#1820s portraiture

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

~ Thomas Lawrence, Portrait of Princess of Maria Carolina of Naples and Sicily (1825) (detail)

via les_princesses_immortelles

#thomas lawrence#art#fine art#painting#art history#art detail#english artist#english art#british artist#british art#english painting#british painting#portrait painting#portraiture#19th century#early 19th century#19th century art#roses#floral#romantic aesthetic#old royals#1820s#1825#e

232 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queen Theresa of Bavaria

(Born Princess of Saxe-Hildburghausen)

Artist: Joseph Karl Stieler (German, 1781–1858)

Title: German: Königin Therese von Bayern im Krönungsornat

Genre: Portrait

Style: Historical Period Neoclassicism - 1780-1820 & Romanticism - 1810-1870

Date: 1826

Collection: Neue Pinakothek, Munich, Germany

Queen Theresa (1792-1854) was a daughter of Frederick, Duke of Saxe-Altenburg, and Duchess Charlotte Georgine of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, eldest daughter of Charles II, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. As a child she had grown up in the rather modest capital of her father’s small duchy of Saxe-Hildburghausen, and not in his later capital of Altenburg, which he acquired after the Saxon dukes reorganised their states in 1826. In 1809, Theresa had been on the list of possible brides for Napoleon, but following the latter’s marriage to the Archduchess Marie-Louise, she married the Bavarian Crown Prince Ludwig, on 12 October 1810. Their wedding was the occasion of the first ever Oktoberfest, which has been repeated almost every year since.

Her husband succeeded as king in 1825 but his numerous love affairs caused her some pain, which she tolerated while refusing to allow his mistresses to attend her at court. On one occasion, in 1831, she left the capital to make her disapproval clear – nonetheless, despite the difficulties in their marriage she was the mother of nine children, the oldest, Maximilian, succeeding as king when Ludwig was deposed following the 1848 revolution. Therese proved to be a capable royal consort, heading the government during her husband’s frequent foreign trips, and having some considerable political influence. She was particularly popular with the Bavarian public and was considered the embodiment of an idealised image of queen, wife and mother and was involved in a great number of charitable organisations for widows, orphans and the poor. She was the object of great sympathy during her husband’s very public infidelity with the notorious courtesan, Lola Montez, which contributed to the demands for his abdication in 1848.

This painting must be particularly noted for the extraordinary attention to the queen’s silk embroidered robes, her bracelets, necklace and earrings and the splendid tiara placed alongside the royal crown. Her robe is embroidered with gold leaves and flowers and along the bottom edge the blue and silver diamond lozenges of the Wittelsbach arms are sewn into gold edged ovals. An ermine robe hangs from over her shoulder to the ground and in her left hand she holds a gold bejewelled fan. Despite its small scale this superbly executed portrait holds the viewer’s attention in every detail, and is a testament to the artist’s mastery of grand, royal portraiture.

#queen theresa of bavaria#german painting#portrait#german royalty#royal monarchy#queen#joseph karl stieler#historical period#neoclassicism#romanticism#19th century european

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Research - Fashion Design Movements Through Time

Here I am going to look into the era - picking out key elements about the fashion at the time to see how I can apply them to my type design. To mirror this I will also be looking at the times with how type was designed then to - the combination of these things will help me access how to begin my initial sketches.

I will highlight key words that will help when designing.

1600–1650

Characterized by the broad lace or linen collars. Waistlines rose through the period for both men and women. Other notable fashions included full, slashed sleeves and tall or broad hats with brims. For men, hose disappeared in favour of breeches.

The silhouette, which was essentially close to the body with tight sleeves and a low, pointed waist to around 1615, gradually softened and broadened. Sleeves became very full, and in the 1620s and 1630s were often paned or slashed to show the voluminous sleeves of the shirt or chemise beneath.

1650–1700

Characterized by rapid change. The style of this era is known as Baroque. Following the end of the Thirty Years' War and the Restoration of England's Charles II, military influences in men's clothing were replaced by a brief period of decorative exuberance which then sobered into the coat, waistcoat and breeches costume that would reign for the next century and a half. In the normal cycle of fashion, the broad, high-waisted silhouette of the previous period was replaced by a long, lean line with a low waist for both men and women. This period also marked the rise of the periwig as an essential item of men's fashion.

1700–1750

This era is defined as late Baroque/Rococo style. The new fashion trends introduced during this era had a greater impact on society, affecting not only royalty and aristocrats, but also middle and even lower classes. Clothing during this time can be characterised by soft pastels, light, airy, and asymmetrical designs, and playful styles. Wigs remained essential for men and women of substance, and were often white; natural hair was powdered to achieve the fashionable look. The costume of the eighteenth century, if lacking in the refinement and grace of earlier times, was distinctly quaint and picturesque.

1750-1775

Fashion in the years 1750–1775 in European countries and the colonial Americas was characterised by greater abundance, elaboration and intricacy in clothing designs, loved by the Rococo artistic trends of the period. The French and English styles of fashion were very different from one another. French style was defined by elaborate court dress, colourful and rich in decoration, worn by such iconic fashion figures as Marie Antoinette.

After reaching their maximum size in the 1750s, hoop skirts began to reduce in size, but remained being worn with the most formal dresses, and were sometimes replaced with side-hoops, or panniers. Hairstyles were equally elaborate, with tall headdresses the distinctive fashion of the 1770s. For men, waistcoats and breeches of previous decades continued to be fashionable.

English style was defined by simple practical garments, made of inexpensive and durable fabrics, catering to a leisurely outdoor lifestyle. These lifestyles were also portrayed through the differences in portraiture. The French preferred indoor scenes where they could demonstrate their affinity for luxury in dress and lifestyle. The English, on the other hand, were more "egalitarian" in tastes, thus their portraits tended to depict the sitter in outdoor scenes and pastoral attire.

1775–1795

Fashion in the twenty years between 1775 and 1795 in Western culture became simpler and less elaborate. These changes were a result of emerging modern ideals of selfhood, the declining fashionability of highly elaborate Rococo styles, and the widespread embrace of the rationalistic or "classical" ideals of Enlightenment philosophies.

1795–1820

Fashion in the period 1795–1820 in European and European-influenced countries saw the final triumph of undress or informal styles over the brocades, lace, periwigs and powder of the earlier 18th century. In the aftermath of the French Revolution, no one wanted to appear to be a member of the French aristocracy, and people began using clothing more as a form of individual expression of the true self than as a pure indication of social status. As a result, the shifts that occurred in fashion at the turn of the 19th century granted the opportunity to present new public identities that also provided insights into their private selves. Katherine Aaslestad indicates how "fashion, embodying new social values, emerged as a key site of confrontation between tradition and change."

For women's dress, the day-to-day outfit of the skirt and jacket style were practical and tactful, recalling the working-class woman. Women's fashions followed classical ideals, and stiffly boned stays were abandoned in favor of softer, less boned corsets. This natural figure was emphasized by being able to see the body beneath the clothing. Visible breasts were part of this classical look, and some characterised the breasts in fashion as solely aesthetic and sexual.

This era of British history is known as the Regency period, marked by the regency between the reigns of George III and George IV. But the broadest definition of the period, characterized by trends in fashion, architecture, culture, and politics, begins with the French Revolution of 1789 and ends with Queen Victoria's 1837 accession. The names of popular people who lived in this time are still famous: Napoleon and Josephine, Juliette Récamier, Jane Austen, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, Beau Brummell, Lady Emma Hamilton, Queen Louise of Prussiaand her husband and many more. Beau Brummell introduced trousers, perfect tailoring, and unadorned, immaculate linen as the ideals of men's fashion.

1820s

During the 1820s in European and European-influenced countries, fashionable women's clothing styles transitioned away from the classically influenced "Empire"/"Regency" styles of c. 1795–1820 (with their relatively unconfining empire silhouette) and re-adopted elements that had been characteristic of most of the 18th century (and were to be characteristic of the remainder of the 19th century), such as full skirts and clearly visible corseting of the natural waist.

The silhouette of men's fashion changed in similar ways: by the mid-1820s coats featured broad shoulders with puffed sleeves, a narrow waist, and full skirts. Trousers were worn for smart day wear, while breeches continued in use at court and in the country.

1830s

1830s fashion in Western and Western-influenced fashion is characterized by an emphasis on breadth, initially at the shoulder and later in the hips, in contrast to the narrower silhouettes that had predominated between 1800 and 1820.

Women's costume featured larger sleeves than were worn in any period before or since, which were accompanied by elaborate hairstyles and large hats.

The final months of the 1830s saw the proliferation of a revolutionary new technology—photography. Hence, the infant industry of photographic portraiture preserved for history a few rare, but invaluable, first images of human beings—and therefore also preserved our earliest, live peek into "fashion in action"—and its impact on everyday life and society as a whole.

1840s

1840s fashion in European and European-influenced clothing is characterized by a narrow, natural shoulder line following the exaggerated puffed sleeves of the later 1820s and 1830s. The narrower shoulder was accompanied by a lower waistline for both men and women.

Shoulders were narrow and sloping, waists became low and pointed, and sleeve detail migrated from the elbow to the wrists. Where pleated fabric panels had wrapped the bust and shoulders in the previous decade, they now formed a triangle from the shoulder to the waist of day dresses.

Skirts evolved from a conical shape to a bell shape, aided by a new method of attaching the skirts to the bodice using organ or cartridge pleats which cause the skirt to spring out from the waist. Full skirts were achieved mainly through layers of petticoats. The increasing weight and inconvenience of the layers of starched petticoats would lead to the development of the crinoline of the second half of the 1850s.

Sleeves were narrower and fullness dropped from just below the shoulder at the beginning of the decade to the lower arm, leading toward the flared pagoda sleeves of the 1850s and 1860s.

1850s

1850s fashion in Western and Western-influenced clothing is characterized by an increase in the width of women's skirts supported by crinolines or hoops, the mass production of sewing machines, and the beginnings of dress reform. Masculine styles began to originate more in London, while female fashions originated almost exclusively in Paris.

In the 1850s, the domed skirts of the 1840s continued to expand. Skirts were made fuller by means of flounces (deep ruffles), usually in tiers of three, gathered tightly at the top and stiffened with horsehair braid at the bottom.

Early in the decade, bodices of morning dresses featured panels over the shoulder that were gathered into a blunt point at the slightly dropped waist. These bodices generally fastened in back by means of hooks and eyes, but a new fashion for a [jacket] bodice appeared as well, buttoned in front and worn over a chemisette. Wider bell-shaped or pagoda sleeves were worn over false undersleeves or engage antes of cotton or linen, trimmed in lace, broderie anglaise, or other fancy-work. Separate small collars of lace, tatting, or crochet-work were worn with morning dresses, sometimes with a ribbon bow.

1860s

1860s fashion in European and European-influenced countries is characterized by extremely full-skirted women's fashions relying on crinolines and hoops and the emergence of "alternative fashions" under the influence of the Artistic Dress movement.

In men's fashion, the three-piece ditto suit of sack coat, waistcoat, and trousers in the same fabric emerged as a novelty.

By the early 1860s, skirts had reached their ultimate width. After about 1862 the silhouette of the crinoline changed and rather than being bell-shaped it was now flatter at the front and projected out more behind. This large area was largely occupied by all manner of decoration. Puffs and strips could cover much of the skirt. There could be so many flounces that the material of the skirt itself was hardly visible. Lace again became popular and was used all over the dress. Any part of the dress could also be embroidered in silver or gold. This massive construct of a dress required gauze lining to stiffen it, as well as multiple starched petticoats. Even the clothes women would ride horses in received these sorts of embellishments.

1870s

1870s fashion in European and European-influenced clothing is characterised by a gradual return to a narrow silhouette after the full-skirted fashions of the 1850s and 1860s.

By 1870, fullness in the skirt had moved to the rear, where elaborately draped overskirts were held in place by tapes and supported by a bustle. This fashion required an underskirt, which was heavily trimmed with pleats, flounces, rouching, and frills. This fashion was short-lived (though the bustle would return again in the mid-1880s), and was succeeded by a tight-fitting silhouette with fullness as low as the knees: the cuirass bodice, a form-fitting, long-waisted, boned bodice that reached below the hips, and the princess sheath dress. Sleeves were very tight fitting. Square necklines were common.

1880s

1880s fashion in the in Western and Western-influenced countries is characterized by the return of the bustle. The long, lean line of the late 1870s was replaced by a full, curvy silhouette with gradually widening shoulders. Fashionable waists were low and tiny below a full, low bust supported by a corset. The Rational Dress Society was founded in 1881 in reaction to the extremes of fashionable corsetry.

1890s

Fashion in the 1890s in European and European-influenced countries is characterized by long elegant lines, tall collars, and the rise of sportswear. It was an era of great dress reforms led by the invention of the drop-frame safety bicycle, which allowed women the opportunity to ride bicycles more comfortably, and therefore, created the need for appropriate clothing.

Another great influence on women's fashions of this era, particularly among those considered part of the Aesthetic Movement in America, was the political and cultural climate. Because women were taking a more active role in their communities, in the political world, and in society as a whole, their dress reflected this change. The more freedom to experience life outside the home that women of the Gilded Age acquired, the more freedom of movement was experienced in fashions as well. As the emphasis on athleticism influenced a change in garments which allowed for freedom of movement, the emphasis on less rigid gender roles influenced a change in dress which allowed for more self-expression, and a more natural silhouette of women's bodies were revealed.

The 1890s brought the beginnings of a change in how fashion was presented as well. While illustrations still dominated fashion magazines, printed fashion photographs first appeared in French magazine La Mode Pratique in 1892, where they would continue be a weekly feature.

1900s

Fashion in the period 1900–1909 in the Western world continued the severe, long and elegant lines of the late 1890s. Tall, stiff collars characterize the period, as do women's broad hats and full "Gibson Girl" hairstyles. A new, columnar silhouette introduced by the couturiers of Paris late in the decade signalled the approaching abandonment of the corset as an indispensable garment.

With the decline of the bustle, sleeves began to increase in size and the 1830s silhouette of an hourglass shape became popular again. The fashionable silhouette in the early 20th century was that of a confident woman, with full low chest and curvy hips. The "health corset" of this period removed pressure from the abdomen and created an S-curve silhouette.

1910s

Fashion from 1910 to 1919 in the Western world was characterized by a rich and exotic opulence in the first half of the decade in contrast with the somber practicality of garments worn during the Great War. Men's trousers were worn cuffed to ankle-length and creased. Skirts rose from floor length to well above the ankle, women began to bob their hair, and the stage was set for the radical new fashions associated with the Jazz Age of the 1920s.

1920s

Western fashion in the 1920s underwent a modernization. For women, fashion had continued to change away from the extravagant and restrictive styles of the Victorian and Edwardian periods, and towards looser clothing which revealed more of the arms and legs, that had begun at least a decade prior with the rising of hemlines to the ankle and the movement from the S-bend corset to the columnar silhouette of the 1910s. Men also began to wear less formal daily attire and athletic clothing or 'Sportswear' became a part of mainstream fashion for the first time. The 1920s are characterized by two distinct periods of fashion: in the early part of the decade, change was slower, and there was more reluctance to wear the new, revealing popular styles. From 1925, the public more passionately embraced the styles now typically associated with the Roaring Twenties. These styles continued to characterise fashion until the worldwide depression worsened in 1931.

1930–1945

The most characteristic North American fashion trend from the 1930s to 1945 was attention at the shoulder, with butterfly sleeves and banjo sleeves, and exaggerated shoulder pads for both men and women by the 1940s. The period also saw the first widespread use of man-made fibers, especially rayon for dresses and viscose for linings and lingerie, and synthetic nylon stockings. The zipper became widely used. These essentially U.S. developments were echoed, in varying degrees, in Britain and Europe. Suntans (called at the time "sunburns") became fashionable in the early 1930s, along with travel to the resorts along the Mediterranean, in the Bahamas, and on the east coast of Florida where one can acquire a tan, leading to new categories of clothes: white dinner jackets for men and beach pajamas, halter tops, and bare midriffs for women.

1945–1960

Fashion in the years following World War II is characterized by the resurgence of haute couture after the austerity of the war years. Square shoulders and short skirts were replaced by the soft femininity of Christian Dior's "New Look" silhouette, with its sweeping longer skirts, fitted waist, and rounded shoulders, which in turn gave way to an unfitted, structural look in the later 1950s.

1960s

In a decade that broke many traditions, adopted new cultures, and launched a new age of social movements, 1960s fashion had a nonconformist but stylish, trendy touch. Around the middle of the decade, new styles started to emerge from small villages and cities into urban centers, receiving media publicity, influencing haute couture creations of elite designers and the mass-market clothing manufacturers. Examples include the mini skirt, culottes, go-go boots, and more experimental fashions, less often seen on the street, such as curved PVC dresses and other PVC clothes.

Mary Quant popularized the mini skirt, and Jackie Kennedy introduced the pillbox hat; both became extremely popular. False eyelashes were worn by women throughout the 1960s. Hairstyles were a variety of lengths and styles. Psychedelic prints, neon colors, and mismatched patterns were in style.

US First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy arrives in Venezuela, 1961 In the early-to-mid 1960s, London "Modernists" known as Mods influenced male fashion in Britain. Designers were producing clothing more suitable for young adults, leading to an increase in interest and sales. In the late 1960s, the hippie movement also exerted a strong influence on women's clothing styles, including bell-bottom jeans, tie-dye and batik fabrics, as well as paisley prints.

1970s

Fashion in the 1970s was about individuality. In the early 1970s, Vogue proclaimed "There are no rules in the fashion game now" due to overproduction flooding the market with cheap synthetic clothing. Common items included mini skirts, bell-bottoms popularised by hippies, vintage clothing from the 1950s and earlier, and the androgynous glam rock and disco styles that introduced platform shoes, bright colours, glitter, and satin.

New technologies brought advances in production through mass production, higher efficiency, generating higher standards and uniformity. Generally the most famous silhouette of the mid and late 1970s for both genders was that of tight on top and loose on bottom. The 1970s also saw the birth of the indifferent, anti-conformist casual chic approach to fashion, which consisted of sweaters, T-shirts, jeans and sneakers. One notable fashion designer to emerge into the spotlight during this time was Diane von Fürstenberg, who popularised, among other things, the jersey "wrap dress". von Fürstenberg's wrap dress design, which was among the most popular fashion styles of the 1970s, would also be credited as a symbol of women's liberation. The French designer Yves Saint Laurent and the American designer Halston both observed and embraced the changes that were happening in the society, especially the huge growth of women's rights and the youth counterculture. They successfully adapted their design aesthetics to accommodate the changes that the market was aiming for.

1980s

Fashion of the 1980s was characterised by a rejection of 1970s fashion. Punk fashion began as a reaction against both the hippie movement of the past decades and the materialist values of the current decade. The first half of the decade was relatively tame in comparison to the second half, which was when apparel became very bright and vivid in appearance.

Hair in the 1980s was typically big, curly, bouffant and heavily styled. Television shows such as Dynasty helped popularise the high volume bouffant and glamorous image associated with it. Women in the 1980s wore bright, heavy makeup. Everyday fashion in the 1980s consisted of light-coloured lips, dark and thick eyelashes, and pink or red rouge (otherwise known as blush).

The early 1980s witnessed a backlash against the brightly colored disco fashions of the late 1970s in favor of a minimalist approach to fashion, with less emphasis on accessories. In the US and Europe, practicality was considered just as much as aesthetics. In the UK and America, clothing colours were subdued, quiet and basic; varying shades of brown, tan, cream, and orange were common

1990s

Fashion in the 1990s was defined by a return to minimalist fashion, in contrast to the more elaborate and flashy trends of the 1980s. One notable shift was the mainstream adoption of tattoos, body piercings aside from ear piercing and, to a much lesser extent, other forms of body modification such as branding.

In the early 1990s, several late 1980s fashions remained very stylish among both sexes. However, the popularity of grunge and alternative rock music helped bring the simple, unkempt grunge look to the mainstream by 1994. The anti-conformist approach to fashion led to the popularization of the casual chic look that included T-shirts, jeans, hoodies, and sneakers, a trend which continued into the 2000s. Additionally, fashion trends throughout the decade recycled styles from previous decades, notably the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.

Due to increased availability of the Internet and satellite television outside the United States, plus the reduction of import tariffs under NAFTA, fashion became more globalised and homogeneous in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

2000s

2000s fashion is often described as being a global mash up, where trends saw the fusion of vintage styles, global and ethnic clothing (e.g. boho), as well as the fashions of numerous music-based subcultures. Hip-hop fashion generally was the most popular among young people of all sexes, followed by the retro inspired indie look later in the decade.

Those usually age 25 and older adopted a dressy casual style which was popular throughout the decade. Globalization also influenced the decade's clothing trends, with the incorporation of Middle Eastern and Asian dress into mainstream European, American and Australasian fashion. Furthermore, eco-friendly and ethical clothing, such as recycled fashions and fake fur, were prominent in the decade.

In the early 2000s, many mid and late 1990s fashions remained fashionable around the globe, while simultaneously introducing newer trends. The later years of the decade saw a large-scale revival of clothing designs primarily from the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

2010s

The 2010s were defined by hipster fashion, athleisure, a revival of austerity-era period pieces and alternative fashions, swag-inspired outfits, 1980s-style neon streetwear, and unisex 1990s-style elements influenced by grunge and skater fashions. The later years of the decade witnessed the growing importance in the western world of social media influencers paid to promote fast fashion brands on Pinterest and Instagram.

2020s

The fashions of the 2020s represent a departure from 2010s fashion and a nostalgia (or pseudo-nostalgia) for older aesthetics. They have been largely inspired by styles of the early to mid-2000s, late 1990s, 1980s, 1970s, and 1960s. Early in the decade, The Face remarked on the rapid nostalgia cycle in 2020s fashion: "We’re trapped in what might be called a revival spiral". Popular brands in the United Kingdom, United States, and Australia during this era include Adidas, Nike, New Balance, Globe International, Vans, Kappa, Tommy Hilfiger, Asics, Ellesse, Ralph Lauren, Forever 21, Urban Outfitters, Playboy, and The North Face.

During the 2020s, many companies, including current fashion giants such as Shein and Shekou, have been using social media platforms such as TikTok and Instagram as a marketing tool. Marketing strategies involving third parties, particularly influencers and celebrities, have become prominent promotional tactics. E-commerce platforms such as Depop and Etsy grew by offering vintage, homemade, or resold clothing from individual sellers. Their goal is to promote and support small businesses and the environment instead of major retailers. Thrifting has exploded in popularity in the fashion industry of the 2020s due to it being centered around finding valuable or staple pieces of clothing at a reasonable price.

0 notes

Photo

Portrait of José da Silva Mendes Leal (1820–1886) — Charles Édouard Armand-Dumaresq, 1880 (National Library of Portugal)

#Portrait#Portraiture#Art#Painting#Mendes Leal#Gala#Uniform#Sash#Decorations#Diplomat#Politician#Playwright#Writer#Portugal#Portuguese#19th century#1820#1886#1880#Journalist#Librarian#National Library#Biblioteca Nacional#Minister#Government#Armand-Dumaresq#Glasses#Spectacles#Moustache

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

September 9th 1758 saw the birth of Alexander Nasmyth, the Scottish painter and architect.

Described by fellow Scottish painter, Sir David Wilkie, as ‘the founder of the landscape painting school of Scotland,’ Alexander Nasmyth was a key figure of the Edinburgh cultural Renaissance at the start of the nineteenth century.

Nasmith's training and career was split across both landscape and portraiture, beginning with his early tutelage under James Cumming and Alexander Runcimann within the Norie tradition of decorative landscape painting, followed by a period in the studio of the renowned portraitist Allan Ramsay.

Nasmyth then established his own successful portrait practice and developed a particular niche painting conversation pieces, often family groups in front of their residence and grounds, a combination of the two aspects of his training and talent and also an acknowledgment of his further personal interest in architecture. Two years in Italy allowed him to further develop his landscape approach, often including an architectural element, as seen in the crumbling arch within the Italian scene offered here. In this, Nasmyth’s meticulous depiction of the details reveals the delicate beauty of the vignette; it is expertly framed within his distinctively patterned leaves with a distant landscape unfolding beyond, a method of layering and framing that he repeats regularly and successfully in much of his work. Yet he only turned fully to landscape in Edinburgh around 1792 as portrait commissions began to reduce, possibly due to his increasingly severe political views being incompatible with those of his potential subjects.

In the 1820s he turned his attention to Edinburgh street scenes, which are some of my favourite works, recording fashions, daily activity and architecture, such as ‘Princes Street, with the Royal Institution Building under Construction’, ‘Edinburgh with the High Street and Lawnmarket’ and its companion ‘Shipping at Leith’. His painting of Calton Gaol and the famous view beyond is stunning.

Some works were painted to illustrate the effects that new buildings would have on an area, such as ‘Inverary from the Sea’, painted for the Duke of Argyll to show the setting a proposed lighthouse. In his landscapes he blended classical elements with naturalistic observation and became the founder of the Scottish landscape tradition, influencing many younger painters.

He established a landscape school at his home at 47 York Place in Edinburgh. As a teacher he was highly innovative in insisting his pupils draw from real scenes in the open air, rather than simply reproduce existing drawings or paintings. His pupils included David Wilkie, David Roberts and Clarkson Stanfield. He also developed a sideline in architecture, being responsible for the Dean Bridge in Edinburgh and the temple-like structure atop St Bernard’s Well in Stockbridge.

The pics are of Nasmith, the second is of The Old Tolbooth being demolished, so can be accurately dated as 1817, and the third is a view of Princes Street with the Commencement of the Building of the Royal Institution at the bottom of The Mound, again this helps pinpoint the date as 1825, the building was opened the following year.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portrait of a Nobleman or Royal Figure (Possibly Muhammad Shah Qajar), Abu'l Hasan Ghaffari, Sani' al-Mulk, first half 19th century, Brooklyn Museum: Arts of the Islamic World

This superb miniature portrait of a nobleman displays a mastery of draftsmanship, color, and individualization associated with one of the most talented artists of the Qajar era, Abu'l Hasan Ghaffari, Sani' al-Mulk. Most remarkable is the refined execution of facial details, such as the sitter's intensely gazing eyes, his thick eyelashes, and the varied texture and coloring of his mustache, beard, and eyebrows. Abu'l Hasan is celebrated for his insightful portraiture and is remembered through numerous portrait-head studies, in which he combined his fondness for detail with the color sense of a miniature painter. Some of these were exhibited in the 1998 exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, Royal Persian Paintings: The Qajar Epoch 1785-1925. The artist, who descended from a family of court officials, artists, and historians in Kashan, moved to Tehran in the 1820s to pursue a career in the arts. His talent brought him recognition at the court of the Muhammad Shah Qajar (r. 1834-1848), who sent Abu'l Hasan to Europe for a period to study lithography and painting. This portrait may depict Muhammad Shah in his youth. After Muhammad Shah's death, Abu'l Hasan served Nasir al-Din Shah (r. 1848-1896), who appointed him painter laureate in 1850 and awarded him the title of Sani' al-Mulk (Exalted Craftsman of the Kingdom) in 1861. The Brooklyn Museum houses the finest and largest collection of later Iranian art in the Western hemisphere. Most of the works in this collection come from the Qajar period and largely include oil paintings and lacquer ware. Ladan Akbarnia, Ph.D. Hagop Kevorkian Associate Curator of Islamic Art Size: 5 3/8 x 4 1/4 in. (13.7 x 10.8 cm) Medium: Ink and opaque watercolor on ivory or shell

https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/187701

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mary, Wife of Henry Thompson of Kirby Hall, as Rachel at the Well (1775). Benjamin West (American, 1738-1820). Oil on canvas. Chrysler Museum of Art.

In this theatrical blend of portraiture and history painting, Benjamin West presents his sitter, English aristocrat Mary Thompson, within a biblical scene from the book of Genesis. Such portraits in costume bespeak both the sophistication of the client and the cosmopolitan training of the artist. Born in Pennsylvania, West studied in Italy and eventually settled in London, where his talent in figure painting helped him become President of the Royal Academy and the official court painter to King George III.

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

...ok what's up with corsets?

I mean, mostly just a lot of misconceptions about how they worked and what they were for. I’m going to ramble a lot here, but please know that I am not by any definition an expert on any of this, just a 19th century lit major who’s studied a lot of historical context stuff for research and fun purposes.

One clarification is, to simplify the complex and annoying evolution of language over centuries, if it’s from the early 1800s or later, it’s a corset. If it’s from the 16th-18th centuries, it’s “stays” or a “pair of bodies.” (I think bodies was an earlier term more commonly used for outer garments while stays were undergarments, but don’t quote me on that.) Stays were basically conical with quite a long torso, and you couldn’t lace them particularly tight because metal eyelets weren’t invented until the 1830s and the fabric couldn’t take that strain. Depending on the fashion at the time, their basic function was to create a perfectly smooth, very long silhouette, push your boobs up, or both. Typically their structure came from cording, reeds, whalebone, or layers of paste-stiffened fabric; steel stays from this period are essentially orthopedic devices (or, and I’m obsessed with this idea: fakes created by 19th century fetishists. There’s a reason the 19th century is my favorite historical period and it’s because everything was absolutely nuts, all the time). They also fell in and out of fashion at times – if you look at the naturalistic, Grecian styles of European dresses in the 1820s, for example, many women were wearing either very light stays just to push their bust up, or none at all.

Some nice examples of stays from this period are this, this, and this, from the V&A’s collections. Looking at most portraiture of women from the 16-1700s also pretty clearly displays the conical silhouette that stays produced, but I’m going to refrain from adding images to this post because I already suspect that it’s going to be incredibly, frustratingly long.

Women basically weren’t wearing structured undergarments before the Renaissance, so medieval stays are not a thing.. Although on a fascinating side note, a few years back someone found a bunch of medieval bras, which we had no idea were a thing until then, so that’s really cool.

Regardless of whether you’re talking stays or corsets, two important things. First of all, they were not worn directly against the skin what the hell, firstly because that is incredibly uncomfortable, and secondly because in periods where most people owned fairly little clothing and a lot of that was wool, having a linen or cotton undergarment under all your clothes helped keep them cleaner by separating them from your skin. Historically most often that was a shift, basically just a big long undershirt thing.

The second important thing is whalebone, historically always the number one material for corset boning. Whalebone is an incredibly misleading name, and I hate it, because it took me forever to learn that “whalebone” is not bone but baleen, the bristly stuff that filter-feeding whales have instead of teeth. It’s made from keratin, same as our hair and fingernails. It’s light, flexible, and becomes bendable with warmth, meaning that over time, the boning of a corset would conform to your natural body shape as it was warmed by your body heat, and would stay in that shape. All-steel boning only really became A Thing in the last couple of decades that corsets were an everyday garment for most women, and that wasn’t because of superior structural properties. It was because it was cheaper, given that after centuries of whaling, there were a lot fewer whales to hunt, and acquiring baleen became more expensive and difficult. Even then, a lot of manufacturers just moved to things like featherboning (made from the shafts of feathers), coraline (made from a plant whose name I cannot remember), cane, or just cording (often cotton or paper cords), rather than steel. They also tended to use spiral steels, which can flex more, as opposed to solid steel bones. The main use of steel in corsets was actually to reinforce the closures, the front busk and the back where it laced.

(Most modern corsets are either all-steel waist training corsets or “fashion corsets” boned with flimsy plastic, but there’s actually a modern product called synthetic whalebone which is a plastic designed to replicate the properties of baleen as closely as possible.)

Then we get to the Victorian period, and that’s where pop culture really kind of loses its shit over the idea of corsetry? All the fainting and shifting organs and women getting ribs surgically removed (what) and generally the impression that Corsets Are Horrible Death Garments.

Tightlacing is one of the big things here. Yes, there were Victorian women who tightlaced to reduce their waists to dramatic extremes, and it was not healthy. There are also women today who put themselves through dangerous, unbelievable things to achieve the most fashionable body possible (tw in that link for disordered eating, self-harm, and abuse), and that article only covers the extremes of the professional modeling industry, not everyday things like high heels, for example. Most women who were tightlacing were young, wealthy, and fashionable, not worrying about being healthy enough to work as long as they could achieve ideal beauty – the same people who do this kind of thing now. And part of the reason we know so much about it is that it was extreme and uncommon even then. Medical experts ranted about the dangers of tightlacing, people campaigned against it. It was definitely not the case that all women were going around suffocating in tightlaced corsets all the time.

It’s worth considering our sample of evidence. You see a lot of illustrated fashion plates, which don’t look like real women now, and didn’t then either. By the late 1800s, photographers had already figured out plenty of tricks with angles and posing to make a model look as wasp-waisted as possible. They would also just straight up paint women’s waists smaller in a lot of pictures. And when you consider surviving garments, a disproportionate number of them are from rich young women who hadn’t yet married and had children, because for a variety of reasons those tend to be the clothes that are preserved and survive. The constantly-swooning women of Victorian literature are for some reason presumed to be representative of real life and the constriction of corsets – let me tell you, as someone who studied 19th century literature specifically, everything is exaggerated and melodramatic, especially extremes of emotion (and men also swoon a lot too). It also seems weird that we nod along unquestioning with the most extreme claims of 19th century panics about the medical harm of corsets (rib removal? with 19th century surgery???) and then just mock those silly, stupid Victorians when we read about things like bicycle face or the claim that fast vehicles would make women’s uteruses fly out of their bodies or whatever.

In fact, corsets were a pretty sensible garment in a lot of ways. They seem really restrictive to us now, but historical garments in general didn’t stretch the way modern knit fabrics do. In addition to supporting the bust just like any modern bra, corsets could actually make moving and breathing easier by helping to support the weight of ridiculously heavy dresses. Women did in fact live everyday, active lives wearing them, including lower-class women who worked physically demanding jobs. Late-Victorian women actually started doing a lot more sports, including cycling – that cyclist at the top of the bicycle face article is definitely wearing a corset, for example. They were used to them, too, and used to the specific ways you move in those kind of clothes, which most modern folks who try to wear that stuff one time are not. One interesting thing I’ve heard is that while corsets helped posture a lot – a lot of people today use them medically to help with back pain and support for just that reason – over time that understandably means that if you’re always wearing a corset, your abdominal muscles won’t be very strong because they’re not doing as much work keeping your posture straight. No ab crunches for Victorian women I guess.

Looking at extant Victorian-era clothing, the fashionable wasp-waisted silhouette actually had a lot more to do with the optical illusion achieved with extensive padding, which widened the hips and turned the upper body into a smooth, Chris-Evans-esque triangle. In comparison, the waist looks smaller. (Seriously, look up some photos of late 19th century ladies, their whole front upper body is this perfectly smooth convex curve. That’s all padding.) Silhouette was what the Victorians really cared about, and padding is a lot more sensible and comfortable than tightlacing.

My basic point here is just I guess that there’s a common and weirdly moralizing perception now that the historical corset was, invariably, this horrible constricting heavy steel cage thing that damaged your health and was a Tool Of Patriarchal Oppression. There’s also a lot of really bad costuming in historical dramas. I just think the reality is a lot more interesting. Also that modern steel waist training corsets kind of terrify me?

If you want more info and some good primary and academic sources from people who actually study and recreate historical garments and Actually Know Things, I recommend Bernadette Banner’s videos (here and here) on corsets – also just her stuff in general, I’ve been incredibly happy to see her gaining a lot of attention lately because she’s delightful – this video by historical costumer Morgan Donner wearing a corset daily for a week and talking about what it feels like, and this article, which cites among other things a really interesting late-19th-century study by a doctor trying to actually gather data on corsetry and its effects. Also for that matter, the aforementioned YouTube costumers have respectively made 17th-century stays and a late 19th-century corset, and seeing how these garments are put together is really interesting.

(I feel like I heard somewhere once that S-shape corsets from 1900-1910ish might have been more potentialy harmful because they did weird things to your back posture, but honestly my historical knowledge and interest drops precipitiously when you hit the 20th century.)

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Attributed to Ammi Phillips (b.1788-d.1865), 'Portrait of Mrs. Phoebe Lewis Smith' + 'Portrait of Judge Isaac Smith', 1819 to 1822, oil on canvas, American, for sale est. 14,000 - 18,000 USD in Christie's Important American Furniture, Folk Art, and Silver sale, January 2020, New York, NY, USA.

The portraits of Judge Isaac Smith and his wife Phoebe Lewis Smith are painted in the characteristic format and mode of Phillips' 1820s portraits, with dark background and brightly pigmented shawl and facial features. The inclusion of a newspaper whose banner is just legible and refers to a publication specific to the time and place of his sitter, another feature often seen in Phillips' work. The pendant portraits illustrated here also bear a more desirable feature of American 19th century folk portraiture in the conversant nature of the scrolling arms of the sofa on which the subjects sit. Married on 28 January 1794, Isaac Smith and Phoebe Lewis Smith lived near Amenia, New York, and had seven children. In addition to the responsibilities of a growing family, Isaac Smith was a prominent citizen in Amenia. He served as a Judge, on the Commission to build the Dutchess County Turnpike, as a head of the Federal Company of Amenia, and in 1816 as member of the New York State Assembly. The newspaper Smith holds in his hand, The Plough Boy, may be a reference to what Smith considered his most important accomplishment. Beyond the civic duties Smith fulfilled, he also ran a sizeable farm whose 6,000 sheep produced wool for the burgeoning textile industry of New York and adjacent areas. (x)

#ammi phillips#unknown artist#known artist#known sitter#known sitters#oil on canvas#1810s#1820s#american#christies

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Victorian Portrait Research

Processes Used:

The Daguerreotype

In the mid 1820s Daguerre and Niépce were in partnership and refined the process of using a coating of bitumen of judea. The bitumen was hardened where it was exposed to light and the softened portion was removed from the solvent. The exposure of this lasted for hours and sometimes days. After Niépce passed in 1833, Daguerre concentrated his attention on the light-sensitive properties of silver salts, which were previously demonstrated by Johann Heinrich Schultz and others.

Daguerre then created the Daguerreotype by exposing a thin silver- plated copper sheet to the vapour given off by iodine crystals, producing a coating of light-sensitive silver iodine on the surface. The plate was then exposed in the camera. Initially, this process had a very long exposure to produce the image. However, Daguerre made the crucial discovery that an invisibly faint “latent” image created by a much shorter exposure could be chemically developed into a visible image.

The Calotype/Talbotype

This process was created by William Henry Fox Talbot in 1835 using paper sensitised with silver chloride, which darkens in proportion to its exposure to light. This early “photogenic drawing” process was a printing-out process. Meaning, the paper had to be exposed in the camera until the image was fully visible. A very long exposure (typically an hour or more) was required to produce an acceptable negative.

In late 1840, Talbot worked out a very different developing-out process (a concept pioneered by the daguerreotype process introduced in 1839), in which only an extremely faint or completely invisible latent image had to be produced in the camera, which could be done in a minute or two if the subject was in bright sunlight. The paper, shielded from further exposure to daylight, was then removed from the camera and the latent image was chemically developed into a visible image. This major improvement was introduced to the public as the calotype or talbotype process in 1841.

The Wet Collodion

Wet-collodion process, also called collodion process, early photographic technique invented by Englishman Frederick Scott Archer in 1851. The process involved adding a soluble iodide to a solution of collodion (cellulose nitrate) and coating a glass plate with the mixture. In the darkroom the plate was immersed in a solution of silver nitrate to form silver iodide. The plate, still wet, was exposed in the camera. It was then developed by pouring a solution of pyrogallic acid over it and was fixed with a strong solution of sodium thiosulfate, for which potassium cyanide was later substituted. Immediate developing and fixing were necessary because, after the collodion film had dried, it became waterproof and the reagent solutions could not penetrate it. The process was valued for the level of detail and clarity it allowed. A modification of the process, in which an underexposed negative was backed with black paper or velvet to form what was called an ambrotype.

The Tintype/Ferrotype/Melainotype

There are two historic tintype processes: wet and dry. In the wet process, a collodion emulsion containing suspended silver halide crystals had to be formed on the plate just before it was exposed in the camera while still wet. Chemical treatment then reduced the crystals to microscopic particles of metallic silver in proportion to the intensity and duration of their exposure to light, resulting in a visible image. The later and more convenient dry process was similar but used a gelatin emulsion which could be applied to the plate long before use and exposed in the camera dry.

In both processes, a very underexposed negative image was produced in the emulsion. Its densest areas, corresponding to the lightest parts of the subject, appeared gray by reflected light. The areas with the least amount of silver, corresponding to the darkest areas of the subject, were essentially transparent and appeared black when seen against the dark background provided by the lacquer. The image as a whole therefore appeared to be a dull-toned positive. This ability to employ underexposed images allowed shorter exposure times to be used, a great advantage in portraiture.

To obtain as light-toned an image as possible, potassium cyanide was normally employed as the photographic fixer. It was perhaps the most acutely hazardous of all the several highly toxic chemicals originally used in this and many other early photographic processes.

The Kodak

The original Kodak camera, introduced by George Eastman, placed the power of photography in the hands of anyone who could press a button. Unlike earlier cameras that used a glass-plate negative for each exposure, the Kodak came preloaded with a 100-exposure roll of flexible film. After finishing the roll, the consumer sent the camera back to the factory to have the prints made. In capturing everyday moments and memories, the Kodak's distinctive circular snapshots defined a new style of photography--informal, personal, and fun.

How the Portraits were lit:

Windows as a source of light for portraits have been used for decades before artificial sources of light were discovered. According to Arthur Hammond, amateur and professional photographers need only two things to light a portrait: a window and a reflector. Although window light limits options in portrait photography compared to artificial lights it gives ample room for experimentation for amateur photographers. A white reflector placed to reflect light into the darker side of the subject's face, will even the contrast. Shutter speeds may be slower than normal, requiring the use of a tripod, but the lighting will be beautifully soft and rich.

The best time to take window light portrait is considered to be early hours of the day and late hours of afternoon when light is more intense on the window. Curtains, reflectors, and intensity reducing shields are used to give soft light. While mirrors and glasses can be used for high key lighting. At times colored glasses, filters and reflecting objects can be used to give the portrait desired color effects. The composition of shadows and soft light gives window light portraits a distinct effect different from portraits made from artificial lights.

While using window light, the positioning of the camera can be changed to give the desired effects. Such as positioning the camera behind the subject can produce a silhouette of the individual while being adjacent to the subject give a combination of shadows and soft light. And facing the subject from the same point of light source will produce high key effects with least shadows.

Settings of the Cameras:

The exposure times were very long at the time. For some photographs it could take up to several days to take a photograph. However for portrait photography the exposure time would be between 30 seconds to 5 minutes (sometimes even longer).

How the Subjects Looked:

The main reason for the subjects of photos to not smile was because of the exposure times. It was important for the subject to stay perfectly still so there was no motion blur.

Early photography was also heavily influenced by paintings, which also meant no smiling as it was a very serious moment.

Another reason for none of the subjects to be smiling is because they weren’t alive at the time the photograph was taken. In Victorian times, it was believed photographs were a passage to immortality and therefore they would take a photo of the recently deceased person as a way to preserve the living for future generations.

The clothes victorian people wore mainly depended on their social status. Wealthy Victorians wanted to be fashionable and some spent a lot of time and money on their clothes. The fabric of their clothes would be expensive like silk and satin. The poor however, weren’t able to spend much on their clothes and therefore they had to choose practical and warm clothing. They also wouldn’t have much to select for clothing.

The subjects were also very poised and this was because some of the subjects were clamped in place so they couldn’t move whilst the photo was being taken.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Decade

Project: Decade. #Decade

In the mid-1820s, Nicéphore Niépce first managed to fix an image that was captured with a camera, but at least eight hours or even several days of exposure in the camera were required and the earliest results were very crude.

The First Cameras

“The basic concept of photography has been around since about the 5th century B.C.E. It wasn't until an Iraqi scientist developed something called the camera obscura in the 11th century that the art was born.

Even then, the camera did not actually record images, it simply projected them onto another surface. The images were also upside down, though they could be traced to create accurate drawings of real objects such as buildings.

The first camera obscura used a pinhole in a tent to project an image from outside the tent into the darkened area. It was not until the 17th century that the camera obscura became small enough to be portable. Basic lenses to focus the light were also introduced around this time.

The First Permanent Images

Photography, as we know it today, began in the late 1830s in France. Joseph Nicéphore Niépce used a portable camera obscura to expose a pewter plate coated with bitumen to light. This is the first recorded image that did not fade quickly.

Niépce's success led to a number of other experiments and photography progressed very rapidly. Daguerreotypes, emulsion plates, and wet plates were developed almost simultaneously in the mid- to late-1800s.”

Source: https://www.thesprucecrafts.com/brief-history-of-photography-2688527

Retouched version of the earliest surviving camera photograph, 1826 or 1827, known as View from the Window at Le Gras

Photography has long been influenced by painting and art.

“The relationship between painting and photography has extended the possibilities of image creation. When photography appeared on the scene, it was supposed to herald the democratization of portraiture (among other genres, like landscapes and still-lifes). Photography gave painting the freedom it needed to burst into the rich fountain of expression it is today. There are many classic and modern painters whom, thanks to their skills with lighting and conceptualization, can serve as valuable guides for today's photographers.”

Johannes Vermeer (1632 – 1675)

Source:https://www.lightstalking.com/8-painters-real-effect-todays-photography-photographers-influenced/

My Decade to research – the 1980’s

Timeline of 1980’s Events

Overview:

“The decade was great socioeconomic change due to advances in technology and a worldwide move away from planned economies and towards laissez-faire capitalism.

As economic deconstruction increased in the developed world, multiple multinational corporations associated with the manufacturing industry relocated into Thailand, Mexico, South Korea, Taiwan, and China. Japan and West Germany saw large economic growth during this decade. The AIDS epidemic became recognized in the 1980s and has since killed an estimated 39 million people (as of 2013).[1] Global warming became well known to the scientific and political community in the 1980s.

The United Kingdom and the United States moved closer to supply-side economic policies beginning a trend towards global instability of international trade that would pick up more steam in the following decade as the fall of the USSR made right wing economic policy more powerful.

The final decade of the Cold War opened with the US-Soviet confrontation continuing largely without any interruption. Superpower tensions escalated rapidly as President Reagan scrapped the policy of détente and adopted a new, much more aggressive stance on the Soviet Union. The world came perilously close to nuclear war for the first time since the Cuban Missile Crisis 20 years earlier, but the second half of the decade saw a dramatic easing of superpower tensions and ultimately the total collapse of Soviet communism.

Developing countries across the world faced economic and social difficulties as they suffered from multiple debt crises in the 1980s, requiring many of these countries to apply for financial assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. Ethiopia witnessed widespread famine in the mid-1980s during the corrupt rule of Mengistu Haile Mariam, resulting in the country having to depend on foreign aid to provide food to its population and worldwide efforts to address and raise money to help Ethiopians, such as the Live Aid concert in 1985.”

Source:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1980s

Timeline of major events: (from a very American perspective)

Photography and photographers in the 1980’s

Equipment:

The 80s were a peak time in photography. 35mm cameras were just starting to shift from predominantly mechanical devices into slightly more advanced machines. Having micro-electronic systems at the heart of a camera became the new normal and that made photography easier; new features progressed from more accurate shutter control to program full auto-exposure, to multi-segment light metering systems, to automatic reading of ASA/ISO codes, to integrated motors for advancing and rewinding, and finally AutoFocus (although AF didn’t truly come into its own until the next decade). The dominant manufacturers at the time are sometimes referred to as the ‘Big Five’: Canon, Minolta, Nikon, Olympus, and Pentax. These brands produced the majority of 80s cameras and are now classic models.

CANON AE-1 PROGRAM

MINOLTA X-700

NIKON FA

Olympus OMG

Pentax P3

Source: https://www.keh.com/blog/thats-so-80s-cameras-from-the-1980s/

Photographers:

An American perspective of 80′s photography...

“In the ’80s, new wave and hip hop exploded, graffitied subway cars and gritty nightclubs colored New York City, and John Hughes’s tales of teenage angst like Sixteen Candles (1984) and The Breakfast Club (1985) seized the big screen. Meanwhile, an energized, punk-infused youth culture developed within the context of the ongoing sexual liberation that began in the ’60s, the AIDS epidemic, and the conservative leadership of President Ronald Reagan and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Below are eight photographers who captured the decade’s young people in all their vibrant individuality.”

Source: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-photographers-captured-rebellious-youth-80s

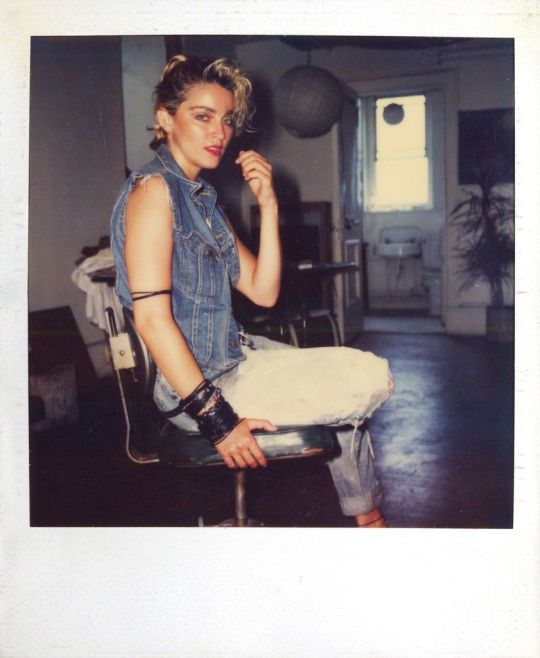

Richard Corman

Madonna, Polaroid 4, Milk Gallery

A very British perspective on 80′s street photography...

Rob Bremner, Liverpool

The 1980’s are widely regarded as Liverpool’s lowest ebb. A time when work in the city was scarce, alienation from the rest of the country was peaking, and newfangled drugs were tightening their grip on the city’s housing estates.

During this period Rob Bremner, 54 – then a shaggy-haired student from Wick, Scotland – was photographing the region’s inner-city wards, as they came to terms with a Conservative government whose policies appeared to deliberately degrade them.

Source: https://www.huckmag.com/art-and-culture/photography-2/back-in-the-day-photos-of-liverpool-in-the-80s/

The other end of the spectrum - high glamour fashion photography...

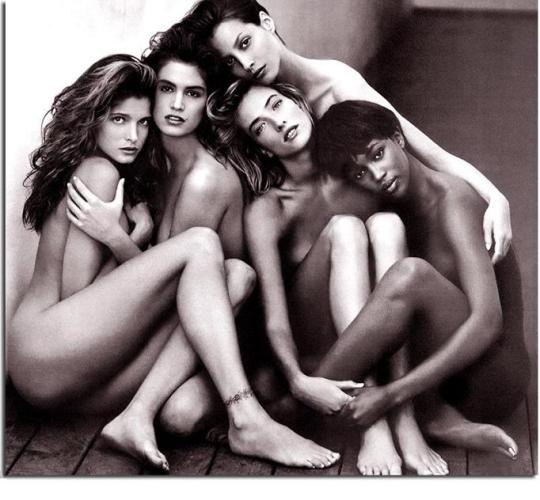

Stephanie,Cindy,Christy,Tatjana & Naomi photographed by Herb Ritts (1989)

“While some of the most creative fashion photography of the 1980s continued to be produced by 'old-timers' like Richard Avedon - see, for instance, his narrative advertising campaign "The Diors,"or his nude shot of Nastassja Kinski entwined with a snake - younger photographers also emerged into the limelight, including: Herb Ritts (1952-2002), best-known for his iconic shot of "Stephanie, Cindy, Christy, Tatjana, Naomi, Hollywood, 1989" which appeared in Rolling Stone Magazine; Bruce Weber (b.1946) who presented a new outlook on masculinity through his photo-shoots for Armani and Calvin Klein, as did Robert Mapplethorpe (1946-89) with his homoerotic shots; and Gian Paolo Barbieri (b.1938), noted for his work for fashion designers Armani, Versace, Dolce & Gabbana, Pomellato, and Giuseppe Zanotti. At the same time, women's independence was emphasized in various settings, by photographers like Denis Piel (b.1944) and Bert Stern (1929-2013).

Controversy, always a handy tool with which to boost flagging commercial fortunes, reared its head as a result of Benetton's fashion campaign, shot by Oliviero Toscani (b.1942). Images included one of a patient dying of AIDS in front of grieving relatives, while others incorporated references to racism, war, religion and the death penalty.

The leading supermodels of 1980s fashion photography included: Gia Marie Carangi, Ines de la Fressange, Cheryl Tiegs, Christie Brinkley, Paulina Porizkova, Brooke Shields, Heather Locklear, Carol Alt, and Elle Macpherson, among others. It was during this decade that supermodels stopped being seen as individuals and started to be regarded as images, just like movie stars. Witness the celebrity party shots taken by fashion photographer Roxanne Lowit (b.1965) of supermodels like Elle Macpherson, Naomi Campbell and others.”

Source: http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/photography/fashion.htm#eighties

Grace Jones, Jean-Paul Goude, New York (1981)

“I wanted to focus on Grace’s masculinity – to use what other people thought an embarrassment, and turn it around to her advantage. I wanted to create – with her, of course – a new character. It went beyond just a haircut, it was an attitude. It was new and strong and ambiguous. You didn’t know if it was a man trying to be a girl or a girl trying to be a man. It was a revolution. I remember the A&R guys at Island saying, “Are you fucking crazy? This is never going to work.” And of course it did.”

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/aug/01/jean-paul-goude-best-photograph-grace-jones-nightclubbing

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Art of China’s Empresses Reveals Their Powerful, Secret Lives

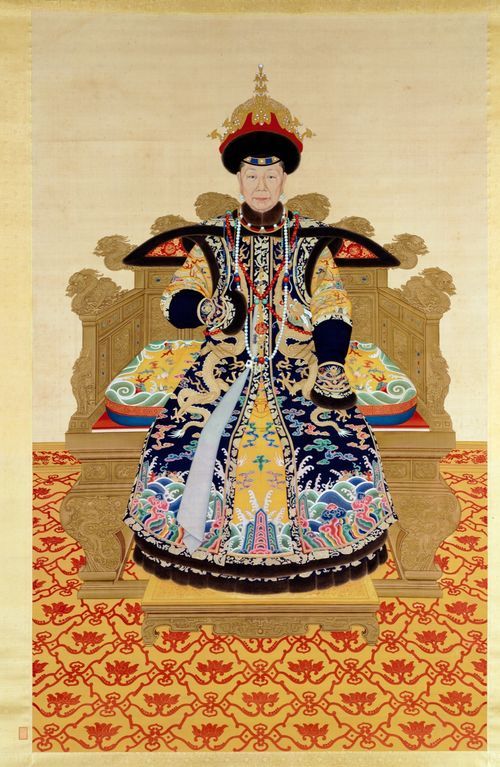

Probably Giuseppe Castiglione and other court painters, Empress Dowager Chongqing at the Age of Seventy, ca. 1761. © The Palace Museum.

Probably Giuseppe Castiglione and other court painters, Empress Xiaozhuang, ca. 1750. © The Palace Museum.

At the onset of Empresses in the Palace, the 2011 miniseries that caused a sensation in China, a beautiful young woman, Zhen Huan, is paraded before the emperor. She is one of many marriage-age girls who have been summoned to Beijing’s Forbidden City to be considered for the Yongzheng Emperor’s harem. Although it is an honor to be chosen as an imperial consort, Zhen is dismayed—she must leave her family behind and enter into a new life of luxury, restriction, and scheming ambition.

In the historical epic, set against the backdrop of the flourishing Qing Dynasty (1644–1912) in the 18th century, Zhen navigates the treacherous, strictly regulated court, where eight ranks of consorts compete with the top empress and vye for the emperor’s attention. (While there was only one empress at a time, the larger lower ranks could move up the social ladder, especially by bearing sons.) At the top of this food chain stood the empress dowager—a consort who had either installed her son on the throne, or was the widowed primary wife of a previous emperor.

The real women who lived in the palace are shrouded in mystery, but Daisy Yiyou Wang and Jan Stuart—the curators of a new exhibition that delves into the empresses’ lives—emphasize that the TV show is a dramatization. At least, there’s not enough evidence to prove that the salacious backstabbing and love affairs that dominate the plot actually took place.

“Empresses of China’s Forbidden City, 1644–1912,” a collaboration between the Palace Museum in Beijing; the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts; and the Freer and Sackler Galleries in Washington, D.C. (where it is now on view), capitalizes on the popularity of such costume dramas. The exhibition centers on five empresses’ little-acknowledged influence on art, religion, and politics through the furniture and objects they used, the paintings they enjoyed, and the jewelry and clothes they wore.

Court hat with phoenixes. Probably Imperial Workshop, Beijing, 18th or 19th century. © The Palace Museum.

Festive robe with bats, lotuses, and the characters for longevity, Jiaqing period, 1796–1820. Probably Imperial Silk Manufactory, Suzhou (embroidery), and Imperial Workshop (tailoring). © the Palace Museum.

Pair of bracelets with bats, peaches, and flowers, probably 19th or early 20th century. © The Palace Museum.

Seal of empress with double-headed dragon with box, tray, lock, key, and plaques, 1922. © The Palace Museum.

Hairpin with figure and vase, 18th or 19th century. © The Palace Museum.

The relative obscurity of these women runs counter to our understanding of royalty today. “If you watch the royal wedding in England, it’s a public affair, a spectacle,” Wang said. “Back then, imperial women were probably completely invisible to the general public.” In European monarchies, copies of rulers’ portraits were circulated around the world for others to venerate; in China, access to imperial powers was a privilege, their images considered sacred.

The curators also knew they were up against pernicious gender bias in their field. Scholars of Chinese art history generally believed that women at court had access to inferior art, fashion, and decorations compared to those used by the emperor. “People questioned us from the beginning because we didn’t think objects used by women and made for women were secondary art objects,” Wang said. She was convinced that some of the most spectacular pieces in the Palace Museum collection were enjoyed by powerful women. She was right.

Court painters, Drinking Tea from Yinzhen’s Twelve Ladies, 1709–23. © The Palace Museum.

Probably Giuseppe Castiglione and other court painters, Consort of the Qianlong emperor and the future Jiaqing emperor in his boyhood, probably 1760s. © The Palace Museum.

The curators found that the quality of art and objects owned by these high-ranking ladies matched those of the emperor, though they didn’t always feature the same motifs. “There’s a longstanding thought in Chinese culture that if you have good omens, images of what is desired surrounding a person, that can help actualize the goal,” Stuart said. Thus, women in the court found themselves surrounded by images of mothers and sons, or symbols suggesting fertility—a woman holding a seeded gourd, or two interlocking jade circles, a reference to continuity.

Their quarters were decorated with exquisite pieces of furniture. One delicate lacquer cabinet in the exhibition—whose staggered shelves offer discreet places to put personal treasures—is painted with a delicate landscape scene and auspicious motifs like the bat. Each piece in an empress’s living space was similarly spectacular and refined.

Festive robe with bats, clouds, and the characters for longevity, Qianlong period, 1785 or earlier. Probably Imperial Silk Manufactory, Nanjing (weaving), and Imperial Workshop (tailoring). © the Palace Museum.

Still, the lives and activities of these women have been obscured for centuries. The Qing court, like many other monarchies around the world, had a patrilineal structure. There was a tradition to record the emperor’s life in great detail, but no such tradition for his wives. “To say they’re not documented at all,” however, “would be a false statement,” Wang said.

Often, the influence of the empresses is only obliquely referenced in archival documents written by the emperor, and so they are characterized from their husband’s or son’s point of view. “Although it’s not strictly articulated, you can get a very strong hint that many of these women were educated, they could talk about state affairs, and be the soulmate of their husband,” Wang said. The empress was also expected, like women all over China, to be a good household manager.

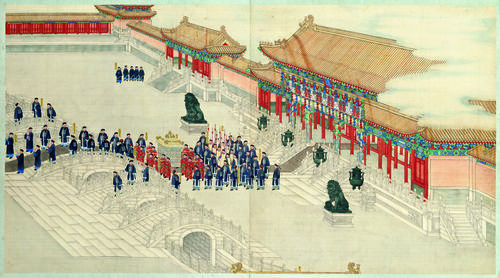

Qing Kuan and other court painters, The Grand Imperial Wedding of the Guangxu Emperor (detail), ca. 1889. © The Palace Museum.

To navigate the intense competition at court, savvy networking with both men and women became paramount for success—and survival. The women who rose to power in the imperial court were those who understood the rigid social codes and worked to exploit their possibilities. Their influence on state affairs “was more about subtle subversion than overt,” Wang said, and often went undocumented.

Shrewd dowager empresses took advantage of traditions of filial piety, which demanded that the emperor bow to no one—except for his mother. “That quirky fact is a nice way to be reminded that in the Manchu culture, women actually had dignity, authority, and status,” Stuart said. Empress dowager Chongqing was visited by her son, the Qianlong Emperor, almost every day, Stuart observed, and though her advice—on battle strategy, or how to pray—was not always recorded, we know from historical records that he did, in fact, follow her suggestions.

Ritual space in the Main Hall of the Palace of Longevity and Health. Courtesy of the Palace Museum, Beijing. © The Palace Museum.

Empresses could additionally wield influence as religious patrons. Empress Xiaozhuang, who was Mongolian, was the first person to bring a dedicated worship of Tibetan-style Buddhism to the Qing court, which became the main religion practiced there. As part of her patronage, she commissioned a tremendous amount of high-quality art for the temple near her residence. A portrait of Xiaozhuang from around 1750 appropriately shows the empress in a monkish brown gown, clutching prayer beads.

The Qing dynasty’s last empress, Cixi, achieved an unprecedented level of overt influence, “controll[ing] the power of the court for more than 40 years,” Wang said. Cixi played up her position as the senior matriarch to manipulate the men in her life, especially her husband, son, nephew, and grandnephew, all of whom became emperor at one point. When her son ascended the throne as a little boy, Cixi ruled as co-regent with another woman and the emperor’s brother. “She must have had incredible people skills,” Wang said.

Empress Dowager Cixi with foreign envoys’ wives in the Hall of Happiness and Longevity (Leshou tang) in the Garden of Nurturing Harmony (Yihe yuan), ca. 1903–05. Photo by Yu Xunling. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

Cixi’s subversion of gender roles isn’t found in texts, but in art. In the Chinese tradition, the most important person is depicted as the largest figure in a painting. In one work showing Cixi playing chess with her son, she is tellingly shown as bigger than the emperor.

Cixi deeply understood the power of images. At the dawn of the 20th century, invasive foreign powers seeking an “open-door” policy in China threatened the Qing empire. Cixi cannily began to cultivate relationships with foreign diplomats, especially their wives. She sent weekly gifts to Sarah Pike Conger, the wife of an American ambassador. Conger convinced Cixi to let an American painter, Katharine A. Carl, create her portrait. “For Westerners to see the real her rather than a dragon lady—that’s the kind of press she got at the time—was quite a coup,” Wang explained. She caused a revolution in Chinese court portraiture when she had an official portrait of herself exhibited at the World’s Fair.

For the first time, the public was invited to not only know of the empress’s great power, but to gaze upon her powerful visage. It was a transgressive moment of significant cultural sway, a “coming out” for the hidden female leaders of China’s Forbidden Palace. The curators likewise hope that the exhibition will inspire other scholars of history, Wang said, to pay attention to women’s lives. “There’s a lot to be uncovered.”

from Artsy News

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I googled this painting because it resembles my niece, and found something really interesting: apparently this painting may have been misattributed before, until dating forced them to reevaluate, since the date range they give here definitely doesn't overlap with Fontana's lifetime. The idea of portrait painters from centuries later just deciding to do some portraits of long-dead subjects so they can exercise their skills at 16th century Italian portrait style is also so charming.

Artist Attributed to manner of Fontana, Lavinia (Italian painter, 1552-1614)

Earliest Date possibly about 1750

Latest Date possibly about 1820

Description The young, blond woman pictured is Gabrielle d’Estrées (1593-1599), daughter of the Governor of the Isle de France. She became the mistress of Henry IV of France in 1592 shortly after losing interest in her own husband Nicholas d’Amerial, Seigneur of Liancourt. The portrait shows the elaborate dress, detailed embroidery and abundant jewels so characteristic of Fontana’s portrayal of female sitters.

Notes Certainly not by Fontana herself, this painting is most probably the work of an artist of the late eighteenth century, working not only in the style of Fontana, but also on portraits of the social elite of her time. In style and subject matter, the Wakefield portrait also recalls the work of Jean Ducayer (also Ducuyer or De Cayé), a French portrait painter active during the seventeenth century. He is known to have admired Italian artists of the sixteenth century, and his style is remarkably evocative of Fontana’s meticulous approach to portraiture.

Author Christopher Wright

Portrait of Gabrielle d’Estrées by Lavinia Fontana, ca 1593-99 France, Wakefield Art Gallery

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portrait photograph of the actress Emília das Neves (1820–1883)

#Portrait#Photograph#Emília das Neves#Actress#Portugal#Crinoline#19th century#1820#1883#Art#Portraiture#Portuguese#Theatre

1 note

·

View note

Photo

THOMAS LAWRENCE British, 1769-1830 “Portrait of Mary Anne Bloxam”(later Mrs. Frederick H. Hemming) c. 1824-25 Oil on panel Photo is taken by: @robertpuffjr After the death of Sir Joshua Reynolds in 1792, Thomas Lawrence was appointed Painter in Ordinary to King George III. Drawing inspiration from Reynolds’s style, with its allusions to the old masters, Lawrence dominated society portraiture in England. He was knighted in 1815 and elected president of the Royal Academy in 1820. His accession to this office no doubt prompted his desire to own the original design by Giovanni Cipriani for the diploma awarded to new Royal Academicians. Cipriani’s drawing belonged to Richard Baker, who offered to give it to Lawrence. In return Lawrence volunteered to paint a portrait of Baker’s great-nephew, Frederick Hemming. Sittings for the portrait were underway when Baker died and Hemming inherited his collection. Lawrence also coveted Baker’s drawings by Raphael and offered Hemming a companion portrait of his fiancée, Mary Anne Bloxam, in exchange for them. Bloxam was reputedly an accomplished porcelain painter, and in her portrait holds a brush as if busy at work; she is depicted in a modish white Grecian dress. (This writeup is taken from the description at Museum.) Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas USA #thomaslawrence #thomaslawrencepainting #lawrence #kimbellartmuseum #historyofart #arthistory #greatworksofart #artmuseum #art #artist #masterpiece #painting #museumvisit #artlover #artists #artblogger (at Kimbell Art Museum) https://www.instagram.com/p/CecfSA6L9BC/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=