she/her | busy watching kdramas | f1 sideblog: sharl-leclair

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

me trying to sound employable: i love effort…. and doing things. i love trying. working is the best. i love it when its hard, and bad

210K notes

·

View notes

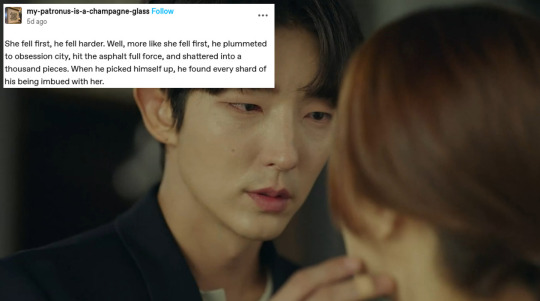

Photo

I love all three of you pricks.

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m guessing the job was pretty rough for her. And yet, she did her best to go along with Anya’s requests. You did a great job.

9K notes

·

View notes

Photo

LITTLE WOMEN 작은 아씨들 (2022) ⌊ ep.01 | dir. kim hee won ⌉

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Her Private Life 그녀의 사생활 (2019) Dir. Hong Jong Chan – Ep. 13

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

As Long As We Both Shall Live わたしの幸せな結婚 (2023) Dir. by Tsukahara Ayuko

612 notes

·

View notes

Text

vinny is an ipad baby but for like cups

50K notes

·

View notes

Text

film diary - ✰ 8/? howl's moving castle (2004) dir. hayao miyazaki

knowing you'd be there gave me the courage to show up. that woman terrifies me. i can't face her on my own. you saved me, sophie. i was in big trouble back there.

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

SUCCESSION ▸ The Old Guard™ immediately protecting gerri

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

I'll be right here.

When the Phone Rings (지금 거신 전화는) 2024

422 notes

·

View notes

Text

working full time is so stupid. There has to be more than this

489 notes

·

View notes

Text

You can only eat 2 foods for the next 2 years (with no health repercussions)

Spin this wheel twice to figure out what they are!

40K notes

·

View notes

Text

Why were we lying on the floor together last night?

When the Phone Rings (지금 거신 전화는) 2024

263 notes

·

View notes

Text

no way she discovered her cheating husband's pre-nup style pictures with the mistress... talk about a hard launch

0 notes

Text

dear lord I'm too young to be having back problems

2 notes

·

View notes