peter boumgarden: consumption, digestion, & production

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Nudging in the Digital City

A few weeks back in the New York Times, the paper’s editorial board took a close look at Uber and their behavioral nudging to drive the company’s growth. They wrote:

To keep drivers on the road, the company has exploited some people’s tendency to set earnings goals — alerting them that they are ever so close to hitting a precious target when they try to log off. It has even concocted an algorithm similar to a Netflix feature that automatically loads the next program, which many experts believe encourages binge-watching. In Uber’s case, this means sending drivers their next fare opportunity before their current ride is even over.

While different in context, such “nudges” are at the core of Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler’s policy book of the same title. Nudging, reviewed here, refers to the process of changing behavior by modifying the following six elements around choice: iNcentives Understanding mappings, Defaults, Giving feedback, Expecting error, and Structuring complex choices

For example, if as a carmaker I expect error when you hop into your vehicle, I will design a car to beep when your seat belt is unbuckled. If I don’t think you will walk enough, I should have your fitbit provide feedback when you are below 10,000 steps. And if I know you are more likely to choose something from the front or tail end of the cafeteria line, I should make sure the options available there are more fruit and vegetable than sugary sweet.

But who gets to set such system defaults, and what drives their vision of the good? At the core, the critique from the Times editorial board is that behavior within the gig economy is driven by an invisible hand resting in Silicon Valley-- one more motivated by user engagement and profit margin growth that a coherent vision of a common good.

The other day, my friend Adam sent a few friends a fascinating interview with former Google Design Ethicist Tristan Harris. In a wide ranging conversation, Tristan introduces the idea of approaching the design of our digital world much like we would the design of a city. Like any major metropolis, the ecosystem of our phone is designed around a set of implicit and explicit end. In the case of an online ecosystem, Harris argues that we are organized around an economy of attention. Many of the technologies we interact with on our phones are organized to maximize user attention as measured by “time on site.” Just as Uber cares deeply about time that their drivers spend on the road, many tech companies use metrics like time on site because this can be monetized through advertising. Instead of getting you to pay for their service, these companies sell your engagement to advertisers for a fee. The more eyes, or more engaged these users are, the more advertisers will pay.

But by focusing on these metrics, other important measures might be missed. In other words, even if they are really good people, Instagram by design cares more about the amount of time I spend engaging with their app and less about the impact of that engagement on my psychology or social circles. You can’t manage what you don’t measure, as Peter Drucker reminds us. To put it another way, you end up caring deeply about that which you measure.

For Harris, the problem of these “digital cities” building around an attention economy is that their tactical notifications and buzzes in our pockets pull us away from how we might actually want to engage with these technologies. Like the addict in the casino, the lure of the slot machine is often stronger than the draw toward stepping into the light outside those casino walls. Harris questions the ethics of such a metric and worries of the impact it has on us. He argues that we need to find a way to build our alternative metrics like “time well spent.”

Harris’ vision of the city is an interesting analogy. Extending it generates different implications depending on your role within. In urban design, there are questions for the city planners, for the architects and builders, for the home buyer and for the home dweller. Applied to technology, there too are questions for the same groups, albeit defined differently. The city planners are those that setup the system or regulate the space. The home builders are the technology companies in charge of designing our apps. The home buyers are those of us who daily choose what app or system to opt into. And as home dwellers, we have to choose how to engage in individual choice once within a specific house system.

So, how should each of these players move from here?

Advice for the City Planner

As someone not involved in ecosystem design, my opinions are deeply uninformed. That said, from my limited vantage point I think some of Tristan’s suggestions are interesting. In particular, Harris argues that the system has to allow for segmentation by app type, with different metrics based on the goals of such tools. Using the analogy of the city, certain ‘neighborhoods’ of tools might benefit from metrics like “time on site,” but others should assessed by different goals.

In response to Adam’s, our mutual friend Dave highlighted a legitimate fear from this form of urban design. He wrote, the “thought of white liberals at Google, Apple and Facebook designing new interfaces which manipulate me into their determination of a proper worldview is also nauseating.” His point is spot on. Every choice has an implicit value distinction, and value systems can be skewed when existing in isolation. Unfortunately, Silicon Valley is one of the more isolated ecosystems around. Zuckerberg might envision community as a space where we are better connected to a larger number of distant ties, but maybe I want to move in the direction of deeper ties with a smaller network. If we go in the direction of different metrics by neighborhoods, the very least we can do is to make the value system transparent and let them users opt in or out if such choices are not a fit. By allowing people to transparently SEE what those choices are, and perhaps even choosing for themselves what constraints they want to be under, the system can become a bit more customized to individual needs.

Another element of ecosystem design is deciding what should and should not be social. In her 1961 classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities, urban planner Jane Jacobs suggests that, “there must be a clear demarcation between what is public space and what is private space. Public and private spaces cannot ooze into each other as they do typically in suburban settings or in projects.” So too at the level of city design, I worry that the push toward social gamification too quickly defaults to take something that might be a private activity (e.g. the enjoying of art and taking photos) and turns it into something social. The art of enjoying taking photos because an activity around crafting an image that can be liked by the largest amount of people. In this way, our ecosystems should identify types of neighborhoods that are best organized with social feedback, and those which are best set apart from the crowd.

Advice for the Home Builder

For the home builders in the cities-- the makers of the apps and tools-- there are a different set of questions. As Harris hits argues in the interview, by limiting engagement to a ‘like,’ ‘share,’ or ‘comment’ button, we inherently limit how a user can engage with shared material. Tristan goes back and argues for the benefit of something like a “let’s have a dinner conversation to discuss this” button to inherently expand how we can respond.

At a broader level, we need to think about the business models built around such apps. For many of these companies, the central route to monetization comes by generating eyes on screen and driving the attractiveness of the advertising play. But this does not have to be the only way. Tools like Duolingo have found ways to pair language learning with a monetization model built around translation for large companies needing page transcription.

So too we might think of an expanded set of business models found by pairing services with another side of a market whose interest is more in line with our own -- a kind of creative matching across problem sets. Imagine a health insurance company that is motivated by getting me to behave more healthy as a way to drive down their expense. Could some of this value be captured by the user engaging appropriately in their digital city? At the core of this business model design is a question of what behavior is being done by those ‘users’ and might this be paired with another market where this behavior creates value.

Advice for the Homebuyer and Home Dweller

Fortunately or unfortunately, at the end of the day we are left with much of the responsibility in deciding how to best live within our cities. Here again, Jacobs is instructive. She writes, “We expect too much of new buildings, and too little of ourselves.” We have to decide what values we want supported with our technologies, and then make sure this alignment is possible.

One of the ways we proceed is deciding what tools we want to use, where we want to abstain, and how we can best approach moderation. This is ultimately the choices of where we enter-- the choice of the homebuyer-- and how we engage -- the choice of the home dweller. Personally, I exited Facebook but stayed on Instagram (unfortunately still owned by Facebook… you win this time Zuckerberg). While not a perfect model, I found myself more drawn to the aesthetic and creative opportunity in this space than those in Facebook. I also like how companies like Duolingo find creative value-matching across users and spaces for company monetization. Furthermore, I am more likely to go with a technology I have to pay for (e.g. Overcast for podcasts, OmniFocus for task management) if I think paying for the technology will leave the creative control with the technology designers rather than those finding a way to sell my attention to the highest bidder.

With other tools, I know I have to engage with appropriate moderation-- Instagram being a prime example. I have been thinking hard about how to best design the home page of my phone to push me into a more effective and controllable environment. How do I self-nudge in the right way as I wait for the ‘city’ more broadly to be designed with my interests in mine? Just yesterday, I set up my phone so that Page 1 is filled with tools I am ok using regularly, and Page 2 are those things I don’t need as often or are am trying to move away from regular use (shown at the top of the page).

Finally, sometimes the best way to engage is by finding out when to walk away. As a few of us got to talking through Tristan’s podcast, I was inspired by Adam’s comment that he is forcing himself to leave his phone on a bookshelf when he comes home at night. Maybe this is his realization that, like me, he doesn’t do moderation well. In the moments when boredom arises and instant gratification is possible, I find myself unfortunately close to the slot machine junkie. But maybe I need to expect more of myself, channeling my inner Jane Jacobs. As long as these devices are in our pocket at every waking moment and next to our beds as we sleep, we might need to take more drastic steps to thrive in an attention economy.

0 notes

Text

Orthodox Pluralist or Benedict Option?

Writing in GQ a number of years back, John Jeremiah Sullivan penned one of my favorite essays on the Christian subculture. Set at the CrossOver Festival in the Lake of the Ozarks, Sullivan’s piece focused on idiosyncrasies in the Christian music scene. The essay is brilliantly constructed from wellhead to burner tip, but I want to focus on a specific part in the middle. This is where Sullivan provides his assessment of the music quality:

The fact that I didn't think I heard a single interesting bar of music from the forty or so acts I caught or overheard at Creation shouldn't be read as a knock on the acts themselves, much less as contempt for the underlying notion of Christians playing rock. These were not Christian bands, you see; these were Christianrock bands. The key to digging this scene lies in that one syllable distinction. Christian rock is a genre that exists to edify and make money off of evangelical Christians. It's message music for listeners who know the message cold, and, what's more, it operates under a perceived responsibility—one the artists embrace—to "reach people." As such, it rewards both obviousness and maximum palatability (the artists would say clarity), which in turn means parasitism. Remember those perfume dispensers they used to have in pharmacies—"If you like Drakkar Noir, you'll love Sexy Musk" Well, Christian rock works like that. Every successful crappy secular group has its Christian offbrand, and that's proper, because culturally speaking, it's supposed to serve as a standing for, not an alternative to or an improvement on, those very groups. In this it succeeds wonderfully. If you think it profoundly sucks, that's because your priorities are not its priorities;

Sullivan’s piece came to mind this last week as I read a number of writers at the New York Times engage with the argument of Rod Dreher’s newest book, The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation. At its core, Dreher’s thesis is that if Christians in the West see a deep and destructive misalignment of their worldview with contemporary culture (and they should!), they ought to explore forms of resistance and creative communities set apart from these forces.

Where Dreher sees potential, I fear Christianrock.

But let’s hear him out. What might these forms of community look like, and when does ‘resistance’ make sense? In an astute analysis of the book at Comment, philosopher Jamie Smith quotes the following from Benedict:

In a chapter on employment and work, Dreher takes the commitment to stability in the Benedictine Rule and turns it into a counsel of despair: "We may not (yet) be at the point where Christians are forbidden to buy and sell in general without state approval, but we are on the brink of entire areas of commercial and professional life being off-limits to believers whose consciences will not allow them to burn incense to the gods of our age." These professions, by the way, turn out to be "florists, bakers, and photographers" as well as public school teachers and university professors.

Like Jamie, though perhaps for different reasons, I can’t help but read Dreher and start to feel a bit uncomfortable. At the Times, David Brooks agrees and frames an alternative:

The right response to the moment is not the Benedict Option, it is Orthodox Pluralism. It is to surrender to some orthodoxy that will overthrow the superficial obsessions of the self and put one’s life in contact with a transcendent ideal. But it is also to reject the notion that that ideal can be easily translated into a pure, homogenized path. It is, on the contrary, to throw oneself more deeply into friendship with complexity, with different believers and atheists, liberals and conservatives, the dissimilar and unalike.

My own wrestling with the tension between a religious worldview and modern culture is deeply personal. I am the son of a midwestern Presbyterian pastor. Much of my youth was spent in the evangelical subculture -- shifting between forms of church and para-church ministry. For college, I went to a school with a conservative bent to theology, though one rooted in a deep belief in the intellectual power of the Christian tradition. Many of my professors believed that their reformed theology implied particular policies in the public square. It is a perspective that has exposed one of its graduates, Betsy Devos, to critique over the last few months. In graduate school at Washington University in St. Louis, my intellectual life continued to evolve. I grew in a desire to pull from my tradition while simultaneously setting it into dialogue with other ways of thinking and seeing the world-- frameworks from empirical social science, evolutionary psychology and biology, and cultural artifacts. And in the “friendship with complexity,” I found companionship.

The other day, my friend Robert sent me a dialogue between two famed philosophers: Richard Rorty and Nick Wolterstorff. Rorty is the late philosophical pragmatist from Stanford and Wolterstorff a retired reformed epistemologist who spent much of his career at Yale. Taking aim at Rorty’s view that religion is an unhelpful conversation stopper, Wolterstorff reframes an alternative model around the life of Martin Luther King Jr. In King, Wolterstorff finds a man whose viewpoints are deeply informed by faith, but he remains just as conversant across traditions as he is within. In other words, you can’t remove the Christian from King without losing the foundation of his argument; but, nor do you have to leave your alternative assumptions at the door to engage with its essence.

King’s vision is one that I find compelling.

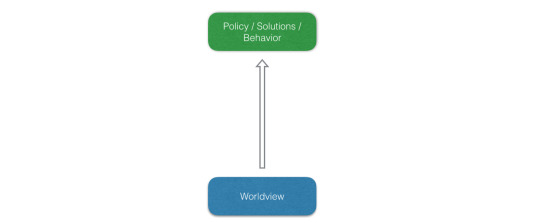

But to see the potential pitfalls of linking worldview to public response, it is helpful to take a step back. Put simply, everyone has a normative view of the world-- an intuitive sense of what is good, true, real, and beautiful. These views are a mix of our cognitive hard wiring towards specific moral responses, as can be seen in the work of Jon Haidt. They are also formed by the cultures we sit within. Some people’s views are shaped within a particular religious community, but perspectives can come from political frameworks like neoliberalism or philosophies like secular humanism. It could even be the “American Sublime” preferred by Rorty. In the end, the key point is that these views rest upon a set of metaphysical assumptions that are not easily amenable to rational argument. As Wolterstorff concludes in step with Rorty, “I view our human condition as such that we must expect the endurance of such fundamental disagreements.”

When it comes to the public square, these “private” views often hold implications for how a society should be ordered. They are endowed with certain value priorities which bear upon its citizens. They imply a set of policies to drive the world toward those ends. Where it becomes interesting is when these views-- whether foundation, or implication-- start to diverge. Two people look at the sexual revolution-- one sees an empowerment of women, another sees the undermining of important societal structures. So, where do these points of tension bubble up?

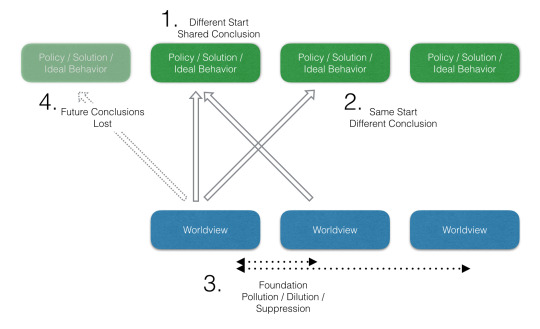

PROBLEM 1: DIFFERENT START- SHARED CONCLUSION: Let’s say I have a worldview that leads me to understand a specific kind of behavior as morally right. Maybe this is my view of the nuclear family, an understanding of how we should design prisons, or a perspective on privatization of schools and tax breaks for religious institutions. And then I meet you. You start from a very different beginning, but we end up with the same conclusion. While many might see this as a win, if my worldview is exclusivist, I might start to wonder whether I need to hold my starting perspective at all. Commence existential crisis.

PROBLEM 2: SAME START: DIFFERENT CONCLUSION: Another point of tension is when two people from a shared worldview reach drastically different views. You can see this in the fragmenting of religious institutions over issues of LGBTQ rights and gay marriage. You and I being in the same tradition, but end up concluding that very different behaviors are justified. Unlike the first problem where I wonder if my foundation is relevant, this crisis is about whether a particular tradition holds enough ambiguity to bear disparate conclusions.

PROBLEM 3: FOUNDATION POLLUTION / DILUTION / SUPPRESSION: The core of the third problem is how to maintain “orthodoxy” in the midst of pluralism-- to borrow from Brook’s language. In this case, I might worry that my worldview will be polluted, diluted, or suppressed by dancing amidst competing perspectives. Sure your view of relationships is shaped by specific sacred texts, but might there a little HBO mixed in there as well? Worries about “losing the culture war” seem to rest squarely within problem 3.

PROBLEM 4: FUTURE CONCLUSIONS LOST: Finally, to the extent that unique perspectives on future problems only emerge out of specific worldviews, the third worry is that in losing a distinct tradition we might negate creative responses to future issues. In other words, maybe we need a distinctly Christian, Muslim, Neoliberal, or Secular Humanist response to the singularity. Something might be lost if we don’t have these views weigh in on AI, the driverless car, and healthcare reform. If these views are polluted, then their response might be as well.

Looking over this landscape, there are a number of reasons why I stand more with Brooks than Dreher, aligned more fully with Wolterstorff than Rorty. On the first point, I don’t think a particular community has to hold the sole intellectual foundation for a specific policy for it to be justified. I am a pragmatist in this way. If we start on different paths but end up together, we should be able to celebrate. Specific to the second worry that our traditions will fragment into multiple conclusions, I think this inevitable divergence should give us pause about what we can know with certainty regarding metaphysics. This is not a move into nihilism, but rather a call to engage with big issues with loosened grips on our perspective and an openness to dialogue. And as for the third point, while I can see why we might fear the dilution of our traditions, I would rather aim for MLK cross-pollination than be set apart without an ability to dialogue.

Just the other week, Andrew Sullivan wrote an astute piece at New York Magazine assessing the reaction of Middlebury students to Charles Murray’s impending visit. As Sullivan’s work highlights, it is not only religions that struggle with this kind of open conversation. Speaking of growing intolerance within the academic “intersectionality” movement, Sullivan writes:

It is operating, in Orwell’s words, as a “smelly little orthodoxy,” and it manifests itself, it seems to me, almost as a religion. It posits a classic orthodoxy through which all of human experience is explained — and through which all speech must be filtered. Its version of original sin is the power of some identity groups over others. To overcome this sin, you need first to confess, i.e., “check your privilege,” and subsequently live your life and order your thoughts in a way that keeps this sin at bay. The sin goes so deep into your psyche, especially if you are white or male or straight, that a profound conversion is required.

...

It operates as a religion in one other critical dimension: If you happen to see the world in a different way, if you’re a liberal or libertarian or even, gasp, a conservative, if you believe that a university is a place where any idea, however loathsome, can be debated and refuted, you are not just wrong, you are immoral. If you think that arguments and ideas can have a life independent of “white supremacy,” you are complicit in evil. And you are not just complicit, your heresy is a direct threat to others, and therefore needs to be extinguished. You can’t reason with heresy. You have to ban it. It will contaminate others’ souls, and wound them irreparably.

So we are left with a dilemma. We need our unique perspectives, but we also benefit when they are in real dialogue with others. In contrast to Rorty’s view, I believe our traditions can give us unique insights into reality that might creatively color (versus color-over) what we are able to see. Like a language system whose particular words and grammatical structures enable us to pick up on the unique features of the world around us, so too worldviews enable us to see things that are missed with views that start with different aims. Here is Wolterstorff again, on this very point:

Yes indeed, religion is sometimes a menace to the freedoms of a liberal society. But the full story of how we won the freedoms we presently enjoy would give prominent place to the role of religion in the struggle; the good that religion does is not confined to providing, in Rorty's words, comfort "to those in need or in despair." Has the prominent role of religion in the American civil rights movements already been forgotten? Has its prominent role in the revolutions in South Africa, Poland, Romania, and East Germany already passed into amnesia? Then too, a full and fair narrative would have to give prominent attention to the great murderous secularisms of the twentieth century: Nazism, Communism, nationalism. The truth is that pretty much anything that human beings care deeply about can be a menace to freedom - including, ironically, caring deeply about freedom.

This is not to suggest that these views would not have come about otherwise. It is, however, to highlight that the starting points for these policies and perspectives came from particular worldviews. In this way, I think “intersectionality” should exist just as much as Judaism, Liberal Protestantism, Conservative Evangelicalism, and the American Sublime. But I will hold much stronger to that perspective is I think the views that come out of such starting points are both creative and open to dialogue. You can’t reason with heresy, Sullivan reminds us. Going back to Dreher, I wonder if in being set apart, the list of what counts as heretical grow longer and longer?

And still, I can’t shake my fear of the diminished quality from a world set apart. How close is the Benedict Option to John Jeremiah Sullivan’s experience at the CrossOver Festival? Here, Smith puts it well:

When Dreher encourages "bold" and "entrepreneurial" responses to these realities, the examples sound like a replay of subcultural production—little cottage industries that function as what James Davison Hunter has described as "parallel institutions"—coupled with the tribal admonishment to "buy Christian" (which is why in the United States you see little icthuses on business listings in the Yellow Pages—well, when we used to have Yellow Pages!). Dreher seems to think these are suggestions that are fresh and forward-looking, but a lot of us have already seen this movie. And we know how it ends.

Set apart to create a unique music footprint, an industry creates Christianrock. This should give us all pause.

Maybe in serving only the needs of a particular segment we end up with buttoned-up conclusions, a shift away from dialogue, and a resulting diminishment of quality. Christianrock does not need to be quality, Sullivan argues, in large part because that is not the primary thing the audience is looking for. They are looking for safe. They are looking for good enough. Sullivan concludes with the dagger: “So it's possible—and indeed seems likely—that Christian rock is a musical genre, the only one I can think of, that has excellence proofed itself.”

While we need unique communities and particular traditions to see the world with fresh eyes, we need to be equally concerned about the quality of their vision. We need to pay attention to patterns that make us excellent-proof. If the Benedict Option moves a specific tradition in the direction of a creative and helpful distinctiveness, then it should be celebrated. If it doesn’t, it runs the risk of preaching to a choir that is less and less engaged with any other comparative voice. In the end, I am less optimistic than Dreher that the positive vision will come to be. For that reason, keep me in the Orthodox Pluralist camp. Let me build “friendship with complexity,” and learn to deal with the risk.

0 notes