From the Metropolitan Museum of Art

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Wallpaper frieze, late 19th to early 20th century, by Walter Crane.

Wallpaper frieze, 1879, by Bruce James Talbert.

c. 1875, artist unknown.

1877, Walter Crane.

1877, Walter Crane.

c. 1875, Walter Crane.

c. 1875, Walter Crane.

Late 19th century, Bruce James Talbert.

c. 1875-1910, Walter Crane.

c. 1875-1910, Walter Crane.

c. 1875-1910, Walter Crane.

Wallpaper, c. 1875, Walter Crane.

c. 1875, Walter Crane.

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carlo Naya • Night View of the Grand Canal, Venice, 1875

Naya operated a commercial photography studio in Venice specializing in Romantic moonlit views of architectural landmarks and vistas. Because emulsions were not sensitive enough to record images at night, he made photographs during the day, then created the illusion of moonlight through a variety of darkroom tricks.

In this day-for-night image, the sun masquerades as a gently glowing moon and hand-painted highlights glitter on the water and cathedral domes.

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

A couple victorian ladies for the first batch of commissions

commission info

#commissions#illustration#ink#victorian#watercolor#1870's#buyer requested to stay anonymous which is totally fine

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paris Commune, 1871.

Presentation of some social measures

The central committee of the National Guard, which had held power in Paris since March 18, 1871, encouraged voters to vote for a municipal assembly and to appoint "men who will serve you best" and who were "among you, living your own life, suffering from the same ills." After five months of siege, the Paris proletariat had "consumed more alcohol than bread" (P.H. Zaidman). Workers accustomed to living from day to day were not paid and did not expect to find work for a long time. A decree of February 15 restricted the allowance of 1.50 francs per day to only the National Guards who justified their lack of work. This pay was for most people their daily bread, and it was forbidden to take off their uniform (which was useful for their survival and that of their family). Craftsmen and merchants are pressed by the deadlines, the deadlines of which (which were increased by the government of September 4, but remained insufficient) are reduced by the Versailles Assembly (elected on February 8, 1871). Craftsmen and merchants are ruined by the cessation of transactions in the city deserted by those who were able to take refuge outside. All those who have no savings and who are without resources show concern for the payment of their rent. Small rentiers and liberal professions, just like the proletariat of Paris, are helpless and preoccupied by daily supplies.

The assembly of the Commune, elected on March 26, 1871, obliged to simultaneously fulfill the functions of government and municipality, composed of men with different political positions, subjected to different external pressures (clubs, district assemblies, circles of national guards), militarily assailed by the Versailles reaction, had very little time to pursue a social policy satisfactory to the majority of those who designated it.

First, it was a question of solving the problem of rents.

In September 1870, the government of National Defense had to find the means to continue the war. Since many republicans lived in the memory of 1789, in particular of the declaration of the fatherland in danger, they were inspired by it to help the destitute defenders. Thus was born the idea of exempting tenants from paying their rent for the duration of the conflict: this measure is called "moratorium of rents". The decree of September 30, 1870 granted a three-month period to tenants to pay their term due on October 1. As the siege of Paris and the protests continued, the decree was renewed on January 3, 1871. In November 1870, elections for the mayoralties of the twenty arrondissements, organized following popular demonstrations, had been won in nine of them by radical republicans. In the neighborhoods, committees composed of elected delegates were also formed. They formed a Republican Central Committee opposed to the government. A new period was thus granted to needy tenants.

For the Versailles Assembly, the measure threatened property and social order. The Versailles Assembly never stopped questioning these measures. At the beginning of March, the question of the April "term" began to arise. According to the Proudhonists, the very principle of paying rent was being called into question. For the defenders of social order, it was necessary to assert the right to property. On March 10, 1871, Thiers repealed the rent moratorium in place since September 1870. Parisian tenants, the majority in Paris, could not submit to this brutal decision.

After March 18, according to the majority of deputies, it was urgent to abolish the rent moratorium. In addition, other cities "threatened" to form revolutionary communes.

Discussions on the rent problem began on March 28, before the establishment of the nine commissions responsible for its management. The Labor, Industry and Trade Commission, as well as the Finance Commission, took charge of the rent issue. Eugène Varlin and Adolphe-Alphonse Assi presented a draft decree on rents; This is a matter of taking an emergency social measure (two days to prepare the decree)! However, Danielle Voldman points out that Varlin and Assi underestimated the difficulties of implementing the decree. In any case, the decree was adopted on March 30. "Considering that work, industry and commerce have borne all the burdens of the war, it is only fair that property should make its share of sacrifices to the country" (Journal Officiel, March 30, 1871).

Tenants were given the terms of October, January and April; any payments made were to be applied to debts falling due. Debts for furnished tenancies were forgiven, tenants were granted the right to terminate their leases for six months, or to protect the notice given for three months. The workers and petty bourgeois tenants were quick to make use of this decree; when the concierges opposed their departure, they moved out with the help of the National Guards. The sums already paid were considered as advances on future terms. The remission also applied to small furnished dwellings (the “garnis”). When leases were terminated, the tenants’ voice took precedence over those of the owners. Finally, tenants who were dismissed could stay for six more months. From the point of view of the working classes, this was the assurance of not finding themselves on the street for several months. Thiers tried to respond to the decree. Of course, the main thing for Thiers was to maintain "social peace"! Most of the deputies refused to let the owners lose their income. A few argued for an "appeasement law". Since the district town halls could not cope with the influx of requests for help, the Commune proposed to requisition the apartments abandoned since March 18 by those who had fled Paris. These requisitions were to be made with an inventory of the premises and a copy to the representatives of the absent owners. It is possible that the requisitions were blown out of proportion by some dispossessed owners, and that the lack of documentation concerning these requisitions reveals their small extent more than the destruction of the archives in the fire at the Hôtel de Ville.

Concerning the question of deadlines, from April 1, the Commune encouraged workers' societies and trade unions to send it all the necessary information. Charles Beslay, elected to the Council of the Commune, presented his project (published in the Official Journal). After serious discussions, a decree of April 12 provided for the suspension of proceedings until the publication of the decree on this question. The repayment of debts (of all kinds) falling due should have been made within the following three years (unfortunately, this did not happen as planned!).

The arbitration commissions, composed of two tenants and two owners chosen by the judge, could grant debtors a period of two years to pay the rent arrears without interest as well as a spreading of the debt, over the year by twelfths. After two years, a period was still possible, this time with 5% interest. The tenant had to prove that the "events" occurring between September and May had prevented him from paying his rent and that he was "in good faith". The arbitration commissions continued the work of the municipal commissions and took over the procedures initiated since the winter with the justices of the peace by owners contesting the validity of their tenants’ requests. Until May 28, 1871, the functioning of these commissions was slow; the owners waited to see how the situation would evolve, not caring about appearing to be members of the “starving” party. On the other hand, at the beginning of May, mention was found of the first requests from tenants. At the end of the Bloody Week, the requests exploded.

It must be admitted that these measures were not enough to get the people of Paris out of the precarious situation in which they found themselves...

On March 29, a decree, proposed by Augustin Avrial (at the Commission of Labor and Exchange), suspended the sale of the deposited objects, but this proved insufficient. The debates never ended! On May 3, Arthur Arnould insisted on continuing the discussion launched by Augustin Avrial. On May 6, François Jourde (Finance Commission) voted on a project which, while compensating the administration of the Mont-de-Piété, authorized the free withdrawal, from May 12, of all recognitions prior to April 25 that carried a commitment of up to 20 francs (clothing, linen, furniture, work instruments, etc.). Since the operation was to involve at least 1,800,000 items, these items were divided into 48 series to be drawn at random. This policy of "relief" should have been supplemented by the use of public resources, such as public assistance (but which was disorganized and deserted by almost all of the employees who came out of it).

At an extraordinary council of hospitals held on March 20, the Parisian administration of the Assistance publique decided to continue to exercise its functions despite the events of March 18. On March 22, the Director was forced to leave Paris, soon followed by the division heads, which led to profound disorganization. Appointed head of the Assistance publique on March 26, Camille Treillard set about making the institution function as best he could, under the control of the Central Committee of the twenty arrondissements, then under the control of Gustave Tridon, charged by the Commune with following this file. In early April, the influx of wounded implied the need to increase the number of hospital beds. The Assistance publique had to face the innumerable problems posed by the necessary reorganization. Their professional ethics pushed most of the doctors to remain at their posts, while they were generally indifferent or hostile to the Commune. The same thing happened to the 2,350 lay staff members, who were generally better disposed towards the fédérés. Camille Treillard, a deeply honest and scrupulous man, was concerned above all with ensuring the proper functioning of the public hospital system, specifying the priorities: "The political spirit must be banished from the hospital, to allow only the spirit of devotion and solidarity to reign". Treillard did his best to resolve the problems of supplies, the provision of bandages, and also to resolve the problems of financing (the "treasure" of the Assistance publique had been put in a safe place by the Versailles troops). Despite the relative isolation in which each hospital was forced to operate, the health system managed to fulfill its mission in a generally satisfactory manner thanks to its staff. Camille Treillard was able to face the dramatic situation resulting from the Semaine sanglante with courage, and refused to hand over the wounded fédérés to the Versailles troops. During the Bloody Week, the Versailles troops did not hesitate to shoot several doctors.

Two commissions have a significant impact on the economic and social life of the people of Paris, and reveal, through their actions, all that the Commune contains of socialist.

The Subsistence Commission, led by François Parisel and then Auguste Viard, aimed to ensure the supply of Paris and the lowering of prices, compromised by certain unscrupulous officials (such as the inspector of markets and halls who hid part of the flour stock). From April 25, the exit of transit goods was authorized, except for foodstuffs and munitions. The Prussian blockade, the suppression of correspondence with the departments, the ban on water convoys decided by Versailles, did not prevent the supply of the market by the neutral zone, and prices were falling (except for the price of meat). On April 30, salt was offered to bakers, for humanitarian purposes. The Subsistence Commission decided to purchase foodstuffs to sell them at cost price through establishments placed under the guarantee of the municipalities. From May 6, the Commission checked the flow of meat at the free butcher's market of Les Halles and in the butcher's shops of Montmartre.

The Commission of Labor, Industry and Exchanges: First under the impetus of an initiative commission established on April 5, then under the impetus of Léo Frankel, the Commission of Labor, Industry and Exchanges, obviously intended to respond to the satisfaction of workers' interests. A decree of April 16 asked the workers' union chambers to set up a commission of inquiry that would serve to draw up statistics on abandoned workshops and an inventory of work tools, to present a report on the practical conditions for quickly putting these workshops back into operation by the cooperative association of workers and employees, to draw up a draft constitution of these workers' cooperative societies. The decree also provided for the payment of compensation to be paid to the employers upon their return. A room was made available to the union chambers at the Ministry of Public Works and the unions began to work by appointing their delegates. The commission of inquiry held two sessions on May 10 and 18, but could only limit itself to preliminary studies, the Versailles repression not allowing it to go further...

Thanks to Léo Frankel, the Executive Commission banned night work for bakery workers (April 20). The decree was gratefully received by the bakery workers who demonstrated in its favor on May 16. A more general measure was taken on April 27, prohibiting fines and deductions from wages in public and private administrations and restoring those that had been deducted since March 18. A special circumstance forced the Commune to go further. On May 4, Edmond Evette and Lazare Lévy were tasked with monitoring the production of military clothing. Their report noted that the auction price had led to a drop in wages. The Commune paid 2.5% less for its supplies than the government of September 4. Léo Frankel and Benoît Malon concluded that it was necessary to resort to workers' corporations. On May 12, the Commission of Labor, Industry and Trade was authorized to revise the contracts concluded to date, to give preference to workers' associations, according to specifications determined by the intendance, the union chambers and a delegate of the Commission, and set the minimum wage for work by the day or in its own way. On May 14, François Parisel, head of the scientific delegation, called on unemployed workers to work on paper. Léo Frankel, for his part, wanted to limit the working day to eight hours; however, several workshop regulations set it at ten hours. In these workshops, the director, the workshop manager and the bench managers were appointed by the workers who had daily means of action on management.

Despite the decrease in the number of employed workers (which went from 600,000 in 1870 to 114,000), the war, and the economic situation, union and corporate life managed to develop.

From March 23, the trade union chamber of stone cutters and sawyers decided to organize relief in the event of injuries or accidents. On April 27, the tallow smelters and iron smelters joined together to form a trade union chamber and a cooperative association. The butcher workers wanted to organize a trade union chamber that would be necessary to eliminate employer exploitation. It should be noted that historians list the action of 43 production associations, 34 trade union chambers, 7 food companies and 4 groups of the Marmite (food cooperative founded in 1868 by Eugène Varlin and attached to the International).

The women workers also tried to follow the action undertaken by their male comrades. The Central Committee of the Union of Women for the Defense of Paris and the Care of the Wounded, charged by the Labor, Industry and Trade Commission with the organization of women's work, convenes (on May 10) a meeting at the Bourse to appoint delegates in each corporation. It is also a question of forming union chambers, cooperative workshops, and a federal chamber. Another meeting was planned (on May 21) to set up chambers, but it never took place...

Overall, during these 72 days, the Commune could have done more in the social domain, to satisfy all those who brought it to power and who hoped to see social improvements. Nevertheless, one must take into account the political divisions (neo-Jacobins, Blanquists, auto-authoritarians), with the heavy task of governmental and municipal reorganization to assume. Thus, the Commune had to bear the weight of a two-month war against the Versailles army. It must be acknowledged that the Commune outlined what a truly socialist policy would be, which it would be up to future generations to implement...

Sources :

Michel Cordillot, Danielle Voldman, Pierre-Henri Zaidman - La Commune de 1871 : Les acteurs, l'événement, les lieux Laure Godineau - La Commune de Paris par ceux qui l'ont vécue Jacques Rougerie, La Commune de Paris Jacques Rougerie, Paris libre 1871

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

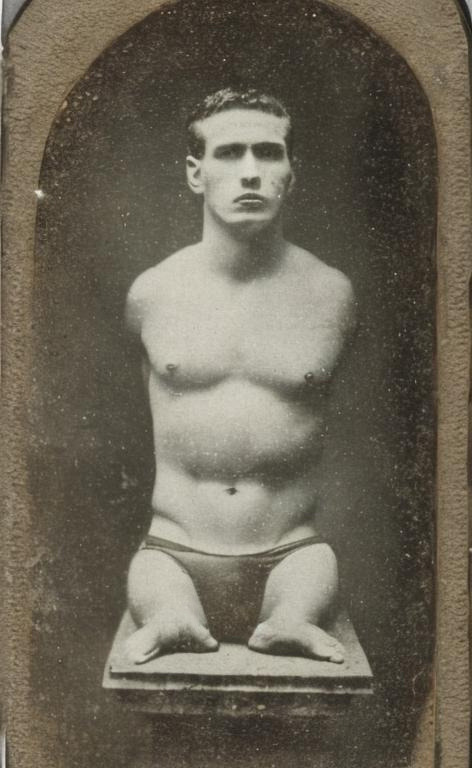

an undated photograph of a congenital quad amputee man who appears to be sitting on a platform or pedestal. he has short legs with asymmetrical deformed feet. possibly from the 1870's.

#ai photography#male#man#quadruple amputee#quad amputee#amputee#phocomelia#congenital amputee#1870's

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Once upon a time, I drew a picture of what I imagined Rick looked like in the 1970's. Today I present you with 1870's Rick and Morty. Richard and Mordecai? I dunno. It's giving eerie Children of the Corn vibes and I am happy with that.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dutch marxist Anton Pannekoek

#Anton Pannekoek#Pannekoek#Dutch#The Netherlands#Gelderland#1873#1870's#1800's#1900's#marxism#1960#1960's#marxist theory

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Changeling of Westminster: Intro to Bruno Griffin

Age: 14

Species: Human

Pronouns: He/Him

Appearance: Due to his albinism, Bruno has blue eyes, white hair, and a pale pink complexion. Wears glasses to correct his low vision.

Backstory:

Bruno was born in 1872 to the humans Marcus and Catherine after they had lost their first child to the Red Caps during the Changeling Panic. His father assumed his albinism was due to Catherine having an affair. The marital strife eventually drove her to her death. Marcus abandoned Bruno with his Uncle Ian, who raised him alongside his cousin Henry. He was never told that Henry was the changeling left in place of the older brother he never met. Bruno grew to be bright, curious, but also a trouble maker out of a desire for attention. Ian tried to channel his behavior into something more constructive by showing him around the lab. With Henry gone he had Uncle Ian to himself for years. In 1886, he began an apprenticeship under Dr.Jekyll as his cousin Henry prepared to finish his.

Bruno grows up to be Griffin of The Invisible Man a decade after the action of TCOW. I chose to age him down due to Jekyll and Hyde being published in 1886, while the Invisible Man was published in 1897.

#WIP#Writblr#Writing#The Changeling of Westminster#Bruno Griffin#Gothic Lit#Gothic#Sci Fi#Retelling#Prequel#The Invisible Man#Griffin#Mad Scientist#Albinism#Disability#Ableism#Victorian#1870's#1880's#1890's#19th Century#The Strange Case of Dr.Jekyll and Mr.Hyde#Dr.Jekyll#Gaslamp Fantasy#Fantasy#Punk#Classic Lit

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A superb etching of a London railway & Underground landmark

The Liverpool Street North London Railway terminus opened in 1874

#Liverpool Street#North London Railway#Victorian era#1870's#architecture#Underground station#classical design#omnibus

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Princess Louise#John Campbell Marquess of Lorne#Queen Victoria#Prince Albert Edward#Royal Family#Royal Wedding#1870's#victorian#history#bride#bridegroom#wedding dress#1871#bridesmaids

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dress by the House of Worth, 1877

From MFA Boston

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Harrington’s Buildings (central and eastern sections) and adjacent two storey building, Collins Street, north-side, between Swanston and Elizabeth Streets, Melbourne.

Demolished 1938 for Hotel Australia, in turn demolished in 1990s for Australia On Collins.

This significant portion of Harrington’s Buildings, close to Block Arcade in the centre of Collins Street (Melbourne’s most fashionable street), offered much to the gift purchaser.

Kodak cameras, photographic equipment and photographic supplies were available from a shop operated by Harrington’s Ltd, photographic and cinematographic importers.

Harrington’s Ltd (trading as Harrington Cameras) were a household name throughout Australasia, primarily as agents for British and Continental photographic manufacturers and for their printing, enlarging and framing services. From Harrington’s you could buy Ensigns or Brownies in either ‘Box’ or ‘Folding’ forms. Each camera was guaranteed to take good pictures and free instruction was given to all camera purchasers. Wireless sets were available from £2 to £200.

By taking a staircase to the left of the entrance to Harrington’s you could ascend to the showroom of ‘Georgette’, who would dress you – modes and robes, but particularly millinery.

To the immediate east of Harrington’s: stationary, library supplies and books could be bought from Melville and Mullen booksellers. Irish born bookseller Samuel Mullen (1828-1890) arrived in Melbourne in 1859 and opened a bookshop and library at 55 Collins Street East before later moving to these larger premises at 262-264 Collins Street (31 Collins Street East). One of its special features was a circulating library. Based on Mudie’s of London, Mullen’s library was the first of its kind in Australia that specifically catered for the intellectual elite with serious works and high quality fiction.

In the 1870s, for example, Mullen had warned his staff that a Gentleman ‘appears to be buying more books than he can afford’. That Gentleman was Alfred Deakin (a leader of the movement for Australian federation, later the second Prime Minister of Australia and a foundation member of the Historical Society of Victoria, the forerunner of the RHSV). Deakin always paid. By 1925 Melville and Mullen was not in this location – replaced by the Georgian Café. Financial difficulties forced the fusion of George Robertson & Co. with Mullen’s successors, Melville, Mullen and Slade, as Robertson & Mullens (which in 1960 became Angus and Robertson). Perhaps this is evidenced with the ‘removal sign’, or maybe that is but an advertising ploy to attract customers to a ‘bargain’.

If you decided on a presentation portrait as your gift: you could take the stairs to the floor above where T. Humphrey and Co, artists and photographers would arrange an appointment for a ‘sitting’. Above them, second floor front, Fred de Valle, dentist, promised ‘painless’ treatment, maybe in preparation for a considerable festive dinner.

Your shopping spree could also include shoes and boots from A W Eckersall’s ladies bootery on the ground floor of 260 Collins Street (just next door). Or, exhausted, you could seek refreshment upstairs at the Astor Tea and Luncheon Rooms (Mrs G Helen, proprietor). Alternatively, for tea or lunch you may have walked west to the Café Australia (A. Lucas, proprietor, previously the Vienna Café, immediately next door to Harrington’s Cameras.

Reputedly built in 1879 to the plans of pre-eminent architect Lloyd Tayler (National Bank of Australasia, Australian Club), Harrington’s Buildings was an example of ‘restrained classicism and mannerist details’. It was demolished in 1938 for the erection of the Hotel Australia. In turn, this was demolished in the early 1990s and replaced by Australia on Collins (now under renovation).

0 notes

Text

A view of Talbot Square & Clifton Street showing Yates's Wine Lodge before it's demolition after a large fire and the modern Premier Inn building that took its place.

The building just in view on the right used to be a Midland Bank branch before being part of the Town Hall building that still stands today.

The first photgraph is from the 1870's.

1 note

·

View note

Text

A dress for someone who definitely did not have a pet cat.

Dress

1879-1880

France

The MET (Accession Number: C.I.X.51.24.5a, b)

#dress#extant garments#19th century#1870's#just imagine walking past a cat in that#ohh what a grand time the cat would have! SO many things to swat and catch and bite!

462 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letters from Louise Michel to Théophile Ferré

[120 years ago almost to the day, Louise Michel died at the age of 75, taken by pneumonia. I find it necessary to pay tribute to her...

As we know, Louise Michel was in love with the blanquist Théophile Ferré... In september of 1871, Théophile Ferré is sentenced to death by the 3rd Council of War. He will be shot in Satory on November 28. Upon hearing the news, Louise Michel, who had been detained since June 15 at the Versailles correctional facility, tried to help him. She wrote him three letters, as well as two poems (Les Oeillets Rouges and A mes frères)].

First Letter (Versailles Correctional Facility, September 1871) :

"Since we can correspond today, may my first word be a word of happiness, our very dear delegate. You understand how, in this time of shame, one is happy to see the sons of the Republic so worthy of the cause.

If my letter does not have time to reach you, I too have the right not to see the rest of this life. In the meantime, let’s talk. I hope that in terms of opinions on women, you are no longer reactionary and that you recognise our right to choose peril and death. Moreover, that these rights apply to us broadly. I am writing to you under the oleanders and the orange trees because we have a garden here, but to get here, oh, the things I have seen.

Here is the scene of my arrest: they took my mother to be shot in my place, so I immediately went to set her free by taking her place, and if I was not to be shot there, I believe that I found myself in that spirit all the more calm, because I believed myself to be at my last hour and I thought that our cause was lost. I told them the truth almost as death could have told it, if dead women spoke.

How many things have I seen since. The route on foot they made us take between mounted soldiers, the Château de la Muette, Versailles, Satory and then Versailles again, at the Gare de l’Ouest, and here.

It was like scenes from Dante and paintings by Callot, a thousand times outdated, the agony of revolution mixed with I don’t know what hope. Nameless cowardice and magnificent deeds, this was the moment when you had to hold your hearts high so as not to soil them in the mire.

I await the Council of War. As for my interrogation, in summary I told them I loved and served the Commune with all my heart, from the first day until the last, because it wanted the happiness of the people. And for what I had to say in my defence, I said nothing, having acted according to my convictions. As for what I thought, I had the pleasure of conveying it and it is not a small thing, in certain circumstances, especially when one sees, as I saw, the cowards all shivering with fear, coming to accuse the Commune of everything they knew very well it did not do.

Brother, will we meet again? Will we see our friends again? It doesn’t matter.

I shake your hand wholeheartedly.

I have here with me some poor women whose only crime is to have sent me a little laundry to Neuilly. I have however certified many times that they were not guilty of anything, but I admit that after all I am not thinking of them at the moment.

Goodbye (or) in the life beyond.

Louise Michel".

Second letter (Versailles Correctional Facility, October 3, 1871):

To Citizen Th. Ferré,

Citizen Ferré, I still dare to ask our friend (the Father Foley) to kindly take charge of this letter, especially since he knows well (it’s a bit proud but it’s true) that there can be no exchange of ideas between the other prisoners and me, because they have, more or less, the qualities and the defects of women, and that, precisely, is what I do not have.

So I’m happy to talk to you. I wanted to start my letter by telling you the story of Monsieur Galifet at Bastion 37, but you will read it in my notebook. I prefer to send you the end of Versailles, I left it there:

Yes Versailles is capital. They are our triumphant lords. Dashed this rattling head On top of their crumbling walls. O old hairy Gaul With their bloody and hideous fingers, They took you by the hair, The hairy-handed executioners. But instead, the livid head Will feed the dark crows Who, at night, in their greedy bed, Will tear them to shreds. Reign, judge, you are masters To let us live or die, And the future can choose Between martyrs and traitors.

How capricious one becomes in prison! I speak of the future and these are the memories that come to me.

I am thinking of an evening at a club meeting where some sort of sounding imbecile had made a bloated and heartless proposal whose rather eloquent form drew support and applause. When, full of indignation, I was about to ask to speak, it was you who said everything I wanted to say. Poor crowd, how it needs to be enlightened by people of heart, instead of being deceived by selfish people!

Do you remember this brave man, so stupid, with a Roman profile and name? [Sometime later] he was also with me at a barricade that the three of us held for a long time. At that time I had the courage to help pick up a wounded man, crossing seven or eight times under a hail of bullets, but he was so heavy that I couldn’t help him take the few steps alone. It was our brave speaker who came to help me. It is true that I had called him nearly ten times and that he was not one of us three. But poor man, I haven’t seen him since. Not much remains of that vile, vile multitude of Montmartre, where last winter was so calm and so dignified in the face of provocations. It is true that, for all that, it took great pains to prevent him from believing the deceivers.

Today is the reward! If I say this with bitterness, it is above all for those towards whom I would like the enemies to have less unjust hatred, and the friends of the people to have courage.

In the meantime, goodbye. It seems to me that you are very sad, I send you all the hope I can see on the horizon.

Louise Michel.

(Written up the side: A rather strange thing: we have here a prisoner who was also a prisoner under the Commune, Hamel, I believe. She could tell them how different we were from the Executive.)

Third letter (Versailles Correctional Facility):

Although I have said to you, our dear prisoner, that I would no longer write to you at a time when one can, being alone, feel all the sadness of one’s soul, I love these sinister nights so much that I feel it’s now that I live more, and a time that I should send you my thoughts. Above all, don’t waste time reading my letter right away if you still find something to review in this unfair trial. Allow me to tell you that, according to two fragments of newspapers which had reached me by chance (since we do not read newspapers), that was my first idea. I saw the condemnation stopped in advance and all the prejudices of insult and hatred replacing even the judicial forms of which they have no idea. About that, there are articles they particularly like, article 91 for example; also they put it everywhere.

Two more poor wretches went on trial today: one acquitted; provided that she does not pay more than her life, the other sentenced to death because she says she set the fire out of jealousy. They call it politics!

My last interrogation was very benevolent. They finally seem to understand that the agents provocateurs could one day ask for their heads as they ask for ours and that, on the contrary, the Commune needed as much moderation as courage to resist these well-dressed snakes, because I remember the things they said; there was enough to arouse the indignation of an entire century.

One thing seemed to make an impression on them, it is that (don’t scold me for saying this) when I myself, in the face of all the betrayals which were leading us to defeat, proposed extreme and violent means, the very man who had been condemned to death as an assassin and an incendiary had stigmatised these things with all his energy as crimes against humanity and signs of weakness. It seems that my Captain prosecutor understood what I was saying because I had the honour of seeing two tears in this eyes; he even condescended to escort me to the door with a certain consideration; I confess to you that this surprised me.

Only write to me when there is nothing bad happening against you. But you know that I will always be happy to hear from you anyway. Because you’re condemned I want to say that you are the best amongst us, and above all I would like you to live. If that happens, I would forever forget prison, because my mother is safe and the only person I’m worried about is you and that’s enough.

While I think of it, you can keep the two volumes of the Peloponnese; they are mine.

Do you know why I am so talkative in my letters? It is because, all day, surrounded by our good state prisoners, I hear a host of things so insane which I almost never speak of, except to make some violent outing against the weakness and the lack of common sense of certain people. This does not extend to all, but how many, among these good hearts, have ideas so mad that one should be very ashamed to accuse them of politics.

There are other strange coincidences. Do you remember that I was confused, to my great indignation, with a teacher named Michel? Her sister is here with me. Another coincidence: I also found here the person that I accused of discrediting women at a meeting; both times, she was unfortunate.

You see how calm I am tonight; it seems to me that you are saved. Goodbye, brother. Do you believe it too?

Louise Michel.

0 notes