Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

A YOUNG CAROLINE

Caroline Hodgson’s story doesn’t begin in Australia but in Germany, where she was born in 1951.[1] At the age of twenty she married George Studholme Hodgson and that same year the couple migrated to Melbourne, Australia.[2] Studholme was reunited with his brother and the two began a short-lived business together before John moved to Sydney.[3] Caroline had formed a close friendship with Studholme’s sister-in-law Elizabeth Jane and the two maintained correspondence throughout the years that followed.[4] Less than a year after their migration, Studholme gained employment as a policeman in Victoria and was stationed out in Mansfield as a mounted constable.[5]

Caroline did not follow her husband and instead remained in the city running a boarding house, under the 1870 Married Woman’s Property Act, she could legally own property separately from her husband.[6] Prior to entering the sex-work industry, Caroline was a member of the middle-class and was well aware of the stigma surrounding prostitution but the lucrative nature of the trade clearly persuaded her.[7] An early photograph (shown above) shows her in a simple dress, resting on the ledge of a balcony with a look of innocence about her. She looks quite young and exudes femininity with her tight locks gathered into a bow and a choker made of velvet adorning her neck.[8]

Caroline was just over the age of twenty one when she launched her first brothel in 1873, in the following decade she purchased the two adjacent properties and all three were located on Lonsdale Street, within Melbourne’s thriving sex work district known as Little Lon.[9] She also owned a home in St Kilda and two cottages in Middle Park.[10] During her separation from Studholme, there were rumours Caroline was involved in a relationship with composer Alfred Plumpton but nothing was ever proved.[11] She had no biological children, her only daughter Irene Hodgson was adopted but rumoured to have been fathered by Plumpton.[12] If that were to be true her adopted status may have been fabricated as a means of protection from scrutiny and shame but it is also possible that Irene may have been the child of a prostitute working for her mother.[13] Caroline kept her daughter far away from the district of Little Lon, Irene lived at her mother’s property on York St, St Kilda.[14]

Studholme and Caroline reunited in 182 when he was diagnosed with tuberculosis and she put him up in one of her properties, giving him a peaceful escape in which to spend his final years.[15] Perhaps it was due to his wife’s generosity that Studholme made amendments to his will just two months before he passed, revoking a request for £1000 to be given to Agnes Chatsworthy, his carer, and assigned the sum to Caroline instead.[16] Upon Studholme’s death on February 7 1893 Caroline Hodgson received a total of £1907 in currency, valuables and shares.[17] Two years later, she married again but the union was short-lived and she divorced Jacob Pohl after 11 years.[18]

By 1874 Caroline Hodgson was going by her sobriquet ‘Madame Brussels’, perhaps it was inspired by the city she and Studholme visited on their honeymoon, a reminder of a future interrupted by her migration to Melbourne.[19]

[1] Margaret Anderson, “Madame Brussels,” Old Treasury Building Heritage Icon and Museum, accessed September 2022, https://www.oldtreasurybuilding.org.au/madame-brussels/

[2] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

[3] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

[4] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

[5] Leanne Majorie Robinson, Madame Brussels: This Moral Pandemonium (Australia: Arcade Publications, 2009), 19.

[6] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”; Barbara Minchinton, "Women as landowners in Victoria: questions from Little Lon," History Australia 14, no. 1 (2017): 70, https://doi.org/10.1080/14490854.2017.1286704

[7] Robinson, Madame Brussels: This Moral Pandemonium, 22.

[8] Karl Quinn, "First photo of Madame Brussels, the red light queen of 1880s Melbourne," The Age, August 3, 2019, https://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/books/first-photo-of-madame-brussels-the-red-light-queen-of-1880s-melbourne-20190830-p52mjw.html.

[9] Barbara Minchinton, The Women of Little Lon, (Melbourne: Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd, 2021), The persecution of Madame Brussels, https://www.perlego.com/book/2140269/the-women-of-little-lon-pdf.

[10] Robinson, Madame Brussels: This Moral Pandemonium, 16.

[11] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

[12] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

[13] Robinson, Madame Brussels: This Moral Pandemonium, 48.

[14] Robinson, Madame Brussels: This Moral Pandemonium, 48.

[15] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

[16] Robinson, Madame Brussels: This Moral Pandemonium, 84.

[17] Robinson, Madame Brussels: This Moral Pandemonium, 84.

[18] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

[19] Philip Bentley, “Hodgson, Caroline (1851–1908),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, accessed September 2022, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hodgson-caroline-12986; Kate Follington, "Podcast episode 3: They called her Madame B. Uncovering Melbourne's infamous madame," Public Record of Victoria, accessed September 2022, https://prov.vic.gov.au/podcast-episode-3-they-called-her-madame-b.

Image: Quinn, "First photo of Madame Brussels, the red light queen of 1880s Melbourne."

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

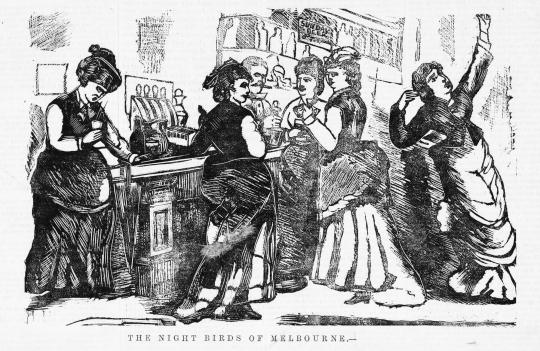

PROSTITUTION IN NINETEENTH CENTURY COLONIAL VICTORIA

In Victoria, prostitution was not illegal in the nineteenth century but while it was not encouraged it was tolerated as a necessity.[1] Those who called for legislative reform against the trade deemed it ‘The Social Evil’.[2] The colonial government took a regulative approach; establishing that prostitution could not be eradicated and thus had to be controlled in order to protect public health, safety and order.[3]

In the late nineteenth century the colony of Victoria was a people eager to discard its convict past and establish itself as society built on freedom and hard labour.[4] The famous little Lon district was located in the north-east of Melbourne where police relegated the city’s prostitutes.[5] Although this was completely legal, vagrancy laws could see prostitutes arrested if they were deemed ‘disorderly’, meaning they were drunk or stole from their clients, and brothel-keepers could face arrest for a ‘disorderly house’ if their employees and patrons behaved in the same manner.[6]

A unique characteristic of prostitution in this precise point in Victoria’s history is the almost complete absence of male brothel owners and/or pimps.[7] Women who participated in this trade often did so out of necessity due to the insufficiently low wages of factory and domestic work.[8] It was not uncommon for women to resort to prostitution if they became widows or were deserted by their husband and left to financially support themselves and/or their children.[9] Although it was acknowledged that many began sex work due to financial difficulties, prostitutes were believed to possess ‘an inherent propensity to vice’.[10]

Around the time Madame Brussels entered the scene, parliamentarian Thomas Bent claimed there were 2500 ‘abandoned females’ in Melbourne and its neighbouring suburbs and most were of European descent.[11] Amongst these a hierarchy of sorts existed, at the bottom were the common prostitutes who worked the city’s taverns, wharfs and streets, and at the top, the women of the flash houses; elite brothels which attracted a wealthy clientele and provided a considerably better working environment.[12]

Nevertheless, all prostitution held enormous risks; sexually transmitted diseases like gonorrhoea and syphilis were common, unreliable and harmful contraceptive methods often couldn’t prevent unwanted pregnancies and women faced the threat of violence from clients and each other.[13] Even brothel keepers faced such dangers, like Annie Wilson who was ‘dealt blows on the mouth and chin’ by a drunken William Slavin after refusing him entry.[14]

The gold rush of 1851 saw an influx of diggers into the city of Melbourne and a large part of their earnings fed the female-dominated industry of prostitution.[15] Its uniquely gendered economy presented tremendous opportunities for women like Caroline Hodgson, enabling them to gain financial autonomy through the ownership and management of brothels.[16] Melbourne’s economy was undoubtably impacted by prostitution.[17] Women who worked both independently and in brothels required dresses and accessories, flash houses needed furniture, food and the social balm of alcohol thus a variety of businesses; pawnshops, butchers, greengrocers, jewellers, furniture traders, depended on the industry.[18] Prostitutes operated in a variety of establishments, from small laneway cottages to grand buildings on the main streets and thus placed a diverse range of demand on the Melbourne market.[19]

[1] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

[2] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

[3] Kay Daniels, So Much Hard Work: Women and Prostitution in Australian History (Sydney: Fontana/Collins, 1984), 164.

[4] Raelene Frances, "Sex Workers or Citizens? Prostitution and the Shaping of “Settler” Society in Australia," International Review of Social History 44 (1999): 103, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020859000115214.

[5] Chris McConville, "The location of Melbourne's prostitutes, 1870–1920," Australian Historical Studies 19, no. 74 (1980): 96, https://doi.org/10.1080/10314618008595626

[6] Sarah Hayes, “Absinthe Bottle from Little Lon,” Old Treasury Building Heritage Icon and Museum, accessed September 2022, https://www.oldtreasurybuilding.org.au/absinthe-bottle-from-little-lon/

[7] Barbara Minchinton, “Female crews: sex workers in nineteenth-century Melbourne,” History Australia 17, No.2 (202): 354, https://doi.org/10.1080/14490854.2020.1756865.

[8] Barbara Minchinton and Sarah Hayes, “Brothels and Sex Workers: Variety, Complexity and Change in Nineteenth-Century Little Lon, Melbourne,” Australian Historical Studies 51, no.2 (2020): 168, https://doi.org/10.1080/1031461X.2020.1729825.

[9] Minchinton and Hayes, “Brothels and Sex Workers,” 168.

[10] David Blair, The Social Evil: Report by David Blair, 1873.

[11] “News of the Day,” The Age, October 25, 1877, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article206920956; Minchinton, “The Women,” under “The Lives of Sex Workers.”

[12] Robinson, Madame Brussels: This Moral Pandemonium, 24.

[13] Minchinton, “The Hazards of Sex Work,” under “The Lives of Sex Workers.”

[14] “A Lonsdale Street Fracas,” The Age, December 15, 1888. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article193402533.

[15] Minchinton, “The Legal Framework,” under “Why Sex Work Flourished.”

[16] Minchinton, “Introduction.”

[17] Minchinton, “Female crews: sex workers in nineteenth-century Melbourne,” 364.

[18] Minchinton, “Female crews: sex workers in nineteenth-century Melbourne,” 363.

[19] Minchinton and Hayes, “Brothels and Sex Workers,” 179.

Image: Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

1 note

·

View note

Photo

LITTLE LON

The inhabitants of Little Lon were described in 1915 by singer C.J. Dennis as ‘low, degraded broots’.[1] Spring, Little Lonsdale, Exhibition and Little Bourke Street formed the rough boundaries of this area where in the 1890s at least 17 brothels were known to police.[2] This part of Melbourne was also home to a predominantly poor working class population, whose often crowded living spaces and poor sanitary conditions meant the rest of Melbourne deemed the area a slum.[3] Newspapers avidly reported on Little Lon’s depraved inhabitants; the women who ‘barter away their womanhood’, ‘young ruffians’ whose ‘perfect terror’ littered the back alleys and the ongoing violence that saw a young girl ‘brutally kicked in the abdomen’ and another ‘stabbed in the neck with a butcher’s knife’.[4] Nevertheless, the prostitutes of Little Lon were a part of the community rather than simply outcasts as they were perceived in the wider social conscious of Melbourne.[5]

Caroline Hodgson lived and worked in Little Lon, owning and controlling 8 brothels during her thirty year long career.[6] In 1880, with the death of Sarah Fraser, the city’s foremost brothel madam, she inherited the throne, establishing herself as the Queen of Harlotry as she came to be known.[7] Her 32 Lonsdale Street brothel, Madame Brussels’, was the crown jewel of her collection.[8] The decadently furnished villa with its marble bathrooms and faux grass carpets created an oasis of pleasure.[9] A walled garden filled with statues of naked women created an idyllic sensual setting where clients could eat caviar and drink champagne with the madam’s many available girls.[10] Madame Brussels’ was in close proximity to the government offices and Parliament house; it catered to high profile figures and for this a separate and discrete back entrance on Gorman Alley ensured the privacy of clients.[11] The experience was far more curated than the simple transactional nature of procuring sex; men attended Hodgson’s establishments to feel transported, they sought the attention of flirtatious and pampering prostitutes, women who made them feel desired.[12] It is thought that Hodgson trained her girls to act and behave accordingly in the company of the elite classes.[13] She knew she needed to do more than simply meet the sexual demands of her clients in order to earn their loyalty; she had to ensure an experience unlike any other. The late nineteenth century was a period of immense cultural change and, having visited Europe at the time, Caroline certainly infused her brothel with a taste of the bawdy sexual nature of the dance houses and cafes she’d visited.[14]

Caroline had friends in high places too. Samuel Gillott, later Lord Mayor of Melbourne, was her mortgager and David Gaunson, the defence lawyer for bushranger, Ned Kelly, was her legal representative.[15] Perhaps her connections are what kept her in the game for so long. Or maybe it was her demure almost unassuming presence described in Truth, a newspaper later owned by one of her biggest opposers, journalist John Norton, as ‘a perfect little lady.’[16] Hodgson did not always reflect this almost infantilising image depicted of her, in 1887 she was fined 60 shillings for ‘disorderly and violent’ behaviour towards a Constable who had heard ‘very bad language and noise’ coming from one of her properties and had requested the inhabitants to quieten down.[17] Surprisingly, this appears to be an isolated incident and evidently Hodgson understood the importance of maintaining respectability.

One has to wonder whether, in all her years as a brothel-keeper, she ever had to resort to prostitution herself, particularly in the beginning of her career. Historian Barbara Minchinton believes a bent coin found in Hodgson’s silver purse may suggest she used it, as sex workers did, as a form of contraception by attaching it to her cervix using some kind of oil-based balm.[18] Like many facets of Madame Brussels’ identity this remains unexplained. Whether she ever worked as prostitute or not there is evidence that she was very well respected by the women she employed. Some worked for her for the entirety of her three-decade-long career and she did leave her houses under the care of her closest confidants whenever she was travelling.[19] One woman by the name of Martha Burrell worked for Caroline from potentially earlier than 1879 until the madam’s death 1908, and as a token of her gratitude Caroline left Martha her Middle Park two cottages.[20]

[1] Minchinton, “Introduction.”

[2] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

[3] Charlotte H. Smith, "Little Lon," Museums Victoria Collections, accessed September 2022, https://collections.museumsvictoria.com.au/articles/2867

[4] The Tocsin. “LUM LANDLORDS.” August 11, 1898. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197530580; The Herald. “Melbourne Ruffians.” May 8, 1876. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article244277711; The Bendigo Independent. “MELBOURNE.” December 17, 1891. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article169577698; Geelong Advertiser. “MELBOURNE.” January 28, 1885. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article148777906.

[5] Minchinton, “The Little Lon Community,” under “The Lives of Sex Workers.”

[6] Robinson, Madame Brussels: This Moral Pandemonium, 29.

[7] Minchinton and Hayes, “Brothels and Sex Workers,” 173.

[8] Robinson, Madame Brussels: This Moral Pandemonium, 29.

[9] Robinson, Madame Brussels: This Moral Pandemonium, 29.

[10] Robinson, Madame Brussels: This Moral Pandemonium, 29.

[11] Robinson, Madame Brussels: This Moral Pandemonium, 29; Follington, "Podcast episode 3: They called her Madame B. Uncovering Melbourne's infamous madame."

[12] Follington, "Podcast episode 3: They called her Madame B. Uncovering Melbourne's infamous madame."

[13] Follington, "Podcast episode 3: They called her Madame B. Uncovering Melbourne's infamous madame."

[14] Follington, "Podcast episode 3: They called her Madame B. Uncovering Melbourne's infamous madame."

[15] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

[16] Follington, "Podcast episode 3: They called her Madame B. Uncovering Melbourne's infamous madame."

[17] “POLICE NEWS,” The Age, August 9, 1887, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article190633965.

[18] Follington, "Podcast episode 3: They called her Madame B. Uncovering Melbourne's infamous madame."

[19] Follington, "Podcast episode 3: They called her Madame B. Uncovering Melbourne's infamous madame."

[20] Minchinton, “The Little Lon Community,” under “The Lives of Sex Workers.”

Image: Sarah Hayes and Barbara Minchinton, "Sex and the sisterhood: how prostitution worked for women in 19th-century Melbourne," The Conversation, February 14, 2018, https://theconversation.com/sex-and-the-sisterhood-how-prostitution-worked-for-women-in-19th-century-melbourne-89858.

0 notes

Photo

ERADICATING THE SOCIAL EVIL

Even before Caroline Hodgson made her home in Melbourne’s red-light district, journalist Marcus Clarke had written about the ‘dirty and draggle-tailed women’ who worked on street corners in Melbourne’s northeast.[1] According to Clarke, migration caused by the gold rush had ‘absorbed the floating criminal population’ of the rest of the city leaving Little Lon as one of the few remaining areas where ‘respectability is at a discount.’[2] The sex-ratio of the colony at this time may also explain why there was a sudden surge in concern regarding the moral risks of regulated and legalised prostitution).[3] Given the ratio of male to female had stabilised Victoria’s government may have felt more pressure from moral purity groups to increase policing powers and limit the visible presence of prostitution to better resemble a legitimate society rather than a city ruled by vice and void of order.[4]

During the last decades of the nineteenth century the Victorian government imposed legislation that restricted the rights of both brothel-keepers and the prostitutes themselves. Politicians were under immense pressure from religious and moral purity groups to better regulate sex work.[5] Men like physician John Singleton responded to the so-called ‘Social Evil’ by providing safe and communal housing for female migrants.[6] These lodge houses were located far from Little Lon so that women could less easily be ‘seduced from virtue’s path’.[7] The amended 1890 Police Offences Act, madams faced a ten-year sentence for procuring girls under the age of 13 meanwhile prostitutes between the ages of 13 and 16 could be imprisoned for two years.[8]

This triggered the beginning of an exodus; a considerable portion of Melbourne’s prostitutes began to leave the city and migrated instead to neighbouring suburbs with a lower police presence like Carlton and Fitzroy.[9] Raids on brothels became frequent at a time when the City Council had begun a mass demolition effort in the so-called slums of Melbourne.[10] Madame Brussels managed to avoid persecution for some time after the new Police Offences Act but her prestige and seemingly untouchable position as procurer of sex for some of the colony’s most important men earned her significant opposition.[11] Baptist Henry Varley was a preacher and campaigner of moral purity and one of Hodgson’s biggest opposers. At a gathering in 1889 he preached about Brussels’ ‘stronghold of hideous vice’ and stressed the need to criminalise the ‘traffic in the bodies and souls of young girls.’[12]

In 1906 Hodgson was, for the first time, found guilty of keeping a ‘disorderly house’ and later that year an expose published in Truth, revealed Samuel Gillott’s involvement in her business as mortgager.[13] The following year, the same judge oversaw the case which would end her career.[14]

In 1907, prostitution and its management was criminalised entirely but although Caroline Hodgson left the scene, sex work remained an important means of income for some women.[15]

[1] Minchinton, “The Crusade Against Vice,” under “The Destruction Of A Way of Life.”

[2] “Melbourne Streets at Midnight,” The Argus, February 28, 1868, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article5809960.

[3] Frances, "Sex Workers or Citizens?” 104.

[4] Frances, "Sex Workers or Citizens?” 104.

[5] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

[6] Graeme Davison, The Outcasts of Melbourne: Essays in Social History (United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2020), 9.

[7] Davison, The Outcasts of Melbourne, 9.

[8] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

[9] McConville, "The location of Melbourne's prostitutes, 1870–1920," 94.

[10] McConville, "The location of Melbourne's prostitutes, 1870–1920," 92.

[11] “The case of Madame Brussels,” Weekly Times, May 11, 1889.

[12] “The Crusade against Immorality,” Weekly Times, June 15, 1889, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article220415564.

[13] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

[14] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

[15] Minchinton, “The End of Little Lon,” under “The Destruction Of A Way of Life.”

Image: “The Crusade against Immorality.”

0 notes

Photo

A LEGACY

Caroline Hodgson always described herself as a boarding housekeeper.[1] When she was found guilty of owning a brothel in 1907 the judge gave her fourteen days to dispose of the house but by this time she was already quite ill.[2] Suffering from chronic pancreatitis and diabetes she passed one year later on July 11 1908.[3] As per her Will, she was buried in a polished oak coffin next to her first husband, Studholme Hodgson, at St Kilda General Cemetery.[4] She left behind an estate to the value of £4,828.[5] Out of her six properties the four not inherited by Martha Burrell went to Caroline’s two sisters Augusta Reifferscheid and Maria Baum.[6] Her laces, linens, jewellery and clothing went to her daughter along with a share of the profits from the estate sale.[7]

[1] Follington, "Podcast episode 3: They called her Madame B. Uncovering Melbourne's infamous madame."

[2] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

[3] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

[4] Robinson, Madame Brussels: This Moral Pandemonium, 113.

[5] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

[6] Robinson, Madame Brussels: This Moral Pandemonium, 113.

[7] Robinson, Madame Brussels: This Moral Pandemonium, 113.

Image: "108/351 Caroline Pohl: Grant of probate," Public Record Office Victoria, accessed September 2022, https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/D451F4BE-F1EB-11E9-AE98-F354BA74AE94?image=9.

0 notes

Photo

IMMORTALISING THE MADAME

Although many Melbournians may not recognise the name Caroline Hodgson, a fair few will certainly know her sobriquet. The name Madame Brussels nowadays reminds most people of the popular Bourke Street bar, with its pastel interiors and synthetic grass plots where patrons can sit back in their lounge chairs and sip one of the establishment’s many colourful cocktails. Those particularly familiar with Melbourne’s CBD may even know of Madame Brussels Lane. How many know of the story behind the name is unknown but given Caroline Hodgson was a woman participating in the sex industry it wouldn’t be too far of a stretch to assume many know nothing of her story or her contribution to Melbourne as the city it is today.

Of course, the rumours abound.

One of the most scandalous is that of the parliamentary mace which disappeared in 1891.[1] The story goes that it was used in ‘low travesties of parliamentary procedures’ by drunken parliamentarians at the famous Lonsdale Street brothel.[2]

Others spoke of a tunnel rumoured to have existed, connecting the State Parliament House with Madame Brussels’.[3]

The previous owners of the Madame Brussels bar were captivated by the brothel keeper’s story and decided to reincarnate her as Miss Pearls, Played by co-owner Paula Schole, she acts as a host of sorts, embodying the supposed ‘naughtiness’ of Hodgson’s brothels.[4] The bar staff all wore ‘little tennis outfits’ and the drink names all included sexual innuendos, like The Glory Hole or Love Juice.[5] Nowadays the new owners Tom Rattigan and Joshua Stevens have changed things up and although the interior doesn’t look very different the drinks menu is a little less on the nose.[6] The sexual references are subtle, like the Those Who Abstain menu or The Parliamentary Mace sangria, an ode to the infamous legend.[7]

[1] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

[2] Anderson, “Madame Brussels.”

[3] Follington, "Podcast episode 3: They called her Madame B. Uncovering Melbourne's infamous madame."

[4] Gillian, “Madame Brussels: Interview with the Fabulous Miss Pearls,” Melbourne Curious, accessed 2022, http://melbournecurious.blogspot.com/2010/08/madame-brussels-interview-with-fabulous.html#:~:text=She%20named%20herself%20Madame%20Brussels,Tea%20Party%20meets%20Wisteria%20Lane.

[5] Gillian, “Madame Brussels: Interview with the Fabulous Miss Pearls.”

[6] Chynna Santos, “Madame Brussels Saved From Permanent Closure by the Double Happiness and New Gold Mountain Owners,” Broadsheet, October 19, 2021, https://www.broadsheet.com.au/melbourne/food-and-drink/article/iconic-madame-brussels-being-reopened-owners-behind-double-happiness-and-new-gold-mountain.

[7] “Drinks Menu,” Madame Brussels, accessed September 2022, https://madamebrussels.com/s/MB-22-Drinks.pdf.

Image: “Madame Brussels,” Photo Gallery, accessed September 2022, https://madamebrussels.com/gallery

0 notes

Photo

FEMINIST OR ACCOMPLICE?

Can Caroline Hodgson be seen as a feminist icon? The historians who have studied her most closely seem to revere the woman as an entrepreneur and remarkable businesswoman.[1] One of the last photographs of Caroline reflect the kind of wealth she had accumulated as one of the richest ladies in Melbourne at the time.[2] She is dressed in the latest fashion with what is most likely a beautifully sewn silk dress.[3] She was a self-made woman who spent the majority of her life and career without a partner, doing what most women would never be able to achieve in their lifetimes.

So does her role as Melbourne’s most renowned brothel keeper make her an icon or is she complicit in the dehumanisation and violence that seems so inextricably linked to sex work? The criminalisation of prostitution in 1907 effectively ended what had been a female-dominated industry and exposed the trade to male pimps.[4] Historians Barbara Minchinton and z Sarah Hayes have studied Caroline Hodgson intimately and both strive to rewrite her story with a feminine sensibility. Hayes emphasises how the brothel owners and prostitutes of Little Lon were a community, a group of marginalised women striving to ‘raise themselves up out of this patriarchy’.[5] Both women are tired of the worn out narrative that slut-shames, dehumanises and diminishes the power, influence and contributions of sex work. Neither have labelled Hodgson a feminist. They do, however, recognise her efforts in protecting the health and safety of her employees, something that was put at great risk when prostitution was made illegal. Nevertheless, the moralism of the 1907 Police Offences Act still persists in Victoria over a hundred years later. Even with its decriminalisation in February 2022, sex work remains a taboo.

A cultural shift is needed before prostitution can be seen as a legitimate form of work. This involves dismantling internal biases that claim women capitalising on their sexuality is a sin and that a woman who does so is less deserving of the protection, safety and respect afforded to all other professions.

This is by no means an easy debate. The prostitute is both a tool of patriarchy and a form of its destruction. She is financially and sexually autonomous and yet her purpose is that of fulfilling the fantasies of men.

But Caroline Hodgson recognised this.

That is why the question of ‘Can she be seen as a feminist?’ cannot have a simple answer.

[1] Bentley, “Hodgson, Caroline (1851–1908).”

[2] Follington, "Podcast episode 3: They called her Madame B. Uncovering Melbourne's infamous madame."

[3] Follington, "Podcast episode 3: They called her Madame B. Uncovering Melbourne's infamous madame."

[4] Quinn, "First photo of Madame Brussels, the red light queen of 1880s Melbourne."

[5] Quinn, "First photo of Madame Brussels, the red light queen of 1880s Melbourne."

Image: Follington, "Podcast episode 3: They called her Madame B. Uncovering Melbourne's infamous madame."

0 notes