#Às a’ Chamhanaich

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Link

A new Gaelic graphic novel from Bradan Press, coming in September 2021: Creatures magical and human, worlds strange and familiar, fantasy and a touch of horror. The debut graphic novel from Cape Breton author-artist Angus MacLeod is a collection of a dozen tales inspired by old stories, history, and ancient beliefs of the Gaels and the author’s imagination. Illustrated in black-and-white.

Creutairean draoidheil is daonnail, saoghalan céineach is aithnichte, fantasachd le fiamh uabhais. Sgrìobte ‘sa Ghàidhlig, tha dusan sgeulachdan ghoirid ‘sa chiad nobhail grafaig aig dealbhadair-sgrìobhadair Aonghas Mac Leòid á Ceap Breatainn. Tha buaidh nan seann sgeulachdan, eachdraidh ‘is seann chreideamhan a bhuineas do na Gàidheil agus mac-meanma an ùghdair ri ‘m faighinn ann an gach sgeul. Air an tarraing ann an dubh is geal.

#Leabhar#2021#Am Màrt#Bradan Press#Book#Aonghas MacLeòid#Gàidhlig#Gaelic#Scottish Gaelic#Cànan#Cànain#language#Languages#Langblr#Endangered Languages#Indigenous Languages#Graphic Novels#Cape Breton#Ceap Breatainn#Às a’ Chamhanaich

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

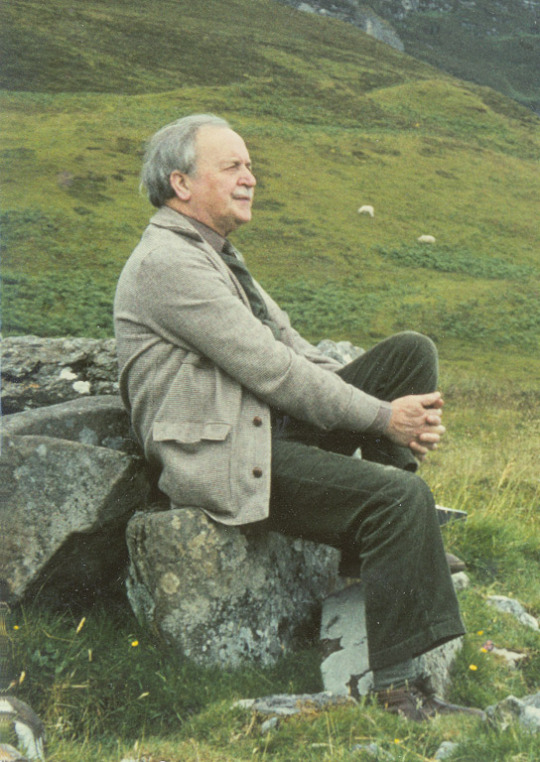

On October 26th 1911 the Gaelic poet, Sorley MacLean, was born on the island of Raasay, the same island my own ancestors originated.

Maclean was born at Osgaig on the island into a Gaelic speaking community. He was the second of five sons born to Malcolm and Christina MacLean. His brothers were John Maclean, a schoolteacher and later rector of Oban High School, who was also a piper, Calum Maclean, a noted folklorist and ethnographer; and Alasdair and Norman, who became GP's. His name in Gaelic was Somhairle MacGill-Eain.

At home, he was steeped in Gaelic culture and beul-aithris (the oral tradition), especially old songs. His mother, a Nicolson, had been raised near Portree, although her family was of Lochalsh origin her family had been involved in Highland Land League activism for tenant rights. His father, who owned a small croft and ran a tailoring business,[12]:16 had been raised on Raasay, but his family was originally from North Uist and, before that, Mull. Both sides of the family had been evicted during the Highland Clearances, of which many people in the community still had a clear recollection.

What MacLean learned of the history of the Gaels, especially of the Clearances, had a significant impact on his worldview and politics. Of especial note was MacLean's paternal grandmother, Mary Matheson, whose family had been evicted from the mainland in the 18th century. Until her death in 1923, she lived with the family and taught MacLean many traditional songs from Kintail and Lochalsh. As a child, MacLean enjoyed fishing trips with his aunt Peigi, who taught him other songs.[9] Unlike other members of his family, MacLean could not sing, a fact that he connected with his impetus to write poetry.

Sorley was brought up as a follower of the Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland, now if you think the Wee Free are strict, these guys think that The Wee Free are too lenient, but Sorley says he gave up the religion for socialism at the age of twelve as he refused to accept that a majority of human beings were consigned to eternal damnation. He was educated at Raasay Primary School and Portree Secondary School. In 1929, he left home to attend the University of Edinburgh.

While studying at Edinburgh University he encountered Hugh Macdiarmid who inspired him to write poetry. However, Maclean chose the Gaelic of his childhood rather than Scots.

After fighting in North Africa during World War II he embarked on his life-long career as a school teacher - working in Mull, Edinburgh and Plockton.

Maclean was one of the finest writers of Gaelic in the 20th century. He drew upon its rich oral tradition to create innovative and beautiful poetry about the Scottish landscape and history. He was also an accomplished love poet. However, writing in Gaelic limited his audience so he began to translate his own work into English. In 1977 a bilingual edition of his selected poems appeared - followed by the collected poems in 1989.

His fame as a poet began to spread during the 1970s - helped by the appearance of his work in Gordon Wright's Four Points of a Saltire. Seamus Heaney, who first met Maclean at a poetry reading at the Abbey Theatre Dublin, was one of his greatest admirers and subsequently worked on translations of his work.

One of Maclean's most celebrated poems is Hallaig which concerns the enforced clearance of the inhabitants of the township of Hallaig (Raasay) to Australia. A film, Hallaig, was made in 1984 by Timothy Neat, including a discussion by MacLean of the dominant influences on his poetry, with commentary by Smith and Heaney, and substantial passages from the poem and other work, along with extracts of Gaelic song

In 1990 Maclean received the Queen's Gold Medal for poetry. He died in 1996 at the age of 85.‘.

Tha tìm, am fiadh, an coille Hallaig’

Tha bùird is tàirnean air an uinneig

trom faca mi an Àird Iar

’s tha mo ghaol aig Allt Hallaig

’na craoibh bheithe, ’s bha i riamh

eadar an t-Inbhir ’s Poll a’ Bhainne,

thall ’s a-bhos mu Bhaile Chùirn:

tha i ’na beithe, ’na calltainn,

’na caorann dhìrich sheang ùir.

Ann an Sgreapadal mo chinnidh,

far robh Tarmad ’s Eachann Mòr,

tha ’n nigheanan ’s am mic ’nan coille

a’ gabhail suas ri taobh an lòin.

Uaibreach a-nochd na coilich ghiuthais

a’ gairm air mullach Cnoc an Rà,

dìreach an druim ris a’ ghealaich –

chan iadsan coille mo ghràidh.

Fuirichidh mi ris a’ bheithe

gus an tig i mach an Càrn,

gus am bi am bearradh uile

o Bheinn na Lice fa sgàil.

Mura tig ’s ann theàrnas mi a Hallaig

a dh’ionnsaigh Sàbaid nam marbh,

far a bheil an sluagh a’ tathaich,

gach aon ghinealach a dh’fhalbh.

Tha iad fhathast ann a Hallaig,

Clann Ghill-Eain’s Clann MhicLeòid,

na bh’ ann ri linn Mhic Ghille Chaluim:

chunnacas na mairbh beò.

Na fir ’nan laighe air an lèanaig

aig ceann gach taighe a bh’ ann,

na h-igheanan ’nan coille bheithe,

dìreach an druim, crom an ceann.

Eadar an Leac is na Feàrnaibh

tha ’n rathad mòr fo chòinnich chiùin,

’s na h-igheanan ’nam badan sàmhach

a’ dol a Clachan mar o thus.

Agus a’ tilleadh às a’ Chlachan,

à Suidhisnis ’s à tir nam beò;

a chuile tè òg uallach

gun bhristeadh cridhe an sgeòil.

O Allt na Feàrnaibh gus an fhaoilinn

tha soilleir an dìomhaireachd nam beann

chan eil ach coitheanal nan nighean

a’ cumail na coiseachd gun cheann.

A’ tilleadh a Hallaig anns an fheasgar,

anns a’ chamhanaich bhalbh bheò,

a’ lìonadh nan leathadan casa,

an gàireachdaich ‘nam chluais ’na ceò,

’s am bòidhche ’na sgleò air mo chridhe

mun tig an ciaradh air caoil,

’s nuair theàrnas grian air cùl Dhùn Cana

thig peilear dian à gunna Ghaoil;

’s buailear am fiadh a tha ’na thuaineal

a’ snòtach nan làraichean feòir;

thig reothadh air a shùil sa choille:

chan fhaighear lorg air fhuil rim bheò.

Hallaig

Translator: Sorley MacLean

‘Time, the deer, is in the wood of Hallaig’

The window is nailed and boarded

through which I saw the West

and my love is at the Burn of Hallaig,

a birch tree, and she has always been

between Inver and Milk Hollow,

here and there about Baile-chuirn:

she is a birch, a hazel,

a straight, slender young rowan.

In Screapadal of my people

where Norman and Big Hector were,

their daughters and their sons are a wood

going up beside the stream.

Proud tonight the pine cocks

crowing on the top of Cnoc an Ra,

straight their backs in the moonlight –

they are not the wood I love.

I will wait for the birch wood

until it comes up by the cairn,

until the whole ridge from Beinn na Lice

will be under its shade.

If it does not, I will go down to Hallaig,

to the Sabbath of the dead,

where the people are frequenting,

every single generation gone.

They are still in Hallaig,

MacLeans and MacLeods,

all who were there in the time of Mac Gille Chaluim:

the dead have been seen alive.

The men lying on the green

at the end of every house that was,

the girls a wood of birches,

straight their backs, bent their heads.

Between the Leac and Fearns

the road is under mild moss

and the girls in silent bands

go to Clachan as in the beginning,

and return from Clachan,

from Suisnish and the land of the living;

each one young and light-stepping,

without the heartbreak of the tale.

From the Burn of Fearns to the raised beach

that is clear in the mystery of the hills,

there is only the congregation of the girls

keeping up the endless walk,

coming back to Hallaig in the evening,

in the dumb living twilight,

filling the steep slopes,

their laughter a mist in my ears,

and their beauty a film on my heart

before the dimness comes on the kyles,

and when the sun goes down behind Dun Cana

a vehement bullet will come from the gun of Love;

and will strike the deer that goes dizzily,

sniffing at the grass-grown ruined homes;

his eye will freeze in the wood,

his blood will not be traced while I live.

)

26 notes

·

View notes