#(* VnC comes off as a lot more deliberate which makes sense)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ig sort of my thesis for the sum total gender discourse within PH is it mostly comes off as very off the cuff

#logxx#Aside from the obvious exceptions most of the stuff it ends up saying about gender or sexuality comes off as like#Bc the author clearly thinks abt these subjects a lot and has very complicated feelings abt them#Her work (which comes off as strongly influenced by personal history and introspection) ends up making statements abt gender#But the work overall* doesn't come off as deliberately feminist or anything As Such#(* VnC comes off as a lot more deliberate which makes sense)#Saw post talking about how The Fact of Relationships is moralized in PH and my grievance w it is like#You're not wrong but ''Loving Someone is morally neutral'' is kind of the least interesting analysis of that topic#Mostly bc I don't think PH rly attempts to reject any alternative hypothesis#And even goes so far as to parody like. Conventional heteronormative depictions of the subject#PH *IS* interested in the fact of loving other people but not rly in the morality of the action itself#And in general is more interested in how power dynamics affect relationships including between people who love each other

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why does Alice character deteriorate through the story? She seems to get progressively dumber as the story continues, which is a shame.

So my immediate response to this is “Jun Mochizuki’s internalized misogyny” and then I thought about it a bit more and my answer is actually still “Jun Mochizuki’s internalized misogyny” but with a bit more nuance than that.

Alice... has a pretty strong character, actually. Generally what makes characters weak is their lack of nuance or role in the plot, but Alice as a character actually has a ton of nuance and is one of the most plot important characters in the series, such that her actions are a direct cataclysm for a ton of major events.

Just the other day I was thinking about the scene where Oz first realizes he is a Chain-- while the scene is from Oz’s perspective, and thus the emotional narration is his own, that scene is also absolutely devastating if you consider it from Alice’s perspective. It’s unclear how much Alice understood about the nature of Oz’s existence (at least at the time of the memory) and how much was simply a child treating a toy like a person because that’s what children do, but that doesn’t change the fact that Oz was... an object, incapable of acting on his own. Alice definitely knew this, at least on some level (she never claims that Oz isn’t a toy, even after Jack “kills” him)... so the fact that she feels the need to ask Oz to protect her, to comfort her when she’s sad, that there is no one else she could possibly turn to for this was enough to make me feel weird for a good while after I realized the scene’s full implications.

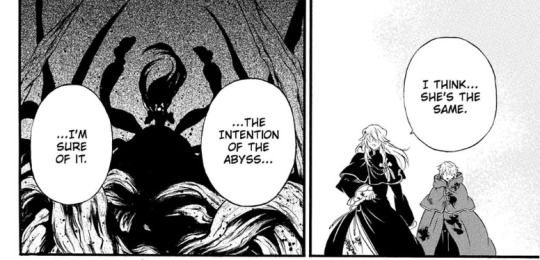

There’s way more I could write about Alice’s character, because there is genuinely a lot to her (that Alice’s Most Important Person, in terms of the narrative device central to PH’s themes, be the Intention of Abyss instead of Oz as is commonly assumed is one thing I’ve brought up). Her dialogue is just... overwhelmingly stupid.

The deterioration in quality wrt her dialogue is something I blame on Jun Mochizuki’s internalized misogyny, as I said, but I realized that might sound a bit weird given how PH does actually have a ton of strong female characters. I’ve written a ton about Lacie/Noise/Echo’s respective arcs and narrative roles before, and they’re not the only female characters in PH to have strong writing. The thing is mostly that... Jun Mochizuki has (or had, because this problem is WAY less present in VnC, good on her) a very tough time writing female characters outside of the context of abuse. All of the female characters I just mentioned were abused their entire lives, with Noise and Echo only finding catharsis immediately before their deaths and Lacie not finding catharsis until over a century after her execution (though she definitely found catharsis, and I am staunch on this, and that’s a whole other post).

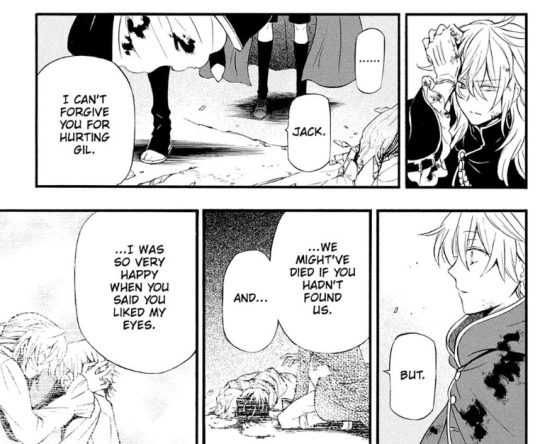

The thing about Alice is that, while she was certainly mistreated quite a bit as a child, for most of the plot she... is not actively subjected to abuse. She has her conflict with Gil, definitely, but he certainly wasn’t an abuser, she probably didn’t realize the conflict was anything more than petty for him, and the two reconcile pretty easily after Gil takes it upon himself to apologize. Other than that, the only character she stands in major direct conflict with for most of the story is Intention of Abyss, who only has a few appearances overall, and with whom she pretty quickly resolves her conflict once she comes to understand her true feelings for her. There is no pervasive negative force acting against Alice for most of her arc, and because of that, Jun Mochizuki had trouble keeping her characterization strong.

“Strong characterization only in the face of horrific, ongoing outside adversity” is something I assign specifically to female characters mostly because... well, most of the male characters don’t have the same kind of horrific ongoing outside adversity the female characters do, at least to the same degree. Gil is the most obvious example, especially in the sense that he’s a character Jun Mochizuki clearly personally favors because his actual role in the plot is... minimal. Most of his purpose in the plot is fulfilled by the time he’s a small child, and his role in the plot otherwise is mostly... be Oz’s friend, which obviously isn’t something only he could do. The only thing I can think of that is genuinely exclusive to him is that he is Raven’s contractor, and even then, there’s no real reason why he couldn’t have, say, died immediately after escaping Abyss, in which case Nightray still would’ve been without a Chain for the past 100 years.

Gil, for the most part, doesn’t have a character working in direct conflict to him. The closest is Noise, who... actually ends up not saying much about him, even though she canonically disliked him personally. You could argue that Vincent serves this role, but Vincent makes a deliberate effort to stay out of Gil’s way for most of the plot, and while they definitely had a major incongruence in ideals, to say Vincent was working against Gil gravely oversimplifies their relationship, to say the very least. As I said before, his actual plot relevance is pretty minimal. Yet Gil still has incredibly strong characterization-- he’s my favorite male character, for all the shit I give him!-- because Jun Mochizuki is capable of more than convincingly sustaining his arc off of his internal conflict alone. Despite not doing much and having comparatively little external conflict, Gil still comes off as a very strong, nuanced character, because we’re given the chance to see his internal conflict throughout the story.

I don’t know why Jun Mochizuki chose not to give Alice this same internal conflict. Part of me suspects it was at least a little bit because she didn’t want PH to get too down in tone-- keep in mind, at the start of the story, Alice had several angsty perspective bits while Gil was mostly comic relief, before their narrative roles switched. But I don’t think that excuses Jun Mochizuki letting one of her central protagonists have such comparatively weak writing, given that we know she’s an incredibly nuanced and talented character writer. It seems more than anything her reluctance to write female characters who aren’t being actively victimized being what caused Alice to have such frankly stupid dialogue, which really is a shame, because I like Alice, and I do think she has nuance.

#pandora hearts#PH SPOILERS#. SPOILERS FOR PANDORA HEARTS#LIKE. END DETAILS AND SHIT#answers#aniblogging#long post#ph#mochijun#animanga#OP I am you#Basically I do like Alice I think there is a lot to her writing it's just her dialogue is fucking stupid#And Jun Mochizuki's hangups about womanhood is why#Anonymous

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

honestly love hearing what you have to say about vnc youre the only one who is Right <3

Thank u !!

I think Vanitas does better than PH in a number of dimensions- it’s far better paced, the battles aren’t boring as all hell, it’s far more approachable in the “not making all of its characters terrible dysfunctional people” department, it actually has visibly nonwhite and canonically gay characters... etc. From how it’s written, the distinct impression I get from it is Mochizuki making a deliberate effort to make up for her past mistakes with PH, while still building on a lot of the same fundamental themes, and pushing her limits as a mangaka. Vanitas is, in general, a far more maturely written story, in the sense that it reads as though Mochizuki has become far more used to being a writer.

I think one dimension it tried to tackle with this was how Pandora Hearts handled sex. PH is by no stretch of the imagination a politically conservative story (the single cathartic moment of lethal violence in the entire series is when a girl kills men attacking her for being a member of a minority, in case it wasn’t blatant from... all of its themes, in general) and it goes out of its way to never demonize the desire for romance. But... think about how PH depicts sexuality, what characters have or have had sex, the circumstances surrounding that... and the thing is, PH kind of comes away with the implicit idea that sex is kind of evil. Far more often than not, sex is used as a tool of violence, either against oneself or against others. People aren’t portrayed as evil for having sex, definitely, but the act of sex itself is handled with a LOT of apprehension.

Vanitas, on the other hand, seems to be... trying? To not say that? The best example of this is with Dominique, who is shown to be extremely flirtatious upon her introduction. She may not have ever explicitly had sex, sure, but she’s twenty, has dated a lot of people, and seems to be fairly confident in her sexuality. She’s embarrassed when Veronica tries to tell her about her sex life, but that’s portrayed as a matter of... well, Dominique does not want to hear about the details of her sister’s sex life, because she’s a fucking normal person. Sexuality in Vanitas is a much more overt and prominent theme in VnC than it is in PH (though sexuality is still a pretty prominent theme in PH), and VnC in general creates an atmosphere that the adult characters are probably having or have had adult relationships in which sex was involved.

What judgements should be made about this? We’ll have to wait and see- I certainly couldn’t have predicted the direction Pandora Hearts would take its themes when it was at the point Vanitas is at now. How Vanitas depicts sexuality gives me the DISTINCT impression it is deliberately written with the fact that it is the first romance/s of several traumatized, emotionally stunted people in mind. Vanitas and Jeanne are specifically pointed out to have extremely unhealthy views on relationships and sex as a consequence of their abuse. Noé is too distant from his own emotions to distinguish romantic feelings, and it’s safe to say that if and when he does realize such feelings exist, he’s not going to handle it too great (remember the last time he got really fond of someone?) Dominique probably has the healthiest relationship to sexuality of the main cast, being the only character to have actually been in romantic relationships prior to the events of canon, but even she clearly has some pretty big hangups regarding her superiority/inferiority complex towards anyone she has romantic feelings towards (see how she constantly tries to assert dominance over Noé and Jeanne, while her internal narration goes on about how they’re so much better than her.)

I think it COULD work very well. It’s GOOD to see a story about coming into one’s sexuality that isn’t about literal children, especially a shounen manga. Mochizuki likes writing characters who the audience are supposed to sympathize with but (at least by the end of the story) understand as completely wrong. The blunders the main characters make in navigating their relationships could make for a very good story, one I think should be represented more often. That said...

I’m simply not confident that Mochizuki herself has a healthy enough view of sexuality to pull it off. The thing is, like Pandora Hearts, Vanitas disproportionately represents unhealthy sexuality over healthy sexuality. We’ve yet to see an unambiguously healthy romance between two named characters. Even scenes that aren’t in themselves really supposed to be about sexual violence often have an element of sexuality to them added (see: Chloé and Faustina) because... well, sex is scary. If Mochizuki intends to pull a plot like this off, she’ll need to have addressed her own hangups with regards to sex in order to do so. I think it’s too early to call whether or not she has, but it makes what’s going on really up in the air.

Either way, though, I’m really fond of Vanitas’s characters, art, and overarching plot. I think it’s an extremely good manga and Mochizuki is an extremely good writer. I just hope her decision to make sexuality as prominent a theme as she did in it was a good one.

#mochijun#animanga#vanitas no carte#answers#logxx#meta#long post#Idk VnC is about some really fucked up young adults who are just beginning to figure out their sexualities#And it's extremely written like that#It could work very very well#But I think it's too early to make a call at this point#... and tbh I'm not the most confident it will#Anonymous

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

I think VnC’s treatment of female characters is better than in PH, where most of them were props, tools to further the development of males, *coughLacieyoudeservedbetter*, tools to humanise the males *coughAdayoucan’tfixhimwithlove, endlessly forgiving and impossibly saintly *coughreallyAlyssyou’rejustgonnaforgiveJacklikethatyouarenotangryatall??*, amongst other problematic tropes.

VnC’s treatment of female characters is absolutely better than PH’s-- in fact, I’d say VnC was one of the few shounen manga to consistently treat its female characters with the same passion and respect as its male ones. One thing I say often is that VnC feels as thought it was written with Mochizuki having acknowledged PH’s problems (the complete lack of nonwhite characters, the continual mistreatment of female characters, the at times facetious treatment of issues such as incest or pedophilia which is... Not A Fan) and to that effect, I think she is making a deliberate effort to make multiple female characters with their own arcs which exist outside of men, who have important relationships with other women, who are capable of agency in the same capacity as their male counterparts.

This post isn’t really about VnC though so I’m not gonna sing its praises much anymore. I’ve talked before about how, despite being written by a woman, despite clearly acknowledging misogyny as a chronic problem among violent men PH is... not especially self aware when it comes to the misogyny of its own narrative.

I’ve made my thoughts on Lacie clear before (see here) and particularly how I believe her treatment was one of the times where PH’s treatment of women was particularly remarkable in that it’s good, despite her arc being drenched in misogynistic abuse and violence. I absolutely wish that the atrocities pinned on Lacie being not her fault was made more clear (aside from what I said in the post, and Oz saying that Lacie would never desire for the destruction of the world she loved) but I don’t think her writing itself was misogynistic-- I’d even go as far as to say it was feminist, though, obviously, I’m open to disagreement.

What most certainly does piss me off, however, is the writing of Ada’s arc. Yesterday I joked about Ada being the ‘anti-Lacie,’ and while it was a joke, I still intended some seriousness with it. Unlike Lacie, who was forced to constantly reevaluate her morals and the positions of her and her loved ones as a person whose existence was an inherent sin and who was abused throughout her life, Ada’s arc is built around the fact that she has never had to question anything. Similarly, while Lacie’s arc is about how she sought her own agency despite being surrounded by and allowed only those who were at best complacent in her suffering, Ada’s arc is about how... she continually sought out and apologized for a misogynistic predator despite being surrounded by better options.

The gender of the Core of the Abyss is something which I think warrants a separate post, but the official translation refers to the Core as being female, and for nearly the entire story she takes the form of a girl. Lacie reached out to an entity referred to and most often perceived as female, sought to understand her, and was abused as a specific consequence of this. Ada, meanwhile, made no real attempts at sympathy for her female counterparts. She never sought to question the circumstances of Noise, or Echo, or their relationship with Vincent. She gave forgiveness for crimes she had not been affected by nor did she even understand; her defense of Vincent was done not out of concern for Noise’s psyche but out of unquestioned pity for her abuser.

Ada’s arc bothers me for its utter lack of agency. She was a teenaged girl, expected to fix a predatory, abusive man in his twenties, and throughout her arc she is given no real means of choosing other options nor protecting herself. Her decision to defend a predator was not even an educated one; she simply did not know. Nor did she ever really come to understand anything about Vincent, aside from brief glimpses into his past. Ada is dragged around by the plot, pursuing an abuser she did not know was an abuser yet still felt sure she could heal, being forbidden from choice-- where she was not denied choice in the sense that she lacked the knowledge to make one, she was denied choice via other characters forbidding her. She was not allowed to protect Vincent though she wanted to because Vincent felt it was too dangerous to allow her to, she was not allowed to remain beside her friends and family though she wanted to because they felt it was too dangerous to allow her to, she wasn’t allowed to stay with Vincent because it was too dangerous, she wasn’t allowed to see him again because it was too dangerous... and she’s never given the choice to do anything but go along with it.

Alyss’s forgiveness of Jack is... a more complicated issue. That Ada “forgive” Vincent-- along with many of their other interactions, I might add-- felt utterly meaningless to me. Ada had never really perceived Vincent as performing a slight against her, being perfectly willing to assign any violence he committed against her as either her own fault, or part of his mental illness, thus Not His Fault. That Alyss forgive Jack, who was violent towards her, who she understood as victimizing her and others... I don’t like it, exactly, but at least it’s not the same.

I’m not sure “forgive” is even the correct word for what she did-- she acknowledged him, and she was gentle, but she never told Jack that she forgave him. Vincent’s dialogue during Retrace CIII supplements this in saying he suspects that Alyss’s feelings for Jack are the same as his own.

Vincent feels unable to either forgive Jack nor reject him entirely, feeling that he had done too much good for him to ever really hate him. Alyss, similarly, felt too strong a love for Jack to reject him outright. She never expressed sympathy for his actions, nor did she make any attempts to defend him. There was no misunderstanding on Alyss’s part on whether her love for Jack was unhealthy, but she loved him nonetheless. When she finally “finds” him, she offers no words of kindness. She simply expressed her gratitude in having done so before calling him a hopelessly lonely man, making no further attempts at even acknowledging him.

Of course, there is the inherent misogyny of a character arc about a young girl infatuated with an adult man, to the point of destroying her other relationships in pursuit of it. That Alyss was deliberately isolated and that Jack be the only person aside from the other Alice and the Core of Abyss-- two entities that cannot be meaningfully separated from herself-- is an obvious contributor, but that does not erase the problematic aspects of her arc. Then there’s the matter of Alyss’s wish to die being the only one treated as though it was a necessary evil, as opposed to a reflection of the individual’s personal instability that should be addressed through supporting them as opposed to killing them. It’s sort of an unfair double standard, and that the plot make Alyss’s death a necessary evil is a matter of author choice, not something inherent to the work.

On the topic of other instances of misogynistic writing in PH as a whole, there’s the matter of Alice and Sharon’s arc. While I don’t think either arc is in itself misogynistic, both characters are totally ignored in favor of their male counterparts. Despite Alice being one of the most important characters in the series, she has almost no narration and is frequently characterized as, to quote a friend of mine, a “feral animal.” She’s not given the same emotional or psychological depth as Oz or Gil, despite having around the same number of appearances and being the plot’s catalyst. Sharon has her own arc, theoretically, but we only ever see it within the context of Break or Reim despite being more of a main character than the latter. That Sharon spend entire volumes not appearing a single time is a recurring joke. A major part of her characterization-- that she feel insecure in relationships due to her halted aging-- is not revealed until the last chapter of the comic. Her arc ends with her marrying to a character who... I wouldn’t have been upset if the two of them had had any real interactions outside of Break, but they didn’t. There’s no inherent problem with their relationship except it’s boring and rushed.

Then there’s the matter of the sheer number of female versus male characters whose purpose in the plot is to die violently-- the Flower Girl, Vanessa Nightray, Bernice Nightray, Miranda Barma, Mary, etc. All of these characters did little or nothing to actually progress the plot, and all are murdered by a male character with the exception of the Flower Girl (who is a sex worker in the anime adaptation, and while I don’t know the canonicity of that, I feel it worth mentioning).

Ultimately, PH suffers a lot for Mochizuki’s internalized misogyny. Her narrative seems over eager to forgive perpetrators of misogynistic violence, and in many ways over eager to characterize sympathetic men as misogynists. A Pandora Hearts without its themes of misogyny seems... nearly incomprehensible, though that’s in large part because of how meticulous the narrative as a whole is. The improvements Mochizuki has made subsequently, though, are noticeable and greatly appreciated.

#pandora hearts#answers#gisellehexen89#OP I am you#ph spoilers#abuse ment#This is REALLY long so I put it under a readmore#Pandora Hearts huh..........#ph#mochijun#animanga

18 notes

·

View notes