Text

[Cf. Calvino on "worryability."]

November 10th, 1917

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

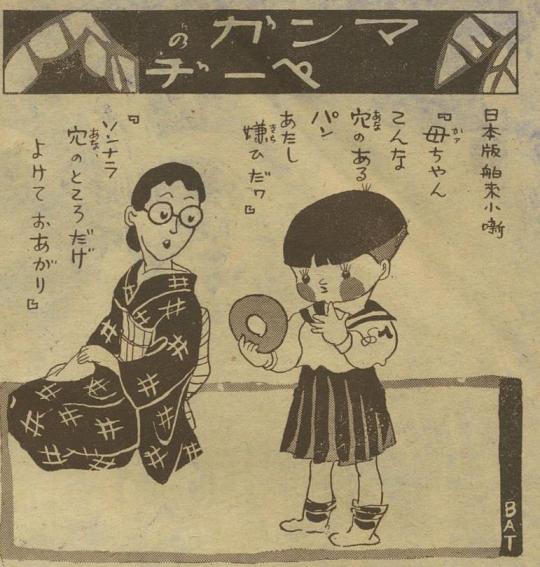

Japanese version of a small story about imported goods ‘Mom, I hate bread with holes like this.’ ‘Then eat it, avoiding only the holes.’

From a cartoon from 1935. A child who has never heard of doughnuts says something adorable. In fact, doughnuts were already a very popular snack in coffee shops and milk halls at this time.

昭和10年(1935年)の漫画より。ドーナツを知らない子供が可愛らしい事を言ってます。 実際にはこの頃は既に、喫茶店やミルクホールでドーナツは非常に人気あるお菓子だったようです。

日本版舶来小話 「母ちゃん、こんな穴のあるパン、わたし嫌ひだワ」 「ソンナラ、穴のところだけよけておあがり」

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Franz Kafka, from a letter to Milena Jesenka featured in "Letters to Milena,"

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

[See https://quoteinvestigator.com/2019/10/23/traffic/ and https://www.reddit.com/r/sciencefiction/comments/gnyksx/a_good_science_fiction_story_should_be_able_to/ for the car-traffic jam quote.]

Your mind is like a garden. If you nurture and cultivate it, it will blossom far beyond your expectations. You may expect flowers, but did you expect the brown butterfly?

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Girls in my phone I want you to know there’s one month left of this year and you can absolutely make it count and you don’t have to put your life on pause until January because it’s “too” late and you should step outside and feel the winter sun on your face and do something a little spontaneous and something a little precarious and something a little impetuous and that you should also just kick back and let the last month of this calendar year envelop you and cocoon you and ensconce you. You have time. And i also wanted to let u know that I love u

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

[Continued from above]

Mistake 1: Asymmetrical Studying

Assuming you don't just want to do a single activity in a language, or are learning a language like ASL, a language requires 4 parts to be studied: Speaking, Listening, Writing, Reading. While these have overlap, you can't learn speaking from reading, or even learn speaking from just listening. One of my first Chinese teachers told me how he would listen to the textbook dialogues while he was biking to classes and it helped him. I took this information, thought "Yeah that's an idea, but sounds boring" and now regret not taking his advice nearly every day.

I think a lot of us find methods we enjoy to study (mine was reading) and assume that if we just do that method more ™ it will eventually help us in other areas (sometimes it does, but that's only sometimes). Find a method that works for you for each area of study, even better find more than one method since we use these skills in a variety of manners! I can understand a TV program pretty well since I have a lot of context clues and body language to fill in any gaps of understanding, but taking a phone call is much harder—the audio is rougher, there's no body language to read, and since most Chinese programs have hard coded subtitles, no subtitles to fall back on either. If I were to compare the number of hours I spent reading in Chinese to (actively) training my listening? Probably a ratio of 100 to 1. When I started to learn Korean, the first thing I did was find a variety of listening resources for my level.

Fix: Find a variety of study methods that challenge all aspects of the language in different ways.

A variety of methods will help you develop a more well-rounded level of mastery, and probably help you keep from getting bored. Which is important because...

Mistake 2: Inconsistent Studying

If there is one positive to a language app, it is the pressure it puts on keeping a streak. Making studying a part of your everyday routine is the best thing you can do. I benefited a lot from taking a college language course since I had a dedicated time to study and practice Chinese 5 days out of the week (and homework usually filled the other two). Memorization is a huge part of language learning, and stopping and starting is terrible for memorization. When I was in elementary school, we had Spanish maybe a couple times a month. Looking back, it seems like it was the first class to be cut if we needed to catch up on a more important course. Needless to say, I can't even speak Spanish at an elementary level.

However, I'm sure many people reading this don't have the time to do ultra-immersion 4-hour study sessions every day either. Find what days during the week you have time to focus on learning new vocab and grammar, and use the rest of the week to review. This can be done on your commute to school/work, while you do the dishes, or as a part of your morning/evening routine. Making this as realistic as possible will help you actually succeed in making this a habit. (Check this out for how to set realistic study goals)

Fix: Study regularly (ideally daily) by setting realistic goals. Avoid "binge" studying since remembering requires consistent repetition to be most effective.

Mistake 3: Resource Choice

This is really composed of two mistakes, but I have a good example that will cover them both.

First, finding resources that are at or slightly above your level is the most important thing. Easy resources will not challenge you enough and difficult resources will overwhelm you. The ideal is n+1, with n as what you know plus 1 new thing.

Second, getting distracted by fancy, new technology. Newer isn't always better, and there are often advantages that are lost when we've made technological developments. I often found myself wanting to try out new browser extensions or organizational methods and honestly I would've benefitted from just using that time to study. (Also, you're probably reading this because of my DL post so I don't think it has to be said that AI resources suck.)

A good example of this was my time using Clozemaster. I had actually recommended it when I first started using it since I thought the foundation was really solid. However, after long term use, I found that it just wasn't a good fit. The sentences were often too simple or too long and strange for memorization at higher levels or were too difficult at lower levels. I think that taking my textbook's example sentences from dialogues into something like Anki would've been a far better use of my time (and money) as they were already designed to be at that n+1 level.

Fix: "Vet" your resources—make sure they will actually help you. If something is working for you, then keep using it! You don't always have to upgrade to the newest tool/method.

Mistake 3.5: Classrooms and Textbooks

A .5 since it's not my mistake, but an addendum of caution. I think there is a significant part of the language learning community that views textbooks and classroom learning as the worst possible resource. They are "boring", "outdated", and "ineffective" (ironically one of the most interesting modern language learning methods, ALG, is only done in a classroom setting). Classrooms and textbooks bring back memories of being surrounded by mostly uninterested classmates, minimal priority, and a focus on grades rather than personal achievement (imagine the difference between a class of middle schoolers who were forced to choose a foreign language vs. adult learners who self-selected!) People have used these exact methods, or even "cruder" methods, to successfully learn a language. It all comes down to what works best for you. I specifically recommend textbooks for learning grammar and the plentiful number of dialogues and written passages that can function great as graded readers and listening resources. (Also the distinction made between "a youtube lesson on a grammatical principle" which is totally cool, and "a passage in a grammar textbook" is more one of tone and audio/written than efficacy).

Classrooms can be really great for speaking practice since they can be a lot less intimidating speaking to someone who is also learning while receiving corrections. Speech can be awkward to train on your own (not impossible if you're good at just talking aloud to yourself!), and classrooms can work nicely for this. Homework and class schedules also have built in accountability!

Fix: Explore resources available to you and try to think holistically about your approach. CI+Traditional Methods is my go to "Learning Cocktail"

Mistake 4: Yes, Immersion, But...

I realized this relatively quickly while learning Chinese, but immersion at a level much higher than your current level will do very little for you. What is sometimes left out of those "Just watch anime to learn Japanese" discussions is that you first need to have a chance at understanding what is being said. Choosing materials that are much higher than your level will not teach you the language. It doesn't matter how many times someone at HSK 1 hears “他是甘露之惠,我并无此水可还”, they will not get very far. Actual deduction and learning comes from having enough familiar components to be able to make deductions—something different than guessing. An HSK 1 learner, never having heard the word 老虎 will be able to understand "tiger" if someone says “这是我的老虎” while standing next to a tiger. This is not to say you can never try something more difficult—things should be challenging—but if you can't make heads or tails of what's being said, then it's time to find something a bit easier. If mistake 2 is about the type of method, this is about the level. If you wouldn't give a kindergartener The Great Gatsby to learn how to read, why would you watch Full Metal Alchemist to start learning a language?

Side note: Interesting video here on the Comprehensible Input hypothesis and how it relates to neurodivergence.

Fix: Immerse yourself in appropriate content for your level. It's called comprehensible input for a reason.

Mistake 5: On Translation

I work as a translator, so do you really think I'm going to say translation is all bad? Of course not. It's a separate skill that can be added on to the basic skills, but is really only required if you are A. someone who is an intermediary between two languages (say you have to translate for a spouse or family member) or B. It is your job/hobby. In the context of sitting down and learning, it can be harmful. I think my brain often goes to translation too often because that's how I used to learn. Trying to unlearn that is difficult because, well, what do people even mean when they say "don't translate"? They mean when someone says "thank you", you should not go to your primary language and translate "you're welcome" from that. You should train yourself to go to your target language first when you hear the word for "thank you". A very literally translated "thank you" in Chinese "谢谢你" can come off as cold and sarcastic. I don't tell my friends that, I say "谢啦~". Direct translation can take away the difference in culture, grammar, and politeness in a language. If there is a reason you sound awkward while writing and speaking, it's probably because you're imposing your primary language on your target language.

Fix: Try as hard as you can to not work from your primary language into the target language, but to work from the structures, set phrases, and grammar within the target language that you know first.

Mistake 6: The Secret Language Learners Don't Want You To Know...

...is that there is no one easy method. You are not going to learn French while you sleep, or master Korean by doing this one easy trick. Learning a language requires work and dedication, the people that succeed are those that push through the boredom of repetition and failure. The "I learned X in 1 year/month/week/day!" crowd is hiding large asterisks, be it their actual level, the assistance and free time available to them, "well actually I had already studied this for 4 years", or just straight-up lying. Our own journeys in our native tongue were not easy, they required years and years of constant immersion and instruction. While we are now older and wiser people that can make quick connections, we are also burdened with things like "jobs", "house work", "school work", and the digital black hole that is "social media" that take up our time and energy. Everything above is to help make this journey a little bit easier, quicker, and painless, but it will never be magic.

I find that language learning has a lot in common with the fitness community. People will talk about the workout that changed their life and how no other one will do the same—and it really can be the truth that it changed their life and that they feel it is the ultimate way. The real workout that will change your life is the one you're most consistent with, that you enjoy the most. Language learning is just trying to find the brain exercise that you can be the most consistent with.

Fix: Save your energy looking for shortcuts, and do the work, fail, and come back for more. If someone tells you that you can become fluent in a ridiculously short amount of time, they are selling you a fantasy (and likely a product). You get out what you put in.

For those that made it to the end, here are some of my "universal resources":

Refold Method: I don't agree with their actual method 100%, but they've collected a lot of great resources for learning languages. I've found their Chinese and Korean discords to also be really helpful and provided even more resources than what's given in their starter guides.

Language Reactor: Very useful, and have recently added podcasts as a material! The free version is honestly all you need.

Anki: If I do not mention it, the people with 4+ year streaks with a 5K word deck will not let me forget it. It can be used on desktop or on your phone as an app. If you need a replacement for a language learning app, this is one of them. Justin Sung has a lot of great info on how to best utilize Anki (as does Refold). It's not my favorite, but it could be yours!

LingQ: "But I thought you said language apps are bad!" In isolation, yes. Sorry for the clickbait. This one is pretty good, and more interested in immersing you in the language than selling a subscription to allow you to freeze your streak so the number goes up.

Grammar Textbooks: For self-taught learning, these are going to be the best resource since it's focused on the hardest part of the language, and only that. If you're tired of seeing group work activities, look for a textbook that is just on grammar (Modern Mandarin Chinese Grammar is my rec for Chinese, and A Guide to Japanese Grammar by Tae Kim is the most common/enthusiastic rec I've heard for Japanese).

Shadowing: Simply repeat what you hear. Matt vs Japan talks about his setup here for optimized shadowing (which you can probably build for a lot cheaper now), but it can also just be you watching a video and pausing to repeat after each sentence or near simultaneously if you're able.

Youtube: Be it "Short Story for Beginners", "How to use X", "250 Essential Phrases", or a GRWM in your target language, Youtube is the best. Sometimes you have to dig to find what works for you, but I imagine there is something for everyone at every level. (Pro tip: People upload textbook audio dialogues often, you don't even have to buy the textbook to be able to learn from it!)

A Friend: Be it a fellow learner, or someone who has already mastered the language, it is easier when you have someone, not only to speak to, but to remind you why you're doing this. I write far more in Chinese because I have friends I can text in Chinese.

Pen and Paper: Study after study, writing on paper continues to be the best method for memorization. Typing or using a pen and tablet still can't compare to traditional methods.

The Replies (Probably): Lots of people were happy to give alternatives for specific languages in the replies of my DL post. The community here is pretty active, so if this post blows up at least 20% of what the last one did, you might be able to find some great stuff in the replies and reblogs.

I wish you all the best~

Language Apps Suck, Now What?: A Guide to Actually Becoming "Fluent"

The much requested sequel to my DL post that was promised almost a year ago.

I'm going to address all of the techniques that have helped me in my language learning journeys. Since 95% of these came from the fact that in a past language learning mistake, they are titled as my mistakes (and how I would/did things differently going forward). For those that read to the bottom there is a "best universal resources" list.

Disclaimers:

"Fluency" is hard to define and everyone has their own goals. So for the purpose of this post, "fluency" will be defined as "your personal mastery target of the language".

If you just want to pick up a bit of a language to not sound like a total foreigner on vacation or just exchange a few words in a friend's native language, feel free to ignore what doesn't apply, but maybe something here could help make it a little easier.

This is based on my own personal experience and (some) research.

Mistake 1: Asymmetrical Studying

Assuming you don't just want to do a single activity in a language, or are learning a language like ASL, a language requires 4 parts to be studied: Speaking, Listening, Writing, Reading. While these have overlap, you can't learn speaking from reading, or even learn speaking from just listening. One of my first Chinese teachers told me how he would listen to the textbook dialogues while he was biking to classes and it helped him. I took this information, thought "Yeah that's an idea, but sounds boring" and now regret not taking his advice nearly every day.

I think a lot of us find methods we enjoy to study (mine was reading) and assume that if we just do that method more ™ it will eventually help us in other areas (sometimes it does, but that's only sometimes). Find a method that works for you for each area of study, even better find more than one method since we use these skills in a variety of manners! I can understand a TV program pretty well since I have a lot of context clues and body language to fill in any gaps of understanding, but taking a phone call is much harder—the audio is rougher, there's no body language to read, and since most Chinese programs have hard coded subtitles, no subtitles to fall back on either. If I were to compare the number of hours I spent reading in Chinese to (actively) training my listening? Probably a ratio of 100 to 1. When I started to learn Korean, the first thing I did was find a variety of listening resources for my level.

Fix: Find a variety of study methods that challenge all aspects of the language in different ways.

A variety of methods will help you develop a more well-rounded level of mastery, and probably help you keep from getting bored. Which is important because...

Mistake 2: Inconsistent Studying

If there is one positive to a language app, it is the pressure it puts on keeping a streak. Making studying a part of your everyday routine is the best thing you can do. I benefited a lot from taking a college language course since I had a dedicated time to study and practice Chinese 5 days out of the week (and homework usually filled the other two). Memorization is a huge part of language learning, and stopping and starting is terrible for memorization. When I was in elementary school, we had Spanish maybe a couple times a month. Looking back, it seems like it was the first class to be cut if we needed to catch up on a more important course. Needless to say, I can't even speak Spanish at an elementary level.

However, I'm sure many people reading this don't have the time to do ultra-immersion 4-hour study sessions every day either. Find what days during the week you have time to focus on learning new vocab and grammar, and use the rest of the week to review. This can be done on your commute to school/work, while you do the dishes, or as a part of your morning/evening routine. Making this as realistic as possible will help you actually succeed in making this a habit. (Check this out for how to set realistic study goals)

Fix: Study regularly (ideally daily) by setting realistic goals. Avoid "binge" studying since remembering requires consistent repetition to be most effective.

Mistake 3: Resource Choice

This is really composed of two mistakes, but I have a good example that will cover them both.

First, finding resources that are at or slightly above your level is the most important thing. Easy resources will not challenge you enough and difficult resources will overwhelm you. The ideal is n+1, with n as what you know plus 1 new thing.

Second, getting distracted by fancy, new technology. Newer isn't always better, and there are often advantages that are lost when we've made technological developments. I often found myself wanting to try out new browser extensions or organizational methods and honestly I would've benefitted from just using that time to study. (Also, you're probably reading this because of my DL post so I don't think it has to be said that AI resources suck.)

A good example of this was my time using Clozemaster. I had actually recommended it when I first started using it since I thought the foundation was really solid. However, after long term use, I found that it just wasn't a good fit. The sentences were often too simple or too long and strange for memorization at higher levels or were too difficult at lower levels. I think that taking my textbook's example sentences from dialogues into something like Anki would've been a far better use of my time (and money) as they were already designed to be at that n+1 level.

Fix: "Vet" your resources—make sure they will actually help you. If something is working for you, then keep using it! You don't always have to upgrade to the newest tool/method.

Mistake 3.5: Classrooms and Textbooks

A .5 since it's not my mistake, but an addendum of caution. I think there is a significant part of the language learning community that views textbooks and classroom learning as the worst possible resource. They are "boring", "outdated", and "ineffective" (ironically one of the most interesting modern language learning methods, ALG, is only done in a classroom setting). Classrooms and textbooks bring back memories of being surrounded by mostly uninterested classmates, minimal priority, and a focus on grades rather than personal achievement (imagine the difference between a class of middle schoolers who were forced to choose a foreign language vs. adult learners who self-selected!) People have used these exact methods, or even "cruder" methods, to successfully learn a language. It all comes down to what works best for you. I specifically recommend textbooks for learning grammar and the plentiful number of dialogues and written passages that can function great as graded readers and listening resources. (Also the distinction made between "a youtube lesson on a grammatical principle" which is totally cool, and "a passage in a grammar textbook" is more one of tone and audio/written than efficacy).

Classrooms can be really great for speaking practice since they can be a lot less intimidating speaking to someone who is also learning while receiving corrections. Speech can be awkward to train on your own (not impossible if you're good at just talking aloud to yourself!), and classrooms can work nicely for this. Homework and class schedules also have built in accountability!

Fix: Explore resources available to you and try to think holistically about your approach. CI+Traditional Methods is my go to "Learning Cocktail"

Mistake 4: Yes, Immersion, But...

I realized this relatively quickly while learning Chinese, but immersion at a level much higher than your current level will do very little for you. What is sometimes left out of those "Just watch anime to learn Japanese" discussions is that you first need to have a chance at understanding what is being said. Choosing materials that are much higher than your level will not teach you the language. It doesn't matter how many times someone at HSK 1 hears “他是甘露之惠,我并无此水可还”, they will not get very far. Actual deduction and learning comes from having enough familiar components to be able to make deductions—something different than guessing. An HSK 1 learner, never having heard the word 老虎 will be able to understand "tiger" if someone says “这是我的老虎” while standing next to a tiger. This is not to say you can never try something more difficult—things should be challenging—but if you can't make heads or tails of what's being said, then it's time to find something a bit easier. If mistake 2 is about the type of method, this is about the level. If you wouldn't give a kindergartener The Great Gatsby to learn how to read, why would you watch Full Metal Alchemist to start learning a language?

Side note: Interesting video here on the Comprehensible Input hypothesis and how it relates to neurodivergence.

Fix: Immerse yourself in appropriate content for your level. It's called comprehensible input for a reason.

Mistake 5: On Translation

I work as a translator, so do you really think I'm going to say translation is all bad? Of course not. It's a separate skill that can be added on to the basic skills, but is really only required if you are A. someone who is an intermediary between two languages (say you have to translate for a spouse or family member) or B. It is your job/hobby. In the context of sitting down and learning, it can be harmful. I think my brain often goes to translation too often because that's how I used to learn. Trying to unlearn that is difficult because, well, what do people even mean when they say "don't translate"? They mean when someone says "thank you", you should not go to your primary language and translate "you're welcome" from that. You should train yourself to go to your target language first when you hear the word for "thank you". A very literally translated "thank you" in Chinese "谢谢你" can come off as cold and sarcastic. I don't tell my friends that, I say "谢啦~". Direct translation can take away the difference in culture, grammar, and politeness in a language. If there is a reason you sound awkward while writing and speaking, it's probably because you're imposing your primary language on your target language.

Fix: Try as hard as you can to not work from your primary language into the target language, but to work from the structures, set phrases, and grammar within the target language that you know first.

Mistake 6: The Secret Language Learners Don't Want You To Know...

...is that there is no one easy method. You are not going to learn French while you sleep, or master Korean by doing this one easy trick. Learning a language requires work and dedication, the people that succeed are those that push through the boredom of repetition and failure. The "I learned X in 1 year/month/week/day!" crowd is hiding large asterisks, be it their actual level, the assistance and free time available to them, "well actually I had already studied this for 4 years", or just straight-up lying. Our own journeys in our native tongue were not easy, they required years and years of constant immersion and instruction. While we are now older and wiser people that can make quick connections, we are also burdened with things like "jobs", "house work", "school work", and the digital black hole that is "social media" that take up our time and energy. Everything above is to help make this journey a little bit easier, quicker, and painless, but it will never be magic.

I find that language learning has a lot in common with the fitness community. People will talk about the workout that changed their life and how no other one will do the same—and it really can be the truth that it changed their life and that they feel it is the ultimate way. The real workout that will change your life is the one you're most consistent with, that you enjoy the most. Language learning is just trying to find the brain exercise that you can be the most consistent with.

Fix: Save your energy looking for shortcuts, and do the work, fail, and come back for more. If someone tells you that you can become fluent in a ridiculously short amount of time, they are selling you a fantasy (and likely a product). You get out what you put in.

For those that made it to the end, here are some of my "universal resources":

Refold Method: I don't agree with their actual method 100%, but they've collected a lot of great resources for learning languages. I've found their Chinese and Korean discords to also be really helpful and provided even more resources than what's given in their starter guides.

Language Reactor: Very useful, and have recently added podcasts as a material! The free version is honestly all you need.

Anki: If I do not mention it, the people with 4+ year streaks with a 5K word deck will not let me forget it. It can be used on desktop or on your phone as an app. If you need a replacement for a language learning app, this is one of them. Justin Sung has a lot of great info on how to best utilize Anki (as does Refold). It's not my favorite, but it could be yours!

LingQ: "But I thought you said language apps are bad!" In isolation, yes. Sorry for the clickbait. This one is pretty good, and more interested in immersing you in the language than selling a subscription to allow you to freeze your streak so the number goes up.

Grammar Textbooks: For self-taught learning, these are going to be the best resource since it's focused on the hardest part of the language, and only that. If you're tired of seeing group work activities, look for a textbook that is just on grammar (Modern Mandarin Chinese Grammar is my rec for Chinese, and A Guide to Japanese Grammar by Tae Kim is the most common/enthusiastic rec I've heard for Japanese).

Shadowing: Simply repeat what you hear. Matt vs Japan talks about his setup here for optimized shadowing (which you can probably build for a lot cheaper now), but it can also just be you watching a video and pausing to repeat after each sentence or near simultaneously if you're able.

Youtube: Be it "Short Story for Beginners", "How to use X", "250 Essential Phrases", or a GRWM in your target language, Youtube is the best. Sometimes you have to dig to find what works for you, but I imagine there is something for everyone at every level. (Pro tip: People upload textbook audio dialogues often, you don't even have to buy the textbook to be able to learn from it!)

A Friend: Be it a fellow learner, or someone who has already mastered the language, it is easier when you have someone, not only to speak to, but to remind you why you're doing this. I write far more in Chinese because I have friends I can text in Chinese.

Pen and Paper: Study after study, writing on paper continues to be the best method for memorization. Typing or using a pen and tablet still can't compare to traditional methods.

The Replies (Probably): Lots of people were happy to give alternatives for specific languages in the replies of my DL post. The community here is pretty active, so if this post blows up at least 20% of what the last one did, you might be able to find some great stuff in the replies and reblogs.

I wish you all the best~

508 notes

·

View notes

Text

A 5200-year-old pottery bowl from Shahr-e Sukhteh bearing what could possibly be the world's oldest example of animation. It shows 5 images of a wild goat leaping, and if you put them in a sequence (like a flip book), the wild goat leaps to nip leaves off a tree. Museum of Ancient Iran

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

3:8 They shall not profit thee; and there is no fundamental difference between "procedures" and "data"

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Diagrams and symbols are compelling. As a child I bought a copy of a Giles Milton book because it had heraldry in it. Maps are serious diagrams for grown ups. Every line on a map tells three stories, of the one who drew it, of the thing it constructs, and of the thing it represents. Esotericism is compelling because it promises that there's something serious behind the diagram. (Sometimes we want a seriousness behind the world, and sometimes we don't think there is but we find people who believe in this seriousness interesting.) And diagrams, by their very nature, hide things. So there is an assumption that there's always more. Can the language of pointing be applied to diagrams? See the Panizzi lectures.

Etel Adnan

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Cf. Feyerabend as a child]

It’s weird to grow up in a family where you know you’re loved but you don’t feel loved. And then later in adulthood you understand how almost impossible it seems to cross that distance and let yourself experience closeness, how otherworldly love feels now and how love feels unbearable at times. You flinch when someone tries to wholeheartedly love you. And over and over you see so clearly how you cannot be loved unless it's from afar and love is mixed with that familiar sensation of distance and coldness.

65K notes

·

View notes

Text

[Different sense of knowledge; what we miss out when we focus on embodiment and the sense; cf. Serres.]

85K notes

·

View notes

Text

[Cf. Byung-chul Han on how the master-slave dialectic has been combined and internalised.]

Cain by José Saramago translation by Margaret Jull Costa

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

said the Daoist bureaucrat

or I guess Jing Fang 京房 could have said it

my lord what are these? constants?

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Katsushika Hokusai (Japanese, Tokyo (Edo) 1760–1849)

via

1K notes

·

View notes