#[ exploring ancient and sacred temples ]

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#Famous temples in Delhi#Temples in Delhi#Spiritual journey in Delhi#Delhi temples guide#Religious places in Delhi#Must-visit temples in Delhi#Delhi's sacred temples#Hindu temples in Delhi#Delhi pilgrimage sites#Temples for spiritual seekers in Delhi#Delhi's divine places#Exploring the temples of Delhi#Historical temples in Delhi#Ancient temples of Delhi#Delhi's religious landmarks

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Haridwar & Rishikesh Spiritual Tour Discover the soul-stirring charm of Haridwar and Rishikesh, two sacred cities nestled along the Ganges. From the mesmerizing Ganga Aarti at Har Ki Pauri to the serene yoga retreats in Rishikesh, this tour blends devotion with tranquility. Ideal for spiritual seekers and nature lovers, the journey promises temple visits, riverbank serenity, and unforgettable experiences. Whether it’s a dip in the holy river or exploring ancient ashrams, a Haridwar-Rishikesh tour rejuvenates the body, mind, and soul.

#Haridwar & Rishikesh Spiritual Tour#Discover the soul-stirring charm of Haridwar and Rishikesh#two sacred cities nestled along the Ganges. From the mesmerizing Ganga Aarti at Har Ki Pauri to the serene yoga retreats in Rishikesh#this tour blends devotion with tranquility. Ideal for spiritual seekers and nature lovers#the journey promises temple visits#riverbank serenity#and unforgettable experiences. Whether it’s a dip in the holy river or exploring ancient ashrams#a Haridwar-Rishikesh tour rejuvenates the body#mind#and soul.

0 notes

Text

#Hatkoti Temple#Shimla Sacred Sites#Himachal Heritage#Spiritual Journey#Ancient Temples#Cultural Exploration#Historical Sites#Divine Retreat#Temple Architecture#Himalayan Spirituality#Nature Surroundings#Tranquil Haven#Pabbar River#Sacred Destinations#Cultural Heritage#Religious Exploration#Serene Temple#Exploring Shimla#Devotion#Himachal Pradesh Temples

0 notes

Text

#Mansa Devi Temple#Chandigarh Temples#Divine Serenity#Spiritual Journey#Sacred Spaces#Chandigarh Diaries#Temple Exploration#Cultural Heritage#Urban Spirituality#Chandigarh Vibes#Seeking Blessings#Divine Escape#Spiritual Oasis#Ancient Mythology#Temple Architecture#Chandigarh City

0 notes

Text

Illuminating the Mysteries: A Journey Within the Temple of Isis by Belle M. Wagner

Belle M. Wagner's "Within the Temple of Isis" takes readers on a captivating journey into the mystical realms of ancient wisdom, seamlessly blending historical richness with spiritual exploration. The book serves as a portal, inviting readers to delve into the sacred sanctuary of Isis, unraveling the secrets that lie within.

Wagner's prose is an enchanting tapestry that weaves together vivid imagery, profound insights, and a deep reverence for the spiritual traditions associated with the Temple of Isis. The author's meticulous research is evident, creating an authentic backdrop that breathes life into the narrative. Through her words, readers are transported to a bygone era, where the divine and earthly coalesce in a dance of profound significance.

The exploration within the temple is not merely a physical one; it's a journey of the soul. Wagner adeptly guides readers through the intricate corridors of mysticism, touching upon themes of self-discovery, transformation, and the universal quest for meaning. The prose dances with the rhythm of ancient rituals, creating an immersive experience that transcends time and space.

The strength of Wagner's narrative lies in her ability to balance historical accuracy with a poetic touch. She navigates the delicate line between scholarly discourse and accessible storytelling, ensuring that both seasoned researchers and casual readers can find value within the pages. The result is a book that not only informs but also inspires, making the esoteric wisdom of the Temple of Isis accessible to a broad audience.

"Within the Temple of Isis" is more than a book; it's a beckoning call to those seeking a deeper understanding of spirituality and ancient mysteries. Wagner's work is a testament to her passion for the subject matter and her commitment to sharing the timeless teachings embedded in the heart of the temple. For anyone ready to embark on a transformative odyssey, this book stands as a luminous guide, ready to illuminate the path within.

Belle M. Wagner's "Within the Temple of Isis" is available in Amazon in paperback 9.99$ and hardcover 17.99$ editions.

Number of pages: 108

Language: English

Rating: 7/10

Link of the book!

Review By: King's Cat

#Temple of Isis#Belle M. Wagner#Mysticism#Ancient Wisdom#Spiritual Exploration#Self-Discovery#Transformation#Esoteric Teachings#Sacred Sanctuary#Ancient Rituals#Spiritual Journey#Isis Worship#Historical Richness#Symbolism#Ancient Egypt#Mystical Traditions#Ritualistic Practices#Soulful Exploration#Profound Insights#Occult Knowledge#Divine Feminine#Spiritual Wisdom#Alchemical Mysteries#Symbolic Imagery#Transcendence#Ancient Temples#Metaphysical Exploration#Spiritual Awakening#Sacred Femininity#Hermetic Traditions

1 note

·

View note

Text

Illuminating the Mysteries: A Journey Within the Temple of Isis by Belle M. Wagner

Belle M. Wagner's "Within the Temple of Isis" takes readers on a captivating journey into the mystical realms of ancient wisdom, seamlessly blending historical richness with spiritual exploration. The book serves as a portal, inviting readers to delve into the sacred sanctuary of Isis, unraveling the secrets that lie within.

Wagner's prose is an enchanting tapestry that weaves together vivid imagery, profound insights, and a deep reverence for the spiritual traditions associated with the Temple of Isis. The author's meticulous research is evident, creating an authentic backdrop that breathes life into the narrative. Through her words, readers are transported to a bygone era, where the divine and earthly coalesce in a dance of profound significance.

The exploration within the temple is not merely a physical one; it's a journey of the soul. Wagner adeptly guides readers through the intricate corridors of mysticism, touching upon themes of self-discovery, transformation, and the universal quest for meaning. The prose dances with the rhythm of ancient rituals, creating an immersive experience that transcends time and space.

The strength of Wagner's narrative lies in her ability to balance historical accuracy with a poetic touch. She navigates the delicate line between scholarly discourse and accessible storytelling, ensuring that both seasoned researchers and casual readers can find value within the pages. The result is a book that not only informs but also inspires, making the esoteric wisdom of the Temple of Isis accessible to a broad audience.

"Within the Temple of Isis" is more than a book; it's a beckoning call to those seeking a deeper understanding of spirituality and ancient mysteries. Wagner's work is a testament to her passion for the subject matter and her commitment to sharing the timeless teachings embedded in the heart of the temple. For anyone ready to embark on a transformative odyssey, this book stands as a luminous guide, ready to illuminate the path within.

Belle M. Wagner's "Within the Temple of Isis is available in Amazon in paperback 9.99$ and hardcover 17.99$ editions.

Number of pages: 108

Language: English

Rating: 7/10

Link of the book!

Review By: King's Cat

#Temple of Isis#Belle M. Wagner#Mysticism#Ancient Wisdom#Spiritual Exploration#Self-Discovery#Transformation#Esoteric Teachings#Sacred Sanctuary#Ancient Rituals#Spiritual Journey#Isis Worship#Historical Richness#Symbolism#Ancient Egypt#Mystical Traditions#Ritualistic Practices#Soulful Exploration#Profound Insights#Occult Knowledge#Divine Feminine#Spiritual Wisdom#Alchemical Mysteries#Symbolic Imagery#Transcendence#Ancient Temples#Metaphysical Exploration#Spiritual Awakening#Sacred Femininity#Hermetic Traditions

1 note

·

View note

Text

Apollo as a Queer Deity

The Death of Hyacinthos (1801) by Jean Broc

Apollo has had many male lovers in Greek mythology. Most famously, he loved the young mortal Hyacinthus, the namesake for the hyacinth. But the list doesn’t stop there.

Admentus

Admentus of Pherae was the mortal king Lord Apollo was sentenced to serve for a year as punishment for slaying the Python at Delphi. Writers such as Plutarch, Callimachus, Tibullus, and Ovid described Apollo’s affection for Adementus with homoerotic overtones. Callimachus wrote that Apollo was “fired with love” for Admentus. In addition to his servitude, Apollo helped Admentus prolong his life by getting the Fates drunk and persuading them to let Admentus live, so long as he could find someone else to die in his place. When his parents would not die for him, Alecstis, Admentus’s wife, died for him instead. After realizing he didn’t want to live without his wife, Heracles - who was impressed with Admentus’s kind treatment of guests - descended into the Underworld and fought Thanatos, ultimately winning and returning Alecstis to the Land of the Living.

Adonis

Adonis was loved by many deities, Apollo included. Adonis was said to “act as a man with Aphrodite and act as a woman with Apollo.”

Branchus

Branchus was a seer of Apollo and in some traditions, is his lover. Sometimes Branchus was born with his seer abilities and other times his abilities are a gift from the god he received later in life. In his adulthood, Branchus worked in animal husbandry. Apollo, enamored with Branchus’s beauty, disguised himself as a goatherd. Apollo revealed his divinity by milking a male goat. After revealing his divinity, Branchus and Apollo became lovers and Branchus established a temple for Apollo at Didyma.

Cyparissus

Cyparissus was a boy whom Apollo loved. He gifted the boy a stag, but Cyparissus accidentally killed his beloved stag in a hunting accident. He prayed to Apollo for his grief to be immortalized, so Apollo changed him into a Cypress tree, which became sacred to Apollo.

Hyacinthus

Hyacinthus was a mortal youth whom both Apollo and Zephyrus loved. One day, while Apollo and Hyacinthus played discus a jealous Zephyrus looked on. Zephyrus, god of the west wind, decided to punish the couple by manipulating the winds, causing the discus to strike Hyacinthus in the head and killing him. Apollo, overcome with grief, immortalized his beloved by turning him into a hyacinth.

Some scholars interpret this myth as the hot sun killing crops in the summertime, as Hyacinthus was a minor Cthonic vegetation deity.

Iapyx

Iapyx was a favorite of Apollo and they were potentially lovers. Apollo wanted to bestow a gift on Iapyx. Iapyx elected to receive a longer life and skilled healing abilities.

My Personal Experience:

When I was 14, I cut all of my long, dark hair off which marked the beginning of my physical transition. I spent my teen years exploring my identity and coming into myself. The same time I overcame some prominent internalized transphobia was around the time I became a Hellenic polytheist. In an act of societal defiance, I decided to grow my hair back out.

I was 19 and completely on my own for the first time, and that year was one of the most transformational years of my life (so far). I learned about manhood, adulthood, and what masculinity means to me. Eventually though, it was time for me to cut all of my hair off. I had learned a lot about myself, one of them being I hate having long hair.

So again, I cut off my long, dark hair, this time with a better understanding of who I was and where I was going. In ancient times, boys would cut off their hair in the name of Apollo to signify their transition to manhood, and that is exactly what I did. Now, my last lock of long hair sits in an envelope, next to another labeled "First haircut, 2004" on my Apollo altar.

I don't know if many people turn to Apollo as a queer god, especially for transness. But with the journey I've been on, it only felt right.

Sources:

Homoerotic themes in Greek and Roman mythology - Wikipedia

Hyacinth (mythology) - Wikipedia

CYPARISSUS (Kyparissos) - Cean Prince of Greek Mythology

Branchus in Greek Mythology - Greek Legends and Myths

Admetus of Pherae - Wikipedia

Alcestis - Wikipedia

Iapyx - Wikipedia

Adonis - Wikipedia

Divider: @cafekitsune

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sacred Sites

Taking us on a journey through the history of sacred art and architecture, Sacred Sites explores the myriads of ways in which we imbue our environments with profound and enduring meaning. From our early designation of nature and the body as temple to our futuristic embrace of imaginary realms, we travel the vast and mystical landscapes of myth, religion, and imagination.

Library of Esoterica series, Sacred Sites, by TASCHEN. A visual pilgrimage through holy mountains, great pyramids, and golden shrines, Sacred Sites celebrates the ways we transform the world around us through ritual, creativity, and worship. Essays, interviews and more than 400 images explore spaces ranging from ancient temples to modern works of spatial art.

326 notes

·

View notes

Text

slake-hot longing (da:i solavellan oneshot)

basically: An adaptation of this comic by @westlywheatly; "ancient Elven god falls in love because local woman snores louder than the voices in head telling him not to." rating: T words: 3.2k content warnings: near-fatal levels of denial. handle with care lest he infect you too!!!

Even that which he could not help but loathe: her vallaslin... June’s antlers cradled her cheekbones, as they had on thousands of slaves, but.. ink in skin, all told. The woman before him, for the most part, was meaningless. Brimming with irrelevant intentions; whatever had caused her to come, in a pretense of dishabille, all tousled hair and draped cloth, clavicle— Solas curled the fingers upon his brow bone, and sank his nails in. Broke through. Found blood. Worsened the situation, for the most part; a raw and wailing something rolled up through his ribs, and hitched his breath—he slipped his hand down his face, made a fist against his quivering mouth, pressed a surging gasp back.

🎨 read on ao3 or ↓

A painted picture, a backlit canopy Try to dive, but I'm already sunk / drown in the water, drown ‘til I'm drunk Shamelessly, knee-deep in your fantasy / to stay up late, collecting battle scars It′s hard on the body, hard on the heart —Hard on the Heart, Kingsborough

|

Experience did not render one immune to follies of ambition. Gone were the days when Solas could lift his tools with his thoughts alone, and wet a building's worth of plaster with the gentlest touch. But those days were only gone for the time being—he often forgot that, when feeling far too lowly or highly of himself.

He had thought rather highly of himself when laying down the plaster before him. Two heads taller than he, and thrice as wide; curved at the top and bottom, it left room for the sections that would comprise the Breach, and the Temple of Sacred Ashes below.

Sketching the alasleala had not taken too long, and colouring the sky had only been a matter of slapping colour down to fit a shape without breaching its outline; objectively, child's play. All that remained were nine beams of magic slitted throughout the sunset, and twenty small, orange triangles.

Which, thanks to the size of the damnable thing, would take hours.

Solas crouched, dabbing a spalter brush back and forth between yellow and white and water and yellow and white and water. The muscles in his thighs protested; still, he’d resolved to not nag the Fade to mix pigments for him.

Folly, perhaps, but considerate folly… ‘ambition’ was perhaps not the word for it. He’d only laid as much plaster as he did due to time spent with equals, after all.

Wisps wandered above, skimming the vunin; trace emotions, sharing their illumination with his canvas—and their warmth, with him. They were attentive, for the most part; even when they did roam aimlessly, as he’d welcomed them to do, they never strayed too far. Wisps’ explorative nature came about from a sense of security: a safe environment, pleasant company.

Solas.

Solas, even as Fade-deprived as he was. Solas, homesick for the hearth of purpose, who cherished wisps more than anyone else alive; whose soul, left aimless, was typically less a result, and more a prelude. (To a regret, historically speaking.)

When he’d troweled down the plaster, the wisps favoured Faith and Hope, and encouraged him. The vunin's size might not indicate ambition, but… he might've laid the foundation for a rather large regret. In an hour or two, Solas might press his brush to the plaster and find it dry. Unworkable, it would need to be scraped away, the entirety of his efforts, torn down, and attempted another time.

Hope yet lingered, however, and so he let it guide his hand.

Brush tipped with a blend of buttery yellow, Solas traced along a beam's outline; a wisp bobbed atop, chased up and up the wall. He smiled. Whatever will you become, my friend? Do you know where we are going?

As Solas neared the limit of his reach, the wisp sizzled to Curiosity, bouncing away from the wall, up toward—ah.

Her.

Against the gloomy backpaint of the library, draped over the balustrade: the Inquisition’s leader, in fanciful likeness. Smudged together by lampblack and umber; streaked through by lime-white layered with lead-tin yellow, for she—audacious she—had perched a lit candle holder on the rail.

(Why, in a sconce-laden fortress, carry a single candle?) Its scant light draped shadows in the white shawl around her shoulders, beneath which she wore a matching bandeau—

Alabaster, then; the shawl, alabaster, and the rest, not pigment, marble, for she posed above, still as a statue, and were she one, the soft weathered bronze of her skin would be depicted in pale similitude.

Quite simply done, seeing the Inquisitor as no more than a graven image, practically automatic. Little wonder Andrastians took to it so quickly.

(Had she come directly from her chambers, it would bring her through the door to his left. Why navigate up to the library by avoiding the rotunda, if not to catch Solas unaware, and address him from above?)

(Fenedhis, why was she in her nightclothes?!)

“Do you usually paint with an audience?” she asked, cheek resting on the back of her hand.

Solas tightened his grip on the paintbrush, and cleared his throat. “The wisps are harmless,” he said. “They only offer their light, and company.” And temptation, to this or that da’len fool enough to chase them into a bog, if Keepers are to be believed, yes.

“Would you mind”—already picking up the candle, trailing her hand along the balustrade, moving, presuming—“the presence of one more?”

“Do as you wish, Inquisitor,” Solas replied. He turned away from her performance of languidity, resumed painting. Completing the vunin before its plaster dried, and protecting the wisps? Feasible. Predicting the script of whatever she intended... less so.

Her voice floated down the stairs. “I was not asking to join you as Inquisitor.”

“Pray tell, then, to who do I speak?” he asked, eyes steeled on the brush’s metal ferrule, gilded by any passing wisps.

A few feet to the left, a delicate clink, then: “a wisp.”

Solas lifted the brush from the wall, and looked over.

Self-proclaimed wisp, having placed her candle on the floor, eased down next to it. Several actual, literal wisps gravitated to the candle's light. Close enough for their purposes to render her spirit kaleidoscopic, confused, yet her eyes remained steady; on him. “Only here to offer light and company,” she said, gently.

Falsely.

Discerning her intentions always took a level of focus. Focus better dedicated to the wall. The plaster. Which bore four hours of moisture, at most, and from which corporeal company ‘offered’ only distractions. Of which, Solas could at least anticipate one.

“Wisps,” he said, gesturing to those by the candle, “are not known for being capable of speech.”

“Then I must be a very strange wisp,” she murmured. She rested her head against the wall; nowhere near the edge of the vunin, to his relief. The dark waves of her hair caught a passing wisps’ shine, like a moonlit ocea—

It was warm light, on hair, black as the tassels on her shawl and the pupils in her eyes; black was a pigment, or a lack, and absurdity need not taint Solas’ interaction with the ‘very strange wisp’ any further. He returned to his work.

“Quite,” he replied, finally. Perhaps she indeed considered the wisps harmless... as she might consider moths. Part of a minute, unintelligent species, mistaking any light for that which orients them, and only incidentally a nuisance. (Compared to which she would be...) “Certainly unlike any I have previously encountered.”

“You will have to teach me how to behave like the others.”

The paintbrush skipped; Solas firmed his grip. “I see.”

He risked a glance. Between her fingers spun the sun in miniature. It slipped free, unresisted, and warmed his cheek as it passed; Purpose.

“It would depend...” he said, crouching to dip his brush once more, “what kind of wisp you are.”

Her fellows moved stars through the abyss of her eyes; a smile eased onto her face. “You have three guesses.”

“How generous,” Solas muttered; considering you do not know what types there are, or how many—

“Not generosity.”

He sighed. “Inquisitor,”

“Not that either...” she murmured, soft-eyed, softly echoing his sigh—before her eyes fell shut.

Solas firmed his mouth. “Hm.”

Each wisp dipped slightly, to keep him within their orbit; her eyelids... shone. Sweat had gathered in the crease of her eyelid; the heat from the candle, or the day’s exertions, damp on her orbital rim...

Visceral thing, closeness. Best avoided. Solas stood up, resting his hands on his hips, and glanced back down at her. For one long inhale, she looked... each word was shooed from his head, until her eyes opened, and she looked—

He looked away. Stared at the sunset he’d smeared into the plaster. Exhaled.

Perhaps the conversation could do some good.

“On my travels,” Solas began, as he often did, “I encountered a wisp that led me to Haven.” Night air, snow-pinched cheeks, its warmth, entrusted to his palm... “It brought me near the temple, and we swam in the poignant memories of those who had worshipped there.”

Her lips parted (audibly; his eyes had thus far remained obedient, and were fixed on the wall) and she inhaled, slowly.

Solas gave her a heartbeat or two, to speak... then he continued, “I initially considered it Faith, or Courage. But it was—”

Honking.

Something honked, near—Solas glanced down.

She’d honked.

Face nestled against the wall, she snored, loudly, and once a few seconds passed, continued to do so longer than mockery required. Quite the achievement, falling asleep in a lit space—mortal forms were built to resist that. Solas frowned, keeping his eyes on the plaster her breath ghosted upon. To fall asleep in a lit space, while he spoke—well, Solas left, meandered into bittersweet memory, whilst his voice spoke, of…

His cheeks warmed.

“Foolishness,” he muttered.

Two wisps seared a path from his temple to his shoulder; flame-gold licks at the edge of his vision, his cynicism. Solas leaned away, and blessedly, found his face cooling. He allowed himself to deflate, hands falling from his hips, shoulders softening, watching the wisps drift toward the unfeeling plaster.

The not-wisp slumped against the wall had a pair of her own. One, by her face, wavered with her breath, while another caressed the top of her hand—the Anchor. The left hand of the woman below him was the Anchor; the silk of her shawl was the secretion of worms, and her vallaslin were slave markings, and despite thinking herself otherwise, she was foolish.

Intelligent, yes, and clever, certainly; craftier than June himself, the brute. Yet all Dalish were foolish. Inherently. From their rabbit hearts to their quick-withering skin, ignorance ran through Dalish veins as water did the venation of a leaf. Having poisoned the soil himself, Solas could scarcely blame them. (Hence never passing up the opportunity when he could.)

Near the Anchor, the orb of light that had been playing across the Inquisitor's knuckles slipped into her palm, and winked out. Truly asleep, then, and... the wisp trusted her, enough to slip across the Veil, and join her dream.

His chest stirred. From... ah! Humiliating—desire. Desire without fervency; the aftertaste of desperation, weak and faint as the rest of him.

He rubbed his neck, a reminder of his solidity, while his other hand dragged over his face. Both palms felt glacial, he knew he’d flushed again, he knew it; milk-thin skin, and meager rationale, could not keep back such longing.

Solas took a few steps back, away from the wisp-dotted wall where she—

Where a body slumped next to his work. The shape his eyes insensately returned to, when they’d beheld it plenty of times! Unconscious; asleep; awake, aggravating him! Bones, liquid, muscle, encased in scarred and speckled skin—moles, beauty spots, freckles, whatever she would call them. (She should call them ‘ralan’, for that was what they were, but she would not know that!)

To a feeble, want-softened mind, buoyed by sheer giddy terror, they looked like flecks of charcoal, not fallen, but pressed, carefully, against...

Pencils.

Pressed with pencils; kohl pencils created such marks, when nature had not, or, in Orlais, small patches of black velvet. Mouche, ‘flies’. Once positioned, renamed, to suit their purpose: la majesteuse, l’galante, l'impudent—indulgent sounds, throaty ones.

Solas swallowed, and reminded his chest to rise and fall.

Orlesians ran libelles about the elven Inquisitor; did they include disparagement of how indecipherable, how nonsensical, how full of irregularity her skin was? Which was no flaw, not at all—not at—more pertinently, nothing of her appearance need be indicative, or admirable, or... Even that which he could not help but loathe: her vallaslin... June’s antlers cradled her cheekbones, as they had on thousands of slaves, but... ink in skin, all told.

The woman before him, for the most part, was meaningless. Brimming with irrelevant intentions; whatever had caused her to come, in a pretense of dishabille, all tousled hair and draped cloth, clavicle—

Solas curled the fingers upon his brow bone, and sank his nails in.

Broke through.

Found blood.

Worsened the situation, for the most part; a raw and wailing something rolled up through his ribs, and hitched his breath—he slipped his hand down his face, made a fist against his quivering mouth, pressed a surging gasp back.

Teeth clamped around the side of his hand, Solas bit down, and anchored himself. Dragged his focus back to the vunin. He wanted to finish; the vunin would dry in a few hours, and he needed to finish that. After a few wet breaths against his fist, he grimaced, and released it. Oh, his focus and his—oh, drifting, right back to her, oh, of course it did.

I am the foolish one. As I have always been.

The possibility he preferred to keep at arm’s length caught him by the throat: he had a heart. It’d been tricked out of him. By her. At some point, she’d undone him. Swindled something out of Solas, after which, his heart fell loose. Millennia of neglect in an unwanted cavity; he should’ve anticipated it; once again, the Dalish was not to blame. How soundly she slept, beneath Fen'Harel’s glare. Chest rising and falling, her own heart secured, beneath... ah.

How soundlessly she slept.

A respite which seemed to have occurred beneath his ogling notice. Solas tore his eyes away.

Perhaps embarrassment over such exposure would follow her waking—or embarrassment over snoring, if she stumbled into a humble nature; once awake, she might laugh, lie, leave, any number of things, regardless, the panic in Solas’ chest subsided, and she was not awake. Beneath those shining eyelids was movement, that of one dreaming deeply. Deep enough for a wisp to guide her unconscious breath evenly through her body.

Perhaps she, too, did not sleep as much as—

Solas grimaced once more, and scrubbed ‘perhaps’ from his mind. He was wandering dangerously close to wondering. Difficult as it was to predict the woman, it was obvious what marks he’d leave upon her, eventually. He’d soil her, eager in indulgence, for he liked to daydream as he painted. Pigment often flew from the brush.

To the ground, went the brush in question; to her side went he, untying his apron as he did. With it in hand, Solas crouched—she did not stir—and draped it over her chest; it sagged, grey and weathered. She did not stir. Nor did she as he adjusted her shawl, tucking what he could beneath adequate cover.

He returned to the vunin, quiet as the wisps bobbing just above his head, casting light down upon the remainder of the sketch. The Inquisitor remained in the half-shadow of periphery, equally quiet, and harmless. While her company could present distraction, he need not be distracted.

Solas bent slowly, picked up his brush, and tapped its tip. Dry.

To dip it once more would break the silence. Display ingratitude to the wisp...

He crooked his finger, and coaxed the Veil, softly pressing, until the Fade eased through, and moistened the pigment beneath his touch. The plaster needed no intervention, and would be wet for a few more hours, at least. The orange triangles, the remaining shaft, then he’d wake the Inquisitor (and walk her to her room?)

(No.)

Solas rolled his shoulders, eyes trailing across the incomplete vunin. He’d harvested enough from the bitter crop of self-assurances. For one evening, at least.

He followed the path his eyes had tracked, making his way from one side of the horizon to the other, bending and crouching as he went, outlining the droplets of Fade scattered down from the Breach. Three wrist-flicks around the triangle, trimming it moon-bright, then tilting his hand for another quick coat.

Flick-flick-flick, angle, flick-flick-flick. On to the next, and so on.

A curious wisp tickled at his neck. He resisted brushing it away—it had not earned his frustration, floating as delicate as dandelion debris; just so, wisps carried the potential for all manner of emotions. Solas hoped it might move to float elsewhere. Flick-flick-flick, angle, flick-flick-flick.

The wisp bobbed out of sight, and Solas moved on to the next, and so on, and his breath soon steadied. Though the defiant ache for her refused to cease, or adopt any rhythm save that of the pain pulsing in his brow. Rebellion coursed through Solas' veins by nature, and just as naturally, his body desired its heart. What mattered was keeping his mind tethered where it belonged. Preventing it from falling to this or that distraction.

Flick-flick-foolishness, angle, angle, flick. Foolishness. Foolishness, to think her alike the Dalish, to compare her to Orlesians… Poisoned the soil indeed; he’d put oil in the watering can. No matter. Nevermind. Flick-flick-flick. ‘Whatever’. On to the next. Flick-flick-crack.

Solas’ grip gentled, and his free hand whipped out to catch the brush’s end before it could clatter to the ground. The rest of it felt light as wood shavings.

He opened his hand to find the analogy apt—the brush handle was broken to bits. As if having waited for his attention before announcing itself, pain rushed up to meet his nerves—and was pushed beneath the glow of his glare. The shallow wounds across his palm sealed; each speck of blood fled home.

He blinked. Crouched. Discarded the broken wood on the drop-cloth, by the water jars. From the closest one, he pinched a fresh brush. Two pads of fat around painted wood, trembling. Glaring at his own tremble did nothing.

Solas indulged anyway.

Despite the preferences of himself and the world, respectively, Solas was no spirit nor statue. She had affected him. Worked herself beneath his skin, parts he could not reach or didn’t wish to notice, she, a mortal. Not a wisp, or a weed, a flower, hothouse or outdoorsmen, a bud or a bloom—a thing, yet living. Real. A person?

What did it matter?

He did not know what she was, and so, he could not care for her.

No mark on her skin or stain on her shawl could rival what he’d done. What he would yet do. What could he offer—why? When? Before or after he razed her world to ash, would he offer light and company and for her wilt to be watched closely?

How safe the soul felt, snug by figures of speech. He’d hid behind metaphor for millennia, when whatever Solas was, or had ever been, he was entombed in flesh. For the foreseeable forever.

She does not deserve a fate any worse than the path I have already sown.

Solas stood, and wiped a Fade-touched thumb against his brow to silence the heartbeat there.

Flick-flick-flick, angle, flick-flick-flick, and so on. Painting, crouching, leaning, reaching; the occasional clink of glass, or scuff of his foot. Close-passing wisps were heat and nothing more, any dissident thoughts were lightning arced across his brain; fleeting, rare.

He completed the triangles quicker than expected, fetched the spalter brush, and carried on. Patted along the outline of the final beam, tap after tap after tap at the same angle, all the way up to the Breach, until his mind sharpened into focus, and he found himself... carefree. Definitively; Solas was carefree.

As the hours passed, he painted without a care in the world, a reverie broken only by Inquisitor Lavellan letting out a snore.

─

Thank you so much for reading! If you enjoyed it, please consider going to ao3 and leaving me a kudos (you don’t need to be logged in!) or dropping a Like/reblog here. Comments/replies are immensely appreciated too, but thank you for reading this far regardless!!

#(FYI vunin = his section of work for the day and alasleala = fresco sketch)#solavellan#solas x lavellan#solavellan fanfiction#dragon age fanfiction#dragon age#vallyn lavellan#harley needs a writing tag!!!! wee-woo!!

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is Yoni Massage? 🔥

Yoni massage is an ancient, sacred practice designed to awaken deep feminine energy, release emotional blockages, and cultivate profound pleasure. It is a full-body experience that focuses on honoring, healing, and awakening a woman's most intimate space—her yoni (Sanskrit for "sacred temple"). Unlike conventional massages, this practice is not just about touch—it’s about connection, trust, and unlocking the untapped reservoirs of pleasure and energy within.

🔥 Why is Yoni Massage So Powerful?

💫 Releases Emotional Blockages: The yoni holds unspoken stories—past lovers, heartbreaks, shame, and trauma. Through mindful touch, these emotional imprints are gently released, leaving behind freedom and lightness.

💫 Awakens Full-Body Pleasure: True pleasure is not just physical—it’s energetic. A skilled yoni massage activates dormant sensations, turning the entire body into a vessel of ecstasy.

💫 Deepens Connection to Self: This is not about performance or pleasing someone else—it’s about reclaiming your own body, your own desires, and your own divine pleasure.

💫 Expands Intimacy & Sensitivity: The more a woman knows her own pleasure, the deeper she can connect with a partner. Yoni massage heightens awareness, making every touch, every kiss, every embrace more electric.

💫 Activates the Feminine Essence: When a woman is in touch with her pleasure, she radiates confidence, sensuality, and power. It’s not just about feeling good—it’s about embodying the goddess within.

Why Every Woman Must Experience Yoni Massage?

Because every woman deserves to feel worshipped. Every woman deserves to experience pleasure without guilt. Every woman deserves to release, receive, and rise.

This is not just a massage—it’s a rebirth. A journey back to yourself, where you step into your full, radiant power.

Are you ready to awaken the goddess within? 🌹🔥✨

💌 Ready to explore this journey? DM now to learn more! 🔥

#tantra#bollywood#desi tumblr#desi romance#love#self love#ahmedabad#mumbai#goa#yoni massage#gujarat#lovers#desi#desi life#desi girl#intimate#intimacy#couple goals#couple#gorgeous#couples tantra#tantra massage#desire#romantic#romance#passion#kiss#touch

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

dirthamen and ghilan'nain's intertwined history — a theory

edit: if you read this, please check out the post-veilguard update i gave here!

the relationship between dirthamen and ghilan'nain within the lore has always been unclear but incredibly fascinating to me, and after these past few months of being haunted by it i think i've finally figured it out!

in this *very* long post i'll be breaking down their connections and piecing together theories to make sense of their dynamic and history, investigating the more puzzling elements of dirthamen's lore, and exploring how this all ties into the evanuris' eventual betrayal of mythal. i've kept this theory free of veilguard spoilers so everyone is able to read it!

—————

the connections

the reason why dirthamen and ghilan'nain's dynamic is often overlooked is because most of the ties they have to each other can be easily missed or are sometimes misinterpreted. there is only ONE codex entry that explicitly mentions them together, and while that is already widely discussed, there are many smaller connections between them. so here is everything i've found!

the bear mural:

this mural in dai shows a white antlered figure embracing a green bear. to me, it looks like the bear is being protective of the figure (judging by the fact that they are reaching up to it). the art style looks elven and it's used in a few locations, such as the skyhold barn...

...aaand at calenhad's foothold in the hinterlands:

and well well well, that's dirthamen's statue seated just above it...

so this mural seems to depict dirthamen as the bear and ghilan'nain as the antlered figure, specifically how the dalish may depict them in their legends:

dirthamen's sacred animal was the bear (x), (source is a dalish elf, this info is not found anywhere in elvhen lore)

ghilan'nain had "snowy white hair" and became the first halla (x), (source is a dalish elf, this info is not found anywhere in elvhen lore)

it should be said, the amount of actual elvhen lore we have is very limited, so these could in fact be true and not just misinterpreted by the dalish. though they've been twisted, dalish legends came from somewhere, and especially in ghil's example it makes complete sense to portray her as a woman with antlers and white hair when her sacred animal has antlers and white fur. and while dirthamen is mentioned only with corvids in ancient elvhen lore, they are mentioned as seperate entities than him, so the bear could in fact be the representation of himself. in any case, i'm proceeding with the assumption that this mural is indeed supposed to portray them.

so, as the figure is reaching out to the bear herself, i'm ruling out any possibility of the bear being hostile towards her. it looks like the bear is protecting her, from what? or who? above them is the moon, perhaps it's an indication that mythal is watching, and/or that the bear is protecting or hiding the antlered lady away from her?

———

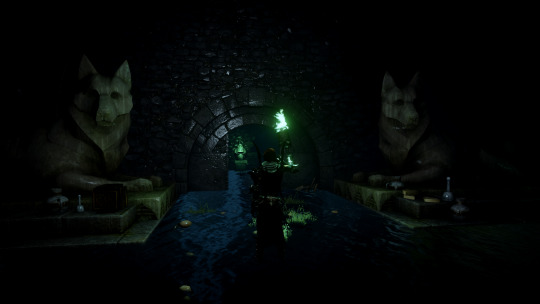

mosaics in the lost temple of dirthamen:

the design of dirthamen's temple is really fascinating. there's elven imagery scattered all throughout, but mosaics of himself are completely missing. there are, however, mosaics of two other elven gods...

there are five green mosaics of falon'din... and two red ones of ghilan'nain. next to one of ghil's there is also this:

falon'din being there makes sense given that he and dirthamen were "twin souls", which we're not entirely sure what that meant, but either way they had some sort of deep bond. ghilan'nain, however... and this specific mural... less so. this art in particular really reminds me of this description of the bas-reliefs from the horror of hormak:

"The halla were different, wrong. They had too many horns, for one, and a harder, more rounded look than normal. A look that was almost insectile. And the horns themselves were longer and ridged. Organic, somehow."

so, why would dirthamen have put her mosaics in his temple? clearly they had some sort of connection, close enough that he decided to honour her within his own place of worship. you don't just put some other god in your temple for no reason, you know?

on why dirthamen's mosaics are missing:

my best guess is that they were defaced/taken down afterwards, either by his own priests or by invaders. the codex entry for the lost temple mentions madness caused by the secrets they held...

"We will not have it, will not have it! The secrets are madness in our ears, but they are ours The Highest One cannot take them from us. Only Dirthamen, our Keeper, only he And if he does not take the secrets They are ours forever."

...and unless dismembering your high priest was a holy tradition to dirthamen then yeah, it doesn't seem like they were entirely sane. for whatever reason, in their madness, they could have torn down the mosaics.

though invaders seem more likely here, simply because they would have just... done a better job defacing mosaics if they truly wanted to. and to remove only dirthamen's mosaics, and not falon'din's or ghilan'nain's.

"They will come for us in the night Those who could steal the words from our lips And our god no longer rises to our defense."

this part of the codex implies that there were attacks on the temple by those who would steal the priests' secrets, and that dirthamen would defend them against these invaders. when he was locked away, he couldn't defend them anymore, and so these attackers could have easily gotten in. interesting... breaking in and removing his mosaics but not falon'din or ghilan'nain's would indicate a hostility towards dirthamen himself, but not the other gods...

———

the sinner:

by now we've all seen this widely discussed codex entry:

"His crime is high treason. He took on a form reserved for the gods and their chosen, and dared to fly in the shape of the divine. The sinner belongs to Dirthamen; he claims he took wings at the urging of Ghilan'nain, and begs protection from Mythal. She does not show him favor, and will let Elgar'nan judge him." For one moment there is an image of a shifting, shadowy mass with blazing eyes, whose form may be one or many. Then it fades.

so apparently "taking the shape of the divine" was a crime bad enough that it counts as high treason and mythal referred judgment to elgar'nan for it, which is REAL bad. this sinner claims ghilan'nain urged him to do it, but why? one would assume the sinner didn't survive elgar'nan's judgment, and if you really wanted someone dead there would be easier ways to kill them... so to me this reads as an attempt to sow discord, either between dirthamen's worshippers or to paint them as troublesome and dirthamen himself as irresponsible in the eyes of the other evanuris? at least that's my takeaway here.

———

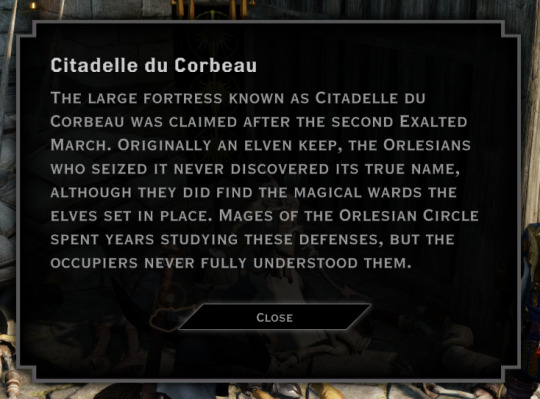

the next few are going to be smaller hints that basically rely on subtler location design and stuff like that. i could just be picking at nothing but it's worth mentioning either way!

ghilan'nain's grove and the crow fens:

there are two inaccesible areas in the exalted plains for which you need to complete war table missions to access: ghilan'nain's grove, and citadelle du corbeau. ghil's grove specifically leads you to two other areas: the dead hand, and the crow fens.

the crow fens are interesting because of dirthamen's connection to crows and/or ravens, as written in his dalish legend and by two of the runes from his quest:

"The revealed symbols show what appears to be Dirthamen, the elven god of secrets, on the back of a large crow."

"The revealed symbols show two ravens. One grips a heart in its talons, the other a mirror."

seems like the ravens are fear (heart) and deceit (mirror) while the crow is... idk, just some Big Bird he has. i guess.

so a location named after one of dirthamen's favourite animals right next to ghilan'nain's grove — and let's also go back to that other unlockable area, citadelle du corbeau:

there he is again! the structure is elven, maybe the citadelle was once a place of worship dedicated to him? it's interesting that it's in such close proximity to ghilan'nain's grove, and what's also interesting is the massive statue of fen'harel watching over the entire area:

finally, the description of the quest Rifts in the Fens, which covers the fade rifts in the general ghilan'nain's grove area, says this...

"Active Fade rifts has been spotted in Montevelan Village, Dirthamen's Grove, and the Crow Fens."

seems like it was mistakenly left in, but it definitely implies that ghilan'nain's grove was originally named dirthamen's grove. alright...

———

elven pantheon codex entry placements:

also a smaller one that may mean nothing, but anyway. each of the elven god codexes are scattered through the exalted plains, with four of them being located in the ghilan'nain's grove/crow fens region. these are:

Dirthamen: Keeper of Secrets & Falon'din: Friend of the Dead, the Guide — both found within the dead hand puzzle area

Andruil: Goddess of the Hunt & Ghilan'nain: Mother of the Halla — both found within the crow fens area, on halla statues standing opposite each other

these two pairings found in the same zone is really interesting, especially that dirthamen's is in an area closer to ghilan'nain's grove and ghil's is in the crow fens. :)

———

mosaic placements in the temple of mythal:

most of the elven god codexes in the temple of mythal are scattered about, with the exception of three who are bunched up in the same room together:

elgar'nan, dirthamen, and ghilan'nain.... interesting bunch to put together considering there are no documented interactions between them so far, save for the sinner codex (and ghil & elg now i guess....) in addition, there's also two golden owl (usually representing falon'din) statues flanking dirthamen and a mosaic of fen'harel to the left of elgar'nan, but those don't grant any additional codex entries.

the reason i find these placements interesting is because of the placements of the falon'din and andruil murals in the temple. they're both on either side of the door to the inner sanctum and both of their codex entries mention mythal fighting them. it just seems very deliberate to me, so maybe this is too.

———

the varterral:

i've seen a few theories about the varterral being one of the creatures that ghilan'nain created - valid, by the way, since it does look like a mix of creatures and something she may create. however...

"...On the fourth day, Dirthamen heard them. He whispered into the mountains and the fallen trees of the forest gathered, shaping an immense and agile spider-like beast. It was the varterral. With lightning speed, vicious strikes, and venomous spit, it drove back the serpent. From then on, it was the guardian of the city and its people." — Codex entry: Varterral

here dirthamen is credited with the creation of the varterral. but it's worth noting that, 1. this is a dalish tale so it may have happened differently, and 2. it's not stated that he created the first varterral or anything, just that he made one. regardless, he made a creature, and an awfully ghil-flavoured one at that.

—————

theories on dirthamen & ghilan'nain's relationship

so what we know now is that they're placed next to each other a lot, there's a mural of them embracing, ghilan'nain was clearly important enough to dirthamen for him to put her mosiacs in his temple, and she may have turned against him later.

firstly, an idea: in ancient elvhenan, a lot of the population were enslaved to the evanuris, whether directly or indirectly through a noble that served them. we don't know if the nobles, or any of the chosen, also had vallaslin like the slaves did. but consider that ghilan'nain was once a normal elf; she became an evanuris later. so the two possibilities here are: 1. she was one of these nobles or chosen, or 2. she was a slave. either way the question remains: which god does someone who makes monsters serve?

the most likely suspects:

andruil: in dalish lore ghil is often mentioned as andruil's favourite, her beloved, a huntress who served her, etc. in the elvhen story of her ascension, it is andruil who approaches her with the offer of godhood. it's possible ghil was making monsters for andruil to hunt (she is specifically mentioned in the story as hunting them,) or perhaps andruil simply intervened when the monsters were getting out of hand first, and their relationship came later?

dirthamen: ghil was a scientist... she made monsters yes, but she conducted experiments and collected research (remember the taken shape?) — she gathered knowledge. that seems just like the kind of thing dirthamen would encourage and value: maybe that's why her mosaic is in his temple, and that's what the bear mural means — he was like a patron to her, she reached to him for assistance, and he granted it?

as for the servant/slave question, i personally think she was not a slave, just based on all she was able to do (she had free rein of all those thaigs, seemingly got subjects delivered to her, had that massive gemstone wall — basically, it's clear her experiments were funded) although i do think it would be super badass if she was a slave beforehand, as well as kinda tragic. like... she broke free of her bindings and became a goddess, but eventually turned into those who once oppressed her... sigh anyway

onto some ideas/possibilities:

ghil served andruil, and made monsters for her to hunt. the connection to dirthamen isn't clear.

ghil served dirthamen freely, and he supported her research. after she ascended, she turned on him for unknown reasons. her relationship with andruil began after ascension.

ghil served dirthamen, and he supported her research, but she did technically "belong" to him. after she ascended, she turned on him, perhaps as revenge? her relationship with andruil began after ascension.

ghil wasn't aligned with any god, and could have just been a noble with her own funds. she could have interacted with and formed relationships with multiple gods, as she wasn't bound to a single one.

i personally think number 2 is the most probable here. going from dirthamen -> andruil rather than andruil -> dirthamen makes more sense, considering that the ghilandruil mural from the missing was clearly drawn after ghil's ascension (since she has her headpiece) and also, from what we've seen of ghil so far, she seems very proud of her creations. why would she want them hunted? again, the bargain she made was to destroy her creations in exchange for godhood. it was a sacrifice.

finally, considering her resources it makes more sense for ghil to have been a servant rather than a slave. what remains now is the question: why would she have turned on dirthamen?

a reason for betrayal

between the missing mosaics in his temple, ghil convincing his followers to commit crimes, and the stabbed fade statue, you can probably tell by now that something's different about dirthamen. remember the fen'harel statue looking over the citadel? there are more potential connections to solas if you look close enough:

fen'harel statues in the lost temple:

dirthamen's mosaics in the elven mountain ruins (note: these are the only evanuris mosaics in the entire area, not counting the forgotten sanctuary):

mosaics in the forgotten sanctuary (on each wall: dirthamen - mythal - fen'harel - falon'din - dirthamen)

symbol of the two ravens in the forgotten sanctuary armoury

so what does this all mean? well u/eravas on reddit had a theory that these are hints that dirthamen could have potentially been helping solas and mythal with the rebellion. remember how morrigan said it was weird the temple of mythal had fen'harel statues? and the mountain ruins were a sanctuary, so why keep the mosaics? (there are also a few other hints eravas mentioned that i missed, but these are the most important!)

and remember how i said that attackers on the lost temple of dirthamen could have torn his mosaics down specifically and left the others? and i came to the conclusion that they must have had a grudge against dirthamen specifically. well, there is some other defaced imagery... in the form of these decapitated statues of mythal:

so, why would dirthamen have helped solas? i don't know, but we don't really have explicit answers as to why mythal helped him either. and then, why did solas trap dirthamen along with the others? well, there is one last thing...

the statue in the fade: the final piece of the puzzle

and now, the part that lives in my head rent free!

if kieran exists in your worldstate, then during the quest The Final Piece you will find him and flemeth in the fade, and above their meeting ground there is a massive statue of dirthamen with a blade in his back, with blood pouring out of the wound and his eyes:

alright so to be clear this takes place in the raw fade, not the "dreaming" fade; we know the fade usually reflects the dreamer, but know less about the "raw fade" when we aren't dreaming. it's complicated, but from the random statues and scattered memories we see in the fade during here lies the abyss, it's safe to assume that some of the aspects of the dreaming fade (such as it being ever-shifting and a reflection of the waking world) are also present in the raw fade. therefore, i'm guessing that this statue's presence here is mirroring something that happened in the waking world... so what is it?

i think there are two possibilites:

someone betrayed dirthamen, and this captures the moment of his betrayal

dirthamen betrayed mythal, and this statue is a "reflection" of this

while 1 is more of a direct mirror and is more likely, we don't have that much info about who could have done that to him. yeah, ghil maybe, but she was only stirring the pot and this seems more... severe. 2 is what i believe due to flemeth's deliberate choice to use that specific area as a meeting spot. also, if one of the other evanuris had betrayed dirthamen, well solas said they fought among each other all the time, so that would seem pretty insignificant. on the other hand... mythal was betrayed by what we assume was all of the other seven evanuris. why portray dirthamen specifically?

the betrayal of mythal

so now we have the idea of dirthamen helping solas and mythal, and we have the fact that solas trapped all seven remaining evanuris for their murder of mythal, which includes dirthamen.

that is the missing piece: dirthamen helped murder mythal, despite helping her and solas, and presumably sharing their goals. why? let me go back to something i said about the sinner codex...

this reads as an attempt to sow discord, either between dirthamen's worshippers or to paint them as troublesome and dirthamen himself as irresponsible in the eyes of the other evanuris

consider that ghilan'nain and dirthamen were close, and she was this young elf who had just gotten into the ranks of the gods, probably trying her hardest to fit in. consider that perhaps she stumbled upon her friend's - and now fellow god's - involvement in a rebellion against the gods. but she was the youngest of them. she could not just go to the other evanuris and say, "dirthamen is plotting against us", because she was so new to their group that they would just simply not believe her word over mythal and dirthamen's. so what else could she do to discredit his word? cause discord among his followers, maybe? to paint him as irresponsible, untrustworthy, and suspicious?

and maybe she succeeded. maybe the evanuris found out about the rebellion, and mythal and dirthamen's roles, or perhaps only mythal's? either way, it all ended up with them asking dirthamen to join them in their plot to murder mythal - if his involvement was revealed, perhaps he was threatened or promised to be spared if he helped. either way, the question is: why did he agree? did he change his mind and side with the evanuris? or did he do it for preservation reasons? to save himself, and all he'd acquired? honestly, i cannot imagine a god who gathers secrets and knowledge agreeing to throw away his life like that.

so there you have it. i think dirthamen betrayed mythal, and solas, with a much deeper cut than any of the other evanuris could have possibly delivered. and for that he was trapped alongside them, paying the price for his treachery.

the full narrative, summarised

to break down all my theorycrafting and brainstorming in a short summary:

dirthamen was ghilan'nain's patron, until she ascended to godhood and discovered his involvement in solas and mythal's rebellion. unable to simply tell the other gods, ghilan'nain began to sow discord in attempt to discredit dirthamen's word. when the evanuris eventually turned against mythal, dirthamen went along with them in order to preserve himself, and ultimately paid the price by being trapped in the fade alongside the others. the end!

—————

final note: companion parallels

i first touched on this briefly here but i have a small theory that part of bellara and davrin's characters will be to sort of act as parallels to the gods whose vallaslin they have. what i found curious about veilguard's early marketing was the focus on companions and how important they will be, and i specifically noted the multiple times the writers said that the companions were all deeply thought through and are significant to the plot. it's clear the companions were thoughtfully crafted in order to provide different perspectives and experiences, which is why i found it incredibly interesting that they decided on two dalish elf companions — in a game about elven gods terrorising the world, you'd think that one dalish elf and one city elf could provide more differing perspectives, but bioware specifically picked two dalish elves instead. it implies that, despite their similar upbringings, bellara and davrin may have completely differing opinions about the current threat, or about solas, or something else we don't know about yet. it was clearly a very deliberate decision, and with how important the vallaslin is to dalish elves, it has to mean something.

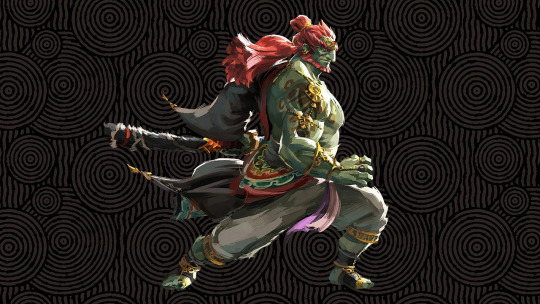

bellara is an elven lore nerd who loves exploring ancient ruins and uncovering secrets. dirthamen was an easy guess, and the design - although new and very unique - matched up to patterns on his inquisition vallaslin. as of sept 19, it has been confirmed her vallaslin is indeed dirthamen's.

davrin is a grey warden and a monster hunter. his vallaslin design was harder to figure out, at first i thought it was june's but the lines and layout really remind me more of ghilan'nain's.

the parallels are pretty clear. bellara is more similar to dirthamen, being interested in secrets and knowledge and such. whereas davrin and ghilan'nain are at odds: davrin being a grey warden monster hunter, ghil being a blighted monster maker. one similarity, and one anithesis, which makes them unique to each other. and for all the gods bioware could have picked, to choose dirthamen and ghilan'nain... well, ghil is of course one of our antagonists, but dirthamen has no direct connection to the plot...

........ or maybe he does? we'll have to find out :)

#pre-veilguard posts archive#dragon age#dragon age the veilguard#dragon age lore#dirthamen#ghilan'nain#mythal#solas#evanuris#*emerges from a cave covered in blood with 10 pages of deranged rambling* hey guys look at my fun little theory#i finally finished it after like. a month.#it's been on my mind for... so long...#but yeah. the only thing that is kind of a plot hole here is why dirthamen would help solas#but i can't really explain why mythal would either#so ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Manu Temple#Manali Spirituality#Himalayan Heritage#Religious Sanctuary#Ancient Architecture#Hindu Mythology#Beas River Views#Cultural Exploration#Wood Carvings#Sage Manu#Sacred Destination

0 notes

Text

#Panchvaktra Temple#Mandi#Himachal Pradesh#ShortsVideo#Travel India#Explore Himachal#Spiritual Journey#Sacred Destinations#Ancient Temples#Shorts Adventure#Incredible India#Temple Architecture#Divine Aura#Cultural Heritage#Spiritual Retreat#Shorts Experience#Mystical Places#Himalayan Temples#Explore With Me#Shorts Content#Travel Inspiration#Devotion#Tranquil Spaces

0 notes

Text

CHAPTER NINE | TSOFAS.

pairing: azriel x reader.

word count: 4,838.

author’s note: eris, my beloved. honestly he just shows up to serve cunt and wreak havoc and that's perfectly valid. I have a lot of things planned for our favorite redhead in this story, so stay tuned.

♫ arsonist's lullabye - hozier. nav. series. moodboard.

A misty fog settled over Thorne Manor, shrouding the pale yellow sun and providing the perfect cover as you slipped through the outskirts of the estate. The eerie silence confirmed that the rest of the household was still asleep. Dawn would not break for another hour, which gave you plenty of time to meander through the Godswood without interference.

With bated breath, you passed through the white weirwood trees, their crimson leaves swaying gently in the autumn breeze. Growing up, the Godswood had always been your favorite place to explore despite the fact that your cousins refused to go near it. Like the rest of your household, Eris and Lucien had dubbed the pale forest eerie and unsettling. The silence here was a living thing, twisting and curling like the ancient roots that choked the forest floor, but you had never found it creepy. In a way, it was oddly comforting.

No matter the chaos and turmoil happening around you, the Godswood would always be the same. Silent. Sacred. Still. A place untouched by change.

There was something reassuring about that.

You stared down at the parchment in your hand. A twisted tree with a crone’s face stared back at you. Black sap stained the pale wood, dripping like tears of blood against the sinister weirwood. Your aunt’s illustration had been simple, but you would have recognized the tree anywhere. The drawing curled into itself, devoured by the small flame in your hand. The Lady of the Autumn Court had undoubtedly put herself in much danger when she slipped the note into your hand last night, so you did your due diligence and erased any trace of evidence.

A shiver snaked up your spine as you marched up to the weeping weirwood. The pale wood appraised you with hollow eyes, the bark streaked with obsidian. It was the only tree in the Godwood that you hadn’t dared climb as a child. To do so would’ve felt sacrilegious. The tree was older than the Autumn Court itself. Its ghost white branches speared the sky and wrapped its spindly claws around the forest like an ancient sentry.

As soon as you stepped beneath its shade, the crone’s face contorted. Its expression of perpetual mourning transformed into a familiar insignia. A ring of roses with spiked thorns — your family crest. You brushed your thumb against it, jerking as it came alive at your touch. The shimmer of magic licked at your skin with a beckoning caress.

Carefully, you unsheathed the dagger strapped to your thigh and sliced through the flesh of your palm. Bracing yourself, you lifted your bloody hand in offering. The bark gave way and you watched in amazement as the tree split in half. This was powerful magic. The likes of which you hadn’t seen in a very long time.

You looked over your shoulder with your dagger clutched close, confirming that nothing was amiss in the Godswood before stepping through the makeshift opening. Beyond the weirwood, a stone statue stood alone in a field of red roses. Time seemed to still as you came face to face with the likeness of your mother.

The whisper of the wind blew around you, whipping your hair in your face as unshed tears pricked at your eyes. You reached for the bloodstone gem around your neck out of habit, allowing yourself a small comfort as you forced yourself to look up.

In the Autumn Court, you honored the dead with fire. A funeral pyre would be set adrift in the great lake, followed by a single arrow that would engulf the body in flames. When you fled, Beron had denied your mother of this honor. She was cremated in haste at the High Priestess’s temple, you later learned. As it were, this statue was all you had left of her.

The stone was serious and unyielding in a way that your mother had never been in life. The granite seemed to miss all of her best features—her unruly auburn hair, her warm, dimpled smile, and even her eyes, once as gold as the changing leaves of this court, were cold and bleak.

“Mother,” you croaked.

You braced yourself for the onslaught of tears and anguish and grief, but it never came. Instead, you felt nothing. Like a well that had been hollowed out. Devoid of feeling. Just an endless, gaping pit whose emptiness threatened to swallow you whole.

For some reason, it felt worse than completely falling apart.

There were so many things you wanted to say, but it was pointless. You were here and she was not. She perished while you lived, killing and killing because it was all you knew. It was what Beron created you to be. A monster.

Your mother would be proud.

Your aunt was wrong. There was nothing to be proud about what you had become. You were violence entombed within skin and bones. A weapon to be wielded, wildfire waiting to be unleashed upon this realm. Your mother would have mourned the loss of her daughter.

A wave of shame flooded through you. Suddenly, you couldn’t bear to be in this place, standing before this statue. The statue wasn’t your mother. She would never laugh or smile or cry again. All because you failed to save her.

Some say that people process grief in five stages — denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Perhaps this statue reflected your aunt’s acceptance of the loss of her sister. Maybe she thought this would bring you towards closure too. That fifth and final step.

But in order to do that, you would have had to cross the threshold of the second stage. There would be no closure for you, no acceptance. Only anger. Anger towards yourself, anger towards Beron, anger towards the world. Rage, wrath, fury. An all-consuming force that you clung onto because you didn’t know who you were without it.

It was easier to let yourself burn.

You turned away, trampling roses beneath your feet as you stalked back into the Godswood. The weirwood fused together behind you and returned to normal, making the last few minutes seem like nothing but a fever dream.

The only evidence that any of it had occurred was the dried blood on your half healed palm. You made your way through the clearing with a frown and walked briskly towards the manor. As dawn broke over the horizon, the Godswood began to come alive.

The chirp of birds, the rustling of leaves, the muffled footsteps of woodland creatures. Except, no animals ever roamed the Godswood.

You whirled around, disturbing the jewel toned leaves as you drove your dagger upwards. A hand clamped around your right wrist and caught the other wrist mid-swing, inches away from a familiar face.

“We have to stop meeting like this,” said the shadowsinger.

Incensed, you twisted out of his grip and scowled. “One of these days, I won’t miss.”

Azriel watched as you lowered your dagger, eyeing him with disdain as you sheathed it in its rightful place. “What are you even doing out here?”

“I should be asking you the same thing,” Azriel countered. “Why the hell are you roaming the woods alone? Did your aunt ask you to meet her in that note?”

You stiffened. So he had seen.

“Keep your voice down,” you hissed as the manor came into view. “You never know who could be listening.”

As daylight painted the grounds golden, Azriel fell into step beside you like a dark gloom. The shadow of his wings darkened the path, shimmers of red and gold catching the morning sun while he followed you into the rose garden. You briefly nodded to the staff tending to the flowers before hauling the shadowsinger into an empty shed.

“I would appreciate it if you stopped stalking me in my own home.”

Azriel frowned. “I wouldn’t have to stalk you if you stopped keeping secrets.”

“The business between me and my aunt has nothing to do with this mission.”

“Why do you get to decide what does and does not pertain to this mission?”

You crossed your arms. “Because, I’m the one who was raised in this court. I’m the one who knows these grounds like the back of my hand. I’m the one who knows how to play the game.”

The shadowsinger frowned. “That’s precisely the point. Familiarity can cloud judgment, it can cause you to miss things.” His voice dropped to a whisper. “I don’t know what Beron said to you, but I could only assume that he threatened you in some way. Threatened the twins.”

Your fists curled at your side. “Beron doesn’t threaten. He promises. He will hurt the twins. If not to punish me, then for his own enjoyment.”

“That’s the thing, I don’t think he will. Or at least, he won’t for the time being.” You stared as his shadows swarmed around him, one curling against his ear to whisper something. “When Eris greeted us at the border, he said something that struck me as odd. The High Lord wanted to keep the twins in the dungeon, but your cousin said Beron changed his mind. I don’t think that’s a coincidence.”

You could see the gears in his mind turning. “No one in the court of foxes shows kindness without ulterior motives,” he said, echoing your words from last night. “You told Rhys that the High Priestess would never grant Beron the power to wield the scepter, so he took her daughters. We attributed that to his cruelty, but what if there is another purpose to keeping them in the Forest House?”

“He means to keep them close,” you mused, working through the bits and pieces. “For when he finds the scepter. If Alyanna won’t cooperate, then he means to find another way around the constraints of the magic.” Horror sluiced through you like a knife. “Somehow, the twins are connected.”

Azriel nodded gravely. “We just need to figure out how before Beron does.” His mouth formed into a thin line. “In order to do that, we have to start working together. I know we haven’t always been on the best terms —”

You scoffed. “That’s a diplomatic way to put it.”

A glare that would’ve withered the roses in the garden cut to you. “But, we have to put our differences aside. We never would have pieced this together if we hadn’t talked this through. You can’t keep withholding pieces and expect the puzzle to come together on its own.”

As much as you hated to admit it, Azriel had a point. He was clearly more perceptive than you’d given him credit for. Perhaps you could put your pride aside for the sake of this mission. “Are you extending an olive branch, shadowsinger?”

“I suppose I am,” he mused. “As long as you don’t try to stab me with it.”

There were many reasons why you were resistant to teaming up with the shadowsinger. One, Azriel vexed you like no other. Two, you were used to working alone. And three, that expression on his face. That puzzled look, like he was trying to siphon the thoughts from your mind.

You were convinced that this alliance would end in flames, but what choice did you have?

You sighed, throwing your hands up in surrender. “Fine, we can call a temporary truce. For now.” You narrowed your eyes at him. “But don’t expect us to hold hands and sing kumbaya around a fire.”

Azriel ignored the sarcastic remark and zeroed in on your palm. “You’re hurt.”

You shrugged, tucking your hand into the pockets of your dress. “It’s just a cut.”

Azriel reached for you and you instinctively took a step backward. “It needs to be sterilized and bandaged.”

“It’s fine,” you huffed. “It’s already almost healed.”

“A cut that deep will scar if left unattended.” The shadowsinger said matter-of-factly as he held out his hand. You stared at him. He stared back at you. It was like a staring contest with a rock and a hard place. Neither one of you wanted to budge. Azriel sighed as if the entire exchange exasperated him. “Plus, you’re getting blood all over my mother’s ring.”

Your focus instantly honed in on the delicate sapphire ring resting on your finger. Indeed, crimson had splattered on the silver band and dried on the luminous stone. “I — I didn’t realize —”

“It’s fine, Thorne.” Azriel said dismissively as he took your left hand. You suppressed the urge to shiver as his rough, calloused fingers slid across your palm. “Just let me clean you up.”

Finally, you relented. After all, it was the least you could do after bloodying his mother’s ring. His mother’s ring. Why in the hell would he even allow you to wear it in the first place?

The shadowsinger worked quietly, conjuring a water basin, a cloth, and a sterilizing potion from whatever pockets of shadows he had access to. You watched as he cleaned the wound, his hands gentle and warm while he dabbed at your palm with cloth. Shadows swirled through your wrists, assessing the damage.

“I’m sorry for getting blood on your mother’s ring,” you said in a rush. The apology felt strange in your mouth. “I’ll be more careful from now on.”

“Good,” he said as he polished the sapphire stone. “I wouldn’t want to have to explain to Rhys how his assassin was felled by a simple cut.”

The corner of your mouth quirked up at that. “I would think you’d be glad to eliminate the competition.”

“We’re allies now, remember?” The shadowsinger said. “Besides, there would be way too much paperwork to fill out if something did happen to you.”

You snorted at that. A stretch of silence descended as Azriel dunked your hand into the basin, muddying the water with crimson. The blood came off easily enough. The two of you looked down at the ring. Clean and sparkling on your finger. The shadowsinger brushed his thumb over the band, causing goosebumps to erupt all over your arms in his wake.

“Your mother,” you croaked, the raspiness of your voice breaking through the silence. “What is she like?”

The shadowsinger kept his eyes downcast as he rubbed salve onto your wound. “Warm. Kind. She always sees the best in people, even when they don't deserve it.” His voice lowered. “Especially when they don’t deserve it.”

You swallowed thickly. “You said Enid reminded you of her.”

Azriel nodded absentmindedly, his eyes glazed as though lost in thought. “She never wanted to send me to Windhaven, but then my stepbrothers —” he glanced briefly at his scarred hands, his expression darkening. You knew the story, understood the stoic mask that came over his features as he cleared his throat. “When I met Rhys and Cassian, she was relieved. It made staying in that wretched place bearable. I climbed Mount Ramiel because of her. I didn’t care about the title, but seeing that proud look on her face — it’s the same one Enid had when she spoke of her son. It makes everything I do worth it.”

The words had a sobering effect. It felt strangely intimate, like you were seeing a layer of Azriel that you weren’t meant to peel back. But the more you learned, the more you hungered. You had always been greedy that way. Innately curious, always wanting.

“She doesn’t live in Velaris.”

The details were murky, but you were astute enough to notice that Azriel took leave every once in a while to visit the countryside. Rhys had mentioned that he owned an estate deep in the mountains; Rosehall, if you remembered correctly.

Azriel nodded in confirmation. “She prefers the country. It’s quiet out in the mountains, simple.”

Questions swarmed your thoughts like hornets batting restlessly inside their nest, but no words came out of your mouth. It didn’t seem right to hound him about his mother. She clearly valued her privacy and you wanted to respect that. Still, there was one thing niggling away at you as Azriel finished wrapping the bandage around your palm.

“Would she mind that I’m wearing her ring?”

His hand hovered above yours, contemplating. After a brief pause, Azriel shook his head. “No,” he said with certainty. “I don’t think she would.”

The sunlight streamed through the windows as Azriel looked up at you. It kissed his profile, illuminating his features in a new light. For instance, you never noticed the hidden dimple on his right cheek or the constellation of freckles dusted along the bridge of his nose or the fact that all this time, you thought that his eyes were hazel, a mixture of brown and green, when really, there were flecks of gold in them that could only be seen from up close.

“Don’t get me wrong, Cassian’s hot.” Serena’s voice echoed in your head. “But Azriel’s just pretty, isn’t he?”

You had scrunched your nose in disgust back then. Teenagers, pre-pubescent and hormonal, ogling Rhysand’s closest friends as they sparred in the training pit. The Illyrian warriors were a blur of sweat slicked golden brown skin and ridiculously toned physiques, lean lines and bulging muscles with six-packs and all. The silly little crush you had on Cassian back then had clouded everything else, but now that Azriel was a hair's breadth away, you thought that maybe there was some merit to Serena’s words.

Fortunately for you, the thought didn’t have time to fully develop thanks to the sudden creaking of the shed’s old door. You startled, drawing your hand back from Azriel’s grip as Alinta came into view.

The old witch had a cheshire’s grin on her face as her gaze danced between you and the shadowsinger. “I hate to interrupt your little early morning rendezvous, but breakfast is ready.”

Her smile smoothed into something more serious as she held your gaze. “And we have a visitor.”