Text

Review: Triptych

Gabriel, of Handmade Flying fame, reviewed Triptych:

Triptych is a wonderful look at the strains of not fitting into the gender binary. Adding to that the author's fantastical musings are not overwhelming within the narrative but rather show the characters vantage point and even explain the little things inherent in a universe that is not our own. It is also breath of fresh air to see a non-gender binary character as a lead in a fantasy setting where the struggles of life and gender are just as important as the interesting setting behind it.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Triptych | Part I

Author's Note:

Lesson learned: don't revise your methods section and pilot a research project the same week that you try to finish up a work of writing. Thank you all for being patient.

This story is my original work. Please do not repost. Additionally, You should be aware that it contains descriptions of nudity, implied self-harm, personal struggles with gender, and black coffee, which some of my friends assure me is a very unwelcome concept.

Enjoy!

I was ten when I first started keeping a journal. It was a leather-bound journal, handsome and sewn rather than glued together, and it had a finely detailed tree on the cover that I would find my fingers going to time and time again. It was a gift from my parents and I am not ashamed to say that I wrecked it without a second thought. It rode with me to school every day in my backpack, spent family trips crammed into this corner of a suitcase or that corner of a hotel drawer, was forgotten, was hurriedly riffled through when I was looking for a specific page, was stained by coffee and tea and hot chocolate, and – well, from here I am sure you can imagine the rest. I said that I wasn’t ashamed because I loved that book, and when you love a book you take it with you everywhere you go, like a second soul. The damage was nothing more or less than a natural consequence.

I have my journal with me now, open on my desk. There have been more journals over the years, some completely filled with my scrawling penmanship, some retrieved half-completed and fully forgotten from the hidden places in my room, and some lost altogether. But your first anything has a special weight to it, a special heft in your hand, and I am no more immune to this sentiment than anyone else. It’s a beaten up old thing and I have another book below its cover, supporting it so that it lies flat right now. It is from this journal that I am writing this story – I almost said “account”, but I’m trying not to sound too pretentious here. And both my memory and my journal have their faults. Psychologists and poets both have written reams on the failures of memory. The failures of my journal are a little more personal, being chiefly the fact that my ten-year-old self didn’t give a damn about neat handwriting.

I am most definitely writing for myself – writing unapologetically and frankly for myself. I want to understand my childhood, which is a painful, fragmented mess in my mind. I wanted to give it some order, some structure, some sequence. But I also wanted to write for you – because I had a childhood that was pulled in many different ways by many different forces, and I escaped more or less intact. Haven’t we all? But at the time it would have meant everything to me to have been able to read the story of another person who had thought and felt the way that I was thinking and feeling then, and I did not have such a story. I didn’t even have someone to take me out for coffee and say, “Kid, you’re not crazy.” And I can’t exactly promise that I can be that person for any of you. Coffee is terribly expensive nowadays. I’d go broke within a week. But maybe you, whoever you are, will read my story and take away a sense of camaraderie with this here stranger, even if it’s just a shared bond over how we both take our coffee black.

Coffee is best black, by the way. None of the cream or sugar business. Ye gods.

My name is Phoenix. We’ll get that out of the way first. It’s a name that meant something special to my mother. It matched hers – she’s a Phoebe. It reminded her of her grandfather, who had recently passed away just before I was born. She had spent her childhood reading stories from mythology with him, something that she never failed to bring up when I complained about the weirdness factor. My name also commemorated the fact that I was there to be born at all, because the doctors had been worried for her after the complications with my older brother, Noah. You know, the bird rising from the ashes. Immortal. To cap it all off, I was a redhead. My mother used to say that she took one look at me and realized that it was meant to be.

But it was a name that none of my friends or teachers could ever spell. And it was a name that earned me no end of teasing and catcalling from my classmates, not that they needed much reason to go after me. Occasionally people would call me Nicky, but once the teacher read “Phoenix” off the attendance list, “Phoenix” I would inescapably be. It was part of the reason that I dreaded school.

Dreading school is as good a lead-in as we’re going to get. Let’s go with that.

I lived in a little gray house. There were eight of us in my family, divvied up into tiny bedrooms on the second floor: my mother and father, my sisters Chloe and Charlotte, my brothers Johnson and Noah, and then Hollis and me. Hollis was my junior by two years and a fellow redhead, and we bunked together because there would have been no floor space otherwise. Our room was papered with pages from the comic books we read. In the early mornings the grey light would illuminate the curl of the peeling pages, the angled tip whose shadow lanced back onto the wall.

On such a morning I was half-awake in bed, lying on my side and watching that pale September light. I heard Hollis’s slow, soft breathing below me. Outside in the distance the trees were dark calligraphic shapes spiking up through the mist, gradually fading into its haze. I watched them when I was done watching the curls of paper or the faint cracked pattern on the ceiling. I watched them, and then in the semidarkness I put my hands over my eyes. My face was cold and they were hot, the curve of the palm pressed tight against my face. I was thinking quickly, very quickly: a fever, a fall from my bed. I could roll off and bruise something, maybe even break something – an arm or a leg. Maybe I could stab my arm while I was supposed to be cutting bagels. Would my mother let me stay home for just a bruise or a cut? Maybe I should go for the broken bone. Maybe I –

My mother knocked at the door then, an apologetic knock. I took my hands off from my eyes in time to see her move the old door open just a little, just a crack. It creaked its old well-known hello.

“Phoenix?”

“Mam,” I said. I sat up. I was ten and short enough still that I could sit up in bed without hitting my head. My mother stood fully in the doorway now, dressed already in a long grey skirt, a green collar buttoned below the clasp of her long jacket.

“Would you like to come with your father or with me for morning rites?”

She was whispering so as to not wake Hollis. Her voice was soft to begin with, and I only really caught half of what she said. But I didn’t need to. She came and asked us every morning, if we were awake in time, if we wanted to come with either my father or with her. I usually said yes. Today, though, I shook my head.

“Are you sure?”

“No,” I said, then, “Yes.” Then, “I don’t know.”

She came over to my bed then, all wide open eyes and shallow lines on her round face and a halo of auburn hair braided around her head, and reached for my forehead. I let her touch me. Her hand, too, was cool. I looked at her while she frowned to herself. There was a pause between us, and in that pause my secret unraveled from my mouth and into the quiet room.

“I don’t want to go to school.”

She sighed.

“Mam,” I pleaded.

“I can’t keep you home again, Phoenix. I need to work.”

I felt my stomach knot up and could think of nothing to say to that. She stroked her fingers through my hair. Her eyes had gone to the window, away from me.

“Come have a cup of coffee and we’ll talk about it,” she said.

.

Noah and Chloe were at my mother’s morning rites already when she and I arrived, yawning and winding cloth scarves up over their heads. Both men and woman in my mother’s denomination wore these wide cloths, woven in one piece like a ring of dark wool, the top worn flat over the hair, the rest drawn to the front, crossed over, and flipped to the back so that they lay loosely over the shoulders. They weren’t mandatory, not even at rituals or in prayer, let alone everyday life – although the vows initiates took included vows of modesty, the elders generally left that up to individual discretion – but I had never seen anyone at morning rites, either at home or in a gathering, without a covering of some sort. I took one from my sister and slipped it on. It was warm and comforting along with the slowly smoking incense and the soft yellow glow of the candles my sister was lighting on the altar, and I did not regret that I hadn’t gone outside with my father.

I took my sister’s hand as my mother lay that day’s cut flowers on the altar cloth. She whispered a prayer over them, her voice spidery and soft, before beginning to sing.

I knew the song, a general morning greeting suitable for initiates and non-initiates alike, by heart. I didn’t join in, though. Not that day. I was tired and I let my eyes focus elsewhere: the cuffs of Chloe’s blue jeans peeking out below her long skirt, my brother’s tightly crossed arms, and the twisting shapes rising in the smoke. My eyes moved to the row of white candles and it crossed my mind that if I burned my hand, I could get out of school that day – I could stay home. All I had to do was reach out and –

But the song was over and my mother was speaking and I was missing everything she was saying because I was walking out of the room.

.

I could hear the wild shouts from the stone circle outside, where my father’s altar was kept. The mist was beginning to burn off, and yellow sunlight had crept into the kitchen. The plants at the windowsill seemed to glow with it. I took off the scarf and folded it carefully, standing by myself in the silent kitchen. Breakfast had been laid out already: bread, cheese, and thin cold cuts of meat all in a row. A kettle sat on the stove, beginning to warm.

I went and sat down, holding the scarf in my hands.

I heard the sound of the back door just as the steam on the kettle really picked up and I had begun to think about pouring it over my hand at the sink.

My father was a tall man. He ducked into the kitchen to chase Hollis into the house, the two of them laughing uproariously. My brother Johnson followed behind them both. I watched him catch the door before it could slam into the wall, close it gently, and then latch it securely. He said something – I saw his lips move – but it was drowned out by the din. My father had scooped up Hollis in his arms, all waving arms and kicking legs. The two spun around, knocking some of my mother's drying herbs askance. Johnson came in their wake and caught the swinging bundle with a well-what-can-you-do? smile at me.

"Morning," he said.

"Morning," I echoed. My voice rasped, surprising me.

My brother paused in the act of walking by me and doubled back for a second. "You sound like you could use some tea, kid."

"Yeah?” I said. “Thanks."

Johnson frowned a little at me, but continued on to the stove. I watched him pour out the kettle and set about making our eight cups, pulling mugs from cupboards and fixing loose-leaf tea into pouches. His movements were brisk, automatic. He was slighter of build than my father, more closely resembling the men of my mother's side, especially since he also had my mother's soft, unhurried voice. I had heard him keep it even when he was swearing over a particularly difficult assignment late into the evening. He had my father's blond hair, however, and he wore it similarly long and straight, although today it was carefully tied back the way most men’s hair was worn. I heard heavy steps on the stairs and realized that I was alone with him for a moment -- my father must have taken Hollis up to our room.

"Johnson?"

"Yeah?"

"I want to stay home today."

My brother said nothing. I looked earnestly up into his face as he came over and bent down to give me my mug, but he didn't meet my eyes.

"So soon, Nicks?"

"Yeah."

“You don’t even want to give your fifth year a try?”

“No.”

Johnson stirred another mug and did not reply. I watched his fair hair outlined by the sunlight at the window and suddenly thought that if I had Johnson to watch me, neither of my parents would have to worry about me being alone.

I fielded the question to him, but he simply shook his head as he began bringing the rest of the mugs over. "I'm a twelfth-year student, Nicks, what would that look like?"

My face must have fallen, because my brother took a seat opposite me at the table and did meet my eyes then. "But I'll talk to Mam. All right?"

I sighed.

"Nicks."

"All right."

He lapsed back into thought, gazing into his own mug. I drank a little and realized only then how dry my throat was.

"I just don't want to go," I whispered.

"It'll be better than last year, Nicks," Johnson said soothingly, still not looking at me.

My father returned with both Hollis swinging in his arms and my mother behind them, and I watched them all file into the kitchen. My father was loud and leonine with his deep voice and wild blond hair, and his presence filled the room. He smelled like wood smoke and salt water, a smell that was ingrained in his calloused hands and leather belt and ember-scarred skin.

“Good morning, you,” he said cheerfully, taking a seat near me and reaching over to ruffle my hair. “How’s another of my redheads this morning?”

I opened my mouth to tell him a tangled black mess of unsaid things, and found myself saying “Fine,” instead.

He paused after a mouthful of tea and frowned a little at me. “Just fine?”

I looked away. “Yes.”

He might have asked me how I really was. If I was sure that I was fine, or told me that I could always come to him if I needed to. He had said all of these in the past, and even I wasn’t quite sure why I couldn’t tell him. I wanted to confess but I was frightened to confess, and these two warring forces leveled out to silence. That morning, with my head aching slowly and sickeningly in the early sunlight, I might have said the truth. But he didn’t ask and I didn’t say.

Breakfast was a busy affair after that, and I did not bring up the subject of staying home again. My father talked with my sisters about their course choices and gave them tips for note-taking. Johnson patiently got Hollis's coat on while my mother looked for a brush for Noah's hair. And I said there feeling numb, like I was moving both too slowly and too quickly, letting the conversation creep slowly up and over my head.

Chairs were pushed back, plates clattered. I was zipping my coat up and pulling on my backpack while my heartbeat picked back up and that smothered, surreal feeling began to edge back into the day. I looked for my mother in the doorway, but she was holding Hollis's hand and facing my sister Chloe. I opened my mouth to interrupt, but then closed it and looked away. My throat was tight and pained, like something sharp was caught there.

I did look back at the kitchen table, however, thinking that I might just run upstairs and crawl below the clothes in the closet and vanish – vanish forever.

The kitchen, however, was silent and indifferent and bright. The folded-up headscarf still sat on my chair where I had left it, unnoticed and out-of-place.

I left.

.

It was a ten-minute walk to the train station, and I don't really remember retrieving my student ticket from my passbook or boarding the train. I do remember watching my siblings once I was on the train. I watched my sisters' long skirts, Charlotte's hair that fell just below the knee and just at the dress code guidelines, Chloe's hair that went a modest distance to her ankles, over her jeans. I watched Chloe's laced boots and Charlotte's dark pumps. I watched the elegant chignon Chloe had twisted her hair into when she leaned over to pull a textbook from her bag, and the arc of Charlotte's loose hair as she tossed it thoughtlessly over her shoulder. I watched my brothers as well, their muted button-down shirts tucked into their pants, their dark jackets, their heavy shoes. I had intentionally chosen my long coat today and worn it despite the balmy September mid-morning to cover all of my clothes, although I could not cover my shoes. I sat, jostled by the rocking train and swaying with its movement, and thought about pulling my feet up below myself and kneeling on them so that they were hidden. It was a good plan -- for the train. I couldn't sit like that at school. I would have to take off my coat at school.

As if to underscore this, Chloe whispered to me, "Phoenix, take off your hood. You're inside."

I drew it off slowly, and spent the rest of the way looking out the windows and meeting no one else's eyes.

Schools in our community started later than schools elsewhere, to accommodate morning ceremonies. It was sunny in full force while we walked from the train stop to the school. What greeted us was the usual morning mess: thrown papers, catcalls, dark glares from students trying to cram in some early study, and a generally rowdy crowd of students milling about in the central courtyard. The noise drowned out my brother's goodbyes. He simply waved to Hollis and I as he left. Chloe had already started off for her group, waving and calling out to them.

Charlotte, however, stayed, and although I remember very little actual detail from that morning, I still remember Charlotte in her long knitted duster, still amidst the bustling crowd, her fingers hooked into her deep pockets and her eyes turned, intense and thoughtful, at me.

“Have a good day,” I said.

I don’t know if she heard me. I certainly didn’t hear what she said back: the crowd drowned her out. But she drew one of the straps of her large bag from her shoulders, reached inside, and handed me a white folded-up canvas bag. I took it automatically, but before I could say anything else she was walking away, clasping her bag shut as she went.

.

There were twelve grades of students and three two-story, cramped buildings that they crammed us all into, arranged around a central courtyard that was little more than the remnants of the field the school had been built on. Students weren't required to be from our community, but most of them were. I saw the brown corded bracelets all initiates wore, regardless of sect, on many of the older students' wrists as I slipped through the crowd to my class. I saw the special clothing that distinguished each sect as well: some young men and women with scarves like my mother's set carefully on their hair, some with blue tattoos like my father's on the backs of their palms, and still a rare handful of others in the long black veils of the third sect, which no one in my family belonged to and which I knew little about at the time. I paused to gaze at one such older student, who was drinking an espresso in a little china cup she had balanced on a math textbook.

"She's a Sister," Hollis said. I could barely hear over the crowd, but Hollis was happy to stand on tip-toe and shout directly into my ear. "Mam told me about them – Phoenix?"

“Yeah?”

“What’s that?”

I looked at the bundle of canvas my sister had given me, a bag folded over and to the side. With Hollis watching curiously, I unfolded it, reached inside and –

I pulled out the headscarf. The one I had taken from my mother’s altar room this morning, folded neatly just as I had folded it in my lap at breakfast. I lifted it out of the bag too quickly and it tumbled open, the cloth twisting slowly in the breeze.

Hollis, wide-eyed, recognized it too and backed up a step. “You’re not supposed to have that.”

I didn’t reply. It had just struck me, how I could get out of at least one part of this. I looked at the scarf in my hand. Its wide folds would hide the distinctive cut of my hair. It wasn't going to do much about my other clothes, although maybe, just maybe, I could keep my coat on.

In the distance someone called out with, “tweet! Tweet tweet-tweet tweet tweet!” I looked up, the scarf still in my hands, but whoever it was had slipped into the crowd. That moment, though, had shaken me from my reverie. Before I could argue with myself further I put the scarf on, crossed it, tucked it over my head. It was loose but not too loose, and although I hadn't pinned it or used a comb to fit it into my hair I was pretty sure that it would stay in place as long as I kept my shoulders back and head up.

I took a deep breath. I still felt tense, almost sick, but the sunlight seemed a lot less unfriendly now.

I dodged Hollis's confused questions and made my way to where my classroom was lining up.

.

To my great surprise and eternal gratitude, my teacher let me keep my coat on. To be more precise, my teacher didn’t make me take it off: I slipped out of line while we were hanging up our belongings in the tiny coatroom next to our classroom and made for my seat with the long, dark coat still snugly buttoned up to my chin and my hair safely hidden. There was that little round colored dot on my nametag that told on me, yes, but if I tucked it halfway into my coat you could still see most of my name but not the dot.

My teacher, an aged woman with curled grey hair, still used pronouns for us at group time and while she was seating us for our mathematics lesson, but she didn’t call any extra attention to me. In my scarf and my coat I felt on edge, hyperaware of my disguise and how one little syllable could betray it, and I felt also very conscious of the many curious eyes that came my way from my classmates. I kept my eyes forward, but my heart was beating quickly all throughout that first lesson. Every time the teacher turned around from her board and gazed out over a sea of fifth-years I held my breath a little, thinking: please don’t call on me. Please don’t call on me. Please don’t call on me. Please –

“Phoenix?”

“No!” I blurted out. She looked immediately taken aback, and I hastened to cover for myself: “Um. Um. I’m sorry. I – Yes?”

She gazed at me for a moment as if she was going to say something, but then said, “Can you tell me what the sum here is?”

I told her.

“That’s right,” she said. “That’s … very good.”

Her eyes lingered on me, but she returned to the lesson without comment.

I remembered absolutely nothing of that lesson or any of the exercises we did by the time we had our break, but I was slowly making it through the day, and I had started to calm down. That calm quickly sunk into a deep-seated tiredness, and I walked outside for recess like a zombie from one of Chloe’s storybooks, my arms dangling limply at my sides and my back aching from standing up too straight.

I veered almost immediately away from the crowd in the courtyard. Four-square ball and hopscotch weren’t my thing, and some of my old classmates might take the opportunity to tweet at me again, which I hated. I cut diagonally between two of the buildings and walked out onto the wild red grass on the farther side of the field, thinking that if I could really be a bird of fire then this miserable place would have been burned down ages ago.

But it was peaceful out there, with the long thin white-bark trees rising up into clouds of red leaves. My hair was damp below my scarf and the breeze was cool against my face, and I let my shoulders droop. No one was here, no one at all. I could hear shouting in the distance, but that was the distance. That wasn’t here, in the shelter of the still red leaves.

I welcomed that quiet and the stillness. I sank down with my back to one of the trees and felt my body relax into it. I could have slept there, I was so tired. It was an ache that weighed inside my head and settled into my shoulders. I closed my eyes and leaned all the way back, letting my back bow and my knees curl up to my chest.

My siblings were in that thick crowd in the distance, a part of the noise and the commotion, but I couldn’t will myself to stand up and join them. I didn’t really want to see them anyway. They would ask about today, and I already wanted to forget today.

When the bells rang for the end of our recess they woke me from a reverie that had been creeping close to sleep, and I walked back slowly and tiredly to find that everyone else had already lined –

Wait.

Everyone else had already lined up.

The crowd had divided by year and by class in long rows of students, but the afternoon teacher in my section had split my classmates into one line of boys and one line of girls. I hadn’t been paying attention from further away, but now I saw the rows of skirts and pants, the pale colors of the girls and the somber colors of the boys.

I slowed as I came to my class until I was standing still outside the two lines. Most of the students were chatting away amongst each other, but a few eyes had turned, with a sort of lazy half-curiosity, to me.

“Are you in my class?” The afternoon teacher asked, breaking away from a conversation with another student to call me over.

I took a step or two towards him. “Yes.”

“Then get in line, please.”

The teacher’s voice was not unkind, but there was a brisk authority to it that frightened me. I didn’t want to get in line – getting in line meant choosing, and I couldn’t choose. That was it. I couldn’t choose. I didn’t want to be punished but I just couldn’t choose.

I didn’t move.

The teacher made a well-hurry-up gesture with his hand, then paused to scrutinize me carefully. There was a moment of silence between us, and then I realized that he couldn’t tell, below my headscarf or my coat, what line I belonged to. There were no clues. With the dot on my nametag safely hidden I was a neutral party, safely hidden.

But I would not stay hidden for long. I was suddenly hot below my scarf and coat, hot and shaking.

The teacher rallied. “Well, if you are my student you will see that I have young ladies lined up here, and young gentlemen lined up here. Phoenix – it’s Phoenix, right? – What an interesting name. Phoenix, are you a boy or a girl?”

Now everyone was looking at me. Our silence had spread out around us, turning heads and ending conversations. I was suddenly acutely conscious of the weight of everyone’s attention on me, marking everything from my freckles to my deliberately bland shoes. A few of my classmates were grinning, and so were plenty of the older students. Did I seem defiant to them? A long stranger standing outside of the system? Standing up to the man? Or did I just seem amusing, this little freckled-face kid upset about having to stand in line? I wanted to tell them that if there had been a place where I fit right in, a line that I could join, I would have been there in a heartbeat.

As it was I stood paralyzed and looked down at the ground, where the red grass blurred in my sight.

My teacher repeated the question, but I wasn’t listening. Someone was taking my arm, someone was turning me around, someone was putting a hand on my back and leading me away from the long silent lines of students and the sun on the blurred grass, someone was rescuing me.

.

I walked into the administration center with my head down and my eyes closed, holding blindly to whoever had me securely by the arm and shoulder. I could hear the authoritative click of heels on the bare floor and the soft hum of voices in the offices. It was soothing, somehow. I thought at first that it might have been my morning teacher, but when we pulled to a stop and I finally looked up, I realized, to my surprise, that it was my sister.

Charlotte was between Noah and Chloe, young enough to have not been initiated into the religion but old enough to – apparently – sign me out of school. I knew her the least of all my brothers and sisters. She kept to herself and spent much of her time in her room, and she and I rarely spoke. I watched her sign one dotted line after another, and took the opportunity to wipe my eyes and nose on my long sleeve.

“Thanks,” I said.

She put the pen down and shuffled the papers. Her voice was casual, as if we had just come home together like any other day. “Do you want a cup of coffee, Phoenix?”

“Yeah.” I said. My voice rasped and lost its power halfway through, and I coughed a bit before trying again. “Yeah.”

“Me too,” she said, holding the papers up above the thin metal tray. “This place just gets boring, you know?”

I nodded mutely. She dropped the papers into the tray, where they fell perfectly into place, and mouthed “Whoosh” with a smile. A few of the office staff looked up at us, but Charlotte ignored them completely. She tapped my shoulder and walked off, unhurried, down the very center of the hallway, and I matched her step.

.

We walked out of school, out of the courtyard where the other students were now slowly filing into the buildings, and out onto the sidewalk. Heads turned to watch us. Charlotte ignored them, and I wished that I could, too.

It was a calmer, lazier world out here. A handful of people on bicycles rode leisurely past us, their great wheels catching my eye. Shops had their windows and doors open, the little panes of glass glinting in the light. An old clock tower rose up from the end of the street, its white face inscrutably surveying the scene before it. Trees lined the road, their white bark spotted with dark brown; like the ones at the school they were capped with vibrant red leaves, all of which whispered together in a great moving susurrus when the wind blew through.

I took a deep breath, let it out in a long, trembling sigh, and took a second deep breath. I was free, wonderfully free – at least for the moment. I felt lighter, and with each step away from school I relaxed more. Charlotte was gazing around without interest, her arms folded loosely. We walked without conversation. If this bothered here, she did not say.

.

We sat down at a table in a great old coffeehouse. My sister took a chair with its back to the wall, crossing one leg over the other and leaning one arm on the table. She was a still figure amidst the bustle of the place, with people walking in and out and gathering in groups to talk. We had white cups of coffee and a little silver pot of cream, and I picked mine up carefully to take a sip. It was hot, smooth, and faintly nutty, and it gave me some measure of my composure back.

For a while I forgot the earlier schoolday in favor of staring at the long, polished wooden bar and the great lofty ceiling up above. Small square oil paintings done in blues and greens hung on the walls. Light streamed through the thin windows, augmented by little glass lamps on the tables.

“Are these electric?” I asked Charlotte, leaning my elbows on the table in order to get a closer look.

“Yes,” she said. Her voice was low and even, and I had to scoot forward in my seat to hear her. “In the evenings they add candlelight as well.”

“This place is really pretty,” I said sincerely, sitting back in my seat.

Charlotte smiled at me and reached for her cup. “I think so, too.”

“Are you –” I began, but Charlotte wasn’t paying attention. She was watching the crowd expectantly, both hands cupped around her coffee.

“Hm?”

“Are you going to ask me about today?”

She looked at me with a languid sort of curiosity. “Do you want to tell me about today?”

“No.” I said. Then, “Yes.”

“Hm?”

“I couldn’t pick.”

I drank some more coffee, not looking at my sister. If she was looking at me, I couldn’t tell. She shifted slightly in her seat, enough for me to hear the slipping sound of cloth on cloth and see the dark pool of her skirt fall over one side of the chair.

“I can’t pick,” I said. “I’m not a girl or a boy. I … I’m like … Charlotte, you know how fish, like the fish at the aquarium, have gills, they breathe water?”

She poured some more cream into her cup. “They pick up oxygen from water with their gills, that’s true.”

“But birds don’t have gills, they breathe air?” I realized that I was fidgeting with the tablecloth, and put my hands back into my lap. “Well, I – it’s like I have both gills and lungs. But they’re not okay by themselves. I need to breathe water and air. I mix. I’m not a fish because I breathe air too, but I still need water – and I’m not a bird because I breathe water too, but I still need air.”

I rushed the last part of this analogy. I had outlined it for myself weeks before, after a trip to both the aquarium and the comic book store, and I was proud of it, but saying it to myself alone in my head and saying it aloud to my sister, in this busy shop full of people, were two very different things.

My sister did not respond. She was watching the paintings, absently turning her cup in her hand.

“Charlotte?”

“Hm?” She said. Then, simply, “I knew this, Phoenix, you know. Or at least, I guessed.”

I was silent.

“It was obvious,” she said mildly, still gazing thoughtfully at the paintings, “But not everyone sees things, Phoenix. Some people don’t look. Some people can’t.”

“If they couldn’t look at me, I’d be okay,” I said, speaking before I had thought it over.

“So much of gender is visible, or relies on visibility,” Charlotte said smoothly, now looking me straight in the eyes. “What I meant, though, Phoenix, was that some people are fucking idiots.”

I was shocked. I had never quite heard anything so blunt. In my classroom we had to apologize for “shut up” and “dummy,” and here was my sister saying this as casually as she might comment on the weather. Despite myself, I giggled. She smiled again, and I started laughing harder. It felt good to laugh – like a great tension had eased inside me, like the bright electric light was now sparkling through my blood. I was laughing and crying and putting my head down on the table with my cheek to the cool wood, and I was tired again, very tired, but feeling somehow more whole than I had felt all day.

She began to say something else, but she cut herself off to put her cup down and raise a hand, greeting someone in the crowd.

I rubbed my eyes and turned around in time to be greeted by the sight of a young man waving in our direction, then pulling away from the crowd and walking towards us.

Charlotte had always struck me as something of a rebel, with her knee-length skirt and darkened lashes. I did not know what to make of this man, though, and he was a man, older than my teenage sister by some years. He had a thin, foxlike face, and he also wore a long red scarf as bright as the leaves, which I had rarely seen before on anyone and which fascinated me. I looked instinctively at his wrist as he approached us and put his arms down on our table, and did not see the braided cord bracelet of an initiate of any sect. He was not tanned or tattooed, but he did have a few rings on his fingers. They glinted in the lamplight.

He looked at Charlotte, looked at me, and looked back at Charlotte. “Who’s the kid?”

“Mine,” Charlotte said quietly. “You’re late, you know.”

“Oh, I ran into some friends,” the man said, laughing a little. He leaned over and kissed my sister’s cheek.

“This is Phoenix, my – my sibling,” Charlotte said, not returning the kiss.

“Oh yeah?” Unperturbed the man turned around, smiled at me, held out his hand, and then paused. “Wait, do you two shake hands?”

“We do,” Charlotte explained. “It’s the third sect that doesn’t touch.”

“Odd, right?” The man said. I took his hand, but he was looking curiously at my sister and didn’t seem to notice.

“I don’t think so,” Charlotte returned mildly. She drained her up and set it down with a decisive clink. “Shake hands with Phoenix and make friends. We’re taking h— We’re taking Phoenix with us.”

“We’re taking him? Or –” his eyes flicked from my head to my toes for a moment, “--or is it her?”

Charlotte frowned a little at him, and he dropped the subject and my hand. He also dug a hand into his pocket and dropped some heavy coins onto the table, where a few rolled before falling to a stop. I stopped staring at his outrageous scarf and started staring at the coins, trying to see whose head was featured on them, until I realized that my sister had set up cup down and was standing up.

“Shall we go?” The man asked briskly, giving me another curious look. Charlotte hooked her hand into the creek of his elbow and he smiled at her, a smile that seemed the sharp angles of his face seem gentler.

We left together, with me walking behind the two of them.

.

His home was an apartment above a row of stores, more spacious than I had judged that it would be from the outside and completely unpainted. The walls and floors were bare, save for a few tapestries hanging here and there. The entire place smelled strongly of paint, so strongly that it seemed to hit me like an invisible barrier the moment I stepped into the room. There was something solid about the permanence of the smell, the way it clung to everything in those rooms. My sister pointedly opened up a window, which prompted the young man to begin apologizing.

“I don’t even notice it, not after all these years,” he said.

“My artist,” she replied, in a tone I had not really heard before and could not quite place.

He left soon after that, and my sister gestured to me and then the couch. I settled down just in time to watched the young man return with a canvas. I still did not know his name: neither he nor my sister had said it aloud, although by now I was actively listening for it.

“Should I help you set up?” Charlotte was saying.

“Nah, it’s okay. Go get ready, and remember – light!” the artist said brightly, waving her off.

She turned and walked to the middle of the room, where the stool had been placed. I watched her run her hand over its top and nod to herself, and I was just about to ask her what was going on and whether she could get me a cup of water when, with a sudden careless impatience, she drew her shirt off over her head and tossed it to the couch.

I immediately forgot about the cup of water as I watched her she unhook two buttons and slip out of her skirt. It crumpled into a ring around her on the floor, followed by her pantyhose. Before I was really aware of what was happening she was drawing off her panties and unclipping undergarments stranger than I had ever imagined, stepping out from them and kicking them, with one swift stroke, to the side. Naked, completely naked, she settled down on the stool.

I sat both appalled and mesmerized. It was the first time I had ever seen the female form revealed this way, by anyone, for anyone. I had seen it painted and sculpted and in glimpses in my home but never so exposed, not like this, not in person. It was both anticlimactic and exciting – the peeled paint on the walls, the dried coffee stains on the couch, the roughness of the floor below my feet. I wanted to look anywhere else, but my eyes felt glued to her. She sat straight-backed, facing away from a window. The sunlight crowned her. In its spilled light her honey-blond hair was warmed by a coppery touch, tumbling over her shoulders and down her back. She was smooth, curving gently from her two pointed breasts to her waist. Her legs were crossed, and her hips rounded down heart-shaped to that point of crossing. And at the center of that heart, nearly hidden from view by her crossed legs, was a pale, feathery curl of –

But here I looked away.

I was ten, remember. I was ten and I was blushing furiously, reaching for a nearby pillow and worried that Someone was going to come into the room, that Someone was going to catch me with the painter and my naked sister and know that I had looked at her body and, and – I hid my face. Something sick and guilty curled inside me.

The painter hummed while he began to work. If either he or Charlotte noticed me, sitting bent over on the couch with a pillow crammed into my face, they didn’t say anything about it. He hummed and then she hummed, too, and then he shushed her. “Stay still,” he said gently. “How am I supposed to capture you if you don’t stay still?”

“Women are not meant to be captured,” my sister whispered back.

“Your beauty, your pretty face,” the man said, waving a paintbrush at her. “You know what I meant.”

“Did I?”

“Shh, hold your arms still, please.”

I peeked up in time to see her raise her eyebrows at him. He wrinkled up his nose and looked somewhat plaintive and apologetic, and she returned to her original position. The artist’s eyes went to me for a split second, and then I disappeared back into my pillow.

He picked up his humming soon after that, and this time Charlotte did not interrupt him. I kept my face hidden and thought about how I had left my backpack at school, sitting in the coatroom. I made a note to myself to tell Charlotte about this as soon as she put her clothes back on. I didn’t want to write it into my journal. My tiredness was returning to me there on the couch, and suddenly reaching for my journal seemed like an insurmountable task …

I must have slept. I don’t remember anything else about that time at the apartment until my sister was shaking me awake and calling out my name, and I realized that I had fallen sideways on the couch, my cheek to the pillow. The artist was in the other room, smoking a cigarette. My scarf had slid to the side, and I pulled it back into place after checking that he wasn��t looking.

He came back to hold the door open for us to leave, bidding goodbye to my sister and smiling at me. I smiled back, thinking that cigarette smoke had an oddly sweet scent. Charlotte was walking far ahead of me, though, and I turned around to hurry up.

.

We walked back without conversation. She was humming something unrecognizable but upbeat, and I scuffed my shoes aimlessly at the cracks in the pavement as I listened. I felt thoroughly worn out, and also broken off, in some indefinable but profound way, from everything that had come before that day. It was a drifting, disturbing feeling, made all the worse by the fact that everything around me seemed so normal and so indifferent. The street full of low-ceilinged shops didn’t care that I had left school and seen my sister undress and finally given voice to my thoughts about my gender. The waving red leaves didn’t care. The spiderweb of cracks spread through the pavement didn’t care. We all just went on, and I didn’t know what to make of it.

Charlotte wasn’t precisely forthcoming with life-defining advice, and she kept humming and I kept looking at my shoes until we got to the gate before our house. She shrugged me off there without fanfare or preamble, just a vague wave of her hand. “Go around, through the woods and into the garden,” she said calmly. “Don’t come in the house just yet.”

“All right,” I said, but she was already leaving me. I said her name, but she did not turn back.

And so I went into the woods by myself.

.

I had played here before and still did sometimes, when I wanted to be really alone and out of the house or when I could get someone to come out and roughhouse with me. The path that led from the gate to the back door was strewn here and there with the paper streamers Hollis and I had taken to the trees a few days earlier, matted now alongside last year’s fallen leaves. As I walked I noticed the side-path I could take to reach a little brook where I liked to go and sit and listen to the water babble on. One of Chloe’s lost arrows stuck out from a tree nearby: I gave it a tug, thinking to bring it back with me, but it was splintered deep in the wood and I soon gave up. Fragile little plants joined with tangled dead branches to complete the undergrowth, all of it dappled with light and gray shadow.

A few beetles were out today. I spent some time crouched on the edge of the path with my nose up to a plant, gazing at a huge, horned brown one and thinking of all of the books on insects in my collection that I should re-read soon. Further on, I saw a hollow of an old log sheltering some mushrooms. There was a faint green stink of decomposition interwoven with the dark smell of the soil. Every so often, a bird twittered. I could even see, off to the side a ways, a row of little stones.

Those hadn’t been there before. I slowed for a moment, then headed towards them.

They were arranged neatly in a line parallel to the dirt path, in the center of a wider area where the bare ground had been uncovered. The rocks themselves were nothing special – just rocks from the garden or from elsewhere in the woods. I veered off of the path altogether, circled around them, and knelt down to get a better look. Someone had carefully washed them off and then dug little dips in the ground for them to fit into place.

I looked around. No one else was there, but the hairs on the back of my neck were standing up. I suddenly had the sensation of being vulnerable, of being … of being watched.

I turned back around so that I had both the rocks and the path in view. I was no longer weary, but I was also no longer curious. Whatever my parents had in store for me at home suddenly seemed not so bad – a fair price, even, for getting to a place with walls and doors you could lock. I took a few steps forward, crossed over the rocks, and walked back to the path.

I walked quickly, wanting to be home soon.

But I did not arrive home.

As I went, the trees darkened. Instead of their usual white bark and thin girths they began to widen and to warm to first tan and then brown – slowly, bit by bit. The leaves cooled from red to brown to a strange and vibrant green, and the grass that poked up through the undergrowth mirrored this change. The birdcalls had disappeared. The afternoon sunlight had lost its warmth, turning gray and distant.

At first I had kept walking because I had assumed that I was imagining something because I had already felt uneasy about the woods. In fact, I lowered my eyes and watched my shoes again, although my ears were straining to hear the sounds around me. It was a shock to lift them up and to find myself surrounded in an unnatural and unexpected world of green. The trees now gave way to a sweeping sky of near-white, without a sun or even a bright spot in the clouds to indicate a hidden sun. I wasn’t even sure that there were clouds at all. There was just a smooth, unvaried sky of near-white, and below it – silence.

I stood gazing up at that alien sky, a cold and hollow feeling stealing into the center of my chest.

And then I turned back, and ran.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finally got my manuscript and got a chance to sit down.

Piloting research projects with four-year-olds is crazy, crazy work, especially with methodology reviews and ethics proposals. I hadn't anticipated being completely exhausted from both the fallout of Halloween and a day of experimenting with children.

I know I said that I'd have this story up a day or so ago, but it'll probably be another few hours at this point. I'm still celebrating being able to have more than two minutes to myself. Also I genuinely doubt that any of you care so I'll go ahead and take my time.

I'll post it when it's coherent. Thanks for your patience.

0 notes

Text

Sneak Peek

I was ten when I first started keeping a journal. It was a leather-bound journal, handsome and sewn rather than glued together, and it has a finely detailed tree on the cover that I would find my fingers going to time and time again. It was a gift from my parents and I am not ashamed to say that I wrecked it without a second thought. It rode with me to school every day in my backpack, spent family trips crammed into this corner of a suitcase or that corner of a hotel drawer, was forgotten, was hurriedly riffled through when I was looking for a specific page, was stained by coffee and tea and hot chocolate, and – well, from here I am sure you can imagine the rest. I said that I wasn’t ashamed because I loved that book, and when you love a book you take it with you everywhere you go, like a second soul. The damage was nothing more or less than the natural consequence of a ten-year-old’s love.

Part I of Triptych, a free shot story I am offering to you, will be available here at nepenthe-architect.tumblr.com on November 1st.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

writing resources!!

i’ve collected a lot of different sites over the past couple years that i use for my own writing so i thought i would share them all in a masterpost

these sites are super helpful

How to Write a Novel in 30 Days - also comes with a super helpful downloadable pdf of worksheets

How to Write a Novel Using the Snowflake Method

9 Questions for 25 Chapters

Literary Magazine Directory

Submittable (used for online submissions)

Scribophile

The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations

Compiled list of writing experiments

The Ultimate Guide to Writing Better Than You Normally Do

Poem starters

Index of “word stuff”

How the Rules fo Screenwriting Can Improve Your Fiction

15 Unconventional Story Methods

Freewriting tips

Submission call roundup

Nameberry name lists

Freemind

The Language Constrution Kit

StumbleUpon writing

books on writing/being a writer

On Becoming a Novelist by John Gardener

Writing the Breakout Novel by Donald Maass

Rose Metal Press Field Guides: …to Writing Flash Nonfiction, …to Writing Flash Fiction, …to Writing Prose Poetry

bonus round: sites i love for physical writing tools and recs of what i use

ShopWritersBloc - incredible variety of physical writing tools at the most reasonable prices i’ve seen after searching several sites including amazon. they carry paper products but their collection of pens is the best i’ve found. i use platinum preppy fountain pens (a disposable fountain pen; you can replace the ink cartridge in the nib when it runs out or you can buy a converter so you can use it with bottled ink)

MyMaido - amazing site for midori journals (my favorite) at very decent prices compared to other sites. i use midori md notebooks with lined pages (large size) because the paper quality is amazing and ink dries fairly quickly, even when i’m writing with a fountain pen, and they open flat because they have a stitched binding.

TheJournalShop - helpful if you live in the uk!!

i’ll be keeping this updated too

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

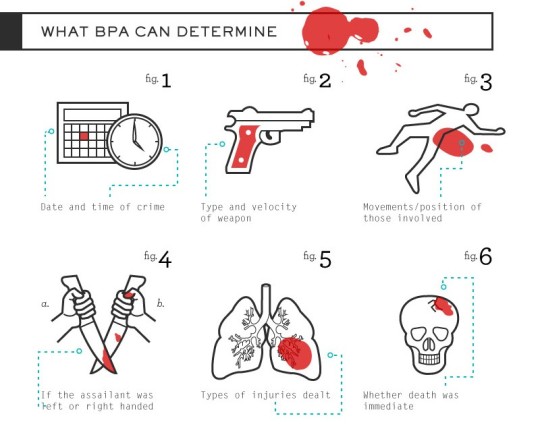

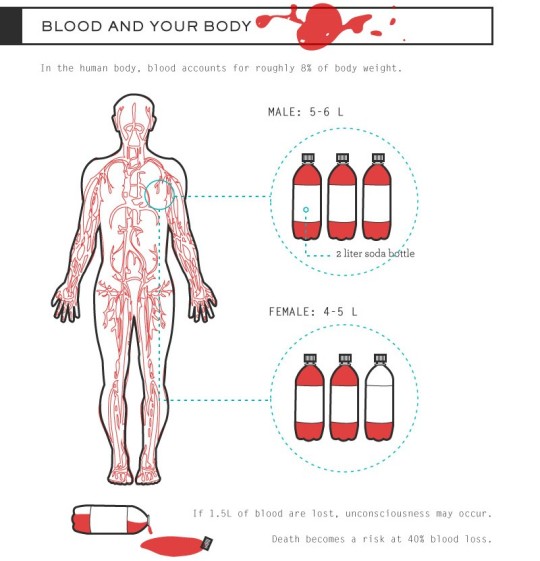

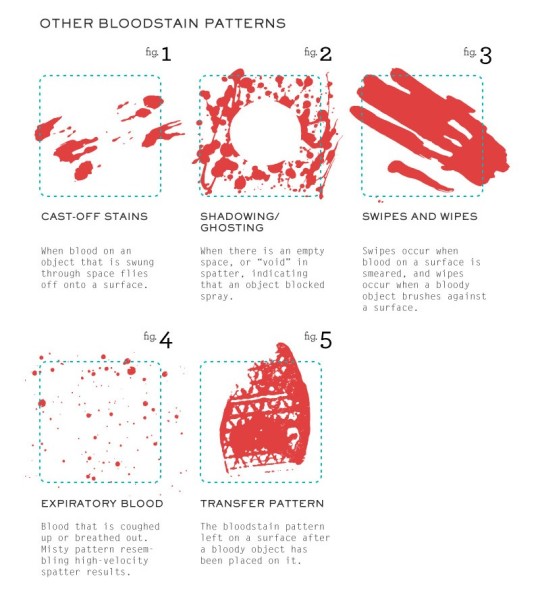

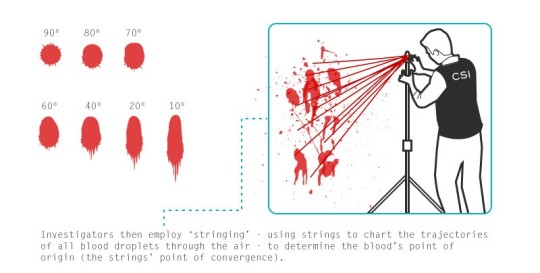

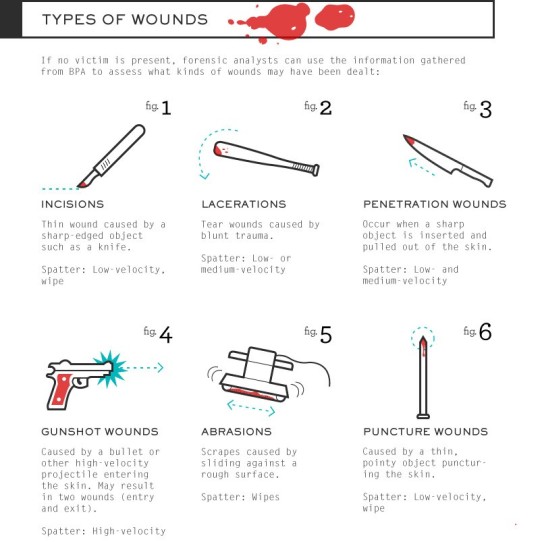

Bloodstain Pattern Analysis (BPA) - Resource for Crime Writers

SOURCE

194K notes

·

View notes

Text

#Triptych

It’s difficult to be caught between two religions. It’s even more difficult to feel caught between two genders. At that point, being caught between two worlds, accessible through a door you found in the woods behind your house, doesn’t seem like that big a deal.

Do you like paintings of beautiful creatures, mysterious sounds in the night, doorways to other worlds, discussions of gender and religion, characters with improbable names, and pomegranates?

Part #1 of Triptych comes out on November 1st. Catch it here.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Waterfall fountain in Osaka. [video]

104K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Another Halloween themed post.

Part I: Superstitions

GHOSTS AND SPIRITS

Iron and Ghosts

The Early Ghost

Guide to Ghosts

Ghosts

Gravestone Symbolism

10 Little Known Mysterious Ghost Types

Ghost Types

The Different Types of Ghosts

Haunted Places

Cemetery Folklore

Writing a Ghost Story

Tips for Writing Ghost Stories

Ghost Cliches

Horror Cliches

ZOMBIES

The Science of Zombies

Zombie Biology

Zombie Sociology

Zombie Myths

Stage II and Stage III Zombies (pictures)

Vampires vs Zombies

Undead Creatures

Zombies

Guide on Zombies

SHAPE SHIFTERS AND HOMINIDS

Werewolves and other were-beasts

The Shape Shifting Process

Shape Shifters

Hominids of the World

Werewolf Myths

Science of Werewolves

Werewolf Behavior

Werewolves vs Vampires vs Zombies

Werewolf Anatomy

Wolf Body Language

Lycanthropy

Werewolf Myths and Truths

History of the Werewolf Legend

SEA CREATURES

The Mermaid

Sea Creatures

Books About Mermaids and Sea Folklore

Sea Creatures: Books

YA Mermaid Novels

Best Mermaid Books

Awesome Mermaid Books

Mermaid Anatomy

A Dissection of Mermaid Anatomy

VAMPIRES

African Vampires

Writing the A-Typical Vampire

So You Want to Write a Vampire Novel

Avoiding Vampire Cliches

Vampire Cliches

Vampire Burial

Vampire Mythology

Vampire Biology

Vampire Virology

Vampire Sociology

Vampires in Folklore and Literature

AVIAN CREATURES

Underused Bird Mythologies

FAIRIES AND FAE

Types of Faeries A-Z

A Guide to Fairies

Other Names for Fairies

Books About Faery

Best YA Fairy Books

Best YA Fantasy Series About the Fae

ANGELS AND DEMONS

A Glory of Angels

Angels and Demons Resource Post

Do You Give Angels Flaws or Not?

Unusual Angels

More:

Creating Creepy Creatures

Mythology Meme

Master Post of World Mythology, Creatures, and Folklore

Figures of Norse Mythology

Those Who Haunt the Earth

Writing Horror, Paranormal, and Supernatural

Genre: YA Supernatural

List of Mythical Creatures

Mythological Creature Picture Spam

How to Make Your Supernatural Characters Unique

Supernatural Theme Story

Myths and Urban Legends Masterpost

Original Gods, Goddesses, and Myths

World Building Basics: Myths and Legends

Mythical Creatures and Beings

Symbols by Word

Mythology Meme

Writing Paranormal Characters into the Real World

61K notes

·

View notes

Photo

How to improve writing skills by reading different genres (Source)

18K notes

·

View notes

Text

I write compulsively, and when I write the story consumes me. This is how it's always been -- this process of wrapping yourself in your work like weaving a cocoon, a place where the outside world filters through to you in bits and pieces.

Sometimes it fades. If I don't read or write, it fades. I am single-minded. If I turn my focus completely to my schoolwork, my writing curls up inside me like a cat, asleep for now.

But sometimes I literally cannot concentrate on my schoolwork. Forcing myself to not write when I need to write is like trying to stifle a fire with my bare hands.

It makes me wonder sometimes what I'm doing with myself in college.

0 notes

Text

What kind of music do you like to listen to while writing?

Do you make playlists for characters or genres?

I'm curious now.

1 note

·

View note

Link

For fiction writers, dialogue is one of those tricky things you really have to master and it certainly takes time. My dialogue certainly suc

9 notes

·

View notes

Link

Pixar storyboard artist Emma Coats provides a glimpse into her own creative process and lists 22 rules for sturdy yet surprising narrative construction.

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

If you are in difficulties with a book, try the element of surprise: attack it at an hour when it isn’t expecting it.

H.G. Wells (via thewritersspotblog)

23 notes

·

View notes