#13th-century Cathédrale Notre-Dame in Amiens

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY OF MEDIEVAL ART LIX

Nôtre Dame de Paris

The fourth of five posts on the long, complex history of the Cathedral of Nôtre Dame.

IV. The Nineteenth-Century Restoration

Sans doute, c’est encore aujourd’hui un majestueux et sublime édifice que l’église de Notre-Dame de Paris. Mais si belle qu’elle se soit conservée en vieillissant, il est difficile de ne pas soupirer, de ne pas s’indigner devant les dégradations, les mutilations sans nombre que simultanément le temps et les hommes ont fait subir au vénérable monument. Victor Hugo, Nôtre Dame de Paris, 1831.

Restaurer un édifice, ce n’est pas l’entretenir, le réparer ou le refaire, c’est le rétablir dans un état complet qui peut n’avoir jamais existé à un moment donné. Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

Victor Hugo’s novel, Nôtre Dame de Paris (1831) drew attention to the deplorable condition of the Gothic cathedral of Paris. The novel’s success was partvof a reawakening of interest in medieval art and history, which had long been denigrated and ignored. In 1841, recognizing the nationalistic value of a monument created in an indigenous French style, the July monarchy formed a committee to gather professional opinions concerning the 700 year-old edifices’s condition. Based on the committee’s findings, in 1844, King Louis-Philippe ordered a sweeping preservation program including the complete restoration of Nôtre Dame and the construction of a new sacristy.

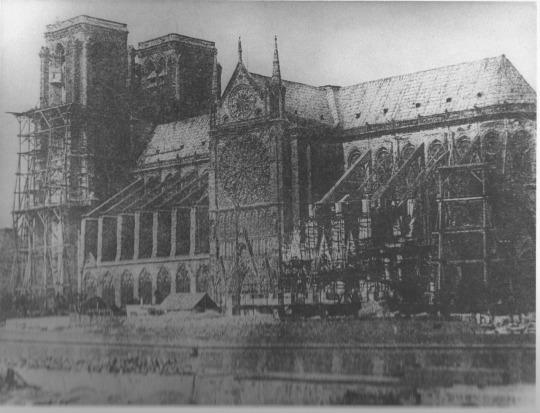

above: Nôtre Dame as construction site, c. 1850

The architects chosen to rebuild Nôtre Dame, Jean-Baptiste Lassus and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, had just completed the restoration of the Sainte Chappelle. Prior to that Viollet-le-Duc had also rebuilt the monastic church of Vézelay, which saved it from imminent collapse. Other than experience, there were few established protocols or resources to consult concerning the restoration of medieval buildings and the scope of the Nôtre Dame project was daunting: the mortar binding the ashlar masonry had eroded to the extent that pieces of stone fell to the ground on a daily basis. The stained glass of the clerestory had been replaced with 18th-century grisaille glass. After centuries of neglect, during the violent period of the Revolution, the cathedral had been deconsecrated and its sculpture defaced or crudely hacked off the building by the mobs. The crossing spire had been declared unstable and removed in the 1830s. The bishop’s palace was crumbling into the Seine.

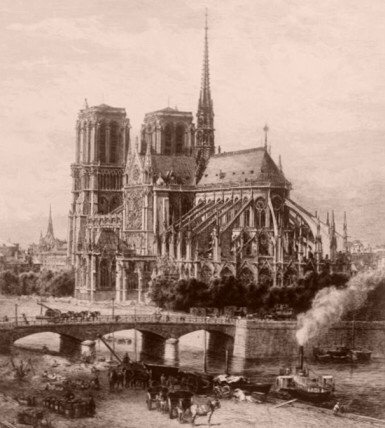

above: The Ile-de-la-Cité c. 1830

In the Conseils pour la restauration en 1849, the co-authors Viollet-le-Duc and the Inspecteur Général des Monuments Historiques, Prosper Merimée, state that:

Les architectes attachés au service des édifices diocésains, et particulièrement des cathédrales, ne doivent jamais perdre de vue que le but de leurs efforts est la conservationde ces édifices.

In practice st Nôtre Dame, however, Viollet-le-Duc’s approach to historical monuments restoration was idealist and holistic. For him, the cathedral’s form existed independently of the materials that composed it at any given time; therefore the form, and not the materials, were the object of restoration. The medieval building fabric would be replicated, but the retention of original stone and glass was not essential. Gothic masonry could be recut or removed to implement a gothicizing solution that harmonized better with the totality of the building, or redesigned, if necessary, to assure structural and or aesthetic integrity. Where there was doubt about original appearances or configurations, other Gothic cathedrals would serve as models. The result would be half recreation of the historical cathedral of Paris, half catalogue of 19th-century conceptions of architectural and sculptural ideas current in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. A delapidated medieval building was transformed into a crisply pointed allegory of medieval architecture.

above: Viollet-le-Duc and Lassus, Nôtre Dame façade, 1847

When Viollet-le-Duc visited Pisa, he found the sight of the torre pendente to be “désagréable” and opined that it should be corrected. The imperative to “correct” irregularities and errors in the original construction is a defining component of his restoration practice at Nôtre Dame. He and Lassus went far beyond conserving the Gothic fabric and repairing damage and wear. Over the long course of its construction, multiple medieval revisions to the design had resulted in many irregularities and discontinuities, which posed no threat to structural integrity. For example, the chapels between the nave buttresses had been added at different times in the 13th and 14th centuries and differed in size and decoration. Together they formed a micro-history of the evolution of Gothic chapel design within the broader narrative of cathedral design.

Viollet-le-Duc demolished the back walls of all of chapels and rebuilt them to a uniform size to be flush with the buttresses and applied a generic decorative program across them all. This imposition of anachronistic notions of visual consistency deprived the building of massive amounts of 13th-century masonry and decorative carving and gratuitously obliterated a bit of architectural history. In the equally destructive “correction” of the perimeter wall of the ambulatory, a delicate business involving the shifting and rebuilding walls while they supported the vaults, excised still more medieval stone. As a result of these needless interventions, the lower level of the exterior masonry, which wraps around the entire building, is entirely 19th century work. This high-handed approach is an example of historical destruction, not preservation.

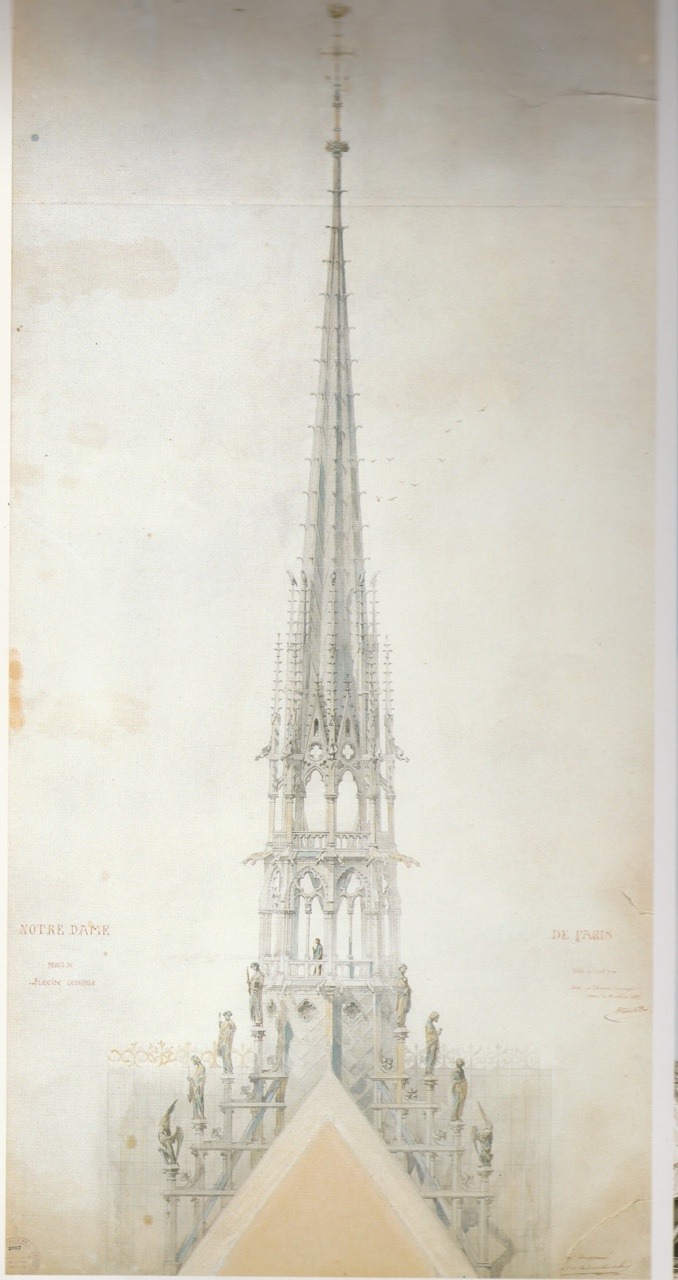

above: Viollet-le-Duc, design for Nôtre Dame flèche, c. 1855

Lassus and Viollet-le-Duc believed that the cathedral was incomprehensible without its sculpture and stained glass and insisted in their proposal that all of the stone sculpture be restored. As no reliable visual record of the sculptures existed, the team of 23 stone carvers were instructed to find and copy equivalents at Chartres, Reims, and Amiens. Based on different models, carved by numerous artists, at different times, the resulting “program” was unified by obliging the sculptors to work in a singie communal style. The sculptures of the façade formed a survey of Gothic cathedral sculpture that was then averaged and masked. The “restored” jamb figures did not replicate the originals nor did their style correspond to any historical medieval practice. The sculpture of the west portals are a misleading, medieval-flavored pastiche that blur rather than sharpen the view into French history supposedly provided by the cathedral.

When it showed signs of imminent collapse, the thirteenth-century spire had been removed in the 1830s. The plan submitted by the architects to the planning committee had included steeples, which had been planned in the Middle Ages but never built, but made no provision for restoring the spire. After the steeples were harshly criticized and dropped from the plan, the spire was added, relatively late in the project, to create a vertical accent. The absence of accurate, detailed images of the original did not stop Viollet-le-Duc from devising a convincing structure that represented a “typical” Gothic spire, but one that had no meaningful connection to the building. All the uninformed post-fire blather about the “iconic” spire completely misses this point.

The restoration of Nôtre Dame was completed in 1864, 20 years after it was launched. Lassus had died in 1857 and Viollet-le-Duc had become a celebrity, moving on to even larger projects like the restoration of the entire walled city of Carcassone. The cost of the cathedral restoration had been estimated at 2.6 million francs; in the end, it exceeded 10 million.

#historical preservation#restoration#viollet le duc#medieval architecture#gothic cathedral#nôtre dame#paris

23 notes

·

View notes