#102nd Battalion CEF

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

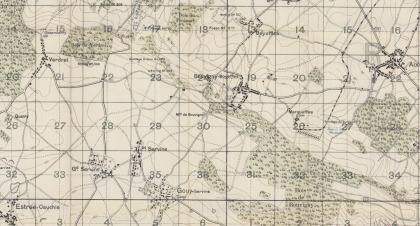

Bouvigny Huts.

Bouvigny Huts.

The precise location of the camp has not bee determined. Note the Bois de Bouvigny at grid 32. For reference Lens is almost due East 12 Kms to city center.

Those two words may have spelled mixed feelings with the Battalion. This would be the first time they ware billeted there but other battalions of the Canadian Expeditionary Force reported the conditions for this facility in the rear as “…life in the trenches was less irksome and monotonous and no more beastly than in places like Bouvigny Huts.”[i] It appears at odds with the common conception that the further back from the line a unit it was, the safer it was. But several incidents in the Battalion history would not bear this out.

It was at Bouvigny Huts that one such event occurred and will be viewed through the experience of one of the soldiers that was directly affected by it.

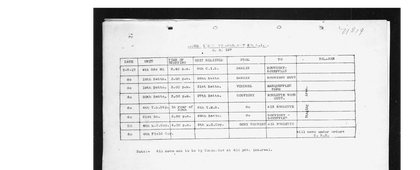

Operational Order No. 127

Operational Order No. 127[ii] from the Officer Commanding the 4th Brigade, 2nd Division of the Canadian Corps would seal the fate of some of the men of the 18th. On July 3, 1917, the order stipulated that the units of the Brigade, of which the 18th Battalion was a member, would move off the line to Divisional Reserve. The orders directed the 18th Battalion to move from the front line at Barlin to Bouvigny Huts. This was an approximately 9-kilometer march and that each company was to maintain a 400 yard interval. The 18th set off 3:00 PM, along with its sister battalion, the 19th. The Battalion had earned some good news, for on July 2, 1917, at a Sports Day held at Camblain-le-Abbe, the Battalion Football Team won the final 2-0 and Private David Sydney Laird won the high-jump.

Arriving that afternoon, the Battalion dispersed to billets and was involved in training on July 4 to 7 inclusive. The Battalion trained on box respirator drill; close order drill; platoon level attack drills involving trench and open warfare. The afternoons were reserved for recreational training, “…including games of all kinds.” There was also a notation that the Corps Commander, General Currie, would visit the Battalion on July 8, 1917, but he actually visited all the battalions of the Brigade on July 7. This was prescient as the next day was rainy, and it appears that all training for the 18th Battalion was called off.

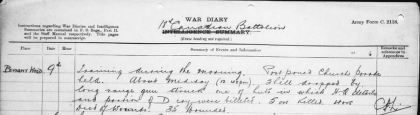

On July 9, 1917, the training continued. The Battalion engaged in its training per the syllabus and at 11:30 AM “sharp” the Battalion began “Battalion drill, with the Battalion Band attending. It ended at 12:30 PM and the men of the 18th returned to their billets, probably glad for a respite, a cigarette, and then lunch before the afternoon’s activities.

It was then the shell struck. A 5.9-inch shell from a Germany gun reached out into the Divisional area and stuck a billet. It wrought havoc as it resulted in 5 men of the Battalion killed outright. Four would die of wounds shortly after, and a further 35 would be wounded to varying degrees.

18th Battalion War Diary entry for incident.

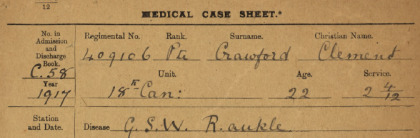

Private Eric Clement Crawford[iii] was one of those men. He, and the Battalion, had a reason to hate Bouvigny Huts. Its reputation may have preceded itself in the minds of the men of the 18th if the rumour mill and purveyors of scuttlebutt had anything to do with sharing local knowledge of the facilities in the rear.

Two sources review this billeting area, giving it a low reputation.

The 102nd Battalion remembers the Bouvigny Huts:

“This was our “job” till the 11th, when we moved back to rest in what was perhaps the worst camp outside of Vadincourt that we ever visited, Bouvigny Huts. It was a nine-mile march to this camp, which was situated in a wood on a hill above Gouy Servins; the weather was bad, the mud intense, the accommodation crowded; the 87th shared the camp with us and for eight days we lingered there with no recreation other than that afforded by one Y.M.C.A. hut which was always packed to the doors. It is a positive fact that man after man when out at rest under these conditions would emphatically declare that he was looking forward to going up the line again because life in the trenches was less irksome and monotonous and no more beastly than in places like Bouvigny Huts.[iv] This is merely a statement of fact and not a criticism of the organization: in view of the number of troops to be looked after and the limited possibilities of accommodation in the whole of the shell-shocked area round Vimy we were lucky not to be sleeping on the ground; but the statement is made to show that life behind the lines was not lived out upon a bed of roses.”[v]

Not only was the camp not “…a bed or roses,” but it was continually subject to German shellfire as this diary entry attests:

“Spent time in same sector. Last trip 28 days in line. Artillery more active. At Bouvigny Huts for eight days. Shelled. Relieved 13th Middlesex for a short time while reliefs were being made. Came into front line on March 20. On HQ, hours 8 – 12 PM. Very heavy gunfire on 21st about 5 PM. On same day Fritz put a shell through church tower at Mont-Saint-Éloi.”[vi]

The shell that exploded that day altered the life-path of Private Crawford.

University College Hospital

By July 12, 1917, Crawford had passed through the intricate organization of the Royal Army Medical Corps and its associated units and had arrived at University College Hospital at London, England. The medical notes outline his condition and treatment[vii]:

Station and Date Disease: G.S.W. R. ankle UNIVERSITY COLLEGE HOSPTIAL

Adm 12/7/17

Died 23/7/17

A very dirty suppurating wound on dorsum of Right Foot at tarsal point.

X Ray Exam: does not show any fractures.

17.7.17 Wound is being washed out several times daily with Dakin’s Solution.

Three [Carol’s] tubes in wound. Right leg in Macintyres Splint. Considerable oedema of soft parts of foot and lower leg.

19.7.17 Temp was up at 104.6 yesterday. Wound examined under anesthetic. A pocket of pus found to extend to posterior of lateral malleolus. An incision was made behind the malleolus and a tube passed.

20.7.17 Wound looks much cleaner today. No pain. Temp down to normal. Pt. [patient] is slightly bronchitic.

23.7.17 Dies of secondary haemorrhage ankle.

His fever, as reported on July 19, indicates an infection, and an operation was conducted to resolve this issue as the doctors must have suspected an infection that was not being resolved by the drainage and the washing of the wounds. The temperature chart shows that Crawford’s temperature appeared to resolve itself after the surgery, but on evening of the 21st his temperature was up to 103.8 degrees F. The notes do not fill in the entire circumstances of his treatment.[viii]

Graphical display of Private Crawford’s temperature, pulse and respiration rates.

At 10:38 PM on July 21, he was haemorrhaging with a temperature of 103.8. The next morning, at 4:00 AM, it has receded to 101 degrees. 12-hours later it rises to 104 degrees and another operation is completed which secured the haemorrhage that had developed from the vanti-tibial [sic] artery. This appears to stop the haemorrhage but another note on the chart at 6:45 AM on July 23, indicates another haemorrhage. He is given intra-venous saline and dies sometime after 10:00 AM that day.

It is not clear from the medical records why the doctors did not amputate but it would appear that Private Crawford’s overall condition, relating to his fever, pulse, and respiration, and other observations, precluded a more radical treatment. The valiant efforts of the doctors and nurses to sustain his life could not stop what would end up being inevitable.

Private Crawford’s grave. BROOKWOOD MILITARY CEMETERY. IX. C. 3. United Kingdom. Source: Find-A-Grave.

Private Crawford, twice wounded during his service, and dying of his second wound, would be buried at Brookwoods Military Cemetery, the largest Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery in England. He does not lie alone, but he is the lone member of the 18th Battalion to be buried here. He is not buried close to his home and his grave sites, perhaps unvisited and unadorned, as one of over 5,000.

From that day over 100 years ago, the explosive force of that German shell transformed the lives of at least 44-men of the 18th Battalion. Private Crawford survived, for a time, to become another one of the many of the Battalion to sacrifice his life.

It has been illustrated that staying at the Bouvigny Huts was dangerous and the billeting accommodation appear to give little protection from long-range German shelling. One wonders if the military authorities made any action to obviate the obvious danger of having the huts located near the Bouvigny Woods? If they did, their methods were not effective or were too late for Private Crawford and his comrades.

After the shelling the Battalion would serve in the Lens sector. Twenty-Five men would die that month, half of the deaths attributable to that one shell. The Battalion would make good its losses and move on to fight in the Battle of Hill 70. But before that it would return to the scene of the tragedy more than once.

The dreaded Bouvigny Huts.

[i] HQ 102 Canadians. (2020). Retrieved 28 September 2020, from http://www.102ndbattalioncef.ca/warpages/102chap5.htm

[ii] 4th Canadian Infantry Brigade diary entry for July 1917 Appendix 1, p. 4. RG9-III-D-3. Volume/box number: 4881. File number: 239. Container: T-10678. File Part 1=1917/05/01-1917/07/31; 2=1917/08/01-1917/08/31

[iii] Private Eric Clement Crawford, reg. no. 409106. This soldier was born in Rugby, England on March 23, 1896. He was a groom and joined the 37th Battalion at Niagara-on-the-Lake on June 11, 1915. He arrived in England and served there until he was transferred to the 18th Battalion, where he arrived on February 2, 1916. He was wounded by a GSW in the back on September 15, 1916 and was admitted for treatment of this wound in France until he was returned to the 2nd Canadian Entrenching Battalion on October 29, 1916. He served with this until he was returned to the Battalion on February 21, 1917. He served with the Battalion until his wounding on July 9, 1917.

[iv] Emphasis mine.

[v] HQ 102 Canadians. (2020). Retrieved 28 September 2020, from http://www.102ndbattalioncef.ca/warpages/102chap5.htm

[vi] Smith, A. (2020). document 62146 | Canadian Letters. Retrieved 28 September 2020, from https://www.canadianletters.ca/document-62146

[vii] It is rare to have medical notes that are legible. Doctors, event at that time, seem to suffer from terrible handwriting.

[viii] Note that this interpretation is from a lay person’s point-of-view. No medical knowledge or expertise is implied by the author.

Killed by Shell Last Name First Name Status Reg. No. Date of Death BURLEIGH WILLIAM RILEY Confirmed 124197 09/07/1917 HOLLAND SANDIESON Confirmed 226580 09/07/1917 MATTHEWS J R Confirmed 54288 09/07/1917 RATCLIFF W Likely 739723 09/07/1917 REED G H Likely 413119 09/07/1917 RIBTON R H Likely 53280 09/07/1917 STEEVES A Confirmed 444599 09/07/1917 WEBB WILLIAM Likely 675541 09/07/1917 SMITH A Likely 424389 10/07/1917 CRAWFORD C E Confirmed 409106 23/07/1917

“…because life in the trenches was less irksome and monotonous and no more beastly than in places like Bouvigny Huts” Bouvigny Huts. Bouvigny Huts. Those two words may have spelled mixed feelings with the Battalion. This would be the first time they ware billeted there but other battalions of the Canadian Expeditionary Force reported the conditions for this facility in the rear as “…life in the trenches was less irksome and monotonous and no more beastly than in places like Bouvigny Huts.”

#102nd Battalion CEF#5.9 inch shell#BARLIN#billet#Bios de Bouvigny#Bouvigny Huts#Brookwood Military Cemetery#Dakin&039;s Solution#General Currie#German Artillery#haemorrhage#Killed in Action#McIntryre&039;s Splint#Operational Order#Recreational Training#shelling#suppurating wound#Training Syllabus#University College Hospital London England#Wounded in Action

0 notes