Largely a John Finnemore fanblog, with some Sayers on the side. (Two entirely compatible interests, in my opinion, especially given my Dog Collar Theory)(icon from JF's blog http://johnfinnemore.blogspot.com/2021/12/twenty-four-things-thing-nine.html)

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Who do I have to write to/call/pay off to get John Finnemore to write a Golden Age-style mystery novel

We know he loves the genre (he called it his "trashy fiction of choice" on his blog once and used to tweet every so often about John Dickson Carr), we know he's successfully written mysteries both comedic (Cabin Pressure: Paris) and puzzly (The Researcher's First Murder), we know he likes twisty turny plots but is also really good at conveying character through them even in short form...

Please, my dude, if Richard Osman can do it...

#john finnemore#cabin pressure#the researcher's first murder#golden age mystery fiction#he did reply to me on twitter once that the plot for jfsp s9 was originally an idea he was going to use for a novel#so it's not like he hasn't thought of it#and now he's written his jeeves and wooster pastiche story#which if it's the same one i heard at that tall tales also has puzzle components

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Which Cabin Pressure episodes do you play when you're breaking down and you need to turn off your brain and make yourself feel better?

I probably turn most frequently to (in order) Paris, St Petersburg, Limerick, Zurich, and Wokingham- though I haven't been able to listen to Wokingham recently because some of the themes about caring for aging relatives have been a smidge too close to the reasons why I need to be cheered up in the first place...

Honestly I think each episode provides something different- when I did an advent listen-through I identified St Petersburg as something I listen to when I'm feeling defeated and Limerick as something I listen to when I'm feeling lonely (about which more here) so I'm wondering- for the episode you picked, what itch does it scratch?

Please share in the comments- maybe we'll gain inspiration from each other for the next time we need a pick me up!

#cabin pressure#john finnemore#cabin pressure is genuinely a non-pharmaceutical antidepressant#nothing has helped me in the way that it has#and i'm grateful to have had the opportunity to tell jf that last fall in person#my sister tells me that from where she was standing he looked moved to hear it#i'm sure he hears it all the time though#i should note- some double acts and souvenir programme can fit the bill too#hot desk and penguin diplomacy are excellent mood lifters#as is jfsp s7e6#though i did once make the mistake of listening to red handed when in a bad mood without having ever heard it before#and i finished it feeling even worse

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love this! The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club is one of my favorite Wimsey books (and sometimes my actual, single favorite) and while the book itself is great, I also think it's Sayers's single greatest title.

Unpleasantness is just the perfect word- it's a negation rather than a positive statement. Things SHOULD be pleasant, but they aren't. The whole Bellona Club is like that- a club full of men that are brought together by the thing that damaged them, and the fact that the book is bookended by a man complaining about the club and his inability to find peace and comfort there is emblematic of that tension.

The classic image of a club where a henpecked family man goes to read the newspaper in peace or a bunch of Drones go to do stupid pranks or whatever- club as sanctuary, in other words- doesn't feel apt for the Bellona Club. For the adventurous type- the Robert Fentimans of the world- for whom war brought out the best, sitting in a stodgy club is the opposite of exciting. For the type whom war maimed and/or traumatized, the club is a place to be with other damaged people and be reminded of the cause of your damage.

The Bellona Club doesn't strike one as ever having been quite pleasant- the unpleasantness has been under the surface, as noted in the above post, since long before General Fentiman's body was found. The unpleasantness is there by design- the point is to take something as extremely unpleasant as war and try to cover it up with gentility. But you can't fully do that and so the Bellona Club will never be truly pleasant.

Now, of course, gentility can't fully cover it up, but it can do quite a lot. Wimsey knows that he's happier than George and Sheila Fentiman in no small part due to the money and support that he has- he has Bunter to prop him up and money for as much food as he likes of whatever quality he desires. He has leisure and intellectually stimulating work- and even he too is damaged! But George and Sheila are the unpleasantness bubbling up despite that, becoming visible, the carpet no longer being able to cover the stain. It's fitting that it's George who is the one whose digestion is wrecked- not only can't he digest, the whole effort to hide these things under the rug can't digest him, can't make him and the effects of what happened to him pleasant.

the repeating motif of digestion throughout unpleasantness at the bellona club is so fascinating. George Fentimen's suffering being not only in his mental illness symptoms but the gut problems he took home with him from the war. Opening the corpse's stomach to see when and what his last meal was. Peter's little speech at the dinner at the end about the mortifying ordeal of having to turn perfectly lovely picturesque food into disgraceful sludge and taking it into yourself as a necessary part of the human condition and being a person. the way it adds to the themes of the discomfort of the unseemly, unsightly, unpleasant creeping unavoidably in everywhere no matter how you might like to try to ignore it, as the individual people and society at large are trying to digest the war and its aftermath, and finding it a hard and graceless process.......

#lord peter wimsey#dorothy l sayers#the unpleasantness at the bellona club#bellona club#george fentiman#one interesting thing- we know NOTHING about penberthy's military service#or its impact on him#we know he's in the bellona club and that he was in wwi but nothing else#in a book with these themes that's a fascinating lacuna#what did the war do to HIM? in many ways he's the most damaged of everyone by the measure of what he did#i wonder if part of it is that he is a bridge to the other half of the book- the Bright Young Things who put war behind them#who try to find something completely unrelated and opposite to give themselves meaning#he lives in both worlds#anyway idk#but also#on the topic of a mention of the drones in a post about the bellona club#first of all if you haven't read adina's incrediblye jeeves and wooster/wimsey crossover fic green ice do so now#but there's also a fabulous mini-sequel called armistice set in the bellona club on armistice day#go read it now but read green ice first

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of my favorite minor headcanons about Gaudy Night is that when Peter says "I should like to meet [Pomfret]. He is probably the best friend I have in the world" and Harriet is all oh this must be him alluding to how Pomfret being into her has made her realize that she's genuinely worthy of attraction in a way that makes Peter seem less benevolent and more sincere or whatever, IN FACT what he's actually thinking is just ah, the only other dude who really gets what a bummer it is to be rejected by Harriet or something.

Like, I love the idea that just because she's been driving herself crazy and second-guessing herself for the past three hundred pages, she's now also sitting here imputing all these same kinds of mind games on Peter when actually he's just mindlessly saying things in a relatively straightforward, normal way because his mind isn't as tortured as hers on this particular subject.

#lord peter wimsey#harriet vane#dorothy l sayers#gaudy night#reggie pomfret#i do love gaudy night but sometimes i have to admit i find harriet quite irritating#in a way the above is kind of a microcosm of what's great about the whole book#harriet has the same tools to solve it as peter but doesn't because she can't clear her mind#whereas peter solves it in four seconds#and the only thing giving him pause is what harriet's reaction will be#they're two very different people and i'm not convinced harriet is totally fair to him here#i also want to be fair to harriet in turn#by pointing out that she gets all her worrying done in advance#and the reason i see him as being relatively straightforward here is because he saves his freaking out for after they're married#he knows he wants to be with her but has absolutely no idea how that's going to work#he's like “i'll make it work when (not if) it happens” and then kind of hopes for the best?

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's not that Brutha is cheerful, it's that he's naive. The difference is that Brutha ends up NOT being naive. But there's nothing about Arthur that "goes Bursar" IMO. The other thought I had, in a completely different way, was Detritus, but really there's nobody quite like Arthur anywhere, I think.

Carolyn, I'll give you, has control in a different way- but I think the Vetinari comparison came more from the Vetinari-Moist relationship relative to Carolyn-Douglas, where the tyrant on the one hand wants to exploit the rogue's roguishness but also puts their foot down when said roguishness is no longer convenient. The tyrant uses the rogue in I think reasonably analogous ways. I do get the Ridcully comparison though, and think that the Carolyn-Martin relationship is a lot like the Ridcully-Stibbons one, if Martin were at all competent... (Can't speak to Rincewind, I'm not a big fan of his arc.)

Just reminiscing to myself about how one time online I saw someone looking for recs based on loving Discworld (in particular the Moist books) and was like "well if you like the Moist books you may like this thing Cabin Pressure, there's a scheme-y character a bit like Moist in it, and another character who's his Vetinari, and hm, not sure about the other two characters.... maybe Ponder Stibbons and Brutha?"

I was reminiscing about it because my baby brother was rereading Going Postal (he loves it but refuses to read any other Discworld books because he's worried they won't be as good) and I'm also trying to get him into Cabin Pressure and I eventually realized that I'm attempting to make the same argument but structured differently! (He does like Cabin Pressure when I make him listen to it, so there's that.)

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just reminiscing to myself about how one time online I saw someone looking for recs based on loving Discworld (in particular the Moist books) and was like "well if you like the Moist books you may like this thing Cabin Pressure, there's a scheme-y character a bit like Moist in it, and another character who's his Vetinari, and hm, not sure about the other two characters.... maybe Ponder Stibbons and Brutha?"

I was reminiscing about it because my baby brother was rereading Going Postal (he loves it but refuses to read any other Discworld books because he's worried they won't be as good) and I'm also trying to get him into Cabin Pressure and I eventually realized that I'm attempting to make the same argument but structured differently! (He does like Cabin Pressure when I make him listen to it, so there's that.)

#discworld#terry pratchett#sir pterry#cabin pressure#john finnemore#moist von lipwig#douglas richardson#havelock vetinari#carolyn knapp shappey#ponder stibbons#martin crieff#brutha#arthur shappey#as it happens#i've always mentally fancasted benny c as ponder stibbons#at least from a voice perspective#and while i think the character is meant to be quite a bit younger than john finnemore is now#i think he'd genuinely make a great brutha if someone adapted the unadaptable small gods

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

THANK YOU I HAVE BEEN LOOKING FOR THIS FOR AGES

cabin pressure episode sorter anyone??

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Few things get me more annoyed than Raymond Chandler's The Secret Art of Murder, especially the bit where he's like "well I think that Sayers was just frustrated by the fact that mysteries couldn't be about real people because to keep the formula going you have to have them do unreal things" which would have maybe been a really innovative thought if not for the fact that she literally said it herself in Gaudy Night

Though actually the overall problem is that it makes no sense because it's all "the people in these [British golden age] mysteries don't feel REAL, their situations don't feel REAL," when apparently Dashiell Hammett's mysteries all do? Like, has this dude read The Dain Curse? (For the record, I like The Dain Curse, but I also like the [generally significantly less outlandish] British golden age detective stories Chandler dislikes too.)

The difference is that Chandler seems to WANT Hammett's world to be more "real," and while I will not deny that The Continental Op is a fantastic character or that Hammett's works are often really really good (I'm not a huge fan of Maltese Falcon) and that he was an excellent writer- significantly better than Chandler IMO- I don't think that Hammett's dark, often bloody world is that much more "real" than the England of Christie and Sayers and who knows who else, it's just that Chandler wanted it to be more real because he thought it was cooler and that dark=profound and well... he's a noir guy.

But seriously, he says "Hammett gave murder back to the kind of people that commit it for reasons, not just to provide a corpse" after reading, or possibly not reading, The Dain Curse? Or even, if I'm being honest, Red Harvest? And what is more compelling about the murder "reason" in The Thin Man than in any Christie/Sayers "cui bono" plot? After spending half an essay denouncing golden age mysteries for their mannered plotting, Chandler just up and decides that who cares about the plot, it's about vibes. Maybe he just doesn't like manor house mystery vibes.

I'll add too that not only was Hammett a better writer than Chandler, so was Sayers. Her prose is better, but more importantly she is just better at convincing you of what she thinks. I've read a lot of Sayers essays and some of them, ten minutes after I read them, I blink my eyes and am like "well actually isn't that nonsense," but for those ten minutes I bought everything. Chandler tries a similar trick to hers of trying to make a case for something by just being really sure about it and instead, as I read, I just keep thinking "well why do you think this? Why do you think that a good novel is about 'totally different things' than a bad novel? What is it that makes the plot Murder on the Orient Express so obviously low quality to you? Show me what you like about Hammett and what makes him different instead of telling me!"

I'm not trying to say that Chandler should like Golden Age novels/puzzle mysteries, as is clear he doesn't. Some of his criticisms of the genre are sound, but he's arrogant enough to think he's the only one who has thought about it or cares, even in the above case where he dares criticize a writer with a critique that she'd already made herself. AND, and this is probably the bit that gets me the most, he just decides that the hard boiled genre is better because, well, he likes it, and he has good taste, and it's real presumably because it's gritty and masculine and full of completely realistic femme fatales. Though maybe the realism in noir is just the way that the men in them don't expect the femme fatales to be actual humans in that way...? But so many of the flaws in the golden age are present in noirs.

I'll admit, I'm just not a noir person- though if I'm going to read any I prefer the less hard-boiled takes of someone like Cornell Woolrich, or the more psychological approach of a Dorothy B Hughes. But let me tell you, after having read a bunch of Chandler short stories immediately after the above essay (in a collection), I couldn't tell you the plots of more than like two of them and I'm pretty sure that any attempts would mix multiple of them up, because they all felt exactly the same. And some of those plots were outlandish. Maybe what he didn't realize, actually, was that just as the Golden Age writers had a genre and things could get same-y, so could his precious realistic noir. It feels like he just wanted noir to be better, because he liked it and it was his.

#dorothy l sayers#raymond chandler#the secret art of murder#dashiell hammett#incidentally i do agree with chandler that english golden age detective novels are largely better than american ones#philo vance is AWFUL for example#though i do like nero wolfe- and ellery queen has his moments (oh also craig rice)#but some end up feeling a bit silly/twee#and others become more suspense novels than mysteries per se#which is fine but functionally a different genre#i include the link here as i don't usually write this sort of thing and if others are more knowledgeable about noir i welcome critiques#also just a plug here for dorothy b hughes's in a lonely place#which is if anything a “reverse noir” (to use a phrase from the afterword in the edition i read)#completely different than the movie by the way

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Okay, Anton Lesser is obviously perfect, absolutely zero notes. I actually don't think he'd be too big a star for a Bellona Club adaptation, and maybe Clouds of Witness too- I think you could structure the plot to give him enough to do for a respectable big-name-costar treatment.

And I totally see the Miss Meteyard vision for Rachael Stirling! Interesting bones indeed (completely unironically, I'm more than a bit in love with her). My thought for her, possibly overly influenced by her role in Detectorists, was Sheila Fentiman, which I think she'd do a beautiful job with (though she's possibly a bit too old now, most of my reference point roles for her are from ten years ago).

Though actually... I do think that she has Harriet Vane's "curious, deep voice which had attracted [Wimsey] in Court" and there is a part of me that's curious what she'd have done with that role in some hypothetical Strong Poison remake in the 2010s.

Are you still doing the Detective Drama Casting Hour? If so, one of each kind of question, both for a Wimsey adaptation (and feel free to be flexible on timing): 1) Who would you cast to play Mr Murbles?

2) What role would you give to Rachael Stirling? (I have my own idea but I want to hear yours, partly because I think I'm wrong)

I mean, obviously he's too big a star for the part, but Anton Lesser would delight me. His comic timing and gravitas are alike impeccable, and he has enough authority that one can absolutely imagine Lord Peter saying "--don't laugh, I couldn't argue the point with Murbles!"

Perhaps the obvious choice for Rachael Stirling is Miss Meteyard. I'm not sure, to be honest, where else I would place her, except in the Shrewsbury SCR.

#wimseyverse#detective drama casting hour#rachael stirling#anton lesser#lord peter wimsey#harriet vane#miss meteyard#sheila fentiman#mr murbles#ACTUALLY#i say she might be too old for it#but actually i think bellona club w a sheila who is older than george would be quite interesting#though i suppose if they did a christie style “everything is in the 30s”#rather than sayers's real time settings#a sheila in her 40s would prob be not far off the right age for bellona club#given all the great war stuff

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

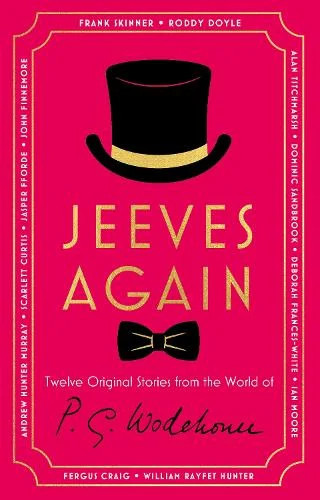

GUYSSSS

So John Finnemore is listed as a contributor to a Jeeves and Wooster pastiche collection.... but also I think I already have heard him perform the story? And if it's the same one, it's amazing?!?!

I'm rarely into pastiches (which causes me problems in some corners of Sherlock Holmes fandom lol) and so this is not the kind of thing I'd ordinarily think to read, but I DO happen to know that one of them is really good as well as well as just am very tickled to have been exposed to the story "ahead of the line"... so that's really fun!

(I know who at most like three of the others are but I'm sure they're great too!)

#john finnemore#jeeves books#jeeves and wooster#reginald jeeves#bertie wooster#pg wodehouse#can i just say#hearing this performed was one of the greatest moments of my life#and if you have the recorded tall tales that this was performed at#please dm me#not just that i'd love to relisten to it#but i did not take enough photos in general of that evening

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Yeah, there is DEFINITELY a degree to which all of this only works because of how good a writer Sayers is. She's very good at creating things that only work when phrased in her own prose, and in fact I think I owe you a response on another post (about Gaudy Night's construction) that really plays on that.

To a degree I do think Wimsey is a hard character to cast/play- my personal fancast would be a Frasier-era David Hyde Pierce, just because (while the Niles/Daphne relationship is nothing like the Peter/Harriet one) DHP is demonstrably great at both the comedy and the emotions and I think, with a good enough British accent, he could be great. But honestly to get anyone who can both passably visually fit the bill AND portray even a part of Wimsey's character is a plus, and Petherbridge absolutely did that.

My thing, though, is that his Wimsey so rarely smiles. I genuinely think that similar line deliveries but with more of a twinkle in the eye and smile on the lips would have come across both softer and funnier. I don't know- I do suspect that he was directed to play it this way but it just makes him feel joyless in a way that book-Wimsey never ever does.

finished have his carcase and going to agree with you that it's the best of the '87 adaptations simply because the book itself gets so convoluted by the second half, it's definitely not sayers at her best. i love how the show brought out harriet's sleuthing contributions (and peter's tbh, there were too many detectives in the novel); i'm OBSESSED that they gave the gallop over the beach to bunter; the finale felt more satisfying in the sense of getting the murderers to justice; the argument was really well-structured as you said; also the wrist kiss (yes i know that's peter taking a STEP but in a way it's no more overt than stuff he said to her while dancing).

things i wish they managed to put in: that incredible dialogue between harriet and peter while they walk on the beach and find the boot, the bible, and the chips packet (yes it's too wordy and a little absurd for the tone of the adaptation but IMAGINE); harriet realizing peter hasn't proposed to her for awhile and deluding herself that she's glad about it; peter going on his knees in front of harriet when she says their constant arguing is dreary, because SO much of harriet's interactions with peter come down to body language, and unfortunately the adaptations miss so many of those cues. the main one that they preserved (and i mean thank god for petherbridge and walter for giving us that scene at all) is peter taking off his hat in gaudy night at the final proposal.

@no-where-new-hero

So I DO think it's the best of the 87 adaptations but I actually love the book and am loath to admit its flaws so I do so for other reasons...? It's a blind spot, I know lol (I genuinely love reading the Playfair bit despite not having a head for that sort of thing at all, there's just something kind of soothing about watching smart people be smarter than you)

I do disagree on the wrist kiss just because while dancing, everything is more or less still in "comic opera" mode- and I think it's significant that it's only in The Argument that he leaves that. I think the fact that, for the most part, Wimsey STAYS in that mode for the whole book except for The Argument, which he only has because Harriet goads him, is significant. I like Petherbridge but I don't think he really nails "comic opera" mode (except for "port or sherry/burgundy") and isn't really asked to, given the way the story is structured and the fact that the show overall jettisons the main relationship conflict of the book (as I've mentioned elsewhere). All the sincerity of romantic gestures, the feeling that he's really trying, gives me hives.

And TBH I think it might be one of the reasons why I just can't go full on the Petherbridge train in these adaptations- it's like Harriet says "it would be awful if you were funny all the time" in SP and he immediately just stops trying to be funny....? Not literally, but a lot of the lines that I found really funny and sweet in the book feel a bit overly earnest and cloying in this adaptation. I don't even know that it's his fault- again as I've written about elsewhere, my assumption is it was purposeful direction given the writing, and he can be very funny in smaller moments and facial expressions. But it's one place where the show falls down for me.

(In general, the placement of The Argument is really interesting, because it's so much earlier in the book and while overall, as mentioned, I DO think the book is better- and I actually recommend, if you get an opportunity, to reread SP/HHC/GN in order because it's great, just did it this weekend- I completely get why they changed the structure here and made it later with more dramatic impact, rather than, as in the book, earlier and with more ramifications for Harriet emotionally as she sorts out her feelings. That said, it DOES bother me in the show that they have Harriet explicitly ask Peter to go away, he very dramatically does, and then... he just heads right back into investigating and pops back in the next day? If they were going to make that change I feel like it needed to be played up a bit more, though they do try.)

I do agree with you that a lot of the body language is missing, which is actually fascinating because, as I alluded to earlier, what body/facial language they DO have is so good for the most part! One of my favorite tiny moments that I do think is a bit better than the book is that they give the newspaper article bit to Harriet rather than Sally Hardy (or rather, they very smartly give the beginning bit to Hardy, though IMO Petherbridge underplays it a bit, and then give the second half to Harriet, and it's hilarious as they take Sayers's own over the top wording and have her be sarcastic at Wimsey about it). And moving the wine-colored dress scene to the revolving door worked VERY well, and both were excellent. I've mentioned how perfect the scene of Harriet finding the body is as well, and how real and visceral it feels, something that Sayers doesn't quite convey in the same way.

That said... I do think, now that I give it thought, that the main reason I like HHC better than SP (despite how much I enjoy Miss Climpson in SP) is just that Harriet is not only in it more but gets more time/space to shine, by which I mean Harriet Walter, who is a goddess and who makes literally everything better. She just nails everything here, and she TRIES in GN but the whole... everything just kept pulling her down. I will say though- I find the idea fascinating that she and Petherbridge rewrote the proposal, but I do wonder whose idea it was to pull the phrase "my dear idiot" from the book line about the Corporation garbage dump lol

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

finished have his carcase and going to agree with you that it's the best of the '87 adaptations simply because the book itself gets so convoluted by the second half, it's definitely not sayers at her best. i love how the show brought out harriet's sleuthing contributions (and peter's tbh, there were too many detectives in the novel); i'm OBSESSED that they gave the gallop over the beach to bunter; the finale felt more satisfying in the sense of getting the murderers to justice; the argument was really well-structured as you said; also the wrist kiss (yes i know that's peter taking a STEP but in a way it's no more overt than stuff he said to her while dancing).

things i wish they managed to put in: that incredible dialogue between harriet and peter while they walk on the beach and find the boot, the bible, and the chips packet (yes it's too wordy and a little absurd for the tone of the adaptation but IMAGINE); harriet realizing peter hasn't proposed to her for awhile and deluding herself that she's glad about it; peter going on his knees in front of harriet when she says their constant arguing is dreary, because SO much of harriet's interactions with peter come down to body language, and unfortunately the adaptations miss so many of those cues. the main one that they preserved (and i mean thank god for petherbridge and walter for giving us that scene at all) is peter taking off his hat in gaudy night at the final proposal.

@no-where-new-hero

So I DO think it's the best of the 87 adaptations but I actually love the book and am loath to admit its flaws so I do so for other reasons...? It's a blind spot, I know lol (I genuinely love reading the Playfair bit despite not having a head for that sort of thing at all, there's just something kind of soothing about watching smart people be smarter than you)

I do disagree on the wrist kiss just because while dancing, everything is more or less still in "comic opera" mode- and I think it's significant that it's only in The Argument that he leaves that. I think the fact that, for the most part, Wimsey STAYS in that mode for the whole book except for The Argument, which he only has because Harriet goads him, is significant. I like Petherbridge but I don't think he really nails "comic opera" mode (except for "port or sherry/burgundy") and isn't really asked to, given the way the story is structured and the fact that the show overall jettisons the main relationship conflict of the book (as I've mentioned elsewhere). All the sincerity of romantic gestures, the feeling that he's really trying, gives me hives.

And TBH I think it might be one of the reasons why I just can't go full on the Petherbridge train in these adaptations- it's like Harriet says "it would be awful if you were funny all the time" in SP and he immediately just stops trying to be funny....? Not literally, but a lot of the lines that I found really funny and sweet in the book feel a bit overly earnest and cloying in this adaptation. I don't even know that it's his fault- again as I've written about elsewhere, my assumption is it was purposeful direction given the writing, and he can be very funny in smaller moments and facial expressions. But it's one place where the show falls down for me.

(In general, the placement of The Argument is really interesting, because it's so much earlier in the book and while overall, as mentioned, I DO think the book is better- and I actually recommend, if you get an opportunity, to reread SP/HHC/GN in order because it's great, just did it this weekend- I completely get why they changed the structure here and made it later with more dramatic impact, rather than, as in the book, earlier and with more ramifications for Harriet emotionally as she sorts out her feelings. That said, it DOES bother me in the show that they have Harriet explicitly ask Peter to go away, he very dramatically does, and then... he just heads right back into investigating and pops back in the next day? If they were going to make that change I feel like it needed to be played up a bit more, though they do try.)

I do agree with you that a lot of the body language is missing, which is actually fascinating because, as I alluded to earlier, what body/facial language they DO have is so good for the most part! One of my favorite tiny moments that I do think is a bit better than the book is that they give the newspaper article bit to Harriet rather than Sally Hardy (or rather, they very smartly give the beginning bit to Hardy, though IMO Petherbridge underplays it a bit, and then give the second half to Harriet, and it's hilarious as they take Sayers's own over the top wording and have her be sarcastic at Wimsey about it). And moving the wine-colored dress scene to the revolving door worked VERY well, and both were excellent. I've mentioned how perfect the scene of Harriet finding the body is as well, and how real and visceral it feels, something that Sayers doesn't quite convey in the same way.

That said... I do think, now that I give it thought, that the main reason I like HHC better than SP (despite how much I enjoy Miss Climpson in SP) is just that Harriet is not only in it more but gets more time/space to shine, by which I mean Harriet Walter, who is a goddess and who makes literally everything better. She just nails everything here, and she TRIES in GN but the whole... everything just kept pulling her down. I will say though- I find the idea fascinating that she and Petherbridge rewrote the proposal, but I do wonder whose idea it was to pull the phrase "my dear idiot" from the book line about the Corporation garbage dump lol

#lord peter wimsey#dorothy l sayers#harriet vane#have his carcase#a dorothy l sayers mystery#i will note that while i said that i prefer hhc to sp despite loving miss climpson#what i mean is that when rewatching i skip around for the harriet scenes and the miss climpson scenes

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just binge-reread a bunch of Sayers which is why I'll probably be binge-posting over the next week or so but I do want to say- something I appreciate about Strong Poison the book over the 87 adaptation is that we don't know AT ALL until Wimsey visits Harriet that he's interested in the case because he's in love with/infatuated with her.

I think the 87 adaptation has its highs and lows, but one mistake I think was telegraphing it from the start in ways that are NOT subtle and also just a smidge creepy on occasion...? I don't know, but even if it had been done perfectly, there is just something remarkable about the first indication of what the hell is going ON in Strong Poison (the book) being the phrase "and his heart turned to water" when Harriet smiles at Wimsey. What a perfectly evocative six word phrase that suddenly clarifies everything- not just the overall situation but the actual emotions that he's feeling and the weird decisions he's making and the energy he's exuding.

Petherbridge is able to convey some of the emotions, and I understand that his "heart turning to water" is unfilmable per se, but still, that turning point of clarity is definitely missed in the show adaptation, though I do think that Walter's smile at him is exactly the kind that WOULD turn his heart to water. (Have I ever mentioned that I think she is beautiful and perfect?)

#lord peter wimsey#dorothy l sayers#harriet vane#strong poison#a dorothy l sayers mystery#edward petherbridge#harriet walter

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love this!! And I totally agree, the books are so much better in order (though I think that Whose Body? and Five Red Herrings can be safely skipped). You get so much development of both people and ideas on pretty much every topic except class (which, if anything, arguably gets WORSE over time).

I'd add a couple of points:

There's a third interesting woman in Bellona Club, Sheila Fentiman. She disappears a bit in the narrative, but in some ways I find her the most interesting for two related reasons: she seems like an unconscious prelude to the central conflict in Gaudy Night, about whether women marry men who become their "jobs," and she also probably most closely reflects what Sayers's married life actually was like or was on the road to becoming. In fact, I'd argue (and I actually started a post on this but never made it more than a paragraph in) that Ann Dorland and Sheila Fentiman are both elements of Sayers, with Ann Dorland being not dissimilar from Sayers's own physical description at that time as well as ending up with the kind of guy who Sayers married (and was initially very happy with), and Sheila Fentiman lived the troubled and nearly-effaced life that Sayers was slowly sliding into, or could have had she been a different kind of person. The thing is, going back to the Gaudy Night comparison, Sheila is a much more... realistic vision of marriage than any that you get in Gaudy Night! Likely (in universe at least) because it's Peter and not Harriet who knows her, but she's an ordinary woman married to a man who she loves and making the best of it even as life throws its worst at her (and her husband doesn't exactly help). I've wondered whether it's Sayers's increased frustration with and cynicism about her marriage that led her on the journey from Bellona Club, in which a long suffering woman trying to make things work (however degradingly) with a difficult husband is seen as praiseworthy and a sign of character, to Gaudy Night, in which the idea of being a woman stuck in a marriage with someone who takes the things that matter to you away from you shows weakness in some way. It's one of the things about Gaudy Night that gives me serious pause, the idea that simultaneously a relationship needs to be something you overwhelmingly care about yet also needs to be something that, if you care TOO much about, it means that you are either subdued as a person or subduing your partner. In lots of ways, the Annies and the Sheila Fentimans of the world are right about having obligations toward other people, and the Sayers of 1935 who had money and success and a powerful personality and a shitty marriage seems to have lost a bit of perspective on that. (I love Gaudy Night but I also, in some ways, think it's a deeply messed up book, especially re class and the "proper job" nonsense, but that's a separate thing that I wrote about here.)

What I find fascinating is that Peter doesn't just get far more physical description than Harriet, but Harriet is allowed to have the "male gaze" when looking at Peter and to find him attractive! That so rarely happens in books like these, including books written by women. I linked elsewhere to my post about how much I dislike AS Byatt's Possession but in the notes there IIRC I mentioned how annoying Byatt's description of what's her name's body is, in this way that feels like it's meant to be somehow both clinical and literary but instead just comes across as r/menwritingwomen in a kind of sordid way. Sayers never does this with women, and she doesn't really either do it with men, but she does allow women to look at men's physical features and evaluate their attractiveness. We know what Harriet thinks of what Peter looks like in a bathing suit but not vice versa, for example, and we get to see not just a somewhat objectifying "he's got good legs" in Have His Carcase but the much more intimate "this particular person's features are beautiful to me" in the punt scene in Gaudy Night. Other people may find Peter weird-looking, but Harriet never does. Peter then describes Harriet in Busman's Honeymoon... but more in the way that the "interestingly ugly" male protagonists in these kinds of books are often described- not classically good-looking but still incredibly compelling specifically to them in their look or voice or character or whatever, the Mr Rochester vibe. It's a really interesting reversal of the ways that male vs female romantic interests are often physically described by each other in books like this. The man so often has "won" this obviously attractive woman by being cool and interesting but not necessarily classically attractive himself, and the woman has the discernment to appreciate this man. Here, it's the exact opposite- the man has the discernment to appreciate this woman, who has managed to "win" the attractive (to her physically, but also on a number of other significant axes perceptible to all, such as wealth and intelligence) man.

Finding Harriet Vane: A mini-essay on Sayers' Women

You really do need to read the Wimsey books in order, if just to watch in fascination how Sayers develops her Ideas About Women, which culminates in the whole Harriet Vane arc. For context, Christie doesn’t really have Ideas About Women. She has Ideas About People. Her vision of psychology comes down to environment and social pressures, but these are less frequently gender-based. Class, age, and income dictate her characters much more than relations between the sexes, even in crimes of passion (and there aren’t many).

Sayers, on the other hand, develops the theme that finally comes to full chorus in Gaudy Night. E.g., Whose Body? is very much in the Christie vein. You get the impression she could keep going on like this for several more books, but she doesn’t; she writes Clouds of Witness and gives Peter a mother, a sister, and opens her theme of privilege and sexuality in the form of the farmer’s wife. The wife is vital here to understanding how Sayers sets up Peter as the peer of the realm, used to taking because that's his privilege. I love the pithiness of this line:

[she had] a shape so wonderful that even in that strenuous moment sixteen generations of feudal privilege stirred in Lord Peter's blood.

This image is vital to understanding how Harriet (rightly) sees him as presumptuous in Strong Poison and sets up why she refuses to tangle with him on his own turf.

Unnatural Death offers another vision of womanhood—queer and single womanhood. The relationships between Agatha Dawson and Clara Whittaker, and to a lesser extent Mary Whittaker and Vera Findlater, are clearly Sapphic and complicate the easy upper-class commerce of seduction and possession. In fact, it turns conventional heterosexuality into a farce, in the scene when “Mrs. Forrest” attempts to seduce “Mr. Templeton" to poison him.

He pulled her suddenly and violently to him, and kissed her mouth with a practised exaggeration of passion. He knew then. No one who has ever encountered it can ever again mistake that awful shrinking, that uncontrollable revulsion of the flesh against a caress that is nauseous. He thought for a moment that she was going to be actually sick.

The two principals are in disguise; one is a lesbian and the other suspects her of murder. Heterosexuality becomes a pantomime, a play of dishonesty in violent and overt language (Sayers, notably by Gaudy Night and Busman's Honeymoon, gets much more coy about real and honest feelings). It's the yearning for honesty that becomes the knot to unravel with Harriet (proclaimed pretty baldly in Have His Carcase).

Aside from queering relationships, this book also introduces us to the inimitable Miss Climpson: the smart sleuthing "old maid" who Parker first conventionally mistakes for Peter's mistress and represents Sayers slyly breaking expectations. A proto-Miss Marple, Miss Climpson both provides Peter with a sensibility of feminism that will eventually help redeem him--he's not too proud to see the worthiness of an independent single woman--and (on a narrative level) allows Sayers to explore female protagonism and her own religious outlook in her fiction.

Finally, The Unpleasantness of the Bellona Club offers us two major women, who interestingly collide in the character of Harriet Vane: the artistic Marjorie Phelps, who exists in a relationship of ambiguous intimacy with Peter, and the plain persecuted Ann Dorland, whose essential non-villainy gets endangered by a man she's in love with. I slightly wonder whether Sayers got her idea for Harriet from the way she wrote Ann Dorland especially; Ann, despite her limited page time, suggests the same love problems, level-headedness, and appeal to Wimsey that typifies Harriet, though isn't allowed the same play.

Sayers has been setting up Peter and his relationships this way for maximum impact when we get to Strong Poison. Harriet, interestingly, gets very little initial on-page description in this book (as opposed to, say, Ann Dorland or Mary Whittaker), and there's the simultaneous sense of her being disappeared and becoming typified not by her looks but by her words/voice, as her dialogue is how we get to know her.

There is a great deal of absurd charm in the openings of the Wimsey/Vane relationship, of course, but Sayers reminds us not to get carried away by it with one line:

[The books] could not show him how to save the woman he imperiously wanted from a sordid death by hanging.

Clearly, we know Peter wants Harriet. We even believe that the way he wants her is rather nice, and at least infinitely superior to the way she had been wanted by her lame ex Phillip. But Sayers cautions us with that fantastic adverb, "imperiously." Remember the farmer's wife in Clouds of Witness, she seems to say. Remember that the way Peter likes Harriet has as much to do with the certainty of his own brilliance as how he sees her. Remember that, even if he says he's not blackmailing her into marrying him by helping her out, he's still Lord Peter, second son of the duke.

What's most fascinating about tracing this evolution, for me, is that you almost see Harriet happening upon Sayers in real time: yes, she's a self-insert, but she's also the natural conclusion to a long line of women through whom Sayers has been trying to talk about women and class and obligation and love, and the best medium for her to come to her final thesis.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

As you can see, agreed on 5'9 being the likely height- interesting about the "party height" thing, but I'm not sure as Wimsey says it in Clouds of Witness in the context of detective work- for which he'd want to be precise. The 5'9 in Busman's Honeymoon is from Harriet's third person limited narration, which could mean anything- on the one hand she's unlikely to have actually measured him personally lol but if he's her height or about it then she'd likely have some idea of his actual height.

THOUGH- on that note, another thing I left out of the other post- the heights/configurations of Peter and Harriet in Busman's Honeymoon don't really work for them being the same height! My guess is that she wrote them based on the stage directions for the original play, which was largely written pre-Gaudy Night iirc, and that the actors in it may not have been the same height- or it's just possible that when novelizing the play she forgot she'd either a) had them be the same height or b) had Harriet be "medium height" rather than tall.

All this being said, the idea of a "party height" or "social height" is certainly plausible from a purely human perspective though- I remember at my high school graduation the group of girls who were "5'2" were of very varying heights in actuality... and my sister is 5'10 but calls it 5'9 for the opposite reason that Wimsey might per your supposition lol

The Incredible Shrinking Wimsey

As alluded to in my previous post from earlier today...

Okay, so there is a pretty common thing you see from people, whether they like Gaudy Night or hate it, which is this idea that Sayers made Wimsey taller and/or hotter over time- as, some say, she fell more and deeper in love with him. The "hotter" I think is debatable, though I fall on the side of not- IMO his actual physical description remains very consistent over time, with him being described as having a "high beaked profile" as late as Busman's Honeymoon, and his personal character traits/manners and wealth/title/intelligence do a lot of work for him in terms of attractiveness to women. (The strongest counterargument to this point is probably Murder Must Advertise in which he's somehow crazy attractive to multiple women while undercover- presumably that's a combination of the manners, intelligence, and... macho pond diving ability? Not really my favorite Sayers book tbh. We'll get back to it.)

But it's VERY easy to refute the "taller" allegation, and in fact when you try to you notice something weird- that Wimsey may arguably get SHORTER over the course of the books and then yoyo back.

Do we care about continuity?

Sayers and continuity, I will say, is weird. I love how she remembers incredibly clearly that she had Abrahams the cartoonishly Jewish jeweler show Wimsey a ruby engagement ring in an earlier short story and has Abrahams sell him that very ring in Busman's Honeymoon (in fact I love it enough that I wrote a missing scene fic about it). I also perversely love how she has Harriet de-age by about three years for literally no reason and how, to make the scenario for Busman's Honeymoon work, she transfers her upbringing from the city (as made clear in Have His Carcase) to the country. It's like she cares more about some things than others, and the things she cares about are the vibes. I respect that, because her vibes are generally impeccable.

And that's why I think that it's actually pretty important that Sayers may actually shrink Wimsey to make a point, and important to point out to people that she very much does not make him taller, certainly not in a bid to emphasize his attractiveness. So let's go through the known stats (and if I'm missing anything, please comment to add!):

A) When you google "Lord Peter Wimsey height" you get that he is of "average height." I refuse to word search all the books until I find the exact reference for this but I don't doubt it's there somewhere.

B) In Whose Body?, Wimsey is described as "rather a small man, but not undersized," in comparison to if he'd been "six foot three." Vague but definitely he's not meant to be tall per se.

C) In Clouds of Witness, as Wimsey and Parker are trying to figure out whether "No. 10" could have gotten over the wall, Wimsey says that he's five foot nine. This is unambiguous- he says it straight out. (Parker, in contrast, is six feet.)

D) In Murder Must Advertise, Wimsey is stated to be too short to be a Metropolitan Police officer. This is VERY often pulled out as an example of how short he is, but the real question is what it actually means. In doing some online searching, I got anywhere between 5'7 and 5'10 as the potential required height (with 5'10 being the height as listed in the Lord Peter Wimsey Companion). HOWEVER, I believe that the required height at the time would be somewhere between 5'8 and 5'9, as expressed in this Parliamentary record. If someone can find a better reference point, please share! But in the meantime it would seem that Wimsey may be shorter than 5'9, his previously listed height in Clouds of Witness.

E) Gaudy Night is a FASCINATING one, so I'm going to divide it into two parts. One is the part that people tend to pull out, in my opinion wrongly, to indicate that Wimsey got taller. The other is the part that makes me even more convinced that Sayers shrank him.

E1) It's sometimes said that Wimsey clearly got taller because Harriet "can see him in a crowd." Let me pull out the quote:

Scanning those sacred precincts, therefore, from without the pale, Harriet became aware that the local colour included a pair of slim shoulders tailored to swooning-point and carrying a well-known parrot profile, thrown into prominence by the acute backward slant of a pale-grey topper. A froth of summer hats billowed about this apparition, so that it resembled a slightly grotesque but expensive orchid in a bouquet of roses.

Nothing about him being tall and visible, just about his hat being tall and visible and his face being seen underneath it! And he may well be taller than the women he's surrounded by, but at anywhere between 5'7 and 5'9 (as established above) he most likely would be, given that men tend to be taller than women- which we'll return to below. There is no indication from here that Wimsey is meant to be shown as tall.

E2) More tellingly, there's the famous line closer to the end of the book:

"Bless the man, if he hasn't taken my gown instead of his own! Oh, well, it doesn't matter. We're much of a height and mine's pretty wide on the shoulders, so it's exactly the same thing."

I can't easily find the average height of an English woman in the 1930s, but after reading a bunch of different sites and articles and such and extrapolating, I get a general impression of between 5'1 and 5'4. For context, the average height of an English woman now is apparently 5'3-5'4, and while immigration from developing countries may affect that, average heights worldwide still seem to have overall increased since the start of the 20th century, if not necessarily by massive margins. These days, the countries that have the tallest average height for women have it at about 5'6/5'7, as far as I can tell.

We don't get a tremendous amount of vital statistics about Harriet Vane. Wimsey describes her as "long limbed" in Busman's Honeymoon, which presumably implies tall (though could also just say something about her proportions), but at the same time she is never, to my knowledge, remarked upon by any other character to be of any kind of exceptional height. This is subjective, of course, but from experience (as a shortie whose sister is six inches taller), once a woman is about 5'9 people start making comments, so let's assume that she's tallish but not notably Tall. 5'7 or 5'8 would work at the upper end of that, which is the height we established from Murder Must Advertise for Wimsey, as it happens!

Obviously, Harriet may not be EXACTLY the same height as Wimsey- but we know that she can't be that much shorter from the above quote. Here's an indication, though, that she may even be shorter than 5'7- the fact that she's around the same height as Annie, who is described as of medium height. We deduce this from two places at least- Lord Saint George says that the woman he saw at Shrewsbury is "about your height or a bit less" to Harriet, and Miss Pyke observes that the dress on the dummy is for a woman of "medium height." While as Gherkins notes Annie may be a bit shorter than Harriet, "medium height" in the context of women's clothing would, given height tendencies, be shorter than "medium height" for a man like Wimsey. So even if Harriet is taller than Annie, and relatively tall for a woman, for her to be both "medium height" and about the same height as Wimsey he'd have to be on the short side.

And, finally,

F) In Busman's Honeymoon, we're told that "[Wimsey's] height was a sensitive point with him" and then that he is... five foot nine. Just the same as he'd been in Clouds of Witness.

All this to say- it seems pretty clear to me that Wimsey starts off about 5'9, a perfectly respectable male height, and either stays that way or gets even shorter, depending on how you look at it. 5'9 a perfectly respectable male height while not being considered tall per se, at least in Europe. Wimsey also (as he's often described) being very slim would contribute perhaps to him seeming a bit smaller than he is.

So why does Wimsey shrink? I like to think that I've made the case for it that he does, and the reason why I emphasize it (rather than, as in my previous post, just yelling about him not growing) is because it's hard not to imagine that she very much did it to make a point.

Murder Must Advertise, as alluded to above, I think is partly a function of a certain kind of action-novel laziness rather than a statement about Wimsey as a person, to be honest. "Death Bredon" is a rogue, and rogues have women fall for them and use it. By showing that Wimsey is able to attract so many women as Death Bredon, without the advantages of name, title, money, and manners (or at least, his usual kind of manners), and also without height, Sayers conveys his charm. Again, I don't find it particularly convincing, but I do find it interesting that much of the charm and mystery that gets Dian de Momerie, at least, interested in "Death Bredon" is based on his athleticism and nimbleness, which actually are helped by his comparatively small and slim stature. A taller man may not have managed that dive into a pond in the same way...

Gaudy Night... well, I mean, that's the one that is basically all narrated by Harriet, who is falling/has fallen in love with Wimsey. She's naturally going to be biased, and her biases and blind spots are basically the structure around which the book is constructed. The whole book is constructed around how Harriet sees Wimsey, and so the fact that they are the same height, that Wimsey is significantly shorter (for example) than Reggie Pomfret, that Wimsey's self defense classes with Harriet focus on skill and using the other person's strength to compensate for being small yourself, that Wimsey get Harriet to accept his proposal by putting his head down and making himself smaller... the whole book is about Harriet seeing Wimsey as equal to her so him being specifically physically small relative to other men in a way that will not overpower her is very relevant. (In marked contrast, incidentally, to AS Byatt's Possession, about which I've written a long screed about how much I hate its approach to male/female dynamics as relate, among other things, to size.)

All of this is less important to be spelled out in Busman's Honeymoon, at which point they're married already and Harriet feels good about it, all things being equal. So Wimsey can safely go back to being 5'9 again. As, indeed, he pretty much always was.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Incredible Shrinking Wimsey

As alluded to in my previous post from earlier today...

Okay, so there is a pretty common thing you see from people, whether they like Gaudy Night or hate it, which is this idea that Sayers made Wimsey taller and/or hotter over time- as, some say, she fell more and deeper in love with him. The "hotter" I think is debatable, though I fall on the side of not- IMO his actual physical description remains very consistent over time, with him being described as having a "high beaked profile" as late as Busman's Honeymoon, and his personal character traits/manners and wealth/title/intelligence do a lot of work for him in terms of attractiveness to women. (The strongest counterargument to this point is probably Murder Must Advertise in which he's somehow crazy attractive to multiple women while undercover- presumably that's a combination of the manners, intelligence, and... macho pond diving ability? Not really my favorite Sayers book tbh. We'll get back to it.)

But it's VERY easy to refute the "taller" allegation, and in fact when you try to you notice something weird- that Wimsey may arguably get SHORTER over the course of the books and then yoyo back.

Do we care about continuity?

Sayers and continuity, I will say, is weird. I love how she remembers incredibly clearly that she had Abrahams the cartoonishly Jewish jeweler show Wimsey a ruby engagement ring in an earlier short story and has Abrahams sell him that very ring in Busman's Honeymoon (in fact I love it enough that I wrote a missing scene fic about it). I also perversely love how she has Harriet de-age by about three years for literally no reason and how, to make the scenario for Busman's Honeymoon work, she transfers her upbringing from the city (as made clear in Have His Carcase) to the country. It's like she cares more about some things than others, and the things she cares about are the vibes. I respect that, because her vibes are generally impeccable.

And that's why I think that it's actually pretty important that Sayers may actually shrink Wimsey to make a point, and important to point out to people that she very much does not make him taller, certainly not in a bid to emphasize his attractiveness. So let's go through the known stats (and if I'm missing anything, please comment to add!):

A) When you google "Lord Peter Wimsey height" you get that he is of "average height." I refuse to word search all the books until I find the exact reference for this but I don't doubt it's there somewhere.

B) In Whose Body?, Wimsey is described as "rather a small man, but not undersized," in comparison to if he'd been "six foot three." Vague but definitely he's not meant to be tall per se.

C) In Clouds of Witness, as Wimsey and Parker are trying to figure out whether "No. 10" could have gotten over the wall, Wimsey says that he's five foot nine. This is unambiguous- he says it straight out. (Parker, in contrast, is six feet.)

D) In Murder Must Advertise, Wimsey is stated to be too short to be a Metropolitan Police officer. This is VERY often pulled out as an example of how short he is, but the real question is what it actually means. In doing some online searching, I got anywhere between 5'7 and 5'10 as the potential required height (with 5'10 being the height as listed in the Lord Peter Wimsey Companion). HOWEVER, I believe that the required height at the time would be somewhere between 5'8 and 5'9, as expressed in this Parliamentary record. If someone can find a better reference point, please share! But in the meantime it would seem that Wimsey may be shorter than 5'9, his previously listed height in Clouds of Witness.

E) Gaudy Night is a FASCINATING one, so I'm going to divide it into two parts. One is the part that people tend to pull out, in my opinion wrongly, to indicate that Wimsey got taller. The other is the part that makes me even more convinced that Sayers shrank him.

E1) It's sometimes said that Wimsey clearly got taller because Harriet "can see him in a crowd." Let me pull out the quote:

Scanning those sacred precincts, therefore, from without the pale, Harriet became aware that the local colour included a pair of slim shoulders tailored to swooning-point and carrying a well-known parrot profile, thrown into prominence by the acute backward slant of a pale-grey topper. A froth of summer hats billowed about this apparition, so that it resembled a slightly grotesque but expensive orchid in a bouquet of roses.

Nothing about him being tall and visible, just about his hat being tall and visible and his face being seen underneath it! And he may well be taller than the women he's surrounded by, but at anywhere between 5'7 and 5'9 (as established above) he most likely would be, given that men tend to be taller than women- which we'll return to below. There is no indication from here that Wimsey is meant to be shown as tall.

E2) More tellingly, there's the famous line closer to the end of the book:

"Bless the man, if he hasn't taken my gown instead of his own! Oh, well, it doesn't matter. We're much of a height and mine's pretty wide on the shoulders, so it's exactly the same thing."

I can't easily find the average height of an English woman in the 1930s, but after reading a bunch of different sites and articles and such and extrapolating, I get a general impression of between 5'1 and 5'4. For context, the average height of an English woman now is apparently 5'3-5'4, and while immigration from developing countries may affect that, average heights worldwide still seem to have overall increased since the start of the 20th century, if not necessarily by massive margins. These days, the countries that have the tallest average height for women have it at about 5'6/5'7, as far as I can tell.

We don't get a tremendous amount of vital statistics about Harriet Vane. Wimsey describes her as "long limbed" in Busman's Honeymoon, which presumably implies tall (though could also just say something about her proportions), but at the same time she is never, to my knowledge, remarked upon by any other character to be of any kind of exceptional height. This is subjective, of course, but from experience (as a shortie whose sister is six inches taller), once a woman is about 5'9 people start making comments, so let's assume that she's tallish but not notably Tall. 5'7 or 5'8 would work at the upper end of that, which is the height we established from Murder Must Advertise for Wimsey, as it happens!

Obviously, Harriet may not be EXACTLY the same height as Wimsey- but we know that she can't be that much shorter from the above quote. Here's an indication, though, that she may even be shorter than 5'7- the fact that she's around the same height as Annie, who is described as of medium height. We deduce this from two places at least- Lord Saint George says that the woman he saw at Shrewsbury is "about your height or a bit less" to Harriet, and Miss Pyke observes that the dress on the dummy is for a woman of "medium height." While as Gherkins notes Annie may be a bit shorter than Harriet, "medium height" in the context of women's clothing would, given height tendencies, be shorter than "medium height" for a man like Wimsey. So even if Harriet is taller than Annie, and relatively tall for a woman, for her to be both "medium height" and about the same height as Wimsey he'd have to be on the short side.

And, finally,

F) In Busman's Honeymoon, we're told that "[Wimsey's] height was a sensitive point with him" and then that he is... five foot nine. Just the same as he'd been in Clouds of Witness.

All this to say- it seems pretty clear to me that Wimsey starts off about 5'9, a perfectly respectable male height, and either stays that way or gets even shorter, depending on how you look at it. 5'9 a perfectly respectable male height while not being considered tall per se, at least in Europe. Wimsey also (as he's often described) being very slim would contribute perhaps to him seeming a bit smaller than he is.

So why does Wimsey shrink? I like to think that I've made the case for it that he does, and the reason why I emphasize it (rather than, as in my previous post, just yelling about him not growing) is because it's hard not to imagine that she very much did it to make a point.

Murder Must Advertise, as alluded to above, I think is partly a function of a certain kind of action-novel laziness rather than a statement about Wimsey as a person, to be honest. "Death Bredon" is a rogue, and rogues have women fall for them and use it. By showing that Wimsey is able to attract so many women as Death Bredon, without the advantages of name, title, money, and manners (or at least, his usual kind of manners), and also without height, Sayers conveys his charm. Again, I don't find it particularly convincing, but I do find it interesting that much of the charm and mystery that gets Dian de Momerie, at least, interested in "Death Bredon" is based on his athleticism and nimbleness, which actually are helped by his comparatively small and slim stature. A taller man may not have managed that dive into a pond in the same way...

Gaudy Night... well, I mean, that's the one that is basically all narrated by Harriet, who is falling/has fallen in love with Wimsey. She's naturally going to be biased, and her biases and blind spots are basically the structure around which the book is constructed. The whole book is constructed around how Harriet sees Wimsey, and so the fact that they are the same height, that Wimsey is significantly shorter (for example) than Reggie Pomfret, that Wimsey's self defense classes with Harriet focus on skill and using the other person's strength to compensate for being small yourself, that Wimsey get Harriet to accept his proposal by putting his head down and making himself smaller... the whole book is about Harriet seeing Wimsey as equal to her so him being specifically physically small relative to other men in a way that will not overpower her is very relevant. (In marked contrast, incidentally, to AS Byatt's Possession, about which I've written a long screed about how much I hate its approach to male/female dynamics as relate, among other things, to size.)

All of this is less important to be spelled out in Busman's Honeymoon, at which point they're married already and Harriet feels good about it, all things being equal. So Wimsey can safely go back to being 5'9 again. As, indeed, he pretty much always was.

#lord peter wimsey#dorothy l sayers#harriet vane#whose body#clouds of witness#murder must advertise#gaudy night#busman's honeymoon#seriously though i can't say enough how much i disliked possession#i get that this is not a popular opinion among gaudy night fans but i just cannot#death bredon#charles parker#annie wilson#lord saint george#dian de momerie#i know that murder must advertise is a lot of people's favorites#but i'm sorry i cannot take that drug plotline seriously#and death bredon-as-harlequin is insufferable

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

People need to stop saying that Sayers made Wimsey taller and/or hotter as she fell more in love with him or whatever. He's five foot nine with a weird face and beaked profile literally from beginning to end.

I actually have a post in drafts (EDITED: now posted) that I just started writing out of curiosity that basically goes through what I can find about his height throughout the series and, actually, if anything he's implied to be SHORTER in Gaudy Night (the book most often derided as self-insert fic of Sayers and her dream, apparently tall, man) than in any other book. But there are references to him being 5'9 in both Clouds of Witness and Busman's Honeymoon. This is not complicated.

#lord peter wimsey#dorothy l sayers#gaudy night#clouds of witness#busman's honeymoon#people tend to say that by gaudy night he's taller than previously because of that scene at ascot#but that just says that his HAT is tall#and he's surrounded by women who are likely shorter anyway#plus also he's implied to be the same height as harriet#who is implied to be the same height as annie#who is implied to be “medium height” which for a woman is quite different than for a man as a rule#for a quick extract from that draft#also to be clear i'm not saying that wimsey is implied to be unattractive from start to finish#he clearly is meant to be attractive but it's not necessarily his face that does it

4 notes

·

View notes