#🇲🇽food

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

Source

#🇲🇽#my saved tiktok videos#indigenous#native#mexico#canada#usa#united states#native american#food#immigration

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

IM SORRY. REINO ATE THAI FOOD. IN FINLAND????? YOU ARE IN FINLAND????? AND YOU DECIDED TO EAT THAI FOOD????????

#txt#absolutely astounded#ASTOUNDED#its funnier that sasha recommended him a place too#i think the gag of ordering another countrys food while visiting a country with good cuisine is so-#its funny its astounding i dont know what to say#i mean ive got good stories of ordering 🇲🇽 food in 🇦🇷 which is already funny just from the getgo#because my countries spice tolerance is actually dreadful no one can handle even a little jalapeño anyways real fun i ordered the#spiciest thing on the menu and the linecook leaned over and was about to say no but then the guy who took my order was like nono they can#handle it because i said an english word weirdly#(to them. i codeswitched without realising it. think of the TOHOU PROJECT toby fox meme. like that)#and he got tipped off immediately i wasnt a native and the thought process here is oh youre not from here you can definitely handle spicy#i got home ate it and it was good but my tongue didnt even tingle at all like i forgot it was supposed to be spicy at all

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

*puts a bowl of grapes and lettuce leaves under a cardboard box held up by a stick*

no mames… sería una lástima desperdiciar comida

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey crimson!! can you tell me something sweet that kento has done for you lately 🥹🩷

ps. happy sunday! hope you’re having a good day!

Hi Mimmy!!!! ♡ i answered this late and it’s not Sunday anymore but!! I think I did have a decent sunday lol I hope you’re having a great day too!!!! ♡ ♡

Something sweet I keep fantasizing about Kento doing for me and bringing me some pan dulces as a surprise 🥺 I’ve been craving them for a while lol. Also bringing me some tamales. Maybe some mole too 🤤 Any Mexican food tbh bc I’ve been craving it like crazy lately lmao. He’s bringing me a whole Mexican feast bc he knows I’ve been craving it, and he wants to try it too! Wants to know my culture’s food hehehe ♡ he’s just pampering me with food and cooking it all himself too bc he cooks it with love 🥺 the most important ingredient hehehe 🤭 i may also just be really hungry LMAO!

#he’d cook all so well too 😔💛#marrying him for that#and he’ll say ‘we’re already married’#and I’m like ‘yeah! but I wanna do it again 🙄 bc you’re just that amazing!!’#and he’ll laugh and kiss me hehehehehe (。+・`ω・´)#I want him to cook for me so bad….#that’s the sweet thing he’s done for me lately#cook me food#💞💛🫔🇲🇽🌯#crimsonkenjii answers#selfship shenanigans

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

@filmflam-and-nonsense

enough toxic masculinity I'm ready for salubrious mexicanity. I'm ready for a social movement that encourages (esp straight, cis) men to indulge in things that make them more joyful, emotionally healthy, and help them strengthen not core muscles but core compassionate communication skills.

#you heard it here folks#masculinity is out— mexicanity in I N#TBF tho— Mexican food is very healing#bitch— time to bring out the champurado and the asadas#you can never say that we don’t know how to have a good time baby#🇲🇽

64K notes

·

View notes

Text

This month’s Treats box is on Mexico. They’ve done Mexico a few times, but I think there are some ‘new’ things. The postcard’s of Kukulcan Pyramid. This month’s recipe is salsa and chips. Really 2 in 1, because they have you make the chips from scratch along with the salsa. I had the Pintera Nuts with my snack today. It was not really spicy, just a slight burn. (More than I expected though.) I threw out the Takis, since I can’t have spicy food. I’m curious about the Queso Ruffles chips. I think I’ve seen it at Safeway, but I didn’t know if it’d be too spicy. I like queso dip, and it’s supposed to be based on that. I might like it and get it again in the future.

#snacks#international#box#monthly#subscription#monthly subscription#monthly subscription box#mexican food#mexican snacks#🇲🇽

0 notes

Note

One day I will visit North America and then I'll have a taco lmao. Restaurants don't sell them here!

Yay!!! Do NOT go to Taco Bell. That is NOT real Mexican food. No matter where you go and it destroys your stomach, you'll be in the bathroom for hours.

#anti taco bell#taco bell#fucking hate the shit#thought i hated mexican food until i dated someone mexican and had tamales that changed my LIFE#also carne asada my beloved 🇲🇽

0 notes

Text

Forbidden Fruit! Inside Mexico’s Anti-Avocado Militias Michoacán

The Spread of the Avocado is a Story of Greed, Ambition, Corruption, Water Shortages, Cartel Battles and, in a Number of Towns and Villages, a Fierce Fightback

— By Alexander Sammon | Tuesday 11June 2024 | The Guardian USA | Harper’s Magazine

An Avocado Farm in Yoricostio, Michoacán. All photographs from Mexico, August 2023, By Balazs Gardi for Harper’s Magazine © The artist

Phone Service Was Down. A fuse had blown in the cell tower during a recent storm. Even though my arrival had been cleared with the government of Cherán in advance, the armed guard at the highway checkpoint, decked out in full fatigues, the wrong shade to pass for Mexican military uniform, refused to wave me through. My guide, Uli Escamilla, assured him that we had an appointment and that we could prove it if only we could call or text our envoy. The officer gripped his rifle with both hands and peered into the windows of our rental car. We tried to explain ourselves: we were journalists writing about the town’s war with the avocado, and had plans to meet with the local council. We finally managed to recall the first name of our point person on the council – Marcos – and after repeating it a number of times, we were let through.

To reach Cherán’s militarised outskirts, we had driven for hours on the two-lane highway that laces through the cool, mountainous highlands of Michoacán, in south-central Mexico. We passed through clumps of pine, rows of corn and patches of raspberry bushes. But mostly we saw avocado trees: squat and stocky, with rust-flecked leaves, sagging beneath the weight of their dark fruit and studding the hillsides right up to the edge of the road. In the small towns along the way, there, too, were avocados: painted on concrete walls and road signs, atop storefronts and on advertisements for distributors, seeds and fertilisers.

Michoacán, where about four in five of all avocados consumed in the United States are grown, is the most important avocado-producing region in the world, accounting for nearly a third of the global supply. This cultivation requires a huge quantity of land – much of it found beneath native pine forests – and an even more startling quantity of water. It is often said that it takes about 12 times as much water to grow an avocado as it does a tomato. Recently, competition for control of the avocado, and of the resources needed to produce it, has grown increasingly violent, often at the hands of cartels. A few years ago, in nearby Uruapan, the second-largest city in the state, 19 people were found hanging from an overpass, piled beneath a pedestrian bridge, or dumped on the roadside in various states of undress and dismemberment – a particularly gory incident that some experts believe emerged from cartel clashes over the multibillion-dollar trade.

A Sculpture of an Avocado at the Town's Entrance in Ziracuaretiro, Michoacán. Photograph: Marco Ugarte/AP

In Cherán, however, there was no such violence. Nor were there any avocados. Thirteen years ago, the town’s residents prevented corrupt officials and a local cartel from illegally cutting down native forests to make way for the crop. A group of locals took loggers hostage while others incinerated their trucks. Soon, townspeople had kicked out the police and local government, cancelled elections, and locked down the whole area. A revolutionary experiment was under way. Months later, Cherán reopened with an entirely new state apparatus in place. Political parties were banned, and a governing council had been elected; a reforestation campaign was undertaken to replenish the barren hills; a military force was chartered to protect the trees and the town’s water supply; some of the country’s most advanced water filtration and recycling programmes were created. And the avocado was outlawed.

Citing the Mexican constitution, which guarantees Indigenous communities the right to autonomy, Cherán petitioned the state for independence. In 2014, the courts recognised the municipality, and it now receives millions of dollars a year in state funding. Today, it is an independent zone where the purples and yellows of the Purépecha flag, representing the Indigenous nation in the region, is as common as the Mexican standard. What started as a public safety initiative has become a radical oddity, a small arcadia governed by militant environmentalism in the heart of avocado country.

But the environmental threats posed by the fruit have grown only more pressing since then. In the US, avocado consumption has roughly doubled, while domestic production – mostly confined to drought-stricken corners of central and southern California – has begun to collapse. The resulting cost increases have encouraged further expansion in Mexico, attracting upstarts that are sometimes backed by cartels, whose members tear up fields and burn down native trees to make way for lucrative new groves. Some landholders and corporations are getting very rich. I had come to Cherán to see whether this breakaway eco-democracy could endure in the face of a booming industry.

As We Drove into the Centre of Town, home to 20,000 people, the narrow streets hummed with activity. Colourful murals commemorated various anniversaries of the uprising. Exhortations to protect the earth adorned white stucco walls. Vendors sold mushrooms, vegetables and grilled corn. Stray dogs traipsed through the plaza. We parked in a gravel lot down a sidestreet and began asking around for Marcos. Eventually, a man wearing a parka emerged from a nearby building. As we shook hands, Uli joked about our holdup at the checkpoint, but Marcos didn’t laugh. He scanned the square suspiciously, as though worried we’d been tailed.

A Member of the Community Police Force in Cherán, a town in Michoacán. Photograph: Andrea Murcia/The Guardian

Marcos led us into the town hall, and I followed him up a staircase and came face-to-face with a floor-to-ceiling portrait of Emiliano Zapata, the Mexican revolutionary and champion of land reform. Above the doorways of offices hung photos of Cherán’s own armed comuneros next to photos of pine saplings. In the modest legislative chamber, I took a seat in front of a U-shaped banquet table, where the elected council meets. Half of its dozen members were seated, attending to paperwork. When they saw me, they began a second interrogation, asking what my motivations were and what exactly I was there to see. They squinted at the business card in a plastic sleeve that I was passing off as a press credential, handing it back and forth. Another lifesize portrait of Zapata frowned at me from the wall.

I understood their suspicion. Just weeks prior, the neighbouring state of Jalisco had sent its first-ever shipment of avocados to the US. Violence in the sector was increasing, with reports of drone-bombed fields. A few months earlier, inspectors from the US Department of Agriculture, which verifies the fruit’s quality for export, had received threatening messages. And there were plenty of reasons for avocado groups to size up Cherán: its fertile soil, its abundant water. Besides, what revolutionary regime isn’t a little paranoid?

But the council eventually agreed to show me the full sweep of its operations. I was told to report by 7am for rounds with the patrol unit that surveys the region and wards off threats. Together we would head to the frontlines.

The Avocado has Been Grown and Eaten in Mexico for Centuries. The glyph representing the Maya calendar’s 14th month features the fruit, and Aztec nobles often received it as tribute. “Looks like an orange, and when it is ready for eating turns yellowish,” observed the Spanish coloniser Martín Fernández de Enciso in 1519. “So good and pleasing to the palate.”

For the better part of the 20th century, however, the fruit failed to catch on. Among the challenges faced by marketers were the fruit’s many names: alligator pear, aguacate, avocado, Calavo – the last a portmanteau of California and avocado. (The name in Nahuatl, an Indigenous language, ahuacatl, is slang for testicle, and was never really an option.) Money was poured into advertising to fix the problem, and California funded research on farming techniques, though these still didn’t solve for the novel taste. Growing ranks of producers, and the small consumer base, led to ruinous drops in price while costs kept increasing. Water and land got more expensive as new housing developments demanded more and more.

By the late 1960s, only farms that produced more than 5,000lbs (2,270kg) of the fruit an acre each year were profitable. Agribusiness began to look south of the border in the 70s. The California Avocado Society, a collective founded by growers, deployed multiple research missions to Michoacán, where envoys made careful note of the region’s plentiful water. “In this area, water is free,” marvelled their report from a trip in 1970. Local avocado growers’ only concern was “how to divert the water into channels on their property and to get the water to the trees”. At that point, imports of fresh avocados from Mexico to the US were prohibited by federal regulation (established in 1914 to protect California farmers), but the large avocado firms began investing in the region anyway, with designs on selling the fruit elsewhere.

Avocado Orchards in the Mountains of Michoacán. Photograph: Marco Ugarte/AP

The North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta), when it went into effect in 1994, largely kept the ban in place, but crippling droughts and exorbitant land and water costs eventually pushed California’s industries into accepting a slow repeal of protections. Many small domestic growers were facing bankruptcy; the larger firms that weren’t had already invested in Mexico. After decades of malaise, the avocado became a surprise winner, and a cipher of the promise of free trade – “Nafta’s shining star”, as one consultant later put it.

After achieving notoriety as one of the most spectacular commercial food failures of the 20th century, the avocado finally entered the mainstream. Guacamole and avocado toast became two of the most successful gustatory trends of the 21st century, pushed with prime-time Super Bowl ads. Michoacán’s avocado production went from about 800,000 tonnes in 2003 to more than 1.8m tonnes in 2022. Over the same period, the US’s avocado consumption quadrupled.

Today, groundwater in Michoacán is disappearing and its bodies of water are drying up. Lake Zirahuén is polluted by agricultural runoff. Nearly 85% of the country was experiencing a drought in 2021, and experts project that the state’s Lake Cuitzeo, the second largest in all of Mexico, could disappear within a decade. In part because of the conversion from pine to avocado trees, the rainy season has shrunk from around six months to three. So profound is the drain on the region’s aquifers that small earthquakes have newly become commonplace. The 100-mile avocado corridor has, in effect, become the only live theatre of what is often referred to as “California’s water wars”.

It’s unclear whether the avocado can survive this changing climate. But in Michoacán, the more pressing question is whether its residents can survive the avocado.

At 6:45 the Next Morning, Uli and I reported to the town jail, where we’d been told we would find the ronda tradicional comunal, the community police. The ronda – by some counts the town’s largest agency, and the only one for which jobs do not rotate every three years – is tasked with all security, manning the checkpoints, guarding against poachers and even punishing public drunkenness. Through the darkness I could make out a commander meting out orders to officers wearing flak jackets, helmets and fatigues. It was almost time for a shift change. An unfamiliar truck by the sand mine would need to be investigated; everyone was reminded to keep their weapons on them at all times.

The ronda is most heavily armed while guarding the forest. The job is to monitor the entire 27,000-hectare region of Cherán, ensuring that there is no illegal logging, no burning, and no planting of avocado trees. I was assigned to join a unit of four people, each carrying a rifle and handgun. We were headed to the north-east border, where a new avocado grove had recently appeared. But 30 minutes into our drive, the crew were diverted to a new job, which would involve confronting some loggers laying claim to a different patch of forest. Any local loggers could be backed by monied avocado interests, or cartels, the crew told us, and it didn’t take much for bullets to start flying. Our safety couldn’t be ensured, they said, and our seats in the truck would be needed to transport reinforcements. They deposited us back at the jail, where we waited to be assigned to another patrol group.

After a few hours, a second pickup arrived, staffed by a team of three. We loaded back in and headed out of town on a sunken dirt road, up into the mountains. As the truck lurched over potholes, we passed spindly pines – some replanted, others old-growth – as well as another sign, this one in red: the community in general is prohibited from planting avocados.

Avocados in an Orchard in Uruapan. Photograph: Carlos Jasso/Reuters

The truck’s driver, Edgar, had spent eight years in the ronda, enlisting not long after the uprising. He’d done construction work in South Carolina before getting deported. I asked if he’d encountered illegal avocados in Cherán. He said he had. Everyone knows the rules, he told me, “but there is still tension here, even now”. When avocados are discovered, patrols dig up the trees and destroy them. The offending planter will be sent to the town jail, where he’ll be forced to issue a formal apology and pay a fee. A repeat offender can have his land requisitioned by the government.

We drove until the road ran out, then parked above a sweeping hillside. A barbed-wire fence ran along a dirt trench, marking the division with the neighbouring municipality of Zacapu. At our backs were a wall of pines; in front of us, rows of juvenile avocados. The trees grew right to the edge of the muddy border. All of this had been old-growth forest until four years ago, Edgar told me. He pointed to a barren hillside in the distance. Eight months prior it had been full of pines, but it had recently been clearcut, marking the next stage of the forward march. Soon, it too would be covered with avocados.

There Was Something Else Edgar Wanted Me to See if I was willing to venture with him into the woods. We returned to the truck and drove cautiously through deeper and deeper puddles until the trail was completely washed out. We parked, left some nonessentials, and began our trek with three militants in full protective gear.

As we passed into denser forest, the patrolmen sometimes paused to rustle the pine needles blanketing the forest floor, exposing the mushrooms that grow naturally in the area. On occasion, one of them would find a bright orange lobster mushroom, which I was told tasted just like pork. Those were pocketed for dinner. Finally, we emerged into a blackened clearing, which abruptly gave way to a ravine. All around us, the trees and shrubs were charred.

A few months earlier, Edgar explained, this area had combusted. Loggers had been fast at work clearcutting the forest, in anticipation, I was told, of avocados. To expedite the process, they set fire to some stumps, which can be especially flammable in the dry season. The blaze quickly jumped the town line of pine trees and took off in Cherán’s forest. Edgar, along with volunteers and dozens of members of the ronda – 80 people in all – attempted to quell the conflagration.

They dug a perimeter right below where we stood. Having no ready water source, they tossed dirt on to the flames with shovels. Edgar spent three days and two nights on the fire line, long enough for the containment effort to succeed. But the losses continued to mount, as many of the rescued trees succumbed to blight in the weeks that followed. Eventually, the sickly trees were cleared. Four hectares of pines were lost.

Wildfires are a major concern in the region, and an estimated 40% of them are now purposefully set to clear the way for avocado groves. Forests are set ablaze or levelled by chainsaws, quickly and indiscriminately; planters then suture avocado saplings on to the barren earth. Reforestation has since become a critical component of Cherán’s economic strategy. In only a decade, the town has managed to reforest much of the town’s 20,000 hectares with native pines. It underwrites these efforts by selling juvenile pines, bred in a nursery, to nearby landscapers and farmers, and by harvesting pine resin that is used in everything from turpentine to oil to chewing gum. At the town’s mill, dead and diseased trees are turned into two-by-fours for construction, or fitted into wood pallets to be sold to trucking companies.

An Avocado Vendor at a Market in Mexico City. Photograph: Nick Wagner/AP

The reforestation campaign is also a water policy. Recent studies have suggested that the vapours released by pine trees can help seed clouds, substantiating in some sense the folksier notion – which I heard repeatedly – that trees bring rain. The deeper root structure of tall pines also helps convert precipitation into groundwater, providing a pathway for rain to travel to the water table during the rainy season. Avocado trees, short and appetent, are a drain on the water table throughout the entire year. A mature avocado tree demands as much water as 14 adult pines. The forestry strategy, I was told by Edgar and others, was one of the chief reasons that Cherán had been able to escape the water problems that afflict the rest of the region. “You see, the clouds are only in our town,” Edgar half-joked as the afternoon sky darkened.

The Uprising in Cherán Became an Inspiration, and led to a wave of copycat outbursts across Michoacán in what became known as the autodefensas movement. Vigilante groups took up arms and notched a number of victories, succeeding where the state had proven inept or corrupt. Community policing initiatives followed. For a time, this approach even enjoyed the tacit support of then-president Enrique Peña Nieto.

But the movement quickly dissolved. Many autodefensa organisations were infiltrated by former cartel members; some began selling drugs to raise money for weapons. Others were bankrolled by wealthy avocado interests sick of paying bribes or seeing shipments robbed. By 2018, the autodefensa system had, in many ways, become indistinguishable from cartel control.

Take one especially perverse example: in 2020, a group of avocado farmers formed a group called Pueblos Unidos, claiming to be protecting their livelihood against cartel extortion. The group’s membership ballooned to around 3,000 in a short amount of time, even scoring some international media coverage for their attempts to clean up the avocado supply chain. They lacked Cherán’s environmental commitments from the get-go, and were soon linked to the Knights Templar Cartel. On the day I left Michoacán, they were involved in a standoff with authorities that resulted in the kidnapping of national guardsmen, the torching of a car and more than 100 arrests. According to Mexican officials, it was one of the biggest cartel busts ever.

The Cherán council told me that dozens of other localities in Michoacán have adopted its model of governance, forming an archipelago of radical environmental resistance. While each town has its own method of implementation, the charter remains basically the same: a democratically elected council, a militarised commitment to environmental protection, and no political parties or avocados.

Council Members in Cherán Town Hall

Twenty minutes from Cherán is the town of Arantepacua, which achieved official independence in 2018. When we drove over, a small team of labourers was at work building a checkpoint. No one stopped our car for questioning.

The town square was flanked by a crumbling church and a peach-coloured municipal building. I was trying to get in touch with the mayor, Alberto Martinez, but he wasn’t responding on WhatsApp. I asked a woman if she knew where I might find him. “He’s right there,” she pointed, “the small one in green.”

Standing on the corner was an excitable man, his hair neatly combed, wearing a pressed polo shirt tucked into khakis. He shook my hand vigorously before I’d even spit out an introduction, and pulled me into the administrative building behind him, where a portrait of Zapata again loomed above the entrance.

Sitting at one of the two desks in Martinez’s corner office, bottle-feeding her four-month-old child, was Maria Elena Soria Morales, a 33-year-old school teacher who is now serving a two-year term as the head of security, elected alongside another woman. She oversees the kuariches, the town’s version of Cherán’s ronda.

But Arantepacua’s adoption of the Cherán model, Maria told me, had little to do with environmental despoliation, at least at first. On 5 April 2017, Michoacán state troopers came to retrieve what they said were stolen vehicles. The town had had a longstanding feud with the state government because of territorial disputes and what I was told was overzealous policing.

Officers with shotguns kicked down the door of the house that Maria had taken shelter in, she told me, one shooting at her and another pointing a gun at her sister. A helicopter circled overhead. A terrified schoolboy in a red sweater, running toward the forest, was shot, his body flying through the air “like a kite”, Maria said, fighting tears. Four people were killed.

Left: A member of the community police at Cherán's entry checkpoint. Right: Cherán

The next day, the town set up a makeshift checkpoint at its highway exit to prevent the police from returning. Then they began to overhaul the government. “After that, we got organised to elect our own authorities,” she told me. “If we don’t organise ourselves, this will never stop. We have to do it like Cherán.”

Arantepacua’s new government made environmental protection a priority, and outlawed avocado cultivation on communal forest land. “It harms the soil,” Maria told me. “When we drive on the road to Uruapan, we can feel the chemicals in the air and we know how bad it is. So we don’t allow it.”

Now one of her top concerns is the water supply. In recent years, the water level in the town’s well has sunk lower and lower, while the neighbouring town of Capácuaro cuts down its forests, and nearby Turícuaro expands its avocado operation. “We hear that they’re doing it on the top of the mountains,” she said. Still, she told me, the town was doing its best. Her baby burst into tears, and she whisked him away for a nap.

I Wanted to See What Life was Like in the Thick of the Avocado Corridor, a stretch of fertile soil and clement weather that yields an astonishing year-round harvest. I headed to the outskirts of Yoricostio, 55 miles south-east of Cherán, where I visited a farming hamlet full of avocado orchards.

I pulled into a parking lot in front of a church, where two farmers were leaning against a pickup truck. They took me on a tour of the groves, which, by every indication, made them a handsome profit, and then to the home of Ernesto, a local avocado farmer who was hosting a number of his neighbours. Avocados weren’t the only thing being farmed on Ernesto’s holdings; there were also pepper plants, beans and pumpkins.

Left: Frutas Finas, an avocado packing plant in Tancítaro, Michoacán Right: An Engineer at Frutas Finas monitors avocados on the packaging line

Three decades ago, he didn’t grow avocados at all. “I remember 31 years ago when Ernesto planted the first tree,” Marilu, his wife, told me. “His father told us there was no point.” But the decision paid off, and they had expanded their footprint steadily. Now they were selling avocados for export to the US and had hired additional workers to harvest the crop. Theirs was a midsize operation, and the money seemed to be good enough – their pickup truck was new and their two-storey home beautiful. They had plans for renovations. But there were problems of late. The year prior, for the first time, they had to dig retaining ponds and set up rain barrels to secure enough water for a desiccated avocado harvest. The other crops, too, needed to be watered by hand. “The climate has changed,” Marilu told me. “It’s hotter, drier. We used to water all our plants just with the rain. Not any more.”

Above the town was a small dam, and a reservoir to draw from in case of drought. That winter a work crew, armed with expensive heavy machinery, had begun laying a pipe at the foot of the dam. They claimed to be acting on behalf of the local water authority, but their story kept changing. Some of the farmers complained to the local government, to no avail. Others alleged corruption.

“You don’t have to be very smart to figure out where the water is going,” said Noemi Mondragon, a local farmer. The unfinished pipeline seemed to be pointed toward a new 200-hectare avocado grove. “People say that the avocado is the devil,” Noemi told me. “That isn’t true. There are ways to raise it sustainably.” As she saw it, the biggest problem with the avocado was that “it brought greed, which brings ambition, which brings scarcity”. Water levels at the dam had already reached new lows. “Look at the size of the pipe,” she added. “If they get that water, the dam will be empty in two weeks.”

The farmers told me that they had scared off the construction crew the day before Christmas, with a shovel-wielding Marilu at the front. Staring down a menacing foreman and a line of tractors, she told me, she’d filled in the basin where the pipe was being laid. Noemi and other neighbours joined, shoulder to shoulder, until the group grew large enough to drive the workers away.

Given the exceptional amount of avocado-related violence in the region, the story struck me as surprisingly tame. Earlier that year, a prominent anti-avocado activist had been kidnapped and beaten in another part of the state. Months later, I expressed some confusion about the account, and found out that the farmers had also been stockpiling guns, many of which were illegal. They’d left that detail out.

Left: Avocados for sale in Cherán. Center: The forest near Cherán. Right: A donkey pulls wood collected in a nearby forest

Still, the situation reminded me of Cherán’s path: the alleged corruption, the threatened water supply, the uprising. It seemed like the town might be open to a radical environmental overhaul, to save their community and some elements of their way of life. It wasn’t hard to envision a near future in which that was one of very few viable outcomes.

Farm workers pick tomatoes in the countryside near the town of Foggia, southern Italy, September 24, 2009. Every year thousands of immigrants, many of them from Africa, flock to the fields and orchards of southern Italy to eke out a living as seasonal workers picking grapes, olives, tomatoes and oranges. Broadly tolerated by authorities because of their role in the economy, they endure long hours of backbreaking work for as little as 15-20 euros ($22-$29) a day and live in squalid makeshift camps without running water or electricity. Picture taken September 24, 2009.

But when I mentioned Cherán, no one praised it as an inspiration; no one seemed to know what it was at all. And there were critical differences. Cherán had been a relatively poor, Indigenous community, cut off from the green-gold rush.

The farmers of Yoricostio had managed to tap into a global flow of water and wealth. Was there a way forward for these farmers that wasn’t also a step down? If the climate or the industry abandoned them, which way would they point their guns?

Later that afternoon, the farmers gathered around a grill, where Ernesto was searing pieces of beef. They placed a big bowl of guacamole at the centre of a long picnic table and passed around a jug of mezcal, encouraging me to pour myself a drink, and then another. The clouds gathered overhead and light rain began to fall. Then it stopped.

— A Longer Version of this Piece First Appeared in Harper’s

#The Long Read#An Article#AVocados 🥑 🥑 🥑#Mexico 🇲🇽#Food 🍲 🥘 🍱#Mexico 🇲🇽 Food 🍲 🥘 🍱#Farming#Features#Harper’s Magazine#The Guardian USA 🇺🇸

0 notes

Text

HAPPY SEPTEMBER 15 OF MEXICO!!! 🇲🇽💚🤍❤️

Now it's time for...

KENJI SATO X HISPANIC READER

He's deeply in love with you.

You taught him all about your culture.

Kenji meets your family, and he is really surprised to see many people.

He eats one of your favorite foods.

Your family got excited once you have a lover that you really love.

Your mom teaches kenji how to dance, and you also taught him well.

He gets really nervous to dance.

He taught your cousin of baseball.

Your group aunts keep asking you if you're married and also ask kenji too.

I'm still figuring out how you two met.

Kenji celebrate the holidays of Mexico and you also celebrate the Japan holidays.

#ken sato x reader#ken sato x y/n#ken sato x you#kenji sato x y/n#kenji sato x you#kenji sato x reader#kenji sato x hispanic reader#ken sato x hispanic reader#ultraman rising x y/n#ultraman x you#ultraman x reader#ultraman rising x reader#ultraman rising x you

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fernando Palma Rodríguez, Tezcatlipoca, 2013. Courtesy of the artist

Fernando Palma Rodríguez: Āmantēcayōtl

May 3–July 27, 2024

Opening reception: May 3, 6pm

Canal Projects

351 Canal St

New York, NY 10013

United States

Hours: Tuesday–Saturday 12–6pm

Fernando Palma Rodríguez: Āmantēcayōtl

Ground floor

Canal Projects is pleased to announce a new commission by the Nahua artist Fernando Palma Rodríguez (b. 1957, Mexico). A pioneer of Indigenous robotics, the artist’s new project Āmantēcayōtl: Auh inihcuac huel ompoliuh, mitoa, ommic in meztli presents an installation that emulates a corn field on the slopes of the Teuhtli Volcano in Milpa Alta, Mexico. At Canal Projects, the exhibition features three robotic entities that represent different deities of the mesoamerican pantheon.

Together, the mechanized entities make evident the sacred relationship that exists between Nahua cosmologies and the cultivation of corn, bean, and squash, which are grown together in what is traditionally known as the Milpa. At the center of the exhibition, the Cincoatl snake glides through a corn field while the Tezactipoclas interact with viewers, embodying traditions involved in caring for and being in community with the land. The artist’s invocation of the sacred pantheon, more than a personification of these deities, redefines the very notion of the robot as a conduit for the recuperation of the Nahuatl language, earth technologies, and the positioning of Aztec cosmologies.

Palma Rodríguez combines his training as an artist and mechanical engineer to create robotic sculptures that are activated through internet-sourced climate data from the Milpa Alta region. His works respond to issues facing Indigenous communities in Mexico today while also underscoring that the struggles for the protection of life and the defense of territory are inseparable from the recuperation of traditional ways of life. Central to Palma Rodríguez’s practice is an emphasis on ancestral knowledge, both as an integral part of contemporary life and as a way of shaping the future.

Fernando Palma Rodríguez

#🇲🇽#Fernando Palma Rodríguez#STEM#native#indigenous#nahua#aztec#robotics#Āmantēcayōtl#mexican mechanical engineer#mexican artists#mexico#canal projects#food#milpa alta#Teuhtli Volcano#mexican engineers

1 note

·

View note

Text

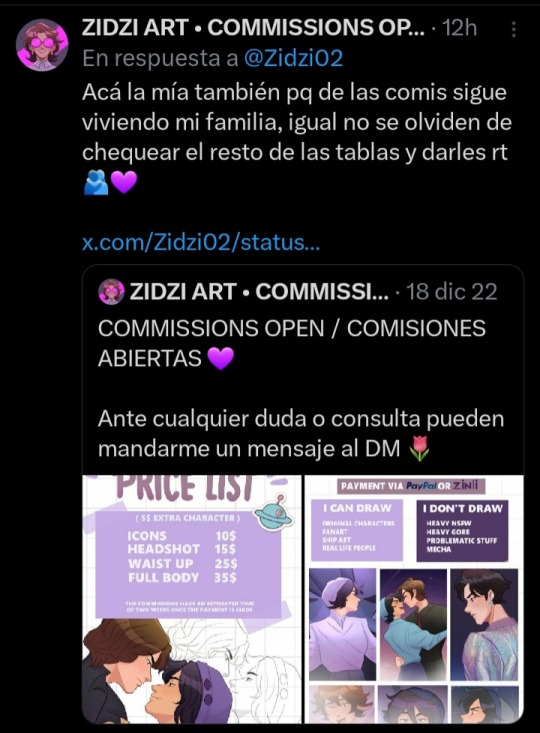

PLEASE HELP VENEZUELAN ARTIST!!!

Hellooo everyone!! if you can help some 🇻🇪 artist pls consider asking for a comission or share!!

@ Zidzi02 made a tweet for 🇻🇪artists to leave their comm info for people to check

"Commissions help me to bring food for my mom and brother, like me there are other Venezuelan artist that live from their art, if you know a friend or you are and artist with open commissions leave the comission table here and help me spread the information"

-> tweet link

Here some artists but there are more in the comments!!

@ zidzi02 @ 1800_Sad_Satan

@ gramckode @ dantegrifyn

@ anyelers @ _o8cho

@ bicrysis

ANOTHER THREAD!!!

"VENEZUELAN ARTIST🖌🇻🇪

I know that like me, commissions help you and your family a lot

Use this tweet to publish your work

And those who are not from here can help by sharing this tweet and the artwork

Let's help each other"

-> tweet link

@ RafaGars

I can't add more images but pls check the threads! There's a lot of artist with different styles, you'll be helping a lot!

And please listen to Venezuelans and educate yourself on the elections situation, there's a lot going on and the world has to know

Mucho ánimo a la gente venezolana, les mando muchas fuerzas y un abrazo. No estan solos 🫂🇲🇽

#my artwork#artists on tumblr#small artist#art#digital art#qsmp#fanart#qsmp fanart#qsmp eggs#artwork#my art#venezuela

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

#food#scr4n#food polls#poll#polls#this or that#this or that poll#this or that polls#scr4npolls#scr4n polls#mexican#italian#italia#mexican food#italian food#foodpoll

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Xilonen and her Brazil elements

Just starting off the post saying that I know she also has Mexican elements in her character, Genshin has a tendency of mixing a bunch of cultures up so it's entirely possible for her to be both Mexican AND Brazilian, I won't talk about those aspects because I'm clearly not Mexican-

Brazil Mexico union okay??? No fights, we love you Mexicans 🇲🇽🇧🇷

First we'll start with the fact that Xilonen is a jaguar! Jaguars are animals that are typically found on the American Continent, Xilonen has the same patterns of their fur, plus she is also shown laying on a tree on the trailer, which is a thing jaguars do. Jaguars are important figures to Brazil (plus they're called onça-pintada... calling them jaguar feels like a crime), they represent our biodiversity and how it's important to protect and conserve these species. The country decided to represent national species on the official money notes, and the jaguar is present in the 50 reais note.

From what we've seen from her so far, she is related to music, probably a DJ, and in fact some of her elements are related to the most stereotypical Brazil things ever, Samba, Carnival and Funk.

I'll begin this part talking about each of these thing in more detail. Samba is a Brazilian music genre and dance usually related with Carnival, it's origins come from Afro-Brazilian people communities in Bahia and then later on Rio de Janeiro. The Brazilian Carnival is the most popular holiday in Brazil, where people usually just come together to have fun and dance, it's very tied to Samba as most people there dance it during Carnival. Funk is a music genre in Brazil that came from black communities in Rio de Janeiro, mostly from favelas. All of these things are part of Brazil culture and also part of the stereotype people outside think of Brazil, usually people think we are only these things

As for Xilonen, her high heels are extremely similar to the heels the Samba dancers use, her makeup is glittery and she has glitter around various parts of her body, glitter is very used in Brazilian Carnival. Her outfit looks like a typical outfit a Brazilian funk dancer would wear (if you disagree about that just take a look at Brazilian Miku design) and her lots of rings and big necklaces are also used by funk singers.

This particular idle or hers looks like she's kinda dancing Samba with her roller-skates, but I'm not entirely sure about it

Last part, her signature dish is made using the brigadeiro recipe, which is a traditional Brazilian food! But her signature dish looks like just some regular chocolates unfortunately

As you might have noticed, most of these elements in Brazil culture are from Afro-Brazilian origin... So why the fuck is she white?? I know Brazil IS diverse and has white people but... this is kinda like making a white rapper character, wait hoyo already did that too?? No surprise.

#theo is rambling again#I'm not maintagging this I don't wish to be found so easily by the Genshin fandom#I'm sorry. the only reason I'm doing this post is because I like infodumping and talking about Brazil...#i think this post isn't that long just because I'm not that big about Carnival or Funk and I don't even live in Rio#if this was about Cangaço or any northeast culture ohhhh i would be making such a big post...#i wish she wasn't so.... Brazilian stereotype? at least maybe we have some hope left for Iansan. our Afro-Brazilian queen...#but knowing this company I have no hope. I'm never coming back unless they fix their mistakes

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝘩𝘪, 𝘪'𝘮 𝘫𝘢𝘮, 𝘣𝘶𝘵 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘤𝘢𝘯 𝘤𝘢𝘭𝘭 𝘮𝘦: Ximena, Jam, Jamona, Tyler, Andy, Drew, Andrew, Nick, Nicky, Sarah, Sarahi, Ed and Kool aid :) 𝘐 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘺 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘴𝘦 𝘯𝘢𝘮𝘦𝘴 <3, 𝘣𝘶𝘵 𝘱𝘭𝘦𝘢𝘴𝘦 𝘥𝘰𝘯'𝘵 𝘤𝘢𝘭𝘭 𝘮𝘦: Xime, amis, bb or baby :( 𝘐𝘤𝘬! 𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘴𝘦 𝘯𝘪𝘤𝘬𝘯𝘢𝘮𝘦𝘴 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘺 𝘵𝘳𝘪𝘨𝘨𝘦𝘳𝘪𝘯𝘨!!!, 𝘣𝘶𝘵 𝘢𝘯𝘺𝘸𝘢𝘺𝘴, 𝘮𝘺 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘦𝘴𝘵𝘴 𝘢𝘳𝘦: big mouth, the office, huevocartoon punch out, yandere simulator, ed helms and total drama <3 𝘺𝘦𝘢𝘩, 𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘴𝘦 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘺 𝘤𝘰𝘰𝘭, 𝘣𝘶𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘣𝘭𝘰𝘨 𝘪𝘴 𝘧𝘰𝘳 𝘣𝘪𝘨 𝘮𝘰𝘶𝘵𝘩!, 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘴𝘦 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘮𝘺 𝘧𝘢𝘷 𝘤𝘩𝘢𝘳𝘢𝘤𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘴 andrew glouberman(of course), nick birch, maury and missy ^_^ 𝘛𝘏𝘌𝘠'𝘙𝘌 𝘛𝘏𝘌 𝘉𝘌𝘚𝘛!!!! 𝘣𝘶𝘵 𝘢𝘯𝘺𝘸𝘢𝘺𝘴, 𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦'𝘴 𝘴𝘰𝘮𝘦 𝘴𝘵𝘶𝘧𝘧 𝘪 𝘥𝘰𝘯'𝘵 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦, 𝘪𝘵'𝘴 𝘯𝘰𝘵 𝘢 𝘥𝘯𝘪 𝘣𝘦𝘤𝘢𝘶𝘴𝘦 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘤𝘢𝘯 𝘴𝘵𝘪𝘭𝘭 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘢𝘤𝘵, 𝘣𝘶𝘵 𝘥𝘰𝘯'𝘵 𝘦𝘹𝘱𝘦𝘤𝘵 𝘮𝘦 𝘵𝘰 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘪𝘧 𝘺𝘰𝘶 if you're a pedo or something similar like a zoophilic, if you're a yapper (not like you talk a lot, like if you're an actual one and keep changing the topic on and on and don't let the others talk), if you're a pophead, if you use too much slang (like the 'yass queen slay' type of thing), if you're a hater, if you like polemics, if you think everything is cringe (#cringecultureisdead!!!), if you think making fun of others is okay, if you judge too much and specially...IF YOU DON'T LIKE BIG MOUTH 𝘐 𝘢𝘭𝘴𝘰 𝘩𝘢𝘷𝘦 𝘰𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘳 𝘴𝘰𝘤𝘪𝘢𝘭 𝘮𝘦𝘥𝘪𝘢, 𝘪'𝘮 𝘯𝘰𝘵 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘺 𝘢𝘤𝘵𝘪𝘷𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘰 😅 my insta my wattpad my other tumblr blog my picmix my pinterest my youtube my strawpage 𝘮𝘺 𝘧𝘢𝘷 𝘮𝘶𝘴𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘢𝘯𝘴/𝘣𝘢𝘯𝘥𝘴 𝘢𝘳𝘦 the front bottoms, elton john, lil nas X, tyler, the creator, the beatles, ringo starr, ed helms, chencho corleone, el cuarteto de nos, sir chloe, sofTT, toy box and monte carlo :0 𝘈𝘓𝘚𝘖, 𝘛𝘏𝘐𝘚 𝘐𝘚 𝘔𝘠 𝘒𝘐𝘕𝘓𝘐𝘚𝘛!!!! andrew glouberman, toby flenderson, andy bernard, tyler kenard, flynn white, coco from an egg movie, stu price and basically any character ed helms have ever performed <3 𝘪'𝘮 𝘢𝘤𝘵𝘶𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘺 𝘱𝘳𝘦𝘵𝘵𝘺 𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘭, 𝘪 𝘩𝘰𝘱𝘦 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘨𝘶𝘺𝘴 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘵𝘶𝘧𝘧 𝘪 𝘱𝘰𝘴𝘵 𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦, 𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘴𝘰𝘮𝘦 𝘭𝘢𝘴𝘵 𝘥𝘦𝘵𝘢𝘪𝘭𝘴 𝘪 𝘸𝘢𝘯𝘵𝘦𝘥 𝘵𝘰 𝘴𝘩𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘵𝘰𝘰 i'm mexican 🇲🇽, my fav food is pizza, i have astigmatism and i like fidgeting with anything XD

(credits to @/sister-lucifer for the p3nis dividers <3)

14 notes

·

View notes