Text

Ta-daa!! body psalms by Audrey Gidman is now available for preorder!

Readers, our lovely newest chapbook and winner of the Slate Roof Press Elyse Wolf Award, is just about to be released. "This is a collection of incantations, meditations, conjurings, 'a bowl of water on the ground…a bowl catching grief like rainwater,'" declares poet Lisa C. Taylor. Take a look at the sample poem below and see more at http://www.slateroofpress.com/books/body-psalms.html

$17 + shipping, Letterpress Cover, Original cyanotype by Linda Clark Johnson, Handsewn Binding

0 notes

Text

Word photos and the language of embodied experience: Susan Glass talks about her new chapbook, The Wild Language of Deer

Susan Glass is our blogger with interviews of fellow poets, literary journeys, and all things poetical. However, for this blog, Susan herself is interviewed by Slate Roof Press Managing Editor Janet MacFadyen in celebration of The Wild Language of Deer, winner of the Elyse Wolf Prize and just released this month.

Susan Glass's poetry has appeared in Snowy Egret, The Broad River Review, Birdland Journal, Fire and Rain: Ecopoetry of California, and elsewhere. After teaching many years at San Jose State University and West Valley Community College, she now co-edits the Blind Californian Magazine and the AABT Briefs newsletter. She and her husband John share their home with her guide dog Omni, whose combined work ethic and silliness ensure that all three remain irreverent, active, and loved.

J M: Can you tell us a bit about The Wild Language of Deer? What moved you to create this particular grouping of poems for a chapbook?

S G: I had recently retired and was searching through my poetry trying to see if it was any good, was there any continuity? What I found was I had poetry of the natural world, poetry of family, poetry of music. And I thought, let's just put this out there and see what happens, and then my friend Julie said, You have to do this. At that point I didn't know that the poetry of origin and theology was going to come in until we began working together as Slate Roof poets. One thing I have learned is that I had been hiding behind playfulness and cleverness, and they're OK, but I'm deeper, more tectonic than that.

J M: How do you write poetry? When you start writing, what comes first — the words? A sound or smell?

S G: I don't think my poems ever originate in a cerebral place. There are poets who can pick up an item from a news story, and zip! they have something. I can do that, but it starts in my corporeal sensory mammal body first, through ears or nose or fingertips. One of the reasons I'm afraid to die is because I can't imagine being disembodied. I love my body, I love the earth, I love whatever's going on down here.

My poems start in my corporeal sensory mammal body first, through ears or nose or fingertips.

J M: And you try to capture that in your poems?

S G: Yes, my early drafts are often about photographing and preserving sensory experiences and memories, so I think of my poems as "word photos," trying to create the holographic, sensory fullness of an experience in the physical world. Our sensory memories grow dull as we move away in time from them, a sign of mortality I fight through sounds — both animal and linguistic — and through poetry.

For example "A Cellist Brings Me Autumn" came after hearing a cellist during a walk on the last hot night in September. Hearing that melodic sadness, the cello's timbre — low, warm as embracing arms — conjured up the feeling of summer's end, of back to school boundaries, security, and uncertainty. I wrote to capture/photograph/record the present experience and its resonance with the past one, weaving the two experiences together in a sound picture. The music, the warm night, my guide dog Zeus, prompted the feeling, which prompted the memories, which prompted the need to create the poem.

J M: But the poems morph into something much larger, don't they?

S G: Oh yes, as I write a poem I discover it has tectonics, layers, darker places within its rock. Those places are my undiscovered country. So take "Mother Sews My Dress" which I wrote during an indolent summer afternoon in Lincoln, Nebraska. Mama fully inhabited our summer afternoon dining room with all her sewing apparatus; I was remembering the whir of her Singer sewing machine, the discarded spools and pin cushions on the dining table, and her voice followed by the feel of pins scratching my legs and her yard stick bumping them where she knelt to hem the dress.

I wanted to capture this experience as a word photo, but later talking with my sister, I saw the ambivalence that surrounded Mama's sewing, how much it was also about stitching together her daughters' lives, sewing them up straight and strong, but also safe. She was fierce about our being safe, terrified of what men and sex could do to us, because of what they'd done to her. But all her needlework couldn't protect us from ourselves or from the world.

J M: The natural world figures prominently in your work. How would you describe your relationship to the trees, the birds, and horses and dogs that populate these poems?

S G: The natural world was my first teacher. It spoke in the languages of the senses, and the language of embodied experience. First came the tongue of wind in trees, of our beagle Happy scrambling under my crib and licking my feet under the high chair. I thought morning came because birds called it, and I thought the wind bullied the trees although I didn't know the word "bullied."

When I learned to talk, the loving people in my life showed me more about my Natural World teacher and gave me words that connected us all. Yet people came and went, appeared and disappeared, but the language of my senses was always there. Dogs and horses and birds and trees were always within reach of one sense or another. Flickers and wrens and towhees oriented me to space and distance, and introduced me to music. Trees and horses taught me about the power of my own body, of motion, of gravity, and of absolute stillness.

I thought morning came because birds called it, and I thought the wind bullied the trees.

J M: Your connection to other creatures is one of the most intense and moving experiences I have in reading your poetry — for example, the poems about your guide dogs and horses.

S G: Yes, the dogs in these poems, Jonca and Zeus, are two of my four guide dogs. The relationship with a guide dog is deep, and mammalian and abiding, a truly joined-at-the-hip thing. And horses were my first freedom. I rode them before I learned to walk with a cane. I rode them before my adolescent sexuality made me afraid to be myself. Now at age 65, horses are helping me reclaim the strength of my pre-adolescent self, along with the power that such reclamation brings with it.

J M: Various Norse/Scandinavian myths and motifs appear in chapbook. Can you talk about how they weave back and forth in your writing?

S G: These connections surprised me as I wrote the book. I have [Slate Roof member] Audrey Gidman to thank for them. When we were first discussing an early draft of "Deer," she asked for more mythical references.

J M: I remember that!

S M: So I began exploring, and here came Artemis avenging the death of a murdered buck. And then you shared your vision of the deer's head mounted over the mantle, severed from its body and furious.

J M: Oh, yes…

S G: What an insight your words gave me into my own fury, fury at being separated from my own wild voice; fury and rage at being silenced, at having my body renamed and exploited and violated, at the equal violation of the natural world, at separation from female strength, and from the ongoing, wild strength that is Earth, and so far as we know, our only home. And the myths are all origin myths, they're really old. But I was raised Lutheran, so there's this backbone of faith and fear in me that insists on finding something theological with which I can live. In fact, I think several of these poems are theological, which is to say they are endeavoring to create their own theology.

J M: Can you expand on that?

S G: Sure. "June Bedtime Story" [scroll down to previous blog to read this poem] is the child speaker's first exploration of god: no capital G here. Is god the mother-lap? The snips, the trowel? Is god the mother hands, earth gloved and honest? Most terrifying of all, is god the seed grave? Must we bury ourselves in darkness in order to emerge as flowers? How are we born? How do we die? Why is there so little separation between the two? Bingo! Here is the beginning of a personal theology.

So the child speaker experiencing all of these questions and feelings doesn't yet have language for them. She turns to the language she knows: the language of her senses, especially her ears, with their wild stirrups beating inside of them, and the wild sound that they bring. And she turns to the language of her mother's body, its sounds as she moves. Later I used to just follow my mother around and ask her how was I born, what happened?

Other poems in my book, "Time Is A Guest Here Also," "Word Photos," and "Dusk Waking," are also theological poems. All three speak in the language of dreams and from a dreamscape, and what are dreams if not part of the natural wildness, the mystery of being?

J M: What is it like as a blind person to have this hybrid sighted-braille chapbook of your poems?

S G: It is so exhilarating! Braille for all its fascinations to everybody tends to produce one kind of book: books that are larger and are read quite linearly. There is such a thing as graphics, but what artist Hyde Meissner did in my book with color, form, and dimensionality doesn't usually happen with Braille. So what our Slate Roof printer, Ed Rayer, and Hyde have done here, and what Slate Roof Press has done, is to weave the artistic part of Braille into the physicality of the book. Which matters a great deal to me because now Braille has found an artistic form and voice, along with the words and pictures and sounds when you read the book.

I am really excited at how this book speaks to both people who can see and to people who don't about the physical nature of words and they way feed back to what we hear, what we touch, and what we smell. Blindness does not deprive you of sensory richness; it simply adds a new dimension.

Ed and Hyde brought physical magic to this book, and what you did as Managing Editor and the minds and time of everyone in Slate Roof helped shape the content. This is one more demonstration for me of how we are part of a human anthology, and how no single talent ever matches the beauty when many talents from many people come together.

Go here to order: The Wild Language of Deer: Chapbook with letterpress cover, Braille fold-out poem, original woodcuts by Hyde Meissner, hand-sewn binding with special die-cut binding. $17.00 + shipping.

0 notes

Text

Ta-daa!! The Wild Language of Deer by Susan Glass now available for preorder!

Readers, our lovely newest chapbook is forthcoming this fall. Winner of the Slate Roof Press Chapbook Award, The Wild Language of Deer reveals an impassioned sense of belonging, both to the world of here and now, but also to a fluid, echoing, mythical world out of time. Out of these pages come the stamping deer, the singing birds, the fingertips running over Braille and flute keys.

Chapbook with letterpress cover, original woodcuts by Hyde Meissner, hand-sewn binding with special die-cut binding. $17.00 + shipping. http://www.slateroofpress.com/books/the-wild-language-of-deer.html

Lucille Lang Day, author of Birds of San Pancho and Other Poems of Place, coeditor of Fire and Rain: Ecopoetry of California, describes Susan Glass’ work as waking up “all the senses with a feast of intriguing textures, scents, flavors, sounds, and visual images.” Here’s a sample poem: June Bedtime Story In the wild light before cataracts, God was marigold seed sprouting from between Mother’s fingers. My first nursery to water and smell. Together we tamped the earth, our forearms and knees touching. She stood, and I—child god at ear level with patchwork knees— listened to a wheelbarrow on stone, pulled by Mother hands, earth-gloved and honest, the flapping burlap apron of Mother lap, the snips, the trowel. God became dwarf plants, and plastic six-packs, and spider-web roots clinging. And the seedlings begat evening, smelling of onions. I crouched in the basin our knees had made, unsure how seed graves could spawn life, afraid of leaving them to their dark work, afraid of running away.

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

The Poetry of Addiction: A reading from Writing From the Broken Places, July 11, 2 PM

Join us for an online celebration of Writing From the Broken Places, an essential poetry anthology written by people at the Northern Hope Recovery Center in Greenfield, MA. Inside you will find a testament to the dignity and struggle of those in recovery—and the courage of writers who write to live. Mentored & compiled by Slate Roof Press alum Jim Bell.

Register to join here: https://us02web.zoom.us/meeting/register/tZEqf-qurTwpGtI-2pojRdy77y-Jeih9RLsj

$17 + shipping. To order go to http://slateroofpress.com/books/writing-from-the-broken-places.html $3 of every book sale will be donated to the North Quabbin Recovery Center https://www.nqcc.org/nqrc.html

“The poems…rage and wrench yet produce, with profound clarity, hope and light, “hard to walk towards it/ but damn it it’s beautiful”’… -- Lauren Marie Schmidt

“The writings are powerful and insightful, … a resource for those whose loved ones have been ravaged by addiction. --John A. Jones, Chief Probation Officer, Orange MA. District Court”

Huge thanks to the Greenfield Cultural Council, a local agency supported by the Massachusetts Cultural Council, for a grant that made this book possible!

0 notes

Text

Reading and Craft Talk Monday, April 12, 7:30 pm.

Join us for a reading by Glass Prize winners Jendi Reiter and Armen Davoudian, followed by a craft talk by master printer Ed Rayher and artist J. Hyde Meissner. The evening closes with an audience Q&A. To register go to https://us02web.zoom.us/meeting/register/tZElcOurqTkoEtGVKMvNLQUk6xnO6-bg3Vpa

0 notes

Text

Myth, Sonnets, and Immigration: Susan Glass Interviews Broadside Winner Armen Davoudian

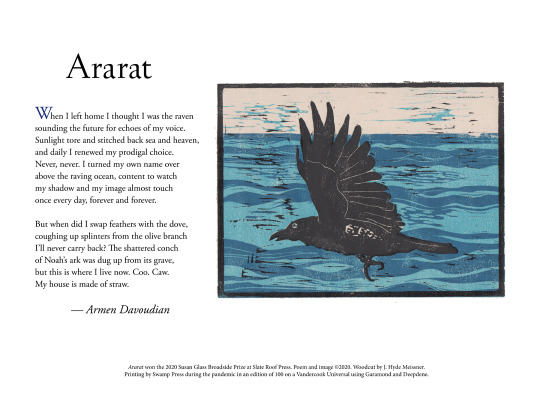

Susan Glass is our blogger with interviews of fellow poets, literary journeys, and all things poetical. In this blog post, she talks with Armen Davoudian, who won the 2019 Slate Roof Glass Poetry Broadside Prize for his poem "Ararat."

Armen Davoudian is the author of Swan Song, which won the 2020 Frost Place Chapbook Competition. His poems and translations from Persian appear in AGNI, The Sewanee Review, The Yale Review, and elsewhere. He grew up in Isfahan, Iran and is currently a PhD candidate in English at Stanford University.

S G: Thank you for talking with me today. In “Ararat,” I hear and read a recurring theme in your poetry, the tensions between a myth and its various retellings, or between a myth and a reality — tensions underscored by parallel tensions within a speaker. In "Ararat," we have the tensions between the raven and the dove, and a shadow and an image almost touching. There's also the dove's olive branch that splinters, and can never be carried back.

It's hard to return home after absence, to find ourselves or our homes exactly as they were before we left. Were you thinking about these tensions when you wrote "Ararat," and how they play out in your homeland and in your life?

A D: Thanks for commenting on the tension between myth and reality. Ararat, the mountain, is an important symbol in Armenia, and for Armenians. I am ethnically Armenian, so it's been a present image since childhood. The mountain itself used to be in Armenian soil, but now it's in Turkey. So there's symbolism and tension around it. Ararat is traditionally seen as the place where Noah's ark landed. I've always been interested in that story and the story of the flood as a kind of allegory for immigration. We leave one world behind, and wash up on the shores of a new world.

Purchase the broadside "Ararat" at http://slateroofpress.com/contest2019b.html#poems

S G: The speaker in "Ararat" identifies as "prodigal."

A D: Right. The Prodigal Son is another Biblical story, and in that story he does go back home and is accepted with open arms. But maybe that's one of the tensions between reality and myth. In the real world you never really can go back. The place has changed and you have changed.

S G: "Ararat" is a sonnet, as is "Black Garlic," the poem that opens Swan Song (see https://bullcitypress.com/product/swan-song-by-armen-davoudian/).You handle the sonnet form with flexibility, and delightfully surprising word arrangements. What intrigues you about the sonnet?

A D: I find poetic forms musically appealing. With the sonnet, there's an asymmetry between its two unequal halves that attracts me. The sonnet was a courtly love poem that originated in the 13th century. But I feel that it's perfectly suited for the story of immigration and displacement because of that division in the middle. There's also a long tradition of the political sonnet going back to Milton. I'm interested in how this tiny form can fit such huge personal and political subjects within itself. Big ideas and feelings in a small package.

S G: Yes. It welcomes and forces our attention on to the issues at hand because of that paradox.

A D: I think so. One of the distinguishing characteristics of poetry is its brevity, and brevity as possibility. It's not a shortcoming, it's a possibility. Brevity allows you to do different things. It's transferable. It's portable. You can hold it in your mind and in your mouth. You can't memorize a whole novel, but you can memorize an entire sonnet.

S G: What you are saying about the power of a sonnet's brevity reminds me of how Seamus Heaney could take the immensity of the sectarian violence happening in Ireland, and fit it into the tiny sonnet form.

A D: Heaney’s sonnet sequences have been really important to me. I admire how he fits a family story, the sequence about his mother, for instance, into this tiny form. And I like the way he fits food into his work, the way food is so sensual for him, like his references to oysters and potatoes — pregnant with meaning, but in a way that doesn't cancel out its physical properties. You can still taste it even though it stands in for a whole range of meanings.

S G: Attention to food comes through in your work too. I'm thinking about "Wake-up Call," and the tender attention you pay to tea-making, and breakfast preparation, and the speaker who is both present and yet absent. I feel as I read this poem, a lifelong homesickness, longing, tenderness.

A D: Thank you.

S G: I know that you are a fluent speaker, reader, and writer of Persian, Armenian, and English. This allows you access to a plethora of images, metaphors, and mindsets. In which language do you compose? Dream? Are some of your poems better suited for one language than for another?

A D: I grew up in a small, diasporic Armenian community in Iran, so I learned Armenian first, even though the language of instruction in school was Persian. And I learned to read and write in both Armenian and Persian. But now I write exclusively in English. I also translate from Persian, and more recently from Armenian. I'm visiting my parents in Los Angeles right now, and here I speak Armenian. Persian has become an almost exclusively literary language for me, and these days I only read it or write it. So I sometimes feel out of touch with it as a living language. I'm comfortable living in and with English now, though I occasionally must think about what is the correct preposition (at college, on campus). But I think it helps sometimes to be a little alienated from what you love, or from the tools you're working with. It helps sometimes to see them as an outsider.

S G: So as you move through your daily life, what language are your thoughts in?

A D: Mostly in English. I'm in grad school, so I'm thinking about grad school stuff. But if I'm cooking a Persian meal, I'm thinking about the ingredients and the recipe and the preparation in Persian. And if I'm remembering something my granddad said, that will be in Armenian.

S G: Several of your poems address political strife using direct, emotionally engaging language that insists we pay attention. You make us feel what too many news blasts and too much information would rather smother. I'm thinking of your lament about former president Trump and the many children stranded at the U.S. Mexican border. You write: "they are wrapping them in Mylar / and putting them to sleep where they used to house ammo." Then you juxtapose the word "ammo" to a mother calling, "te amo, te amo." You make what's political human. How important is this to your writing, and does it figure in your current projects?

A D: Thank you for asking that. We live in a time of bombardment and desensitization. You read these things in the news and at some point they stop moving you. But I don't think this applies to political realities only. When I think of one of my favorite people ever, my grandfather, and the fact that he's dead, I can say that and it doesn't stir any kind of emotional response in me, until I put it in a poem that does excite emotion. So I think that's how I feel about the political reality too. Unless you're in it, it's distant. I feel like it's our job as writers to make it present and make people feel it. One of the ways that I try to do that is by pointing out those weird linguistic coincidences (“ammo” and “te amo”). We have this tender confession of love on a mother's part, and the exact opposite in that "ammo."

S G: I listened on YouTube to a presentation called “Don't Look Away,” a literary series sponsored by the International Armenian Literary Alliance. You participated as a reader. I imagine you are actively involved? Can you share a bit about the organization and its work?

A D: Yes, I’m a member of IALA. It was founded recently as an organization for Armenian writers throughout the world, of which there are many, because the Armenian diaspora is huge. A lot of Armenian writers live outside of Armenia, and it's been a great way to connect with them. They offer a mentorship program for younger Armenian writers, too.

S G: Would you like to talk a bit about the work that you are doing at Stanford? Are you writing? Are you teaching? What is it like to balance your writing and your studies?

A D: I'm doing a PhD in English that does involve teaching. I'm studying modern poetry in English mostly, and I'm writing my dissertation on a literary device called metanoia, which means self-correction. It's a rhetorical term for what some poets do where they'll say one thing, and then retract it, or rephrase it. It can be something as simple as writing "the sky is light blue," and then writing, "no, it's dark blue." But instead of deleting one of these assertions, you keep both of them in the poem. This doesn't happen just on a lexical level. It happens more generally when poets doubt themselves or second guess themselves.

And I find this happens to me as I write poetry. I tend to have a hard time making my mind up about things. So much in the world is ambivalent or ambiguous, and I want to know things clearly as I write, but of course that can't always happen. So in some ways, studying this device, metanoia, has been helpful. It helps to know how other poets handle this problem of trying to write out of uncertainty.

S G: Yes. We'd like to be able to move as we write from uncertainty to certainty. But too often it feels as though we are writing into deeper uncertainty.

A D: One poet whose work I've studied intensively who I think exemplifies this self-doubt is Elizabeth Bishop. Bishop is often seen as this poet who made perfect little lyric poems. But I don't think we have truly grasped how loose and free and prosaic they are.

S G: You are reminding me of her poem, "Manners."

A D: Yes. She and her grandfather are riding in a horse-drawn wagon, and her grandfather says that she must say hello to everyone they pass. It’s the polite thing to do, even though I think that as a lesbian writer, she would have a lot to disagree with in terms of what is “mannerly” to do and what isn't, what is accepted and what isn't. But at the same time, she sees her grandfather's manners as one of the ways he manages to be nice to people, to keep his footing in the world. But she feels really divided about it, and the poems issue from that sense of division, and self-division. That's been instructive for me.

S G: Yes. That speaks to your work. I'm thinking particularly of your poem, "Coming Out of the Shower." It's a poem rich in double meaning ("mama, I'm coming out") as in coming out of the shower and coming out as a gay man. But I also love its sensory richness, and how the speaker says that he's using his mother's shampoo, and will smell like her for the rest of the day.

A D: I use Dr. Bronner’s shampoo usually, which smells like mint. But at some point it just starts smelling like nothing because you get used to it. Other people may smell it on you, but you can’t — not anymore. So using someone else’s shampoo is suddenly a shock to this senselessness. It's almost a perfect metaphor for poetry, how we get used to the world and to language, to the point where they cease to move us, until and unless a poem shakes us out of it

S G: Are you teaching right now?

A D: I'm putting together a proposal for a course next year on the sonnet. I'm excited about that. I want us to look at the form from Petrarch to Terrance Hayes. I'm interested in how the sonnet has survived many centuries to work so well today.

S G: Can you describe your own writing process and your writing space?

A D: I've moved so often — I guess that's part of being a graduate student. I try not to attach myself to a particular place or desk or chair. I don't want to feel like I have to wear a certain pair of pants in order to write. I try to write every day, first thing in the morning, for 2 hours, with coffee. I have a set of books that I keep with me, Seamus Heaney's books among them. When I get stuck, I read a poem by someone whose work I admire, and the flow usually starts again. Some, like Gertrude Stein, are experimental poets and writers who provoke me. I don't write like they do, but they help me get started. They make language opaque again. I notice it again. It's there to be worked with and through.

S G: Whose work do you enjoy reading?

A D: I think I became sure that I wanted to be a writer when I read Proust, first in Persian and then in English. I appreciate his sense of the importance of memory to life. I also gain from him a sense of what an artist's life looks like. I appreciate the importance of erotic tension in his work – desire, love, jealousy. For similar reasons I am drawn to James Merrill's poetry, his love of form, music, memory, and childhood. Then there is the poetry in Persian. The Asian American Writers’ Workshop recently compiled a list of 100 works of Persian literature in English (https://aaww.org/100-essential-books-by-iranian-writers-poetry-hybrid-works-anthologies/). I've always wanted to teach a course on the poetry of exile, so I read poets whose work addresses that.

S G: What are you working on now?

A D: I'm working on my first full-length book of poems. It starts with a crown of sonnets called “The Ring.” My dad had to get his wedding ring re-sized, but he ended up buying a new ring and he gave me the old one. The sequence is about that exchange, that passing down of a memento, and what that means since I probably won't have the kind of traditional marriage that ring was made for.

S G: Has it been challenging or ambivalent or tender to talk to your mom and your dad about being gay?

A D: Yes. They had such a different upbringing in a different place, but still they've been very loving and open. Sometimes I feel like it's taken away one of the tensions that used to drive my poetry!

S G: Will some of the poems from Swan Song find their way into your new book?

A D: About ten of them will. This new book has two long sequences of sonnets, so I'm hesitant to put in any more.

S G: Thank you so much for talking with me today. Is there anything I haven't addressed that you'd like to talk about.

A D: Just thank you so much for the beautiful broadside! My parents were really happy to have it. My mom has framed one and it's in their living room. Thank you for this conversation.

S G: Thank you! I look forward to hearing you read on April 12.

0 notes

Text

Honoring Nature: new Authors and Artists Festival returned for a second year

There were so many insightful, provocative, compelling speakers at February’s Authors and Artists Festival: Honoring Nature. The festival focused on nature and the ecological crisis, with keynote speakers Sherri Mitchell, Scott Russell Sanders, G.A. Bradshaw, Joan Mallof, Christian McEwen, Susan Cerulean, Deb Habib, Simon Wilson, and Patrick Curry. View SRP poets Susan Glass, Janet MacFadyen, Anna M. Warrock and Richard Wollman reading with Cheryl Savageau and Leo Hwang at https://youtu.be/f8aAZo1wBTw.

The conference also published a compelling anthology of nature writing, including work by SRP poets and alums Susan Glass, Janet MacFadyen, Anna M. Warrock, and Cindy Snow. We were honored to share space with many of the festival keynote speakers. To order the anthology, or for videos of the full conference go to https://authorsandartistsfestival.wordpress.com/

0 notes

Text

Where art, jazz, and poetry converge: Sidelines Literary & Art Magazine features SRP poet Lynn Shorter

Lynn Shorter is the winner of 2020 Slate Roof Press Chapbook Award/Elyse Wolf Prize with her first chapbook, Singer in the Gray of Jean-Michel. As a senior lecturer in England from 2008-2020, she taught non-traditional students and co-founded Reading the World, a creative writing and performance project for marginalized groups and artists.

Your poetry clearly takes influence from Basquiat. What about him or his art sparks the feeling of writing in you? What do you wish to convey by using him in your poetry?

There is so much to hear in Basquiat’s work. ‘The skulls, the masks, the head of logos-Lagos dithyramb’ is my way of describing the effect his paintings have on me. Their incredible concentration of energy perfectly captures creative impulses that have been socially circumscribed and denigrated while simultaneously unleashing their power.

The way you form your poetry is fascinating and unique. What draws you to use such a fluid style instead of working with more traditional or structured conventions?

While I draw on Greek and Inuit archetypes in Singer in the Gray of Jean-Michel, the chapbook that the Sidelines poems are taken from, I’m not wedded to any specific poetic forms; rather my writing is driven by what is not there when I move from inner to outer spaces where I no longer appear whole or wholly myself. Fluidity here is integral to poem making and well-being.

Or perhaps what you’re asking has to do with how one metabolizes sound (and its absence).

Jazz seems to be a common theme in your writing--whether it be mentioned or reflected in your stylistic choices. What influence has this genre had in your writing career and is there a musician in particular (you mention Monk quite a bit) that piques your interest or jazz as a whole and why??

In Singer in the Gray of Jean-Michel, Rafael Rafaela, the singer/speaker, is immersed in a Jazz inflected universe which gives her ease of access to multiple layers of consciousness. In the five poems that follow, Joseph Jarman, Lester Young, Thelonious Monk, and John Coltrane are referenced as indeed is Ornette Coleman who is Rafael Rafaela’s primary source of inspiration.

My aspirations in the piece are to move imaginatively and again fluidly in and out of time and inside, outside and across the charged terrain of North American oral geography to tell the story that I need to tell with Jazz, the world’s foremost planetary and galactic citizen, as my guide.

What does writing poetry mean to you? Does it allow you to escape into another world or is it more of a cathartic experience to understand your life and what is going on around you?

It is to smolder and burst into an ancient to new continuity of possibility for a fractured world.

What phrase, experience, author, book etc. has had a long-lasting impact on your career??

Albert Murray’s phrase ‘velocity of celebration’.

See the fall 2020 Sidelines issue and Lynn’s poetry here: https://sidelinesmagazine.wordpress.com/blog/fall-2020-magazine/

0 notes

Text

Red Maple Leaves and Gold Ink: Susan Glass interviews artist Elyse Wolf

Susan Glass is our monthly blogger with interviews of fellow poets, literary journeys, and all things poetical.

In a stroke of wonderful serendipity, Elyse Wolf has been our yearly chapbook contest sponsor since 2016. Thanks to her, we have been able to offer a purse with our contest, something that a very small volunteer press like ourselves would never have been able to do otherwise. It is a joy to be able to compensate the winning poet, in a world where writers rarely receive financial support for their work. And it's a joy to have a link to the broader visual arts world in our connection with Elyse.

An artist working in colored pencil and pastels, Elyse is a signature member and five-year Merit Award recipient of the Colored Pencil Society of America. She has studied under Morris Kantor, Theodoros Stamos, William Christenberry, and Brockie Stevenson, and her artwork has appeared in the Susan K. Black Blossom Two-Year Museum Traveling show, the John Pence Gallery in San Francisco, the Salmagundi Club and The National Arts Club in New York City, the Corcoran Museum Biennial, numerous CPSA International shows, The Art League in Alexandria, VA, and The Troika Gallery in Easton, MD. Her work also has been included in Blossom II Art of Flowers, The CPSA Signature Showcase, The Best of Colored Pencil, American Artist Magazine, and The Artist’s Magazine. Learn more at Elyse Wolf Fine Arts: www.elysewolf.com.

S G: We feel so lucky to have your support. How did you become interested in Slate Roof Press, and in helping sponsor our poets with your prize?

E W: I became interested in Slate Roof Press because of my friendship with Anna Warrock, one of SRP's poets. I'm so impressed by the quality of the poetry and by Ed Rayher's masterful sense of design and dedication to excellence that goes into all of SRP's publications. I'm not a poet, I'm a visual artist, but I think all the arts are connected in some profound way, as are all artists. These days, the arts have been marginalized or dismissed as irrelevant in our society. Yet poets keep writing poems. And it's important.

Red Maple Leaves, colored pencil, 22 x 30

S G: Indeed it is. All artists have an opportunity, even a duty I think, to address the world in its fullness. And these days that fullness includes social justice, pandemics, loneliness, connection, beauty. And poets and artists learn from each other, don't they? Can you talk about the people and artists who have influenced you?

E W: I come from a family of artists and grew up in the Boston area, surrounded by art. In high school I attended after-school classes three days a week at the Museum of Fine Arts, I have a BA in art from Umass Amherst and studied at the Art Students League in New York for two years. In New York I also worked at the Frick Collection, the most exciting environment any artist could ask for. In D.C., I studied at the Corcoran Museum School.

Currently I'm working in colored pencil, and oil pastel. I was trained in classical drawing, though I've also done abstract painting. My love of Japanese art and its asymmetrical compositions shows up often (not always intentionally) in my work. There are so many amazing contemporary artists — I can't begin to say who inspires me the most so I'll mention some all-time favorite ones. For still life, Chardin, Cezanne, Redon, Charles Demuth come to mind. For landscapes, Corot, Seurat, Joan Mitchell, Wolf Kahn. Right now I'm doing landscapes in oil pastel.

Persimmon Tree, watercolor, gouache, gold ink, 22 x 40

S G: Tell me something about your work space and your creative process.

E W: I live in Washington, D.C. and belong to an artists' co-op of about 45 artists. We work in a former grade-school building, the Jackson Art Center, in Georgetown, which is a historic neighborhood in D.C. The school was built in the 1890s. It's a wonderful place to work with high ceilings, tall windows, lots of light and views of Montrose Park across the street. Dumbarton Oaks is further up the block. I try to get to my studio every day, even if only for an hour or so.

S G: What are you working on right now?

E W: I love working with colored pencils because I can combine my drawing skills with the rich hues and textures of colored pencils. I've been doing a series of red maple leaves. Most works are on 22" x 30" paper. In one piece, I try to capture the sense of leaves in motion, in another I concentrate on the underlying form of the branches, or combine red leaves with dragonflies on an ice blue background, or combine red maple leaves and gold ink.

To achieve the exact shade of red I want for the leaves, I might use a blend of more than 20 or 25 different colors: Tuscan Red, Scarlet Lake, Black Cherry, Vermilion, Carmine Red, Crimson Lake, Poppy, Cadmium Orange, Raspberry, Lime Peel Green, Olive Green, Sap Green, Naples Yellow, Cadmium Yellow.

I look forward to seeing who the next prize winner will be.

0 notes

Text

Announcing the 2020 Slate Roof Press Chapbook Contest / Elyse Wolf Prize! Submit your manuscript between May 31 to July 31, 2020.

1 note

·

View note

Text

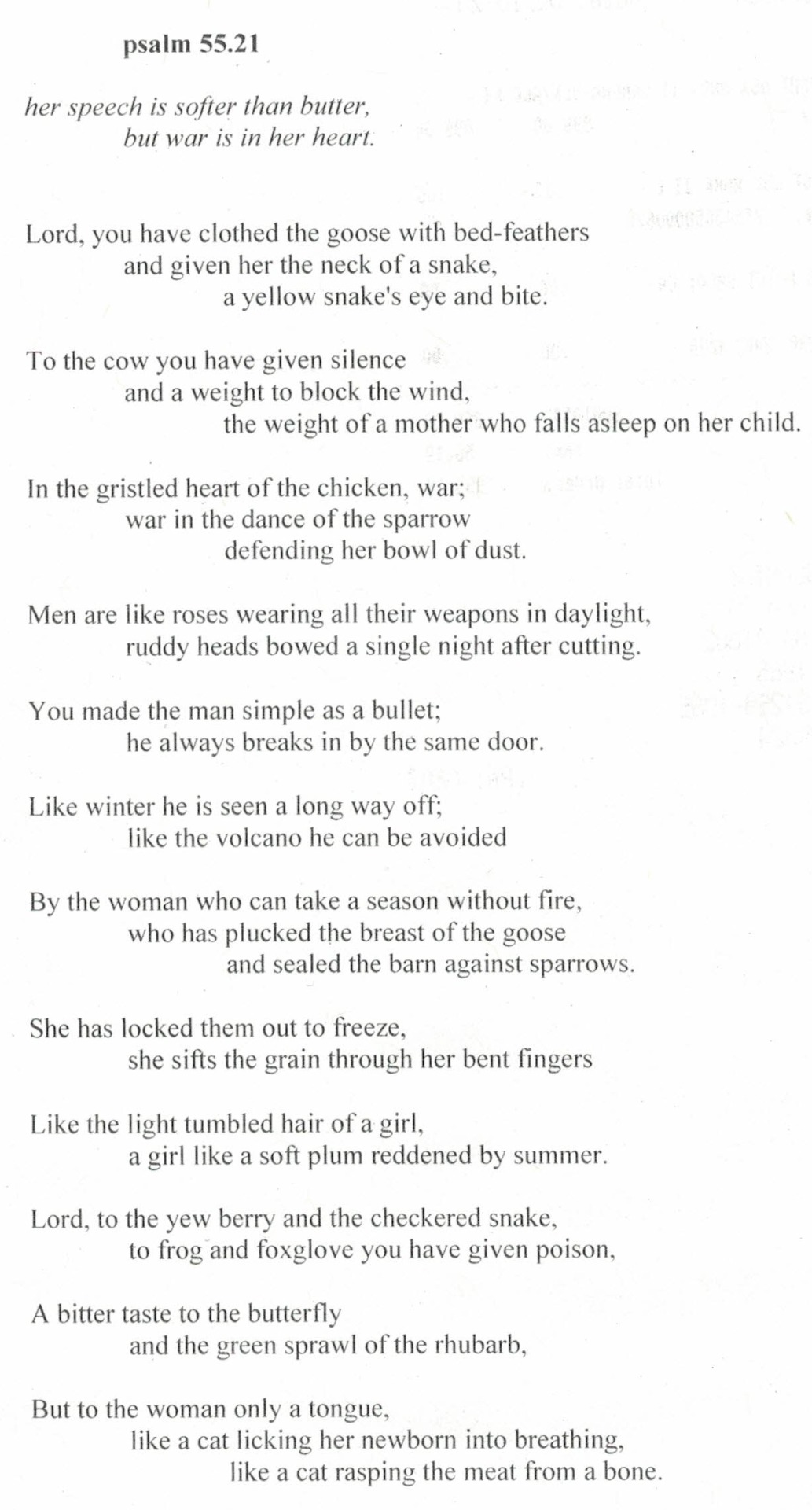

When talk is smooth as butter but war is in the heart

Susan Glass is our monthly blogger with interviews of fellow poets, literary journeys, and all things poetical.

Jendi Reiter is an award winning trans-masculine author whose books include the novel Two Natures (Saddle Road Press), the poetry collection Bullies In Love (Little Red Tree Publishing), and two poetry chapbooks: Barbie At 50 and Swallow. Their honors include a Massachusetts Cultural Council grant for poetry and short fiction, and prizes from the Iowa Review, Literal Latte, and Bayou Magazine. They are editor and Vice President of Winning Writers, an online resource site for creative writers. They are also the local winner of Slate Roof Press 2019 Glass Prize Broadside contest.

SG: I'd like to begin by asking you about the winning poem that you submitted to our Broadside contest, "Psalm 55.21.” I am struck by the direct voice, unflinching in its address to the creator, "Lord"— not so much reverent as declarative. And of course, all God's gifts herein contradict each other: the goose clothed with bed-feathers, a softness ultimately used against the goose. And the softness of this image bumps against the hard "neck of a snake," and "yellow snake's eye and bite." The cow's weight that blocks the wind is also "the weight of a mother who falls asleep on her child" — I think here of suffocation. Creation's gifts, it seems, are anything but straightforward. There's a texture in these images of brutal beauty and beautiful brutality. Is that how the images strike you? And how did you arrive at these images, and at the poem's voice that will not take any crap from the creator?

JR: At the time that I wrote this poem, I had been doing The Daily Office, which is a morning prayer in the Episcopal Prayer Book. The rhythm and imagery of various phrases from the psalms I was reading and praying stuck in my head. The voice of the psalm came naturally to me, as a "no bullshit" voice, not afraid to complain about things. Many of the psalms in which complaining happens are about intimate betrayal. The part of Psalm 55 that launched this poem was verse 12: “If an enemy were insulting me, I could endure it. If a foe were rising against me, I could hide. But it is you, a man like myself, my companion, my close friend, with whom I once enjoyed sweet fellowship in the house of God as we walked about among the worshipers.”

At the time of this poem's writing I was feeling betrayed because I had been very closely involved in Christianity and church stuff, while at the same time realizing I was more and more queer. This did not sit well with the Christian folks with whom I was associating. They had been so supportive of me during other traumatic events. And so I wondered how it was possible that these people with whom I'd shared profound spiritual experiences could also refuse to see me when the spirit was leading me to discover certain things about myself.

You'll notice that I changed the gender of the characters in this poem to female. That's because at the time, I identified as a woman, and these were female-to-female friendships. I was trying to articulate the ways in which female betrayal and female intimacy can be more subtle, more insidious, than betrayals between men. The original psalmist says, “His talk is as smooth as butter, yet war is in his heart." But I changed the pronouns to reflect the experiences I was having with my Christian women friends.

SG: You write long and short fiction as well as poetry. Do you work concurrently in these genres? Or do you find that you are composing in one while resting from the other?

JR: When I first started writing, I needed lots of concurrent projects because I didn't want to put all my eggs in one basket, and I felt I should be trying everything. Then I found, for instance, that in getting to know a character for a novel I was writing, lots of shorter pieces would emerge. Now I sometimes get so caught up in writing a novel, I need a break and want to write something I can finish in an hour or a day or a few days, rather than in 7 years. That's when some of my poems come. A lot of the poems that I've written over the past decade have been for the "30 Poems In November" challenge, an annual fundraiser for the Center for New Americans (www.cnam.org). That's a way of writing many poems, from which I winnow the good ones. Pull 7 good poems from 30 you've written, and you have the beginnings of a chapbook. So my processes for writing long and short pieces do talk to each other. Everything that's going on in my head at a given time gets into whatever genre I'm writing, so they do cross-pollinate. Some of the poems in my chapbook Swallow started as voices that were part of a character in my novel. That's one way in which hybrid texts happen.

SG. Whose poetry and fiction do you enjoy reading?

JR. Right now I'm reading Ariana Rive's A Sand Book. I've enjoyed reading her work since her first book, The Cow, came out in 2006. I think her writing is edgy and brave. I read lots of gay romance and gay literature. For fiction I like dark fantasy and dark horror. I'm also reading lots of graphic novels because Peter, my protagonist in the book on which I'm currently working, is a comic book writer. I like the British author K J Charles. She writes witty, Victorian, paranormal gay romances that have a lot to say about society and social justice.

SG. Can you describe your work space?

JR. I have to have complete silence when I work so I can hear the voices in my head. I can't listen to music when I write, but I do listen to music in preparation for writing. When I'm working out or walking down streets, I'll pick a play list that I feel would say something to the character or persona that I'm working on. My office is the top half of a converted barn behind my house. I do have my computer in my office, but I usually write in a notebook in pencil while sitting on my couch. On my ceiling is a painting of a giant orchid covered in glitter and hot pink feathers. Around me are many unread and partially read books in bookcases, 150+ Barbie dolls, several doll houses, and lots of artwork. It's a very girly office for someone who is now trans-masculine, but I love it. It's flamboyant and suits my personality.

0 notes

Link

“ All of us volunteer our time to edit, produce, and promote the books...We have gluing parties, and sewing and assembly parties.... Each member takes on a different role in the press, but oftentimes they develop that role. For example, one of our members is blind, and thanks to her we now offer both audio books and books in braille.... We have no blueprint or strategic agenda, so anyone's ideas can be put on the table during the meetings. “

Keep an eye out for our forthcoming book by Amanda Lou Doster, Everything Begins Somewhere!

0 notes

Text

Shape-Shifting Memory: Susan Glass Interviews Catherine Stearns

Susan Glass is our monthly blogger with interviews of fellow poets, literary journeys, and all thing poetical.

Catherine Stearns' chapbook Then & Again (2018 Slate Roof Press) won the Slate Roof 2016 chapbook contest; and her first book, The Transparency of Skin (New Rivers Press), won the Minnesota Voices Project Prize. She has received grants and awards from the Iowa Arts Council, the Loft-McKnight Foundation, The Dana Award, and the Massachusetts Cultural Council. Her poems have been anthologized in writing by American women abroad (New Rivers Press) and in a collection of British and American poetry (Swallow Press). She has recent poems in Poetry Daily, CALYX, New Ohio Review, and The Yale Review. She is writer-in-residence at Roxbury Latin School in West Roxbury.

SG: I’d like to begin this interview by asking you about the poem “Strawberry” because it opens this book about memory—re-turning, re-membering, re-making. I appreciate how you place the berry alongside the life cycle of “ploughgirl,” then “wife,” then “the old harvester herself.” This is the first poem in a book about life cycles. Was this your intention, or did you compose the poem as a solo piece?

CS: I wrote “Strawberry” as a solo piece. Poems come as they come, and I’m always exceedingly grateful for that initial spark and follow it with excitement if bewilderment about where we’re going! But sequencing the poems in a manuscript is another kettle of fish, as my mother would have said…. I’ve rarely had the sense of a shorter poem waiting to be part of a longer poem, or of a single poem as part of a series. When I have, it’s humbling to see where I’d been heading all along. Intuitions are so often interleaved with other emotions. “Strawberry” is about life cycles, to be sure, but I didn’t have its function as an introductory poem for the manuscript in mind when I wrote it. The poem is about language and naming, too. I’m always interested in how language can not only express but enact an internal quality of experience. Anyway, I’ve come now to look back at the poems in Then & Again, some of which had been around in various states for a long time, almost as collections or assemblages, where different parts of the self can finally come together, open into one another. Maybe threading “berry after berry” is akin to threading memories.

SG: Your poem “Sunday Drives” caused me to think a lot about why we remember what we remember, and whether during any one moment of living, we are conscious that the moment we inhabit is one we’ll remember later. I don’t have a specific questions here, Kate, but I’m wondering if you think we ultimately have any conscious control over what we remember?

CS: I doubt it because memory itself is so shape-shifting! Those neural pathways change every time we remember anything, as I understand it. But I do think that the language of memory expands outwardly, albeit slowly, as when we try to really imagine the presentness of the past or connect past and present selves. Both of which include conscious work, of course. My husband is always telling me about these on-going conversations he has with the teenager he used

to be—just to keep it real, he says. I think I have gone back in a similar way to my childhood, to that girl playing with her sisters with such remembered intensity. I’m aware of trying to make the kind of expansive connections I believe you’re talking about, connections that traverse time, in many of these poems, including “Sunday Drives.” And I don’t think memory is only subjective, either; as the photographer Sally Mann says, “The earth remembers.”

SG: I love the juxtapositions in “Poland-China Pigs.” The exoticism of that poem’s headless chicken and the wind flapping at the roof of an empty house. Beauty and fear collide here, don’t they?

CS: Beauty and fear, terror and delight, right? It goes back again to your last question. Some of the poems in Then & Again, including “Poland China Pigs,” are about collating memory—an effort to present memory’s many, often confusing layers. There are so many “truths” you just can’t unknot as a child, and later you realize how much remains unspoken that nevertheless dominated the emotional landscape. Sure, memory is consolation—sometimes— a way to stop time, and, in my case, gestures to a quickly changing landscape of looted, abandoned farmhouses and some pretty vivid images stuck in my head from growing up in a very small (under 1,000 people) farm town in the Midwest. But it’s also a way to track one’s never-finally-knowable self. I agree that memory is inexact, suspect, totally dubious, but then again so is the whole notion of a stable “I” who writes a poem. Maybe as we get older we read our lives backwards, so we can meet our shape-shifting selves somewhere in the middle.

SG: Do you remember the first poem you ever wrote? How has your writing changed?

CS: I wrote my first poem when I was in third grade. I remember the title, “Glass Trees,” and that my father, bless him, let me pound it out on his manual typewriter, a pleasure right up there with kneading bread dough. Later on, in high school and then in college, I wrote poems in imitation of some early academic favorites—Wordsworth and Keats, Dickinson, Yeats. And then I started getting into Roethke and Stafford and Wright (later, both Wrights), and then Louise Bogan, Moore, Bishop and Rich. Poetry was becoming much more to me than an academic exercise. Adrienne Rich sent me a postcard in response to some poems I’d sent her that kept me going for a long time. When I went to the Iowa Workshop, I was in my twenties, and my first book (The Transparency of Skin, published by New Rivers Press) came out shortly thereafter. Then there came a time, a long time, when I stopped writing. I hung on to poems, or maybe they hung on to me, but—it’s hard to explain—I felt that my relationship to language and poetry had changed. I don’t mean to over-dramatize it, but it felt like I was waiting for something, was supposed to wait for something to click. We moved, we moved again, had children, I had a tango with cancer. . . .As I say in another poem (that isn’t in the book):

Work, money, children, cancer, aging

parents, dying parents, work, money, children.

When I said these things I wasn’t lying.

People call it quits every day

because of common uncommon pain.

It’s not a new story! When, after long silence, I did come back to writing, to poetry, I was fearful, overly cautious maybe. Working with the other poets of Slate Roof Press was more helpful than I can say. Eventually I was surer of what I wanted and didn’t want out of poetry. A friend of mine wrote, “The dependence on art as a reason for living becomes less persuasive.” I’ll say.

SG: What kind of poetry are you writing now? How is it similar to or different from the poems in Then & Again?

CS: I’m still intrigued by memory, what abides and why, but it’s not the centerpiece of my recent work. I’ve been writing more narrative poems, and I’ve got a couple of new poems out (one in The Yale Review called “It’s Complicated” https://yalereview.yale.edu/its-complicated) and one just out in The New Ohio Review called “The Dog in the Library”) where I use longer lines. I don’t ever want to give up rhythm and rhyme and other elements of formal verse, but I’m exploring voice and ideas more centrally in newer, looser poems. I’ve also written some angry, mostly sad, I guess, quasi-political poems. Given the state of our country in 2019, all the daily abrasions, you see just how much we really need the imaginative possibilities and tenderness of poetry.

0 notes

Text

Slate Roof poet Anna M. Warrock at the Somerville Armory + Open Mic!

Greater Boston Poets! Come hear Slate Roof poet Anna M. Warrock read with Bridget Galway and Zvi A. Sesling, and bring your poems! First and Last Word Poetry Series at the Somerville Armory. This coming Tuesday, 7 pm, followed by an open mic.

The Armory Cafe 91 Highland Avenue Somerville MA

Anna M. Warrock’s From the Other Room won the Slate Roof Press Chapbook Award. Besides appearing in The Sun, The Madison Review, Poiesis, and other journals, her work was anthologized in Kiss Me Goodnight, writing by women who were girls when their mothers died, a Minnesota Book Award Finalist. Her poems have been choreographed, set to music, and inscribed in a Boston area subway station. www.AnnaMWarrock.com

0 notes

Text

Po-Jazz and Kids! Susan Glass in Conversation with Audrey Gidman

Susan Glass is our monthly blogger with interviews of fellow poets, literary journeys, and all thing poetical.

Audrey Gidman's work can be found in Smeuse, Slippery Elm, Confrontation, Sandy River Review, and elsewhere. She was the 2016 recipient of the Slippery Elm Poetry Prize, and the 2018 Slate Roof Press Elyse Wolf Prize in poetry. She has been featured in The Portland Press Herald weekly column "Deep Water: Maine Poets," curated by Gibson Fay-LeBlanc, Portland Maine Poet Laureate. Audrey is a Reiki practitioner and bodyworker. She facilitates workshops in what she calls Love Letter Activism. Watch for a future blog post in which she describes these workshops.

SG: I'm interested in how poets cross-pollinate with other art forms and artists as a means for nourishing their craft. You recently participated in such cross-pollination with high school students at a jazz camp. How did that happen?

AG: For two weeks every summer, the Maine Jazz Camp for high school students is held at the University of Maine at Farmington. When I was studying for my BFA, I was a part of the Longfellow Young Writers’ Workshop, facilitated through the university, and we'd overlap with a week of the jazz camp every year. I was a TA in the poetry workshops and developed a relationship with some of the jazz camp faculty because I envisioned a collaboration with the jazz students and the writing students — po-jazz!

The collaboration didn't happen in my time at Longfellow, but I've maintained my connections with the jazz camp. Every year I attend the nightly shows given by the faculty, all internationally renowned jazz artists. One faculty member often saw me at the concerts. He knew I was a writer, and after asking about me at local book stores, invited me to come the next day to speak with his students. He had already talked to the students about the relationship between music, jazz, and poetry, and wanted me to read my work as a continuation of that conversation.

SG: It's interesting how opportunities happen, isn't it? How did you go about preparing with so short a lead time?

AG: I always have this thing where I never plan what I'll read or present beforehand; I like to understand what the room feels like first. I got in there and the kids were high energy. After all, they’d been in jazz camp together all week, jamming together, composing together. So I told them that although usually there's poetry etiquette — much like concert etiquette, where the poet reads and all questions are saved until afterward — I said that I would prefer an open dialogue.

And that's what we had. At one point when I read two poems back to back, I got about 16 questions. They wanted to know about process. They wanted information about the topics I was writing about. They asked about narrative, and we got into this dialogue about how poetry isn't straightforward, how what we're trying to achieve in poetry is often the invisible thing in the center, and all we can do is orbit the thing, try to get the physical sensation of it into the bodies of the people who are reading and listening.

SG: I like your idea of “orbiting the thing.” That’s the challenge, isn’t it? — capturing the smell of a fabric store, the curving ache in your shoulders after a day of gardening, the tight throat you get when you’re saying goodbye to someone with no idea of whether it is the last goodbye. How do we get all of that into language so that other people feel it, and are instantly alive with it?

AG: Right. Language is how we create that feeling in their bodies — that's what craft is. We talked a lot about craft. We talked about the importance of learning the rules so that you know how and when to break them. We talked about form — form in poetry and form in musical composition. We talked about how form is made by craft. We talked about Whitman and Dickinson, how Whitman was self-published because the reading public in his time wasn't ready for his work — and why that was. We discussed what Emily Dickinson was actually doing with those em dashes and capitalization, and what that meant at the time. That moved us into a conversation about ee cummings, and how punctuation and white space and changing the rules changes the way we are physically involved with the poem — that pushing words together like he did, eliminating the space between words and punctuation, and stretching out those pauses, causes the reader to tumble through the poem in a totally different way than standard linear movement permits. Cummings gave us that choice.

SG: Yes. It's the same choice that Hubert Laws or John Coltrane make when they lead our ears through a rollicking improvisatory solo. They open an expanse in what we thought the music was, and we tumble. The kids must have understood exactly what you meant. Can you talk a bit about the students, how many boys, how many girls, how they interacted with you one on one, how they talked.... that kind of thing?

AG: Out of roughly 50 students, only 5 or 6 were girls. So I had this circle of teenage boys around me after the reading. I’d shared some of my poems about spirituality, and they were asking me what I think about God, what I think the difference is between religion and spirituality. I said that part of my spirituality was my poetry, that I had to write poetry, that poetry had chosen me, not the other way around. I told them they were at the powerful and tender age where they had to come to terms with whether they were choosing their art form, or their art form was choosing them. A bass player spoke up then and said "Wow! All I ever want to do is play the bass. Now I know why. It’s because the bass chose me."

SG:That’s wonderful. It reminds me of something Martha Graham said about creativity as our vocation, our obligation to it, and the peril of ignoring it. She said, "There is a vitality, a life-force, an energy, a quickening that is translated through you into action. And because there is only one of you in all time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium, and be lost. The world will not have it. It is not your business to determine how good it is, nor how valuable, nor how it compares with other expressions. It is your business to keep it yours clearly and directly, to keep the channel open."

0 notes

Text

Love Letter Workshop with SRP poet Audrey Gidman: love is a sustainable practice

JULY 26, 6-8 PM: During this workshop we’ll write some break-your-heart-open love letters to ourselves because, let’s face it, when was the last time you wrote yourself a love letter? (Have you ever?) And when our love lettering muscles have been warmed up, we’ll write love letters to our mothers, or our best friends, or the mailman, or the person who makes our bagel at Java Joe’s every morning, or a total stranger.

A love letter can consist of anything—it can be a statement of true love, but it can also be a list of the qualities you love best in a person, or an appreciation card, or a list if thank you’s. It can be an at-long-last letter. It can be a you’re-the-rock-in-my-life letter for someone who’s going through a tough time and feeling small. Love letters lift us toward the light! They help us fly! Not only is it a radical healing experience to receive a love letter, but it’s a radical healing experience to write one. So let’s write a few.

Peace begins in your community. Your community begins with you.

Stationary, cards, pens and radical self love pep talks will be provided. Bring an open heart and the stamina for a little world-changing, one love letter at a time. Where: Vera’s Iron and Vine, 155 Front St. Farmington, Maine When: Friday, July 26, 6-8 Why: Love is a practice! So let’s practice! Cost: $15 How: To register, stop by the shop, comment in this event, or PM us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/slateroofpress/ Store hours: W/Th/F/S 10-5

0 notes