Where I pour all my ideas, poems, and stories. Do Enjoy! Also have a personal blog here: --

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

"Find someone who isn’t afraid to admit that they miss you, who knows you aren’t perfect but treats you as if you are, who’s biggest fear is losing you, who says ‘I love you’ and means it with all their heart, someone who believes leaving and giving up isn’t an option.” - Daily Quotes

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Hope is being able to see there is light despite all the darkness.” - Unknown

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Find someone who isn’t afraid to admit that they miss you, who knows you aren’t perfect but treats you as if you are, who’s biggest fear is losing you, who says ‘I love you’ and means it with all their heart, someone who believes leaving and giving up isn’t an option.” - Daily Quotes

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Other Place

I live in the droplets of the rain I exist along the horizon of irony I dwell within a cave of solitude But the bars say it is a prison I was born empty and unworthy Cursed to be full of wants Forever and out of reach

There is nothing here.

0 notes

Text

You know, when I see fictional characters who repress all their emotions, they're usually aloof and very blunt about keeping people at a distance, sometimes to an edgy degree—but what I don't see nearly enough are the emotionally repressed characters who are just…mellow.

Think about it. In real life, the person that's bottling up all their emotions is not the one that's brooding in the corner and snaps at you for trying to befriend them. More often than not, it's that friendly person in your circle who makes easy conversation with you, laughs with you, and listens and gives advice whenever you're upset. But you never see them upset, in fact they seem to have endless patience for you and everything around them—and so you call them their friend, you trust them. And only after months of telling them all your secrets do you realize…

…they've never actually told you anything about themselves.

167K notes

·

View notes

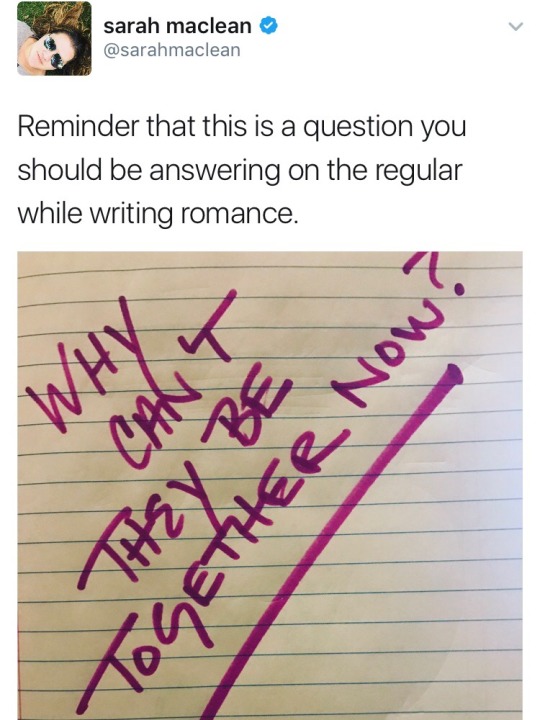

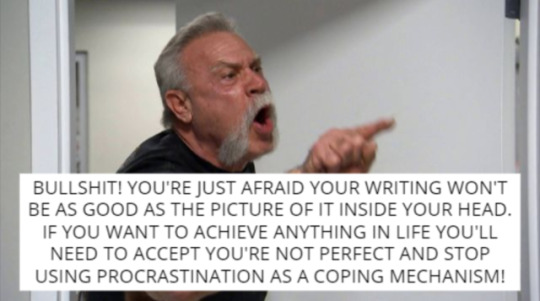

Photo

File this under “super obvious yet I always seem to forget it.”

121K notes

·

View notes

Text

A comma splice walks into a bar, it has a drink and then leaves.

A question mark walks into a bar?

Two quotation marks “Walk into” a bar.

A gerund and an infinitive walk into a bar, drinking to drink.

The bar was walked into by a passive voice.

Three intransitive verbs walk into a bar. They sit. They drink. They leave.

427K notes

·

View notes

Text

10 Cheats to "Tell" Well (Writing Tip)

Back in January, I did a whole post on when it is appropriate to “tell” something instead of “show” it. I talked about the difference between showing and telling, about how telling actually has in important role, and gave eight reasons you should use telling instead of showing. I touched on the fact that some telling is done better than others and also promised that in a future post I would give some pointers on how to tell well. Today is that future. If you need a refresher of my post on telling, don’t hesitate to give it a glance over. In it, I gave this example of how boring, monotonous, and ineffective telling can be:

They went to their friend’s house to see some cats. They liked them a lot. When they got tired, they called their mom to pick them up, but their mom couldn’t come for two hours. It was cold out, so they went inside and got something warm to eat. Then they drew some pictures before watching t.v.

Ack! Who wants to read a whole story like that? Not me! One of the problems with telling is that it can be too vague and it fails to immerse the reader in the story. But that is an example of truly awful telling. Here are some techniques to make your moments of telling shine by lessening or overcoming some of those cons. One approach is to use showing techniques when you tell.

Appeal to the Senses

Good showing appeals to the senses. Basically, we have to appeal to the senses to really show a story. There is no reason moments of telling can’t appeal to the senses in a similar way. Appealing to sight, sound, smell, taste, or touch can strengthen your telling the same way it strengthens your showing, it’s just that with telling, it’s usually brief, or done in a way that seems “in passing.” Look at this example, which appeals to sight, sound, and touch, to see what I mean. We drove through Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, Kentucky, stopping to cool the engine in towns where people moved with arthritic slowness and spoke in thick strangled tongues … At night we slept in boggy rooms where headlight beams crawled up and down the walls and mosquitoes sang in our ears, incessant as the tires whining on the highway outside. - This Boy’s Life by Tobias Wolff

Use Concrete Metaphors and Similes

Some telling doesn’t easily lend itself to the senses very easily, because of the subject matter that needs to be told. In cases like that, you can try tying in a concrete comparison to suggest a sense. Here is an example of my own. Since I’m dealing with an experience that is purely based on minds, I’m forced to do a lot of telling about it, but I try to make it more tangible by comparing it to physical experiences the reader can relate to: At night awake in bed, he’d remember her presence. How their minds had been connected, ethereal like spider webs. How just her being there brought a sense of comfort, like a childhood blanket he hadn’t realized he’d still had.

Sprinkle in Details

Just as you use detail to make your showing great, you can and often should include detail in your passages of telling. Mention a red leather jacket here or a specific cologne there. One way to combat the vagueness that telling often brings is to simply include more details. Again, not as much as you do in showing, but some. Detail makes the telling more realistic. Instead of just saying that your character’s friend was late to brunch, mention in passing that she was late because she got pulled over for an expired license plate. One key to making this work is to pick significant details, or at least details that aren’t cliche. Read about that here. Here is a bit of telling that I wrote: Their mom had stressed the importance of eating dinner as a family, of stir fry nights and cloth napkins on laps; of staying home to care for James, Scott, or Alaina when they were sick, with steaming honey-lemon drinks and movie marathons; and she had spent bedtimes chasing away nightmares with a flashlight in their closets, all for fourteen years, almost like she meant it.

Elevate Your Writing Style

You can make the telling in your story better by making it more literary. Elevate the prose with smart word choices and by paying attention to rhythm and sound. You can also bring in the similes and metaphors, or better yet, extended metaphors that tie together. Basically you are finding a way to make what you are telling particularly pleasing to the ear or mind. You are making it poetic. I hesitate to use the word “poetic” because what a lot of new writers think is poetic is actually purple prose. Take a creative writing poetry class and study some poetry. In “The Love Song,” by J. Alfred Prufrock, we get some great telling about fog. Here is just one stanza: The yellow fog that rubs its back upon the window-panes, The yellow smoke that rubs its muzzle on the window-panes, Licked its tongue into the corners of the evening, Lingered upon the pools that stand in drains, Let fall upon its back the soot that falls from chimneys, Slipped by the terrace, made a sudden leap, And seeing that it was a soft October night, Curled once about the house, and fell asleep.

But if you aren’t into poem examples, here is another example from the novel Crossed by Ally Condie: In the night, it feels like we’re running fast over the back of some kind of enormous animal, sprinting over its spines and through patches of tall, thin, gold grass that now glimmers like silver fur in the moonlight. The air is desert cold, a sharp, thin cold that tricks you into thinking you aren’t thirsty, because breathing is like drinking in ice.

(Again, see how good telling sounds a lot like showing?)

Bump up the Tone and Voice

But the literary avenue won’t work for everything. If you are writing a comedic passage or an angry one, the poetic approach may (but not always) clash with that for horrible effect. Instead, bump up the strength of the tone. Pull in the narrative voice or let the character’s voice bleed into the narrative at the deepest point of POV penetration. Channel the emotion of the narrator or character and write your telling in ways that reinforce that. To learn how to create, establish, and control tone, read my article that explains how to do just that. To learn about character voice, read my post on that. Here is an example from The Book Thief by Markus Zusak that gives us both a strong voice and good tone: Earlier, kids had been playing hopscotch there, on the street that looked like oil-stained pages. When I arrived, I could still hear the echoes. The feet tapping the road. The children-voices laughing, and the smiles like salt, but decaying fast. Then, bombs. This time everything was too late. The sirens. The cuckoo shrieks on the radio. All too late. Misfortune? Is that what glued them down like that? Of course not. Let’s not be stupid. It probably had more to do with the hurled bombs, thrown down by humans hiding in the clouds.

Keep reading

700 notes

·

View notes

Photo

//Absurdly helpful for people writing royal characters and/or characters who interact with royalty and members of the nobility.

[x]

355K notes

·

View notes

Text

Y’all I read a lot of scripts. And the one note I give over and over and over and over to the point that I can pretty much copy and paste it from one review to another…. let your characters lie. Let them omit, stumble, and circumvent. Allow them to be completely unable to express what they’re feeling. Make them unable to admit a truth. Let them sit in silence because they can’t think of anything clever to say! Let them say the exact wrong thing!

Dee Rees talks about it in her BAFTA lecture (which you should ABSOLUTELY WATCH): that what your character actually says should be three degrees of separation away from what they mean to say.

I read script after script after script where characters articulate their needs, desires, and objectives with perfect accuracy off the cuff 24/7 and there is not one single human person on this planet who is actually able to do that. This is the #1 thing that’s going to make your script sound stilted and the #1 thing that’s going to make shit difficult on your actors. Let them shut up, and let them lie.

37K notes

·

View notes

Text

Read to become a better writer

When I started as an editor-in-training, one of the first things our professor made us do, was to take one of the great European literary classics (mine was Kafka’s The Trial) and look at it as if it were an unknown debutant’s manuscript that lands on our desk. Would we publish it? Which parts would we keep and which elements would we change? It’s an excercise I still like to do as a writer: read a book to see what the author did and if I agree with it.

Here are three things I learned from reading books.

1 Planting clues

This is probably the first thing I ever realised about storytelling. When I was 11, I read a book in which the main characters go off on an adventure and are saved in the end by a friend’s dad, who conveniently turns out to be a policeman with a police radio to call for back-up.

What I learned: The ending of the book would have been less forced if the author had told us that the father was a policeman when he introduced him in chapter four, not at the end. Plant your clues earlier in the story to avoid a deus ex machina.

There’s a rule of thumb that you can’t convey new information needed for the climax after 80% of your story.

2 Who is the hero anyway?

This next book was a detective story with a depressed, alcoholic, unhappily divorced protagonist. In the end, it was not the depressed detective, but an innocent bystander who found the crucial last piece of information to solve the mystery. The detective just sat there and was depressed.

What I learned: The protagonist must be the catalyst of the story, not some C-character. The protagonist must be the one who saves the day/themselves/the victim/….

3 Just talk to each other!

a A budding couple pines for each other but nothing ever happens because he thinks he’s not good enough for her and she thinks he doesn’t love her anymore. I’m all for a well-written slow burn, but there’s a difference between slow burn and just plainly frustrating your readers.

b Character A was eavesdropping, didn’t hear everything character B said but still acts on the things they did hear. The whole storyline of the book could have been avoided if they would just talk to each other.

What I learned: Confusion and wrongful assumptions can make for an interesting plotline. Just make sure that your entire story couldn’t have been cut short if two people would just talk to each other.

If you don’t make them talk, give them a watertight reason why they can’t. For example: they couldn’t talk because they never were in the same space together.

Btw: I notice that this trope often does work for comedy.

***

Okay, that’s it for today, lesson’s over. Your homework for next week: when you read a book, see if you can learn anything. I may throw in a pop quiz next class. Kidding.

Follow me for more writing advice. New topics to write advice about are also always welcome.

Tag list below, a few people I like and admire and of course, you can be too. If you like to be added to or removed from the list, let me know.

Keep reading

4K notes

·

View notes

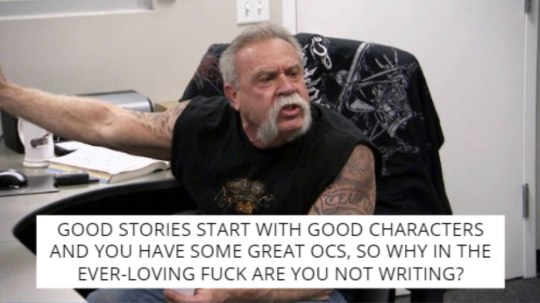

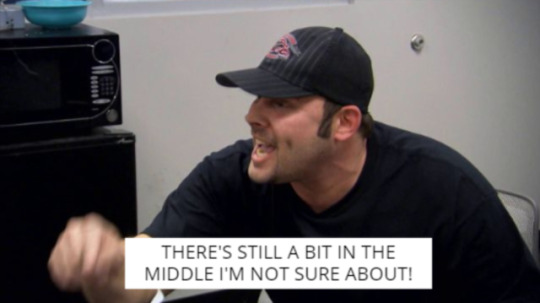

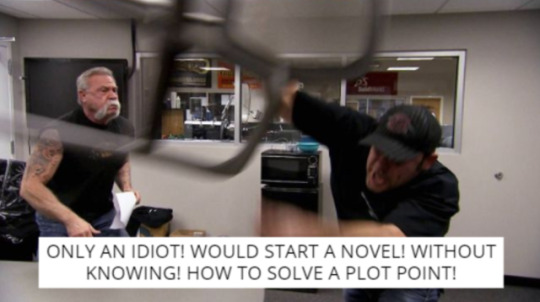

Photo

when you’re trying to write and your last two functioning brain cells start yelling at each other

223K notes

·

View notes

Text

“This is your daily, friendly reminder to use commas instead of periods during the dialogue of your story,” she said with a smile.

577K notes

·

View notes

Text

crucial muse development questions. send a number in my inbox to find out more about my character as a person ( because often, the most important things about character development have nothing to do with their shoe size or netflix queue ).

what would completely break your character?

what was the best thing in your character’s life?

what was the worst thing in your character’s life?

what seemingly insignificant memories stuck with your character?

does your character work so they can support their hobbies or use their hobbies as a way of filling up the time they aren’t working?

what is your character reluctant to tell people?

how does your character feel about sex?

how many friends does your character have?

how many friends does your character want?

what would your character make a scene in public about?

for what would your character give their life?

what are your character’s major flaws?

what does your character pretend or try to care about?

how does the image your character tries to project differ from the image they actually project?

what is your character afraid of?

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ambient sounds for writers

Find the right place to write your novel…

Nature

Arctic ocean

Blizzard in village

Blizzard in pine forest

Blizzard from cave

Blizzard in road

Beach

Cave

Ocean storm

Ocean rocks with rain

River campfire

Forest in the morning

Forest at night

Forest creek

Rainforest creek

Rain on roof window

Rain on tarp tent

Rain on metal roof

Rain on window

Rain on pool

Rain on car at night

Seaside storm

Swamp at night

Sandstorm

Thunderstorm

Underwater

Wasteland

Winter creek

Winter wind

Winter wind in forest

Howling wind

Places

Barn with rain

Coffee shop

Restaurant with costumers

Restaurant with few costumers

Factory

Highway

Garden

Garden with pond and waterfall

Fireplace in log living room

Office

Call center

Street market

Study room from victorian house with rain

Trailer with rain

Tent with rain

Jacuzzi with rain

Temple

Temple in afternoon

Server room

Fishing dock

Windmill

War

Fictional places

Chloe’s room (Life is Strange)

Blackwell dorm (Life is Strange)

Two Whales Diner (Life is Strange)

Star Wars apartment (Star Wars)

Star Wars penthouse (Star Wars)

Tatooine (Star Wars)

Coruscant with rain (Star Wars)

Yoda’s hut with rain ( Star Wars)

Luke’s home (Star Wars)

Death Star hangar (Star wars)

Blade Runner city (Blade Runner)

Askaban prison (Harry Potter)

Hogwarts library with rain (Harry Potter)

Ravenclaw tower (Harry Potter)

Hufflepuff common room (Harry Potter)

Slytherin common room (Harry Potter)

Gryffindor common room (Harry Potter)

Hagrid’s hut (Harry Potter)

Hobbit-hole house (The Hobbit)

Diamond City (Fallout 4)

Cloud City beach (Bioshock)

Founding Fathers Garden (Bioshock)

Things

Dishwasher

Washing machine

Fireplace

Transportation

Boat engine room

Cruising boat

Train ride

Train ride in the rain

Train station

Plane trip

Private jet cabin

Airplane cabin

Airport lobby

First class jet

Sailboat

Submarine

Historical

Fireplace in medieval tavern

Medieval town

Medieval docks

Medieval city

Pirate ship in tropical port

Ship on rough sea

Ship cabin

Ship sleeping quarter

Titanic first class dining room

Old west saloon

Sci-fi

Spaceship bedroom

Space station

Cyberpunk tearoom

Cyberpunk street with rain

Futuristic server room

Futuristic apartment with typing

Futuristic rooftop garden

Steampunk balcony rain

Post-apocalyptic

Harbor with rain

City with rain

City ruins turned swamp

Rusty sewers

Train station

Lighthouse

Horror

Haunted mansion

Haunted road to tavern

Halloween

Stormy night

Asylum

Creepy forest

Cornfield

World

New York

Paris

Paris bistro

Tokyo street

Chinese hotel lobby

Asian street at nightfall

Asian night market

Cantonese restaurant

Coffee shop in Japan

Coffee shop in Paris

Coffee shop in Korea

British library

Trips, rides and walkings

Trondheim - Bodø

Amsterdam - Brussels

Glasgow - Edinburgh

Oxford - Marylebone

Seoul - Busan

Gangneung - Yeongju

Hiroshima

Tokyo metro

Osaka - Kyoto

Osaka - Kobe

London

São Paulo

Seoul

Tokyo

Bangkok

Ho Chi Minh (Saigon)

Alps

New York

Hong Kong

Taipei

290K notes

·

View notes

Text

3 Redemptive Character Types

I love a great redemption story, but not every character who finds redemption is the same. So today I’ve outline three types of redemptive characters and what to watch for and consider when writing each.

Type 1: Characters Who Think They Are Worse Than They Are

If you are familiar with the story of

Les Mis

and you are like most people, you were probably thinking that stealing a loaf of bread to save your starving family is really not that bad of a sin. (And certainly having to spend 19 years in prison is waaaay too much, whether or not you tried to escape.)

Yet throughout the story, Jean Valjean consistently feels that he is falling short, even though most of his mistakes and sins are actually rather minor and understandable in comparison to his trials and accomplishments. Time and time again, Valjean sees himself as far worse of a human being than the audience does. In fact, he can’t bear Cosette, the one person in his life he can love and who loves him in return, finding out about his sins, and in his death scene, asks her not to read his letter about them until he has passed away.

Valjean is not a terrible person. He’s an amazing person! But nonetheless, his story of redemption is perhaps one of the most powerful and moving.

You can write redemptive characters the same way. However, like everything in writing, you need to be balanced. One of the easiest mistakes to make with this character type (or really, in any redemptive story) is to become too sentimental or melodramatic. If you go overboard about how wretched your character feels about herself, it can become annoying. If the gap between what the sin actually was vs. how awful she feels about it, is too big without an explanation, it can become more annoying. To be honest, there is a rather large gap between what Valjean commits vs. how awful he feels about it, but the gap is explained in how his society and other human beings (such as Javert) treat him for it–which further enables him to feel wretched.

A third problem can arise when you render the character’s emotion improperly or poorly, particularly by having it all illustrated through the character on the page instead of allowing the audience to feel it first. Unless you are in a denouement where you want to release and validate all that emotion, usually less is more.

Characters of this type tend to have a lot of inner turmoil and conflict, so getting the emotion right is key. (You can find all my tips on rendering emotion in my Writing Tip Index.)

Watch out for: Sentimentality, melodrama, repetitious emotions, too wide of a gap between the sin and the poor self-esteem (without an explanation), and poor rendering of emotion.

Consider: Inner turmoil/conflict and how it is portrayed, how others and society may view the character and how it compares or contrasts with how he views himself and also how that affects his relationships, how shame and guilt and the sin motivate his actions or dam his progression.

Other Examples: In the movie DragonHeart, Draco thinks less of himself and is harder on himself for having given half his heart to save a boy who grew to become an evil king–what was meant to be a noble act, even a holy act, ends up haunting Draco for the rest of his life. In Disney’s The Lion King, Simba blames himself (thanks to Scar) for his father’s death, which leads to him turning away from his place in society and even his true identity.

Type 2: Characters Who Give into a Moment of Weakness

Before the Reynolds affair even started, Hamilton discloses to the audience that he is in a state of weakness–exhausted, overworked, and lonely. Despite being popular with the ladies, he is not out and about looking to be promiscuous. He’s minding his own business, trying to save his job, when a woman seeks him out.

Essentially, the entire song “Say No to This” is about Hamilton literally praying to God that he can resist temptation, and out of weakness, giving in again and again and again, and being mad with himself about it, but … giving in again.

Like I talked about at FanX, I think this is a human experience we can all relate to (though ideally ours isn’t about an affair). We all have weaknesses, whether it’s a brownie, impulsive spending sprees, or even lust.

This type of character needs redemption because she actually did do something pretty bad. She might have gotten caught in the moment, experienced powerful temptation, given in to a weakness, or felt overwhelming desperation. Any of those particular things can be powerful motivators–leading people to do things they would not typically do.

I once had someone tell me that all human beings really have personal boundaries rather than personal standards. We may think we would never do X, but when we get pushed enough–from being stuck in shortsightedness, powerfully tempted, overworked, or desperate–and Y situation happens, we might.

One thing I love about this type of character, is that the experience is so human, and even if we may hate it … relateable.

And I think that is key to this type. Even if we completely disagree with what the character does, think they were stupid, or anything else negative, we have to understand it. We have to be able to relate to it on some level, or at least see how it could have happened. If not, it will be annoying, it will be a fail. I would say most of the time, the sin is not going to be something premeditated–exceptions to this are when pressures are ongoing and intense (ongoing exhaustion, ongoing temptation, ongoing desperation). The character will probably feel bad or, like Hamilton, angry with himself (“How could I do this?!”)

Watch out for: Situations and setups that aren’t relatable to the audience–or rather, are not rendered in human, relatable ways, are not properly explained. The sin should probably not be done flippantly; it’s done in a moment of weakness not laziness–there is a difference.

Consider: These powerful components–being caught up in the moment, experiencing personal weakness, powerful temptations, desperation, and ongoing trials and hardships and what that does to a person. Think in terms of boundaries rather than set standards. Explore how your character reacts and feels about what she has done, to capitalize on the human experience.

Other Examples: In Lord of the Rings, Boromir as well as a number of other characters experience moments of weakness when confronted with the Ring. These are great examples of individuals dealing with limits–the edge of their boundaries and capacities.

Type 3: Characters Who Discover Wickedness Never was Happiness

Another perhaps particularly powerful redemptive character is Severus Snape in the Harry Potter series. In fact, he was so redemptive that a lot of people seemed to forget what a total jerk he actually was. Snape dabbled in the dark arts when in school and actually even invented lethal spells. While he is a rather gray character, I think we can all agree he was once a “bad guy”–Death Eater and supporter of Voldemort, et al.

… until that journey became particularly personal in that Voldemort was going to kill the love of his life.

It may have been all about Lily, but ultimately Snape was true to the Order of the Phoenix, to Dumbledore, and to Harry.

In this type, the character is intentionally doing wrong. It may be that they are a villain or a “bad guy,” or it may be that while once goodhearted on page, they went down the wrong road, but whatever the case, they are committing sin left and right and purposefully. If we had the power to grant one person absolution, I think most of us would pick someone of the other two types before we considered this one. In fact, in the story, this type may not even seem like she is going to get a redemptive arc at all.

In some stories this character may be an anti-hero, in which case they will be handled a little differently than a bad guy or villain.

Unlike the other two types, we may not relate to this type as easily, at least not until later–likely when they begin the redemption process, or at least when we get a better understanding of why they are the way they are. Snape, for example, was easily hated by most people for most of the Harry Potter series. A slight exception to this is that in some cases, this type may do things that people privately wish they could do–wouldn’t life (seemingly) be easier if we didn’t care about doing wrong things? They may also have a cool factor because of it.

However, if they are a redemptive character, at some point they will realize, that in some ways, wickedness was never happiness. In some cases these types embody more of a theme or a lesson than a relatable emotional experience, like the prior two.

An important part of this character type is validation. The audience needs to see–have it validated to them–that this character truly does evil things. Then during, or after the redemption, the audiences needs it validated that they are truly a changed person.

The contrast between how wicked the character is and how much redemption she receives can create a very powerful storytelling effect. Often in highly powerful examples of this trope, the character sacrifices his life–either literally in death or figuratively in how he chooses to live out the rest of his life.

Watch out for: Glorification of wrongdoing in the overall story; failure to validate wickedness and redemption; flat redemption where the redemption isn’t “earned,” developed, or adequately explained.

Consider: What led the character to choose wickedness, what caused them to change, how that change will affect their circle of relationships and whether the change will be accepted by others (will they be tolerated or forgiven?). Also watch the breadth between their bad deeds and the extent of their redemption. What of their life is sacrificed?

Other Examples: In Star Wars Anakin Skywalker turns to the dark side but ultimately dies saving his son from Emperor Palpatine. In How the Grinch Stole Christmas, after trying to destroy Christmas, the Grinch learns to appreciate it, and his heart grows two sizes.

In the future, I may expound on these three types and talk about writing the story arcs.

298 notes

·

View notes