#貴bon

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Extras - The Extreme Path Omake

Omake, meaning bonus! Some translation notes, name meanings, references, and stuff for The Extreme Path. If there's anything I haven't covered you're curious about, lemme know and I'll add it onto this baby! :D

NAME MEANINGS:

Morimoto (森本) - mori (森) means "forest", while moto (本) means "origin", making the surname loosely mean "from the forest". Perfect for a family of woodland critters!

Shigeru (茂) - means "lush" or "luxuriant", which seems right for a fancy bon vivant like Spy. I'll be honest though I didn't even occur to me until the day of writing (9/11/24) that Morimoto Shigeru sounds kinda like Miyamoto Shigeru (yanno the Mario guy) and I promise you that was an accident.

Yoko (洋子) - yo (洋) means "ocean" and ko (子) means "child".

Kenji (堅志) - ken (堅) means "firm, tough, or strict", and ji (志) means "purpose or ambition".

Yamabane (山羽) - yama (山) means "mountain" and hane (羽) means "feather". (Hane is pronounced bane when it's added onto a compound word, going from an unvoiced to a voiced syllable.)

Kazuhiro (一浩) - kazu (一) means "one", or in this case "a certain person", and hiro (浩) means "prosperous"

Yamamori (山森) - means "mountain forest", which also combines the first characters of Yoko and Kazhuro's surnames!

Henrik Koopman - Henrik means "home ruler", and wasn't picked for its meaning so much as I liked the sound of it. Koopman however means "merchant". Career-appropriate nomenclature!

Umino Himeko - (海野 姫子) - Umi (海) means "ocean", no (野) means "field, or area", hime (姫) means "princess", and ko (子) means "child". So when Henrik calls Himeko "princess" he's not just being a sweetie, he's also using a pet name based on her actual name.

Henri Renard - Henri, Spy took in honour of his late husband, as Henri is the Francophile form of Henrik. Renard is French for "fox".

Makai (魔界) - means "evil world" or "demon world", and comes from Buddhism. Per Wikipedia: "...it is the opposite of the Buddha world, and can refer to the four heavens above desire. The synonym Makyo (魔境, 魔境) is sometimes used to mean a mysterious and frightening place or a place that tempts people, such as a red-light district. ... As a metaphor, the Makai is sometimes used to refer to a place where legends about vengeful spirits, monsters, sorcery, etc. remain. ... In fantasy and legend-based fiction, it is often depicted as another world inhabited by demons, monsters, etc." Traditionally Yakuza families are named for their founding patriarch, so who knows if this family breaks the trend, or if a youkai who took the surname Makai was its founder way back when?

Yakuza (ヤクザ) - literally means "eight, nine, three", which is the worst hand one can get in the card game Oicho-Kabu, which works a lot like Baccarat. (I love it it's a lot of fun.) Much of the yakuza originally started as illegal gambling dens, hence a losing hand like that might end up with you oweing the crime family who runs the joint a LOT of money.

The Extreme Path - Yakuza typically don't call themselves "yakuza". They refer to themselves and what they do as "gokudo" (極道), meaning "the extreme path". If you note, Spy, being an ex-yakuza (though never banished nor actually expelled from the family so technically he still is one as far as the family's concerned) calls it that when he's speaking Japanese.

Aniki (兄貴) - means "older brother". The yakuza use familiar terms for one another. For the sake of the reader this and kyodai were the only ones I didn't translate, since the vibe is very different between how yakuza use those words and how civilians use them. Typically a yakuza will refer to a member of their family who is senior to them as Aniki as a title of respect, assuming they don't have a title within the family. You wouldn't call the captain Aniki, you'd call him captain (Kashira), for example.

Kyodai (兄弟) - means "brother" or "sibling", and typically is not used to address a person directly. Unless you're yakuza and they're your sworn brother. Also used to refer as a group to the upper level yakuza in a family. The "made men" to put it in mafia terms.

Patriarch - Localized from Oyabun (親分) meaning "adoptive father" and Oyaji (親父) meaning "father (informal, masculine)", used to refer to the head of a yakuza family.

Captain - Localized from waka-gashira (若頭), literally meaning "junior head". The second-in-command of a yakuza family, tasked with carrying out the oyabun's wishes. When addressed, it's usually as Kashira or [Name]-gashira.

Lieutenant - Localized from shatei-gashira (舎弟頭) literally meaning "younger brother head", the guy in charge of the boys directly, basically.

-han - In Kansai-ben, the dialect of Japanese spoken in the Kansai region, which is where Osaka is, the suffix -san is often said as -han instead. If you notice, while the Morimoto triplets and the yakuza speak Kansai-ben, which I wrote with a rougher tone (true to its cultural perception as being super informal and almost a lil rude), Kazuhiro and Sniper speak standard Japanese, hence they both use -san when appending that suffix onto people's names.

NAME REFERENCES:

Nagoshi - Named for Nagoshi Toshihiro, who is the creator of the Ryu Ga Gotoku game series, known in the west as Yakuza and Like A Dragon (they've been rebranding recently, "Ryu Ga Gotoku" means "Like A Dragon" so they're just kinda making the names uniform), which I am obsessed with, and actively inspired SO MUCH of this story, particularly the entry set in the lead-up to the Boshin War, "Ryu Ga Gotoku: Ishin! Kiwami", the remake of which finally came to English and sparked the brainworms that became this story, lol. So you can blame him for all of this, basically. I've wanted to set a story with Spy in Japan for literal years, but Ishin! made me pull the trigger.

Ugaki Goro - Ugaki comes from Ugaki Hidenari, the voice actor of Majima Goro, from the Ryu Ga Gotoku series. Majima's absolutely my blorbo so I had to make the reference. Also, honestly, the way I describe Ugaki Goro ended up looking a little teeny bit like Ugaki Hidenari by accident. Wonder if he's a voice-acting kawauso!

Daito Shigeki - Daito comes from Daito Shunsuke, voice actor of Baba Shigeki from RGG 5, a character with conflicting loyalties! Daito Shigeki's weren't so conflicted, turns out.

Sawamura Kazuma - Sawamura comes from Sawamura Haruka, precious adoptive daughter of Kiryu Kazuma, the main character of the RGG series and good good boy who I love so much.

Kanda - Named for one of the skeeziest motherfuckers in the RGG series, Kanda Tsuyoshi.

Ugaki Rie - Rie comes from Kugimiya Rie, voice actor of Sawamura Haruka.

Kasuga Akira - Kasuga comes from Kasuga Ichiban, main character of RGG 7 and 8 and good good boy, and Akira comes from Nishikiyama Akira, villain of RGG 1 and sworn brother of Kiryu Kazuma, and fallen good boy. Ichiban and Nishiki are voiced by the same actor, Nakaya Kazuhiro.

Kuroda Akio - Kuroda comes from Kuroda Takaya, voice actor of Kiryu Kazuma. Akio comes from Outsuka Akio, voice actor of Adachi Kouichi from RGG 7 and 8, one of my favourite characters, as well as Isami Kondo in RGG Ishin! Kiwami.

FLOWER MEANINGS:

Asters - Rememberance, I won't forget you

Spider Lilies - Death, never seeing someone again, abandonment

Lavender - Faithfulness, loyalty

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Petites précisions à propos du RinBachi

Rin jouait depuis 2/3 mois au PxG (il a été prêté par le Barcha son équipe actuel) quand c'est arrivé.

Je parlerai de tout ce qui est RinNana ailleurs. Et quand j'aurais le temps de tout ce qui est avant cette histoire pour le Rinbachi.

Pourquoi YukkiNana? Je sais pas, ça a juste fait tilt dans ma tête. Eux aussi auront leur petit moment de gloire ;)!

Alors les jumeaux mélangent l'Espagnol et le Japonais quand ils parlent. D'où le Tio (aka oncle/tonton) pour évoquer Rin et Meguru.

Je mettrais la trad des prénoms des enfants Kiis Et NagiReo (oui Maria a une version avec Kanji) dans leurs fics respectifs ^^

Alors pour les enfants RyuSae, voilà la signification de leurs prénoms. J'ai tenté de faire en sorte que ça match avec le nom de famille, comme pour la serie.

Kouki (h)/Aki (h) (13/10/20xx)

Kouki 煌 scintillant 海 mer Donc pour Shidou Kouki ça ferait : "Code samouraï de la mer scintillante (je sais pas si ya possibilité d'inverser les kanjis dans la trad mais bon) Aki 空 ciel 貴 honorable Ici Shidou Aki "Code Samuraï du ciel honorable"

Hikaru (f)/Hikari (h) (10/03/20xx) Hikaru 妃 Princesse 星 étoile Shidou Hikaru "Code Samuraï de la princesse des étoiles) Hikari 光 Lumière 星étoile Et pour Shidou Hikari "Code Samuraï de la lumière étoilée"

Est-ce que ça a du sens? Je ne suis pas sûre. Mais je voulais tenter le coup.

Et oui pour la paire 2 il y a le kanji de l'étoile pour les 2 pour la double ref. Le "Sei" de Ryusei peut se lire etoile. Et la chanson préféré de Sae (Suisei de Tofubeats feat Kariya Seira, un vrai coup de cœur ❤) en parle vite fait également. Quand a Kouki et Aki, la mer est un des endroits préférés de Sae. Le ciel est une ref pour la chanson préféré de Ryusei (Pink spider de Hide with Spread Beaver, que j'aime beaucoup aussi).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

夏灯篭 (HACHI) English Translation

夏灯篭 Natsu Tourou Summer Lantern

HACHI Lyrics, Composition:Mizutama Umino Arrangement:Seiji Iwasaki

MV here.

-----

T/N: Keep in mind that Japanese and English aren’t my first language. I never claim my translation (attempts) to be error-free. As always, if you’re going to use or reference my translations, please do not claim it as your own and credit me.

-----

砂浜はさらり 夜の海は昏々と 波間をすべる 夏燈り 灯篭よ 水平の向こうに 私は逝くか? 貴方はいるか? チラチラと 燃ゆる送り火

Sunahama wa sarari Yoru no umi wa konkon to Namima wo suberu Natsu akari tourou yo Suihei no mukou ni Watashi wa yuku ka? Anata wa iru ka? Chirachira to Moyuru okuribi

The sandy beach feels smooth and The sea at night is deep in slumber Gliding through the waves are The summer lanterns and their lights Shall I go Beyond the horizon? Will you be there? Along with the glimmering Burning bonfire (of O-bon)

もしもこの命 明日を迎えられず 吹き消えるように 瞳を瞑るとき 貴方のそばに いけないのなら 私はやはり 生きていたいのだと 足掻くだろう

Moshimo kono inochi Asu wo mukaerarezu Fukikieru youni Hitomi wo tsuburu toki Anata no soba ni Ikenai no nara Watashi wa yahari Ikiteitai no da to Agaku darou

Suppose, this life Could not welcome tomorrow. As if ceasing to exist When I close my eyes. If I cannot go and Stay by your side, Sure enough, for me - To still want to live - It will probably be a struggle

誰もが暗い海の上で 灯火を抱いて生きていく ゆらめく旅路は美しい

Daremo ga kurai kurai kurai umi no ue de Tomoshibi wo idaite ikite yuku Yurameku tabiji wa utsukushii

Anyone on surface of the dark dark dark sea Continue to live embracing the light The flickering journey is beautiful

時は流れ行き 巡る日々は淡々と 夏が来るたびに 心はもどかしい 線香花火の音 火花が散って 燻りながら 淑やかに ポツリ落ちゆく

Toki wa nagareyuki Meguru hibi wa tantan to Natsu ga kuru tabi ni Kokoro wa modokashii Senkou hanabi no ne Hibana ga chitte Kusuburi nagara Shitoyaka ni Potsuri ochiyuku

Time goes by and The days pass by indifferently Every time summer comes My heart is frustrated The sound of sparklers The sparks scatter While it smolders Gracefully Falling down one by one

砂浜はさらり 夜の海は昏々と

Sunahama wa sarari Yoru no umi wa konkon to

The sandy beach feels smooth and The sea at night is deep in slumber

時は流れ行き 巡る日々は淡々と

Toki wa nagareyuki Meguru hibi wa tantan to

Time goes by and The days pass by indifferently

波間をすべる 夏燈り 灯篭よ どうか果てまで届け

Namima wo suberu Natsu akari tourou yo Douka hate made todoke

Gliding through the waves are The summer lanterns and their lights Please, may they reach the very end

もしもこの命 七日の限りなら 声が枯れるまで 歌を歌いながら 何も残せずに 逝きたくないと 嘆くだろうか 蝉時雨 止まぬ夏空

Moshimo kono inochi Nanaka no kagiri nara Koe ga kareru made Uta wo utai nagara Nani mo nokosezu ni Yukitakunai to Nageku darou ka Semishigure Yamanu natsuzora

Suppose, this life is Only limited to seven days Until my voice goes hoarse While I sing a song I do not want to depart this life Without leaving anything behind Will it mourn, I wonder? The chorus of cicadas The endless summer sky

貴方は暗い海の涯で 灯火を今年も待つのでしょう 道標となれ夏灯篭

Anata wa kurai kurai kurai umi no hate de Tomoshibi wo kotoshi mo matsu no deshou Michishirube to nare natsu tourou

You are at the edge of the dark dark dark sea You will be waiting for the lights this year as well, won't you? May they become your guide, the summer lanterns

ゆらめく旅路は美しい Yurameku tabiji wa utsukushii This flickering journey is beautiful

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

兔年春節企業禮贈品送禮 中式禮物有特色又實用

兔年將近,很多華人發愁如何選購具有中式特色的禮物給親朋或外國友人,本期推薦四款具有中國新年風情的春節好禮,兼具中國文化美感和實用性。

LadyM聯合美樂蒂推出春節大紅禮盒套裝。LadyM真的懂中國傳統節日禮盒,這次春節請出三麗鷗超級可愛的美樂蒂,推出兩款禮盒套裝,一款是兔年春節禮盒實用贈品,另一款是春節禮盒+紅豆千層蛋糕套裝。春節禮盒分成六層,營造了一個美樂蒂的3D場景。六個裝滿定製糖果的幸運抽屜,裡面是來自Lady M Bon Bon的限定糖果,口味有荔枝、柑橘、覆盆子等。禮盒還有一套華麗的美樂蒂春節紅包。搭配禮盒推出的紅豆千層蛋糕,將其招牌的千層蛋糕覆蓋上由北海道採購紅豆製成的的鮮紅豆糕點奶油,不僅甜甜蜜蜜,還喜慶紅火。

花西子中式粉黛,揚東方之美,助百年國妝。來自中國的小眾東方元素奢侈品化妝品牌,基於中國元素,視覺語言很有國風標誌性。例如其大熱的同心鎖口紅、四獸修容盤、玉養版空氣蜜粉等。不僅採用國風雕花等工藝設計包裝,配色和配方上也是按���中國古典記載的顏色,進行100%的還原和調配。目前該品牌已進軍美國市場,目標群體是那些對東方文化有興趣的女性群體,且配合當地市場對色彩的偏好,推出各種限定產品,希望在歐美美妝品牌強敵林立的美國市場展示東方之美。

Lego的搖錢樹和春聯。樂高太會拿捏華人的心了,這次推出價值25元的新春搖錢樹在沒發布前,不少華人就已虎視眈眈躍躍欲試了,果然發布後沒多久就斷貨了,目前在其他平台以兩倍以上的高價售出。只怪這款搖錢樹太投華人所好了,在中國文化裡,人們都相信搖錢樹能帶來富足、繁榮和好運。這款搖錢樹高六英寸,裝飾20個金桔、14個紅包和十個金幣。沒搶到搖錢樹也可選擇樂高剛發布的春節春聯裝飾,兩個方形春聯上有元寶、錦鯉、紅包及「招財進寶」祝福語,還有可拼砌的牡丹花,及「花開富貴」祝福語。作為春節企業禮贈品禮物,別緻又有好彩頭。

Louits Vuitton的兔子周邊產品,其奢侈品把春節限定作為華人消費者流量密碼。LV2023年出全新生肖兔的主題產品,包括兔子擺件、鑰匙卡扣和圍巾等單品。LV將品牌吉祥物Vivienne進行特別改造,實用贈品設計成兔子樣子。尤其是推出的兩款絲巾,一面是戴著LV棒球帽和手提包的兔子造型,一面是經典的交織字母圖案,採用100%絲綢材質,作為禮物送人,男女老幼皆宜。

更多世界日報報導

0 notes

Text

master of the court - Successor of the court - - Maîtresse de la Court -

森を抜け 墓場から追われ

Après vous être échappé de la forêt et poursuivi dans le cimetière

辿りつくだろう 古い映画館

Vous parviendrez sans doute au Vieux Théâtre

その場所で 貴方は裁かれ

En ce lieu, vous serez jugé,

罪を得るだろう 最後の審判

Vous comprendrez vos péchés et recevrez le Jugement Dernier

時計塔で廻る歯車

Les engrenages de l’Horloge tournent

人形(ドール)は父の遺志を継いだ

La Poupée héritant du souhait de son défunt Père

そうよ私が新たな法廷の主

C’est exact, je suis devenue la nouvelle Maîtresse de la Court

今 開かれる 冥界の門

Maintenant, je vais ouvrir, les Portes de l’Enfer

教えて���my father

Expliquez-moi, my father

これが正しい選択でしょうか?

Ceci est le bon choix n’est-ce pas ?

心を持たぬ私にはわからないの

Moi qui suis dépossédée de cœur, comment pourrais-je comprendre ?

教えてよmy father

Expliquez-moi, my father

全員地獄送りでいいんですか?

Est-ce une bonne chose de tous les envoyer en Enfer ?

命を持たぬ私にはわからない

Moi qui suis dépossédée de vie, comment pourrais-je le savoir ?

語られぬ 唄もあとわずか

« Le chant qui ne peut être récité,

終わりは近いと 庭師は呟く

Arrive bientôt à son terme » me susurre le Jardinier

正しいのは 彼か魔道師(Ma)か

Qui a véritablement raison, est-ce lui ou bien la Sorcière (Ma) ?

わからないまま 槌を叩いている

Ne le sachant toujours pas, je continue d’abattre mon marteau

無機質な胎内に宿る

Bercé au sein de mon ventre inhumain

毒(イレギュラー)が身を震わす

Le poison (Irregulars) tremble de la tête aux pieds

いい子ね あなたの役目はこれからだから

Doux enfants, votre rôle ne se révèlera que plus tard,

今は子守唄で 眠っていなさい

Pour l’instant endormez-vous au son de cette berceuse.

教えてよmy father

Expliquez-moi, my father

これが正しい選択でしょうか?

Ceci est le bon choix n’est-ce pas ?

心を持たぬ私にはわからないの

Moi qui suis dépossédée de cœur, comment pourrais-je comprendre ?

教えてよmy father

Expliquez-moi, my father

理想郷(ユートピア)はこれでできるんですか?

Est-ce bien de cette manière que nous parviendrons à l’Utopie ?

命を持たぬ私にはわからない

Moi qui suis dépossédée de vie, comment pourrais-je le savoir ? そうよ私が新たな法廷の主

C’est exact, je suis devenue la nouvelle Maîtresse de la Court

今 開かれる 冥界の門

Maintenant, je vais ouvrir, les Portes de l’Enfer

教えてよmy father

Expliquez-moi, my father

これが正しい選択でしょうか?

Ceci est le bon choix n’est-ce pas ?

心を持たぬ私にはわからないの

Moi qui suis dépossédée de cœur, comment pourrais-je comprendre ?

教えてよmy father

Expliquez-moi, my father

全員地獄送りでいいんですか?

Est-ce une bonne chose de tous les envoyer en Enfer ?

命を持たぬ私にはわからない

Moi qui suis dépossédée de vie, comment pourrais-je le savoir ?

教えてよmy father

Expliquez-moi, my father

これが正しい運命でしょうか?

Ceci est le destin correct à poursuivre, n’est-ce pas ?

心を持たぬ私にはわからないの

Moi qui suis dépossédée de cœur, comment pourrais-je comprendre ?

教えてよmy father

Expliquez-moi, my father

理想郷(ユートピア)はこれでできるんですか?

Est-ce bien de cette manière que nous parviendrons à l’Utopie ?

命を持たぬ私にはわからない

Moi qui suis dépossédée de vie, comment pourrais-je le savoir ?

教えてよmy father

Expliquez-moi, my father 助けてよmy father

Je vous prie, aidez-moi, my father

——————————————————————————————

Lien fandom:

https://les-chroniques-devillious.fandom.com/fr/wiki/Ma%C3%AEtre_du_Tribunal_(chanson)

Lien vidéo youtube (ouNND dans ce cas) :

/None/

Lien chaîne de mothy:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCSmHk3xH3nkWqF0nm9z2-2Q

#e.c#master of the court#maîtresse de la court#successor of the court#evillious chronicles#mothy#french translation#traduction française#director doll

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

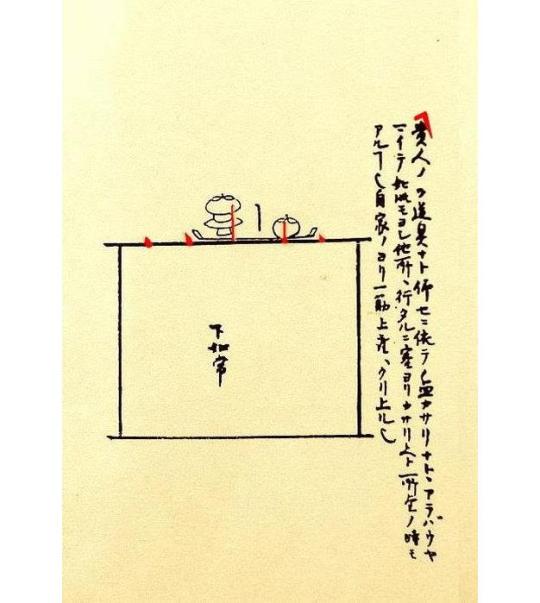

Nampō Roku, Book 5 (29): the Display of two Kinds [of Tea], One [Cha]wan, [and the] Sasa-mimi.

29) Sasa-mimi ・ ni shu ・ ichi wan kazari nari [サヽ耳・二種・一碗飾也]¹.

[The writing reads: (above, from right to left) ni no cha (二ノ茶)², ichi no cha (一ノ茶)³; (between the ten-ita and the ji-ita) kaku no gotoki mo yoshi (如此モヨシ)⁴; kore ha Sōho no Shi-un nado (コレハ宗甫ノ紫雲ナド)⁵.]

_________________________

◎ This appears to be another version of the arrangement that was shown in part 13*, where usucha will be served (to a special guest†) at the beginning of the gathering‡.

This practice of offering a bowl of usucha** to the guest (or guests) at the beginning of the gathering survives in the modern tea world only at the night gatherings hosted with the ro††, where usucha is served to the guests first (this is called zen-cha [前茶], “meaning tea [served] before [the sumi-temae, which technically begins the gathering]”). Apparently, in the early days, it was done more frequently -- especially when a guest of high rank had been invited -- as an expression of the host’s solicitude for his guests.

I would like to add that the above interpretation is not supported by the commentators, who assume that both varieties of tea are koicha. They do not explain, however, why the sasa-mimi, then, is not tied in its shifuku -- though this is probably the result of their having learned that the purpose of the shifuku is to protect the chaire‡‡. For those readers who would prefer not to be troubled by my own speculations, they can take this entry to be a case where two kinds of koicha are being served in succession during the goza -- though, in this case, the logistics and mechanics may be difficult to comprehend (and, indeed, neither of the commentators even tries to make sense of these things). __________ *That post was titled Nampō Roku, Book 5 (13.1): the Arrangement [of the Daisu] During the Shoza when [Receiving a] Respected Guest, Part 1. Its URL is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/620572177833623553/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-5-131-the-arrangement-of

As was also true of the arrangement discussed in part 13, the present entry seems oddly out of place -- the fact that it makes reference not to the preceding entry, but to the one before that, is very curious. In both instances, it almost seems as if these two arrangements were simply inserted where there was space to do so. Also, the mention to the Shi-un sasa-mimi chaire [紫雲笹耳茶入], which was owned by Jū Sōho [重宗甫; dates of birth and death unknown, though he seems to have been a somewhat younger contemporary of Rikyū], suggests that at least part of this entry was added long after Jōō’s death.

†During the period in which this collection of sketches was prepared (Jōō‘s middle period), a dai-temmoku was used primarily to serve tea to a nobleman. The various kijin-date [貴人点] forms of temae that have been included by many modern schools in their respective curricula since the Edo period are a continuation of this practice -- as a class, the institution of such temae became necessary once the machi-shū started to use antique dai-temmoku among themselves, as a way to appreciate these rare and costly utensils.

While such usages, directed at appreciating these special utensils privately, were probably being indulged in by Jōō’s contemporaries as well, at that time the primary purpose of the dai-temmoku remained to serve tea to a nobleman (indeed, Rikyū’s censure of Kimura Shigenari for apparently wishing to learn the gokushin-temae so that he could perform it “privately,” shows us just how strong the feeling of revulsion was against using these kinds of temae for any purpose but the service of a high nobleman -- even at the very end of the sixteenth century).

‡To refresh him after his difficult journey to the host's residence -- this is a parallel to the way that guests are provided with hot water (and usually some sort of flavoring, such as kōsen [香煎]) in the yori-tsuke [寄り附] when they arrive for a modern chaji.

**In the present day, it is usually served as sui-cha [吸い茶], meaning that a single large bowl of usucha is passed around, with each guest drinking some. While this is the modern way of doing things, it seems that in the early days, each guest was served a bowl of usucha in much the same way as they are during the goza.

††The practice of zen-cha [前茶] is sometimes explained as being born from the desire not to waste the hot water in the kama. Traditionally -- and even now, at least in theory -- the ro was set up at dawn, with the fire being added to in mid-day, to keep the kama hot until dusk, at which time the ro was cleaned and a new set of charcoal put in (the purpose of which was to maintain the kama in a sub-boiling state until it was time to close the tearoom for the night).

At dusk, the kama was supposed to be taken out to the mizuya, cleaned, and refilled with cold water, while the ro was emptied, sprinkled with a layer of shimeshi-bai, and a new set of charcoal was arranged around some of the embers that remained from the dawn fire. Since this was supposed to be winter, when the temperature would drop quickly once the sun had set, the idea seems to have been to help the guests warm up by serving them a bowl of usucha (which, even as late as the early Edo period, was considered to be ordinary drinking tea) before discarding the hot water, since it could take up to an hour before the kama would return to a boil -- if they came at the time when this replenishing of the ro was done.

Then, as now, the guests were usually invited to come somewhat later than dusk, for an evening chakai. But now, the host leaves the ro unattended until they arrive, so that he can serve them zen-cha [前茶] (or, more usually, puts the fire into the ro in mid-afternoon, so that it will be starting to fail around the time that the guests are expected to arrive). Some schools also prescribe this practice for the dawn gathering (even though it was traditionally said that water should not remain boiling in the kama overnight).

‡‡If this was their thinking, then displaying the sasa-mimi without its shifuku may have been understood as a step in the direction of wabi -- the sasa-mimi being a more “wabi” sort of tea container than the original ko-tsubo and katatsuki that were used in the early days (the sasa-mimi -- along with the other unorthodox objects occasionally seen as tea containers, such as the yu-teki [油滴], sui-teki [水滴] or su-teki [酢滴], te-kame [手瓶], and tsuru-tsuki [弦付] -- was first used as a chaire by the machi-shū, during the early decades of the sixteenth century).

According to Rikyū, however, the purpose of the shifuku is to protect the matcha -- by pressing the lid tightly against the mouth of the chaire (this keeps the volatile components from being lost). Following his death, teachings such as this were lost, however; so when the chajin of the early Edo period were asked about this idea, they assumed that the teaching was truncated, that it originally meant that the shifuku (which is made of two layers of soft silk, padded with cotton in between) was made to help protect the chaire, and this is the way the teaching has come down to us today via the modern schools.

The other commentators, as products of their age, were also unfamiliar with this teaching, and assumed that the present arrangement was concerned with the service of two varieties of koicha during the goza -- even though the sasa-mimi is not tied in its shifuku.

¹Sasa-mimi ・ ni shu ・ ichi wan kazari nari [サヽ耳・二種・一碗飾也].

“This is the display of the sasa-mimi ・ two kinds [of tea] ・ [and] one bowl.”

As in the previous two arrangements, here, once again, we are shown an arrangement where two containers of matcha are displayed together -- in this case with one chawan.

²Ni no cha [二ノ茶].

“The second [variety of] tea.”

This is the tea contained in the “other” chaire -- whether it is a Japanese-made katatsuki, or a lacquered piece such as a large natsume, it will be tied in its shifuku, since the tea it contains will be used to serve koicha during the goza.

³Ichi no cha [一ノ茶].

“The first [kind of] tea.”

This refers to the tea in the sasa-mimi. Because this chaire is not tied in a shifuku, the tea that it contains will be served as usucha. Since the note states that this tea will be served first, this implies that the usucha will be served at the beginning of the shoza, before the sumi-temae, using the temmoku that is displayed together with it on the ten-ita*.

The sasa-mimi is clearly arranged as a mine-suri [峰摺り] in this sketch.

A chaire-bon should be brought out from the katte for the sasa-mimi when it is lowered to the mat. ___________ *Because the temmoku is without a shifuku, and has the chakin, chasen, and chashaku arranged on it, a kae-chawan should not be used.

During the goza, perhaps the same dai-temmoku will be used, or perhaps (depending on the breadth of the host's collection) a different temmoku-chawan will be prepared for the service of koicha.

⁴Kaku no gotoki mo yoshi [如此モヨシ].

This refers to the previous instance (Part 27*) where a hadaka sasa-mimi and another tea container were displayed on the ten-ita.

In that earlier case, the sasa-mimi was displayed on the end-most kane on the right side of the ten-ita, which indicated that its tea would be served last. Here, the sasa-mimi is displayed on the central kane, which suggests that it will be used to serve tea first. __________ *This was the post entitled Nampō Roku, Book 5 (27): Arrangement of the Sasa-mimi and a Taikai at the Same Time, Together with One Bowl. The URL for that post is:

http://__________________________

⁵Kore ha Sōho no Shi-un nado [コレハ宗甫ノ紫雲ナド].

"This is Sōho’s ‘Shi-un’ [sasa-mimi], and other [chaire] of that sort."

Sōho refers to the Sakai machi-shū chajin Jū Sōho [重宗甫; his dates of birth and death are not known]. Together with Rikyū, Sōho was one of Hideyoshi's eight tea officials (sadō hachi-nin-shu [茶頭八人衆]). Since he later served Ukita Hideie [宇喜田秀家; 1572 ~ 1655] in a similar capacity (apparently after Hideyoshi's death), he would seem to have been a somewhat younger contemporary of Rikyū's -- who also managed to escape the odium that destroyed the lives of many of the other Sakai machi-shū chajin who waited on Hideyoshi. Sōho is mentioned as one of the guests at several of Rikyū's tea gatherings, and he also seems to have occasionally been one of Rikyū's fellow guests at gatherings hosted by other machi-shū chajin.

Sōho's yagō [屋號] was Kushiya [櫛屋] (so he is sometimes referred to as Kushiya Sōho [櫛屋宗甫]). His name is also mentioned in the Tennojiya Kaiki [天王寺屋會記].

As he seems to have been a little younger than Rikyū, this comment was probably added to the sketch later, though whether by Nambō Sōkei, or by someone in the early Edo period (who wished to associate the Shi-un sasa-mimi with this document for some reason -- the machi-shū considered this sasa-mimi to be one of “their” meibutsu in the early Edo period; unfortunately, it seems to have been lost), cannot be known.

The Sōho-dana [宗甫棚] (above), which Rikyū used at least fifteen times during chakai that he hosted from the end of the Tenth Month of Tenshō 18 (1590) to the beginning of the intercalated First Month of Tenshō 19 (1591), was created by Jū Sōho.

——————————————–———-—————————————————

◎ Analysis of the Arrangement.

Because the temmoku contains the chakin, chasen, and chashaku, this indicates that it will be used to serve the usucha to the special guest.

Immediately after the guests have taken their seats for the shoza, and exchanged greetings with the host, the host returns to the katte and brings out a chaire-bon, which he places on the left side of the utensil mat. Then he lowers the dai-temmoku and rests it temporarily in front of the furo. Then the chaire-bon is moved to the middle of the mat, in front of the host's knees, and the sasa-mimi is lowered onto it. The chaire-bon is them placed in front of the mizusashi, and the dai-temmoku is moved to its left.

After all of the utensils have been arranged on the mat, there is no sō-rei, because this will be a service of usucha.

When this service of usucha is finished, the guests will usually move to a different room for the meal, returning to the room in which the daisu is set up at the beginning of the goza, for koicha. If usucha is not served during the koicha temae, then the guests might move to a different room for usucha.

During the Edo period, this kind of gathering was usually held in an 8-mat shoin, to which was attached a 6-mat kusari-no-ma [鎖の間]. The daisu was set up in the 8-mat room, while a fukuro-dana was arranged in the 6-mat room, with the kama suspended over the ro on a chain. Zen-cha [前茶] was served in the shoin, after which the guests moved to the 6-mat room for the (ro) sumi-temae, followed (in that room) by the kaiseki. After eating the kashi, the guests would go out for the naka-dachi.

When invited to return, they entered the 8-mat room for koicha, and then moved on to the 6-mat room for usucha.

Unfortunately, the way gatherings such as this were conducted during the preceding century (especially around the time when Jōō was compiling the collection of sketches that make up Book Five of the Nampō Roku) is not well documented -- though the use of multiple venues does not seem to have been an established practice*.

As with part 13, which also was concerned with the service of zen-cha [前茶], it is possible that these entries were added during the Edo period, and so were not originally part of Jōō's collection of arrangements for the daisu. ___________ *The earliest mention of the guests moving to a separate room for the kaiseki, and then for usucha at the end of the goza, appears concurrently with the ichi-jō-han [一疊半] room (and so in 1554 or 1555), which setting is shown below. In this case, the move was born of necessity, since the 1.5-mat room is simply too small (particularly when 3 guests are being received) for the host to be able to serve them appropriately (due to the presence of the sode-kabe -- which was necessary to protect the guests from any sparks erupting out of the ro -- it would not be possible for the host to pour sake for the guest seated closest to the nijiri-guchi, for example, or otherwise serve anything to that guest with his own hands). Thus, a 6-mat katte was attached to this kind of room, with the kaiseki, and later usucha, being served there, while the ichi-jō-han was used for the sumi-temae and the service of koicha.

It is, of course, possible that this may have been based on an earlier model that was devised for use with a pair of larger rooms; but if so, the earlier case was not documented by the chroniclers of the wabi tradition on whose writings we rely for information about chanoyu in the early period.

Nevertheless, since the chakai in the form of

sumi-temae ・ kaiseki ・ kashi ・ naka-dachi ・ koicha ・ usucha

did not exist before Jōō’s middle period, and that Jōō only used a room of 4.5-mats during that time, it is safe to say that the above-described use of an 8-mat shoin and its 6-mat kusari-no-ma for a chakai was based on the model of the ichi-jō-han and its 6-mat katte, rather than the other way around.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

亂世中的特別暖訊2

Neil Young在9號發布 〈Shut It Down 2020〉MV,內容有Neil Young和Crazy Horse在Colorado雲端工作室一起演奏的片段,穿插學童戴著口罩上學、因隔離無法肢體接觸的夫妻、無人的街道和空曠的球場等畫面,傳達出整個世界受到新冠病毒侵擾的樣貌,使得2020年的運作似乎都為此停擺(shut down)了。

youtube

原文出處:樂手巢

Neil Young並在官網推出線上節目《Fireside Sessions》,不定時發布宅居演出,在火爐前彈鋼琴、撥吉他,大大的狗就趴在木質地板上。並釋出一些珍貴片段,像是賈木許所拍下 你看見過死亡的顏色嗎? 配樂的錄製過程, Neil Young邊看投在牆面上的電影,一邊叼著菸、一邊撥著弦。

U2主唱Bono看見義大利人於封城期間,在屋頂演奏音樂鼓舞其他市民,將這段感觸寫成歌詞並分享給The Black Eyed Peas主唱will.i.am,他深深被歌詞觸動,攜手與X Japan團長Yoshiki、Jennifer Hudson合作,線上共同完成〈#Sing4Life〉這首新歌。

youtube

原文出處:樂手巢

Jamie xx睽違五年發表新作,他因長時間無法產出任何作品備感沮喪,嘗試跳脫出執著的想法後,這首歌也成了他抑鬱的出口。他希望在這需要居家隔離,無法出門派對時,這首歌同樣能成為大家的出口。

youtube

總能touch到靈魂的Bon Iver則捎來新作,告訴人們Please don't live in fear,There will be a better day

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

十二年目の少年

ヴィクトルは年末に長谷津の勇利のもとへ帰った。ロシア選手権も全日本選手権も終わり、次はそれぞれヨーロッパ選手権と四大陸選手権が待ち構えていたが、束の間の休息を味わいたかったのだ。 勇利と離れていた期間は一ヶ月にも満たず、再会については何も大騒ぎするほどのことでもないはずだったけれど、空港で彼を見たときヴィクトルは激しい胸のときめかしさに度外れなほど興奮し、思わず抱きしめて無言になってしまった。勇利は笑って「どうしたの?」とヴィクトルの背をかるく叩いた。 「飛行機で疲れちゃった? すぐうちに帰って温泉に入るといいよ。温泉、久しぶりでうれしいでしょ?」 もちろん温泉は魅力的だったけれど、ヴィクトルが求めているのは勇利ただひとりなのだ。それを勇利はちっともわかっていないのだった。 「勇利……」 「なに?」 ヴィクトルは勇利の手を握り、熱心に彼のごく平凡な面立ちをみつめた。本当は勇利は平凡なんかではなく、この世界の誰もかなわないほど彼が輝くことをヴィクトルは知っていた。ヴィクトルは勇利から離れてから、大切な彼が誰かに奪われはしないかと、いつだってつまさきだつ思いだった。 「会いたかったよ」 ヴィクトルが指先に接吻すると、勇利はまっかになってあたりをきょろきょろと見まわした。そのしぐさが幼く、おそろしくかわいらしくて、ヴィクトルは胸が苦しくなった。 「ちょっと、そういうのはふたり���けのときにしてよ……」 「う……」 「ど、どうしたの!」 「大丈夫だ。ただ��めまいと心臓の痛みが……」 「心臓の痛み!? ぜんぜん大丈夫じゃないじゃない!」 「大丈夫なんだ。心臓は勇利しか攻撃してこないんだ」 「ぼくが……!? なんだかかなり野蛮な人間みたいだけど……」 「そういう意味じゃないんだ」 「よくわかんないけど、早く帰ろう。疲れてるんだよ」 ちっとも疲れてはいなかった。勇利と会うために来たのに、疲れるなんていうことがあるだろうか。ヴィクトルは元気いっぱいに年末を過ごし、勇利と愉快に新年を迎え、日本式の正月を体験した。すばらしい日々だった。ロシアへ戻りたくない、と思った。もうヴィクトルの暮らしは勇利がいなければ立ちゆかないのだ。 長谷津にずっと住もうかな、とヴィクトルはぼんやり考えた。しかしそれが最良の選択ではないことを彼は知っていた。ヴィクトル自身にとっては最良だけれど、全体を見ればそうはいくまい。長いあいだロシアのスケート連盟が言うことを無視してきたので、今後はきちんと応じなければならない。自分ひとりのことならまだいいが、勇利にまで何か悪い影響があっては大変だ。 「勇利……」 「ん? どうしたの?」 ヴィクトルは、無邪気な様子で自分をみつめる勇利のあどけないおもてをいとおしそうに見た。ヴィクトルを全面的に信頼し、愛情を寄せている瞳である。この可憐さは絶対に守らなければならない。 「来季のことなんだけど……」 ヴィクトルは胸苦しさをおぼえながら口をひらいた。 勇利は故郷を愛している。わかりやすく、ふるさとが好き! とあけっぱなしの愛を示しているわけではないけれど、確かに愛しているのだ。複雑な、なんとも言いがたい難しい愛ではあるが、だからといって長谷津がどうでもよいということではない。勇利はこの土地で生まれ育ったのだから。そしてここにいる者たちも、勇利のことを愛している。だからヴィクトルは、簡単に勇利を連れ去ることはできなかった。勇利には勇利の世界がある。けれど……。 「俺はここにはいられないんだ」 ヴィクトルはつらい気持ちで打ち明けた。ソファでマッカチンと戯れていた勇利は目をまるくし、それからうなずいて微笑した。 「うん、それはわかってるよ」 「ごめん……」 「いままでが恵まれすぎてたくらいだからね。ぼくの居場所で、ヴィクトルをひとりじめできたんだ。これ以上わがままは言わないよ」 「将来的にはわからないよ。いますぐは無理というだけで、またきっと戻ってこられる。俺は長谷津が大好きだし……」 「うん」 勇利はにこにこ笑っていた。だがヴィクトルは、彼がヴィクトルの言葉を信じていないような気がした。ヴィクトルのことは信頼しているのに夢のある未来は信じない。まるで、期待しすぎたらあとでがっかりするから、とでもいうように。 「本当だよ」 ヴィクトルは熱心に言った。 「本気だよ。俺はまた長谷津に来るよ」 「そっか」 「信じてないだろう」 「そんなことないよ」 ヴィクトルはじれったかった。どうにかして勇利に「うん��また一緒にここで暮らそうね」と言わせたかった。しかしいまのヴィクトルのいちばんの使命は、遠い未来の約束をすることではない。それに勇利だって、口だけでいくら言われたって、よりどころがなければうなずけないだろう。そういうことは、これから時間をかけて教えてやればよいのだ。 「こんなふうにお正月とかさ、お盆とかは帰ってきてよ。あ、ロシアってお盆関係ないのかな? 日本はね、お盆は帰省の季節っていう感じで、まあぼくはいままでお盆だからって帰ったことはないけど、というかお正月だって帰らなかったし、ずっとデトロイトでね……」 「勇利、聞いてくれ」 ヴィクトルは勇利の手を握った。勇利はきょとんとして、それからくすっと笑い、「どうしたの?」と優しく尋ねた。 「そんなに一生懸命な顔して……。ヴィクトルでもそういう顔するんだね」 「長谷津ではしばらく無理だ。だから俺はロシアに行く」 「わかってるよ。何度も言わないで。さびしくなるから」 「勇利も連れていきたい」 ヴィクトルが口早に宣言すると、勇利が大きな目をみひらいた。ヴィクトルは、もっと洗練された様子で、完璧にエスコートするみたいに告げるつもりだったのだが、そんな決心はどこかへ吹き飛んでしまった。彼はみっともなく、事態が差し迫ったように何度も言った。 「勇利とロシアで暮らしたい。ぜひ暮らしたい。俺についてきてくれ」 「…………」 勇利が困ったように目を伏せた。ヴィクトルは慌てた。 「かるい気持ちで言ってるわけじゃない。簡単に言ってるわけでも。勇利が長谷津を愛していることは知ってるし、みんなが勇利を必要としていることもわきまえている。よくよく考えた。勇利を連れていくことは、みんなから希望を奪い去ることなんじゃないかってね。でも、わがままでひどいけど、たとえそうだとしても、俺はおまえを連れていきたいんだ。こんなことを言ったら、勇利は俺にがっかりしたりあきれたりするかもしれないけど、でも本心だから言うよ。俺ひとりでは、もうどうあっても生きていけないんだ。ほかの誰でもいけない。勇利がそばにいなければ」 勇利は返事をしない。彼はうつむきがちになり、なにごとか考えこんでいる。 「もちろん二度と帰さないなんて言う気はないよ。こんなふうにお正月にはまた帰省しよう。それから、えっと、なんだっけ、the Buddhist All Soul's Day……?」 ヴィクトルには「お盆」のことがよくわからないのだった。勇利はなんと言っていたっけ? 「the Bon Festival……? オボン! そうそう、オボン! オボンの時期に帰るんだっけ? いいよ、付き添おう。ほかにも勇利が帰りたいときは帰ればいい。俺も付き合う。実家に帰らせていただきますっていうのはだめだけど」 ヴィクトルは、日本にいるあいだに得た知識を披露し、続けて言いつのった。 「でも勇利が帰りたいときに帰っていいんだよ。あとは、そう、アイスショーなんかもあるしね。勇利、呼ばれるだろう? 日本のアイスショーはさかんだ。俺だってきっと招待される。全部了承するよ。一緒に帰ってこよう。つまり、何が言いたいかというと、ロシアから帰さないということじゃなくて、勇利に日本を捨てろということでもなくて、ただ俺のところへ来て��しいっていうことであって、来季からは俺とロシアで一緒に暮らして欲しいということであって、もしかして俺、何度も同じことを言ってる? 混乱してるんだ、すまない。勇利、なぜ黙っているんだ? 俺の気持ち、伝わってないのか? それとも勇利は……俺と……」 暮らしたくないのか、というひとことは言えなかった。ヴィクトルは口を閉ざし、恐怖をおぼえながら勇利をみつめた。勇利ほどこころの奥底の見抜けない青年はいない。何を言い出すかわからないのだ。ヴィクトルはもうそれを体験し、身に染みるほど知っている。 「勇利……」 ヴィクトルは不安そうにつぶやいた。勇利は口元に慎ましやかに手を当て、相変わらず思案にくれていた。 「何か言ってくれ……」 「……ヴィクトル」 勇利は目を上げると、まっすぐにヴィクトルを見た。その決意のほどのうかがえるまなざしに、ヴィクトルはどきっとして息をのんだ。 「すこし待って」 「え?」 「ちょっとだけ待ってくれる? 支度があるから」 「し、支度ってなんだ……」 はいかいいえで答えられる質問に、何の支度をするというのだろう。また勇利が変なことを言い出した。ヴィクトルはふるえ上がった。 「明日……、ううん、たくさんあるから三日くらいかかるかな……、三日後、見せたいものがあるんだ」 見せたいもの。ヴィクトルはびくびくした。 「なに……?」 「たいしたものじゃないよ。でもヴィクトルは衝撃を受けるかもしれないもの」 勇利は控えめにほほえんだ。 「返事はそのあと……。そもそも、ヴィクトルが言い分を取り下げるかもしれないし……」 「え? なんのことだ?」 「……すべては三日後」 勇利は優しく言ってヴィクトルの手にふれた。 「今日はその話はもうやめよう」 「勇利、俺、落ち着かないんだけど」 「すこし待って」 勇利はくり返すと指を一本立て、ヴィクトルのくちびるに押し当てた。 「ぼくはもしかしたら、ヴィクトルにふさわしくない人間かもしれないよ。まだ貴方は本当のぼくを知らないんだ」 謎のような言葉を勇利はささやいた。勇利はわからないのだろうか? そんなふうに言われたら、ますますおぼれてしまうというのに。 それから勇利は三日間、時間をみつけては部屋へこもり、何か作業をしているようだった。ヴィクトルが「何をしてるんだい?」と訊いてもかぶりを振り、「約束の日にわかるから」としか答えなかった。ヴィクトルはそわそわした。いっそのこともうさっさと断ってくれ、と思ったけれど、実際に断られたら頭がおかしくなることもよくよくわきまえていた。 長い三日が過ぎ、その夜、勇利はヴィクトルの部屋をおとなった。待ちわびていたヴィクトルは緊張しきり、かしこまってソファに座った。勇利は大きな、ひと抱えもある菓子箱を持っていた。のんきに菓子をつまみながら話そうというのか、勇利は本当に無神経だ、とヴィクトルはあきれた。 「ヴィクトル、これを見て」 勇利が厳粛な顔つきで言った。 「お菓子の箱だね」 ヴィクトルは答えた。 「勇利はまたこぶたちゃんになりたいのかい?」 「中身はお菓子ではありません」 勇利はしかつめらしくかぶりを振った。 「これを読んで、それでもぼくをロシアへ連れていく気があるかどうか……。考えて欲しいんだ」 ヴィクトルは不満をおぼえた。 「勇利……、俺は今日、返事を聞けると思っていたんだよ」 「返事をするとは言ってないよ。そもそも、ヴィクトルにその気が��くなったら、ぼくが何を言ったって意味がないからね。たぶん、これを見終わるころには、ヴィクトルはもういいっていう気持ちになってるはずだよ。あんなことを口にした自分が恥ずかしい、って自分にがっかりして、勇利がこんな子だとは思わなかった、ってぼくにもがっかりするかも」 「勇利、何を言ってるんだ?」 「でも……、」 勇利は溜息をついた。 「コーチではいてもらいたいな……。それだけはあきらめたくない。ヴィクトル、どんなにぼくが薄気味悪くても、コーチはやめないでね」 ヴィクトルは、勇利の言うことがさっぱりわからなかった。勇利のコーチをやめるはずがないし、そんなことはあり得ない。しかし勇利がそれを心配するほどのものがこの箱の中に入っているのかと思うと、好奇心がわき上がってきた。 「ぼくは部屋にいるから……」 勇利はヴィクトルの膝の上に箱を置き、両手を胸に押し当てて言った。 「もしあの提案を取り消したくなっても気にしないでね。仕方のないことだってわかってるから……」 彼は溜息をつくと、「じゃあ」とさびしそうに部屋を出ていった。ヴィクトルは勇利にそんなかなしそうな顔をさせたことがつらく、いますぐ追いかけていって、「ロシアへ連れていくぞ!」と言いたくなった。しかしそれでは意味がないのだ。中身も気になるし、手早く仕事を片づけよう。 ヴィクトルはそっと菓子箱をひらいた。そして目をまるくした。中に入っていたのは、たくさんの手紙だった。いったい何だろう? ヴィクトルに渡したということはヴィクトル宛てだろうか? とりあえず、いちばん上にあった封筒を取った。たどたどしい文字で何か書いてある。しかし日本語なので読めない。たぶんカタカナというやつだ。勇利に教えてもらったことがあるけれど、記憶を頼りに観察してみたところ、自分の名前であるような気がした。やっぱり俺宛てだ、とヴィクトルは納得した。 早速便せんを取り出してひろげた。そこにも幼い日本文字が並んでおり、ヴィクトルにはまったくわからなかったが、よくよく見ると、余白のところになめらかな筆記体が記してあった。これは勇利の字だ。つまり勇利がこの幼子の手紙を英訳したのだろう。三日間、ずっとそうしていたのだろうか? 誰の手紙だろう? ヴィクトルは英語を読み始めた。 親愛なるヴィクトルへ こんにちは。初めまして。ぼくの名前は勝生勇利です。どこにでもいる日本のフィギュアスケート選手で、十二歳です。 今日ぼくは、ヴィクトルがジュニア選手権で世界一になるところを見ました。とても綺麗で、かっこうよくて、どきどきして、これまで知らなかったような気持ちになりました。スケートクラブにあるテレビで見たのですが、もうそれからずーっとヴィクトルのことを考えています。ベッドに入っても眠れなくて、頭の中がヴィクトルでいっぱいです。ものすごく頬が熱くて、ぼくの中はヴィクトルばっかりになってしまいました。それで、いまこの手紙を書いています。 いつかヴィクトルに会いたいです。そして同じ氷の上に立ちたいです。一緒にスケートがしたいです。その日のために、ぼくはがんばります。 ヴィクトル、大好きです。 それではさようなら。 勝生勇利 「…………」 ヴィクトルはしばらく放心していた。これはなんだ、と思った。想像はできたけれど、なかな��理解が及ばなかった。古い手紙。日本の文字はわからないが、子どもらしいつたなさで綴られていることは伝わった。いまの勇利のなめらかな英語と引きくらべる。文字のうつくしさは変わっても、その素朴さ、こめられたこころは……。 これは、勇利がヴィクトルに初めて書いた手紙なのだ。 ヴィクトルは急いで次の手紙を取り、ひらいて視線を走らせた。手紙は何十通もあった。いや、百通以上あるだろう。彼はむさぼるように手紙を読み続けた。 ヴィクトルへ こんにちは。勝生勇利です。 ぼくは犬を飼い始めました。ちいさなプードルで、ヴィクトルと同じ名前にしました。普段にはヴィっちゃんと呼んでいます。とてもかわいくて、かしこいです。毎日ふたりで寝ています。 ヴィクトルが一緒に暮らしている犬、マッカチンっていうんですね。とってもかわいいです。ぼくもヴィクトルとマッカチンみたいに、ヴィっちゃんと仲よくなりたいです。なれると思います。だってヴィっちゃんはぼくのことが大好きなんです。ぼくもヴィっちゃんが大好きです。 スケートの先生にねだって、ヴィクトルの映像をたくさんもらいました。毎日見ています。かっこいいです。ぼくもヴィクトルみたいにじょうずにすべれるようになりたいです。なります。がんばります。 ヴィっちゃんと一緒に見て、「ヴィっちゃん、ヴィクトルかっこいいね」って言ったら返事をします。ヴィっちゃんもヴィクトルのこと、かっこいいって思ってるのかな? きっとそう。ヴィっちゃんもぼくみたいに、ヴィクトルのこと大好きになると思います。 今日もヴィっちゃんと寝ます。 それではさようなら。 勝生勇利 ヴィクトルへ こんにちは。勝生勇利です。 今日ぼくは、初めてジュニアの大会に出ました。成績はあんまりよくなくて、終わってから悔しくて泣いてしまいました。ものすごく緊張して、普段できることがぜんぜんできなかったです。それに、三回も転びました。先生は、「最初からあれだけできたらたいしたものだよ」って言ってくれたけど、ぼくはぜんぜんそうは思いません。本当に本当に悔しかったです。こんなんじゃヴィクトルと同じ試合になんて出られないです。 明日からまた一生懸命練習したいと思います。早くリンクに行きたい。 ヴィクトルはいつも試合で落ち着いていてかっこいいです。緊張しないのですか? してるのかな? してるけどいつも通りできるんですか? ヴィクトルはすごいです。 今日は自分がみじめで、恥ずかしくて、とてもヴィクトルの映像を見られませんでした。明日からまた見ます。ヴィクトル大好きです。 それではさようなら。 勝生勇利 ヴィクトルへ ヴィクトル! ぼく三位になったよ! トロフィーもらったよ! 年上の選手にも負けなかった! うれしかった! ちょっとはヴィクトルに近づけたかな? もっともっとがんばります! 今日見たヴィクトルの動画、ヴィクトルが四回転で転んでいました。もうちょっとだったのに。ぼくのほうがすごく悔しかったです。ぼくもがんばるので、ヴィクトルもがんばってください。ぼくもいつか四回転が跳べるようになりたいです。 それではさようなら。 勝生勇利 ヴィクトルへ 勝生勇利です! ジュニアで初めていちばんになりました! いちばんだよ、いちばん! ヴィクトルがよく獲るいちばんです! すごくうれしかった! いつもヴィクトルの動画はひとつだけってきめてるのですが、今日は特別にふたつ見ていいことにしました。ご褒美です。 うれしい! 早くヴィクトルと同じ試合に出たいなあ! それではさようなら。 勝生勇利 ヴィクトルへ 勝生勇利です。 ヴィクトル、ぼく試合でぜんぜんだめでした。何もかも上手くいかなくて、めちゃくちゃでした。順位書きたくない。精神面がだめって言われました。ちょっと緊張したら何も��きなくなるって。今日はすごく上手い先輩がいっぱいいて、雰囲気がすごくて、ぴりぴりしてて、こわくて、��技のことが考えられませんでした。こんなんじゃ、いつかヴィクトルに会っても同じことになりそうです。 何も考えたくない……。 順位をちゃんと書いておきます。二十一位でした。 勝生勇利 ヴィクトルへ こんにちは! 勝生勇利です! 今日ぼくは初めてヴィクトルに会いました! ヴィクトルが日本の試合に来たのです! ヴィクトルの演技、見たよ! すごかった! かっこよかったー! 好き! 大好きです! 演技のあと、花を投げ入れました。ヴィクトルね、ぼくのを、ぼくのを拾ってくれたんだよ! 本当! 本当なんだから! ありがとうヴィクトル! ヴィクトルは、ぜんぶ、ぜんぶ最高でした。 大好き! いつか観客席じゃなくて、同じところに立てるようにがんばりますね。 うれしい! 今夜は眠れない! 勝生勇利 ヴィクトルへ こんにちは。勝生勇利です。 ぼくはシニアに上がりました。シニアはすごいのですね。なんだかジュニアとは世界がちがうという感じです。ぎりぎりまでジュニアにいてよかったと思います。ぼくちゃんとやっていけるかなと不安です。試合の結果はよくなかったです。なんだかこわい。 でも、シニアにはヴィクトルがいて、ぼくは、ぼくはやっとヴィクトルと同じところまで……同じじゃないけれど、でも本当に近いところまで来られたのだから、がんばりたいです。がんばります。ヴィクトルと同じ試合に出られますように。でも、同じ試合に出られても、へたくそじゃ恥ずかしいから、もっと練習します。 それではさようなら。 勝生勇利 ヴィクトルへ こんにちは。勝生勇利です。 ヴィクトル! ぼくは今日初めて、競技者としてヴィクトルと同じところへ行きました! 公式練習で、遠くからちらっとだけヴィクトルを見て大興奮して、ちょっと泣いてしまいました。それだけで死にそうになって、コーチに叱られました。 でもね、それで終わりじゃないんです! ぼくが廊下でぼーっとしていたら、後ろから「ちょっとごめんね」って言われて、ぼく邪魔になってるって思って慌てて道を譲ったら、ヴィクトルが立っていて、「ありがとう」ってにこっと笑ったんです。ぼく、ぼく、舞い上がってしまいました! 近くで見るヴィクトルは、最高で、最高で、最高でした!! 大好きです!! 明日の試合、いい成績がとれるようがんばります。 勝生勇利 追伸 あのとき道をふさいでいてごめんなさい。 ヴィクトルへ こんにちは。勝生勇利です。 ぼくは最近、日本のエースだとか言われるようになってきました。自分ではまだまだぜんぜんだめだと思うのに、そんなふうにうわさされるようになってこわいです。 ぼくは日本の大会では優勝できるけれど、世界大会ではへたくそです。勝生は内弁慶だと言われます。自分のところでは威張っているけれど、外では意気地なしだと。 ヴィクトルに会いたいです。 勝生勇利 ヴィクトルへ こんにちは。勝生勇利です。 ヴィクトル。 ぼく、グランプリファイナ��に出られることになりました。初めてのグランプリファイナルです。世界選手権ではヴィクトルに会ったことがあるけれど、グランプリファイナルでは初めてです。ヴィクトルと同じ氷の上で一生懸命戦いたいです。 最近、ヴィっちゃんの調子が思わしくありません。心配です。ヴィクトルのマッカチンは元気ですか? 元気でありますように。ヴィクトルも元気でありますように。 グランプリファイナルで会えることを楽しみにしています。 勝生勇利 ヴィクトルへ こんにちは。勝生勇利です。 ソチのホテルです。今日、ファイナルのフリーが終わりました。ぼくはさんざんでした。知っているでしょうが、最下位でした。いや、知らないかな。ヴィクトルは勝生勇利っていう選手のことなんて興味がないだろうから。 試合のあと、帰るとき、ヴィクトルに「記念写真?」と言われました。ヴィクトルは親切のつもりだったと思います。無視してしまいました。ごめんなさい。 これからどうすればいいのかわかりません。 勝生勇利 ヴィクトルへ こんにちは。勝生勇利です。 今日、ヴィクトルがうちに来ました。長谷津に来ました。なんで……? 混乱してさっぱり意味がわかりません。 どうしてヴィクトルがぼくのコーチになってくれるの? なんで? ぼくのことなんて興味なかった���じゃないの? あの動画のせい? わけわかんないよ……。 勝手にヴィクトルの「離れずにそばにいて」をすべってごめんなさい。 でも、あのプログラム、大好きです。 ヴィクトルのことも大好きです。 ぼく、どうしたらいいんだろう。 勝生勇利 ヴィクトルへ こんにちは。勝生勇利です。 今日ヴィクトルと、初めて、……手をつなぎました。 びっくりした……。 ぼくはまっかになってしまいました。気づいていましたか? ヴィクトルは、なんとも思ってないだろうけど……。 意味なんかないんだろうけど……。 ぼくはそういうの、どきどきするから……。 あんまりしないで欲しいな……。 それでは。 勝生勇利 ヴィクトルへ こんにちは。勝生勇利です! 今日、ヴィクトルにリンクでキスされました! なに考えてんだ! あとになってめちゃくちゃ笑いました。驚かせたいからキスするって何なんだよ! でもヴィクトルらしいなと思いました。じゅうぶん驚きました。 ぼくの四回転フリップには、キスと同じ威力があったんですね! びっくり! 勝生勇利 ヴィクトルへ こんにちは。勝生勇利です。 ヴィクトル、いまぼくには悩みがあります。 このところ、ずっと変なんです。 ヴィクトルのことを考えると胸が痛くて、涙が出てくるんです。 どうしてこんなにずきずきうずくの? ヴィクトル、教えて……。 教えてください。 勝生勇利 ヴィクトルへ こんにちは。勝生勇利です。 今日、ヴィクトルと目が合っただけで赤くなって、何も言えなくなりました。 そのあと、ヴィクトルがちょっと視線をそらしたら、ぼくは嫌われてるんじゃないかと苦しくなって、せつなくて、泣きたくなりました。 そのあとヴィクトルがぼくの手を握ってにっこりしたので、ぼくはまっかになってもじもじしました。 ぼく、頭がおかしいんじゃないかしら……。 ヴィクトル、どう思いますか? 勝生勇利 ヴィクトルへ 本当に、ずっと変なの。 どうしよう……ヴィクトルがそばにいるとずうっとどきどきする。 勇利 ヴィクトルへ こんにちは。勝生勇利です。 空港まで迎えに来てくれてありがとうございます。 うれしかったです。 抱きしめてくれてありがとう。 ぼくはもうすぐ引退するけど、ヴィクトルのことはずっと大好きです。 勝生勇利 ヴィクトルへ ヴィクトル、苦しいよ。 こころをきめたはずなのに、ヴィクトルと別れることを思うとつらいよ。 ひとりになると泣きそうになります。 勇利 ヴィクトルへ ぼくはグランプリファイナルのあと、毎日泣き暮らすんじゃないかと思う。 胸がつぶれそう。 勇利 ヴィクトルへ このところ弱音ばかりで自分がいやになります。 最後なのだからがんばらなければなりません。 ヴィクトルと過ごせる貴重な時間を大切にしたいと思います。 勇利 ヴィクトルへ ヴィクトルとぼくの最後の試合です。 いままで楽しかった。 この八ヶ月間、夢のような時間でした。 ヴィクトル、どうもありがとう。 ぼくをここまで連れてきてくれて、ありがとう……。 貴方を氷の上に返します。 最後に、貴方の首に金メダルをかけたい。 昔から、ずっとずっと、大好きです。 勝生勇利 ヴィクトルへ こんにちは。 勝生勇利です。 ヴィクトル、どうもありがとう。 いつかヴィクトルと同じ氷の上に立ちたいと思ってスケートをしてきたけれど。 同じ氷の上に立ったとき、ぼくはぜんぜんだめで、「記念写真?」なんて言われたけれど。 ぼくは変わりました。 ヴィクトルのおかげで、変われました。 またヴィクトルが同じ氷の上に戻ってくることがうれしいです。 本当にありがとうございます。 ずっとずっと、一緒にスケートをしたい。 もう離れたくありません。 そばにいてくれますか? 大好きです。 勝生勇利 ヴィクトルへ こんにちは。勝生勇利です。 ヴィクトルと踊ったエキシビション、最高でした。 そのあとに続いた夜も、最高でした。 ぼくのこころは貴方のものです。 ヴィクトルと初めて裸で一緒に寝たけど、すごくすてきでした。 次は、最後までしてね。 愛しています。 勝生勇利 百数十通に及ぶその大量の手紙をすべて読み終えたときは、すでに深夜という時刻だった。途中まではつたない日本文字と、勇利が付け足した英文が並んでいたけれど、ある時期からは洗練された英語のみになった。勇利が英語と���得したということだろう。 どの手紙も、勇利の純真さ、きよらかさ、ひたむきさ、純愛が底に流れていて、ヴィクトルは、勇利はあのときこんなことを考えていたのか、こんな気持ちだったのか、勇利はこんな子ども時代を過ごしたのかとさまざまなことを思案した。勇利のことをたくさん想い、彼を感じたかった。ひとつひとつの手紙について話しあいたかった。けれどそれよりも、いますぐにすべきことがあった。 ヴィクトルは丁寧に最後の手紙を箱に戻すと、勢いよく部屋を飛び出した。 「勇利!」 勇利は、夜深けにもかかわらず、きちんとベッドに座ってじっと待っていた。まるで断罪を待つ罪人のように見えて、ヴィクトルはびっくりした。 「勇利、あれ──」 「読んだ?」 勇利がヴィクトルを見上げ、静かに微笑した。 「あれね、ぼくがヴィクトルに出そうと思ってた手紙なんだ。ううん、出すつもりなんてなかったんだけどね。ただ、ヴィクトルに伝えたいこと、ヴィクトルへの気持ちを書き綴ってて……それが習慣になって。ヴィクトルが来てくれてからもずっと続いてたんだよ」 勇利は困ったように眉を下げた。 「十二年だよ」 彼の素朴な言葉がヴィクトルの胸を刺した。 「重いでしょ?」 ヴィクトルは瞬いた。 「気持ち悪いでしょ? あんなにいっぱい、ヴィクトルへの……」 勇利は目を伏せ、どうしたらいいかわからないというように両手を握り合わせた。 「書いてることも、なんだかしつこい感じでひとりよがりだし……。おかしなこともいっぱいあったよね? 恥ずかしいしこわいから、英語のはひとつも読み返さなかったんだ。ひどかったでしょ?」 何を言ってるんだ。ヴィクトルは口をぽかんと開けた。 「ヴィクトル……」 勇利はおずおずと顔を上げ、さびしそうに笑った。 「ぼくはああいうことを考えてる人間なんだよ」 何かをあきらめたように勇利はヴィクトルを見ている。 「あんな……変なことを、ヴィクトルについてずっと考えてたんだ」 「勇利……」 「そんなぼくでも、ヴィクトル、一緒にロシアで暮らせる?」 「…………」 「無理でしょ?」 勇利はすこし首をかたげた。彼は相変わらず控えめな微笑で、何もかもをのみこんだ表情をしている。 「気が変わったでしょ? いいんだよ。本当のことを言って」 「何を……」 「誰だっていやだよ。あんなふうにぐずぐず想われてたら。それも十二年も……」 勇利は何を言っているのだ? ヴィクトルはさっぱり理解できなかった。 「ヴィクトルはぼくがヴィクトルのファンだって知ってただろうけど……、あそこまでとは思ってなかったでしょ?」 勇利は泣き笑いの顔になった。 「いいんだよ。大丈夫。気にしないで。わかってたから」 「…………」 「何も言わずにヴィクトルについていくこともできたけど……、そんなヴィクトルを騙すようなことだめだから……、言わなくちゃって……」 そこで勇利の頬から突然笑いが消え失せた。彼はヴィクトルをすがるようにみつめ、一生懸命に懇願した。 「コーチは続けてくれる?」 「勇利……」 「おねがい……。いまになってこんな気持ち悪いやつだって知らせるなって思ったかもしれないけど……、卑怯だけど……、でもぼく……ぼくは……」 勇利の目からぽろりとおおつぶの涙がこぼれた。 「……ごめんなさい」 「勇利!」 ヴィクトルはびっくりして慌てて勇利を抱きしめた。勇利の身体がびくっとふるえる。 「勇利、何を言ってるんだ!」 「何って……だから……」 「なんで泣く!? 俺が勇利のコーチをやめるわけないだろう!?」 「ほんとに……?」 勇利が涙に濡れたちいさな顔をヴィクトルに向けた。 「これからもコーチでいてくれる……?」 「当たり前じゃないか!」 「…………」 勇利が目を閉じた。 「……よかった……」 彼は洟をすすってぽつんとつぶやいた。 「それだけでじゅうぶんだよ……ありがとう……」 「じゅうぶんなんて言うな!」 ヴィクトルは、勇利は相変わらずわけがわからないし、本当にどうしようもなく手がかかると思った。 「ロシアへだって連れていくぞ! 絶対に連れていく!」 「え?」 勇利がきょとんとした。なんというあどけなさ……。 「あんな手紙を読んだからには、絶対に離さない!」 「え……?」 「もともと手放すつもりなんてなかったけどね! あれでますます決心がかたまった! どこへもやるものか!」 「ヴィクトル……」 「重い? 気持ち悪い? 何を言ってるんだ?」 ヴィクトルは勇利をぎゅうっと抱きしめ、髪に頬を寄せた。 「あんなの、何があっても一生しあわせにするぞっていう決意をうながすものにしかならないじゃないか!」 「えぇ……?」 「勇利……」 「あ、あの、ぼく……」 「勇利、勇利。顔をよく見せて……」 ヴィクトルが熱心に愛を打ち明けているというのに、勇利のほうは腑に落ちないようで、間の抜けてぽかんとした、きわだってかわいらしい表情でヴィクトルをみつめるばかりだった。 「ヴィクトル……なに言ってるの……?」 「おまえが何を言っているんだ」 「ヴィクトルどこかおかしいんじゃない……?」 「おかしいのはおまえだ!」 「…………」 勇利は口元に手を当て、しばし考えこんだ。思案にくれる彼はかわいい哲学者のようで、ヴィクトルは見ているだけでにこにこしてしまった。やがて勇利は真剣な瞳をヴィクトルに向け、ひとつひとつ確かめた。 「ぼく……、ヴィクトルにどきどきしてもいいの?」 「いいよ」 「ヴィクトルのちょっとしたことでせつなくなってもいいの?」 「いいよ。せつなくなんてさせないけどね」 「ヴィクトルのことばっかり考えていいの?」 「当たり前だ」 「ヴィクトルのこと、好きでいてもいいの?」 「むしろそうしてくれないと暴れる」 「ヴィクトル……」 勇利ははにかんで目を伏せた。 「……最後まで、してくれるの?」 「ああ、勇利!」 ヴィクトルは勇利を抱擁し、とりのぼせた夢のような気持ちで熱愛をこめて叫んだ。 「最後までせずになんて、いられないよ!」 勇利がヴィクトルの胸に顔をうめ、甘えるようにすり寄った。ヴィクトルは彼のつややかな黒髪を優しく撫でながら、俺も勇利に手紙を書こうと思った。たくさん書こう。そして、たくさん語ろう。すぐに不安になり、ちょっとしたことでかなしくなってしまう勇利。かわいい勇利。 「あの手紙のこと、いっぱい話そうね」 「あっ、それは恥ずかしい……」 「どうして? 俺はうれしいのに」 「ばか……」 「勇利。これからも手紙を書いてくれ。なんでも話してくれ。きみのことをもっともっと知りたい。勇利は知れば知るほど謎だよ。あんなにすてきな手紙を書く能力があるなんて知らなかった。書いた手紙は、もうしまいこんだりせず、そのたび俺に渡してくれ。俺も返事を書くよ。それに、俺からも書く」 「ほんと……?」 「でも、これだけはいま、はっきりと言葉で伝えておくよ。勇利……」 ヴィクトルは幸福そうに、目のふちを赤くしてにっこりした。 「俺のこころも、おまえのものだ!」 ヴィクトルはロシアへ戻ったが、勇利に会えないあいだ、彼の手紙はものすごいききめを発揮した。すてきな、ヴィクトルをしあわせにする手紙だった。そして同時に、勇利のせつなさ���さびしさを感じさせる手紙でもあった。 勇利がロシアへ来たら、もう何も考えなくていいくらい、たくさん愛してしあわせにしよう。 ヴィクトルはそうこころぎめをした。 勇利はきっと、このうつくしい情緒的な街並みの中、長谷津にいたときと同じくらい綺麗に、みずみずしく笑うことだろう。

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

<ご報告>開催から早いもので1週間。主催メンバーによる「アトリエの丘2018スタンプラリー」プレゼント抽選を行いました。5月にもかかわらず暑かった2日間、慣れない坂を行脚しながらのアトリエ探訪。スタンプラリーに参加されプレゼントにお申し込みいただいた方は、なんと142名!本当にありがとうございました。今回も主催メンバーが見守る中、厳選なる抽選をおこない、7つの「アトリエ賞」が7名様に。そして7つのプレゼントすべてが入った豪華「アトリエの丘賞」が1名様に決まりました。我がガチャリティ賞は「捕獲ビックモフモフスキー」!さっそく当選された方へ今日発送させていただきます(発表は発送をもってかえさせていただきます)。どうかたのしみに! #アトリエの丘2018 #Sougyoan #銅版画作家 #原田裕子 #SevensTail #北島亮子 #高木茉莉 #Ribbonbinden #クラフトリボン #後藤孝子 #Zooz #平野友夏理 #テキスタイル長尾 #長尾佳子 #Homebase #ガチャリティ #モフモフスキー #ビックモフモフスキー #taisetsustore #工房まる #貴bon #縁工房 (生の松原海水浴場)

#taisetsustore#貴bon#銅版画作家#homebase#sevenstail#後藤孝子#モフモフスキー#工房まる#クラフトリボン#sougyoan#ガチャリティ#アトリエの丘2018#平野友夏理#長尾佳子#原田裕子#北島亮子#ribbonbinden#テキスタイル長尾#ビックモフモフスキー#縁工房#zooz#高木茉莉

0 notes

Text

小さな喫茶店

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8mOu9kAgf0I

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=has1KjbVeU0 “喫茶店”、KISATEN 一辭大約在五十多年前出現在台灣,發源地的

日本早於明治末期, 到了1920年代更成了一時風尚。為什麼稱做

“喫茶店”?在日本的抹茶風習裡面,往往使用了一個中國趙州禪師語錄

中的 “喫茶去”字句以表風雅;猜想就這麼來的。

這另有一個名詞就是 “純喫茶”;這幾個字首先進入耳際,是來自正值

青春年華的表姊。日治時代 coffee shop 的流風遺韻,似乎已經日有

更新,也同時傳入了台灣。在日本早年,不提供酒類,而只有 咖啡、

茶,和一般飲料,雖然沒有酒類,卻有女侍作陪;這當然是搜尋

結果。大約就是等同台灣早年相當風行,燈光黑暗,剛進入伸手

��見五指,有女服務生坐枱的咖啡廳:南國佳麗、北國妖姬 -這是

門口的招牌。

據個人在慘綠少年時代的 經驗 ,第一次進入 “純喫茶” 記得是在

中正路,現在的忠孝西路,上到所在的二樓,只見昏暗的燈光中,

一座座擺在茶几後面的雙人沙發,躺滿了對對交纏的海獅。記得

當時年紀小 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KZsLLOUglTo ,

未經世事,不明就裡,所以趕緊小跑步跑路下樓。現在想起來,這些

雌雄海獅們也都已經 80好幾了。

在 “純喫茶”、Kisaten,年輕男女交往、生意人談生意、黑道喬事 . . .;

早年有名稱取自法國作曲家 拉威爾 的名曲 BOLERO ,大稻埕

的 “波麗露”。提供當時不多的 hi-end 音響,讓客人聆賞古典音樂。

不過在日本這類付有餐點供應的稱做 Cafe。這裡也是當年我輩家長

介紹子女相親的重要地點。幾年前去過一次 波麗露。後代前來自我

介紹;老實說,整個店已經走樣,女二代目的談吐很不怎麼樣,甚至

顯得粗俗。一眼看去的顧客,看不到青春也聽不到文雅,更談不上

古典。

從第一代老闆所做整體的呈現來看,受過日本教育,台灣老輩仕紳

世代的教養、儀態,早已隨著時代洪流,一去不返,相當失望。 相同的樣態也發生在台中的 太陽堂。上成功嶺時所見的 太陽堂,

曾經是如此和風高檔,甚久之後的幾年前,在網路所見的報導,

已經是相當破敗。這和生意之如何無關,而是由 “整理、整頓”

而來的美好、浪漫已經失去;文化思維已經不同。

當兵剛退伍,同學在南京東路一段頭開了一家 “金咖啡”。應該是

第一家咖啡廳擺上 Grand Piano,有鋼琴演奏,風行一時。不久,

在對面又開了一家 “金琴”,這次的噱頭更不得了,整部鋼琴鍍金。

同學以 Benz 為座駕,有司機案內,真是志得意滿,意氣風發��

年紀大約也就二十三四。這位老兄為人四海,他的家是當時當紅的

電視影星聚居處。時而去湊熱鬧,有次碰到剛出道不久的 余天;

全身有毛,既不會毛茸茸,多如黑熊,也不會毛髮稀疏如同紅

毛猩猩,實在很帥。有次躺在小房間雙層床的上面,下看林松義與

剛出道的余天坐在下面聊天。林松義向余天說,不用急著出國 . . . .。

林松義當然是前輩,只是余天很帥前途不可限量,我想此兄搞不清楚

狀況,有點好笑。還有一次去他的金咖啡蹭流行,神采飛揚的同學

說,來,給你介紹我的女朋友:「 北一女畢業的」。真是癩蝦蟆

吃到天鵝肉,令人五味雜陳。

https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=114370417213271

之後台灣的咖啡廳更有了現場表演,成了所謂的 “西餐廳”。與日本

之後發展出爵士、古典音樂、體育、歌聲 . . . . ,等等配合形形色色

嗜好、興趣不同顧客群,風格各異的 “喫茶店”。充滿著主人家個人

堅持的風情與情調氣氛的 KISATEN 所在多有,由文化底蘊所發展

出來的呈現,日本與台灣各自的走向全然不同。

明治維新 “文明開化” 之後的日本,進入 “喫茶店” have a cup of

coffee,喝杯咖啡還是一種時尚。摩登的感覺,聽下面這一首,曲風

充滿了過著喝咖啡文明生活的昭和時代的興奮與快樂: 一杯 の コーヒー から

作詞 藤浦洸 作曲 服部良一 昭和十四年 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nz-UNcT-W7E

1. 一杯のコーヒーから 夢の花咲く こともある

街のテラスの 夕暮に

二人の胸の 灯火が チラリホラリと 点きました

• 就一杯咖啡 夢的花開了 黃昏街旁的雅座 俩人心中花開朵朵

2. 一杯のコーヒーから モカの姫君 ジャバ娘

唄は南の セレナーデ

貴方と二人 朗らかに 肩を並べて 唄いましょ

• 就一杯咖啡 摩卡公主 多話女郎

歌曲是南方小夜曲 與妳兩人並肩爽朗歌唱

3. 一杯のコーヒーから 夢は仄かに 薫ります

赤い模様の アラベスク

あそこの窓の カーテンが ゆらりゆらりと 揺れてます

• 就一杯咖啡 微微的夢香 那紅圖案裝飾的 窗簾輕輕搖動

4. 一杯のコーヒーから 小鳥囀ずる 春も来る

今宵二人の ほろ苦さ

角砂糖二つ 入れましょか 月の出ぬ間に 冷えぬ間に

• 就一杯咖啡 小鳥啾啾 春來到

今夜俩人的哀愁 放兩顆方糖吧 月出前 未冷間

“喫茶店” 其實也就是 Coffee Shop,有走法國風的就稱做 Café:

C'est Si Bon(It's so good) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7y9hIjH_7do

https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/deanmartin/cestsibon.html

在戰後的昭和時代,隨著經濟的成長,上 コーヒーショップ 成了

人們生活不可或缺的一環,同時也有了幾首以 “喫茶店” 為主題的歌曲

膾炙人口。這一首 “喫茶店の片隅で” 描寫了青年男女談戀愛的情狀。

曲調清純、端正如同論說文,比較像是文部省頒定曲。來自歌詞的

回憶,表現出浪漫的氛圍,也透露著與情人分手後淡淡的傷感,深為

人們喜歡,傳唱。 下面播出兩首以 “喫茶店” 為主題的歌曲,個人都非常喜歡: 喫茶店の片隅で https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EUDNTd1wjRo&t=2s

作詞:矢野亮

作曲:中野忠晴

金合歡街樹的黃昏

喫茶店燈光昏暗

我倆經常相逢的日子

小小的紅色椅子兩張

摩卡香氣 漂溢

靜靜對坐的兩人

聆賞著蕭邦夜曲

流瀉的鋼琴音符

忽急忽徐

不知覺間 夢遠了

難忘昔日情誼

獨自來到 喫茶店

散落窗邊的 紅玫瑰

遙遠過去的懷念

心中深深感觸 呼喚今宵

“ 靜靜對坐”, 理論上氣氛營造的責任應該是在男生。無論是拙於

言辭,詞不達意,或者神遊十三天外,再怎麼說女生平時如何

聒噪,也有必需的淑靜要守,更何況如果是位初嘗年輕男女交往

滋味的黃花大閨女ㄦ,保持羞於啟齒,就是一種最佳的狀態與

表現。如果其實是老於江湖,往往就在這靜默的時分,端詳、

審��對坐這位稚嫩小男生,盤算著接下來要如何宰制、盤剝這頭

難以釋手的小羔羊。

依詞意來看,這位女生正典就是一朵閉月羞花,男生更是個蕭邦迷,

天生應是一對,可惜心中這一點無法言傳的甜蜜,就在一點絲微的

誤會,或者什麼陰錯陽差,終至分手收場。

すき 喜歡 https://iseilio-blog.tumblr.com/post/716133306776911872

有好事之旁觀者,默默好奇,守著觀察,期盼或許男方忽而出現,

演出一場心有靈犀的巧遇,終至喜劇收場。真要這麼說來,這首

論說文式的浪漫歌曲將大形失色。就讓劇情維持無頭無尾,在

主人公默默的心中訴說之間,主客共享這份幽微的情誼與遺憾。

日文歌詞練習:

アカシア並木 (なみき) の 黄昏(たそがれ)は

淡い灯 (ひ) がつく 喫茶店

いつも貴方(あなた)と 逢 (あ)った日の

小さな赤い 椅子(いす)二つ

モカの香 (かお)りが にじんでた

ふたりだまって 向き合って

聞いたショパンの ノクターン

洩(も)れるピアノの 音(ね)につれて

つんではくずし またつんだ

夢はいずこに 消えたやら

遠いあの日が 忘られず

ひとり来てみた 喫茶店

散った窓べの 紅(べに)バラが

はるかに過ぎた 想(おも)い出を

胸にしみじみ 呼ぶ今宵 (こよい)

這一首曲風輕快,可惜影片過於久遠,影像模糊,鑑賞功力全憑

個人才華。

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lhFfVuHkqx8 小さな喫茶店

拘謹有禮而古板的日本人,有其浪漫與夢幻的一面。 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fhY0-r_2yvQ 日本有 繩文人和 彌生人兩種,以個人看法, 彌生人 的 面孔比較肉餅。這位仁兄人稱: ハムバ-グ 、 漢堡。

拘謹有禮而古板的日本人,有其浪漫與夢幻的一面。 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=voN9-0oeUho 神情與年齡雖然無法對焦,還是可愛,還是唱得不錯、拍拍手。 • 可愛い!お一人ですか?嗚呼 --

作詞:E.Neubach

訳詞:瀬沼喜久雄 作曲:F.Raymond 已經是去年

星光綺麗的夜晚

想起我倆散步的小徑

懷念

過去浮上了心頭

走著走著

不覺煩惱了起來

那是初春的事

進入喫茶店內的我倆

面前擺著茶與蛋糕

一言不語

旁邊收音機甜美的歌聲

輕柔的唱著

就只靜默的我倆

相對而坐嗎

進入喫茶店內的我倆

面前擺著茶與蛋糕

一言不語

旁邊收音機甜美的歌聲

輕柔的唱著

就只靜默的我倆

相對而坐嗎

日文歌詞練習:

それは去年のことだった

星の綺麗な宵だった

二人で歩いた思い出の小径だよ

なつかしい

あの過ぎた日の事が浮かぶよ

此の路を歩くとき

何かしら悩ましくなる

春さきの宵だったが

小さな喫茶店にはいった時も二人は

お茶とお菓子を前にして

ひと言もしゃべらぬ

そばでラジオがあまい歌を

やさしくうたってたが

二人はただだまって

むきあっていたっけね

小さな喫茶店にはいった時も二人は

お茶とお菓子を前にして

ひと言もしゃべらぬ

そばでラジオがあまい歌を

やさしく歌ってたが

二人はただだまって

むきあっていたっけね

台灣人固然騷包,對 “喝咖啡” 這類成了次文化的風尚,情趣其實

不多,個人則還是比較喜歡牢騷滿腹,罵人不帶髒字的政治論說,

卻是往往一知半解,過於充斥還是不好。這日發現弄些歌曲、歌詞,

好好說他一番倒是一個方向;且擱下筆,稍後再敘。

BONUS

二戰前世代的日本人其實比較嚮往浪漫的法國 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UR2Kj1omGAg

枯葉 岸洋子 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=El6kzOS0TKg

すみれの花咲くころ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6VbSufpdUp8

專人桌烤"A5和牛八吃" & 鎮店30年"黃金羊肉爐" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w1S1llWbCgM

2018 舊文

2 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Merci Beaucoup!! ~スウィートデイズ~ - Charleville (Zettai Kouki song) lyrics with translation

NOTE: Song, lyric, and translation by @sanadayuina please DO NOT re-upload/re-translate WITHOUT her permission. If there is any mistake, please reach her directly.

Merci Beaucoup!! ~スウィートデイズ~ - Charleville

Merci Beucoup!! ~Sweet Days♡~

Bonjour! Salut! Salut! 君を愛してもいいかい? Kimi o aishitemo ii kai? Is it alright for me to love you? Bonjour! スゥイートデイズ♡ Bonjour! Suitto Daizu♡ Bonjour! Sweet Days ずっと一緒に生きてゆこう Zutto isshoni ikite yukou Let’s live together forever

君と会えてホントにbonheur Kimi to aete honto ni bonheur It is really bonheur to be able to meet you 愛を囁き 分け合う甘いひと時 Ai o sasayaki wake au amai hito toki The sweet moment when we share whispers of love

つらい時は手をつないで Tsurai toki wa te o tsunaide Let’s hold hands in the hard time さぁ ボン・ボン・ボヤージュ Saa Bon-bon-boyaajyu Here we go, bon-bon-voyage 人生を楽しもう 俺と一緒に Jinsei o tanoshimou ore to issho ni Let’s enjoy live together with me

Merci Beucoup!! 出会えたこと最高に嬉しいよ Merci Beucoup!! Deaetta koto saikou ni ureshii yo Merci Beucoup!! I am really happy that I able to meet you 君と生きてゆく スゥイートデイズ♡ Kimi to ikute yuku Suitto Daizu ♡ I want to live with you, Sweet Days Bonjour!! 甘い 甘い ホイップでデコレート Bonjour!! Amai amai hoippu de dekoreeto Bonjour!! I decorate our live with sweet, sweet whip どんなことがあっても キラキラ 愛をアゲル Donnna koto ga attemo kira kira ai o ageru No mater what happened, I will give you the most sparkling love さぁ 召し上がれ♡ Saa Meshi agare♡ Well then, bon appetite

Bonjour! Salut! Salut! 時にはビターなKissで Toki ni wa bitaa na Kiss de Sometimes with the bitter-taste Kiss Bonjour! スゥイートデイズ♡ Bonjour! Suiito Daizu♡ Bonjour! Sweet Days 君の笑顔を見ていたいよ Kimi no egao o miteitai yo I want to see your smile

月が綺麗だ 美しい人よ Tsuki ga kirei da utsukushii hito yo Look, the moon is beautiful, oo beautiful one 抱きしめたなら 二人だけの世界さ Dakishimeta nara futari dake no sekai sa If we embrace each other, we will find our own world

人と違う価値観 イイんじゃない Hito to chigau kachikan iin jyanai Isn’t it alright to have a different sense of value? もぉ ノン・ノン・トリステス Moo Non-non-torisutesu Geez, non-non-tristes 七色に輝く 素敵な奇跡 Nana iro ni kagayaku Suteki na kiseki The wonderful miracle shine in seven colors

Merci Beucoup!! どんな時もこの手を離さない Merci Beucoup!! Donna toki mo kono te o hanasanai Merci Beucoup!! No matter what happened, I will never let your hand go 君とシェアしたい スゥイートデイズ♡ Kimi to shea shitai Suitto Daizu♡ The Sweet Days I want to share with you Bonjour!! ずっと ずっと 焦がしたブリュレ Bonjour!! Zutto zutto kogashita buryure Bonjour!! The Brulee that always, always, burn down 君を見つめるたびに ドキドキ これ��て恋? Kimi o mitsumeru tabi ni dokidoki korette koi? My heart always beat so fast when I catch you in my eyes, is this love?

気どった素振りでドレサージュ Ki dotta suburi de doresaajyu The Dressage I do with beautiful swing さぁ ガトー・ガトー・オ・ショコラ Saa Gatoo-gatoo-o-shokora Well then, the Gateaux-Gateaux-Chocolat Kissしてくれないかい? とろけるほどに Kiss shitekurenaikai? Torokeru hodo ni Can I kiss you? Until we melted together

とびきりの! Merci Beaucoup!! Tobikiri no! Merci Beucoup!! The most! Merci Beucoup!! 出会えたこと 最高に嬉しいよ Deaeta koto saikou ni ureshii yo I am really happy that I able to meet you 君と生きてゆく スゥイートデイズ♡ Kimi to ikite yuku Suiito Daizu♡ I want to live with you, Sweet Days Bonjour!! 甘い 甘い ホイップでデコレート Bonjour!! Amai amai hoippu de dekoreeto Bonjour!! I decorate our live with sweet, sweet whip どんなことがあっても キラキラ 愛をアゲル Donnna koto ga attemo kira kira ai o ageru No matter what happened, I will give you the most sparkling love さぁ 召し上がれ♡ Saa Meshi agare♡ Well then, bon appetite

Bonjour! Salut! Salut! 君を愛してもいいかい? Kimi o aishitemo ii kai? Is it alright for me to love you? Bonjour! スゥイートデイズ♡ Bonjour! Suitto Daizu♡ Bonjour! Sweet Days ずっと一緒に生きてゆこう Zutto isshoni ikite yukou Let’s live together forever

#charleville#senjyushi#senjuushi#the thousand noble musketeers#zettai kouki song#lyrics#translations#esenya#tachibana shinosuke

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

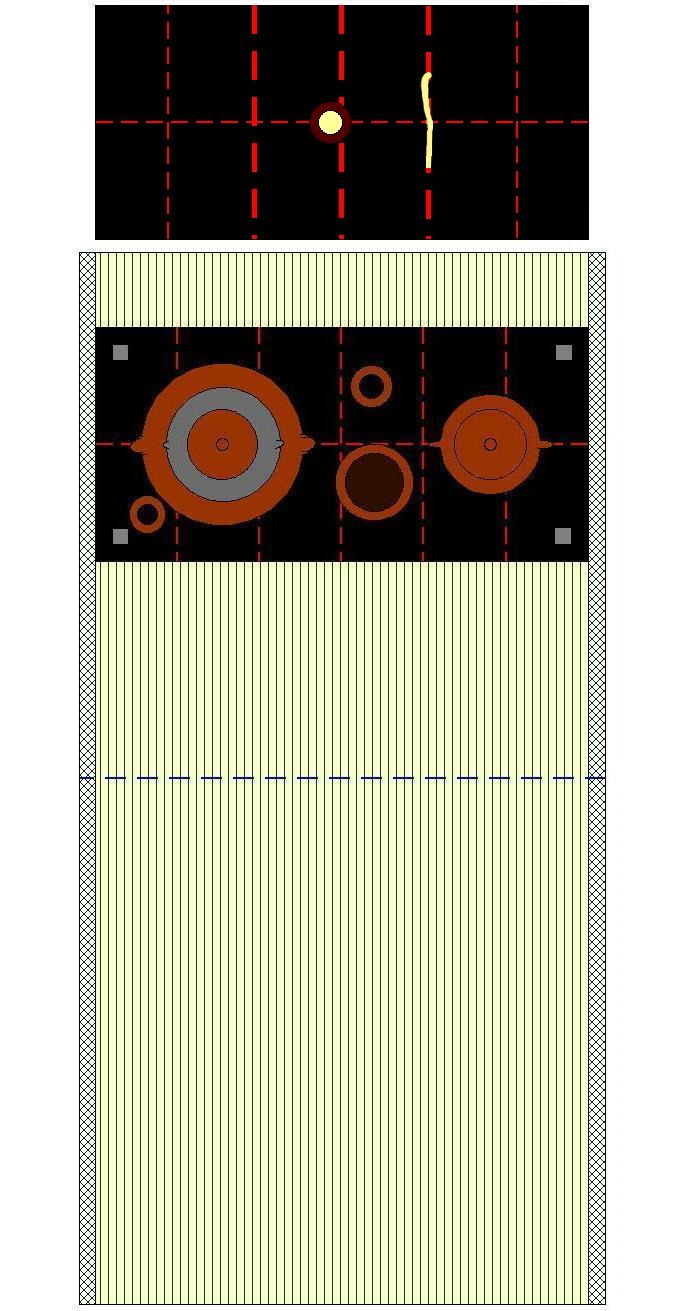

Nampō Roku, Book 5 (15): the Display of Three Utensils on the Nagabon -- the Difference Between Serving Tea to a Noble Guest in Another Place, Compared with Doing So in One’s Own House.

15) Nagabon mitsu-kazari, waga-ya to ta-ke to no chigai nari [長盆三ツ飾、我家ト他家トノ違也]¹.

[The writing reads: (between the ten-ita and ji-ita) shita jo-jō (下如常)².]

The kaki-ire [書入]³:

〇 With respect to the things one has been asked to do [when serving tea to] a nobleman⁴, if this [involves] the arrangement of the tray, it would be best for one to do things as is shown [in the sketch] -- as a gesture of respect⁵.

When one goes to some other place [to serve tea], it is [occasionally] the case where the guest will request [the visiting host] to attend to the arrangement [of the objects on the daisu]⁶. [In this case,] from the way [you] usually [do things] in your own home, the entire line [of objects] should be moved upward into the higher seat⁷.

_________________________

¹Nagabon mitsu-kazari, waga-ya to ta-ke to no chigai nari [長盆三ツ飾、我家ト他家トノ違也].

This is essentially the same nagabon mitsu-kazari that was examined in the previous post*, though here the initial orientation of the nagabon on the daisu is modified to reflect the difference between what is done when serving tea to an important guest in one’s own home, and when doing so elsewhere†.

Some of the details that are mentioned in the kaki-ire (such as making every effort to conform to the requests made by the nobleman) were of extreme importance during the Edo period, and it is possible that this arrangement was added to the collection (by agents of the Tokugawa bakufu)‡ early in the seventeenth century.

As Shibayama Fugen (quoting from Book Six) reminds us that “in our own home, we should put [our] ordinary utensils on the migi-za [右座], so that they overlap their kane by two-thirds; but when serving tea in other places using utensils that belong to other people, or with the utensils that will be used to serve a nobleman, everything should be moved toward the left seat, where they overlap their kane by two-thirds**.” __________ *In the sketch in the Enkaku-ji manuscript, the chaire has been changed from a large katatsuki to a large taikai. As a result, the chaire is shown overlapping its kane on the left, rather than on the right as in the previous post.

†While the title of this entry expressly states “in that [person’s] house,” it also encompasses serving tea to a nobleman anywhere else -- such as in a temple.

‡As has been mentioned before, on several occasions, the entries that appear to have been added seem to feature titles that are written as complete sentences -- that is, they end with the verb nari [也]. The authentic Jōō material apparently does not.

**Tsune no dōgu oki-kata waga-ya ni te ha migi-za no kata [h]e san-bun-no-ni wo yaru, yo-so ni te ha ta-nin no dōgu mata ha kijin no o-dōgu ha hidari-za no kata [h]e san-bun-no-ni yaru-koto nari [常ノ道具置方我家ニテハ右座ノ方ヘ三分ノ二ヲヤル、他所ニテハ他人ノ道具又ハ貴人ノ御道具ハ左座ノ方ヘ三分ノ二ヤルコトナリ].

Tanaka Senshō also mentions this same passage in his commentary.

It must be remembered that, in the Nampō Roku, “right seat” (migi-za [右座]) refers to the left side of the daisu; and “left seat” (hidari-za [左座]) refers to the right side of the daisu.

²Shita jo-jō [下如常ō].

“Below, the same as always.”

³The complete text of the kaki-ire reads:

Kijin no o-dōgu nado ōse ni yotte, bon-kazari nado to araba, uyamaite kaku no gotoki mo yoshi, yoso [h]e iki-taru ni, kyaku yori kazari-sōroe to shomō no toki mo aru-koto nari, jika no yori hitosuji jōza [h]e kuri-agaru nari.

[貴人ノ御道具ナド仰セニ依テ、盆カサリナトヽアラバ、ウヤマイテ如此モヨシ、他所ヘ行タルニ、客ヨリカサリ候ヘト所望ノ時モアルコト也、自家ノヨリ一筋上座ヘクリ上ル也。]

The text will be analyzed sentence by sentence below.

⁴Kijin no o-dōgu nado ōse ni yotte [貴人ノ御道具ナド仰セニ依テ].

O-dōgu nado [お道具など]: o-dōgu [お道具] means the utensils; nado [など] means and so forth, and the rest.

This seems to include both the utensils, and the appropriate method of arranging and using them.

Ōse ni yotte [仰せに依って]: ōse (usually as ōseraru [仰せらる] or ōserareru [仰せられる]) means to say (with reference to something said by a nobleman). It, therefore, has the nuance of a polite command. In other words, the nobleman has asked the person who will be serving him tea to use certain utensils, or arrange (or handle) them in a certain manner. It would be best, therefore, for the host to accede to his request, and conduct everything accordingly.

⁵Bon-kazari nado to araba, uyamaite kaku no gotoki mo yoshi [盆カサリナトヽアラバ、ウヤマイテ如此モヨシ].

“If there is the display of a tray, and things of that sort, it would be best [if this is done] as shown, as a gesture of respect.”

Bon-kazari [盆飾り] can refer to the way that the tray is displayed, as well as to the way that the utensils are arranged on the tray.

Uyamau [敬う] means (to have) deep respect for (someone). Uyamaite [敬いて] would suggest the demonstration of this feeling.

⁶Yo-so [h]e iki-taru ni, kyaku yori kazari-sōroe to shomō no toki mo aru-koto nari [他所ヘ行タルニ、客ヨリカサリ候ヘト所望ノ時モアルコト也].

“Going to another place, there is also the case when the guest asks [the visiting host] to attend to the arrangement [of the utensils].”

Kyaku [客], guest, here refers to the kijin [貴人] (nobleman), to whose house the host has gone in order to serve him tea.

The nobleman wishes to drink tea from his own utensils*, and he asks the visiting host to arrange them as he sees fit. __________ *Contextually speaking, this is not an especially odd request, since the noble classes were often loath to eat or drink from something that might have been used to serve someone whom they consider an underling. This would have been particularly true in a rigidly stratified society such as was present in Japan during the Edo period -- when the hereditary nobles viewed the military class as brutes and usurpers (even when behaving politely to their faces), and the daimyō considered the lower orders (including the lower ranking samurai) barely human.

We must also remember that this person is so important that, if the host wishes to serve him tea, the host has to visit his home in order to do it.

⁷Ji-ka no yori hitosuji jōza [h]e kuri-agaru nari [自家ノヨリ一筋上座ヘクリ上ル也].

Ji-ka [自家] means one's own home.

Hitosuji [一筋] means the (entire) line of utensils -- the utensils are laid out in a horizontal line on the nagabon -- from the dai-temmoku, to the chashaku, to the chaire. The entire line is moved upward (in other words, toward the right*), without any changes to order or spacing. (This is, of course, easily done, since they are all lined up on a tray, so only the tray has to be moved to associate the different objects with the next-higher kane).

Kuri-agaru [繰上がる] means to move up, advance. Since the higher seats are toward the right, the tray is moved to the right, so that the dai-temmoku is associated with the central kane, and the chaire is associated with the second kane on the right. __________ *In the original setting, the katte was located on the host's right, while the guests were seated on his left. Thus, moving things toward the right both made them more inaccessible, and moved them into a cleaner place (since the farther they were from the side of the room where the guests were seated, the less chance there would be of the dust that was raised by the guests' movements, falling on them).

——————————————–———-—————————————————

◎ Analysis of the Arrangement.

This arrangement is essentially the same as the one discussed in installment 14, with the only real difference being that the nagabon has been moved toward the right, so as to associate all of the utensils with the next-higher kane.

As mentioned above, here a large taikai chaire (measuring 3-sun 2-bu in diameter)* has been substituted for the large katatsuki that was shown in the earlier sketch. As a result, the dai-temmoku and chaire are spaced equally†, and in this way are brought into the proper contact with their respective kane. ___________ *This would be the most likely chaire to be owned by a nobleman (who likely was not a chajin), because since the fourteenth century all of the mansions of the nobility would have had at least one o-chanoyu-dana installed (adjacent to the main reception room, if nowhere else), and the large taikai was the usual chaire that was used on the o-chanoyu-dana.

†The space between the left rim and the temmoku-dai, between the temmoku-dai and the chaire, and between the chaire and the right rim, are all equal (approximately 2-sun 5-bu). As a result, the objects can be arranged quite easily visually, and then all the host has to do is correctly orient the tray so that the dai-temmoku overlaps its kane by one-third. This is another good example of how these trays “work.”

1 note

·

View note

Photo

いよいよ第2弾「アトリエの丘2018」を 明日26日(土)と27日(日)開催します。 詳細情報は、Facebookイベントページにて 随時配信中です(検索:アトリエの丘2018)。 <ご来場にあたって> 「アトリエの丘」は みなさまの想像を超える坂の町にあります。 狭く、とても急勾配の坂をめぐるため スニーカーなど”歩きやすい靴”を履いてお越しください。 また、車で離合するのが難しい狭く急な坂道ばかりですので 自家用車でのアトリエ訪問は極力ご遠慮ください。 また、大変ご不便をおかけしますが 今回、十分の駐車場をご用意できておりません。 特に、初日26日(土)の13時までは お停めいただける駐車スペースがない状態ですので ご来場は「公共交通機関」をご利用下さい。 ちなみに、最寄りのバス停は 姪浜駅・今宿駅から発着するコミュニティバス「なぎさ号」の 「生の松原海岸」か「大谷」バス停となります。 運行本数が大変少ないバスですので、時刻表を事前にチェックしお越しください。 http://www.meinohama.co.jp/routes_bus.html それでは、 会場でみなさまとお会いできるのをたのしみにしております。 「アトリエの丘2018」 ◎開催日/5月26日(土)27日(日) ◎開催時/10:00〜16:00 ◎雨天決行 https://www.facebook.com/events/187780065312365/ #アトリエの丘2018 #Sougyoan #銅版画作家 #原田裕子 #SevensTail #北島亮子 #高木茉莉 #Ribbonbinden #クラフトリボン #後藤孝子 #Zooz #平野友夏理 #テキスタイル長尾 #長尾佳子 #Homebase #ガチャリティ #onceface #モフモフスキー #taisetsustore #神田正之 #ムツロマサコ #ノナカフキコ #渡辺せつこ #マルそじるし #フタツの制作所 #goods8083 #フランキー厨房 #工房まる #貴bon #縁工房 #なぎさ号 (生の松原海水浴場)

#工房まる#モフモフスキー#taisetsustore#なぎさ号#onceface#後藤孝子#貴bon#縁工房#アトリエの丘2018#goods8083#フタツの制作所#フランキー厨房#原田裕子#平野友夏理#ノナカフキコ#sougyoan#銅版画作家#ribbonbinden#テキスタイル長尾#北島亮子#渡辺せつこ#クラフトリボン#ガチャリティ#sevenstail#ムツロマサコ#高木茉莉#神田正之#マルそじるし#zooz#homebase

0 notes

Text

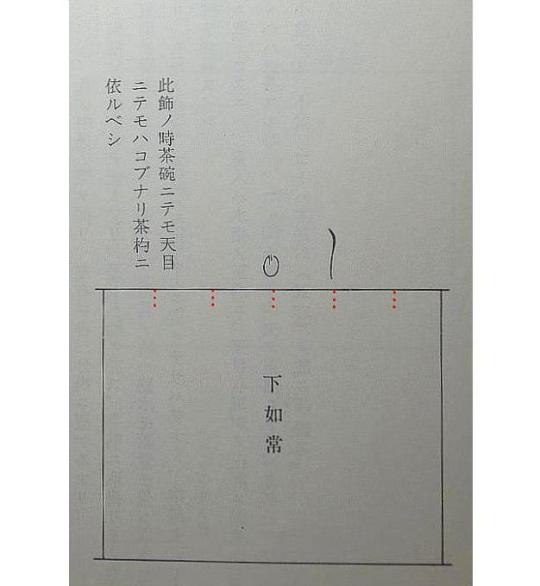

Nampō Roku, Book 5 (4): the Ordinary Way to Display a Chaire and a Chashaku.

4) Tsune no chaire・chashaku kazari [常茶入・茶杓飾]¹.

[The writing reads: (above the daisu) kono kazari no toki chawan ni te mo temmoku ni te mo hakobu nari (此飾ノ時茶碗ニテモ天目ニテモハコブナリ)², chashaku ni yoru-beshi (茶杓ニ依ルベシ)³; (between the ten-ita and the ji-ita) shita jo-jō (下如常)⁴.]

_________________________

◎ This is the first of eight arrangements* that are not found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript of the Nampō Roku; nor are these found in Tachibana Jitsuzan’s original copy of the Shū-un-an documents as published in the Gunsho Ruijū [羣書類]†. However, this does not mean that they are spurious. During Jitsuzan’s lifetime, four copies of the Enkaku-ji manuscript are known to have been made (this was done officially, with permission given by both Jitsuzan, and the Abbot of the Enkaku-ji -- probably with the intention of reducing wear and tear on the original document), and it was from the lineage of one of these that Shibayama Fugen’s source material derived.

Their absence from the other sources might be supposed to be the result of the fact that these kinds of arrangements -- though similar things are found in some of Rikyu’s densho -- were of a sort that was not approved by the Senke; and it may have been someone acting on their interests that was behind its removal‡.

As for why they are not found in the published version of Jitsuzan’s original collection of notes**, the Gunsho Ruijū was published in An-ei 8 [安永八年] (1779). This was a little less than a century after Tachibana Jitsuzan finished work on the presentation copy of the Nampō Roku. It would seem that the kiri-kami for this arrangement (as well as pages documenting several other arrangements) was removed rather early on, perhaps not long after Jitsuzan’s death (in 1708), and so was already absent when the editors of the Gunsho Ruijū applied to the Tachibana family for access to their documents.

Be that all as it may, I will go through these “missing” arrangements in this translation, primarily because they more logically lead from the bon・dai kazari to the nagabon kazari (and so can be considered as a sort of “wari-geiko” for the highest temae††). ___________ *From this part of the book. For some reason, this block of arrangements were apparently removed as a unit. Other arrangements have been removed from other parts of the book, but this is the most serious incident of what might be considered pro-Senke “censorship” (if that is what it, in fact, was).

†The block-printed facsimile edition was based on Jitsuzan’s original manuscript, rather than the Enkaku-ji version of the text, because access to the latter was refused. The Gunsho Ruijū version served as Tanaka Senshō’s teihon [底本] -- for a similar reason.

‡It is also possible (though somewhat less likely -- especially if we consider the collection of missing temae as constituting a unit) that another reason for its absence is because someone wanted a “souvenir” of the original, and surreptitiously tore it out of the Enkaku-ji manuscript (perhaps judging this arrangement -- since it was not sanctioned by the Senke -- to be irrelevant or superfluous).

It appears that the Tachibana family attempted to keep the manuscript in their keeping (which was the original copy that Jitsuzan had made with the Shū-un-an documents spread out before him) aligned with the Enkaku-ji version of the text. Thus, when kaki-ire were added to the Enkaku-ji manuscript, these were also transcribed into the family’s copy; and when, as here, a page was removed from the Enkaku-ji manuscript (for whatever reason), the corresponding page was also taken out of their copy.

Apparently not all of the curators of the other four copies were as diligent about following the same practice as was the Tachibana family. Thus at least some of these versions began to differ from the Enkaku-ji version over time -- and this was especially true of the contents of Book Five.

Naturally, when a page remained part of their version, the traditions connected with that arrangement continued to be handed down within the circle of scholars who gathered around that particular manuscript. And it was one of these people who, in his old age, finally imparted these teachings to Shibayama Fugen (perhaps when the final demise of the tradition was already rearing its head, as one generation of scholars began to die off, while their ranks were no longer being replenished, as Japan began to Westernize and modernize, and came to view these “ancient” traditions, more and more, with scorn and derision).

**According to the Enkaku-ji manuscript, the Tsune no bondai kazari [常盆・臺飾] (which was discussed in the previous post) is followed by an entry known as the Son-kyaku shoza no kazari nari [尊客初座之飾也], which, as the title suggests, is the way the daisu was arranged during the shoza when serving tea to an extremely exalted shōkyaku (though the goza arrangement is not found under that name in the present version of the Enkaku-ji manuscript).

In Tanaka Senshō’s commentary (which is based on the version of Jitsuzan’s original notes that were published in the Gunsho Ruijū), the Tsune no bondai kazari is followed by an arrangement named the Nagabon tsune no mitsu-kazari [長盆常ノ三ツ飾也], which is an arrangement where the dai-temmoku, chashaku (also tied in a shifuku), and chaire are arranged together on an “ordinary” nagabon (measuring 1-shaku 5-sun 2-bu by 1-shaku 4-bu). In this temae a chaire-bon is brought out for the chaire, and the temmoku and its dai are handled together on the nagabon. This is the “shin no shin” [眞之眞] temae of several of the modern schools, and in at least two of them it is considered to be their isshi sō-den [一子相傳], a knowledge of which is supposedly reserved to the iemoto alone. (Since it involves a chaire-bon, the temae can be dated no earlier than Jōō’s middle period, since Jōō was the creator of the chaire-bon; it was popularized by the machi-shū, and thus came to the hands of the Senke -- who, since they were ignorant of the actual gokushin temae, imagined this one to be “highest,” because it was the most complicated.)

††The organization of Book Five was apparently much more logical than it appears today -- when viewed in its entirety, with the missing temae restored to their original positions, the initial part of the book progresses from the basic arrangement, to the use of the bon-chaire and dai-temmoku, and then, through various permutations, arrives at the nagabon kazari, and so on to the gokushin futatsu-gumi temae and the san-shu gokushin temae (which was, historically speaking, the first temae publicly performed in Japan -- on the 18th day of the Sixth Month of the year corresponding to 1403).

Certain of the “missing” temae (and variants) are first documented in Katagiri Sekishū’s little known collection of treatises on the practice of the daisu, Ro-daisu no koto [爐臺子之㕝], Sō no shin・gyō・sō [草之眞・行・草], Gyō no Shin-daisu・gyō・sō [行之眞臺子・行・草], and Gokushin-daisu・ryō-kijin [極眞臺子・兩貴人] -- which he wrote as part of his study of Jōō’s chanoyu -- which predated the Nampō Roku by several decades. Perhaps it was for this reason -- to make the contents of this present collection appear wholly unprecedented -- that these temae were removed? This was all at the time, we must remember, when, while publicly making their secrets even more secret, the various schools were privately comparing notes, in an effort to establish their own lines of orthodoxy.

While I had originally intended to deal with these missing temae as an appendix to the book (in much the same way as I handled the missing gatherings that are found in the Rikyū hyakkai-ki [利休百會記] when translating Book Six of the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho [利休茶湯書]), on deeper reflection it seemed more logical (in light of the way that the series of temae build upward from the simpler forms to the gokushin temae) to restore them to their original places here; and so I will do.

¹Tsune no chaire・chashaku kazari [常茶入・茶杓飾.

This arrangement shows the way to display a chaire* that is accompanied by a chashaku that was made for it† by a mei-jin [名人]‡ of bygone days. The specific purpose of this arrangement is to draw attention to the chashaku.

Displaying the chashaku to the right of the chaire -- which, in the original configuration (where the guests are seated on the host’s left, and the katte is located on his right), is the higher seat -- indicates that the chashaku somewhat outranks the chaire. Thus the chaire is probably what we would consider an ordinary piece (rather than a meibutsu), and it is the fact that the chashaku was carved by someone important in the history of chanoyu that sanctions its being displayed in the higher place**.

A chashaku made by the host would never be displayed like this. ___________ *Because the chaire is not on a tray, and because it is not centered on its kane (let alone displayed as a mine-suri [峰摺り]), this indicates that it is a rather ordinary one.

†Traditionally, the chashaku was made to be used with a specific chaire (or, at least, with a chaire of a specific size -- a 1-sun 9-bu ko-tsubo, a medium-sized, 2-sun 2-bu, nasu, or a large, 2-sun 5-bu, katatsuki: all of these sizes were fairly standard, and most of the classical chaire fit into one of these categories).

In the early days this was because the chashaku had to be long enough to extend beyond the rim of the tray (during the temae), while still contacting the tray in line with the far edge of the foot (and with the bowl extending as far as the back side of the chaire). This is why, for example, the meibutsu ivory chashaku came in three different lengths.

‡A master. For example, Ashikaga Yoshimasa is said to have carved chashaku with his own hands. The same is true of Shukō.

**Possibly an ivory chashaku could be displayed like this, but only one that had been owned by a famous tea master of the past -- and preferably one that he had personally used with this chaire.

²Kono kazari no toki chawan ni te mo temmoku ni te mo hakobu nari [此飾ノ時茶碗ニテモ天目ニテモハコブナリ].

“When employing this arrangement, whether [the host] uses a[n ordinary] chawan, or a [dai-]temmoku, [the bowl] is carried out [from the katte].”

³Chashaku ni yoru-beshi [茶杓ニ依ルベシ].

“[Whether it is an ordinary chawan, or a dai-temmoku, that is carried out from the katte] depends on the chashaku.”