Thoughts on the post-Soviet, post-modern and the world by PhD student Kateryna Malaia

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The first fallen Lenin

This is my article on the first Lenin statue toppled in the Soviet Union published in the East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies:

https://www.ewjus.com/index.php/ewjus/article/view/374/pdf

0 notes

Photo

Today is the anniversary of the beginning of “Leninfall” in Ukraine. The first Lenin fell in Kyiv at the central street leading to Maidan. From there it continued in cities, towns and villages all over Ukraine.

© LB.UA

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Children and the head of the dismantled monument to tsar Nicholas II in Kharkiv, 1919.

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

This is a short walk through a new and an old neighborhood of Kyiv, Ukraine made by my friends and I a couple of years ago. The goal here is to show how getting an urban neighborhood to live, is a complex and organic process that needs a lot of thinking and analysis from a developer, a planner and an architect. Otherwise what one gets at the end are Potemkin Villages, or the town of the dead.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Homophobes

I originally wrote this text in Russian as a response to the Pride Parade that took place in Kyiv on June 12th, 2016 . Thanks to police and community efforts the parade was a huge success with no incidents. However, due to the Orlando tragedy it occurred to me that I should also post this text in English. [The text in Russian is below. ]

During the arguments with the opponents of the Pride Parade in Kyiv (or the Equality March as it was named), I came up with a categorization of these opponents.

The first kind, which is possibly the most wide spread, are those who are simply afraid of the Others. These characters mask their fear with hypocritical morals. These are the ones that in all discussions state that the LGBT community does not deserve equal rights because they do not reproduce, that children are born from the love between a man and a woman (love, ha ha!), and that it’s unpleasant for them to see, people marching for equal rights. These are the opponents who insist that one should not report to the world about ones’ sexual tastes, even though the Kyiv event was not about sex, but about equal rights. These characters are not going to come out to the streets and beat anybody up – their hypocritical discomfort is not strong enough for them to move their bodies off their couches. However, those are the same people who silently supported Hitler and resignedly underwent Stalin. These were also the people, many of whom inertly did not support the Euromaidan protests in Ukraine. Let us not forget about the banality of evil.

The second type is much more racy and dramatic. Their problem is specifically with open homosexuality. It seems that they are moved by inner demons on a scale that I would have a hard time imagining had I never read Dostoevsky. I think that for many of them their hatred towards the LGBT community is first of all based on their hatred towards a homosexual or other unconventional element of their own nature and the inability to embrace that part of themselves. These characters are so afraid of themselves that they are ready to kill others, in a symbolic attempt to get rid of their so-called sins. This second category has a very different vocabulary. The first hypocritical types constantly talk about aesthetics, evolution and children; the second type often slips into anatomical details of how they imagine homosexuality. It seems to be so Freudian that I feel uneasy telling them that they perfectly fit into a cliché—and even more so because in many places not as radicalized with conflicts and trauma, this cliché seems to be outdated. On the one hand, I am sympathetic of these troubled characters; on the other hand, they are not going to be sympathetic of me if I ever stand in their way. In any case, there could be talented public speakers among them, capable of moving crowds.

There are of course in-between types, religious zealots and others, who I have not observed and, hence, cannot describe. While this is not a complete portrait of all opponents of LGBT rights that exist out there, this should suffice for a brief experiential sketch.

За время споров с разными противниками Марша Равенства, я пришла к любопытному, на мой взгляд, выводу о видах этих противников.

Вид первый, самый очевидный, это противники, которые банально побаиваются тех, кто хоть чуточку от них отличается, и маскируют этот стрем ханжеской моралью. Это они во всех дискуссиях заявляют, что геи не заслуживают равных прав, потому что не размножаются; что дети рождаются от женско-мужской любви (любви, ха ха!) и что им неприятно видеть, вышедших на демонстрацию сторонников равных прав. Это они настаивают, что незачем демонстрировать свои сексуальные предпочтения миру, хотя речь вовсе не о сексе, а, еще раз, о равноправии. Такие граждане не выйдут никого бить – их ханжеский дискомфорт не достаточно велик, для того что бы пошевелить своей тушкой. Однако именно такие граждане молча поддержали Гитлера и безропотно перетерпели Сталина. Именно они не понимали, зачем нужно выходить на Майдан. Не стоит забывать о банальности зла.

Вторые намного колоритнее и драматичнее. У них проблема именно с открытой гомосексуальностью. Мне кажется, ими движут такие внутренние демоны, которых мне сложно было представить, не читай я, например, Достоевского. Я думаю, для многих из них ненависть по отношению к открытым гомосексуалистам и их сторонникам – это в первую очередь ненависть к гомосексуальному или какому-то схожему небанальному элементу собственной натуры и неспособность к его принятию. Человек так боится самого себя, что готов убивать других, в символической попытке избавления от собственного так называемого греха. У них несколько другой лексикон – первый, ханжеский типаж, все время говорит об эстетике, эволюции и детях; второй тип часто съезжает в анатомические подробности того, как они представляют себе гомосексуальность. На мой взгляд, это настолько по Фрейду, что как-то даже неудобно указывать людям на их попадание в клише. Тем более во многих более расслабленных обществах, не радикализированных войной и травмой последних лет, эти клише уже не совсем актуальны. С одной стороны я сочувствую таким мечущимся натурам; с другой - они не посочувствуют мне, если я встану у них на пути. В любом случае, настоящих буйных мало, но среди них могут встречаться ораторы, способные взбудоражить толпу.

Есть конечно же и промежуточные типы, и религиозные фанатики и те кого я не пронаблюдала и поэтому не могу описать. Но для поверхностного социального портрета этого достаточно.

0 notes

Photo

A Hole to Russian Constructivism

I took this picture of the great Constructivist masterpiece by Konstantin Melnikov in Moscow in 2013, when the property and preservation arguments around it were as heated as possible. As you can see in the picture, the signature cylinder part of the building was accessible to the general public through a hole in the fence.

http://www.archdaily.com/151567/ad-classics-melnikov-house-konstantin-melnikov

#post-soviet#konstantin melnikov#moscow#hole in the wall#historic preservation#russian constructivism

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Voices From Chernobyl

Besides the famous War Does Not Have a Woman's Face Svetlana Alexievich, the Noble Prize laureate 2015, wrote another deeply unsettling polyphonic masterpiece called Voices From Chernobyl. Today is the 30th anniversary of the catastrophe and if anybody asked me to recommend a reading on Chernobyl, Voices From Chernobyl would be my first choice.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voices_from_Chernobyl

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/08/books/voices-from-chernobyl-an-excerpt.html?_r=0

0 notes

Photo

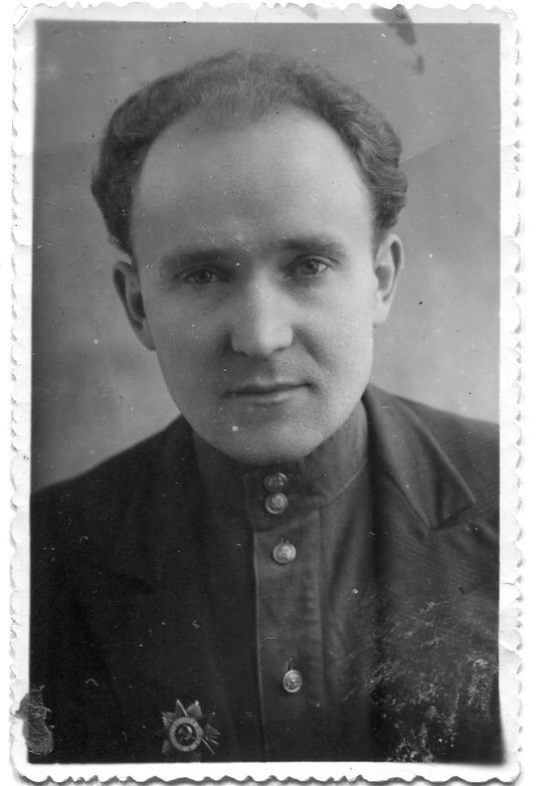

Grandfather

My grandfather was born in one of the countless Ukrainian villages named Marianovka in 1918. In 1917 Ukraine became an independent state. In 1921, as the result of Bolshevik expansion Ukraine once again became a colony. Metaphorically and statistically speaking, being born in the 20th century Ukraine and outside of some form of Russian occupation was relatively improbable. Even I, a self-identified post-Soviet citizen, was born in the Soviet Union. Grandpa, being born into a momentarily independent Ukraine, was a bit of a rarity.

Story has it that his father was dark haired and curly like a Roma. There were seven children in the family. I do not know how they lived before the 1930s because my grandpa never told me. Either we were never close enough, or maybe he just does not like to talk about his childhood. I guess my mom does not know either, which makes me think the second guess is correct. In any case, during the 1932-1933 artificial famine created by Russian Bolsheviks to break down the “individualism” of Ukrainian peasantry, they all—his siblings, his parents, and pretty much the entire village with a typical Ukrainian name—died of starvation. For years, he told us that, because he was the older son, they gave him all the food that was left (mainly garlic) and sent him on the road to the large and beautiful port city of Odessa, where they had distant relatives. Not that long ago he told my father that he actually witnessed all of them die before he left. We are not sure about how he made it to the city, because peasants at that time were refused IDs and travelers’ IDs were constantly checked. This is how the Soviet authorities prevented their less favored peasant class from running away from their famine-struck villages.

Long story short, he made it to Odessa and found a job at the candy factory, which is how he survived the hungriest years. He seems to have loved Odessa dearly. He bought candy from Odessa Karl Marx Candy Factory for all of our family gatherings—when family gatherings were still a thing.[1] Around a year ago he told me about his youthful days before World War II spent walking Odessa boulevards and meeting beautiful local girls. I could very clearly imagine the picture of an early summer evening at the boulevards, sinking in summer greenery, with men and women wearing white linen in the fashion of the 1930s. The image in my head, or rather the warm light, distantly reminds of Georges Seurat’s painting Sunday on La Grande Jatte. Once in a while grandpa uses Odessa Yiddish-style phrases, some of which we do not understand, but have become so familiar with over the years that nobody questions it.

In 1941, he, together with the rest of the Soviet population, joined World War II. He was a tankman and at some point he was heavily injured. The doctors virtually had to put his stomach back together with a large portion of it missing. He said he was thirsty and asked for water and someone gave him pure spirit to drink and he thinks it disinfected his bowels and that is how he survived. For recovery he was sent to a hospital in Kyiv where he stayed and met my grandmother. I always wondered if they were ever in love or if she was just a good choice—with her own communal apartment room, bought with money from selling silk she brought after being a nurse in the Korean War. Now that I think about them, it might be that both of them became orphans around the same age; they were both war survivors and were not much into recalling the past. There might have been some deep understanding between them that we actually never saw.

He always wanted to be a sculptor but he only spent a couple years at school so he was never admitted to the Kyiv Art Institute. Instead, he became a molder. At first they lived in a barrack where my grandma had a room. Then, after my aunt was born, they moved to a room in a newly built apartment in the very center of Kyiv because my grandpa did façade work for the construction. My mother was born there, in a new Stalin-style apartment building, turned communal because of the housing shortage. The location was so central and fashionable that she went to school together with the children of university professors, acknowledged writers and bureaucrats. She, the daughter of a molder and a grocery shop assistant. Both of my grandpa’s children went to the Art Institute: the older one for Sculpture, the younger one (my mother) for Architecture, where she met my father.

He worked with a lot of famous sculptors throughout his practice. Some of them were Union-scale maestros, working on things like humongous monuments to the Mother Motherland—the stereotypical image of Kyiv. They all used to drink, of course. How else do you deal with the kind of Motherland they had? But my grandpa was never an alcoholic, he just drank with them once in a while and on one of those nights he broke his hipbone on a slippery winter street. He was 79 at the time. The doctor first said that many young people do not fully recover from that kind of accident and in my grandpa’s case we should have expected the worst. Despite this gloomy forecast grandpa recovered and soon started walking to his studio with a cane. It’s been so many years since his accident that even I start feeling old when I think about it.

He broke his leg again the winter before the last one; as you can probably guess it did not stop him. A couple years ago, before Crimea was occupied by Russians, he went there to see the sea. We are not very close, perhaps because of other family member’s squabbles, or perhaps because of the generational difference. However, I think about him often, which he probably does not realize. I look in the mirror and I think: what have all of you people dead or alive given me? What is it in my face or in my voice, or in my physique that reflects their presence on Earth? And what is it that I have to do to somehow fulfill the mission of being, that they have stubbornly continued, and I have such a hard time grasping? My grandpa is alive and well in Kyiv, Ukraine. He still walks to his studio every other day and works on sculpture molds. Yesterday he turned 98.

[1] Yes, Karl Marx Candy Factory. Socialism produced a lot of funny connotations, and it takes moving out of its context to realize all the absurdity.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Chantal Akerman’s From the East (D’Est) is an absolute must see for anybody interested in or studying the post-Soviet condition

0 notes

Text

Housing Shortage, Repressions and the Mechanisms of State Survival

How would you feel if you had to live in one room with your grandma, mother, father and two siblings and share the bathroom and the kitchen with at least a dozen more people with no perspective for you to ever move elsewhere, because new housing is not being built? This was a typical kommunalka (rus: communal apartment) lifestyle on the eve of World War II.[1] The only way out is if you could take your neighbor’s room and at least have twice more space for your big family; but the neighbor is in need of a place to live too and lives in similar crowded conditions. What do you do in this complex situation? How do you not lose hope or rebel against the system that put you in this position?

In the late 1930s’ Soviet Union they knew the answer: you report your neighbor to KGB and move into the extra room, as soon as the neighbor’s family mysteriously disappears. As Sergei Dovlatov wrote in his Pushkin Hills (1983): “We constantly criticize comrade Stalin, and of course not without a point. And still I want to ask - who do you think wrote 4 million reports?”

However, what I just told you is a known fact. For decades it has not been a secret that people reported each other to get housing. Sometimes the cycle repeated again and those who just moved into a new room soon had to involuntarily move to the labor camps following their former neighbors. However tragic those stories are on the individual level let us for a second abstract from personal horrors and shift up the scale to the level of the state and those in power, or precisely the only almighty man – Stalin. There is no way that he and his officials did not know about the tendency to report neighbors for housing. There is also no way that the Soviet elite was unaware of the critical housing shortage situation that might have – exploded, like the transport crisis in Moscow did in 1931 if some kind of measures were not taken.

Now let us ahistorically dream for a second: what if the Soviet elites, perfectly aware of the housing crisis, used housing related reports and arrests to let the steam out of the teapot? In other words, what if they intentionally created a wicked illusion of the possibility to improve one’s housing situation even if this required indirectly killing your neighbor with the help of the security service? There may indeed be a chance that a housing lift through arrests was the state housing strategy in the 1930s, even if nobody ever said it out loud.

[1] Kommunalkas emerged after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, when the government decided to break upper and middle class urban apartments down into multifamily dwellings with shared amenities. In kommunalkas families of completely different backgrounds and position came together to lead a seemingly communal lifestyle and create shared households. Even the former bourgeois private owners were sometimes living together with working class families placed into their former rooms. This atmosphere did not facilitate harmony at the already overcrowded (no more than 8sq. m. per person) kommunalkas. In the first decades of the Soviet rule kommunalkas turned from an envisioned transitional step to better housing, into a stable residential nightmare for the absolute majority of Soviet mega cities’ population.

Citation: “Housing Shortage, Repressions and the Mechanisms of State Survival,” Kateryna Malaia, Post-Soviet Mind (March 19th, 2016), http://postsovietmind.tumblr.com/post/141350473874/housing-shortage-repressions-and-the-mechanisms

0 notes

Photo

Shade in Uzbekistan, 2012

0 notes

Text

How to Read Soviet Scholarly Writings Without Going Insane

Are you starting out as a scholar of Soviet History? Maybe you are a graduate student of Russian linguistics? Or an archaeologist interested in Central Asian cities, perhaps? Whatever the case, if you are reading this text, you have probably found yourself trying to make your way through dozens of pages of ideological constructions to be found in Soviet scholarly writings in any given field of science or humanities.

Sometimes right in the introduction, sometimes in the first chapter, and sometimes scattered all over the text the reader of Soviet scholarly books and articles will discover references to Lenin, Marx and Engels. A lot of times these references appear in the form of short, out-of-context citations, interpreted by the author of a study in a desperate attempt to relate the citation to the rest of the text. These ideological, or if you wish propagandistic, constructions are in most cases rather similar and irrelevant to the umbrella question of the study. When these ideological scribbles appear in the beginning of the text it often confuses the reader and discourages him or her from further reading. So, why on earth did Soviet scholars en masse add these seemingly unnecessary and cumbrous chunks of text to their research?

Why did Soviet scholars have to put propaganda into their texts?

In the Soviet Union, Marxism-Leninism was considered to be the only true framework for scholarly thinking; scientific or humanitarian research that happened outside of Marxist-Leninist Dialectic Materialism was automatically considered as being false (and malignant). Therefore, the relationship of a study to Marxist-Leninism automatically made it that much more publishable, than if no such relationship had been found. The Soviet scholars, especially the ones outside of the fields of political science, did not necessarily want to put Marxist-Leninist propaganda into their studies. Soviet scholars might have publicly claimed that Marxist-Leninist philosophy had greatly facilitated their research, because they lived in a totalitarian country where they had to please the carnivorous system.[1]

In the Soviet Union, in which every scientific discovery had to be within the framework of a rather bureaucracy-contaminated version of Soviet Dialectic Materialism, the validity of a scholarly and especially humanitarian work was often estimated according to its ideological correctness. Unfortunately for us, a Soviet book on Central Asian archeology had to begin with praise to the “classics” of Marxist-Leninist thought, who “considered preservation and study of the cultural heritage of the past to be of great importance.”[2] What a surprise in the mid-1980s, right? Fortunately for us, this and many other books on Central Asian archeology were published; despite the propaganda, these books still delivered extremely valuable knowledge about the findings, and in the best cases the interpretations, of the Soviet archeologists.

Why did Soviet scholars always use the same citations, even if the rest of the text virtually contradicts those citations and their ideological interpretations?

This happened partially because even Lenin’s, Marx’s and Engels’ writings are not limitless. Besides, over the years of the Soviet regime scholars generated substantial experience and gut feeling about censorship. Soviet authors did not often step beyond the limits of the unknown and preferred to use citations universally accepted by the censorship apparatus. If you ever had the pleasure to ever read Soviet scientific literature, I am sure you will remember the “erasure of differences between a city and a village” or “the most important art for us is cinema” (those who cite this famous phrase of Lenin’s often forget to include its second part: “because of the mass illiteracy of the population”). My freshest experience of encountering the “differences between a city and a village” occurred while reading a 1976 book on the perspectives of Soviet dwelling, dedicated mostly to urban high-rise apartment block housing. Some of the architectural designs were futuristic enough to compete with the Japanese Metabolist (and very futurist) movement during the same time. The question of the Soviet village, that by no means could have been described as futuristic, or even ready for the arrival of the imagined “radiant future,” was never raised in the book’s subsequent texts.

After the denunciation of Stalin’s personality cult in 1956 and the ban on the construction of monuments and naming places after the living party members, the pantheon of Soviet ‘saints’ quickly shrank to three unshakable figures: Marx, Engels and Lenin. All the former heroes in the propaganda texts of scientific research gave way to these three. Only these three were perfectly safe to cite in ideologically correct scholarly texts, and it seemed that the scholars did not really mind the simplicity of this unwritten social contract. Academia, by the way, was not the only realm where this trio took over the rest of propaganda figures. Around the same time, the territory of the Soviet Union became oversaturated with the canonic monuments to Lenin, as the state still had to reproduce propaganda, but there were no other spotless icons left erect.

Why do Soviet scholarly texts often read like descriptive catalogs rather than hypotheses or speculations? What is the point in all these writings?

Answering the second question first, the point is often in the fact of the publication’s existence. If you feel like the author made absolutely no attempt to interpret their subject and instead just catalogued some cases, do not hurry to condemn the author. It may appear that the topic that the author undertook for their research was already so marginal, from the perspective of Soviet censorship, that the author only had chances of publishing it, if there was no speculation involved.

Publishing something about the topic could have become an argument of its own. I often get this sense from Soviet art history studies, especially on the subjects of the Soviet Modernist and Sixtiers Art. The memory of the Soviet Modernist generation of artists and architects in the Soviet art criticism never fully recovered from Stalin’s purges and oblivion. While partially rehabilitated by the Sixtiers, Soviet Modernism still remained a slippery slope for an art historian willing to follow a sustainable career path. The Sixtiers movement completely fell out of grace at the end of the Thaw, as being too liberal and “foreign” for the Soviet regime. The 1970s and 1980s art historians may have used their chance to memorialize the art of the Sixtiers at least in the form of descriptive catalogues of these pieces, while interpreting this art within the larger 1960s context may have been simply impossible. Many of the 1920s-1930s and 1960s art works did not survive the 70 Soviet years and the early 1990s and the only form through which we know them today are those descriptive, seemingly non-argumentative scholarly articles.

What are the consequences of this scholarly ideology?

While I am not equipped to properly answer the question of scholarly propaganda’s consequences, in this short essay I would like to suggest that an interested reader look at Loren Graham’s book Science in Russia and the Soviet Union: A Short History or Vadim Birstein’s The Perversion of Knowledge: the True Story of Soviet Science. In addition, I’d like to note that for a Soviet and post-Soviet person like myself, Karl Marx became somewhat of a humorous figure. Here I am not trying to diminish the philosophical value of his work. However, I find it necessary to explain that if you have experienced a substantial amount of Soviet scientific literature, for example texts in which references to Marx are sometimes used to create fascinating stretches between his socio-economic theory and the agricultural selective seed breeding, you cannot take Karl Marx 100% seriously anymore.[3] While this short text did not intend to cover all the peculiar aspects of dealing with the Soviet science, I hope it helped the reader realize that they are not alone in their struggle to understand the essence of research in the Soviet scholarly literature.

[1] Todes, Daniel P.. 1994. Review of Science in Russia and the Soviet Union: A Short History. The American Historical Review 99 (5). [Oxford University Press, American Historical Association]: 1726–27.

[2]Muradov, V. G. 1984. Gradostroitelstvo Azerbaiidzhana XIII-XVI vv. Baku: "Elm"., 4

[3] Lysenko, Trofim. 1949. Agrobiologiia: Raboty po Voprosam Genetiki, Selektsii i Semenovodstva. Moskva: Gos. izd-vo selkhoz lit-ry.

Citation: “How to Read Soviet Scholarly Writings Without Going Insane,” Kateryna Malaia, Post-Soviet Mind (March 13th, 2016), http://postsovietmind.tumblr.com/post/141017681924/how-to-read-soviet-scholarly-writings-without

0 notes