#Ἰησοῦs

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Съ Рождествомъ Христовымъ!

Рождество́ по пло́ти Господа Бога и Спаси́теля нашего Иисуса Христа

Ἡ κατὰ σάρκα Γέννησις τοῦ Κυρίου καὶ Θεοῦ καὶ Σωτῆρος ἡμῶν Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ

🕊🕊🕊✨✨✨😇😇😇🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 Corinthians 6:9–11

9 ἢ οὐκ οἴδατε ὅτι ἄδικοι θεοῦ βασιλείαν οὐ κληρονομήσουσιν; μὴ πλανᾶσθε· οὔτε πόρνοι οὔτε εἰδωλολάτραι οὔτε μοιχοὶ οὔτε μαλακοὶ οὔτε ἀρσενοκοῖται 10 οὔτε κλέπται οὔτε πλεονέκται, οὐ μέθυσοι, οὐ λοίδοροι, οὐχ ἅρπαγες βασιλείαν θεοῦ κληρονομήσουσιν. 11 καὶ ταῦτά τινες ἦτε· ἀλλʼ ἀπελούσασθε, ἀλλʼ ἡγιάσθητε, ἀλλʼ ἐδικαιώθητε ἐν τῷ ὀνόματι τοῦ κυρίου Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ καὶ ἐν τῷ πνεύματι τοῦ θεοῦ ἡμῶν.

My translation:

9 Or do you not know that unrighteous ones will not inherit the kingdom of God? Be not led astray; neither fornicators nor idolaters nor adulterers nor soft ones nor males lying with one another 10 nor thieves nor greedy ones, not drunkards, not slanderers, not ravenous ones will inherit the kingdom of God. 11 And these things some of you were; but you were washed, but you were made holy, but you were declared righteous in the name of the lord Yeshua the Anointed and in the breath of our God.

Notes:

6:9–10

ὅτι introduces indirect discourse after a verb of cognition, the negated perfect οὐκ οἴδατε (from οἶδα; perf. form with pres. sense).

κληρονομέω (18x) is, “I inherit”, from ἡ κληρονομία (14x) “inheritance” (cf. ὁ κληρονόμος, 15x, “heir”), itself from ὁ κλῆρος (11x) “lot” (used in deciding) + νέμω “I assign” (not in NT). The substantival adjective ἄδικοι (“unjust, unrighteous”; see note on v. 1; NIV: “wrongdoers”) is the direct object of the negated future οὐ κληρονομήσουσιν. θεοῦ is a descriptive genitive modifying βασιλείαν which is the direct object of the verb.

The negated present imperative μὴ πλανᾶσθε (from πλανάω “I mislead, deceive”) denotes a prohibition to an action already in progress.

The οὔτε ... οὔτε ... οὔτε construction is, “Neither ... nor ... nor ...”

ὁ μοιχός (3x) is “adulterer”, from μοιχεύω (15x) “I commit adultery” (cf. ἡ μοιχεία, 3x, “adultery”).

The adjective μαλακός (4x) is, “soft” (so in the gospels) from ἡ μαλακία (3x) “softness” (in the sense of “infirmity”). Here it is figurative and means, “effeminate” (BDAG), referring to the passive male partner in a homosexual act.

ὁ ἀρσενοκοίτης (2x) is, “a homosexual person”, from ἄρσην (9x) “male” + ἡ κοίτη (4x) “a bed, lying down” (note the two root words are found in in the LXX of Lev. 18:22, 20:13, et al). The term refers to the active male partner in a homosexual act.

ὁ κλέπτης (16x) is, “thief”, from κλέπτω (13x), “I steal”.

The series of plural substantives form a compound subject of the main verb κληρονομήσουσιν in verse 10: πόρνοι (“a sexually immoral person”; see note on 5:9), εἰδωλολάτραι (“idolater”; see note on 5:10), μοιχοὶ, μαλακοὶ, ἀρσενοκοῖται, κλέπται, πλεονέκται (“covetous”; see note on 5:11).

Here the construction changes (“neither ... nor ... nor ... not ... not ...”) adding to the compound subject of κληρονομήσουσιν: μέθυσοι (“drunkard”; see note on 5:11), λοίδοροι (“reviler, slanderer”; see note on 5:11), ἅρπαγες (“swinder”; see note on 5:10). The ten substantives form the subject of the future κληρονομήσουσιν (from κληρονομέω “I inherit”; see note on v. 9). βασιλείαν, modified by descriptive genitive θεοῦ, is the direct object of the verb. ‘All of them are in apposition to ἄδικοι, an apposition which would seem quite natural to Greeks, who were accustomed to regard δικαιοσύνη as the sum-total of virtues, and therefore ἀδικία as the sum-total of vices’ (ICC). Paul ‘is not describing the qualifications required for an entrance examination; he is comparing habituated actions, which by definition can find no place in God’s reign for the welfare of all, with those qualities in accordance with which Christian believers need to be transformed if they belong authentically to God’s new creation in Christ’ (NIGTC).

6:11

The substantival near-demonstrative pronoun ταῦτά, referring to the ten substantives in verses 9–10, is the predicate nominative of the imperfect ἦτε (from εἰμί) and the indefinite pronoun τινες is the subject. With the second-person verb, τινες is translated, “some of you”.

ἀπολούω (2x) is, “I wash away”, from ἁπό + λούω (5x) “I wash”. The preposition “away” does not translate into English in the passive, so, “I wash”. ἀπελούσασθε is an aorist middle, thus “you washed away [your sins]”, not “you were washed” as most translations read.

ἀπελούσασθε and aorist passives ἡγιάσθητε (from ἁγιάζω “I make holy”) & ἐδικαιώθητε (from δικαιόω “I justify”) are each preceeded by ἀλλά for emphasis, showing that the Corinthians are no longer marked by the behaviors that the pagans are. CGT takes ἡγιάσθητε to mean, “dedicated to a holy life.” BDAG says, ‘In the context of 1 Cor 6:11 ἐδικαιώθητε means you have become pure.’ Most translations: “But you were washed, you were sanctified, you were justified.”

The preposition ἐν (twice) modifies all three above verbs instrumentally. ἐν τῷ ὀνόματι τοῦ κυρίου Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ (“in the name of the lord Jesus Christ”) has to do with an appeal to authority. καὶ ἐν τῷ πνεύματι τοῦ θεοῦ ἡμῶν (“and in the Spirit of our God”) expands the agency of the three verbs.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

ΠΡΟΣ ΓΑΛΑΤΑΣ 3.26-27 πάντες γὰρ υἱοὶ θεοῦ ἐστὲ διὰ τῆς πίστεως ἐν Χριστῷ Ἰησοῦ: ὅσοι γὰρ εἰς Χριστὸν ἐβαπτίσθητε, Χριστὸν ἐνεδύσασθε.

26 You are all sons of God through faith in Christ Jesus. 27 For all of you who were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. — Galatians 3:26-27 | Novum Testamentum Graece (Tischendorf) and Berean Study Bible (BSB) Novum Testamentum Graece (Tischendorf’s eighth edition Greek New Testament with accents/diacritics) © 2003 Faithlife and The Berean Study Bible (BSB) © 2016, 2018 by Bible Hub and Berean Bible. All rights Reserved. Cross References: Deuteronomy 14:1; John 1:7; John 1:12; Romans 6:3; Romans 8:1; Romans 8:14; Romans 8:16; Romans 8:19; Romans 13:14; 1 Corinthians 10:2; 2 Corinthians 1:1; Matthew 28:9

#God#adoption#children#Jesus Christ#faith#baptism#Galatians 3:26-27#The Epistle of Galatians#New Testament#Novum Testamentum Graece#Tischendorf#BSB#Berean Study Bible#Bible Hub#Berean Bible

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Poetics of Fragmentation in the Athyr Poem of C. P. Cavafy

Gregory Nagy

[Originally published in Imagination and Logos: Essays on C. P. Cavafy (ed. Panagiotis Roilos) 265-272. Cambridge, MA 2010. The original pagination of the article will be indicated in this electronic version by way of curly brackets (“{“ and “}”). For example, “{265|266}” indicates where p. 265 of the printed article ends and p. 266 begins.]

Ἐν τῷ μη[νὶ] Ἀθύρ

[[1]] Μὲ δυσκολία διαβάζω στὴν πέτρα τὴν ἀρχαία. [[2]] <<Κύ[ρι]ε Ἰησοῦ Χριστέ>>. Ἕνα <<Ψυ[χ]ὴν>> διακρίνω. [[3]] <<Ἐν τῷ μη[νὶ] Ἀθὺρ>> <<ὁ Λεύκιο[ς] ἐ[κοιμ]ήθη>>. [[4]] Στὴ μνεία τῆς ἡλικίας <<Ἐβί[ωσ]εν ἐτῶν>>, [[5]] τὸ Κάππα Ζῆτα δείχνει ποὺ νέος ἐκοιμήθη. [[6]] Μὲς στὰ φθαρμένα βλέπω <<Αὐτὸ[ν] … Ἀλεξανδρέα>>. [[7]] Μετὰ ἔχει τρεῖς γραμμὲς πολὺ ἀκρωτηριασμένες· [[8]] μὰ κάτι λέξεις βγάζω – σὰν <<δ[ά]κρυα ἡμῶν>>, <<ὀδύνην>>, [[9]] κατόπιν πάλι <<δάκρυα>>, καὶ <<[ἡμ]ῖν τοῖς [φ]ίλοις πένθος>>. [[10]] Μὲ φαίνεται ποὺ ὁ Λεύκιος μεγάλως θ’ ἀγαπήθη. [[11]] Ἐν τῷ μηνὶ Ἀθὺρ ὁ Λεύκιος ἐκοιμήθη.

It is hard to read . . . . on the ancient stone. “Lord Jesus Christ” . . . . I make out the word “Soul”. “In the month of Athyr . . . . Lucius fell asleep.” His age is mentioned . . . . “He lived years . . . .”? The letters KZ show . . . . that he fell asleep young. In the damaged part I see the words . . . . “Him . . Alexandrian.” Then come three lines . . . . much mutilated. But I can read a few words . . . . perhaps “our tears” and “sorrows.” And again: “Tears” . . . . and: “for us his friend mourning.” I think Lucius . . . . was much beloved. In the month of Athyr . . . . Lucius fell asleep . . . .

Translated by George Valassopoulo in E.M. Forster, Pharos and Pharillon, Hogarth Press, 1923 from C. P. Cavafy, Poems 1916-18 as published on the Official Website of the Cavafy Archive, http://www.cavafy.com/

My contribution, however slight, to an understanding of this difficult poem starts with an alternative translation of my own, followed by an exegesis. My translation has no literary merit: it is simply a working translation, keyed to the exegesis that follows it. In order to facilitate the reading of the exegesis, I have numbered, within double-square brackets ([[ ]]), the lines of the translation to match the verses of Cavafy as printed in their original format. As we will see, even the formatting of this poem is part of its meaning. Here, then, is my translation of the poem—and of its formatting:

[[1]] “With difficulty, I am reading … what is on the ancient stone. [[2]] It starts <<Lord Jesus Christ …>> Then there is another word, <<psyche>>, I can make out that much. [[3]] <<In the month Athyr …>> <<… Lucius went to sleep>>. [[4]] In remembrance of his age … <<He lived for such-and-such number of years>> [[5]] —the letters <<Kappa>> and <<Zeta>>, for twenty and seven, show … that he was a youth when he went to sleep. {265|266} [[6]] Right in the middle of the damaged parts, I see <<… himself … the Alexandrian>>. [[7]] Then there are three lines that are … very much dismembered, [[8]] but I can somehow make out some words … like, <<our tears>>, <<pain>>, [[9]] then once again <<tears>>, … and, <<for us his friends, sorrow>>. [[10]] It seems to me that Lucius … would have been very much loved. [[11]] In the month Athyr … Lucius went to sleep.”

What follows is my exegesis, pursued line by line. In this exegesis, double quotation marks enclose wording xxx spoken by the poet who is reading an inscription in his poem: so, “xxx”. Double angular brackets enclose wording pictured as seen by the poet in the act of reading the inscription: so, <<xxx>>. And single quotation marks enclose wording that I use to translate Greek wording that falls outside the poem: so, ‘xxx’.

I start with the first comma, “,” at line [[1]] of my translation of the poem. With the placement of this comma “,” I mean to convey a double meaning inherent in the poem. That is, there are two levels of difficulty in this poem. One, it is difficult to read the fragmentary inscription engraved into stone. And two, it is difficult to read the poem. Not only is the fragmentary inscription difficult to read; even the act of reading the poem is difficult in the first place. For us as readers, it is as difficult to read the fragmentary poem as it is difficult for the poet to read the fragmentary inscription. That is because the reader of the fragmentary inscription, who is the poet of the poem that pictures the inscription, is implying that all poems are fragmentary inscriptions. Even more, the poet is implying that any act of reading anything is difficult: “With difficulty, I am reading.”

At line [[2]], the first three words of the fragmentary inscription seem at first to be easy enough to read. <<Κύ[ρι]ε Ἰησοῦ Χριστέ>> or <<Lord Jesus Christ>>… So far, so good. Maybe the reading will not be so difficult after all. Some letters have broken off, yes, but they can be restored without too much difficulty by the reader poet, who is following here the convention of experts in the heuristic science of epigraphy, making restorations of missing letters xxx by enclosing the letters of their restoration within square brackets: so, [xxx].

But now the real difficulties begin. Now the reader poet is starting to have a difficult time reading the next word at line [[2]], as the inscription becomes more and more fragmented. The reader thinks he can still make out the word <<Ψυ[χ]ήν>>, which translators tend to render as <<Soul>>, but the letter <<χ>>, which is also the first letter of <<Χ>>ριστός or <<Ch>>rist, has broken off, and it can only be restored within square brackets, just as experts in epigraphy restore missing letters within square brackets. Now, on second thought, the {266|267} reader is made more aware that the <<Lord>> of <<Lord Jesus Christ>> as read earlier at line [[2]] is also fragmented. There the missing letters are <<ρι>> in <<Κύ[ρι]ε>>, but those missing letters had been easily restored, also within square brackets, by the reader poet reading as an expert in epigraphy.

There is more to be said about the word <<Ψυ[χ]ήν>> as read by the reader poet at line [[2]]. This word, which is conventionally rendered as <<Soul>>, has been left untranslated in my working translation, where I give simply <<psyche>>. I do so because the translation ‘soul’ for ψυχή works only if the Christian sense of ψυχή is meant. But what if a pre-Christian sense is also meant here? In the Greek of Homeric diction, for example, ψυχή can refer either to the breath of life, when someone is alive, or to a disembodied simulacrum of identity after death, when someone is dead. And, by contrast with ψυχή, the word αὐτός in Homeric diction means not only ‘self’ when someone is alive but also ‘body’ when someone is dead. We see such a contrast between the words ψυχή and αὐτός at the very beginning of the Iliad:

Μῆνιν ἄειδε θεὰ Πηληϊάδεω Ἀχιλῆος οὐλομένην, ἣ μυρί’ Ἀχαιοῖς ἄλγε’ ἔθηκε, πολλὰς δ’ ἰφθίμους ψυχὰς Ἄϊδι προΐαψεν ἡρώων, αὐτοὺς δὲ ἑλώρια τεῦχε κύνεσσιν οἰωνοῖσί τε πᾶσι, Διὸς δ’ ἐτελείετο βουλή

Anger, sing it, goddess! The anger of the son of Peleus, Achilles, the baneful anger that caused countless pains for the Achaeans and hurled to Hades many powerful psychai of heroes, but they themselves [autoi, = their bodies] were made prizes for dogs and for all kinds of birds. And the will of Zeus was being accomplished.

Iliad I 1-5

The Homeric body, as expressed by αὐτός or ‘self’, is still the self even after death, while the Homeric ψυχή after death is no longer the self but merely a disembodied simulacrum of the self. It is the ψυχαί or disembodied simulacra of the self who are being hurled down to Hades, not their bodies, who are the ‘selves’ themselves, the αὐτοί.

So then the question is, does the <<Αὐτόν>> or <<himself>> in the accusative case, as we read this word later on at line [[6]] in the poem of Cavafy, refer to the <<Alexandrian>> at the same line [[6]] in the Christian sense of the ‘self’ as a ψυχή that transcends death—or to the ‘self’ in the Homeric sense of a body left {267|268} behind by the ψυχή after death? At line [[2]] of the poem by Cavafy, the word <<Ψυχήν>> is also in the accusative case, just as the <<Αὐτόν>> or <<himself>> is in the accusative case at line [[6]]. Something is happening to the psyche, is being done to the psyche—whether this psyche is a Christian or a pre-Christian ψυχή.

At line [[3]], the reading continues, but we do not find out what happened to the psyche. All we can find out so far is that whatever did happen happened <<in the month of Athyr>>. That is what the inscription says in the first part of the line. In the second part, which is separated from the first part by a break in the line, the inscription goes on to say that a young man <<went to sleep>>, and we learn that his name was <<Lucius>>>. I translate the break between the first part and the second part of the line not with three dots marking ellipsis but with two sets of three dots marking two separate ellipses. That is because the break comes in the middle of a quotation, and there is no way of knowing whether the missing words are part of one syntactical sequence or of two.

The fragmentary inscription, as imagined at line [[3]], does not say outright that the young man <<went to sleep>>, since the root of the verb that I translate as <<went to sleep>>, <<κοιμ->>, is imagined as a learned epigraphical restoration. In the inscription, the root <<κοιμ->> has broken away and has to be restored within square brackets: <<ὁ Λεύκιο[ς] ἐ[κοιμ]ήθη>>, which can be approximated as <<Lucius [went to sleep]>>. The experience of going to sleep is epigraphically conjectured, without being poetically realized. At line [[5]] and then again at line [[11]], by contrast, the epigraphical conjecture will become a poetic reality. In those two lines, [[5]] and [[11]], the experience of going to sleep is a reality created by the poetry, no longer a conjecture derived from the heuristic science of epigraphy.

At line [[4]], the remembrance of the age of the young man Lucius anticipates a certainty—that the number of years he lived is known to the reader poet—who anticipates what is already known by the writer of the inscription. But the number is missing in this line, where the reader would expect to read it. That is why I translate here at line [[4]] the missing number by using the words <<such-and-such>>. What line [[4]] says is that <<He lived for such-and-such number of years>>. Line [[5]], which comes next, will fill in, adding the numbers that are expected but not yet found at line [[4]]. The <<such-and-such>> number of years at line [[4] can finally be filled in with real numbers at line [[5]], but only because the reader can now make out the <<Kappa>> and the <<Zeta>>, Greek letters reused for the Attic numerals <<20>> and <<7>>, in this case showing <<27>> as the age of the young man Lucius when <<he went to sleep>>.

At line [[5]], my working translation starts with a dash, and the first letter of the line is not capitalized. These details in formatting are meant to show that the previous line [[4]] did not end in a full sentence. The present line [[5]] {268|269}continues where the previous line [[4]] had left off. Meanwhile, the reading in the inscription that had to be restored as <<went to sleep>> at line [[3]] is now the reading in the poem as written by the poet and as read by the reader of the poem at line [[5]].

In the lines that follow, both in the lines of the inscription and in the lines of the poem, the fragmentation is so severe that the reader of the inscription and the reader of the poem can barely make out any readable words. All there is to read in the inscription is what the speaking reader actually sees, as signaled by “βλέπω” or “I see” at line [[6]]. If we take this word “βλέπω” in a sublime Platonic sense, not in the everyday sense of ‘βλέπω’ as ‘I see’ in everyday modern Greek, then what the “I” actually “sees” is an absolute Form, in that Plato’s use of βλέπω focuses on the seeing of Forms in Plato’s Theory of Forms. But the question is, what Form does the reader poet see “in the middle of the damaged parts”? And the answer is, he sees what he reads, which is <<… himself … the one from Alexandria>>. That <<himself>>, conveyed by <<Αὐτό[ν]>> in the accusative case at line [[6]], could be not only Lucius, the young man from Alexandria. It could be Cavafy himself from Alexandria. Or, as I noted some moments ago, the <<himself>> could be the Homeric body, which is temporarily the ‘self’ as distinct from the ψυχή after death. Or again, in a Christian sense, it could be the ‘self’ as permanently reunited with the ψυχή after death.

Or, yet again, in an ancient Egyptian sense that is most appropriate to Alexandria in Egypt, the <<self>> conveyed by the <<Αὐτό[ν]>> in the accusative case at line [[6]] could be the body of Osiris. In Egyptian myth, the god Osiris was the first person to die and then be resurrected after death. He had gone to sleep while sealed within a larnax or ‘chest’—and his body was then dismembered and scattered by Seth, lord of chaos, only to be reassembled and restored to life by the goddess Isis, loving consort of Osiris, in the month of Athyr. The ancient Egyptian myth about the fragmentation of Osiris and about his subsequent restoration by his consort Isis in the month of Athyr has been retold in the learned essay of Plutarch, On Isis and Osiris. The form of the myth as known to Plutarch was doubtless well known to Cavafy. Here is my paraphrase of the Egyptian myth as retold in the Isis and Osiris of Plutarch:

356B. It all happened on the 17th day of the month Athyr. The occasion for the death of Osiris is a sumposion ‘symposium’ attended by the god and 72 symposiasts who conspire to trick Osiris into lying down into a larnax ‘chest’ that fits him perfectly—and him only. Once Osiris takes his place inside the perfect fit of the larnax, the conspirators seal it and cast it into the Nile. With reference to the sacred number 72, we may compare the number of assembled men in the narrative about the genesis of the Septuagint. {269|270}

357A. The larnax containing Osiris floats down the Nile and into the sea, floating onward all the way to the Phoenician seacoast city of Byblos, a place that becomes the namesake for ‘papyrus’ and ‘book’ and, ultimately, ‘bible’ as represented by the Septuagint. Isis ultimately brings back the body from Phoenicia to Egypt.

357D. In Egyptian ritual, Plutarch says, the eid��lon ‘image’ of any dead person, when it is ritually carried around in a kibōtion ‘box’, is not just some ‘reminiscence’ [hupomnēma] of the ‘sacred experience’ (pathos) concerning Osiris. The ritual act of carrying around such an eidōlon is in the specific context of a sumposion ‘symposium’.

357E. The mythical honorand of the ritual symposium, Maneros, is envisioned as the inventor of ‘the craft of the Muses’ [mousikē].

357F-358A. Seth finds the sōma ‘body’ of Osiris in the moonlight and ‘dismembers’ (dieleîn) it.

358A. Then Isis looks for the parts of the sōma in a papyrus boat. The narrative adds an aetiology: how papyrus boats are immune from attacks by crocodiles. It is implied that Isis is reassembling the parts of the body of Osiris in order to reintegrate it for his eschatological resurrection.

358A. There is a different taphos ‘tomb’ of Osiris for each different ‘part’ [meros] of Osiris in different places throughout Egypt because Isis performed a separate taphē ‘entombment’ for each. Another version has it that she made eidōla ‘images’ for each polis in which Osiris is entombed.

The dismemberment of the body of Osiris is matched by the dismemberment of the poem of Cavafy, which is pictured as the reading of a dismembered inscription. The fragmented members of the poem need to be reassembled by the reader poet just as the fragmented members of the body of Osiris need to be reassembled by Isis. Just as the task of reassembling the fragmented body of Osiris is the key to the eschatological restoration and resurrection of Osiris, so also the task of reassembling the fragmented body of the poem is the key to restoring this poem and bringing it back to life.

But the task is difficult for the reader, perhaps so difficult as to be impossible. That is because the missing parts of the body of the poem, which match the missing parts of the inscription that is read by the reader poet, may perhaps never be found, may perhaps never be reunited with the parts that remain. And so the remains of the body of the poem may perhaps never be brought back to life. Unlike the goddess Isis, whose quest is to reassemble and restore all the missing parts of the body of Osiris, the reader of the poem may have to give up any hope, settling for something that falls far short of restoring the whole poem. The reader may have to settle for the fragmentation that remains. {270|271}

But the reader poet persists. He continues to read the inscription, as if to sustain a hope of restoring it and bringing it back to life simply by continuing to read. The reader continues to restore missing fragments within the square brackets that mark what is missing. The remains of the body of the poem call for the restoration of the fragments that are missing.

But now the reading becomes even more fragmentary, even more difficult. In the three lines that follow line [[6]], the fragments that remain are too disjointed to be read in continuity. Here the dismemberment of the body of the poem becomes decisive. It happens immediately after the <<self>> is signaled at line [[6]]. The next line [[7] signals that the reader of the fragmentary inscription is about to read “three lines that are … very much dismembered.” These “three lines” in the inscription will now be reenacted in the fragmentary wording and syntax of the next three lines in the poem, [[8]] and [[9]] and [[10]].

At lines [[8]] and [[9]], the reader reads words that break apart from each other, such as <<our tears>> and <<pain>> at line [[8]] and <<tears>> and <<for us his friends, sorrow>> at line [[9]]. The words at lines [[8]] and [[9]] are separated from each other by the breaks in the inscription. They are no longer connected to each other organically. And the two lines [[8]] and [[9]] are disjointed even as lines, since line [[8]] does not close in a full sentence but is picked up by the disjointed additions that follow. That is why the tears cannot end at [[8]] but need to start all over again at [[9]].

Then, at line [[10]], even the poem breaks apart, breaks up, disintegrates. This time, it is not the wording of the inscription that disintegrates. Rather, the disintegration happens in the wording of the poem itself. The wording at line [[10]] has taken over from the wording of the fragmented inscription. The wording of the poem here at line [[10]] is meant to tell what the fragments cannot tell fully, but now even the wording of the poem becomes fragmented. It is not that the fragmentation is caused at line [[10]] by breaks in the inscription. It is caused by breaks in the structure of the poem, in the body of the poem. The syntax of “It seems to me that Lucius … would have been very much loved” shows that the poetry is becoming fragmented, just as the inscription is already fragmented. The line is not a complete sentence, since something is syntactically missing in the ellipsis (…) that separates the two parts of the line.

Then, at the end, at line [[11]], the fragmented words of the poem as expressed in the previous line [[10]] are replaced by the restored words of the inscription. There are no more square brackets to indicate the missing letters of the inscription. Now “Lucius went to sleep” for sure, “ὁ Λεύκιος ἐκοιμήθη,” and these words are no longer quotations from the inscription, enclosed in double angular brackets and showing the epigraphical restorations, as they had been before at line [[3]], <<ὁ Λεύκιο[ς] ἐ[κοιμ]ήθη>>, which I had translated {271|272} as <<… Lucius went to sleep>>. This time, at line [[11]], the words “ὁ Λεύκιος ἐκοιμήθη” or “Lucius went to sleep” are not the words spoken by the inscription but the words spoken by the reader poet. But these words too, like the words of the inscription, are fragmentary, as we see from the spacing between the first and the second part of the line.

What ultimately reintegrates the disintegrating poem as it draws to a close is the love expressed for Lucius at line [[10]]: “μεγάλως θ’ ἀγαπήθη” – “[he] would have been very much loved.” In the logic of the inscription, this love was experienced by the original readers of the inscription—and by its original composer. But now we see it experienced all over again by the composer of the poem that frames the inscription. This composer becomes the first reader of this poem by virtue of being the last reader of the fragmentary inscription that he sees being framed within his poem. And just as the ultimate reintegration of Osiris after his disintegration is driven by the love of Isis in the ancient Egyptian myth, now the ultimate reintegration of the poem after its own disintegration is being driven by love—a love restored in the act of reading a fragmented inscription. Such is the integrating power, paradoxically, of Cavafy’s poetics of fragmentation."

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bible Attributes the Hidden Name of God to Greece

Eli kittim

The Greek New Testament Unlocks the Meaning of God’s Name

The meaning of God’s name (YHVH) was originally incoherent and indecipherable until the appearance of the Greek New Testament. In Isaiah 46:11, God says that he will call the Messiah “from a distant country” (cf. Matt. 28:18; 1 Cor. 15:24-25). Similarly, in Matt. 21:43, Jesus promised that the kingdom of God will be taken away from the Jews and given to another nation. That’s why Isaiah 61:9 says that the Gentiles will be the blessed posterity of God (through the messianic seed). Paul also says categorically and unequivocally, “It is not the children of the flesh [the Jews] … but the children of the promise [who] are regarded as descendants [of Israel]” (Rom. 9:6-8).

These passages demonstrate why the New Testament was not written in Hebrew but in Greek. In fact, most of the New Testament books were composed in Greece. The New Testament was written exclusively in Greek, and most of the epistles address Greek communities. Not to mention that the New Testament authors used the Greek Old Testament as their Inspired text and copied extensively from it. That’s also why Christ attributed the divine I AM to the Greek language (alpha and omega). Now why did all this happen? Was it a mere coincidence or an accident, or is it because God’s name is somehow associated with Greece? Let’s explore this question further.

YHVH (I AM)

Initially, God did not disclose the meaning of his name to Moses (Exod. 3:14), but only the status of his ontological being: “I Am.” The four-letter Hebrew theonym יהוה (transliterated as YHVH) is the name of God in the Hebrew Bible, and it’s pronounced as yahva. In Judaism, this name is forbidden from being vocalized or even pronounced.

Hebrew was a consonantal language. Vowels and cantillation marks were devised much later by the Masoretes between the 7th and 10th centuries AD. Thus, to call the divine name Yahva is a rough approximation. We really don’t know how to properly pronounce the name or what it actually means. But, through linguistic and biblical research, we can propose a scholarly hypothesis.

God Explicitly Identifies Himself with the Language of the Greeks

Since God’s name (the divine “I AM”) was revealed in the New Testament vis-à-vis the first and last letters of the Greek writing system (“I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end” Rev. 22:13), then it necessarily must reflect a Greek name. The letters Alpha and Omega constitute “the beginning and the end” of the Greek alphabet. Put differently, the creator of the universe (Heb. 1:2) explicitly identifies himself with the language of the Greeks! That explains why the New Testament was written in Greek rather than Hebrew. That’s also why we are told “how God First concerned Himself about taking from among the Gentiles a people for his name” (Acts 15:14):

“And with this the words of the Prophets agree, just as it is written, … ‘THE GENTILES WHO ARE CALLED BY MY NAME’ “ (Acts 15:15-17).

This is a groundbreaking statement because it demonstrates that God’s name is not derived from Hebraic but rather Gentile sources. The Hebrew Bible asserts the exact same thing:

“All the Gentiles… are called by My name” (Amos 9:12).

The New Testament clearly tells us that God identifies himself with the language of the Greeks: “ ‘I am the Alpha and the Omega,’ says the Lord God” (Rev. 1:8). In the following verse, John is “on the [Greek] island called Patmos BECAUSE of the word of God and the testimony of Jesus” (Rev. 1:9 italics mine). We thus begin to realize why the New Testament was written exclusively in Greek, namely, to reflect the Greek God: τοῦ μεγάλου θεοῦ καὶ σωτῆρος ἡμῶν ⸂Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ⸃ (Titus 2:13)! Incidentally, God is never once called Yahva in the Greek New Testament. Rather, he is called Lord (kurios). Similarly, Jesus is never once called Yeshua. He is called Ἰησοῦς, a name which both Cyril of Jerusalem (catechetical lectures 10.13) and Clement of Alexandria (Paedagogus, Book 3) considered to be derived from Greek sources.

Yahva: Semantic and Phonetic Implications

If my hypothesis is accurate, we must find evidence of a Greek linguistic element within the Hebrew name of God (i.e. Yahva) as it was originally revealed to Moses in Exod. 3:14. Indeed, we do! In the Hebrew language, the term “Yahvan” represents the Greeks (Josephus Antiquities I, 6). Therefore, it is not difficult to see how the phonetic and grammatical mystery of the Tetragrammaton (YHVH, commonly pronounced as Yahva) is related to the Hebrew term Yahvan, which refers to the Greeks. In fact, the Hebrew names for both God and Greece (Yahva/Yahvan) are virtually indistinguishable from one another, both grammatically and phonetically! The only difference is in the Nun Sophit (Final Nun), which stands for "Son of" (Hebrew ben). Thus, the Tetragrammaton plus the Final Nun (Yahva + n) can be interpreted as “Son of God.” This would explain why strict injunctions were given that the theonym must remain untranslatable under the consonantal name of God (YV). The Divine Name can only be deciphered with the addition of vowels, which not only point to “YahVan,” the Hebrew name for Greece, but also anticipate the arrival of the Greek New Testament!

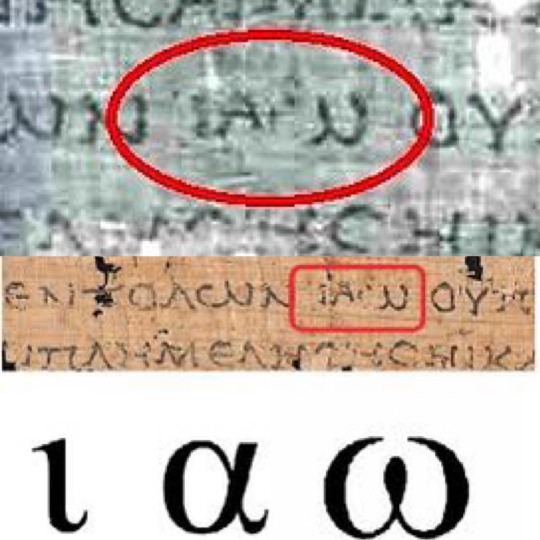

There’s further evidence for a connection between the Greek and Hebrew names of God in the Dead Sea Scrolls. In a few Septuagint manuscripts, the Tetragrammaton (YHVH) is actually translated in Greek as ΙΑΩ “IAO” (aka Greek Trigrammaton). In other words, the theonym Yahva is translated into Koine Greek as Ιαω (see Lev. 4:27 LXX manuscript 4Q120). This fragment is dated to the 1st century BC. Astoundingly, the name ΙΑΩΝ is the name of Greece (aka Ἰάων/Ionians/IAONIANS), the earliest literary records of whom can be found in the works of Homer (Gk. Ἰάονες; iāones) and also in the writings of the Greek poet Hesiod (Gk. Ἰάων; iāōn). Bible scholars concur that the Hebrew name Yahvan represents the Iaonians; that is to say, Yahvan is Ion (aka Ionia, meaning “Greece”).

We find further evidence that the Tetragrammaton (YHVH) is translated as ΙΑΩ (IAO) in the writings of the church fathers. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia (1910) and B.D. Eerdmans, Diodorus Siculus refers to the name of God by writing Ἰαῶ (Iao). Irenaeus reports that the Valentinians use Ἰαῶ (Iao). Origen of Alexandria also employs Ἰαώ (Iao). Theodoret of Cyrus writes Ἰαώ (Iao) as well to refer to the name of God.

Summary

Therefore, the hidden name of God in the Septuagint, the New Testament, and the Hebrew Bible seemingly represents Greece! The ultimate revelation of God’s name is disclosed in the Greek New Testament by Jesus Christ who identifies himself with the language of the Greeks: Ἐγώ εἰμι τὸ Ἄλφα καὶ τὸ Ὦ (Rev. 1:8). In retrospect, we can trace this Greek name back to the Divine “I am” in Exodus 3:14!

#ΌνομαΘεού#יהוה#exodus3v14#Theonym#onomastics#thelittlebookofrevelation#Yahvan#i am#alpha and omega#javan#Yavan#GentileGod#ΙΑΩ#τομικροβιβλιοτηςαποκαλυψης#Yahva#ΙΑΩΝ#GreekGod#ελικιτιμ#orthonym#Elikittim#4Q120#church fathers#Homer#hesiod#dead sea scrolls#hebrew bible#new testament#koine greek#name of god#bible study

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Οὐκ ἔνι Ἰουδαῖος οὐδὲ Ἕλλην, οὐκ ἔνι δοῦλος οὐδὲ ἐλεύθερος, οὐκ ἔνι ἄρσεν καὶ θῆλυ· πάντες γὰρ ὑμεῖς εἷς ἐστὲ ἐν χριστῷ Ἰησοῦ.

0 notes

Text

Γέροντα πῶς πρέπει νὰ λέω τὴν εὐχή;

Γέροντα πῶς πρέπει νὰ λέω τὴν εὐχή; -Θὰ σκέφτεσαι παιδὶ μου ὅτι εἶσαι στὸ λιμάνι καὶ ὅτι ἐκείνη τὴ στιγμὴ ἔχει φύγει ἕνα πλοῖο, πού μέσα του εἶναι ὁ Χριστὸς καὶ ὅλη ἡ Ἐκκλησία. Τι θὰ κάνεις; δὲν θὰ φωνάξεις μὲ ὅλη σου τὴ δύναμη “Κύριε Ἰησοῦ Χριστὲ ἐλέησον μέ”; Ἔτσι πρέπει νὰ προσευχόμαστε μὲ τέτοια δύναμη ψυχῆς. Ὅσιος Εφραὶμ Κατουνακιώτης

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

JESUS, JOSHUA or YESHUA.

The Biblical name of the Messiah from the original Hebrew and Aramaic is spelled as ישוע and transliterates into English as Yeshua.

The letter “J” did not come into popular use in the English language until after the 1611 King James Bible was printed.

Early translations lost the original sound of the name by adding an “s” in the Greek language to masculinize the name, which continued into Latin:

Hebrew/Aramaic - ישוע

Greek - Ἰησοῦς, Ἰησοῦν, Ἰησοῦ.

Latin – Iesus, Iēsum, Iēsū.

Italian – Gesù.

Middle English – Ihesus, Iesu, or Iesus.

Modern English – Jesus.

Rather than transliterating through a number of languages, over 2,000 years, let’s go back to the original source, and transliterate straight to modern-day English, then we will have the true name of Christ Yeshua.

You may have heard modern-day false teachers say that His name was Jesus or some other non-Biblical variant of Joshua, but they are liars and deceivers. Yeshua has the Hebrew meaning "He will save" while the name Joshua means "God will save".

0 notes

Text

Ευαγγέλιο & Απόστολος της Κυριακής 28 Ιουλίου 2024 - E´ΜΑΤΘΑΙΟΥ Το Ευαγγέλιο σήμερα Κυριακή E´ΜΑΤΘΑΙΟΥ, 28 Ιουλίου 2024 ΚΑΤΑ ΜΑΤΘΑΙΟΝ Η´ 28 - 34 28 Καὶ ἐλθόντι αὐτῷ εἰς τὸ πέραν εἰς τὴν χώραν τῶν Γεργεσηνῶν ὑπήντησαν αὐτῷ δύο δαιμονιζόμενοι ἐκ τῶν μνημείων ἐξερχόμενοι, χαλεποὶ λίαν, ὥστε μὴ ἰσχύειν τινὰ παρελθεῖν διὰ τῆς ὁδοῦ ἐκείνης. 29 καὶ ἰδοὺ ἔκραξαν λέγοντες· Τί ἡμῖν καὶ σοί, Ἰησοῦ υἱὲ τοῦ Θεοῦ; ἦλθες ὧδε πρὸ καιροῦ βασανίσαι ἡμᾶς; 30 ἦν δὲ μακρὰν ἀπ’ αὐτῶν ἀγέλη χοίρων πολλῶν βοσκομένη. 31 οἱ δὲ δαίμονες παρεκάλουν αὐτὸν λέγοντες· Εἰ ἐκβ... περισσότερα στο link https://orthodoxia.online/evaggelia/evangelio-apostolos-tis-kyriakis-28-iouliou-2024-ematthaiou/

0 notes

Text

John 12:3–5

3 Ἡ οὖν Μαριὰμ λαβοῦσα λίτραν μύρου νάρδου πιστικῆς πολυτίμου ἤλειψεν τοὺς πόδας τοῦ Ἰησοῦ καὶ ἐξέμαξεν ταῖς θριξὶν αὐτῆς τοὺς πόδας αὐτοῦ· ἡ δὲ οἰκία ἐπληρώθη ἐκ τῆς ὀσμῆς τοῦ μύρου. 4 Λέγει δὲ Ἰούδας ὁ Ἰσκαριώτης εἷς [ἐκ] τῶν μαθητῶν αὐτοῦ, ὁ μέλλων αὐτὸν παραδιδόναι· 5 διὰ τί τοῦτο τὸ μύρον οὐκ ἐπράθη τριακοσίων δηναρίων καὶ ἐδόθη πτωχοῖς;

My translation:

3 Then Mariam, after taking a pound of valuable myrrh of pure nard, anointed the feet of Yeshua and wiped his feet with her hair; and the house was filled of the smell of the myrrh. 4 And Judas the Iscariot, one of his disciples, the one about to give him over, says, 5 “On what account was this myrrh not sold for three hundred denarii and given to poor people?”

Notes:

12:3

Consult good commentaries for the possible identification of this story with the similar ones in Mark 14 and Luke 7. ICC & CGT conclude that Mary of Bethany is the anointer in all three stories, but that they refer to two distinct events, the present anointing of John 12 being a planned reproduction of the earlier, spontaneous one. This conclusion explains several of the oddities of the episode, including that: Mary apparently had no access to a towel in Martha’s home, that the feet were anointed (rather than the head), and that the oil was wiped off (EGGNT).

οὖν is transitional (“Then”, NIV, NET, HCSB).

ἡ Μαριὰμ is the subject of the main aorist verbs below.

The feminine 2nd aorist participle λαβοῦσα (from λαμβάνω) is temporal-antecedent (“after taking”) with the two main aorist verbs below.

ἡ λίτρα (2x, both in John) is, “a (Roman) pound” (BDAG), equivalent to 327 grams or 12 ounces, the origin of (though not the equivalent of) the English liter; NIV: “about a pint”; NET: “three quarters of a pound”. μύρου (“ointment, perfume”; see note on 11:2) is a genitive of content with λίτραν, which is the direct object of the participle above.

ἡ νάρδος (2x) refers to the (spike)nard plant of India from which an aromatic oil is derived. The genitive νάρδου is a genitive of material after μύρον above.

The adjective πιστικός (2x) is, “genuine, unadulterated” (BDAG); most translations: “pure”. The word may derive from ἡ πίστις, “trustworthy”, but ZG suggests the term derives etymologically from the Aramaic word for pistachio and indicating the base of the perfume. The feminine πιστικῆς modifies ἡ νάρδος above.

The adjective πολύτιμος (3x) is, “very precious, valuable” (BDAG), from πολύς + ἡ τιμή “price, value, worth”. NASB: “very costly”; NIV, NET, NASB: “expensive”. The two-termination adjective is the same in the genitive whether feminine or neuter, so πολυτίμου could modify either ἡ νάρδος (the word order lends toward this) or τό μύρον (so most translations).

ἡ Μαριὰμ above is the subject of the aorist ἤλειψεν (from ἀλείφω “I anoint”; see note on 11:2). τοὺς πόδας, modified by possessive genitive τοῦ Ἰησοῦ, is the direct object of ἀλείφω.

ἡ Μαριὰμ is also the subject of the aorist ἐξέμαξεν (from ἐκμάσσω “I wipe, dry”; see note on 11:2). ταῖς θριξὶν (“hair”; see note on 11:2), modified by possessive genitive αὐτῆς referring to Mary, is an instrumental dative. τοὺς πόδας, modified by by possessive genitive αὐτοῦ referring to Jesus, is the direct object of the verb.

ἡ οἰκία is the subject of the aorist passive ἐπληρώθη (from πληρόω).

ἡ ὀσμή (6x) is, “odor, smell, fragrance” (BDAG), from ὄζω “I emit a smell” (cf. 11:39). The passive of πληρόω with its object (the thing doing the filling) takes a variety of constructions in the NT, usually πληρόω + genitive (cf. Acts 13:52, Rom. 15:14, 2 Tim. 1:4) but sometimes the object is in the dative (cf. 2 Cor. 7:4), accusative (Col. 1:9), or ἐν + dative (Eph 5:18). Here alone is πληρόω followed by the preposition ἐκ (although Mt. 23:25 uses ἐκ this way with synonym γέμω). ἐκ τῆς ὀσμῆς is properly partitive, but is equivalent to a genitive of content. The genitive τοῦ μύρου modifies τῆς ὀσμῆς and denotes source.

12:4

The subject of the historical present λέγει (from λέγω) is Ἰούδας. The articular ὁ Ἰσκαριώτης (variant spelling of Ἰσκαριώθ) stands in apposition to Ἰούδας (prob. meaning, “Judas, the Keriothite”), in apposition to which stands the numeral εἷς modified by the partitive prepositional phrase [ἐκ] τῶν μαθητῶν αὐτοῦ, in apposition to which stands the substantival present participle ὁ μέλλων (from μέλλω; NRSV, HCSB: “who was about to”; NET: “who was going to”; NIV: “who was to”; NASB: “intending to”). αὐτὸν, referring to Jesus, is the direct object of the present infinitive παραδιδόναι (from παραδίδωμι) which is complementary with μέλλω.

12:5

διὰ τί is, “On account of what?”, “Why?”, modifying the main verb ἐπράθη below.

πιπράσκω (9x) is, “I sell”. The near demonstrative pronoun τοῦτο is attributive with τὸ μύρον (“ointment, perfume”; see note on 11:2) which is the subject of the negated 2nd aorist passive οὐκ ἐπράθη.

The numeral τριακόσιοι is, “three hundred”, from τρεῖς (gen. τρία) + ἑκατόν (17x) “one hundred”, which turns into root -κος in multiples (see note on 6:7). τριακοσίων is attributive with δηναρίων (“denarius”; see note on 6:7) which is a genitive of price. The unexpressed subject of the aorist passive ἐδόθη (from δίδωμι) is the 300 denarii; NRSV, NIV, NET: “the money”. The substantival πτωχοῖς (“to poor people”) is the indirect object of the verb.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

«Εμοί δε μη γένοιτο καυχάσθαι ει μη εν τω σταυρώ του Κυρίου ημών Ιησού Χριστού, δι’ ου εμοί κόσμος εσταύρωται καγώ τω κόσμω» (Γαλ. 6,14)

"Ει απολύσεις τούτον τον άνθρωπον, ουκ ει φίλος του Καίσαρος"...

"Ποιμένες πολλοὶ διέφθειραν τὸν ἀμπελῶνά μου, ἐμόλυναν τὴν μερίδα μου, ἔδωκαν τὴν μερίδα τὴν ἐπιθυμητήν μου εἰς ἔρημον ἄβατον, ἐτέθη εἰς ἀφανισμὸν ἀπωλείας Οτι τάδε λέγει Κύριος περὶ πάντων τῶν γειτόνων τῶν πονηρῶν τῶν ἁπτομένων τῆς κληρονομίας μου, ἧς ἐμέρισα τῷ λαῷ μου ᾿Ισραήλ· ἰδοὺ ἐγὼ ἀποσπῶ αὐτοὺς ἀπὸ τῆς γῆς αὐτῶν καὶ τὸν ᾿Ιούδαν ἐκβαλῶ ἐκ μέσου αὐτῶν καὶ ἔσται μετὰ τὸ ἐκβαλεῖν με αὐτοὺς ἐπιστρέψω καὶ ἐλεήσω αὐτοὺς καὶ κατοικιῶ αὐτούς, ἕκαστον εἰς τὴν κληρονομίαν αὐτοῦ καὶ ἕκαστον εἰς τὴν γῆν αὐτοῦ"

Σταυρός, «ἡ ὡραιότης τῆς Ἐκκλησίας»

Σήμερον ο Ιούδας παραποιείται θεοσέβειαν και αλλοτριούται του χαρίσματος· υπάρχων μαθητής γίνεται προδότης· εν ήθει φιλικώ δόλον υποκρύπτει και προτιμάται της του Δεσπότου αγάπης τριάκοντα αργύρια, οδηγός γενόμενος συνεδρίου παρανόμου. Ημείς δε, έχοντες σωτηρίαν τον ��ριστόν, αυτόν δοξάσωμεν

☦️

"Ὁ μέν κόσμος ἀγάλλεται, δεχόμενος τὴν λύτρωσιν, τὰ δέ σπλάγχνα μου φλέγονται, ὁρώσης σου τὴν σταύρωσιν, ἤν ὑπέρ πάντων ὑπομένεις, ὁ Υἱός καὶ Θεός μου"

youtube

Σὲ τὸν ἀναβαλλόμενον, τὸ φῶς ὥσπερ ἱμάτιον, καθελὼν Ἰωσὴφ ἀπὸ τοῦ ξύλου, σὺν Νικοδήμῳ, καὶ θεωρήσας νεκρὸν γυμνὸν ἄταφον, εὐσυμπάθητον θρῆνον ἀναλαβών, ὀδυρόμενος ἔλεγεν· Οἴμοι, γλυκύτατε Ἰησοῦ! ὃν πρὸ μικροῦ ὁ ἥλιος ἐν Σταυρῷ κρεμάμενον θεασάμενος, ζόφον περιεβάλλετο, καὶ ἡ γῆ τῷ φόβῳ ἐκυμαίνετο, καὶ διερρήγνυτο ναοῦ τὸ καταπέτασμα· ἀλλ’ ἰδοὺ νῦν βλέπω σε, δι’ ἐμὲ ἑκουσίως ὑπελθόντα θάνατον· πῶς σε κηδεύσω Θεέ μου; ἢ πῶς σινδόσιν εἱλήσω; ποίαις χερσὶ δὲ προσψαύσω, τὸ σὸν ἀκήρατον σῶμα; ἢ ποῖα ᾄσματα μέλψω, τῇ σῇ ἐξόδῳ Οἰκτίρμον; Μεγαλύνω τὰ Πάθη σου, ὑμνολογῶ καὶ τὴν Ταφήν σου, σὺν τῇ Ἀναστάσει, κραυγάζων· Κύριε δόξα σοι

☦️

youtube

Ἡ ζωή ἐν τάφω

κατετέθης, Χριστέ,

καί ἀγγέλων στρατιαί ἐξεπλήττοντο,

συγκατάβασιν δοξάζουσαι τήν σήν.

Ἡ ζωή, πῶς θνήσκεις;

πῶς καί τάφω οἰκεῖς;

τοῦ θανάτου τό βασίλειον λύεις δέ,

καί τοῦ Ἅδου τούς νεκρούς ἑξανιστᾶς.

Μεγαλύνομεν σέ,

Ἰησοῦ βασιλεῦ,

καί τιμῶμεν τήν ταφήν καί τά πάθη σου,

δί' ὧν ἔσωσας ἠμᾶς ἐκ τῆς φθορᾶς

☦️

«Εμοί δε μη γένοιτο καυχάσθαι ει μη εν τω σταυρώ του Κυρίου ημών Ιησού Χριστού, δι’ ου εμοί κόσμος εσταύρωται καγώ τω κόσμω» (Γαλ. 6,14)

Καλή Ανάσταση 🕯️

0 notes

Text

Μελετώντας κανείς προσεκτικά τά Ἱερά Εὐαγγέλια καί ἰδιαίτερα ἐκεῖνα τά κεφάλαια πού ἀναφέρονται στήν δημόσια δράση τοῦ Κυρίου ἡμῶν Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ, θά διαπιστώσει ὅτι τόν Κύριό μας τό ἀκολουθοῦσαν συγκεκριμένες ὁμάδες ἀνθρώπων. Μία ἀπ’ αὐτές ἦταν καί ἡ ὁμάδα ἐκείνη ἡ ὁποία ἀποτελοῦνταν ἀπό ἀνθρώπους πού ἀνήκαν σέ ὑψηλό κοινωνικό καί θρησκευτικό ἐπίπεδο. Ἦταν οἱ ἄνθρωποι ἐκεῖνοι οἱ ὁ... Περισσότερα εδώ: https://romios.gr/kyriaki-ie%ce%84matthaioy-i-agapi-pros-ton-theon-kai-ton-plision/

0 notes

Text

Filipenses 4.6-7 - Oração X Ansiedade

“Não andem ansiosos por coisa alguma, mas em tudo, por meio da oração e da súplica, com ação de graças, apresentem os seus pedidos a Deus. Então, a paz de Deus, que excede todo o entendimento, guardará o coração e os pensamentos de vocês em Cristo Jesus.”

Μηδὲν μεριμνᾶτε (Meden Merimnate): "Não estejais ansiosos por coisa alguma": Uma proibição total da ansiedade e da preocupação, indicando abstenção permanente desse estado mental.

Ἐν Παντὶ (En Panti) "Em tudo": Indica que não há área da vida isenta da influência da oração.

Τῇ Προσευχῇ (Tē Proseuchē) e Τῇ Δεήσει (Tē Deēsei) "Pela oração" e "Pela súplica": A comunicação direta e humilde com Deus, caracterizada pelo elemento adicional de fervor.

Μετὰ Εὐχαριστίας (Meta Eucharistias) "Com ação de graças": O componente da gratidão é indispensável à oração, mostrando a importância de uma atitude agradecida perante Deus.

Τὰ Αἰτήματα Ὑμῶν (Ta Aitēmata Hymōn: "Os seus pedidos": As petições específicas que os crentes são encorajados a apresentar a Deus, especialmente anseios, preocupações, necessidades e desejos.

Γνωριζέσθω Πρὸς Τὸν Θεόν (Gnōrizesthō Pros Ton Theon) "Façam conhecidos diante de Deus": Uma comunicação clara e objetiva, implicando em uma relação transparente com Deus.

ἡ Εἰρήνη Τοῦ Θεοῦ (Hē Eirēnē Tou Theou) "A paz de Deus": Enquanto o mundo busca paz externa, a paz de Deus trabalha no interior do homem, independentemente das circunstâncias externas.

ὑπερέχουσα Πάντα Νοῦν (Hyperēchousa Panta Noun): "excede todo entendimento": Vai além da totalidade da compreensão humana, incluindo intelecto, discernimento e conhecimento.

Φρουρήσει Τὴν Καρδίαν Καὶ Τὸν Νοῦν (Phroureí Tēn Kardían Kai Tòn Noûn) “guardará o coração e os pensamentos”: O cuidado de Deus com o emocional, intelectual e espiritual, envolvendo sentimento, vontade e raciocínio.

ἐν Χριστῷ Ἰησοῦ (en Christō Iēsou) "em Cristo Jesus": A união vital com Cristo, de quem emanam todas as bênçãos fundamentais para uma vida espiritual saudável.

Aprender praticando:

Integre Fp 4.6-7 de forma emocional e inovadora para explicar princípios religiosos na escola.

Aplique Mindfulness com base em Fp 4.6-7 para gerar bem-estar através da oração.

Desenvolva programas inspirados em Fp 4.6-7, fortalecendo laços interpessoais, alinhando-se à BNCC.

Integre Fp 4.6-7 em trilhas de meditação, conectando paz interior, natureza e ação de graças.

Organize eventos nas escolas unindo música com a mensagem de Fp 4.6-7.

Fomente ações sociais baseadas em gratidão, promovendo respeito à diversidade conforme a DUDH.

Estabeleça círculos de diálogo inspirados em Fp 4.6-7 para compreensão sobre oração e súplica.

Saiba mais:

• Missio Dei XXI: https://www.facebook.com/MissioDeiXXI

• YouVersion: https://my.bible.com/pt/bible/129/PHP.4.6-7

0 notes

Text

Τὸ Μυστήριο τοῦ χρόνου

«Ἀρχὴ τοῦ εὐαγγελίου Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ…». Καὶ μόνο ἡ λέξη «ἀρχὴ» τοῦ εὐαγγελικοῦ ἀναγνώσ��ατος ἀνάγει τὴ σκέψη μας συνειρμικὰ στὴν ἀρχὴ μιᾶς καινούργιας χρονιᾶς, ποὺ τὸν γιορτινὸ τnς ἀπόηχο ζοῦμε ἀκόμα, ἀφοῦ πρὶν ἀπὸ λίγο δρασκελίσαμε τὸ κατώφλι τnς. Ἡ χριστιανικὴ ἔννοια τοῦ χρόνου Ὁ ἄνθρωπος παλαιότερα ἔμενε ἐκστατικὸς μπροστὰ στὸ σκοτεινὸ αἴνιγμα τοῦ χρόνου. […] Τὸ Μυστήριο τοῦ χρόνου –…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Τὸ Μυστήριο τοῦ χρόνου

«Ἀρχὴ τοῦ εὐαγγελίου Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ…». Καὶ μόνο ἡ λέξη «ἀρχὴ» τοῦ εὐαγγελικοῦ ἀναγνώσματος ἀνάγει τὴ σκέψη μας συνειρμικὰ στὴν ἀρχὴ μιᾶς καινούργιας χρονιᾶς, ποὺ τὸν γιορτινὸ τnς ἀπόηχο ζοῦμε ἀκόμα, ἀφοῦ πρὶν ἀπὸ λίγο δρασκελίσαμε τὸ κατώφλι τnς. Ἡ χριστιανικὴ ἔννοια τοῦ χρόνου Ὁ ἄνθρωπος παλαιότερα ἔμενε ἐκστατικὸς μπροστὰ στὸ σκοτεινὸ αἴνιγμα τοῦ χρόνου. […] Τὸ Μυστήριο τοῦ χρόνου –…

View On WordPress

0 notes