#/but I can also see where the seams of it being rebuilt so many times as well as the layoffs and budgets

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Sometimes I think about how Dragon Age's entire existence seems to have been an uphill battle against EA since it got turned into a series after Origins (which iirc was basically done by the time EA bought the studio) and I am both so thankful for the work the devs put into it to make each entry in the series work as well as they could under whatever circumstances they had but also bitter at how constrained they were/are and how much they get forced to sacrifice for trends like multiplayer. It feels like a curse to be such a long time Bioware fan and hearing certain criticisms where you're like "no wait, they didn't want it to be like that, here's what happened behind the scenes that made it have to be that way and how it was the best scenario they were able to carve out, but yes I also understand that it being the final result gives unfortunate implications" and I think about what being on the developer side of things must be like

#jaderaven post#jaderaven talks dragon age#/turning off reblogs bc this is more a vent post than an analysis#/I've been playing bioware games since I was 12 with kotor and started following dev stuff with dao#/it's been... something watching what happened since the ea buyout in real time#/ALSO I feel like I should say that I genuinely LOVE veilguard!!!#/I love the gameplay and visuals and sound design and music and characters and stories overall#/but I can also see where the seams of it being rebuilt so many times as well as the layoffs and budgets#/also not saying the devs are perfect flawless beings asjkdjshds we're all human#/edit to remove the readmore bc I wanted to yell a little louder after all

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘We can estimate death numbers and take into consideration that the journalists who tallied them are also ascended but how do you count a death? A human life as a unit of one? How is 200,000 a plausible numerical value when the suffering rebounds into infinity, when the bombs are so many that the simultaneous snuffing out of breath is the last stop in an entire bloodline… tens of generations stretching back to the beginning of time abruptly cut, forever, by a depraved military state less than a century old.

If I were to die for the principles of the Thawabet, in honor of the poets & writers ascended over decades, in honor of dead friends & comrades, in honor of likely the most brilliant minds of the Universe who died in tents without ever being recognized for their brilliance, I would only feel ashamed over the causing of my mother’s tears. At the same time I love my friends on Earth with a ferocity & a tenderness and I’m afraid to die. I’m also afraid to keep facing the things I see in passivity. I’m also afraid to keep bursting at the seams with rage and indignation with nowhere to put it. I’m also afraid of the blisters and bruises and sprains and decimated eyes & zip tie marks still not feeling like enough. Still not feeling adequate in turning the pain inside out, turning the pain towards skin & bone to alleviate the suffering inside.

La ilaha il Allah….. And the martyrs are adored by Allah and provided for by Allah.. they are bathed in sweetness and tenderness inconceivable to anyone still sticking around, and still it is inadequate compensation for the flames they saw in final moments.

I want peace for all of us. All of us who have fought. We deserve a lifetime of peace. Palestine deserves glory, and rebuilt cities, rejuvenated orchards, and children born safe.

//

Another dove has died today.

Many doves have died today. I want to hug my friends.

I so desperately am straining to keep believing, as so many others are, that the ugliest moments of Empire are immediately preceding its collapse. The most abhorrent manifestations are one last croak before a long, long recovery of The People.

I used to want to hurt myself. Now I want to die for Palestine or not at all, ever.

If I reach the end callouses of these fingertips out far enough, I can graze the veil to the other side, where none of this was in vain. If I strain hard enough to tremble, I can feel you brushing me, intifada— warm, fed, and clothed.’

0 notes

Text

ok this is both queued bc i’m at work rn and totally just lifted directly from my app but your girls been a busy bean recently ok. hopefully this helps give a lil more insight into this nugget!!

❝ everything we ever were was alight with gold. / and when they asked us what love was we answered, / soft and bright, darling. / soft and bright. ❞ Lysander Scamander, Keiynan Lonsdale, Sixteen, Sixth Year, Ravenclaw, Demiboy, Half-Blood, He/Him

family/home life.

- I dare you to tell me that Luna and Rolf were anything other than the most loving and kind parents you have ever met. Because they are, and life with the Scamander’s is nothing short of Lysander’s paradise. It’s the most loving tight knit family you could possibly dream of

- While his childhood was maybe odd at times, Lysander has never had to wonder what it’s like to be alone or unwanted, what it’s like to have to hide yourself, what it’s like not to have your best friends as your parents. Because while occasionally quirky, Luna has lived a life of the utmost acceptance and openness and along with Rolf she made sure to foster that kind of environment for her children. The twins were supported and even encouraged to explore their interests and passions freely and to unapologetically be the most true versions of themselves

- I’m sure if you asked Lysander to paint his childhood a colour, then it would no doubt be yellow. The scamander home (the lovegoods old tower on the hill, since rebuilt) always had a sense of vibrancy to it, a sense of excitement – it was never a dull moment growing up in the Scamander household (or castle as he would call it in his early years). If he wasn’t running around the house chasing wrackspurts with Lorcan or finger painting a new masterpiece with Luna, then he was out marching through the grassy backyard on some epic quest to find a new undiscovered magical creature with Rolf. The world was just endlessly exciting, every new day a new opportunity and a new adventure.

- And what’s better than having a twin to share adventures with? the twins were basically attached at the hip growing up. Where there was one twin inevitably the other was stumbling through the door right after. Lysander never had to get used to the feeling of being alone because he never was, really. It was always his mom or his dad or his twin or some combination of the three. In his mind a twin is a guaranteed friend, really. A partner to face the world with. I think this is part of what really fostered his love and appreciation for the friendships he would make later in life, he was taught early on to value that kind of support and companionship. Thrived with it even.

- True free spirits, Luna and Rolf never shied from showing their children what the wide world had to offer – they were magizoologists, after all. Before both sons were obligated to begin their studies at hogwarts the family did a fair amount of travelling to all corners of the world, meeting all manner of people and creatures. Lysander had the opportunity to really witness the beauty of the world first hand.

- I can imagine things were never really serious in the Scamander house. I think Luna and Rolf taught their sons serious lessons of course – things like tolerance, and humility, and generosity – but never in an overly serious way if that makes sense. Lessons were delivered with smiles and laughter and fun; always a lighthearted and gentle atmosphere. His parents were definitely believers in the concept of “you get more flies with honey than with vinegar” concept; gentle encouragement over strict reprimands.

- That’s the thing I most associate with the family home honestly: warmth. A relaxed, fun, happy place free of judgement and expectations. And that’s something that’s really stuck with Lysander even as he grows older now. Home is something to be cherished above all else, a place that will always accept you and people that will always love you. He misses his parents desperately when he’s away at school and always makes sure to write them as frequently as possible (and doesn’t even mind when his mom sends him weird packages back)

- That’s not to say his childhood wasn’t without its quirks though, things that were normal to Lysander because he didn’t know any different but no doubt confused others outside the family. Weird family traditions or habits - things like making sure you had your butter beer corks to ward away the nargles before you left the house. The home is probably constantly in a cluttered state, things everywhere with no rhyme or reason but which Luna insists are exactly where they were need to be. Why was there a sneaker tied to the chandelier? Nobody knows and nobody bothers to ask anymore. The walls are adorned with murals and the style of decor surely doesn’t match, changing from room to room in a kaleidoscope of colour and pattern. Trinkets and little souvenirs from all over the world have crept their way onto every surface and space. While it probably looks like a hippies art studio exploded all over it tbh, the home positively oozes comfort and familiarity and positivity.

personality

- Lysander is honestly a direct reflection of the environment he grew up in – open, honest, and with a heart that’s just bursting at the seams it’s so full of love. It’s not hard to tell he’s his mother's son. He’s oddly intuitive, always seeming to be in tune with the emotional mood of the room – though sometimes he doesn’t pick up on other more obvious cues. It’s rare to find someone who can say they’re truly happy with who they are but Lysander wouldn’t even blink before agreeing

- While others maybe would have gotten sick of their mom’s “weird quirks” or outgrown such a positive (and some may call naïve) outlook on life, Lysander’s still nothing but fond of her and his eyes have never lost that youthful sparkle. Looking on the bright side and keeping a little imagination in your life is just makes experiences so much more enjoyable in his opinion

- He never fails to find the joy in the little things and turn around a bad situation and honestly he’s just a sweet ray of sunshine okay

- if you’re ever having a super bad day or just need someone to sit and listen Lysander’s your guy – he’s always ready to be there to support a friend and offer a kind smile. That’s his main goal in life honestly – to leave every place and everyone a little better, a little happier, then he found them

- he’s a true romantic at heart ngl like he’s all over the grand gestures and gooey relationships no matter how unrealistic it may be. he just loves love and everything it relates to. He could get his heart broken over and over and would still be enamoured with the concept of true love

- He’s a very creative person and this definitely reflects in his style - it’s daring and bold and maybe even a little out there at times. Don’t be surprised to see him rocking the bottlecork earrings with pride or have his hair a fun new colour every week

- on the flip side though, he can tend towards being unrealistic at times – looking at the world through rose coloured glasses. He’s not exactly the grounded and practical type and while it can be good to look on the bright side, sometimes it’s just not feasible. 100% a heart over head kind of person which can get him into trouble

- He’s also a little too trusting at times, wants so badly to give the benefit of the doubt and focus on the good in people that it ends in him being taken advantage of. He’ll give and he’ll give and he’ll give until there’s just nothing left for himself which can leave him emotionally drained if he’s not careful

- As a whole he just relies on his emotions too much – for better or for worse. It’s not that he can’t think of a more logical path of reasoning (and I mean he is a ravenclaw) it’s just that he tends to get carried away. So while he greatly loves, he can also greatly hate haha – the boy knows how to hold a grudge.

- That doesn’t mean he’s a total pushover though – quite the opposite. He has a pretty strong moral compass and inner resilience that he’s not willing to compromise on. Like sure, on little things it’s often pretty easy to get him to cave; he just wants to see you happy. But when it comes to his convictions? Nope. You can bet your ass if he sees you bullying someone he’s about to storm over and pull out some witty and terrifying smack down that you didn’t even see coming. Which I think is an important hidden part of him – he kind of has this secret hidden badass within him. He’s not some naïve happy go lucky little idiot, his positivity and his demeanor is a choice. He chooses how to interact with the world and sure in this case it’s in a gentle and friendly way but don’t you dare think that makes him weak.

- I guess what I’m trying to convey is he’s not a fluffy little weak head in the clouds marshmallow, he’s smart and strong and gentle and kind all at the same time. Just because someone approaches the world in a position of love and positivity doesn’t mean they necessarily timid or naïve.

- I think very much like Luna he has a hidden intelligence to him and is actually someone who’s quite sharp. It just tends to get lost under all the other stuff unless you really look for it. You don’t tend to think that the one with stars in their eyes could have so many gears turning underneath. In subjects he’s interested in he actually excels greatly and is very capable. In courses he doesn’t like or doesn’t feel inspired by? ...not so much

-How he labels and presents himself has never really been something Lysander has cared much about, honestly. His views on such abstract concepts as sexuality and gender and where he falls in that spectrum are very loose and if he had the choice it would never even need to be addressed. But he’d kissed a cute Gryffindor boy for the first time in fourth year, closely followed by a sweet Hufflepuff girl a few weeks later and apparently that confused people. He pierced his ears and wore glitter eyeliner and painted his nails and suddenly people were asking him why. Why? He just believes in just being the truest form of himself, he would tell them time and time again, whatever that happens to be on that day. Believes in expressing himself however that may look. Why does he have to be one thing or the other? He’s going to dress and act however he wants to and love whoever he wants to with reckless abandon. Love is love to him. It’s to be shared and celebrated in all it’s different forms. There’s been labels he’s felt some semblance of kinship with in the passing years - panexual, genderqueer, polyamerous - but even those never really felt right and even a little restrictive. The only thing Lysander wants to be is himself.

+ Positive, compassionate, friendly, gentle, intuitive, creative, honest, supportive, accepting, loyal, witty, curious, approachable, imaginative, kind, adventurous, genuine

– Overemotional, idealistic, too trusting, stubborn, melodramatic, indecisive, clumsy, nosy, trouble saying no, absent minded, indulgent, impulsive

Patronus: Otter

Wand: 13 ¾, rowan wood and unicorn hair, slightly springy

Zodiac: Cancer Sun, Libra Moon, Libra Ascending

Myers-Briggs: ENFP - The Campaigner

Enneagram: Type 2 - The Helper

Temperament: Sanguine

#holocene intro#is i think what the tag was?#shoot#i'll fix it when i get home if I have to#( about )#q

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Answers To Questions

Annnnnnd the third fic in the Wanna Be Missed series! Aka a continuation of Used To It! Back to sexy sexy basics.

Also a heads up that if you haven’t figured it out yet, this series is just me letting myself writing endless dialogue. It’s a power I should have never given myself.

Franchise: TFIDW/MTMTE

Ship: Ratchet/Rodimus, discussion of past Ratchet/Optimus

Rating/warnings: E for sticky interfacing, casual interfacing, friends with benefits, talking about past interfacing, and just a hell of a lot of talking when they should be focused on fragging. And as always, Sexy Prime Powers

Summary:

“Is Optimus a better frag than me?”

You can find the rest of the Wanna Be Missed series on AO3 or each individual fic on tumblr below:

| Used To It | Hashing It Out | Answers To Questions |

“Ratchet?”

One of Ratchet’s optics onlined to peer at where Rodimus was curled up against his side, vents still open but cooling fans only lazily whirling to whisk away the last of his body heat. The servo stroking between the Prime’s spoilers kept the same steading rhythm.

“Something on your processor?”

Rodimus lightly sucked on his bottom lip before, predictably, shaking his helm. “Nah, it’s nothing.”

Ratchet’s optic offlined again as he sighed. His servo continued to stroke comfortingly.

“It’s clearly something since this is the third time tonight you’ve done this.”

With a noncommittal grunt, Rodimus shifted and rolled out of Ratchet’s hold, insisting, “It’s dumb so don’t worry about it, ok? We should recharge anyway--”

“Oh no you don’t,” Ratchet interrupted as he reached out with his free servo to catch Rodimus’s shoulder, tugging it back towards him. Rodimus squirmed, putting up a half-afted attempt to escape, but by the time Ratchet had him on his back and trapped under the medic’s bulk, Rodimus relaxed.

“Come on, Ratch, that’s not fair.” Rodimus’s lips curled into a sly grin as his knee came up to rasp against Ratchet’s crotch. “You know I can’t say no to you when you have me pinned down.”

“Nice try, but I’ve fragged you enough times tonight that that won’t distract me,” Ratchet insisted. The sultry façade fell away with a huff of Rodimus’s vents.

“Now that’s definitely not fair.”

“I don’t play fair. Now come on, spit it out.”

Rodimus’s spoilers gave a brief nervous flutter against the berth as he chewed on his bottom lip for a moment.

“Ok, fine, but you can’t judge me for it since you’re the one insisting I say it outloud.”

Ratchet gave him a disbelieving look in response, and with an exasperated sigh Rodimus looked up at the ceiling as he steeled himself like a mech facing his impending doom.

“Is Optimus a better frag than me?”

Ratchet blinked, his audials resetting, waiting for the punchline. But none came as Rodimus gave another half-sparked squirm.

“Seriously?”

“I told you it was dumb,” Rodimus muttered, optics only briefly flitting to Ratchet’s face before they moved away.

“But it bothers you enough that you kept almost asking,” Ratchet pointed out, almost more to himself as his processor got to work trying to piece out the bewildering puzzle in front of him. “You looking for a ranked list, kid?”

Rodimus rolled his optics, as if it was Ratchet being the ridiculous one here, and said, “No, it’s not—well, yes, that would be kind of hilarious, but no. I know that the whole sexy Prime power thing would muddle the criteria involved.”

That got an amused chuckle out of Ratchet.

“Primus forbid a ranked list of mechs I’ve fragged have unfair criteria,” Ratchet teased, but he kept it soft since Rodimus’s frame still held tension. He couldn’t help shifting his weight to one arm so he could reach up to run his knuckles along Rodimus’s cheek, bringing the Prime’s gaze back to him. “But that’s not what this is about.”

Rodimus frowned and, slowly, shook his helm.

“Guess not, no.”

It seemed so wrong to see the usually boisterous and confident captain look so cowed, so—so unsure. Self-conscious even. Self-doubting.

It only took a moment to imagine sharing a title with Optimus to guess where that might be coming from.

Ratchet’s spark ached in a way he couldn’t rightly label as being due to the Prime beneath him, or due to the Rodimus beneath him.

After a moment, Ratchet sighed as he pushed up onto his knees where he straddled Rodimus’s waist and sat back on his heels, watching the way that Rodimus stared up at him. “Listen,” Ratchet started, his digits smoothing across Rodimus’s abdomen, “if I could just give you a straight forward answer, I would. But you’ve fragged mechs before me, haven’t you?”

“Obviously” Rodimus agreed, not embarrassed by the admission despite the way his servos were tentative as they settled on Ratchet’s knees. “Maybe not as many as you, old mech, but more than enough.”

“Then you know it’s not as clean cut as better or worse. If I just said sure, you’re better than Optimus, you wouldn’t believe me anyway.”

Rodimus’s lips pressed together before nodding.

“Yeah, I know. Again, I already told you it was a dumb question.”

Ratchet’s servos strayed to Rodimus’s chest, aware of all the mechanics that lay beneath it between him and the Prime’s spark.

“Course it is. But that doesn’t mean you don’t need an answer.” Ratchet took a moment to consider his next words carefully, aware of the thin ice they were walking on and the spark beneath his palm. “The aura – the draw to you because you’re a Prime is the same, certainly. I won’t deny that.” Rodimus nodded slightly, optics zeroed in on Ratchet, as if waiting for a striking blow. With another in-vent, Ratchet continued, “But beyond that, it’s not really a matter of being ‘better’ because interfacing with Optimus was completely different.”

Rodimus’s lips pursed as he parroted back, “‘Different,’” looking utterly unimpressed.

And Ratchet couldn’t help the slight curling of his mouth.

“Don’t you give me attitude. You wanted the truth, and that’s the truth.”

“Just seems like the easy way out.”

Ratchet shrugged as he let his digits stray, trailing them down the emblem on Rodimus’s chest to trace the midline of his abdominal plating.

“It does sound cliché, but that doesn’t make it untrue.”

Rodimus’s servos squeezed Ratchet’s knees as his plating shuddered ever so slightly under Ratchet’s digit tips.

“Fine, guess I’ll have to just ask more specific questions then,” Rodimus said, acting put-upon about the whole thing, and already that shade of theatrics was an improvement in Ratchet’s optics. The sly look pulling at his expression was endearing as he asked, “Tell me something that’s better about fragging with me than with Optimus.”

There was no possible way for Ratchet to keep from snorting, bowing his helm to try to stifle it only to have it break free when Rodimus smacked his knee.

“What?” Rodimus demanded. Ratchet shook his helm as he bent forward, moving his servo from Rodimus’s middle to his collar.

“Nothing. Just should have known,” Ratchet said as he grasped the edge of Rodimus’s collar tightly to yank him up, pulling him into a kiss that Rodimus was quick to melt into. Not that Ratchet lingered for long, pulling away as he purred teasingly, “You’re a glutton for praise, after all.”

Ratchet deserved the dentae sinking into his bottom lip for the comment.

“Jerk.”

After running his glossa along his lip to soothe the slight ache from Rodimus’s retaliation, Ratchet pushed back up to peer down at his berthmate. It was only because Ratchet knew he had burned through the divinely inspired desire earlier that he could deduce the warming of his spark had nothing to do with Primehood.

“Optimus and I only interfaced a couple dozen times.”

Rodimus blinked up at him. And then continued to blink at him before finally managing to say, “What?”

“As I’m sure you’re aware, a Prime’s aura doesn’t work on himself. While he riled all of us up, Optimus only ever had his naturally forged interface drive,” Ratchet explained. His digits went back to work, tracing the edges of Rodimus’s plating along his sides. However, the smile on his face slowly faded as he continued, “And he wasn’t much in the mood, what with leading an army at war. So it was a rare that he would come to me for something like this.”

The younger Prime’s expression softened.

“I guess the circumstances weren’t great.”

“Not particularly.” Ratchet’s servo drifted to Rodimus’s hips to find the seams of his interface panels. “I still welcomed those moments, but ultimately there’s something lost when you have to relearn your partner’s frame every time you come together. Considering how often he got slagged and rebuilt, that was usually literally.”

It only took a couple taps for Rodimus to open for Ratchet. While the conversation surely wasn’t particularly stimulating for the Prime’s array, his valve was still wet from their earlier couplings.

“You’re insatiable, you know that?”

“I’m just proving a point,” Ratchet insisted as he swirled his digits in the mess of Rodimus’s valve. “We’ve already fragged more times that Optimus and I did over the span of the entire war, which means you’ve gotten a pretty good feel for my frame and what gets me off.” Ratchet’s tone was casual, as if his digits weren’t pressing into Rodimus’s well-used valve with ease, slicked by the mixture of lubricant and transfluid. Rodimus’s mouth gaped open as Ratchet curled his digits and on his first try found the hypersensitive bundle of receptors at the front of his valve wall, a weak gasp tumbling from kiss-bruised lips. There was no hiding the self-satisfied grin from Ratchet’s face. “And vice versa. I’ve fragged you enough now that I could find your hot spots while I was in recharge.”

Rodimus’s optics brightened and he grinned.

“Frag yeah. Pretty sure I could get you off faster though.”

Ratchet chuckled as he let his digits massage the bundle and watched Rodimus’s frame arch away from the berth and down against his servo.

“Than I could get you off? Or than Optimus could get me off?”

Rodimus hummed as his optics offlined, though it was unclear if it was due to being lost in pleasure or thought. Ultimately though, after groaning softly, he managed, “Both. Definitely both.”

His whole frame jerked when Ratchet’s free servo moved to press his thumb into Rodimus’s spike sheath, teasing the spike tip that had yet to fully emerge.

“Well, you’re right about one of those things.”

One of Rodimus’s optics onlined, and his grin was frankly goofy looking as he said victoriously, “You think I can get you off faster than Optimus can.”

With a small shrug, Ratchet continued his ministrations, quietly enjoying the way he could toy with Rodimus’s frame with such ease, knowing it – knowing him – so intimately.

He did notice though how Rodimus’s valve clenched around him with the revelation though, and how his spike finally pressurized free of his sheath.

“Is his spike bigger than mine?”

That caught Ratchet off guard, ripping a full-frame laugh from him. “Are you serious?”

“I’m not asking you to draw me a picture,” Rodimus insisted as his hips started to pump on Ratchet’s digits, seeking even more stimulation. The grin on his face gave away his own humor. “Just want to know if, you know. He’s proportional down there.”

Ratchet flicked his gaze down to Rodimus’s spike – still garishly painted, but it was endearing to him now in how very Rodimus it was, and the ridges and texture were at least tasteful and felt incredible in his valve – before looking back up at Rodimus’s face.

“He’s bigger than you.”

Rodimus groaned a very unsexy groan as he flopped onto the berth, grousing, “Come on, Ratchet, you can’t just say that!”

“You asked,” Ratchet pointed out.

“Well, yeah, but that’s something you lie about,” Rodimus insisted, pouting, and Ratchet had to resist the urge to lean down and either kiss the Prime or bite at his chin in chastisement.

“Should have known better than to think I’d lie.” Despite Rodimus’s grumbling, his spike pulsed under the brush of Ratchet’s knuckles, twitching when he thumbed the sensitive sensors just under the head. “Besides, I usually prefer spikes like yours anyway.”

Rodimus’s valve clenched around his digits again and his spike fully pressurized with a throb.

“Yeah?” Rodimus prompted and Ratchet chuckled as he grasped Rodimus’s spike.

“Glutton.”

“Yeah, yeah,” Rodimus managed as his cooling fans kicked up another gear. “I’m a glutton for praise and you like using it against me, so just tell me how much you like my spike so we can both get what we want, would you?”

“You make a strong argument.” Ratchet took one more moment to just enjoy the Prime’s frame pressing into his servos, seeking out the pleasure he provided, before explaining, “If Optimus was spiking then I had to be loosened up beforehand. There was simply no getting around it, no matter how much I might want it hard and fast. But with a spike like yours?” Ratchet gave said spike a couple good pulls as Rodimus gazed up at him expectantly. Ratchet gave him a lecherous grin. “We can skip the niceties and get the damn thing done and done right.”

Transfluid beaded at the tip of Rodimus’s spike as he groaned and his optics flared.

“Primus, Ratch,” Rodimus managed. “You sure know how to make a guy feel special.”

“It’s a gift.”

“And mechs call me intolerable.”

Ratchet chuckled as he leaned in close again, but just enough to brush his nose with Rodimus’s, making sure to pull away before the Prime could steal a breathless kiss.

“You’ll have to try harder than that to insult me.”

The servo snapping up to drag Ratchet down had been unexpected and there was no denying Rodimus when their lips met. But even when the Prime tipped his helm back to try to suck down more cool air, his servo held firm, keeping Ratchet close as his optics cycled, staring up at the medic.

“What’s different about this?” Rodimus asked, voice still strained from arousal but softer now, his optics discerning. His servo tightened on the back of Ratchet’s neck, holding him close. “Not better, just – just different.”

Ratchet’s spark thudded in his chest.

“I found comfort with Optimus,” Ratchet admitted, sure that the humor was softening, and with its waning went what little youth his face still held. “We came from a similar time and place, and we’ve grown and aged together, seen many of the same horrible things together. So it was comforting with him. It was safe. We knew each other too well to hide anything.”

Ratchet’s servos had slowed their attentions, but Rodimus didn’t seem to mind or even notice. Not with the intensity of his focus on Ratchet.

“And with me?”

“And with you, well—Primus strike me where I stand, but I actually have fun with you.” Ratchet’s chuckle rang with self-deprecation when Rodimus’s optics widened at that. “I realize that sounds small in comparison, but it’s easy to forget sometimes that just because my youth is long gone doesn’t mean that brat I used to be isn’t still kicking around in this old spark of mine desperate to have some fun.”

Rodimus still stared up at him with wide, over-bright optics.

And then he was pushing up from the berth, shoving Ratchet up and over, ignoring Ratchet’s startled complaints until Rodimus had fully turned the tables, sprawling Ratchet on his back and straddling his broad hips and pinning his servos next to his helm.

“What’s gotten into you--?!”

“Open up,” Rodimus insisted as his valve dragged across the panel separating it from Ratchet’s spike. “I need to ride you so fragging hard, Ratch.”

The quiet rumble of lust that Ratchet had harbored while teasing Rodimus’s frame roared to life all at once, as if it was just another flame under Rodimus’s command, burning Ratchet up from the inside out. There was simply no way to deny Rodimus. Ratchet’s spike barely had a moment to start pressurizing before Rodimus settled his valve over it, giving Ratchet nowhere to pressurize but directly into soft wet heat.

“By the Unmaker,” Ratchet ex-vented as his helm fell back against the berth, optics offlining for that moment as pleasure assaulted his frame so suddenly. Rodimus’s digits entangled with his own where they were pinned. “You have to tell me what I said so I can use it again.”

Rodimus’s laugh was light and beautiful and his hips began to lift and fall.

“It’s like you said before,” Rodimus said as his servos squeezed and pressed against Ratchet’s. He was already setting a quick pace, panting and groaning as he followed through on his word and rode Ratchet in earnest. “I’m a sucker for your praise.”

Even as Ratchet was finding his frame being pulled into Rodimus’s passion, the Prime’s valve working hard to drag an overload from him and winning the fight, he managed to say, “Wasn’t praise, just an answer to your question.”

Rodimus’s lips pulled up into a wide and easy grin and his optics were bright with emotions that Ratchet couldn’t rightly pinpoint.

“Oh, believe me, Ratchet, it was praise. If I can make a bucket of bolts like you feel young, I have to be doing something right.”

Ratchet let out a noise halfway between a grunt and a startled laugh. “Braggart,” he managed as his servos tugged where Rodimus held them, hoping to reach down and grasp the Prime by the hips. But Rodimus’s hold stayed firm and Ratchet easily relented to the casual show of control.

“Now that one I don’t hear as often,” Rodimus teased. His frame moved fluidly, rolling into each grind of his valve meeting Ratchet’s plating, his spike engulfed in glorious silken protomesh before Rodimus would lift away for another roll of his hips. The low whine that caught in Rodimus’s vocalizer had Ratchet’s hips jerking up to meet that next roll. “Fraaaag. Honestly, I dunno how you do it, but you manage to make me feel young again.”

“Oh? Are you actually acknowledging your age for once?”

Dentae found Ratchet’s bottom lip yet again and, truthfully, the brief, sharp pain only had him groaning against Rodimus’s mouth.

“Shut up.”

“Captains first.”

There was nothing quite like the rumbling of Rodimus’s frame when he laughed and how it transferred through his valve, calipers rippling around Ratchet.

“Primus, neither of us is ever going to shut up then.”

“Let go of my servos and I’ll see if I can’t at least keep your mouth busy with just my name.”

Rodimus’s helm bumped against Ratchet’s as he heaved with giggles, optics shut tight and the protomesh wrinkling at the corners of them from his overwhelming glee, pausing in his ride while his valve fluttered with the rest of his frame.

And Ratchet’s spark felt lighter than it had in literal ages.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The return of coal mining at Cedar Mountain (aka West Coast Coal) was brought about by a mysterious figure. His name was John “Jack” McQuade. Are you ready for his story and a deeper investigation into his importance to the area?

My first clue about McQuade was in Edith Cavanaugh’s article in the 1961 Seattle Times called Lost Towns of King County; Busy Cedar Mountain only a memory. She told the reporter:

The mine experienced several shutdowns and was reopened about 1920, when John McQuade found the coal seams again. He leased the property to the Pacific Coast Coal Co., which sold to E.R. Peoples. The last operators were Ed Littlefield and his mother, who inherited the coal mine

When I read that I remember that early coal mine map of the Jones Slope. On that were two smaller shafts and penned in very small print along the shaft was “McQuade Slope”. It is bottom center on the map below.

Close up of the two 1920 Cedar Mtn Slopes – DNR Coal Mine Map K_41A

This map was published in 1920 by Pacific Coast Coal Company (PCCC) when they first purchased the rights to the Indian Mine from the Jones Brothers and Cedar Mountain Coal Co from the Campion Family who managed the estate of John Colman. Funny how this little clue would drive me to dig even more into the what, why and how the mine was brought back from life support.

Of course I wanted to look for this clue to the past. I did find a sink hole on 194th Ave SE that I believe is the McQuade Slope mine shaft. Read more about that search and these mines at Link to article on #4 & #5 Cedar Mtn Mine Shafts

Sink hole on east side of 194th Ave SE – McQuade Slope I bet

The second thing I read about McQuade was around the house he built in 1925 on the north side of the Jones Road Bridge on the Cedar River. It was built from very beautiful brick manufactured by the Denny Renton Clay Brick Company. How could he afford this mansion house was voiced in the 1970s? The mystery was thickening.

McQuade Home from across the river

Front Door of Brick McQuade Home

John McQuade House from Jones Road

Here is that little scrap of info around the house & our Mystery Man. Bill at Palmer Coking Company sent me this inside a bunch of miscellaneous items around the New Black Diamond Coal Mine. Not till I moved to investigating the Cedar Mountain Coal Mines did this make any sense or became relevant.

Note from Robert Cunningham in 1973 sent to me by Bill of Palmer Coking Company

Around the same time (1926) McQuade’s grown son Thomas bought property just to the west of the New Black Diamond Coal Mine (aka Indian). There he built a grocery with a house above it in anticipation of a town being built around the mine. This store still exists on the Maple Valley Renton Highway and is better known as the 76 Gas Station. Where did the money come from for that?

Today the Tom McQuade’s Store built for New Black Diamond Coal Mine – per Google Street View

This all points to him buying and making a success of the mine across the river where a fault had caused closure in the 1890s. As a refresher see the map below. The mine I am referencing is labeled the second & largest mine (on the right side of map). It is the mine shaft that I could not physically get too. Quest for Mine Entrance Article

Over view map to give you the lay of the land of Cedar Mtn Town & Mines.

Are you following along and see where I am going? It is all about the question of when and how did McQuade’s finger cause the revitalization of the Cedar Mountain Coal Mines? Only a few clues exist around it. Time to dig deeper.

My research for any and all clues took over. That is right, another rabbit hole consumed Batgirl. This Cedar Mountain Coal Mine had so many players, locations and the data was all over the place.

Are you ready to get into the weeds? Meet the man of mystery! John “Jack” McQuade.

John McQuade

He was born in County Tyrone Ireland 10/14/1863. He immigrated in 1880 per bio from Issaquah Museum but the censuses and his obituary in The Issaquah Press have different dates. Hard to tell which is the right date and from my research on my grandfather it is not uncommon in this period to have discrepancies.

In May 1880 (substantiates earlier immigration date), his mining career started in New Castle, Pennsylvania as a miner. Then he traveled to Canada and mined in Nanaimo BC. Back to the USA, he went to Butte MT in 1883 and next to Cedar Mountain, working for Colman in 1885. One has to assume this knowledge on the first Cedar Mountain slope/mine entrance brought him back again and again.

With his mining experience and the lure of something different he went to work on the Northern Pacific Railroad Stampede Tunnel in 1886. He must have been working at it from the beginning until the end. They started hand drilling it on February 13, 1886. Moved to air drills and the two tunnels met into one May of 1888. It opened soon thereafter.

McQuade came to Gilman/Issaquah in 1888 (per Bio on Issaquah Museum site). That corresponds with the tunnel’s completion. He married Margarette (Maggie) Lewis 3/15/1890 in Seattle. They had four sons; Thomas, Charles, John, and William and three daughters; Edith, Ethel and Margarette.

Railroad service came to town in 1887 and the coal and lumber industry took off. Next the town was platted in 1888, and incorporated under the name Gilman in 1892. The townsfolks renamed the village to Issaquah in 1899. Our guy was in the middle of all this early history.

When the town was incorporated he was appointed the first Gilman Marshal in April 1892 and continued in that position until February 1898. I also found he was Deputy Sheriff for North Bend but no dates listed. He was next the Mayor from January thru April 1900. The census of 1900 captures him twice and adds a little spin to his mining experience.

First 1900 census in Gilman Town with wife & 4 kids – owned house outright on Front Street – listed as Marshal instead of Mayor– Bio states this is confusing & perhaps he was filling in.

Second count he is on the Passenger list of the Whaler Jeannie of San Francisco in Nome, AK. A gold rush had occurred that year where you could pick nuggets off the beach. Bio states he went to Alaska to mine. Could he have grabbed some of those nuggets?

Another confirmation of his Alaska adventures is I found him listed in Nome on the Alaska-Yukon Gold Rush Participants list compiled around 1899 – 1900. (also found two Jones Brothers and my Grandfather on this list)

Issaquah History Museum Photo

More Census data I found:

Census 1910 – Issaquah with wife & 6 kids on Front Street – listed as miner. Looks like he was no longer in civic service but was full time into the mining scene. Not sure what mine though.

Census 1920 – Issaquah Town with wife & 5 kids on Front Street – listed as coal mine operator (Connect the McQuade Slope and Edith’s comments) Also said he immigrated to US in 1883 & naturalized in 1889. Hmmm.. Does not agree with bio or 1930 census.

Found that one of his Issaquah homes was saved and rebuilt at the Gilman Village Shopping Center. They moved a lot of old structures to create an eclectic group of shops and stores. My research on age and where it was originally located did not yield much info.

McQuade House at Gilman Village

He took over Cedar Mtn Mine in 1926 according to his Bio and Obituary. Colman/Campion company was Cedar Mountain Coal Company. I believe this is when the revitalized portion of the mine was renamed West Coast Coal Company.

He built his wonderful Brick House 1925 thru 1927 at 20005 SE Jones Road.

Census 1930 – Cedar Mountain Brick Home with wife & 2 kids – listed as mine operator. I had to manually find this census since this page was torn & taped right over them. Just to add to the confusion it had an 1878 immigration date.

Died at Cedar Mountain Brick Home 6/24/1934. He is buried in Greenwood Cemetery, Renton, WA.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

This is the same cemetery where Jimmy Hendrix is buried and a large memorial erected.

Hendrix Memorial at Greenwood Cemetery, Renton, WA

This brings us back to the mystery of what happened between 1920 and 1926? How did McQuade come to find the coal seam and own this valuable piece of property and lastly afford that expensive brick home?

Let us dissect these questions one at a time. Warning!! Some of this is my assumption and what I can glean from the documents and maps.

How did McQuade find the coal seam again?

Let us start with that 1920 coal mine map K_41A that documents the Jones Slope (Indian Mine) and two Cedar Mountain slopes. One of those slopes is named McQuade Slope and I have identified it is in the northeast corner of section 30. That puts it squarely inside the Cedar Mountain Coal Mine properties owned by Colman Estate administrated by Campion.

Pacific Coast Coal Company (PCCC) purchases the Coleman Estate ownership of the Cedar Mountain Coal Mine in Section 30 in 1920. This was at the same time as they acquired the Jones Brothers’ claims.

Why did they buy this property? It was because McQuade had proved there was coal beyond the pesky fault. That made the closed Cedar Mountain Coal Mine valuable again. PCCC was going to use that info to grow their New Black Diamond development in a hope that the Jones seam/slope continued towards the McQuade Slope.

How did John McQuade benefit from this rediscovering of the lost Cedar Mountain Coal Seam?

I am assuming that Campion the executer of the Colman Estate generously shared the bounty from the PCCC purchase with McQuade.

Perhaps there was a lease agreement between them like the Jones had on their property. Whichever, he found it and thus everyone connected got rich or richer.

How did McQuade come to own considerable property including the closed mine across the river (aka West Coast Coal Mine)?

I have only more questions and conjectures to answer this with. Did he finally spend gold nuggets he potentially found in Nome, Alaska? Or did he take the funds and relationships with the Colman Estate to make his dreams come true? I am betting on The Colman Estate funding his endeavors and a slim chance he still had gold left over from Nome.

Don’t think we will ever really know the money part unless I dig in archives. Unfortunately, they are at this point closed to the public. However, this is where old property maps come in. They will demonstrate how McQuade gambled by buying the properties with potential coal. Where the funding came from might be in debate but the ownerships are not fiction.

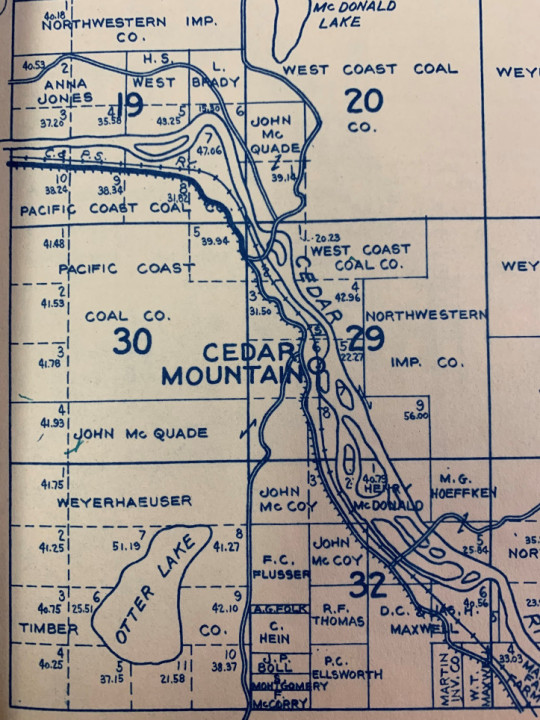

We start with the Anderson 1907 map of King County Township 23 North Range 6 East W.M.. Let us review several stakeholders in the area:

Cedar Mountain Coal Company (Colman’s mining group) can be seen in section 30. They owned the northern half plus the NW corner of the southern half.

J M Colman private holdings of the southern half of section 20.

Colman died 12/13/1906, so this and his coal company were all part of his estate in 1907. We know from the 1920 Seattle Times article about the New Black Diamond Mine that John T Campion was the executor of the Colman Estate. I also uncovered that Campion was the President of Cedar Mountain Coal Company in the State of WA Report of State Inspector of Coal Mines 1/1/1905 – 9/30/1906 Biennial Report Vol 5.

Samuel Blair (estate) was a large land owner in the areas around the Colman pieces. He held ownership in Sections 30 and 29. A piece of the section 29 property contains the large Cedar Mountain coal mine that is related to our mystery man McQuade. Over time this piece of Colman’s coal mines must have been sold to Blair and his family. Coincidentally, I think this is the same Samuel Blair who had large interests in the Seattle Coal & Transportation Company. Their prime mine was at Newcastle in the 1870s.

E. Grondahl owns a small piece between Cedar Mountain Coal & Blair in section 30.

Northwestern Improvement Company has land holdings in Section 29 around the large coal mine. That company was the Northern Pacific Railroad’s subsidiary that was set up to manage it’s land grants and other coal opportunity land purchases. They were developing coal for their own use and outside sales. The Federal government deeded certain amounts of alternating sections of public land for each mile of track that was built to encourage railroad development.

Next we have the 1912 map by Kroll which shows a few changes. Grondahl’s share of section 30 was bought up by Cedar Mountain Coal Company and Samuel Blair estate was settled and now owned by Abbie B Blair.

Lastly, this 1926 Metzker’s map below shows PCCC owns the old Cedar Mountain Coal Co (section 30) for it’s development of the New Black Diamond Coal Mine. Note that Lots 8, 9 & 10 of Section 19 is owned by PCCC and is where the major industrial complex is built.

To seal the deal on our mystery man’s rise to becoming a coal mine owner the map shows that McQuade has purchased the Blair & J.M. Coleman properties. Some of which have been added to a company called West Coast Coal Co. This includes the property where McQuade’s house is built in the southwest corner of section 20 on this map.

His coup d’état!!

What a man John McQuade must have been. I am not 100% sure of all the details but my research gave us good clues. Our man of mystery pulled off the gamble that he could find the coal again. Then he capitalized on that find to redevelop the original Cedar Mountain Coal Mine.

That is how the Cedar Mountain Coal Mine was resurrected.

Time to move on to my next article. We will follow the final batch of owners and a few other characters around Cedar Mountain Coal Mines. That will bring us to the conclusion my adventure and research on this coal mine with so many players and mine shafts.

If you want to read more about my search for Lost Coal Mines here is a link to my directory of articles.

Shoot me any questions or better yet any information you have to add. This is a never ending deep dig into 100 years of old coal mine history.

Remember Times are a changing. Blink and all will be changed. Literally, a town (Cedar Mountain) can disappear!

Locating Lost Old Coal Mines of King County

Cedar Mountain Coal Revival The return of coal mining at Cedar Mountain (aka West Coast Coal) was brought about by a mysterious figure.

#Cedar Mountain Coal Mine#Coal Mine HIstory#Coal Mines#Coal Mining#Indian Coal Mine#John "Jack" McQuade#Lost Coal Mines#New Black Diamond Coal Mine#West Coast Coal Mine

0 notes

Link

I.

“IF I AM out of my mind, it’s all right with me,” announces the narrator of Saul Bellow’s Herzog. Moses Herzog’s personal life has gone to pieces and having a PhD might be part of the problem. His study of Romanticism — “eight hundred pages of chaotic argument” — molders in his closet.

In Bellow’s fictional worlds, being cultured and crazy often go together. The narrator of The Adventures of Augie March is Sancho Panza to a string of Quixotes. Augie can’t resist illusion-chasing screwballs — from his brother with his get-rich schemes to a lover’s ambition to train eagles in Mexico. Toward the end of the novel, Augie’s warship is torpedoed and he finds himself in a lifeboat with a self-described “psycho-biophysicist” named Basteshaw as his sole companion. Basteshaw confides that he has managed to create living cells from inorganic matter and prophesies that his research is on course to discover a serum which will finally end human ignorance, strife, and suffering. “If he wasn’t a genius, I was in the boat with a maniac,” reflects Augie. When Augie tries to signal to a passing allied ship, Basteshaw wallops him with an oar. The psycho-biophysicist would rather drift toward the Canary Islands, to be interned on neutral Spanish territory, in order to continue his research. They struggle, Augie prevails, and they are saved. What’s more, they were never anywhere near the Canaries: “This scientist Basteshaw! Why, he was cuckoo! Why, we’d have both rotted in that African sea, and the boat would have rotted, and there would have been nothing but death and madness to the last.”

After the rescue, Basteshaw is decidedly cool with Augie. “The power of the individual to act through his intellect on the reason of mankind is smaller now than ever,” opines the lunatic.

In his earlier books, Bellow took down the intellectual life playfully. From the 1970s on, he came to examine madness as a political rather than a purely personal phenomenon. To be deluded was more than a foible in a supposedly cultured world capable of genocide. Did intellectuals and writers bear some responsibility for the disaster that had befallen Europe? Or were Pound, Heidegger, Hamsun, Céline, and all the others just sideshow clowns, fundamentally irrelevant to the great events that unfolded, and perhaps interesting only as examples of a general malaise?

Bellow had been wrestling with these questions for decades, even if they were not immediately reflected in his fiction. During his time in Paris between 1948 and 1950, he heard firsthand about life under the Nazis and the deportations of Jews, and read Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s “crazy, murderous harangues, seething with Jew-hatred.” In 1954, when William Faulkner led a group of writers petitioning the United States government for the release of Ezra Pound from a mental institution — had Pound been judged sane, a death sentence for treason for his collaboration with the Axis would have been mandatory — the dissenting voice was Bellow’s. He wrote to Faulkner that treating Pound’s advocacy of “hatred and murder” as eccentricity rather than insanity was symptomatic of the stunning indifference to recent events: “[B]etter poets than he were exterminated, perhaps,” wrote Bellow. “Shall we say nothing on their behalf?”

II.

In 1945, Europe was threatened by famine and epidemic disease. Millions of refugees had to be resettled and ruined cities and infrastructure rebuilt. The postwar denazification policies imposed by the occupying powers in West Germany focused on rehabilitating all but top-level administrators in order to create a viable state that would be a bulwark against further Soviet advance west. It was not until the 1960s, with the return of prosperity and a semblance of stability in international politics, that the subject of genocide began to be addressed. The first steps in a historiography of the Nazi Final Solution were taken in the United States, most notably with the appearance of Raul Hilberg’s The Destruction of the European Jews in 1961. That year also saw the trial in Jerusalem of Adolf Eichmann, the logistician of the Holocaust. The proceedings, under the scrutiny of television cameras and the world press, included dramatic testimony from survivors. Hannah Arendt covered the trial for the The New Yorker, and recast her articles for the book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963). In Germany, too, a new mood took hold. For the first time, the West German state tried concentration camp administrators and others who had assisted in the massacre of civilians.

“Eastern Europe has told me a lot about my family — myself even,” Bellow wrote in 1960 after a journey he made the previous year. “[W]hat I saw between Auschwitz and Jerusalem made a change in me.” Among the stories he heard from survivors were those told by his own relatives:

Cousin Bella […] tells me of one of our cousins who now lives with her husband in Geneva. During the German occupation of Riga this cousin and her sister were slave laborers in a factory that made army uniforms. Before the Germans retreated they exhumed thousands of bodies from the mass graves and burned them. A sudden sensitivity about evidence. The two young girls were among the hundreds forced to dig up putrid corpses and put them in the flames. The younger sister sickened and died.

III.

Solomon Bellows was born in Montreal in 1915 to orthodox Jewish parents from the Russian Empire. In 1924, the family moved to Chicago. Yiddish was the language of the home. For the adolescent Bellow, religion was immigrant baggage to be ditched on the road to American modernity. He became a Trotskyite. At university, he studied the radical new social science of anthropology. The publication of argotic, freewheeling Adventures of Augie March in 1953 marked him out as a literary innovator.

By the 1960s, however, America had changed. The Chicago of Augie March no longer existed. Poor but dynamic neighborhoods had transformed into an inner-city wasteland of drugs, crime, and despair: “The slums, as a friend of mine once observed, were ruined. He was not joking.” Bellow began to reflect on what had been lost, turning back toward Europe and the Jewish world.

Bellow’s detractors identify Mr. Sammler’s Planet (1970) as the point when the young literary rebel became a middle-aged champion of the elitist culture of dead white males. He was called a misogynist and even a racist. And the depiction of the United States through the eyes of Artur Sammler, a Polish Jew and refugee, is certainly provocative: “New York was getting worse than Naples or Salonika. It was like an Asian, an African town […] You opened a jeweled door into degradation, from hypercivilized Byzantine luxury straight into the state of nature, the barbarous world of color erupting from beneath.” Sammler sees a generation seeking “the free ways of barbarism” while protected by a civilized order, wealth, technology, and property rights.

Sammler has landed in the middle of a cultural revolution where nobody over 30 can be trusted. On the shores of this new world, it means nothing that he has lost his eye in the war, that his wife has been killed by a racist regime, or that he has known the foremost intellectuals of interwar London. His voice is capable of speaking of an Eastern Europe buried under communist totalitarianism, of an Ashkenazi-Yiddish civilization obliterated by genocide, and an extinct interwar intellectual order. But nobody wants to know. It is as though none of it ever happened.

Sammler cannot relate to the stew of politicized thinking around him not because it is too radical for his tastes but because it is hopelessly innocent. If America is unable to comprehend what has happened not 30 years earlier on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, then America is incapable of talking sense. Social breakdown is Bellow’s theme, but Sammler is not — solely — about the United States. In depicting countercultural America busting its mental seams through the eyes of a Holocaust survivor, Bellow is widening his lens in an attempt to take in the recent history of the planet. If in his earlier novels he was happy to study individuals who were “nuts” or “cookoo,” now he ponders the reality of insanity as a collective phenomenon.

Intellectuals deal in reason, but their subject — human life — refuses to act reasonably. “Like many people who had seen the world collapse once,” Bellow writes, “Mr. Sammler entertained the possibility that it might collapse twice.”

IV.

The idea that modern life makes an impossible demand on the individual mind is one of Bellow’s great themes. “Too much of everything,” says Augie. “Too much history and culture […] too many details, too much news, too much example, too much influence […] Which who is supposed to interpret? Me?” Augie has no clear idea of his own what this world is but he has a strong intuition that there are as many ideas of the world as there are human beings, that each is provisional, and that all are competing for recruits. Life is a project, reality an individual projection. In this, he sees to the heart of modern — American — life. He surfs the confusion of this world, freestyle; in place of trials and anxiety he has adventures.

But by the time Bellow came to write Sammler, he had a less thrilling take on the effect of so much freedom:

The many impressions and experiences of life seemed no longer to occur each in its own proper space, in sequence, each with its recognizable religious or aesthetic importance, but human beings suffered the humiliations of inconsequence, of confused styles, of a long life containing several separate lives. In fact the whole experience of mankind was now covering each separate life in its flood. Making all the ages of history simultaneous. Compelling the frail person to receive, to register, depriving him because of volume, of mass, of the power to impart design.

The idea that modern man recoiled in despair before meaningless choice and a deluge of information was one Bellow shared with Mircea Eliade, a colleague at the University of Chicago. Eliade had been a famous novelist in interbellum Bucharest and was widely acknowledged as the intellectual leader of Romania’s younger generation of writers and thinkers. He had settled in Chicago in 1957 and, as a philosopher and historian of religions, had enjoyed huge success with the English-language publication of his book The Myth of the Eternal Return, which had sold over 100,000 copies in various editions. Bellow had come to know him in the years prior to writing Sammler.

Eliade argued that man is religious by nature, and that the fundamental feature of religious thinking is the distinction between the sacred and the profane. The sacred is all that is unchanging and essential, the profane is all that is provisional, historical, and subject to decay. The basic characteristic of all religions, Eliade maintained, is that man makes sense of the world by cultivating an awareness of the sacred, and seeks through ritual to recreate it and participate in it. Mythical thought is an attempt to reconstitute the world of the sacred, which all cultures conceive of as a prehistorical Edenic era. Traditional societies impart meaning to existence by being centered on sacred time. Modern rationality recognizes only historical time, producing “spiritual aridity” and an anxiety that Eliade called “The Terror of History.”

Eliade was Bellow’s kind of European intellectual — polyglot, intensely erudite, with more than a dash of religious mysticism thrown into the mix. Bellow’s fourth wife, Alexandra Bagdasar, whom he married in 1974, was a Romanian expatriate from an old and very cultivated Bucharest family, and the Bellows and Eliades frequently socialized. Bellow and Bagdasar divorced in 1985. Eliade died in 1986, and Bellow delivered a reading at his funeral. At this point, Bellow must have believed that the “Romanian” period of his life was over. But rumors had long been circulating about Eliade’s association with Romania’s wartime fascist Iron Guard, and they became undeniable with the 1988 publication of Mircea Eliade: The Romanian Roots, 1907-1945 by Mac Linscott Ricketts, which uncovered a series of articles Eliade had written for the Romanian fascist press in the 1930s.

V.

Ricketts, a devoted pupil of Eliade’s, was interested in his master as a philosopher and literary figure. The section on Eliade’s political writings in the 1930s takes up a few dozen pages in a two-volume work of over a thousand pages — almost as though Ricketts had accidentally tripped over a bundle of newspapers while on other business — but the contents of these articles is stunning in the context of Romanian politics in those years. In them, Eliade comes across as another Basteshaw, theorizing manically while the boat drifts the wrong way; the serum that will end the ignorance, strife, and suffering of the Romanian nation, he proposes, is nationalism.

Eliade believed that democracy was inherently unsuitable for Romania, and that democratic politics was wearing itself out with its fixation on un-Romanian “abstractions” such as the rights of minorities and freedom of political expression. And when democracy wobbled, he argued, it tended to wobble toward anarchy and communism. Only a sense of national greatness and purpose could unify the nation. In a 1936 article titled “The Democracy and the Problem of Romania,” he wrote:

Whether or not Mussolini is a tyrant is a matter of complete indifference to me. Only one thing interests me: that this man has in fifteen years turned a third-rate state into a leading power […] In the same way, I’m completely indifferent to what will happen in Romania after the liquidation of democracy. If, in overcoming democracy, Romania becomes powerful, national and well-armed, and aware of its powers and destiny — history will judge this act.

Eliade was intensely anxious about the dominance of minorities in parts of Romania and about a presumed “invasion” of Jewish immigrants spilling in from the north. His concern with the physical decline of the national stock was among the intellectual banalities of the era; in one article he proclaims that Romania cannot assimilate foreigners as it did before because the peasantry was weakened by pellagra (from a change of diet), alcoholism, and syphilis — all, he observes, due to foreign influence.

Eliade fantasized of a coming spiritual revolution. By 1936, he was projecting a transfiguring “mystical spirit” and “Romanian messianism” on the Iron Guard, while writing for its press and being seen as its leading ideologue. Perhaps Eliade found the national dream so beautiful that he was willing to overlook the violent anti-Semitism of his fellow fascists. Or perhaps he had accepted that the Jews would have to absorb the inevitable collateral damage in the creation of a national state in which every Romanian had a sense of “belonging to a chosen people.” By 1938, he was convinced his country was on the brink of transformation and claimed that the fire of Romanian Orthodox Christianity was about to “dominate” Europe with its spiritual light.

In 1937, Eliade told his friend Mihail Sebastian that he supported the Iron Guard because he had “always believed in the primacy of the spirit.” Sebastian, who was Jewish, recorded in his diary: “He’s not a charlatan and not demented. He’s just naïve. But how is such catastrophic naiveté even possible!”

“I believe in the future of the Romanian people, but the Romanian state should disappear,” Eliade told Sebastian in October 1939. In September 1940, Eliade’s wish was fulfilled: Romania became a National Legionary State, with the Iron Guard ruling in alliance with the Romanian Army. By this time Eliade was abroad, having been appointed cultural attaché to the Romanian Embassy in London in April 1940, then to the embassy in Portugal in February 1941. In June 1941, Romania began fighting alongside the Wehrmacht. At this point, Eliade turned to nebulous theorizing on the common “Latin” character of the Portuguese and Romanian peoples, and the creative and civilizing destiny of the “Latin” race. In 1943, he wrote The Romanians, Latins of the East (a slim volume that Ricketts describes as “cultural propaganda”), in which he extols Romania’s historical destiny as the protector of the fringes of Europe from Oriental barbarians. The war in the east, Eliade says, in defense of “Christian European values” — Romanian troops were at this point fighting alongside the Germans to take Stalingrad — was the latest chapter in this glorious narrative of self-sacrifice.

Ricketts’s academic biography, curiously, never mentioned that the wartime Romanian state was responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Jews. But a compelling 1991 essay in the New Republic by expatriate Romanian writer Norman Manea clearly connected Eliade with Romanian fascism. A second New Republic essay by Manea, in 1998, focused on Mihail Sebastian’s Journal (1935 to 1945). The Journal, which documents Romania’s slow slide into fascism, was published for the first time in Romanian in 1996. Along the way — as in the extracts quoted above — it records Sebastian’s sadness and perplexity at the deterioration of his friendship with “Mircea,” as Eliade’s commitment to the Iron Guard intensifies and his public expressions of anti-Semitism become more marked.

It must have occurred to Bellow by the late 1990s that Eliade had reasons of his own for feeling “a terror of history” when he asked rhetorically, in his best-selling book, how man “can tolerate the catastrophes and horrors of history — from collective deportations and massacres to atomic bombings — if beyond them he can glimpse no sign, no transhistorical meaning.”

VI.

When I met Norman Manea in 2014, on one of his trips back to Romania, I suggested that knowledge of the Holocaust as a Romanian phenomenon was not widespread in the United States in the 1980s and 1990s. “Absolutely not,” he agreed. “And this was another shock [for Bellow]. And Eliade was this great intellectual, praised in America.”

Manea and Bellow met on several occasions in the 1990s but the subject of Eliade was tactfully avoided, though Bellow certainly knew what Manea had written about Eliade. (In a letter to Philip Roth in 1997, Bellow asked for a copy of Manea’s article, remarking, “You do well to direct me, or connect me, to Eliade.”) “There was no mention of him and there was certainly at the beginning a reluctance, on his part, to meet me,” said Manea. “He was a very close friend with Eliade, he knew a bit about this story but not enough. And suddenly he felt that he was in a kind of story where he may be also partially guilty, because he was friends with him. Philip Roth used to tell me, ‘Look, Saul smells an anti-Semite a hundred miles away.’ Well, this did not occur in this case and it’s not by chance. Eliade was a refined intellectual.”

There is an additional reason why Bellow may have had difficulty discussing his friend with Norman Manea. In 1942, while Eliade was serving the regime in Lisbon, Romanian Jews were being deported to camps in Romanian-occupied Ukraine. The five-year-old Norman Manea, along with his family, was among those expelled. Over a hundred thousand of the deportees died in the camps, on the road of cold, famine, and disease, or from incidents of random violence. It is estimated that around 400,000 Jews were killed by the Romanian authorities in Romania and in the area of Ukraine under Romanian wartime occupation.

In December 1999, Bellow appointed Manea to interview him for the Jerusalem Literary Project, over the course of three two-hour videotaped sessions. But Bellow resisted Manea’s attempts to draw him out on the subject of Romania and made no mention of Ravelstein, which was months away from publication.

Almost certainly, Bellow had been learning of the contents of Sebastian’s Journal while working on what was to be his final novel. And he must have been aware that the publication of an English edition was imminent. Manea had known about the diary even before its Romanian publication — fragments had begun to appear in English in the late 1980s — and Roth had taken a great interest in its contents. “Some fragments appeared, much before, not about Eliade, exactly, but from the diary, and yes, we discussed this […] I’m presuming Philip said [to Bellow], ‘Look! You see! Here’s the real proof of everything Manea was saying before but didn’t have the documents [to prove].’” As the US publication of Sebastian’s journal drew closer, Roth was promoting it vigorously behind the scenes.

It is not surprising that Bellow, a Nobel laureate in his 85th year, should have wished to account for the fact that he had been sipping tea and conversing with a Mircea Eliade — much as Mihail Sebastian had, half a century before. And so, Bellow included a fictionalized portrait of his relationship with Eliade in what was to be his last novel, Ravelstein.

Both Sebastian’s Journal and Ravelstein were published within months of each other, in 2000.

VII.

Manea’s remark that Bellow “found himself in a kind of story” is particularly telling. Ravelstein is a roman à clef, in which Bellow set out to become the master of his story once again by presenting a version of his friendship with Eliade. The Ravelstein character is based upon Bellow’s close friend Allan Bloom. Eliade appears as a secondary character, the academic Radu Grielescu, who gallantly opens doors and pulls out chairs for the ladies, remembers birthdays and anniversaries, engages in hand-kissing and bowing — and had once written of “the Jew-syphilis that infected the high civilization of the Balkans.”

Bellow (“Chick” in the novel) goes along with the charade because the Grielescus are “socially important” for his Romanian wife. He banters in French with Madame Grielescu and never probes Radu about “people he might have known slightly with the Iron Guard.” Grielescu fidgets with his pipe and does most of the talking, the subjects ranging from yoga to Siberian shamanism to marriage customs in primitive Australia:

How could such a person be politically dangerous? […] I suppose I said to myself that this was some kind of Frenchy-Balkan absurdity. Somehow I couldn’t take Balkan fascists seriously […] But what is one to do with the learned people from the Balkans who have such an endless diversity of interests and talents — who are scientists and philosophers and also historians and poets, who have studied Sanskrit and Tamil and lectured in the Sorbonne on mythology?

Ravelstein’s judgment on the historian of religions, the theoretician of myths, is more down to earth: he asks the unworldly Chick to remember when the Iron Guard hung up Jewish corpses on meat-hooks in a slaughterhouse in the pogrom in Bucharest in 1941. “The Jews had better understand their status with respect to myth,” he says.

Why should they have any truck with myth? It was myth that demonized them. The Jew myth is connected with conspiracy theory. The Protocols of Zion for instance. And your Radu has written books, endless books, about myth […] Just give a thought now and then to those people on the meat hooks.

Bellow had criticized Hannah Arendt on several occasions since the 1960s for having been enamored of Heidegger and what Bellow called the “eros” of German culture. Now Ravelstein was reproaching Chick for a similar error.

Mircea Eliade — with his ability to make lucid sense of myth and at the same time to disappear into an unmoored world of fantasy when touched by real events — resembled a character Bellow might have created at any stage of his career as a novelist. And in his last book, Bellow himself becomes one of these foolish characters, entranced by a veneer of culture, the charm of ideas, and a world of intellectualism that reveals itself as shoddy and inadequate when set beside the brutal facts.

¤

Philip Ó Ceallaigh is short story writer as well as a translator. In 2006, he won the Rooney Prize for Irish Literature. His two short story collections, Notes from a Turkish Whorehouse and The Pleasant Light of Day, were short-listed for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award. He lives in Bucharest.

The post “The Terror of History”: On Saul Bellow and Mircea Eliade appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2MHex0U

0 notes