#(no offense Lancet we all appreciate what you do)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Inquiring minds want to know! Have you seen Lancet-2 in her swimsuit? The yellow one with the float?

her what

#her??? swimsuit?#what#you have to be messing with me here#she's an orb on wheels#(no offense Lancet we all appreciate what you do)#ignoring the fact that she doesn't have limbs or anything#(unless you count her nozzle)#why would you put a swimsuit on a robot who#hold on.#no this totally sounds like something Closure would do#it's real isn't it.#all my misdeeds come back to haunt me#arknights irl

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

“At a June campaign stop in New Hampshire, Williamson argued against mandatory vaccination, calling it “Orwellian” and “draconian.” “To me, it’s no different than the abortion debate,” she said. “The US government doesn’t tell any citizen, in my book, what they have to do with their body or their child.” She apologized for these comments in a subsequent statement, claiming she personally supports vaccination, but she has a long history of promoting skepticism on the subject (something Trump has done as well).Anti-vaccine sentiment is easy to spread through social media and difficult to rebut once it takes hold. The more Williamson’s views get attention, the more validation she gets, and the more likely it is that she’ll contribute to the problem — convincing individual parents that it’s okay not to vaccinate their children, which weakens herd immunity and makes outbreaks like the recent measles emergence in New York more likely.

Moreover, as the Washington Post’s Gillian Brockell notes, Williamson has spread misinformation about illness more broadly. In her book A Return to Love, Williamson wrote that “sickness is an illusion and does not exist,” and that “cancer and AIDS and other physical illnesses are physical manifestations of a psychic scream.” She advised her followers that “seeing sickness as our own love that needs to be reclaimed is a more positive approach to healing than is seeing the sickness as something hideous that we must get rid of.”

Elsewhere in the book, she insists that she’s not saying people shouldn’t take medication. But the upshot of these passages seems to be that people with cancer or AIDS can will themselves back to health. Williamson’s denial “that I ever told people who got sick that negative thinking caused it” is hard to square with the quotes from her book, part of a habit of obfuscating and downplaying her worst statements when called on them during the campaign.

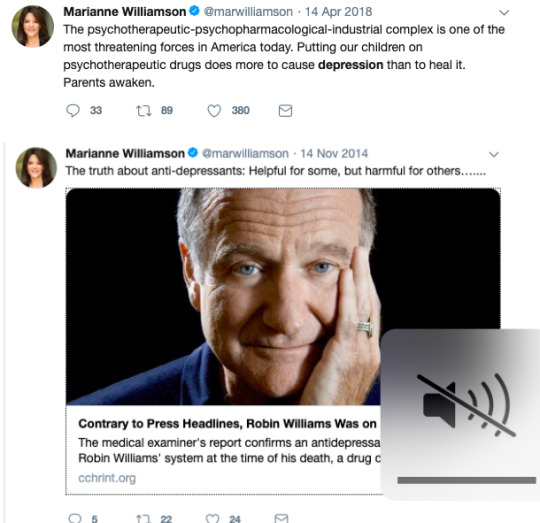

But the rhetoric that bothers me the most — on a visceral, personal level — is Williamson’s repeated attacks on antidepressants.Williamson has repeatedly cast doubt on the idea that clinical depression is real, calling the idea “such a scam” in an interview with actor Russell Brand and labeled antidepressants harmful, a cause of suicide rather than a cure for it. Here’s a sampling of this rhetoric compiled by podcast host Courtney Enlow:

http://twitter.com/courtenlow/status/1156527208544034817

Williamson has apologized for the “scam” comment and tried to walk back some of the more heated tweets. She also argued that her issue is not with using antidepressants per se, which she claims to at times support, but rather with their overprescription of them.

But her rhetoric has for some time gone way beyond such reasonable concerns in a way that makes her walkbacks ring hollow. She has argued that antidepressants are often actively harmful, suggested that they caused Robin Williams and Kate Spade to kill themselves (there’s no evidence for either claim), and has insinuated that Big Pharma is pushing antidepressants on Americans who don’t need them.

Now, there is serious debate among mental health experts on just how effective antidepressants are and whether they’re overprescribed. And Williamson is correct to say that people sometimes get diagnosed with depression when they’re actually just sad, and that antidepressants aren’t a cure-all for sicknesses of the soul. But her rhetoric has at times crossed the line into more pernicious territory, casting doubt on the value of taking such drugs altogether.

There’s clear evidence that antidepressants can help at least some patients; a 2018 meta-analysis in The Lancet that surveyed 522 separate trials conducted on a total of 116,477 individuals confirmed that “all antidepressants were more effective than placebo.“ The trouble for patients with clinical depression is a lot of them don’t want to get help: Mental illness is still stigmatized by a lot of people.

I know this is real because I’ve lived it. Starting around 2014, I started to suffer from clinical depression. Depression makes even the smallest effort, like calling a psychiatrist’s office, feel like climbing Mt. Everest. Nothing seems like it will work; everything seems destined to fail.

I’m better now — not cured, but better. Medication helped me improve, and it helps me regulate to this day. But when I was really in the ditch, anything that fed what my depression was telling me — nothing you can do will make you better — would have erected another barrier to getting help. I didn’t encounter Williamson-type arguments during my worst time, but it’s easy for me to see how this kind of rhetoric could serve as depression’s agent, worming into a depressed person’s brain in a way that might cause them to avoid something that could literally save their life.

This isn’t just my anecdotal experience but the view of actual mental health professionals. “Mental health experts say comments like [Williamson’s] can increase stigma and make people less likely to seek treatment, even if that is not the intention,” Maggie Astor writes in the New York Times.

Marianne Williamson isn’t funny or charmingly weird — at least, not after you think about her for a bit. The effect her rhetoric could have on vulnerable people is scary.

Let’s be clear about something: There’s almost no chance that Williamson is going to win the Democratic nomination in the same way Trump won in 2016. She’s not nearly as famous as Trump was, not polling well enough, and can’t tap into base racial grievance the way Trump can.

But just because she won’t win doesn’t mean she can be treated as a funny sideshow.

When a presidential candidate gets massive media attention, there is always a surge of interest in what they think and believe. Their past writing gets read more, they get more chances to spread their ideas via America’s biggest megaphones, and they can even parlay their post-candidacy notoriety into more impressive and high-profile positions.

What this means, in Williamson’s case, is a greater opportunity to attract more followers and adherents to her worldview. It’s not that she’s bringing up her dodgy ideas about depression and vaccines in debates — at least not yet — but rather that all the people who are Googling her after watching the debate or reading a positive article about her performance are likely to encounter her old rhetoric for the first time. They’ll hear her past lines about how it’s okay not to get vaccinated, how “sickness is an illusion,” and how antidepressants are dangerous and pushed on you by Big Pharma.

The more people hear these things, the more likely people are to believe them. The media’s elevation of Williamson gives her a significantly greater set of opportunities to influence people’s views on health in a potentially harmful manner.

This is irresponsible. I get that she’s funny and kooky, and even sometimes says things that make sense (like the need to confront the emotional character of Trump’s racial appeals). She’s getting a lot of attention from the public, giving every media outlet — including Vox — an incentive to cover her. But none of that outweighs the potential damage she can do to real lives by giving parents license to skip vaccination or convincing a person with depression that they don’t need to take their meds. Elevating Williamson, especially through favorable coverage, subtly mainstreams these views.

Even more fundamentally, it suggests that a lot of the mainstream media hasn’t learned the lessons of 2016.

One of the key reasons that Trump was able to break from the GOP pack so decisively is that he absolutely dominated press coverage. His persona was undeniably entertaining, his substantive views equally offensive — both of which generated large TV audiences and clicks for news websites. One 2016 study found that Trump got nearly $2 billion in free media during the primary season alone, due to the inordinate press focus on him.

One of the media’s cardinal failures in 2016 was giving Trump, an ignorant and dangerous candidate, far more attention than he deserved — because he was entertaining and almost no one thought he could win. What happened afterward is a lesson in American journalism’s failure to appreciate the importance of its gatekeeping role in the country’s political system.

Williamson is a test of what, exactly, the mainstream media has learned from the Trump debacle — and it’s one that many are failing.”

4 notes

·

View notes