In which a fluctuating group of disappointed public sector workers and monks - calling ourselves the Roadswim Collective – attempts to prise ideograms of ideal intent from the horizon of the mundane. We bring you leaves on the breeze, pylons on the hill, strange glimpses on the drive home from work. When you have lost your keys and very little makes sense to you, join us then in The Effluent Lagoon, and we will cleanse you for reuse. Not recommended for soothsayers.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Three Times He Lied To Me - Lie #1 (version 2)

I was twenty four when I met Will. I fell for him. We were together for a couple of years, the first one pretty good, the second pretty bad, and then we split up. I'm forty three now and this morning something funny happened that made me think about Will for the first time in years.

It was 1997 and I was back in Aberdare, living with my mother, after three years in halls of residence. Here's a list of the places you'd be most likely to see me during the year I was twenty four:

on a train

in a library

at a railway station

in a corridor

on a bus

at a bus stop

in my bedroom.

I had literally no social life, unless you count going to the shop for tobacco. My best friend was my I, Claudius box set. On Friday nights when my mother was out with the girls from darts, I'd lie in the bath for a couple of hours, drinking Prosecco and reading Mary Beard. Sometimes I'd do that on Saturday nights too. Occasionally, very occasionally, someone I'd been at uni with might phone to see if I wanted to come for a night out in Cardiff. I tended to say yes and then not go. I'd get so stupidly stressed in making the arrangements that I'd be tired before I set out. I never knew which train to catch, or what to wear or say. Then a voice in my head would ask why I was even bothering, and I never had an answer. So I just put everything away, closed the wardrobe doors, and stayed at home. But then I'd have to make some idiotic and obviously untrue excuse, and over time the invitations dried up. The whole thing filled me with equal parts shame and relief. So then I'd tell myself that this was just the way I was, no point feeling guilty about it, run a nice hot bath and get the Prosecco from the fridge. And of course later on, in bed, I'd have to stop myself thinking about it all, imagining the sort of night they were having. I was a funny sort of girl, really, all awkward and unsure.

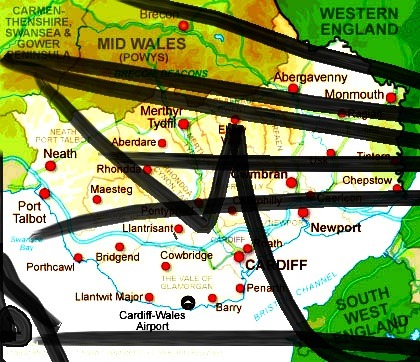

I did go other places sometimes. If the weather was nice you might see me in a castle. Or I might be at Caerleon, looking at the Roman stuff. And now and again you'd see me out of breath at the top of a hill somewhere looking at the remains of an Iron Age fort. I was always alone on these excursions and they were always slightly unsatisfying. Not because I was alone, that was fine, but because they were the same old tourist traps, the places I could get to on public transport. I hadn't learned to drive and couldn't afford a car anyway. I knew of dozens of places within a 25-mile radius of home that had interesting old things to poke round but I couldn't get to them by bus so they were out of bounds to me. Even Caerleon, which I did to death over about three summers, was four different buses from Aberdare. You'd spend half the day getting there and back. I remember how desperate I was to be a driver but I couldn't even afford lessons.

I'd just begun a Master's in history, a two-year course, and I was completely broke. Amazingly I'd got a First in my degree and my tutor recommended me for post-grad. It was all a bit overwhelming. I was the first in my family to go to uni, you see. Well, my father was accepted at some art college back in the day but he didn't go. Both sides of my family had always been miners and farmers, originally from Carmarthenshire. There were no mortar boards in our history until I came along, which seemed quite a big deal at the time. Also, I was never one of those kids who are expected to go on to higher education. I left school at sixteen with a handful of mediocre O Levels. Yes, O Levels, I'm ancient. I don't blame the school really, it was no worse than any other valleys comp. Plenty of bright kids went on to good things from there, my friend Chloe stayed at school to do her A Levels then went to Cambridge to study physics.

Most teachers had me down as one of the bright kids but I just wasn't in the right head space at the time. My father left home a week before my fifteenth birthday and everything went mad. It was about the messiest break up imaginable. If I gave you the details it would sound like something from Jeremy Kyle. There was fighting, there were threats, there was an arrest. There, that'll give you some idea. I couldn't handle school at that point, I couldn't handle anything. My mother wasn't in the best shape either, off work with anxiety and depression. The bank nearly repossessed the house and my brother got an eighteen month suspended sentence for threatening behaviour. So I sleepwalked through my exams, got the kind of results you'd predict, and that was it for me and school. I decided I should explore the world of work, make some money, maybe move out and get a place of my own.

I knew exactly where I wanted to live, right at the top of Heol-y-Mynydd. This was over the other side of Aberdare from us, a street of council houses climbing the lower slope of the western valley wall. As far as you can go in that direction without leaving the Cynon Valley. Cars traverse an alpine zig zag to the plateau, heading to and from the Rhondda. When it's night and you look out of your bedroom window, down in Robertstown by the river, the highest little orange lights you see before the black of the mountain, that's Heol-y-Mynydd. It's one of those steep streets where each layer of houses overlooks the rooftops of the layer below. I fancied living up there. I wanted one of the houses in the last layer, the ones that backed on to the hillside, where the road ended. I saw myself sitting at the window in a quiet kitchen, watching the mountain rise up in stages, first trees, then ferns, then stubbly grass and exposed rock to the top. When my parents were shouting and screaming horrible things at each other, I'd feel like they were injecting broken glass under my skin and I had to get out. So I'd go for long walks, usually with a bottle of something and a packet of Marlboro Lights, trying to go where there were no people. That was easy enough in Robertstown as most of the place had been knocked down years ago. Our house was in one of the few streets left. You could see where the others had been if you walked through the wild weeds and bushes that grew over their remains, and this I did. Sometimes I'd cross the bypass and go as far as the two hundred year old bridge. I looked down at the matted lines of moss under my boots and saw traces of the tramway and of the buried canal.

Skirting town through sidestreets I'd come out on Victoria Square where the statue of frock-coated Caradog outside the Black Lion would wave his left hand at me, the conductor's baton held high in his right. From there it was a long slog up the hill, sometimes to Dare Valley Country Park to sit in the café and watch the happy families being happy, or all the way up to Heol-y-Mynydd for the view. I stopped going there after a while. There were some girls living up there who didn't like me. Their parents didn't like my mother. It was all very tangled and twisted, some of them were belonging to my father, there was some grudge there I didn't entirely know about and I didn't want to either. I got spotted mooning around the cul de sac on a Sunday afternoon and it went round that I was roaming the streets pissed up. My mother got the blame then passed it back to me. So I cut Heol-y-Mynydd out. I could get the same view from the Country Park, so I started going there. You just had to get past all the happy people, the horse riders and the hikers and the families in the play area. I didn't dream of a house in Heol-y-Mynydd now. I dreamt of a house built into the mountain itself, halfway up the ridge, half-sunk into the rock, half-hidden in the ferns, built of wood and stone, plastic bottles and tyres. I'd run solar cells from a water wheel in the stream, grow my own food, reuse every scrap of waste. They'd never find me there, and no-one could ever lay a claim to my house, no mortgage lender, no bank, no landlord, no family, no council, because I would have built it with my own hands.

Meanwhile, back in the real world, I ritually burnt all my school stuff in the back garden, and set off to explore the world of work. First I got a job in a factory in Talbot Green, hated it and left after six months, then got a job at the tax office in Llanishen, hated it, quit after nine months, then worked in a nursing home for almost year, which I hated even more, then on the dole for six months, which nearly killed me, then Asda for a year and a half, which was okay but deadly dull. I never made any money, the pay was always crap, no matter how many hours overtime I did. And most of it went on getting to work and back, on keeping yourself fed and clean, just basic living. I couldn't afford a place of my own, I just skulked in my bedroom, listening to Nirvana and blowing smoke out the window. I was drinking a fair bit by then, getting stoned before work, throwing myself at stupid boys who didn't give a shit about me, wearing long sleeves to hide my cuts, all the usual teenage stuff.

I remember being in Aberdare Park one Saturday night, drinking and smoking weed with a couple of girls and a whole load of boys from Cwmbach. They were loud, those boys, and people were looking. Rhian Abbott spotted a squirrel in the tree above us and one of the Cwmbach boys took aim and threw a beer bottle at it. I felt sick. So I turned away from them and locked eyes with Chloe, my friend from school, the one who went up to Cambridge. I hadn't seen her for a long time, we weren't really friends anymore. She was walking her family's dog along the wide path from the lake. My face was frozen in its grimace. I felt cold in my stupid little vest top, my stupid short skirt, squatting there under a tree with my bulging thighs. Chloe was neat but casual in blue jeans, white top, nice blue fitted cardigan. She smiled at me as she passed, a very brief but very kind smile, understandably not wanting it to be seen by anyone else, certainly not the Cwmbach boys. I appreciated Chloe's warmth but I couldn't unfreeze my own face to smile back. My stomach was burning.

By the time I got to Asda, I was about as bitter and full of regret as it's possible for a person just turned twenty to be. So this is it, I thought, the world of work. Sheer bloody purgatory. I had this voice in my head all the time, it went something like this: if only you'd stayed in school, done some A Levels, if you could just have kept it together and managed that, you wouldn't be here now, on the bus to work at 7am, you'd either be in a much better job, doing something you actually like and be any good at, or maybe even at university studying history maybe or English, but you couldn't, could you, so this is your life now. And so on. If I didn't shut it down, and I couldn't always shut it down, it would keep going, pointing out every mistake I'd ever made, every underlying flaw in me, cutting deeper and deeper, if only you were braver, if only you were more interesting, if only you were thin and pretty. It filled every hour I spent at work and invaded all the hours I wasn't, ruining whole weekends, dragging all my longed-for patches of annual leave into the pit of despair. I hated the sight of myself, avoided mirrors and windows. Pure regret is the most horrible feeling, it burns. It's like drowning in your own stomach acid.

So I eased up on the self-medication – vodka mainly - and started going to night school. Weirdly, it was my father who put the idea in my head, on one of the very rare times he bothered to get in touch. My relationship with my mother was at rock bottom, we weren't even arguing by that stage, just silent, then my dad turns up out of the blue and tells me I'm a clever girl, and says why not give education another go. So off I went to Aberdare College and enrolled. Three A Levels, English, History, and Sociology. In my memories of night school it's always winter, I'm always shivering at the Cwmdare bus stop in the dark. My brain seems to have muted the other seasons, the light nights and the warm weather, and fixated on the image of me waiting for the bus home in various combinations of cold, wet, and windblown. I suppose it did get fairly exhausting, working all day and heading out to college at night, and it didn't help when the weather was terrible.

But I kept it together and it turned out I was really good at studying. I spent weekends in my room, reading and writing and making notes, instead of getting off my face in pubs and up back lanes and in boys' cars. I kept my brain so busy that the if only voice could hardly get a word in. Now I'd gained a bit of confidence my essays were getting better, more expansive, with bits of original thought in them, actual ideas I was coming up with. They were coming back with A pluses and comments in red, responses to the points I'd made and the examples I'd used, suggestions for further research, engagement with my arguments. Encouragement, basically. Of course, I could barely string a sentence together when talking to lecturers, but I'd be smiling all over my face as I tucked my essays away in my bag, ready to take them home, read the comments again, then file them neatly in their folders.

Lyndsey Walters, my English lecturer, was tall and slim with long silver hair and Virgina Woolf cheekbones. I liked her a lot, she seemed to get me straight away. One day in April she asked me what I was going to do when I passed my exams. I laughed and said, "If I pass them." She told me that all I had to do was carry on as I was and there was no question I'd pass them, and probably with very good grades. I told her she had more confidence in me than I did. Of course Lyndsey was right on that score, I got As in English and History and a B in Sociology. I told her I was hoping to get a better job than the ones I'd been doing until now, or maybe even try uni. She smiled and said, "If you chose university, Anna, I'm sure you'd never regret it." That was the exact moment I made my mind up. Well, between that moment and the half hour wait for the bus. Those two words next to each other, never and regret. That was what did it, I think. It was pretty obvious that this was my second chance, and probably my last. If only I could keep it together, pass these exams, get my A Levels, I could go to university. I could be a student. For the next three years I'd be studying for a degree. Lyndsey was sure I'd never regret it. And of course she was right on that score too.

So I went to uni and, as I say, it was quite a big deal at the time. Nerve-wracking. I more or less expected to crash and burn. Everyone else seemed so confident, so talky, and loud. So English, I was about to say. But that's not fair. I just hadn't met many people like that back then. A lot of them hardly bothered going to lectures and they were always incredibly insulting about the lecturers. Now me, for the first two years I just kept my head down and my mouth shut. I worked as hard as I possibly could, hoping to keep up. I read literally everything. When a lecturer praised my work, I'd carry that around with me for days like a little glow of fire to ward off the doubts.

The other freshers, of course, were always on the piss. Now me, I was trying my best to stay off the booze. I started drinking properly when I was fifteen, as my parents marriage was imploding. I was either horribly drunk or horribly hungover for most of the next five years. That was how I dealt with the crap jobs and the crap everything else. I still associated being drunk with being almost suicidally miserable. This went on until I started the A Levels, when I weaned myself off daily vodka and began saving it for the weekends. After a lot of effort, I got my drinking under control and I wasn't going to lose it now. But this lot, my fellow students, drank like kids when Mum's gone out and left the drinks cabinet open. That's how they seemed to me, like little kids. I'd imagined uni would be a place where you'd make amazing friendships with people of like minds. It was a bit disappointing to find I didn't seem to have a lot in common with anyone. I did make some friends eventually, a little gang of us, all a bit socially awkward, clinging to each other.

Not that I was some kind of nun. My main indulgences were:

thin little roll ups in liquorice papers smoked on the library steps, about one every half hour

a bottle of Stolly (this, as I say, was the 90s) in my bottom drawer for winding down at the end of a long essay

the occasional lump of cheap hash to see me through the holidays

a boy from Norfolk with nice dark eyes, though that was more trouble than it was worth.

By the final year I knew I was heading for at least a 2:1, possibly even a First. There didn't seem so many of the loud talky ones around by then. There were a lot of drop outs. On the one hand that made it hard, because the spotlight began to shine on me a bit more. I couldn't just hide at the back of the seminars anymore, I was invited to contribute. I was still awful at talking to people, my voice sounded terrible. On the other hand, those little glows of praise from my lecturers had grown into a proper fire, burning day and night. And I started to see them as human, my tutors, not as untouchable gods or whatever but as people who were obsessed by the past, by trying to dig it up and read it and see it as it was, just like me. It was hard to believe I'd made it to the end of the three years. And now they were encouraging me to take it further, to do an MA. I mean, it was way beyond what I'd expected. That last year was just wonderful, I loved it.

The day I graduated, my mother cried and my brother puked. We were all in the union bar, toasting each other. I can drink my brother under the table, and I did. Uncle Lloyd was there too, wearing a blue suit that I won't forget too soon, putting away the cheap beer and chatting a bit too much to my girlfriends. My father hadn't turned up. He'd promised he would, but that's my father. I used to be such a daddy's girl but even so, I can't believe I really expected him to be there. Maybe I didn't, I can't quite remember now.

So anyway, yes. That was nice, to be doing so well. And now I got to spend the next couple of years digging around in post-Roman Britain, a time I'd been mildly obsessed with since I heard the stories of Saint David and Saint Dyfrig in RE at school. I always saw it as this mysterious realm full of saints and kings and warlords and clashing cosmologies, all of it hidden in layers and layers of myth and dirt. It was like digging up a real life epic, it was kind of a dream come true for me.

On the other hand, after three years as a student I was completely broke. And here I was back at home, with my mother, just the two of us now, my brother having left home. I was commuting to Cardiff from Aberdare, an hour each way on the train, to do my studying. I was making a tiny bit of money working part-time in college libraries at different campuses all over the place, not just Cardiff, Merthyr, Treforest, all over. I had an encyclopaedic knowledge of the Valley Lines timetable. Half my waking life was spent travelling on trains. I ate my breakfast on trains, did my reading, made notes, ate my lunch, caught up on sleep. I'd sometimes wake up and forget which train I was on, which direction I was travelling, where I was going. My mind was usually far off in the mist, tracing the fortunes of long dead kingdoms, reading the inscriptions on tombs.

There was mild piss-taking from people I was at school with when I bumped into them in Aberdare, me looking as poverty-stricken as I actually was, them dressed head to foot in labels, taking shopping back to the Audi. This was the 90s, there was lots of credit around, everybody was up to their necks in it. I'd never been into that style, the labels and the bling and the fake tan, even before uni. I was always the alterno-girl, with the black jeans and the hippy skirts and the Docs, even before that kind of thing went mainstream. But around now, just after getting the degree, it was all pretty shabby and worn out. I needed new jeans, new skirts, new shoes, new hair, new everything. Not that I wanted to change my style, get myself an orange face and fake lashes or anything like that. It's just that if you're going to stand out, it works better if your clothes aren't exactly the same ones you've been wearing for the last five years. It's too easy for them to call you a scarecrow then, which Adele Porter actually did, smiling warmly as she did so, when she saw me shopping for vitamins in Holland and Barret. And when I'd been doing the weekly shop with my mother in Morrison's and we went for food in The Bute, who comes across to say hello but Lee Coburn, who used to torment me at school with putrid and unwanted suggestions for improving my sex appeal. He was a manager at Sports Direct in Merthyr now. He told us all about it but I can't remember a single thing he said beyond the word bonus. Then he asked how I was getting on so I told him. Got a First, studying for a Masters, living with my mother. No, no car. No money. He laughed and said, "Christ love, I'm glad I wasn't clever enough to go to uni." My mother wet herself laughing.

I didn't hate these people, I should say. I didn't envy them either. When I thought about Aberdare, about the whole Cynon Valley, I saw all our lives, every feeling, every thought, every word and deed, contained between the walls of a rambling groove; the groove carved by half a million years of glaciers the size of mountains moving south; the last of them melting away, grass and moss and trees growing thick in the u-shaped troughs they made; rivers and streams, heron and kingfisher, hawk and falcon, squirrel and hare and otter, barely any people, for ten thousand years; one of the wild places of the world, the treacherous woods you enter if you step off the fairytale path, sunk deep in green, too boggy to farm, too twisted to settle; then a two hundred year blip, a scramble for minerals buried in the mountains, fills the random groove with more humans than have crossed these two rivers, Dare and Cynon, in ten millennia; now that era too was over, the people it brought were melting away to the south; the green was encroaching on the tracks and traces; the streams were reverting from dead black glitter to clear silver, waders were catching fish; the gouges and the tips and the tunnels were sinking back into the green; Aberdare would end up a dead name, like Robertstown, referring to something built and destroyed long before, and all this would go back to being one of the wild places. So what the hell were we all still doing here?

I was starting to feel a bit sort of nothing about everything, or everything modern, everyday life, the here and now. I'd even stopped watching reality TV. The new series of Big Brother came and went without me noticing. The only things I watched now were history documentaries. Well, and Derren Brown, I loved his stuff.

My uni friends had all sort of evaporated by now. The same thing had happened when I left school, or whenever I changed jobs. It was happening again now. Helen and Julie, Rupinder, Jay, Alex and Steve, Danny, my sort of ex, they'd almost faded out, just a year after we all graduated and I promised to stay in touch. None of my friendships were ever strong enough to survive a transition, everyone just floated away. I couldn't say why.

I was happy enough though, don't get me wrong. To be honest, I couldn't really imagine looking round a castle with someone else. Having to talk to them, listen to them, instead of just looking at the stuff. Or standing on an iron age site, a hill fort, looking down into the valley, no sound, only the wind whispering and the birds calling – and just because someone else is there you've got to ruin it with talk. I tried to see it in more positive terms but I failed to convince myself. I just couldn't imagine it. Very often, I paid for the audio guide tour, with the headphones.

Anyway, there was this librarian I was sort of mildy obsessed with. His name was Will and he was twenty nine. He worked at the humanities library at Cardiff Uni. I did some shifts there, he was sort of my line manager, one of them anyway. He was slim and tall with thick dark brown hair and he talked a lot. The women all loved him. He was funny though not quite as funny as he thought. Well, they never are, are they? He had a good look though, kind of a classic look. He wore skinny dark blue jeans and you never saw him in trainers, he always wore leather boots. His shirts were always good, maroon or deep purple or blue, and they always fitted him perfectly, nicely tight across the chest and stopping, untucked, just at the hip. His eyes were green and twinkly, his grin was cheeky. If you ever happened to be up close to him, like the time I helped him resolve a paper jam in the tiny photocopier room, you could just make out that his aftershave was the good stuff, not Lynx. I didn't think he fancied me but I knew for sure that he knew I fancied him. I sometimes got flustered when we were chatting in a corridor. I was full of pent-up lust. There were moments when literally all I wanted out of life was for Will to turn up at my door late one night and fuck me senseless. Preferably a Friday night, when my mother was out with the darts girls and I was all wet and alluring from my bath.

Anyway it was no good, he had a girlfriend. Cerys. They lived together. No kids though. So there was always the chance they'd split up. I tried to gauge the likelihood. It seemed a pretty stormy relationship. He did lots of routines about him and Cerys rowing all the time, her insane jealousy. And we all laughed, the girls in the staff room, when he was doing his Cerys material.

He turned up to work one day with his wrist in a splint. When we asked him about it, he said this: "A woman in a bar came up to ask where the toilets were, the missus didn't like it so she broke my wrist." No-one was sure if he was joking or not, but he just smiled his rueful smile and said, "Well, I guess you can take the girl out of Blaendulais..." Later he walked the story back and told us he'd actually fallen over drunk. Everyone laughed again. But the next day when we were getting cans from the machine Will confided to me that the reason he'd fallen was because Cerys pushed him over some bins on the way back from the pub. "We shouldn't drink together, me and her," he told me. "Only one of us should be drunk at a time. Or it goes bad."

So it all seemed quite volatile. Sometimes he looked miserable. There were phone calls from Cerys that sent him scuttling outside, scowling. He made lots of jokes about how unreasonable she was, how she flew into a rage, shouted and screamed. In dark moments I imagined that what he was leaving out from these stories for the sake of decency was all the amazing sex they were having when they weren't rowing. She probably shouted and screamed her way through that too. Lucky bitch. I didn't know enough to make that assumption, really, but it crept up on me sometimes as a slightly depressing certainty.

So then they did split up, Will and Cerys. It wasn't the first time but she'd gone back home to her parents and apparently she'd never done that before. Will seemed pretty upset and he got a lot of sympathy at work, which he obviously enjoyed. I'd say the percentage male/female split at the humanities library was about 30/70 to the girls. Some of the men seemed a bit uncomfortable with being out-numbered, but certainly not Will. He blatantly loved being surrounded by women. Looking back, that was a big part of what made him attractive. To enjoy being around women like that, to have fun with us, let us take the piss a bit, give it back to us a bit, but all so light and funny, never aiming to hurt and never taking offence, all this made him seem like a real man to me. I realised I had a definite crush on Will. It was the first time for a long time I'd felt like this about a bloke.

So the weeks went by and he was still single. It looked like it might really be over this time. I wondered what, if anything, I should do. But then he started going out for drinks after work and that changed everything. We'd all go, a big pack of us. Yes, me too. This sort of party gang developed. Friday nights mostly and usually around Cathays, in the Woodville or the Pen and Wig, the student pubs. There was boozing and there was bad behaviour. Looking back, what we had in common was that we were all either single and a bit desperate, or in relationships that were on the slide. Apart from Zoe, who was neither, and just wanted to let her hair down after years of being sensible. I got caught up in it a bit. Well, a lot. I'm not really into that kind of thing, in general. I'm useless at small talk, it's just embarrassing. So I drink too much to compensate, and I talk a load of crap, wear myself out, and have to spend the next fortnight in bed. But it's funny how a change in just one colleague's relationship status can act as a catalyst on a whole office full of people.

Of course I always had to catch the last train back home. That was at ten to eleven so I was leaving early, baling out while the night was still young. They were all staying out, Will and everyone, they were going on somewhere else. And I'd be on the train, half-cut but not quite pissed, with all the sweaty bellowing valley boys, nodding-waking-dribbling all the way back to Aberdare. There was nothing left for me at home really. The girls I'd been friends with at school, before I went off the rails, had all left the valley a long time ago. The girls who'd stayed there were on their second or third kids. We didn't have anything in common now.

I wondered if I was turning into that cliché, the bright working class oik who gets into university and turns into a middle class snob. It's a pretty well worn storyline by now. The little oik has to go back home for a visit and it ends badly. Oik displays contempt, disgust, is pretentious, and at very best can only manage a condescending smile, a patronising phrase. There's usually some tragi-comic confrontation-with-the-parents scene. It's been done a million times, to the point of parody. Maybe because it was so obvious, so expected, I was really keen for it not to happen to me. Who wants to feel their entire life is just following a boring old script? Plus, it wasn't as if I'd got my degree somewhere posh. I'd gone to the local university, because I genuinely thought that's what you did when you filled in your UCAS form, you picked the ones closest to you. And this local university, where I spent three of the happiest years of my life, where I learnt so much about the world and about myself, had only just changed from being a polytechnic, prior to which it was a technical college, having started life as the South Wales and Monmouthshire School of Mines. To a certain kind of person, that history would be hilarious. I knew that to some people, I hadn't really been to university at all. To them, my First wasn't a real First. My whole experience would be seen as entirely contained within the tiny circle of Welsh irrelevance. They wouldn't see that I had made any real movement at all.

I kept seeing things on the walk back from the station, like a homemade poster in the window of a hair salon in support of Cwmbach boy Rhodri Watkins who was through to the semi-finals of X Factor; two blokes outside Wetherspoons squaring up for a fight, another bloke between them trying to break it up, all three in their fifties; graffiti on the back wall of PLACEHOLDER: Bong On 9T4, Fuk Da Law Smok Da Draw; the sound of a pub full of people singing along to John Denver's Country Roads; a plump and scruffy student in a hippy skirt and Docs tottering back to her mother's house. What we were even doing here, any of us? The thing that had dragged us all here, the money, was long gone, shut down, dried up. Here was Wellington Street, so empty and long, and so quiet, with dark wild bushes on either side growing thicker every year. A century and a half ago this was the main drag, and there were streets and streets of houses running left and right, all the way to the Gadlys, with heavy barges moving slowly down the canal, men and women in lit up trams coming from the bridge on the Dare side. That was Robertstown, a bustling industrial slum full of mostly young people, life expectancy 50 at best, notorious for being nonconformist in their religion, revolutionary in their politics, energetic in their sexuality, and obstinately Welsh in their language. Back then the name Robertstown was splashed in London newspapers as a byword for the latest moral panic. It's not much more than the name now, still there on maps and signs, designating a long empty road, a rump of undemolished terraces, and a cheap furniture warehouse.

So I moved in with my new friend Zoe who was doing a PhD and lived in a rented house in Cardiff. I first met Zoe when we were both shelving books in the same section. I was leafing through a book on Frida Kahlo when I heard the squeaking wheels of a trolley. A girl around my age. New girl. We said hi, I helped her get the hang of the shelves, then she said she liked my boots. They were brand new, these boots, leather, cherry red, with buckles and zips, from Eccentrix in the High Street Arcade. Cost a fortune. They were part of me updating my wardrobe and although I kind of loved them, I wasn't a hundred per cent confident in my own taste. So of course I broke into a real smile and said thanks, getting back in return my very first Zoe beam. She had the best smile, still does. A very open face, with huge eyes, and you can see every twist and turn of emotion running across it. I always told her she'd be useless at poker. I once watched her completely blow a birthday surprise without saying a word. She was mortified, clapped both hands over her face and walked backwards out of the room. Bless her, she's the worst liar I've ever met.

I'd started staying over with Zoe if it was going to be a big night, someone's birthday or whatever excuse came up. I'd slipped back on the drinking since getting my degree. It wasn't out of hand, like when I was eighteen and drinking vodka every day, but I could still put it away. You know how in any group of boozers one idiot will always be rallying supporters for another round of shots, even when it's 3am and everyone's already so ruinously wankered they can barely speak? Well that idiot was me. Zoe was a bit more of a lightweight but determined to stay the course. She'd been a very studious, sober girl up until now, A Levels, degree, masters, now doctorate, with no gaps in between. It was pretty clear she wanted to let her hair down a bit. I made sure I always kept an eye on her, she could get quite random and messy when she was pissed. She wasn't the most worldly of people. She was very funny and cute when she'd had a drink, you know, not a pain in the arse type drunk. But she'd misread signals from other people, or just not see them at all. She definitely needed someone to watch her back.

So we'd end up tottering along Wyeverne Road, me with my arm around Zoe, holding her steady, guiding her round bins and dog turds, keeping an eye out for pervs, while she burbled away about this and that. She was a very talkative drinker, Zoe, wide-eyed and constantly surprised by things. I felt like her cynical big sister, even though she was older than me. One night we saw a man looking totally out of it, sitting on a bench in PLACEHOLDER. I had to stop Zoe from going over to him, she was worried he was ill, needed help. She looked like Florence Nightingale with a Brecon Carreg bottle instead of a lamp. So I clutched her tight to my side and told her to leave him, he was just stoned out of his mind. Zoe said, "Well, maybe, but how do you know for sure? He could be having a brain haemorrhage." I told her to look at the bench, next to the man, and she saw his little glass pipe and his lighter, bits of tinfoil. "If he is having a brain haemorrahage," I told Zoe as we walked away with our arms linked, "it's one he's paid good money for, so let's just leave him to it, right?" And Zoe looked at me and gave me her full beam. I remember she said, "God, Anna, where the hell would I be without you?" "Probably chained up in a brothel," I told her. And along we went to Fitzroy Street, cackling away like a couple of old witches.

A few months after that Zoe told me her landlord would be looking for a new tenant for the attic room soon. A month later I moved in. Zoe had never seen I, Claudius. I remedied that. It was part of our hangover routine. We'd drink coffee and eat pains au chocolat from Sainsbury's and watch I, Claudius. In fact, just the other day I got a text from Zoe which read: QUINCTILIUS VARUS, WHERE ARE MY EAGLES?! Zxxx

So one Friday night we all ended up in this over-priced cocktail bar on City Road, six or seven of us, about 1am. Zoe and I happened to be sitting opposite Will, the three of us leaning in close over a tiny circular table to be heard above the music. He was on great form that night, Will. He listened to the latest installment of Zoe's catastrophic love life with great interest and had a lot to say about it all. He told Zoe that none of it was her fault and she deserved much better. He said, "Look at me, after all this Cerys stuff – I'm bruised, sure, I'm bruised to holy fuck, but I'm not bleeding." I'd almost say he was cosying up her to her but I didn't get that feeling, it read more like a supportive friend thing. Also, I noticed that he was addressing quite a few of his comments on love and heartbreak and so on directly at me. As in, right into my eyes. So of course I began to feel ridiculously excited and kept insisting on more drinks all round.

When men try and chat you up, it's almost always boring, and forced, and makes you cringe. I mean, I suppose I'm partly to blame because I'm just no good at small talk. And chatting up is just a subset of small talk, isn't it. You're not really talking about anything in particular, there's nothing to cling on to, and it's all crappy. You're just wafting these threadbare festoons at each other in desperation. So I tend to just sort of clam up. Will, though, he was quite good at it.

Zoe was talking to Hannah so now Will and I were just looking at each other over our tiny table. He grinned and beckoned me to lean in closer, so I did.

He said, "I'd like to try something out on you, if you don't mind."

So I raised my eyebrows at him and said, "Um, okay..?"

To which Will did a mischievous little chuckle and told me it was a kind of personality test.

"Don't be worried though," he said, "it's not serious, it's just a bit of buggering about, of no diagnostic value.

"Well that's a relief," I said, and he chuckled again.

I could smell his good aftershave – I'd asked him earlier and he told me Issey Miyake - and he had about half a centimetre of stubble on his chin and around his lips. I could see the dark hairs on his chest poking over the top of his shirt. Plus I was half-cut. Plus it had been a bloody long while since I'd even been near a bloke. So you can imagine, can't you?

Will's idea turned out to be quite good. Basically, you've heard that thing – if you could have as your superpower either being able to fly or being able to make yourself invisible, which would you choose? It's like those crappy questions you get on Facebook that are meant to reveal some essential truth about your personality based on a seemingly throwaway choice you make. Well, Will said he hated the superpowers thing, it was a fix, a swizz, because all the traits associated with flying were really good ones – success, confidence, flying high, reaching for the sky, freedom, the great beyond. And then you had invisibility, said Will, which was the choice of creeps.

"Think of the kind of stuff being invisible would allow you to do, would invite you to do. It's nothing very noble, is it," he said. "It's sneaking around, it's hiding, not being upfront and honest. It's peeping toms and crooks, it's sneaks and spies and saboteurs, it's eavesdroppers and shoplifters and pickpockets. Invisibility appeals to the voyeur, to the nosey parker and the perv."

So it wasn't really much of a choice, he said, in fact it was a complete fix and he'd thought of his own, much better alternative. I was laughing at all this, by the way, and reaching across to maul his arm from time to time. This was a good deal better than your average chat up, I was thinking, and even if it wasn't a chat up I was having fun with a silly man on a Friday night and and he was making me laugh so just go with it, just enjoy yourself for god's sake.

"So what's your own, much better alternative?" I asked.

"Okay," Will said, "here's the thing. Some old fella down the road from you, a mad professor type, he's built a time machine. It's in his garden shed and he's invited you to have a go."

"So this old man is trying to get me to go into his garden shed with him?" I said. "I don't think I believe he's got a time machine in there, Will, to be honest. I think he might have other reasons."

"Fair point," said Will laughed. "Make it your grandfather then. Someone you trust."

"How about my grandmother?"

"What's the matter, you don't trust your grandfather?"

"Well, yes I did trust my grandfather and he did make things in his shed, but he's not alive now so..."

"Oh christ, sorry," he said, wincing. "I haven't got any grandparents left, as of last month. Life's a shit, innit. Okay, so you go into the shed, there's the time machine, and your lovely old Nana is inviting you to be the first to have a go on it."

"First?"

"Yup. First ever trip, the maiden voyage. And she wants it to be you, her favourite grand-daughter."

"Her only grand-daughter. So, I'm like a sort of guinea pig? My Nan wants me as a guinea pig?"

"Yeah, I suppose so," Will said. "But in a very loving way."

I did one of my stupid big honking snorting laughs all over him at this point. He seemed to enjoy it, this muffled explosion of me. By now, fed up with shouting over the music, Will had come round the table and we were pretty much squeezed together. We were laughing at my laugh. I told him my dad always called it my walrus mating cry. Will said it was unashamed and life-affirming, that it was "one of the great laughs". What a bloody charmer, eh? I was starting to feel pretty damn good about myself, doing all the sexy banter, all the flirty-flirty stuff. I'm a bit slow on the uptake sometimes, I don't always read the signals. This, though, with Will, this Friday night, I felt bloody fantastic about everything.

"Alright, forget about your Nan and the shed and everything," Will said. "You've just got hold of this time machine somehow, doesn't matter how, okay? But you can only use it once, I mean for one return trip. There and back, then that's it. So the question is – where would you choose to go, the future or the past?" Then he frowned. "Actually this might not work so well on you because you're a history student, not a normal person."

Anyway, to speed things up a bit, that question of Will's led to a conversation between us that went on until we all got chucked out of the place at about two, and then continued in the taxi. I told Will I'd choose to visit the past, of course, either to 5 or 6AD, just after the Romans left, just to see what it was really like. Either that or all the way back to the start, before agriculture, before cities and empires, to when we were still nomads. Just to see if we were any happier then. We talked about that for a while, the distant past, then Will said if he had the one-trip time machine he'd definitely choose the future, no question at all. At least two thousand years, he said, either that or a few million, because he wanted to see how it all panned out. So then we talked about that for a while, the far future.

It was all quite slurry and rambly and drunken, of course, but it just kept going, and we got on to what all this might for our respective personalities, and about the state of the world in general, whether things were getting better or worse, whether there was any hope for the human race, and if not, when exactly had it all gone wrong. Suddenly we were in Fitzroy Street and Zoe was getting out of the taxi, waving goodnight, stumbling on her doorstep, trying to find her key, fiddling it into the lock, waving goodnight again, and falling into her hallway. I was staying in the taxi with Will, who was in the middle of saying that there never was a golden age, it was just a fantasy, there was never a time when everything was in harmony and everyone was happy, but that there could possibly be one at some point to come if we didn't blow ourselves up or make ourselves extinct through climate change. And also there was Paul the spotty Australian IT boy who was fast asleep and snoring and had to be shoved really hard to wake him and get him out at his place in Riverside while we went on to Will's flat, quite a nice one, with a balcony overlooking Pontcanna Fields.

Six months later to the day we were in Rome together. It was my first ever visit and it was fascinating, overwhelming, beautiful. It was early October but so warm, the sun so strong and bright. Everything seemed golden, everything seemed glowing. Will and I were celebrating the half year anniversary of the night we got together. We'd been wandering around all day, talking and looking. We'd had lunch at a ridiculously over-priced tourist trap by the Tiber, and decided it was worth it for the view from the terrace. The plane trees along the river had all turned bright orange and were dropping their leaves into the water. We walked from the Circus to the Colosseum, across to the Forum and up the Capitoline Hill. Talking and looking all the time, me with my guide book, tracing out the shape of the ancient city, Will trying to imagine what would be left of modern Rome in a few thousand years time, picturing future tourists nosing round the remains of the airport, the shopping mall, the office blocks. We were looking down from the Capitoline at the Forum, his arm round my waist, mine round his, and I remember us both saying the same thing at the same time, the same sentence – Nothing lasts forever. We were both delighted, of course, as though we'd come from different angles to arrive miraculously at the same spot, and we kissed, because that's what it's like when you're in the honeymoon period. It struck me that what we were having was a continuation of the same conversation that we'd started in that over-priced cocktail bar in Roath. The idea filled me with strange new feelings. The silly word 'soulmate' kept jumping out at me. I wondered how long a conversation between two people could last. Maybe a whole lifetime?

It was an odd match really. We were different in lots and lots and lots of ways. We hardly agreed on anything. And at first, I think we were both kind of fascinated by how different we were, despite having quite a lot in common. Here are some of the things we had in common:

smallish working class valleys hometowns, Aberdare and Glynneath

stopped feeling that we fit in to our respective hometowns at around the same age, 14

each had an older brother who got married and moved away, his to England, mine to Monmouthshire, which amounts to the same thing

divorced parents, dads who'd left home when we were teenagers and slightly difficult relationships with our mothers

both went to Welsh school, though Will didn't really keep up the language now

first in our family to get a degree, Will having achieved a 2:2 in psychology

we'd both been members of the Green Party at some point, although neither of us was now

similarly miserable teenage years, greasy depressions spent in cocoons of totemic books, music, films, art, clothes, comedy, metaphysics, magic, comics, etc, evolving into a dense and intricate personal para-reality to which the everyday world of bus stops and dog shit was just a mundane and laughable annexe.

It felt as though we'd started off in roughly the same place but had headed in different directions. We kept coming back to the past/future thing, it was like some structuring principle we used in thinking about our differences. Here are some differences we noticed:

Favourite films - me: Agora, with Rachel Weisz as Hypatia, Elizabeth, with Cate Blanchett, Mel Gibson's Mayan epic Apocalypto, and yes Gladiator. Will liked Bladerunner, Alien, Akira, the first Matrix.

Books/authors – On holidays from my study reading I liked Sarah Waters and Hilary Mantel. One of my old favourites was Alan Garner, ever since I read The Owl Service when I was thirteen. As a kid I read and loved all of Tolkien to the point where it affected my dreams and I saw epic battles on my walk to school, raging in the morning clouds that cling to Maerdy mountain. Will had never read any Tolkien but had an impressive number of multi-part space operas under his belt, his favourite being Iain M. Banks' Culture novels. He could quote huge chunks of Douglas Adams and he also loved William Gibson...or was it William Burroughs? One or the other anyway. He mostly read non-fiction now, a lot of pop science, Freakonomics, Malcolm Gladwell, Dawkins.

Music – I listened to Fairport Convention and Nina Simone. Will listened to German minimal techno.

The state of the world today – we both agreed that everything was in a right mess, massive poverty, total exploitation, greed, capitalism, eco collapse, extinction event imminent, and all caused by us, by humans. Where Will and I differed was in the directions we looked for solutions. It was the time machine again – he went forward, I went back. Will agreed that humans had caused damage to the world by being too clever – fossil fuels, nuclear weapons, international tourism, etc – but he said turning the clock back was impossible, undesirable, and wouldn't work anyway. It was too late in the day to return to our nomadic roots, he said, we were seven billion people mostly living in cities now. The only way to solve the problems our cleverness had caused was to get even more clever. Will was keen on technological fixes. Sometimes he sketched out a sort of post-market utopia in which we've abolished scarcity, outgrown the lizard brain, conquered evil and greed with intelligence, and built a new world based on a new understanding. We'd first heal our planet with incredible new machines, and then we'd move out beyond Earth in peaceful waves of creative colonisation, slowly evolving into children of the stars. And I'd needle him by asking who was going to own these machines, who was going to control them, who was going to build them and who was going to profit from them. Same as ever, I'd say – billionaires. Same shit, different day.

And me, I still do the same now, I dig back to older societies and pre-modern ways of life, tribal ways and folk narratives, non-profit motives, sustainability, to structures of feeling abandoned on the road to modernity, old medicines for our modern sickness. It's all very vague and woolly, and not at all historically supported of course. It's just a feeling, really, and it's probably not true. Will was never very open to any of this stuff. His closing flourish was always something about whatever the old days might have had going for them, it was basically a kind of blissful ignorance, hardly to be envied, and besides, no-one – not even you Anna! - would genuinely want to live in any era of human history before reliable anaesthetics were invented.

As I say, we hardly agreed on anything. But in the early days that was part of what made it fun. We used to debate things, it was what we did. And whatever we were talking about, at some level you could sense that same old past/present thing, his time machine thing. I thought it was really quite clever. It seemed to me he'd hit on something essential about his approach to life and mine, and the differences between them. I thought other people might recognise something of themselves in it too. At the time, I thought Will didn't realise how clever he was. I thought I detected a lack of confidence hiding under his verbal swagger. I decided I'd see if I could help with that, to encourage him. After all, he was giving me a boost. He was so attentive, he really listened to me. I felt myself expand when we were together. I thought maybe we could be good for each other. This is all faintly hilarious to me now, of course.

So we were at a cafe opposite the Colosseum having coffee. We sat at a little round table on the pavement with everyone going by. I tried to order two double espressos but I messed up my pronunciation and the waiter brought us singles. Will beckoned the guy back over, and the waiter smiled and said, in English, "You want milk?" Will gave him half a grin, shook his head, and said, "Nessun latte – doppio – prego," and they both laughed, the waiter nodding and whisking off our tray. Then Will turned back to me and grinned his bloody adorable grin. I was thinking we'd have this coffee then maybe I'd suggest we pop back to the hotel for an hour or so.

"Milk indeed," he said. "He must have taken us for a couple of weak ass English milk weeds."

I laughed.

"You know what you should do, Will? You should be a writer. You should write something."

"Ha, what?" he said. "I don't think so. I ain't got nothin' to say."

"You've always got something to say, you idiot."

"Well, yeah, but it's all bullshit really, innit, when you come down to it."

"Well, yeah, but that needn't matter. Look at some of the crap that that sells."

"Mmm, fair point," he said. "But, no, I really don't think there's anything in my particular brand of bullshit that would sell."

"I don't know," I said. "What about your time machine? I'd say you could definitely make something out of that. It's good. It gets you thinking."

"You reckon?"

"I do, yeah. I think you could make that into something, a story, something funny and clever," I said, "like you."

And he leaned across the table and kissed me. A big kiss, slow and warm, right there with everyone going by on the pavement. When I opened my eyes again he was smiling at me, his eyes were so twinkling, he was so handsome, and golden autumnal Rome was glowing away behind him. I felt so good, so happy, more than happy. It was all so much more than I'd expected. I whispered a suggestion to him and, after our espressos, we popped back to the hotel for an hour.

Can we just skip for a minute back to that first night I spent with Will, at his flat in Llandaf North? So it's stupid o'clock in the morning, we've been getting through his Scotch, we're almost at the point where you drink yourselves sober, and we're out on his brown bolted balcony. I'm squinting at glimpses of the Millennium Stadium and the BT building through the trees. A mile and half away, the city centre. The rain is falling but the air is warm and smells sweet. We haven't had sex yet and we're still not quite sure if we're going to. Will had a text from his ex earlier – at two in the morning! - and it sort of made the atmosphere between us a bit weird. So now we're on the balcony, talking.

I remember telling him that all his Bladerunners and his Aliens and his cyberpunk whatever, all these futures he was into were all horrible. No-one would want to actually live in any of them. These are dystopias. It's satire. The future in most of these things he loved was some crazy exaggerated version of today's world, with all our problems pushed to the limit. I remember him grinning as I pressed the point.

"Well," he said, "not pessimistically but just being ojective, it's probably more likely we'll fuck it all up and ruin the world. Than not. Realistically speaking."

"That's funny," I told him, "you love the future but you don't even believe in it really. Your best guess is it's going to be even worse than today."

And then he told me this story. There's this couple, he said, and she's like you, she loves the past. And he loves the future. And one day this time machine really does turn up, but you can only take one ride each in it. Just one return trip because human minds can only deal with the experience once in a lifetime. She goes first, heads into the past, and comes back one second later in a state of deep depression and disillusionment. So he has a go, heads into the future, comes back one second later, just as depressed and disillusioned. They conclude from their experiences that the present is as good as it gets, so they enter into a suicide pact. As for living, they say, our spambots can do that for us. But then he remembers that he's already visited both their graves in the far future and the dates on their headstones made it clear they're going to live for several more decades. So they don't bother, they just sell the time machine on eBay and split up. She later marries a quantity surveyor and lives in a big beautiful house that becomes a millstone round her neck, while he moves to Kefalonia and drinks himself to death.

So it was a funny little story with a bleak punchline. It made me laugh. I asked him if he'd just made it up and he said yes, he'd made it up right there on the spot. That's good, I said, that's funny. You should write that up. That would make an amusing little story, I said. Will just shrugged, which was something he did a lot, a sort of French shrug, very minimal, with a slight downturn of the mouth and uplift of the eyebrows, comme ci comme ça. I told him he should write a whole stack of little stories like that, make them into a book. He grinned and said he'd just wanted to make me laugh. I pulled him to me and that was it. We were both a bit too drunk and tired really but it was nice falling asleep and waking up tangled with him.

.

I kept telling him to write his time machine story but he never did. I couldn't understand, because he kept saying he wanted to write. I mean, I thought it would be a good little exercise to get him started. After all, he had the whole thing there, he just had to write it up. But he didn't write it. He didn't write anything. If he did, I never saw it. He probably got sick of me going on about the bloody story.

As I say, this was twenty years ago, when I was a student. Let's fast forward now. At nine o'clock this morning I was in Rome, at Ciampino Airport, waiting with a couple of colleagues for an EasyJet flight back home. We've been at a conference in the Sapienza for the last three days, during which time we've all eaten a huge amount of food, drunk a decent amount of wine, and I've given a paper on some of the connections between Macsen Wledig of the Mabinogion and the real life emperor Magnus Maximus. But the most memorable part of the trip, the thing that will give this particular trip to Rome its unique stamp in my mind, happened last night, after dinner, when we watched a wild boar running along the Via Cavour. We were at a pavement cafe, six of us. There was a commotion on the street, some shouting, an engine revving. I turned in time to see this animal, a boar, running at top speed up the middle of the road, heading towards the railway station. The shape of its body as it ran, it was perfect, exactly as you'd expect a running boar to look. Like an ancient painting come to life. There were two boys on a red Vespa chasing it. The boy on the back was filming it all on his phone. We turned to watch them go, not just the six of us but everyone in the cafe, the waiters too. One of them ran out on the road and called to the boys. From further up the street came a volley of car horns. In all my trips to the city over the years, that's something I've never seen before. I said as much over the table as we settled again to our dinner. Gabi, our host from the history department, smiled and said, "Perhaps next time you come there will be also be wolves in the streets."

Now we were all heading home, me in the company of Ian Bamford and Maria Shields, both of whom I've worked with for almost a decade now. Maria, who has good Italian, was reading a story in the paper, translating bits for us.

"'Resident Salvatore Golino said 'Rome has become an open sewer, a scandal, full of rats, foxes, wild boar and rubbish. We are drowning in trash, we can’t take it anymore, and our government does nothing.'"

I thought, yes, the city does look a bit messier than usual these days. I'd sort of noticed it the last few times I visited, though it was hard to be definite because Rome has always had its messy aspect, and especially around the station. But now the news was full of boar sightings, uncollected rubbish, hordes of rats, broken roads, under-maintained buses bursting into flame, escalators collapsing in the metro. Maria said something like, See, you stop investing in public services and before you know it the streets are full of boar. The thought of this decaying Rome, sinking back into the wild, felt familiar. A dystopian vision, the future of the great cities, mismanaged by kleptocrats, going feral. It was like one of his, Will's. That was his kind of thing. A memory then of my first visit to the city, when I didn't even notice the messy modern aspect because my eyes were so greedy for the beautiful past. And, yes, of course, for him. I remembered how golden it all looked, at that round table opposite the Coliseum. Years ago now, decades. Not worth remembering really.

So I asked Ian what he was reading. He held up the cover of his slim paperback. It was called Minimum City, a collection of short stories by the American author Todd Keever.

"Oh, him," I said, grimacing.

"Not a fan then?" Ian said.

"I've never read anything by him," I said. "But I did read an interview with him in the Guardian once and, well, let's just say I wasn't tempted to venture any further into his mindscape."

"No?"

"No," I said. "Quite the opposite."

"I mean, he has become this sort of awful reactionary figure now," said Ian, "and each new novel is worse than the last. I mean he's really scraping the bottom of the barrel now, all this stuff about Muslims and trans issues and masculinity, it's meant to be satire but it's just awful."

"You're really selling him to me," I said.

"Well, to be honest I wouldn't recommend anything by him except for his first novel, The Drift, which is still pretty funny and sharp, and this, which is about half good and half not so good."

He held up the cover, which had a very mid-90s design, blurred digital abstract, with words Deeply, darkly funny – Chuck Palahniuk on the bottom left.

"I mean, it's not profound at all," he said, "they're more like comic sketches. It's from very early in his career. Twenty eight short stories, some of them just a paragraph long. Sting in the tail stuff, although it's more of a dagger in the back really. There's one called The Return Trip."

And he told me the story. Bet you can guess how it went. It was one of the shorter ones. When Ian had finished telling me the story, I asked if I could take a look at the book. I turned to The Return Trip and I read it. As I did, I felt my mouth, my whole face, turning into a big grin, as though someone in the back of my head was turning a huge rotary handle. It was all there, and I mean all of it. The narrator starts with a riff about which superpower would you choose, flight or invisibility, and declares it a fix. Then he suggests his alternative, time travel, would you choose past or future. And then we're straight into the story, the couple with the time machine, her going to the past, him going to the future, both coming back depressed, the failed suicide pact, the break up. It was, as I say, all there. Right down to the spambots line. Grinning very widely by now, almost giggling, I flipped to the front to read the publication details. The Return Trip by Todd Keever was first published in an online magazine called Young Boasthard's four years and eight months before that night I went home with Will. It was collected in Minimum City and published by Harper Collins in the UK seven months before he told me the story on the balcony of his flat and passed it off as his own. My shoulders started shaking, I put my hand to my mouth, snorted, and that boar went running through my mind, and somehow the boar was Will. Haven't seen him or even thought about him for years, decades. But that was him alright, running along the Via Cavour. I started giggling and my inner voice said, Oh look there goes Will in such an arch and campy tone, and so totally Aberdare, that I couldn't hold back any more and I burst out with one of my big walrus laughs.

Coming next: Lie #2

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

Based on the latest scientific research.

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

A compilation of funny Scandinavian TV commercials

1 note

·

View note

Text

Selection of stills from the film Minimum City (2012, written and directed by Claire McKay)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Birds Hell (Reprise): The Book of Job

Extracted from Transcript C

Right, let's have a go of this one.

(Inhales from e-cigarette, coughs)

God help, that is harsh.

(Coughs, spits, laughs)

What the hell was that again? Lychee and Raspberry, for god's sake.

(Blows nose, clears throat)

Think I'll go back to the bloody Zestappeal. Anyway, where was I? Christ knows. Oh yeah, so car parks, right? Twice in my life I've been sat on the ground at the edge of a hospital car park, totally brainshot and unable to move. Once was when my brother died, back in 1987, in the old East Glam Hospital, and I was fifteen. Twice was a little while ago at the new Royal Glam Hospital when those birds scared me and all the cars were dead. And what these two car parks taught me was this, right?

When everything's gone wrong and fuck all makes sense, if your brain is smart and knows what's good for it, what it'll do is try to ignore everything. It'll try to get you back to your distractions ASAP, whatever they are. It'll say, hey so life's got no inherent meaning but you invest it with your own meaning and basically just seize the day, have fun and be kind. (Laughs) Oh, and it'll also do that if it's a particularly thick brain. (Coughs) Yeah...and...then it'll get all obsessive over some hobby or other. According to the tastes it was brought up to enjoy, you know. Like golf, or fucking, or politics. Maybe faith, religious faith, that's an old favourite, right? (Sniggers)

But my brain, for some reason, this is what I learned in those car parks, doesn't do that. Distractions don't work, they don't distract. Stupid thin things they all seem, stale, flat, and useless. And everything is just a distraction really, every possible thing, love and pleasure, all just a distraction from this truth I'm drowning in right now. My brain, in those car parks, just goes numb and I start to see things in the landscape beyond the perimeter fence and I just don't know where or what I am.

Actually, I remember this Jehovah's Witness who came round the house one day, a few years ago now, and she was on the doorstep, you know, and I can rarely resist shooting the shit with them when they knock. I think they see me as a challenge. I usually talk about the Book of Job. Because that doesn't exactly show the non-existent bastard in the best light, does it?

I mean...(Laughs) it's all about God gambling with the Devil over the soul of the best man on earth, right? They have a bet and the stakes are this poor fella's eternal soul. Which is fucked up for a start, right? Because if He's God, and God is Love, then why did the bugger take the bet? Not very loving, that, is it? Kind of suggests the whole thing is just a game to Him, right?

Anyway, the Devil says, look here now, Jehovah, show me the best and most righteous man on that beloved planet of yours, and I bet I can get to him so bad that he ends up cursing you, his Lord God.

And what does our loving shepherd tell the Devil? Does He tell him, mate, fuck off, you're being a dick...(Coughs) and anyway, I've got a duty of care here, so no way, no bet, no deal. Back to the infernal realm with you, old son.

No, he says game on.

Knowing full well the kind of shit He's letting Job in for, right, all the delicious death and disease and disaster the Devil has in store.

Game on.

And this is just to win a bet, mind.

(Yawns)

The funniest bit is the ending though. When God's righteous man, reduced by now to a toothless, hairless, multi-bereaved tramp with these pulsating buboes all over his body, sitting in the ditch where his home used to be, when poor old Job finally dares to raise the slightest, most timid, respectful little question to some sympathetic friends as to what the point is of all this devastation, down comes God Himself. There He is, right next to them, in the form of a whirlwind. He's come to talk to the bloke who's wondering why his life has so spectacularly fallen apart. And what does He do?

(Laughs)

What He does is He gives Job the most almighty bollocking for even thinking such a thing. And I mean like a really enormous bollocking. A god-sized bollocking. Makes it clear to Job in no uncertain terms that he doesn't even get to ask that question. That what's it all about, eh? that everyone asks at some point in their lives, usually when the shit's hit the fan. Don't even dare to wonder what it's all about, says God, only I know that, you're so tiny and bloody mortal, I can crush mountains, so I guess you'd better just STFU.

It's true, check it out yourself, Book of Job, in between Esther and Psalms.

And to back it up, He goes on and on, for two whole pages right, about what a massive big God He is, how incredibly powerful and mighty, how He made everything, and how He holds up the sky and moves the stars and fills every fathom of every ocean (Bellows) so how could you possibly expect to know what my plan is, puny mortal!

And He's a real sort of alpha male arsehole about it too, at one point boasting about His big dangerous monster pets, Leviathan and Behemoth, and talking about how He hooks them through the lips and drags them around on chains. Now that sounds all too bloody familiar, dunnit? Like, 24-year-old Lee from Clydach swaggering around with his pitbulls, Tyson and Facefucker. The god version of that syndrome, right?

And all the time this Jehovah thug is all up in poor old Job's pustulent, ruined, human face, giving it all the sarcastic questions routine, I wonder if you could drag sea monsters around on chains? I wonder if you could hold up a mountain, eh? EH?

So that's essentially God's answer to Job, his answer to the question of why a loving God allows suffering in the world. And the answer is because shut the fuck up, that's why.

Hallelujah!

(Coughs, inhales more nicotine vapour)

And I mean, yeah, God does magic back Job's stuff in the end, his house and all his sheep and that, and he does clear up his boils for him and gives him new kids to replace the dead ones, after the Devil gives up the bet, but still...think of the psychic trauma, the PTSD for poor bloody Job. Because there's no mention of God giving him a merciful mind wipe, like Men in Black, so he can forget the whole twisted fucking nightmare. No, the poor sod has to spend the rest of his life all freaked out, walking on eggshells, never able to relax into it all, even at his kitchen table with his new daughters around him, because he's always totally and horrifically aware that any time it can all be shat on and pissed over, for no reason at all.

Anyway, so I'd spin this out for them on the doorstep, the Jehovah's Nusiances, and they'd smile pityingly at how a lost soul can read the True Word of God and still go astray.

(Laughs)

Or maybe they thought I was the devil, trying to send them astray.

I've got one about the Tower of Babel too...but...maybe another time...(Indistinguishable) All working together...(Inaudible)...must be the only time in the whole of human history, international co-operation (Indecipherable)...too many ruined buildings in this story without that one on top (Laughs, slurps).

Sorry, just eating...daring to eat...a peach.

(Slurps) Or a reasonable facsimile thereof.

No, but the point I was trying to make was this, right? This Jehovah's Witness, she said to me that what will happen is this. When the Day comes, there'll be a final battle between Jehovah and Satan. After a load of terrible armageddon and apocalypse stuff, God will win and everyone who is still alive on the planet will be sorted by the Angels into two groups, the Saved and the Damned. The Damned go straight to Hell, of course, to be punished and tortured for all eternity. And the Saved? They get to stay on the Earth and live forever, at their physical peak, on a planet transformed so it's like the Garden of Eden again.

The way this woman described it...She said that if you were one of the Saved, you could live forever and, you know, inherit the earth. Do all the things you always wanted to do. Like me, she said, I love to knit and what I'd really love to do is start off with fleece straight from the sheep, and then go all the way through preparing it and washing it and dyeing it and carding it and finally knitting clothes with it. To me, that would be heaven. To you, something different, but whatever it is there would be time for. Words to that effect. Nice little lady in her 70s, very slight, delicate features, pale skin, quite ordinary looking, and yet that little bone china head of hers was the container of such a tiny, cosy eternity, she and her saved friends and a neverending supply of sheep.

(Coughs)

It seems so obviously bloody silly but, you know, it kept this little old lady trudging up the steep steps of every house on our side of the street in the pissing grey drizzle. An insane act, surely? But it's working for her you know? It goes to show how far you can go if you really invest in some crock of shit or other. Don't forget, it's all about distraction. Your brain knows the truth, deep down. It knows there's no reason for any of this, no reason and no purpose. It knows there's no God, there's no Devil and there's fuck all when you die. Even that little Jehovah lady, even her brain knew it deep down. But, unlike me, she'd invested in some crock of shit or other, and that kept her happily distracted. As far as she was concerned, she wasn't just spouting nonsense at indifferent strangers in a cold wet cul de sac in a slowly dying post-industrial zone among the impoverished uplands of northern Europe. No, she was on a very special mission (Giggles)...from God...it's quite sweet really.

(Giggles, coughs).

And despite my best efforts as devil's advocate, she stuck with it. Although she never did call back, which isn't like them, is it? Once they've got their hooks in, they keep coming back, don't they? Not this one, though.

I wonder why she didn't call back.

(Laughs, coughs)

#effluent lagoon#roadswim collective#birds hell reprise#book of job#justifying the ways of god to man#problem of evil#satan#God#car parks

0 notes

Photo

0 notes

Text

Three Times He Lied To Me Lie 1.

I was twenty three when I met him. I was back at home, living with my mother, after three years in halls of residence. Here's a list of the places you'd be most likely to see me during the year I was twenty three:

on a train

in a library

at a railway station

in a corridor

at my tutor's office

in my bedroom.

I had literally no social life, unless you count going to the shop for tobacco. My best friend was my I, Claudius box set. On Friday nights when my mother was out with the girls from darts, I'd drink Prosecco in the bath. Sometimes I'd do that on Saturday nights too.

I did go other places sometimes. If the weather was nice you might see me in a castle. Caerphilly was my favourite. Or I might be at a Roman site like Caerleon. And now and again you might see me out of breath at the top of a hill somewhere looking at the remains of an Iron Age fort. I was always alone on these excursions. I'd end the day pretty much as I'd started it, lying in my bed, in my old bedroom, probably watching Gladiator.

I was halfway through a master's in history with archaeology, a two-year course, and I was completely broke. Amazingly I'd got a First in my degree, and my tutor recommended me for post-grad. It was all a bit overwhelming. I was the first in my family to go to uni, you see. Well, my father was accepted at some art college back in the day but he didn't finish the course, he dropped out. Other than that, though, I was the first to go on to higher education. It was quite a big deal at the time. Nerve-wracking. I more or less expected to crash and burn.

Everyone else seemed so confident, so talky, and loud. So English, I was about to say. But that's not fair. I just hadn't met many people like that back then, middle class people. A lot of them hardly bothered going to lectures and they were always incredibly insulting about the tutors. They were always on the piss too. Now me, for the first two years I just kept my head down and my mouth shut. I worked as hard as I possibly could, hoping to keep up. I read literally everything. When a lecturer praised my work, I'd carry that around with me for days like a little glow of fire to ward off the doubts.

Not that I was some kind of nun. My main indulgences were:

thin little roll ups in liquorice papers smoked on the library steps, about one every half hour

a bottle of vodka in my bottom drawer for winding down at the end of a long essay

the occasional lump of cheap hash to see me through the holidays

a boy from Norfolk with nice dark eyes, though that was more trouble than it was worth.