Video

tumblr

Qamata Festival

Iphupho L’ka Biko x Sive Mqikela

For God So Loved Us - Selaelo Selota

Video: Nkazimulo Moyeni

71 notes

·

View notes

Quote

[For the artist] chaos is not a condition to be faced in qualified agony hourly or daily or even yearly. Rather, it is felt as an absence far back and a proportionately urgent need to create some new order for himself and from scratch; that is, it is more likely to inspire work than to frustrate it.

A.Alvarez

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

WHAT IS DEAD MAY NEVER DIE - Sive Mqikela

On 26 October 2019, the fire spitting, scamtho-lingoed-poet Makhafula Vilakazi together with his cohort of vagabonds who go by the name of Kokorumba (a euphemism for Cockroaches) led by Koketso Poho’s velvet wailing and backed by Nhlanhla Ngqaqu’s zumba-ba-ba-zumba gwij’ basslines and Luyolo Lenga’s overtoned Umrhube and tickling Udu rhythms, dragged a stubborn bull by its horns into the kraal-cum-auditorium of Soweto Theatre. As usual for a ceremony of this manner, a call was made to the people to come bear witness to what was promised to be a brawl with the beastly figure of Mandela depicted in Slovo Maphanga’s artwork. Makhafula is no flip-flopper of a poet; and I imagine no other depiction of the vivid images of his lyricism than what Maphanga has presented as the artwork and poster for this project. In Maphanga’s artwork we see the ‘enchanting figure of peace’ transformed into an unbearable sighting. This beastly figure is donned in Madiba’s October 1962 court appearance swaggering Thembu royal outfit of isiyaca neck-beads nemibhaco. As if this is not enough beauty for the father of the nation, Maphanga insists on having another piece of neckwear to decorate Madiba, except that this piece of neckwear once reserved for those deemed to be traitors or witches is not so majestic for the Thembu royal. In the surround of this beastly face is a sketch of the map of South Africa, making Mandela/South Africa synonymous. The background is the colour of fire - gazole and matchsticks are on standby:

“bamfak’itoss neparaz uKawu, bam’gasa nges’gubhu sika bab’ akasebenzi separafin. Bashay’igwijo l’ka Samora Machel. Zalilizel’intsyza zakhona, bashaya amafleyt ooMjoint. Bamfak’ esekileni bamlayta...Kwashukuma iAfrika ngobudala bayo” (Makhafula Vilakazi)

“Wenzeni? Bengeke bamshise engenzanga lutho?”

The best person to answer this question would be Makhafula himself; but we must ask it in this way: what would make him go for what has become an easy target of scorn in the form of Nelson Mandela, in this stay-woke-type generation of ours?

Again we might have to look at Maphanga’s artwork for one last time, bearing in mind that Mandela and South Africa are represented to mean the same thing. In the absence of a working title let’s call it Amandel’Afrika, referring to both the artwork and the synonymous relationship between Mandela and South Africa as depicted by Maphanga. In Maphanga’s Amandel’Afrika, an earnest smile with missing molar teeth, clenching on a smoking pipe is imposed on Mandela’s face. Second only to Louis Armstrong in deceitfulness, this pipe smoking smile demands its own face, but only manages to sneak in just that - a smile. The owner of this smile - the sound of whose voice Makhafula Vilakazi and his cohort desires so much to hear as evidenced in their opening cry - “Sobukwe ulele kanjani? Siyakukhumbula. Sobonana kwelizayo” - remains only a memory to those who were there to see and hear the man. Unless the excavationists of Amandel’Afrika decide the time to air out this muted voice; Makhafula and Kokorumba can only hope to see him kwelizayo (in the next world), and that is if when they go to the next world, they won’t be met with Mandela acting as an intermediary for all that lived life in his South Africa. The tension between Madiba magic and this man with the smile is far more serious than we can imagine, and it is not by coincidence that the Madiba dance ended its tenure on earth on the day of this man’s birthday (05 December). Think for a second that other outworldly battles are possibly happening.

For the boxer that we see in pictures, Mandela is definitely poking thorns (uRhol’ihlahla) and throwing jabs on Sobukwe’s resting spirit. We are in Africa anyway, these things happen.

There is another figure demanding space in Maphanga’s Amandel’Afrika; his gaze, the opposite of the mona lisa effect, stares obstinately with one eye. His eye is not shaded with the colour of fire as is the rest of Maphanga’s figure. He is probably putting on a fight as he himself says:

“My attitude is, I’m not going to allow them to carry out their program faithfully. If they want to beat me five times, they can only do so on condition that I allow them to beat me five times. If I react sharply, equally and oppositely, to the first clap, they are not going to be able to systematically count the next four claps, you see. It’s a fight.” (Biko)

His offspring in the form of groups like the iPhupho L’ka Biko (Biko’s Dream) jazz band are also making attempts to put on a fight and to testify to the potency of his weapons. However, judging by the current situation in Amandel’Afrika, this man might, as Mbe Mbhele suggests in his poem, Biko is Dead, be in need of some introduction to black consciousness. One will have to visit Mbhele’s poem to fully appreciate this problem.

In this world and the other one, it seems that the Madiba magic glitters as an emblem of many possibilities for what looks like an eternity. Think of how Mandela Bridge spits people in and out of the two worlds it separates, day and night.

Mandela is unwilling to die alone in the necklacing carried out by Maphanga and insisted by Makhafula and Kokorumba. With him will be his beastly comrades in eye and smile.

“Witchcraft you’ll never win me. He’s here! He’s here! Ula. Ula” (Makhafula Vilakazi)

As an African people, what do we do to an (un)holy spirit of our departed kinsmen that is a menace to the living and to the departed?

Perhaps the motive for Makhafula to title this gathering “Mandela is Dead”, is to precisely answer this question. He seems to know what he’s supposed to do, but complains about the difficulty of the task and the labour it requires:

“Ngizihambe zonke izinyanga zaseSpruit, ngigquma, ngichatha, ngiphalaziswa ngobisi lembuzi, ngiqiniselwa wena nalomgorho wakho” (Makhafula Vilakazi).

As if the stay-woke children of the city of gold needed any more reasons to justify their contempt for sleep, the 120+ seater kraal-cum-auditorium was filled to capacity with everyone wanting to catch sight of this (un)holy ghost. If they knew what they were getting themselves into, that one you will have to ask them. The singing along whenever the Kokorombas invoked a familiar selection in the struggle’s discography is evidence that they were however, consenting participants.

Wazi Kunene, who did the difficult task of master of ceremony, jokingly bestowed Makhafula Vilakazi with Mzwakhe Mbuli’s long held title of ‘the People’s Poet’ and the crowd approved. Old age will not make the fight fair for Mzwakhe Mbuli to defend his title; I suggest he retires it, but only if Makhafula is interested in having it.

To sweep the fields for this (cleansing) ceremony was Nomashenge Dlamini with her electrified and sermon-like rendition of Ingoapele Modingoane’s epic poem Africa My Beginning, Africa My Ending. Under Silla Dulaze’s diligent cut with the lighting, Makhafula and Kokorumba brought the beast down, leaving the room in euphoria and nostalgia; you’d swear we had never known sorrow. But the beast rested only for a moment, only for us to return to the spell of our Amandel’Afrika an hour later.

Khafula Makhafula, thina siloyiwe.

Culture Review link

https://www.culture-review.co.za/what-is-dead-may-never-die-makhafula-vilakazis-mandela-is-dead

20 notes

·

View notes

Link

“Eddie and I were in the studio, tripping like crazy but also trying to focus our emotions... I told him to play like his mother had died, to picture that day, what he would feel, how he would make sense of his life, how he would take a measure of everything that was inside him and let it out thought his guitar... I knew immediately that he understood what I meant. I could see the guitar notes stretching out like a silver web. When he played the solo back, I knew that it was good beyond good, not only a virtuoso display of musicianship but also an almost unprecedented moment of emotion in pop music." - George Clinton

24 notes

·

View notes

Link

Daddy Trane’s approach to jazz.

What it means to be a saint

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Once there was Kwaito and it made us dance: the past and futures of Kwaito - Sive Mqikela

From a distance, I have been looking at the conversations around the apparent death and/or survival of Kwaito music. The originators of Kwaito in the form of the Trompies, Mdu, B.O.P and others are unwilling to admit to this death. They insist (justifiably so) that the cultural phenomenon that was once (if not still) the ‘soul’ of post-apartheid popular culture can never die, it took new forms as any culture should. They also seem to suggest that Kwaito will subsist as long as there are still townships in South Africa. In other words, as long as the conditions that created it subsist, the music will always be.

Many are of the view that the (Sowetan) sensibilities we once knew from the sound are no more. The slow-tempo bass and drum accompaniment to the hardcore-joyful-lamenting lyrics of ‘kasi’ (township) living are catching dust in zones of nostalgic frenzy; they say. In public perception (parties and stuff) the music is considered an ‘old school’ moment; a music for reminiscing. No one cares to know what Kwaito song is ‘hot’ at the moment, people seem to be only interested in the classics – Mandoza, Zola, Mdu, Brown Dash, Spikiri etc, except if they hear from the new sounds something similar to the old sound – a verse, a sample, a chorus.

Boundaries have been widened (arguably) and a new breed of ‘Pantsulas’ (Kwaito men and women) has emerged, self-appointed to take up the task to preserve and continue the music. “Kwaito is not dead, it evolved; it is now ‘New Age Kwaito’ bruh”, they say.

Fair enough.

In what we could call the ‘golden age’ of Kwaito, this new breed of Pantsulas (new Pantsulas) occupied the category of ‘aboMrapper’ (rappers), a detested group of American wannabes – ‘amakoporosh’. For the ‘golden age Pantsula’, the ‘aboMrapper’ could not fit-in to the quintessential ‘rough and ready’ Panstula image that was demanded from a Kwaito figure. They spoke too much English and gibberish – a sign of weakness and affluence; their ‘swag and slang’ was alien to what was understood by the township at the time (see Mzekezeke, Amakoporosh). The aboMrapper’s image was in contradiction to the Kwaito sensibility that privileged the mastery of marginality of ‘Olova’ and ‘Oguluva’ - the quintessential hustlers. As the influence of hip-hop grew globally, attitudes towards it changed and aboMrapper gained access to the Kwaito subculture by demonstrating that they too are ‘hardcore’ hustlers fit for the Pantsula label.

The year is 2018…

The ‘new Pantsula’ (formerly known as aboMrapper) is trying to convince us that the preservation and continuity of Kwaito will happen by way of ‘sampling’ Kwaito ‘classics’. To the ‘new Pantsula’ sampling seems to be an appropriate model for composing and continuing Kwaito music. I am, however sceptical of the sincerity of this process and I wish to explain why. In popular music cultures like Hip-hop and Kwaito, sampling, as Professor Bheki Peterson asserts, is used as a democratic music-making means to ‘displace previous and sometimes conservative music production methods predicated on the centrality of live musicians’; and thus through this process music-making as a vocation is made available to those who do not necessarily have the opportunities due to lack of resources. As observed by Peterson, sampling could also be viewed as a method to “renew past musical milestones, updating them to make them sound fresh in the present”. In this process, Mariam Sulakian argues that producers and artists “cultivate a realm of musical preservation while embedding their own creativity into the original song’s creative legacy”. Although unannounced, the creative genius is always measured by the degrees in which the new track artistically modifies or supplements the original. Precedence also tells us that the producer samples from a different genre and era (sometimes) which serves two functions: firstly to bring audiences of that other genre to this new music (Kwaito); and secondly, to present the listener of the new music (Kwaito) to the musical worlds traveled by the particular artists/producer to create the new sound. Msawawa’s Bowungakanani and TKZee’s Shibobo, are a case in point.

My suspicion is that this sampling relationship between ‘the new Pantsula’ and ‘golden age Kwaito’ operates at a very exploitative manner. If we argue that Kwaito is not dead, it took new forms, then we must be willing to regard the ‘golden age Kwaito’ and the new Pantsula Kwaito/New Age Kwaito as contemporaries, operating in one temporality – this spacious present of post-apartheid South Africa. If we agree with this proposition, then we should remember that in Kwaito and hip-hop cultures the ‘sampling’ and ‘chopping’ of your contemporary’s music is considered as ‘biting’ or ‘ukugawula’ (plagiarism) (see Magawula by B.O.P). Therefore, the ‘new Pantsula’ cannot justify their perpetuating the Kwaito sound by the current musical practices they undertake. In their songs and music videos, the ‘new Pantsula’ assembles Kwaito tropes and imagery rhetorically - from lyrics and beat to costume and dance without any display of commitment to the furtherance and variation of the music. This happens in a manner that is intended to manipulate public sentiment by pre-empting the responses that will arise from those who listen to the ’beat’ and remember the cultural value the ‘sound’ of Kwaito once and still occupies. The ‘new Pantsula’ knows very well that no other music has captured the imagination of post-apartheid South Africa in the manner that Kwaito did, and that is why he/she will sample the Kwaito song in such a way that you won’t mistake it for anything else (taking the song as it is). I am not suggesting that the ‘new Pantsula’ is not a participant to the cultures that make up the sound, I am saying that the manner in which the ‘new Pantsula engages Kwaito exploits the cultures that make up the sound without any sign of commitment. For example in his 2017 Stay Shining music video and song, Ricky Rick makes a visual reference to TKZee’s We love this place and Dlala Mapantsula, to such an extent that he couldn’t conceal the borrowed lines and flow from Kabelo Mabalanes’s Pantsula for life. He is not alone; there are many others from Casper Nyovest to Major League and many more. Although these could be deliberate moves; but do we call Ricky Rick and company creative for reiterating to us, a moment which has not escaped our memory?

I doubt!

In conclusion, I am of the view that Kwaito music cannot be sustained in the manner that it is happening (sampling the self); possibilities should be extended and explored by the new Pantsula in the same manner that Kwaito emerged in the early 90s. If Kwaito is still alive (at least a healthy life), we should be able to detect it from the current (Panstula) musical practices without the help of these suspicious sampling methods alluded to above. To convince us that they are serious about this continuity and survival of Kwaito, the ‘new Pantsula’ should be able to do a song without any use of a line or verse or a sample from a ‘golden age kwaito’ or house song.

Not all hope is lost though; there are some of the ‘new Pantsula’s’, although not many, who display some commitment to the development of this sound in ways that are not so exploitative. These new Pantsulas have inflected their interventions with more hip-hop influenced approaches – and I think the reason why their sound always works with the people is because it goes back to the source (Kwaito/kasi) – think of Kwesta’s success for example.

M&G Link

https://mg.co.za/article/2018-12-07-00-kwaito-golden-or-new-age?fbclid=IwAR0OiecTBDFGF0KOLHIb27uHfHCg7v3228UA4-zzhOH9Pcx26mWw9s7kk7M#.XAmg3-qqHBQ.facebook

60 notes

·

View notes

Photo

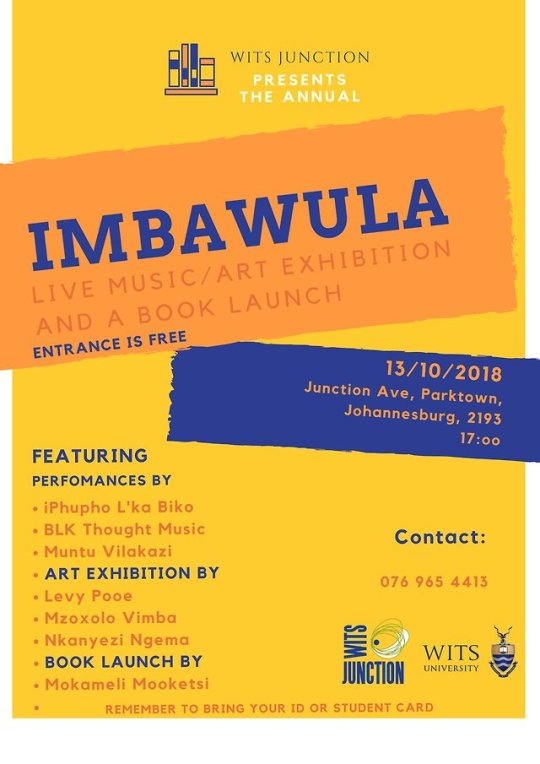

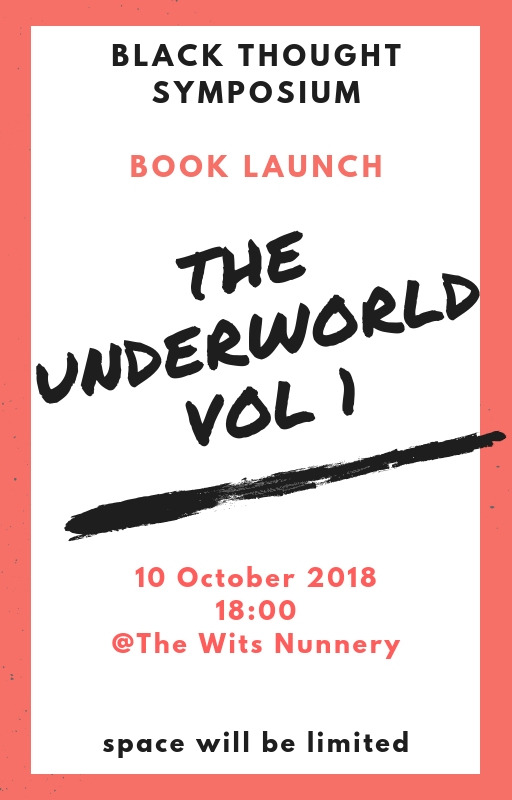

Black Thought Symposium Book Launch: The Underworld Vol 1

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Set in Tobago, The Resort is a short film that is comprised of three vignettes that gives an intriguing glimpse into the lives of workers in Caribbean tourism. The film explores the correlation between sexual politics and work by contrasting the mundane realities of women to the shocking and unseen behavior of men in the tourism industry. Directed by Shadae Lamar Smith. Instagram: @blackbarcelona @warriorandmuse Site: http://shadaelamarsmith.com Twitter: @shadaelamarsmit

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monkey Buziness

Dance and never stop.

One-two-steps on

a two-tone-leather.

Bare chests in whatever weather.

‘Cothoza mfana’

and sneak out the room

for they know the rumour.

Rhythm and Smile

Melody and Hum

Till thy applause come.

When they ask about home

tell them:

“In the jungle

the mighty jungle

Its monkey buziness as usual”

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sangomas and Struggle Heroes: Art after the Fees Must Fall moment - Sive Mqikela

“Day to day reality is therefore itself any illusion created by the mass of our needs, our ideas, our wants. Transform the needs, the ideas, the wants, and at once, as though with a magic wand, you transform the available reality. To write as though only one kind of reality subsists in the world is to act out a mentally retarded mime, for a mentally deficient audience. If I am an illusion, then that is a delusion that is very real indeed.” – Dambudzo Marechera, Black Sunlight

In July 2018, a group of art students under the name ‘Wits Stash’ set out to the Grahamstown (now Makhanda) National Arts Festival (the festival) to present the best of art that the University of the Witwatersrand School of Arts (WSOA) has to offer. The entourage comprised of four plays - Amabali Amandulo, Indodakazi Yakho, Vuselela and The Last Respect, and one musical act, the Afro-jazz ensemble - iPhupho L’ka Biko. This was the first time that WSOA sent students to the festival to showcase their works under its banner. I was asked by the collective to write a review of the works presented, for the purposes of the group being able to read itself and its artistic effectiveness, so as to make the trips to the festival a tradition that will continue for years to come. This review is mainly my reading of the plays, not only because they constituted the majority of works presented by the collective, but also because the music has been engaged lengthily elsewhere; although my observations here are not in exclusion of the music. The plays were in different styles and theatre genres, but in the main addressed themes of protest, historicism, existentialism and feminism (Indodakazi yakho). Although this is a review of the aforementioned plays, it is also a de facto reading of the whole contemporary South African theatre scene as witnessed in the festival.

In all the freshness that a particular work of art may possess, artistic works are the always-already-present fragments of our realities, organised and given coherence as narrative anew. In this terrain, the stage does not become a mere mimicry of life, but life and history are laid bare in creative and imaginative form. What should a representation of a life in chaos, confusion, betrayal and spiritual bankruptcy, such as is life in South Africa look like? The formulation of the ‘Wits Stash’ is perhaps a clue to this rhetorical question. After the festival it became apparent to me that contemporary theatre is very much interested in the classic black theatrical themes of protest, spirituality and tragicomedy. This is no coincidence, owing to our very own little affair with history – the Fees Must Fall (FMF) moment.

This trip to the festival was an opportunity to witness the sediments of a post-FMF arts and culture scene. One was left wondering and imagining what the post-1976 artistic scene looked like; it probably looked something like this ‘Wits Stash’ moment in Makhanda.

Pause….

The contemporary arts and cultural scene owes itself to the enthusiasm and indecision, doubt and confusion, chaos and order, of post-1994 South Africa. From everyone, there is a burning need to respond, to kick and scream, to take to the streets, to battle with history fair and square; all the necessary tools are available (arguably), we just do not know how to use them. After chaos there is confusion; everybody has something to say but there is just no way of corroborating its validities. With so much information available to us, how do we use it in the most creative and sustainable manner? Where do we go from here?

This I imagine to be the dilemma in the aftermath of 1976, save for the fact that post-1976 was probably approached with more ideological clarity, perhaps because there was a more visible obstacle to black liberation – apartheid.

We are in no position to tell right now – only time will.

If not to elope to Europe or swell the ranks of the liberation front; to join the picket line or wish for a miracle; where did the 1976 generation go in the aftermath of crisis? If they did art, what kind of art did they do?

While there are such great works in the South African black theatre repository to work from, contemporary theatre seems unable to respond to the problems of our time in the same compelling and poetic manner that great works of ‘protest theatre’ like Woza Albert (1981) and Sizwe Banzi is Dead (1972) did for their ‘time’. While we can detect the influence of these classics and others on the plays presented by the ‘Wits Stash’, their imaginative and artistic impact is however overlooked and misunderstood. For example in Vuselela the powerful trope of the invisible and omnipresent character as seen in both Sizwe Banzi is Dead and Woza Albert, is attempted to allude to the omnipresence of black suffering in the face of domination; but as the play unfolds this character is revealed haphazardly on recurring dance scenes; and as a result the work of this metaphor is rendered banal, all for the sake of being multidisciplinary.

The problem with contemporary theatre is its obsession with ‘the spectacle’, in the same sense that Njabulo Ndebele observed with black South African literature during apartheid. In what felt like the newspaper headlines from The Dailysun and Sowetan, we see on signposts and street lamps around Johannesburg roads, the plays go for the overly dramatic and ‘spectacular’ element of social life in South Africa: police and state brutality; politicians and lies ; violence of all kinds, ancestors haunting the living etc.

These plays are not only concerned with a generalised display of ‘the spectacular’ but they are also very intentional with asserting political positions – ‘the spectacle of politicking’. In The Last Respect, as the protagonist ‘Goodman Moswaswi’, an apparently schizophrenic ‘direct victim of apartheid violence’, goes on his episodes of remembering the gruesome suffering endured at the hands of apartheid, all experience and memory communicated by him are channelled through a stream of incoherence and absurdity, but only one thing is coherent, his instinct to politick. We see ‘Goodman’ moving from ‘economic freedom’ and ‘expropriation’ talk to statements about ‘sell-outs’ and ‘askari’.

One could argue that politicking is nothing reprehensible in the creative process; but what happens when art is sacrificed for pure political undertones. What do we make of the arbitrary calling out of struggle heroes’ names – “viva Nyerere, viva Lumumba, viva Biko…” whenever we see fit, even when the context demands otherwise? Do we use the authority and stature of these figures so that no one disagrees with us? Without being prescriptive, I am of the view that when one has interacted with certain texts and ideas, we can always discern his/her influences without the help of ‘name-dropping’. We saw and heard enough moving speeches and amandla awethu during the FMF, and the ‘stage’ requires a more artistically persuasive and inspiring political commentary, if one seeks to do protest theatre.

Is it not possible to have creative imagination take the centre ‘stage’, even when representing real situations about social and political life in South Africa?

How do we create art that not only confirms what we know, but also offers challenges and critical engagement with what is being presented?

This being said, I am cognisant of the fact that the political narrative has shifted into our social culture as a nation. Politics has not only permeated our personal and public lives, but also our cultural production and imaginative labours. It is probably inescapable for the contemporary cultural worker; hence it is not surprising to find the political narrative central in many works of theatre and other literatures. While we cannot blame writers and cultural workers for centring the political thematic or using political vocabulary in their work, we can however be more careful with the style and aesthetics of the political narrative we choose to employ. We need to be more critical and reflexive about the forms that we choose to use in order to convey the political.

In ‘the spectacle’ of postcolonial discourses sits the grandfather of all rhetoric – the notion of the African past. Yes – that mystical world of speculation; of apparent harmony and inherent rhythm; a world of sangoma’s and ancestors. The problem with this discourse, even well-meaning ones, is that it fails to acknowledge that all discourse on the (post)colony is a product of domination, and the ideas we have of an African past and Africanity are actually inventions of colonial discourse, which serve as a ‘subtle operation of temporal distancing’. Amabali Amandulo (stories from the past), in what appears to be an innocent story devised in ‘township/physical theatre’ style, is engaged with notions of the African past. In terms of the synopsis the play “speaks back to the politics of family, power dynamics and gender inequalities”, based on family life of the past. The play employs common tropes of the myth of ‘Africanity’: ancestors with gnarled bodies gyrating and speaking to the living in the most literal and arbitrary manner; freaks of nature with hoarse voices; friends capriciously turn into enemies; and uncontrollable sexual desires – smells like colonial imagery to me. Through cursory scene changes, the play denies us a sense of spatiotemporal coherence and causality (Africa with no time); and instead of stories from the past the play feels more like an assemblage of stereotypes about rural life in South Africa. The play gets one thing right though: this African past is a very strange past if we are to take the myth serious.

Overall, all the plays were well directed and outstandingly performed. Elegant amalgamations of different artistic forms were employed in all the plays in the service of accompanying the acting. No one can deny the artistic wholesomeness of each play. The actors are undoubtedly some of the best actors in the country. My concern is just with the conceptual development involved in the making of the stories. After all, whatever the artistic validity a certain work of art may possess, in trying to make sense of it there are, in Hayden Whites words “always legitimate grounds for differences of opinion as to what they are and the kinds of knowledge we can have of them”. These are but my observations. If we are to return to the epigraph from Dambudzo Marechera and listen to his caution, we ought not to create art as though only one kind of reality exists. In conclusion, I am of the view that collectively as art students and cultural workers we should not only revisit the classical texts that continue to shape our work and imagination, but we should also familiarise ourselves with theoretical work from other disciplines such as literature and social sciences in order to widen our worlds and enrich our imaginative force.

Yours Truly

BLK Thought

(work in progress)

16 notes

·

View notes